Abstract

Polylactic acid (PLA) films were directly fluorinated using fluorine gas at room temperature under varying conditions: fluorine concentrations of 190–760 Torr and reaction times of 10–60 min. Some of the fluorinated samples were subsequently dried at 70 °C for 2 d. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses verified the successful introduction of fluorine and the formation of -CFx and C=OF groups on the PLA surface after fluorination. The fluorination level initially increased with increasing reaction time or fluorine concentration but then decreased because of the formation and escape of CF4 gasification. Drying further reduced the surface fluorine content. Both fluorination and drying increased the glass transition temperature of PLA, which was attributed to the increase in surface polarity and crosslinking density of the polymer. Fluorination significantly improved the surface hydrophilicity of PLA, with the water contact angle decreasing from 64.09°to 18.75°. This was due to the formation of a rough, porous surface caused by the introduction of polar fluorine atoms, as observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). However, drying the fluorinated samples increased the water contact angle to 91.46°, resulting in hydrophobicity owing to increased surface crosslinking. This study demonstrates a simple and effective method for tuning the hydrophilic–hydrophobic properties of PLA surfaces using direct fluorination and thermal treatment.

1. Introduction

Polylactic acid (PLA), a linear aliphatic polyester, exhibits several attractive properties. It is a new type of biodegradable material [1,2,3]. PLA has many advantages, such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, easy processing, excellent thermal stability, and excellent mechanical properties [4,5]. Owing to these advantages, PLA is widely used in biomedicine, furniture and textiles, packaging, composite materials, plastic films, and 3D printing [6,7,8]. Furthermore, in the current coating field, coating enhancement can be achieved through functional fillers, surface treatments, and interface engineering [9]. PLA, with its excellent physical properties, unique chemical properties, and biocompatibility, has potential applications in coatings.

However, owing to the molecular structure of PLA, its surface properties (hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity) are not obvious, limiting its application range [10]. Currently, many methods for PLA surface modification have been reported, such as chemical modification [11,12], plasma treatment [13,14,15], photografting [16,17], fused deposition modeling [18,19], and ultraviolet treatment [20].

Traditional modification methods can alter the internal structure of PLA. Some surface changes may not be permanent and can degrade over time or with use. Moreover, surface modification requires additional equipment, which increases production costs and the complexity of the process. Compared to previous methods, the introduction of fluorine can accurately modify the PLA surface. This not only ensures the integrity of the material but also provides excellent surface properties of the coating. The introduction of low-polarity fluorine atoms plays an important role in the hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the PLA surface. Akhilesh et al. reduced the polar and dispersion components of the total surface energy by inlaying perfluoropolyether of different lengths on a PLA surface. In addition, embedding low-surface-energy segments significantly changes the surface morphology and properties, resulting in significant hydrophobicity and lipophobicity [21]. Razieh et al. prepared a hydrophobic fluorinated PLA that was non-toxic to cells by modifying the PLA monomer to introduce -CF3. Compared to PLA, fluorinated PLA adsorbed and retained higher amounts of albumin and fibrinogen, exhibiting better blood compatibility. This makes it an ideal material for novel cardiovascular devices [22]. Nadine et al. treated PLA surfaces with different hydrophobic plasmas (CF4, CF4/H2, CF4/C2H2, and tetramethylsilane) to improve their water and oxygen barrier properties. The results showed that the treated PLA exhibited high barrier properties against both water and oxygen. Thermodynamic tests indicated that the internal PLA remained unchanged, demonstrating precise control over surface modification [23]. C. Chaiwong et al. modified the surface of PLA using SF6 plasma. The results showed that the treated surface exhibited hydrophobicity owing to the coordination of fluorine atoms in the PLA structure, whereas the water barrier properties were not improved. Furthermore, thermodynamic tests indicated that the plasma treatment only occurred on the surface and had no effect on the internal structure [24].

Compared to the use of fluorine reagents or fluorine-containing plasma, direct modification of surfaces with fluorine gas is a research hotspot. Michaela et al. functionalized PLA surfaces using gas-phase fluorination and investigated the correlation between the surface properties and physiology. The results showed that gas-phase fluorination led to the formation of C-F bonds in the PLA backbone, thereby shifting the surface towards a more hydrophilic and polar orientation. The slightly negatively charged surface energy improved cell adhesion and spreading on PLA [25]. However, the fluorination modification of PLA has not completely solved its hydrophobicity problem. The hydrophobicity of most PLA surfaces relies on high-energy plasma to disrupt their surfaces. This process is complex and cumbersome, and the excellent properties of PLA, such as biocompatibility, are significantly compromised, making it counterproductive. Although direct fluorination with fluorine gas can maintain its original properties, simple fluorination increases surface hydrophilicity. Kim et al. [25] tried to control the hydrophilic–hydrophobic transition of PET films using surface fluorination and drying. The surface properties of PET can be effectively controlled and are dependent on the fluoride surface. However, the properties of the fluoride formed under various conditions have not been discussed sufficiently.

This study attempted to modify the PLA surface using F2 and investigated the physicochemical properties and morphology of the PLA surface under different reaction times at the same F2 concentration, as well as at different F2 concentrations at the same reaction time. Furthermore, some fluorinated samples were dried to explore the effect of temperature on the fluorinated layers. Hydrophobic surfaces were obtained using a simple treatment method. In particular, we investigated the properties of various fluorides on the PLA surface and confirmed their effects on the surface properties of PLA in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PLA Films

PLA particles (purchased from Standard Test Piece Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan) were used in this study. A sample weighing 1.00 g and 33.00 g of dichloromethane solution were mixed in a beaker. The mixture was then stirred well to prepare a PLA solution. The PLA solution was poured into a round polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mold and placed in a ventilated area for 2 h to allow it to dry. PLA films were obtained by evaporating the solution.

2.2. Surface Fluorination of PLA

PLA films (10 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm) were washed with ethanol to remove organic residues from the surface. Fluorine gas (99.5%) was purchased from Daikin Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Before fluorination, the PLA films were placed in a Ni reactor (24 × 32 × 5 mm3) at 25 °C under vacuum (0.1 Pa) for 10 h to eliminate impurities from the system. The vacuum reactor was then filled with fluorine gas. The fluorination apparatus has been described in a previous study [26]. The surface fluorination of PLA samples was carried out at 25 °C, 190–760 Torr of F2 pressure, and 10–60 min of reaction time. The prepared samples were named as FPLA380torr-10min, FPLA380torr-15min, FPLA380torr-30min, FPLA380torr-60min, FPLA190torr-15min, FPLA760torr-15min at this study.

2.3. Drying of Fluorinated PET

To confirm the drying effect, some fluorinated samples were placed in a vacuum for 48 h at 70 °C. The samples were named as FPLA380torr-10min-dry, FPLA380torr-15min-dry, FPLA380torr-30min-dry, FPLA380torr-60min-dry, FPLA190torr-15min-dry and FPLA760torr-15min-dry at this study.

2.4. Material Characterization

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) absorption spectroscopy (Nicolet 6700; Thermo Electron Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to identify the chemical compositions of the PLA samples. The analysis was conducted in Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) mode at 500–4000 cm−1, from which 32 scans were acquired and air background removal was performed. The surface states of the PLA samples were determined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; JPS-9010, JEOL, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All binding energies were referenced to a carbon peak at 284.8 eV. To determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the samples, DSC tests were conducted using a thermal analyzer (DSC6200; Seiko Instruments Inc., Chiba, Japan). The samples (15 mg) were initially heated from 30 to 200 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C·min−1 under an Ar atmosphere. The changes in surface roughness before and after surface modification were evaluated using atomic force microscopy (AFM; Nanoscope IIIa, Digital Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). The scanning was conducted in tapping mode within an area of 10 µm × 10 µm. Each sample was tested three times from the surface. The arithmetic mean surface roughness was determined from an AFM roughness profile. The static water contact angle (WCA) of untreated and modified PLA was measured at 25 °C using the sessile drop method. A 10 μL water droplet was used in a telescopic goniometer with a magnification power of 23× and a protractor with a graduation of 1° (Krüss G10, Hamburg, Germany). Three measurements were acquired at different surface locations on each sample to determine the average value (±2°). To observe the effects of fluorination and drying treatments on the surface and cross-sections of all samples, SEM (SEM, HitachiS-4800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used. All samples were coated with osmium. Surface observations were performed in high-vacuum mode at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. Cross-sectional observations were performed in high-vacuum mode at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Fluorination and Drying on the Surface Composition and Structure

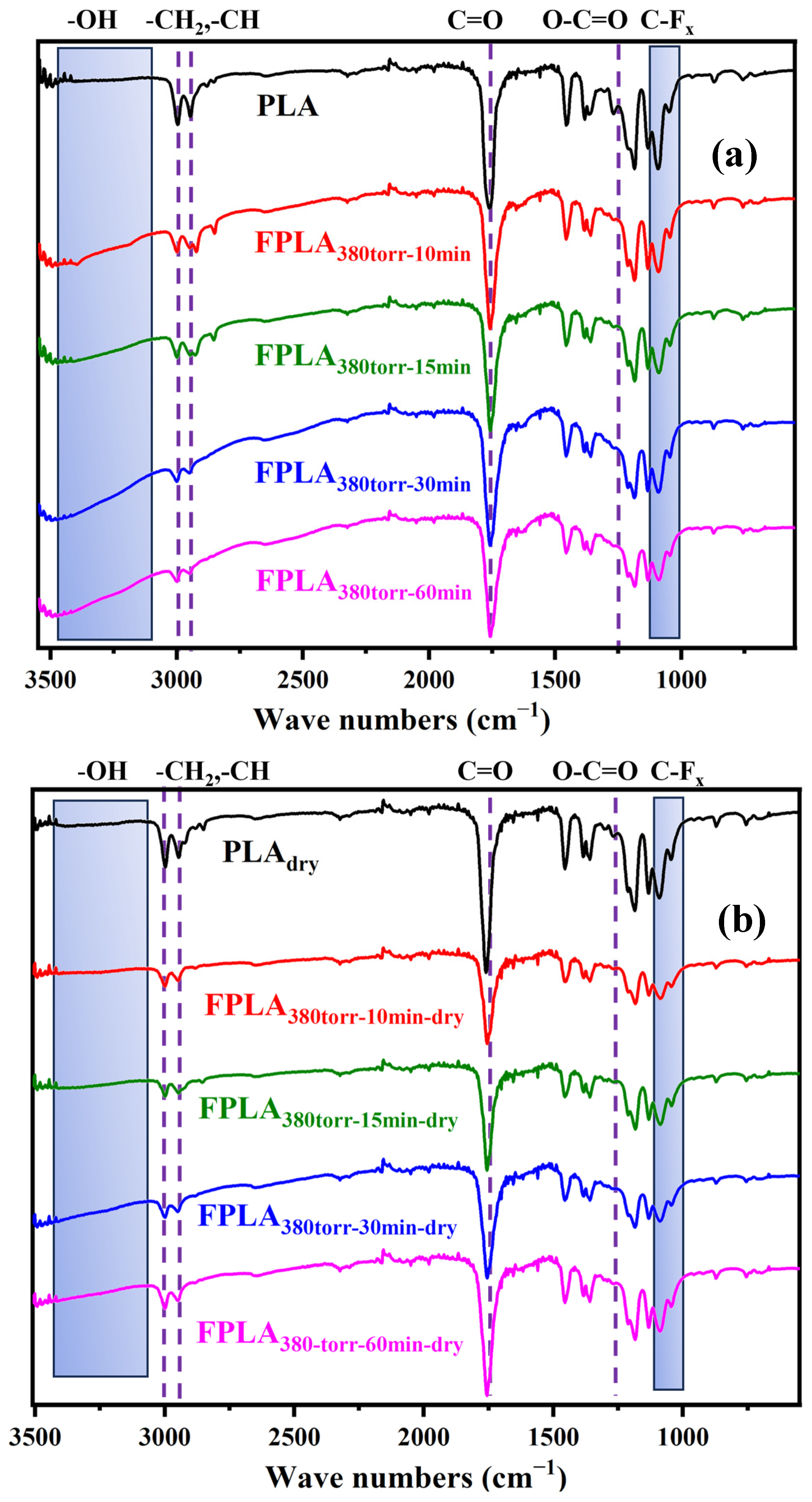

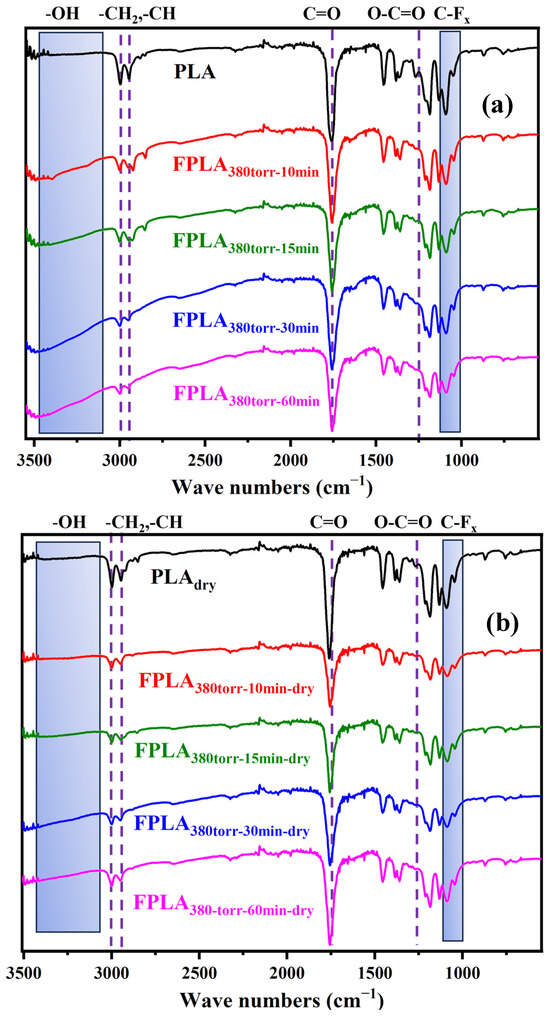

Figure 1 shows the FT-IR spectra of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times. The peaks of -CH2- at 2928 cm−1 and -CH- at 2853 cm−1 in the spectra of the fluorinated and dried samples were both weakened [27,28]. In addition, after fluorination, a very obvious -OH peak appears in 3500–3200 cm−1 and the intensity increased with the increase in fluorination time. After drying, the temperature increased, causing -OH to turn into H2O and leave the surface. The peak intensity decreased. For PLA, the peak at 1770 cm−1 is attributed to C=O and the peak at 1260 cm−1 is attributed to the ester group O-C=O [29,30]. After fluorination, the O-C=O peak intensity decreased, but the C=O peak, which shifted to 1750 cm−1, did not change significantly. This may be because fluorination leads to the cleavage of O-C=O and the formation of -COF. -COF is easily converted to COOH via hydrolysis. As a result, the O-C=O peak intensity decreased, and the C=O peak shifted to a lower wavelength. During drying, parts of -COOH will be decarboxylated or regenerated into O-C=O. Therefore, the peak intensity of C=O decreased overall, whereas the intensity of the O-C=O peak increased slightly [27,31]. The C-Fx stretching vibration peak appears at 1000–1210 cm−1 [26,32]. This indicates that the PLA was partially fluorinated. As the fluorination time increased, the intensities of the -CH- and -CH2- peaks decreased. However, the C-Fx peak first increased and then decreased. This is because fluorine radicals continuously attack the carbon chain, generating CF4 that escapes from the surface. Therefore, the C-Fx intensity did not continue to increase. After drying, the peak intensity of C-Fx continued to decrease. This may be due to the thermal effect, which causes C-F and C-F2 to continue converting into CF4 and escaping on the surface. Consequently, the peak intensity of C-Fx decreased further. For the dried samples (b), the peak intensities did not change significantly, indicating that heat treatment of the surface after fluorination did not alter the surface functional groups. However, the intensities of all peaks decreased after drying. This is likely due to the thermal effect, which causes some fluorine atoms on the surface to continue reacting and generating CF4, resulting in a further decrease in the peak intensity.

