Abstract

The concept of dynamic symmetry in art and extensive measurements on Greek vases suggest that a vase and its parts can be inscribed into similar rectangles, with all rectangles having the same ratio of lengths of their side. Such an observation is often used in describing self-similarity and fractal geometry. This work proposes a hypothesis that a logarithmic spiral describes the equation of the cross-section of a Greek vase. From extensive measurements, the parameters of such spirals are computed, and explicit formulae are derived for volume based on a few size measurements. The exact formula is quite complex and cannot be easily used, certainly not in antiquity. Therefore, a simple approximation formula is proposed for amphorae, the most important type of vase. This formula expresses the volume of the vase in terms of its diameter and the height of the corresponding solid. The approximation is compared with some exact volume computation results reported for amphorae, and it is shown that the proposed approximation is fairly close to the exact value. The simplicity of the proposed formula suggests an efficient method of calculating volume that was probably known in antiquity.

1. Introduction

A lot of information is known about vases from Ancient Greece. The Greek vase is one way to show that ancient Greek civilization emphasized geometric harmony in art and design [1,2,3]. Scholars such as Boardman [4,5,6], Walters [7], Oakley [8], researchers at the J. Paul Getty Museum [9,10], Matheson at the Yale University Art Gallery [11], and Richter and Milne at the Metropolitan Museum [12] have investigated the artistic narratives and historical contexts of these vases.

The world’s largest dataset of ancient Greek painted pottery is the Beazley Archive Pottery Database (BAPD) at Oxford University [13]. This database contains detailed records on more than 130,000 ancient vases and over 250,000 images. These records include information on vase shape, technique, provenance, inscription, artist name, dimensions, and many other attributes.

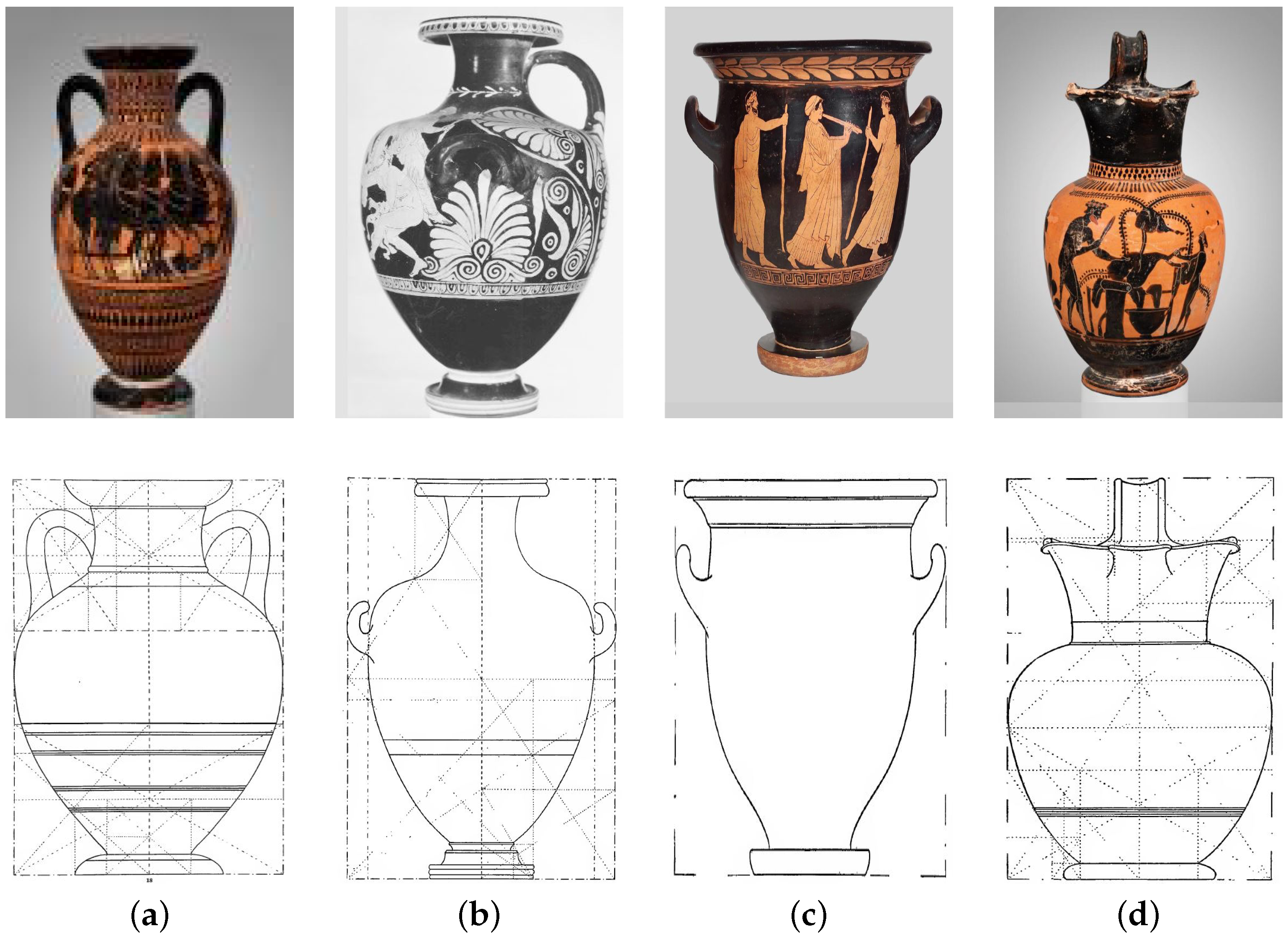

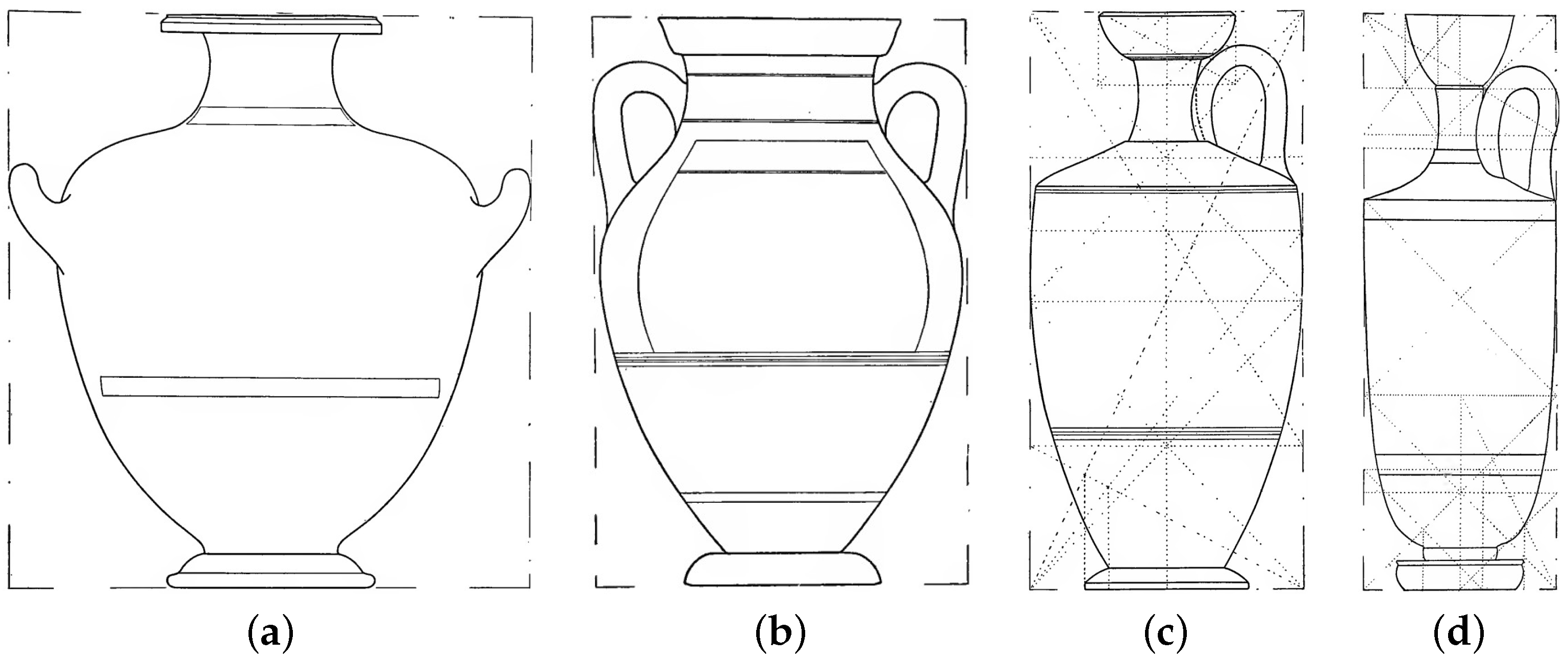

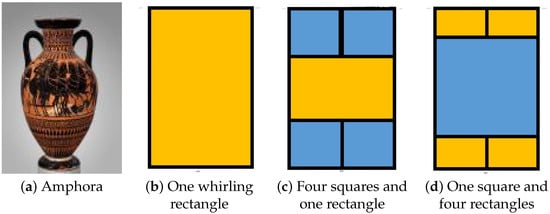

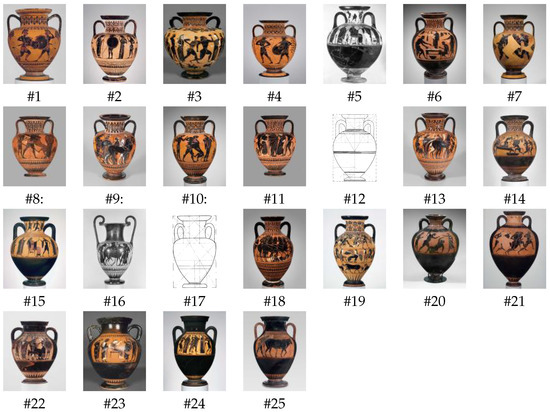

Artifacts in archaeology are often classified by their shapes, and Greek vases are no exception. A typology of some Greek vase shapes from Encyclopaedia Britannica is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Typology of Greek vase forms and primary usage. (A): bell krater (mixing wine and water), (B): lebes (wedding vessel), (C): skyphos (wine drinking cup), (D): aryballos (oils and perfume), (E): hydria (water jar), (F): volute krater (mixing water and wine), (G): kantharos (wine drinking cup), (H): psykter (cooling wine), (I): kylix (wine drinking cup), (J): stamnos (mixing and storage of liquids), (K): alabastron (aromatic oils), (L): oinochoe (pouring wine), (M): lekythos (storing oil and perfumes), (N): amphora (storage and transport of wine, oil, and dry goods).

Of these, the amphora is perhaps the most important type, as it was used for storage, transportation, and trade of wine, olive oil, and other merchandise [14,15,16]. Knowing the count of amphorae and their capacities allows approximate estimation of consumption and trade flows [17].

It is important to distinguish between two broad categories of Greek pottery that served different functions and employed different production standards. Luxury vases—finely painted vessels produced in limited quantities primarily for symposia, religious offerings, and funerary contexts—prioritized aesthetic beauty, artistic imagery, and visual proportion over volumetric precision [6,18]. These vases, which form the primary focus of Caskey’s measurements and consequently of our mathematical analysis, were valued as prestige objects and art pieces rather than as standardized containers [19].

By contrast, utility amphorae—mass-produced transport containers for wine, olive oil, and grain in commercial trade—required greater volumetric standardization to facilitate taxation, pricing, and quality control [17,20]. Archaeological evidence indicates that commercial amphora capacities showed moderate standardization within specific production centers and time periods, though with considerably more variation than modern consumers would expect. For instance, Rhodian wine amphorae of circa 230–200 BCE exhibited capacities ranging from about 25.4 to 29.1 L (variation within roughly of the mean) [20,21]. Similar variation patterns appear in other major amphora-producing regions [17,20].

The mathematical models developed in this paper derive primarily from measurements of luxury vases and are most directly applicable to understanding the aesthetic and geometric principles governing high-quality decorated pottery. The applicability of these logarithmic spiral models to commercial transport amphorae remains an open question requiring separate investigation. While commercial amphorae certainly exhibited proportional relationships between height, maximum diameter, and shoulder dimensions, the degree to which these proportions conformed to specific mathematical ratios (such as , , or ) would need to be verified through systematic measurement of archaeological assemblages from kiln sites and shipwrecks [17,22]. We acknowledge this limitation and suggest that future research examine whether our volume calculation methods can be adapted for commercial amphora types, particularly given the practical importance of volumetric estimation for understanding ancient Mediterranean trade patterns [17].

As noted by Mackay [23], the study of Greek vase shapes has been almost entirely qualitative, with few studies containing numerical data or explicit tables [24]. Many of these focus on the direct measurement profiles (the outer shape) of a vase. It is also possible to design machine-learning classifiers to analyze shapes from the vast number of photographs available in the BAPD and other databases [23].

What is largely missing from this literature is an accurate estimate of vase volume. As noted in recent work on vessel capacity [25], calculating the volume of ceramic vessels found whole or in fragments on archaeological sites is a key analytical endeavor that can have implications for economic and social activity, including storage, feasting, and trade. Direct measurements of volume are often infeasible due to age, condition, cracks, and restoration issues. As a result, other methods are needed, many of them based on advances in digital imaging and computer-assisted reconstruction [25,26]. Most established methods for estimating volumes are based on the assumption that vessel shapes approximate circular or elliptical forms in plan view, or on other geometric simplifications [25].

In this work, we make extensive use of square roots that appear in the dimensions of Greek vases. The geometric construction of and the proof of its irrationality were well known at the time of Euclid. Procedures to compute and similar square roots or approximate a hypotenuse were known to Babylonian mathematicians around the 16th century B.C.E. [27]. It is unlikely that the Greeks would use such complicated formulae or even later formulas, such as Heron’s method [28] or Archimedes’ (3rd century B.C.E.) methods of continuously improving and estimating upper and lower bounds using simpler solids [29]. Most likely, they used simple fractions that are fairly close to these square roots. For example, , , and . Artisans of the time could likely reproduce the same proportions without any numerical concept of square roots (e.g., , , ) by relying solely on geometric constructions (squares, diagonals, circular arcs, and cord/straightedge/compass). It is also interesting to note that the measuring system used in Ancient Greece involved only a few simple fractions, such as and [30]. Therefore, although irrationals like square roots were not numerical tools at the time, artisans could set shapes without using , , directly, but by using corresponding simple fractions.

One should note that many of the mathematical constructs known to the Greeks were already known in Ancient Egypt [31,32,33,34,35]. One of the primary sources of Ancient Egyptian mathematics is the so-called Rhind Papyrus [36]. This document, from the northern part of Egypt, dates from about 1650 BCE. This papyrus, just as a few others that we have today (e.g., the Berlin papyrus and the Moscow papyrus), contains both arithmetic and geometric problems and their solutions. For example, one of the most famous problems is problem #48 in the Rhind papyrus, which suggests the number as . This is a very close approximation (about 0.5% relative error) to when rounded to 4 decimal points. A number of problems in the Rhind papyrus are related to computing volumes of cylinders (problems 41–43), rectangular solids (problems 44–46), and a few other geometrical problems computing volumes (cylinders and pyramids) and areas (problems 48–60). There are no mentioned problems dealing with computing volumes generated by rotation, except for the cylinders.

Before Euclid provided proofs and rules for geometric ratios, the Egyptians had already invented mathematical rules and construction techniques [37]. Rossi [35] has shown that the Egyptians used limited geometric tools to control dimensions, often relying on grids and proportional settings. They could draw circles, squares, triangles, and vertical lines to measure and construct buildings and utilities, and were especially skilled at squaring and aligning long structures, as well as constructing right triangles. At that time, geometry was a practical activity that involved using ropes and measurements rather than abstract numerical concepts or formulas. The pyramid slope (sequence), which expresses a ratio geometrically, is another example. Many temples and pyramids can be explained by practical geometry. For example, the Egyptians applied mathematical rules in pyramid construction by first establishing a base square on the ground, marking the pyramid’s center, drawing the vertical height from that center, using the seqed to determine the face’s slope, and then using a measuring rod or squared grid to mark this distance to complete the pyramid’s floor plan [35]. This procedure represents geometry based on mathematical rules and construction techniques without relying on numerical theories or formal formulas.

The Greeks observed, abstracted, and applied this practical knowledge from the Egyptians to create harmonious shapes such as squares, diagonals, and arcs. Coulton’s study showed that Greek architects used cords, measuring rods, and right-angle tools to draw building parts, such as squares and diagonals, directly on working surfaces. It means that the Greeks obtained the same proportions through drawing without any numerical concept of irrationals. They used a common method, which involved choosing a module and drawing it repeatedly. If they consistently constructed the same modules in the same way, they would eventually achieve the same proportions. More specifically, they could draw a square as a module, then its diagonal, and use that diagonal as a new length or intersect arcs from fixed points, repeating these operations to produce the same ratios [38]. This demonstrates that geometric ratios can be reproduced through repeated construction procedures rather than through numerical calculations. Hahn argued that Greek artisans, before Euclid, used plumb lines, cords, or straightedges to square, draw diagonals or perpendiculars, and inscribe circles in their constructions [39]. These operations created order and proportion without naming them. The Greeks followed these operations from the Egyptians and reproduced the same geometric ratios, such as the golden ratio and root rectangles [40]. Euclid later summarized and transformed those practical rules and construction techniques into a formal mathematical system that included definitions, propositions, and proofs.

However, it is crucial to distinguish between the foundational geometric principles that the Greeks learned from Egypt and the sophisticated refinements they independently developed. While the Egyptians provided practical geometric methods for construction [32,35], the Greeks advanced far beyond these foundations, developing techniques unknown in Ancient Egypt. Notable examples include entasis—the subtle convex curvature of temple columns designed to correct optical illusions and potentially enhance structural strength [41,42]—and the precision construction of column drums that fit together with tolerances accurate to fractions of a millimeter [38,43]. Greek architects also employed non-planar temple floors with intentional curvature to counteract visual sagging [42] and achieved remarkable accuracy in tunnel construction through sophisticated surveying techniques [44]. These refinements represent distinctly Greek innovations in architectural and engineering precision that went well beyond the practical geometry of Egyptian rope-and-grid methods. The mathematical principles underlying Greek pottery design studied in this paper should be understood within this context of Greek geometric sophistication, not merely as applications of imported Egyptian knowledge.

Currently, there is an increased interest in calculating the volume of vessels to assess commodity trade transported in sharp-bottomed amphorae [15,22], including the pithos (“pythoid” or ovoid) amphorae. As pointed out in [45], “…Ancient Egyptians could calculate the volume of a sphere correctly, and Democritus (5th–4th centuries BC) was the first to calculate the volume of a cone correctly. However, until now, it was not known that there was a formula for calculating the volume of an ovoid amphorae body during antiquity. Formulas by Heron of Alexandria (1st century AD) for the volume of “pithoid” and “spheroid” pithos are known. However, Heron did not specify the meaning of some terms in these formulas. Therefore, the geometry of these vessels and the exact meaning of the formulas have remained unclear.”

The contribution of this work: In this paper, a novel approach to computing vase volumes is proposed. It is based on ideas of dynamic symmetry of Hambidge [46]. A conjecture is proposed that the shape of a Greek vase is described by a logarithmic spiral. With this assumption, an explicit formula for vase volume is derived. The exact formula is quite complex, and therefore, some simple approximations are considered. Results are compared with computer-based approximations based on profile analysis and show that the suggested approximations are quite precise. Approximation results are compared with exact volume computations reported for some vases and the proposed approximations give close results. The obtained results suggest a simple way to compute the volume that could be used in antiquity.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a summary of some of the existing methods for computing vase volume, including a comparison of volume units used in antiquity. Section 3 reviews some background on the “dynamic symmetry” by Hambidge as applied to Greek vases. Section 4 presents an alternative explanation for the logarithmic spiral for the contour of the vases. Section 5 provides some geometric background on self-similar rectangles and the construction of logarithmic curves. The self-similarity in Greek vases is illustrated with additional examples. Appendix A describes a workshop protocol that ancient potters would probably use to realize the vase proportions. Section 6 reviews Caskey’s dataset used in the computation of volumes. In particular, some details on the statistics of different ratios are provided. Section 7 presents the derivation of the exact formulae for computing vase volumes (with some derivation details presented in Appendix B and Appendix C) and compares them with the values obtained by numerical integration. Section 8 presents some approximations and explains them in terms of volumes of simple solids. Section 9 presents a number of case studies to illustrate the suggested approach, including the detailed computations and comparison with exact values reported for the amphorae at the Getty Museum and with a set of amphorae from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). Results and final conclusions are presented in Section 11.

2. Volume Computation Methods

The problem of computing vessel volume is an ancient one. The volume of a sphere was known to the Ancient Egyptians. The formula for the volume of a cone has been known since the 4th century B.C.E. (by Democritus). The volume of an ellipsoid of revolution was probably suggested by Archimedes (3rd century B.C.E.), and the formulas for spheroid and pithoid were computed by Heron of Alexandria around 100 B.C.E. (for a detailed discussion, see [45]). As noted in [45], the geometry of some of these vessels and the meaning of some formulas remain unclear. The computation of the volume of ancient vessels is therefore still relevant and important.

