Abstract

The process of wound healing is intricate and regulated by a network of cellular, molecular, and biochemical pathways. Acute wounds progress via distinct phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. Chronic wounds frequently cease to heal and exhibit resistance to conventional therapies. These types of injuries are frequently attributed to diabetes, infection, or senescence. Existing therapies are constrained due to their ineffectiveness against bacteria, inability to promote regeneration, and inadequate control over medication release. Nanotechnology presents novel methods to overcome these challenges by providing multifunctional platforms that enable biological repair and medicinal delivery. Nanoparticles, which combat germs and modulate the immune system, in addition to being intelligent carriers that react to pH, oxidative stress, or enzymatic activity, provide targeted and adaptive wound therapy. Nanocomposite hydrogels are particularly advantageous as biointeractive dressings due to their ability to maintain wound moisture while facilitating regulated drug delivery. Recent advancements indicate their potential to aid in tissue regeneration, enhance therapy precision, and address issues related to safety and translation. Nanotechnology-based approaches, especially smart hydrogels, give significant promise to transform the future of wound care due to their flexibility, adaptability, and efficiency.

1. Introduction

Wound healing is a complex biological process that entails numerous tightly regulated interactions among cells and substances. Minor injuries can undergo natural healing through a sequence comprising hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, epithelialization, and maturation. Chronic and non-healing wounds present significant challenges in treatment, especially in patients with diabetes or compromised immune systems [1,2]. Moreover, in wounds, microbial infections, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses restrict the regeneration process [3].

The application of nanotechnology in wound management has evolved significantly over the past two decades. Early developments in the 2000s focused primarily on silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents. In the 2010s, research expanded to polymeric nanocarriers, nanofibers, and hydrogel composites for controlled drug delivery and tissue regeneration. More recent efforts emphasize multifunctional and bioresponsive nanoplatforms, including smart nanocomposites capable of real-time infection sensing and controlled therapeutic release.

Conventional wound therapies frequently prove ineffective for chronic wounds due to their inability to ensure sustained drug delivery, adequate antibacterial efficacy, or regulation of cellular signaling. As a result, currently, there is a growing interest in, and need for, advanced treatment techniques or strategies that help to speed up wound healing and restore skin integrity while decreasing side effects such as infection, fibrosis, or severe scarring [4,5].

Nanotechnology has emerged as an essential tool or approach in biomedical science, providing the development of novel materials that enable control at the molecular level. Nanoparticles (NPs) are considered to have remarkable potential for enhancing wound healing results because of their surface-area-to-volume ratio, variable surface chemistry, and size. They play a role in promoting angiogenesis, reducing bacterial burden, modulating immunological responses, and delivering bioactive substances directly to the wound bed [6,7,8].

Nanomaterials can replicate the extracellular matrix (ECM), enhance fibroblast proliferation, and influence signaling pathways that govern tissue remodeling and repair [9]. Silver-, zinc oxide-, chitosan-, PLGA-, and lipid-based nanoparticles are examples of the organic, inorganic, and hybrid platforms that are used in designing biomaterials for the treatment of wounds. In addition, each of these platforms has unique properties, such as antibacterial activity or the ability to release medical agents under regulated conditions. Extensive validation of safety, biocompatibility, and scalability is required for the clinical application of nanomaterials in wound care [10,11,12,13]. The incorporation of nanoparticles into wound care signifies a promising direction for enhanced healing and a paradigm shift towards personalized and multifunctional therapeutic platforms.

This review presents a discussion about the mechanisms by which nanoparticles stimulate wound repair, lists the main categories/types of nanomaterials used in clinical and experimental applications, and deliberates on prospective avenues for their application in wound healing technologies.

2. Wound Healing: A Physiological Perspective

The wound healing process in the skin is regulated by time and space and has evolved over time. It goes through four stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [14,15].

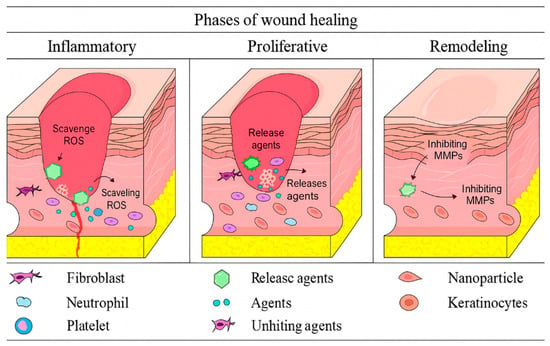

As shown in Figure 1, immune and skin cells work together to accelerate wound healing processes in the presence of nanoparticles (Figure 1) [14,16]. Growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines help to regulate this process, and in addition, the interaction between the skin and the microbiome has an effect on these stages. Disruptions in signaling pathways, sometimes including interleukins and growth factors, can lead to chronic wounds that cause long-term challenges in healing [14,17].

Figure 1.

Control of the wound healing process by nanoparticles during the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases.

- Hemostasis and inflammation

Hemostasis initiates the wound healing process immediately following an injury to prevent blood loss. Platelets accumulate at the injury site and secrete clotting factors, PDGF, and TGF-β. Neutrophils generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and secrete enzymes, including elastase and cathepsin G, to eliminate pathogens and debris [1,18,19,20,21]. This phase typically endures for two to three days. Platelet-derived mediators, such as VEGF, promote vasodilation and fibroblast recruitment via paracrine and autocrine signaling, thus priming the tissue for regeneration [22,23,24]. Inflammation is crucial for defense and repair; nevertheless, its persistence or dysregulation results in chronic wound development. Thus, addressing inflammation is as vital as its onset, and nanomaterials are being developed to regulate immune responses, reduce oxidative stress, and promote effective healing [25,26].

- Development and transformation

In chronic wounds, persistent inflammation, poor fibroblast function, reduced angiogenesis, and microbial colonization hinder the healing process [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. These wounds are characterized by a disorganized extracellular matrix, excessive protease activity, and dysfunctional signaling.

The proliferative phase commences post-inflammation, during which fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells infiltrate the wound bed. These cells produce extracellular matrix components and facilitate the formation of new blood vessels, hence contributing to granulation tissue development. Keratinocytes facilitate skin healing by re-epithelializing and reinstating the skin barrier. Myofibroblasts facilitate wound contraction by mechanical forces [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Initially, collagen III serves as a structural scaffold; subsequently, collagen I replaces it.

The final phase, remodeling, commences approximately three weeks post-injury and may persist for several months. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cytokines regulate this phase, encompassing extracellular matrix (ECM) rearrangement, collagen maturation, and the reinstatement of tensile strength. The apoptosis of excess cells contributes to the prevention of fibrosis and hypertrophic scarring [44,45,46].

Nanoparticles represent a possible solution as they specifically target critical pathways. Functionalized scaffolds with VEGF or PDGF-BB enhance angiogenesis, whereas polymeric nanoparticles provide EGF or antioxidants to promote re-epithelialization [47,48,49,50]. Enzyme-responsive carriers modulate MMP activity [51,52,53], whereas inorganic nanoparticles like silica or calcium phosphate promote collagen remodeling [54]. Furthermore, nanoparticles that specifically target TGF-β and are encapsulated with siRNA can reduce fibrosis and accelerate tissue regeneration [55,56].

These technologies provide exact molecular regulation of wound healing through interactions with fibroblasts, keratinocytes, collagen networks, and proteases, therefore accelerating tissue regeneration and improving results in chronic wounds.

3. Nanoparticles in Wound Healing: Mechanisms and Functions

Nanoparticles play a crucial role in wound healing by eradicating bacteria, regulating drug distribution, and enhancing cellular responses. Nanomaterials have a significant surface area-to-volume ratio and the capacity to alter their physicochemical properties, including hydrophobicity, surface charge, and dimensions. This constitutes their primary advantage over bulk materials. These characteristics enhance engagement with biological targets and penetration into wound tissue [57,58].

