1. Introduction

Traffic congestion is a growing challenge worldwide, with negative impacts on the economy, the environment, and public health. In high and middle-income countries, such as India [

1] and Iraq [

2], this phenomenon is characterized by high rates of accidents and traffic jams. In Latin America, the situation is particularly critical in medium-sized cities where the constant growth of the vehicle fleet has exacerbated mobility problems in the context of limited road infrastructure and control systems.

In Colombia, the most recent statistics indicate that 1,016,554 vehicles were sold in 2024, representing a 17.54% increase compared to 2023. At the departmental level, 31,170 vehicles were registered in Córdoba, equivalent to a 13.66% increase [

3,

4]. Although official figures for motorcycles in Montería are not available, the 1629 cars registered represent a 2.80% increase over the previous year [

3]. These data indicate sustained growth in the vehicle fleet in medium-sized cities, where the lack of adaptive traffic light systems worsens congestion.

Although traditional traffic lights remain the primary traffic management mechanism globally, their fixed timing intervals do not adapt to the variability of traffic flow [

5,

6]. This limitation creates inefficiencies during peak hours, resulting in increased congestion, pollution, travel time, and driver stress.

As a solution, smart traffic lights have established themselves as a more efficient alternative as they utilize technologies capable of managing traffic in real time. Among these, computer vision stands out for processing images and videos using high-performance hardware and specialized algorithms, thus enabling the identification of mobility patterns [

7]. Therefore, deep learning-based detection models, such as the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family, have shown promising results in urban applications [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In this context, the overall objective of this study is to comparatively evaluate the performance of YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 in vehicle detection and classification in the urban environment of Montería, without directly implementing an intelligent traffic light system. To this end, three specific objectives are proposed: (i) to evaluate the impact of lighting variability on the performance of each model; (ii) to compare standard computer vision metrics (mAP@0.5, precision, and recall); and (iii) to identify the strengths and limitations of each architecture as input for future adaptive traffic light systems.

The novelty of this research can be summarized as follows:

Real-world dataset construction: A new dataset was collected under actual traffic and environmental conditions in Montería, incorporating lighting variability and vehicle diversity—representing a unique, replicable resource for medium-sized Latin American cities.

Comparative evaluation under real conditions: Unlike prior studies focused on large metropolitan or simulated settings, this study performs a controlled comparative analysis of YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 in real urban environments of a developing city context.

Integration of statistical rigor: The analysis introduces standard deviation and significance tests to assess whether observed performance differences are statistically meaningful—an aspect rarely explored in previous YOLO-based studies.

Applied contribution to smart mobility: Findings provide practical evidence for the design of adaptive traffic light and monitoring systems, emphasizing the robustness of YOLO architectures under diverse lighting and weather conditions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review;

Section 3 describes the methodology;

Section 4 presents the results and discussions; and

Section 5 presents the conclusions and future lines of research.

2. Related Works

Deep learning architectures for vehicle detection have evolved toward greater precision, speed, and robustness. Object detection constitutes a central component of scene understanding, as it provides the foundation for recognizing and localizing multiple elements within complex environments. Classical scene understanding models typically rely on semantic segmentation, instance segmentation, or contextual reasoning frameworks that integrate object detection into a holistic interpretation of urban scenes [

14]. Within this context, detection algorithms such as YOLO offer a fast and efficient solution, enabling real-time perception that bridges the gap between low-level visual recognition and high-level situational awareness [

15]. This relationship reinforces the relevance of detection tasks as the first and most critical step in intelligent transportation and urban monitoring systems.

Early implementations of YOLO in smart city and transportation systems include studies such as [

8], which applied YOLOv2 for vehicle detection and classification (car, motorcycle, truck, and bus) in a major metropolitan area. The authors evaluated the model using mean Average Precision (mAP), achieving 60.63%. Similar studies using YOLOv3 for real-time vehicle detection in controlled environments achieved high precision (97.5–98.1%) and recall (76.5–98.5%), confirming the model’s strong performance under ideal conditions [

16,

17]. However, when applied to real-world traffic scenarios, YOLOv3’s metrics decreased substantially (precision = 63%, recall = 55%, mAP = 46.6%) [

18], evidencing the challenges posed by uncontrolled illumination, occlusions, and congestion. Subsequent studies maintained this real-environment focus, extending evaluations beyond laboratory or simulated settings to urban contexts characterized by dynamic lighting and heterogeneous traffic flow.

In these conditions, later models such as YOLOv5 [

19] showed significant performance gains, achieving 72% precision and 65.2% recall, with an F1-score of 68% and a mAP of 67.4%. Similarly, YOLOv8 [

20] incorporated enhanced feature extraction, multiscale detection, and anchor-free design, reaching 88.5% precision and 77% recall under uncontrolled lighting conditions. Recent comparative analyses under variable environmental and operational factors, including brightness changes, rainfall, and traffic density, confirmed that performance can fluctuate even among state-of-the-art models [

21,

22]. These findings underscore the importance of real-world datasets that capture such diversity to ensure ecological validity and reproducibility.

Beyond vehicle detection, YOLO architectures have been applied in real urban environments for complementary monitoring tasks such as crack and fatigue analysis of concrete in urban infrastructure [

9], waste management [

11] and road damage detection [

12]. These studies further demonstrate how object detection contributes not only to traffic management but also to broader scene-understanding processes in smart cities, reinforcing the algorithm’s adaptability across real-world applications [

23]. Nevertheless, most existing comparative works emphasize accuracy alone, often neglecting statistical validation or robustness under dynamic conditions—gaps that this study directly addresses through a quantitative and statistically supported evaluation of YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 in real traffic environments.