Figure 1.

FT-IR images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times.

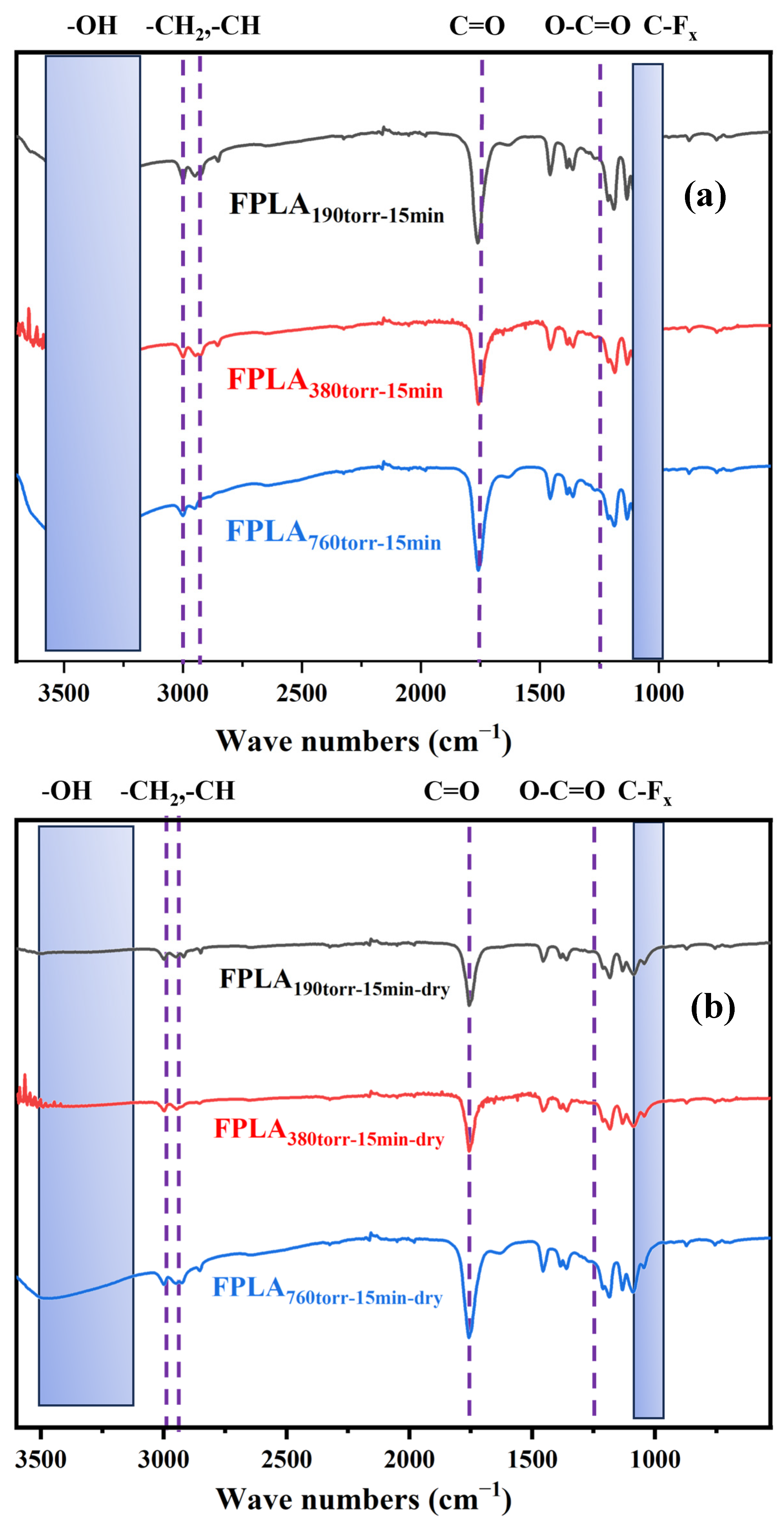

Figure 2 shows the FT-IR spectra of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different F2 contents. For the fluorinated samples, the peak intensities of -CH- and -CH2- decreased. The -OH peak appeared and increased in intensity with increasing F2 content. The O-C=O peak intensity decreases, while the C=O peak shifts to lower wavenumbers due to the formation of -COF and conversion to -COOH. The C-Fx peak appeared, and owing to the generation of CF4, the peak intensity first increased and then decreased. During drying, similar to Figure 1b, the thermal effect causes some of the C-F to continue to convert into CF4 and overflow from the surface, as well as COOH decarboxylates or re-crosslinks. Consequently, the intensities of the -OH, -CH-, -CH2-, C=O, and C-Fx peaks decreased, and the O-C=O peak intensity slightly increased.

Figure 2.

FT-IR images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different F2 contents.

