1. Introduction

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from transportation systems are increasingly subject to public and political concern. The transport sector, responsible for more than a quarter of total GHG emissions in Europe [

1], plays a particularly important role in reaching climate goals. Especially with the decarbonization goals of the European Green Deal to reduce transport emissions by 90% by 2050, all transport modes need to become more sustainable [

2]. As rail transport accounts for only an average of 0.3% of transport sector emissions in Europe [

1], a modal shift to rail can play an important role in reducing transport sector GHG emissions [

3]. However, while rail transport is indeed a more sustainable alternative to road or air travel due to its lower operational emissions, the associated infrastructure can contribute significantly to a project’s overall carbon footprint [

4,

5,

6] and should be considered in strategies to reduce emissions from the railway sector [

7].

Since its amendment in 2014 [

8], the EU Directive 2011/92/EU “on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment” requires that the impact of projects on the (global) climate has to be assessed as part of the environmental impact assessment [

9]. To support effective climate policy and responsible infrastructure development, reliable and comparable GHG assessment methods are needed. Currently, several different approaches are used to evaluate emissions from rail infrastructure, most of which build on life cycle assessment (LCA) principles as formalized in international standards such as ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 [

10,

11]. However, these frameworks leave flexibility for project-specific assumptions, leading to inconsistencies and limited comparability between assessments. Although instruments like Product Category Rules (PCRs) and methodologies on political and administrative levels, such as those used in the German Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan (FTIP) and by the European Investment Bank (EIB) attempt to address this, a universally accepted and harmonized GHG assessment methodology is still lacking.

In contrast, risk assessments are a legal requirement in the railway sector and have a long history of methods and approaches. Some discussions about comparability and applicability that happened there some decades ago are mirrored by today’s discussions with regard to GHG assessment. One of the biggest challenges was finding a balance between sensible effort and possible details. As one solution, semi-quantitative risk assessment methods have been formalized in a national German pre-standard in 2014, outlining systematic criteria for methodological robustness, consistency, and applicability [

12].

This study builds on the conceptual assumption that assessment methods share a set of systematic requirements that are independent from the assessed topic and determine, e.g., their robustness, comparability, and transparency. Therefore, the paper explores the potential for transferring criteria used for the construction of semi-quantitative risk assessment methods to GHG assessment methods, with the aim of identifying a framework for harmonization. Specifically, it evaluates whether systematic criteria used in method construction for risk assessment can inform the development and comparison of GHG methods and proposes additional topic-specific requirements relevant to GHG assessments. In this sense, harmonization is conceptualized as the alignment of underlying systematic criteria across assessment methods.

Overall, this study should serve as a guideline for developing criteria for a new semi-quantitative GHG assessment method that generates robust results as accurately as possible with as little effort as possible. This should lead to a sufficient comparability of the environmental impacts of project variants.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 1 gives an overview of existing GHG assessment approaches for railway infrastructure and the development of semi-quantitative risk assessment.

Section 2 presents the materials and methods, and

Section 3 reports the results of the transferability and applicability of risk assessment criteria on GHG assessment methods.

Section 4 discusses the implications for harmonized assessment approaches, and

Section 5 summarizes key conclusions and recommendations.

1.1. Existing Approaches to GHG Assessment for Rail Infrastructure

The approaches currently used for GHG accounting in rail infrastructure projects are, in many cases, based on the LCA method. This method allows for a holistic consideration of the environmental impacts of a project throughout its entire life cycle. The methodological basis for this is defined by the ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards, which provide the formal framework for accounting for environmental impacts [

10,

11]. The aforementioned standards require a clear definition of the objectives and the assessment framework (e.g., system boundaries, functional unit, life cycle phases considered) in order to ensure a consistent and meaningful assessment of emissions in relation to the objectives of the study.

Since the basic standards define rules for accounting for a wide range of products, processes, and services, they necessarily leave considerable scope for case-specific determinations and assumptions. The large scale and distinctiveness of railway infrastructure projects make it challenging to implement standard LCA methods in a consistent manner across diverse contexts [

13]. For a complete assessment, not only emissions from material production, construction, and maintenance have to be taken into account, but also operational energy consumption, induced modal shifts, and land-use changes [

14]. However, embodied emissions of railway infrastructure account for a significant proportion of overall emissions due to the high amounts of emission-intensive materials such as steel, ballast, and concrete, and the high energy consumption during construction and maintenance [

4,

5,

6].

There are a number of international studies assessing GHG emissions from railway infrastructure that generally also refer to life cycle assessment standards. In their literature review on embodied emissions in rail infrastructure, Olugbenga et al. [

15] identified considerable differences in published studies with regard to research goals, functional units, system boundaries, life cycle assessment methods, and data sources, as well as reported emissions per kilometer of track [

15]. Since the accounting of GHG emissions depends significantly on the parameters and assumptions selected, the use of different specifications can lead to considerable deviations in the results, which makes it difficult to compare different studies: Methodological choices, such as inventory modeling and impact assessment [

16], and assumptions on system boundaries, service life, and end-of-life scenarios [

17] can significantly affect the outcomes of the assessment. In [

18], especially the definition of the system boundaries, the inclusion of emissions from biogenic carbon, and the modeling of the end-of-life were identified as factors leading to inconsistency between standards and the need for harmonization of methods, which is supported by [

15].

To increase the consistency of LCA results, so-called Product Category Rules (PCRs) have been developed. These contain specific, more detailed requirements for defined product categories and are aimed at the publication of an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD). For construction products, there is the European standard EN 15804 [

19] and, specifically for rail infrastructure, a complementary product category rule (c-PCR 023 Railway infrastructure) published by EPD International as the EPD program operator [

20]. The c-PCR 023 includes the balancing of emissions for all life cycle phases ‘from cradle to grave’, specifically, the product stage with manufacturing of products for the infrastructure, the construction process stage (transportation and construction activities), the use stage (use, maintenance, operation of the infrastructure) and the end of life with dismantling and disposal/preparation for recycling [

20]. In addition, the benefits and loads beyond the system boundaries must be reported separately [

20]. It covers all infrastructure components or can be used to assess specific elements, such as individual bridges [

20].

In addition, there are approaches for evaluating infrastructure projects at the political and administrative levels. In Germany, the methodology manual for the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan (FTIP) and the standardized evaluation scheme “Standardisierte Bewertung” are particularly relevant, as they integrate GHG emissions as a component of cost–benefit analysis [

21,

22].

The FTIP method considers the emissions generated during material production and during the construction and utilization phases and offers flat-rate emission factors (CO

2-e/km/year) for five categories of rail infrastructure projects: new lines (lowlands and low mountain ranges), expansion of lines, speed increases, and electrification [

21]. The values are based on a life cycle-based comparison of transport modes commissioned by the German Environment Agency in 2013 [

23,

24] and serve as a guide for estimating the GHG emissions of infrastructure projects for inclusion in the requirements plan. The method requires minimal effort by using standard values per route category, but the results are inaccurate and not tailored to the specific project.

The “Standardisierte Bewertung” is a standardized evaluation scheme for public transport projects in Germany that considers the construction of infrastructure (track system, engineering structures, signaling, catenary, platforms), vehicle production, and vehicle operation [

22]. Default emission factors (kg CO

2/m/year or kg CO

2/unit/year) are provided for a range of standardized components, including the superstructure, substructure, control and safety technology, catenary, platforms, and power stations [

22]. Due to the project-specific nature of engineering structures such as bridges and tunnels, rough material-specific modeling is required, and emission factors for the main materials are provided [

22].

At the European level, there are guidelines for ensuring the climate compatibility of infrastructure, known as ‘climate proofing’ [

25]. These recommend the use of the EIB Project Carbon Footprint Methodologies [

26] for assessing the GHG emissions associated with a project. This methodology is limited to accounting for GHG emissions from vehicle operation, with consideration of modal shift and traffic induction as transport effects. The EIB methodology is used to assess infrastructure projects of the European Investment Bank and represents a standardized approach to enable comparability between different projects [

26]. In addition, the EU Commission recommends the use of the methodology when applying for funding from the Connecting Europe Facility program, making the consideration of GHG emissions in this area practically mandatory [

25]. The revised TEN-T Regulation requires climate proofing for all projects of common interest on the trans-European transport network that are subject to an environmental impact assessment [

27], without, however, referring to the guidelines on ensuring the climate compatibility of infrastructure [

25] or the EIB methodology [

26].

The methods presented differ significantly in terms of scope, system boundaries, granularity, and treatment of data gaps. This heterogeneity of available methods and frameworks poses a challenge as the lack of harmonization complicates comparability and undermines the credibility of assessments. Thus far, no agreed-on method has been universally accepted.

1.2. Semi-Quantitative Risk Assessment Method vs. GHG Assessment Methods

While GHG assessment is rather new, other system aspects have a long tradition of assessment. In particular, risk assessment is a legal requirement in the railway sector and has a long history of methods and approaches. Regarding risk assessment methods, three approaches can be distinguished [

28,

29].