In summary, previous works demonstrate the progressive improvement of YOLO architectures but reveal limited exploration under real-world traffic conditions with environmental variability. This study fills that gap by systematically comparing YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 using real urban data collected under different weather and lighting conditions, thereby linking vehicle detection performance with scene understanding and intelligent mobility system design.

3. Materials and Methods

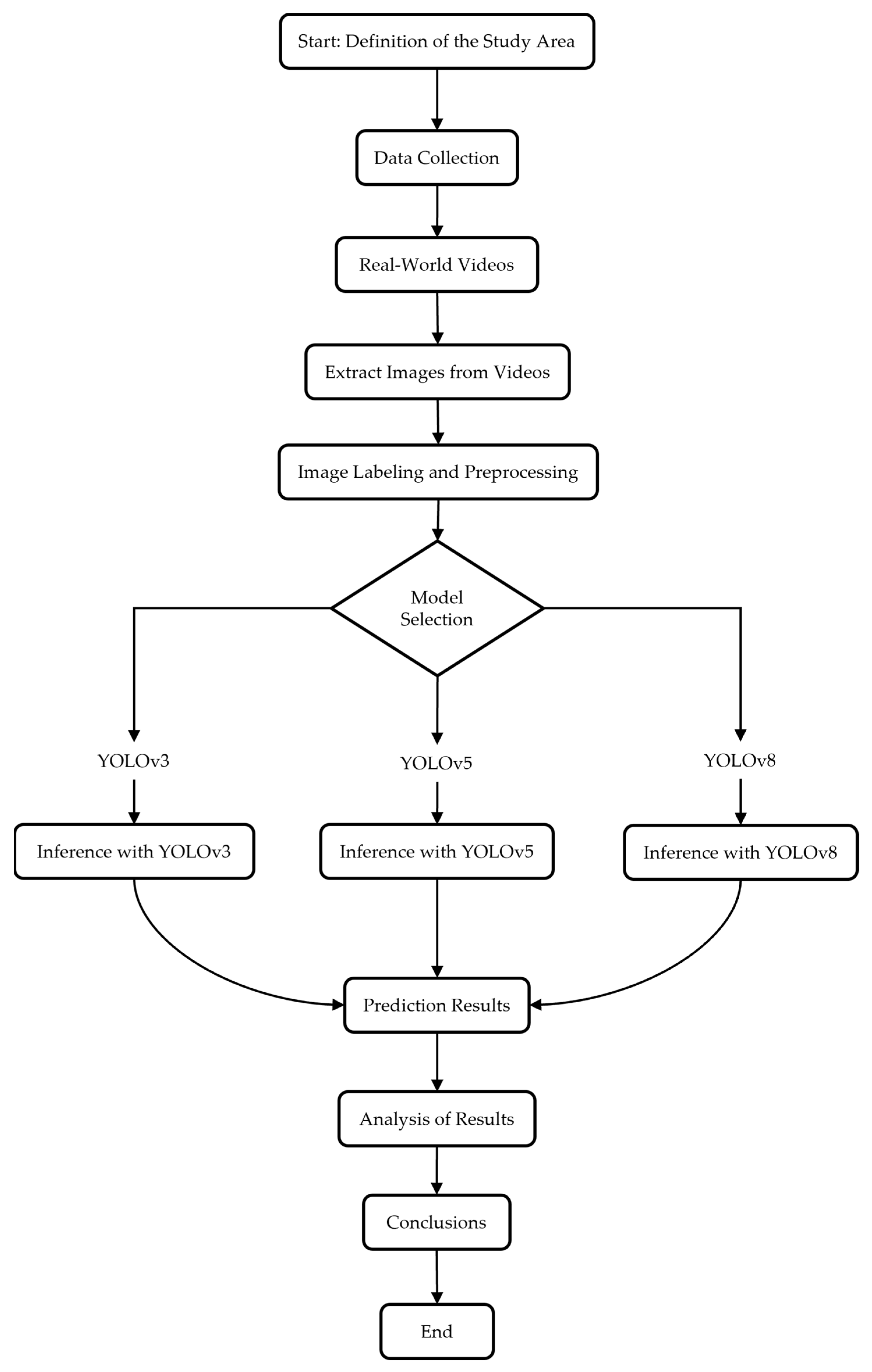

The methodological framework adopted in this study is summarized in

Figure 1. It was designed to ensure a coherent and transparent workflow that integrates all stages of the experimental process, from data acquisition to performance validation. The workflow consists of (1) definition of the study area; (2) collection of real traffic data in the city of Montería; (3) image labeling and preprocessing; (4) model selection and inference using YOLOv3, YOLOv5 and YOLOv8; and (5) analysis of results and conclusions.

3.1. Study Area

The study area corresponds to the intersection of Calle 44 and Avenida Circunvalar in Montería (Colombia), which was selected due to its high traffic density during peak hours and the availability of fixed security cameras that allow continuous recording of traffic flow. This intersection is a critical point within the urban road network, as it connects residential and commercial areas of the city. Its location is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.2. Data Collection

The video recordings were provided by the Montería Traffic and Mobility Secretariat, which is responsible for managing the security cameras located at the selected intersection. Access to this content was granted strictly for academic and research purposes, ensuring confidentiality and responsible use of the information.

