Abstract

This study examined the efficacy of a 12-week school-based program combining proprioceptive and plyometric training to enhance static and dynamic balance in children and adolescents with visual impairment. A total of 33 students were randomly assigned to either an experimental group (EG; n = 18), receiving a one-weekly session of integrative training alongside regular physical education, or a control group (CG; n = 15), following only the standard curriculum. Balance outcomes were assessed at baseline (T0) and post intervention (T1) using stabilometric measures under visual deprivation (eyes closed) and BOT-2 (Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition) balance subtests. The EG demonstrated statistically significant reductions in ellipse surface area (p = 0.002, d = −1.29), center of pressure displacement (p < 0.001, d = −1.67), and sway velocity (p = 0.015, d = −1.06), indicating improved postural stability when vision was unavailable. BOT-2 Test 4 showed significant intra-group improvement (p = 0.006, d = 1.37), while BOT-2 Test 3 and between-group comparisons revealed medium-to-large effect sizes, though not always statistically significant. These findings suggest that augmenting somatosensory input through proprioceptive and plyometric training may partially compensate for visual deficits and improve postural control in individuals with visual impairments. This improvement likely reflects the activation of compensatory mechanisms that enhance proprioceptive and vestibular contributions to balance maintenance. Importantly, meaningful improvements occurred with just one weekly session, making this an accessible and scalable intervention for inclusive school settings.

1. Introduction

According to the most recent estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 285 million people worldwide have visual impairment, of whom 39 million are completely blind. Projections indicate an increase of approximately 1–2 million new cases each year in the absence of adequate intervention [1].

Sight is one of the primary means by which humans explore and interact with their environment and communicate with others. Visual perception and the stimuli it provides give us constant feedback about our environment, enabling us to move around safely and independently. People with visual impairments—whether total blindness, severe low vision, or reduced visual function—face significant challenges in their daily activities and mobility [1].

During childhood, sight plays a fundamental role in motor development and personal autonomy. The partial or total loss of vision, in addition to causing practical difficulties such as recognizing environmental obstacles, profoundly affects motor control and the development and management of postural balance. Vision integrates information from the vestibular and somatosensory systems, which are fundamental processes for the development and maintenance of static and dynamic balance [2,3]. However, when these systems are impaired, compensation and integration by other vestibular and somatosensory pathways is inevitably necessary, in a process of vicariousness. Nevertheless, these compensatory mechanisms are not always fully effective, particularly in dynamic tasks or in conditions that are particularly demanding from a sensory point of view. In these cases, there is an increase in body oscillation, instability and a consequent greater risk of falls [2,4]. Furthermore, vision plays a critical role not only in motor development and interaction with the environment, but also in functional abilities and academic skills such as reading and learning [5].

The literature shows that people with visual impairments frequently have deficits in balance and postural control [6,7]: the lack of adequate visual feedback compromises the quality of walking and posture, increasing the risk of falls and making interaction with the environment and the development of autonomy more complex [8]. In blind or visually impaired children, compensatory mechanisms are put in place early on, through alternative motor strategies [9]. However, the process of balance development in this population may be slowed down or follow different paths than in their sighted peers.

In the literature, balance is defined as the ability to maintain the center of gravity within the base of support, resulting from a complex interaction of visual, vestibular and somatosensory information [2]. Dynamic balance refers to the ability to stabilize the body during movement or following external disturbances. The development of effective balance control is essential for achieving the fundamental stages of motor development. The absence of visual input during the growth phases can generate atypical coordination patterns [9,10], but it can also induce greater attentional effort in the execution of motor tasks that require postural stability. In childhood and adolescence, literature reports that visual impairment is associated with lower performance in functional balance tests, greater instability on different surfaces, and more controlled and cautious motor patterns. This has repercussions on motor development, active participation in physical activities, and quality of life [3,5,11]. Even milder visual impairments, such as amblyopia or strabismus, are associated with reduced performance in balance tests compared to sighted peers, highlighting the importance of binocular integrity in the development of postural control [6,7].

Balance, both static and dynamic, is a basic motor skill not only for daily life but also for sports [12]. To assess the level of balance, both static and dynamic, it is therefore important to use tests that include not only tasks on stable surfaces, but also on unstable surfaces, tandem exercises or exercises with a reduced support base, as well as tests with reduced visual input.

The scientific literature supports the use of specific training programs for developing and improving balance. Among the most effective interventions, both in the able-bodied population and in those with disabilities, are balance training and plyometrics, which work on the static and dynamic components of balance, stability and muscular fitness [13,14,15]. Studies on balance training and plyometrics show significant improvements not only in balance and stability, but also in postural control and management of support on different surfaces [16]. Plyometric exercise—characterized by rapid movements based on the muscle stretch-shortening cycle—has been shown to improve static and dynamic balance [17,18]. Both horizontal and vertical plyometric work promotes postural stabilization, improves response to external disturbances [18] and, in individuals with sensory disabilities such as visual impairment, effectively stimulates proprioception and neuromuscular control [18]. The available literature on adapted physical activity in individuals with visual impairments reports benefits in several motor domains, including mobility, balance, and functional performance. However, the heterogeneity of protocols and the lack of a standardized methodological framework limit the generalizability of findings and increase the risk of bias [19].