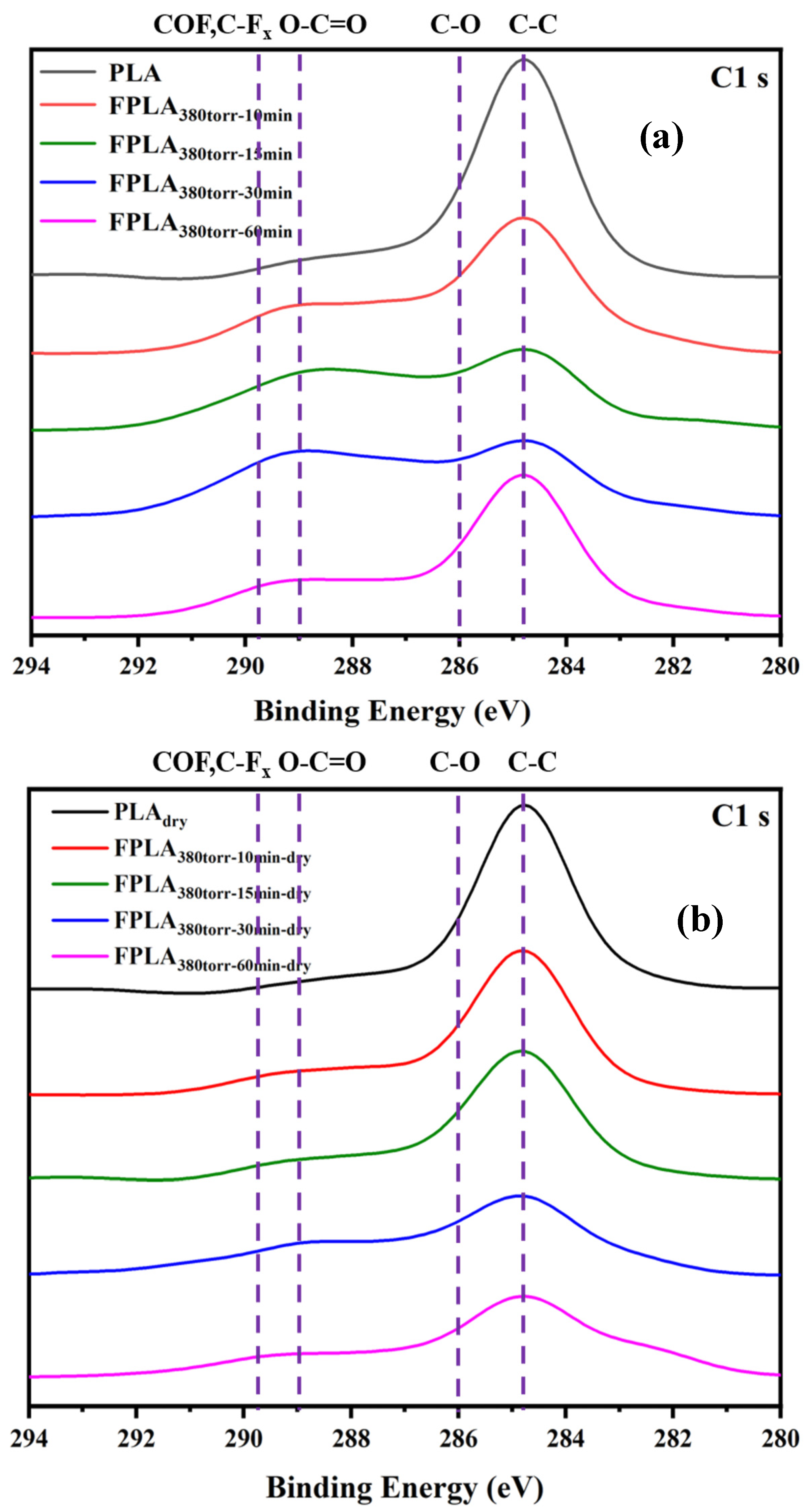

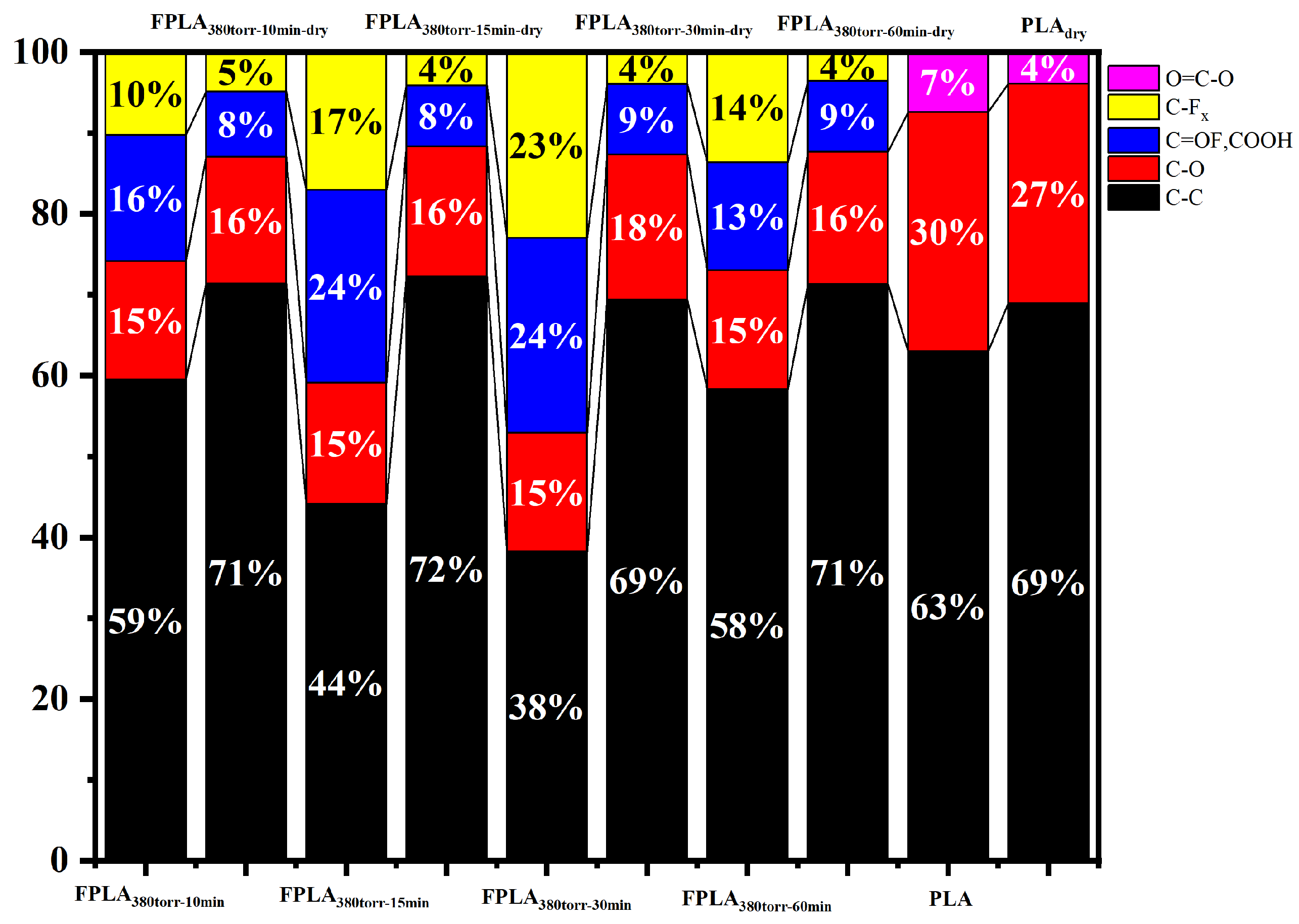

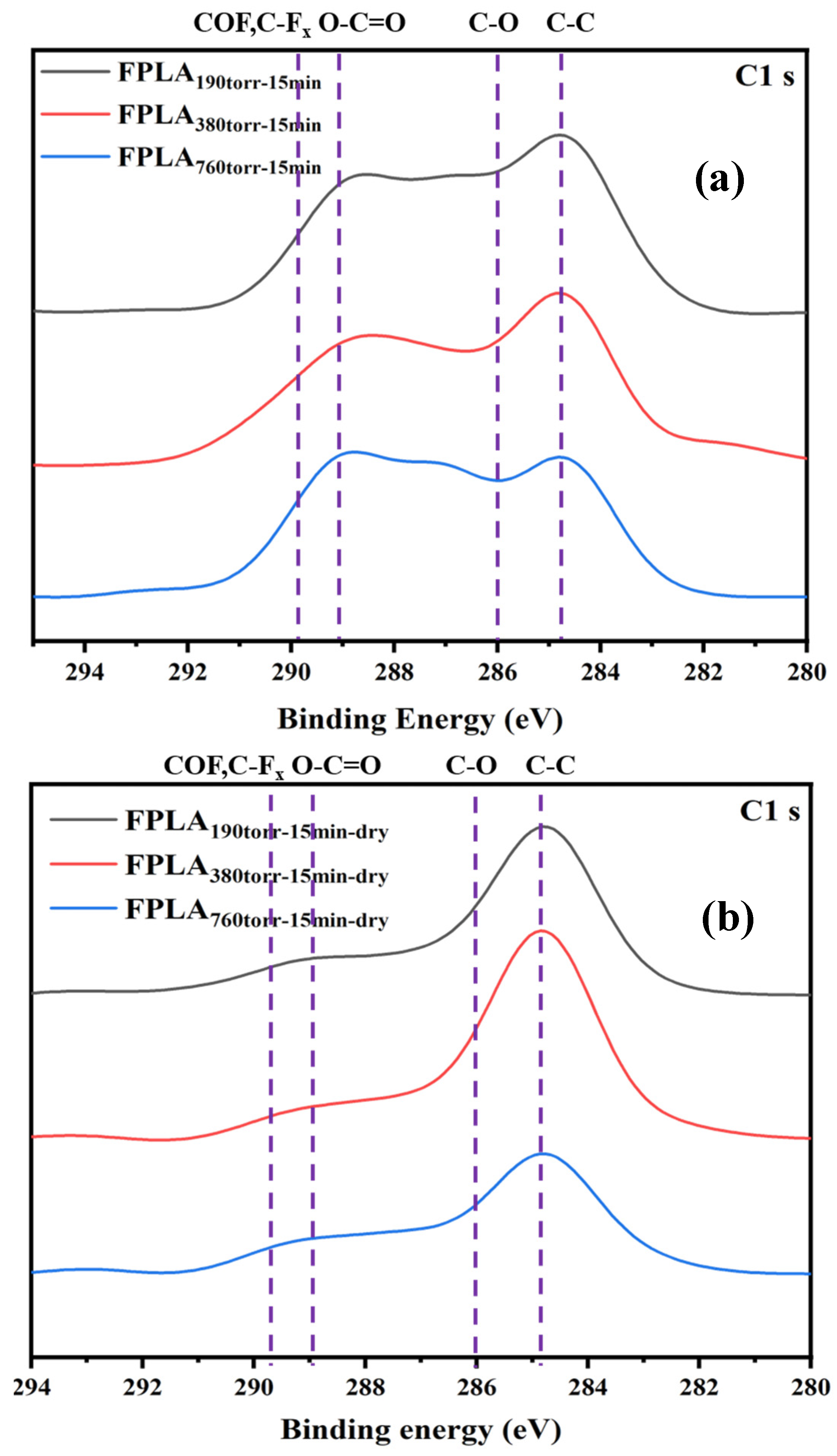

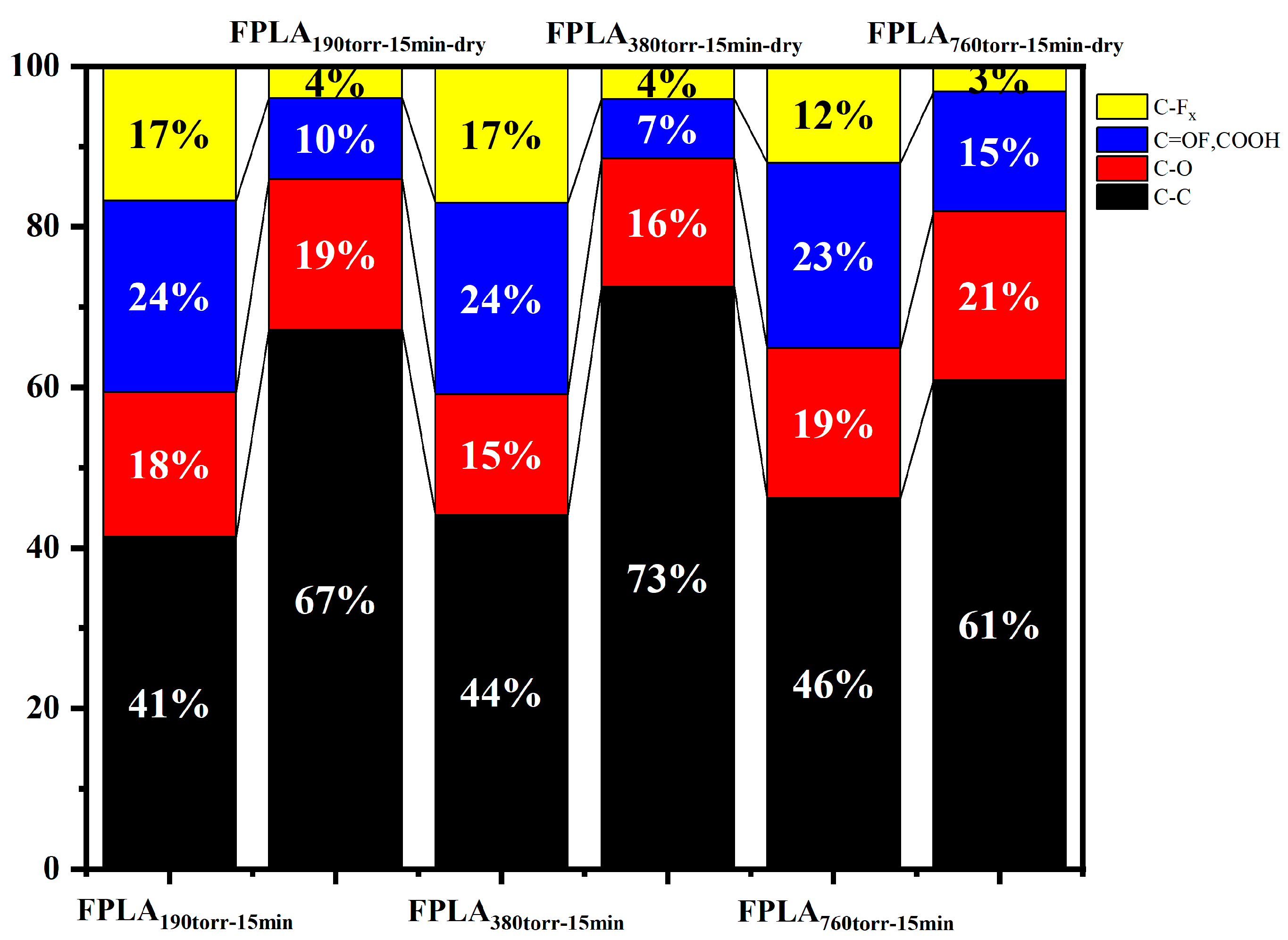

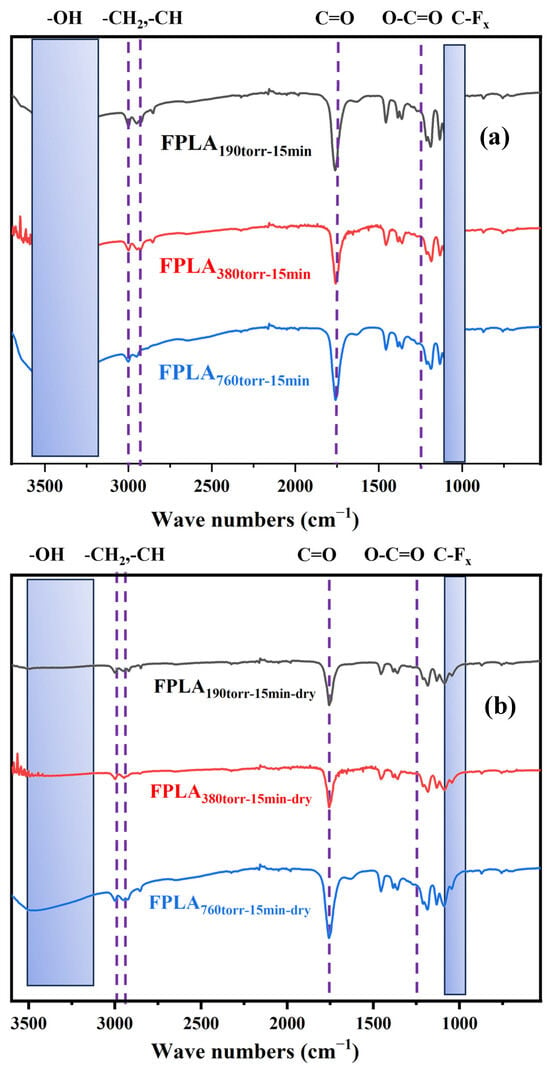

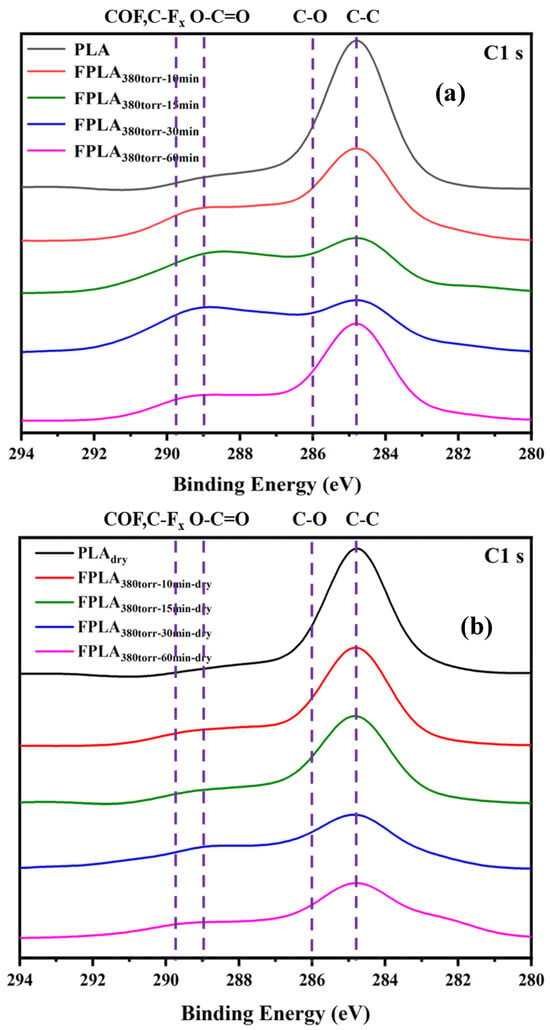

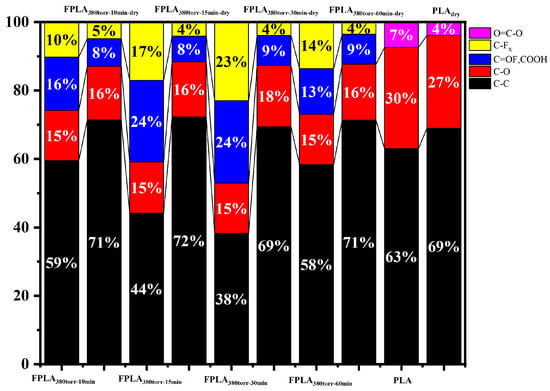

Because FT-IR is not sensitive to fluorine, only some C-Fx peaks can be observed. It is very difficult to analyze the content of fluorine. Therefore, XPS can be used to determine the fluorine content more accurately. Figure 3 shows the XPS spectra of the C1 s of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times. A strong C-C peak was observed at 284.8 eV in PLA, and C-O (286.0 eV) and O-C=O (288.9 eV) were also observed [33]. After fluorination, the C-C content decreased, whereas the C-O content increased. The O-C=O peak shifted to a lower energy (288.0 eV) and changed to -COF and -COOH. The C-Fx peak appeared at 289.5 eV [25,26,32,34]. This is because the C-C bonds are converted into C-Fx, and thus the intensities of this peak increase, while the intensity of the C-C peak decreases. In addition, owing to the high reactivity of F, O-C=O easily forms -COF, which is then easily hydrolyzed into -COOH and C-OH. As a result, the C-O content increases, and O-C=O moves to low energy, changing into -COF and -COOH. During drying, thermal effects caused the C-F bonds to continue reacting and generated CF4 that overflowed from the surface. C-Fx content decreases. In addition, -COF and -COOH also re-crosslinked, leading to a decrease in the C=O peak and a slight increase in the C-O peak. Figure 4 shows the percentage of functional group content of untreated, fluorinated, and dried samples, as calculated based on the peak distribution of XPS results (Figure 3) It is evident that the C-C peak decreases to varying degrees after fluorination. The decrease rate first increased and then decreased with increasing reaction time, similar to the trend observed for C-Fx content, which first increased and then decreased. In contrast, the peak intensities of -COF and -COOH also showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. This is consistent with the C-Fx change during the fluorination process. After drying, the intensities of the peaks related to fluorine decreased, while the intensity of the C-C peak increased. This is consistent with the thermal effects leading to re-crosslinking.

Figure 3.

XPS images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction durations.

Figure 4.

Percentage of functional group contents calculated from XPS results (Figure 3).

