The Critical Role of International Comparisons in Global Metrology System: An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Uncertainty in Measurement

3. Methodology and Process of International Key Comparisons

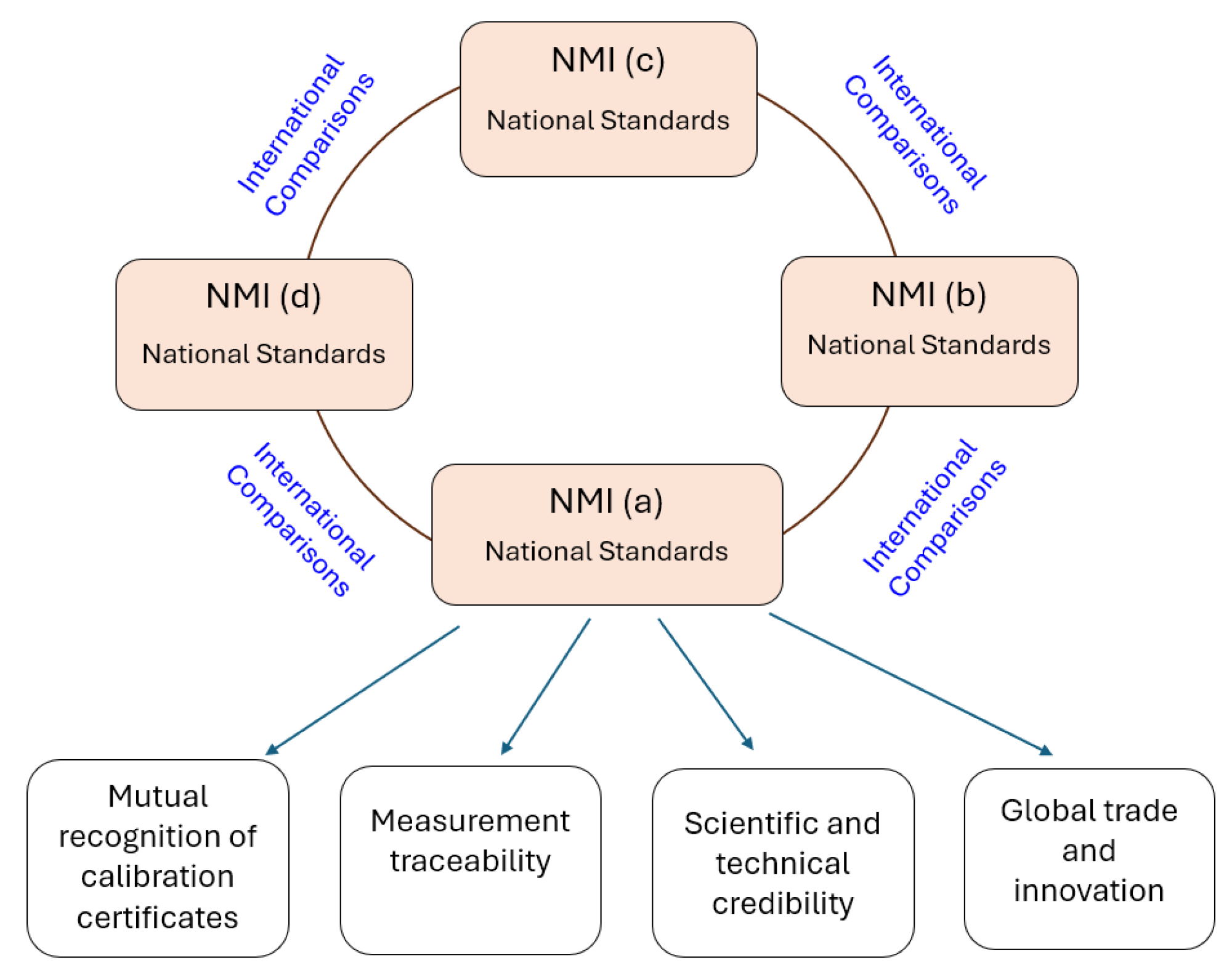

4. National Metrology Institutes: Ensuring Global Measurement Consistency and Traceability

- -

- The Consultative Committee for Length (CCL) has conducted key comparisons of optical frequency and wavelength standards, such as CCL-K11 [79,90,91]. These comparisons are used to ensure uniformity in laser wavelength measurements across different NMIs. The comparisons CCL-K1 focus on the calibration of gauge blocks by optical interferometry, to maintain length measurement equivalence and traceability [83,92]. These CCL key comparisons have supported length metrology development and the realization of the metre.

- -

- The Consultative Committee for Mass and Related Quantities (CCM) organized the first key comparison CCM.M-K8.2019 for realizations of the kilogram definition based on the Planck constant, with a final report published in 2020 [93]. This comparison is used to determine agreement between realizations of the kilogram using Kibble balances, joule balances, and the X-ray Crystal Density (XRCD) method. The KCRV has a deviation of −0.0188 mg (with a standard uncertainty of 0.0075 mg) from the mass unit maintained by the BIPM working standards (nominal mass is 1 kg). The second CCM key comparison CCM.M-K8.2021 for realizations of the kilogram definition was conducted in 2021–2022 [94]. Its KCRV has a standard uncertainty of 0.0074 mg and a deviation of −0.0152 mg from the 1 kg mass unit maintained by the BIPM working standards.

- -

- BIPM has carried out an ongoing on-site key comparison of Josephson voltage standards among NMIs under the denomination BIPM.EM-K10.a (1 V) and BIPM.EM-K10.b (10 V) under the auspices of the Consultative Committee for Electricity and Magnetism (CCEM) [95]. A recent comparison between the NMI of Finland and BIPM was reported in 2021 [96]. Their final results were in good agreement within the combined relative standard uncertainty of 2.5 parts in 1010 for the nominal voltage of 10 V.

- -

- CCT-K7.2021 key comparison of water-triple-point (TPW) cells was conducted between 19 NMIs, with its final report approved by the Consultative Committee for Thermometry (CCT) in 2023 [97]. The maximum difference between two transfer cells was 92 μK, with a standard deviation of 26 µK, which shows an almost factor-of-two improvement compared to CCT-K7 results. Compared to the previous comparison, CCT-K7 [98], this recent comparison has shown major improvements in the quality of TPW cells, definition of national references, and quality of uncertainty assessments.

- -

- The Consultative Committee for Photometry and Radiometry (CCPR) has organized a key comparison CCPR-K1.a.2017 for Spectral Irradiance in the wavelength range of 250 to 2500 nm using Tungsten quartz halogen lamps (1000 W) as artifacts [99]. The relative standard uncertainties of the KCRV were estimated to be 0.08% to 0.28%. The measurement uncertainties reported by the participants in CCPR-K1.a.2017 were, in general, less than those claimed in the previous comparison for Spectral Irradiance (CCPR-K1.a). The final report shows that ~80% of all results (at all wavelengths) agree with the KCRV within 1% at 250 to 2500 nm, which is similar to the results of the previous CCPR-K1.a comparison (published in 2006) [100].