Based on this evidence, the present study implemented a 12-week intervention program at a special school for students with visual impairments in Romania. The sample included adolescents and pre-adolescents of both sexes, divided into an experimental and a control group. The intervention consisted of one weekly session integrated into the regular physical education curriculum, combining plyometric and balance exercises aimed at enhancing both static and dynamic stability. Assessments were conducted before (T0) and after 12 weeks of training (T1) using functional tests validated for this population.

The aim was to verify whether the systematic integration of plyometrics and balance exercises could produce significant improvements in postural stability and functional balance, with possible positive effects on motor economy and school participation among students.

1.1. Aim of the Study

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific balance training protocol, enriched with plyometric exercises, administered in parallel with school motor activities, on improving static and dynamic balance in a sample of children and adolescents with visual impairments. The study aimed to verify, through validated tests and objective analysis tools, whether a 12-week cycle of proprioceptive, stabilization and plyometric exercises could produce significant improvements compared to the curricular physical education program alone.

1.2. Specific Objectives

- (a)

- To verify changes in motor performance between the pre-test (T0) and post-test (T1), both within each group (intra-group analysis) and between groups (inter-group analysis), in relation to the following variables:

- Independent variable (IV): motor intervention protocol.

- Dependent variables (DV): BOT-2 test balance subscale scores; stabilometric parameters measured using a baropodometric platform, including center of pressure (COP), average COP oscillation speed, and stability ellipse amplitude.

- (b)

- To assess whether the experimental protocol leads to statistically and clinically significant improvements in balance parameters compared to the physical activity carried out by the control group as part of the curriculum.

1.3. Research Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1.

The experimental group would show a significant improvement between T0 and T1 in static and dynamic balance parameters, compared to the control group.

Hypothesis 2.

The proprioceptive and plyometric training protocol would result in significant improvements in the postural performance of the experimental group, greater than those observed in the control group.

Hypothesis 3.

Participants in the experimental group would achieve greater increases in tests with high motor demands and challenging conditions (e.g., unstable support, eyes closed) compared to the control group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study involved 34 Romanian students, 19 females and 15 males, with visual impairment (VI) enrolled in a specialized educational institute and regularly attending curricular physical education classes. Participants were allocated into two groups: Experimental Group (EG; n = 19) and Control Group (CG; n = 15).

Participants presented heterogeneous levels of visual impairment, ranging from severe low vision to total blindness, as defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Information regarding the specific level of visual impairment (mild, moderate, or severe) was not available to the researchers, as the study was conducted in a school setting and medical records were not accessible. Only students with total blindness were explicitly identified by the schools, while for the remaining participants, the presence of visual impairment was documented without detailed clinical classification. Due to the limited sample size, no subgroup analyses were performed, but this variability was considered when interpreting the results. Parental informed consent was obtained for all participants, and teachers provided institutional authorization. In addition, all students were informed about the study procedures and were asked whether they wished to participate. Only those who voluntarily agreed were included in the study. The same procedure was followed for students who were of legal age.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- (a)

- certified diagnosis of visual impairment;

- (b)

- informed consent obtained from parents or legal guardians;

- (c)

- absence of multiple disabilities (intellectual, motor, or additional sensory impairments);

- (d)

- regular participation in the intervention protocol;

- (e)

- authorization from the class teachers involved.

Exclusion criteria included the following:

- (a)

- missing data at either T0 or T1 assessments;

- (b)

- presence of associated intellectual disability;

- (c)

- more than 30% absence from scheduled sessions;

- (d)

- lack of informed consent from parents, legal guardians, or teachers.

Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from a single specialized school for students with VI. Allocation to groups was performed through individual randomization by an external researcher not involved in the intervention, using a computer-based random number generator (Microsoft Excel) to ensure balanced group sizes. The EG followed a specific protocol of exercises aimed at improving balance and postural stability, whereas the CG continued exclusively with the regular physical education curriculum. Anthropometric characteristics measured at T0 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anthropometric Characteristics of Participants at T0 (Mean ± SD), by Group (EG and CG).

2.2. Experimental Procedure and Intervention Protocol

Assessments were carried out at two points—T0 (pre-intervention), prior to the start of the training protocol, and T1 (post-intervention), at the end of the 12-week intervention period. Testing sessions were conducted at the school facility during regular class hours, in small groups, and under the supervision of specialized staff. All assessments took place in familiar environments at controlled room temperature. The order of tests was kept constant in both sessions to minimize potential learning or fatigue effects.

Each testing session consisted of the following:

- anthropometric measurements (height and body mass) using a wooden stadiometer and an analog scale;

- administration of motor and postural tests.

2.3. Intervention Protocol—Experimental Group

The EG participated in a school-based program of static and dynamic balance exercises, conducted once per week (45–50 min/session) over 12 weeks. The reduced frequency was determined by school and organizational constraints, aiming to evaluate its effectiveness in a realistic and feasible educational setting.

