Abstract

The recent resurgence of COVID-19 in a Hepatitis B virus some endemic countries could lead to adverse outcomes. In this article, we formulate and analyse a mathematical model to explains the co-infection dynamics of Hepatitis B virus and COVID-19. Our aim is to investigate the effect of Hepatitis B virus prevention, COVID-19 prevention, COVID-19 vaccination, and environmental factors on transmission dynamics, and formulate conditions for extinction and persistence of the diseases. First, we derive the basic reproduction number for HBV only, COVID-19 only, and co-infection stochastic models using the next-generation matrix method. Next, we establish the conditions for stability in the stochastic sense for HBV only, COVID-19 only sub-models, and the co-infection model using suitable Lyapunov functions. Furthermore, we devote our attention to finding sufficient conditions for extinction and persistence. Finally, motivated by Ghana data, we applied the Euler–Murayama scheme to illustrate the dynamics of the co-infection, COVID-19, HBV, and the effect of some parameters on disease transmission dynamics by means of numerical simulations.

Keywords:

COVID-19; hepatitis B; stochastic model; reproduction number; global stability; extinction 1. Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and affects the functionality of the respiratory system. It spreads from person to person via direct contact with respiratory droplets from an infected individual. It can also be spread by touching surfaces contaminated with the virus and then touching the face. Since its emergence from Wuhan, China, in December 2019, it rapidly spread to every country and has inflicted severe public health and socio-economic burden globally [1]. Over 7 million COVID-19 deaths and over 700 million infections have been reported since December 2019 [2]. Vaccination efforts have aided in reducing severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths [2] worldwide. After a fourth transmission wave, Ghana also experienced a decline in COVID-19 cases. However, in July 2025, 107 confirmed cases were reported, underscoring the potential for seasonal resurgence [3].

Hepatitis B disease is a life-threatening and infectious disease caused by the hepatitis B virus and is associated with serious liver infection, leading to liver malfunction, including cirrhosis, liver fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The virus is typically transmitted from mother to child during birth and delivery, in early childhood, as well as through contact with blood, semen, or other body fluids from an infected person [4]. Between 8 weeks and 5 months, the exposed individual can experience symptoms including fever, loss of appetite, joint pain, fatigue, and nausea [5]. Current statistics reveal that over 81 million people from the WHO African Region are chronically infected [6]. It is estimated that about 2 billion people are infected with HBV globally, with about million infections annually [7] and 0.6 million annual deaths from HBV-related liver diseases [8,9]. Countries such as Ghana continue to have a much higher (from 8.36% to 12.3%) disease prevalence rate than the global average of 3% [4] and approximately 294 HBV-related deaths weekly [10].

Both COVID-19 and Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are life-threatening diseases and remain health problems, particularly in Sub-Saharan African countries like Ghana, Botswana, and Nigeria; see, e.g., [2,4]. Despite advances in immunization, both HBV and COVID-19 continue to pose significant public health challenges [11,12].

Co-infection refers to a situation where two or more pathogens simultaneously affect a host. This typically complicate disease progression, treatment, and public health responses [13]. For example, in HIV–tuberculosis (TB) co-infection, HIV compromises the immune system, accelerating TB activation and increasing mortality rates [13]. Recently, some clinical studies have confirmed the possibility of the co-infection of COVID-19 and Hepatitis B diseases; see, e.g., [12,14,15]. HBV and COVID-19 co-infection can exacerbate disease severity, leading to adverse outcomes, including increased mortality risk [14,15]. There is, therefore, the need for techniques that better predict disease dynamics and offer recommendations for the prevention and reduction in disease co-infection spread in the presence of clinical, behavioural, and environmental factors.

To improve our understanding of the co-infection dynamics of these two global threats, mathematical models have been developed to address gaps in clinical studies and propose potential control strategies; see, e.g., [6,16,17,18,19]. In [18], the author, constructed and analysed a deterministic mathematical model that captures the co-infection dynamics of hepatitis B disease and COVID-19 and also evaluated the impact of various intervention strategies on the spread of both diseases in a population. In another study [17], a deterministic model was used to analyse the impact of optimal control strategies on the transmission of COVID-19 and HBV co-infection. Reference [6] applied the deterministic fractional-order derivative to study a co-infection model for HBV and COVID-19.

Mathematical models are essential tools that can guide effective interventions for various infectious diseases, e.g., [20,21,22,23,24]. Several deterministic models have been developed to study the transmission dynamics of other infectious diseases. Although the relevance of classical deterministic models e.g., [22,25,26,27,28] in explaining disease dynamics cannot be disputed, they often assume that epidemic paths are predictable given specified parameters. In reality, however, epidemic trajectories are rarely deterministic. They are shaped by various layers of uncertainty, including incomplete or noisy data, variability in parameter estimates, and random environmental or demographic fluctuations [29]. Ignoring such uncertainties can lead to overconfident forecasts and policy recommendations that fail under real-world conditions.

Stochastic models, e.g., [22,30,31,32], provide a more realistic representation of epidemic dynamics of disease spread. These epidemiological models, unlike classical deterministic counterparts, e.g., [20,21,23], account for the effects of random fluctuations in disease transmission dynamics and allow for the quantification of extinction probabilities and the likelihood of rare but high-impact events [29,33]. In the context of COVID-19, where co-infections with chronic diseases such as Hepatitis B remain a public health concern, accounting for uncertainty is essential for designing robust and adaptive control measures.

Further, although [6,17,18,19] made significant contributions to understanding the dynamics of COVID-19 and HBV co-infection, they did not examine the impacts of COVID-19 prevention, HBV prevention, COVID-19 vaccination, and the combined effects of standard random fluctuations and large-scale disturbances caused by environmental factors within the same framework that the present work sought to study. Further, to help explain the long-run behaviour of disease spread, refs. [34,35,36] have formulated techniques for examining the existence and persistence of solutions. However, persistence and extinction of the diseases depend on several factors, including the type of stochastic noise, thus making the formulating conditions for the persistence or extinction of stochastic models a cumbersome task [30]. As part of our aim, we formulate the conditions for extinction and persistence for the proposed stochastic co-infection model. In addition, we also investigate effective control mechanisms, which are essential for informed public health decision-making. Specifically, our study seeks to investigate the following objectives:

- To develop a compartmental model for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and HBV co-infection.

- To establish the Invariance and Positivity of the stochastic co-infection model.

- To determine the basic Reproductive number for Stochastic co-infection, COVID-19-only, and HBV-only models.

- To determine conditions for stability at Disease Free Equilibrium for stochastic co-infection models.

- To determine the conditions of extinction and persistence of the stochastic COVID-19-only, HBV-only, and co-infection models.

- To present numerical simulations of the model.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the mathematical model and the underlying assumptions. In Section 3, we analyse the COVID-19 and HBV sub-models, as well as the co-infection model. Section 4 is devoted to discussing the numerical method and numerical simulation of the model. Finally, we present the conclusion in Section 5.

2. Mathematical Model Formulation

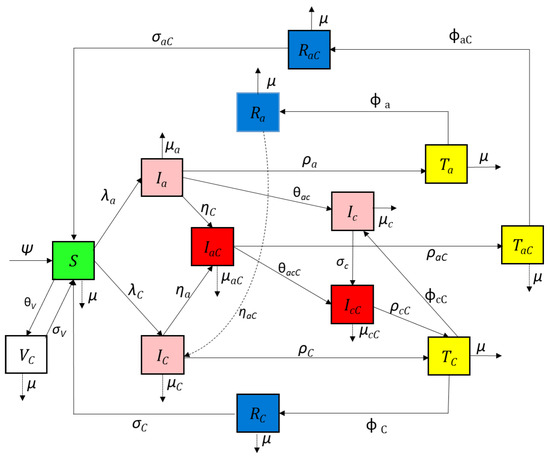

In this section, we consider a stochastic compartmental mathematical model that uses differential equations; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Compartmental diagram for the COVID-19 and Hepatitis B co-infection cohort.