The biological activity of nanoparticles is significantly affected by their dimensions, charge, and surface chemistry. Nanoparticles smaller than 200 nm penetrate tissues more readily and are efficiently internalized by cells via endocytosis. Positively charged particles exhibit enhanced interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes and host cells, hence augmenting both antibacterial efficacy and cellular absorption [13,51].

Diverse metallic nanoparticles generate various types of reactive oxygen species (ROS) contingent upon their surface reactivity and redox potential. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) primarily induce the generation of superoxide anions (O2−•) and hydroxyl radicals (OH), which disrupt bacterial membranes and alter protein conformation. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) generate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals upon exposure to ultraviolet or visible light. They are highly effective at eradicating germs, but at elevated doses, they may induce oxidative stress in fibroblasts. Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) participate in Fenton-like reactions, producing highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that effectively dismantle microbial biofilms and stimulate angiogenesis at low concentrations. The regulated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) at normal concentrations might augment signaling pathways related to cell migration and tissue remodeling, whereas excessive ROS levels may hinder healing through oxidative damage [59,60,61,62,63].

Nanoparticles function as controlled medication delivery systems, preserving chemicals such as curcumin, antibiotics, and growth hormones from degradation and ensuring their release at the appropriate time and location. This is particularly beneficial for persistent wounds such as diabetic ulcers. Gold nanoparticles combined with antioxidants (EGCG, α-lipoic acid) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing inflammation and accelerating angiogenesis.

Nanoparticles can replicate the native extracellular matrix (ECM) due to their biomimetic characteristics. This facilitates cellular adhesion, motility, and growth, particularly during the proliferative phase of healing [51]. Moreover, stimuli-responsive systems using materials like chitosan, alginate, and PLGA can release therapeutic drugs in response to wound-specific signals, such as pH fluctuations or oxidative stress, thereby improving localized drug delivery and reducing systemic toxicity [52,64].

Nanoparticles have the capability to modulate the immune system, facilitating healing by administering anti-inflammatory drugs or altering the phenotype of macrophages from M1 to M2, a significant transformation frequently unattainable in chronic wounds [52,53].

A novel generation of hybrid-engineered nanoparticles possesses medicinal cores, such as silver, zinc oxide, and copper, encased in sensitive polymeric or lipid shells. Ag-ZnO or Cu–chitosan hybrids are examples of these systems. They eradicate bacteria while simultaneously administering angiogenic or anti-inflammatory medicines. Likewise, NO-releasing PLGA-PEI particles and liposomal nanocomposites have dual roles as immune modulators and drug carriers [15,50].

These multifunctional platforms enable nanoparticles to actively facilitate wound healing, combat infection, regenerate tissue, and diminish inflammation.

Two primary categories of nanomaterials utilized in wound healing are those possessing intrinsic healing characteristics and those used for medication delivery.

Types of Nanoparticles Used in Wound Healing

The nanoparticles which are used in the wound healing process can be characterized according to their composition and intended function. Three primary categories are identified: (1) nanoparticles exhibiting inherent therapeutic efficacy, (2) nanoparticles serving as drug delivery materials, and (3) smart hybrid systems that integrate a carrier with a therapeutic agent and respond to environmental changes.

- Metallic nanoparticles

Nanoparticles applied in wound healing can be classified according to their composition and intended function. Three main categories are distinguished: (1) nanoparticles with intrinsic therapeutic activity, (2) nanoparticles used as drug delivery platforms [65,66], and (3) smart hybrid systems encompassing a carrier for the therapeutic agent and response to an altering environment [67,68,69,70]. Metallic and metal oxide nanomaterials, including silver, gold, and zinc oxide nanoparticles, have antibacterial properties against a diverse array of species. They compromise bacterial membranes, produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), and impede microbial DNA replication. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are effective against bacteria which form biofilms and demonstrate multidrug resistance, making them important in the treatment of chronic wounds [13,66,67,68,69,70].

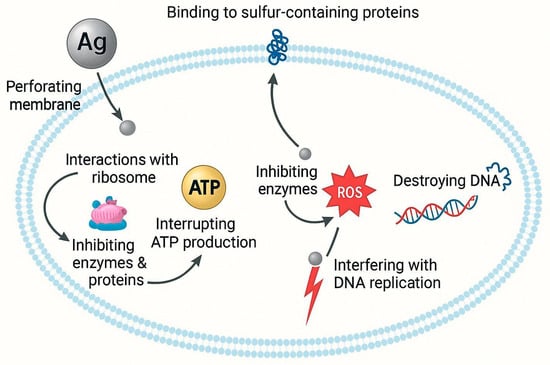

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are widely used due to their effectiveness in eradicating bacteria, especially those demonstrating multidrug resistance and capable of biofilm formation. They operate by compromising microbial membranes, obstructing DNA replication, and interfering with enzymes associated with respiration. Their ability to regulate cytokines contributes to alleviating inflammation and minimizing scar growth. Nanocrystalline silver dressings, such as Acticoat®, facilitate prolonged Ag+ release, enhancing coverage and diminishing toxicity relative to conventional silver compounds [71]. AgNPs demonstrate a multifaceted mechanism of action, including the breakdown of bacterial membranes, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the attenuation of pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. This makes them very effective against chronic infections (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). AgNPs interact with bacterial cells through multiple mechanisms. They perforate the cell membrane, bind to sulfur-containing proteins, and interfere with ribosomal functions, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis. AgNPs also disrupt ATP production and enzyme activity, resulting in oxidative stress through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The elevated ROS levels cause DNA damage and replication inhibition, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death.

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have shown efficacy in eliminating pathogens and promoting cellular regeneration. When combined with antioxidants such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and α-lipoic acid, they enhance wound closure by facilitating angiogenesis and diminishing inflammation [72]. The action mechanism of AuNPs primarily enhances healing through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant pathways, improves endothelial function, and promotes vascular regeneration in the wound bed [17,22,23,24,25,26].

Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) display enhanced antibacterial efficacy and reduced cytotoxicity relative to silver. They also promote collagen synthesis and expedite the development of granulation tissue. ZnO nanoflowers demonstrate improved pro-angiogenic activity attributable to their morphology, both in vitro and in vivo [73]. ZnO nanoparticles eliminate bacteria by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) while concurrently stimulating fibroblasts, hence enhancing collagen synthesis and the development of new blood vessels, both essential for tissue regeneration [62,74,75].

- Polymer and biopolymer nanoparticles

Chitosan nanoparticles are favored for their biocompatibility, hemostatic properties, and inherent antibacterial activity. They may also be utilized for transporting pharmaceuticals and treating injuries [76].

Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Polycaprolactone (PCL) are synthetic biodegradable polymers that provide regulated drug release and serve as scaffolds to replicate the extracellular matrix (ECM) structure, hence enhancing fibroblast proliferation and wound re-epithelialization [77].

Hydrogel-Based Nanoparticles: Traditional hydrogels are three-dimensional polymeric networks with macroscopic dimensions, widely recognized for their moisture retention, biocompatibility, and drug release capabilities. In contrast, nanogels or hydrogel-encapsulated nanoparticles operate at the nanoscale, enabling improved penetration, controlled release, and targeted delivery. In this review, the focus is primarily on nanocomposite hydrogels, which integrate nanoparticles into polymeric matrices to combine structural stability with nanoscale functionality. Hydrogel-forming nanoparticles are distinctive within polymeric systems due to their high-water content, structural flexibility, and ability to maintain a moist wound environment, which is crucial for expedited healing. Hydrogels composed of polymers such as polyethene glycol (PEG), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), chitosan, alginate, and hyaluronic acid are extensively utilized in wound therapy because of their biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and customizable degradation rates. These networks can encapsulate antibiotics, antioxidants, or growth factors and release them in a regulated manner in response to variations in pH, reactive oxygen species, or enzymes at the wound site [78,79,80].

Smart hydrogel nanocomposites, such as chitosan/alginate hydrogels infused with silver or zinc oxide nanoparticles, provide antibacterial protection and facilitate the formation of granulation tissue. Thermoresponsive hydrogels, such as Pluronic F127, and injectable gels formed via in situ crosslinking are materials that enable minimally invasive application while adapting to uneven wound shapes.

