Abstract

This study presents a systematic literature review of critical risk factors affecting the time and cost performance of highway construction projects. Drawing from 83 peer-reviewed studies across multiple geographic regions, the paper identifies recurrent drivers of project delay and cost overrun in highway construction. The most frequently reported risks include (1) financial constraints, (2) political regulatory issues; (3) land-acquisition and right-of-way delays; (4) design and scope changes; (5) utilities relocation/conflicts; (6) materials and equipment shortages; (7) contractor-related issues; (8) planning and scheduling weaknesses; (9) labour and personnel issues; and (10) weather conditions. These risk factors collectively highlight the importance of robust planning, proactive stakeholder coordination, and the integration of risk-informed decision-making tools. The findings emphasize the need for targeted risk mitigation during early project stages and provide a foundation for refining risk assessment frameworks and future research directions in transport infrastructure development.

1. Introduction

The construction of roads plays a pivotal role in developing a nation’s transportation system, serving as a fundamental component of economic infrastructure. Road networks and highways are essential for addressing national and regional socio-economic challenges, as their development and condition directly influence factors such as gross domestic product (GDP), price levels, and the efficient use of roads across economic sectors. As shown by Datta [1] for India’s Golden Quadrilateral where improved highways reduced firms’ input inventories by about one week of production and eased transport obstacles. Ghani, Goswami and Kerr [2] further show that for India’s Golden Quadrilateral, districts within 10 km of the upgraded highway experienced roughly 50% higher manufacturing output over the 2000–2009 period, driven by surging entry and post-entry scaling, alongside improved allocative efficiency and higher wages. As Pérez [3] highlights, transportation infrastructure acts as a critical link between production and consumption centres, making it indispensable to a country’s economic growth and stability. At the same time, highway project delivery is exposed to uncertainties across planning, procurement, and construction that frequently result in cost growth and schedule delays. Accordingly, guidance from the highway/transportation infrastructure industry, specifically TRB’s NCHRP Report 658, recommends addressing risk explicitly from the outset, integrated into project development and monitored throughout delivery [4].

However, the technical and operational condition of roads deteriorates over time due to various factors, including weather conditions, material aging, and increasing vehicle loads. (see FHWA [5]; Paterson [6]; Llopis-Castelló et al. [7]. With rising population demands and the subsequent growth in freight and passenger traffic, the need for strategic expansion, upgrading, and maintenance of road networks has become increasingly evident. Addressing these demands requires collaborative efforts between government and private partners as shown in global analyses, with illustrative evidence from the United States (GAO [8]; Mallett [9]). In addition, highway projects are inherently complex. Although Yang and Frangopol [10] develop their framework for civil infrastructure in general, they emphasise that the dynamic nature of the construction industry and the interdependence of multiple project components create high uncertainty requiring management throughout planning, design, construction, and operation. Highways, as linear, capital- and maintenance-intensive assets, demand substantial financial, material, and labour inputs over their full lifecycle, including planning and design, construction, rehabilitation/reconstruction, and routine maintenance, particularly under constrained budgets (OECD/ITF) [11].

In highway construction projects, uncertainties and risks arise at every lifecycle stage; systematic risk management is essential to maintain costs and quality and to achieve scheduled completion Vishwakarma et al. [12]. During the estimation stage, systematic risk identification and evaluation improve the treatment of uncertainty in cost prediction (Birnie & Yates) [13]. Furthermore, Zwikael and Ahn [14] show that project risk-management planning moderates the impact of risk on overall project success.

While risk-based thinking has yielded benefits, it also raises challenges and controversies that demand careful attention from decision-makers (Ball) [15]. In highway projects, complexity, scope change, and exposure to cost and schedule risk make risk management particularly demanding; accordingly, practitioners should identify, assess, and mitigate key risks and apply appropriate analysis tools throughout the project development process (TRB, NCHRP Report 658) [4].

According to ISO 31000:2018 [16], the risk-management process comprises risk assessment (identification, analysis, evaluation) and risk treatment (mitigation/response), with ongoing communication, consultation, monitoring, and review. This paper addresses the above challenges by conducting a systematic literature review to identify critical and frequently discussed risks affecting highway construction projects. This study develops a comprehensive taxonomy of highway-construction risk factors, identifies the principal risks reported in the global literature across diverse countries, and determines those most critical to project cost and schedule performance.

Research Objectives

The main objectives of Systematic Literature Review are:

- To identify and recommend a comprehensive classification system for risk factors associated with highway construction projects.

- To identify the key risk factors associated with highway construction projects.

- To determine the most critical risks affecting road/highway construction project cost and time performance.

2. Fundamentals of the Systematic Literature Review

2.1. Description of the Systematic Literature Review

This study employed a systematic literature review (SLR) drawing on the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre’s (EPPI-Centre) methodological guidance for evidence synthesis [17]. Reporting adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18]. The SLR was implemented using EPPI-Reviewer [19], the EPPI-Centre’s software developed at University College London (UCL), United Kingdom, to manage study records, conduct screening, and support data extraction and synthesis, thereby ensuring a transparent and systematic review process.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Methodology of SLR

The scope of this review was guided by well-defined conceptual frameworks, including relevant key concepts, synonyms, and free terms. To ensure extensive coverage of the subject matter, multiple sources were explored. These included: Electronic bibliographic databases, Internet search engines, Organization-specific websites, Physical copies of books and journals, Conference proceedings, Peer-reviewed journal papers, and Professional reports and scientific articles relevant to risk management, cost-time optimization, and risk assessment techniques in highway construction.

The references of each identified paper were also screened for further relevant studies to ensure completeness. Prior to screening and analysing the retrieved documents, all search results were imported into the EPPI-Reviewer 4 tool. This tool was instrumental in facilitating the systematic processes of screening, coding, storing, and synthesizing the collected data to generate comprehensive insights.

