Abstract

Centro Español de Metrología (CEM) is developing a quantum frequency standard based on trapped calcium ions, marking its entry into the landscape of the second quantum revolution. Optical frequency standards offer unprecedented precision by referencing atomic transitions that are fundamentally stable and immune to environmental drift. However, the challenge of developing such a system from scratch is unaffordable for a medium-sized National Metrology Institute (NMI), which seems to limit the ability of an institute such as CEM to contribute to this field of research. To overcome this, CEM has adopted a hybrid strategy, combining commercially available components with custom integration to accelerate deployment. This paper defines and implements an architecture adapted to the constraints of a medium-size NMI, where the main contribution is the systematic design, selection, and interconnection of the subsystems required to realize this standard. The rationale behind the system design is presented, detailing the integration of key elements for ion trapping, laser stabilization, frequency measurement, and system control. Current progress, ongoing developments, and future research directions are outlined, establishing the foundation for spectroscopic measurements and uncertainty evaluation. The project represents a strategic step toward strengthening national capabilities in quantum metrology for a medium-sized NMI.

1. Introduction

The fundamental advantage of optical quantum frequency standards is that, by working in the optical regime with different atomic or ionic species, better instability and uncertainty than those of caesium clocks can be achieved. However, the operation of these optical clocks relies on two fundamental technological advances. The first is the application of cutting-edge techniques for laser cooling, trapping, and the coherent interrogation of species that exhibit narrow optical transitions which need to be resolved. The second is the development of ultra-precise frequency metrology tools, such as frequency combs, which provide the ability to measure optical frequencies with high resolution [1]. As a consequence, advancements in these fields have led to research on and the development of optical clocks by many different groups using two leading architectures: optical lattices [2] and trapped ions [3].

At CEM, there is an awareness of the duty and responsibility NMIs have when implementing these advances, ensuring that the potential of quantum technologies is transformed into tangible benefits for science, industry, and society.

For this reason, considering the importance that optical frequency standards can have both for science and for the future redefinition, or mise en pratique, of the second [4], CEM is developing a standard based on ion-trapping technology. However, while keeping up to date with innovations is a major concern for the entire community, even more challenges arise when talking about medium-sized NMIs, such as CEM. Because of this, CEM has decided to approach frequency metrology from a different point of view, through the establishment of a frequency standard based on calcium ions, which will enable the use of commercially available equipment and therefore allowing an institute without a previous group working in the time and frequency domain to conduct new quantum standards research.

The research of this NMI is being developed through the MADQuantum–CM project, aimed at revolutionizing communications through the use of quantum technologies. To this end, as a network node, CEM will provide a frequency reference, which is essential for the synchronization of the nodes in the communication network [5].

2. State of the Art

Given the relevance optical clocks have, numerous developments are being made, from progress on optical lattice clocks with single species [6] to dual-mode operation [7], as well as developments in ion-trapped clocks [8].

Not only are these investigations reducing possible sources of noise, and therefore reaching uncertainties of 10−18 [9], they are also leading to the development of transportable clocks for comparisons between different systems [10]. Along those lines, companies all over the world are diving into the development of the state-of-the-art technology comprising optical clocks, such as ultra-stable lasers and ion traps, with the aim of developing commercially available optical clocks. It is with this technology that CEM is establishing its frequency standard.

3. Operational Principle

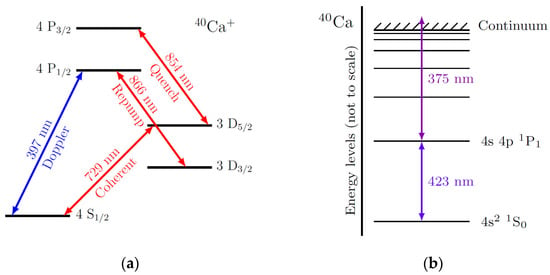

The isotope 40Ca is the most naturally abundant form of calcium and possesses two valence electrons in the 4s orbital. Notably, it has zero nuclear spin, which eliminates hyperfine splitting and thereby simplifies its atomic energy level structure, as illustrated in Figure 1a. The relevant electronic transitions for this work span wavelengths from 375 nm to 866 nm, all of which are accessible using commercially available laser systems. Furthermore, not only are the lasers involved available but, as described in Section 4, the ion trap system itself is a commercial solution [11] developed by Alpine Quantum Technologies (AQT, Innsbruck, Austria). For this reason, 40Ca ions are the ideal candidate for the realization of an optical frequency standard at CEM.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the 40Ca+ atomic structure; (b) schematic of the levels used in calcium to obtain photoionization.