Injectable and sprayable hydrogel nanocarriers have gained popularity due to their facilitation in chronic wound management. These systems can conform to wound morphology, prolong the retention of therapeutic drugs, and simultaneously administer numerous bioactive molecules, such as VEGF and EGF, thereby accelerating angiogenesis and epithelial regeneration in diabetic and burn wound models [69,70].

Hydrogel-based nanoparticles perform various roles beyond mere physical protection; they actively modulate inflammation, promote cellular migration and proliferation, and provide sustained, localized treatment in both acute and chronic wound settings.

- Clay-based nanoparticles for wound healing

Clay-derived nanoparticles, particularly smectite minerals like bentonite, have emerged as attractive platforms for biomedical applications due to their natural prevalence, biocompatibility, and layered architecture that enables intercalation and sustained release of therapeutic compounds. In the field of wound healing, these materials have inherent hemostatic, adsorptive, and antibacterial characteristics, and can be altered to improve their therapeutic effectiveness [71].

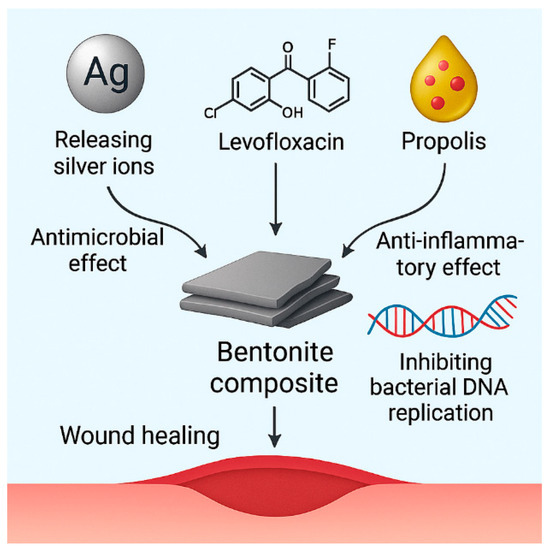

Recent studies indicate that bentonite can be effectively modified with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), levofloxacin, and propolis to produce multifunctional nanocomposites for wound care applications (Figure 3). These composites were used as coatings on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) surgical meshes, enhancing their bactericidal properties and rendering them appropriate for application in wound dressings. SEM and TEM investigations confirmed the homogeneous distribution of nanoparticles on the mesh surface, whereas EDX spectra verified the presence of critical elemental ingredients, including Ag and C/O from organic modifiers [81].

Figure 3.

Mechanistic representation of a multifunctional bentonite-based composite system for wound healing applications.

The bentonite–AgNP composite uses the wide-ranging antibacterial properties of silver ions, which hurt bacterial membranes, cause oxidative stress, and stop DNA replication. Our results showed that there were significant inhibitory zones against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli and that the cells were not very toxic to fibroblast cells, which means that the therapeutic index was high [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81].

The bentonite–levofloxacin combination works in two ways: first, the clay surface adsorbs levofloxacin, which makes it release in response to changes in pH; second, the medication itself stops DNA replication by blocking bacterial topoisomerases. We used UV-Vis spectrophotometry and adsorption isotherm modeling (Langmuir and Freundlich) to measure how the medication and clay interacted [82]. The Transport of Diluted Species module in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.5 simulations showed that levofloxacin could diffuse across simulated bacterial membranes in a regulated way, which matched what was seen in the real-life antibacterial kinetics [83].

The bentonite–propolis combination also uses the phenolic and flavonoid-rich profile of propolis to provide natural antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects. The clay matrix enhances the solubility and retention of phenolic chemicals, therefore facilitating the control of cytokine production and fibroblast proliferation throughout the proliferative phase. FTIR spectra verified the interaction between carboxylic and hydroxyl functional groups in bentonite and propolis components, while inhibition zone investigations demonstrated either additive or synergistic effects with silver or antibiotic co-modification [84].

Adding these composites to PVDF and polyurethane matrices exhibited good adherence, flexibility, and ability to handle exudate, which are all important for wound dressing applications. These formulations facilitate both passive protection and active intervention through antimicrobial release, extracellular matrix mimicking, and cellular regulation [85].

Bentonite-based nanocomposites are a cheap, scalable, and customized way to help wounds heal faster. New research is concentrating on enzyme- or ROS-responsive composite systems and electrospun nanofiber-clay hybrids that facilitate localized administration and adaptive biological response [86].

- Hybrid and composite nanostructures

Nanoparticle-Embedded Hydrogels and Nanofibers: These materials protect wounds and administer drugs to specific areas at the same time. For example, electrospun nanofibers that include growth factors like VEGF and PDGF-BB speed up the formation of new blood vessels, while hydrogels that contain nanoparticles hold more moisture and are more stable mechanically [9].

Regarding nanoparticles that release nitric oxide, these systems use NO as both an antimicrobial and a therapeutic agent. Examples include PLGA-PEI nanoparticles that release NO, helping collagen remodeling and fighting bacteria that are resistant to treatment, such as MRSA [65].

Carbon-Based Nanoparticles (e.g., Graphene Oxide, Fullerenes): These nanomaterials have powerful properties that fight inflammation and oxidation. Photothermal therapy using graphene oxide nanosheets has been used to treat infected wounds, and it works quickly, with little damage to the tissue [87].

Carbon-based structures (like fullerenes and graphene oxide) and polymeric nanocarriers (like chitosan and PLGA) are examples of nonmetallic nanomaterials that have even more benefits. They have qualities that fight inflammation, protect cells from damage, and help cells grow. For example, PLGA nanoparticles that release nitric oxide have been demonstrated to have both antibacterial and pro-healing effects by speeding up angiogenesis and matrix remodeling in infected wounds [64].

- Targeted drug delivery for wound treatment

Conventional wound care techniques frequently exhibit inadequate medication penetration and suboptimal retention at the wound location. Nanoparticles, including polymeric and lipid-based formulations, have been engineered to encapsulate and release therapeutic substances in a regulated manner. This precise distribution minimizes systemic toxicity while improving the absorption of growth hormones, anti-inflammatory medicines, and antibacterial medications [1].

Conventional wound care techniques frequently encounter constraints like inadequate medication penetration, diminished bioavailability, and systemic adverse effects. Nanotechnology has resolved these challenges by creating intelligent, responsive, and targeted drug delivery systems. These nanosystems provide targeted action, prolonged release, and enhanced pharmacokinetics through the use of nanocarriers, including liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, dendrimers, and polymeric vesicles [88].

A significant example is the application of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive polymeric nanoparticles for the delivery of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), a chemokine crucial for mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and wound angiogenesis. These nanoparticles, made of poly(1,4-phenyleneacetone dimethylene thioketal), experience site-specific depolymerization in oxidative conditions, releasing SDF-1 at the wound location and enhancing healing in full-thickness wounds [89].

A novel method involves applying acetylated PAMAM dendrimer-based nanocarriers modified with E-selectin ligands to direct stem cells to combat endothelium inflammation. This method, functioning as a “GPS” system, has been shown to improve stem cell homing and angiogenesis without eliciting immunological toxicity [90].

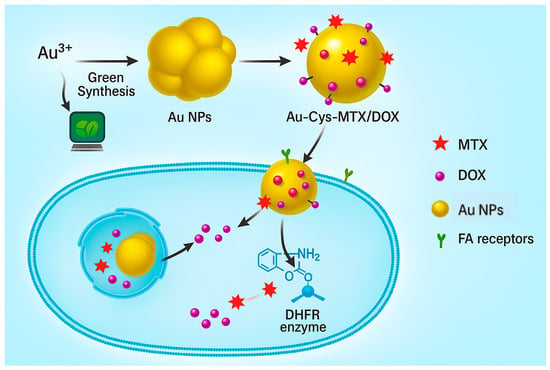

Lipid-based technologies have been utilized, including antihypoxamiR-functionalized lipid nanoparticles that deliver anti-miR-210 for ischemic wounds. This intervention resulted in substantial re-epithelialization and enhanced mitochondrial oxidative function in chronic wound models (Figure 4) [91].