2.1. Assumptions of the Model

The following assumptions are used to formulate the model:

- Recruitment into the susceptible populations is by birth and immigration.

- New human infection is through close contact with infectious humans and contaminated environments.

- There is homogeneous mixing in both sub-populations.

- COVID-19 vaccination wears off after some period of time.

- The total human population is a sum of all the different compartments, i.e.,

- There is no relapse from HBV recovery to susceptible state. HBV-recovered persons generally develop lifelong immunity and cannot be reinfected with HBV, but can be infected with COVID-19. There is, however, relapse from a COVID-19-recovered state to susceptible state.

- Individuals with chronic HBV will remain in a chronic HBV state, even if some form of medical management is administered. However, they can be infected with COVID-19.

2.2. Human Population

The model is structured into thirteen human compartments: The subpopulations of the human population at time denoted by . The sub-populations of the human population at time denoted by include susceptible individuals COVID-19-infected individuals acute hepatitis-B-infected individuals , acute hepatitis-B-infected and COVID-19-infected individuals chronic hepatitis-B-infected individuals chronic hepatitis-B- and COVID-19-infected individuals acute hepatitis-B-infected individuals receiving treatment COVID-19-infected individuals receiving treatment acute hepatitis-B and COVID-19 co-infected individuals receiving treatment acute hepatitis-B-recovered individuals COVID-19-recovered infected individuals , acute hepatitis-B- and COVID-19-recovered individuals , and COVID-19-vaccinated individuals

The model excludes HBV vaccination compartment (Figure 1). This is because we consider a typically high HBV prevalence population with low HBV vaccinated population (i.e., the Ghanaian data used in estimating infections rates are typically based on such unvaccinated population). Further, the HBV vaccine provides long-lasting immunity. This implies that such persons can only be infected by COVID-19.

2.3. Model Formulation

In this section, we consider a stochastic compartmental mathematical model that uses differential equations. Figure 1 presents the flow between states of the COVID-19 and HBV co-infection model.

We obtain the following system of non-linear differential equations from the model flow diagrams of the disease transmission shown in Figure 1:

with initial conditions , , , , , , , , , , , , .

, are the transmission rate for COVID-19 and HBV, respectively. The parameters , and are non-negative, with forces of infection of , and , respectively, and and . and are a fraction of the community employing protective or preventive measures for COVID-19 and HBV, respectively, and is the efficacy of personal protection strategy adopted. The model parameters, along with their descriptions, are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters and description.

We include stochastic terms in our model to reflect real-world sources of uncertainty in epidemic dynamics. Firstly, we include small and standard random fluctuation described by Brownian noise to account for continuous fluctuations that may arise from random interactions, environmental factors, or reporting variability. Secondly, we include Lévy-driven jumps that imprint sudden discrete changes such as super-spreader events, as outlined in [37].

In this study, it is assumed that fluctuations in the environment will manifest mainly as fluctuations in the parameter , i.e., , where is a one dimensional standard Brownian noise with and is the intensity of the noise. Details on how this was performed in the study is detailed below.

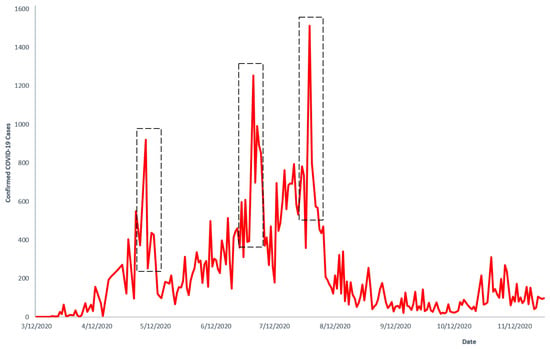

We restricted the Poisson Lévy noise to COVID-19 infectious states. A multiplicative jump noise that occurs randomly and proportional the number of infective in a finite population was assumed, e.g., [19]. Our inclusion of Poisson jumps was necessary because COVID-19 that is spread through human interactions can become highly irregular due to spreader factors. Such factors, e.g., mass gatherings at funeral ceremonies and loose enforcement of public health measures (e.g., wearing of nose masks), are mentioned in Ghanaian studies, e.g., [37], as causes of COVID-19 jumps in the distribution of disease spread. It can be observed in Figure 2 that the distribution of confirmed COVID-19 data from Ghana exhibited jumps as a result of factors outlined by [37].

Figure 2.

Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Ghana. Source of data: Manu (2020) [38].

Jumps are excluded in HBV. Only Brownian noise is included in the HBV infectious states as disease spread in real-world data for in the population considered, e.g., [39] do not exhibit the presence of jumps (i.e., infection rate remains relative smooth). Hence, accounts for continuous fluctuations in transmission.

The Poisson-driven Lévy process, thus, is divided into linear drift term, Brownian motion, and finite Lévy-driven noise. The stochastic model of the system (2) takes the following form:

with initial conditions , , , , , , , , , , , , . The standard Brownian noise, is independent of . is a Poisson counting measure with compensating martingale . Here, we define v as a finite Lévy measure on a measurable subset , where . gives the expected number of jumps whose sizes falls within in time. Again, since , every possible jump contributes to an increase and the expectation over integrates over positive values, making its integral non-negative. . We define and bounded for all , and . We also assume that thus ensuring that the measure does not allow for infinitely many jumps in a finite time interval. We note that , , , , , , , , , , , , denote the left limits of , , , , , , , , , , , , respectively.

The definitions below are necessary for the analysis of the stochastic model.

Definition 1

(Itô-Lévy [40]). First, set . Suppose a complete probability space with filtration , that satisfies the usual conditions of right-continuity and completeness. is defined on this probability space. We assume an Itô-Lévy process, , of the form

with initial condition X(t=0) = X(0). and are measurable functions and denotes the left limit of . represents the linear drift term, the Brownian noise, represents the compensated Poisson random measure, represents the intensity of jumps, u represents the type of the jump, and represents how frequently jumps of type u occur. It is assumed that (i) is finite (i.e., the number of jumps in any finite interval is countable), (ii) (iii) , where C is a constant, (iv) , and (v) [40] are satisfied.

Definition 2

(Itô-Lévy Formula [40]). We consider the process X expressed by (4) and let such that , where means that the function is continuously differentiable with respect to time, and means that the function has continuous second-order partial derivatives with respect to the remaining variables.

Then, is again an Itô-Lévy process and

represents the generalized Itô’s formula with jumps where

To gain insights into the underlying mechanisms that drive the spread of infectious diseases to identify the long-term behaviour of disease transmission, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the stochastic model (3).

3. Qualitative Analysis of Model

In this section, we present an analysis on the existence of a solution, the positivity of the solution to (3), determine the reproductive number for single-disease models and the co-infection model, and determine the conditions for Local and Global equilibrium for COVID-19-only, HBV-only, and co-infection models. Further, we determine the conditions for extinction and persistence for all three models.

3.1. Positivity of Model

Here, we determine the positivity of a solution to the stochastic system (3), since a negative state will not be biologically meaningful. Consequently, we assume strictly positive initial conditions, . To ensure that solutions remain in the admissible domain, the drift and diffusion coefficients are taken to be smooth in the interior of and to vanish on the boundary [41].

We proceed as follows:

Theorem 1.