The dataset consisted of recordings obtained over five consecutive days in three time slots (morning, midday, and afternoon), corresponding to the periods of highest traffic flow—peak congestion hours. This temporal sampling strategy enabled the capture of scenarios with maximum congestion and variability in lighting conditions. Additionally, data acquisition intentionally covered different weather scenarios—including sunny, cloudy, and light rain periods—to ensure representativeness of real-world variations in visibility and lighting. The recordings had a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, a sampling frequency of 30 FPS, MP4 format, and a duration of 5 min per time slot, for a total of 15 min of recording per day. This design resulted in a total of 75 min of analyzed video, corresponding to peak hours—when urban traffic flow is at its highest—which provided sufficient diversity of environmental and operational conditions to evaluate the robustness of the models. Instead of emphasizing dataset size, the sampling prioritized realistic high-density periods, thereby maximizing ecological validity and ensuring that the evaluated scenarios reflected the most critical operating conditions for intelligent traffic management applications. Subsequently, the various environmental conditions were analyzed separately to assess each model’s robustness under different visibility and lighting factors.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

During preprocessing, the frames were standardized to a resolution of 416 × 416 pixels for YOLOv3, and 640 × 640 pixels for YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, in accordance with the default configurations of each architecture. These resolutions were maintained to ensure optimal feature extraction within each model’s native receptive field and to preserve comparability. To avoid distortions in the detected objects, the aspect ratio was maintained using padding (letterboxing). Subsequently, the images were normalized to enhance the model’s interpretation of features. Finally, inference thresholds were established: a minimum confidence level of 50% to balance precision and recall, an Intersection over Union (IoU) value of 50% to handle overlaps, and a non-maximum suppression (NMS) threshold of 50% to eliminate redundancies and ensure consistency in the results.

3.4. Detection Models

The selected models were YOLOv3 [

24], YOLOv5 [

25], and YOLOv8 [

26], all in their pre-trained versions using the COCO dataset, which contains more than 80 object categories [

27]. These versions were chosen because of their improvements in speed and precision compared to previous implementations such as YOLO [

28] and YOLOv2 [

29], which makes them particularly suitable for vehicle detection and classification scenarios in real traffic conditions.

No training or fine-tuning process was conducted in this study, as the objective is to directly evaluate the performance of the pre-trained models in real conditions in the city of Montería. This decision allows us to isolate the intrinsic generalization capacity of each architecture, without introducing biases derived from retraining on the local dataset. All YOLO versions were evaluated in deterministic inference mode using their official pretrained weights. As a result, inference outcomes are fully reproducible.

These three versions (YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8) were selected because they represent key evolutionary milestones within the YOLO family while belonging to the same standardized Ultralytics development ecosystem. This methodological choice ensures full comparability and reproducibility, as all models share consistent training, inference, and evaluation standards. Versions 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12–20 were excluded since they were developed by independent research groups with different frameworks, which could introduce unwanted variability in performance comparisons. YOLOv3 was retained as the anchor-based baseline, YOLOv5 as the mature and optimized reference model with CSPNet and PANet, and YOLOv8 as the consolidated state-of-the-art, anchor-free version. Although version 11 is also developed by Ultralytics, it remains under optimization and was therefore excluded to ensure experimental stability.