Figure 4.

Targeted drug delivery using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) functionalized with cysteine, methotrexate (MTX), and doxorubicin (DOX). AuNPs, formed by green synthesis, are then functionalized for a specific drug delivery system. These nanoparticles bind to folic acid (FA) receptors on the cell surface, promoting internalization and subsequent release of therapeutic agents. MTX inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), while DOX induces cytotoxicity, enabling synergistic antibacterial or anticancer effects.

Furthermore, curcumin—recognized for its antioxidant and antibacterial attributes—has been encapsulated within porous silane composite nanoparticles to guarantee prolonged topical release and durability against degradation. This formulation showed enhanced efficacy in the healing of infected burn wounds [92].

Alternative carriers, such as liposomes containing madecassoside, have been used to enhance fibroblast activity, accelerate angiogenesis, and diminish scarring. These tailored nanosystems demonstrate how nanotechnology enables the precise delivery of medications to target locations, hence minimizing systemic exposure [93].

Recent advancements in nanotechnology have led to the development of responsive and site-specific drug delivery systems designed to address the complex nature of chronic wounds. Polymeric nanoparticles, such as PLGA, chitosan, and alginate-based carriers, offer enhanced encapsulation efficiency, biodegradability, and the capacity for sustained and targeted drug release [1,94]. These systems diminish systemic exposure and prolong the presence of the therapeutic agent at the wound site, hence accelerating the healing process.

Hydrogel-based nanoparticles enhance this concept by creating a moist wound environment while simultaneously delivering encapsulated drugs. Their porous characteristics facilitate a regulated and often stimuli-responsive release in reaction to wound-specific triggers, such as pH or enzymatic activity. This is particularly beneficial for infected or diabetic wounds [95]. The amalgamation of hydrogels with nanoparticles enhances their biocompatibility and facilitates the simultaneous delivery of many therapeutics, including antibiotics and growth hormones.

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) are two categories of lipid nanoparticles that function effectively as topical delivery systems. Lipid-based systems enhance medication solubility and facilitate transdermal penetration. They also prevent the degradation of unstable chemicals and diminish the body’s inflammatory reaction. Their diminutive particle size enables penetration into the wound bed and biofilm matrix, hence enhancing therapy efficacy [96].

Antibodies or peptides that target ligands can be conjugated to the surfaces of nanoparticles to facilitate targeted drug delivery to specific areas. This approach ensures that the medicine only interacts with target cells in the wound, such as fibroblasts or endothelial cells. This reduces off-target effects and enhances therapeutic efficacy [97,98,99].

Nanosystems are being utilized for the transmission of genetic elements like siRNA and miRNA, which modulate gene expression concerning inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis. These gene-based therapies signify a groundbreaking advancement in individualized wound care, with numerous nanocarrier systems currently under investigation in preclinical animal studies [100,101,102].

Nanomaterials used in wound healing are often grouped due to their primary function: structural scaffolds, antibacterial agents, or drug delivery systems. Collagen nanofibers, chitosan-based nanogels, and electrospun polymeric membranes illustrate structural nanomaterials that offer a biocompatible framework facilitating cellular migration and angiogenesis. Antimicrobial nanomaterials, specifically silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), zinc oxide (ZnO), copper oxide (CuO), and titanium dioxide (TiO2), are used for their ability to destroy microbial membranes, inhibit biofilm formation, and modulate inflammatory responses. Simultaneously, drug-loaded nanocarriers such as liposomes, micelles, dendrimers, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles are designed to encapsulate antibiotics, growth factors, or antioxidants for regulated and targeted delivery to the wound [12,17,32,45].

A novel category of engineered hybrid nanomaterial has emerged alongside these existing classifications. These materials can function as both active therapeutic agents and intelligent drug delivery systems, encompassing nanosystems with multifunctional capabilities, metallic cores that eradicate microorganisms (such as silver, zinc oxide, or copper), and polymeric or lipid-based shells that facilitate controlled, stimuli-responsive release of medicinal compounds. For example, Ag-ZnO or Cu–chitosan hybrids exhibit a broad spectrum of antibacterial properties while simultaneously providing anti-inflammatory or pro-regenerative agents to targeted regions. Alternative architectures, such as PLGA-PEI complexes that release nitric oxide or liposome-coated nanocomposites, are designed to modulate immune system function and expedite re-epithelialization through intrinsic and cargo-mediated mechanisms. These dual-purpose platforms collaborate to enhance intricate wound settings by connecting structural healing with metabolic regulation [50,51,52,53,54].

- Enhancement of cellular responses and tissue regeneration

Nanoparticles facilitate tissue repair by promoting fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and angiogenesis. Nanoparticles promote cell migration and differentiation through interactions with extracellular matrix proteins and cellular receptors, hence accelerating wound closure [3].

Nanoparticles significantly contribute to tissue regeneration by promoting essential biological processes such as fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and re-epithelialization. The effects are amplified by interactions with extracellular matrix (ECM) components and cellular receptors, collectively creating a favorable microenvironment for tissue repair [47].

An essential technique involves the fabrication of nanoengineered scaffolds that mimic the fibrous and molecular architecture of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). Electrospun nanofibers composed of materials such as PLGA/silk fibroin have been shown to facilitate fibroblast adhesion and proliferation, hence accelerating wound healing in diabetic models [47]. These nanostructured matrices facilitate the incorporation of growth factors such as VEGF and PDGF-BB, or therapeutic nucleic acids like siRNA, to enhance cellular proliferation and reduce the activity of matrix-degrading enzymes [48].

Additionally, stem cell–cell–nanoparticle composites have been utilized to enhance regenerative capacity. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) integrated with PLGA-collagen nanofiber scaffolds demonstrated improved stem cell adhesion and expedited wound repair in full-thickness lesions. The combination of nanotopography and biochemical cues enhanced the homing and pro-angiogenic activity of stem cells without causing immunotoxic effects [55].

Nanoparticles infused with curcumin and systems that emit nitric oxide (NO) exemplify nanomaterials that facilitate expedited tissue healing. These formulations modulate inflammation, promote granulation tissue formation, and aid in collagen remodeling, while assuring sustained release and minimizing the degradation of active compounds [49].

The interaction of nanostructure morphology, biochemical transport, and cellular function demonstrates the intricate involvement of nanoparticles in promoting tissue regeneration. These methods enable nanoparticles to expedite the healing process and improve the quality of regenerated tissue, hence reducing the incidence of hypertrophic scars and contractures [50].

Nanoparticles play a significant role in the cellular dynamics associated with wound healing. Through engagement with extracellular matrix (ECM) constituents and cell membrane receptors, they facilitate fibroblast migration, keratinocyte proliferation, and angiogenesis, all of which are crucial for wound closure and tissue remodeling [56]. Functionalized nanoparticles can stimulate integrin-mediated pathways that regulate cytoskeletal remodeling, promote adhesion, and enhance proliferation, analogous to the function of the extracellular matrix in the body [94].

Hydrogels and electrospun nanofibers composed of biocompatible polymers serve as scaffolds that replicate the architecture of real tissues. These structures establish a porous, three-dimensional framework that facilitates cellular connectivity and directional movement, while also permitting the passage of nutrients and gases.

Besides offering structural support, numerous nanocarriers facilitate the localized and prolonged release of bioactive chemicals such as VEGF, EGF, and bFGF. The controlled release enhances the activation and recruitment of progenitor cells to the wound bed, facilitating the formation of granulation tissue and the emergence of capillaries [38]. Certain inorganic nanoparticles, like silica and calcium phosphate, can independently elicit osteogenic and angiogenic responses. These processes are crucial for profound and persistent wounds [54].

The surface charge is essential for cellular interactions. Positively charged nanoparticles exhibit enhanced cellular uptake due to their attraction to negatively charged membranes. This facilitates the entry of pharmaceutical compounds into cells [103]. Conversely, negatively charged nanoparticles may establish a stable milieu for extracellular matrix production and cytokine control, perhaps facilitating regeneration indirectly [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116].