The review methodology followed a structured approach, broken into two primary stages:

- (1)

- Title/Abstract Screening: Initial screening of studies to identify relevance based on predefined criteria.

- (2)

- Full-Text Screening: Detailed review and synthesis of studies that met the inclusion criteria during the title/abstract screening phase.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the MMAT; the full MMAT Quality Appraisal Report for all 83 included studies is provided in the Supplementary Materials S2.

To ensure the systematic literature review was conducted effectively and transparently, a detailed and rigorous research protocol was developed. The protocol serves as a documented action plan, outlining the following elements:

- (1)

- Research Questions: Clearly defined questions guiding the review process.

- (2)

- Eligibility Criteria: Development of inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of selected studies.

- (3)

- Search Terms and Sources: Identification of relevant keywords, synonyms, and databases to comprehensively capture the literature.

- (4)

- Scope of the Review: Conceptual definitions and boundaries to ensure focus and coherence.

The full protocol including the detailed search terms used to generate the dataset for the systematic literature review is provided in Supplementary Material S1.

This systematic review was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) under DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KTWJG.

Search Question

This review seeks to address the following primary research question:

- What is the evidence supporting the use of risks management/optimisation (framework) in highway construction?

- What is the evidence supporting the use of risk optimization methods for highway construction?

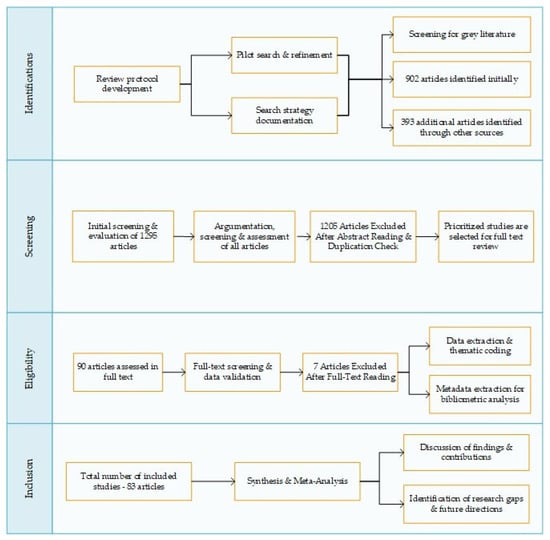

Summary of Figure 1: Literature Selection Process

Figure 1.

Search process of database—schematic diagram of the systematic literature review.

Figure 1 presents the schematic overview of the literature search and selection process employed in this review.

The process commenced with the identification of 1295 potential studies. After applying title/abstract screening, full-text eligibility assessments, and inclusion criteria, 83 studies were selected for detailed analysis.

2.2.2. Methodology of Identifying the Most Common Risk Factors in Highway Projects

The methodology adopted in this paper adheres to the SLR process particularly emphasizing structured data extraction and frequency-based analysis.

A total of 83 peer-reviewed studies were analysed using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were screened for relevance based on their empirical focus on risk factors in road and highway construction.

Each study was assessed for methodological rigor and categorized based on geographical regions, data collection method, and identified risk types. Frequencies were calculated to determine the most commonly cited risk factors.

The analysis of the most significant factors contributing to delays and cost overruns utilized the basic statistical concept of “frequency percentage.” As a result, the ranked list of frequently discussed risk factors is presented later in the Results (see Section 3). Additionally, calculations of percentage values based on the frequency analysis were performed for each significant factor.

To determine the prevalence of each factor within the reviewed literature, the frequency index was calculated using the formula below:

Frequency (%) = (Frequency of Occurrences/Total Number of Documents) × 100

2.2.3. Methodology for Producing the Recommended Classification Standard

The recommended risk-classification standard (presented later in the Results; see Section 3) was produced through a rules-based consolidation process. The approach was anchored to widely used guidance (ISO 31000 [16]; TRB’s NCHRP Report 658 [4]) and was also informed by prior highway/construction risk taxonomies reported in the literature. In particular, definitions and factor groupings were synthesised and harmonised from El-Sayegh and Mansour [20]; Hasina and Fazil [21]; Infrastructure Risk Group [22]; Nguyen et al. [23]; Deshpande and Valunjkar [24]; Heravi and Hajihosseini [25]; Msomba et al. [26]; Azhagarsamy et al. [27]; Sharaf and Abdelwahab [28]; and Ogbu and Adindu [29].

To ensure consistency, original risk labels were extracted verbatim from each eligible study, after which obvious synonyms and near-duplicates were combined. A single primary category by root cause was then assigned to each label, so that causes were prioritised over consequences. Where a label could plausibly belong to more than one category, simple tie-break rules were applied in this order: (i) cause before consequence (e.g., “delay in approvals” classified under Political/Regulatory rather than under scheduling effects); (ii) policy/regulatory action before administrative timing (e.g., “change in law” treated as Political/Regulatory rather than a generic management delay); and (iii) site/geotechnical before broad environment where subsurface or ground conditions were involved. Coding was conducted independently and then reconciled; any inconsistencies were resolved through discussion prior to finalisation. Through this protocol, a standards-informed and repeatable classification was achieved without altering the substantive meaning of the original sources.

3. Results and Analysis of Key Risk Factors

3.1. Classification of Highway Construction Risks

Consistent with established classifications, construction-project risks are commonly grouped into internal and external categories (Zhi [30]; Tah & Carr [31]; Aleshin [32]; El-Sayegh [20]. Internal risks include design and technical issues, managerial shortcomings, and stakeholder/communication problems (El-Sayegh) [20], whereas external risks encompass political instability, macroeconomic fluctuations, legal and regulatory constraints, and environmental and social pressures (Zhi) [30]. El-Sayegh and Mansour [33] distinguish between internal and external risks in highway projects, find internal risks to be more significant, and provide risk-allocation guidance assigning responsibilities to clients, contractors and consultants together with mitigation measures.