- -

- The Consultative Committee for Acoustics, Ultrasound and Vibration (CCAUV) organized the first key comparison CCAUV.A-K4 for free-field microphone sensitivity derived using the reciprocity technique [101]. The travelling standards were two ½ inch laboratory-standard microphones (Brüel & Kjær 4180), which were calibrated at 1 kHz to 40 kHz under free-field conditions in an anechoic chamber. The submitted results of all seven NMIs were included in the estimation of the KCRVs. The final report shows that ~94% of all results (for all frequencies) agree with the KCRV within the uncertainties.

- -

- The CCQM has organized three KCs on natural gas mixtures, namely CCQM-K1, CCQM-K16 and CCQM-K23, to ensure comparability in natural gas composition reference standards among the NMIs [80,102,103,104,105]. The final report for a more recent KC for natural gas (CCQM-K118) was published in 2022 [106]. In this comparison, the KCRVs have been derived using a weighted mean computed from the largest consistent subset (LCS) of the submitted results. Some of the participants reported one or a few discrepant results, partly due to the heterogeneity and heteroscedasticity of the datasets. Overall, the results in CCQM-K118 have shown good comparability of the metrology standards for natural gas composition in the 14 participating institutes.

5. Industrial Calibration Laboratories: CMC Validation and Risk Management

5.1. Validation of CMC

5.2. Financial and Legal Binding of Measurements

5.3. Risk Management and Decision Rule

6. Research Laboratories: Pushing the Frontiers of Measurement Science

6.1. Pushing the Frontiers of Measurement Science

6.2. Benchmarking via International Comparisons

- -

- The Consultative Committee for Time and Frequency (CCTF) has initiated a roadmap for redefining the SI second to enhance precision, accuracy, and long-term stability of timekeeping. This initiative is driven by advancements in optical frequency standards, such as those based on 171Yb and 87Sr, which are intrinsically accurate at the level of parts in 1018, two orders of magnitude lower than that of traditional 133Cs microwave atomic clocks [166,167,168,169,170]. The redefinition aims to improve the accuracy and stability of International Atomic Time (TAI) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) [12,164,167,170,171,172,173]. An international comparison of optical frequencies via a transportable optical lattice clock and another comparison of optical clocks through very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) have been conducted to check the consistency of optical clocks at the fractional uncertainty of 10−18 level on an intercontinental scale [81,162].

- -

- NPL and the University of Cambridge had reported their work to develop a quantum current standard using single-electron pumps [174]. They compared the electron pump current with a reference current generated outside the pump cryostat, with an uncertainty on the order of 1 ppm. This is an important work in Quantum Metrology Triangle (QMT) experiments to check the self-consistency of the three fundamental quantum electrical standards [163,175,176].

- -

- A pilot study on AC voltage comparisons was conducted in 2024 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and BIPM [147,148]. The aim of this comparison is to harmonize quantum voltage standards globally. This pilot study focuses on quantum-based Josephson voltage standards to ensure consistency in AC voltage measurements. The BIPM’s transportable Programmable Josephson Voltage Standards (PJVSs) were compared to NIST’s Josephson Arbitrary Waveforms Synthesizer (JAWS). They have achieved a type A uncertainty of a few parts in 109 for a 10 Hz sine wave at 2 V rms in this comparison.

- -

- Comparison between NIST and National Institute for Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) has been conducted using Graphene and GaAs Quantized Hall resistance (QHR) Devices [82]. In this work, several graphene QHR devices from NIST were compared to GaAs QHR devices and a 100 Ω standard resistor from AIST. Comparisons between the QHR devices have been reported with uncertainties of less than 5 nΩ/Ω.

- -

- An inter-laboratory comparison on quantum resistance (memristor) between 3 NMIs and 3 research laboratories has been reported [165]. The results show the consensus values of this comparison have deviations of −3.8% and 0.6% from the agreed SI values for the fundamental quantum of conductance, G0 and 2G0, respectively. The consensus values’ deviations from the SI values are well covered by their expanded measurement uncertainty.

- -

- A comparison was conducted by four laboratories for measuring the detection efficiency of free-running InGaAs/InP single-photon avalanche detectors (SPAD) at the wavelength of 1550 nm [177]. The detection efficiency for the mean photon number per pulse was between 0.01 and 2.4. The measured efficiency values by the participants are all consistent within the claimed uncertainties. This study is a good preparation for organizing future international comparisons of the detection efficiency of single-photon detectors at telecom wavelengths.