The procedure for realizing a frequency standard using a 40Ca+ optical ion clock [12] begins with the generation of a low-pressure calcium vapor. This is achieved by ablating a calcium target, often referred to as a “waffle”, using a 515 nm pulsed laser, Coherent Flare NX 515 (Saxonburg, PA, USA). The resulting neutral atoms are then selectively ionized through a two-step photoionization process employing 423 nm and 375 nm lasers, Toptica’s MDL and iBeam smart (Munich, Germany), as illustrated in Figure 1b. The produced ions are subsequently confined in a linear Paul trap, AQT’s PINE SET-UP, consisting of four electrodes and two endcaps [13]. Once trapped, the ions undergo a multi-stage cooling sequence—Doppler cooling, polarization gradient cooling, and sideband cooling—to reduce their motional energy within the trap. This cooling is facilitated by lasers at 397 nm and 729 nm, along with repumping lasers at 866 nm and 854 nm, which are included in the Toptica’s MDL laser system, to prevent population-trapping in metastable D states during cooling and detection. The clock transition is driven by a highly stable 729 nm spectroscopy laser, Hz laser, whose frequency is locked using the Pound–Drever–Hall (PDH) technique [14]. State-selective detection is performed via fluorescence monitoring on the strong dipole-allowed 4S1/2–4P1/2 transition at 397 nm. Ions in the ground state scatter photons, while those excited to the metastable 3D5/2 state remain dark, a method known as electron shelving, which enables high-fidelity quantum state discrimination. Finally, the frequency of the ultra-stable laser probing the clock transition is measured using a fiber-based optical frequency comb, FC 1500-ULN from Menlo Systems (Martinsried, Germany), ensuring the traceability of the system.

4. Conceptual Design

As key components of the experimental setup necessary for the loading, trapping, cooling, and detection of the ions, the following elements are needed.

4.1. Ablation Laser

Although calcium ions can be generated through the use of an oven, this method has been proven to introduce contamination to the trap blades and degrade the vacuum conditions [15]. Oven-based loading typically requires a warm-up period ranging from seconds to minutes, during which the generated heat can cause residual heating of the trap and surrounding vacuum components. In addition, oxidation of the oven material can shorten its operational lifetime [16]. By contrast, laser ablation provides immediate temporal control: the production of neutral atoms can be started or stopped instantaneously. It also offers a highly localized source, faster and more precise timing of ion loading, and significantly reduced thermal load on the ion trap [17]. Although ovens are mechanically simpler and avoid the need for an ablation laser, they require continuous heating and can introduce long-term thermal stress and unwanted deposition, which is undesirable in precision systems. Consequently, ablation loading is a reliable approach for ion trap loading [18], and the preferred procedure for our system. This, combined with photoionization ensures isotope selectivity and controlled ion loading, forming an optimal strategy for precision ion trap experiments.

As outlined in Section 4.4, the PINE SET-UP is designed for the employment of an ablation laser available for the different ion species. For 40Ca+, a single pulse at 515 nm from a passively Q-switched diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) laser, offering a pulse duration of ~1 ns, is directed at the calcium target to produce a neutral atomic gas. The selected system for this is the Coherent Flare NX 515, a short-pulsed DPSS laser featuring a pulse width of 1.3 ns and a repetition rate of 2 kHz. The pulses are triggered via a transistor transistor logic (TTL) signal controlled through the system described in Section 4.7.

4.2. Laser System

The system is equipped with Toptica’s iBeam smart, a high-performance single-mode diode laser operating at 375 nm. This free-running diode laser supports external asynchronous digital modulation, making it suitable for precision applications. As described in Section 3, isotope-selective photoionization is achieved through a two-step process: the first step employs an external cavity diode laser (ECDL) at 423 nm to enable isotope selectivity, followed by ionization using the 375 nm iBeam smart laser.

