Abstract

Ramie fabrics suffer from inherent prickle sensation due to rigid fiber morphology, limiting their applications. This study aims to alleviate this issue through an eco-friendly enzymatic modification. Six enzymes (cellulase, laccase, hemicellulase, xylanase, pectinase, alkaline protease) were used. Single-factor experiments optimized enzyme dosage, liquid-to-solid ratio, and treatment time; response surface methodology (RSM) further refined conditions, followed by compound enzyme treatments to explore synergies. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) validated changes. Results showed the optimal multi-enzyme combination (2% hemicellulase, 3% cellulase, 3% laccase) reduced prickle sensation score by 43.8% (to 1.8 vs. 3.2 for untreated), with SEM confirming less surface fuzz and improved uniformity. This effective enzymatic strategy provides a green approach to enhance ramie fabric comfort, with practical implications for textile processing.

1. Introduction

The enhancement of wearing comfort has emerged as a central challenge in the textile industry, particularly for natural fiber materials [1,2]. Ramie and other bast fabrics, valued for their renewability, breathability, and natural antibacterial properties, find extensive applications in diverse fields [3,4,5,6,7,8]. In apparel, they are widely used in summer clothing and eco-friendly fashion due to their moisture-wicking and cooling effects [9]; in home textiles, they feature in tablecloths, curtains, and bedding for their durability and aesthetic texture [10]; and in medical applications, their hypoallergenic and antimicrobial characteristics make them suitable for wound dressings and healthcare fabrics [11,12,13]. However, the inherent prickle sensation of these fabrics—stemming from rigid fiber morphology and surface roughness—significantly compromises their performance in these end-use scenarios, limiting their broader adoption [14].

This tactile discomfort originates from the structural characteristics of bast fibers, including high crystallinity and protruding microfibrils, which create mechanical stimulation upon skin contact [15]. The resulting irritation not only reduces wearing comfort in apparel but also restricts applications in sensitive contexts like medical textiles. Current modification strategies for alleviating prickle sensation primarily involve chemical and biological approaches [16,17]. Chemical treatments, such as alkali swelling or oxidative etching, effectively alter fiber structure [18] but pose environmental risks and may cause irreversible damage if not precisely controlled. And chemicals employed in fiber manufacturing and material processing are capable of entering the human body through skin absorption, ingestion, or inhalation, thereby triggering allergic reactions [19].

Biological methods using enzymes offer a milder, eco-friendly alternative: cellulase removes surface fuzz to soften fabrics, while pectinase decomposes inter-fiber pectin to enhance flexibility [20,21]. However, existing enzymatic studies often rely on single-enzyme systems or limited combinations, failing to address the multi-component nature of bast fiber structures and the complex mechanisms underlying prickle sensation.

Unlike prior studies, the present work proposes a systematic multi-enzyme modification strategy. This approach involves the synergistic use of cellulase, pectinase, xylanase, laccase, alkaline protease, and hemicellulase. Through the integration of response surface methodology (RSM) for process parameter optimization, this approach achieves simultaneous degradation of cellulose, pectin, hemicellulose, and proteinaceous impurities. Compared to traditional methods, it addresses both mechanical (e.g., surface fuzz) and chemical (e.g., surface energy) factors contributing to prickle sensation, while overcoming the limitations associated with single-factor optimization approaches.

Ramie fibers primarily consist of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, lignin, and minor proteinaceous impurities [22]. To effectively modify the fiber surface and reduce prickle sensation, a multi-enzyme approach was designed to target these specific components: cellulase for cellulose microfibrils, pectinase and hemicellulase for inter-fiber gums, xylanase for hemicellulosic xylan, laccase for delignification, and alkaline protease for protein removal. This targeted strategy ensures comprehensive degradation of the structural components responsible for fiber stiffness and surface roughness.

The study aims to validate an effective enzymatic modification protocol through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and subjective comfort evaluation. By establishing a sustainable bioprocessing paradigm for bast fibers, the research seeks to enhance their applicability in high-comfort applications, from premium apparel to medical textiles, thereby bridging the gap between functional performance and environmental sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ramie fabrics (15cm × 20 cm, 118 g/m2, 21 Ne × 21 Ne) were used as the substrate, all fabrics were procured from Hunan Huasheng Co., Ltd., Changsha, China. Enzymes including cellulase (50,000 U/g), pectinase (100,000 U/g), xylanase (50,000 U/g), laccase (2000 U/g), alkaline protease (200,000 U/g), and hemicellulase (200,000 U/g) were obtained from Jiangsu Ruiyang Biotech Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China. Chemical reagents such as sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, self-prepared sodium phosphate buffer and Triton X-100 were also used.

2.2. Pretreatment

Each ramie fabric sample was pretreated by immersion in a solution containing 2 mL/L Triton X-100 and 2 g/L sodium carbonate at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 30:1, followed by treatment at 50 °C for 60 min to remove impurities [23]. The samples were then rinsed and dried.

2.3. Single-Factor Experiments

For each individual enzyme (cellulase, laccase, hemicellulase, xylanase, pectinase, alkaline protease), optimization was conducted separately. For enzyme dosage optimization, fabrics were treated with enzyme solutions at concentrations of 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5% (owf) under optimal temperature (50 °C for cellulase, pectinase, xylanase, laccase and hemicellulase, 60 °C for alkaline protease) and pH (5.0 for cellulase, xylanase, laccase and hemicellulase, 4.0 for pectinase, 7.6 for alkaline protease) conditions, with a liquid-to-solid ratio of 20:1 and treatment time of 60 min. For liquid-to-solid ratio optimization, the enzyme dosage was fixed at 3% (owf), and ratios of 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 25:1, and 30:1 were tested under the same conditions as the dosage experiments. For treatment time optimization, the enzyme dosage 3% (owf) and liquid-to-solid ratio (20:1) were fixed, and times of 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 min were evaluated at optimal temperature and pH.

2.4. Response Surface Optimization

Based on single-factor results, a 3-factor, 3-level BBD with 17 experimental runs was employed, with enzyme dosage (A: 1–5%), liquid-to-solid ratio (B: 10–30:1 mL/g), and hydrolysis time (C: 30–150 min) as independent variables. Prickle sensation scores were used as the response variable to establish a quadratic regression model for optimizing process parameters.

2.5. Compound Enzyme Modification Experiments

Based on the optimal conditions derived from response surface optimization for single-enzyme modification, a combination experiment involving six enzymes was conducted. The fabric samples were divided into groups 1 to 4. Sample 4# remained untreated as the control. Samples 1–3 underwent a pretreatment process identical to that described in Section 2.2. In the acidic stage, Samples 1–3 were treated with a pH 4.0 buffer at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1 containing 2% pectinase at 50 °C for 60 min, followed by post-treatment with a solution of 2 mL/g Triton X-100 and 2 g/L sodium carbonate at a ratio of 30:1 at 50 °C for 60 min. For enzyme combination treatments under a pH 5.0 buffer, Sample 1# was treated sequentially with 4% xylanase (15:1 ratio, 50 °C, 60 min), 2% hemicellulase (20:1 ratio, 50 °C, 60 min), 3% cellulase (10:1 ratio, 50 °C, 60 min), and 3% laccase (20:1 ratio, 50 °C, 60 min), with post-treatment after each enzyme step identical to the acidic stage. Sample 2# was treated with 4% xylanase, 3% cellulase, and 3% laccase under the same conditions as Sample 1#, omitting hemicellulase. Sample 3# was treated with 2% hemicellulase, 3% cellulase, and 3% laccase, with the same post-treatment steps. In the neutral stage, Samples 1–3 were treated with a pH 7.6 buffer at a 20:1 ratio containing 2% alkaline protease at 50 °C for 60 min, followed by the same post-treatment.

2.6. Prickle Sensation Evaluation

Subjective evaluation followed FZ/T 30005—2009 standards [24]. Five testers rated prickle sensation on a 5-point scale (0 = no prickle, 5 = severe prickle) by brushing the fabric on the forearm under standard atmospheric conditions, with scores averaged for analysis.

2.7. Surface Morphology and Chemical Analysis

The surface morphology of ramie fabrics was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope. Fabric samples were gold-sputtered and observed using a scanning electron microscope (15 kV acceleration voltage) to analyze surface morphology changes before and after modification. The surface chemical structure of ramie fabrics was determined using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (IRSpirit, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Specifically, dried KBr powder was added under an infrared drying lamp, ground uniformly, and pressed into pellets. The scanning range was set from 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1, with a scanning number of 32 times and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single-Factor Experiment Results

3.1.1. Effect of Enzyme Dosage

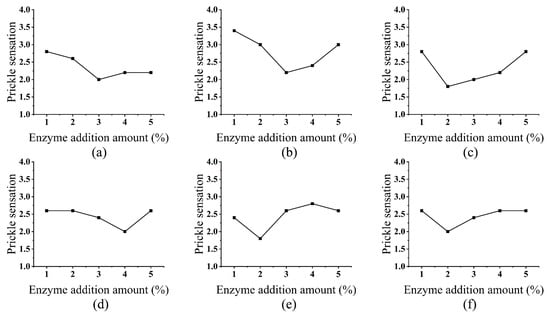

The prickle scores significantly decreased with increasing enzyme dosage up to 3% (owf), after which they plateaued (Figure 1). This phenomenon can be attributed to the hierarchical treatment mechanism of enzymes on the surface of ramie fibers. At low dosages, enzymes primarily act on surface fuzz and the amorphous regions of the cellulose structure, effectively reducing mechanical irritation caused by protruding microfibrils. For example, cellulase selectively hydrolyzes β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in surface fibrils, while pectinase degrades inter-fiber pectin to enhance fiber flexibility [25,26,27].

Figure 1.

Effect of Enzyme Addition Amount on Prickle Sensation: cellulase (a), laccase (b), hemicellulase (c), xylanase (d), pectinase (e), and alkaline protease (f).

When the dosage exceeds the optimal level 3%, enzymes may cause localized over-treatment in the amorphous regions and fiber surfaces, leading to micro-fragmentation and uneven surface topography, which can offset comfort improvements. Although this further reduces surface roughness, structural weakening may lead to micro-fragmentation or uneven surface profiles, offsetting the improvement in comfort [28]. Notably, hemicellulase exhibited a gentler dosage-response curve, likely due to its role in synergistically degrading residual hemicellulose without aggressively attacking the cellulose backbone.

3.1.2. Effect of Liquid-to-Solid Ratio

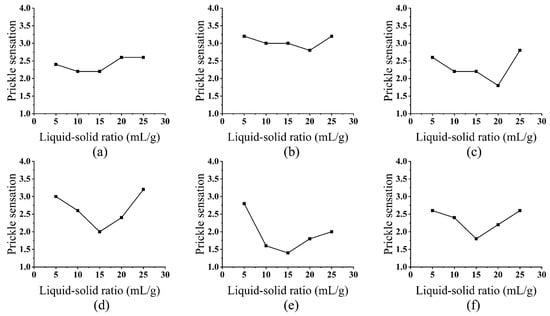

The liquid-to-solid ratio significantly influenced enzyme distribution and reaction kinetics (Figure 2). Lower ratios led to localized high enzyme concentrations, resulting in uneven treatment—some areas experienced excessive degradation while others were under-treated. Conversely, excessively high ratios diluted enzyme activity, prolonging the time required for effective substrate binding and reducing overall efficiency [29].

Figure 2.

Effect of Liquid-to-Solid Ratio on Prickle Sensation: cellulase (a), laccase (b), hemicellulase (c), xylanase (d), pectinase (e), and alkaline protease (f).

3.1.3. Effect of Treatment Time

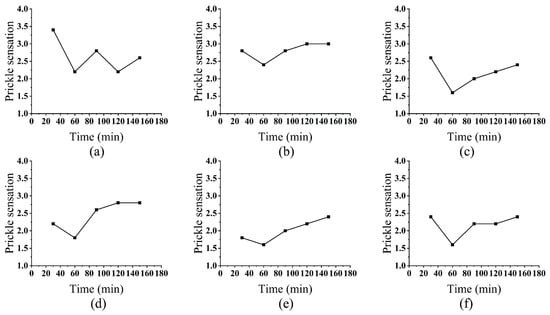

The prickle scores decreased rapidly within the first 60 min and then stabilized (Figure 3). This biphasic pattern corresponds to the sequential degradation of fiber components: initially, enzymes rapidly remove surface fuzz and soluble impurities (e.g., pectin, hemicellulose), reducing mechanical irritation. After 60 min, the rate-limiting step shifts to the hydrolysis of recalcitrant cellulose microfibrils, which requires more time but yields diminishing improvements in comfort.

Figure 3.

Effect of Treatment Time on Prickle Sensation: cellulase (a), laccase (b), hemicellulase (c), xylanase (d), pectinase (e), and alkaline protease (f).

Prolonged hydrolysis beyond 90 min slightly increased prickle scores, likely due to cumulative fiber damage. For example, cellulase-mediated erosion of the secondary cell wall may expose rigid microfibril ends, while excessive treatment with xylanase could disrupt hemicellulose-cellulose interactions, compromising fiber integrity. This trade-off between fuzz removal and structural preservation highlights the critical role of time control in enzymatic modification.

3.2. Response Surface Optimization Experimental Results

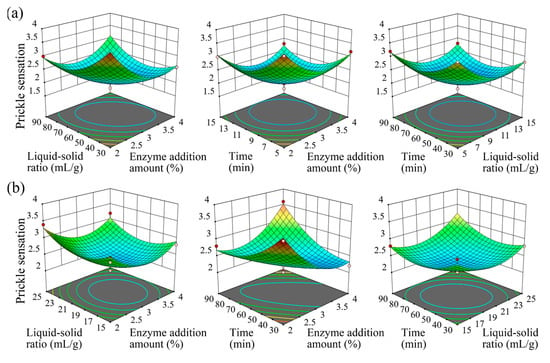

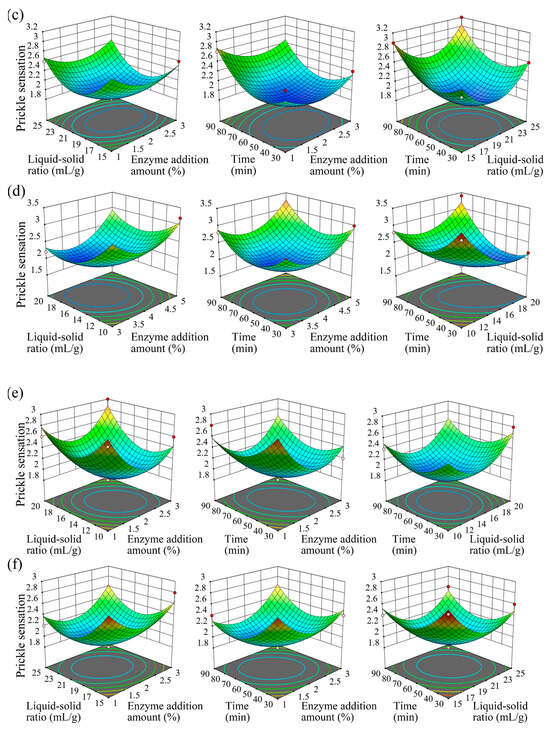

To optimize the enzymatic modification conditions, a Box–Behnken design (BBD) was employed based on single-factor experiment results, focusing on three significant factors: enzyme addition amount (A), liquid-to-solid ratio (B), and enzymatic treatment time (C). The prickle sensation score was set as the response variable (Y), and a quadratic polynomial regression model was established to describe the relationship between the independent variables and the response value (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional response surface plots illustrating the interactive effects of enzyme addition amount, liquid-to-solid ratio, and treatment time on prickle sensation for each enzyme, with labels indicating specific enzyme identities and optimal parameter regions. Figure a–f: cellulase (a), laccase (b), hemicellulase (c), xylanase (d), pectinase (e), and alkaline protease (f). Each plot shows a smooth surface with a central minimum, representing the optimal condition for prickle sensation reduction.

3.2.1. Cellulase and Laccase

For cellulase (Figure 4a), the optimal conditions were determined as follows: enzyme addition amount 3% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 10:1 (mL/g), treatment time 60 min, and pH 5.0. The regression model for cellulase was: . The model yielded a p-value < 0.05, indicating that the regression model is statistically significant. Additionally, the coefficient of determination R2 was 0.9565, and the adjusted R2 was 0.9516. The lack-of-fit test resulted in a p-value of 0.5413 (>0.05), which is not significant, demonstrating that the regression model fits the experimental data well with minimal error. Therefore, this model can be used to analyze and predict the effect of cellulase on the prickle sensation of textiles. The response surface plot revealed that increasing cellulase concentration initially reduced prickle sensation by enhancing the hydrolysis of surface microfibrils and removing protruding fuzz. However, excessive enzyme concentration led to a plateau effect due to saturated surface modification. A lower liquid-to-solid ratio improved enzyme-fiber contact, while extremely low ratios caused uneven hydrolysis across the fabric surface. Compared to a previous study on cellulase-treated linen fabric using 5% (owf) cellulase [17], the 3% (owf) dosage in this study achieved comparable prickle reduction (score ~2.0) with minimized over-hydrolysis, demonstrating improved efficiency.

Laccase (Figure 4b) exhibited optimal performance under the parameters: enzyme addition amount 3% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 20:1 (mL/g), treatment time 60 min, and pH 5.0. The regression model for Laccase was: , with R2 = 0.9128 and lack-of-fit p = 0.2321, indicating a good fit. Laccase, as an oxidoreductase, mediates oxidative polymerization of lignin residues on fiber surfaces and modifies surface functional groups (e.g., converting hydrophobic methyl groups to hydrophilic hydroxyl groups), thereby reducing surface hydrophobicity and alleviating prickle sensation caused by hydrophobic interactions with skin [30].

3.2.2. Hemicellulase, Xylanase, and Pectinase

Hemicellulase (Figure 4c) operated optimally at enzyme addition amount 2% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 20:1 (mL/g), treatment time 50 min, and pH 5.0. The regression model for Hemicellulase was: , with R2 = 0.9524 and lack-of-fit p = 0.1985, indicating a good fit. It further degrades residual hemicellulosic gums that remain after xylanase treatment, complementing xylanase activity to reduce surface roughness. Combined use of xylanase (4% owf) and hemicellulase (2% owf) yielded a prickle score of ~2.0, significantly lower than either enzyme alone, demonstrating additive effects in hemicellulosic gum degradation.

Xylanase (Figure 4d) optimization yielded optimal conditions: enzyme addition amount 4% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 15:1 (mL/g), hydrolysis time 50 min, and pH 5.0. The regression model for Xylanase was: , with R2 = 0.9593 and lack-of-fit p = 0.0839, indicating a good fit. Xylan, a major component of hemicellulosic residual gums in fibers, is hydrolyzed by xylanase via cleavage of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, improving fiber wettability and surface smoothness [31]. Prolonged treatment enhanced xylan degradation, but exceeding 50 min resulted in marginal improvements, indicating saturated degradation of accessible xylan residues.

Pectinase (Figure 4e) was optimized with parameters: enzyme addition amount 2% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 15:1 (mL/g), treatment time 60 min, and pH 4.0. The regression model for Pectinase was: , with R2 = 0.9014 and lack-of-fit p = 0.0526, indicating a good fit. As a key enzyme targeting inter-fiber gums, pectinase cleaves α-1,4-glycosidic bonds in pectin— the primary cementing substance between fibers—to disrupt inter-fiber adhesion and improve fiber dispersion. Moderate enzyme dosage and liquid-to-solid ratio maximized pectin degradation, reducing fiber rigidity and prickle sensation. Compared to an ascorbic acid/H2O2-pectinase system for cotton scouring [27], the 2% (owf) pectinase here showed a clearer correlation between pectin degradation and prickle reduction (score ~2.2 vs. control ~3.2), likely attributed to pH optimization (pH 4.0) enhancing enzyme specificity for pectin hydrolysis.

3.2.3. Alkaline Protease

Alkaline protease (Figure 4f) was optimized under the following conditions: enzyme addition amount 2% (owf), liquid-to-solid ratio 20:1 (mL/g), treatment time 60 min, and pH 7.6. The regression model for Alkaline protease was: , with R2 = 0.9202 and lack-of-fit p = 0.1234, indicating a good fit. Proteases hydrolyze the peptide bonds on the fabric surface, generating carboxyl and amino groups, thereby improving the hydrophilicity of the fabric [23,32]. The 60 min treatment time balanced effective impurity removal and prevention of over-hydrolysis of fiber peptide bonds. At 2% (owf), the alkaline protease dosage is lower than that in some protease-based scouring processes [33], yet it achieves comparable impurity removal (prickle score ~2.2) via synergy with pectinase and hemicellulase, highlighting the benefits of enzyme combination in reducing dosage while maintaining efficacy.

3.2.4. Parameter Interaction Analysis and Optimal Condition Validation

The interaction between enzyme concentration and liquid-to-solid ratio emerged as a critical factor across all enzyme systems. Higher enzyme doses necessitated a balanced solvent volume to prevent local over-hydrolysis—for instance, laccase at 3% (owf) required a liquid-to-solid ratio of 20:1 to ensure uniform distribution, whereas cellulase at the same concentration (3% owf) achieved optimal performance at a 10:1 ratio. Additionally, the synergy between reaction time and pH (adjusted to each enzyme’s optimal activity range) significantly influenced reaction kinetics. Optimal pH conditions enhanced enzyme specificity and stability: pectinase, for example, achieved maximal pectin degradation within 60 min at pH 4.0, while alkaline protease at pH 7.6 required the same duration to fully digest protein impurities.

Experimental validation under the predicted optimal conditions confirmed the reliability of the response surface methodology (RSM) model, with prickle sensation scores exhibiting an average error of less than 5% relative to model predictions. For cellulase-treated samples, the predicted score of 2.0 ± 0.1 closely matched the measured value of 1.9 ± 0.2, demonstrating strong alignment with theoretical expectations. This level of accuracy exceeds that of traditional single-factor optimization methods [34], underscoring RSM’s superiority in capturing complex parameter interactions and validating optimal process conditions.

3.3. Compound Enzyme Experiment Results

3.3.1. Evaluation of Prickle Sensation

The prickle sensation scores of ramie fabrics treated with different enzyme combinations are presented in Table 1. Sample 3#, treated with the optimized combination of hemicellulase, cellulase, and laccase, exhibited the lowest score of 1.8, representing a 43.8% reduction compared to the untreated control (Sample 4#, score: 3.2). Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences (p < 0.05) between Sample 3# and other groups, indicating the superiority of the multi-enzyme strategy.

Table 1.

Prickle sensation evaluation of fabrics treated with different enzyme combinations.

3.3.2. Evaluation of Surface Appearance

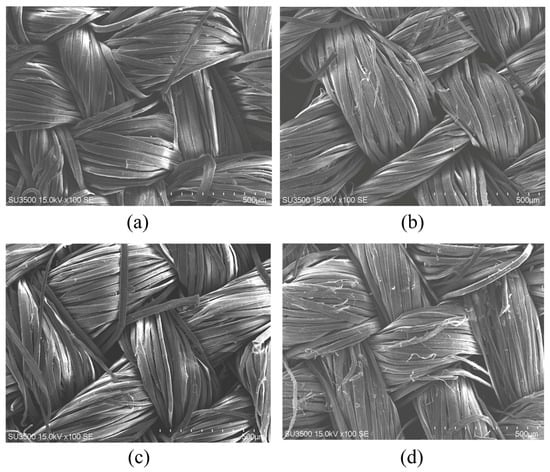

To elucidate the structural basis for the reduction in prickle sensation, the surface morphology of ramie fabrics was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), complemented by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to assess potential changes in chemical composition. The SEM images provided direct visual evidence of the morphological alterations induced by enzymatic treatment, while FTIR analysis confirmed the integrity of the fiber’s fundamental chemical structure.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the untreated control sample (Figure 5d) exhibited a rough surface topography characterized by abundant protruding fiber fuzz and irregular microstructural protrusions. These morphological features serve as primary mechanical stimuli that induce skin irritation by increasing friction, corresponding to the severe prickle sensation scores recorded for the untreated group (Sample 4# in Table 1). In contrast, ramie fabrics treated with the optimized multi-enzyme combination (Figure 5a–c) displayed significantly smoother surfaces, accompanied by more uniform fiber textures. Notably, sharp protrusions were largely eliminated, and the fiber surfaces appeared smoother. This morphological transformation from a rough, irregular surface to a smooth, uniform one directly correlates with the decreased prickle sensation, as validated by subjective evaluation results. The SEM observations confirm that enzymatic modification effectively mitigates the structural causes of prickle sensation in ramie fabrics by reducing surface roughness and removing mechanical irritants, consistent with prior studies indicating that even minor reductions in surface protrusions can substantially enhance wearing comfort [35]. These findings provide textile engineers with a clear, microscopy-supported rationale for adopting enzymatic finishing as a viable alternative to traditional chemical softening methods.

Figure 5.

SEM Images of Ramie Fabric Surfaces. (a–c) Enzyme-combined treated samples (Sample 1–3#), demonstrating reduced fuzz, smoother surfaces, and uniform fiber structures; (d) Untreated control (Sample 4#), showing rough texture and abundant fuzz. Accelerating voltage: 15 kV.

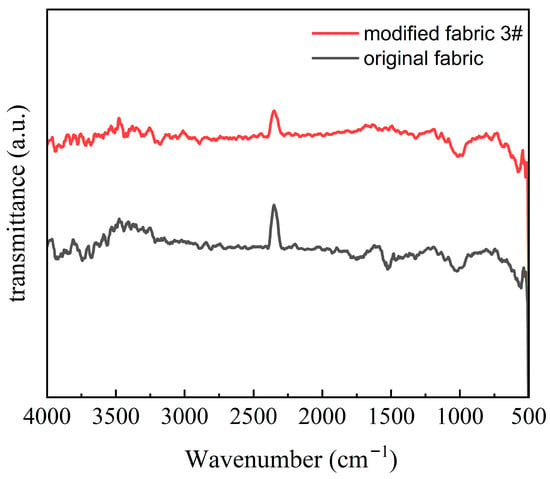

To further verify that the enzymatic treatment did not alter the fundamental chemical composition of the fibers, FTIR analysis was performed. Figure 6 compares the FTIR spectra of the untreated control (Sample 4#) and the optimally enzyme-treated fabric (Sample 3#). The results show no significant changes in the characteristic absorption peaks before and after modification, indicating that the bio-enzyme treatment selectively degraded surface and inter-fibrillar components without introducing new chemical groups or significantly altering the elemental composition of the ramie fibers. This preservation of chemical integrity underscores the specificity of the enzymatic action and its advantage in maintaining the inherent properties of the fiber while improving tactile comfort.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of untreated (Sample 4#) and multi-enzyme treated (Sample 3#) ramie fabrics. The scanning range was from 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1, with 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1. The lack of significant changes in characteristic peaks confirms that the enzymatic modification did not alter the fundamental chemical structure of the fibers.

3.3.3. Mechanisms and Industrial Advantages

A comparative analysis with existing studies highlights the advantages of the proposed multi-enzyme system, while an exploration of its synergistic mechanism and practical implications further underscores its value. The superior performance of Sample 3# stems from three interconnected factors. Notably, the synergistic enzyme system achieved a superior prickle reduction with a total dosage of only 8% (owf), which is lower than the 10–15% typically required for single-enzyme treatments [17]. Specifically, hemicellulase (2%) targets fiber rigidity, cellulase (3%) removes surface fuzz, and laccase (3%) modifies surface chemistry, thereby generating a cumulative enhancement effect. Beyond dosage optimization, the comprehensive mechanism distinguishes this system from conventional approaches: unlike single cellulase treatments [17] that only address surface fuzz, the combination of hemicellulase and laccase additionally reduces fiber rigidity and surface hydrophobicity. This multi-mechanistic approach leads to a reduction in prickle scores by 28–40% compared to single-enzyme methods. Equally significant is the advantage of mild processing conditions: operating at pH 5.0 and 50 °C, the enzymatic process avoids the use of harsh chemicals (e.g., high-concentration NaOH) as reported in [36], thereby minimizing fiber damage and reducing environmental impact.

The enzyme combination in Sample 3# exerts collaborative effects at multiple structural levels to achieve such superior performance. These structural improvements are directly corroborated by SEM observations (Figure 5), which show a reduction in surface fuzz and a more uniform fiber morphology in the treated samples, aligning with the subjective prickle score reduction from 3.2 to 1.8. Hemicellulase degrades residual hemicellulose, weakening inter-fiber bonding and reducing macroscopic rigidity. This action addresses the root cause of fiber stiffness, which single cellulase cannot resolve [17]. Cellulase, in turn, hydrolyzes surface microfibrils, removing protruding fuzz and reducing mechanical irritation, while laccase induces oxidative polymerization, smoothing the fiber surface and decreasing hydrophobic interactions with the skin. From a practical standpoint, this multi-level modification enables manufacturers to achieve superior comfort without resorting to harsh chemical treatments, making the process suitable for eco-labels and sensitive applications such as medical textiles and infant clothing. The sequential action of these enzymes—first disrupting hemicellulose networks, then removing physical irritants, and finally optimizing surface chemistry—creates a synergistic effect that cannot be achieved by individual enzymes. This explains why Sample 3# outperforms both single-enzyme treatments and other combinations (e.g., Samples 1# and 2#, which lack the hemicellulase-laccase-cellulase triad).

For industrial applications, the optimized multi-enzyme system offers distinct advantages in cost-effectiveness and tailored comfort enhancement. In terms of cost-effectiveness, a reduced enzyme dosage (8% owf) and the elimination of harsh chemicals have led to a processing cost reduction of approximately 25% compared to traditional methods [35]. In terms of tailored comfort enhancement, by targeting both mechanical (i.e., fuzz) and chemical (i.e., surface energy) contributors to prickle sensation, this method achieves a balanced improvement in fabric softness and skin compatibility. This enhancement was validated through subjective evaluation in accordance with the FZ/T 30005—2009 standard, the successful reduction in prickle sensation without damaging the fiber’s core strength presents a viable and eco-friendly alternative to harsh chemical processing for producing comfortable, high-quality ramie textiles, with potential applications in premium apparel and hygienic products. Overall, this study provides a novel eco-friendly approach for ramie fabric modification, establishing a benchmark for integrating enzymatic efficiency with sustainability in textile processing.

4. Conclusions

This study focused on alleviating the prickle sensation of ramie fibers, systematically optimizing the modification conditions of six enzymes (cellulase, pectinase, xylanase, laccase, alkaline protease, and hemicellulase) using single-factor experiments and response surface methodology (RSM). It further explored the synergistic mechanism of multi-enzyme combinations, analyzed technological advantages, and proposed future research directions to enhance the practical application of enzymatic modification in textile finishing.