Model Architecture

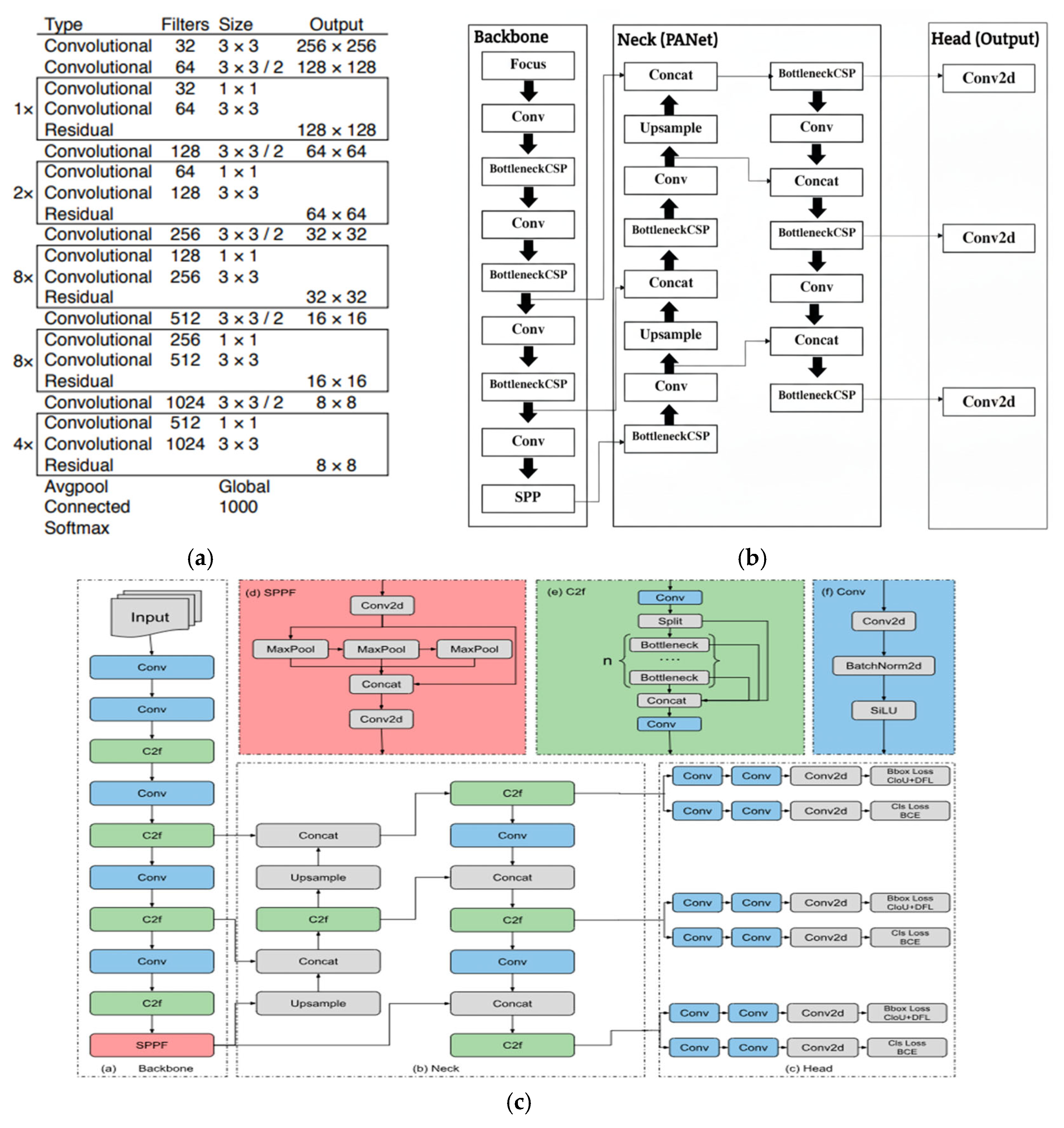

The YOLOv3 algorithm incorporates a feature extraction network based on YOLOv2’s Darknet-19 but optimized and renamed Darknet-53 [

30]. This architecture consists of successive blocks with 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 filters, enabling efficient feature extraction and object detection [

31]. It also draws inspiration from the ResNet structure, taking it as a reference, increasing the number of layers to 53 with a direct connection. Compared to Resnet-152 [

32], Darknet-53 is less deep, although it maintains a very similar accuracy rate and is approximately twice as fast.

YOLOv5 marked a significant transition within the model family, as it was implemented in PyTorch (v2.7.1, CUDA 11.8), facilitating its training, deployment, and adoption in various environments. Its architecture is organized into three main components: Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone uitlizes CSPDarknet53, which incorporates BottleneckCSP blocks to improve gradient flow, reduce redundancy, and extract more representative features [

33]. In the Neck, YOLOv5 integrates PANet (Path Aggregation Network), which promotes bidirectional information propagation and the construction of robust feature pyramids for multiscale detection [

34]. This structure enhances the model’s ability to recover fine-grained spatial details and mitigates the impact of small localization errors or outlier detections by improving feature fusion across scales. Finally, the Head maintains the classic YOLO structure, generating multiscale predictions that include bounding boxes, confidence scores, and class probabilities [

35]. These optimizations allow this model to achieve a better balance between inference speed and precision compared to previous versions.

The architecture of YOLOv8 maintains the same division into Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone, based on CSPDarknet53, is responsible for extracting features from the input images, using convolutional layers and cross-stage partial (CSP) connections to learn hierarchical representations [

36] efficiently. Noteworthy modules include C2f (CSP Concatenation and Feature Fusion), inspired by DenseNet, which improves feature fusion and reduces computational complexity [

37,

38], and SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling–Fast), which expands the receptive field and facilitates the handling of objects of different sizes [

39,

40].

The Neck utilizes the Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN) to reinforce feature propagation between different scales, optimizing the detection of objects of various sizes [

34]. Unlike PANet in YOLOv5, PAFPN introduces more efficient downstream and upstream pathways, improving gradient flow and robustness against outliers, especially in dense urban traffic scenes. Finally, the Head makes final predictions, including bounding box coordinates and class probabilities, and incorporates decoupled structures and advanced loss functions such as CIoU and DFL, improving precision in box regression and classification [

36]. These innovations make YOLOv8 more efficient and accurate, especially in scenarios with small objects and complex traffic conditions.

Figure 3 schematically illustrates these three architectures, highlighting their progressive evolution.

3.5. Implementation Environment

The implementation was carried out in Python (v3.12), using computer vision and deep learning libraries such as PyTorch (v2.7.1, CUDA 11.8), Ultralytics, OpenCV, and NumPy. These tools facilitated model loading, image processing, and the execution of the detection routine execution.

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 computer equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (6 GB VRAM), 16 GB of RAM, and an 11th generation Intel Core i7-11800H processor. This hardware configuration enabled us to process video sequences efficiently, ensuring smooth implementation of the analyzed models.

3.6. Performance Evaluation

3.6.1. Ground Truth

To validate the models, a manual image labeling process was implemented using images obtained from the original videos. To ensure representativeness without incurring excessive computational load, systematic sampling was applied, consisting of extracting one frame every two seconds. In this way, each time slot provided 150 images, resulting in a total of 450 images per day and 2.250 images for the five days of recording.