Nanoparticles can infiltrate wounded tissues effectively due to their diminutive size and elevated surface-to-volume ratio. This results in a more uniform therapeutic dispersion and cellular response. This enhances epithelial coverage, tensile strength, and collagen remodeling [104].

- Smart and responsive nanoparticles

Smart or stimuli-responsive nanoparticles represent a sophisticated method in wound healing by enabling controlled, context-specific drug delivery. These systems are engineered to respond to specific alterations in the wound’s microenvironment, such as variations in pH, temperature, oxidative stress, and bacterial enzyme activity [105].

Recent advancements in nanotechnology have led to the development of “smart” nanoparticles—engineered entities capable of responding to pathophysiological circumstances such as oxidative stress, acidic pH, or enzyme dysregulation. These devices are designed to exclusively deliver therapeutic agents at the wound site, thus granting physicians control over the timing and location of drug administration, enhancing therapy efficacy while minimizing unwanted effects in other body regions [106].

Polymeric nanoparticles, synthesized from poly (1,4-phenyleneacetone dimethylene thioketal), that respond to reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been developed to deliver stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α). These nanoparticles remain intact under standard physiological settings, yet they disintegrate into tiny fragments at reactive oxygen species-rich inflamed wound sites, releasing SDF-1α precisely where it is required. This has been shown to significantly enhance mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and accelerate angiogenesis and wound closure in full-thickness dermal wounds [89].

An additional example is the development of a multifunctional hydrogel incorporating prodrugs that can be decomposed by UV light, pH-sensitive fluorescent silica nanoparticles (SNP-Cy3/Cy5), and upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs). This composite device detects bacterial infections by measuring changes in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) signals under acidic conditions and simultaneously releases antimicrobial agents upon exposure to near-infrared (NIR) light, delivering treatment precisely at the site of infection [107].

Furthermore, pH-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) have been developed to assess wound conditions and deliver drugs accordingly. These MSNPs are present in wound dressings composed of bacterial cellulose. Upon exposure to the acidic environment prevalent in inflamed wounds, they undergo color transformation and discharge the encapsulated compounds. This dual capability enables both diagnostic and therapeutic applications in real-time wound management [108].

A novel concept involves nanoparticles that react to enzymes and utilize matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), prevalent in chronic wounds, to deliver pharmaceuticals. These systems can encapsulate anti-inflammatory or antibacterial agents that are activated solely during elevated MMP activity, providing a tailored and localized treatment approach for the issue at hand [109].

Smart liposomal carriers have been altered with ligands that react to acidic microenvironments. In diabetic wounds, pH-sensitive liposomes encapsulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and ceramides facilitate coordinated release, resulting in enhanced granulation tissue development and vascular regeneration [110,111,112].

These intelligent nanocarriers integrate biochemical reactivity with structural adaptability, rendering them a promising novel approach for wound healing, particularly for chronic and infected wounds where conventional treatments often fail [91].

4. Clinical Applications and Challenges of Nanoparticles in Wound Healing

The combination of nanoparticles (NPs) into wound healing strategies has opened a new direction for the development of tissue regeneration, infection control, and wound repair. Different types of nanoparticles—such as silver (AgNPs), gold (AuNPs), zinc oxide (ZnO-NPs), titanium dioxide (TiO2-NPs), and polymeric or lipid-based nanocarriers—have been investigated for their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and pro-angiogenic properties.

Some preclinical and early clinical investigations showed that silver, gold, zinc oxide (ZnO), and polymer/lipid-based nanoparticles reduce bacteria growth, modulate inflammation, and promote re-epithelialization [52,63,113], Additionally, it has been shown that polymeric nanoparticles can enhance the controlled release of growth factors and antibiotics by improving drug stability and bioavailability at wound sites [113]. However, clinical trials aimed at the enhancement of these materials have presented challenges and limitations. According to the limited data from phase I/II studies or animal models, it is difficult to evaluate the validation of designed nano-based materials. Challenges and limitations during experiments can also include the stability and manufacturing reproducibility of nanoparticles, as well as difficulties in sterilization. For this reason, nowadays, researchers focus on designing multifunctional nanomaterials that are capable of addressing complex biological processes in acute and chronic wounds [52,63,113,114,115].

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the key nanoparticles used in wound healing, summarizing their applications, limitations, and supporting evidence. This helps highlight both their therapeutic potential and the main challenges limiting clinical translation.

Table 1.

Clinical applications and challenges of, as well as supporting evidence for, common nanoparticles used in wound healing.

4.1. Current Nanotechnology-Based Wound Care Products

Several clinically approved nanoparticles have been used in wound care. For example, Acticoat® nanocrystalline silver dressings, which are prepared by embedding Ag0 nanoparticles in a nanocrystalline matrix, showed rapid bactericidal and wide-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy in both in vitro and clinical settings [63].

Studies have shown that any systemic toxicity was not detected when Acticoat® was applied, even to regions with a large surface area [113].

Similarly, Aquacel® Ag, a hydrofiber dressing that contains ionic silver, promotes moisture retention and prolonged release of Ag+, improving patient comfort and speeding up the healing of wounds [114]. It has been shown that silver-based dressings accelerate chronic wound healing and decrease infection rates. Recently, Liang et al. showed that these silver-based dressings accelerate chronic wound healing, decrease infection rates, and reduce time to complete healing [59]. Accelerated healing rates with the use of a silver-based electrospun antimicrobial dressing in a porcine wound regeneration model were reported by Thuan Do et al. [60]. In vivo experiments demonstrated that all three samples—PCLGelAg, Aquacel and UrgoTul dressings—better supported wound healing, while also preventing infection and inflammation, compared with the control. The results indicated the practical potential of applying the PCLGelAg membrane in the treatment of burn injuries [60]. Various commercial dressings, such as Silvercel and lalugen Plus, which are formulated using combinations of silver salt, nanoparticles, or sulfadiazine, address the healing of different wound types [61]. Briefly, silver remains the dominant nanoparticle in available products, including electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds loaded with silver or zinc oxide nanoparticles to promote regenerative processes in wounds.

In addition to silver-based formulations, Curad® zinx oxide-based products with antimicrobial, protective, and UV-shielding capabilities are suitable for application in cases of wound-related irritation (Curad zinc oxide skin cream, Medline). Moreover, chitosan-based nanocomposites incorporating ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles have enhanced wound healing effectiveness by speeding up wound closure [62].

In summary, nanoparticle-based dressing products have strong antimicrobial benefits, and they have shown minimal cytotoxicity at low concentrations. For this reason, it is important to determine the right timing and dosage of nanoparticle use in wound healing. Taking this information into account, continued clinical evaluation is required to create multifunctional nanomaterials that can control the regenerative process in wound care.

4.2. Safety and Toxicity Considerations

Although nanotechnology-based wound care products have demonstrated therapeutic value, their safety and toxicity profiles demand rigorous examination. For example, in one study, significant cytotoxicity to normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) and human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) was observed with ionic silver (Ag+), while AgNPs were safe at low concentrations (up to 25 µg/mL) [116]. However, studies have revealed that AgNPs can trigger oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammatory cytokine release in the skin. In vitro experiments have shown an increase in immune cells and reactive oxygen species quantity after applying silver-containing dressings [117]. Similarly, at high concentrations, ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles are able to generate reactive oxygen species if they are not precisely formulated [61,118,119,120,121,122,123].

The main challenge in the evaluation of nanotoxicity arises from the variability of experimental materials or models and the lack of standardized testing protocols. The variation in nanoparticles’ size, morphology, concentration, and surface functionalization methods significantly affects results and complicates the interpretation of preclinical findings regarding clinical applications [118,119,120,121,122].