The typical one used in the seventies and eighties was a purely qualitative approach. The method was derived by experts based on experience. Usually, a set of variables expected to affect risk was defined. Each variable was described in a low number of categories. A specific combination of categories yields a final classification that provides information, e.g., on permissive hazard rates [

30,

31]. This approach was easy to apply; however, it lacked a valid scientific basis, and the results could not be shown to be correct. The conditions were never clearly stated. To put it bluntly, “the results were correct just by chance”.

On the other hand, in the nineties, with the introduction of a new safety standard, pure quantitative methods were introduced. The whole path from hazard to accident was quantified in detail, using statistical data; the specific of the assessed function was derived, and these data were combined to determine safety requirements [

30,

31]. While the whole approach was very thorough and easy to explain, the effort to obtain the necessary data was enormous. Also, it was often necessary to rely on experts’ guesses, which naturally have a rather large margin of error.

As neither approach was ideal, a standardization effort began to find a middle ground: a method with a solid mathematical basis but presented in an easy-to-apply format, relying on qualitative categories. This type of method was called “semi-quantitative” [

32]. In 2014, a pre-standard was published in Germany that lists 28 requirements for a semi-quantitative risk assessment method [

12].

In general, a semi-quantitative method is constructed as follows:

The data to be derived are described by a mathematical formula that clearly states the variables [

29].

For each variable, the possible numerical values are grouped [

29], e.g., variable speed can be described in categories: slow (up to 40 km/h), medium (40 to 80 km/h), fast (80 to 160 km/h). In this case, the boundaries of each category are connected by a factor of two. The chosen factor depends on the mathematical model and should be used over all variable classes.

While risk assessment and GHG assessment obviously look at very different aspects and are calculated in different ways, the challenges ahead are very similar. While a “rule of thumb” qualitative method would be easy to use, it very likely would not withstand a legal assessment; e.g., the dependencies of the variables would not be correctly considered. On the other hand, a full-scale quantitative assessment like a complete LCA according to EN 15804 would lead to an enormous effort. Plus, there is not enough data available in the early planning phase to implement the method.

Therefore, a semi-quantitative approach is strongly recommended, combining a solid mathematical basis, a complete set of variables to be considered, and a coherent model with an easy-to-use qualitative presentation, including categories, classes, and parameter classes. From the GHG assessment methods in

Section 1.1, the FTIP method and the “Standardisierte Bewertung” can be categorized as semi-quantitative; yet they still yield very different levels of detail in the results.

While the concept of a semi-quantitative approach is easy to understand, the question of how exactly this method should be constructed needs to be evaluated. It is postulated that by evaluating the criteria of pre-standard DIN V VDE V 0831-101 and discussing their transferability to the area of GHG assessment methods (GHG_AM), valuable input for designing future methods can be obtained.

2. Materials and Methods

The approach for this study assumes that requirements for an assessment method can be derived from three principal groups:

Legal requirements, which have to be adhered to

Topic-specific requirements, which are domain-specific and need to be addressed and measured for the specific system, e.g., data availability

Systematic requirements, which are universal to all assessment methods, rather than being independent of the assessed topic

This paper focuses on the last point. The central hypothesis is that systematic requirements established for semi-quantitative risk assessment methods can be transferred to GHG assessment frameworks, thereby supporting harmonization and improving comparability.

The research followed a multistep approach (

Figure 1). First, the criteria for semi-quantitative risk assessment methods were extracted from the German pre-standard DIN V VDE V 0831-101 [

12], which defines requirements categorized into eight thematic categories: “general,” “system definition,” “scenarios and safety mechanisms,” “frequency and severity assessment,” and “safety requirements.” For each criterion, the conceptual meaning was evaluated to enable interpretation beyond the risk domain.

In the second step, each criterion was examined for transferability to GHG assessment through structured qualitative comparison. This analysis focused on identifying overlaps, gaps, and potential modifications required for transfer. The evaluation used three possible outcomes based on whether the criterion could be meaningfully applied to GHG assessments: “Yes”, if the criterion is transferable; “No”, if it is not transferable; and “Partially”, if transferability is only given partially or with adaptations. For the last type of outcome, the criterion was reinterpreted accordingly for GHG assessment. The results of the transferability are presented in

Section 3.1 and

Table 1.

In the last step, the criteria identified as transferable were tested for compliance with the existing GHG assessment methods from

Section 1.1. This was implemented as a structured qualitative review, in which each method was evaluated against the terms of the criteria derived in the previous step. The methods were selected based on their relevance for the German and European context and their coverage of railway-specific infrastructure. The comparison was intended to highlight inconsistencies and potential synergies of the methods, offering a basis for improving harmonization of the assessment approaches. For each method, published documentation, as well as example applications, were reviewed to determine whether the method fulfills the criteria. Compliance with the transferable criteria was qualitatively scored using a five-level scoring scale:

++ = criterion fully and explicitly addressed;

+ = criterion largely addressed, but with minor limitations;

− = criterion only partly addressed or mentioned implicitly;

−− = criterion not addressed;

* = no publicly available information

Together, the results provide a framework for identifying which systematic criteria could be integrated into future harmonized GHG assessment methods. The method was deliberately kept qualitative to first enable systematic comparison of the two different theoretical frameworks. Future research could expand into a practical and quantitative approach by incorporating (adapted) risk assessment criteria into GHG assessment and applying it to a real-world project.

3. Results

3.1. Transferability of Risk Assessment Criteria on GHG Assessment Methods

In the following, all criteria are discussed shortly with regard to their transferability to GHG assessment methods (GHG_AM).

Table 1 shows an overview of the criteria and their transferability. The aim was to identify parallels between risk assessments and GHG assessments in terms of effort and knowledge gain. To reach this purpose, the present risk assessments were screened to gain ideas for improving and to simplify comparable results of GHG assessments. The analysis showed that a substantial number of the criteria can be adapted with minor reinterpretations, while others were found to be either not directly transferable or irrelevant in the GHG context. In particular, the general criteria from risk assessments could be well adapted to GHG assessments. In contrast, criteria inherently tied to physical accident scenarios, such as hazards, severity, or barriers, were not transferable.

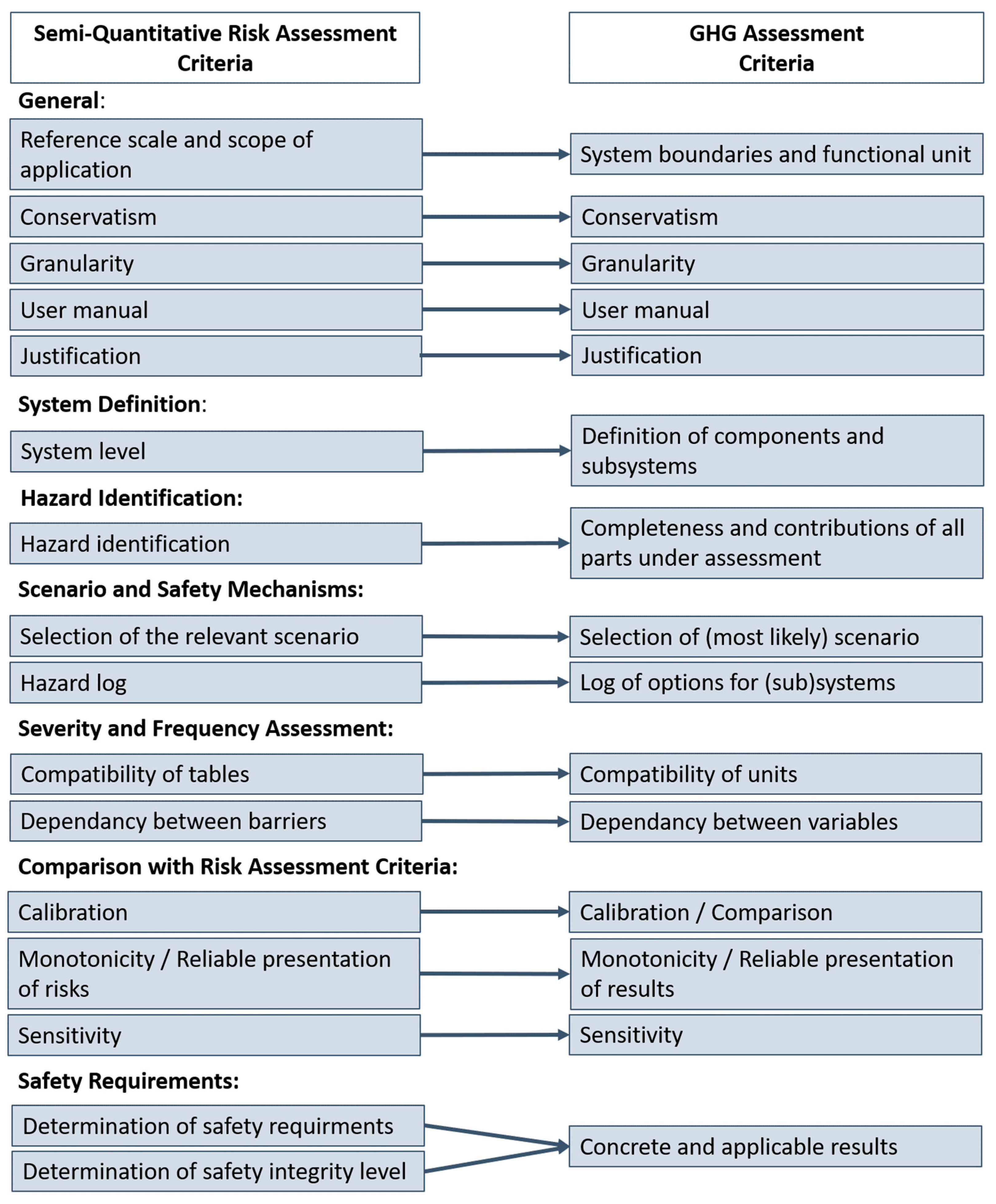

For the criteria that are (partially) transferable,

Figure 2 summarizes the conceptual mapping between semi-quantitative risk assessment and GHG assessment. The figure visualizes how the criteria originally defined for risk assessment can be reinterpreted within the GHG context. The mapping clarifies which methodological principles are domain-independent and can therefore form the basis of a harmonized framework for assessment.

To clarify if and how the criteria can be transferred, the following subsections provide short overviews of the criteria and their possible translation into methodological requirements for GHG assessment of railway projects. Suitable examples for railway infrastructure are also included.

3.1.1. General Assumptions

These general assumptions can be made about any semi-quantitative risk assessment method. They were derived from expert knowledge and by evaluating existing risk assessment methods, both qualitative and quantitative.

Reference scale and scope of application: The most important part of any method is to define the necessary reference scales and objects, as well as the area of application. While the system definition (a later criterion) looks more at a system to be assessed, this criterion makes assumptions about the general applicability. It can be assumed that this is true for GHG_AM as well, corresponding to the system boundaries and functional unit. For example, in the GHG assessment of railway infrastructure, the functional unit is 1 km of (single or double) track, including substructure, superstructure, drainage, and electrification. A project upgrading 5 km of track must normalize its data to this reference unit to ensure comparability across studies and variants.

Conservatism: The method should lead to results “on the safe side”. It can be assumed that this is also correct for a GHG assessment method, especially for assumptions during early planning to avoid underestimation. For instance, if the ballast transport distance is uncertain, the method assigns the higher transport-distance class to avoid underestimated emission results.

Granularity: For risk assessment methods, it is postulated that the factor between two classes within one category should not exceed 10. Experience has shown that for risk assessments, the root of 10 has proven to be especially suitable. While the factor 10 is derived from risk-specific requirements (the so-called SIL level), it can be assumed that for GHG_AM, a similar factor can be found and postulated. For example, using a consistent scaling factor, transport distances may be categorized as follows: A: <20 km; B: 20–40 km; C: 40–80 km. This ensures that all transport-related categories follow the same logic, providing internal consistency across parameters. Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that the granularity of all variables involved should match to avoid unbalanced impacts.

User manual: Having an up-to-date user manual that answers the most frequently asked questions about the application of the method and its background is a must for risk assessment methods, including GHG_AM.

Justification: The semi-quantitative method is assessed by selecting the classes that best fit the scenario. To ensure the best traceability of an assessment, there needs to be a written justification for each chosen class. True for both application areas.

3.1.2. System Definition

In risk assessments, the system under evaluation needs to be defined in detail. This looks especially at functions, but also at application conditions and system limits.

System level: The system level defines for which functions the method is applicable. This is important, e.g., for benchmarking the quantitative part of the methods, as actual numbers will be used. Applying the method on the wrong system level leads to erroneous results. The standard suggests defining the system level by listing the functions it can be applied to. It can be assumed that, in general, the same argumentation can be applied to a GHG assessment method. However, instead of functions, it is suggested to list the infrastructure components to which the method should be applied. For example, for a project constructing an electrified line with ballasted track, mandatory components may include rails, sleepers, fasteners, ballast, sub-ballast, protection layers, drainage systems, catenary masts, and signaling cables.

3.1.3. Hazard Identification

All reasonably foreseeable hazards for the entire system should be identified and assessed.

Hazard identification: For risk assessments, it is necessary to have a proper hazard identification. It has to be assumed that a missed hazard can have serious consequences. For GHG assessment, this criterion should be applied to the completeness of all parts and contributions for a system or process under assessment. While the consequences of missing a part of the system or process might not be safety-relevant, it can falsify the results and thereby reduce their impact.

3.1.4. Hazard Classification

In addition, the identified hazards also have to be classified to identify generally acceptable risks.