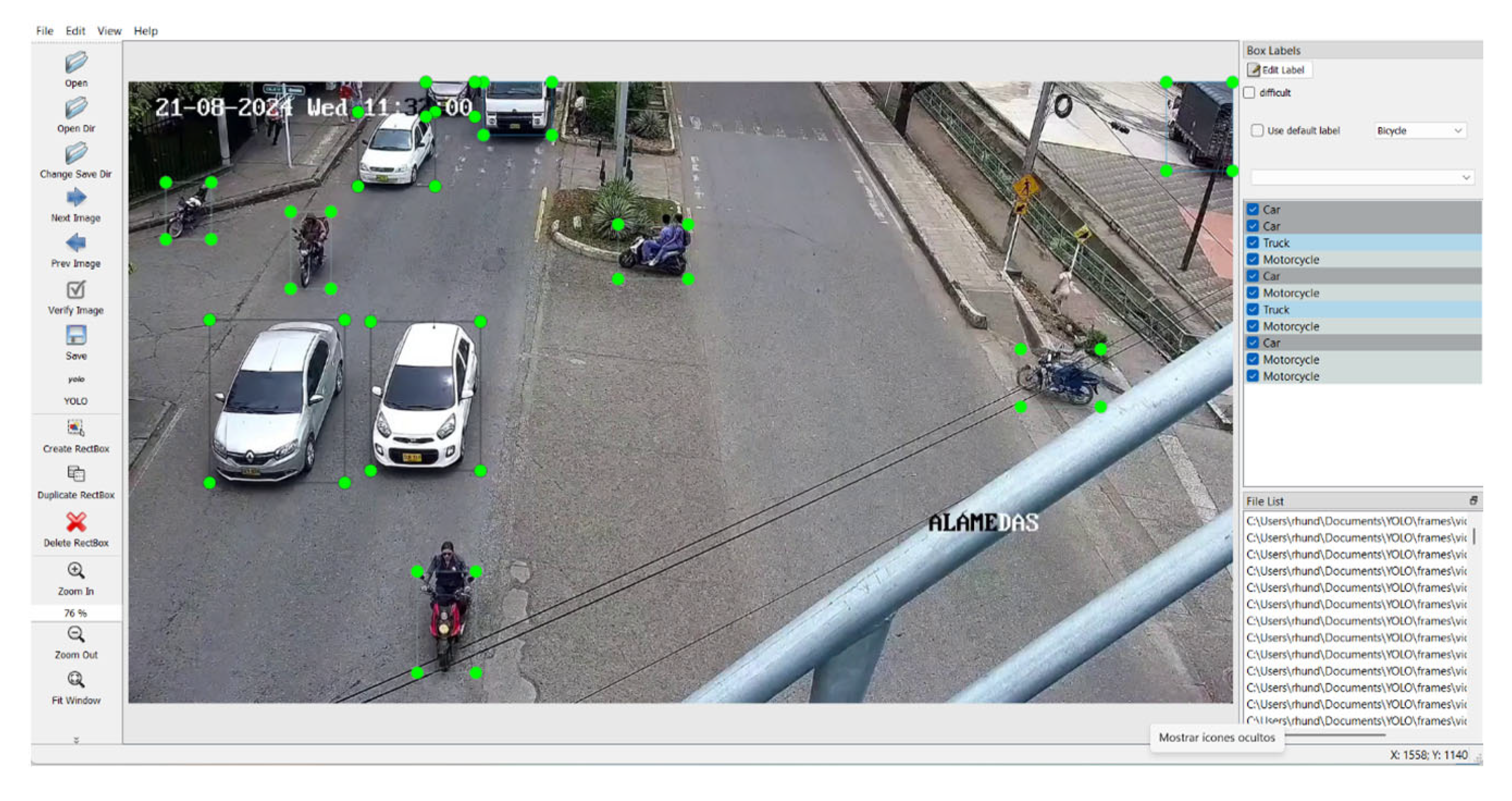

The labeling was performed using the LabelImg tool (1.8.6+), considering five representative vehicle categories in urban mobility: cars, buses, trucks, motorcycles, and bicycles. This process was carried out by a single observer, following consistent annotation criteria in terms of: precise delimitation of detection boxes, assignment of correct labels to each category, and quality control through subsequent cross-checking to rule out obvious errors.

The final distribution of instances by category is presented in

Table 1, which shows a greater predominance of cars and motorcycles, followed by a smaller representation of bicycles, trucks, and buses.

Finally,

Figure 4 presents an illustrative example of the annotation process, showing the bounding boxes applied to a subset of images from the dataset. The generated label sets constituted the ground truth of the study and served as an objective basis for comparison with the outputs of the pre-trained YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 models.

3.6.2. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the models was evaluated using a set of metrics widely used in object detection and classification tasks. Precision [

42] and recall [

43] were calculated, metrics that allow the model’s behavior to be analyzed in terms of false positives and false negatives. From these two, the F1-score [

44] was derived, which balances the analysis when there is an imbalance between the two metrics.

Additionally, the mAP (mean Average Precision) metric was considered, recognized as the benchmark standard for evaluating detection models, having been introduced in the Pascal VOC challenge [

45] and subsequently consolidated in the COCO evaluation framework [

27]. This metric provides a comprehensive view of the model’s performance across multiple classes and confidence thresholds, making it a robust tool for comparing architectures.

To complement the performance evaluation, a statistical significance analysis was performed to determine whether the differences observed between YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 were statistically significant. The analysis considered the values obtained in all vehicle categories for each model. To this end, an ANOVA test using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) was applied to assess the existence of significant differences in average performance, adopting a significance level of α = 0.05.

This design was selected because, given that the models operate under a deterministic inference process, multiple runs produce identical results. This allows each vehicle category to be treated as a block and each model as a treatment, obtaining a single representative value per block. This structure makes the RCBD particularly appropriate, as it takes into account variability between classes while isolating the effect of the model architecture.

In addition, to quantify the influence of qualitative factors, a two-factor design was implemented, considering the detection model and the environmental conditions of the study as fixed factors, and using the primary evaluation metric AP obtained from each video as the response variable. This allows for the evaluation of possible interactions between the model architecture and external conditions that may affect detection performance.

The assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances, and independence of observations were verified to ensure the validity of the ANOVA. Normality and homogeneity were verified using the Shapiro–Wilk and Bartlett tests, respectively, while independence was ensured by randomly assigning treatments in both the RCBD and the two-factor design. In cases where any of the assumptions were not met, a Box–Cox transformation was applied to stabilize the variance and approximate normality in the residuals, thus maintaining the robustness of the statistical inference. If, after transformation, the assumptions are still not met, a nonparametric analysis based on the aligned rank transformation (ART) procedure is applied. This method allows the main and interaction effects in between-subjects factorial designs to be tested without requiring normality or homoscedasticity, providing a statistically valid alternative to traditional ANOVA in non-compliant conditions.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Overall Performance

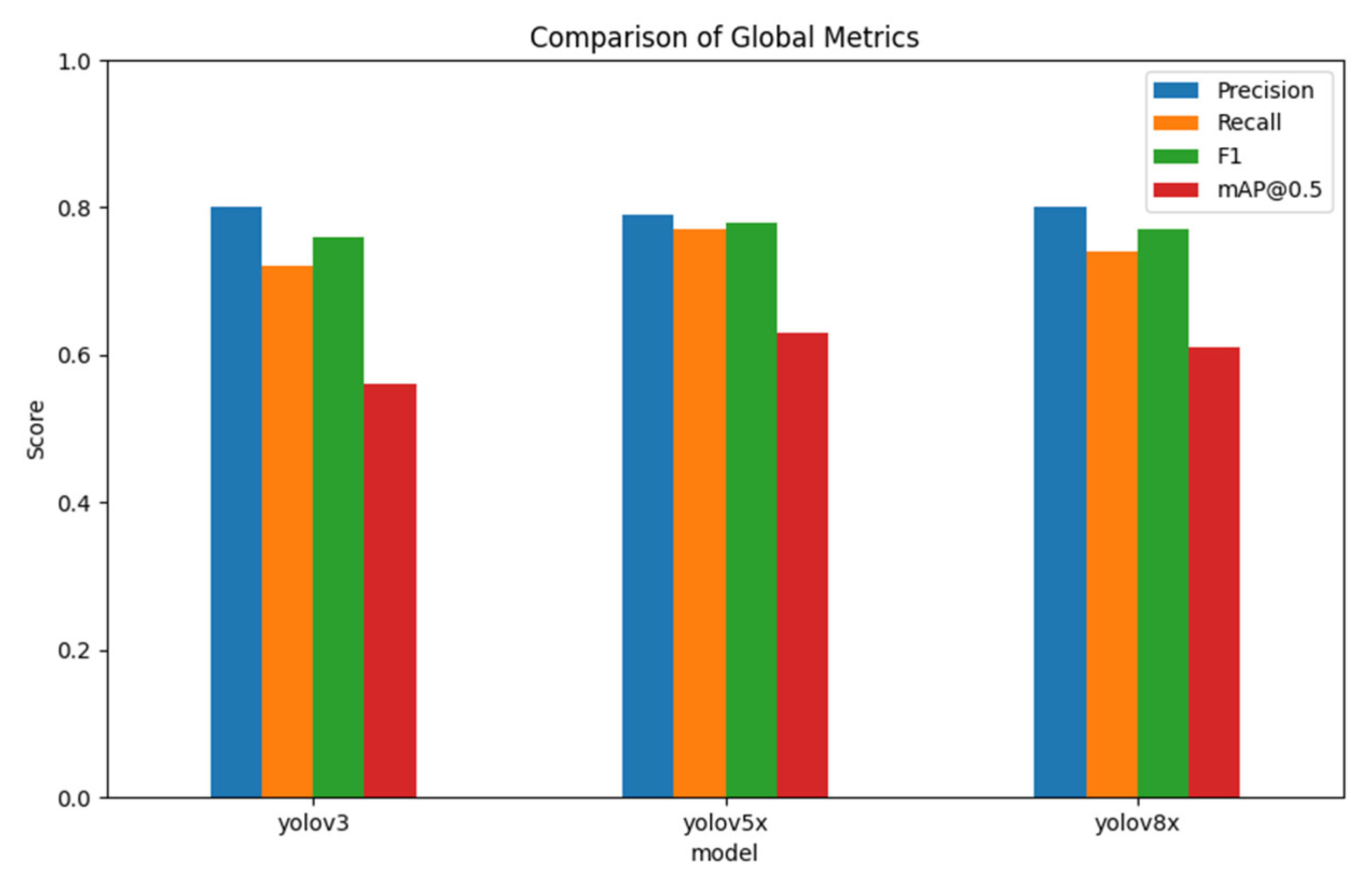

Table 2 presents the overall results for the three models evaluated in the vehicle detection task, reporting metrics for precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@0.5. These metrics enable a comprehensive assessment of performance, considering both the ability to correctly detect objects and the ratio of correct detections to false positives. In addition, the standard deviation (SD) was included to assess the consistency of each model’s performance across different classes. Lower SD values indicate greater stability and less dependence on object frequency or morphology.

Comparatively, YOLOv5 achieved the best balance between precision and recall, reflected in the highest F1-score value of 0.78, as well as the highest generalization capacity in the vehicle detection task, with a mean Average Precision (mAP) at 0.5 of 0.63. In contrast, YOLOv3, although maintaining equivalent precision, presented lower recall and a lower mAP (0.56), which shows a greater propensity to omit objects in the scene. For its part, YOLOv8 ranked in an intermediate position, with competitive values in all metrics, although it did not surpass the performance achieved by YOLOv5.

The variability analysis complements these findings, with YOLOv8 achieving the lowest SD (0.29), followed closely by YOLOv5 (0.32), while YOLOv3 presented the highest dispersion (0.33). This gradual reduction in variability suggests that more recent architectures tend to produce more stable detection results across classes, without strong dependence on object morphology or frequency. These results suggest that, beyond achieving higher average performance, the newer models show improved robustness and consistency.

Figure 5 reinforces these findings through a comparative graphical representation, which provides a clearer visualization of the differences in performance between architectures. YOLOv5 outperforms its counterparts in terms of mAP@0.5, while YOLOv3 shows the most significant gap in terms of recall.