Complementing this setup is Toptica’s modular, tunable single-mode diode laser system, the MDL pro, which integrates four narrow-linewidth diode lasers used in CEM’s experimental platform. These include lasers at 397 nm, 423 nm, 854 nm, and 866 nm. The MDL pro system is designed for low-noise operation, providing a typical linewidth of 150 kHz over 5 µs for the cooling and ionization lasers [19], and offers remote control capabilities via the digital control unit (DLC pro), enhancing stability and flexibility.

To ensure precise frequency stabilization, a low-finesse, low-drift optical reference cavity is employed. Active stabilization is achieved via a feedback loop that precisely controls the cavity length through piezoelectric and thermal actuators, ensuring sustained resonance with a caesium reference [20]. AQT’s Beech module, equipped with integrated proportional–integral (PI) controllers, can simultaneously stabilize the frequencies of up to four laser wavelengths. By utilizing external frequency shifters, the Beech module compensates for discrepancies between the target laser frequencies and the cavity’s resonance modes.

The system is optimized for use with the calcium-specific wavelengths provided by the MDL pro unit, that is, 397 nm, 423 nm, 854 nm, and 866 nm. The fiber-optic connections between the lasers, reference outputs, and cavity ensure seamless integration and reliable operation, making the Beech module a natural choice for CEM’s optical frequency standard.

Additionally, AQT’s ROWAN module has been incorporated into the setup. This module features an acousto-optic modulator (AOM) in a double-pass configuration, enabling precise frequency shifting, pulse modulation, and dynamic control of the laser beams.

4.3. High Stability Laser

In the development of a trapped-ion optical frequency standard, the ultra-stable laser is a critical component for achieving the precision and accuracy required in high-end metrology. Its frequency is stabilized using feedback control loops, most notably the Pound–Drever–Hall (PDH) technique, which locks the laser to a resonance mode of a Fabry–Pérot optical cavity acting as a narrowband frequency filter. This locking mechanism enables extremely low linewidths [21,22,23] in the order of sub-hertz, essential for long-term stability. For this purpose, Toptica provides an ultra-stable clock laser system, its clock laser system, Hz Laser, specifically designed for optical clocks, offering a linewidth below 1 Hz at one-second integration time.

To maintain spectral purity during transmission, the laser beam passes through a series of Fiber Noise Cancellation (FNC) modules [24]. These modules actively compensate for phase fluctuations introduced by light propagation through the optical fiber, using AOMs and radio-frequency (RF) modulation of both frequency and amplitude. The stabilized beam is then directed into an acoustically and thermally isolated cavity setup, which enables the PDH technique to be used. Finally, the PDH error signal is processed via Toptica’s Fast Analog Linewidth Control (FALC) pro and DLC pro modules, which feed back into the control loop to maintain laser stability.

4.4. Ion Trap

Building on advancements in trapped-ion quantum technologies, Alpine Quantum Technologies (AQT) developed the PINE TRAP system, based on the design of the University of Innsbruck and the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI). Through the meticulous selection of materials and precision fabrication techniques, the system achieves optimized thermal and electrical conductivity. As a result, it enables exceptionally low heating rates, less than one phonon per second at a trap frequency of 500 kHz, making it highly suitable for precision quantum control.

The ion trap is housed within an ultra-high-vacuum chamber, integrated into AQT’s modular PINE SET-UP platform. This comprehensive setup includes not only the trap and vacuum chamber, but also an RF resonator, vacuum pump, high numerical aperture (NA) objective lens, a pump controller, multiple optical access ports for cooling, detection, ablation loading, and photoionization lasers. The modularity and compactness of the PINE TRAP system facilitate streamlined installation and operation.

In addition to these elements, the system incorporates a magnetic control architecture designed to ensure stable operation of the ions. This consists of three pairs of electromagnetic coils mounted along the principal axis of the setup. Although these coils provide controlled stabilization of the magnetic field, and given the high-sensitivity of calcium ions to magnetic fluctuations, additional shielding is required. For this purpose, a µ-metal shield is planned. Its design is currently in progress, and a study of its effect on the overall system performance will be carried out.