Nanoparticles can induce dose-dependent cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and immunogenic reactions, notwithstanding their therapeutic advantages. Elevated concentrations of silver and copper nanoparticles exceeding 25–50 µg mL−1 can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and death in cutaneous fibroblasts. Conversely, prolonged exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles may induce genotoxicity and inflammatory signaling [123]. Furthermore, metallic nanoparticles may accumulate in tissues, prompting concerns regarding their long-term safety and clearance efficacy. Surface coating and controlled release tactics are essential to mitigate these effects. Moreover, interactions between nanoparticles and the immune system, including macrophage activation and cytokine cascades, require careful assessment to ensure biocompatibility and prevent chronic inflammation.

Cytotoxicity generated by nanoparticles predominantly arises from the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial impairment, and DNA fragmentation. For instance, silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles can alter membrane permeability and inhibit mitochondrial electron transport, resulting in cell death. The concurrent dissolution of metallic ions (Ag+, Cu2+, Zn2+) in biological fluids triggers oxidative stress and the production of inflammatory cytokines [61,120,124,125]. Prolonged exposure may result in the buildup of nanoparticles in organs such as the liver, spleen, and skin, potentially causing persistent oxidative and immunological activation. The dimensions, coatings, and surface charges of nanoparticles significantly influence these effects. This underscores the significance of designing clinical nanomaterials for biodegradability and controlled release.

In addition, other practical challenges include heterogeneity in wound etiology, patient variability, and cost-effectiveness in comparison with gold standard treatments. The lack of nano-specific guidelines also affects the commercialization procedure of the designed products. To overcome these barriers, standardized manufacturing methods, stable protocols, toxicity tests, and well-structured clinical trials for nano-formulated materials are urgently required.

4.3. Regulatory and Ethical Implications

The development of nanoparticle-based wound care solutions raises several ethical and regulatory concerns. Current regulatory frameworks, such as the FDA and EMA, often evaluate nanomedicines in the same manner as conventional pharmaceuticals or medical devices. In 2014, the FDA established guidelines stipulating that nanoparticles should be evaluated individually, with considerations of size, shape, and function addressed at the outset. However, a specific clearance procedure for nanotechnology-based products has not been established [119,126,127,128].

The European Union (EU) governs nanotechnology-based medical products and devices through established legislation, including Directive 2001/83/EC and the Medical Device Regulation (MDR). The reflection papers provide developers with assistance; nevertheless, they do not provide explicit or legally obligatory requirements [129]. The absence of globally recognized definitions, toxicity assessment methodologies, and labeling requirements may lead to the underestimation of health risks and environmental risks or the circumvention of regulatory supervision [130]. Regulatory frameworks struggle to classify intricate nano-formulations that possess antibacterial, regenerative, and sensing properties as medicinal medicines, medical devices, or combination items [129,131,132,133].

To ensure the ethical advancement of nanotechnology in wound care, it is required to establish clear and consistent definitions, standardized testing protocols, regulatory endorsement, transparent product information, and communication between scientists, manufacturers, healthcare professionals, patients, and environmental organizations. These protocols will ensure that nano-based wound remedies align with public preferences, safety standards, and expectations regarding trustworthiness.

5. Limitations of Nanoparticles in Wound Healing

Nanoparticles possess significant promise to enhance wound healing therapies; nevertheless, several challenges impede their complete integration into clinical practice. Nanotoxicity remains a significant concern. Metallic nanoparticles such as silver, zinc oxide, and titanium dioxide exhibit significant antibacterial characteristics; but, at elevated concentrations, they can generate excessive reactive oxygen species, leading to DNA damage, oxidative stress, and the apoptosis of fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Gold nanoparticles, notwithstanding their regenerative properties, incur substantial expenses and have unclear long-term biosafety profiles. Polymeric carriers such as PLGA, chitosan, or lipid-based systems exhibit biocompatibility; nonetheless, their degradation rates and inter-batch variability can complicate the attainment of optimal therapeutic outcomes.

A significant restriction concerns the stability and repeatability of the production processes. The dimensions, charges, and surface modifications of nanoparticles determine their physicochemical qualities, thus significantly influencing their behavior in biological systems. Minor alterations during synthesis can lead to fluctuations in performance and render interactions with biological systems unpredictable. Moreover, most investigations are limited to in vitro or small animal models, leading to an absence of substantial clinical evidence from large-scale human trials. Ultimately, regulations and financial constraints hinder rapid adoption by individuals. The absence of universally recognized nano-specific laws and the substantial expenses associated with the production and testing of nanoparticles impede their commercialization and utilization in hospitals. These constraints necessitate prudent optimism. Future developments must emphasize therapeutic efficacy, alongside rigorous safety assessments, scalable synthesis, and economical production, to enable the transition of nanotechnology-based wound treatments from the laboratory to clinical use.

6. Conclusions

Nanotechnology has changed regenerative medicine by making it possible for wounds to heal faster than with traditional treatments. Nanoparticles provide multifunctional platforms that simultaneously address infection management, inflammatory modulation, and tissue regeneration, successfully resolving the complex challenges related to acute and chronic wounds. Their distinctive physicochemical adaptability, resulting from differences in size, surface chemistry, and environmental responsiveness, improves customized therapeutic delivery and maximizes molecular interactions with biological systems. Metallic nanoparticles, such as silver, gold, and zinc oxide, have pronounced antibacterial and pro-regenerative properties. Polymeric and hydrogel-based nanocarriers serve as scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix. This makes it easier to distribute medicines, growth hormones, and genetic material in a controlled and focused way. The development of clay-based nanocomposites and hybrid nanosystems demonstrates the versatility of nanotechnology in producing multifunctional wound care solutions through the integration of natural, synthetic, and bioactive elements.

Notwithstanding these advancements, numerous issues persist that hinder their application in traditional medical practice. Nanotoxicity, variations in synthesis, stability, and sterilization problems are still big issues that need to be solved by consistent testing and thorough regulatory frameworks. The variety of causes of wounds and the different ways that patients’ bodies react to them mean that treatment plans need to be tailored to each person and able to change as needed. From a translational perspective, the successful clinical implementation of nanotechnology-based wound dressings depends on optimizing biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical flexibility, while ensuring scalable synthesis and regulatory safety. Materials with multifunctional features—such as self-adhesive, antimicrobial, and controlled release properties—are most promising for clinical adaptation. In particular, adhesive nanodressings are emerging as an innovative class of wound care materials, combining polymeric bioadhesives with metallic or carbon-based nanofillers to improve tissue adherence, moisture balance, and accelerated healing. We also need to think about ethics, cost-effectiveness, and mass production to make sure everyone can use them. Nanotechnology-based wound healing will use “smart” and adaptable systems that can find and treat wounds, allowing for real-time monitoring and changes to therapy as needed. Encouraging cooperation between materials scientists, doctors, and regulatory agencies helps turn new ideas from the lab into safe, affordable solutions for use in the clinic. Nanotechnology represents a groundbreaking advancement in wound therapy, significantly transforming existing methodologies. It makes sure that patients all over the world recover faster, have fewer problems, and have a better quality of life.

The commercialization of nanotechnology-based wound dressings is still nascent, with only a limited number of products, primarily silver- and polymer-based nanocomposite dressings, currently available on the clinical market. Producing nanomaterials in substantial quantities is challenging due to issues related to batch homogeneity, cost efficiency, and regulatory approval. To circumvent these issues, an increasing number of individuals are employing scalable synthesis techniques like electrospinning, sol–gel processing, and green synthesis. Continuous collaboration between academic research and industry is essential to bridge laboratory innovation with market application and to ensure safety and quality control when scaling.

Future research should focus on the development of biodegradable, stimuli-responsive, and self-regulating nanosystems capable of releasing therapeutic medicines in response to localized biochemical signals. Conducting additional in vivo and clinical validation will be crucial to bridging the divide between laboratory innovations and their application in medicine. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration integrating materials science, biotechnology, and regulatory policy is essential for developing next-generation nanoplatforms that are safe, scalable, and economically viable in the long run. Such enhancements will accelerate the transition of nanotechnology-based wound care therapies into tailored and durable medical treatments.