Let , , , , denote the left limits of , , be a solution of system (3), given initial values , where , then ,

Proof.

where (by quadratic variation of Brownian motion). A rearrangement yields

Combining (7) and (8), integrating both sides and rearrangements gives

We determine the positivity of the stochastic system (3). We proceed to show the positivity of the solution to (3) as follows. We consider the first equation of (3),

Eliminating first four positive terms on the right hand side and rearranging terms, we get

where , and . Next, we take a function and apply Itô-Lévy formula to (5) to get

Since , where C is a positive constant, we have

By taking the on both sides we obtain

It is clear that as , S(t) is positive definite.

Next, we show the positivity of the solution to (3) as follows. We consider the acute HBV infectious class of (3)

By eliminating first positive term on the right hand side and rearranging terms, we get

where . Next, we take a function and apply Itô’s formula to (6) to get

We can show using similar approach that, ,, □

3.2. Invariant Region of Stochastic COVID-19 and Hepatitis B Co-Infection Model

An investigation of the invariant region will ensure that the population sizes remain non-negative and bounded.

Theorem 2.

Let be the population of system (3), then is invariant over time, that is , and

Proof.

From (1), we know that

By differentiating (1), we obtain

Substituting the derivatives and simplifying terms in (3), we obtain

We let and choose and to obtain

with (10) satisfies the Itô–Lévy process. By rearrangement of (10), we obtain a non-homogeneous differential equation. Next, we determine the homogeneous and particular solution and obtain the general solution to Equation (10) as

Since and , by taking the limit superior, we obtain the solution to (10) as

□

3.3. Disease Free Equilibrium Point

We consider the first equation of (3). For disease free equilibrium, we have We let

Next, we solve for as

We find the expectation to get

The above result is obtained by applying Definition 1 and comparison [30]. Hence, the disease free equilibrium is given by

3.4. Reproductive Number for COVID-19 Only Model

The reproduction number, , of a disease determines the average number of secondary infections when an infectious person is introduced into in a completely susceptible population. It is, therefore, an important parameter in disease control. In this section, we present results on the reproductive number for the deterministic COVID-19 model, and the reproductive number for the COVID-19 model in the stochastic sense, . Next, we determine stability conditions for and , respectively.

3.4.1. Basic Reproductive Number of Deterministic COVID-19 Only Model

To obtain the basic reproduction number, we consider the infected class of COVID-19 deterministic model given by

with initial conditions , , , , . We employ the Next Generation Matrix (NGM) method, e.g., [42], to determine the basic reproductive number of the deterministic model. When using the NGM method, the basic reproductive number is defined as the spectra radius (largest eigenvalue) of , where F and V are the partial derivatives of f and v, respectively.

We consider the infectious class of model (12). Let f be the rate of new infection and let v be the rate of transfer of new infection into and out of the compartment. Then

Finding the partial derivative of f and v with respect to , we obtain the Jacobian matrices F and V

Evaluating F and V at DFE, we obtain

and Multiplying F and , we get

Taking the spectral radius of i.e., we obtain the deterministic reproductive number of COVID-19 only transmission as

represents the expected number of secondary infections generated by a single COVID-19 primary infection introduced into a fully susceptible population, and represents the expected time an individual will spend in the COVID-19 infectious compartment.

3.4.2. Basic Reproductive Number of Stochastic COVID-19 Only Model

To obtain the basic reproduction number, the COVID-19 infected class of (3) was considered.

We set a function apply the Itô–Lévy formula, and evaluate at DFE to get

Considering partial derivatives of initial infections F and secondary infections V, we determine the basic reproduction number by means of the next generation matrix [42] as follows

and

By multiplying F and and factorising , we obtain

Taking the spectral radius of i.e., we obtain

Next, we examine the local stability of the at DFE.

3.4.3. Local Stability of Stochastic COVID-19 Only Model

It is crucial to understand the behaviour of a dynamical system near the disease-free equilibrium point. Checking for local stability at DFE point helps to determine whether COVID-19 will eventually die out and if the disease-free equilibrium is locally stable.

Theorem 3.

If , then for any initial values of , satisfies

Proof.

We recall (15), the Itô–Lévy expression for the COVID-19-infected class of (3).

By integrating both sides of (17) and evaluating at the disease free-equilibrium point, we have

where and are martingales given ,

Next, we divide through by t, take of both sides, and apply Lemma 1 to get

For

since

We conclude that, whenever , □

3.4.4. Global Stability of Stochastic COVID-19 Only Model

Theorem 4.

If , then is globally asymptotically stable in

3.5. Basic Reproductive Number for HBV Only Model

In this section, we first present results on the reproductive number for the deterministic reproductive number of the HBV-only model, and the reproductive number of the HBV-only model in the stochastic sense . Next, we determine stability conditions for and , respectively.

3.5.1. Basic Reproductive Number of Deterministic HBV Only Model

To obtain the basic reproduction number, we consider the infected class of HBV deterministic model given by

with initial conditions , , , , .

We employ the next-generation matrix [42] method described earlier to determine the basic reproductive number of the deterministic model. We proceed by considering the primary or initial infections f and secondary infections v of (12):

Finding the partial derivative of f and v with respect to and evaluating at DFE gives

and

The inverse of V is obtained as

Multiplying F and , we get

Taking the spectral radius of i.e., we obtain

Next, we determine the reproduction number of the HBV stochastic model.

3.5.2. Basic Reproductive Number for Stochastic HBV Only Model

We consider the acute HBV infectious state of the HBV-only stochastic sub-model:

Next, we take a function . Applying the Itô–Lévy formula to the HBV infected class of (27), we obtain

Next, we employ the next-generation matrix [42] technique to determine the basic reproductive number of the deterministic model. The partial derivatives with respect to of the initial infections F and of secondary infections V are obtained and evaluated at DFE as follows:

and

By multiplying F and , we get

Taking the spectral radius of i.e., we obtain

3.5.3. Local Stability of Stochastic HBV Only Model

Checking for local stability at DFE point helps us to determine whether the HBV will eventually die out and the disease-free equilibrium is locally stable.

Theorem 5.

If , then for any initial values of , satisfies

3.5.4. Global Stability of HBV Only Model

Theorem 6.

If , then is globally asymptotically stable in

3.6. Reproductive Number of Co-Infection Model

In this section, we present results on the reproductive number for the deterministic co-infection model, and the reproductive number for the co-infection model in the stochastic sense . Next, we determine stability conditions for and , respectively.

3.6.1. Reproductive Number of Deterministic Co-Infection Model

In this section, we employ the next-generation matrix [42] method to determine the basic reproductive number of the deterministic co-infection model. As explained earlier, the NGM method for determining the basic reproductive number requires that we first find the matrix of new infections, and the matrix of secondary infections, respectively. We consider disease infectious states of (2), and we have

with initial conditions , , , , , and represent new infections. and represent progression to co-infection. We determine f, representing new infections from the susceptible compartment, and v, the rates of transition from one compartment to the other. These are represented as

and

Using the NGM method, we seek to determine the basic reproductive number (the spectra radius of the We obtain the Jacobian matrices F and V, respectively, as

Next, we determine , where is computed as

Multiplying F and and evaluating at DFE to gives

where

are the basic reproduction numbers for the deterministic HBV- and COVID-19-only models in the co-infection model (2).

3.6.2. Basic Reproductive Number of Stochastic Co-Infection Model

In this section, we determine the reproduction number of the COVID-19 and acute HBV stochastic co-infection model. We consider the co-infected class of (3).

We set a function Applying the Itô–Lévy formula to (40), we obtain

Considering partial derivatives with respect to of the initial infections F and of secondary infections V, we determine the basic reproduction number by means of the next-generation matrix [42] as follows

We solve (44) around DFE, and choose to get

Also

Multiplying F and and factorising , we get

Taking the spectral radius of i.e., = we obtain

3.6.3. Local Stability of Disease Free Equilibrium Point in the Co-Infection Model

Theorem 7.