It is by acquiring this solution that CEM has been able to establish a foothold in the time and frequency metrology community. As a medium-sized NMI, the in-house development of a custom ion trap would have required substantial time and resources, potentially delaying progress on optical frequency standards for years. In addition, the choice of the AQT PINE TRAP was guided by its proven reliability, the availability of technical support, and its compatibility with commercially available subsystems, factors that aligned with CEM’s hybrid integration strategy and ultimately made it the most suitable option for the project, balancing reliability, integration feasibility, and institutional constraints. The adoption of AQT’s commercial system thus represents a strategic and efficient path toward cutting-edge timekeeping capabilities.

4.5. Frequency Comb

One of the centerpieces of an optical frequency standard is the optical frequency comb [25], which enables the down-conversion of the stabilized laser frequency, which is locked to the transition into the microwave or RF domain. This conversion allows the resulting frequencies to be distributed and processed using conventional electronic systems. The integration of the frequency comb is essential for the project in order to distribute the reference to the quantum communication network.

The frequency comb operates by circulating a single laser pulse within an optical cavity, generating a train of pulses separated by the cavity’s round-trip time. The rate at which these pulses are emitted is known as the repetition rate. Each pulse is nearly identical, except for a phase shift between the carrier wave and the intensity envelope, referred to as the carrier–envelope offset (CEO) phase [26].

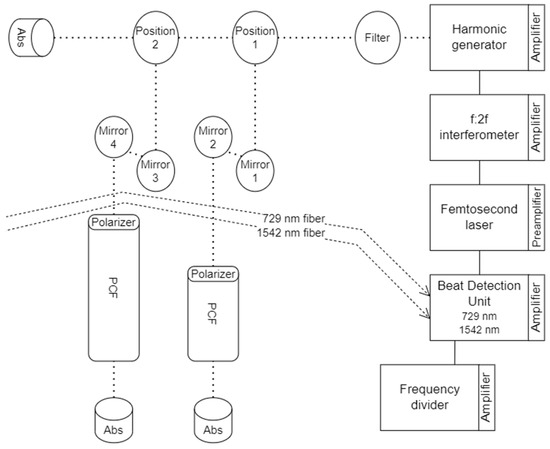

For this implementation, the Menlo Systems fiber-based optical frequency comb, FC 1500-ULN, is used, offering a repetition rate of 250 MHz and a CEO frequency of 20 MHz. To achieve a stabilized frequency signal, two free parameters must be stabilized: the comb spacing and the comb offset. To access the frequency offset of the FC1500 optical frequency synthesizer, the laser output is amplified in an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA), specifically P250 PM Pulse EDFA unit. Moreover, in combination with the P50 PM module, the High-Power Measuring Port (HMP) delivers a fiber-coupled, stabilized comb output.

In addition, the MVIS amplifier and control module incorporates a Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) and spectral extension into the visible range by means of a Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF). This configuration extends the stabilized comb spectrum to the 500–1050 nm range by amplifying the light from the fiber ring, where the frequency is doubled and sent to a highly non-linear fiber for spectral broadening. To interface with the clock laser, the Beat Detection Unit (BDU), at 729 nm, generates and measures the beat signal between the comb and the external continuous wave laser through fiber-coupled optics.

As previously noted, ultra-low-noise microwave generation in the MHz and GHz range is especially needed when aiming to distribute the reference frequency. The Microwave Ultrastable RF Output module provides a commercial solution utilizing a high-sensitive photodetector and a frequency divider.

Figure 2 presents a schematic overview of the Menlo Systems’s setup where the units, from top to bottom, are MVIS SHG, P250 PM Pulse EDFA with HMP, FC1500-ULN, BDU 729, and the Microwave extension package. This system comprises the optical frequency comb, a technology whose evolution over recent decades [27] has been noteworthy in advancing time precision and frequency metrology.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the optical frequency comb setup.