Hazard classification: The method should allow a straightforward identification of acceptable/negligible risks. This is specific to the risk assessment process and stems from a requirement of the regulation. There does not exist a similar requirement for a GHG analysis. However, the efforts of any assessment should focus on the biggest shares, such that some contributions that are known to have only very little impact (criteria for this to be defined) can be left out. Typically, in LCA practice, several cut-off criteria are used to decide which inputs to include in the assessment, such as mass, energy, and environmental relevance.

3.1.5. Scenarios and Safety Mechanisms

A hazard does not necessarily cause an accident, as there are usually barriers in the overall system that can still prevent the accident. This is presented in scenarios.

Hazard scenarios: Risk assessments focus on the scenarios from hazard to accident. These scenarios need to be systematic and traceable. An application of this criterion in GHG assessments is not sufficient.

Selection of the relevant scenario: Risk assessment should focus on the most relevant scenario to identify the actual decisive requirements. For GHG assessments, when different options are available, e.g., for the transport of materials, not all options need to be considered; instead, a focus could be on the most likely or, in the worst-case setting, a worst-case likely one. If materials could be transported by rail or truck but logistics are uncertain, the method could prescribe the typical regional scenario, e.g., truck transport at 40–60 km.

Hazard log: All considered hazards and all considered hazard scenarios should be logged for future reference. It can be argued that the number of hazard scenarios is indefinite. Compared to risk assessments, the number of options for (sub)systems and processes in GHG assessments is smaller but also heavily influenced by, e.g., politics, which makes it even more unstable. For example, due to the dependence on transformation paths and climate targets, there are considerable uncertainties regarding the future development of GHG intensity in the areas of energy generation, transport, and material production, which, given the long service life of infrastructure, have a particular impact on the accounting of the use phase and the end of life of projects. It is proposed to log a list of all included (sub)systems and processes under given circumstances.

3.1.6. Severity Assessment and Frequency Assessment (with Special Focus on Barriers)

Risk is a combination of the severity of an accident and the likelihood of this severity. This is very specific to risk assessment and completely different from a GHG assessment, which looks at CO2 output for, e.g., materials and transport, multiplied by, e.g., weight or distance.

Assessment of Accident Severity, Derivation of Accident Frequency, Assessment of Human Reliability, Assessment of Operational Barriers, Assessment of Exposure, Assessment of External Barriers, Assessment of Technical Barriers, Description of Barriers: This group of criteria is not transferable to the GHG assessment. However, clear equations for calculating GHG are needed as a basis for any semi-quantitative method. Each variable needs to be described in categories clearly and combined sensibly.

Compatibility of tables: Tables for criteria need to be compatible. This means that, e.g., the units of all variables used to design the method are compatible. This should be considered for GHG methods as well.

Safety-relevant application constraints: Risk assessments might address barriers that come with safety-relevant conditions. If that is the case, these conditions need to be considered. GHG assessments will not have any safety-relevant constraints or conditions. Therefore, this criterion is not applicable.

Dependency between barriers: While for risk assessments, this criterion only applies to barriers, any dependencies of variables need to be addressed and considered in GHG_AM.

3.1.7. Comparison with Risk Acceptance Criteria

In order to obtain reliable estimates, semi-quantitative methods need to have the following characteristics:

Calibration: A risk assessment method used to derive safety requirements must be calibrated against a risk acceptance criterion. In general, this would also be possible for a GHG assessment, even though there are no criteria yet. Alternatively, the results of the method should be used only for comparative purposes, or an actual, concrete number can be derived.

Monotony/Reliable representation of risks: This criterion demands that if the actual risk for scenario A is the same/smaller than for scenario B, then applying the method should yield the same results. This is applicable to GHG assessment methods as well. If the actual emissions for project A are lower than those for project B, then the method should yield this result.

Sensitivity: For risk assessments, small changes in the input variables may only lead to small changes in the results of the assessment. This is applicable to GHG assessments.

3.1.8. Safety Requirements

For each hazard, the safety requirements have to be determined from the criticality determined for the hazard or hazard scenario.

Determination of safety requirements/Determination of SIL (Safety Integrity Level): Both criteria are specific to risk assessments. They can be used for GHG assessments, provided the method yields concrete, applicable results. For example, results might include total emissions and dominant contributors to provide decision-relevant guidance on mitigation measures during the design phase.

3.2. Compliance of Risk Assessment Criteria with Existing GHG Assessment Approaches

The previous section shows an overall transferability of the risk assessment criteria to GHG assessment methods, with some adaptation or different interpretation of the criteria necessary. Based on the criteria that were considered transferable, this section presents an evaluation of the existing GHG assessment methods. The comparison is intended to highlight inconsistencies and potential synergies of the methods, offering a basis for improving harmonization of the assessment approaches.