If , then for any initial values of , satisfies .

Proof.

We set a function and apply the Itô–Lévy formula to the co-infected equation of (3) to obtain

3.6.4. Global Stability of Co-Infection Model

Theorem 8.

If , then is globally asymptotically stable in

3.7. Extinction of COVID-19 and HBV Co-Infection Disease

Next, we determine conditions under which the disease will eventually die out in the population with a probability of one. In this section, we study the conditions of extinction for the co-infection model.

Definition 3

([19]). We define , and .

Lemma 1

([40]). Let be the positive solution of system (4) with given initial condition . Let also N(t) be the positive solution of Equation (4) with given initial condition given condition . Then

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- , and

- 4.

- , a.s.

Theorem 9.

Proof.

Let be the Lyapunov function, then the Itô–Lévy expression of the co-infected equation of (3)

Next, we integrate both sides of (48) and obtain

where , , and .

Since , we choose a constant , and let to get

We divide through (49) by t to obtain

Next, we find the on both sides, apply Lemma 1, and factorise to obtain

where From (42), we have

Clearly,

If

then

From Lemma 1, we conclude that whenever

□

Next, we determine the condition for the extinction of HBV-only disease in the population.

Theorem 10.

Let be the solution of HBV only model from (3) with initial values , the HBV disease goes extinct almost surely if .

Proof.

Let be the Lyapunov function, and applying Itô’s formula yields

the Itô expression for the HBV-only infected class of (3). We integrate both sides to get

We know that hence, we have

We divide through by t, find the on both sides, apply Lemma 1, and factorise to obtain

where is a martingale. From (29), we have

Clearly,

If

then

From Lemma 1 we conclude that whenever

□

Next, we derive the condition for extinction of

Theorem 11.

Let be the solution of COVID-19 only model from (3) with initial values , the COVID-19 disease goes extinct almost surely if .

Proof.

Let be the Lyapunov function. Applying the Itô–Lévy formula gives

the Itô–Lévy expression for the COVID-19 infected class of the COVID-only system of (3). Next, we integrate both sides to get

We know that hence,

We divide through by t, find the on both sides, apply Lemma 1, and factorise to obtain

From (16) we have

where and are martingales.

Clearly,

For

then

From Lemma 1, we conclude that whenever

□

3.8. Persistence in Mean

Persistence of a disease means that the disease will remain endemic in the population with positive probability. We study the disease persistence for the system reported in (3) and derive that the disease persists under certain conditions.

Definition 4

Lemma 2

([44]). Set , assume that there exist , such that

such that satisfying a.s. Then

Theorem 12.

Let be a solution of system (3) with initial values

- 1.

- If and , , the disease persists in mean. In addition, satisfies

- 2.

- If , , , then the disease is persistent in mean. In addition, satisfies

Proof.

Next, find and apply a Lemma 2 and Definition 4 to obtain following results:

From (42), we have

Clearly,

If

then

By Definition 4 Lemma 2, we conclude that whenever ,

We begin by proving the persistence for co-infection of diseases. Thereafter, using similar techniques, we prove the persistence for singular diseases.

We recall the Itô–Lévy expression of the co-infected equation of (3).

By integrating both sides of (51), we obtain

where , , and Next, we choose divide through (52) the result by t, and apply comparison and Definition 3 to obtain

Next, we determine expressions for and

Adding terms and arrange terms of (54), rearranging and applying Definition 3, we obtain

and

where

and We substitute (55) and (56) into (53), take eliminate and apply the strong law of martingales (i.e., Lemma 1) to get

Next, we prove the persistence for the HBV-only model. By rearranging terms in (56), we get

Next, we integrate both sides of (28) and eliminate positive terms to get

We divide (59) by t and substitute (58) into (59), to get

We find and apply Definition 4 and Lemma 2 to get

From (29), we have

Clearly,

If

then

By Definition 4 and Lemma 2, we conclude that whenever ,

Next, we prove persistence in the mean for COVID-19. We recall the Itô–Lévy expression of the COVID-19 infected equation of (3):

Integrating both sides, we obtain

We divide (61) by t and substitute (58) into (61) to get

where , and . We eliminate take of both sides, and apply Definition 4 and Lemma 2 to get

From (16), we have

Clearly,

If

then

Using Definition 4 and Lemma 2, we conclude that whenever ,

□

4. Numerical Results

In this section, we employ a standard numerical procedure to obtain numerical simulation results for the HBV-only, COVID-19-only, and HBV–COVID-19 co-infection models. The objective here is to demonstrate the theoretical results obtained earlier in this thesis.

The estimated parameters in Table 2 were derived using a combination of publicly available epidemiological data (e.g., Ghana Health Service reports, WHO reports, and others taken from the international literature on COVID-19 and HBV due to data limitations), mathematical approximations using known biological and epidemiological relationships, and reasonable assumptions based on parameter values reported in similar studies when direct Ghana-specific data was unavailable.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 spread in Ghana (early 2020), the birth rate was approximately 28.60 births per 1000 people [45]. This gives us an estimate for recruitment rate: = 0.0286 per person.

An estimate for the natural death rate was determined using, Ghana’s life expectancy of (64.5 years) and formula The approximation was based on published rate from other Ghanaian studies; see e.g., [46].

The total COVID-19 death rate was estimated using , where is the COVID-19-induced death rate. Available data from Ghana shows that, as of 28 March 2022, there were 1445 COVID-19-related deaths and 161,370 confirmed COVID-19 cases [38]. Thus, Thus, per case.

To estimate the total death rate in HBV, we first estimate the induced rate From epidemiological studies, Ghana’s HBV prevalence is estimated at 8.48% 12.30%; see, e.g., [47]. Assuming a population of 32 million, the HBV-infected population would be According to [10], in 2022, over 15,000 people in Ghana died from hepatitis B- and C-related liver diseases. Thus, . Hence, the total death rate in HBV state is per case. With regards to the COVID-19 recovery rate, it has been reported that mild cases of COVID-19 typically resolve within 10–14 days [5]. We estimated the recovery rate as We scaled the value by 3 to reflect high recoveries in Ghana and to reflect published regional COVID-19 recovery rates; see, e.g., [48].

Acute HBV recovery occurs from over weeks to months [49]. We use an average infectious period of 60–180 days to estimate the recovery rate as

The parameter values used along with their sources are displayed in Table 2; few values of other parameters were assumed. We sought to verify theoretical results, so we selected initial values of We emphasise that the initial population of 100 susceptible and other populations were chosen as a scaled simulation to illustrate the qualitative dynamics of the system and do not reflect the absolute population size. The Euler–Maruyama scheme presented by [50] was employed in conducting the numerical simulations for all models. The results from numerical simulation for HBV-only, COVID-19-only, and co-infection models are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Table 2.

Parameters and description.

Table 2.

Parameters and description.