The intervention was delivered by a graduate in Sport and Exercise Sciences, a member of the research team, in collaboration with the school’s kinesiotherapy teacher, who was also a graduate in Sport Sciences and responsible for physical education and therapeutic movement activities at the school. Each training session lasted approximately 60 min, including about 10 min of warm-up and 5 min of cool-down and stretching. During each session, participants performed 5–6 proprioceptive and plyometric exercises (as jumps on rigid and unstable surfaces), with rest intervals of approximately 5 min to avoid fatigue. The exercises were similar for all students within each session, but varied across the 12-week intervention period, with only some tasks being repeated using different execution variants or levels of difficulty.

The experimental group trained once per week, working in small subgroups, and the intervention was conducted in addition to the students’ regular curricular physical education lessons, not as a replacement. The content of each session included an initial mobility activation phase and familiarization with balance tasks, performed with and without shoes, followed by activities on mats, foam pads, balance boards, benches, and balls in both bipodal and monopodal positions. The final sessions of the 12 weeks of intervention included game-based activities emphasizing balance and stability. Regular physical education lessons for both groups followed the school’s standard curriculum and were independently managed by class teachers. Dual-task activities consisted of exercises combining balance and simultaneous motor or sensory tasks, such as ball throws or dribbles on unstable surfaces, single-leg basketball shots, and music-based coordination games requiring movement across different surfaces and postures, or paired balance challenges.

Progressive overload was achieved by progressively increasing instability, adding controlled perturbations, and incorporating dual-task activities.

2.4. Intervention Protocol—Control Group

The CG continued with regular curricular physical education lessons, without modifications or additional experimental activities.

2.5. Assessment Tools

Outcome measures included the following:

- Stabilometric assessment using the BTS G-Studio baropodometric platform;

- Balance subtests from the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency—Second Edition (BOT-2) [20,21,22].

The platform features 2304 resistive sensors (1 × 1 cm) arranged over a 480 × 480 mm active surface, with an acquisition frequency up to 100 Hz and a pressure range of 30–400 kPa. The proprietary software automatically processes the footprint to calculate contact area, force, maximum and mean pressures, weight distribution, and center of pressure trajectory, providing both numerical and graphical outputs. Static tests include weight distribution and classification of foot type, while dynamic tests evaluate gait parameters, center of pressure progression, and foot stability indices. The parameters considered were the center of pressure (COP) path length, ellipse surface area, and COP velocity. Lower values of ellipse area and stabilogram surface indicate better postural stability, while higher COP path length and velocity values reflect increased postural sway and reduced balance control. Each participant performed bipodal stance tests with eyes open and eyes closed, lasting 20 s each, and unipodal stance tests on the right and left legs with eyes open, lasting 10 s each. Up to three trials were allowed for each condition, with the first two serving primarily as familiarization attempts to ensure understanding of the task.

Balance performance was assessed using items 3 and 4 of the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2) [20,21,22]. Each participant performed two trials per task, and the best performance was used for scoring. The nine subtests and their scores are detailed in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

BOT-2 Balance Subtests: Test Conditions, Visual Input, and Scoring Ranges.

According to the BOT-2 manual, raw performances are converted into point scores based on duration (for static balance tasks) or number of steps (for dynamic balance tasks). For item 3, which measures the ability to maintain balance, scores were assigned as follows: 0–0.9 s = 0 points; 1–2.9 s = 1 point; 3–5.9 s = 2 points; 6–9.9 s = 3 points; ≥10 s = 4 points.

For item 4, which assesses balance while stepping, scores were assigned as follows: 0 steps = 0 points; 1–2 steps = 1 point; 3–4 steps = 2 points; 5 steps = 3 points; ≥ 6 steps = 4 points.

Among the nine BOT-2 balance subtests, Test 3 and Test 4 were specifically analyzed, as they are sensitive to postural instability and visual deprivation. These two subtests are also among the most frequently employed in the literature to assess the effectiveness of balance interventions in populations with sensory impairments.

All measurements were conducted by qualified personnel with specific training in motor sciences.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25. Prior to inferential testing, data were examined for outliers and assessed for distributional assumptions using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

An a priori sample size estimation was conducted using G*Power 3.1 [23]. Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), α = 0.05, and a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80 for a repeated-measures design, the required sample size was estimated at 28 participants. The final sample of 33 participants (EG = 18; CG = 15) exceeded this threshold, ensuring an adequate level of statistical power. Nevertheless, effect sizes were reported alongside p-values to support the interpretation of results and to inform future research.

All analyzed variables, including stabilometric measures (ellipse area, center of pressure displacement, mean velocity under eyes-closed conditions) and the BOT-2 balance subtest scores, showed significant deviations from normality (p < 0.05). Consequently, non-parametric tests were applied, as they are more appropriate for small sample sizes and non-Gaussian distributions.

The analyses included the following:

- Within-group comparisons (T0 vs. T1) for each group separately, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test;

- Between-group comparisons (Δ = T1 − T0) between EG and CG, using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Given the non-normal distributions, we report effect sizes consistent with the non-parametric tests. For within-group Wilcoxon signed-rank tests we report Rosenthal’s r (r = Z/√N). For between-group Mann-Whitney U tests we report the rank-biserial correlation (r_rb = 1 − 2U/(n1n2)), equivalent in interpretation to Cliff’s δ. For comparability with previous studies, Cohen’s d is provided only in the Appendix A as a descriptive measure, acknowledging its limitations for non-normally distributed data. Effect sizes were interpreted as follows [24]:

Small ≈ 0.10, Medium ≈ 0.30, Large ≥ 0.50 (for r/r_rb).