Effective risk management plays a pivotal role in enabling organizations to navigate uncertainties and enhance performance. The internationally recognized ISO standards for risk management serve as a robust framework for implementing effective strategies. These standards provide organizations with tools to better identify threats, monitor risks, and allocate resources efficiently, thereby increasing the likelihood of achieving project goals. However, given the dynamic nature of the construction industry, risk management strategies often require continuous improvement and adaptation to address evolving challenges.

3.1.1. Challenges in Risk Classification Across Literature

The classification of construction project risks and their sources has been extensively studied over the years, with numerous scholars contributing to its development

One of the most significant challenges in conducting a comprehensive review of highway construction project risks lies in the inconsistency in how risks are categorized across different sources. It is observed that the various studies adopt distinct (i.e., different) frameworks for classifying risks, often shaped by disciplinary focus, regional considerations, or project-specific factors. This lack of uniformity introduces ambiguity, especially for multi-dimensional risks that could feasibly belong to more than one category.

For example, Hasina & Fazil [21] classify expropriation/nationalization and permit/approval delays as Political, whereas El-Sayegh and Mansour [33] place analogous approval/NOC/right-of-way/expropriation delays under Technical

Similarly, in the Infrastructure Risk Group [22] framework, “adverse weather” is categorized as an external event under construction risk (implementation phase), reflecting its immediate disruptive impact on site activities. Studies such as Nguyen et al. [23] and Deshpande and Valunjkar [24] and align weather risk with construction-related challenges affecting site operations and scheduling. In contrast, Heravi and Hajihosseini [25] and Msomba et al. [26] classify severe weather conditions under force majeure, emphasizing its role as an exceptional event beyond human control. El-Sayegh and Mansour [33] and Azhagarsamy et al. [27]—treat weather as an environmental risk. This perspective situates weather within broader ecological and environmental frameworks, associating it with climate effects, sustainability considerations, and regulatory challenges, rather than immediate construction process disruptions.

This ambiguity underscores the need for a more flexible, source-independent classification model, especially when synthesizing findings from multiple sources. It also reinforces the importance of transparency in how researchers define and apply risk categories in literature reviews and empirical investigations.

To synthesise a varied literature, this paper first documents how prior studies classify risks and then proposes a harmonised taxonomy. This ordering clarifies sources of ambiguity and provides the rationale for the recommended scheme.

Table 1 presents 16 risk factor examples identified across multiple studies, along with the diverse categories they were associated with. The table clearly shows that there is the adoption of a local taxonomy of terms by different researchers, leading to ambiguity in how terms are defined and applied.

Table 1.

Examples of inconsistent categorisation of risk factors in the literature.

Within Table 1, the utilisation of the terms by the original authors has been considered in order to propose an unambiguous (or Standard) risk category definition. The first three columns report examples on how prior studies classify the risks, the subsequent columns identified a recommended “Standardised Category” (i.e., the causal or main driver) for each risk factor and the justifications for the selected category being classified as “The Standard” or not. Note: A “yes” in the “Standardised Category” column denotes a recommended primary classification. Any additional category listed for the same risk is secondary, indicating where the risk chiefly manifests or is administered (i.e., the main impact and operational responsibility).

For example: The repeated Risk Category Factor “16. Claims and disputes”. The Standard is recommended to be “Commercial/Contractual” as Claims and disputes concern the exercise or contestation of contract rights/obligations (time, money, scope, variations, extensions of time (EOTs), liquidated damages (LDs), payment).

3.1.2. Recommended Classification

Risk categories are analytically useful but not mutually exclusive, boundaries are porous because many hazards have multi-causal provenance and cut cross functions. Accordingly, each risk is classified by its primary driver (the root cause that determines responsibility and mitigation). Table 2 (“Recommended Classification”) sets out the categories with illustrative factors, providing a consistent basis for the analysis that follows.

Table 2.

Recommended Classification.

The recommended risk-classification scheme in Table 2 was developed by synthesising and harmonising risk taxonomies reported in prior studies, resolving overlapping terms, removing historical ambiguities, drawing on and reconciling definitions and factor groupings from El-Sayegh and Mansour [33]; Hasina and Fazil [21]; Infrastructure Risk Group [22]; Nguyen et al. [23]; Deshpande and Valunjkar [24]; Heravi and Hajihosseini [25]; Msomba et al. [26]; Azhagarsamy et al. [27]; Sharaf and Abdelwahab [28]; and Ogbu and Adindu [29]. In line with Section 2.2.3, Table 2 presents the recommended, rules-based classification that harmonises labels from the reviewed highway studies and assigns one primary category by root cause.

Note: Although this study focuses primarily on a systematic literature review of critical risk factors specific to highway construction projects, it is important to note that several references cited in Table 2 under the “Recommended Classification” pertain to risk classifications within general construction. For instance, Hasina and Fazil [24] address construction risk factors more broadly and are not limited to highway projects. These broader sources have been incorporated where relevant, given their contribution to understanding foundational risk categorization frameworks applicable across infrastructure sectors.

An additional point to consider is that Design-related risks may be treated either as a subset of technical and engineering risks or as a separate category, depending on the structure and level of detail adopted in the risk register. For smaller projects, design-related risks can be merged with technical risks under a single category of “Technical and Engineering Risks.” In the case of megaprojects, however, design risks are better maintained as a distinct category to ensure sufficient attention is given to their impact on project time and cost outcomes.