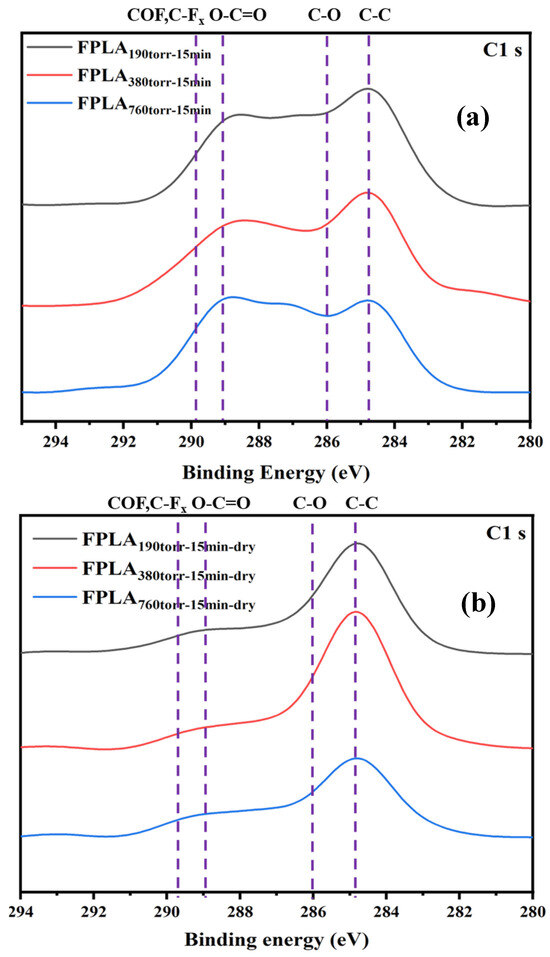

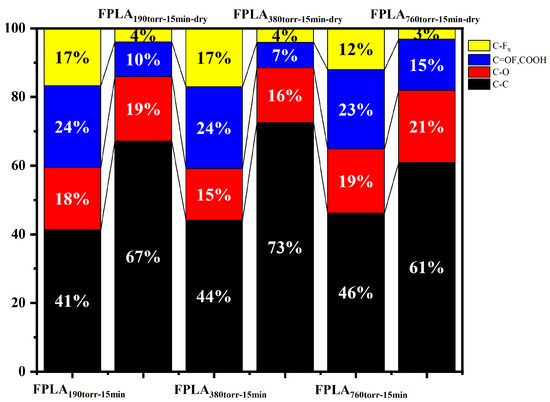

Figure 5 shows the XPS spectra of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different F2 contents. The changes in the peak intensities of the different F2 contents were similar to those of the different reaction times. Similarly to the samples at different reaction times, after fluorination, the C-C peak decreased, whereas C-Fx, -COF, and -COOH appeared. After drying, CF4 was generated, and the intensity of the F-related peak decreased. The C peak was strengthened after re-crosslinking. Figure 6 shows the percentage of functional group content of the fluorinated and dried samples for different F2 contents. This shows that both fluorination and drying treatment, for low F2 content samples, the bond content changes are consistent with the samples of short reaction time. The high F2 content sample showed the same trend as the samples with long reaction times.

Figure 5.

XPS images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different F2 contents.

Figure 6.

Percentage of functional group contents calculated from XPS results (Figure 5).

This can be understood as follows: for short fluorination (short reaction time or low F2 content), the degree of reaction is low, and fluorine can accumulate. This will show that the content increases with time or content increases. When long fluorination (long reaction time or high F2 content) is performed, the degree of reaction is high, and fluorine cannot continue to accumulate. This will escape from the surface as CF4, and thus, the content actually decreases.

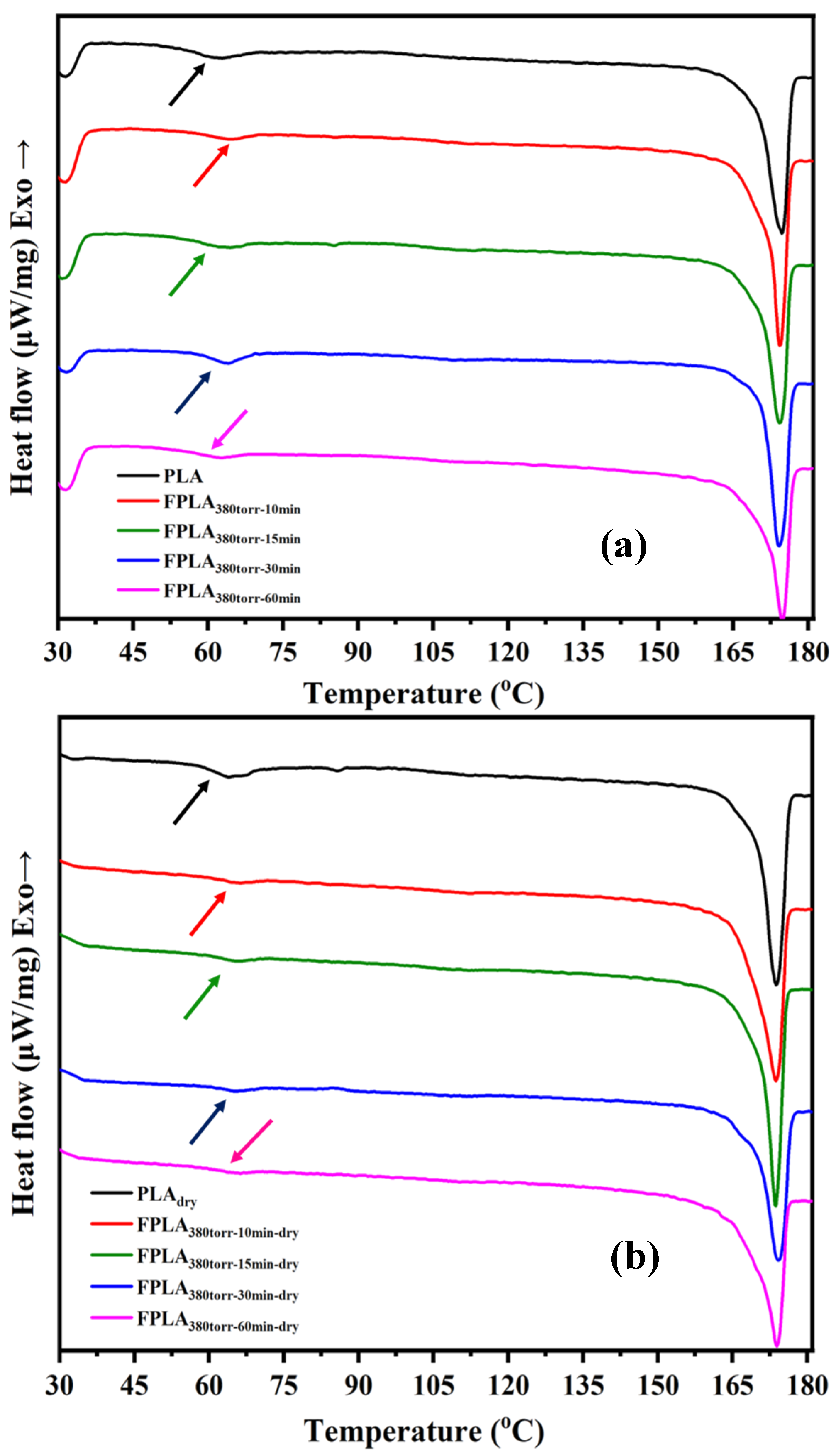

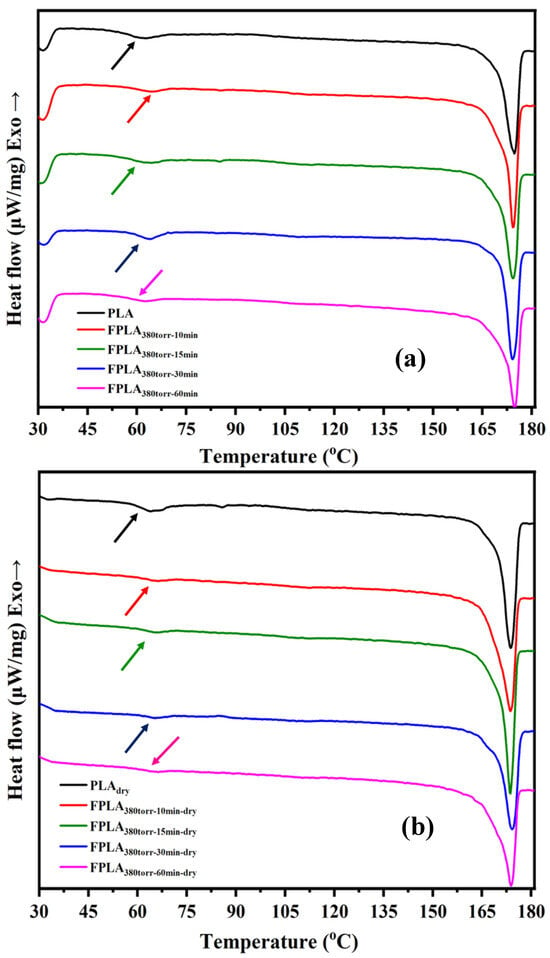

3.2. Effects of Fluorination and Drying on Thermodynamic Properties

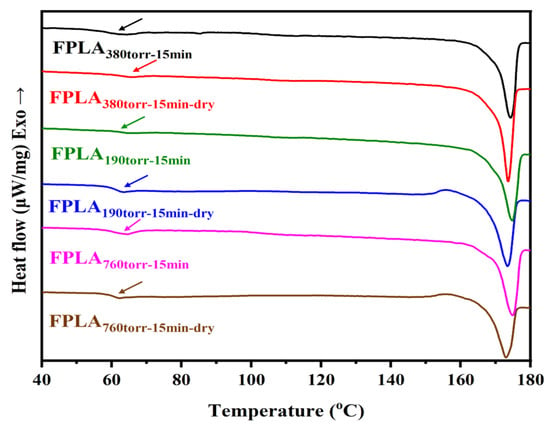

Figure 7 shows the DSC spectra of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times and Table 1 is the Tg values of all samples. For the fluorinated samples, Tg was higher than that of PLA [35,36]. The Tg both FPLA380torr-15min and FPLA380torr-30min are higher than 60 °C. The change in Tg was consistent with that of the surface fluorine content, which first increased and then decreased. This may be because fluoride (C-Fx) is formed on the sample surface, increasing the surface polarity and thus increasing the Tg value. Because fluorine increases over time, generating CF4 that overflows from the surface, the Tg values trend initially increases and then decreases.

Figure 7.

DSC images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction times.

Table 1.

Tg values of fluorinated and dried samples with different reaction times.

After drying, the Tg values of all the samples increased. The Tg can reach up to 63 °C. When PLA is heated, the molecular chains are close to one another. Therefore, the increase in crosslink density results in an increase in Tg values. In addition, for all the fluorination samples, the fluorine atoms on the chain segments formed hydrogen bonds with the hydrogen atoms. In addition, C=OF is converted to COOH. Under the influence of heat, COOH undergoes decarboxylation or re-crosslinking. For both reasons, the fluorinated samples showed higher Tg values than PLA after drying.

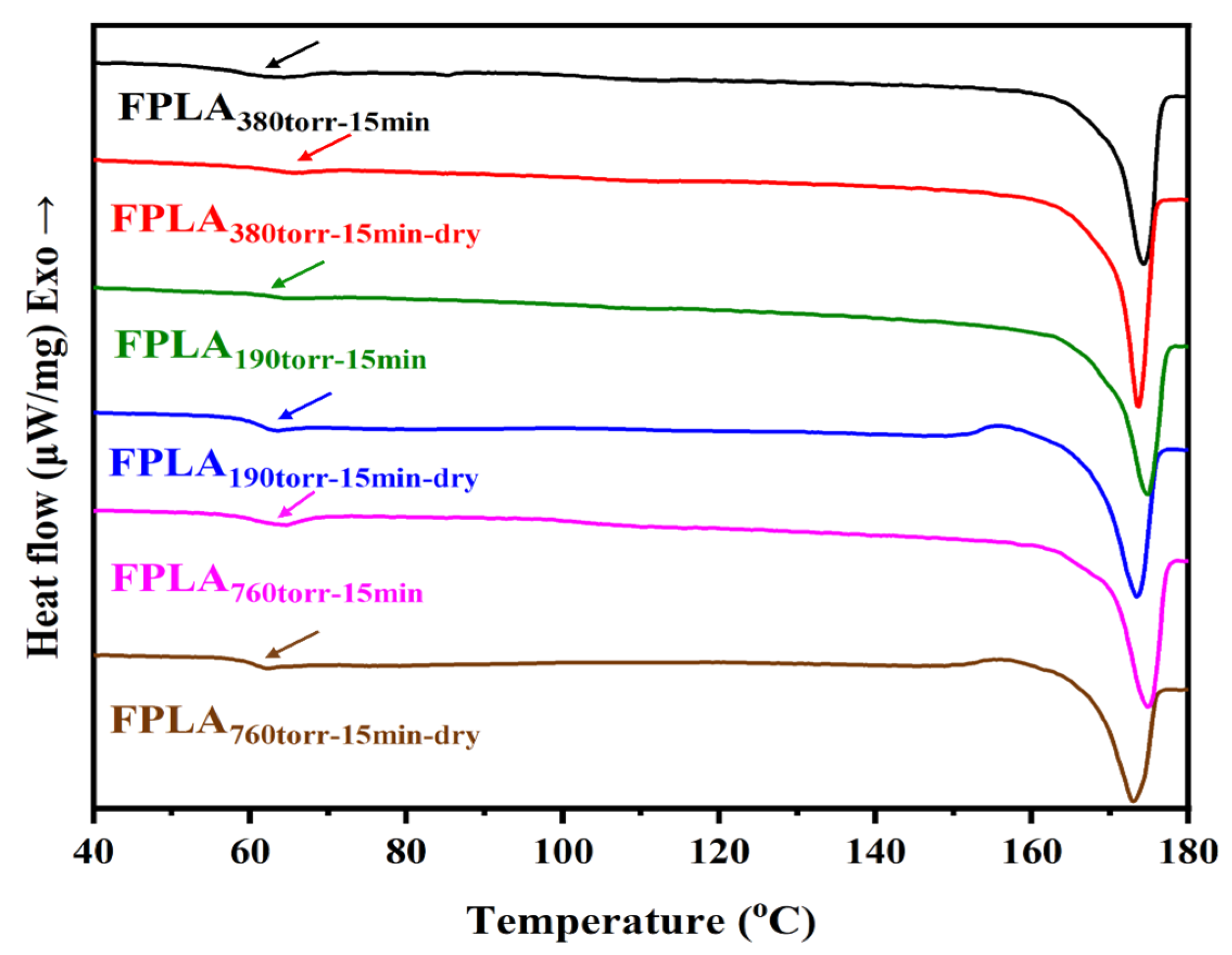

Figure 8 shows the DSC spectra of the fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents and Table 2 is the Tg values of all samples. Consistent with the above, the Tg values increased after fluorination. The change in Tg coincided with the change in C-Fx on the sample surface, showing an initial increase followed by a decrease. The Tg values of the samples increased further after drying. This can be attributed to the increase in the crosslink density. The degree of increase was related to C-Fx.