Small ≈ 0.20, Medium ≈ 0.50, Large ≥ 0.80 (for d).

2.7. Baseline and Adjusted Analyses

We compared the experimental and control groups at baseline (T0) using Mann-Whitney tests (reporting rank-biserial r_rb). To account for any initial imbalances, between-group comparisons were further analyzed using ANCOVA (T1 as the dependent variable, Group as fixed factor, and T0 as covariate). In addition, a Quade rank ANCOVA was performed as a robust sensitivity analysis. Adjusted effects are reported as partial η2 (with 95% confidence intervals where applicable).

No correction for multiple comparisons was applied, given the exploratory nature of the study and the theoretical coherence of the predefined hypotheses; however, this may increase the risk of type I error, and results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Accordingly, findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory, pending replication in larger samples. Between-group comparisons were based on individual change scores (Δ = T1 − T0), analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test (effect size = rank-biserial r_rb). For descriptive comparability with prior studies, Cohen’s d values are reported only in the Appendix A, with signs denoting the direction of change. Adjusted ANCOVA and Quade analyses were considered primary for between-group inference; Δ-based Mann-Whitney results are reported as secondary analyses. All analyses were two-tailed, with α set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Group (EG)

In the experimental group, improvements were observed across all analyzed variables. Although not all changes reached statistical significance, effect size values indicated substantial and clinically relevant impacts. Improvements in balance performance were reflected by reductions in the ellipse surface area and stabilogram surface, indicating greater postural stability. Conversely, decreases in COP path length and velocity corresponded to improved control of body sway. Across most conditions, the experimental group showed greater reductions in these parameters compared to the control group, confirming enhanced balance performance following the intervention.

- Ellipse Surface (Eyes Closed): decreased from 65.20 ± 49.92 mm2 to 52.65 ± 43.80 mm2 (r = −0.57, p = 0.142).

- COP Distance (Eyes Closed): improved from 47.11 ± 32.15 mm to 26.54 ± 15.10 mm (r = −0.66, p = 0.196).

- Speed (Eyes Closed): slight reduction from 0.0071 ± 0.0033 mm/s to 0.0062 ± 0.0022 mm/s (r = −0.43, p = 0.865).

- BOT-2 Test 3: increased from 1.94 ± 1.61 to 3.22 ± 1.56 (r = +0.73, p = 0.799) although the very large effect size should be interpreted with caution due to lack of statistical significance.

- BOT-2 Test 4: significant improvement from 1.83 ± 1.47 to 3.39 ± 1.69 (r = +0.56, p = 0.006).

The most notable effect was recorded in BOT-2 Test 4, confirming the effectiveness of the protocol on dynamic balance under challenging conditions.

3.2. Control Group (CG)

In the control group, the observed changes did not reach statistical significance, and effect sizes were small or negligible, showing a trend towards no improvement.

- Ellipse Surface (Eyes Closed): increased from 99.88 ± 195.40 mm2 to 195.24 ± 390.91 mm2 (r = +0.13, p = 0.188).

- COP Distance (Eyes Closed): worsened from 79.70 ± 55.07 mm to 97.86 ± 91.34 mm (r = +0.08, p = 0.465).

- Speed (Eyes Closed): increased from 0.0080 ± 0.0055 mm/s to 0.0098 ± 0.0091 mm/s (r = +0.09, p = 0.478).

- BOT-2 Test 3: increased from 2.11 ± 1.54 to 2.94 ± 1.76 (r = +0.45, p = 0.121; not significant).

- BOT-2 Test 4: increased from 2.00 ± 1.36 to 2.61 ± 1.41 (r = +0.12, p = 0.599).

Although some within-group effect sizes were relatively large (e.g., BOT-2 Test 3 in CG), the lack of statistical significance and the inconsistent trends across variables indicate that the control group did not experience systematic benefits from the curricular activity alone. Before testing the intervention effects, we compared the experimental and control groups at baseline (T0) using Mann-Whitney U tests. The results are reported in Table A1 in the Appendix A. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in any of the analyzed baseline measures (all p > 0.10). Rank-biserial correlations r_rb ranged from −0.12 to 0.21, corresponding to negligible or small effects. Specifically, the experimental and control groups showed comparable starting values in Ellipse Surface (EC) (65.20 ± 49.92 mm2 vs. 99.88 ± 195.40 mm2; U = 118.0, p = 0.27, r_rb = −0.14), COP Distance (EC) (47.11 ± 32.15 mm vs. 79.70 ± 55.07 mm; U = 112.5, p = 0.19, r_rb = 0.12), and Speed (EC) (0.0071 ± 0.0033 mm/s vs. 0.0080 ± 0.0055 mm/s; U = 124.0, p = 0.41, r_rb = 0.05). Similarly, no baseline differences were detected for the BOT-2 Test 3 (1.94 ± 1.61 vs. 2.11 ± 1.54; U = 120.0, p = 0.33, r_rb = 0.18) or BOT-2 Test 4 (1.83 ± 1.47 vs. 2.00 ± 1.36; U = 119.0, p = 0.30, r_rb = 0.21). These findings confirm that both groups started from comparable baseline performance levels, supporting that subsequent improvements can be attributed to experimental training rather than pre-existing differences. Baseline comparisons confirmed no significant differences between the experimental and control groups for any stabilometric or BOT-2 variable (all p > 0.10), supporting the comparability of the two groups before the intervention. No statistically significant differences were found between groups for age (U = 121.5, p = 0.42, r_rb = 0.08), confirming that the experimental and control groups were comparable in terms of participants’ chronological age at baseline.