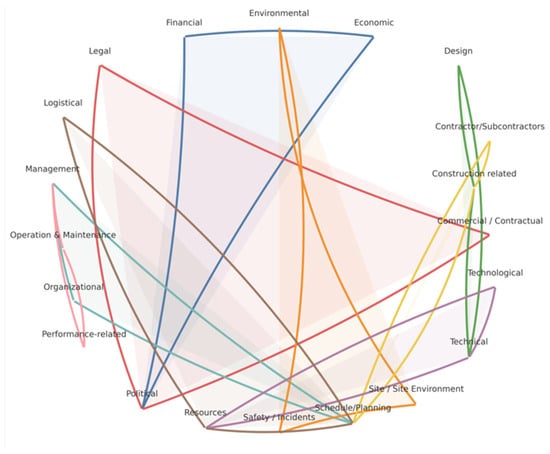

While Table 2 consolidates the classification scheme, it is neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. As illustrated in Figure 2, many risks can have multi-causal origins and manifest across functions, creating legitimate overlaps. To balance comparability with realism, each risk is assigned a primary classification determined by the main causal driver. Accordingly, Table 2 should be read as a baseline, extensible scheme, not a closed list; overlaps are expected and documented rather than treated as errors.

Figure 2.

Risk category overlap map.

Figure 2 visualises common overlaps among risk categories, showing only triadic overlaps as illustrative examples. Nodes represent categories, edges indicate frequently co-occurring pairwise links within each triad. (e.g., Financial–Economic–Political; Legal–Political–Commercial/Contractual; Management–Schedule/Planning–Organizational, Environmental–Site/Site–Environment–Safety/Incidents; Design–Technical–Construction related; Construction related–Schedule/Planning–Contractor/Subcontractors, Technical–Technological–Resources, Operation & Maintenance–Management–Performance-related, and Logistical–Resources–Schedule/Planning).

3.1.3. Identification of Critical Risks Associated with Time and Cost for Highway Construction

According to ISO 31000:2018 [16], risk identification is an iterative process of finding, recognizing and describing risks (including their sources, events, causes and potential consequences), with results recorded and reported as part of the risk-management process.

This section examines key aspects of the risk management framework, focusing on the identification of critical risk factors discussed by previous researchers and the existing risk assessment models applied in highway construction projects.

The comprehensive systematic literature review (Figure 1) resulted in the identification of 83 key articles. Table 3 presents key risk factors leading to highway and road construction project delay and cost overrun. (organised primarily by alphabetical country, then year).

Table 3.

Factors leading to highway and road construction project delay and cost overrun.

It can be seen from Table 3, that data within the literature is available for many countries, gathered over many years, with multiple key risk factors being identified. It should be noted that while Tran and Bypaneni [103] primarily focuses on analysing cost uncertainty as an aggregated risk outcome, rather than explicitly identifying discrete risk factors their work is cited here to acknowledge cost uncertainty as a significant aggregated risk factor impacting highway project outcomes.

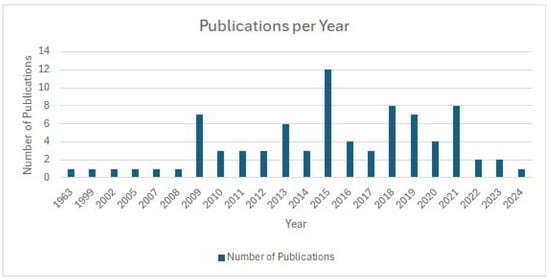

Figure 3 illustrates the global annual distribution of publications addressing risk factors in highway construction projects, based on the 83 reviewed studies included in this systematic review (Table 3). The trend highlights a significant increase in research output from 2009 onwards, with a notable peak in 2015. This growth reflects the expanding research attention towards identifying and managing risks affecting time and cost performance in highway construction across diverse geographic locations over the past two decades.

Figure 3.

Global distribution of reviewed publications on highway construction risk factors (1963–2024).

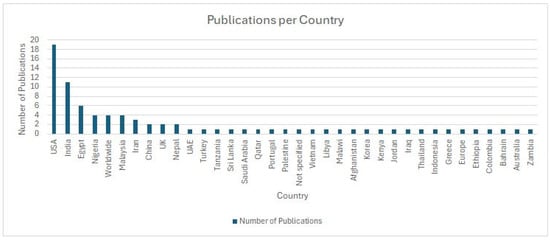

Figure 4 illustrates the geographic distribution of the analysed publications by country, based on the 83 studies summarised in Table 3. The figure highlights that research on highway construction risk factors spans a wide range of global regions, with the highest concentration of studies originating from the USA and India. Contributions from other regions such as Egypt, Nigeria, Malaysia and internationally scoped studies further reflect the global interest and diversity of perspectives addressing risk management in highway construction projects. The distribution in Figure 4 reflects how locations were reported by the source papers and is not used to weight the risk rankings; it documents publication coverage rather than the strength of effects by region.

Figure 4.

Geographic distribution of publications by country. Note: Countries are coded as reported by the original studies (Table 3). “Europe” denotes multi-country/region-level analyses within Europe; “Worldwide” covers cross-regional studies; “Not specified” indicates no location stated.

Figure 5 presents a global map showing the distribution of the reviewed publications by country, as summarised in Table 3. This map visually highlights the international scope of research addressing risk factors in highway construction projects. Notably, the highest concentrations of studies are seen in the USA and India, followed by significant contributions from China, Egypt, and Malaysia. The distribution underscores that while research attention is strongest in certain regions, the topic has attracted interest from a diverse range of countries worldwide.

Figure 5.

Global map of publications by country based on reviewed studies.

