Abstract

Polyethylene terephthalate-derived fluorescent carbon quantum dots (PET-CQDs) are promising nanomaterials for sensing and biomedical uses, yet their biological interactions after metal doping require careful evaluation. Here, we report an in silico assessment of pristine and dual-site (via graphitic [G] and carbonyl [O]) metal-doped PET-CQDs (Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn) using molecular docking against eight human proteins: HSA (distribution), CYP3A4 (metabolism), hemoglobin (systemic biocompatibility), transferrin (uptake), GST (detoxification), ERα (endocrine regulation), IL-6 (inflammation), and caspase-3 (cytotoxic signaling) together with ADMET profiling and DFT–docking correlation analysis. Docking affinities were compared with controls and ranged from −7.8 to −10.4 kcal·mol−1 across systems, with binding stabilized by π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding and metal–ligand coordination involving residues such as arginine, tyrosine and serine. Importantly, top-performing CQD variants differed by target: PET-CQDs, MgG_PET-CQDs and FeG_PET-CQDs were best for GST; ERα interacted favorably with all doped variants; IL-6 bound best to CaO_PET-CQDs and FeO_PET-CQDs (≈−7.1 kcal·mol−1); HSA favored CaG_PET-CQDs (−10.0 kcal·mol−1) and FeO_PET-CQDs (−9.9 kcal·mol−1); CYP3A4 bound most strongly to pristine PET-CQDs; hemoglobin favored MgG_PET-CQDs (−9.6 kcal·mol−1) and FeO_PET-CQDs (−9.3 kcal·mol−1); transferrin favored FeG_PET-CQDs; caspase-3 showed favored binding overall (pristine −6.8 kcal·mol−1; doped −7.4 to −7.6 kcal·mol−1). ADMET predictions indicated high GI absorption, improved aqueous solubility for some dopants (~18.6 mg·mL−1 for Ca-O/Mg-O), low skin permeability and no mutagenic/carcinogenic flags. Regression analysis showed frontier orbital descriptors (HOMO/LUMO) partially explain selective affinities for ERα and IL-6. These results support a target-guided selection of PET-CQDs for biomedical applications, and they call for experimental validation of selected dopant–target pairs.

1. Introduction

The expanding use of nanomaterials in biomedical and environmental technologies has intensified the need for rigorous assessment of their biocompatibility and safety. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) are particularly attractive due to their strong fluorescence, high surface area, water dispersibility, and ease of functionalization [1]. The synthesis of CQDs from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) waste offers a sustainable, circular-economy–aligned approach that enables cost-effective production of value-added nanomaterials [2]. To improve their physicochemical and functional performance, metal doping of CQDs has been widely explored [3]. Incorporating alkali-earth and transition metals can enhance electronic structure, stability, and adsorption capacity, expanding their potential in drug delivery, biosensing, and related applications [4]. However, such modifications may also influence biological interactions, raising concerns about toxicity or unintended bioactivity. As these engineered nanomaterials progress toward biomedical use, understanding their interactions with biological macromolecules and their pharmacokinetic and toxicological profiles becomes essential.

Evaluating nanomaterial biocompatibility involves assessing their interactions with key human proteins that govern critical physiological processes, including distribution (e.g., human serum albumin, HSA), metabolism (e.g., cytochrome P450 enzymes, CYP3A4), detoxification (e.g., glutathione S-transferase, GST), inflammation (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), hormonal regulation (e.g., estrogen receptor, ERα), and apoptosis (e.g., caspase-3) [5]. These proteins serve as critical biomarkers for understanding nanomaterial behavior in vivo, influencing biodistribution, clearance, and potential toxicity [6]. Computational approaches, such as molecular docking and in silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) analysis, offer powerful tools to predict these interactions and systemic effects with high precision, reducing the reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental studies [7,8].

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive computational assessment of the biocompatibility, safety, and electronic structure of dual-site metal-doped PET-derived carbon quantum dots (PET-CQDs), including Ca-, Mg-, Zn-, and Fe-doped variants. Molecular docking was used to analyze binding affinities and interaction mechanisms with key human proteins (HSA, CYP3A4, hemoglobin, transferrin, GST, ERα, IL-6, and caspase-3). Complementary in silico ADMET modeling evaluated predicted pharmacokinetics, metabolic stability, and toxicity. A DFT–docking correlation analysis further linked electronic properties (HOMO, LUMO, total energy) to protein binding behavior. Together, these results provide insight into how metal doping and frontier orbital characteristics influence molecular recognition and support the rational design of safe, sustainable, and biocompatible PET-based CQDs for biomedical, sensing, and environmental applications.