7. The Technical Value of International Comparisons

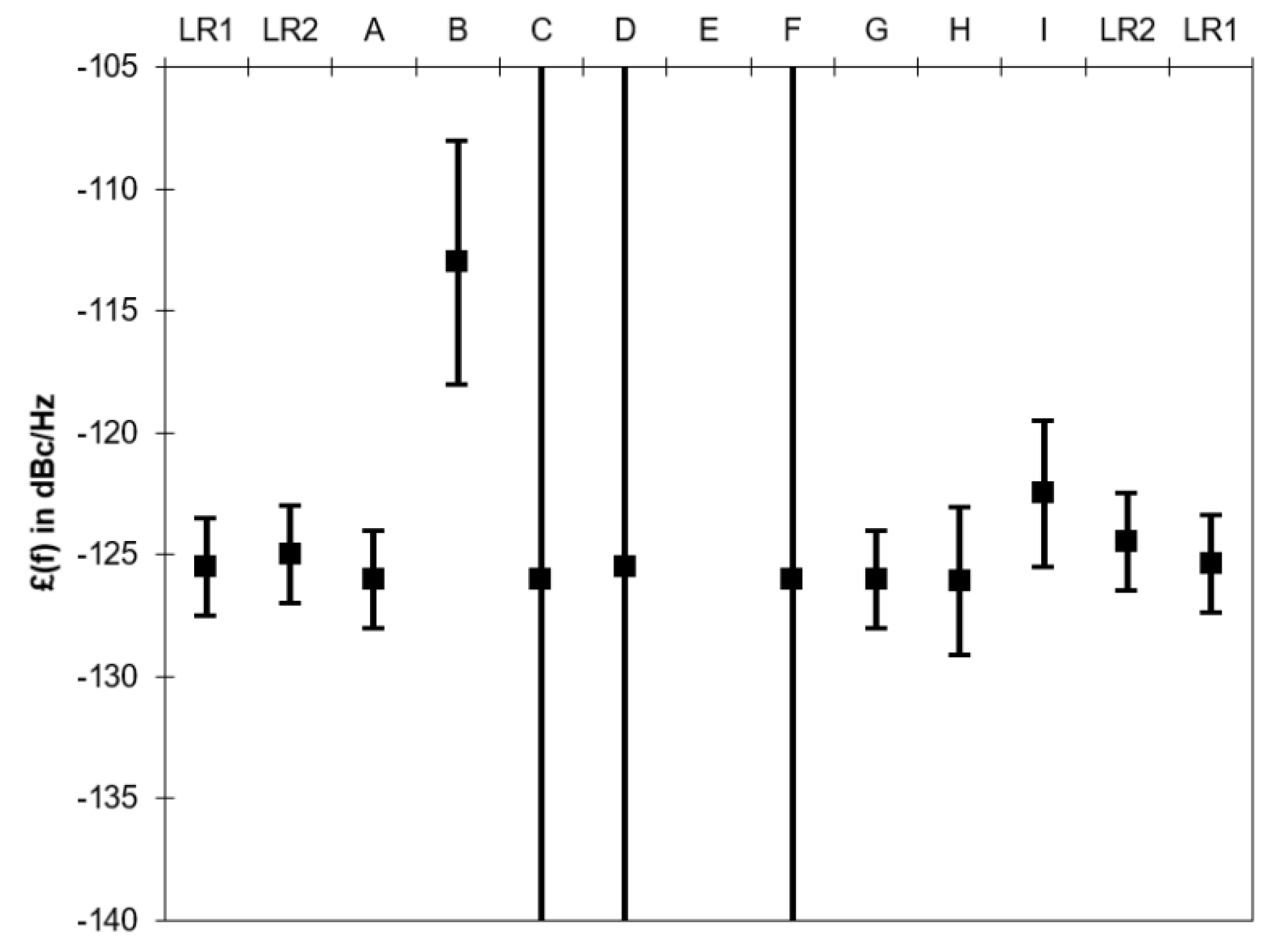

7.1. Case Study: Phase Noise Inter-Laboratory Comparison

7.2. Case Study: Comparison of Particle Charge Concentration and Particle Number Concentration

7.3. Discussion

8. Summary

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIPM | Bureau International des Poids et Mesures |

| CC | Consultative Committees |

| CGPM | General Conference on Weights and Measures |

| CIPM | Comité International des Poids et Mesures |

| CMC | Calibration and measurement capability |

| ILAC | International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation |

| IPK | International Prototype of the Kilogram |

| IPM | International Prototype of the Metre |

| KC | Key comparison |

| KCDB | Key comparison database |

| MRA | Mutual Recognition Arrangement |

| NMI | National Metrology Institute |

| OIML | International Organization of Legal Metrology |

| RMO | Regional Metrology Organization |

| SC | supplementary comparison |

| SI | International System of Units |

| AIST | Advanced Industrial Science and Technology |

| CCL | Consultative Committee for Length |

| CCQM | Consultative Committee for Amount of Substance: Metrology in Chemistry and Biology |

| CCTF | Consultative Committee for Time and Frequency |

| CRV | Comparison reference value |

| DoE | Degree of equivalence |

| EURAMET | European Association of National Metrology Institutes |

| GUM | Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement |

| JAWS | Josephson Arbitrary Waveforms Synthesizer |

| KCRV | key comparison reference value |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PJVS | Programmable Josephson Voltage Standard |

| PT | Proficiency testing |

| QHR | Quantized Hall resistance |

| QMT | Quantum Metrology Triangle |

| SSB | Single sideband |

| TAI | International Atomic Time |

| TFPI | Tandem Fabry–Pérot interferometer |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

| VLBI | Very long baseline interferometry |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardization |

| QMS | Quality management system |

| LCS | Largest consistent subset |

| CCU | Consultative Committee for Units |

| CCEM | Consultative Committee for Electricity and Magnetism |

| CCT | Consultative Committee for Thermometry |

| CCAUV | Consultative Committee for Acoustics, Ultrasound and Vibration |

| CCPR | Consultative Committee for Photometry and Radiometry |

| CCM | Consultative Committee for Mass and Related Quantities |

| SPAD | Single-photon avalanche detector |

| XRCD | X-ray crystal density |

| CRM | Certified Reference Material |

References

- Wallard, A.J. The Organization of Metrology. In Proceedings of the International School of Physics “Enrico Fermi”; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 166, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T. From Artefacts to Atoms: The BIPM and the Search for Ultimate Measurement Standards; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, T. The Metre Convention and World-Wide Comparability of Measurement Results. In Proceedings of the Accreditation and Quality Assurance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 9, pp. 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Placko, D. Metrology in Industry: The Key for Quality; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781905209514. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; ISO/IEC General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO/IEC 17034; ISO/IEC General Requirements for the Competence of Reference Material Producers. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO/IEC 17043; ISO/IEC Conformity Assessment—General Requirements for Proficiency Testing. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Richter, W. Comparability and Recognition of Chemical Measurement Results—An International Goal. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1999, 365, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopelko, L.A.; Kustikov, Y.A.; Okrepilov, M.V.; Kolobova, A.V.; Migal, P.V.; Krylov, A.I.; Vonskiy, M.S.; Chubchenko, I.K.; Efremova, O.V.; Kulyabina, E.V.; et al. Development of International Key Comparisons in the Field of Chemico-Analytical Measurements. Meas. Tech. 2021, 64, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz, R.I. International Comparability of Chemical Measurement Results. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 374, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, W. How to Achieve International Comparability for Chemical Measurements. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2000, 5, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM. The International System of Units (SI), 9th ed.; The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Semerjian, H.G.; Watters, R.L. Impact of Measurement and Standards Infrastucture on the National Economy and International Trade. Measurement 2000, 27, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, E. From the International System of Units to a Global Metrology System. In Proceedings of the XVII IMEKO World Congress Metrology in the 3rd Millennium, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 22–27 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Bangal, P.R.; Panja, S.; Sharma, S.K. Metrological Innovations for Science, Technology and Global Trade. Mapan J. Metrol. Soc. India 2023, 38, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM. Compte Rendu Des Séances de La 1re Conférence Générale Des Poids et Mesures (CGPM); The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, E.B. Report to the International Committee on Electrical Units and Standards. Available online: https://www.google.com.sg/books/edition/Report_to_the_International_Committee_on/ccRGAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Rosa, E.B.; Wolff, F.A. Work of the International Technical Committee on Electrical Units. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1912, 2, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist, R.E.; Cage, M.E.; Tang, Y.H.; Jeffery, A.M.; Kinard, J.; Dziuba, R.F.; Oldham, N.M.; Williams, E.R. The Ampere and Electrical Standards. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2001, 106, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM. Compte Rendu Des Séances de La 7th Conférence Générale Des Poids et Mesures (CGPM); The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- CIPM. Mutual Recognition of National Measurement Standards and of Calibration and Measurement Certificates Issued by National Metrology Institutes (CIPM MRA); The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn, O.; Olson, D.A.; Kuanbayev, C.; Henson, A. The CIPM MRA—Success and Performance. Metrologia 2023, 60, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, A. The CIPM MRA: Past, Present and Future. Rev. Esp. Metrol. 2015, 24. Available online: https://www.e-medida.es/numero-8/the-cipm-mra-past-present-and-future/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Krietsch, A.; Werhahn, O. CIPM MRA Support for Hydrogen Metrology—A Case Study. Measurement 2024, 235, 115041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitz, W.; Hetherington, P. The CIPM MRA in Its 3rd Year of Implementation in Europe. In Proceedings of the CPEM Digest (Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 16–21 June 2002; pp. 270–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T. World-Wide Recognition of National Measurement Standards: Ten Years of the CIPM MRA: Recalibration. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2010, 13, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APMP. APMP Guideline for Using Hybrid Comparisons as CMC Evidence. Available online: https://www.apmpweb.org/upload/portal/20231205/44023c95738e28e3f93e9a394feb8327.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- JCGM 100:2008; Evaluation of Measurement Data—Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2008.