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 0.028 individual per day | [45] | |

| 0.033 per individual per day | Estimated [51] | |

| 0.053 per individual per day | Assumed | |

| per individual per day | [52,53] | |

| per individual per day | Estimated [47] | |

| 0.05 per day | Assumed | |

| per day | Assumed | |

| per day | Estimated [54] | |

| per day | Estimated [54] | |

| 0.3 per day | Estimated [6] | |

| ≈0.05 per day | Estimated | |

| 0.2 per day | [48,55] | |

| 0.03 per day | Estimated | |

| 0.01 per day | [56] | |

| 0.0110 per day | [23] | |

| 0.002 per day | Assumed | |

| 0.10 per day | [42] | |

| 0.02 per day | [46] | |

| 0.028 per day | Estimated [46] | |

| 0.03 per day | Assumed | |

| 0.021 per day | Estimated | |

| 0.024 per day | Estimated | |

| 0.03 per day | Assumed | |

| [0–1] | Assumed | |

| [0–1] | Assumed | |

| [0–1] | Assumed | |

| 0.05 | Assumed | |

| 1 | Assumed |

4.1. Hepatitis B Virus-Only Model

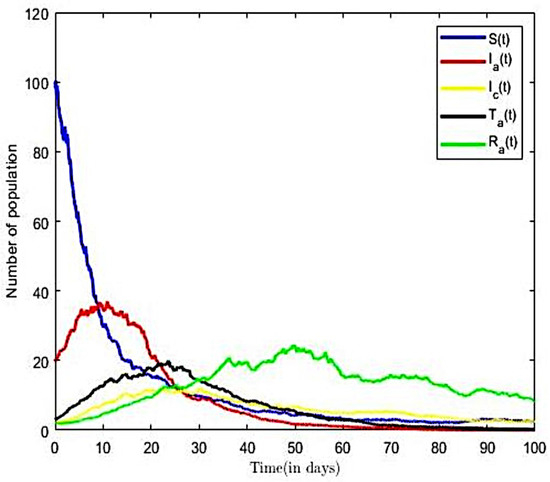

From the parameter values in Table 2, we calculated the reproductive number of the HBV model to be . The result implies that, on average, an infected person introduced into the population can infect more than one susceptible person; hence, the infection will continue. This result is consistent with other Ghanaian studies. Ref. [57] estimated the value of the reproductive number of HBV as thus suggesting an epidemic population. The trajectories of susceptible, infectious, treatment, and recovered classes in the HBV-only model (3) are displayed in Figure 3. Here, we fixed values of all parameters shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Solution for HBV-only model ().

From Figure 3, we observed that as the number of infectious population increase in time, the susceptible population decrease. However, in the long run, the solution curves for both the susceptible and infective compartments behave like decreasing functions and approach a fixed point. A decrease in the number of susceptible individuals occurred rapidly within the first fifteen time steps of the epidemic, after which there was gradual decline over time. We also observe a sharp increase in the number of HBV-infected within the first ten time steps and a relatively gradual increase in the number of individuals in the treatment (or hospitalised) and other compartments within the same period. Eventually, the infectious, recovered, and other classes approach a fixed point in the long run. In other words, the results suggest that all compartments will reach their respective endemic fixed point of the model (3) within a finite time and in the long run. The numerical outcomes verifies that, when , then the disease endemic equilibrium is locally and globally asymptotically stable.

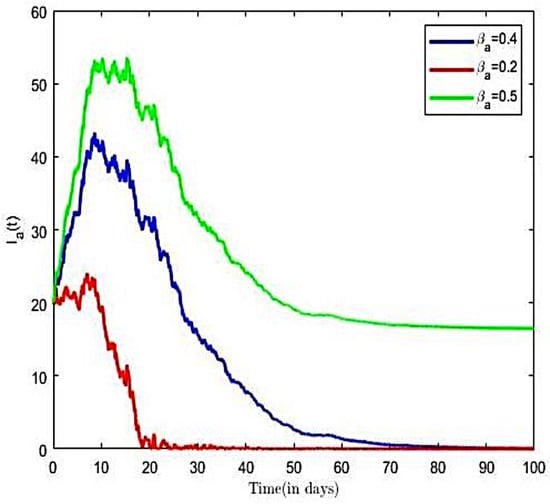

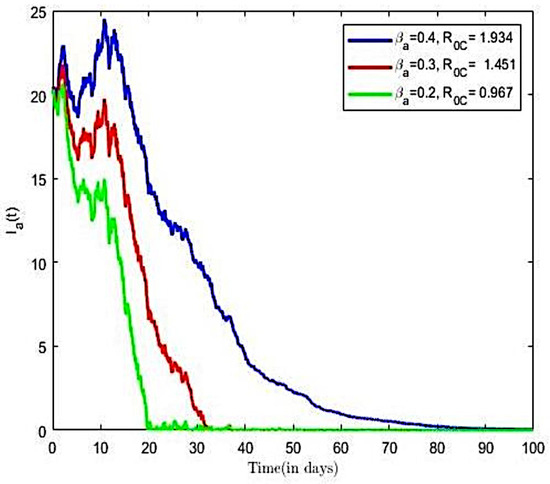

The impact of various parameters on the transmission dynamics of HBV is explored. Numerical results are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5. We proceeded by first investigating the effects of transmission rate on a population of infected individuals. This was conducted using selected values of transmission rates (), while all of the remaining parameter values of the model were held constant. From Figure 4, we observe that, as the value of the transmission rate increases, there is an increase in the number of HBV-infective, and vice versa. Next, we investigated the effects of the transmission rate on the reproductive number of the HBV-only model. Here, we held all other parameters constant and decreased the transmission rates ( = 0.4, 0.3, 0.2). Using the varied transmission rate, we estimated reproductive numbers as 1.934, 1.451, and 0.967, respectively. We observe from Figure 5 that, for the number of infective individuals already introduced into the population declined rapidly to a zero-disease-free equilibrium point. The observation implies that, at the disease will eventually become extinct. Further, it is observed from Figure 5 that an increase in the transmission rates from = 0.2 to = 0.4 led to increases in the reproductive number, which translates into an increase in the number of infective population over time, as well as an increase in the time to endemic equilibrium. Numerical simulations of the model in Figure 5 suggest that decreasing increasing compliance to protective measures or the decreasing disease transmission rates results in a reduction of and thus reduces the average number of HBV infections in the population, leading to the extinction of the disease. We therefore suggest that all persons comply to preventive measures, including vaccination, safe sexual practices, and desist from the sharing syringes, and also ensure that healthcare providers use sterile single-use needles and screen blood donations for HBV.

Figure 4.

HBV-infected with varied transmission rate.

Figure 5.

HBV-infected with varied transmission rate and Brownian noise.

4.2. COVID-19-Only Model

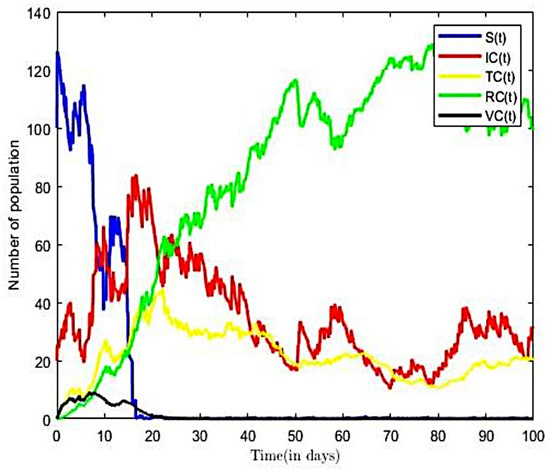

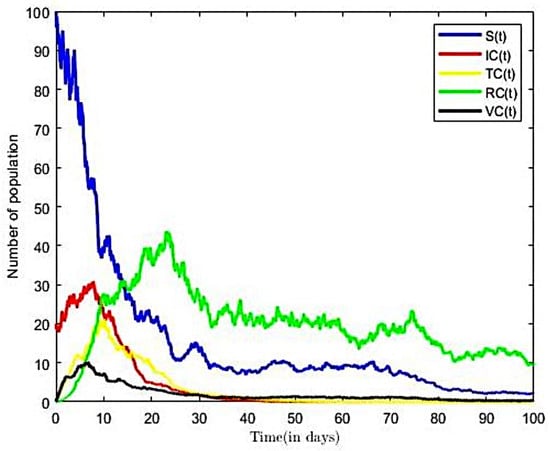

From the parameter values in Table 2, we calculated the reproductive number of COVID-19 of Ghana as , for a transmission rate on . The result implies that, on average, an infected person introduced into the population can infect more than one susceptible person; hence, the infection will continue. This result is consistent with other Ghanaian studies; see, e.g., [20,52]. According to [52], the estimated the value of the reproductive number of COVID-19 in Ghana ranges between and for transmission rates of 0.5 and 0.9, respectively, thus suggesting an epidemic population at these rates of transmission. The trajectories of susceptible, infectious, vaccinated, and recovered classes in the COVID-19-only model of (3) with both Brownian and Poisson noise and with only Brownian noise are displayed in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively. Here, we fixed values of all of the parameters shown in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Solution to COVID-19-only model with both noises ().