Figure 8.

DSC images of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

Table 2.

Tg values of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

3.3. Effects of Fluorination and Drying on the Surface Properties and Morphology

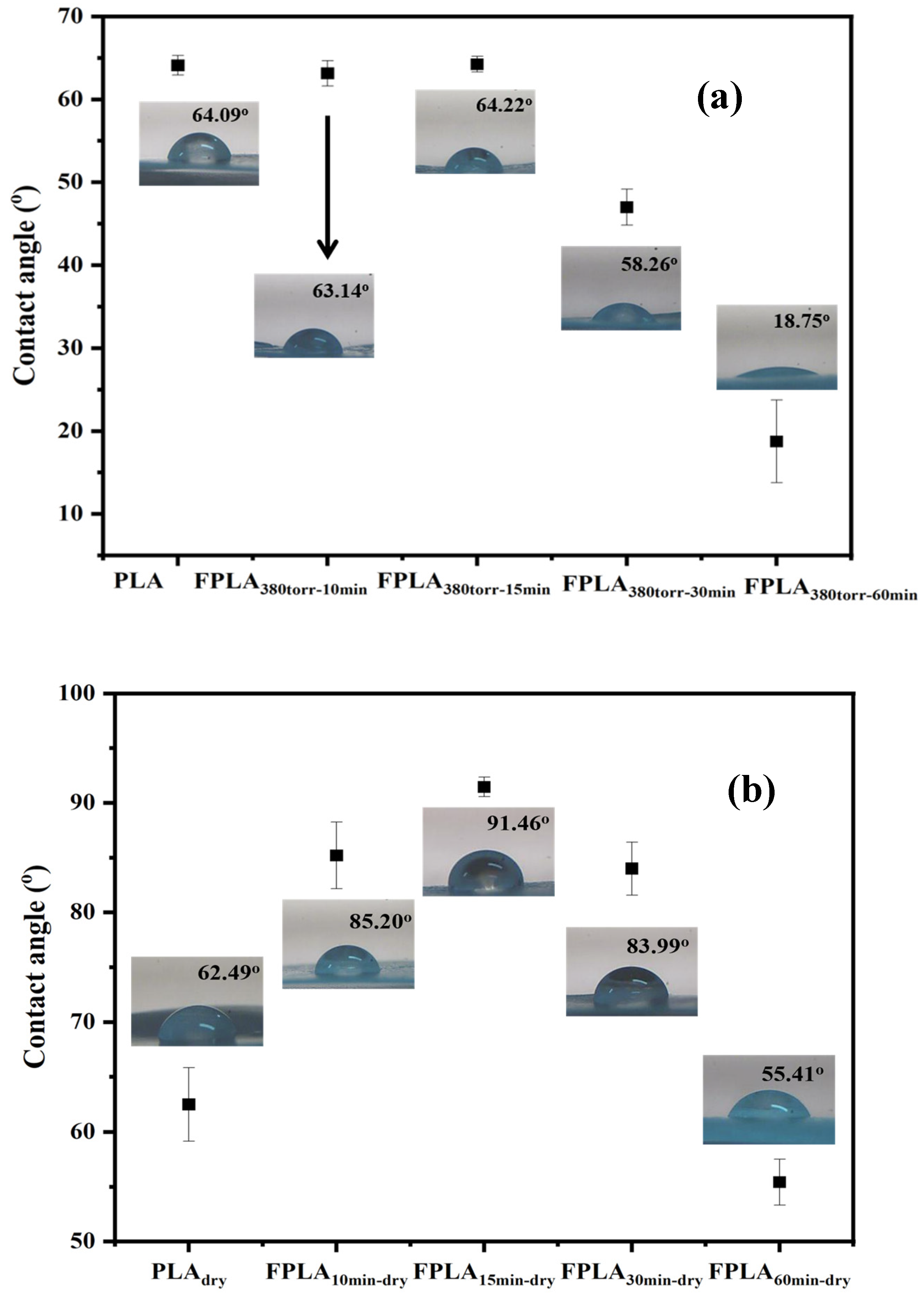

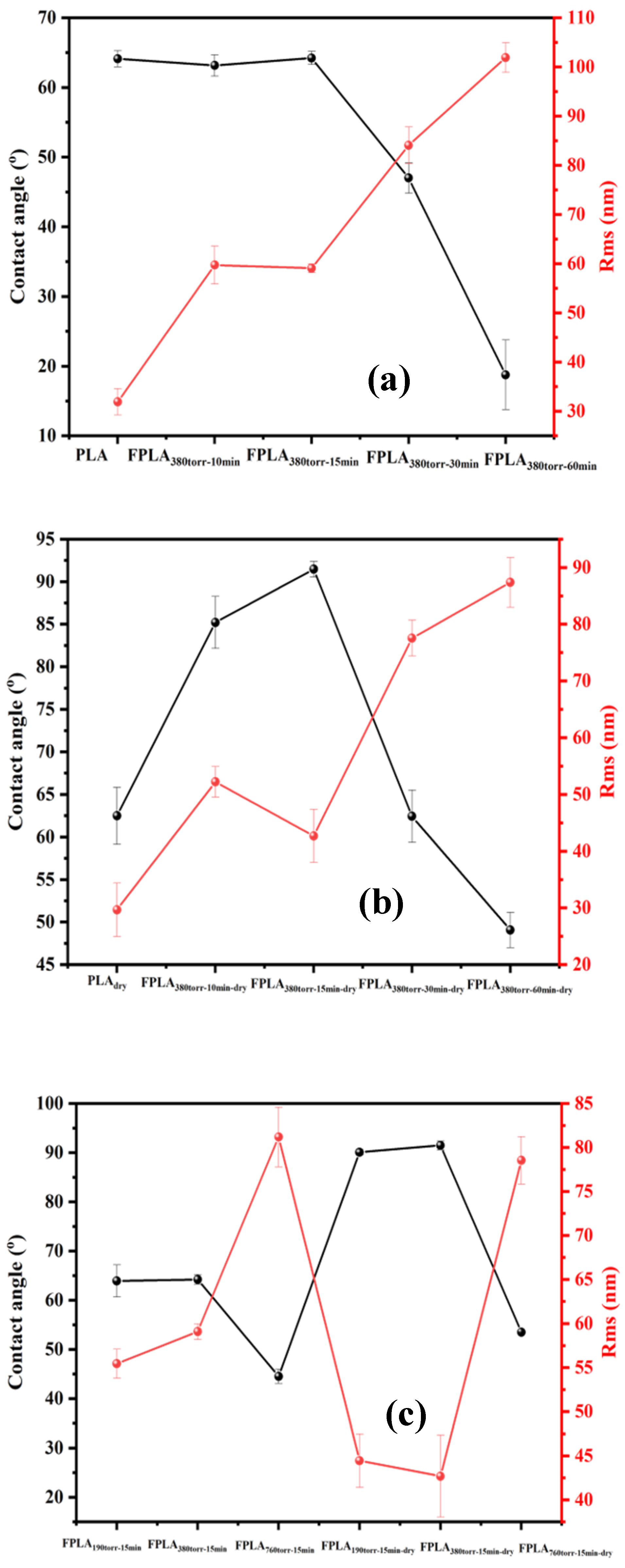

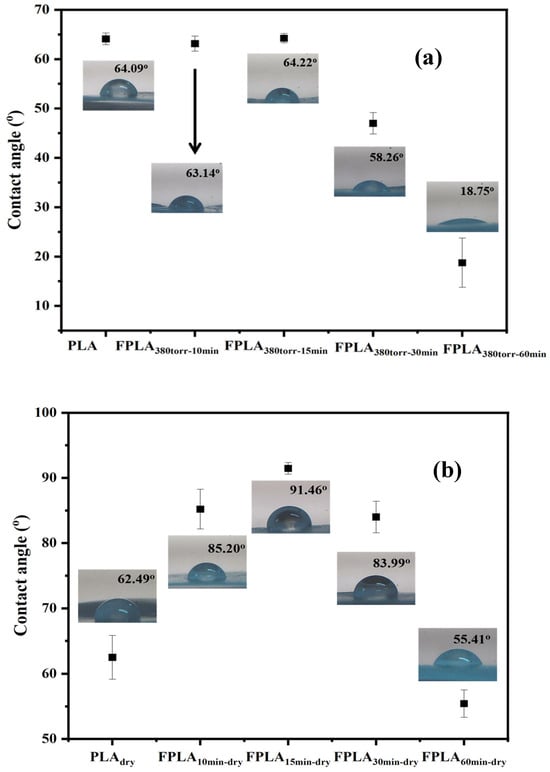

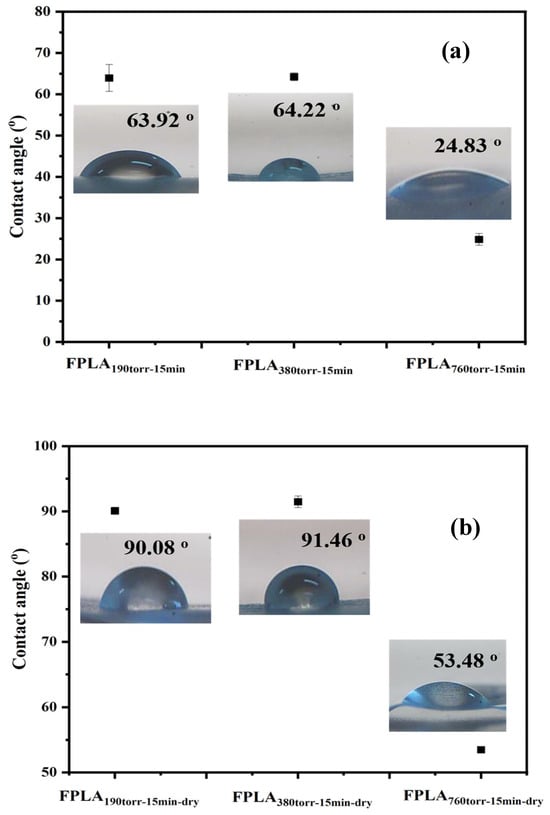

The WCA can directly observe whether the surface of the film is hydrophilic or hydrophobic. Figure 9 shows the WCA of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times and Table 3 is the WCA values of all samples. The WCA of the untreated PLA film, the WCA is 64.09°. However, after fluorination, the WCA of all fluorinated samples decreased. For the fluorinated samples, FPLA380torr-10min and FPLA380torr-15min, the values changed; however, as the reaction progressed, the WCA decreased. In particular, for the FPLA380torr-60min sample, the WCA can be as low as 18.75°, which indicates considerable hydrophilicity. For the dried samples, the WCA of the fluorinated samples increased significantly, whereas that of the untreated sample did not change. Among them, FPLA380torr-15min-dry can reach 91.46°, showing a hydrophobic surface.

Figure 9.

WCA values of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction durations.

Table 3.

WCA values of fluorinated and dried samples with different reaction times.

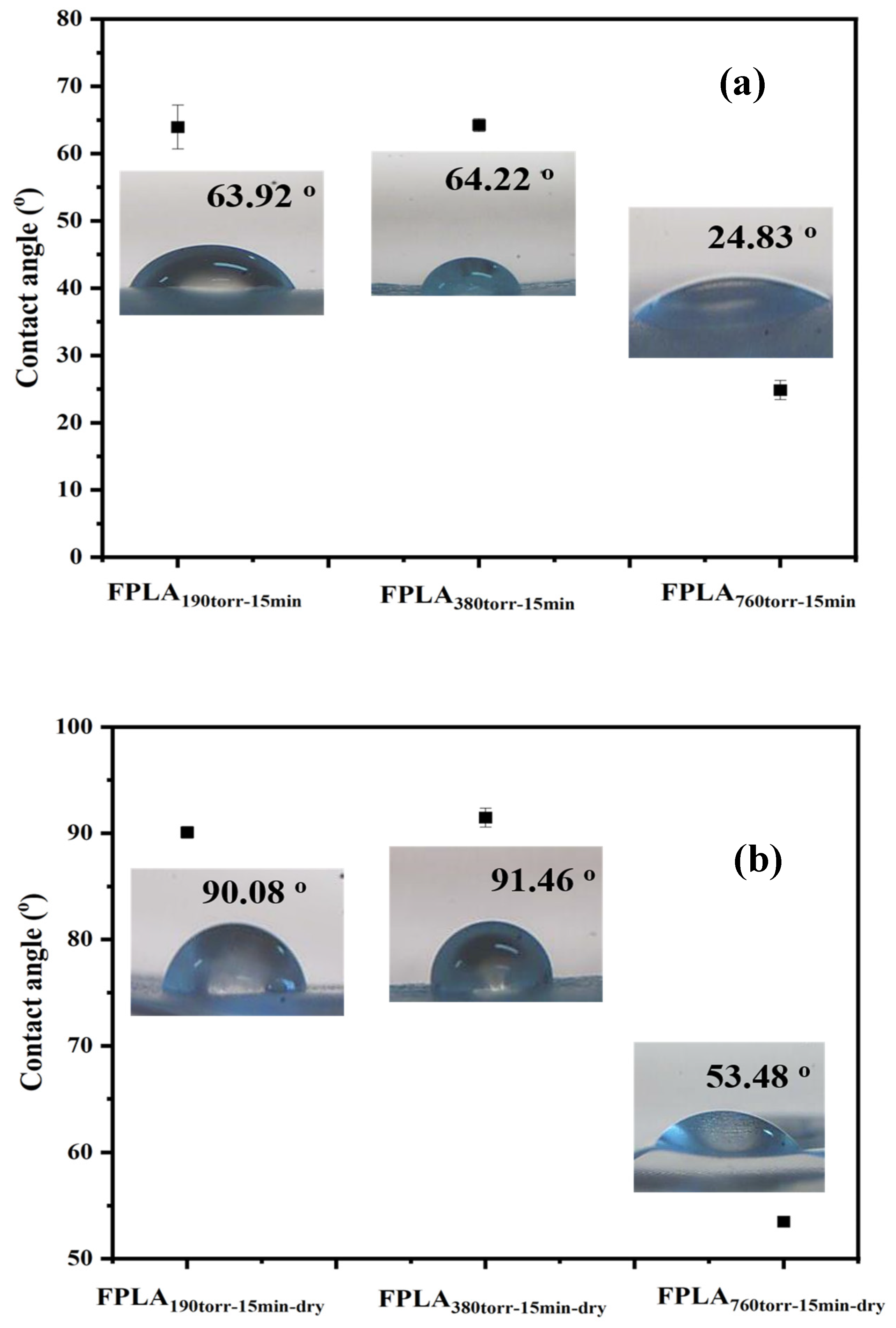

Figure 10 shows the WCA with (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different F2 contents and Table 4 is the WCA values of all samples. For the fluorinated samples, the WCA decreased in the same manner as that of the samples in Figure 9a. After drying, the WCA of both samples FPLA190torr-15min and FPLA380torr-15min reached over 90°, showing hydrophobicity. As mentioned above for FT-IR, XPS, and DSC, the increase in WCA is attributed to the reduction in surface polar groups and the increase in crosslinking density after drying. Such a large change in WCA from fluorinated to dry may be due to the fact that when fluorination begins, the introduced fluorine atoms increase the polarity of the surface. As an excellent polar solvent, water spreads easily on polar surfaces, thus decreasing the WCA. As the reaction time increased, the degree of fluorination also increased. C-Fx on the surface continues to react to generate CF4 and escape from the surface. This process leads to a rough and porous surface, which facilitates water penetration into the PLA, further reducing the WCA. After drying, the surface chains of all the samples were close to each other. This results in an increase in the crosslink density through hydrogen bonding between the chains. Simultaneously, the COOH on the surface undergo decarboxylation and re-crosslinking reactions under heating conditions. This also leads to an increase in the crosslink density. In addition, the polar components on the surface decreased. For these two reasons, the WCA will improve.

Figure 10.

WCA values of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different F2 contents.

Table 4.

WCA of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

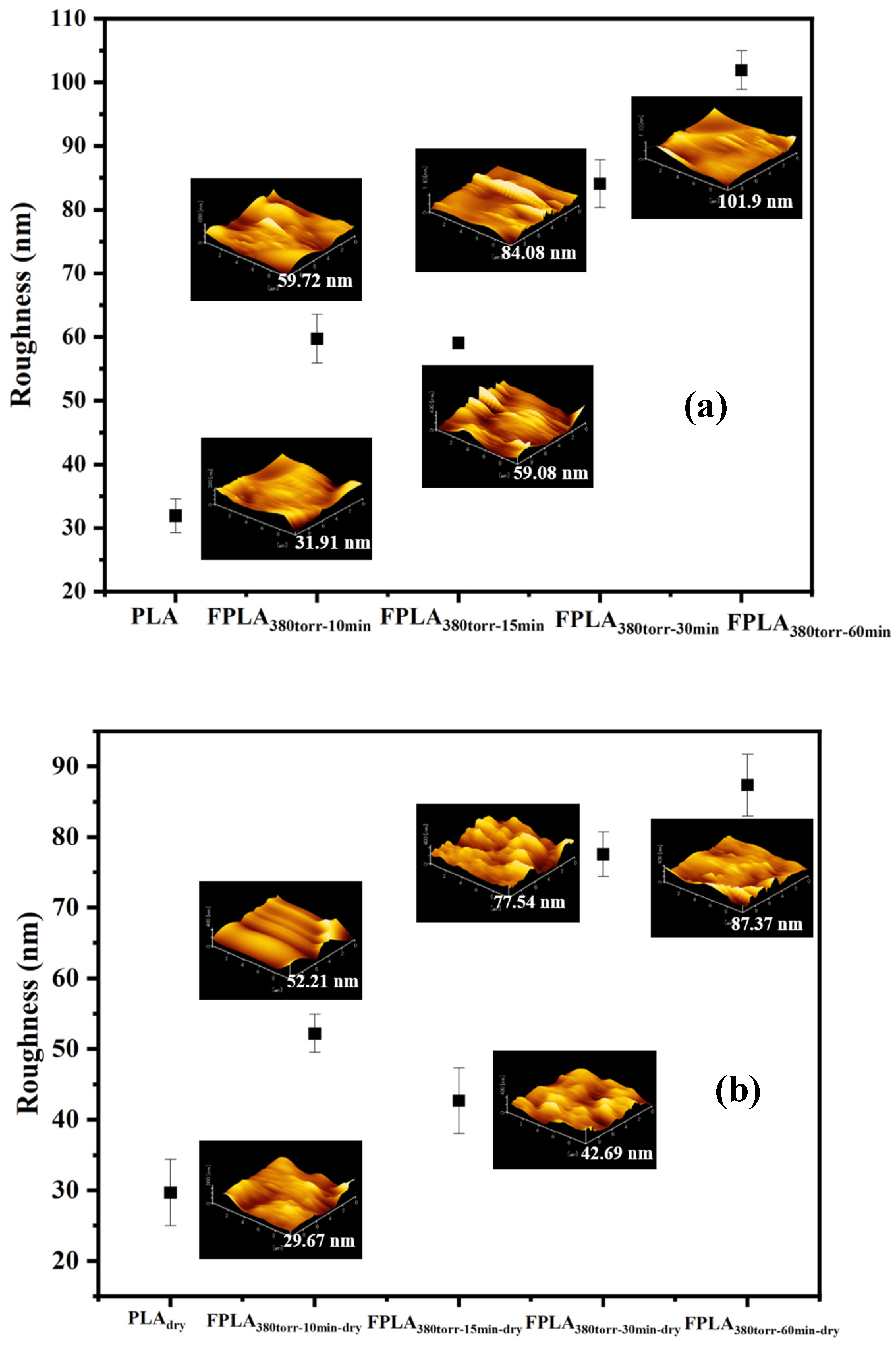

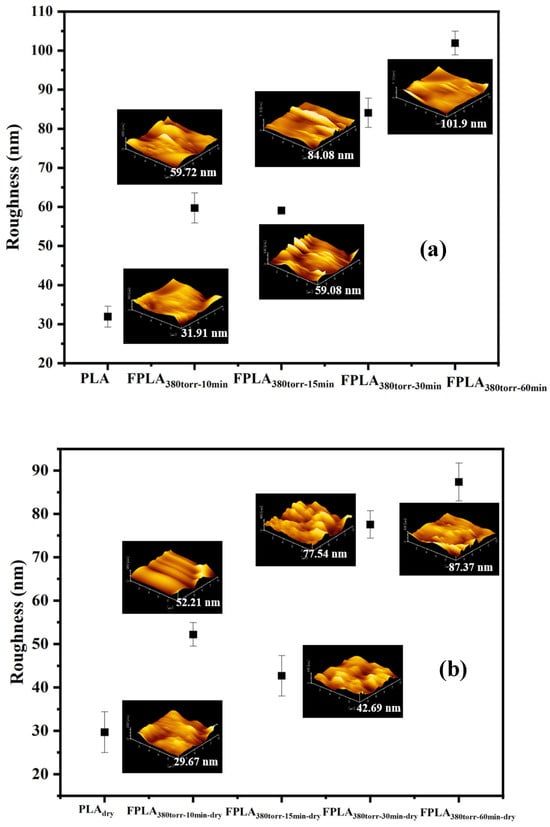

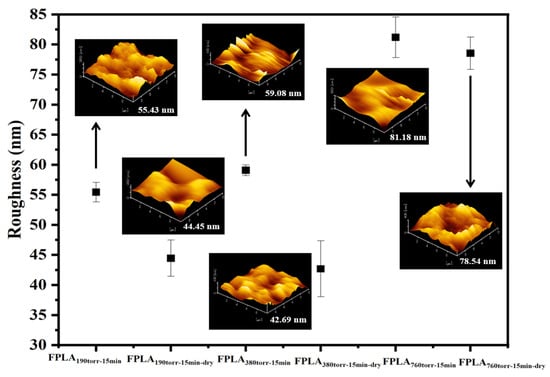

To confirm the effect of fluorination and drying on the surface roughness of the PLA samples, AFM measurements were useful for directly observing the surface changes. Figure 11 represents the AFM images of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times and Table 5 is the AFM values of all samples. All fluorinated samples exhibited greater roughness than PLA. For FPLA380torr-10min and FPLA380torr-15min, the increase in roughness is nearly identical. However, when the reaction time was extended to 30 min or more, the roughness continued to increase. This may be because the fluorine atoms introduced by fluorination generate F-related groups, which increase the surface protrusions and thus the roughness. In addition, over time, C-Fx is converted into CF4 and escapes from the surface. The concave structure formed after the CF4 overflow on the surface further increased the roughness of the sample surface. After drying, the roughness of all the fluorinated samples decreased to varying degrees. The PLA showed a slight decrease. This is likely due to the thermal effect, which brought the molecular chains closer together on the sample surface. This allows the fluorine atoms to form hydrogen bonds more easily with the hydrogen atoms, which increases the crosslink density and reduces the roughness. In addition, the decarboxylation and re-crosslinking of COOH further increased the crosslink density of the fluorinated sample. Therefore, the roughness change in the fluorinated sample was more obvious than that of PLA.

Figure 11.

AFM images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction times.

Table 5.

AFM of samples fluorinated and dried for different reaction times.

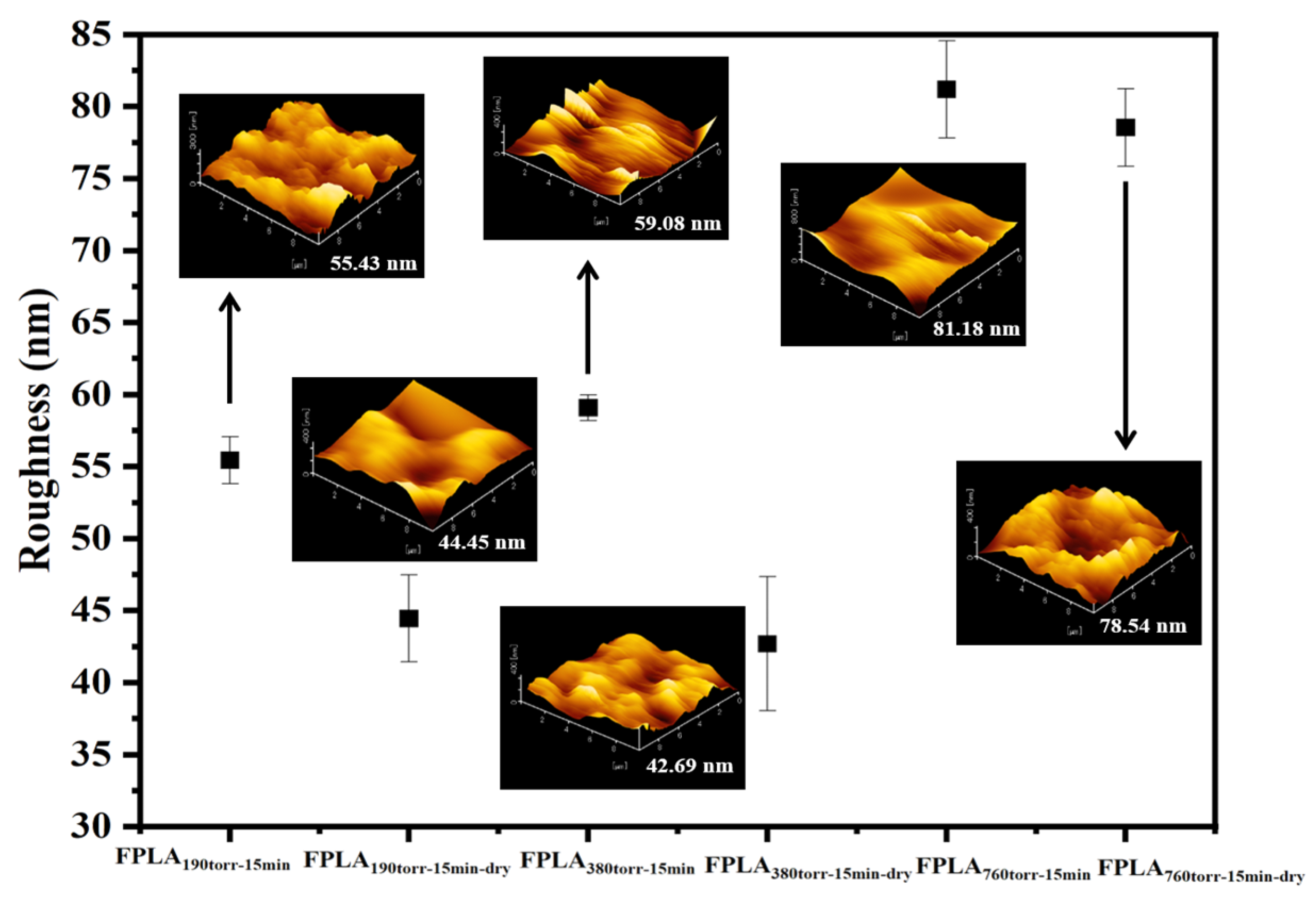

Figure 12 shows the AFM images of the fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents and Table 6 is the AFM values of all samples. Similarly to the samples with different reaction times, the surface roughness of all samples increased after fluorination. The roughness first changed slightly and then increased dramatically with increasing F2 content. After drying, the roughness of all fluorinated samples decreased, which is consistent with the analysis above.

Figure 12.

AFM images of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

Table 6.

AFM values of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

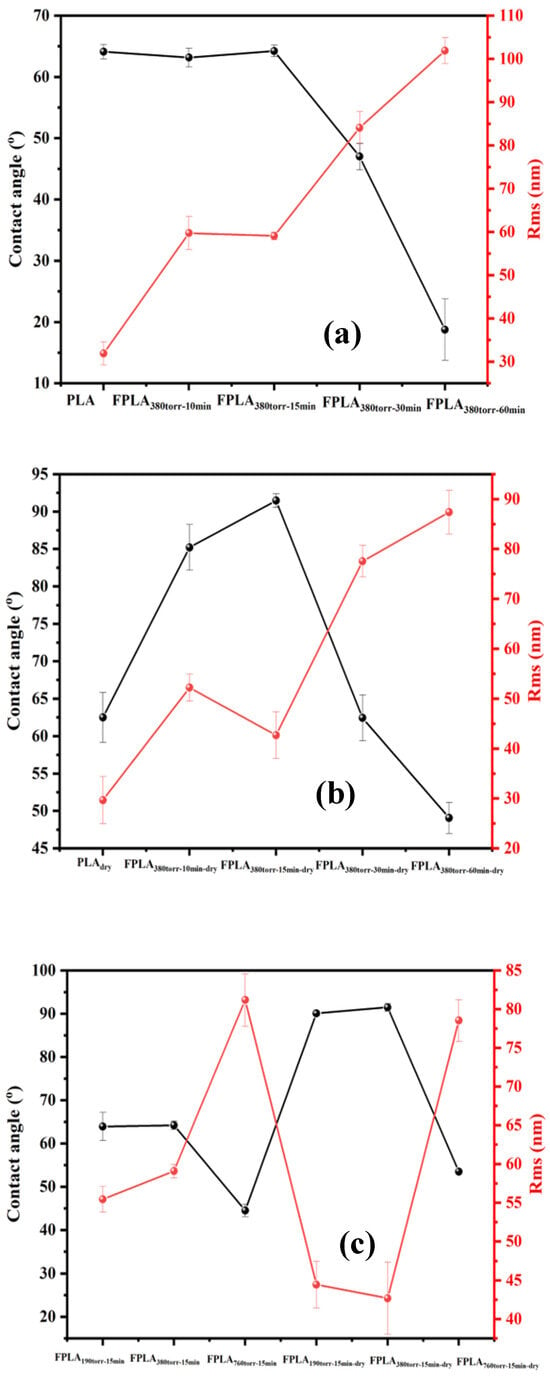

The WCA-AFM figures allow for a more intuitive analysis of the relationship between the WCA and roughness. Figure 13 shows the WCA-AFM with (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times, as well as (c) fluorinated and dried samples for different F2 contents. The figures show that the WCA and roughness of the fluorinated samples with different reaction times and F2 contents are inversely proportional. The smaller the WCA, the greater the roughness. This is because the C-Fx and C=OF generated after fluorination increase the surface polar protrusions and hydrophilicity. The sample under long fluorination conditions showed an increase in surface defects owing to the generation of CF4. This further increased the hydrophilicity, which is consistent with the FT-IR and XPS analyses above. After drying, the roughness of all fluorinated samples decreased, whereas the WCA increased. When the roughness was lower than 45 nm, the sample was hydrophobic. This is due to the increase in crosslink density and reduction in polar groups after the drying process. This is consistent with the XPS and DSC analyses.

Figure 13.

WCA-AFM values of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction times and (c) fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

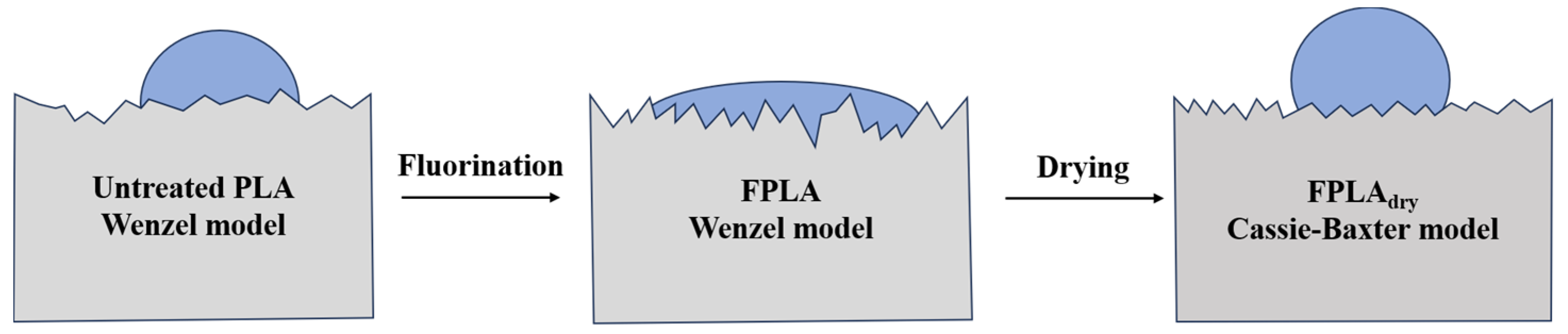

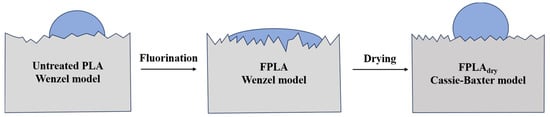

Based on the WCA and AFM results, it can be inferred that PLA conforms to the Wenzel model after fluorination. The Wenzel model [37] assumes that the liquid completely wets the grooves of a rough surface, in which case the roughness amplifies the original wettability of the material surface.

where θW is the actual contact angle, θY is the Young’s contact angle (the contact angle of an ideal smooth surface), and is the roughness coefficient (the ratio of the actual contact area to the apparent contact area). PLA is hydrophilic, and fluorination significantly increases its surface roughness (SR). According to the Wenzel model, a surface that is originally hydrophilic becomes even more hydrophilic when its roughness is increased. After heat treatment, the liquid wetting model may transform into the Cassie–Baxter model [38], where some areas are in solid–liquid contact, while others trap gas, forming a gas–liquid interface.

where θCB is the actual contact angle, f1 is the proportion of the solid–liquid contact area, and is the proportion of the gas–liquid contact area (satisfying + = 1). A composite structure was formed on the surface owing to the decarboxylation reaction and re-crosslinking after the heat treatment. Water did not completely wet the surface and partially contacted air, thus increasing the contact angle.

Figure 14 shows the wetting model images of the hydrophilic–hydrophobic surfaces modified by fluorination and drying.

Figure 14.

Wetting model images of hydrophilic–hydrophobic surfaces modified by fluorination and drying.

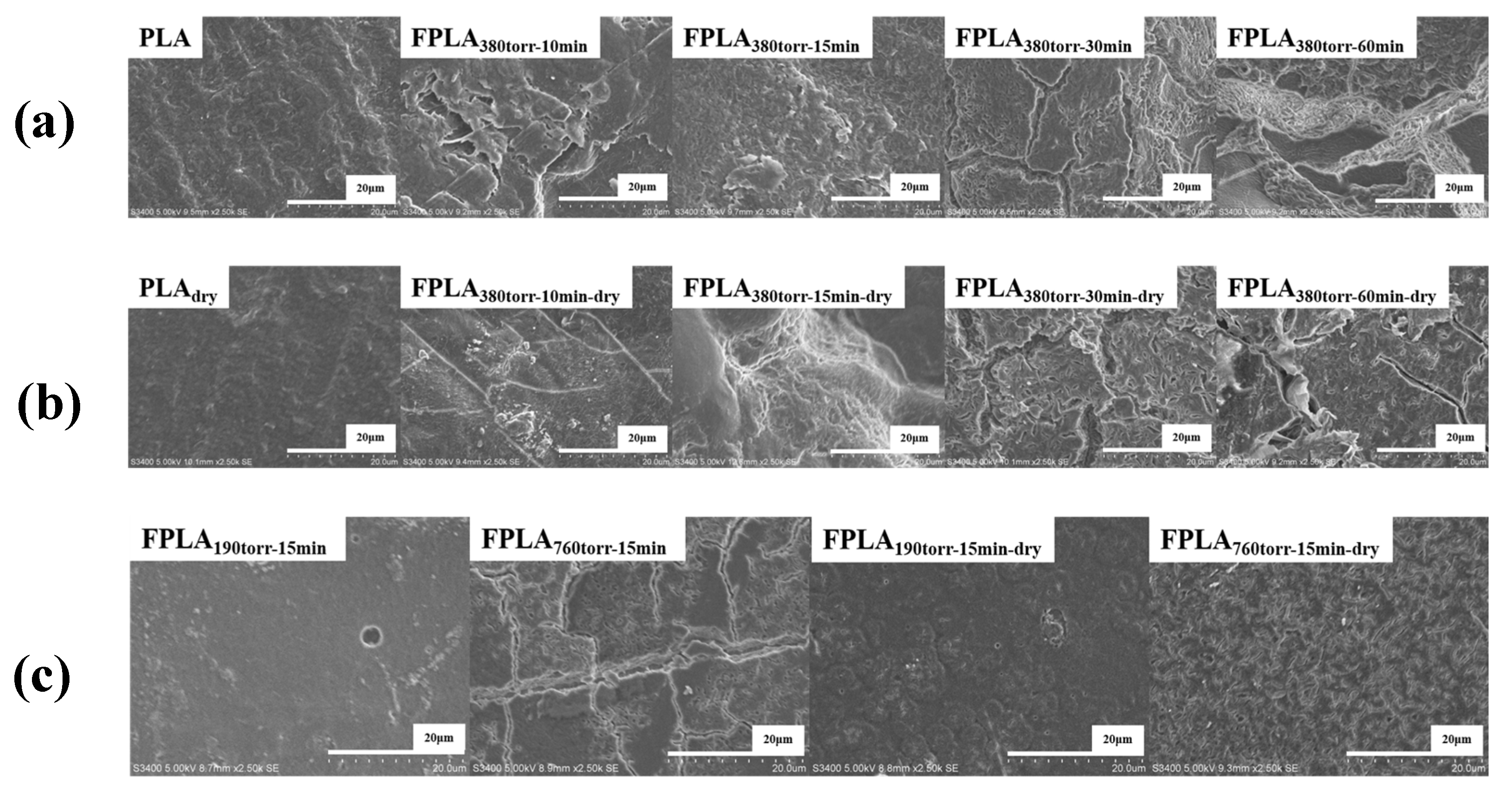

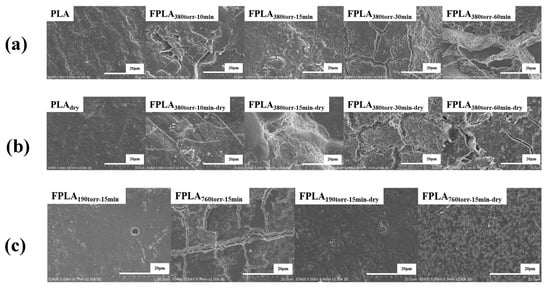

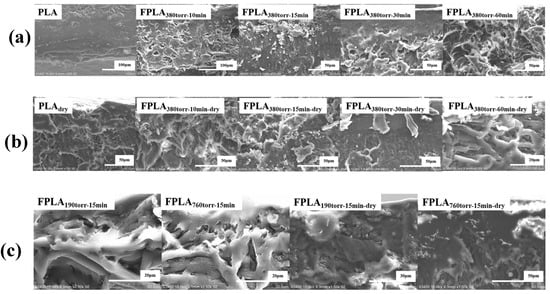

To observe the sample surface more accurately, SEM was used to directly analyze the morphology and surface changes. Figure 15 shows the surface SEM images of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times, as well as (c) fluorinated and (d) dried samples for different F2 contents. Untreated PLA has a smooth surface, similar to that of dried PLA. After fluorination, the surface became rough. For the short fluorination samples, a scaly surface structure began to appear. This is caused by C-Fx and C=OF generated during fluorination. The surface roughness changed consistently with the degree of reaction. However, the surface morphologies of the long-fluorinated samples changed dramatically. The scaly structure was replaced by numerous pores and cracks. This is consistent with the conclusion that the conversion of C-Fx to CF4 further damages the surface. Furthermore, the more severe the conditions, the deeper the damage. Therefore, the surface hydrophilicity increased with the degree of fluorination. After drying, the fluorinated samples exhibited a reduced scaly structure but a significant increase in pores. This is due to the thermal effects, which cause C-Fx to convert to CF4 and overflow from the surface, as well as the re-crosslinking of C=OF. This change was less pronounced in samples with long fluorination. This may be caused by excessive surface damage after fluorination. This cannot be offset by drying.

Figure 15.

SEM surface images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction times and (c) fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

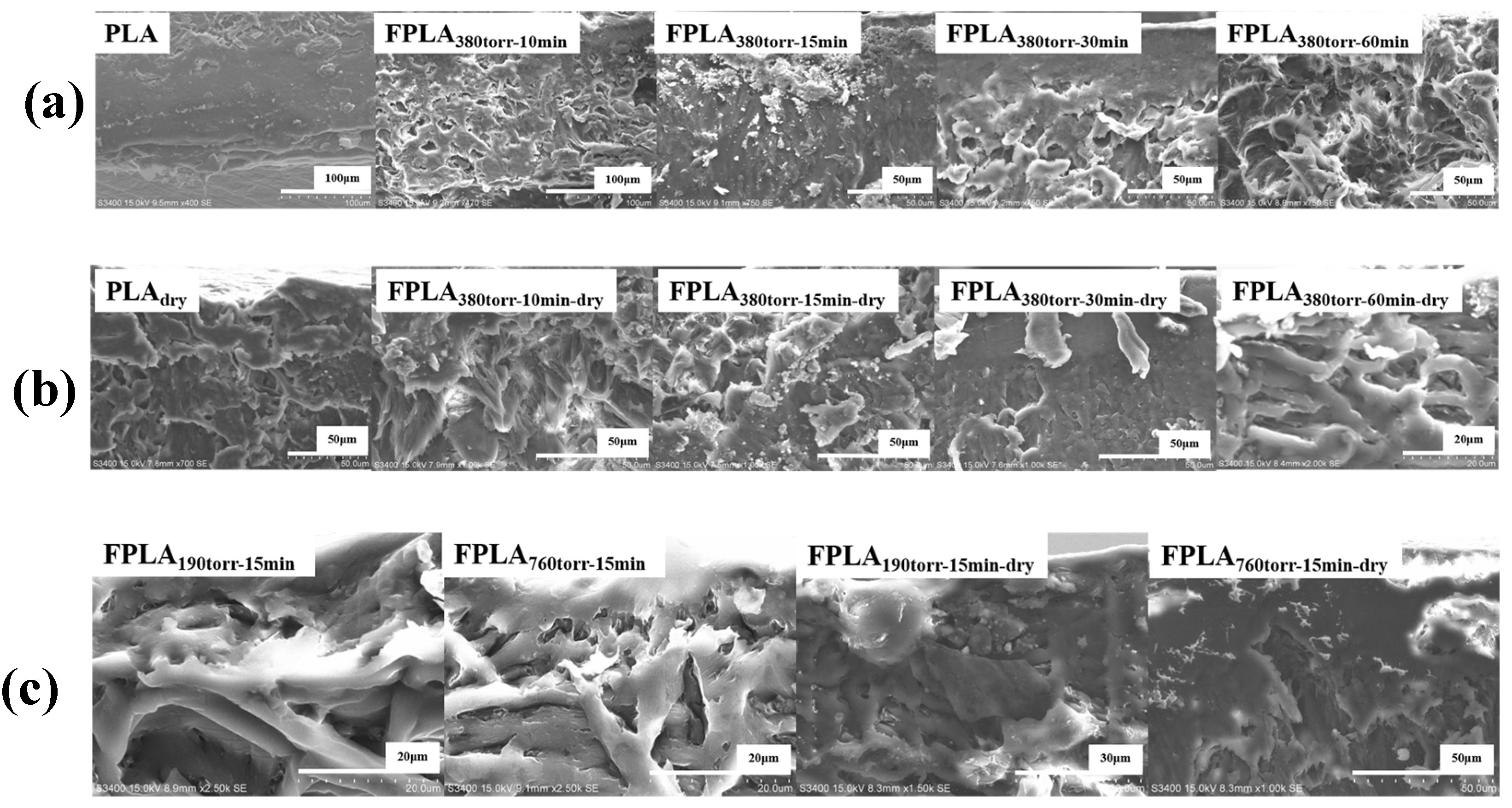

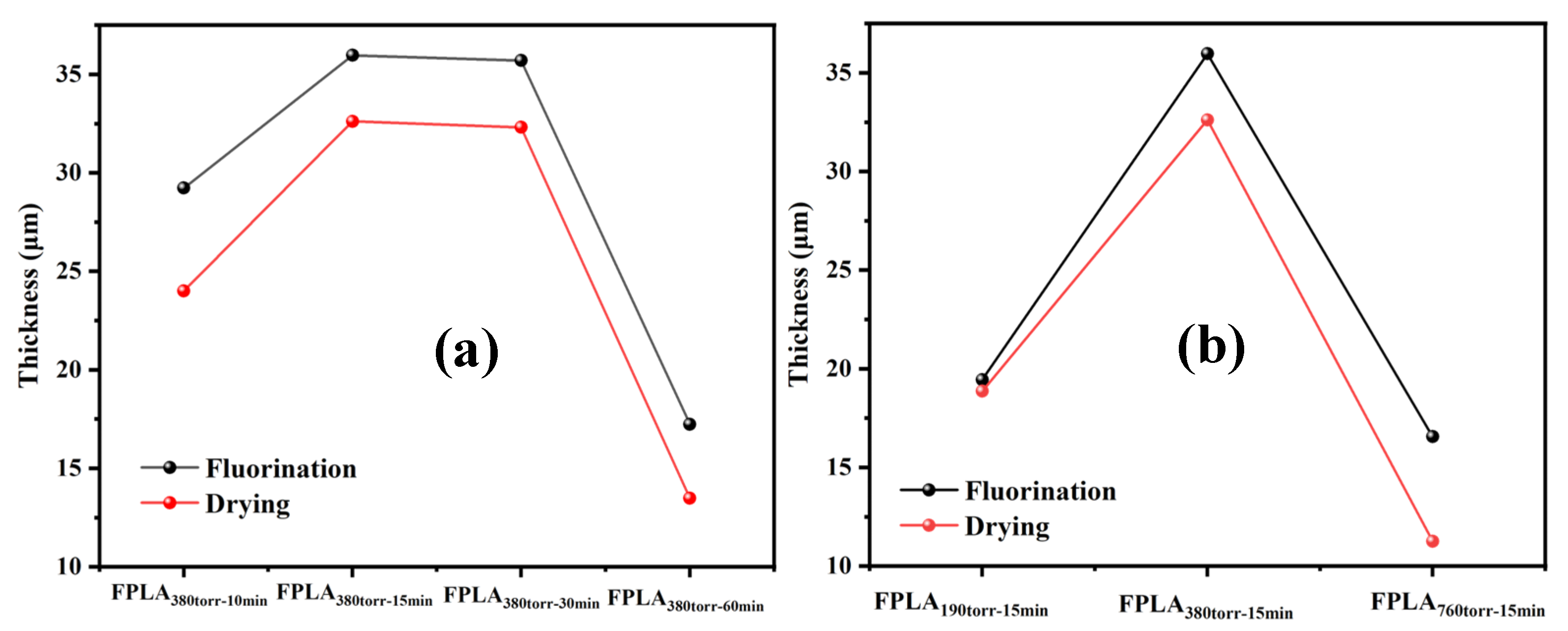

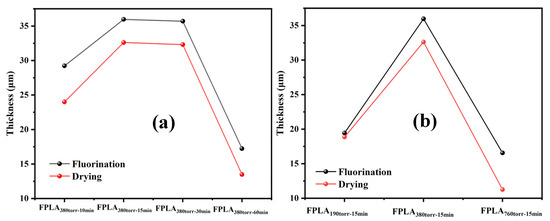

The thickness of the fluorinated layer was determined by elemental analysis of the sample sections. Figure 16 shows the SEM images of (a) untreated and fluorinated and (b) dried samples for different reaction times and (c) fluorinated and dried samples for different F2 contents. Figure 17 shows the thickness of the fluorinated layer for (a) different reaction times and (b) different F2 contents by elemental analysis. As shown in Figure 16, the thickness of the fluorinated layer of the fluorinated sample first increased and then decreased as the reaction time and F2 content increased. The thickness of the fluorinated layer is closely related to C-Fx. Consistent with the above analysis, F2 reacts with PLA during short fluorination and is continuously accumulated. Therefore, the thickness of the fluorine layer increased with the degree of reaction. However, during long fluorination, under the continuous attack of F2, some C-Fx is converted to CF4. CF4 escaped from the surface, causing the thickness of the fluorinated layer to decrease. Therefore, the thickness of the fluorinated layer decreased with increasing reaction rate. After drying, some C-Fx continued to convert to CF4 upon heating and overflowed the surface. Additionally, C=OF undergoes decarboxylation or re-crosslinking reactions. Therefore, the thickness of the fluorinated layer decreased further after drying.

Figure 16.

SEM sectional images of (a) fluorinated and (b) dried samples with different reaction times and (c) fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

Figure 17.

Thickness of the fluorinated layer on PLA samples with (a) different reaction time and (b) different F2 contents.

4. Conclusions

This study elucidated the changes in the surface properties and morphology of PLA films under direct fluorination and drying treatments. PLA films were fluorinated at room temperature under varying conditions: fluorine concentrations ranging from 190 to 760 Torr and reaction times ranging from 10 to 60 min. Parts of the fluorinated samples were dried at 70 °C for 2 d. FT-IR and XPS analyses confirmed that fluorine successfully reacted with PLA to form -CFx and C=OF on the surface of the fluorinated PLA. The fluorine content on the PLA surface initially increased and then decreased with increasing reaction time or fluorine concentration. This is because the continuous reaction led to the formation and escape of CF4, thus reducing its content. Drying further reduced the surface fluorine content. Furthermore, the increased surface polarity due to fluorination and the increased crosslinking density induced by drying both increased the glass transition temperature of the PLA. The reaction of fluorine gas with PLA introduces polar fluorine atoms and forms a rough and porous surface structure. According to the Wenzel model, fluorination significantly improves the hydrophilicity of PLA surface. The water contact angle decreased from 64.09° to 18.75°, as observed by AFM and SEM. When the fluorinated sample was dried, surface crosslinking increased, surface wetting followed the Cassie–Baxter model, and the WCA increased to 91.46°, exhibiting hydrophobicity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/physchem6010002/s1, Figure S1. SEM-EDS sectional images of fluorinated samples with different reaction times; Figure S2. SEM-EDS sectional images of fluorinated and dried samples with different reaction times; Figure S3. SEM-EDS sectional images of fluorinated and dried samples with different F2 contents.

Author Contributions

Z.H. performed the surface fluorination of all samples and wrote the manuscript. J.-H.K. conducted the XPS analysis of all samples and contributed to writing the manuscript. S.Y. performed the FTIR analysis of all samples. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pang, X.; Zhuang, X.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X. Polylactic acid (PLA): Research, development and industrialization. Biotechnol. J. 2010, 5, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, K.; Kaseem, M.; Yang, H.W.; Deri, F.; Ko, Y.G. Properties and medical applications of polylactic acid: A review. Express Polym. Lett. 2015, 9, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Deng, S.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Polylactic acid (PLA) synthesis and modifications: A review. Front. Chem. China 2009, 4, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corneillie, S.; Smet, M. PLA architectures: The role of branching. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Varshney, S.K. Polylactides—Chemistry, Properties and Green Packaging Technology: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Ramezani Dana, H. Poly lactic acid (PLA) polymers: From properties to biomedical applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2021, 71, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom, J.S.; Hayman, D. An Overview of Mechanical Properties and Material Modeling of Polylactide (PLA) for Medical Applications. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, T.H.; Park, Y.; Hwang, Y. Facile Surface Treatment of 3D-Printed PLA Filter for Enhanced Graphene Oxide Doping and Effective Removal of Cationic Dyes. Polymers 2023, 15, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auras, R.; Harte, B.; Selke, S. An overview of polylactides as packaging materials. Macromol. Biosci. 2004, 4, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthumana, M.; Santhana Gopala Krishnan, P.; Nayak, S.K. Chemical modifications of PLA through copolymerization. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2020, 25, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standau, T.; Zhao, C.; Murillo Castellon, S.; Bonten, C.; Altstadt, V. Chemical Modification and Foam Processing of Polylactide (PLA). Polymers 2019, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordá-Vilaplana, A.; Fombuena, V.; García-García, D.; Samper, M.D.; Sánchez-Nácher, L. Surface modification of polylactic acid (PLA) by air atmospheric plasma treatment. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Favi, P.; Cheng, X.; Golshan, N.H.; Ziemer, K.S.; Keidar, M.; Webster, T.J. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) surface nanomodified 3D printed polylactic acid (PLA) scaffolds for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2016, 46, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Desmet, T.; Dubruel, P.; Leys, C. Plasma Surface Modification of Biodegradable Polymers: A Review. Plasma Process. Polym. 2011, 8, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Villarreal, M.H.; Ulloa-Hinojosa, M.G.; Gaona-Lozano, J.G. Surface functionalization of poly(lactic acid) film by UV-photografting of N-vinylpyrrolidone. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 110, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.Y.; Jang, J.; Jeong, Y.G.; Lyoo, W.S.; Min, B.G. Superhydrophobic PLA fabrics prepared by UV photo-grafting of hydrophobic silica particles possessing vinyl groups. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 344, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanamsamy, L.; Harun, W.S.W.; Ishak, I.; Romlay, F.R.M.; Kadirgama, K.; Ramasamy, D.; Idris, S.R.A.; Tsumori, F. A comprehensive review on fused deposition modelling of polylactic acid. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 8, 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, E.H.; Erbil, H.Y. Surface Modification of 3D Printed PLA Objects by Fused Deposition Modeling: A Review. Colloids Interfaces 2019, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Kim, M.N. Biodegradation of poly(l-lactide) (PLA) exposed to UV irradiation by a mesophilic bacterium. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Naskar, A.K.; Haynes, D.; Drews, M.J.; Smith, D.W. Synthesis, characterization and surface properties of poly(lactic acid)–perfluoropolyether block copolymers. Polym. Int. 2010, 60, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifehzadeh, R.; Ratner, B.D. Trifluoromethyl-functionalized poly(lactic acid): A fluoropolyester designed for blood contact applications. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 3764–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenn, N.; Follain, N.; Fatyeyeva, K.; Poncin-Epaillard, F.; Labrugère, C.; Marais, S. Impact of hydrophobic plasma treatments on the barrier properties of poly(lactic acid) films. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 5626–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwong, C.; Rachtanapun, P.; Wongchaiya, P.; Auras, R.; Boonyawan, D. Effect of plasma treatment on hydrophobicity and barrier property of polylactic acid. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 2933–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroepfer, M.; Junghans, F.; Voigt, D.; Meyer, M.; Breier, A.; Schulze-Tanzil, G.; Prade, I. Gas-Phase Fluorination on PLA Improves Cell Adhesion and Spreading. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5498–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; Mishina, T.; Namie, M.; Nishimura, F.; Yonezawa, S. Effects of surface fluorination on the dyeing of polycarbonate (PC) resin. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2021, 19, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P.; Simbirtseva, G.V.; Tressaud, A.; Durand, E.; Labrugère, C.; Dubois, M. Comparison of the surface modifications of polymers induced by direct fluorination and rf-plasma using fluorinated gases. J. Fluor. Chem. 2014, 165, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prorokova, N.P.; Istratkin, V.A.; Kumeeva, T.Y.; Vavilova, S.Y.; Kharitonov, A.P.; Bouznik, V.M. Improvement of polypropylene nonwoven fabric antibacterial properties by the direct fluorination. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 44545–44549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriprom, W.; Sangwaranatee, N.; Herman; Chantarasunthon, K.; Teanchai, K.; Chamchoi, N. Characterization and analyzation of the poly (L-lactic acid) (PLA) films. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 14803–14806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paragkumar, N.T.; Edith, D.; Six, J.-L. Surface characteristics of PLA and PLGA films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 253, 2758–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P. Direct fluorination of polymers—From fundamental research to industrial applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2008, 61, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Nishimura, F.; Kim, J.H.; Yonezawa, S. Dyeable Hydrophilic Surface Modification for PTFE Substrates by Surface Fluorination. Membranes 2023, 13, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, E.; Bertoti, I.; Vargha-Butler, E.I. XPS and wettability characterization of modified poly(lactic acid) and poly(lactic/glycolic acid) films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 245, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namie, M.; Kim, J.-H.; Yonezawa, S. Improving the Dyeing of Polypropylene by Surface Fluorination. Colorants 2022, 1, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, P.; Białas, S.; Mucha, M.; Kaczmarek, H. Thermogravimetric and DSC testing of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 573, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.; Botelho, G.; Oliveira, M.; Machado, A.V. Influence of clay organic modifier on the thermal-stability of PLA based nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 88–89, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.S.; Borhan, A. A Volume-Corrected Wenzel Model. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8875–8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.