- JCGM GUM-1:2023; Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement—Part 1: Introduction. The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2023.

- JCGM 106:2012; Evaluation of Measurement Data-The Role of Measurement Uncertainty in Conformity Assessment. The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2012.

- Bich, W.; Cox, M.; Michotte, C. Towards a New GUM—An Update. Metrologia 2016, 53, S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bich, W.; Cox, M.G.; Dybkaer, R.; Elster, C.; Estler, W.T.; Hibbert, B.; Imai, H.; Kool, W.; Michotte, C.; Nielsen, L.; et al. Revision of the ‘Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement’. Metrologia 2012, 49, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.A.; Tang, Y.H. Evaluating the Uncertainty of Josephson Voltage Standards. Metrologia 1999, 36, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Lu, Y.L. Error Analysis and Uncertainty Estimation for a Millimeter-Wave Phase-Shift Measurement System at 325 GHz. Measurement 2015, 59, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haloua, F.; Foulon, E.; Allard, A.; Hay, B.; Filtz, J.R. Traceable Measurement and Uncertainty Analysis of the Gross Calorific Value of Methane Determined by Isoperibolic Calorimetry. Metrologia 2015, 52, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquelin, L.; Le Brusquet, L.; Fischer, N.; Gensdarmes, F.; Motzkus, C.; Mace, T.; Fleury, G. Uncertainty Propagation Using the Monte Carlo Method in the Measurement of Airborne Particle Size Distribution with a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 055801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Horender, S.; Tancev, G.; Vasilatou, K. Evaluation of Aerosol-Spectrometer Based PM2.5 and PM10 Mass Concentration Measurement Using Ambient-like Model Aerosols in the Laboratory. Measurement 2022, 201, 111761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegwarth, J.D. Estimated Uncertainty of Calibrations of Freestanding Prismatic Liquefied Natural Gas Cargo Tanks; NBSIR 81-1655; National Bureau of Standards: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Siegwarth, J.D. Volume Uncertainty of a Large Tank Calibrated by Photogrammetry. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1984, 50, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; Lewis, M. Uncertainty Analysis of the NIST Nitrogen Flow Facility. NIST Tech. Note 1994, 1364. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/calibrations/tn1364.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- van der Beek, M.; Lucas, P.; Kerkhof, O.; Mirzaei, M.; Blom, G. Results of the Evaluation and Preliminary Validation of a Primary LNG Mass Flow Standard. Metrologia 2014, 51, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Martens, H.J. Investigations into the Uncertainties of Interferometric Measurements of Linear and Circular Vibrations. Shock. Vib. 1997, 4, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, F.R.; Possolo, A. Calibration and Uncertainty Assessment for Certified Reference Gas Mixtures. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, M.J.T.; Vargha, G.M.; Brown, A.S. Gravimetric Methods for the Preparation of Standard Gas Mixtures. Metrologia 2011, 48, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schley, P.; Beck, M.; Uhrig, M.; Sarge, S.M.; Rauch, J.; Haloua, F.; Filtz, J.R.; Hay, B.; Yakoubi, M.; Escande, J.; et al. Measurements of the Calorific Value of Methane with the New GERG Reference Calorimeter. Int. J. Thermophys. 2010, 31, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Chua, S.W.; Lu, Y.L. Noise Floor and Dynamic Range Analysis of a Microwave Attenuation Measurement Receiver from 50 MHz to 26.5 GHz. Measurement 2011, 44, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y. Accurate Measurement of Millimeter-Wave Attenuation from 75 GHz to 110 GHz Using a Dual-Channel Heterodyne Receiver. Measurement 2012, 45, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Pavlyuchenko, E.; Hmima, A.; Cholley, N.; Zarubin, M.; Galliou, S.; Chembo, Y.K.; Larger, L. Estimation of the Uncertainty for a Phase Noise Optoelectronic Metrology System. Phys. Scr. 2012, T149, 14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Kenbar, A. Investigation of Measurement Uncertainties in LNG Density and Energy for Custody Transfer. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 45005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Wu, T.Y. Uncertainty Analysis for a Phase-Detector Based Phase Noise Measurement System. Measurement 2016, 85, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Pavlyuchenko, E. Uncertainty Evaluation on a 10.52 Ghz (5 Dbm) Optoelectronic Oscillator Phase Noise Performance. Micromachines 2021, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Kenbar, A.; Pruysen, A. LNG Mass Flowrate Measurement Using Coriolis Flowmeters: Analysis of the Measurement Uncertainties. Measurement 2021, 177, 109258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Kenbar, A. LNG Mass Flow Measurement Uncertainty Reduction Using Calculated Young’s Modulus and Poisson’s Ratio for Coriolis Flowmeters. Measurement 2022, 188, 110413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G.; Eiø, C.; Mana, G.; Pennecchi, F. The Generalized Weighted Mean of Correlated Quantities. Metrologia 2006, 43, S268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G. The Evaluation of Key Comparison Data. Metrologia 2002, 39, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G.; Harris, P.M. The Evaluation of Key Comparison Data Using Key Comparison Reference Curves. Metrologia 2012, 49, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G. The Evaluation of Key Comparison Data: Determining the Largest Consistent Subset. Metrologia 2007, 44, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Shirono, K. Analysis of a Regional Metrology Organization Key Comparison: Model-Based Unilateral Degrees of Equivalence. Metrologia 2023, 60, 055014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, M.J.T.; Cox, M.G. Evaluating Degrees of Equivalence Using “exclusive” Statistics. Metrologia 2003, 40, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.G.; Harris, P.M. Technical Aspects of Guidelines for the Evaluation of Key Comparison Data. Meas. Tech. 2004, 47, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacker, R.; Datla, R.; Parr, A. Combined Result and Associated Uncertainty from Interlaboratory Evaluations Based on the ISO Guide. Metrologia 2002, 39, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacker, R.N.; Datla, R.U.; Parr, A.C. Statistical Analysis of CIPM Key Comparisons Based on the ISO Guide. Metrologia 2004, 41, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacker, R.N.; Datla, R.U.; Parr, A.C. Statistical Interpretation of Key Comparison Reference Value and Degrees of Equivalence. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2003, 108, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willink, R. Forming a Comparison Reference Value from Different Distributions of Belief. Metrologia 2005, 43, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepke, A.; Lafarge, T.; Possolo, A.; Toman, B. Consensus Building for Interlaboratory Studies, Key Comparisons, and Meta-Analysis. Metrologia 2017, 54, S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.H. Dark Uncertainty in Key Comparisons in the Gas Analysis Area. Metrologia 2023, 60, 064002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecelski, C.E.; Toman, B.; Liu, F.H.; Meija, J.; Possolo, A. Errors-in-Variables Calibration with Dark Uncertainty. Metrologia 2022, 59, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randa, J. Proposal for KCRV & Degree of Equivalence for GTRF Key Comparisons. In Document of the CCEM Working Group on Radiofrequency Quantities, GT-RF/2000-12; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CCQM. CCQM Guidance Note: Estimation of a Concensus KCRV and Associated Degrees of Equivalence; The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, C.M. Analysis and Linking of International Measurement Comparisons. Metrologia 2004, 41, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, C.; Chunovkina, A.G.; Wöger, W. Linking of a RMO Key Comparison to a Related CIPM Key Comparison Using the Degrees of Equivalence of the Linking Laboratories. Metrologia 2010, 47, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, C.; Link, A.; Wöger, W. Proposal for Linking the Results of CIPM and RMO Key Comparisons. Metrologia 2003, 40, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, F.; Witt, T.J. Linking the Results of 10 PF Capacitance Key Comparisons CCEM-K4 and Euromet 345. In Proceedings of the CPEM Digest (Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 16–21 June 2002; pp. 526–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E.; Wright, J. Evaluation of Inter-Laboratory Comparison Results: Representative Examples. Measurement 2023, 223, 113723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIPM MRA-D-05; CIPM Measurement Comparisons in the CIPM MRA. The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2016.