Figure 7.

Solution to COVID-19-only model with Brownian noise ().

From Figure 6, we observed that, as number of the infectious population increases over time, the susceptible population decreases. However, in the long run, the solution curves for both the susceptible and infective compartments behave like decreasing functions and approach a fixed point. A decrease in the number of susceptible individuals occurred rapidly within the first twenty-five time steps of the epidemic, after which there was gradual decline over time. The pattern was more rapid in Figure 6, occurring within fifteen time steps. From Figure 7, we also observe an increase in the number of COVID-19-infective within the first ten time steps and a relatively gradual increase in the number of individuals in the treatment (or hospitalised) and other compartments within the same period. Eventually, infectious, recovered, and other classes in Figure 7 approach a fixed point in the long run. In other words, the results suggest that all compartments will reach their respective endemic fixed point in the COVID-only model of (3) within a finite time and in the long run. The numerical outcomes verifies that, when the disease endemic equilibrium is locally and globally asymptotically stable. It is worth nothing from Figure 6 that the number of infective and the time to reach endemic fixed point were greatly influenced by the inclusion of finite jumps in the COVID-19-only model.

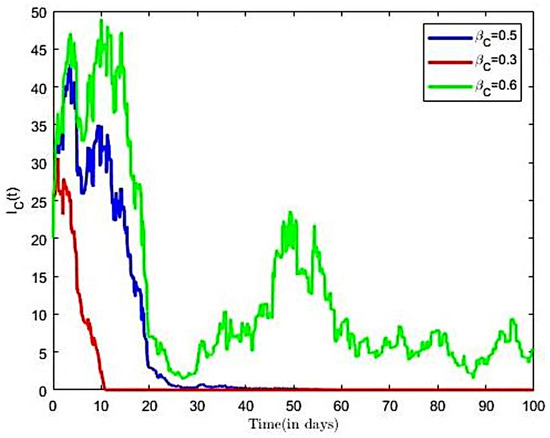

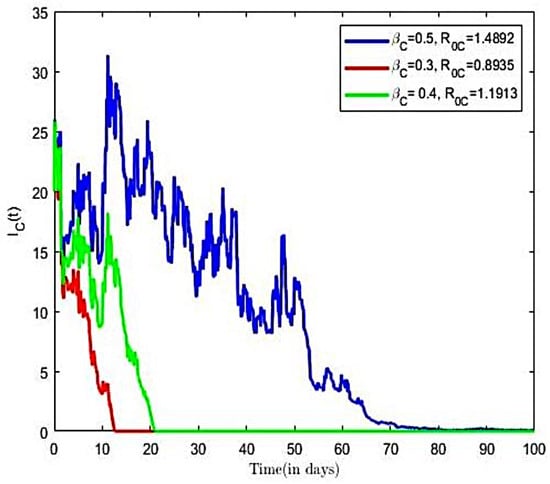

The impact of various parameters on the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is explored. Numerical results are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. First, we investigated the effects of transmission rate on population of infected individuals. This was conducted using selected values of transmission rates (), while all remaining parameter values of the model were held constant. From Figure 8, we observe that, as the value of the transmission rate increases, there is an increase in the COVID-19 infected population, and vice versa. Next, we investigated the effects of the transmission rate on the reproductive number of the COVID-19-only model. Here, we held all other parameters constant and varied the transmission rates = (0.3, 0.5, 0.6). Using the varied transmission rates, we estimated reproductive numbers as 0.8935, 1.1913, and 1.4894, respectively. We observe from Figure 9 that, for the number of infected individuals already introduced into the population declined rapidly to a disease free equilibrium point.

Figure 8.

COVID-19-infected with both noises ().

Figure 9.

COVID-19-infected with varied transmission rate and both noises ().

The observation from Figure 9 establishes the fact that, at COVID-19 disease becomes extinct as it approach a zero-endemic point. Further, it is observed from Figure 9 that an increase in the transmission rates from = 0.3 to = 0.6 led to increases in the reproductive number, which translates into increases in the number of infective population over time, as well as an increase in the time to endemic equilibrium. It is observed in Figure 9 that increasing compliance to protective measures or the decreasing disease transmission rates results in a reduction of and thus reduces the average number of COVID-19 infections in the population, leading to the extinction of the disease. This result is consistent with the finding of [30]. We therefore suggest that all persons comply with preventive measures, including social distancing, wearing facial mask, and the use of alcohol-based sanitizer.

4.3. Co-Infection Model

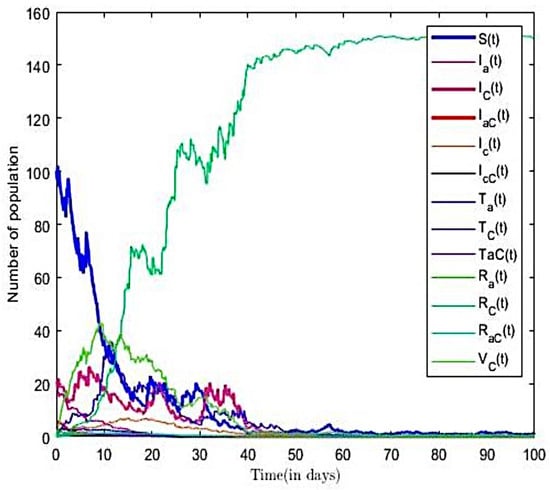

From the parameter values in Table 2, we calculated the reproductive number of co-infection model to be for (). This result implies that, on the average, an infected person introduced into the population can infect more than two susceptible people; hence, the infection will continue. The trajectories of susceptible, infectious, treatment, recovered, and other compartments in the co-infection model (3) are displayed in Figure 10. Here, we fixed values of all parameters shown in Table 2.

Figure 10.

Solution for co-infection model ().

From Figure 10, we observe that, as the number of the co-infectious population increases over time, the susceptible population decreases. However, in the long run, the solution curves for both the susceptible and infective compartments behave like decreasing functions and approach a fixed point. A decrease in the number of susceptible individuals occurred rapidly within the first fifteen time steps of the epidemic, after which there was gradual decline over time. We also see an increase in the number infected, treatment, and other compartments over the period. Eventually, infectious, recovered, and other classes approach a fixed point in the long run. In other words, the results suggest that all compartments will reach their respective endemic fixed point in the model (3) within a finite time and in the long run. The numerical outcomes verifies that, when , then the disease endemic equilibrium is locally and globally asymptotically stable.