3.2. Key Risk Factors (Frequency Analysis)

This subsection reports the frequency analysis and ranking of risk factors contributing to delays and cost overruns in highway construction, based on 83 sources. Table 4 summarizes the 10 most frequently cited risks, their source references, frequency of occurrence, and proportional representation in the dataset.

Table 4.

Frequency and percentage of key risk factors in highway construction.

Among the 83 studies, the most frequently cited risks are Financial Issues (50.6%) and Design/Scope Changes & Errors (47.0%). A second cluster—Material Issues (37.3%), Contractor-Related Issues (33.7%), and Political/Regulatory (32.5%)—appears in roughly one-third of studies, with Land Acquisition Delays (30.1%) closing this ≥30% group. Mid-20% citations include Equipment Issues (26.5%), Utilities Relocation/Conflicts (25.3%), and Planning & Scheduling (24.1%). Labour/Personnel and Weather Conditions are joint 10th at 21.7% each.

4. Implications and Relevance of Findings

The identification of the most frequently cited risk factors (namely financial constraints design and scope changes, and material issues extends beyond academic interest and serves as a strategic resource for a wide range of industrial stakeholders involved in highway construction. For policymakers and government agencies, these findings highlight the need for institutional reforms in areas such as procurement processes, land acquisition protocols, and financial oversight mechanisms to enable simplification and/or de-risk activities in these areas. For project managers, engineers, and contractors, the results provide a prioritization framework that supports proactive risk planning, enabling more effective allocation of resources during the early project stages, where risk mitigation has the greatest influence on outcomes. Additionally, the recurring nature of external risks, such as adverse weather and bureaucratic inefficiencies, across diverse geographic regions signals the presence of deep-rooted systemic vulnerabilities that must be addressed through adaptive planning and governance innovations.

In short, these risks are the first things to consider when allocating budget and time. The ranked risks are intended to be used as a front-end checklist when planning highway projects. Project managers should seed the risk register from this list, assign owners, and time-phase contingency against the highest-ranked items. Public owners should size contingency and schedule float with these risks in mind and bring forward early actions (e.g., right-of-way, permitting, utility coordination). Contractors should reflect the same risks in pricing, programmes, and contract clauses.

Importantly, these findings are not merely retrospective; they serve as the foundation for future studies and risk modelling & simulation through unambiguously defining the terminology for classifying risks.

Risk Managers should ensure that they appropriately consider all 10 of the identified risks within highways projects.

Future work should utilise the insights gained from this literature review and frequently used factor to develop practical, targeted solutions for improving project delivery in the highway sector. These findings inform a computational model for budget and schedule planning, the model and results will be presented separately.

The following section briefly outlines the main limitations of this review and how the results should be interpreted in practice.

5. Limitations

This review provides a prioritised list of risks for highway projects, but several limits should be noted. The synthesis is based on published studies that vary in method and metrics, as a result, effect sizes are not directly comparable.

First, the ranking reflects how often risks are reported as “critical” in published studies; it does not estimate a single, comparable effect size across settings. The analysis relies on factors the original authors labelled “critical,” which may reflect local context and publication emphasis. Second, the included studies use different methods and measures, making direct comparison of impact strength difficult. Third, the recommended classification in Table 2 required harmonising labels across sources, a rules-based protocol was followed, yet some judgement was still involved. Fourth, findings reflect the contexts of the original studies (countries, delivery models, time periods), so some risks may be more important in certain settings than others. Fifth, the synthesis relies on published literature, which may over-represent topics that are more frequently studied or published in English. Sixth, no new primary data were collected; the results summarise what prior studies already identified as critical. Taken together, these limits mean the findings are best used for prioritising planning attention, budget, schedule, contingency, and early actions, rather than as universal impact coefficients.

6. Conclusions

This paper applied a systematic literature review methodology to identify the most critical risk factors contributing to project delays and cost overruns in highway and road construction. The most prevalent risk categories were found to be (1) financial constraints, (2) political regulatory issues; (3) land-acquisition and right-of-way de-lays; (4) design and scope changes; (5) utilities relocation/conflicts; (6) materials and equipment shortages; (7) contractor-related issues; (8) planning and scheduling weaknesses; (9) labour and personnel issues; and (10) weather conditions. These findings underline the need for targeted risk management strategies, particularly during the early phases of project planning and procurement. The data-driven evidence presented here provides a foundational basis for enhancing risk assessment models and informing policy and practice in infrastructure project management. Practically, the ranked risks in Table 4 are the first items to consider when allocating budget and time, sizing contingency and schedule float, and sequencing early actions (e.g., right-of-way, permitting, and utility coordination). For methodological qualifications, see Chapter 4 (Implications and Relevance of Findings) and Chapter 5 (Limitations).

When combined with our previous study (Zhasmukhambetova et al. [113]), the present analysis provides the empirical foundation for a predictive model that quantifies and forecasts project duration and cost by incorporating multidimensional risk factors. Future work will extend these combined results by applying the risk assessment and analysis techniques identified in Zhasmukhambetova et al. [113], and by developing, calibrating, and validating a model applicable to highway and road construction projects to improve risk understanding, quantification, risk-time-cost optimization and management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/futuretransp5040192/s1, Supplementary Material S1: Protocol to Systematic Literature Review. This file provides the full review protocol, including research questions, search strategy, databases searched, inclusion and exclusion criteria, screening procedure and data extraction form [114]. Supplementary Material S2: MMAT Quality Appraisal Report for 83 Included Studies. This file contains the MMAT design categories, item-level ratings (Q1–Q5) and the number of criteria met for each included study, together with a narrative summary and a traffic-light visualization of the overall appraisal results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and H.E.; methodology, H.E. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.E. and R.J.D.; supervision, H.E. and R.J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.Z. was supported by the Bolashak International Scholarship of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan for doctoral studies at the University of Birmingham, UK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KTWJG.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by the Bolashak International Scholarship of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, which enabled the pursuit of doctoral studies at the University of Birmingham.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Datta, S. The impact of improved highways on Indian firms. J. Dev. Econ. 2012, 99, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, E.; Grover, A.; Kerr, W. Highway to Success: The Impact of the Golden Quadrilateral Project for the Location and Performance of Indian Manufacturing. Econ. J. 2016, 126, 317–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Valbuena, G.J. La Infraestructura del Transporte vial y la Movilización de Carga en Colombia; Banco de la República: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.; Molenaar, K.; Schexnayder, C.; Transportation Research Board; National Cooperative Highway Research Program; Transportation Research Board. Guidebook on Risk Analysis Tools and Management Practices to Control Transportation Project Costs; NCHRP Report-658; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-309-28059-4. [Google Scholar]