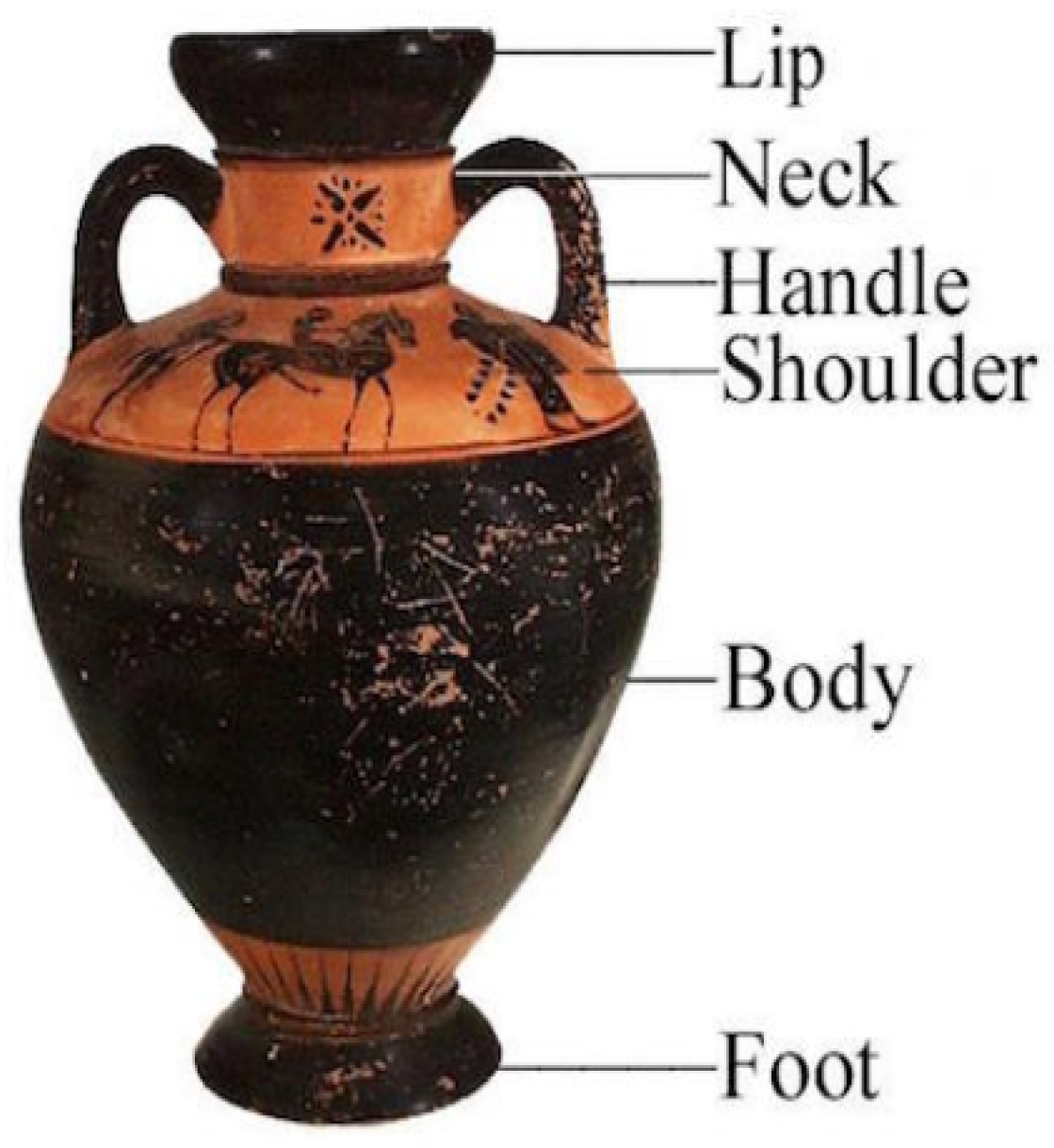

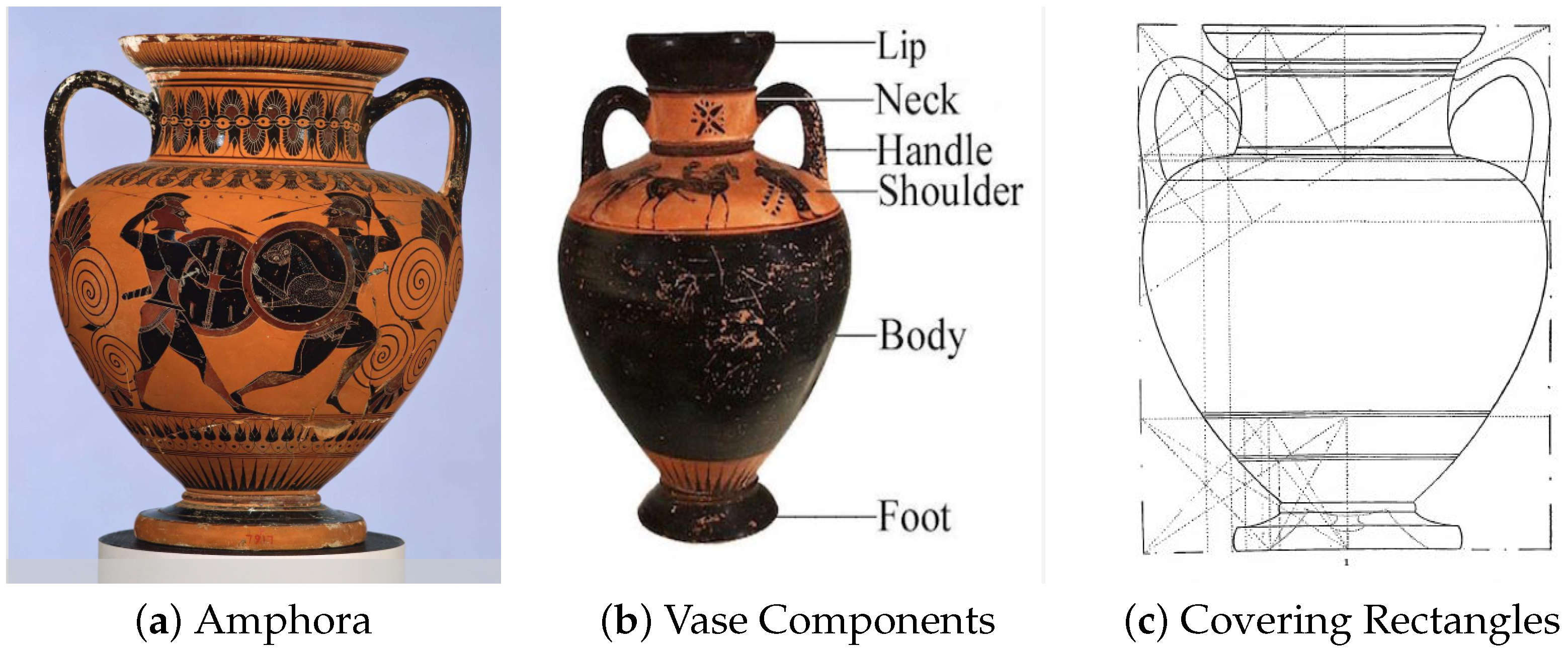

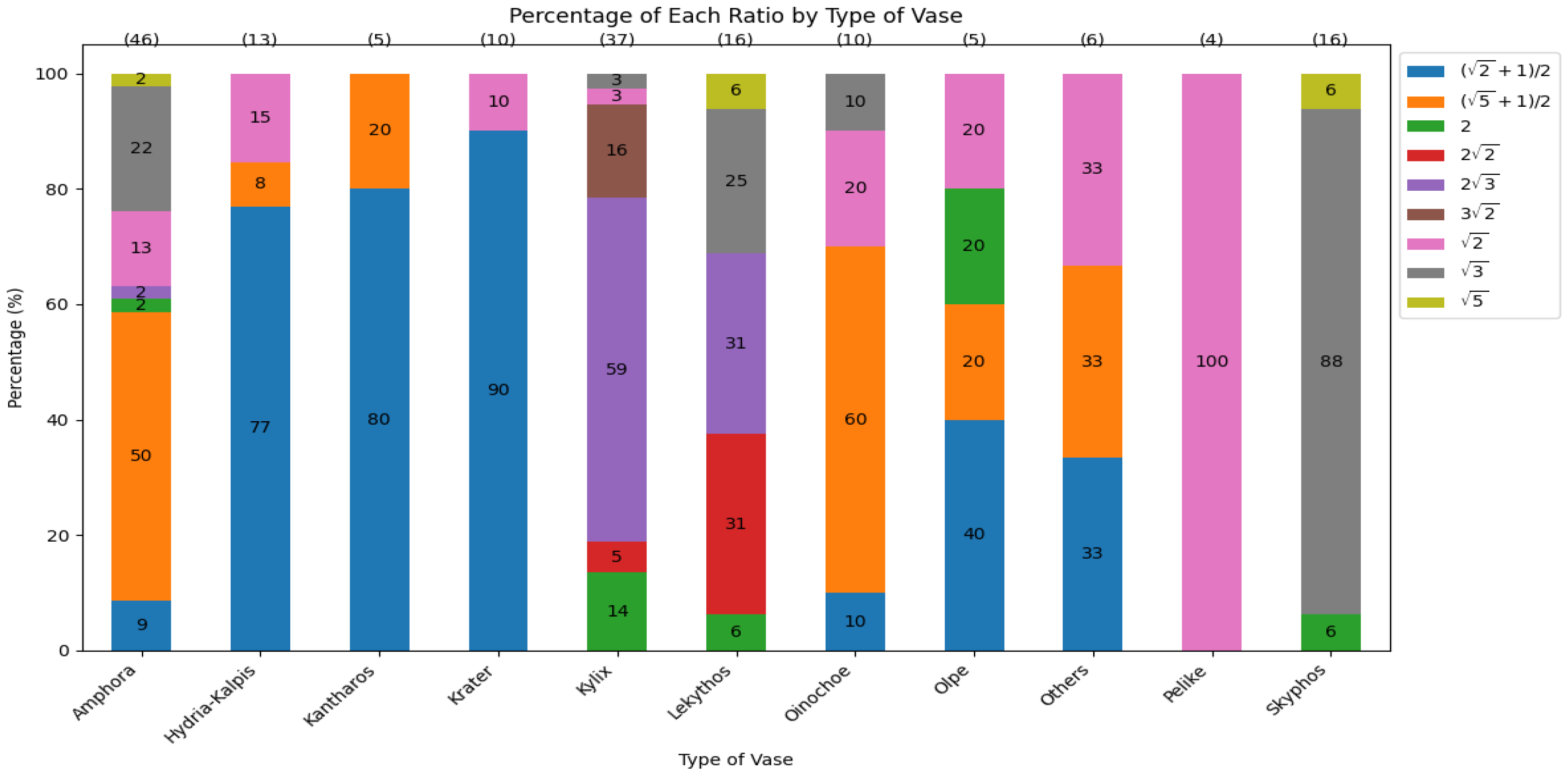

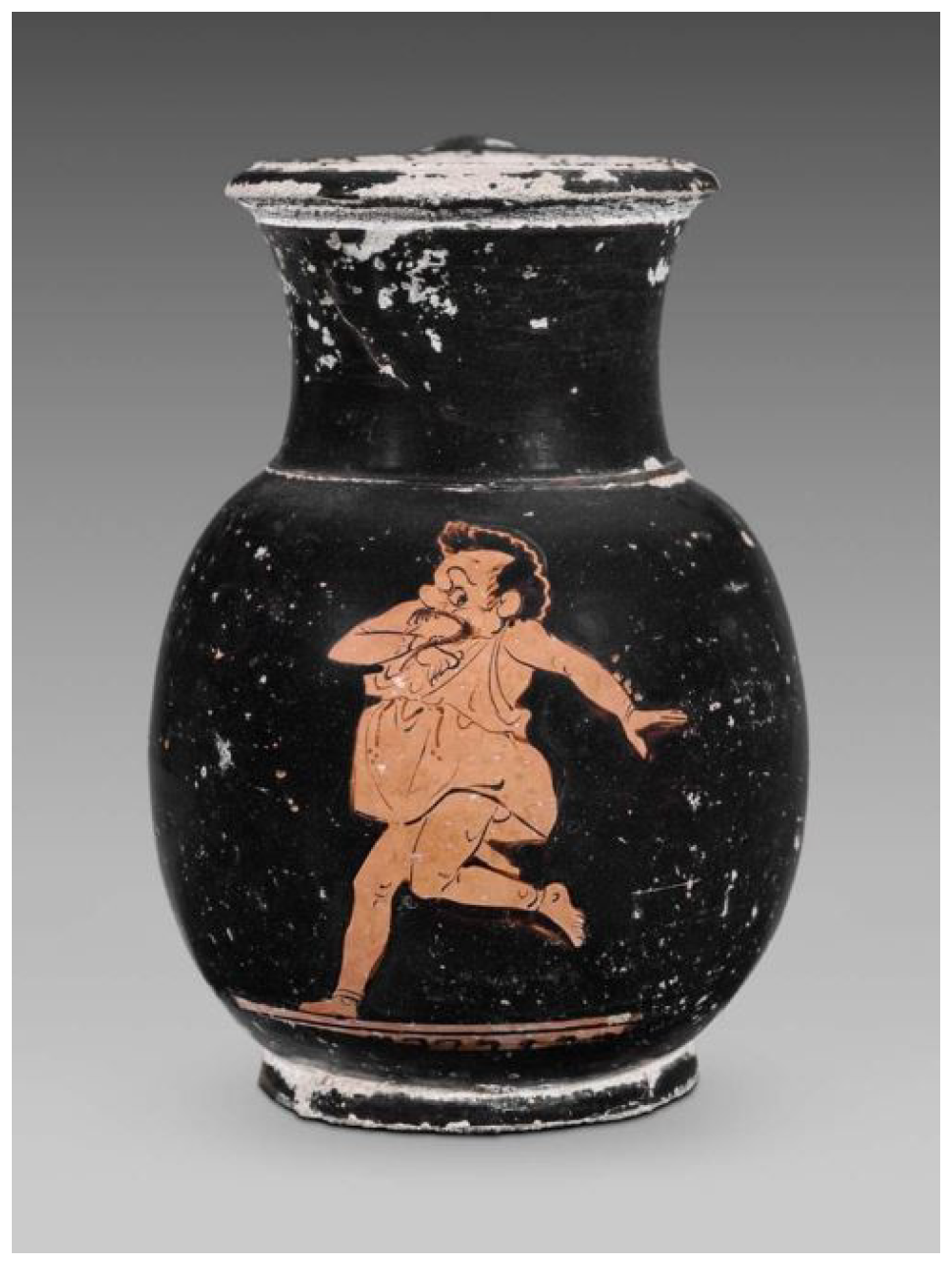

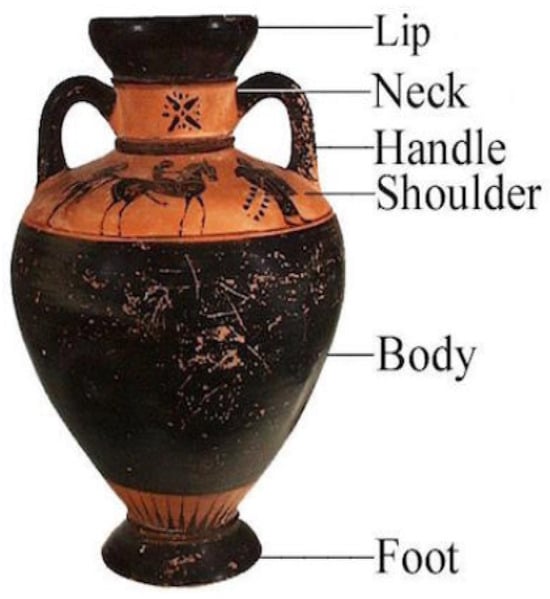

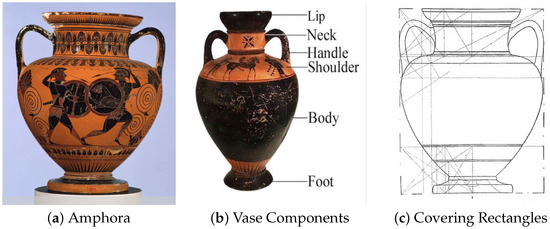

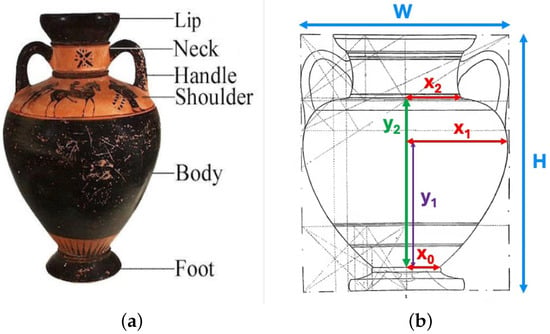

We start our discussion by illustrating the vase components in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Vase components. Vases consist of several parts. The lip is the edge of the opening. The neck is a narrow section that connects the lip to the body. The body is the main container of the vase. The shoulder is the location where the body curves in, providing a smooth contour. The stability is provided by a foot. Finally, vases like amphorae often have handles for easier handling or decorative purposes.

Note that there is no standard definition of the volume or capacity of a ceramic vase. One possibility is the maximum possible capacity when the vase is filled to the top of the lip. Another is the so-called “effective” volume of a vessel [47] where the container is considered full. For the purpose of this paper, the effective capacity is the capacity to the shoulder. One can consider the following volume estimation methods [48]:

- Fluid volume method: Measure the volume of the water. This is a simple and straightforward way, but it has some limitations, such as water absorption, fragmented vessels, or fear of damage.

- Dry volume method: Measure the volume using some solid material such as lightweight polystyrene packing material.

- Density method: Estimate the volume by estimating the difference in weights of a vase filled with filling material, an empty container, and using the density of the filling material to compute the volume.

- Using volumes of geometric solids. In this approach, standard geometric shapes to estimate volume are used [49,50,51,52]. The simplest possibility is the frustum: if a and c are the radii of the bottom and the shoulder of the vase, and H is the height from the bottom to the shoulder, then the volume of the frustum is

If the vase is not circular and can be better described by an ellipse with bottom radii a and b and shoulder radii c and d, then the volume of such an elliptical frustum becomes

- 5.

- Stacked-cylinders method: In this method, one computes the volume as a sum of stacked cylinders. The height is divided into n cylinders with radii and heights . The total volume is computed as the sum of volumes of these n disks:

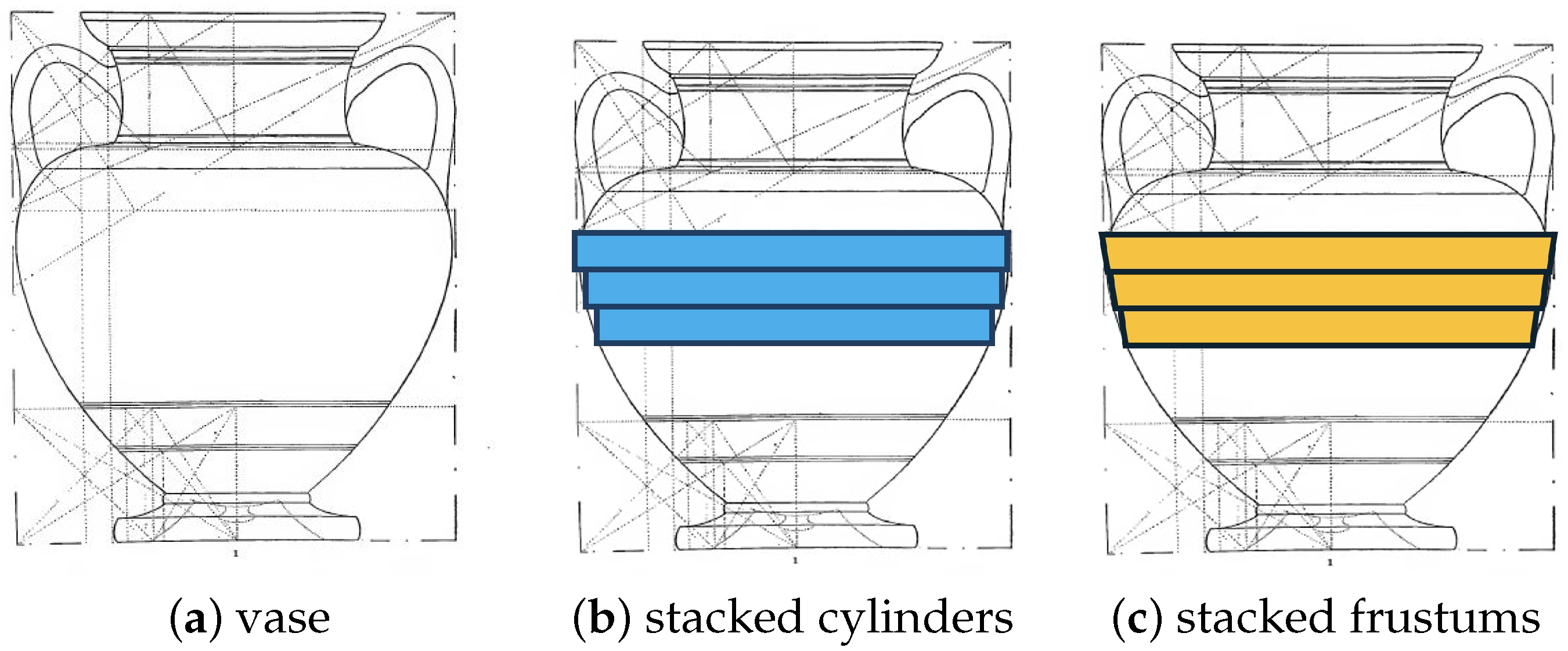

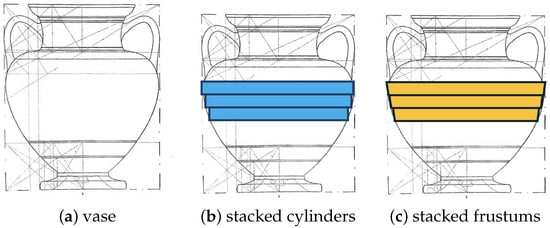

This is illustrated in Figure 3b:

Figure 3.

Computing volumes by stacked solids. In this method, one slices the vase container region (a) into several cylinders (b) or frustrums (c). The volume of each stacked solid is computed, and the total volume is approximated by summing the volumes of these solids.

This requires computing the radii of the cylinders—these can be estimated from a photograph without the physical presence of a vase [53]. Note that this method assumes the circular form of the vase. Unless one takes a very large number of cylinders, this method significantly underestimates the vase volume [25]. This issue can be resolved programmatically, and several solutions are available. For example, a computer program developed at Université Libre de Bruxelles (https://capacity.ulb.be/index.php/en/—last accessed on 15 October 2025) allows one to upload the profile picture and specify the height of the vase. The application estimates the volume by adding small cylinders to give very accurate estimates of the volume. This program is used to compare our results.

- 6.

- Stacked frustums (bi = level cylinders): In this method height H is divided into n slices. Each slice i is a frustum with bottom radii and top radius and heights . The volume is then the sum of volumes of these n frustra (see Figure 3c).As pointed out in [23], methods that assume circularity produce less accurate volumetric estimates than approaches that accept that a less regular elliptical shape may be closer to reality. Statistical analysis allows the accuracy of the different methods to be compared and evaluated.

- 7.

- Integrating the profile curve around the axis of symmetry: To use this, one needs to know the equation that fits the vessel profile [54]. In [55], a polynomial expression is derived for each vessel profile. This could be accurate if these polynomials describe the profile shape accurately. One disadvantage of the methods is that there is no recipe to choose such polynomials. Many profiles cannot be described by low-degree polynomials, such as parabolas, since these profiles do not appear symmetric, leading to possible large errors.

From a mathematical standpoint, if a generic explicit equation for the profiles is known, then volume can be calculated by integrating this equation around the y axis of symmetry. This provides an explicit closed-form formula for the volume and a universal approach to consider approximations. In this paper, such a universal approach is suggested based on the so-called “dynamic symmetry” of Hambidge [56]: Analyzing self-similarity in vase design yields a logarithmic spiral equation for the profile. From this formula, a closed-form expression for the vase volume is obtained.

It is interesting to compare standard units for liquid measurements in Ancient Greece and other regions [30]. This is shown in Table 1. Note that the units in Ancient Greece relate to each other via simple ratios of 2 and 3 (and their combinations like 4, 6, 12). There are no 5 or 10 factors that are found in other systems like Ancient Rome or Mesopotamia.

Table 1.

Common liquid volumes in the ancient world (1 Liter = 1 dm3) and corresponds to the weight of 1 kg for water.

Compared to other regions, the system of units in Ancient Greece appears to be much simpler. A similar simplicity in terms of geometric ratios and shapes is observed in the geometry and structure of Greek vases, as suggested by the theory of “dynamic symmetry”.

3. “Dynamic Symmetry” of Jay Hambidge and Greek Vase

Jay Hambidge (1867–1924) was an American artist who formulated the “dynamic symmetry” theory as a geometric basis of artistic design [56,57,58,59], including Greek vases [46]. According to Hambidge in his introduction [58], “…Symmetry is the rhythm base of design. It is impossible to introduce rhythm into design components without first introducing symmetry…”.

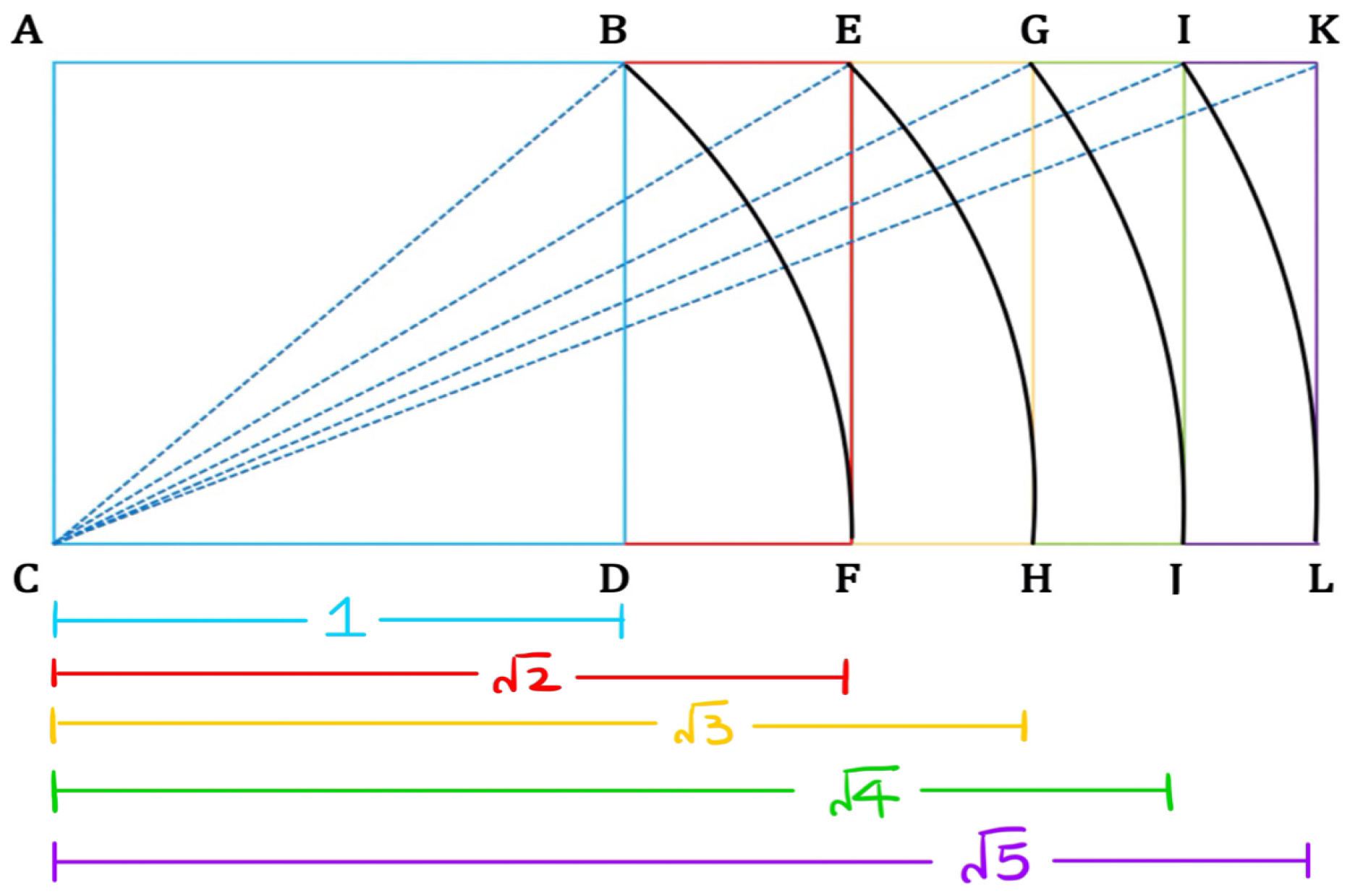

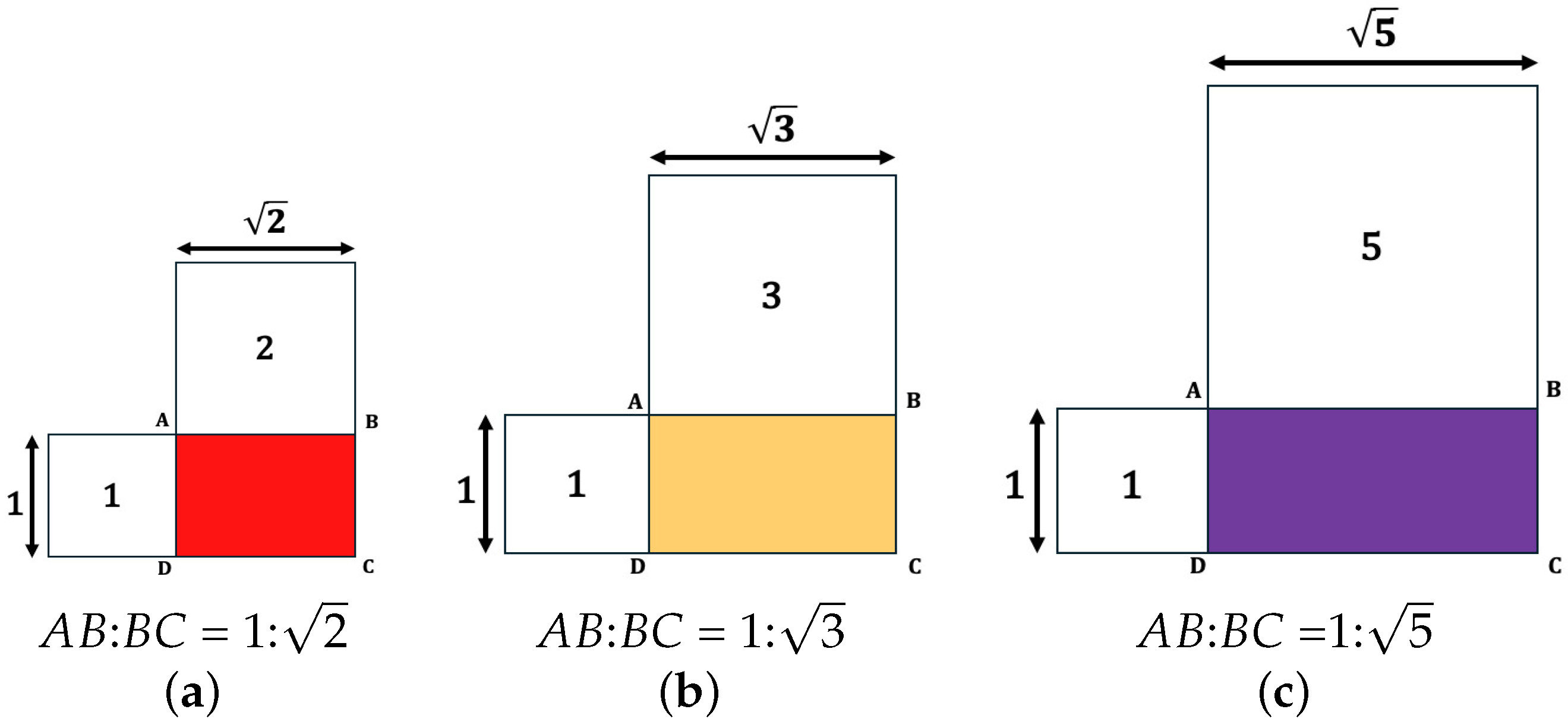

The base of symmetry, according to Hambidge, is squares and rectangles. The symmetry itself can be static or dynamic. If an area is composed of squares (or equilateral triangles), then it has a static symmetry. By contrast, in dynamic symmetry, one uses squares and dynamic rectangles. In the language of modern mathematics, these are self-similar rectangles described in more detail in Section 5. In dynamic symmetry, these rectangles have ratios of length to height as (“root-two” rectangles), (“root-three” rectangles), (“root-five” rectangles), and their inverses and variants such as “silver” or “golden” ratio (“whirling square” rectangles). The important feature of these rectangles is that they are “incommensurable”: the ratio of length to width can only be expressed as never-ending fractions. Dynamic symmetry, therefore, is expressed by root rectangles (or their inverses) whose lengths are incommensurable but are measurable in squares. Although square root lengths , , and are not commensurable, their construction by using a compass and a straightedge was known in Ancient Greece and is illustrated in Figure 4.

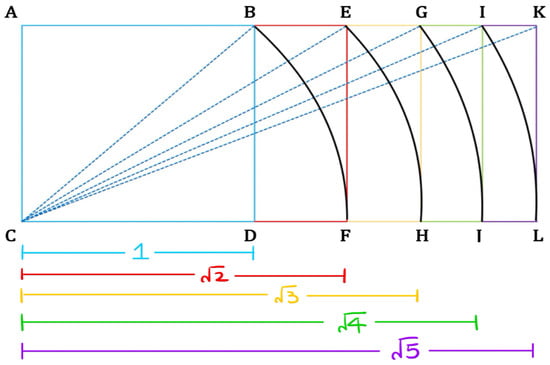

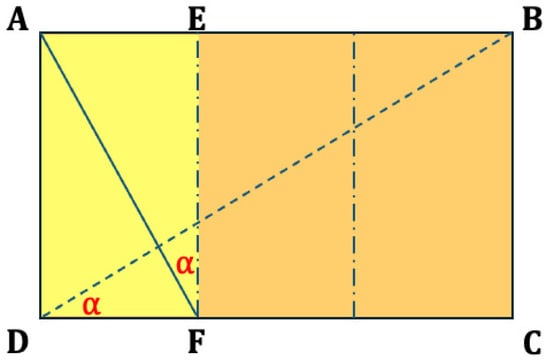

Figure 4.

Construction of square root lengths and root rectangles. The construction starts with the unit square . Its diagonal has length . Using a compass, one constructs the point F with length . The new root-2 rectangle has sides 1 and . The diagonal of the root-two rectangle is and determines the root-3 rectangle . In this manner, all consecutive root-n rectangles can be constructed.

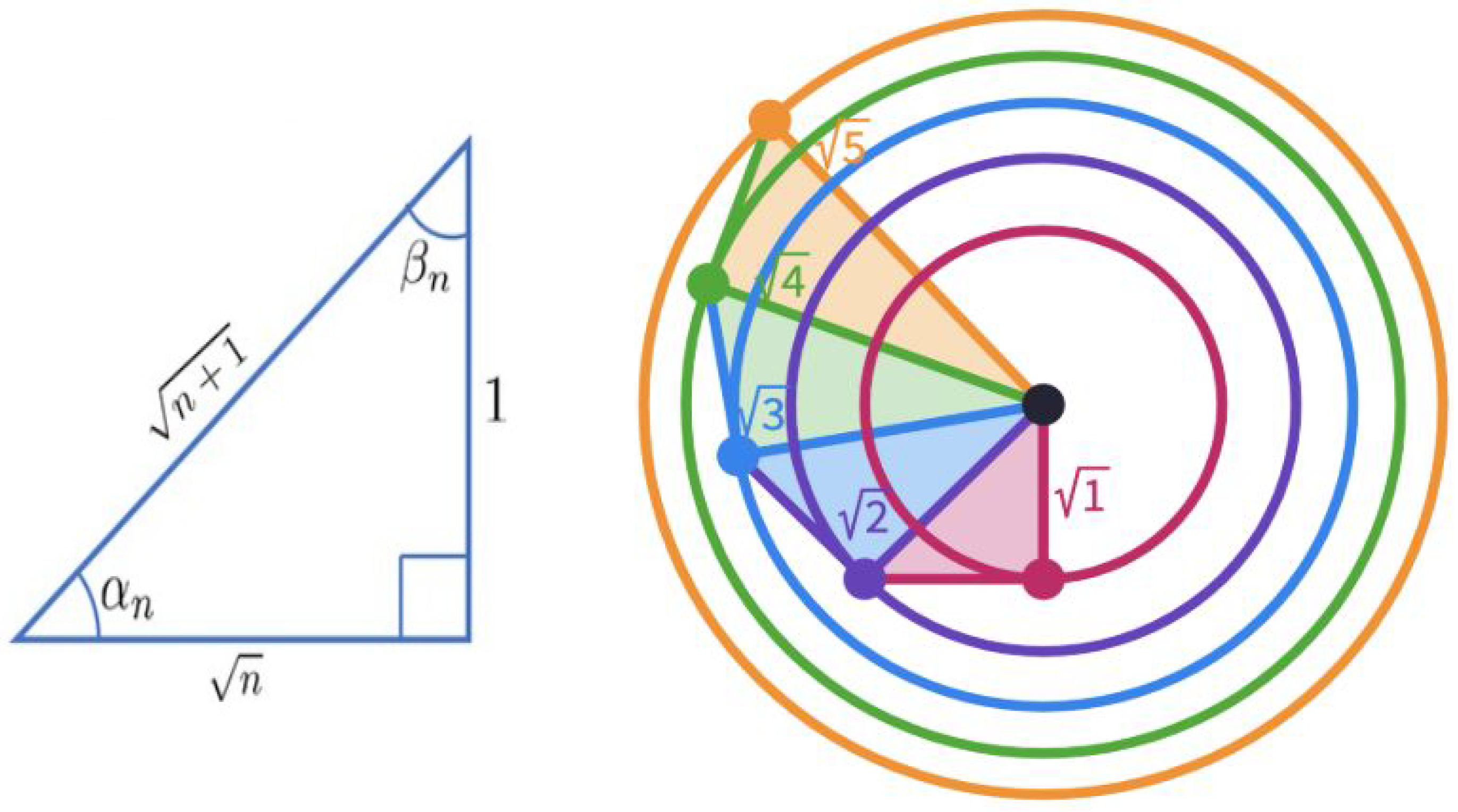

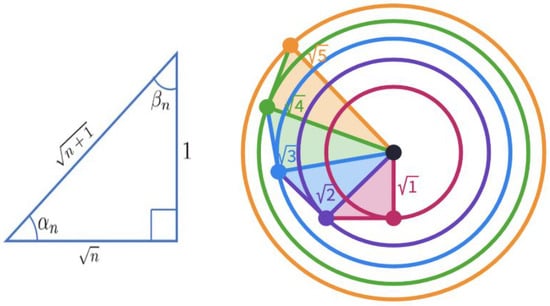

There are other methods of constructing these lengths that were known in ancient Greece, such as the spiral of Theodorus [29] in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Construction of square root lengths with the spiral of Theodorus. This method is an alternative way of geometrically constructing square roots using the so-called spiral of Theodorus, an Ancient Greek mathematician, mentioned by Plato in [60]. In this spiral, one constructs a series of right triangles with hypotenuses of lengths , as shown on the left. The hypotenuse of each triangle becomes the side of the next right triangle, as shown on the right.

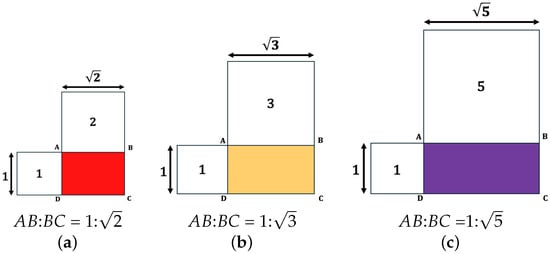

Once these lengths are constructed, one can construct root rectangles. These rectangles are shown in Figure 6. Note that dynamic symmetry is built around rectangles, not just the commensurability of areas. An ellipse and a circle with twice the area of an ellipse are not an instance of dynamic symmetry [61].

Figure 6.

Illustration of root rectangles. In dynamic symmetry, root rectangles are based on square root proportions. Their edge lengths are “incommeasurable” (can only be expressed in never-ending fractions) and cannot be divided into one another. However, a square constructed on the long side of such rectangles can be expressed in whole numbers relative to a square constructed on the shorter side [46]. (a) Root-two; (b) root-three; (c) root-three.

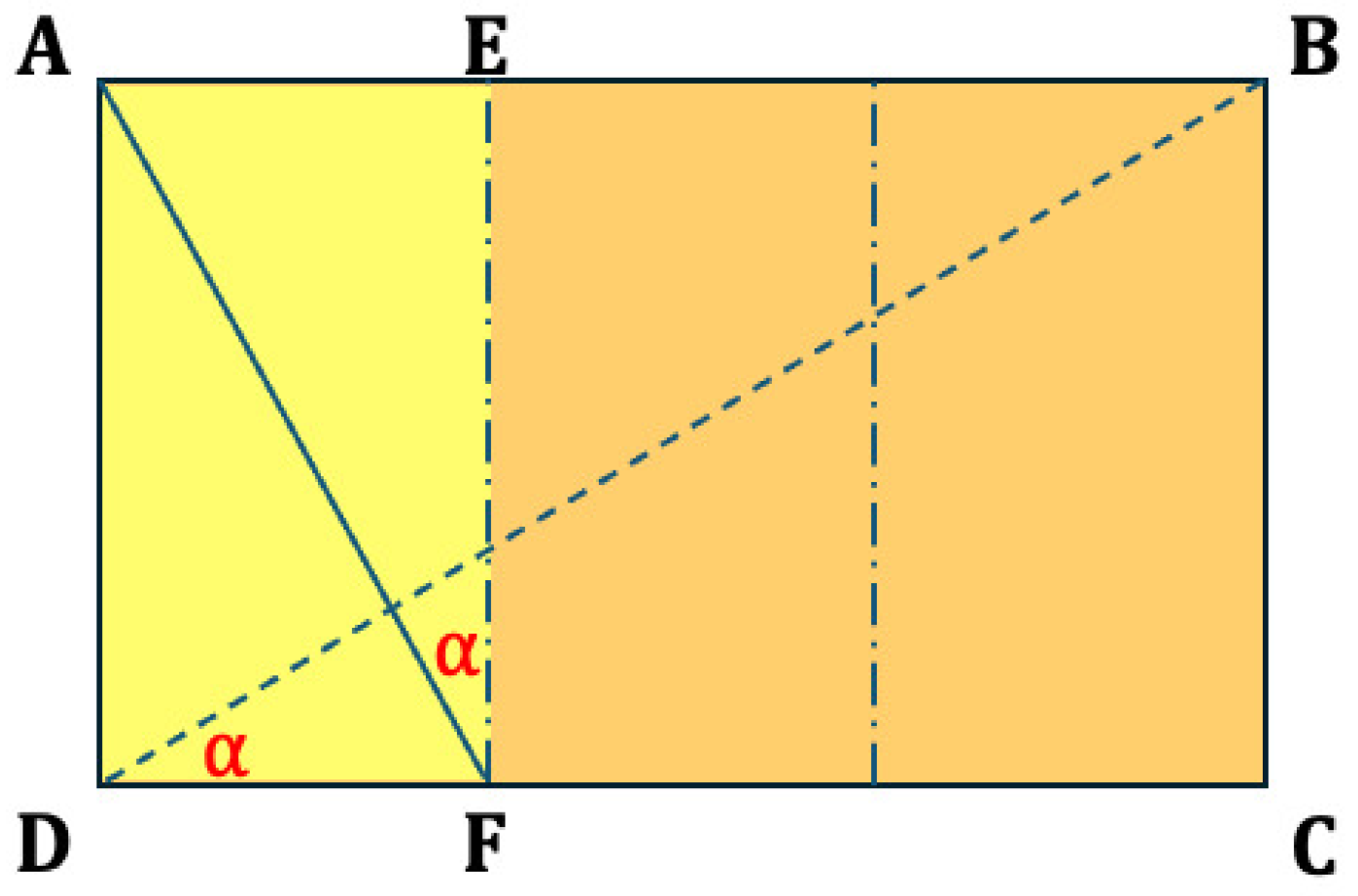

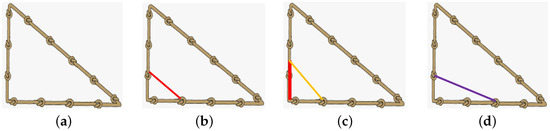

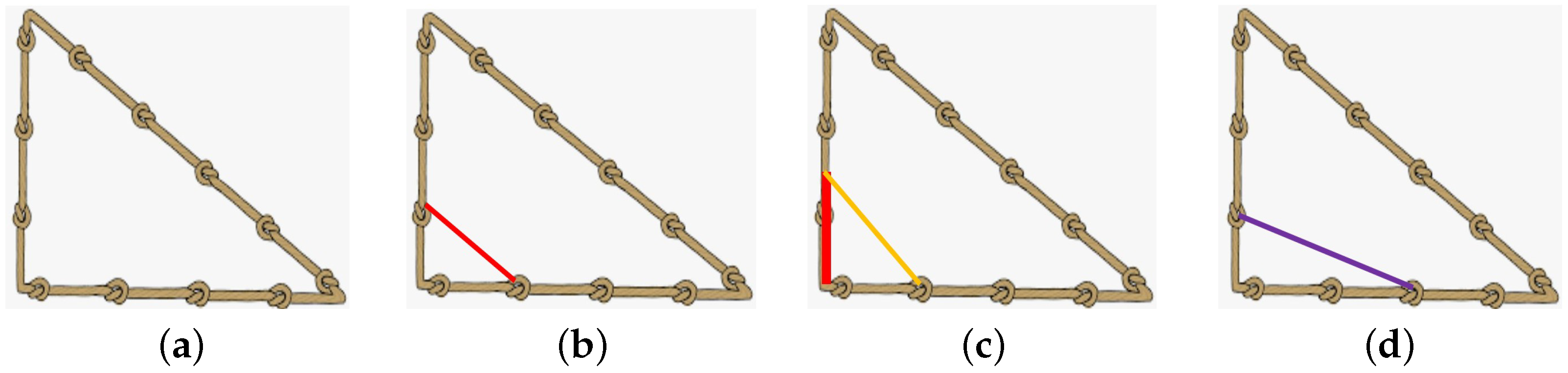

From these root rectangles, reciprocal triangles can be constructed by drawing diagonals and perpendicular lines. The construction of a reciprocal root-three rectangle is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Constructing reciprocal root-three rectangle. One takes a root-three rectangle and draws a diagonal . From vertex A, the segment is drawn perpendicular to the constructed diagonal . It is easy to show that triangles and are similar to each other giving : = : or :1 = 1:. This results in .

In this figure, one takes a root-three rectangle and draws a diagonal . From vertex A the segment is drawn perpendicular to the constructed diagonal (Figure 7). It is easy to show that triangles and are similar to each other giving : = : or :1 = 1: giving = 1:.

The dynamic symmetry of Hambidge is based on the proportion of such root-square rectangles. Many artists have promoted this theory in analyzing art and architecture [62,63,64,65] (for a survey, see [66,67]). In particular, one of Hambidge’s disciples, Lacey Caskey [68] performed extensive measurements at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the 1920s and published detailed drawings and measurements of the extensive collection of Ancient Greek vases available at the museum in his book A Geometry of Greek Vases [68]. In particular, he found that the same type of vases could be described by rectangles with the same length ratios. These ratios of Greek vases vary according to Caskey’s measurements, but most of them can be categorized into groups such as the golden ratio [69,70,71]. These ratios for vases are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Common ratios k of height H to width W for vases and simple fraction approximations.