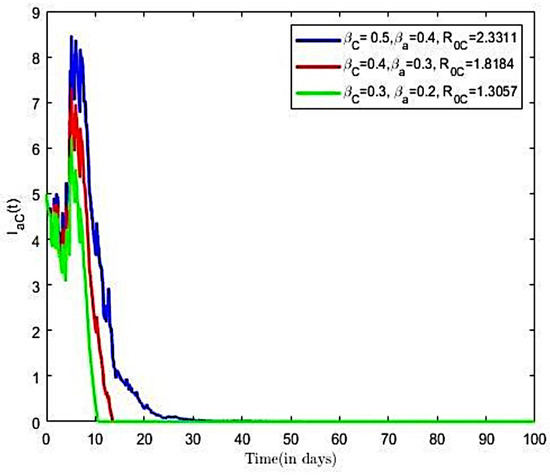

The impact of various parameters on the transmission co-infection dynamics is explored. Numerical results are presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12. First, we investigated the effects of transmission rate on population of infected individuals. This was conducted using varied pairs of values of transmission rates () and (), while all remaining parameter values of the model were held constant. From Figure 11, we observe that, as the value of the transmission rate increases, there is an increase in the number of co-infected with HBV and COVID-19. Next, we investigated the effects of the transmission rate on the reproductive number of the co-infection model using the aforementioned rates. We estimated reproductive numbers as 1.3057, 1.8184, and 2.3311, respectively. It is observed from Figure 11 that an increase in the transmission rates, and , resulted in increases in the reproductive number, which translates into increases in the number of co-infective population over time, as well as an increase in the time to endemic equilibrium. Thus, transmission parameters and are positively associated with co-infection growth. The finding suggests the need to implement measures that directly suppress transmission opportunities for each disease.

Figure 11.

Co-infected with varied transmission rate and .

Figure 12.

Co-infected population with varied transmission rate and .

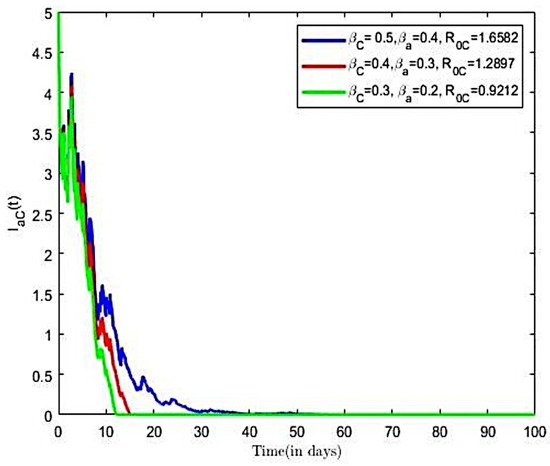

Next, we investigated the effects of the compliance with preventive measures on the reproductive number of the co-infection model (3). Here, we increased from 0.7 to 0.9, from 0.7 to 0.9, and all other parameters were held constant, which earlier paired varied transmission rates () and () were utilised. We estimated reproductive numbers as 0.9212, 1.2897, and 1.6582, respectively. It is observed from Figure 12 that an increase both COVID-19 and HBV compliance rate resulted in a reduction in the reproductive number, which translates into decreases in the number of co-infective population over time, as compared to Figure 12.

It is observed in Figure 12 that increasing compliance to COVID-19 and HBV preventive measures will result in a reduction in the number of co-infected individuals in the population, leading to the extinction of the disease. We therefore suggest that all persons comply to preventive measures including social distancing, wearing a facial mask, and the use of alcohol-based sanitizer, HBV vaccination, safe sexual practices, and desist from the sharing syringes, and also ensure that healthcare providers use sterile single-use needles and screen blood donations for HBV.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we sought to develop a stochastic compartmental model for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and HBV co-infection, establish the invariance and positivity of the stochastic co-infection model, determine the basic reproductive number for stochastic co-infection, determine conditions or stability at the disease-free equilibrium, determine the conditions of extinction and persistence of the stochastic model, and use numerical simulations to illustrate how various parameters and noises influence the spread and control of co-infection. The next-generation matrix method was used to derive the threshold values. Next, sufficient conditions for the stability of the model around the were derived using suitable Lyapunov function. Further, sufficient conditions for extinction and persistence were determined. Finally, by using the Euler–Murayama scheme, the theoretical results were demonstrated by means of numerical simulations. The effect of some parameters on disease transmission dynamics of all models were demonstrated. A summary of key findings from this research are as follows:

- A novel Poisson-driven stochastic co-infection model for COVID-19 and HBV was developed. The model considers COVID-19 prevention, HBV prevention, COVID-19 vaccination, and the combined effects of standard random fluctuations and large-scale disturbances caused by environmental factors.

- The invariance and positivity of both stochastic systems were established. The systems therefore remain in a biologically meaningful region, ensuring the reliability of the simulations and analysis.

- The basic reproduction numbers for stochastic COVID-19, HBV, and co-infection were derived. The threshold value was altered by both Brownian- and Poisson-driven noise.

- Lyapunov-based sufficient conditions guarantee global stochastic stability of the disease-free state.

- Sufficient conditions for extinction and persistence were derived analytically. Extinction occurs if all threshold values were less than one, and persistence occurs when all threshold values exceeded one.

- Numerical simulations reveal that transmission parameters and were positively associated with co-infection threshold, while increase in compliance to both COVID-19 and HBV measures resulted a reduction of the co-infection threshold. Further, it was found that the number of the infective population and the time to reach endemic fixed point were greatly influenced by both noises, particularly finite Poisson jumps in the COVID-19-only model.

The findings from numerical analysis suggest implementing measures that directly suppress transmission opportunities for each disease. A joint implementation of COVID-19 measures, such as crowd management, use of nose mask, and vaccination, and HBV measures, including ensuring that healthcare providers use sterile single-use needles and screen blood donations for HBV, will reduce the risk of co-infections. Again, based on the findings, there is the need for policies targeted at enforcing preventive measures and public education. Such policies can focus on the compulsory use of nose mask in public places and the strict use of hand-hygiene facilities at all public venues. Further, the numerical results suggest a need to incorporate stochastic risk into health interventions to prevent overconfident forecasts of disease trajectories. Finally, given the absence of comprehensive data on co-infection for some parameters, we recommend that future research conduct experimental research to obtain more accurate estimates, which would enhance predictions related to HBV and COVID-19 transmission and control.