3.3. Between-Group Effects (Adjusted Analyses)

To control for potential baseline differences, ANCOVA models (T1 ~ Group + T0) confirmed significant advantages for the experimental group in stabilometric outcomes under eyes-closed conditions. Sensitivity analyses using Quade rank ANCOVA yielded consistent results.

Secondary Δ-based analyses:

Mann-Whitney tests on change scores (Δ = T1 − T0) showed comparable patterns, with large rank-biserial effect sizes (r_rb) favoring the experimental group.

Stabilometric Variables (Eyes Closed):

- Ellipse Surface: EG mean reduction = −12.55 ± 41.21 mm2 vs. CG increase = +95.36 ± 354.48 mm2; p = 0.002, r_rb = −0.54 (large effect, statistically significant).

- COP Distance: EG = −20.57 ± 31.19 mm vs. CG = +18.16 ± 63.89 mm; p < 0.001, r_rb = −0.64 (very large effect, highly significant).

- Speed: EG = −0.0009 ± 0.0031 mm/s vs. CG = +0.0018 ± 0.0087 mm/s; p = 0.015, r_rb = −0.47 (large effect, statistically significant).

These differences suggest a substantial improvement in balance control under visual deprivation conditions for the experimental group.

BOT-2 Subtests:

- Test 3: EG Δ = +1.28 ± 1.25 vs. CG Δ = +0.83 ± 1.77; p = 0.240, r_rb = +0.31 (medium effect, not significant).

- Test 4: EG Δ = +1.56 ± 1.16 vs. CG Δ = +0.61 ± 1.71; p = 0.093, r_rb = +0.33 (medium effect, trend towards significance).

Although BOT-2 subtests did not reach statistical significance, the magnitude of the effects observed suggests that the protocol promoted greater improvements in the experimental group compared to controls, particularly in dynamic balance tasks and under unstable conditions.

Quantitative results for stabilometric variables and BOT-2 balance subtests are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. For each group (EG and CG), mean values ± standard deviations at pre-test (T0) and post-test (T1) are reported, along with mean change (Δ) ± SD, corresponding p-values, and effect sizes (r and r_rb) for both within-group and between-group analyses.

Table 3.

Results of Stabilometric Tests under Eyes-Closed Conditions (Δ = T1 − T0).

Table 4.

Results of BOT-2 Balance Subtests (Δ = T1 − T0).

The analysis of the data presented in Table 4 and Table A1 in the Appendix A confirms a favorable trend in the experimental group compared to the control group, particularly for the stabilometric variables measured under eyes-closed conditions, which show reductions in ellipse surface area and COP distance with large to very large effect sizes and statistical significance. In the BOT-2 subtests, although no statistically significant between-group differences were found, medium-to-large effect sizes indicate more consistent improvements in the experimental group, especially in dynamic balance tasks and under unstable conditions.

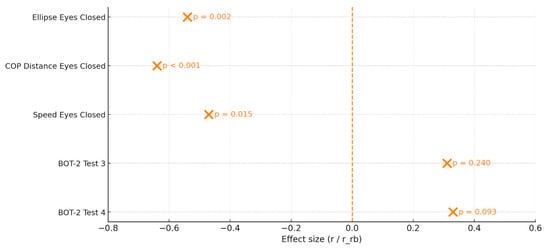

Figure 1 provides a concise graphical representation of effect sizes (r/r_rb) and p-values for all variables considered, facilitating an overall interpretation of the treatment’s effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Forest Plot of the Intervention Effects on Stabilometric Variables and BOT-2 Subtests. The Plot Displays the Effect Size (r for Within-Group Wilcoxon Tests and r_rb for Between-Group Mann–Whitney Comparisons) for Each Variable, with Estimated Error Intervals. Variables Include Postural Parameters Measured under Eyes-Closed Conditions and the Two BOT-2 Balance Subtests. The Corresponding p-values Are Shown Next to Each Point. The Vertical Dashed Line Represents the Null Effect (r = 0).