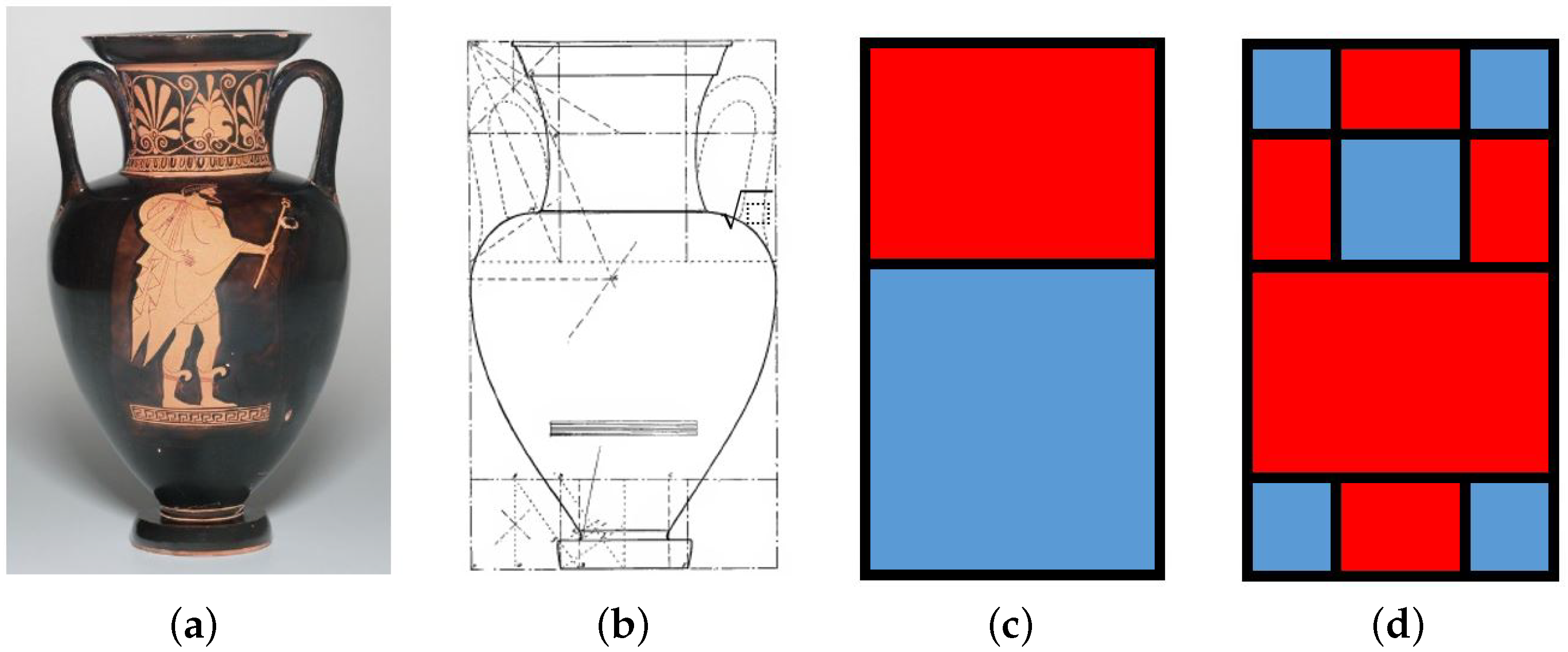

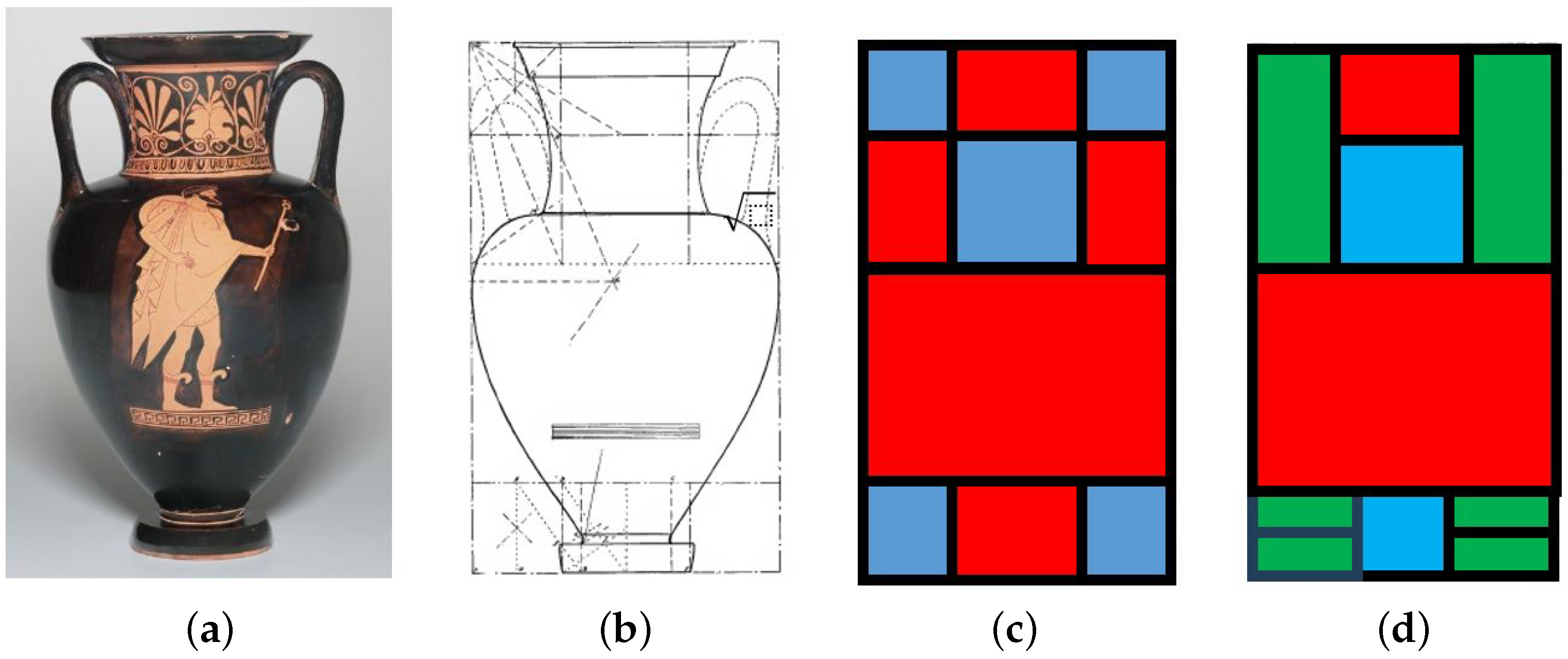

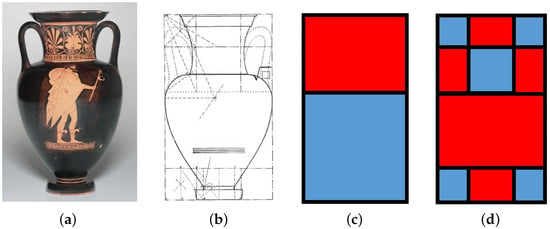

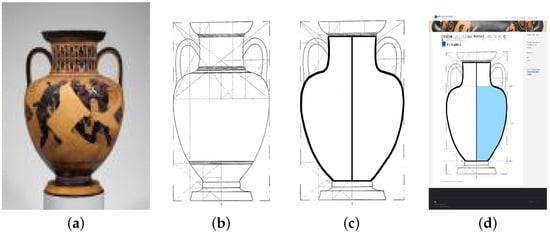

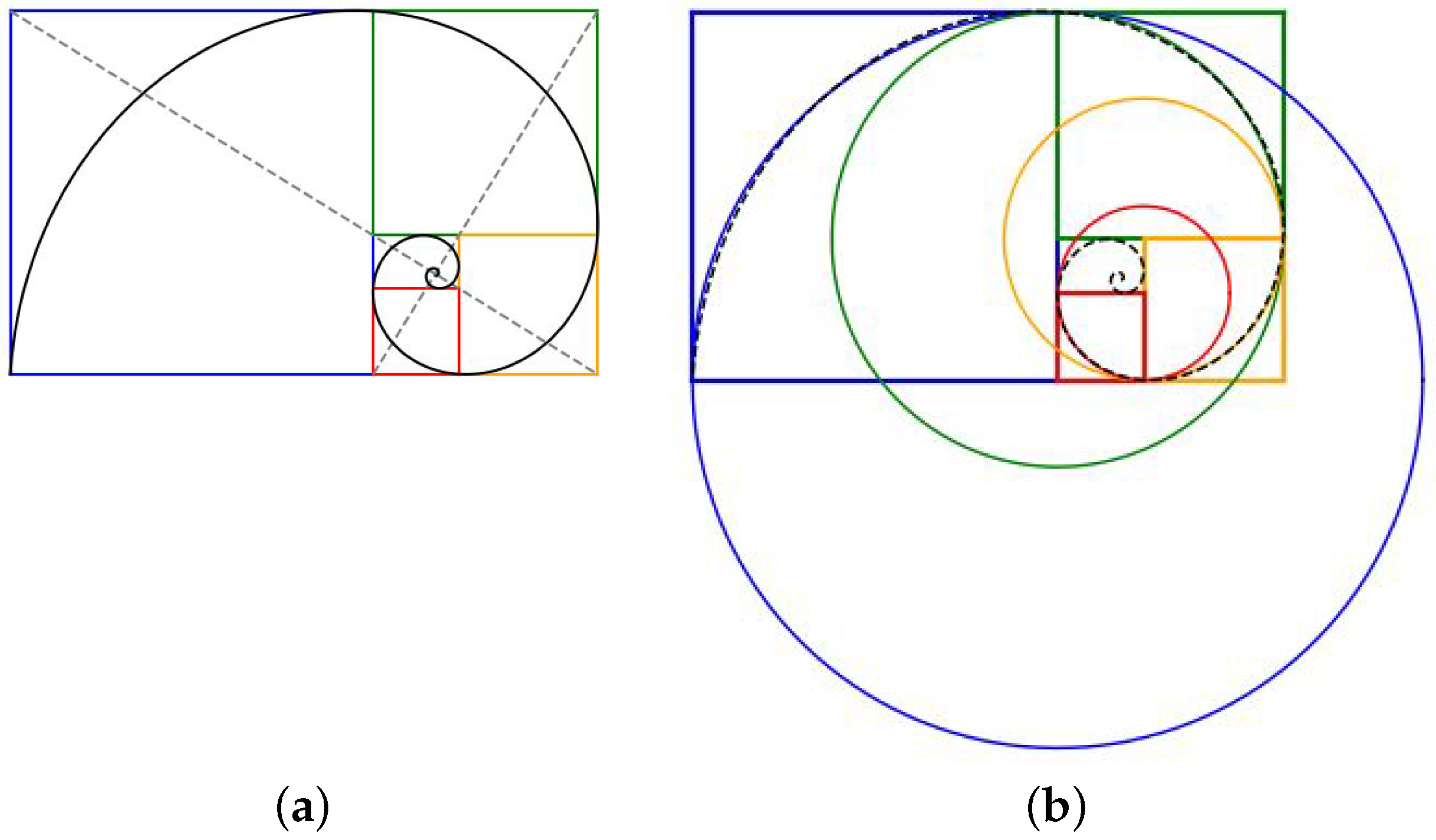

Consider an example of a Greek vase, describing size components, covering rectangles, and Caskey’s measurement computations. To start, consider the very first example in Caskey’s book, neck amphora #1, page 36–37, depicting two fighting warriors. Details of this vase can be found at https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153414 (last accessed 15 October 2025).

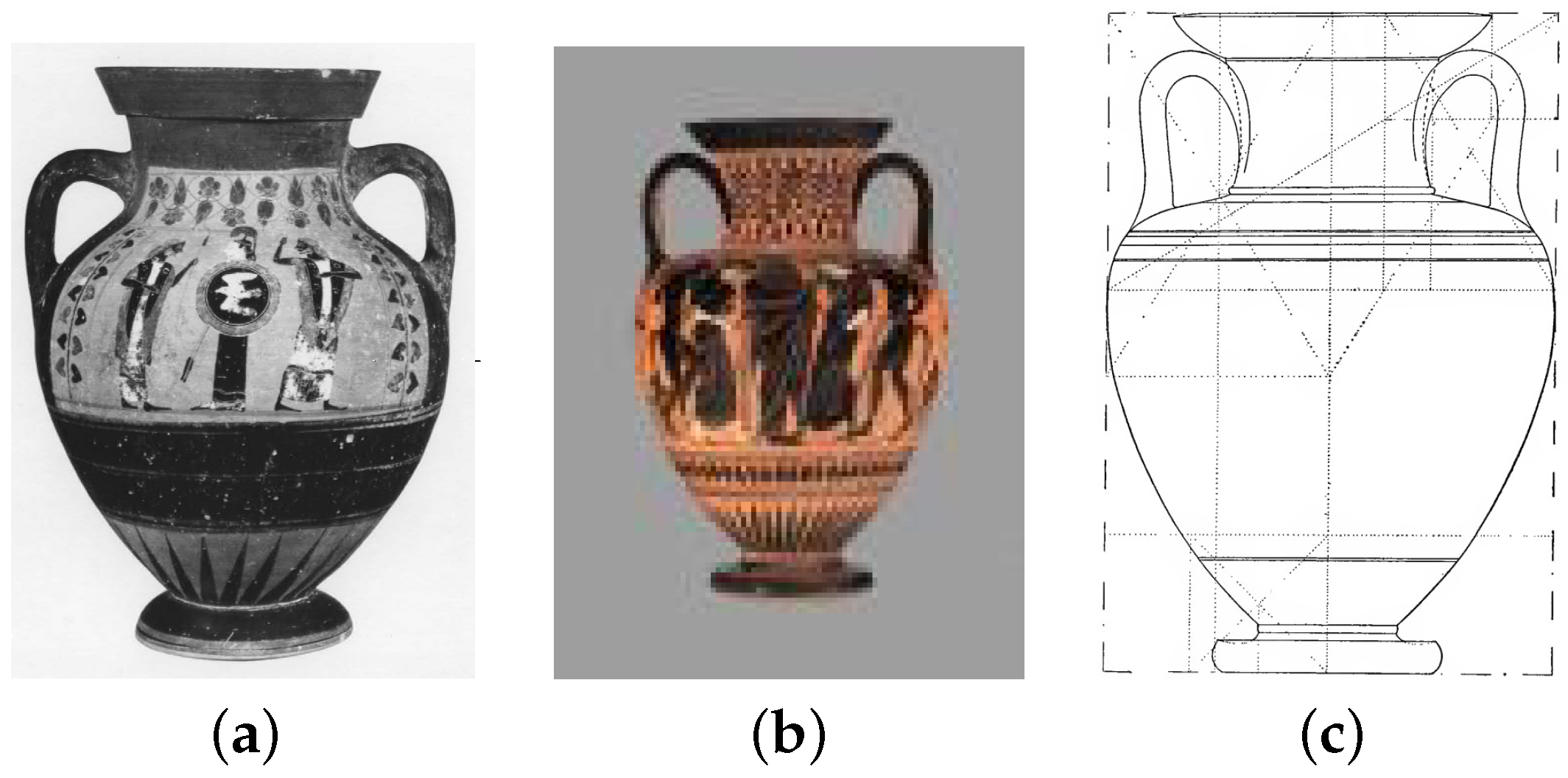

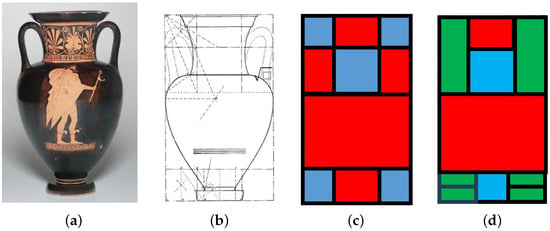

This vase is illustrated in Figure 8. The generic measures for vases are shown in Figure 8a. Figure 8b shows the vase itself, whereas the covering rectangles for this vase are shown in Figure 8c.

Figure 8.

Greek vase and covering rectangles. The central idea of dynamic symmetry is that for a Greek vase (a), its components (b) can be inscribed in self-similar rectangles (c), all with the same ratio of height to width.

For this vase, the height is cm. Its width, handle to handle, is cm. The diameter of the bowl is cm. The diameter of the lip is cm. Finally, the diameter of the foot is cm. To compute the covering rectangles, Caskey “normalizes” the width of the vase as 1 and looks for ratios from detailed measurements for vases. For this particular example, Caskey’s “normalized” values for the above vase are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example of relative vase measurements (in terms of the width, ).

In the above example, Caskey shows that covering rectangles are based on .

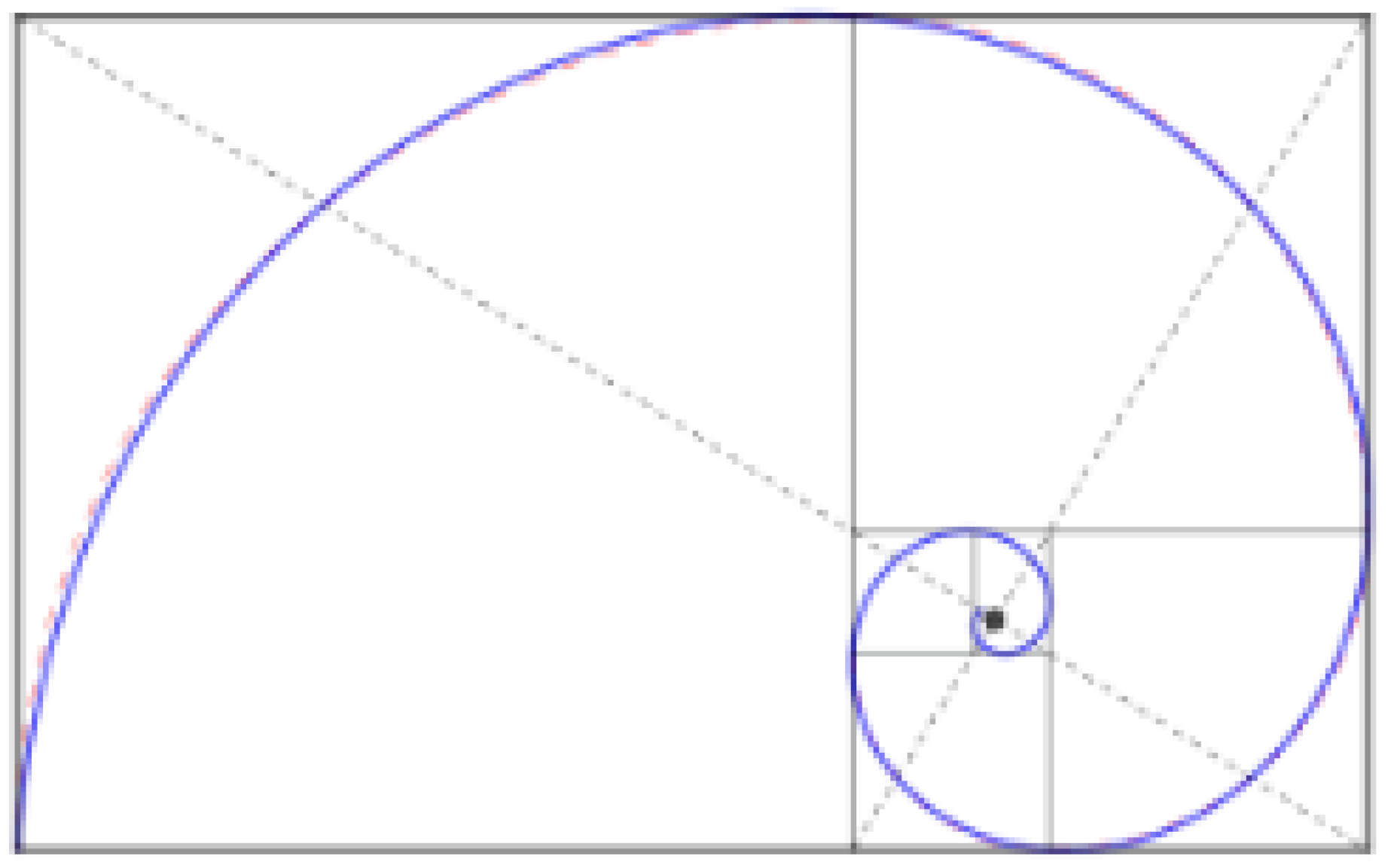

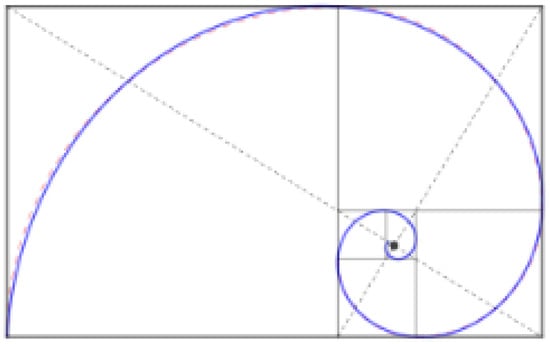

This self-similarity of rectangles naturally leads to the notion of a logarithmic spiral. The logarithmic spiral (“spira mirabilis”, Latin for “miraculous spiral”) is a classical model for natural patterns and has been widely studied since the 17th century [72] and is used in the study of biological structures and artistic design.

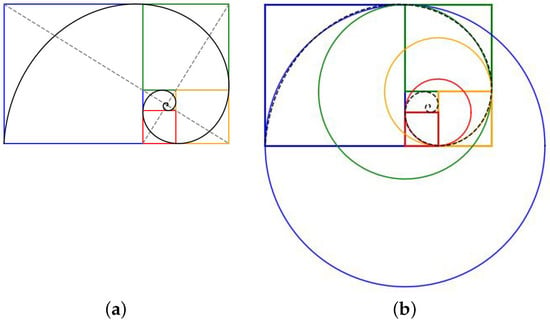

For example, if one takes rectangles with a 2:1 ratio of width to length and cuts out the largest square, what is left over is another smaller rectangle. Notice that this leftover rectangle has the same 2:1 proportion as the original. That means one repeats the same process over and over again. Each time, one removes a square, leaving a smaller, similar rectangle. Now, if one draws a smooth quarter-circle inside each square, the arcs link together seamlessly. As one keeps repeating the above procedure, the arcs “spiral” inward. The resulting shape is a logarithmic spiral as shown in Figure 9. For more discussion, see [73,74,75].

Figure 9.

Construction of logarithmic spiral from similar rectangles. The spiral is based on a series of self-similar rectangles, each having the same ratio of the longer side to the shorter side. For example, for the golden ratio logarithmic spiral, this ratio is .

Hambidge and his followers, such as Caskey, argue that most vases following the principle of dynamic symmetry can be analyzed by enclosing each one in a rectangle. This rectangle can be composed of several squares and similar smaller rectangles, allowing geometric proportions to explain the shape of the vase. The basic rectangles are the so-called root rectangles described above.

By using diagonals of squares, reciprocal rectangles, and overlaying or subdividing squares on rectangles, these basic forms are generated [76,77,78]. By attaching a square to one side of a rectangle and using it to determine new boundaries or divisions, new ratios can be produced. By continually applying squares, reciprocals, and diagonals, one produces a series of self-similar rectangles and squares in a logarithmic spiral to infinity, which Hambidge called the “whirling square rectangle.” Greek vases can be placed within these rectangles. Sometimes the entire vase, sometimes only the body of the vase; and the ratios of details often correspond to the ratios produced by applying squares, reciprocals, and diagonals to the rectangle. The ratios used in this paper are based on the method of Caskey [68].

One of the most commonly used is the golden ratio or its reciprocal . These ratios are common across all types of vases. Consider the following four “golden-ratio” examples from Caskey [68]:

- Amphora #18, page 54, “Gigantomachy”: cm (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153411—last accessed on 15, October, 2025)

- Kalpis vase #69, page 115, “Dionysos, Ariadne, Eros, Hermes, a nymph and a seilen”, height cm (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153629 —last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Krater vase #83, page 130, “Bearded man, woman with flutes and youth” height cm. (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/154185—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Oinochoe vase #86, page 134, “Butcher Cutting Meat.”, height cm. (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153541—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

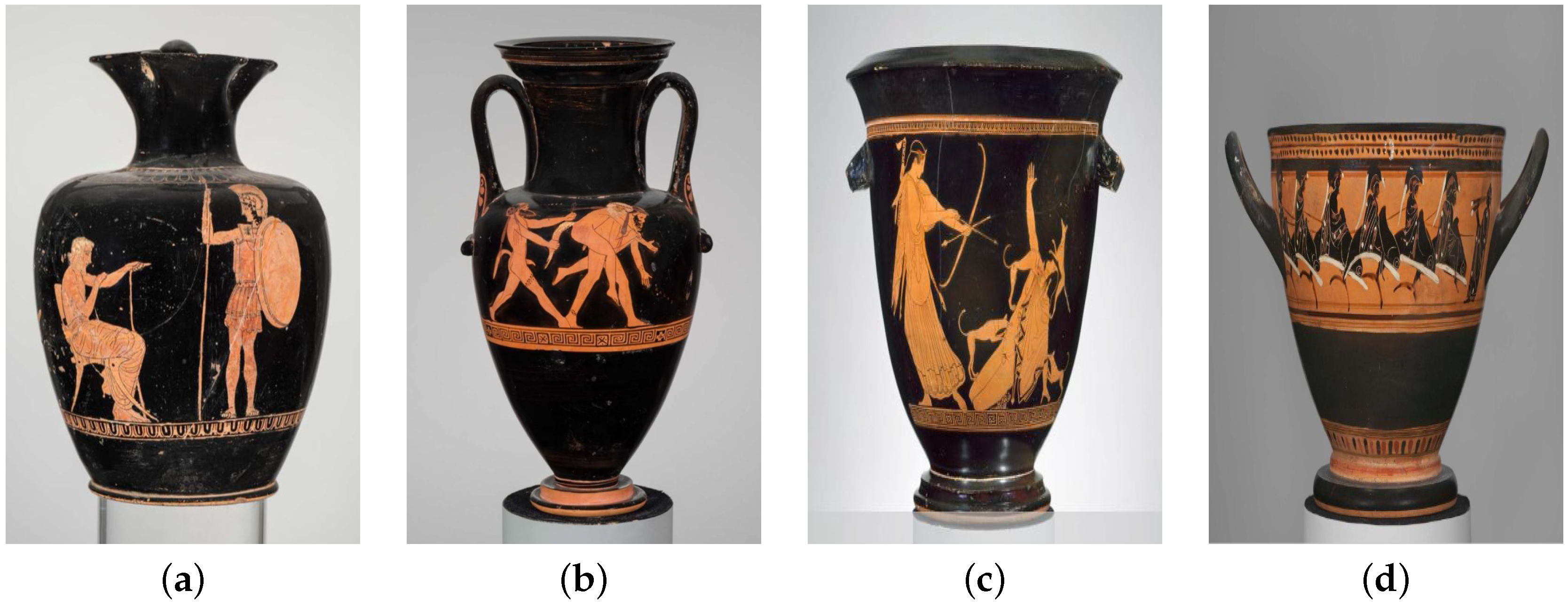

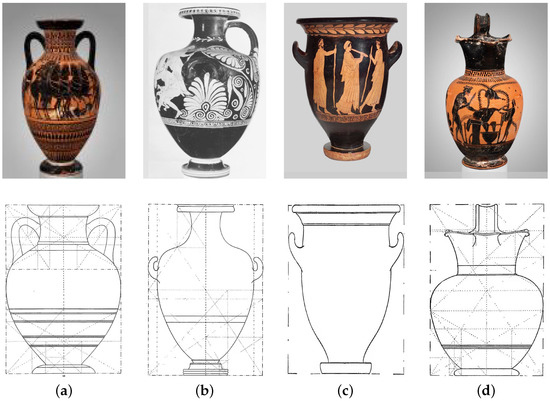

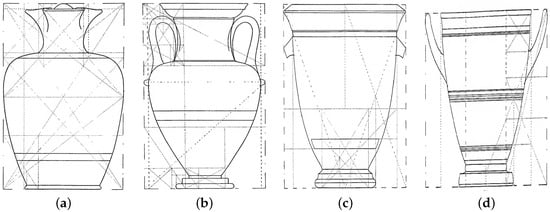

These four vases and the corresponding division into self-similar rectangles and squares are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Examples of vases with golden ratio proportions. Dynamic symmetry claims to have rediscovered a hitherto lost set of geometric principles underlying Greek art based on a number of specific proportions, many of them related to the golden ratio shown above. Application of these proportions to the form of Greek vases gives them the aesthetic quality that Hambidge termed “Dynamic Symmetry [46]. (a) Amphora (#18); (b) kalpis (#69); (c) krater (#83); (d) oinochoe (#86).