2. Computational Approach

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of PET-CQDs Structures

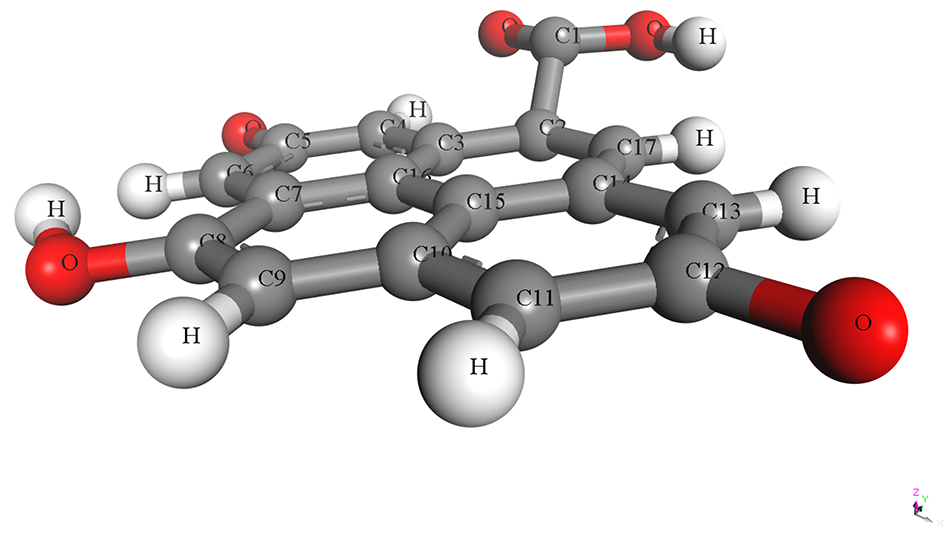

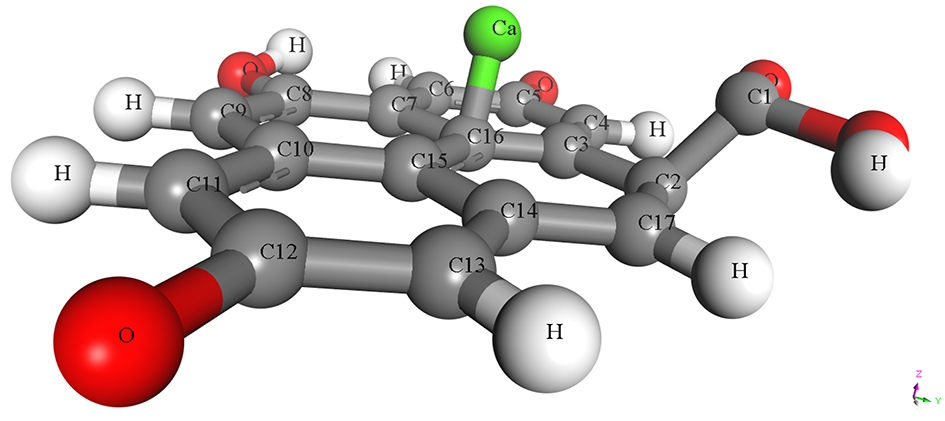

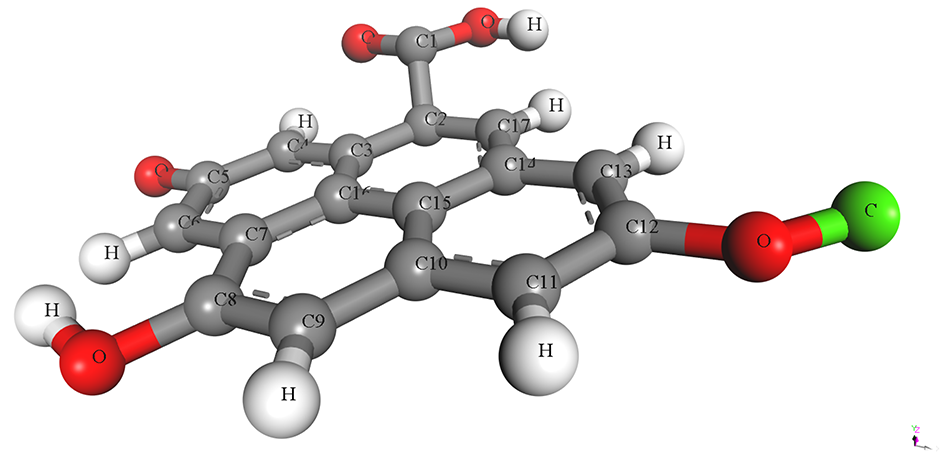

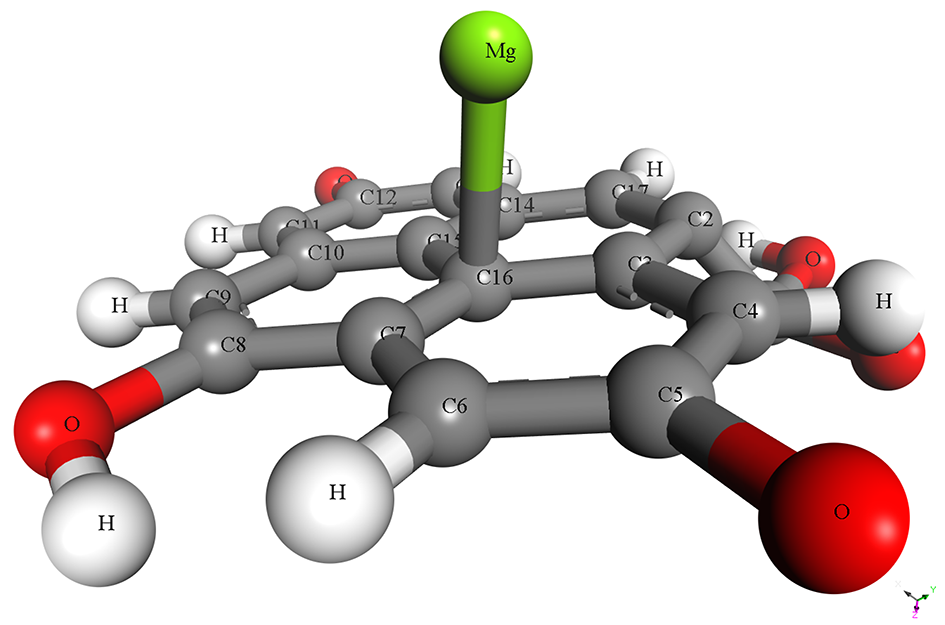

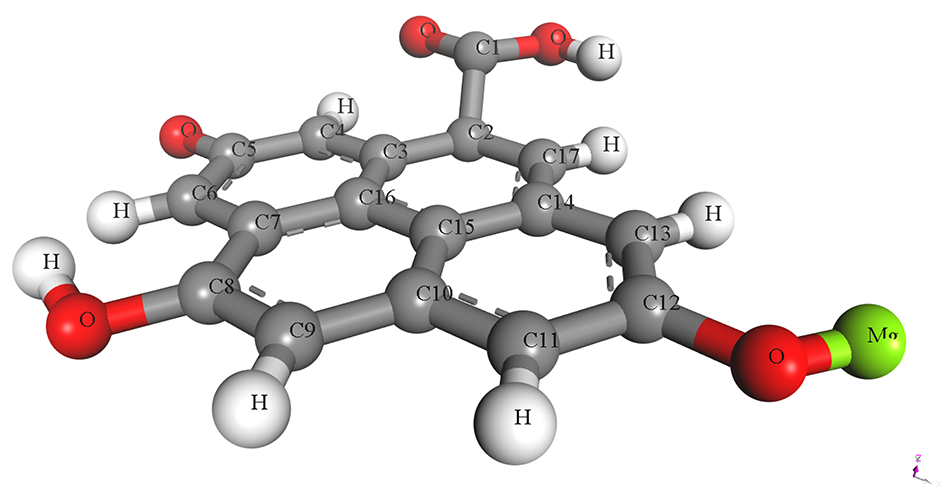

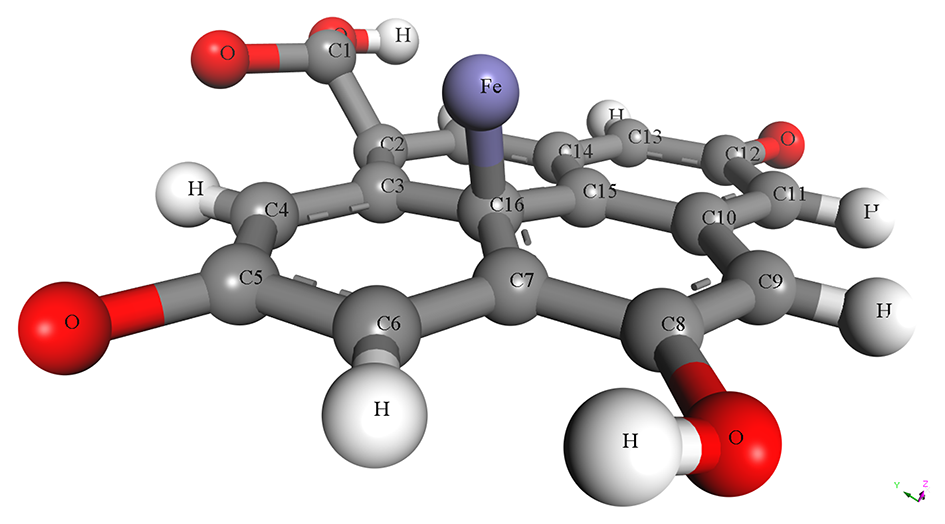

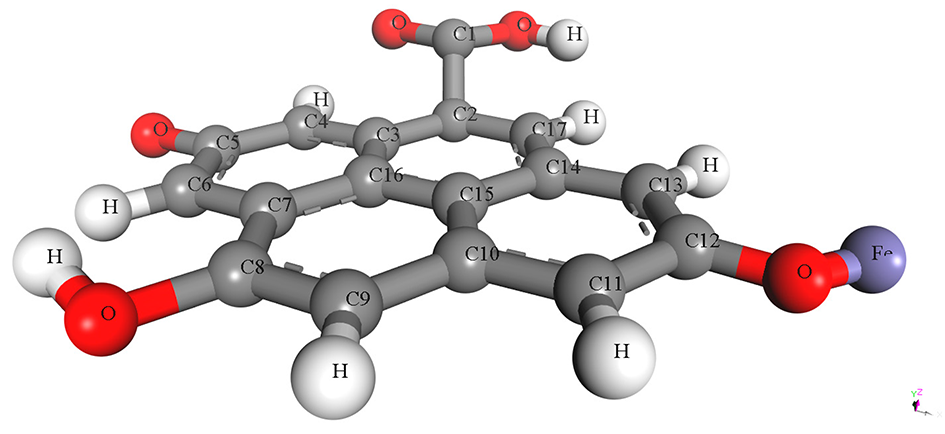

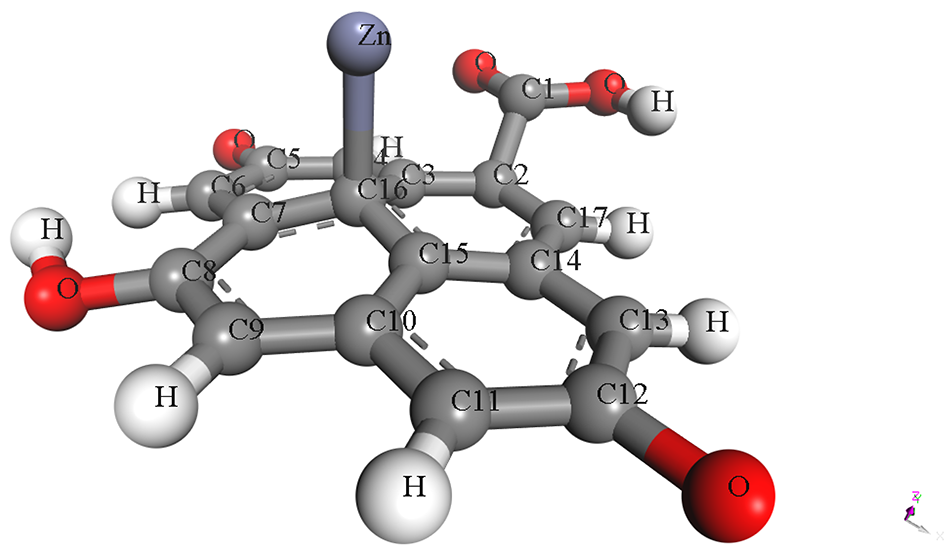

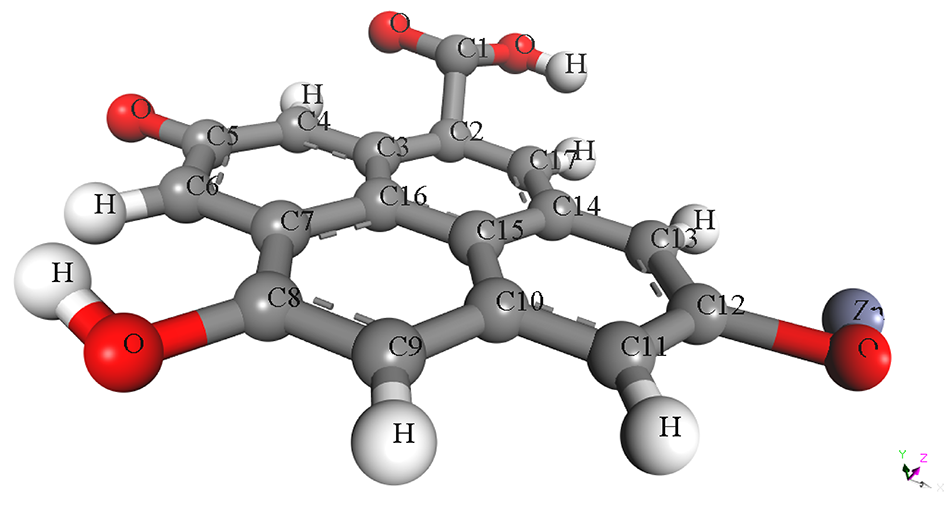

The pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDs structures were drawn using 3D atomistic model in BIOVIA material studio Dassault Systèmes software (v 8.0) based on experimentally synthesized PET-CQDs and ATR-FTIR analysis (Figure S1). The detailed design process and characterization using density functional theory (DFT) has been described and presented in our recent study [4]. The optimized structures of the doped PET-CQDs (C17H8O5) are presented in Table 1, including their configurations and Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) representations. The model was built by incorporating all major functional groups identified experimentally through ATR-FTIR, together with an aromatic carbon core consistent with the UV–Vis and fluorescence characteristics of the PET-CQDs. Although real carbon quantum dots typically range from <10 nm and contain thousands of atoms, fragment-based representations such as ours are widely used in CQD simulations because they capture the reactive surface domains that primarily govern molecular interactions. Furthermore, the simulated structures represent isolated functional fragments of CQDs and therefore do not fully capture nanoparticle-scale steric hindrance or curvature effects. This approach aligns with established CQDs modeling practices and provides a chemically meaningful description of the key functional sites. While we acknowledge that an idealized fragment cannot fully represent the structural heterogeneity of bulk CQDs, it remains appropriate for probing the electronic and interaction properties relevant to this study.

Table 1.

Structure, configuration and SMILES of pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDs.

2.2. Identification and Preparation of Molecular Targets

Eight human proteins relevant to distribution, metabolism, detoxification, cytotoxicity, inflammation, endocrine regulation, and systemic biocompatibility were selected for this study. The chosen protein targets and their respective biological roles are as follows: Human Serum Albumin (HSA; PDB ID: 1AO6) for distribution and plasma transport; Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4; PDB ID: 1TQN or 6MA7) for metabolism; Hemoglobin (PDB ID: 1A3N) for systemic biocompatibility; Transferrin (PDB ID: 3V83) for uptake and bioavailability; Caspase-3 (PDB ID: 5I9B) for apoptotic or cytotoxicity signaling; