Abstract

This pilot study evaluates the effectiveness of basketball, implemented according to Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles and educational best practices, as an inclusive tool for students with Special Educational Needs in lower secondary school. The research involved 24 adolescents aged 11–14 with Special Educational Needs, who participated in a structured 30-session basketball program designed to enhance motor, relational, and individual skills. The program incorporated evidence-based methodologies such as differentiated instruction, peer modeling, and cooperative activities. Motor tests and psychometric questionnaires were administered pre- and post-intervention to assess three key developmental dimensions. Results demonstrated significant improvements across all three dimensions: relational competencies and individual factors showed equal progress (+20.8% each), while motor skills showed slightly more modest but still substantial gains (+16.6%). These findings confirm that a structured pedagogical approach can transform sport into a powerful vehicle for inclusion. The article highlights how the integration of physical activity, inclusive teaching methodologies, and unified sports represents an effective strategy to address the complexity of Special Educational Needs.

1. Introduction

The inclusion of students with Special Educational Needs represents a critical challenge for contemporary education systems. Beyond traditional pedagogical approaches, recent research highlights the potential of sports as a tool for socio-emotional and cognitive development. Basketball, with its dynamic and cooperative nature, emerges as a particularly suitable activity for promoting motor, relational, and self-regulatory skills in students with learning difficulties.

Literature demonstrates that students with Special Educational Needs require targeted interventions to address learning and socialization challenges. Studies indicate the need for specific educational adaptations, including extended test durations [1,2] and strategies to enhance linguistic and relational abilities [3]. Without adequate support, these difficulties may lead to significant consequences: research reveals high rates of psychological distress [4,5,6,7] and below-average academic performance, particularly pronounced in students with Specific Learning Disorders [8,9,10]. These challenges extend to the social sphere, where increased vulnerability to marginalization and bullying is observed [11,12,13]. In this context, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework is increasingly recognized in physical education as a reference model to design flexible and accessible learning environments for all students. UDL is structured around three fundamental principles that guide instructional design: providing multiple means of representing information, allowing diverse forms of action and expression, and offering varied opportunities for engagement and motivation, thereby responding flexibly to students’ individual differences [14,15,16,17].

The Italian educational system has developed a specific regulatory framework to address these needs. The Ministerial Directive of 27 December 2012 outlines an inclusive approach that transcends clinical diagnoses, recognizing Special Educational Needs as encompassing various situations—from specific disorders to socio-cultural disadvantages—that hinder full educational development [18]. This model involves personalized learning plans, compensatory tools, and a support network engaging schools, families, and local communities. This framework reflects the understanding that during development, learning difficulties often intertwine with emotional vulnerabilities. Peer comparison becomes crucial for self-perception, particularly in activities involving motor coordination and social interaction [19].

These considerations have led to exploring the educational potential of sports, where cognitive, emotional, and relational dimensions converge in active learning contexts. Physical activities address multiple psychological needs: from experimenting with complex motor patterns to seeking competitive gratification; from socialization to overcoming personal limitations [19,20]. This multidimensionality makes sports an ideal platform for inclusive interventions, particularly in models such as unified sports, which combine students with and without Special Educational Needs in shared activities. Unified sports programs foster inclusivity by integrating students with and without intellectual disabilities into the same teams, ensuring equal participation and skill development. Their effectiveness relies on purposeful team composition, supportive coaching, and complementary activities such as competitions and community engagement, which strengthen both social bonds and a sense of belonging [21,22,23,24,25]. Furthermore, school-based sports education is crucial for more than just physical fitness. It serves as a key tool for moral development, teaching adolescents ethical principles like fairness, sportsmanship, respect, and inclusion. This educational focus is particularly important for preventing deviant behaviors such as doping and substance abuse, as ethical decision-making in sports is formed during the teenage years [26,27]. The integration of these values into sports programs ensures a holistic approach to youth development, aligning physical activity with socio-emotional and ethical growth. Beyond ethical principles, attention to nutritional needs is equally vital, as balanced nutrition significantly impacts cognitive performance and behavioral regulation in students with Special Educational Needs [28].

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) conceptualizes inclusive education as a dynamic process of strengthening education systems’ capacity to reach all learners [29]. This global perspective views Special Educational Needs not merely as deficits to compensate for, but as opportunities to critically rethink educational practices while maintaining participatory learning as a core right. Within this perspective, UDL provides a structured pedagogical framework that translates inclusive principles into practical strategies for physical education. Schools serve as primary laboratories where these principles translate into meaningful experiences, with teacher–parent–peer relationships facilitating both world exploration and identity construction. For students with Special Educational Needs, this process requires multidimensional assessment considering individual, relational, and contextual factors [30].

Inclusion thus emerges as a systemic phenomenon transcending classroom boundaries [31]. As Banks et al. (2015) note, schools represent privileged testing grounds for relational models integrating individual differences into collective projects, fostering citizenship competencies [32]. While schools remain central to educational inclusion, extracurricular activities, particularly sports, provide complementary spaces for embodied learning. Research demonstrates sports’ role in emotional regulation, socialization, and identity formation [33]. This multifactorial effect transforms physical activity into an experiential laboratory integrating physical, cognitive, and affective development, with play serving as a privileged learning channel [34,35,36].