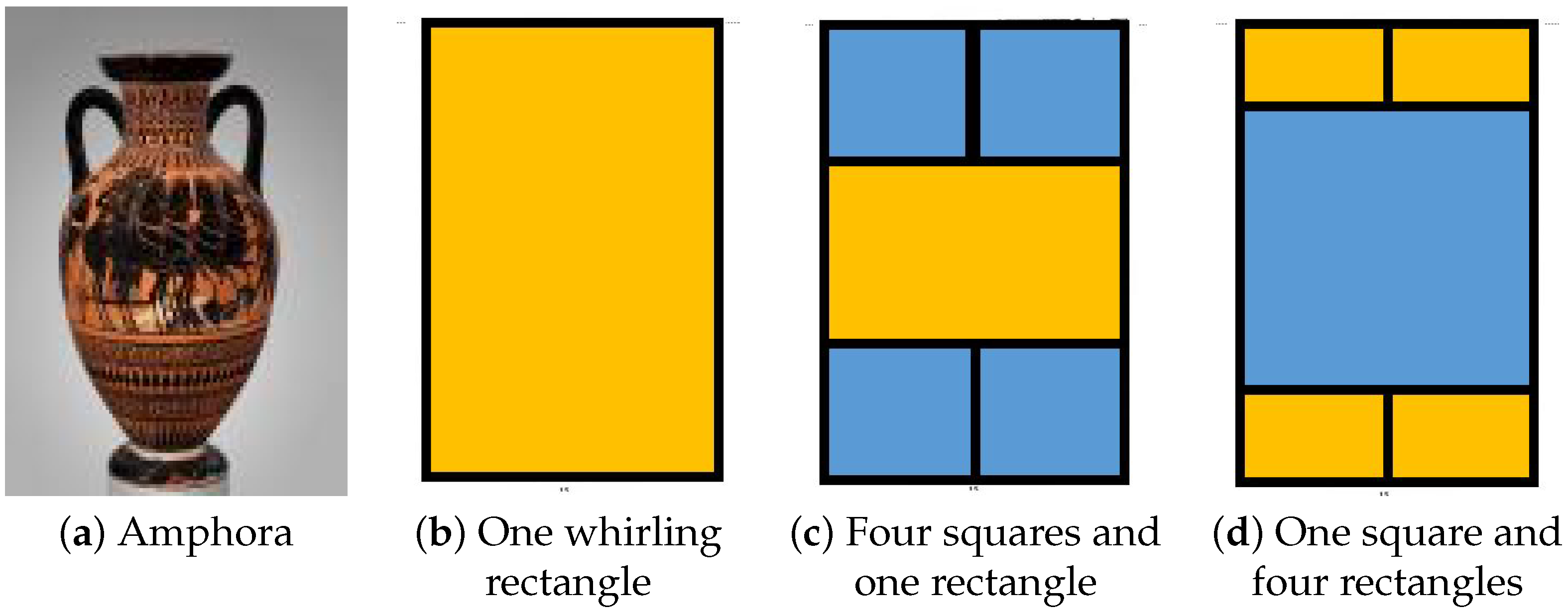

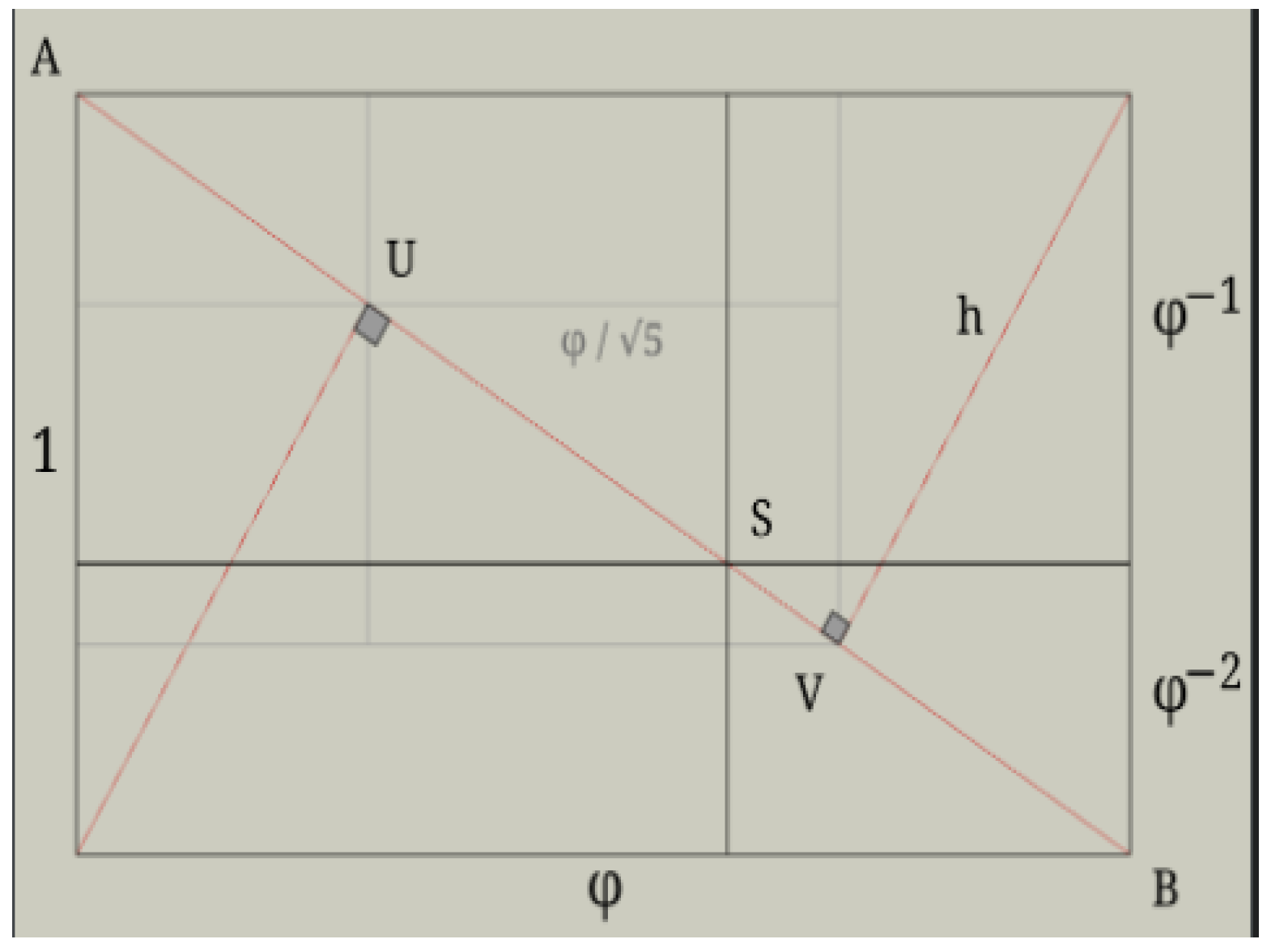

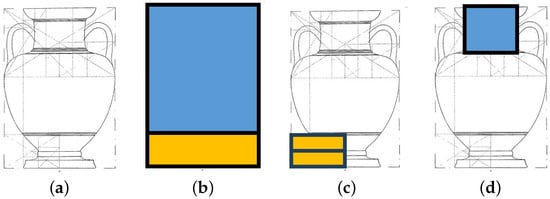

For the golden ratio, these vases can be inscribed into squares and rectangles with the same golden ratio or its reciprocal (the so-called “whirling” rectangles). This is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Illustration of “whirling” (golden ratio) rectangles. In part (a), one considers the amphora vase (#18). The ratio of its height to width is the golden ratio , and it is enclosed in a “whirling” rectangle as shown in (b). Up to a multiplicative constant, one can take the height of this rectangle as and its width . The following two subdivisions can be considered: In (c), four unit squares are placed in the corners. This leaves the rectangle with height and length 2. The ratio of its longer to shorter side is 2:, resulting in another “whirling” (golden ratio rectangle) in the middle. By contrast, in (d), four “whirling” :1 rectangles are placed in the corners. This leaves the central rectangle with (horizontal) length 2 and height , resulting in a square.

One can recursively continue dividing the obtained “whirling” rectangles into smaller “whirling” rectangles and obtain further decompositions. Note that the example above shows that such decompositions are not unique for the same ratio of the vase’s height to its width.

Based on this similarity between the construction of logarithmic spirals via self-similar rectangles and the self-similarity of Greek vase parts, a conjecture is proposed that Greek vase contours (between the foot and the shoulder) can be described by logarithmic spirals. Using mathematical equations, a simple but effective method is introduced for calculating the volume of Greek vases by using their ratios with certain parameters in a formula based on Caskey’s studies and measurements. In addition, the arc length of Greek vases will be explored and calculated with a specific formula. This paper provides a mathematical approach to understanding the geometric features of Greek vases.

4. An Alternative Conjecture on Logarithmic Spiral

In the introduction to his book, The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry [58], Hambidge writes: “…Curiously, there were but two peoples who conducted dynamic symmetry, the Egyptians and the Greeks. It was developed in the former very early as an empiric or rule-of-thumb method of surveying. Possibly the date is as early as the first or second dynasty. Later it was taken over as a means of plan-making in architecture and design in general…. The Greeks obtained knowledge of dynamic symmetry from the Egyptians some time during the sixth century B.C. It supplanted, probably rapidly, a sophisticated type of static symmetry then in general use.”

Appendix A describes a possible sequence of steps that Greek artisans would follow to create vases with logarithmic spiral contours. Figure A2 in Appendix A describes the model for pottery construction that uses templates and pins. However, it is questionable that the pin positions of the template and other measurements can be determined with sufficient accuracy to construct vases. Therefore, a fundamental question arises: did pottery design intentionally follow the proposed mathematical models (as advocated by Hambidge and other proponents of dynamic symmetry), or did other factors—such as the pursuit of aesthetically pleasing forms—naturally lead to self-similarity in vase design?

4.1. Intentionality Versus Emergent Form

This question touches on the broader debate about intentionality in ancient design practices [79,80]. There are compelling arguments for both interpretations.

- The Intentionalist View.

Hambidge and his followers [46] suggest that Greek artisans deliberately employed proportional systems inherited from Egyptian geometry and refined through Greek mathematical advances. Evidence supporting this includes the following:

- The consistent appearance of specific ratios (, , , and ) across different vase types and time periods;

- The existence of detailed proportional systems in contemporary Greek architecture and sculpture, as documented by Vitruvius and in Polykleitos’s Canon [81]; and

- Literary evidence that Greek craftsmen valued mathematical harmony and proportion [79].

- The Emergent-Form Hypothesis.

An alternative view proposes that the mathematical proportions observed in Greek vases arose not from conscious mathematical planning but from the interplay of functional constraints, aesthetic preferences, and the biomechanics of pottery production. Several factors support this interpretation:

- Wheel-throwing mechanics naturally produce logarithmic curves. In pottery making, a potter controls wall thickness and shapes the vessel by applying pressure with their hands or tools while the clay rotates on the wheel [82,83]. For smaller-diameter sections (such as the neck or base), a potter uses more focused and precise pressure to control the reduced clay volume and maintain structural integrity. Conversely, when shaping larger-diameter sections (such as the body), the pressure is distributed over a broader surface area with less intensity.It is proposed that potters could maintain vase proportionality by keeping a constant contact angle between the shaping hand (or tool) and the local radial direction while the clay rotates, thereby producing an equiangular (logarithmic) spiral as the meridian curve. As the wheel turns uniformly and the hand advances steadily along the vertical axis, this constant-angle condition yields an exponential radius–height relationship; revolving that meridian about the vertical axis generates the vase surface. The resulting logarithmic spiral features smooth, monotone curvature—well-suited to vessel aesthetics—and provides controllable tactile pressure cues. Narrower sections require more focused pressure, while broader sections distribute pressure more widely, all while maintaining the constant-angle guidance and reproducing consistent proportions.

- Functional requirements constrain proportions. Vessels must be stable (limiting base narrowness), easy to handle (affecting neck and handle positioning), and structurally sound during firing (constraining wall thickness and form) [51]. These practical constraints may naturally select for proportions that approximate mathematical ratios.

- Aesthetic intuition guides unconscious proportional choices. Modern psychological studies demonstrate that humans possess innate preferences for certain proportions, including ratios approximating the golden mean, independent of cultural training [84]. Skilled potters, through years of practice and visual training, would develop intuitive judgments about pleasing forms that coincidentally align with mathematical ideals [85].

4.2. A Synthesis

It is proposed that the truth likely lies in a synthesis of both views. Greek potters probably possessed practical knowledge of proportional relationships—expressed geometrically through squares, diagonals, and compass constructions rather than numerical calculations—while simultaneously developing aesthetic judgment through apprenticeship and practice. The mathematical models identified in this paper may represent post hoc rationalization of design principles that potters understood more intuitively. Nonetheless, the remarkable consistency of these proportions across the Greek world suggests some degree of shared knowledge or teaching tradition, even if not formalized as explicit mathematical doctrine [86].

This interpretative ambiguity does not diminish the value of mathematical analysis. Whether intentional or emergent, the logarithmic spiral model successfully describes vase forms and enables volume calculation, fulfilling the practical aims of this study. The question of intentionality remains an important avenue for future research combining archaeological, experimental, and cognitive approaches [87].

5. Self-Similar Rectangles and Greek Vases

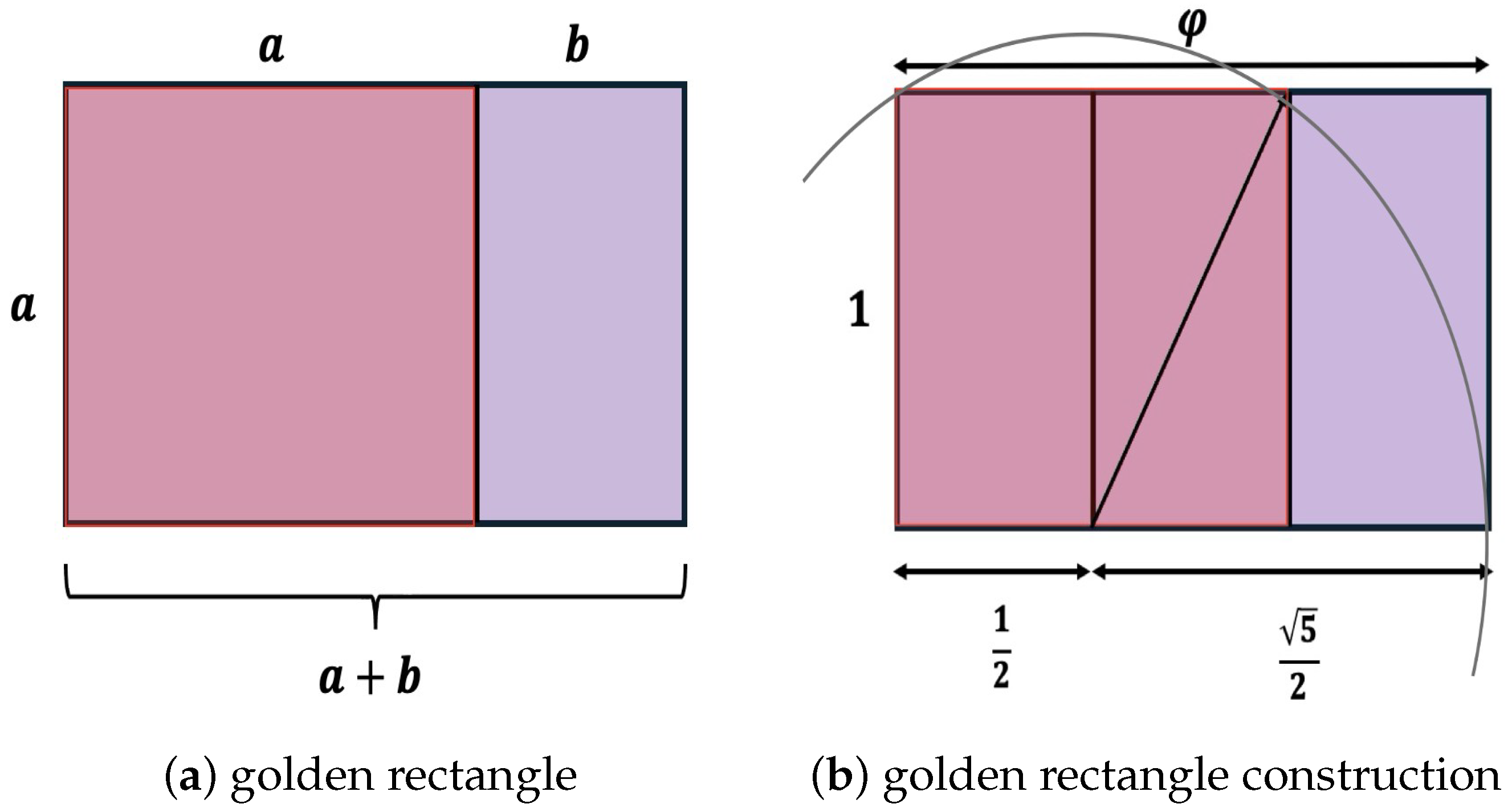

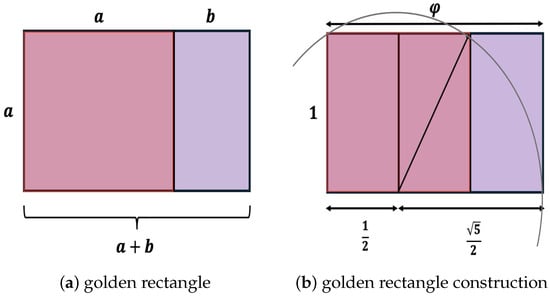

Recall that a and b are in the golden ratio k if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities (assume ). In other words,

and this gives the golden ratio . This is illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Golden rectangle and golden ratio. A golden rectangle, shown in (a), is defined as a rectangle that can be divided into a square and a rectangle similar to the original one. The side lengths of a golden rectangle are in golden ratio . In (b), the diagonal dividing one-half of the square is equal to the radius of the circle that defines the corner of the golden rectangle. This allows the construction of golden rectangles with only a compass and a straightedge [70].

This can be generalized, and other self-similar rectangles can be considered that satisfy a more general relationship:

Some special cases for c can be considered:

Caskey took many measurements, and for a vase like in Table 3, he has many different ratios with . He struggled to describe the correct self-similarity (fractal) metric since math tools were not available to him. One could make an argument that, in fact, there are only , , and vases and no other types.

One should check the following hypothesis. Assume the height a is larger than the width. Find c from Equation (6) and use this to find the index for the logarithmic curve.

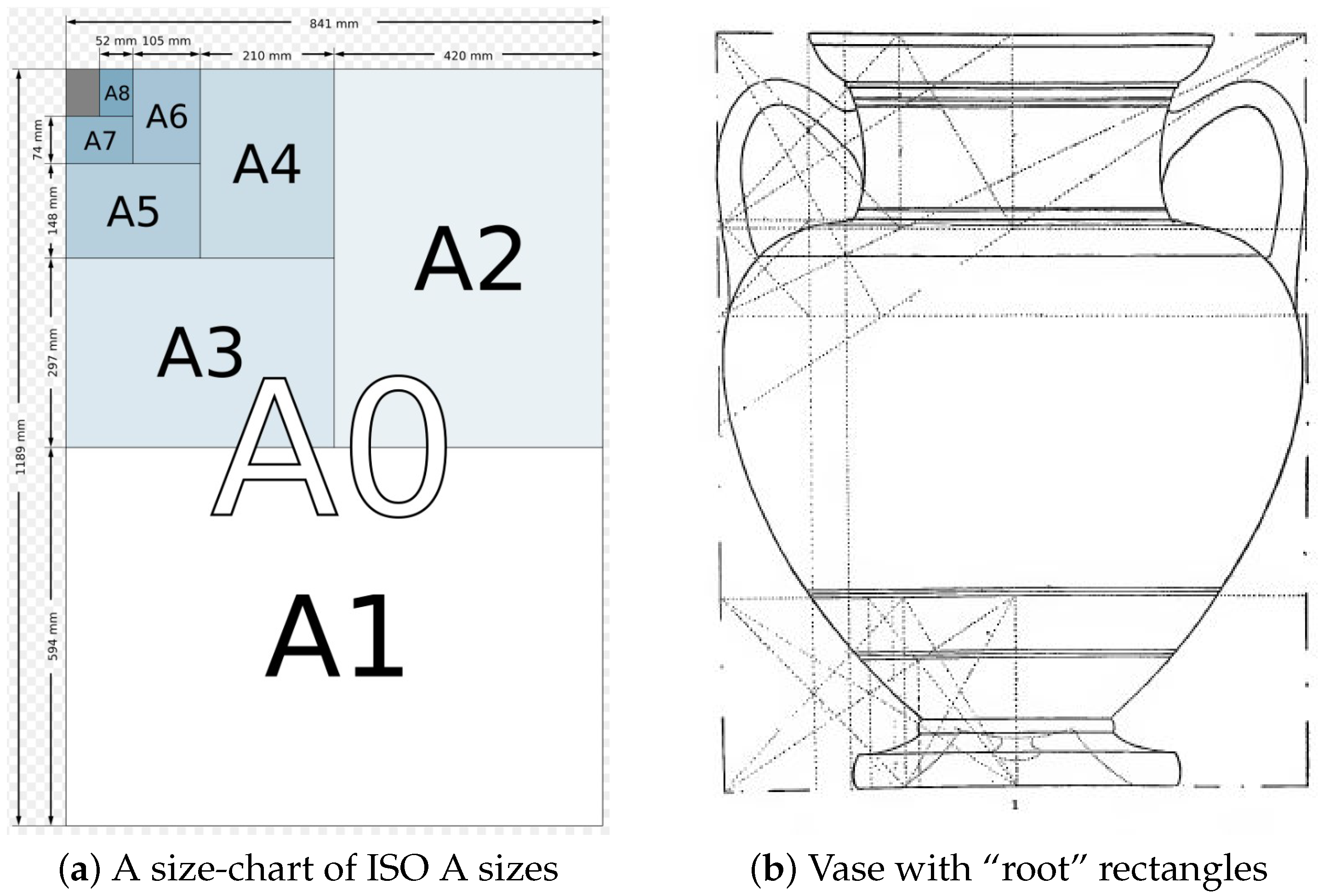

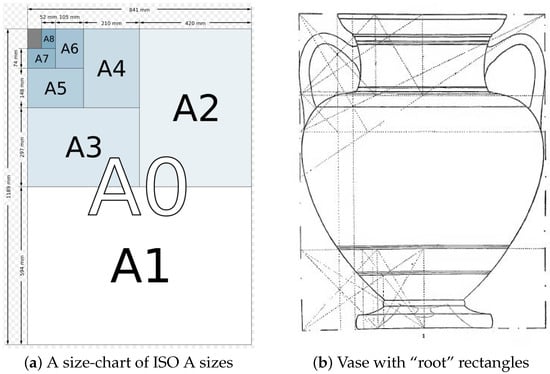

The process of constructing self-similar rectangles is simple: designate the longer side as having unit length. The shorter side is . If n such rectangles are taken and joined along their long side, then a new rectangle is obtained with shorter side 1 and longer side in the same ratio as the original rectangle. For a simple example, consider the A4 ISO 216 standard [88] ) paper sheets shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Illustration of self-similar rectangles in ISO A-sizes and in Greek vases. Consider a standard ( in.) A4 (ISO 216 standard) paper sheet as shown on the left in (a). This has a :1 aspect ratio of sides. By joining two A4 sheets together along their longer edges, an A3 sheet ( in) with the same aspect ratio ::1 is obtained. On the right side in (b), a similar decomposition in terms of similar rectangles is shown for covering a vase layout. Such decompositions in terms of self-similar rectangles are the central idea of dynamic symmetry and are described in detail for many vases by Caskey [68].