- FHWA; Titus-Glover, L.; Darter, M.I.; Quintus, H.V. Impact of Environmental Factors on Pavement Performance in the Absence of Heavy Loads; Final Report FHWA-HRT-16-084; Infrastructure Research and Development Federal Highway Administration: McLean, VI, USA, 2019.

- Paterson, W.D.O. Road Deterioration and Maintenance Effects: Models for Planning and Management. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/222951468765265396/pdf/multi-page.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Llopis-Castelló, D.; García-Segura, T.; Montalbán-Domingo, L.; Sanz-Benlloch, A.; Pellicer, E. Influence of Pavement Structure, Traffic, and Weather on Urban Flexible Pavement Deterioration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highway Public-Private Partnerships. More Rigorous Up-Front Analysis Could Better Secure Potential Benefits and Protect the Public Interest, GAO-08-44; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Mallett, W.J. Public-private partnerships in highway and transit infrastructure provision. Highw. Constr. Manag. Maint. 2013, 149–177. Available online: https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL34567.html (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Yang, D.Y.; Frangopol, D.M. Life-cycle management of deteriorating civil infrastructure considering resilience to lifetime hazards: A general approach based on renewal-reward processes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 183, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwina Policies to Extend the Life of Road Assets. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/policies-extend-life-road-assets (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Vishwakarma, A.; Thakur, A.; Singh, S.; Salunkhe, A. Patil Institute of Engineering and Technology, Pimpri, Pune-411018 Risk Assessment in Construction of Highway Project. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2016, V5, IJERTV5IS020515. Available online: https://www.ijert.org/research/risk-assessment-in-construction-of-highway-project-IJERTV5IS020515.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Birnie, J.; Yates, A. Cost prediction using decision/risk analysis methodologies. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1991, 9, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwikael, O.; Ahn, M. The Effectiveness of Risk Management: An Analysis of Project Risk Planning Across Industries and Countries. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.J. The Evolution of Risk Assessment and Risk Management: A Background to The Development of Risk Philosophy. Arboric. J. 2007, 30, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 31000:2018; Risk Management—Guidelines. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd Edition). Psychol. Teach. Rev. 2017, 23, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Graziosi, S.; Brunton, J.; Ghouze, Z.; O’Driscoll, P.; Bond, M.; Koryakina, A. EPPI-Reviewer: Advanced software for systematic reviews. Maps Evid. Synth. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayegh, S.M. Risk assessment and allocation in the UAE construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasina, P.T.; Fazil, P. Risk Management in Commercial Building Construction using PESTEL and SWOT Analysis. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2021, 10, 812–816. [Google Scholar]