4.6. Detection System

A robust detection system is required for a range of tasks in an optical frequency standard, including frequency monitoring, stability control, and fluorescence detection. These applications demand high sensitivity and fast frame rates to accurately capture the weak fluorescence signals emitted by trapped ions. Different tools can be used for fluorescence detection, from photomultiplier tubes (PMT) to avalanche photodiodes (APD) [28]. Among the various options, an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) was selected for the present system. While PMT and APDs offer excellent time resolution and sensitivity for single-channel photon-counting, they do not provide spatial information. In contrast, the EMCCD allows us to directly image the ion fluorescence, which allows for successful ion-trapping to be confirmed. In addition, this system enables not only spatial resolution to be recorded, but also the temporal evolution of the ion position inside the trap, offering different acquisition modes [29]. At this stage of the project, the EMCCD provides evidence of ion confinement and enables the alignment and optimization of the trapping setup.

The specific model chosen is the Andor iXon Ultra 897 (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK), a widely adopted solution in ion spectroscopy experiments due to its properties. This is made up of a back-illuminated 512 × 512 sensor with 16 µm × 16 µm pixel size and an electron multiplier gain up to 1000, which allows for single photon detection. Furthermore, the camera supports a frame rate of 56 fps and incorporates a thermoelectric cooling system that significantly reduces dark current, thereby minimizing thermal noise and enhancing signal fidelity.

4.7. Control System

Automatization, synchronization, and system control are some of the most critical processes in experiments with high requirements, such as those involving an optical frequency standard. Due to this, a control system which allows for high precision is needed for tasks such as laser control, frequency modulation, data acquisition, or even the execution of precise experimental sequences. For this purpose, the ARTIQ control framework [30] was adopted, in combination with various modules of the Sinara hardware.

At the core of the control architecture is the Kasli v2.0.2 FPGA carrier board from Creotech Instruments (Piaseczno, Poland), which serves as the master or main controller. Its FPGA is part of the Artiq-7 family, specially designed for high-performance applications, and includes 512 MB of DDR3 RAM. The board features 12 Eurorack Extension Module (EEM) ports, enabling seamless integration with the rest of the modules. A digital input/output extension module, specifically the DIO SMA v1.4.2, was acquired. It provides eight digital I/O channels organized into two banks with switchable directionality. The delivered outputs can supply TTL level signals into 50 Ω loads with pulse widths as short as 5 ns. This is necessary, for example, for laser pulse triggering, as stated in Section 4.1.

For RF signal generation with high-accuracy, DDS Urukul v1.5.5 modules were selected in both available models: AD9910 and AD9912. These modules are needed for the control of different optical components, such as AOMs or electro-optic modulators (EOMs). Each unit offers four independent channels which can generate frequency signals over 400 MHz, with a resolution of 0.25 Hz and 8 µHz for AD9910 and AD9912, respectively, and with power attenuation ranging from 0 dBm up to −31.5 dBm.

However, the Urukul output has limited power, which can limit the correct operation of the AOMs and EOMs. To address this, a Booster which amplifies the RF signal up to useful levels for these devices was acquired, specifically the High-Linearity Booster from Creotech Instruments. This device counts eight channels, each with up to 5 W output power and 32 dB power gain.

Finally, accurate and high-speed data acquisition is a vital aspect of system control. For this, the Sampler v2.3.1 analog-to-digital converter (ADC) module was selected. It features eight input channels with an update rate of up to 1.5 MSPS (mega-samples per second), enabling real-time monitoring and the implementation of digital feedback loops within the control system.

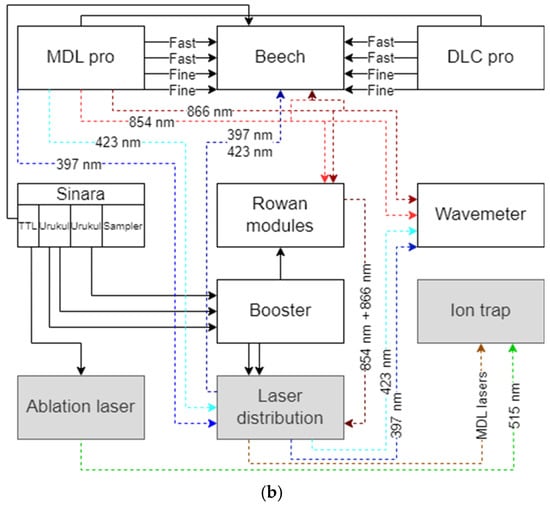

4.8. General Overview

The experimental platform developed at CEM for realizing a trapped-ion optical frequency standard brings together a tightly integrated set of subsystems, each tailored for precision, stability, and scalability. At its core is a modular infrastructure built around a commercial ion trap system, housed in an ultra-high-vacuum environment and supported by dedicated electronics and optics for ion generation, cooling, and interrogation.

Laser systems span a broad spectral range and serve multiple roles—from ablation loading and isotope-selective photoionization to Doppler and sideband cooling. A key element is the ultra-stable clock laser, at 729 nm, whose frequency is locked to 40Ca+ narrow atomic transition, using high-finesse cavity stabilization techniques. This laser forms the basis of the optical reference and is distributed through noise-canceled fiber links to maintain coherence across the setup.

To bridge the optical and microwave domains, a fiber-based optical frequency comb enables traceable frequency measurements and supports synchronization with external systems.

Detection is carried out using high-sensitivity imaging hardware capable of resolving single-ion fluorescence, while control and timing are orchestrated through a flexible FPGA-based system that supports real-time sequencing and feedback.

The schematic in Figure 3 illustrates the interplay between these components, highlighting the layered architecture that underpins the system’s performance. Together, they form a robust foundation for advanced time and frequency metrology, and position CEM to contribute to emerging quantum technologies and international standards.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the integration of all systems. (a) Integration of ultra-stable laser, frequency comb, and detection unit; (b) integration of MDL lasers and control systems.

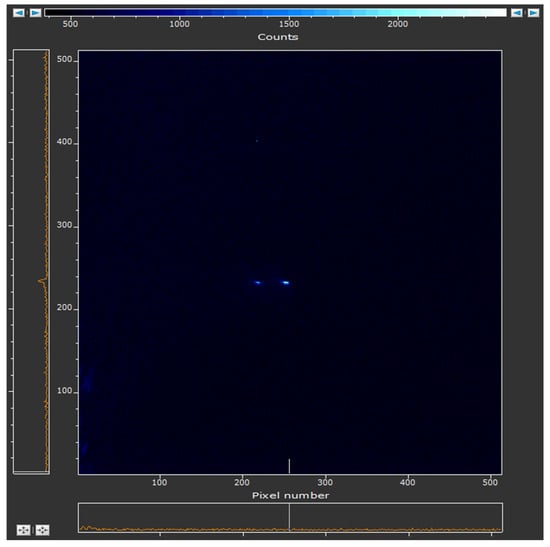

5. Outlook

With the installation of the system completed and the first ions successfully trapped earlier this year, as illustrated in Figure 4, CEM now enters a critical phase in the development of its optical frequency standard. The immediate objective is to carry out initial spectroscopic experiments, accurately measure the clock transition of the trapped 40Ca+ ions, perform Rabi and Ramsey sequences, conduct magnetic field characterization and compensation, and validate ion-trap characteristics such as heating rate. These activities form part of a broader verification and validation strategy that will progressively establish the system’s uncertainty budget. Achieving this requires the full deployment of the control infrastructure, centered around the ARTIQ framework and the selected Sinara hardware modules.

Figure 4.

EMCCD camera image of the first trapped ions.

The control software must be developed to handle a wide range of tasks, from basic TTL signal generation and the triggering of single laser pulses to the execution of complex pulse sequences. These capabilities will support the first experimental procedures, including ion detection, probing of the clock transition, and real-time data acquisition. In parallel, system monitoring and visualization is implemented using Grafana [31], allowing for the intuitive graphical control of laser parameters, such as laser current, temperature, applied piezo control voltage, lock status and lock slow signals of the MDL lasers, environmental conditions, such as the temperature and humidity of the laboratory, chambers and EOM temperatures, and hardware interconnections, Beech cavity transmission values and imaging, cavity pressure, ion pump current, temperature, battery voltage, and the pressure of the 729 nm high-finesse cavity.