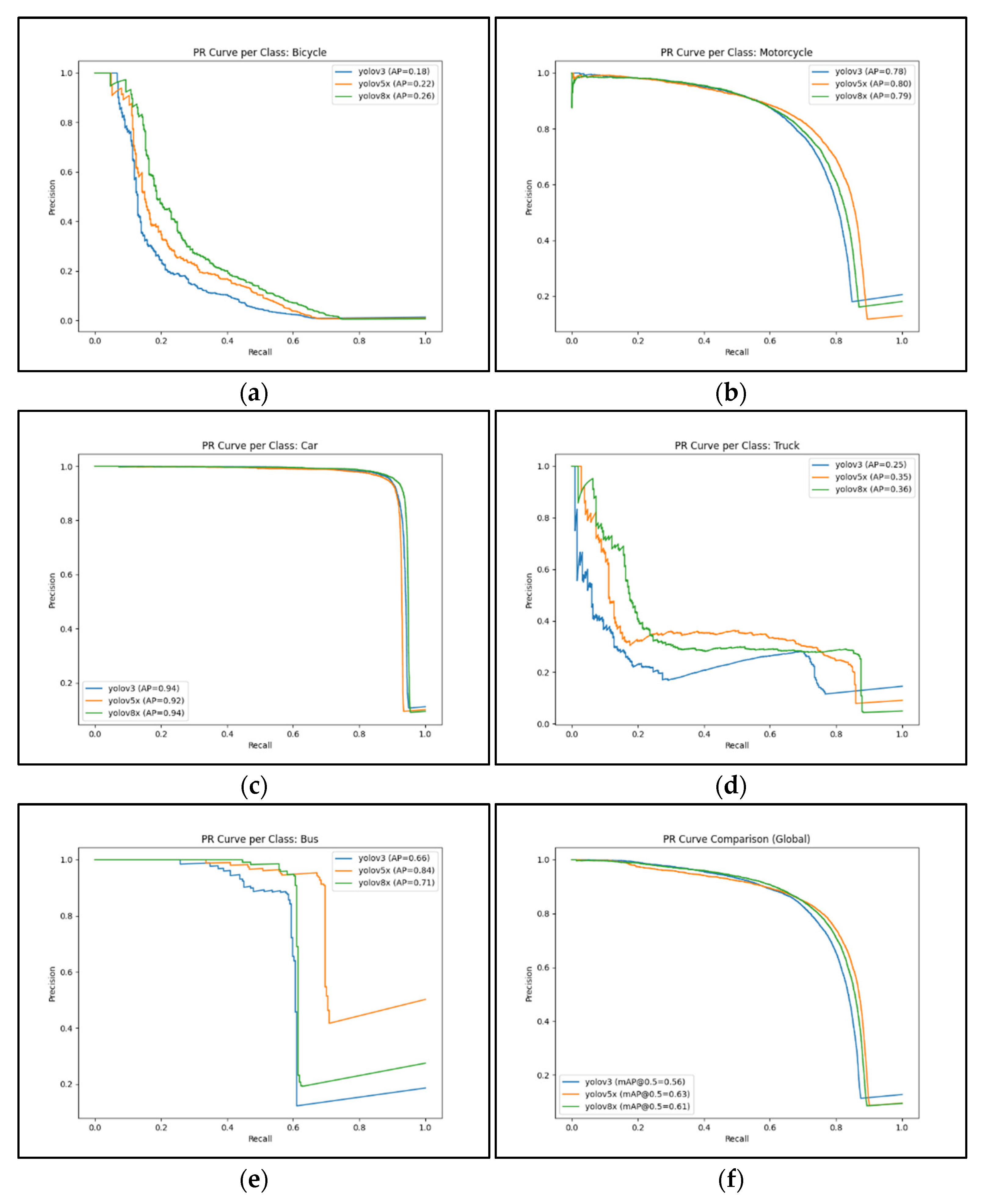

On the other hand,

Figure 6 shows the precision–recall (PR) curves broken down by vehicle class and overall, where the areas under the curve correspond to the AP values. These curves enable a more detailed analysis of the balance achieved between the two metrics across the different confidence thresholds. Globally, YOLOv5 showed the most significant area under the curve, confirming its ability to maintain a balance between precision and recall compared to YOLOv3 and YOLOv8.

Finally, it is important to note that all models were run in their standard configurations, without retraining or hyperparameter tuning. Both YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 were implemented under homogeneous parameters to ensure direct comparability, while YOLOv3 retained its original input resolution, as designed. This methodological approach guarantees that the reported differences in performance are mainly due to the architectural evolution inherent in each model.

4.2. Performance by Vehicle Category

To complement the overall analysis, specific metrics were calculated for each vehicle class. The consolidated results are presented separately for each YOLO version (

Table 3a–c), allowing a more direct comparison of class-level behavior across de model.

Three main findings emerge from comparative analysis of

Table 3a–c: (i) Cars were the most consistently detected category. All architecture achieved AP values close to or above 0.90 in the three architectures, reflecting both the abundance of instances in the dataset and the relative stability of their visual patterns. (ii) Motorcycles and buses show intermediate performance. Both classes consistently maintain F1-scores between 0.70 and 0.79 in the three models, confirming the ability to generalize in categories with greater structural variability. (iii) Trucks and bicycles emerge as the most challenging classes. These categories have the lowest levels of precision and AP (≤0.36), suggesting that their low frequency of occurrence and morphological heterogeneity negatively impact detection.

Figure 7 complements this analysis with a graphical comparison of metrics by class, highlighting that YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 offer more balanced performance across categories, whereas YOLOv3 shows greater disparity, with notable drops in bicycle and truck performance.

4.3. Statistical Significance Analysis

Table 4 presents the results obtained from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a randomized complete block design (RCBD), in which the treatment factor corresponded to the detection model and the block factor represented the vehicle category.