- Infrastructure Risk Group. Managing Cost Risk and Uncertainty in Infrastructure Projects. Available online: https://www.ice.org.uk/download-centre/managing-cost-risk-and-uncertainty-in-infrastructure-projects (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Nguyen, A.; Mollik, A.; Chih, Y.-Y. Managing Critical Risks Affecting the Financial Viability of Public–Private Partnership Projects: Case Study of Toll Road Projects in Vietnam. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 05018014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valunjkar, S. Identification of risks in Highway Projects and their Mitigation Strategies. In Proceedings of the ICACSE-2020, GCE KARAD and REC, Azamgarh, India, 24–25 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heravi, G.; Hajihosseini, Z. Risk Allocation in Public–Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects in Developing Countries: Case Study of the Tehran–Chalus Toll Road. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2012, 18, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msomba, Z.; Samson, M.; Ramadhan, S. Mlinga Identification of Crucial Risks Categories in Construction Projects in Tanzania. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2018, V7, IJERTV7IS020062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhagarsamy, S.; Dantuluri, V.; Anudeep, S.; Anuj, V.; Suriyakumaran, P.; Santhosheswar, M. Risk assessment in construction of highway project. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. 2021, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf, M.; Abdelwahab, H. Analysis of Risk Factors for Highway Construction Projects in Egypt. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2015, 9, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, C.P.; Adindu, C.C. Direct risk factors and cost performance of road projects in developing countries: Contractors’ perspective. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 18, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H. Risk management for overseas construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1995, 13, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tah, J.H.M.; Carr, V. A proposal for construction project risk assessment using fuzzy logic. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, A. Risk management of international projects in Russia. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 19, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayegh Sameh, M.; Mansour Mahmoud, H. Risk Assessment and Allocation in Highway Construction Projects in the UAE. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramek, A.; McCormack, T.; Est, P. Review Force Majeure Clauses Before Storms Hit. 2021. Available online: https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-419/knowledge/publications/ce1962e4/review-force-majeure-clauses-before-storms-hit (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Moore, J.P.V. Jackson Weathering the Storm—Part 3: Force Majeure in Construction Contracts. Available online: https://www.texasconstructionlawblog.com/2025/05/weathering-the-storm-part-3-force-majeure-in-construction-contracts/ (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- De Leon, G.P.; Darrell, D. Force Majeure Weather Modeling. In Proceedings of the PMICOS 2010 Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2–5 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lovells, H. Managing Extreme Weather-Related Delay and Disruption Claims on Projects. Available online: https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/managing-extreme-weatherrelated-delay-and-disruption-claims-on-projects?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Mastt. Everything to Know About Force Majeure Risk. Available online: https://www.mastt.com/risks/force-majeure (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Rivera, L.; Baguec, H.; Yeom, C. A Study on Causes of Delay in Road Construction Projects across 25 Developing Countries. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashal, Q. Delay Analysis of Road Construction Projects in Afghanistan. IJRAR 2013, 10, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Creedy, G.D.; Skitmore, M.; Wong, J.K.W. Evaluation of Risk Factors Leading to Cost Overrun in Delivery of Highway Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Suliman, S.M.A.; Malki, Y.A. An Investigation into the Delays in Road Projects in Bahrain. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. (IJRES) 2014, 2, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zayed, T.; Amer, M.; Pan, J. Assessing risk and uncertainty inherent in Chinese highway projects using AHP. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, Z.; Xi, J. Safety risk Assessment for Construction of Highway on Plateau Mountainous. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 643, 012188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D.; Rivera, L.; Orobio, A.; Cuadros, J. Evaluation of the impact of schedule risks in a road infrastructure project. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, R.F.; Abdel-Hakam, A.A. Exploring delay causes of road construction projects in Egypt. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 1515–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Maaty, A.E.; El-Kholy, A.M.; Akal, A.Y. Modeling schedule overrun and cost escalation percentages of highway projects using fuzzy approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, L.M.; Nabawy, M. Identifying key risks in infrastructure projects—Case study of Cairo Festival City project in Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2019, 10, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, A.M. Exploring the best ANN model based on four paradigms to predict delay and cost overrun percentages of highway projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 21, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, U.H.; Marouf, K.G.; Faheem, H. Analysis of risk factors affecting the main execution activities of roadways construction projects. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2023, 35, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubet, W.A.; Burrow, M.; Ghataora, G. Risks affecting the performance of Ethiopian domestic road construction contractors. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, N.; Costantino, N.; Gunnigan, L.; Pellegrino, R. Risk Management in Motorway PPP Projects: Empirical-based Guidelines. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, F. Delay Risk Assessment Models for Road Projects. Systems 2021, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.-S. Causes of Delay in Indian Transportation Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, E.R. Risk Assessment of BOT Road Projects. J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2013, 5, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkar, M.B.; Khandekar, S.D. Study of risk management for National Highway Project. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 2, 2146–2152. [Google Scholar]

- Honrao, Y.; Desai, D.B. Study of Delay in Execution of Infrastructure Projects—Highway Construction. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Makam, K.; Chappidi, H. Time and Cost Overrun Analysis of Highway Projects; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-659-75192-9. [Google Scholar]

- Vasishta, N.; Chandra, D.S.; Asadi, S. Analysis of Risk Assessment in Construction of Highway Projects Using Relative Importance Index Method. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Thombare, M.K.; Ambre, H. Risk Management in BOT PNG Toll Plaza. IRJET 2019, 6, 6324–6329. Available online: https://www.irjet.net/archives/V6/i5/IRJET-V6I5877.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Rajput, B.L. Risk Factors Causing Cost Overrun in Highway Construction Projects; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Danisworo, B.; Latief, Y. Estimation model of Jakarta MRT phase 1 project cost overrun for the risk based next phase project funding purpose. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 258, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapanont, P.; Santi, C.; Pruethipong, X. Causes of delay on highway construction projects in Thailand. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 192, 02014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Azaron, A.; Mojtahedi, S.M.H.; Hashemi, H. Risk assessment for highway projects using jackknife technique. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5514–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Ravanshadnia, M.; Nobakht, M.B. A Survey of Risks in Public Private Partnership Highway Projects in Iran. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2014, Kunming, China, 18 November 2014; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VI, USA; pp. 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanger, Q.K. Important Causes of Delay in Construction Projects in Baghdad City. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazim, N.; Abusalem, Z. Delay and cost overrun in road construction projects in Jordan. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2015, 4, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atibu Seboru, M. An Investigation into Factors Causing Delays in Road Construction Projects in Kenya. Am. J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, M.A.; Kim, B.-S. Assessment of Risk Impact on Road Project Using Deep Neural Network. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfakhri, A.Y.Y.; Ismail, A.; Khoiry, M.A.; Arhad, I.; Irtema, H.I.M. A Conceptual Model of Delay Factors Affecting Road Construction Projects in Libya. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 12, 3286–3298. [Google Scholar]

- Kamanga, M.J.; v d M Steyn, W.J. Causes of delay in road construction projects in Malawi. J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2013, 55, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Ghazali, F.E. Operational Risks for Highway Projects in Malaysia. Proc. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2009, 41, 364–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wafa, S.M.F.; Singh, B. Delays in Road Construction Projects in the State of Perak. Constr. Manag. Transp. 2016, 2, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran, S.; Ramli, M.Z.; Malek, M.A.; Musir, A.A.; Imran, N.F.; Fuad, N.F.S.M.; Zawawi, M.H.; Zainal, M.Z. Causes of Delay on Highway Construction Project in Klang Valley; AIP Publishing LLC.: Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 2018; p. 020242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, P.Z.; Ali, M.I.; Ramli, N.I. Ahp-Based Analysis of the Risk Assessment Delay Case Study of Public Road Construction Project: An Empirical Study. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 14, 875–891. [Google Scholar]