Once the initial spectroscopy is completed, attention will shift to characterizing and quantifying systematic frequency shifts that affect the accuracy of the standard. These include Zeeman shifts due to magnetic fields, second-order Doppler shifts from residual ion motion, and excess micromotion within the trap. Special consideration will be given to the potential mitigation offered by operating at the magic wavelength [32,33], which can suppress certain systematic effects. The results of these measurements will feed directly into the evaluation of the standard’s uncertainty budget.

Looking ahead, CEM aims to become an active node within the MADQuantum–CM project, contributing a stable and traceable optical frequency reference to the broader quantum communication and metrology network. This long-term integration will position CEM as a key partner in advancing national and international timekeeping capabilities.

6. Conclusions

The development of a trapped-ion optical frequency standard at CEM marks a significant step toward establishing a national reference in quantum metrology. By leveraging commercially available components and a modular architecture, the system combines precision, scalability, and accessibility, making advanced timekeeping technology attainable for a medium-sized NMI. This effort is defined by the integration of subsystems into a functional architecture suited to the constraints of CEM.

With the infrastructure now in place and the first ions successfully trapped, the project is entering its experimental phase. Upcoming efforts will focus on probing the clock transition, refining control protocols, and characterizing systematic frequency shifts. These measurements will provide experimental data for the uncertainty budget and are expected to demonstrate a fractional frequency instability approaching the 10−16 level at the relevant averaging time. These results will validate the system’s performance against international standards.