- Shang, X.; Naftaly, M.; Skinner, J.; Ausden, L.; Gregory, A.; Ridler, N.M.; Arz, U.; Phung, G.N.; Ulm, D.; Kleine-Ostmann, T.; et al. Interlaboratory Comparison of Dielectric Measurements from Microwave to Terahertz Frequencies Using VNA-Based and Optical-Based Methods. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Technol. 2024, 72, 6473–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, F.; Phung, G.N.; Arz, U. An Interlaboratory Comparison of On-Wafer S-Parameter Measurements up to 1.1 THz. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celep, M.; Stokes, D.; Danacı, E.; Ziadé, F.; Zagrajek, P.; Wojciechowski, M.; Phung, G.N.; Kuhlmann, K.; Kazemipour, A.; Durant, S.; et al. Interlaboratory Comparison of Power Measurements at Millimetre- and Sub-Millimetre-Wave Frequencies. Metrology 2024, 4, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matus, M.; Margolis, H.S.; Seppä, J.; Karlsson, H.; Hanquist, C.-H.; Lancaster, A.J.; Lewis, A.J.; Brawer, M.; Pérez, M.d.M.; Bisi, M.; et al. The CCL-K11 Ongoing Key Comparison. Final Report for 2023. Metrologia 2024, 61, 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alink, A. First Key Comparison of Primary Standard Gas Mixtures. Metrologia 2000, 37, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy-Klein, A.; Benkler, E.; Blondé, P.; Bongs, K.; Cantin, E.; Chardonnet, C.; Denker, H.; Dörscher, S.; Feng, C.-H.; Gaudron, J.-O.; et al. International Comparison of Optical Frequencies with Transportable Optical Lattice Clocks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.22973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, T.; Rigosi, A.F.; Kruskopf, M.; Wu, B.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Yang, Y.; Elmquist, R.E.; Kaneko, N.H.; Jarrett, D.G. Comparison between NIST Graphene and AIST GaAs Quantized Hall Devices. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 3103–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viliesid, M.; Colin, C.; Dube, P. Calibration of Gauge Blocks by Optical Interferometry Comparison—Final Report. Metrologia 2022, 59, 04005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, N.; Chang, K.H.; Fujii, K.; Lee, Y.J. International Comparison of Volume Measurement for a 1 kg Silicon Sphere between KRISS and NMIJ. Measurement 2014, 49, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S.; Quincey, P.; Ebert, V.; Nowak, A.; Tompkins, J.T.; Hessey, I.; Ciupek, K.; Schaefer, C.; Werhahn, O.; Vasilatou, K.; et al. International Comparison CCQM-K150: Particle Number Concentration (100 to 20,000 cm−3) and Particle Charge Concentration (0.15 to 3 fC cm−3). Metrologia 2023, 60, 08014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilatou, K.; Dirscherl, K.; Iida, K.; Sakurai, H.; Horender, S.; Auderset, K. Calibration of Optical Particle Counters: First Comprehensive Inter-Comparison for Particle Sizes up to 5 µm and Number Concentrations up to 2 cm−3. Metrologia 2020, 57, 25005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Murashima, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Iida, K. A Bilateral Comparison of Particle Number Concentration Standards via Calibration of an Optical Particle Counter for Number Concentration up to ∼1000 cm−3. Measurement 2022, 189, 110446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, R.; Bonková, I.; Capogni, M.; Carconi, P.; Cassette, P.; Coulon, R.; Courte, S.; De Felice, P.; Dziel, T.; Fazio, A.; et al. The CCRI(II)-K2.Fe-55.2019 Key Comparison of Activity Concentration Measurements of a 55Fe Solution. Metrologia 2021, 58, 06010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vykydal, Z.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Pereira, W.W.; da Fonseca, E.S.; Thiam, C.; Hui, Z.; Dewey, M.S.; Mumm, H.P.; Harano, H.; et al. International Comparison of Measurements of Neutron Source Emission Rate (2016–2021)—CCRI(III)-K9.Cf.2016. Metrologia 2024, 61, 06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colín, C.; Viliesid, M.; Chaudhary, K.P.; Decker, J.; Dvorácek, F.; Franca, R.; Ilieff, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Stoup, J. Final Report on SIM Regional Key Comparison SIM.L-K1.2007: Calibration of Gauge Blocks by Optical Interferometry. Metrologia 2012, 49, 04010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM Comparison of Optical Frequency and Wavelength Standards, CCL-K11. Available online: https://www.bipm.org/kcdb/comparison?id=978 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Thalmann, R. CCL Key Comparison: Calibration of Gauge Blocks by Interferometry. Metrologia 2002, 39, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Conceição, P.; Fang, H.; Bielsa, F.; Kiss, A.; Nielsen, L.; Kim, D.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.C.; Lee, S.; et al. Report on the CCM Key Comparison of Kilogram Realizations CCM.M-K8.2019. Metrologia 2020, 57, 07030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Conceição, P.; Fang, H.; Bielsa, F.; Kiss, A.; Nielsen, L.; Beaudoux, F.; Espel, P.; Thomas, M.; Ziane, D.; et al. Final Report on the CCM Key Comparison of Kilogram Realizations CCM.M-K8.2021. Metrologia 2023, 60, 07003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solve, S.; Stock, M. BIPM Direct On-Site Josephson Voltage Standard Comparisons: 20 Years of Results. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solve, S.; Chayramy, R.; Stock, M.; Immonen, P.; Nissilä, J.; Manninen, A. Comparison of the Josephson Voltage Standards of the MIKES and the BIPM. Metrologia 2021, 58, 01007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, A.; Dedyulin, S.; Levesque, M.; Del Campo, D.; Izquierdo, B.C.G.; Gomez, M.E.; Quelhas, K.N.; Neto, M.A.P.; Lozano, B.M.; Eusebio, L.; et al. CCT-K7.2021: CIPM Key Comparison of Water-Triple-Point Cells. Metrologia 2023, 60, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Solve, S.; del Campo, D.; Chimenti, V.; Méndez-Lango, E.; Liedberg, H.; Steur, P.P.M.; Marcarino, P.; Dematteis, R.; Filipe, E.; et al. Final Report on CCT-K7: Key Comparison of Water Triple Point Cells. Metrologia 2006, 43, 03001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlevnoy, B.B.; Solodilov, M.V.; Kolesnikova, S.S.; Otryaskin, D.A.; Pons, A.; Campos, J.; Shin, D.J.; Park, S.; Obein, G.; Valin, M.H.; et al. CIPM Key Comparison CCPR-K1.a.2017 for Spectral Irradiance 250 nm to 2500 nm. Final Report. Metrologia 2023, 60, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolliams, E.R.; Fox, N.P.; Cox, M.G.; Harris, P.M.; Harrison, N.J. Final Report on CCPR K1-a: Spectral Irradiance from 250 nm to 2500 nm. Metrologia 2006, 43, 02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Figueroa, S.; Nielsen, L.; Rasmussen, K.; Matzumoto, A.E.P.; Razo, J.N.R. Final Report on the Key Comparison CCAUV.A-K4. Metrologia 2010, 47, 09003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.H.; Heine, H.J.; Brinkmann, F.N.C.; Ziel, P.R.; De Leer, E.W.B.; Zhen, W.L.; Kato, K.; Konopelko, L.A.; Popova, T.A.; Alexandrov, Y.I.; et al. International Comparison CCQM-K16: Composition of Natural Gas Types IV and V. Metrologia 2005, 42, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.H.; Chander, H.; Ziel, P.R.; de Leer, E.W.B.; Smeulders, D.; Besley, L.; da Cunha, V.S.; Zhou, Z.; Qiao, H.; Heine, H.-J.; et al. International Comparison CCQM K23b: Natural Gas Type II. Metrologia 2010, 47, 08013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.H.; Ziel, P.R.; de Leer, E.W.B.; Smeulders, D.; Besley, L.; da Cunha, V.S.; Zhou, Z.; Qiao, H.; Heine, H.-J.; Tichy, J.; et al. Final Report on International Comparison CCQM K23ac: Natural Gas Types I and III. Metrologia 2007, 44, 08001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alink, A.; Milton, M.; Guenther, F.; de Leer, E.; Heine, H.; Marschal, A.; Suk Heo, G.; Takahashi, C.; Wang, L.; Kustikov, Y.; et al. Final Report of Key Comparison CCQM-K1; Technical report; Nederlands Meetinstituut, Van Swinden Laboratory: Delft, The Netherlands, 1999; Corrected version, September 2001; Available online: https://www.bipm.org/documents/20126/44595999/CCQM-K1.pdf/f8a8b735-2530-5bf3-1cfa-d924475e52dd?version=1.3&t=1643120279736 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- van der Veen, A.M.H.; Zalewska, E.T.; Kipphardt, H.; Beelen, R.R.; Tuma, D.; Maiwald, M.; Füko, J.; Büki, T.; Szilágyi, Z.N.; Beránek, J.; et al. International Comparison CCQM-K118 Natural Gas. Metrologia 2022, 59, 08017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIPM. Quality Management Systems in the CIPM MRA: Guidelines for Monitoring and Reporting, MRA-G-12; The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, G.; Ansari, M.A.; Aswal, D.K. Quality Management System at NPLI: Transition of ISO/IEC 17025 From 2005 to 2017 and Implementation of ISO 17034: 2016. Mapan J. Metrol. Soc. India 2021, 36, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Al-Bashrawi, S.A. Quality Infrastructure: Metrology, Accreditation, and Standards. In Handbook of Quality System, Accreditation and Conformity Assessment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 753–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, H.S.; De Souza, T.L. Metrology Infrastructure for Sustainable Development of the Americas: The Role of SIM. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2009, 14, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Lefebvre, F.; Barillet, R.; Čermak, J.; Schaefer, W.; Cibiel, G.; Sauvage, G.; Franquet, O.; Llopis, O.; Meyer, F.; et al. Phase Noise Inter-Laboratory Comparison Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the 20th European Frequency and Time Forum, EFTF 2006, Braunschweig, Germany, 27–30 March 2006; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Patan Alper, M. Inter-Laboratory Comparison of a Digital Multimeter Measurement in Turkey. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuichi, N.; Terao, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Cordova, L.; Shimada, T. Inter-Laboratory Comparison of Small Water Flow Calibration Facilities with Extremely Low Uncertainty. Measurement 2016, 91, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.K.; Biswas, J.C.; Yadav, A.S. Proficiency Testing in AC Power and Energy. Mapan J. Metrol. Soc. India 2009, 24, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.V.; Dias, M.H.C.; Dos Santos, J.C.A. Proficiency Testing of Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC) Labs in Brazil by Measurement Comparisons. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 115107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Prakash, O.; Gupta, V.K.; Kumaraswamy, B.V.; Bandyopadhyay, A.K. Evaluation of Interlaboratory Performance through Proficiency Testing Using Pressure Dial Gauge in the Hydraulic Pressure Measurement up to 70 MPa. Mapan J. Metrol. Soc. India 2008, 23, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Salzenstein, P. Rapport de Comparaison Internationale Interlaboratoire N° EM 03-99 (Haute Fréquence—Facteur de Réflexion). In Comité Français d’accréditation (COFRAC) Report; COFRAC: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ILAC B7:10/2015; ILAC The ILAC Mutual Recognition Arrangement. International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation: Newton, Australia, 2015.