Clarification on effect sizes:

To align with the non-parametric approach, within-group effects are expressed as Rosenthal’s r and between-group effects as rank-biserial r_rb. Effect sizes are signed to indicate the direction of change: for stabilometric variables (where lower values indicate improvement), negative r/r_rb values favor the experimental group; for BOT-2 scores (where higher values indicate improvement), positive r/r_rb values favor the experimental group. Cohen’s d values are provided only in the Appendix A for descriptive comparison.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a proprioceptive training protocol integrated with plyometric exercises in improving static and dynamic balance in children and adolescents with visual impairment. The results partially support all three initial hypotheses: the experimental group showed greater improvements than the control group, particularly in stabilometric variables under visual deprivation conditions, whereas the BOT-2 tests showed favorable trends that were not always statistically significant.

The present findings align with previous studies demonstrating that physical activity interventions can effectively enhance balance in individuals with visual impairments by stimulating non-visual sensory systems. Wiszomirska et al. reported significant postural improvements in blind participants following vestibular-stimulating exercises, supporting the hypothesis that activating the vestibular and proprioceptive systems may partially compensate for visual loss [12]. Similarly, Rutkowska et al. showed that targeted motor training in blind adults leads not only to improved postural control but also to structural brain plasticity within multisensory cortical areas [9].

More recently, experimental studies in literature confirmed that the severity of visual impairment strongly affects balance levels and locomotor performance in young people, with those having milder impairments showing better stability and coordination [25]. These works emphasized the importance of early, structured interventions to counteract the postural and motor limitations associated with visual loss. In line with these observations, our study extends this evidence by applying a combined proprioceptive and plyometric program in a school-based context, showing that such interventions can promote postural adaptation even in more severely impaired participants.

In contrast to the vestibular-focused or general motor training protocols used in previous studies, our intervention incorporated dynamic plyometric components aimed at enhancing neuromuscular responsiveness and sensory feedback. This multidimensional approach may have contributed to the observed improvements in both eyes-open and eyes-closed balance conditions. Importantly, to our knowledge, there is still an almost complete absence of studies specifically examining the effects of plyometric training on balance in individuals with visual impairments.

Previous research has primarily focused on general physical activity, vestibular stimulation, or proprioceptive-based exercises. Therefore, the inclusion of a plyometric component represents a novel and promising direction, highlighting the potential of high-intensity, dynamic movements to foster sensorimotor integration and postural adaptation in the absence of vision. Our findings also address the gap identified by Sweeting et al. [19] who noted that most physical activity programs for visually impaired individuals were small-scale and low-intensity.

By demonstrating measurable postural benefits following a structured proprioceptive–plyometric program implemented in a real-world school environment, the present study provides new evidence supporting the feasibility and effectiveness of sensorimotor-oriented interventions in visually impaired youth. Overall, these results suggest that proprioceptive and plyometric interventions can complement and expand previous rehabilitation-oriented approaches by promoting multisensory integration, neuromotor adaptation, and functional balance improvements.

4.1. Improvements in the Experimental Group

Within the experimental group (EG), within-group effect sizes (Rosenthal’s r) were medium-to-large in the most demanding conditions (e.g., eyes-closed stabilometry). The reduction in ellipse surface area (r = −0.57) and COP distance (r = −0.66) indicates improved postural stability despite non-significant p-values. In the BOT-2 subtests, Test 4 showed a significant improvement (p = 0.006; r = +0.56), while Test 3 displayed a very large within-group effect (r = +0.73) that should be interpreted with caution given variability (see also [24,26]). This variability likely reflects individual differences in age, baseline motor competence, and severity of visual impairment within the experimental group. Although no subgroup analyses were conducted due to the limited sample size, these inter-individual differences were explicitly considered when interpreting the effect sizes and statistical outcomes.

In the BOT-2 subtests, Test 4 showed a significant improvement (p = 0.006; d = 1.37), indicating a relevant impact of the intervention on dynamic balance under unstable conditions (e.g., unstable support, eyes closed). Test 3 also displayed a very large effect (d = +2.12), although not statistically significant, and should be interpreted with caution due to high within-group variability. Very large effect sizes (e.g., d > 2) should be interpreted with caution, as they may reflect a combination of true improvements and high within-group variability, which is typical of small samples. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the observed effects supports the hypothesis of a substantial intervention impact, even without statistical significance.

4.2. Between-Group Comparison: Evidence in Favor of the Intervention

Between-group analyses revealed statistically significant differences favoring the experimental group in all eyes-closed stabilometric variables (Ellipse Surface: p = 0.002, r_rb = −0.54; COP Distance: p < 0.001, r_rb = −0.64; Speed: p = 0.015, r_rb = −0.47). These results indicate better postural control in the absence of visual input, consistent with the hypothesis that proprioceptive training enhances somatosensory contributions to balance.

Although BOT-2 subtests did not reach statistical significance, medium between-group effects were observed (Test 3: r_rb = +0.31; Test 4: r_rb = +0.33), suggesting favorable trends that may reach significance with larger samples or longer interventions. Overall, these findings reinforce the effectiveness of the proprioceptive–plyometric program and provide the basis for further methodological considerations discussed below.

4.3. Methodological Considerations

An important point emerging from the analysis concerns the discrepancy between statistical significance and effect size magnitude. In many cases, p-values did not fall below the conventional 0.05 threshold, yet effect sizes were large. As highlighted by Lakens (2013) [24], it is crucial not to rely solely on p-values to assess the impact of an intervention, especially in studies with small samples where statistical power is limited. Reporting both mean values and standard deviations in the tables enables readers to appreciate not only statistical significance but also the clinical relevance of the observed changes.