Among sports, basketball stands out for translating these theoretical principles into practical opportunities. Its unpredictable, dynamic nature makes it an exemplary situational sport requiring rapid adaptation, tactical thinking, and cooperation [37]. These characteristics simultaneously stimulate executive functions, spatiotemporal coordination, and relational intelligence [38]. The emotional spectrum of sports, from enthusiasm to frustration, fosters resilience and self-control [39].

Translating these theoretical potentials into tangible outcomes requires implementing best practices: structured environments, positive relationships, and careful pedagogical mediation are essential to transform basketball from mere physical activity to a true inclusive development tool. Particular attention must be paid to preventing distress and valuing individual differences, as inclusion is measured in actions, not declarations.

Building upon this theoretical framework, the present study investigates basketball’s potential as an educational tool for students with Special Educational Needs in lower secondary school through a multidimensional assessment employing educational best practices. The research design evaluates motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors, while examining how the sport’s unique characteristics—from spatial management to cooperative dynamics—can simultaneously address these interconnected developmental dimensions. This approach offers a holistic perspective on inclusive education through structured sports pedagogy. Given the lack of evidence in this area, the present work was conceived as a pilot study to explore the feasibility and potential benefits of an inclusive motor program based on three domains: motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as an exploratory pilot school-based intervention, aimed at identifying the needs of students with special educational needs and evaluating the effectiveness of an inclusive motor program. This model was selected because it allows the integration of preliminary classroom observations, validated psychometric instruments, and standardized motor tests, which were organized into three main domains (motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors). Such a multidimensional approach makes it possible to obtain a comprehensive evaluation that goes beyond motor performance alone, including relational and individual aspects as well, in line with the objectives of inclusion and the promotion of well-being within the school community.

2.1. Participants

The study involved a sample of 24 adolescents (15 males, 9 females) aged 11 to 14 years, recruited during the September 2024 to February 2025 period from lower secondary schools in the Naples metropolitan area (total students: 769). Of the 24 participants with Special Educational Needs, sixteen were certified with Specific Learning Disorders (SLD), four primarily exhibited Attentional Difficulties and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and the remaining four were in a situation of socioeconomic and linguistic disadvantage that hindered their regular learning. Crucially, no participants in the sample had a diagnosed intellectual disability. This ensured that the validity and reliability of the psychometric instruments, which required a baseline level of cognitive and comprehension ability, were not compromised. Recruitment was conducted in collaboration with the participants’ schools, following evaluation by teachers and reference specialists.

The inclusion criteria required: (1) Special Educational Needs certification, (2) regular participation in amateur sports activities, particularly basketball, and (3) absence of medical contraindications to sports participation. All participants were enrolled in the study after obtaining written informed consent from parents/guardians, in compliance with ethical standards and privacy regulations.

The decision to focus the intervention on young amateur basketball players helped ensure some homogeneity in familiarity with the chosen sport, facilitating program adherence and implementation of the planned methodologies.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, University of Naples Federico II (protocol n. 200/17), in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Instruments and Evaluation

A one-month preliminary classroom observation was conducted to identify the main needs of students with Special Educational Needs. This phase made use of the AMOS 8–15 battery [40]. Its validation studies, conducted on a representative Italian school population, have demonstrated good levels of reliability and validity. The battery is particularly suitable for identifying learning profiles and specific difficulties, making it appropriate for the preliminary screening of needs in a school-based Special Educational Needs population, as intended in this study. The evaluation combined psychometric instruments, self-report tools, and standardized motor tests, providing a multidimensional assessment organized into three domains: motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors.

For the assessment of motor skills, coordination, and precision in basketball-specific tasks, such as passing and shooting accuracy, were measured using standardized tests from Marella and Risaliti’s (2007) compilation [41]. This source provides a collection of field-based motor tests, including protocols for evaluating sport-specific skills. The chosen tests are designed for practical use in physical education and youth sports environments, providing structured and objective assessments of motor performance.

Explosive strength was assessed using the Sargent Jump Test, which evaluated lower limb power and reactivity according to standardized protocols outlined by Weineck (2000) [42]. This authoritative text on basketball conditioning provides scientifically grounded methodologies for athlete assessment, and the Sargent Jump Test is presented therein as a valid and reliable field test for measuring lower-body explosive power in sport-specific contexts, including basketball. The parameters considered included the number and percentage of successful executions in lineouts, passes, and shots, as well as jump performance.

For relational competencies, the conflict-management questionnaire and relational self-reports were combined with group-based methods such as Circle Time and Role Playing. The Circle Time approach was based on the foundational work of Brandani and Rizzardi (2005) [43], which offers a structured framework for guiding group discussions in educational settings. This text is a well-known guide in the Italian pedagogical context for promoting communication, active listening, and group cohesion, making it a suitable reference for creating a supportive environment to assess and develop relational skills among adolescents. These tools enabled the evaluation of collaboration, conflict management, peer relationships, communication skills, and participation in group activities, providing a comprehensive view of socio-emotional functioning. The cooperative group activities at the core of the intervention were designed following the principles of Cooperative Learning as outlined by Comoglio and Cardoso (1996) [44]. This work is a key reference in Italian pedagogy, offering a validated theoretical and operational model for fostering positive interdependence and promotive interaction within small groups, thus creating the ideal conditions for developing and observing the relational competencies under study.

For the individual factors, the Multidimensional Self-Esteem Test, a validated tool for children and adolescents, was used to measure both positive and negative self-esteem. This instrument, developed and validated by Bracken (2003) [45] for young people, assesses six distinct areas of self-concept (interpersonal, academic, family, emotional, physical, and overall). Its multidimensional design and strong psychometric properties, confirmed through thorough validation studies on normative youth groups, make it a comprehensive and suitable instrument for capturing the complex nature of self-esteem in the adolescent participants of this study.

The Personal Lifestyle Assessment Test assessed lifestyle patterns and psychosocial well-being. This instrument, developed by Varriale (1995) [46] specifically for preadolescents, evaluates key lifestyle areas such as interpersonal relationships, management of free time, and personal well-being. Its design and validation for the 11–14 age bracket make it a contextually appropriate tool for capturing the lifestyle patterns and psychosocial dimensions relevant to the participants in this study.

A conflict-management questionnaire, administered via Google Forms, explored causes, emotions, and strategies related to conflict episodes. Additional qualitative tools, such as classroom drawings and self-reports (“What I think about myself”, “My class”), complemented the quantitative data by capturing self-perception and classroom dynamics. The use of positive reinforcement strategies was also informed by previous pedagogical work on enhancing self-concept and motivation in educational contexts. Specifically, we drew upon the practical framework provided by Canfield and Wells (1994) [47], a seminal text in educational psychology that offers a wide array of structured activities and techniques designed to strengthen self-concept and intrinsic motivation in students. While not a psychometric instrument, its evidence-based strategies provided a validated pedagogical foundation for creating a supportive and motivating learning environment throughout the intervention, thereby indirectly supporting the development of the individual factors we aimed to measure.

All instruments were administered before and after the intervention under the supervision of teachers and researchers. Data collection combined paper-based protocols and online questionnaires (Google Forms) to facilitate participation and ensure privacy. Data entry was performed in Microsoft Excel, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Improvements were expressed as relative gains or as percentage reductions in reported difficulties across the three domains.

Table 1 summarizes the variables and parameters evaluated within the three domains: motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors.

Table 1.

Assessment dimensions, parameters, and tests used.

2.3. Training

The motor program, structured into thirty afternoon sessions [42], was designed using an inclusive approach consistent with UDL principles and educational best practices and involved coordinated participation of students with and without Special Educational Needs. The session duration (45–60 min) was calibrated to balance physical effort and psychological sustainability, with work groups of 4–5 participants where at least one member did not have Special Educational Needs, fostering natural peer modeling processes.

The initial phase (sessions 1–4) focused on theoretical-practical group formation, with particular attention to creating a collaborative and safe environment. Through guided discussions and basic drills, the foundations for team cohesion and mutual trust were laid.

The skill acquisition phase (sessions 5–12) emphasized the development of coordinative and conditional abilities. This was achieved primarily through circuit training that alternated technical exercises (dribbling, passing) with physical drills (endurance, speed), using specific equipment such as balls, cones, and resistance bands.

A core module of the program (sessions 13–16) strategically integrated free play with structured emotional verbalization moments. These consisted of brief, instructor-led debriefing sessions immediately following activities, where students were guided with specific prompts (e.g., “What was the strongest emotion you felt during that drill?”, “How did you feel when a teammate helped you?”) to help them identify, name, and share their emotional experiences, thereby translating motor experiences into self-awareness.

Parallel sessions (sessions 17–20) were dedicated to learning game rules and role specialization. Through situational exercises, instructional videos, and the analysis of simplified tactical schemes, participants developed a deeper understanding of the game’s logic, while also fostering a sense of identity and responsibility within the team.

The advanced problem-solving phase (sessions 21–26) introduced complex and unexpected game situations, designed to stimulate tactical thinking and collaborative problem-solving in dynamic scenarios. Themed games and the introduction of constraints or unexpected obstacles required the adolescents to find creative solutions together, strengthening communication and mutual trust.

The final sessions (27–30) combined comprehensive practical simulations with technological aids (such as a PlayStation console for movement analysis) and guided reflective activities using the circle-time technique. The latter were structured sessions where participants, seated in a circle to promote equality and active listening, reflected on a starting prompt (e.g., “Today I learned that…”, “A quality I appreciated in a teammate is…”) in a turn-taking format sometimes regulated by a talking piece, creating a safe space for shared reflection. Each simulation was followed by a collective performance analysis: trained external observers (research team members) used a standardized checklist to code observable behaviors (e.g., “initiates communication with a peer”, “encourages”). The collected, anonymized data were not used for individual assessment but served as the basis for an immediate group debriefing, focusing the discussion on observable dynamics and strategies for improving collective performance.

A summary of the training program phases is provided in Table 2. The entire intervention was monitored through standardized motor tests and psychological questionnaires administered before and after the program, allowing for a systematic evaluation of improvements in the students’ initial difficulties across all target domains.

Table 2.

Summary of the training program phases, including session numbers, main objectives, methodologies, and required equipment.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted to estimate the average change in the perceived level of difficulty among students with Special Educational Needs involved in the program. The calculation of the difficulty percentage (DP) for each of the three investigated dimensions (motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors) was obtained by synthesizing the results of all participants.

For each student with Special Educational Needs, the raw scores recorded in the different tests and questionnaires were converted into a DP. Given the heterogeneous nature of the assessment tools, which produced scores on different scales, a unified metric was necessary to enable a comparative analysis of improvement across the three developmental dimensions. Therefore, the raw scores from all tests and questionnaires were converted into a DP, where a higher percentage consistently represents a greater level of difficulty or poorer performance.

The conversion was performed using distinct approaches for motor tests and psychometric instruments. For motor skills tests, such as the Sargent Jump and passing/shooting accuracy tasks, a higher raw score indicates better performance. The DP was calculated to reflect the performance gap relative to an external normative benchmark. Specifically, for the Sargent Jump, benchmark values were derived from average reference data for sex and age [48], using the formula:

DP = [1 − (Raw Score/Reference Score)] × 100.

This method contextualizes an individual’s performance against recognized standards for their demographic.

For psychometric questionnaires and self-reports, a higher raw score indicates greater challenges. Here, the conversion utilized each instrument’s predefined maximum possible score, calculated as:

DP = (Raw Score/Maximum Possible Test Score) × 100.

This approach leverages the standardized, theory-driven scaling inherent to the validated psychometric instruments.

Subsequently, the overall DP for each dimension was calculated as the average of the DPs of all students with Special Educational Needs for the set of tests about that specific area. The percentage variation between the pre-intervention and post-intervention averages was used to quantify the average improvement of the group as a whole.

Given the exploratory nature of this pilot study, which aimed to evaluate the feasibility of the program and generate hypotheses for future research, the analysis focused on describing the results through the calculation of arithmetic means and relative percentage variations. These approaches were considered sufficient and appropriate for the project’s purpose. No inferential statistical tests were applied, given the small sample size and the exploratory design of this pilot study, as such analyses would not yield reliable results. These tests are planned for future studies with larger cohorts.

3. Results

The results from the standardized motor tests and psychometric questionnaires, administered before and after the intervention program, show a significant reduction in the average level of difficulty for students with Special Educational Needs across the three investigated dimensions. The percentage difficulty values for each dimension are derived from the average results obtained by the entire group of students with Special Educational Needs across the different specific tests for each area, thus providing a synthetic measure of performance.

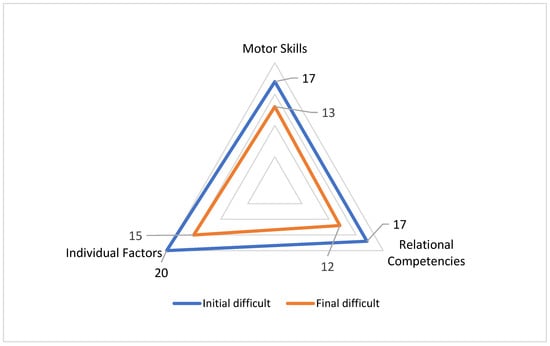

As highlighted in Table 3, the analysis of these indicators reveals that the most consistent improvements concern the psychosocial sphere. Both relational competencies and individual factors show an identical reduction in difficulty of 20.8%, indicating that the program acted in a balanced manner to enhance socio-emotional skills and personal development. The motor domain also shows significant progress, with a 16.6% reduction in initial difficulties. This improvement, although numerically lower, remains substantial and demonstrates the effectiveness of structured sports activity in promoting physical development alongside psychosocial growth. This descriptive analysis was considered appropriate for the main objective of the study, which was to evaluate the feasibility and to generate preliminary evidence, rather than to test hypotheses.

Table 3.

Results of the standardized motor tests and psychometric questionnaires administered before and after the intervention program. The values are expressed as percentages of difficulty, obtained by converting the raw scores of the different instruments to homogenize the measurement scales. For tests expressed in physical units, the table reports the original pre- and post-intervention values together with the relative percentage variation (Δ%) compared to the baseline. Higher percentages correspond to greater levels of difficulty.

Systematic observations during sessions detected relevant behavioral changes. Many participants developed greater initiative in social interactions, while teachers reported increased active participation in classroom activities. Families, for their part, noted tangible improvements in emotional self-regulation among the students.

Figure 1 completes this picture by showing the evolution in the number of students experiencing difficulties across the assessed parameters. The graphical analysis confirms a generalized reduction in critical issues, while motor improvements, though present, appear more gradual and varied among participants.

Figure 1.

Number of students with Special Educational Needs reporting difficulties pre- vs. post-intervention across key domains: motor skills, relational competencies, and individual factors.

4. Discussion

Sport serves as a powerful driver for comprehensive personal development, offering benefits that extend beyond purely physical aspects. At the physiological level, numerous scientific studies demonstrate its crucial role in preventing metabolic diseases (diabetes, obesity) and cardiovascular disorders, as well as improving overall quality and life expectancy [49,50]. Particularly significant is the protective effect of regular physical activity, especially when introduced early in educational settings.

School-based sports education, therefore, takes on paradigmatic value: beyond physical benefits, it represents a unique opportunity to instill in young people the ethical principles of fairness, sportsmanship, respect, and inclusion. This educational aspect also proves fundamental in preventing deviant behaviors like doping [51,52,53] and substance abuse [54,55,56], especially considering that ethical choices in sport develop during adolescence.

This study examined the effects of a structured adapted basketball program on 24 students with Special Educational Needs in a lower secondary school. Through a mixed-method approach (standardized motor assessments, psycho-relational questionnaires, and qualitative observations) conducted at the beginning and end of the training program, we investigated three key dimensions: motor skills, relational abilities, and individual factors. The intervention was designed following UDL principles and educational best practices for inclusion, featuring differentiated instruction in activities, use of positive feedback, creation of heterogeneous groups, and progressive adaptation of difficulties.