- Salsbury, J. Uncertainty Management versus Risk Management in Calibration. NCSLI Meas. 2010, 5, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbert, M. A Guard-Band Strategy for Managing False-Accept Risk. NCSLI Meas. 2008, 3, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. Estimation and Evaluation of Measurement Decision Risk. In NASA Measurement Quality Assurance Handbook; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- ILAC-G8:09; ILAC Guidelines on Decision Rules and Statements of Conformity. International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation: Newton, Australia, 2019.

- Casacio, C.A.; Madsen, L.S.; Terrasson, A.; Waleed, M.; Barnscheidt, K.; Hage, B.; Taylor, M.A.; Bowen, W.P. Quantum-Enhanced Nonlinear Microscopy. Nature 2021, 594, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; Maccone, L. Quantum-Enhanced Measurements: Beating the Standard Quantum Limit. Science 2004, 306, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.B. Squeezing-Induced Quantum-Enhanced Multiphase Estimation. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 033292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, F.; Liu, X.; Yakovlev, V.V.; Agarwal, G.S. Quantum-Enhanced Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Spectroscopy and Imaging. Optica 2022, 9, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, M.; Yu, H.; Kijbunchoo, N.; Fernandez-Galiana, A.; Dupej, P.; Barsotti, L.; Blair, C.D.; Brown, D.D.; Dwyer, S.E.; Effler, A.; et al. Quantum-Enhanced Advanced LIGO Detectors in the Era of Gravitational-Wave Astronomy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 231107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Apellaniz, I. Quantum Metrology from a Quantum Information Science Perspective. J. Phys. A Math. 2014, 47, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.; Guo, G. Quantum Metrology. Chin. Phys. B 2013, 22, 110601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, C.L.; Reinhard, F.; Cappellaro, P. Quantum Sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; MacCone, L. Advances in Quantum Metrology. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzyna, M.; Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. True Precision Limits in Quantum Metrology. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, M. Caves Quantum Mechanical Radiation-Pressure Fluctuations in an Interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Dolde, J.; Lochab, V.; Merriman, B.N.; Li, H.; Kolkowitz, S. Differential Clock Comparisons with a Multiplexed Optical Lattice Clock. Nature 2022, 602, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, A.D.; Zelevinsky, T.; Campbell, G.K.; Blatt, S.; Boyd, M.M.; De Miranda, M.H.G.; Martin, M.J.; Thomsen, J.W.; Foreman, S.M.; Ye, J.; et al. Sr Lattice Clock at 1 × 10–16 Fractional Uncertainty by Remote Optical Evaluation with a Ca Clock. Science 2008, 319, 1805–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenband, T.; Hume, D.B.; Schmidt, P.O.; Chou, C.W.; Brusch, A.; Lorini, L.; Oskay, W.H.; Drullinger, R.E.; Fortier, T.M.; Stalnaker, J.E.; et al. Frequency Ratio of Al+ and Hg+ Single-Ion Optical Clocks; Metrology at the 17th Decimal Place. Science 2008, 319, 1808–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloy, K.; Bodine, M.I.; Bothwell, T.; Brewer, S.M.; Bromley, S.L.; Chen, J.S.; Deschênes, J.D.; Diddams, S.A.; Fasano, R.J.; Fortier, T.M.; et al. Frequency Ratio Measurements at 18-Digit Accuracy Using an Optical Clock Network. Nature 2021, 591, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, S.M.; Chen, J.S.; Hankin, A.M.; Clements, E.R.; Chou, C.W.; Wineland, D.J.; Hume, D.B.; Leibrandt, D.R. Al+ 27 Quantum-Logic Clock with a Systematic Uncertainty below 10–18. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 033201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.M.; Miklos, M.; Tso, Y.M.; Kennedy, C.J.; Bothwell, T.; Kedar, D.; Thompson, J.K.; Ye, J. Direct Comparison of Two Spin-Squeezed Optical Clock Ensembles at the 10–17 Level. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yoon, T.H.; Hall, J.L.; Madej, A.A.; Bernard, J.E.; Siemsen, K.J.; Marmet, L.; Chartier, J.M.; Chartier, A. Accuracy Comparison of Absolute Optical Frequency Measurement between Harmonic-Generation Synthesis and a Frequency-Division Femtosecond Comb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3797–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udem, T.; Holzwarth, R.; Hänsch, T.W. Optical Frequency Metrology. Nature 2002, 416, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Cedergren, K.; Shetty, N.; Lara-Avila, S.; Kubatkin, S.; Bergsten, T.; Eklund, G. Accurate Graphene Quantum Hall Arrays for the New International System of Units. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafont, F.; Ribeiro-Palau, R.; Kazazis, D.; Michon, A.; Couturaud, O.; Consejo, C.; Chassagne, T.; Zielinski, M.; Portail, M.; Jouault, B.; et al. Quantum Hall Resistance Standards from Graphene Grown by Chemical Vapour Deposition on Silicon Carbide. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Kruskopf, M.; Gournay, P.; Rolland, B.; Götz, M.; Pesel, E.; Tschirner, T.; Momeni, D.; Chatterjee, A.; Hohls, F.; et al. Graphene Quantum Hall Resistance Standard for Realizing the Unit of Electrical Resistance under Relaxed Experimental Conditions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2025, 23, 014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbers, A.J.M.; Rietveld, G.; Houtzager, E.; Zeitler, U.; Yang, R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Maan, J.C. Quantum Resistance Metrology in Graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 222109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopfer, F.; Poirier, W. Graphene-Based Quantum Hall Effect Metrology. MRS Bull. 2012, 37, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. NIST Broadens Collaboration with BIPM to Enhance Voltage Standards. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2024/10/nist-broadens-collaboration-bipm-enhance-voltage-standards (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- BIPM New Pilot Study Enhances Accuracy of AC Voltage Comparisons. Available online: https://www.bipm.org/en/-/2024-10-24-pilot-study-ac-voltage (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Fujii, K.; Massa, E.; Bettin, H.; Kuramoto, N.; Mana, G. Avogadro Constant Measurements Using Enriched 28Si Monocrystals. Metrologia 2018, 55, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, G.; Becker, P.; Beckhoff, B.; Bettin, H.; Beyer, E.; Borys, M.; Busch, I.; Cibik, L.; D’Agostino, G.; Darlatt, E.; et al. A New 28Si Single Crystal: Counting the Atoms for the New Kilogram Definition. Metrologia 2017, 54, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppers, D.; Knopf, D.; Nicolaus, A.; Kuhn, E.; Borys, M.; Müller, M.; Bettin, H. Status of the Kilogram Realisation Using the XRCD Method at PTB. Meas. Sens. 2025, 38, 101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppers, D.; Müller, M.; Kuhn, E.; Borys, M.; Rodiek, B.; Knopf, D.; Schrader, T. Realisation of the Kilogram with the XRCD Method—Improved XRF Evaluation and Its Impact. Metrologia 2025, 62, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, N.; Mizushima, S.; Zhang, L.; Fujita, K.; Okubo, S.; Inaba, H.; Azuma, Y.; Kurokawa, A.; Ota, Y.; Fujii, K. Reproducibility of the Realization of the Kilogram Based on the Planck Constant by the XRCD Method at NMIJ. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1005609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Bettin, H.; Becker, P.; Massa, E.; Rienitz, O.; Pramann, A.; Nicolaus, A.; Kuramoto, N.; Busch, I.; Borys, M. Realization of the Kilogram by the XRCD Method. Metrologia 2016, 53, A19–A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.A.; Schlamminger, S. The Watt or Kibble Balance: A Technique for Implementing the New SI Definition of the Unit of Mass. Metrologia 2016, 53, A46–A74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Bielsa, F.; Li, S.; Kiss, A.; Stock, M. The BIPM Kibble Balance for Realizing the Kilogram Definition. Metrologia 2020, 57, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M. The Watt Balance: Determination of the Planck Constant and Redefinition of the Kilogram. In Proceedings of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences; The Royal Society Publishing: London, UK, 2011; Volume 369, pp. 3936–3953. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, J.; Rothleitner, C.; Vasilyan, S.; Rogge, N.; Behr, R.; Götz, M.; Kruskopf, M.; Fröhlich, T. Small Mass Value Realization Equivalent to Accuracy Class E1 Using the Planck-Balance at PTB. Metrologia 2025, 62, 025014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Seifert, F.; Haddad, D.; Pratt, J.; Newell, D.; Schlamminger, S. The Performance of the KIBB-G1 Tabletop Kibble Balance at NIST. Metrologia 2020, 57, 035014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, L.; Seifert, F.; Newell, D.; Schlamminger, S.; Theska, R.; Haddad, D. Design of an Enhanced Mechanism for a New Kibble Balance Directly Traceable to the Quantum SI. EPJ Technol. Instrum. 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.A. Watt and Joule Balances. Metrologia 2014, 51, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzocaro, M.; Sekido, M.; Takefuji, K.; Ujihara, H.; Hachisu, H.; Nemitz, N.; Tsutsumi, M.; Kondo, T.; Kawai, E.; Ichikawa, R.; et al. Intercontinental Comparison of Optical Atomic Clocks through Very Long Baseline Interferometry. Nat. Phys. 2021, 17, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblin, S.P.; Yamahata, G.; Fujiwara, A.; Kataoka, M. Precision Measurement of an Electron Pump at 2 GHz; the Frontier of Small DC Current Metrology. Metrologia 2023, 60, 055001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Davis, R.; De Mirandés, E.; Milton, M.J.T. The Revision of the SI—The Result of Three Decades of Progress in Metrology. Metrologia 2019, 56, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, G.; Zheng, X.; Michieletti, F.; Leonetti, G.; Caballero, G.; Oztoprak, I.; Boarino, L.; Bozat, Ö.; Callegaro, L.; De Leo, N.; et al. A Quantum Resistance Memristor for an Intrinsically Traceable International System of Units Standard. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehle, F.; Gill, P.; Arias, F.; Robertsson, L. The CIPM List of Recommended Frequency Standard Values: Guidelines and Procedures. Metrologia 2018, 55, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM. Mise En Pratique for the Definition of the Second in the SI. In SI Brochure; The Bureau International Des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall, T.; Pizzocaro, M.; Godun, R.M.; Abgrall, M.; Akamatsu, D.; Amy-Klein, A.; Benkler, E.; Bhatt, N.M.; Calonico, D.; Cantin, E.; et al. Coordinated International Comparisons between Optical Clocks Connected via Fiber and Satellite Links. Optica 2025, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, C.; Huntemann, N.; Lange, R.; Tamm, C.; Peik, E.; Safronova, M.S.; Porsev, S.G. Optical Clock Comparison for Lorentz Symmetry Testing. Nature 2019, 567, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, H.S.; Panfilo, G.; Petit, G.; Oates, C.; Ido, T.; Bize, S. The CIPM List ‘Recommended Values of Standard Frequencies’: 2021 Update. Metrologia 2024, 61, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM Vers La Redéfinition de La Seconde. Available online: https://www.bipm.org/fr/-/2024-02-20-redefinition-second (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- BIPM. SI Base Unit: Second (s). Available online: https://www.bipm.org/en/si-base-units/second (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Dimarcq, N.; Gertsvolf, M.; Mileti, G.; Bize, S.; Oates, C.W.; Peik, E.; Calonico, D.; Ido, T.; Tavella, P.; Meynadier, F.; et al. Roadmap towards the Redefinition of the Second. Metrologia 2024, 61, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblin, S.P.; Kataoka, M.; Fletcher, J.D.; See, P.; Janssen, T.J.B.M.; Griffiths, J.P.; Jones, G.A.C.; Farrer, I.; Ritchie, D.A. Towards a Quantum Representation of the Ampere Using Single Electron Pumps. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.H.; Chae, D.H.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, B.K.; Park, S.I.; Song, J.; Oe, T.; Kaneko, N.H.; Kim, N.; Kim, W.S. Precision Measurement of Single-Electron Current with Quantized Hall Array Resistance and Josephson Voltage. Metrologia 2020, 57, 065025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, H.; Camarota, B. Quantum Metrology Triangle Experiments: A Status Review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 124010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Meda, A.; Porrovecchio, G.; Starkwood (Kirkwood), R.A.; Genovese, M.; Brida, G.; Šmid, M.; Chunnilall, C.J.; Degiovanni, I.P.; Kück, S. A Study to Develop a Robust Method for Measuring the Detection Efficiency of Free-Running InGaAs/InP Single-Photon Detectors. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.J. The BIPM and the Accurate Measurement of Time. Proc. IEEE 1991, 79, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNish, A.G. Lasers for Length Measurement. Science 1964, 146, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, J.S.; Penzes, W.B. The NIST Length Scale Interferometer. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 1999, 104, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, F.L.; Barillet, R.; Besson, R.J.; Groslambert, J.; Schumacher, P.; Rufenacht, J.; Hilty, K. International Comparison of Phase Noise. In Proceedings of the 8th European Frequency and Time Forum (EFTF), Weihenstephan, Germany, 25–27 June 1994; pp. 439–456. [Google Scholar]