Beyond its technical milestones, this initiative positions CEM as a strategic contributor to the MADQuantum–CM network, where it will serve as a reliable frequency node supporting collaborative research in quantum communication and precision timing. The project’s ultimate purpose is to provide a frequency reference for national and European quantum infrastructures, enabling comparisons via transportable optical clocks, satellite-based links, or even fiber networks. In this way, the project not only strengthens national capabilities but also reinforces Europe’s broader push toward quantum-enabled infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.d.A. and Y.Á.; methodology, A.P. and I.C.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, A.P., I.C. and D.d.M.; resources, A.P. and I.C.; data curation, A.P., I.C., D.d.M. and D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and I.C.; visualization, Y.Á. and D.P.; supervision, J.D.d.A. and Y.Á.; project administration, J.D.d.A. and Y.Á.; funding acquisition, J.D.d.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been conducted within the framework of the MADQuantum–CM project, supported by the Next Generation EU resilience funding and the Community of Madrid, marco del Componente 17, Inversión 01.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diddams, S.A.; Bergquist, J.C.; Jefferts, S.R.; Oates, C.W. Standards of time and frequency at the outset of the 21st century. Science 2004, 306, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeppli, A.; Kim, K.; Warffield, W.; Safronova, M.S.; Ye, J. A clock with 8 × 10−19 systematic uncertainty. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 023401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spieß, L.J. An Optical Clock Based on a Highly Charged Ion. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hannover, Hanover, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, H.S.; Godun, R.M.; Huntemann, N.; Le Targat, R.; Pizzocaro, M.; Zawada, M.; Abgrall, M.; Akamatsu, D.; Álvarez Martínez, H.; Amy-Klein, A.; et al. Robust Optical Clocks for International Timescales (ROCIT). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2889, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid Quantum. MadQCI. Available online: http://madqci.es (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Kobayashi, T.; Nishiyama, A.; Hosaka, K.; Akamatsu, D.; Kawasaki, A.; Wada, M.; Inaba, H.; Tanabe, T.; Yasuda, M. Improved absolute frequency measurement of 171Yb at NMIJ with uncertainty below 2 × 10−16. Metrologia 2025, 62, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, D.; Kobayashi, T.; Hisai, Y.; Tanabe, T.; Hosaka, K.; Yasuda, M.; Hong, F.-L. Dual-Mode Operation of an Optical Lattice Clock Using Strontium and Ytterbium Atoms. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2018, 65, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludlow, A.D.; Boyd, M.M.; Ye, J.; Peik, E.; Schmidt, P.O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 673–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, S.M.; Chen, J.-S.; Hankin, A.M.; Clements, E.R.; Chou, C.W.; Wineland, D.J.; Hume, D.B.; Leibrandt, D.R. An 27Al+ quantum-logic clock with a systematic uncertainty below 10−18. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 033201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt. Publishable Summary for 22IEM01 TOCK Transportable Optical Clocks for Key Comparisons; European Metrology Partnership: Braunschweig, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alpine Quantum Technologies. Pine-trap. Available online: https://www.aqt.eu/products/pine-trap/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Caballero, I.; Palos, A.; de Mercado, D.; Álvarez, Y.; Peral, D.; de Aguilar, J.D. Optical quantum frequency standard bases for MADQuantum-CM communication network. In Proceedings of the 2025 25th Anniversary International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Barcelona, Spain, 6–10 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guggemos, M. Precision spectroscopy with trapped 40Ca+ and 27Al+ ions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Drever, R.W.P.; Hall, J.L.; Kowalski, F.V.; Hough, J.; Ford, G.M.; Munley, A.J.; Ward, H. Laser phase and frequency stabilization using an optical resonator. Appl. Phys. B 1983, 31, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, K.; Lange, W.; Keller, M. All-optical ion generation for ion trap loading. Appl. Phys. B 2011, 104, 744–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battles, K.D.; McMahon, B.J.; Sawyer, B.C. Absorption spectroscopy of 40Ca atomic beams produced via pulsed laser ablation: A quantitative comparison of Ca and CaTiO3 targets. Appl. Phys. B 2024, 130, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.H.; Muralidharan, S.; Hablützel, R.; Croft, G.; Theophilo, K.; Owens, A.; Lekhai, Y.N.D.; Thomas, S.J.; Deans, C. A comparison of calcium sources for ion-trap loading via laser ablation. Appl. Phys. B 2025, 131, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Matsuoka, L.; Osaki, H.; Fukushima, Y.; Hasegawa, S. Trapping Laser Ablated Ca+ Ions in Linear Paul Trap. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 45, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Taylor, P.; Gill, P. Laser Linewidth at the Sub-Hertz Level; NPL Report CLM 8; NPL: Teddington, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- TOPTICA Photonics. Laser Rack Systems; TOPTICA Photonics: Gräfelfing, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Takekoshi, T. Methods and Apparatuses for Laser Stabilization. U.S. Patent EP3940898B1, 21 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Black, E.D. An introduction to Pound-Drever-Hall laser frequency stabilization. Am. J. Phys. 2001, 69, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Subhankar, S.; Britton, J.W. A practical guide to feedback control for Pound-Drever-Hall laser linewidth narrowing. Appl. Phys. B 2025, 131, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donley, E.A.; Heavner, T.P.; Levi, F.; Tataw, M.O.; Jefferts, S.R. Double-pass acousto-optic modulator system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2005, 76, 063112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsch, T.W. Nobel lecture: Passion for precision. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2006, 78, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, D. Ultrafast Coherent Excitation of 40Ca+. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, M.; Fischer, M.; Hänsel, W.; Steinmetz, T.; Lessing, M.; Holzberger, S.; Cleff, C.; Hänsch, T.W.; Mei, M.; Holzwarth, R. 20 Years and 20 Decimal Digits: A Journey with Optical Frequency Combs. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2019, 31, 1898–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhelm, J.; Kirchmair, G.; Roos, C.F.; Blatt, R. Experimental quantum information processing with 43Ca+ ions. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 062306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M. Optical Clocks with Trapped Ions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- M-Labs, ARTIQ. Advanced Real-Time Infrastructure for Quantum Physics Web Page; M-Labs, ARTIQ: Hong Kong, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Grafana, version 12.3.; GrafanaLabs: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Liu, P.; Huang, Y.; Bian, W.; Shao, H.; Guan, H.; Tang, Y.-B.; Li, C.-B.; Mitroy, J.; Gao, K.-L. Measurement of Magic Wavelengths for the 40Ca+ Clock Transition. Phy. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 223001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Kimble, H.J.; Katori, H. Quantum State Engineering and Precision Metrology using State-Insensitive Light Traps. Science 2008, 320, 1734–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).