Table 2 shows how well the assessment criteria are met by the corresponding GHG method. The scores were assigned based on the presence and clarity of methodological descriptions in the respective documentation. For instance, the criterion “Reference scale and scope of application” received a ++ rating for the LCA approach because both EN 15804 and the c-PCR for railway infrastructure explicitly call for a clear definition of system boundaries, functional units, and applicability conditions, ensuring clear reference scales. The same applies to the EIB method and the “Standardisierte Bewertung”. For the FTIP method, which defines several infrastructure categories but applies uniform emission factors across diverse project types, the same criterion was rated + due to limited comparability.

The analysis showed substantial variation across methods, with certain criteria consistently well met across all approaches, while others showed limited or no implementation. The table highlights where existing methods already converge and where they diverge. While general and system definition criteria were broadly covered across all methods, the reinterpreted hazard-related and calibration criteria were largely absent or only weakly implemented. However, none of the methods individually satisfy the full set of systematic requirements identified earlier. The strongest performance was observed in the LCA approach, which incorporated granularity, justification, hazard identification, sensitivity, and safety requirements. By contrast, the FTIP method demonstrated the weakest match to the criteria, fulfilling primarily structural requirements but lacking granularity, justification, and hazard-related criteria. The “Standardisierte Bewertung” and climate-proofing methods provide intermediate coverage, with strengths in the general requirements, but limited implementation of hazard logging and calibration. It has to be noted that only the FTIP and “Standardisierte Bewertung” are semi-quantitative methods, while the others are quantitative.

This comparative insight forms the analytical basis for future harmonization. By identifying which criteria are commonly fulfilled, a harmonized framework can retain these elements, while the missing or weakly implemented criteria indicate where methodological development is needed. Thus, harmonization in this study refers to the process of deriving consistent requirements for GHG assessment methods at this stage of the research.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the study is to determine whether the underlying principles of semi-quantitative assessment methods can be meaningfully transferred and reinterpreted for GHG assessment of railway infrastructure, thereby assisting in developing systematic GHG assessment methods. This study conceptually demonstrated that a substantial proportion of systematic criteria derived from semi-quantitative risk assessments are transferable to GHG assessment methods. General requirements such as scope definition, conservatism, granularity, documentation, justification, monotonicity, and sensitivity proved to be directly relevant or adaptable. This highlights that both domains share a need for methodological consistency, transparency, and comparability. At the same time, criteria closely tied to hazard scenarios and severity assessment were not transferable. These nontransferable criteria reflect the domain-specific nature of risk and GHG assessments. Instead, successful transfer requires reinterpretation, such as redefining hazard identification as the completeness of process steps, or considering dependencies between barriers as variable interdependencies in GHG systems.

The transferable criteria were applied to existing GHG assessment methods in the form of a structured qualitative review. The analysis demonstrated differences in the extent to which current GHG assessment methods address the transferable criteria from risk assessment. While all methods were found to be generally comparable with regard to the general requirements, including scope, conservatism, granularity, user manual, justification, and system definition, they demonstrated a lower level of alignment with the reinterpreted criteria that were originally more specific to risk assessment.

A semi-quantitative method inherently consists of a quantitative core, in which underlying relationships are expressed mathematically, and a categorical layer, in which these quantitative ranges are transformed into qualitative classes. In the case of risk assessment, this includes explicit formulas for event frequencies, barrier effects, or severity scaling. The present study does not attempt to replicate or propose a quantitative mathematical model for GHG assessments, as the numerical formulation of emission models (e.g., life-cycle emission equations, scaling relationships for material classes, uncertainty distributions) requires a dedicated methodological development process and extensive empirical datasets.

This paper addresses the first and prerequisite step toward harmonization: identifying which system-level, structural, and methodological criteria from semi-quantitative risk assessments are transferable to GHG assessments. These include general requirements (e.g., granularity, monotonicity), system definition, process completeness, documentation, sensitivity, and calibration logic. The quantitative formulation of a harmonized GHG method (i.e., defining how emission factors are mathematically combined, how class boundaries are generated, or how uncertainties are scaled) will need to be developed once robust datasets are selected, topic-specific requirements are defined, and legal requirements are integrated. The present contribution, therefore, provides the systematic foundations upon which such a quantitative model can be built, but does not itself constitute that quantitative model.

In summary, these results indicate that the systematic criteria derived from risk assessments can provide a robust framework for improving the consistency of GHG assessment methods. By adopting transferable elements, GHG assessment methods can achieve greater comparability and reproducibility of results, thereby supporting decision-making in design and infrastructure variants. However, the variability in current practice highlights the need for harmonized guidelines that clearly specify systematic requirements for GHG assessments.