- Quincey, P.; Sarantaridis, D.; Yli-Ojanperä, J.; Keskinen, J.; Högström, R.; Heinonen, M.; Lüönd, F.; Nowak, A.; Riccobono, F.; Tuch, T.; et al. EURAMET Comparison 1244 Comparison of Aerosol Electrometers, Issue 2: EURAMET REPORT. In NPL REPORT AS 85; The National Physical Laboratory: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.; Nowak, A.; Tompkins, J.; Tomson, M.; Waheed, A.; Godau, D.; Jung, J.; Kim, H.; Wu, T.; Auderset, K.; et al. Ensuring the Worldwide Equivalence of Measurements of Nanoparticle Number Concentration and Charge Concentration: An International Comparison. In Proceedings of the European Aerosol Conference (EAC 2025), Lecce, Italy, 31 August–5 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.; Nowak, A.; Tipler, J.; Tompkins, J.; Tomson, M.; Waheed, A.; Godau, D.; Jung, J.; Kim, H.; Wu, T.; et al. International Comparison CCQM-K185: Particle Number Concentration 1000 to 500,000 cm−3) and Particle Charge Concentration 0.16 fC to 16 fC cm−3). Final report for International Comparison CCQM-K185, to be published in BIPM website.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salzenstein, P.; Wu, T.Y.; Pavlyuchenko, E. The Critical Role of International Comparisons in Global Metrology System: An Overview. Metrology 2025, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040074

Salzenstein P, Wu TY, Pavlyuchenko E. The Critical Role of International Comparisons in Global Metrology System: An Overview. Metrology. 2025; 5(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalzenstein, Patrice, Thomas Y. Wu, and Ekaterina Pavlyuchenko. 2025. "The Critical Role of International Comparisons in Global Metrology System: An Overview" Metrology 5, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040074

APA StyleSalzenstein, P., Wu, T. Y., & Pavlyuchenko, E. (2025). The Critical Role of International Comparisons in Global Metrology System: An Overview. Metrology, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrology5040074