Author Contributions

A.A. (Alibala Aliyev): conceptualization, writing (original draft, review, and editing). A.I.: conceptualization, writing (original draft, review, and editing). U.H.: writing (original draft, review, and editing). Z.G.: project administration, writing (original draft, review). A.A. (Aida Ahmadova): writing (original draft, review, and editing). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Azerbaijan Science Foundation—Grant AEF-MGC-2024-2(50)-16/15/4-M-15.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Kumar, M.; Mahmood, S.; Chopra, S.; Bhatia, A. Biopolymer based nanoparticles and their therapeutic potential in wound healing—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, M.M.; Dima, M.B.; Dima, B.; Holban, A.M. Nanomaterials for wound healing and infection control. Materials 2018, 12, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladini, F.; Pollini, M. Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles for wound healing application: Progress and future trends. Materials 2018, 12, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jari Litany, R.I.; Praseetha, P.K. Tiny tots for a big-league in wound repair: Tools for tissue regeneration by nanotechniques of today. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Chopra, S.; Mahmood, S.; Mirza, M.A.; Bhatia, A. Formulation, optimization, and evaluation of non-propellant foam-based formulation for burn wounds treatment. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 113, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushiken, L.F.S.; Stone, R.C.; Stojadinovic, O.; Pastar, I. Cutaneous wound healing: An update from physiopathology to current therapies. Life 2021, 11, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tottoli, E.M.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Chiesa, S.; Pisani, E. Skin wound healing process and new emerging technologies for skin wound care and regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Hilles, A.R.; Ge, Y.; Bhatia, A.; Mahmood, S. A review on polysaccharides mediated electrospun nanofibers for diabetic wound healing: Their current status with regulatory perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekram, B. Functionalization of biopolymer-based electrospun nanofibers for wound healing. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 8308–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethi, G.U.; Somasundaram, S.; Nandini, A.; Varadharaj, S. Electrospun polysaccharide scaffolds: Wound healing and stem cell differentiation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2022, 33, 858–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Mishra, R.; Singh, P.; Singh, R. Correction: Therapeutic potential of nanocarrier-mediated delivery of phytoconstituents for wound healing: Their current status and future perspective. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sharma, A.; Singh, V.; Singh, P. Foam-based drug delivery: A newer approach for pharmaceutical dosage form. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, M.M.; Dima, M.B.; Dima, B.; Holban, A.M. Nanocoatings for chronic wound repair—Modulation of microbial colonization and biofilm formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, M.K.; Iqubal, A.; Imtiyaz, M.; Gupta, A. Natural, synthetic and their combinatorial nanocarriers based drug delivery system in the treatment paradigm for wound healing via dermal targeting. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4551–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, A.E.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Nanomaterials for wound dressings: An up-to-date overview. Molecules 2020, 25, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, M.S. Nanotoxicity in systemic circulation and wound healing. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 1253–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Sun, S.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yao, H.; Zhang, Z. Opportunities and challenges of nanomaterials in wound healing: Advances, mechanisms, and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.T. Hemostatic agents for prehospital hemorrhage control: A narrative review. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidova-Rice, T.N.; Hamblin, M.R.; Herman, I.M. Acute and impaired wound healing: Pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2012, 25, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Young, A.; McNaught, C.E. The physiology of wound healing. Surgery 2017, 35, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, J.P.; Kamel, R.A.; Caterson, E.J.; Eriksson, E. Clinical impact upon wound healing and inflammation in moist, wet, and dry environments. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.G.; Chen, S.A.; Chen, H.M.; Wu, W.M.; Hung, C.F.; Yao, Y.D.; Tu, C.S.; Liang, Y.J. The effects of gold nanoparticles in wound healing with antioxidant epigallocatechin gallate and α-lipoic acid. Nanomedicine 2012, 8, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medhe, S.; Bansal, P.; Srivastava, M.M. Enhanced antioxidant activity of gold nanoparticle embedded 3,6-dihydroxyflavone: A combinational study. Appl. Nanosci. 2014, 4, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimovich, N.O.; Ezhevskii, A.A.; Guseinov, D.V.; Smirnova, L.A.; Gracheva, T.A.; Klychkov, K.S. Antioxidant properties of gold nanoparticles studied by ESR spectroscopy. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 2008, 57, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarathManiKanth, S.; Kalishwaralal, K.; Sriram, M.; Pandian, S.R.; Youn, H.S.; Eom, S.; Gurunathan, S. Anti-oxidant effect of gold nanoparticles restrains hyperglycemic conditions in diabetic mice. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuvel, A.; Adavallan, K.; Balamurugan, K.; Krishnakumar, N. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Solanum nigrum leaf extract and screening their free radical scavenging and antibacterial properties. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2014, 4, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Martin, P.; Tomic-Canic, M. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 265sr6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, L.E.; Stojadinovic, O.; Pastar, I.; Tomic-Canic, M. Biology and biomarkers for wound healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 18S–28S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. Cellular and molecular basis of wound healing in diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinovic, O.; Pastar, I.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Vukelic, S.; Krzyzanowska, A.; Tomic-Canic, M. Deregulation of epidermal stem cell niche contributes to pathogenesis of nonhealing venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2014, 22, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Stone, R.C.; Stojadinovic, O.; Ramirez, H.; Pastar, I.; Maione, A.G.; Smith, A.; Yanez, V.; Veves, A.; Kirsner, R.S.; et al. Integrative analysis of miRNA and mRNA paired expression profiling of primary fibroblast derived from diabetic foot ulcers reveals multiple impaired cellular functions. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, H.; Stojadinovic, O.; Diegelmann, R.F.; Entero, H.; Lee, B.; Pastar, I.; Golinko, M.; Rosenberg, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. Molecular markers in patients with chronic wounds to guide surgical debridement. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brem, H.; Golinko, M.S.; Stojadinovic, O.; Kodra, A.; Diegelmann, R.F.; Vukelic, S.; Entero, H.; Coppock, D.L.; Tomic-Canic, M. Primary cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with chronic wounds: A methodology to produce human cell lines and test putative growth factor therapy such as GM-CSF. J. Transl. Med. 2008, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loesche, M.; Gardner, S.E.; Kalan, L.; Horwinski, J.; Zheng, Q.; Hodkinson, B.P.; Tyldsley, A.S.; Franciscus, C.L.; Hillis, S.L.; Mehta, S.; et al. Temporal stability in chronic wound microbiota is associated with poor healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, R.; Yu, L.; He, F.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L.; Liang, L.; Wang, L. Dermal fibroblast migration and proliferation upon wounding or lipopolysaccharide exposure is mediated by stathmin. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 781282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Collagen in wound healing. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbul, A. Proline precursors to sustain mammalian collagen synthesis. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2021S–2024S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaugh, V.L.; Mukherjee, K.; Barbul, A. Proline precursors and collagen synthesis. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, G.C.; Werner, S.; Barrandon, Y.; Longaker, M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008, 453, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B. Myofibroblasts. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 142, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdai, F.; Risaliti, C.; Monici, M. Role of fibroblasts in wound healing and tissue remodeling. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 958381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Tamma, R. Giulio Gabbiani and the discovery of myofibroblasts. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; Stojadinovic, M.; Yin, A.; Ramirez, L.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelialization in wound healing: A comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.C.; Costa, T.F.; Andrade, Z.A.; Medrado, M.A. Wound healing: A literature review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayuningtyas, R.A.; Sutrisno, R.; Sari, A.; Nugraha, T. The collagen structure of C1q induces wound healing. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riwaldt, S.; Corydon, C.; Aleshcheva, M.; Hemmersbach, A. Role of apoptosis in wound healing and apoptosis alterations in microgravity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 679650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.; Dahiya, U.; Dhingra, D.; Dilbaghi, N.; Kim, K.H.; Kumar, S. Evaluation of anti-diabetic activity of glycyrrhizin-loaded nanoparticles in nicotinamide-streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Deng, C.; McLaughlin, C.R.; Liu, X. Electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for promoting wound healing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.; Bora, P.; Kasoju, N.; Goswami, P. Synthesis of novel bioactive nanocomposite for curcumin delivery and its application in wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 730–740. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.; Harde, H.; Jain, S. Therapeutic applications of nitric oxide releasing polymeric nanomaterials. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 495, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D.; Vydiam, K.; Vangala, V.; Mukherjee, S. Advancement of nanomaterials- and biomaterials-based technologies for wound healing and tissue regenerative applications. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2025, 8, 1877–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.; Rezaei, A.; Eghbali, S.; Nasirizadeh, S.; Alemzadeh, E.; Alemzadeh, M.; Shadi, M.; Sedighi, M. Nanomaterial strategies in wound healing: A comprehensive review of nanoparticles, nanofibres and nanosheets. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bian, X.; Luo, L.; Björklund, Å.K.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Gao, J.; Cao, C.; et al. Spatiotemporal single-cell roadmap of human skin wound healing. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 479–498.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.M.; Mouheb, L.; Rahman, A.; Agathos, S.N.; Dahoumane, S.A. Green nanotechnology-based zinc oxide (ZnO) nanomaterials for biomedical applications: A review. J. Phys. Mater. 2020, 3, 034005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.N.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, D.; Lee, J.B. Multifunctional hydrogel coatings for promoting angiogenesis and wound healing. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 8481–8488. [Google Scholar]