The analysis verified the assumptions of normality with Shapiro–Wilk (p = 0.186) and homogeneity of variances with Bartlett (p = 0.665), confirming the suitability of the model. The results indicate that the model factor was not statistically significant (p = 0.13), suggesting that the differences observed in mAP between YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 are not statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. However, the block effect (vehicle class) was highly significant (p < 0.001), indicating that detection performance is highly dependent on the object category.

It is important to note that, although YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 showed higher mAP and lower variability (SD) values, these numerical differences do not translate into statistically significant improvements. This distinction highlights that ANOVA assesses statistical significance rather than numerical superiority, meaning that while the ranking of the models reflects an order of average performance, it does not provide evidence of a statistically significant advantage between them.

4.4. Visual Evaluation of Predictions

In addition to quantitative analysis, a visual inspection of the predictions generated by the models under different lighting and weather conditions was performed to illustrate their performance in real-world scenarios.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 presents representative examples in urban contexts with environmental variations, complementing the numerical findings reported in the previous sections.

In general terms, the three models maintained stable performance on cloudy days (

Figure 8), where light homogeneity reduced the presence of shadows and reflections that often cause errors. Similarly, good performance was observed on days with light rain (

Figure 9). Finally, on sunny days (

Figure 10)—a characteristic condition of the study region—the performance of the models was considerably lower, with a higher incidence of false negatives and confusion in minority classes. This phenomenon is attributed to the high contrasts between light and shadow, which affect the stability of the predictions.

On the other hand, the trends observed in the analysis by class are confirmed: cars were reliably detected under all conditions, while bicycles and trucks showed the greatest variability in performance. Likewise, it was identified that the most frequent errors correspond to false negatives in partially occluded objects and false positives in dense traffic scenes, which coincides with the patterns reported in the recall and AP values. Overall, visual inspection shows that although the three models offer competitive performance under standard conditions, their robustness in weather and lighting changes is still limited.

4.5. Quantitative Effect of Lighting Conditions

Table 5 presents the results obtained from two-way ANOVA conducted to evaluate the effects of the detection model (factor A) and illumination condition (factor B), as well as their interaction, on the AP.

Analysis of the residuals using the Shapiro–Wilk test revealed a deviation from normality (

p = 0.002), while Bartlett’s test confirmed the homogeneity of variances between treatments (

p = 0.898). Given the violation of the normality assumption, a Box–Cox transformation was applied to stabilize the variance and improve the normal distribution of residuals. The transformed ANOVA (

Table 6) maintained consistent results, showing no significant effects for any of the factors or their interaction (

p > 0.05).

After transformation, Bartlett’s test continued to support homoscedasticity (

p = 0.972), but normality was still not achieved (

p = 0.006). Therefore, a nonparametric factor analysis based on aligned rank transformation (ART) was performed, which is suitable for between-subject factorial designs without assuming normality. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 7.

In all approaches addressed in this analysis (standard ANOVA, Box–Cox transformation, and ART), the results consistently indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between detection models, lighting conditions, or their interaction (p > 0.05). Although some models showed slightly higher AP values, from a statistical point of view these differences are not significant at a 95% confidence level. Therefore, these results suggest that detection performance remains stable for both factors.

However, in numerical terms, the lowest metrics were consistently observed in high light conditions with an average accuracy of 0.66, while in cloudy conditions and after light rain, 0.85 and 0.82 were obtained, respectively. This indicates that this difference is real from both a qualitative and quantitative perspective, even if it does not reach statistical significance. Therefore, these results suggest that detection performance remains generally stable, although it is more affected in high-contrast lighting conditions, as also evidenced in the qualitative analysis of the detections.

5. Conclusions

This study compared the performance of the YOLOv3, YOLOv5, and YOLOv8 vehicle detection models in a real urban environment in Montería (Colombia), under different lighting and traffic density conditions. The results show that YOLOv5 offers the best balance between precision and recall, with an F1-score of 0.78 and a mAP (mAP@0.5) of 0.63, highlighting its generalization ability without the need for retraining. YOLOv3 demonstrated lower recall and mAP, while YOLOv8 performed competitively, although slightly inferior to YOLOv5 in numerical terms. The inclusion of standard deviation metrics and statistical significance tests provided a more rigorous evaluation of model robustness. Although YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 achieved higher numerical scores, the differences between the models were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating that all architectures deliver comparable performance under real traffic conditions. Nevertheless, the consistent trend in mAP and F1-score confirms YOLOv5’s superior numerical performance and stability. Analysis by category revealed that cars were detected with high reliability, while bicycles and trucks were the most challenging cases due to their low frequency and morphological heterogeneity. Visual, quantitative evaluations under various weather conditions—sunny, cloudy, and after rain—showed stable detection in homogeneous lighting, but a decrease in accuracy under high-contrast lighting in numerical terms, reinforcing the models’ sensitivity to strong brightness gradients. However, the significance analysis concludes that from a statistical point of view there is no significant difference. This does not eliminate the actual numerical gap between the metrics; the lower accuracy in high brightness indicates that this condition affects the stability of vehicle detections to some extent. These findings indicate that modern YOLO architectures have significant potential to support intelligent traffic light systems and traffic monitoring in medium-sized cities, supporting their integration into smart traffic light and mobility monitoring systems. In addition, the generated dataset constitutes a replicable resource for future urban mobility studies and opens opportunities for optimizing performance through hyperparameter adjustments and local fine-tuning under extreme environmental scenarios. Furthermore, the methodological framework adopted here—emphasizing reproducibility, statistical validation, and environmental variability—offers valuable guidance for future research seeking to adapt and tune detection models in dynamic real-world conditions. This study provides empirical evidence that can guide future implementations of adaptive traffic light systems in medium-sized Latin American cities.