In motor skills, the overall improvement (+16.6%), though slightly more modest compared to other dimensions, confirms the program’s effectiveness in supporting foundational physical development, particularly for students with limited prior exposure to structured sports activities.

While isolated technical fundamentals (dribbling, passing) respond quickly to targeted training, as demonstrated by Radenković et al. (2014) in their basketball program for students with Special Educational Needs, complex motor abilities require longer timeframes and specific strategies [57]. The obtained results find significant parallels in the literature: Selmanović et al. (2013) showed how combined basketball–volleyball programs can enhance not only coordination (hand movement frequency) but also parameters like explosive power and dynamic strength [58]. These findings collectively indicate, as highlighted by Roşu et al. (2024), that the effectiveness of motor interventions for students with Special Educational Needs also depends on activity personalization and sufficient duration to consolidate complex motor abilities [59], which in this study still showed room for improvement.

The marked progress in relational competencies (+20.8%) underscores basketball’s potential as a social training tool. The cooperative structure of activities, combined with peer modeling, created an inclusive environment to manage conflicts and strengthen group dynamics. The strategic presence of teammates without Special Educational Needs during training, combined with the cooperative structure of the activities, has demonstrated the possibility of creating an inclusive space to overcome inhibitions and manage conflicts. Qualitative observations revealed not only improved group dynamics but also a newfound ability to reflect on these shared experiences.

These findings align with broader research on sports as an inclusive tool, including the growing field of unified sports, which institutionalizes shared participation between students with and without Special Educational Needs. Numerous studies have shown how adapted sports, with their modified rules and personalized approaches [60,61], represent a fundamental resource for promoting participation and psychosocial development [62]. A notable example is Baskin, born from the fusion of “basketball” and “inclusion” [63]. This sport, with its adapted rules and differentiated roles, has become a recognized “best practice” in Italy, even being formally linked to the law on school inclusion. Research demonstrates that Baskin fosters prosocial behaviors, empathy, and well-being while simultaneously enhancing motor, relational, and emotional skills, particularly in students with disabilities [64,65].

This study adds to the evidence by showing that even traditional sports like basketball, when delivered with teaching methodologies sensitive to diversity, can achieve significant inclusion outcomes. Literature emphasizes that inclusive effectiveness depends more on the pedagogical approach than the sport itself [66]. As highlighted by Brown (2019) [67] and Valentina et al. (2018) [68], key elements such as valuing individual progress, creating non-judgmental environments, and focusing on processes over results prove decisive in fostering the sense of belonging and self-efficacy that also emerged in this study.

The improvements observed in individual factors (+20.8%) do not represent isolated outcomes but rather form the foundation for broader change within the educational context. This progress, coupled with enhanced expressive abilities observed in the classroom, demonstrates how structured sports can initiate a virtuous cycle: the strengthening of personal competencies fosters more active and confident participation in learning activities, which in turn reinforces a sense of belonging and inclusion [69].

However, for these individual benefits to translate into tangible progress toward systemic inclusion, the school environment must be prepared to accommodate and support them. The effectiveness of approaches such as co-teaching [70,71] and peer tutoring [72,73] in promoting socialization and engagement is closely tied to the school’s ability to adapt methodologies, spaces, and resources. Persistent challenges—such as inadequate infrastructure, inconsistent teacher training, and a lack of specialized materials—risk limiting not only the generalization of individual progress but also the sustainability of inclusive interventions [74,75,76]. For future research, it would be advisable to expand studies to larger and more diverse samples; explore the model’s applicability to other sports; and evaluate long-term effects. Investments in teacher training and structural resources could amplify the impact of such interventions, fostering a genuine culture of inclusion.

Therefore, the transformative potential highlighted by individual improvements requires consistent systemic commitment. Targeted educational policies, investments in teacher training, and collaborative planning among schools, families, and local communities become essential to translate individual successes into a widespread and lasting model of inclusion. Only then can the positive experience of individual students evolve into genuine cultural and organizational change, benefiting the entire educational community.

Limitations and Future Perspectives

Although this study provides promising results on the potential of adapted basketball as an inclusive educational tool for students with Special Educational Needs, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 24) and the focus on a specific age group (11–14 years) may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations or different educational contexts. This appears to be a quasi-experimental design (pre-test/post-test without a control group). While it can show changes, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of not having a control group to rule out other factors. Additionally, the relatively short duration of the intervention (30 sessions) might not fully capture the long-term effects of such programs on student development. Future research could benefit from larger, more heterogeneous samples and longer intervention periods to confirm these preliminary results.

Another aspect to consider concerns the methodological choices made, which prioritized participant well-being through the use of low-emotional-impact tools. While this approach ensured a serene and inclusive environment during the study, future research could explore the gradual integration of more structured tools, always maintaining a primary focus on the participants’ comfort zone.

Furthermore, the decision not to differentiate participants based on the type of Special Educational Needs allowed for a unified and cohesive experience, although a more targeted analysis in future studies could provide additional insights for personalizing educational interventions.

Another limitation concerns the use of assessment instruments that, while validated in general youth populations, have not yet been specifically validated for students with Special Educational Needs. Although the instruments showed good feasibility and sensitivity in this pilot study, future research should consider validation studies in specific populations with Special Educational Needs to strengthen the reliability of results further.