A similar observation can be made by examining the Greek vase construction. Caskey refers to these as “root-rectangles” and presents a simple method of constructing them using a square and a compass. There are other methods of constructing these that were known in ancient Greece, such as the spiral of Theodorus. These are illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

The basic principle advocated by dynamic geometry when applied to shapes of Greek vases is what today one calls self-similarity. Each vase is constructed in terms of squares and self-similar rectangles. The self-similar rectangles use primarily , , and rectangles, and the rectangles built around the golden ratio (or its inverse). These latter rectangles are called “whirling” rectangles [64].

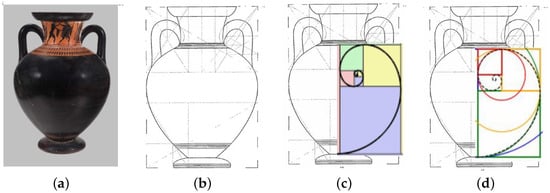

As an example, consider the Nolan Amphora showing Athena and Hermes. This amphora is in the art collection of Yale University and is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Nolan Amphora Athena and Hermes (500–460 B.C.E.).

The details are described at https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/1726 (last accessed on 15 October 2025). This amphora has dimensions cm). This gives a ratio of . This number is approximately and can be constructed in terms of squares (blue color) and rectangles (red color). This is shown in Figure 15. Its dimensions and layout are similar to the Nolan vase described [68].

Figure 15.

Composition of squares (blue) and self-similar root-two rectangles (blue) for the “Athena and Hermes” amphora. (a) Amphora; (b) layout; (c) initial; (d) final.

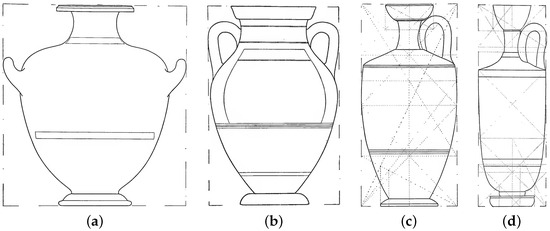

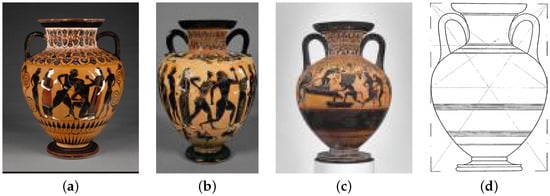

As mentioned before, in dynamic symmetry, the most common ratios were , , and and their variants, especially the golden ratio (“whirling” rectangle), are closely related to (root-five rectangle). Consider the following four examples with these ratios shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Profiles of common ratio vases with dynamic symmetry. (a) oinoche; (b) amphora; (c) krater; (d) skyphos.

These four vases in Figure 16 are:

- Oinoche #90, page 138: “Old Man and Warrior Departing”, height cm,(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153820—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Amphora #29, page 65: Satyr carrying a silenos on his back, height , diameter cm,(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153599—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Bell krater vase #79, page 126: “Artenis Killing Aktaeon”, height cm,(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153654—last accessed on 15 October 2025 ).

- Skyphos #104, page 149: “Chorus Scenes”, height cm, ratio(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153547—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

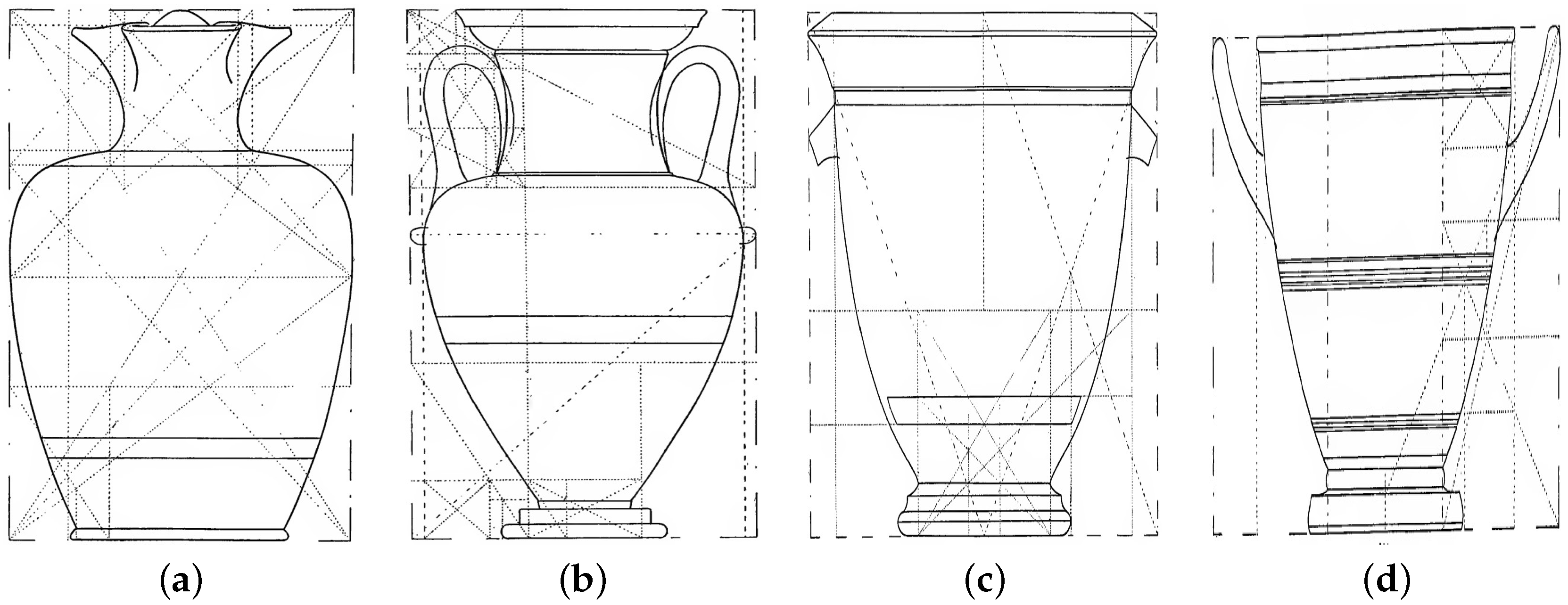

Their layouts are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Examples of common ratio vases with dynamic symmetry. (a) oinoche; (b) amphora; (c) krater; (d) skyphos.

The above vases are examples of what Hambidge calls “Dynamic Symmetry”. In dynamic symmetry, the basic building blocks are squares and rectangles of certain proportions, namely root-two, root-three, and the root-five rectangles, and the most important of all, the so-called “whirling squares” (golden ratio rectangles). According to Hambidge [64], such dynamic rectangles represent the idea of growth, harmony, motion, and development.

By contrast, the static symmetry, according to Hambidge, is radial: rectangles in static symmetry have proportions based on squares and equilateral triangles, as well as their corresponding inscribed and escribed circles. Therefore, these circles have radii in proportion 1:2:3:4:…. To quote Hambidge (page 141 in [46]): “For example, a Greek design whose greatest width is some even multiple of its greatest length, as 1:2, 1:, 1:1, 1:, 1: etc. is almost sure to have its details expressible in logical subdivisions of the containing shape. Any of the static examples of Greek pottery shapes in this book exemplifies the idea.”

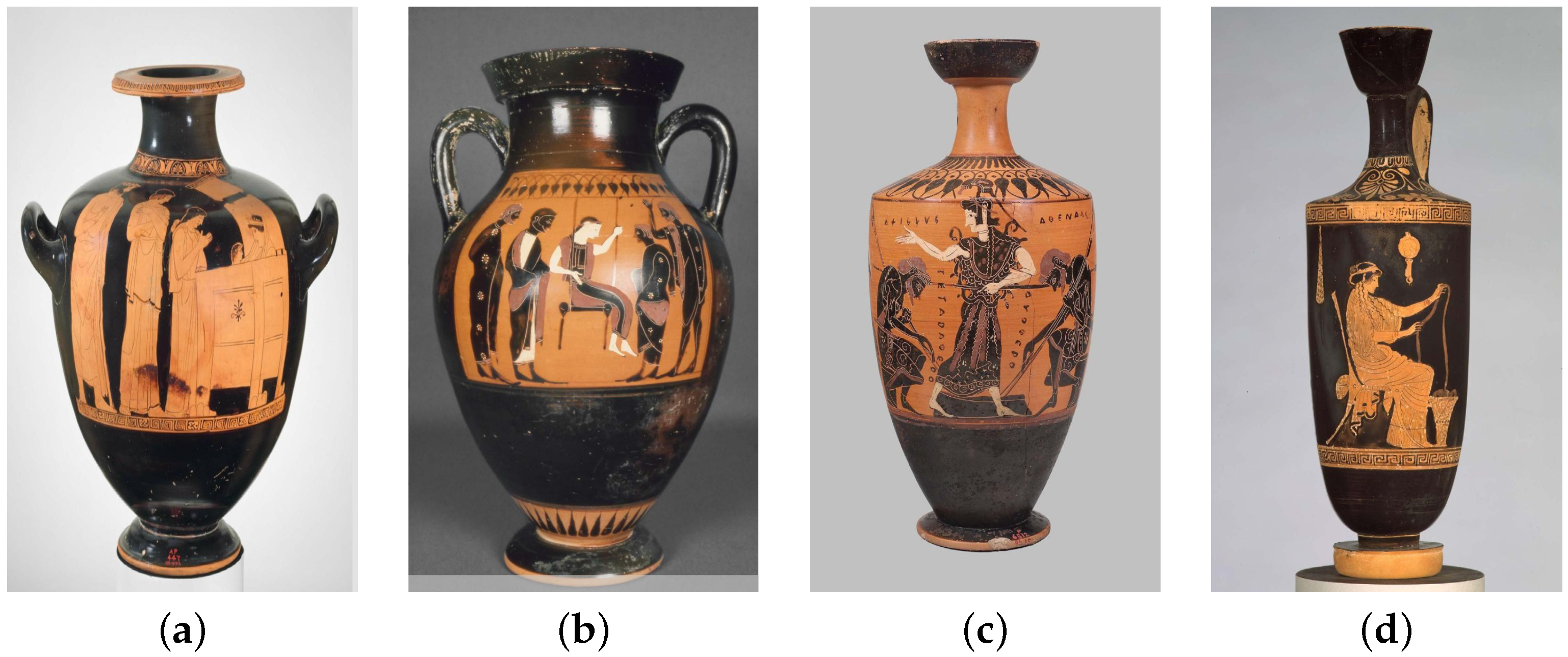

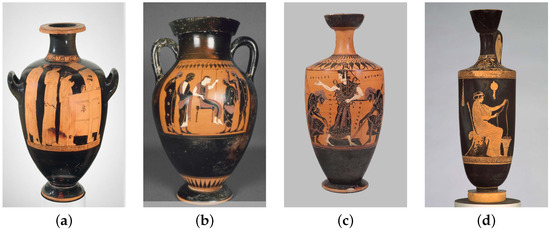

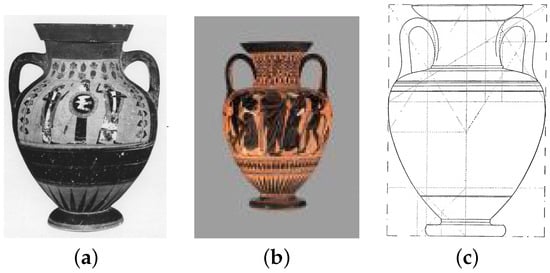

Static symmetry examples with simple fractions and integer values for the ratios are, therefore, possible but are quite rare (with just a few in Caskey’s dataset). The four examples of such ratios are illustrated in Figure 18:

Figure 18.

Examples of ”Static Symmetry“ vases. (a) 1:1 hydria; (b) 3:2 amphora; (c) 2:1 lekythos; (d) 3:1 lekythos.

These four vases are as follows:

- Hydria #65, page 111: “Danae with Perseus seated in Chest”, height cm, width cm with (approximate) ratio k = 1:1(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153632—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Amphora vase #23, page 59: “Girl Seated in a Swing”, cm, k = 3:2(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153394—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lekythos #164, page 210 “Achilles, Ajax and Athena”, height cm, diameter (width) , (approximate) ratio k = 2:1(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153522—last accessed 15 October 2025).

- Lekythos #171, page 216 “Woman Working Wool”, height cm, diameter cm, (approximate) ratio k = 3:1(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153786—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

The layout of these four vases with static symmetry is shown in Figure 19:

Figure 19.

Layouts for “Static Symmetry” vases. (a) Hydria; (b) amphora; (c) lekythos; (d) lekythos.

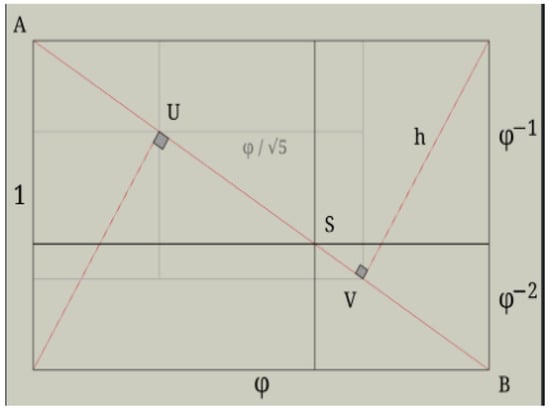

For any vase, the determination of the index k is carried out by examining the ratio of the sides of the enclosing rectangle, and then looking for squares and self-similar rectangles by examining subsequent ratios and diagonals. For the golden ratio, these have geometric relationships, as shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Illustration of powers of . Consider a rectangle on the left with sides 1 and length . Its diagonal has length . The two triangles on the diagonal have heights . Consider the point S at the intersection of the diagonal and the (internal) edge of a square. If one draws a horizontal line through this point S, then the original rectangle and the two scaled rectangles will have edges with ::1 ratios.

The curve connecting the centers of these rectangles is a “golden spiral” [74,75]. The golden ratio has many interesting relationships:

From these, one can immediately obtain the Fibonacci sequence.

The Fibonacci sequence is a simple recursive relationship connecting subsequent self-similar rectangles. Note that one can write .

It is our hypothesis that the outer contours of Greek vases are described by such logarithmic spirals, reflecting the self-similarity of the underlying covering by self-similar rectangles. The logarithmic spiral has a long history in mathematics and has been used to describe many forms in nature, science, and engineering [69,70,71,72,89,90,91]. For a detailed discussion, see [92].

Finally, note that dynamic symmetry was not without its critics [61,93]. One of the main criticisms is the ad hoc rules for identifying self-similar rectangles and their ratios. Another is the argument that there is no unique way to represent areas in terms of these rectangles. As an example, consider again the Athena and Hermes amphora in Figure 14. Figure 15 shows that this amphora can be represented in terms of five squares and five root-two self-similar rectangles. An alternative way in terms of self-similar root-two and silver-ratio rectangles are shown in Figure 21, where the same vase is represented in terms of two squares, six silver ratios, and two root-two self-similar rectangles.

Figure 21.

Composition of squares (blue), root-two (red), and silver ratio rectangles (green) for the “Athena and Hermes” amphora. This figure illustrates multiple ways to cover the vase layout shown in (b). In (c), the covering is accomplished with squares and root-two rectangles. By contrast, in (d), the covering is accomplished by squares, root-two and silver ratio rectangles. (a) Amphora; (b) layout; (c) root-two only; (d) root-two and silver ratio.

Note that in both representations (Figure 21c,d) one has the “” term. The argument advocated in this paper is the following: Hambidge, Caskey, and others have provided very strong evidence of self-similarity in vases. The type of rectangle is computed simply by the ratio of the height of a vase to its width, giving the index of the logarithmic spiral that describes the contour of the vase (from lip to shoulder).

To summarize: Mathematically, the dynamic symmetry is based on the following three equations:

The first equation in Equation (10) defines the “Whirling-Square” (golden ratio) rectangle. The second equation in Equation (10) defines root rectangles. Finally, the last equation in Equation (10) shows the decomposition of the root-5 rectangle into a square and two “whirling-square” rectangles. In practice, only the following five types of rectangles are used (shown in Figure 16 and Figure 18):

- Square 1:1 and static symmetry ratios;

- Root-two rectangle: :1;

- Root-three rectangle: :1;

- Root-five rectangle: :1;

- Whirling square rectangle: :1.

6. Caskey’s Vase Dataset

Based on Hambidge’s findings about the relationship between vases and rectangles, Caskey measured many Greek vases and suggested that the vases and their components could be described by rectangles with a consistent ratio, representing the proportion between sides. Although there were more than 300 vases described in Caskey’s book, only 185 vases have graphs with full or partial measurements. The full measurement data include vase heights (height with cover, height without cover, height of cover, height of neck and lip, height of shoulder), widths, and diameters (diameter of the vase, diameter of lip, diameter of bottom of body, diameter of shoulder, diameter of foot, diameter of bowl, diameter of cover), as well as the ratio of the vase and types (type of vase, general type of vase).

The dataset is used to explore the relationship between geometric ratios and the types of Greek vases, as well as to calculate the volume of the vases based on our formula. Specifically, geometric ratios demonstrate how the ancient Greeks applied the principle of mathematical harmony to achieve balance and artistry in their vase designs. This section presents a discussion of some common ratios, such as the golden ratio and , and how vase types or periods favored particular ratios according to stylistic tendencies and Greek cultural influences. The next section extends the analysis by explaining how the volume formula is derived and how to apply ratios in calculating vase volumes, thereby connecting geometric art to its practical function.

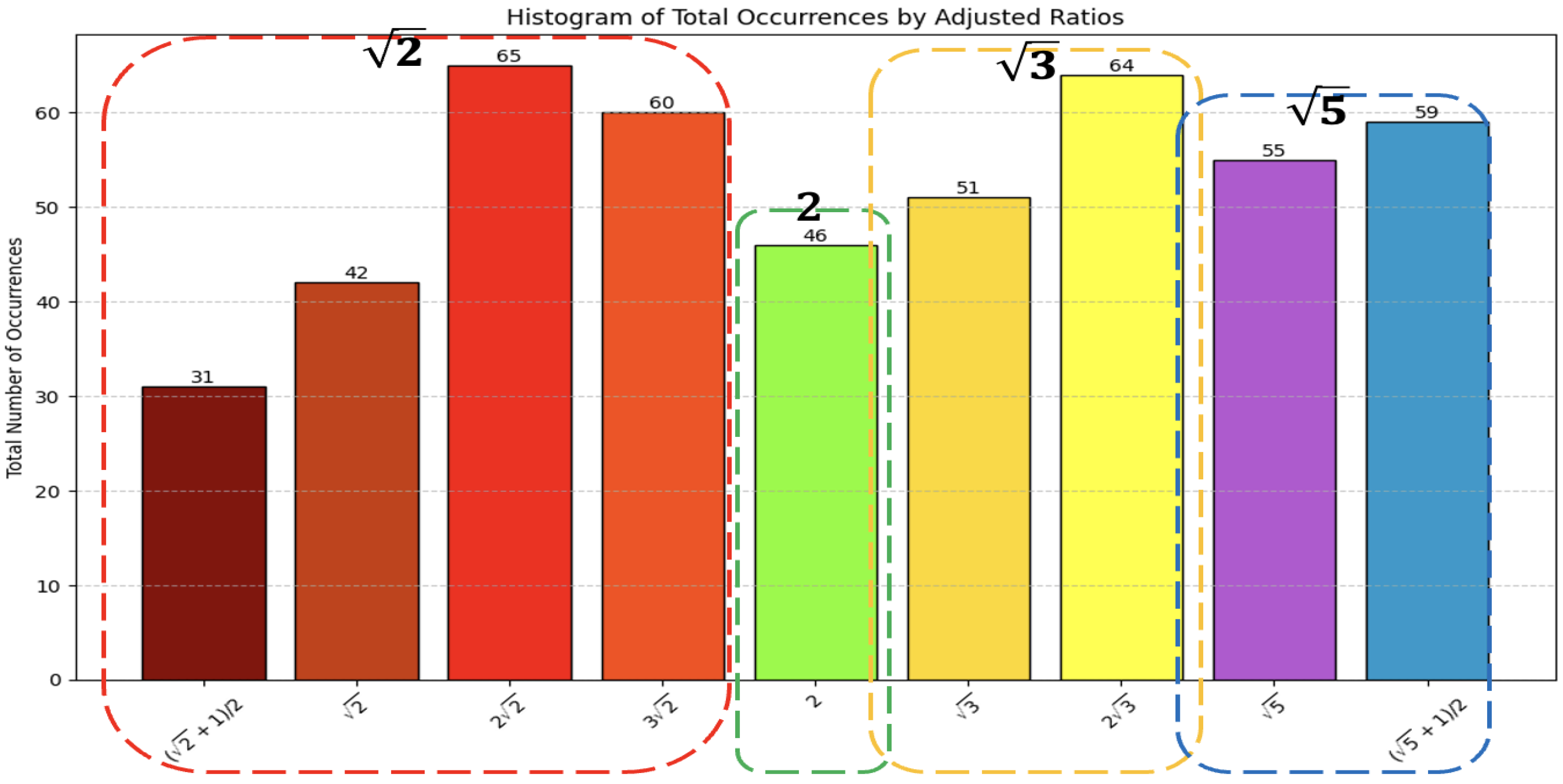

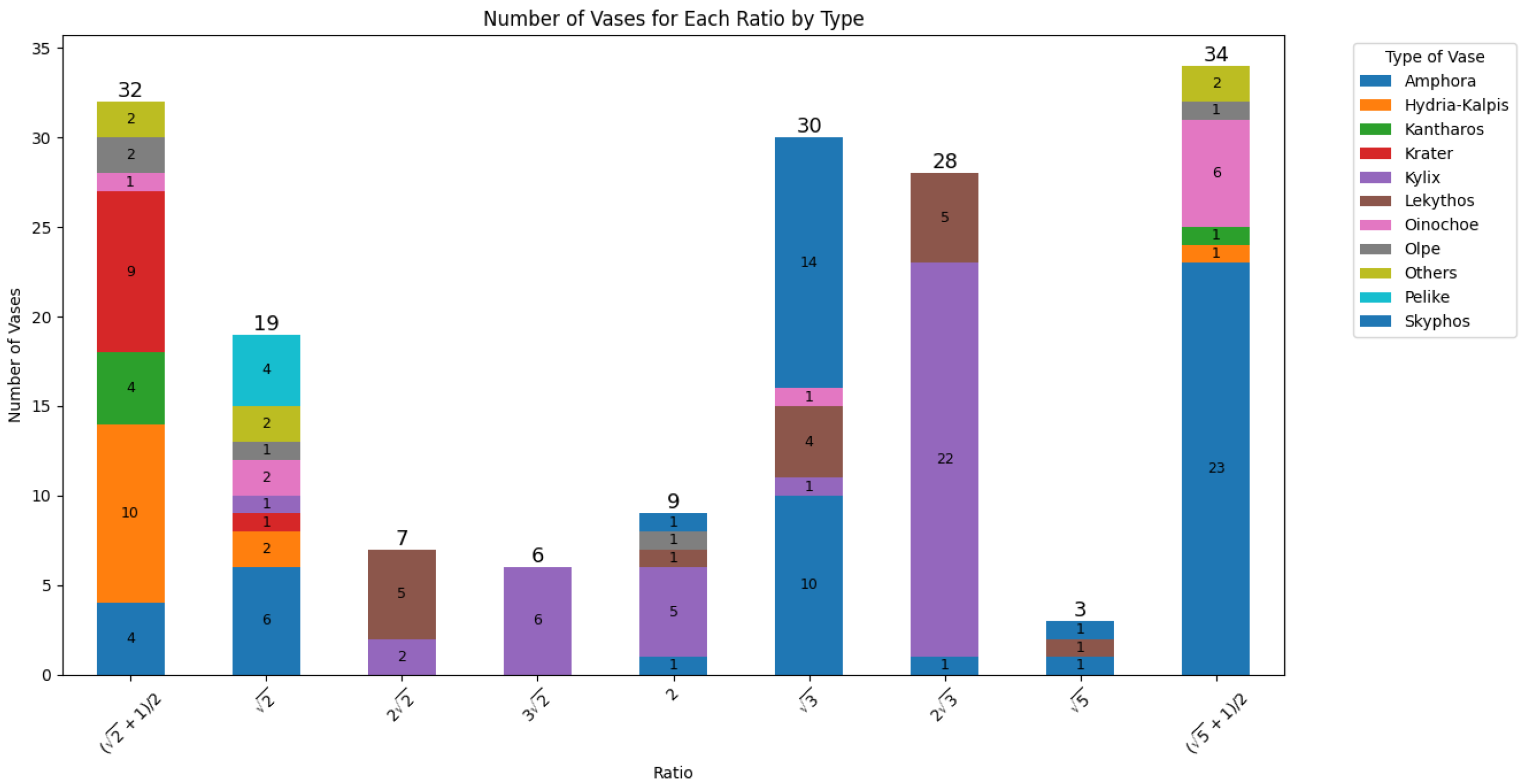

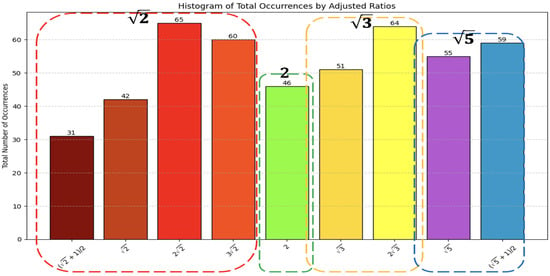

Each group has similar color bars: (red), 2 (green), (yellow), and (blue), as shown in Figure 22. Four bars are in the group, which means the most common ratios are in . Two bars have more than 60 vases: and . The group has the second most vases, and has 64 vases. For the group, the golden ratio has the most vases, which is 59, but the group also has 55 vases. The group with the fewest vases is the 2 group, which has only 46 vases. By calculation, about 42% of vases are in the group, the and groups both have around 24% of the total vases, and the 2 group has 10%.