A key problem with existing GHG assessment methods is the relationship between effort and knowledge gain. The methods should aim to deliver insights and decision-relevant outcomes without disproportionate financial and human resource input. The trade-offs between these two factors are particularly evident in existing GHG assessment methods. While the FTIP method requires minimal effort, as it involves the selection of a single standard value for the entire rail project, the knowledge gained is also limited, as this value does not allow for effective comparison of variants or the identification of carbon hotspots. In contrast, the LCA method provides very detailed outputs, but requires a high level of effort. However, this aspect becomes less relevant when creating a semi-quantitative assessment method because the nature of such a method already incorporates this issue, as discussed in

Section 1.2. Nevertheless, it must also be ensured that the level of detail is not too coarse, such that a meaningful comparison of variants can still be made. The ease of application of a semi-quantitative method would especially benefit projects in the early planning phase, where data availability is limited, and there is a high demand for assessment to inform variant and design decisions.

The development of a new semi-quantitative GHG assessment method can be achieved through two different approaches. One option is to further develop one of the existing semi-quantitative methods (FTIP or “Standardisierte Bewertung”) according to the requirement criteria. Alternatively, a quantitative assessment, such as an LCA, can be simplified and classified into a semi-quantitative method. The second approach should be based on multiple detailed quantitative assessments of the same categories of infrastructure components from which the categories and classes for the semi-quantitative approach can be derived. In this initial quantitative assessment, quality and availability of data are key considerations. In the development of the new semi-quantitative method, the selection of appropriate categories and classes, as well as the spacing between them, are relevant aspects to be decided. In addition, a deeper investigation of the legal and topic-specific requirements and how they interact with the systematic criteria will be needed.

A further consideration is the updatability of the method. While this plays a minor role in risk assessment, the data basis for GHG assessments is subject to regular changes in the context of efforts towards climate neutrality. A key challenge for any semi-quantitative GHG assessment method is the ability to remain valid as underlying datasets evolve with decarbonization, particularly emission factors, material compositions, electricity mixes, and construction technologies. This is easier to apply to quantitative methods such as LCA, but semi-quantitative methods such as FTIP and “Standardisierte Bewertung” require a recalculation of the classes each time the underlying data basis changes. To ensure updatability, the method should incorporate a modular structure in which the methodological structure (criteria, classes, categories, granularity) should be separated from the quantitative data (emission factors, energy intensities, replacement intervals), to ensure that individual modules can be revised and updated without altering the methodological framework. This can be achieved through dynamic recalibration rules, which specify how changes in quantitative data translate into shifts in semi-quantitative classes (e.g., class thresholds are recalculated automatically using percentile distributions or fixed scaling factors). Regular review intervals for verification of the data basis should be instituted as a regular procedure within the method’s framework, thereby ensuring that the method remains relevant. To ensure traceability and comparability between assessments conducted with different versions, transparent data and version management are needed.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated whether the systematic criteria defined for semi-quantitative risk assessment methods can serve as a conceptual foundation for harmonizing GHG assessment methods for railway infrastructure. By systematically reviewing the criteria from the German pre-standard DIN V VDE V 0831-101 and evaluating their applicability to GHG assessment, the analysis showed that a substantial proportion of these criteria, particularly those relating to scope definition, granularity, justification, documentation, monotonicity, sensitivity, and calibration logic, are transferable or adaptable to GHG assessment. This demonstrates that, despite addressing fundamentally different domains, both risk and GHG assessments share a need for methodological consistency, transparency, comparability, and structured categorization.

At the same time, this paper demonstrates that while the GHG assessment methods currently in use for rail infrastructure differ in terms of scope, usability, and data requirements, they share a common foundation in assessment principles. However, the analysis also revealed inconsistencies in how well these criteria are met. These gaps point to the need for a more harmonized and methodologically sound approach to GHG assessment—especially one that balances accuracy with practicality.

The analysis showed that comparability between different GHG assessments can be achieved by adapting risk assessment methods. It is important to improve the comparability of GHG assessments to gain valuable and trustworthy figures. Especially when putting higher focus on GHG assessments within public tenders, to keep free competition.

This research provides a conceptual demonstration of transferability. The findings establish the systematic foundations required for a semi-quantitative GHG assessment method. Building on the insights gained from this qualitative analysis, the next step should be the formulation of a semi-quantitative GHG assessment method that combines the systematic requirements analyzed in this study with the legal and topic-specific requirements and a quantitative core, resulting in consistency and accuracy with a user-friendly and effort-effective application. Ultimately, a harmonized GHG assessment framework will support more transparent decision-making in infrastructure planning, enable comparability across projects, and contribute to achieving climate targets through better analyzed infrastructure development.