- Degli Esposti, L.; Carella, F.; Iafisco, M. Inorganic nanoparticles for theranostic use. In Electrofluidodynamic Technologies (EFDTs) for Biomaterials and Medical Devices: Principles and Advances; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 389–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Wound healing. In Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine; Laurent, G.J., Shapiro, S.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ruben, L.; López, J.A.; Barrera López, I.L.; Petricevich, V.L. Use of medicinal plants in the process of wound healing: A literature review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, F. Analysis of therapeutic effect of silver-based dressings on chronic wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.B.T.; Nguyen, T.N.T.; Ho, M.H.; Nguyen, N.T.P.; Do, T.M.; Vo, D.T.; Hua, H.T.N.; Phan, T.B.; Tran, P.A.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; et al. The efficacy of silver-based electrospun antimicrobial dressing in accelerating the regeneration of partial thickness burn wounds using a porcine model. Polymers 2021, 13, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nešporová, K.; Pavlík, V.; Šafránková, B.; Vágnerová, H.; Odráška, P.; Žídek, O.; Císařová, N.; Skoroplyas, S.; Kubala, L.; Velebný, V. Effects of wound dressings containing silver on skin and immune cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.K.H.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.C. Chitosan combined with ZnO, TiO2, and Ag nanoparticles for antimicrobial wound healing applications: A mini review of the research trends. Polymers 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.; Wood, F. Nanocrystalline silver dressings in wound management: A review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 1, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambonino, M.C.; Quizhpe, E.M.; Mouheb, L.; Rahman, A.; Agathos, S.N.; Dahoumane, S.A. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles in biomedical sciences: Properties, current trends, novel opportunities and emerging challenges in theranostic nanomedicine. Nanomaterials 2022, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes Bright, L.M.; Wu, Y.; Brisbois, E.J.; Handa, H. Advances in nitric oxide-releasing hydrogels for biomedical applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 66, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midwood, K.S.; Williams, L.V.; Schwarzbauer, J.E. Tissue repair and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Eom, I.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Gold nanoparticles: Synthesis and application in drug delivery. In Nanotechnology Applications in Health and Environmental Sciences; Dhanasekaran, D., Thajuddin, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.K.; Lee, D.S. Injectable biodegradable hydrogels. Macromol. Biosci. 2010, 10, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. VEGF and bFGF loaded injectable hydrogel for enhanced wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 4874–4884. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, X. Sprayable hydrogel for burn wound healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, S.; Shukla, V.K. Nanocomposite biosorbents for toxic metal removal. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, S4915–S4935. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.; Deshmukh, S.D.; Ingle, A.P.; Gade, A.K. Silver nanoparticles: The powerful nanoweapon against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeous, J.; AlSawaftah, N.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Husseini, G.A. Review of gold nanoparticles Synthesis, properties, shapes, cellular uptake, targeting, release mechanisms and applications in drug delivery and therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, K.K.; Thakur, K.; Ahluwalia, A.S.; Hashem, A.; Avila-Quezada, G.D.; Thakur, N. Assessment of genotoxicity of zinc oxide nanoparticles using mosquito as test model. Toxics 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J. Zinc oxide nanoparticles for skin wound healing: A systematic review from the perspective of disease types. Mater Today Bio. 2025, 34, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, K.R.; Koodali, R.T.; Manna, A.C. Size-dependent bacterial growth inhibition and mechanism of antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4020–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.R.; Singla, A.K.; Wadhawan, S.; Kaushik, R.; Kumria, A.; Bansal, K.; Dhawan, S. Chitosan microspheres as a potential carrier for drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 274, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.; Du, Q.; Wang, X. Injectable hydrogels for wound healing. Biomaterials 2020, 246, 119984. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, K. pH-responsive chitosan/alginate hydrogel for dual drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115231. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Li, L.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y. Smart hydrogel wound dressings with antibacterial and antioxidant functions. Acta Biomater. 2021, 124, 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyev, A.R.; Hasanova, U.A.; Israyilova, A.A. Development of a bentonite nanoparticle-based transdermal drug delivery system for burn wound infection prevention. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2025, 35, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, L. Adsorption of antibiotics tetracycline on supported attapulgite modified by cationic surfactant. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 828–832. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyev, A.; Israyilova, A.; Hasanova, U. Functionalization of silver-coated polypropylene meshes with bentonite, levofloxacin, and propolis for enhanced antibacterial protection in wound care. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2025, 35, 9221–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanova, U.A.; Aliyev, A.R.; Hasanova, I.R.; Gasimov, E.M.; Hajiyeva, S.F.; Israyilova, A.A. Functionalization of surgical meshes with antibacterial hybrid Ag@ crown nanoparticles. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2022, 17, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Dutta, J. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-bentonite nanocomposite films for wound healing application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C. Synergistic effect of magnetic bentonite/Ag nanocomposites for wound infection treatment: Antibacterial activity and wound healing evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121276. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Sun, L. Graphene oxide-based smart materials for wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26775–26784. [Google Scholar]

- Budovsky, A.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Ben-Shabat, S. Effect of medicinal plants on wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2015, 23, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.S.; Dalmasso, G.; Wang, L.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D.; Murthy, N. Orally delivered thioketal nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α siRNA target inflammation and inhibit gene expression in the intestines. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Byrska-Bishop, M.; Zhang, C.T. Stem cell membrane-coated nanoparticles for highly efficient in vivo cell targeting. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W.; Zhang, K.; Yue, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, H. AntihypoxamiR functionalized lipid nanoparticles improve neovascularization and wound healing in diabetic mice. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 3182–3191. [Google Scholar]

- Sideek, S.A.; Beshir, H.; Fares, A.R.; ElMeshad, A.N.; Elkasabgy, N.A. Different curcumin-loaded delivery systems for wound healing applications: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Nan, Z. Madecassoside-loaded liposomes accelerate skin wound healing: Preparation optimization and in vivo evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Nandhini, J. Nanomaterials for wound healing: Current status and futuristic frontier. Biomed. Tech. 2024, 6, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. Nanotechnology promotes the full-thickness diabetic wound healing effect of recombinant human epidermal growth factor in diabetic rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2010, 18, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.; Lim, D.W.; Choi, J. Assessment of size-dependent antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 763807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkowska-But, A.; Sionkowski, G.; Walczak, M. Influence of stabilizers on the antimicrobial properties of silver nanoparticles introduced into natural water. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, J.D.; Zhao, W.W.; Chu, L.; DeSilva, M.N.; Ghimire, A.; Rawls, H.R.; Whang, K. Antimicrobial acrylic materials with in situ generated silver nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012, 100, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Kanwal, Z.; Rauf, A.; Sabri, A.N.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S. Size- and shape-dependent antibacterial studies of silver nanoparticles synthesized by wet chemical routes. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]