Figure 22.

Divided occurrences of the 9 most ratios into 4 groups. Ratios related to are in red; 2 is in green; ratios related to are in yellow; ratios related to are in blue.

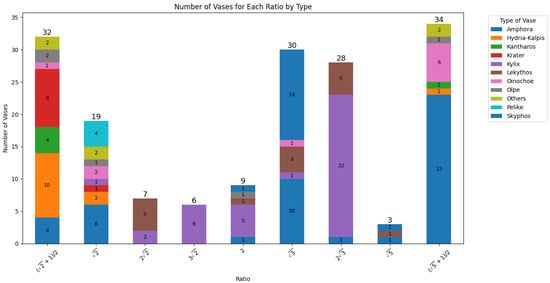

As mentioned before, 185 vases have graphs with full or partial measurements in Caskey’s books. From these 185 vases, 168 vases have a listed ratio with their type, and the results were presented in two graphs. One shows the number of vases for each ratio by type, and the other shows the percentage.

Let us discuss the number of vases first in Figure 23. Four ratios that have more than 28 vases: , , , and the golden ratio . The golden ratio was the most common ratio in these vases, with 34, followed by with 32 and with 30. In the golden ratio, most of the vases are amphora (23), and for , vase types are varied. Krater and hydria-kalpis are the main ones in , with 9 and 10 vases, respectively. In the group, 10 amphora and 14 skyphos are the top vase types, and for the group, kylix was the most common type with 22 out of 28 vases.

Figure 23.

Number of vases for each ratio by type. This graph describes the distribution of vase types in specific ratios. The number displayed at the top of each bar shows the total count of vases within that ratio. Each bar (each ratio) contains different vase types.

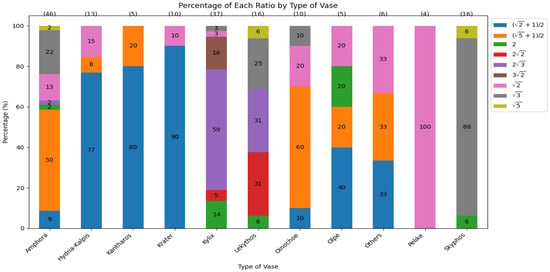

In Figure 24, the amphora type has varied ratios, but the top ratio is the golden ratio with 50%, followed by with 22%. The ratios of hydria-kalpis, kantharos, and krater are mainly , with 77%, 80%, and 90%, respectively. Kylix has almost 60% in . In Lekythos, three ratios total more than 85%: and are both 31%, and has 25%. Oinochoe is mainly the golden ratio at 60%, followed by at 20%. Olpe has 40% in , and golden ratio, 2, and are all 20%, respectively. Surprisingly, pelike vases are all ratio. Last but not least, skyphos are mainly ratio at 88%.

Figure 24.

Percentage for each ratio by type of vases. Each vase type represents 100%. Each ratio has a different percentage distribution across vase types (each bar). Ten specific vase types are listed, and all remaining types are grouped under the “Others” category.

From the 168 vases, it is interesting that the results compared to all vases’ ratios are similar. The group is still the most common ratio among all vases, followed by and groups. The 2 group has the fewest vases. The difference is that the group has more than the group, compared to all vases, where they have almost the same number. By calculation, the group accounts for 38% of total vases, the group has 35%, the group has 22%, and the 2 group has 5%.

7. Volume of Vases

7.1. Notation

Before determining the volume of the vase, it is necessary to establish a coordinate system. This can be achieved as follows:

- The y-axis is set to be along the line of radial symmetry of the vase.

- The x axis is set to be a line perpendicular to the y-axis, in the same horizontal plane as the bottom of the vase’s body.

Due to the radially symmetric nature of the vase, any line satisfying this criterion should be an appropriate selection for the x-axis. The scale is set up so that the width of the vase is 1 in the coordinate system, with both axes being scaled by the same ratio.

Now that the axes are set up, one needs to select the notation for the points that are used for measurements. The aim is to calculate the capacity of the vases. To this end, the following points are labeled:

- : Relative coordinates of the widest point of the bottom of the body.

- : Relative coordinates of the widest point of the body.

- : Relative coordinates of the widest point of the shoulder.

This is illustrated in Figure 25.

Figure 25.

Vase size components and notation. (a) Size components; (b) size notation.

While not all the necessary measurements for computing the coordinates are readily available, one can manually collect the necessary measurements for amphora vases (discussed in Section 9).

7.2. Volume by Integration of Logarithmic Spiral

7.2.1. Estimation of Parameters

Following the assumption that the surface of the vase is a logarithmic spiral, one needs to find the equation of the spiral. One must do so by using parametric equations. These equations will capture the shape of the vase surface, but due to the nature of parametric optimization, it is beneficial to add one or more constraints to these equations to prevent them from fitting the selected data points too precisely and to incorporate some physical properties of the vase surface. To that end, one can proceed as follows:

- Define the parameters of the logarithmic spiral and decide the constraints placed on these parameters, as well as their physical significance.

- Express the known measurements of the vase using the defined parameters.

- Add other constraint equations to incorporate physical properties of the vase.

- Use programmatic tools to find the optimal values for this set of equations.

Extending the same convention as defined in Section 7.1, let be the coordinates of the center of the logarithmic spiral. For a logarithmic spiral centered at , the points on the spiral with the ratio k are as follows:

Let the radial angles made by the points , , and with the center of the spiral be , , and , respectively.

Using the notation set up in the previous section, one has the following equations:

As all three points lie on the same side of the center, all angles are between and . As one is not yet certain about the direction of the spiral, i.e., the sign of k, no restrictions are placed on the signs of the angles () and the constant a, as they will absorb the negative sign of k and yield the appropriate values.

As these equations are incredibly complex to solve simultaneously, a Python (version 3.12) program is used to solve them to get the exact values of , , a, and .

To proceed, the following theorem is needed:

Theorem 1.

The angle between the line joining any point on the spiral to the center and the tangent at that point is constant and equal to .

Proof of Theorem 1.

Consider any point on the logarithmic spiral. The slope of the line joining to the center of the spiral is given by

Next, the slope m of the tangent at can be computed:

From Equations (18) and (19), one obtains that the angle between the radius and tangent at is given by

This completes the proof. □

Next, consider the point on the spiral with the largest x-coordinate. To proceed, the following theorem is needed.

Theorem 2.

The tangent at the point with the widest point of the spiral, i.e., the point with the largest x-coordinate, is vertical.

Proof of Theorem 2.

At this point, it is clear that . Now the slope at this line is given by

Thus, the slope of the tangent is not defined, and hence it is vertical. This completes the proof. □

Under the convention defined in Section 7.1, this point is . These theorems lead to the following fact.

Theorem 3.

The radial angle for is .

Proof of Theorem 3.

By definition, is the widest point on the spiral. From Theorem 2, the tangent at is vertical.

From Theorem 1, the angle between the line joining to the center and the tangent at that point is equal to . As the tangent is vertical (at the widest point of a vase), the angle between the radius at and the y-axis is . It follows that the angle between the radius and the x-axis is , which is the radial angle for by definition. □

One now has the following constraints:

These equations can be solved numerically, using Python, to find the values of , , c, , , and .

7.2.2. Computation of Volume

Once the values of the parameters are found and the equation of the logarithmic spiral is known, one can calculate the volume of each vase.

Considering a general vase with the notation used so far, one can write the volume of the vase by integrating the volumes of the infinitesimally thin disks, sliced along the x-z plane [94,95]:

In Appendix B, the following formula for the volume is proved:

It is clear that this formula is too complex to have been used by the Greeks, who relied on simple measurements. The existence of and in this equation further complicates matters, as there is no method to find their values except for numerical optimization. For these reasons, this avenue is no longer pursued.

8. Approximation by Frustums and Ellipsoids

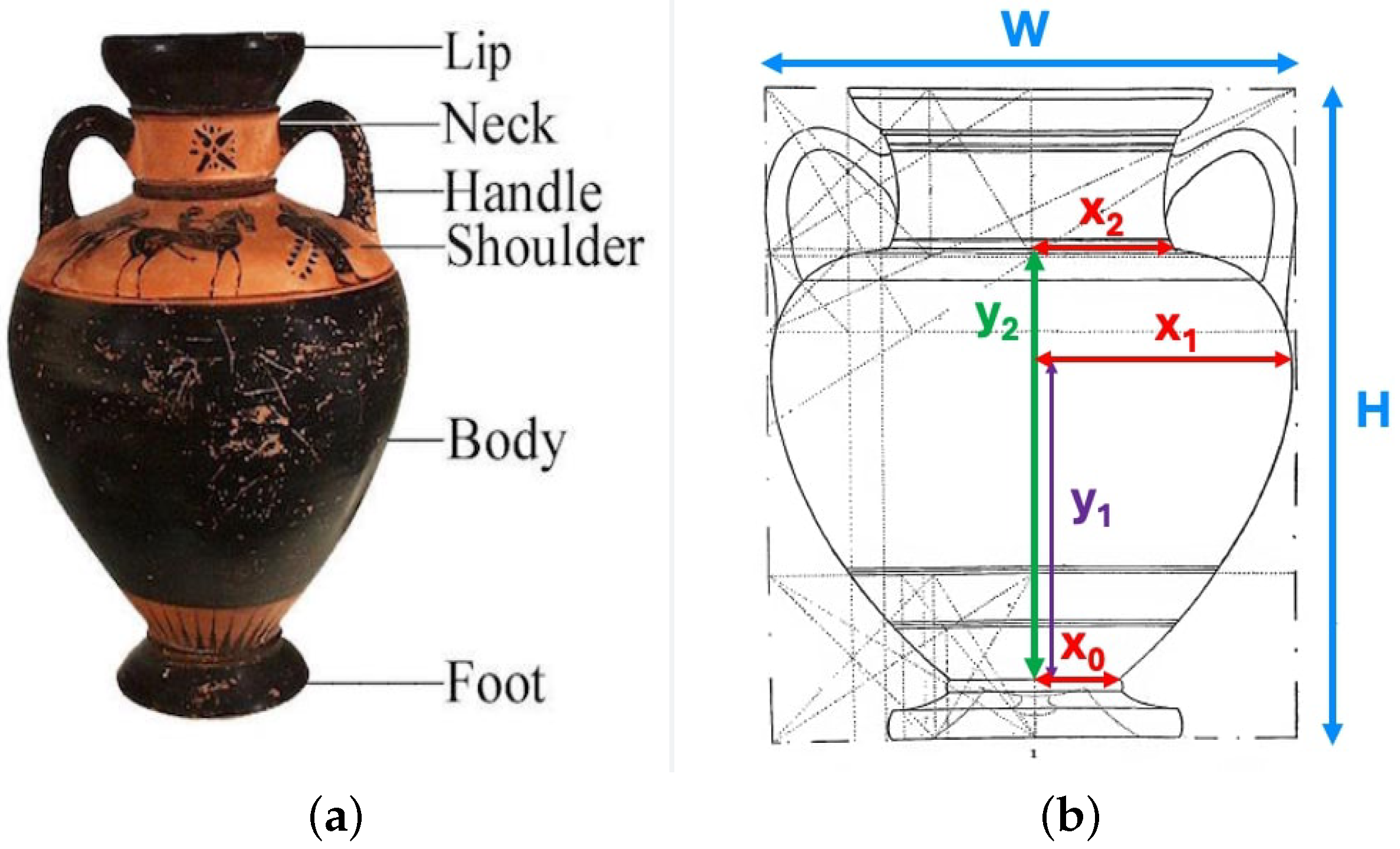

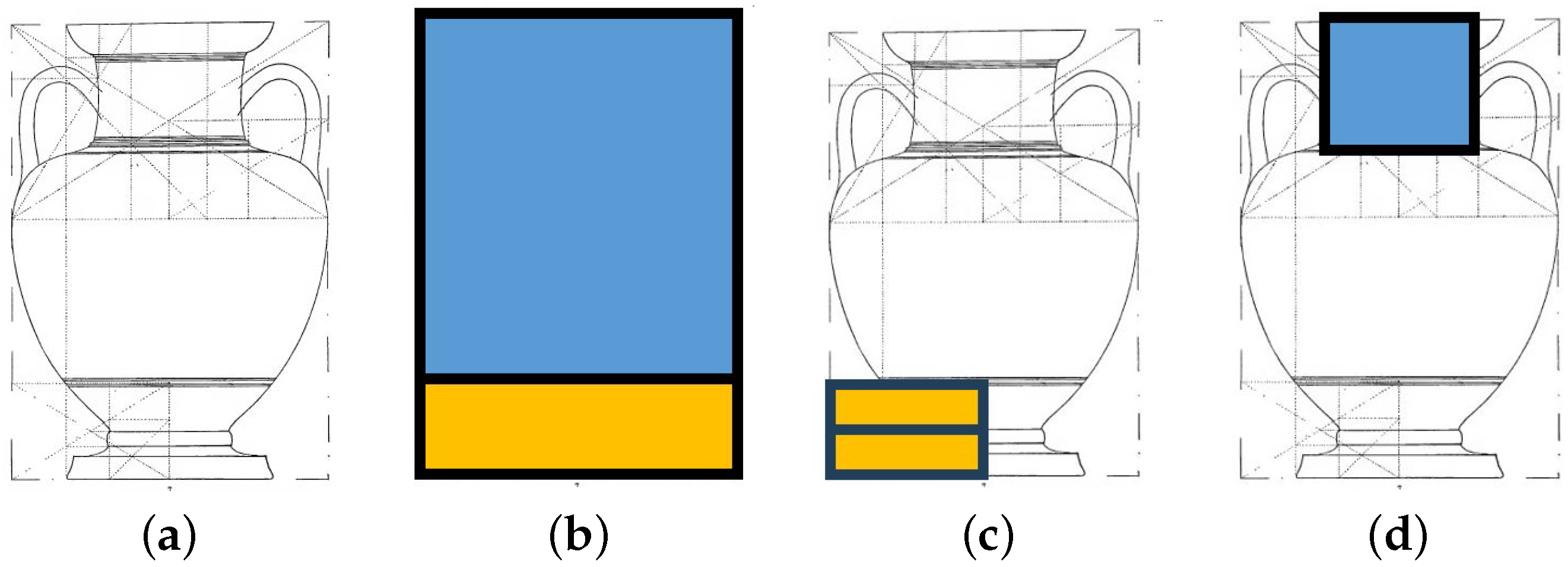

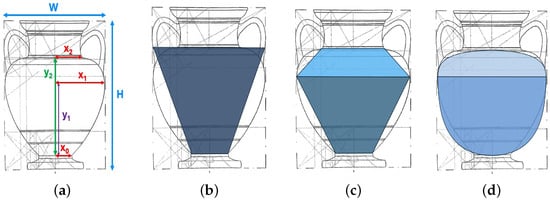

The obtained results are compared with three approximation methods illustrated in Figure 26:

Figure 26.

Approximation of the body of an amphora by one frustum, two frustums and by two semi-ellipsoids. (a) Notation; (b) 1 frustrum; (c) 2 frustrums; (d) 2 ellipsoids.

- One Frustrum: Consider a single frustrum in Figure 26b. The radii are and . The volume of this frustrum gives the following approximation to the volume of the vase:

- Two Frustrums: Consider two frustums (as in Figure 26b): A lower frustum has bottom radius and top radius . Its height is . The upper frustum has a bottom radius and top radius . Its height is . The total volume of these two frustums gives the following approximation to the vase volume:

- It is clear that considering the vase as two frustums instead of one helps capture the volume of the vase more accurately. With this intuition, the number of frustums can be increased as much as possible, and in the limit, this turns into two ellipsoids. A lower ellipsoid with radius and height . The upper ellipsoid has a radius as well and its height is . The total volume of these two ellipsoids gives the following approximation to the vase volume:

Using the approximation one can rewrite the two ellipsoid approximation as

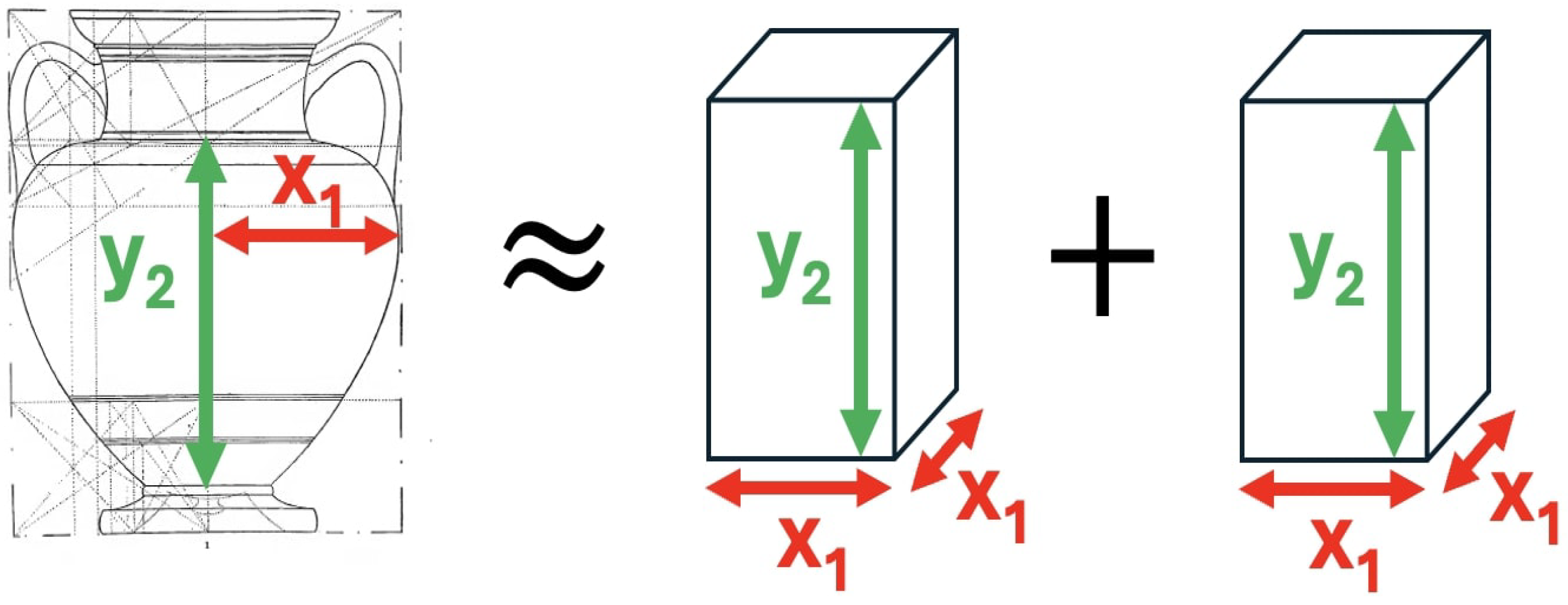

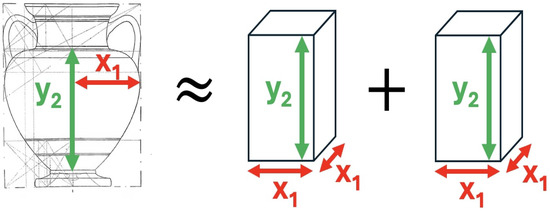

Therefore, the volume of the vase is approximately the volume of two solids, each with a square bottom of length and height . This is illustrated in Figure 27.

Figure 27.

Visual representation of Equation (33), after approximating as 3.

Since the horizontal and vertical lengths were scaled by the same factor, we can quickly move between the relative coordinates and the actual lengths of the vase. It should be noted that the following formulae use the actual length measurements and not the relative lengths used in Equations (31)–(33).

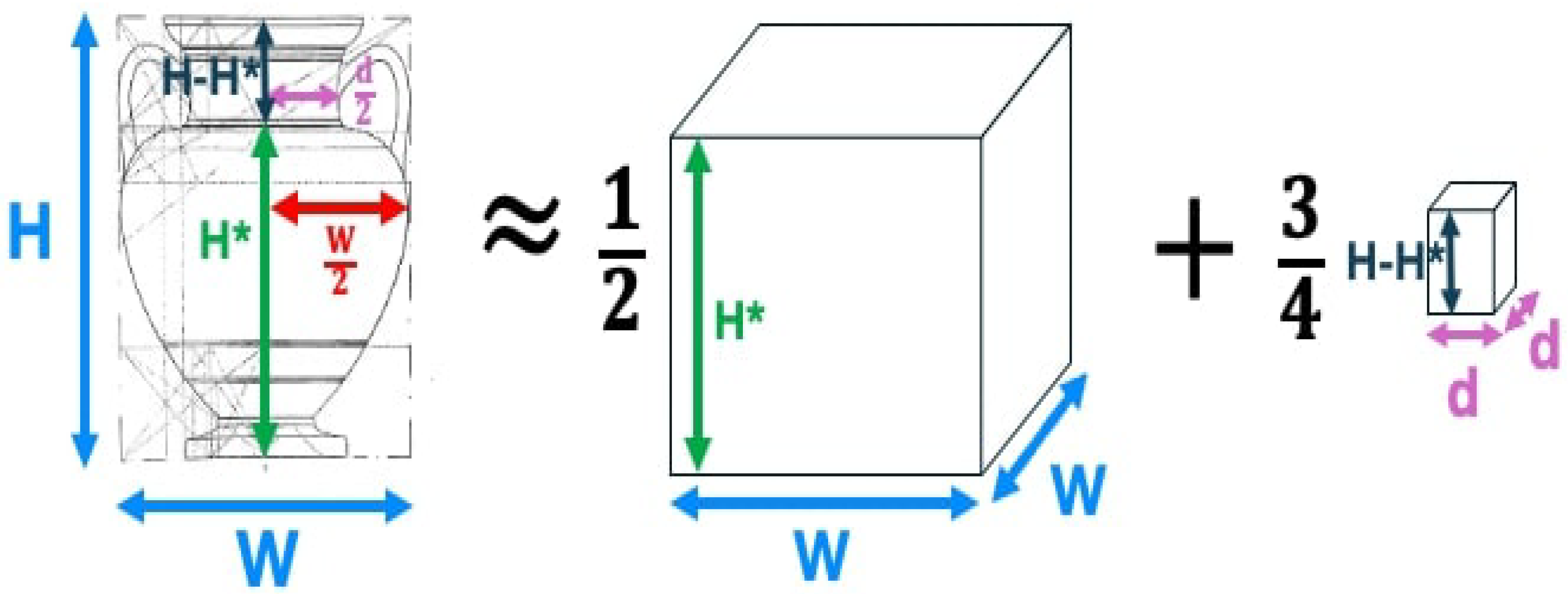

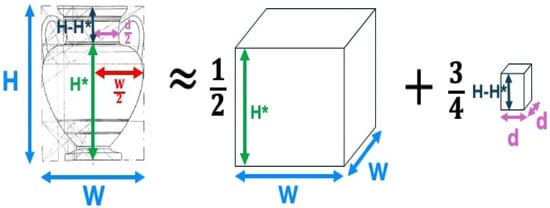

The approximation in Equation (34) can be rewritten in terms of the diameter W and the height from the foot of the vase to its as follows:

To compute the volume filled to the rim (as reported in some studies), the volume of the cylinder representing the neck must be added. If the diameter of the neck is d and the height of the neck is h, then the volume of the neck to the rim is . In this case, the volume of the vase filled to the rim is

For many of the amphorae, the foot height is a small fraction of the total height. If the foot height is ignored, then is just the height to the neck and is the height of the neck. The values for H, W, and neck diameter d are readily available in tables in [68]. If the foot height is ignored, then from Equation (36) one obtains the following approximation for the volume of the vase when filled to the rim:

This is illustrated in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

Illustration of simple volume approximation (Equation (37)).