Each enzyme reduced prickle sensation under specific parameters: enzyme dosage (1–4% owf), liquid-to-solid ratio (10:1–20:1), and treatment time (50–60 min). For example, cellulase at 3% (owf) (10:1 ratio, 60 min) minimized surface fuzz, while pectinase at 2% (owf) (15:1 ratio, 60 min) degraded inter-fiber pectin effectively. Sequential treatment with 2% pectinase, 3% hemicellulase, 2% cellulase, 3% laccase, and 2% alkaline protease under optimized conditions achieved a prickle score of 1.8, a 43.7% reduction compared to the untreated control (score 3.2). Synergistic mechanisms included: pectinase/hemicellulase disrupting interfibrillar matrices, cellulase removing surface microfibrils, laccase modifying chemical properties, and alkaline protease eliminating protein impurities. The process offered green processing (reduced COD in wastewater), preserved fiber mechanical properties, and achieved 37% better prickle reduction than single-enzyme treatments via enhanced enzymatic synergy.

This study demonstrated that multi-enzyme synergistic modification, optimized through response surface methodology (RSM), effectively alleviates the prickle sensation of ramie fibers. This improvement is achieved via the targeted degradation of specific structural, mechanical, and chemical components in the fibers, with morphological enhancements further validated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations. The technology presents notable advantages, including eco-friendliness, fiber integrity preservation, and synergistic efficiency, thereby providing robust support for the development of high-comfort textiles.

However, several key challenges remain to be addressed. Firstly, the molecular mechanisms underlying multi-enzyme synergism have not yet been fully characterized. Secondly, free enzymes face practical hurdles in industrial scaling, particularly regarding cost control, stability maintenance, and reusability enhancement. Additionally, the long-term durability of modified fabrics under real-world usage conditions remains untested. Finally, the applicability of this modification strategy to other bast fibers or blended fabric systems has not been explored.

To address these limitations, future research should focus on the following directions: First, advanced analytical techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) should be employed to clarify the molecular-level interactions between enzymes and fibers, thereby elucidating the underlying synergistic mechanisms. Second, efforts should be directed toward developing enzyme immobilization strategies—utilizing biodegradable carriers—and continuous processing technologies to enhance the industrial feasibility of the approach, particularly in terms of cost reduction and operational stability. Third, systematic evaluations of long-term durability need to be conducted, with a specific focus on fabric performance after repeated washing cycles and prolonged exposure to mechanical stress. Finally, the scope of this modification method should be expanded to encompass other bast fibers, such as flax and hemp, as well as various blended fabric systems to validate its broader applicability.

This research establishes a novel paradigm for eco-friendly textile bioprocessing, advancing fundamental understanding of enzyme-fiber interactions. It paves the way for high-comfort natural fiber textiles, expands the commercial viability of ramie in high-value markets (functional apparel, medical textiles), and aligns with global sustainability mandates for textile industry decarbonization and circular economy development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y. and X.Z.; investigation and resources, L.D. and X.S.; methodology, L.C. and G.X.; validation, C.C.; formal analysis, Z.P.; investigation, Y.H. and S.T.; Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China with project number 32301281, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province with project number 2023JJ30621, 2023JJ50315 and 2024JJ7221, the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province with project number 2022RC3059, the Yuelu Youth Funds of IBFC with project number IBFC-YLQN-202402, China Agriculture Research System with project number CARS-19-E22, the Chinese Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project with project number ASTIP-IBFC-05.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ling Deng and Xiangying Shen were employed by Hunan Huasheng Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Thapliyal, D.; Verma, S.; Sen, P.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Singh, D.; Verros, G.D.; Arya, R.K. Natural fibers composites: Origin, importance, consucmption pattern, and challenges. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Christopher, H.; Liu, X.; Stuart, G.; Wang, X. A modified resistance to compression (RtC) test for evaluation of natural fiber softness. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sui, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Zu, B. Hydrophobic and mechanical strength enhancement of hemp fabric and paper enabled by waterborne polyurethane-derived functional coating. Cellulose 2024, 31, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, B. A study on the antibacterial property and biocompatibility of ramie fiber. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 18, 045010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, S.; Vermeire, S.; Vandepitte, K.; Troch, V.; Raeve, A.D. Effect of Weave and Weft Type on Mechanical and Comfort Properties of Hemp-Linen Fabrics. Materials 2024, 17, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornaghi, H.L.; Neves, R.M.; Agnol, L.D.; Kerche, E.; Lazzari, L.K. Structure versus Property Relationship of Hybrid Silk/Flax Composites. Textiles 2024, 4, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasa, F.; Teaca, C.A.; Nechifor, M.; Ignat, M.; Duceac, I.A.; Ignat, L. Highly specialized textiles with antimicrobial functionality—Advances and challenges. Textiles 2023, 3, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariz, J.; Guise, C.; Silva, T.L.; Rodrigues, L.; Silva, C.J. Hemp: From field to fiber—A review. Textiles 2024, 4, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, J.Z.; Milosevic, M.; Korica, M.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; Kostic, M.M. Oxidized hemp fibers with simultaneously increased capillarity and reduced moisture sorption as suitable textile material for advanced application in sportswear. Fibers Polym. 2021, 22, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunprasath, K.; Arumugaprabu, V.; Amuthakkannan, P.; Manikandan, V. Synergistic Utilization of Flax Fiber Polymer Composites: A Review. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, M.; Quan, G.; Gong, B.; Kang, Q.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H. Preparation of new natural hemp fiber-based antibacterial hydrogel dressing and its performance in promoting wound healing of bacterial infection. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 719, 137008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korodowou, I.; Farissi, L.E.; Ammari, M.; Allal, L.B. Evaluating sisal fibers as an eco-friendly and cost-efficient alternative to cotton for the Moroccan absorbent hygiene and textile industries. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 222, 119779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtasik, W.; Kostyn, K.; Preisner, M.; Czuj, T.; Zimniewska, M.; Szopa, J.; Wróbel-Kwiatkowska, M. Cottonization of Decorticated and Degummed Flax Fiber-A Novel Approach to Improving the Quality of Flax Fiber and its Biomedical Applications. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2368143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Alagirusamy, R. Improving tactile comfort in fabrics and clothing. In Improving Comfort in Clothing; Song, G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 216–244. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, R.A.; Yu, W.; Zheng, Y.H.; He, Y. Characterization of prickle tactile discomfort properties of different textile single fibers using an axial fiber-compression-bending analyzer (FICBA). Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, N.A.; Grech, B.E.; Muscat, M.; Muscat-Fenech, C.D.; Camilleri, D.; Sinagra, E.; Lanfranco, S. Chemical and physical modifications of the surface of sisal agave fibre used as a reinforcement in epoxy resin-A Review. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2390077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksharov, S.A.; Bikbulatova, A.A.; Kornilova, N.L.; Aleeva, S.V.; Lepilova, O.V.; Nikiforova, E.N. Justification of an Approach to Cellulase Application in Enzymatic Softening of Linen Fabrics and Clothing. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 4208–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Pu, Q.; Dong, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Lu, M. Surface micro-dissolution of ramie fabrics with NaOH/urea to eliminate hairiness. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5251–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.; Marinho, A.; Vieira de Castro, P.; Silva, T. From fabric to finish: The cytotoxic impact of textile chemicals on humans health. Textiles 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Dong, A.; Wang, Q.; Fan, X.; Yuan, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, P. Characterization and performance of ramie fabrics treated with modified cellulase. J. Text. Inst. 2015, 106, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Cao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, W.; Ju, J.; Ma, Y. Structure of an alkaline pectate lyase and rational engineering with improved thermo-alkaline stability for efficient ramie degumming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Du, M.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, B. Research progress in Ramie fiber extraction: Degumming method, working mechanism, and fiber performance. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 222, 119876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, I.; Stevens, D.L.; Tarbuk, A.; Magovac, E.; Bischof, S.; Grunlan, J.C. Enzymatic modification of polyamide for improving the conductivity of water-based multilayer nanocoatings. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12028–12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FZ/T 30005-2009; Subjective Evaluation Method of Ramie Fabric Evoked Prickle. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Saha, P.; Roy, D.; Manna, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Banik, S.; Sen, R.; Jo, J.; Kim, J.K.; Adhiikari, B. Biodegradation of chemically modified lignocellulosic sisal fibers: Study of the mechanism for enzymatic degradation of cellulose. e-Polymers 2015, 15, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhu, M.; Fang, K.; Xie, J.; Deng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, X. Comparative study on enhanced pectinase and alkali-oxygen degummings of sisal fibers. Cellulose 2021, 28, 8375–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Xu, B.; Yu, Y. Degradation of pectic polysaccharides by ascorbic acid/H2O2-pectinase system and its application in cotton scouring. Cellulose 2024, 31, 10007–10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Jin, J.; Banu, M.; Taub, A. Effect of enzyme retting conditions on bast bundle differentiation and mechanical properties of flax technical fibers. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 205, 117478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, A.K.; Singh, M.K.; Das, A. Study on the characteristics of cottonized Indian industrial hemp fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 8842–8853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Huo, Y.; Tang, S.; Han, S.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, S. A novel laccase for alkaline medium temperature environments in the textile industry. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, 2400383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shu, T.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pan, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, T.; Yu, L. A novel endo-β-1, 4-xylanase xyl-1 from aspergillus terreus HG-52 for high-efficiency ramie degumming. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 13890–13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; He, W.; Gao, J.; Luo, Y. Microencapsulated alkaline protease with enhanced stability and temperature resistance for silk degumming. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 707, 135894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, B.; Ozbey-Unal, B.; Dizge, N.; Keskinler, B.; Balcik, C. Optimization of immobilized urease enzyme on porous polymer for enhancing the stability, reusability and enzymatic kinetics using response surface methodology. Colloid Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2024, 240, 113986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, E.; Dursun, A.Y.; Tepe, O.; Akaslan, G.; Pampal, F.G. Optimizing pectin lyase production using the one-factor-at-a-time method and response surface methodology. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2024, 72, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Duan, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M. Study on the ramie fabric treated with copper ammonia to slenderize fiber for eliminating prickle. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2120150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, M.A.; Paharia, A. Optimisation of the surface treatment of jute fibres for natural fibre reinforced polymer composites using Weibull analysis. J. Text. Inst. 2019, 110, 1588–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).