- Manavazhi, M.R.; Adhikari, D.K. Material and equipment procurement delays in highway projects in Nepal. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaiN, H. Impact of Risk Management Practice on Success of Road Construction Project. Smart J. 2021, 7, 3467–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Awotunde, G. An Evaluation of Risk Impacting Highway and Road Construction Projects in Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Construction and Real Estates Management (ICCREM 2010) ‘Leading Sustainable Development through Construction and Real Estates Management’, Brisbane, Australia, 1–3 December 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekung, S.; Adeniran, L.; Adu, E. Theoretical Risk Identification Within the Nigeria East- West Coastal Highway Project. Civ. Eng. Urban Plan. 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fabi, J.K.; Awolesi, J.A.B. A Study of Risk Management Practice of Highway Projects in Nigeria. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 6, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelidis, L. A critical review of highway slope instability risk assessment systems. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2011, 70, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, I. Common risks affecting time overrun in road construction projects in Palestine: Contractors’ perspective. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build. 2013, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.O.; Marques, R.C. Risk-Sharing in Highway Concessions: Contractual Diversity in Portugal. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2013, 139, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, H.; Farrell, P.; Abdelaal, M. Causes of Delay on Large Infrastructure Projects in Qatar. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ARCOM Conference, Lincoln, UK, 7–9 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elawi, G.S.A.; Algahtany, M.; Kashiwagi, D. Owners’ Perspective of Factors Contributing to Project Delay: Case Studies of Road and Bridge Projects in Saudi Arabia. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, J.M.; Wang, J.; Zou, P.X.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, R. Fuzzy Logic–Based Method for Risk Assessment of Belt and Road Infrastructure Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, B.A.K.S. Risk Management in Road Construction: The Case of Sri Lanka. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2009, 13, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.E.; Köseoğlu, E. Risk Analysis Application in Highway Projects. Düzce Üniversitesi Bilim Ve Teknol. Derg. 2021, 9, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, R.; Udeaja, C.; Fong, D.; Chen, Y. A Risk Analysis of Construction Projects Delay Factors in the United Kingdom. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Leadership and Management of Projects in the Digital Age (IC:LAMP), Eker, Bahrain, 27–28 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, P. Project delivery performance: Insights from English roads major schemes. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2024, 5, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunow, R.N. PERT and Its Application to Highway Management. In Highway Research Record; National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Vidalis, S.M.; Najafi, F.T. Cost and time overruns in highway construction. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering—30th Annual Conference: 2002 Chellenges Ahead, CSCE 30th Annual Conference Proceedings, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5–8 June 2002; pp. 2799–2808. [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar, K.R. Programmatic Cost Risk Analysis for Highway Megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, N.; Shinozuka, M.; Moore, J.E.; Chang, S.E.; Kameda, H.; Tanaka, S. System Risk Curves: Probabilistic Performance Scenarios for Highway Networks Subject to Earthquake Damage. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2007, 13, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gransberg, D.D.; Riemer, C. Impact of Inaccurate Engineer’s Estimated Quantities on Unit Price Contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Madanu, S. Highway Project Level Life-Cycle Benefit/Cost Analysis under Certainty, Risk, and Uncertainty: Methodology with Case Study. J. Transp. Eng. 2009, 135, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, N.G.; Shirazi, H. Risk-Based Model for Pricing Highway Infrastructure Warranties. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2009, 15, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Caldas, C.H.; Gibson, G.E.; Thole, M. Assessing Scope and Managing Risk in the Highway Project Development Process. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Labi, S.; Sinha, K. Development of a Framework for Ex Post Facto Evaluation of Highway Project Costs in Indiana; FHWA/IN/JTRP-2009/33; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2011; p. 3012. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, K.C.; Shane, J.S. Risk Mitigation Strategies for Operations and Maintenance Activities; Institute for Transportation Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2012; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasopoulos, P.C.; Labi, S.; Bhargava, A.; Mannering, F.L. Empirical Assessment of the Likelihood and Duration of Highway Project Time Delays. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.Q.; Molenaar, K.R. Impact of Risk on Design-Build Selection for Highway Design and Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 30, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.S.; Blasier, K.; Aoun, D.G. Risk Misallocation on Highway Construction Projects. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2015, 7, 04515002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Bypaneni, S. Impact of Correlation on Cost-Risk Analysis for Construction Highway Projects. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2016; San Juan, PR, USA, 24 May 2016; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VI, USA; pp. 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, M.F.; Varma, A.; Panthi, K. Modeling the Construction Risk Ratings to Estimate the Contingency in Highway Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bypaneni, S.P.K.; Tran, D.Q. Empirical Identification and Evaluation of Risk in Highway Project Delivery Methods. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Nova, I.; Gad, G.M.; Touran, A.; Cetin, B.; Gransberg, D.D. Evaluating the Influence of Differing Geotechnical Risk Perceptions on Design-Build Highway Projects. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2018, 4, 04018038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.V.; Calahorra-Jimenez, M.; Molenaar, K.R.; Torres-Machi, C. Challenges in Engineering Estimates for Best Value Design–Build Highway Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummalapudi, M.; Harper, C.M.; Taylor, T.R.B.; Waddle, S.; Catchings, R. Causes, Implications, and Strategies for Project Closeout Delays in Highway Construction. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2022, 2676, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T I Lam, P. A sectoral review of risks associated with major infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1999, 17, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliba, C.; Muya, M.; Mumba, K. Cost escalation and schedule delays in road construction projects in Zambia. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanto, I.N.; Purba, A. A Systematic Review and Analysis of Risk Assessment in Highway Construction Projects. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theor. Appl. 2020, 3, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhasmukhambetova, A.; Evdorides, H.; Davies, R.J. Integrating Risk Assessment and Scheduling in Highway Construction: A Systematic Review of Techniques, Challenges, and Hybrid Methodologies. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).