The results obtained pave the way for future experimentation with other team sports (volleyball, soccer) and the creation of integrated models that combine motor activities, pedagogical approaches, and school-territory collaborations to respond more effectively to the diverse types of Special Educational Needs. As this was a pilot study, the results should be interpreted with caution, and further research with larger samples is needed to confirm these findings.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this pilot study demonstrate the effectiveness of a structured, adapted basketball program in promoting the holistic development of students with Special Educational Needs, following UDL principles and evidence-based educational practices. The analysis revealed identical improvement rates in both relational competencies and individual factors (+20.8% each), while motor skills showed slightly more modest but still significant progress (+16.6%). This pattern underscores how the program’s cooperative framework particularly enhanced psychosocial dimensions while simultaneously supporting physical development.

These results confirm that inclusion through sport is not a spontaneous process, but rather requires careful pedagogical planning, supportive environments, and close collaboration among schools, families, and communities. Peer integration and activity adaptation emerged as key elements in transforming sports practice into a meaningful educational experience.

For future research, it would be advisable to expand studies to larger and more diverse samples, explore the model’s applicability to other sports, and evaluate long-term effects. Investments in teacher training and structural resources could amplify the impact of such interventions, fostering a genuine culture of inclusion. This study helps highlight the potential of sport, and in particular unified sports, as a tool for comprehensive growth, capable of combining physical wellbeing, socio-emotional development, and educational success for students with Special Educational Needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and P.M.; Methodology, M.R., C.M.; Software, L.F.; Validation, F.M. and O.S.; Formal Analysis, M.R.; Investigation, P.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.R. and F.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.R., F.M. and O.S.; Supervision, F.M. and O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by grants from University of Naples Parthenope. Bando di Ricerca Locale D.R. 474, 06.06.2023 CUP143C23000160005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association and was approved by ethics committee (protocol 200/17, 1 December 2017) of the School of Medicine, University of Naples Federico II.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study by the participant’s legal guardian/next of kin.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, F.M., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation of the players in supporting this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

In this manuscript, we adopted person-first language (e.g., “students with Special Educational Needs (SEN)”, “students with disabilities”) in line with current educational and pedagogical conventions in the European context. This choice reflects a commitment to emphasizing the individuality of students before their condition, in accordance with inclusive education policies and legal frameworks that prioritize equity and participation. The use of person-first terminology is also consistent with the disciplinary tradition in pedagogy and special education, where the focus is placed on the learner as an individual with rights, potential, and agency, rather than on the disability itself.