The strengths of this study include the following:

- the use of an experimental design with a control group;

- the application of validated measurement tools, such as the BOT-2 and stabilometric platform;

- a progressively structured protocol with a gradual increase in motor demands.

4.4. Study Limitations

The main limitations of this study are as follows:

- small sample size, which may have limited the statistical significance of some findings;

- absence of follow-up to assess the persistence of effects over time;

- individual variability in age and severity of visual impairment, which could have influenced responsiveness to the intervention;

- lack of inclusion of functional dynamic tests, such as gait assessment, reaction tests, or dynamic posturography, which could have provided further insight into the transfer of improvements to real-world contexts;

- training frequency limited to one session per week, which may have influenced the magnitude of observed improvements. However, this aspect also increases the ecological validity of the study, demonstrating that even low-frequency, well-structured protocols can yield clinically relevant changes.

Moreover, given that participants were recruited from a single specialized school, generalizability to broader populations of children and adolescents with visual impairment (e.g., mainstream school contexts or other cultural settings) remains limited. Despite these limitations, the study provides promising evidence supporting the feasibility and potential benefits of school-based proprioceptive and plyometric interventions, laying the groundwork for larger and more comprehensive trials.

4.5. Practical Implications and Future Directions

Building on these findings, the study suggests that integrating proprioceptive and plyometric exercises may represent an effective strategy to improve balance in individuals with visual impairment. Such protocols could be feasibly implemented in school, sports, or rehabilitation settings, with potential benefits not only in motor performance but also in psychological and social domains.

Future studies should address the following:

- include larger and stratified samples by age and level of impairment;

- assess functional and qualitative outcomes, such as movement autonomy, perceived stability, or improved participation;

- consider long-term effects through follow-up assessments.

A further strength of this program is its low cost and feasibility, as it requires minimal equipment and can be implemented in regular school or rehabilitation settings without specialized infrastructure. This enhances its potential for widespread application in inclusive education and rehabilitation programs.

5. Conclusions

Considering the results obtained, the present study demonstrated the effectiveness of an integrated proprioceptive and plyometric exercise protocol in improving static and dynamic balance in children and adolescents with visual impairment. The changes observed in stabilometric variables—particularly under visual deprivation conditions—indicate a significant improvement in postural control in the experimental group compared to the control group. Statistical analyses revealed large effect sizes even when statistical significance was not reached, suggesting that the program produced clinically meaningful benefits.

It is noteworthy that these improvements were achieved with only one training session per week over a 12-week period, a frequency that enhances ecological validity and feasibility for implementation in school settings. The findings support the view that targeted balance interventions can serve as an effective pedagogical and rehabilitative resource, particularly in school and inclusive contexts. Furthermore, the use of validated instruments (BOT-2, stabilometric platform) and the adoption of a structured methodology make the protocol easily replicable.

In summary, this study demonstrated that a school-based integrated program of proprioceptive and plyometric exercises can produce meaningful improvements in postural control and balance, supporting the validity of the proposed approach and paving the way for future studies with larger and more diverse samples, as well as for potential large-scale applications in educational and rehabilitative contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G., F.M. and N.M.; methodology, M.A.G., E.Á.M., R.P., G.M. and E.F.G.; software, N.M. and V.A.E.; validation, F.M., V.T.G., A.M., M.M., and N.M.; formal analysis, F.M., N.M., P.V. and V.A.E.; investigation, M.A.G., E.F.G., R.P., P.V., C.C., and E.Á.M.; resources, M.A.G., F.M., G.M. and N.M.; data curation, N.M., V.T.G., M.M. and E.F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.G., A.M., R.P. and E.Á.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G., E.Á.M., E.F.G., F.M.; visualization, N.M., P.V., V.A.E. and V.T.G.; supervision, M.A.G., F.M., G.M. and N.M.; project administration, F.M., M.M., A.M. and N.M.; funding acquisition, F.M. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Pegaso Telematic University (PROT/E 002466, 29 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to the participation of minors with visual impairment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the headteacher of the School for her support and for providing the necessary equipment and facilities. We also thank Babeș-Bolyai University and the students who collaborated in the activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement:

In this manuscript, we adopted person-first language (e.g., “children and adolescents with visual impairment”) in accordance with international recommendations and the cultural and legal context of the study, which prioritizes recognition of the person before the disability. This choice reflects both ethical considerations and current educational and rehabilitative practices in the European context.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Baseline Comparison between Experimental (EG) and Control (CG) Groups at T0.

Table A1.