Author Contributions

M.A.P. made the main contribution to this manuscript, including theoretical formulation, analysis, and simulations. S.E.M. supplied several suggestions in the theoretical part, and edited and proofread the manuscript. S.M.N. supplied several suggestions in the theoretical part, and edited and proofread the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not involve any studies on human subjects, human data or tissue, or animals. The study uses previously published data in the literature that are publicly available. The ethical guidelines and regulations governing the use of this data in the original publications were adhered to.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data used in this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faramarzi, A.; Norouzi, S.; Dehdarirad, H.; Aghlmand, S.; Yusefzadeh, H.; Javan-Noughabi, J. The Global Economic Burden of COVID-19 Disease: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Vaccination in Humanitarian Settings. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240079434 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Graphic Online. Health Minister Confirms 107 COVID-19 Cases at University of Ghana. Available online: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/health-minister-confirms-107-covid-19-cases-at-university-of-ghana.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B: Key Facts and Prevalence in Africa. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of Hepatitis B. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/signs-symptoms/index.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Omame, A.; Abbas, M.; Onyenegecha, C.P. A fractional order model for the co-interaction of COVID-19 and Hepatitis B virus. Results Phys. 2022, 37, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tian, X. Global Stability of a delay differential equation of hepatitis B virus infection with immune. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2013, 94, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, J.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Groeger, J.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, A.; Horn, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krause, G.; Ott, J.J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghana Business News. Some 42 People Die Everyday in Ghana from Hepatitis B and C Related Diseases. Ghana Business News. 20 September 2024. Available online: https://www.ghanabusinessnews.com/2024/09/20/some-42-people-die-everyday-in-ghana-from-hepatitis-b-and-c-related-diseases (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Friedman, A.; Siewe, N. Chronic hepatitis B virus and liver fibrosis: A mathematical model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Z.; Ling, J.; Hu, W.; Cao, Q.; Mo, P.; Yao, L.; Yang, R.; Gao, S.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 and Hepatitis B Virus Co-infection. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayaturohmat, F.; Anggriani, N.; Supriatna, A.K.; Biswas, M.H.A. A systematic literature review of mathematical models for coinfections: Tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDS. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chi, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, K.; Chen, M.; Wang, D.; Tung, T.; et al. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on liver function in patients with hepatitis B. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yuan, J.; Long, Q.; Hu, J.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Lu, M.; Huang, A. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 and HBV co-infection are at risk of greater liver injury. Genes Dis. 2021, 8, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiridou, M.; Adam, P.; Meiberg, A.; Visser, M.; Matser, A.; De Wit, J.; Op De Coul, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis B virus vaccination and transmission among men who have sex with men: A mathematical modelling study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 4889–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklu, S.W. Impacts of optimal control strategies on the HBV and COVID-19 co-epidemic spreading dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teklu, S.W. Analysis of HBV and COVID-19 Coinfection Model with Intervention Strategies. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2023, 6908757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, A.; Amine, S.; Allali, A. A stochastically perturbed co-infection epidemic model for COVID-19 and hepatitis B virus. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 1921–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.E.; Nyandjo-Bamen, H.L.; Menoukeu-Pamen, O.; Asamoah, J.K.K.; Jin, Z. Global stability dynamics and sensitivity assessment of COVID-19 with timely-delayed diagnosis in Ghana. Comput. Math. Biophys. 2022, 10, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.; Mora, M.R.; Gómez, P.J. Estimation of the epidemiological evolution through a modelling analysis of the COVID-19 outbreak. Microbiology 2020, 3, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Iboi, E.A.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Gumel, A.B. Will an imperfect vaccine curtail the COVID-19 pandemic in the US? Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, M.L.; Rwezaura, H.; Tchoumi, S.Y.; Tchuenche, J.M. A Mathematical Model of COVID-19 with Vaccination and Treatment. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 1250129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.J. An Introduction to Stochastic Processes with Applications to Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, Z.; Lu, Y. A mathematical model of hepatitis B virus transmission and its application for vaccination strategy in China. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 29, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danane, J.; Allali, K.; Hammouch, Z. Mathematical analysis of a fractional differential model of HBV infection with antibody immune response. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 136, 109787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.T.; Leung, K.; Leung, G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet 2020, 395, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.A.; Nie, Y.; Din, A.; Alkhazzan, A. Dynamics of Hepatitis B Virus Transmission with a Lévy Process and Vaccination Effects. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2024, 12, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A., Jr.; Barton, D.A.W.; Ritto, T.G. Uncertainty quantification in mechanistic epidemic models via cross-entropy approximate Bayesian computation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 9649–9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobbi, M.A.; Naandam, S.M.; Moore, S.E. Mathematical modelling and analysis of stochastic malaria and COVID-19 co-infection model. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Jiang, D.; Shi, N. The Behavior of an SIR Epidemic Model with Stochastic Perturbation. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2012, 30, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, M.F.; Rasul, R.R.Q.; Hammouch, Z.; Rasul, K.A.H.; Danane, J. Analysis of a stochastic SEIS epidemic model with the standard Brownian motion and Lévy jump. Results Phys. 2022, 37, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharan, R. The role of stochastic processes in understanding epidemic spread and control. Libr. Prog. Int. 2024, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeb, A.; Hussain, S.; Alzahrani, E. Dynamics of COVID-19 mathematical model with stochastic perturbation. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, K. Extinction and persistence of a stochastic SICA epidemic model with standard incidence rate. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fatini, M.; El Khalifi, M.; Gerlach, R.; Laaribi, A.; Taki, R. Stationary distribution and threshold dynamics of a stochastic SIRS model with a general incidence. Physica A 2019, 534, 120696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeahalam, C.; Williams, V.; Otwombe, K. Factors associated with COVID-19 infections and mortality in Africa: A cross-sectional study using publicly available data. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manu, S.D. Ghana COVID-19 Dataset; Kaggle. 2020. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/ds/657993 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Ghana Health Service. 2016 Annual Report; Ghana Health Service: Accra, Ghana, 2017. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2016-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Sabbar, Y. Mathematical Analysis of Some Stochastic Infectious Disease Models with White Noises and Lévy Jumps. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah de Fès (Maroc), Fes, Morocco, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.J.S. Stochastic Population and Epidemic Models: Persistence and Extinction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye, A.W.; Satana, T.S. Stochastic model of the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, N.; Greenhalgh, D.; Mao, X. A stochastic model of AIDS and condom use. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 325, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Upadhyay, R.K.; Misra, A.K.; Rihan, F.A.; Ghosh, D. Mathematical model of COVID-19 with comorbidity and controlling using non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IndexMundi. Ghana—Birth Rate. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/ghana/birth-rate (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Adu, I.K.; Aidoo, A.Y.; Darko, I.O.; Osei-Frimpong, E. Mathematical model of hepatitis B in the Bosomtwe district of Ashanti region, Ghana. Appl. Math. Sci. 2014, 8, 3343–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartey, Y.A.; Okine, R.; Seake-Kwawu, A.; Ghartey, G.; Asamoah, Y.K.; Senya, K.; Duah, A.; Owusu-Ofori, A.; Amugsi, J.; Suglo, D.; et al. A nationwide cross-sectional review of in-hospital hepatitis B virus testing and disease burden estimation in Ghana, 2016–2021. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusto, F.B.; Erovenko, I.V.; Fulk, A.; Abu-Saymeh, Q.; Romero-Alvarez, D.; Ponce, J.; Sindi, S.; Ortega, O.; Saint Onge, J.M.; Peterson, A.T. To isolate or not to isolate: The impact of changing behavior on COVID-19 transmission. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021: Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hbv.htm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Jahnke, T. Numerical Methods in Mathematical Finance. Karlsruher Institut für Technologie. 2016. Available online: https://www.math.kit.edu/ianm3/lehre/numfima2016w/media/num-meth-math-fin.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination. Ghana National Hepatitis Elimination Profile. Key Takeaways. Available online: https://www.globalhep.org/sites/default/files/content/page/files/2021-12/Ghana%20National%20Hepatitis%20Elimination%20Profile%20-%20December%202_1.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Otoo, D.; Donkoh, E.K.; Kessie, J.A. Estimating the Basic Reproductive Number of COVID-19 Cases in Ghana. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2021, 14, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusto, F.B.; Numfor, E.; Srinivasan, K.; Iboi, E.A.; Fulk, A.; Saint, O.; Jarron, M.; Peterson, A.T. Impact of public sentiments on the transmission of COVID-19 across a geographical gradient. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinyo, M.E.; Duti, V.; Dubik, S.D.; Amegah, K.E.; Kutsoati, S.; Oduro-Mensah, E.; Puplampu, P.; Gyansa-Lutterodt, M.; Darko, D.M.; Buabeng, K.O.; et al. Clinical characteristics, treatment regimen and duration of hospitalization among COVID-19 patients in Ghana: A retrospective cohort study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumel, A.B.; Iboi, E.A.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Ngwa, G.A. Toward Achieving a Vaccine-Derived Herd Immunity Threshold for COVID-19 in the U.S. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 709369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttcher, L.; Nagler, J. Decisive conditions for strategic vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Chaos 2021, 31, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botwe, W.K. Deterministic SIR Model of Hepatitis B Virus Infection and the Impact of Vaccination (The Case of Sunyani Municipality). Master’s Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).