References

- Lovett, B.J.; Nelson, J.M. Systematic Review: Educational Accommodations for Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pang, F.; Sin, K.F. Examining the Complex Connections Between Teacher Attitudes, Intentions, Behaviors, and Competencies of SEN Students in Inclusive Education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 144, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.; Risley, S.; Combs, A.; Lacey, H.M.; Hamik, E.; Fershtman, C.; Kneeskern, E.; Patel, M.; Crosby, L.; Hood, A.M.; et al. School Challenges and Services Related to Executive Functioning for Fully Included Middle Schoolers with Autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2023, 38, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaux, R.; Dvorsky, M.R.; Marsh, N.P.; Green, C.D.; Cash, A.R.; Shroff, D.M.; Buchen, N.; Langberg, J.M.; Becker, S.P. Prospective Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Functioning in Adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective Role of Emotion Regulation Abilities. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Salim, E.E.; Mackay, D.F.; Henderson, A.; Kinnear, D.; Clark, D.; King, A.; McLay, J.S.; Cooper, S.-A.; Pell, J.P. Neurodevelopmental Multimorbidity and Educational Outcomes of Scottish Schoolchildren: A Population-Based Record Linkage Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordmo, M.; Kinge, J.M.; Reme, B.-A.; Flatø, M.; Surén, P.; Wörn, J.; Magnus, P.; Stoltenberg, C.; Torvik, F.A. The Educational Burden of Disease: A Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e549–e556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, L.; Coey, P.; Wilson, C. Suicidality in Autistic Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 93, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, L.E.; Hodgkins, P.; Kahle, J.; Madhoo, M.; Kewley, G. Long-Term Outcomes of ADHD: Academic Achievement and Performance. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J.; Ziviani, J.; Rodger, S. Surviving in the Mainstream: Capacity of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders to Perform Academically and Regulate Their Emotions and Behavior at School. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010, 4, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Wang, H.; Dill, S.-E.; Boswell, M.; Pang, X.; Singh, M.; Rozelle, S. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among Elementary Students in Rural China: Prevalence, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, C.K.; Demaray, M.K.; Smith, T.J.; Emmons, J. Disability, Poverty, and Other Risk Factors Associated with Involvement in Bullying Behaviors. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 78, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamas, C.; Daly, A.J.; Cohen, S.R.; Jones, G. Social Participation of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in General Education Settings. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2021, 28, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi-Ugav, O.; Zach, S.; Zeev, A. Socioemotional Characteristics of Children with and Without Learning Disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2022, 45, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, S. Universal Design for Learning. J. Educ. 2023, 203, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T.M.; Rose, M.C. Exploring Universal Design for Learning as an Accessibility Tool in Higher Education: A Review of the Current Literature. Aust. Educ. Res. 2022, 49, 1025–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybayon, G. The Use of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Framework in Teaching and Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Acad. Lett. 2021, 692, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M. Enhancing the Online Student Experience through the Application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to Research Methods Learning and Teaching. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 2767–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rio, L.; Damiani, P.; Gomez Paloma, F. Physical Activities and Special Educational Needs. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2015, 10, S447–S454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.A.; Weydahl, A. Chronotype, Physical Activity, and Sport Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Onofrio, V.; Montesano, P.; Mazzeo, F. Physical-Technical Conditions, Coaching and Nutrition: An Integrated Approach to Promote Cohesion in Sports Team. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, S981–S990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart Barnett, J.E. Promoting Social Connections for Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Through Unified Sports. Teach. Except. Child. 2025, 00400599251340642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, R.; Dowling, S.; Hassan, D.; Menke, S. Promoting Social Inclusion through Unified Sports for Youth with Intellectual Disabilities: A Five-nation Study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Siwach, G.; Belyakova, Y. The Special Olympics Unified Champion Schools Program and High School Completion. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 59, 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, D.; Baran, F.; Aktop, A.; Nalbant, S.; Ağlamış, E.; Hutzler, Y. Effects of a Special Olympics Unified Sports Soccer Program on Psycho-Social Attributes of Youth with and Without Intellectual Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilski, M.; Urbański, P.; Ossian, R.; Papp Eniko, G.; Bracanovic Milovic, N.; Radovic, I.; Sedlackova, V.; Gazova, E.; Sabanovic, N.; Delic Selimovic, K.; et al. Coaching Unified Sports: Associations between Perceived Athlete Improvement, Barriers, and Coach Attitudes across Five European Countries. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1632589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, F.; Mallia, L.; Alivernini, F.; Chirico, A.; Manganelli, S.; Galli, F.; Biasi, V.; Zelli, A. The Effectiveness of a New School-Based Media Literacy Intervention on Adolescents’ Doping Attitudes and Supplements Use. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwiczak, M.; Bronikowska, M. Fair Play in a Context of Physical Education and Sports Behaviours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, M.L.; Tafuri, D.; Donini, L.; Masucci, M.T.; De Falco, V.; Mazzeo, F. The Role of Nutrients in Prevention, Treatment and Post-Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, S.; Ten Braak, D.; Munthe, E. Inclusion of Students with Special Education Needs in Nordic Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 68, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Physical Education and Sport in Schools: A Review of Benefits and Outcomes. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianes, D.; Zagni, B. Inclusione scolastica in Italia, inclusioscetticismo, difficoltà epistemologiche e metodologiche della ricerca. Ital. J. Spec. Educ. Incl. 2024, 12, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Frawley, D.; McCoy, S. Achieving Inclusion? Effective Resourcing of Students with Special Educational Needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Autoefficacia. Teorie e Applicazioni; Erickson Edizioni: Trento, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Di Palma, D.; Di Lorenzo, G. Analysis of the Socio-Pedagogical Aspects in the Relationship Between Motor-Sports Sciences and Specific Learning Disorders. Int. J. Educ. Eval. 2023, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Montesano, P.; Mazzeo, F. Improvement in Soccer Learning and Methodology for Young Athletes. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, P.; Mazzeo, F. Pilates Improvement the Individual Basics of Service and Smash in Volleyball. SMJ 2018, 16, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, L.; Gómez Ruano, M.Á.; Ortega Toro, E.; Ibañez Godoy, S.J.; Sampaio, J. Game Related Statistics Which Discriminate between Winning and Losing Under-16 Male Basketball Games. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2010, 9, 664–668. [Google Scholar]