Baseline Comparison between Experimental (EG) and Control (CG) Groups at T0.

| Variable | EG T0 Mean ± SD | CG T0 Mean ± SD | Mann–Whitney U | p | Rank-Biserial r_rb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ellipse Surface (EC, mm2) | 65.20 ± 49.92 | 99.88 ± 195.40 | 118.0 | 0.27 | −0.14 |

| COP Distance (EC, mm) | 47.11 ± 32.15 | 79.70 ± 55.07 | 112.5 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| Speed (EC, mm/s) | 0.0071 ± 0.0033 | 0.0080 ± 0.0055 | 124.0 | 0.41 | 0.05 |

| BOT-2 Test 3 | 1.94 ± 1.61 | 2.11 ± 1.54 | 120.0 | 0.33 | 0.18 |

| BOT-2 Test 4 | 1.83 ± 1.47 | 2.00 ± 1.36 | 119.0 | 0.30 | 0.21 |

References

- Masal, K.M.; Bhatlawande, S.; Shingade, S.D. Development of a visual to audio and tactile substitution system for mobility and orientation of visually impaired people: A review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 20387–20427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczuk, G.; Wiszomirska, I.; Rutkowska, I.; Skowroński, W. Role of vision in static balance in persons with and without visual impairments. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, A.-K.; Hamacher, D.; Cappagli, G.; Kuhne, L.; Hötting, K.; Zech, A.; Gori, M.; Röder, B. Balance, gait, and navigation performance are related to physical exercise in blind and visually impaired children and adolescents. Exp. Brain Res. 2021, 239, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipori, A.B.; Colpa, L.; Wong, A.M.F.; Cushing, S.L.; Gordon, K.A. Postural stability and visual impairment: Assessing balance in children with strabismus and amblyopia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Wong, H.Y.; Cheung, H.N.; Tseng, J.K.; Chen, C.C.; Wu, C.L.; Eng, H.; Woo, G.C.; Cheong, A.M.Y. Impact of visual impairment on balance and visual processing functions in students with special educational needs. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0249052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterlund, C.; Lundqvist, L.; Richter, H.O. Visual, musculoskeletal and balance symptoms in individuals with visual impairment. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, I.; Lieberman, L.J.; Bednarczuk, G.; Molik, B.; Kazimierska-Kowalewska, K.; Marszałek, J.; Gómez-Ruano, M.Á. Bilateral Coordination of Children who are Blind. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2016, 122, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretti, G.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Physical activity and sport practice to improve balance control of visually impaired individuals: A narrative review with future perspectives. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1260942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowska, I.; Bednarczuk, G.; Molik, B.; Morgulec-Adamowicz, N.; Marszałek, J.; Kaźmierska-Kowalewska, K.; Koc, K. Balance Functional Assessment in People with Visual Impairment. J. Hum. Kinet. 2015, 48, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walicka-Cupryś, K.; Rachwał, M.; Guzik, A.; Piwoński, P. Body Balance of Children and Youths with Visual Impairment (Pilot Study). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak-Olejnik, M.; Loba, W.; Stieler, O.; Komar, D.; Majewska, A.; Marcinkowska-Gapińska, A.; Hojan-Jezierska, D. Body Balance Analysis in the Visually Impaired Individuals Aged 18-24 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiszomirska, I.; Kaczmarczyk, K.; Błażkiewicz, M.; Wit, A. The Impact of a Vestibular-Stimulating Exercise Regime on Postural Stability in People with Visual Impairment. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 136969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granacher, U.; Behm, D.G. Relevance and Effectiveness of Combined Resistance and Balance Training to Improve Balance and Muscular Fitness in Healthy Youth and Youth Athletes: A Scoping Review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, N.; Polito, R.; Colecchia, F.P.; Colella, D.; Messina, G.; Grosu, V.T.; Messina, A.; Mancini, S.; Monda, A.; Ruberto, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Multisport Play-Based Practice on Motor Coordination in Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the KTK Test. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Salzberg, C.L.; Stevenson, D.A. A systematic review: Plyometric training programs for young children. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myer, G.D.; Ford, K.R.; McLean, S.G.; Hewett, T.E. The effects of plyometric versus dynamic stabilization and balance training on lower extremity biomechanics. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006, 34, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kons, R.L.; Orssatto, L.B.R.; Ache-Dias, J.; De Pauw, K.; Meeusen, R.; Trajano, G.S.; Pupo, J.D.; Detanico, D. Effects of Plyometric Training on Physical Performance: An Umbrella Review. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Liew, B.; Chaabene, H.; Behm, D.G.; García-Hermoso, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Granacher, U. Effects of Vertically and Horizontally Orientated Plyometric Training on Physical Performance: A Meta analytical Comparison. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, J.; Merom, D.; Astuti, P.A.S.; Antoun, M.; Edwards, K.; Ding, D. Physical activity interventions for adults who are visually impaired: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitz, J.C.; Kartin, D.; Kopp, K. Review of the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2). Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2007, 27, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düger, T.; Bumin, G.; Uyanik, M.; Aki, E.; Kayihan, H. The assessment of Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency in children. Pediatr. Rehabil. 1999, 3, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Kim, D.H. Reliability, minimum detectable change, and minimum clinically important difference of the balance subtest of the Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency-second edition in children with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 15, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczuk, G.; Bandura, W.; Rutkowska, I.; Starczewski, M. Balance Level and Fundamental Motor Skills of Youth with Visual Impairments: Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalron, A.; Fonkatz, I.; Frid, L.; Baransi, H.; Achiron, A. The effect of balance training on postural control in people with multiple sclerosis using the CAREN virtual reality system: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2016, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).