The proposed approximation will be illustrated in later sections.

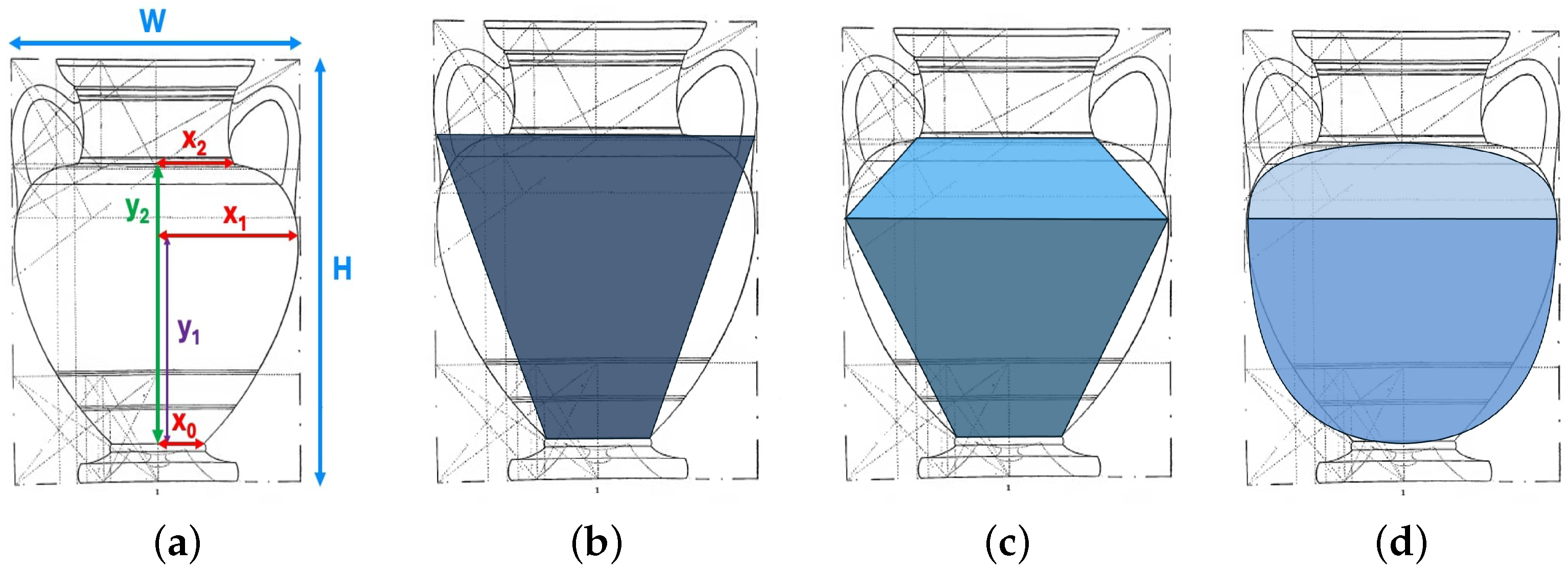

9. Case Study: Computing the Volume of Amphorae

As an illustration, consider computing the volumes of amphorae measured in detail by Caskey [68]. Here H denotes the height, D is the width (“diameter”) of the containing rectangle for each vase, and is the ratio of the height H to diameter D. The vase number and the corresponding page in Caskey’s book [68] with additional details are provided. Due to insufficient measurements in Caskey’s tables, his diagrams are used to approximate the following measurements needed for our investigation:

- Diameter of bottom of body.

- Diameter of body.

- Height of widest point of body.

- Diameter of shoulder.

- Height of spiral.

These measurements are represented as relative distances, with the diameter of the body . Using the columns listed in Section 6, the coordinates (following the convention laid out in Section 7.1) can be computed as follows:

- diameter of bottom of body.

- as the bottom of the vase coincides with the x-axis.

- diameter of body W.

- height of widest point of body.

- diameter of shoulder.

- height of spiral.

The relative measurements and the respective coordinates for each vase are listed in Table A2 and Table A3.

First, the computation for one amphora is shown, and then the results for the first 25 amphorae listed in [68] are presented.

9.1. Case Study I: Analyzing a Single Amphora

As a representative example, consider the following vase:

- Vase #7, p. 44: “Thetis Bringing Armor to Achilles”,(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153406—last accessed on 15 October 2025)

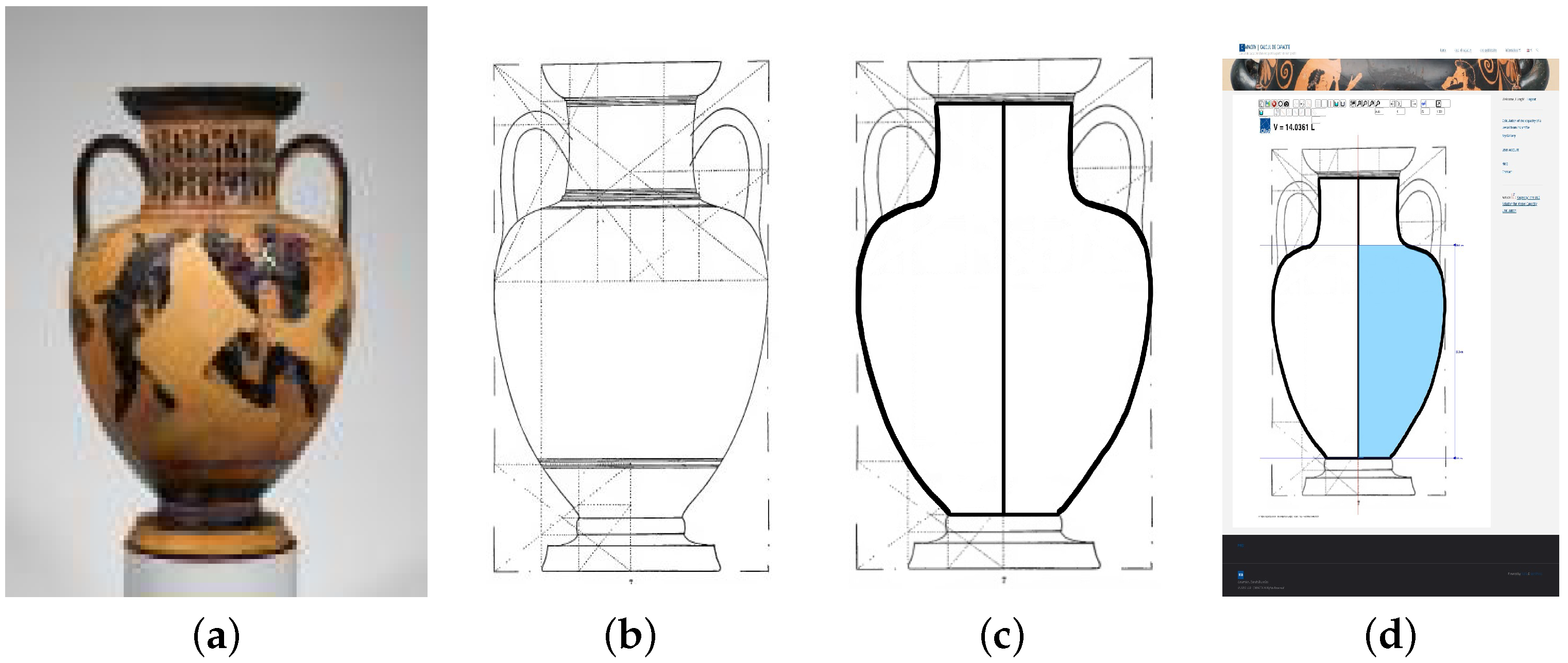

For this vase, the ratio (a variant of root-five rectangle, just as the golden ratio) and this vase is shown in Figure 29a:

Figure 29.

Steps involved in the computation of vase volume via contours. (a) Amphora; (b) layout; (c) contour; (d) volume computation.

Table 4.

Physical dimensions of vase #7 (p. 44 in [68]).

From the detailed layout of this vase in Figure 29b conducted by Caskey [68], a detailed contour shown in Figure 29c is created. Using this contour and the data from the above table extract, the volume is computed using the website at Université Libre Bruxelles (Figure 29d). The obtained volume is .

For this amphora, . Using this ratio, the relative vase measurements can be computed and summarized in Table 5 (from Table A2 in Appendix F):

Table 5.

Relative dimensions (width of the body equals 1) for vase #7 (p. 44 in [68]).

Once the relative vase measurements are computed, the vase coordinate for this vase can be computed. These are summarized in Table 6 (from Table A3 in Appendix G):

Table 6.

Relative coordinate values (following the convention in Section 7.1) for vase #7 (p. 44 in [68]).

Next, its volume is computed using the derived formula and by numerical integration of the profile volume provided by a computer program developed at Université Libre de Bruxelles (https://capacity.ulb.be/index.php/en/—last accessed on 15 October 2025). As mentioned in the introduction, this program allows one to upload the profile picture and specify the height of the vase. The application estimates the volume by adding small cylinders to provide very accurate volume estimates. This is illustrated in Figure 29d.

For illustration, consider the computation using the self-similarity of the underlying rectangles. For this vase and, therefore, root-five rectangles are used. The derivations are illustrated in Figure 30.

Figure 30.

Computing relative vase measurements from root-five rectangles. (a) Layout; (b) initial covering; (c) computing foot height; (d) computing shoulder.

First, the layout Figure 30a is enclosed into a square of side 1 and a root-five rectangle with height shown in Figure 30b. Examining the layout, one can see that the height of the foot is one-half the height of this rectangle (as seen from Figure 30c) giving the foot height as . The height of the neck and lip is and the diameter of the lip equals that of a foot (page 44 in [68]). Drawing the square with this height in Figure 30d gives the height of the shoulder from the bottom as . Note that this value is . Subtracting the height of the foot from this value gives . This is close to the value of in Table A1 in Appendix E.

For this vase, cm and therefore, the diameter is cm. The (real) height of the shoulder is cm. The approximate volume of the vase is then L.

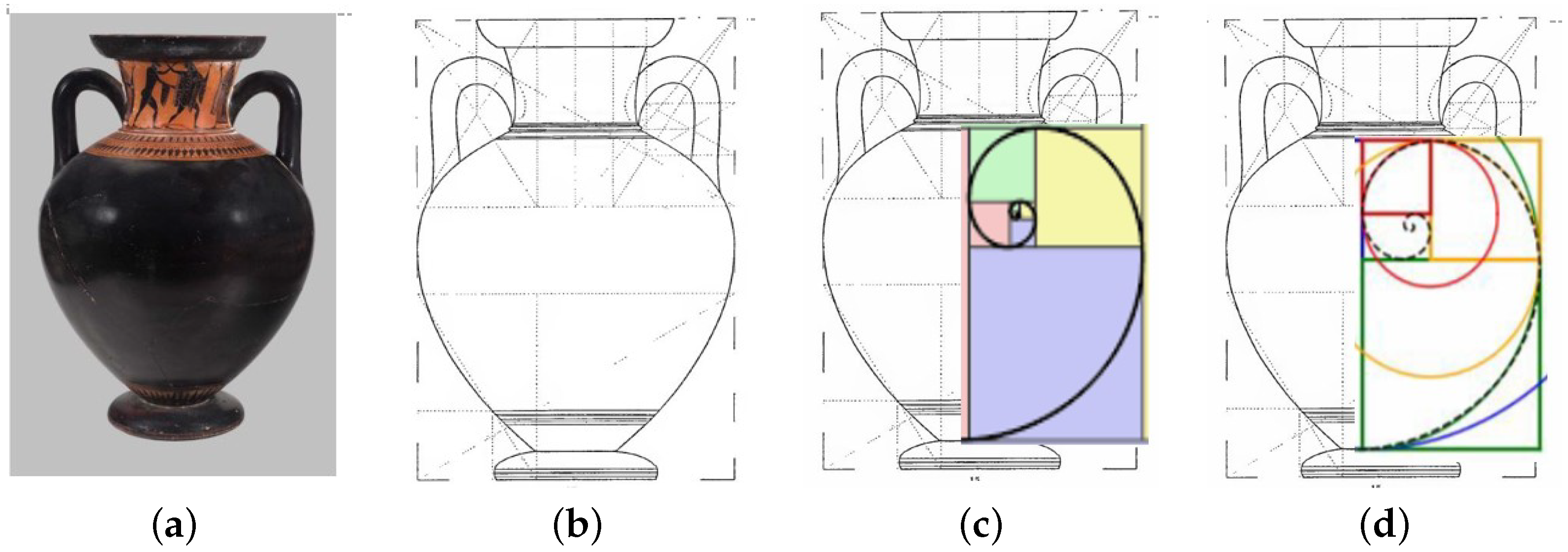

9.2. Case Study II: Analyzing Neck Amphorae from the J. Paul Getty Museum

In the previous case study, the proposed approximation was compared with the volume obtained by numerically integrating the vase contour. It would be instructive to compare the approximation with vases measured directly and reported in the literature. To that end, one can consider a publication from the international research project Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum (“corpus of ancient vases”), specifically #23 by Clark [96]. This publication describes detailed measurements of some amphorae and their volumes at the Getty Museum vase collection.

The first amphora on page 1 in [96] is “A: Theseus and the Minotaur, B: Youths on Horseback” (https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103VTV—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

Taking the average values of the estimates gives height to lip cm and width cm. Diameter of the neck is cm, diameter of the foot cm, and diameter of the mouth cm. The height of the edge of the foot is cm, the height of the lip cm. This gives the overall height cm. Then . With this ratio, this vase is similar to the neck amphora #14 in the Caskey’s dataset “Satyrs treading grapes” (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153409—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

Interestingly, the Getty Museum vase has the same pictures as vase #3 in [68] (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153403—last accessed on 15 October 2025) and both are attributed to the same region and time. However, the vase #3 in MFA has a much smaller ratio than its “twin” vase at the Getty Museum. The vase from the Getty Museum, the two vases from MFA (vase #3 and #14), and the layout for are illustrated in Figure 31:

Figure 31.

Similar amphorae from the Getty Collection and the Museum of Fine Arts. (a) Getty Museum ; (b) #3 Vase ; (c) #14 Vase ; (d) Layout .

From this layout, the height h of the neck can be estimated as of the height of the vase or cm. The height from the bottom of the vase to the shoulder is cm. The height from the foot to the shoulder is cm. The measurements can be summarized as follows:

The volume to the shoulder in Equation (35) gives L and the volume with the neck in Equation (36) gives L. The values reported by the Getty Museum in [96] are about 25% lower at and L, respectively.

Note that the volume reported in [96] is the actual volume, whereas the proposed approximations are based on the outer dimensions and do not take into account the vase thickness. If the average thickness of vase walls is assumed to be 1 cm, then this would reduce W and d by two centimeters to be cm and cm. This would result in updated volumes L and L. This results in a relative error of 15% in overestimating the volume.

9.3. Case Study III: Analyzing “Identical” Amphorae from the J. Paul Getty Museum and MFA

For the next study, the panel amphora on page 1 in [96], “A: Heracles seated between Hermes and Athena”, “B: Athena between two men.”, is considered.

Taking the average values of the estimates, height to lip cm and width cm. Diameter of the neck is cm, diameter of foot cm, and diameter of neck cm. The height of the edge of the foot is cm, the height of the lip cm. This gives the overall height cm. Then . From Table A1, the closest k is . There are several amphorae with the same k, but one of these vases has practically the same dimensions and k, namely vase #11 on page 47 in [68] ”Athena driving quadriga”, “B”: Bearded man driving quadriga” (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153386—last accessed on 15 October 2025).

The vase from the Getty Museum, its “identical” twin from MFA, and the profile for vase #11 are illustrated in Figure 32:

Figure 32.

Similar amphorae from the Getty Collection and the Museum of Fine Arts. (a) Getty Museum; (b) #11 Vase; (c) layout.

The relative dimensions from the layout are as follows. The ratio . The diameter of the shoulder is contained in the central square of a root-five rectangle applied to the whirling (“golden ratio”) rectangle. The height of the neck and lip is contained in four vertical whirling rectangles (). The (relative) height to the shoulder is then , giving the value cm. This gives and the height of the neck cm.

The measurements for these two amphorae can be summarized as follows:

The volume to the shoulder in Equation (35) gives us L and the volume with the neck in Equation (36) gives L. The values given in [96] are about 10% lower at (to glaze ring) and (to the rim) liters, respectively.

If the average thickness of the vase walls is 1 cm, then the width and neck diameter are reduced by two centimeters to and cm. This would result in updated volumes and . This yields similar relative errors of approximately 10% (underestimating) the reported volume.

9.4. Case Study IV: Analyzing Neck Amphorae from Caskey’s Book

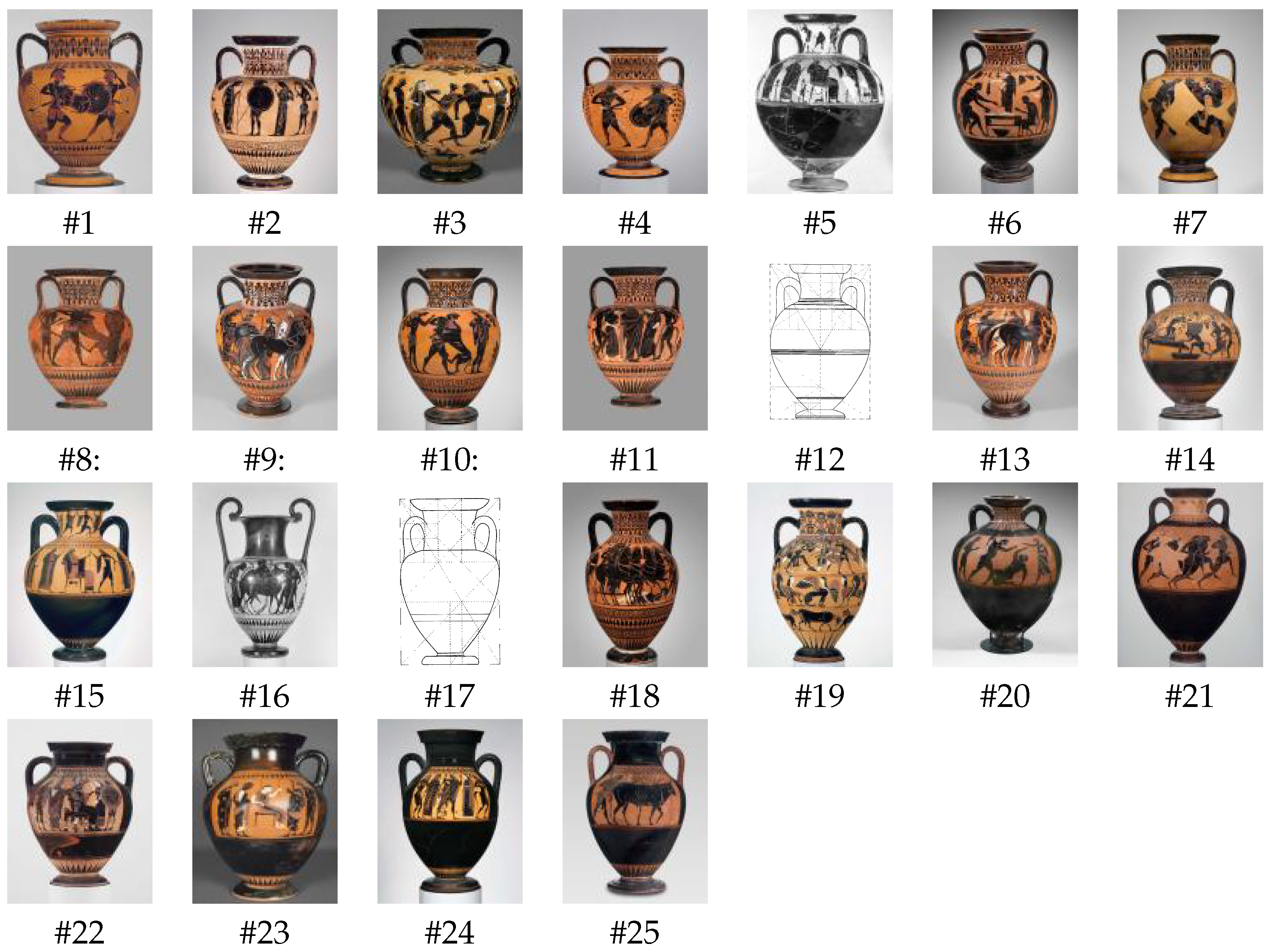

Now consider computing volume for the 25 amphorae (vases #1–#25) from Caskey [68]. This paper focuses on amphorae, as they are the most important type of vessel for storage and trade. These 25 amphorae are illustrated in Figure 33.

Figure 33.

Twenty-five amphorae (vase # from Caskey’s data).

The links for additional information on these vases are given in Appendix D. Out of the 25 vases, no URL was found for two vases, vase #12 and vase #17, although the detailed measurements are available for all.

The vase heights H and proportion ratios are given in Table A1 in Appendix E. Of the remaining 24 amphorae, 17 amphorae use root-five rectangles, and 3 amphorae (#2, #20, and #22) use root-two rectangles. The remaining four vases (#14, #21, #23 and #24) have the proportion and are classified as “static symmetry” vases, according to Hambidge’s notion of symmetry discussed in Section 3. The root-five is by far the most dominant type, reflecting the popularity of the golden ratio and its variants. Interestingly, there are no root-three amphorae in this particular set.

Using the data for amphorae, the parameters for the logarithmic spiral are estimated, including its center . The approximation formulas derived in Section 8 are considered. For the amphorae, contours from Caskey’s book were generated, and the data from Caskey’s dataset were used to solve the parameters of the vase (including the center of the logarithmic spiral ) and its height . The software package at Université Libre de Bruxelles was used to estimate the volume. The obtained results suggest that the 2-ellipsoid approximation provides a highly accurate estimate of the volume as reported in Table A5.

10. Discussions

10.1. Alternative Hypotheses

This paper is based on the fundamental assumption that the surface of the vase can be approximated by a logarithmic spiral and that there is sufficient motivation to do so. One could ask why a less complex shape, such as a parabola, was not considered. That is what we will be discussing in this section.

Consider a parabola that opens upward and has its axis of symmetry parallel to the y-axis. Such a parabola would have an equation as follows:

The right arm of this parabola will always have a slope that is positive and hence will never turn inwards, which is a fundamental property of the amphora vase.

The surface of the vase expands outwards, reaches a maximum diameter, and then turns inwards. The slope at the surface correspondingly varies as follows—the slope is positive but is decreasing in magnitude until it reaches 0 at the widest point of the vase, and then it changes parity and becomes negative, with increasing magnitude as we move closer to the neck.

The only part of the parabola where the slope behaves similarly is around its vertex. Therefore, we investigate a parabola that opens to the left and has its axis of symmetry parallel to the x-axis. While this parabola may satisfy the restriction imposed by the behavior of the slope, it fails to capture the asymmetric nature of the vase, i.e., the difference in the rate of change in the slope magnitude when it is positive and when it is negative.

Hence, it can be conclusively said that the surface of the amphora vases cannot be captured completely by a parabola.

10.2. Extension to Other Types of Vases

While focus is placed on the amphora class of vases, particularly the flat-bottomed painted type, it would be remiss not to discuss other types of vases. For this discussion, utilitarian point-bottomed amphorae, which were chosen as the primary type of transport container for various liquids traded by the Greeks [22].

Under the assumptions of the logarithmic spiral surface, the original formula derived by integration of the rotation of the logarithmic spiral (presented in Equation (30)) still holds. One can use that formula by changing the limits to the appropriate points, but it is very important to identify the section of the vase that can be fit to the logarithmic spiral.