- Erčulj, F.; Štrumbelj, E. Basketball Shot Types and Shot Success in Different Levels of Competitive Basketball. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molisso, V.; Ascione, A.; Di Palma, D. Apprendere ad apprendere: Una proposta Pedagogica in ambito Scientifico per i DsA. Ital. J. Health Educ. Sport Incl. Didact. 2019, 3, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornoldi, C.; De Beni, R.; Zamperlin, C.; Meneghetti, C. Test AMOS 8–15—Abilità e Motivazione Allo Studio: Prove Di Valutazione per Ragazzi Dagli 8 Ai 15 Anni; Erickson Edizioni: Trento, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marella, M.; Risaliti, M. Il Libro Dei Test; Correre: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weineck, J. La Preparazione Fisica Ottimale Del Giocatore Di Pallacanestro; Calzetti e Mariucci: Perugia, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brandani, A.; Rizzardi, M. Circle Time. Il Gruppo Della Pratica Educativa; Editografica: Rastignano, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Comoglio, M.; Cardoso, M.A. Insegnare e Apprendere in Gruppo. Il Cooperative Learning; LAS: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, B.A. TMA. Test Di Valutazione Multidimensionale Dell’autostima; Edizioni Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Varriale, C. Il Test Di Valutazione Dello Stile Di Vita Del Preadolescente (T.V. S.V. P. ’91); Criteri di costruzione e rilievi normativi, Atti V Congr. Naz.; SIPI: Stresa, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, J.; Wells, H.C. 100 Ways to Enhance Self-Concept in the Classroom; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Correa-Bautista, J.E.; Lobelo, F.; Cadore, E.L.; Alonso-Martinez, A.M.; Izquierdo, M. Vertical Jump and Leg Power Normative Data for Colombian Schoolchildren Aged 9–17.9 Years: The FUPRECOL Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, M.; Motti, M.L.; Meccariello, R.; Mazzeo, F. Resveratrol and Physical Activity: A Successful Combination for the Maintenance of Health and Wellbeing? Nutrients 2025, 17, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, F. Current Concept of Obesity. Sport Sci. 2016, 9, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo, F. Drug Abuse in Elite Athletes: Doping in Sports. Sport Sci. 2016, 9, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo, F.; Raiola, G. An Investigation of Drugs Abuse in Sport Performance. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2018, 13, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, M.; Ferrante, L.; Tafuri, D.; Meccariello, R.; Mazzeo, F. Trends in Antidepressant, Anxiolytic, and Cannabinoid Use Among Italian Elite Athletes (2011–2023): A Longitudinal Anti-Doping Analysis. Sports 2025, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, L.; D’Ambra, C.; Mazzeo, F.; Capuano, A.; Del Franco, F.; Avolio, A.; Ambrosino, F. Naltrexone plus Benzodiazepine Aids Abstinence in Opioid-Dependent Patients. Life Sci. 2005, 77, 2717–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccelli, C.; Della Casa, E.; Paternoster, M.; Niola, M.; Pieri, M. Gender Differences in Drug Abuse in the Forensic Toxicological Approach. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 265, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motola, G.; Russo, F.; Mazzeo, F.; Rinaldi, B.; Capuano, A.; Rossi, F.; Filippelli, A. Over-the-Counter Oral Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: A Pharmacoepidemiologic Study in Southern Italy. Adv. Ther. 2001, 18, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radenković, M.; Berić, D.; Kocić, M. The Influence of the Elements of Basketball on the Development of Motor Skills in Children with Special Needs. Facta Univ.-Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport 2014, 12, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Selmanović, A.; Milanović, D.; Custonja, Z. Effects of an Additional Basketball and Volleyball Program on Motor Abilities of Fifth Grade Elementary School Students. Coll. Antropol. 2013, 37, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Roșu, D.; Cojanu, F.; Vișan, P.-F.; Samarescu, N.; Ene, M.A.; Muntean, R.-I.; Ursu, V.E. Structured Program for Developing the Psychomotor Skills of Institutionalized Children with Special Educational Needs. Children 2024, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrascan, G.; Ștefănică, V. Football-Specific Motor Training Program Adapted to Children with SEN Aged 16–18. Discobolul—Phys. Educ. Sport Kinetotherapy 2019, 15, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.S. Nurturing Sustainable and Inclusive Learning Ecosystems: A Glimpse into the Future of Indian Education. In Advances in Educational Marketing, Administration, and Leadership; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 256–277. ISBN 979-8-3693-1536-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cătănescu, A.C.; Muntean, R.I. Enhancing Social Inclusion through Adapted Football: Exploring Effective Teaching Strategies for Children with Special Educational Needs in Institutionalized Settings. Timis. Phys. Educ. Rehabil. J. 2024, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodini, A.; Capellini, F.; Magnanini, A. Baskin…: Uno Sport per Tutti: Fondamenti Teorici, Metodologici e Progettuali; F. Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-88-568-3036-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cioni, L.; Ferraro, A.; Magnanini, A. The Inclusive Value of Baskin in Schools: A Quasi-Experimental Study on Attitudes Toward Disability. Ital. J. Health Educ. Sport Incl. Didact. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, D.; Amatori, S.; Bensi, R.; Vandoni, M.; Calavalle, A.R.; Gervasi, M.; Lauciello, R.; Montomoli, C.; Rocchi, M.B.L. Baskin—A New Basketball-Based Sport for Reverse-Integration of Athletes with Disabilities: An Analysis of the Relative Importance of Player Roles. Sport Soc. 2021, 24, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J.; Lessard, L.M.; Rastogi, R.; Schacter, H.L.; Smith, D.S. Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. How to Be an Inclusive Leader: Your Role in Creating Cultures of Belonging Where Everyone Can Thrive; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Valentina, S.; Daniel, R. Evaluation of the Working Groups in the Group Cohesion Perspective, in the Project Boboc Camp, 2018. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 2134–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rakaa, O.; Bassiri, M.; Lotfi, S. Adapted Pedagogical Strategies in Inclusive Physical Education for Students with Special Educational Needs: A Systematic Review. Pedagog. Phys. Cult. Sports 2025, 29, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, M.A. Coteaching in Physical Education: A Strategy for Inclusive Practice. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.R.; Munster, M.D.A.V. Coensino e Educação Física Escolar: Intervenções Voltadas à Inclusão de Estudantes Com Deficiência. Rev. Educ. Espec. 2021, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, C.M.; Lieberman, L.J.; Magnesio, B.; Wood, J. Peer Tutoring: Meeting the Demands of Inclusion in Physical Education Today. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2013, 84, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, K.; Olson, L. Promoting Social Acceptance and Inclusion in Physical Education. Teach. Except. Child. 2021, 54, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafleh, E.A.; Alnaqbi, F.A.; Almaeeni, H.A.; Faqeeh, S.; Alzaabi, M.A.; Al Zaman, K. The Role of Wearable Devices in Chronic Disease Monitoring and Patient Care: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e68921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomistek, K.; Johnson, N.; Stevenson, R.; Luca, N.; Miettunen, P.; Benseler, S.M.; Veeramreddy, D.; Schmeling, H. Patient-Reported Barriers at School for Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019, 1, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalsen, H.; Henriksen, A.; Hartvigtsen, G.; Olsen, M.I.; Pedersen, E.R.; Søndenaa, E.; Jahnsen, R.B.; Anke, A. Barriers to Physical Activity Participation for Adults with Intellectual Disability: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2024, 37, e13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).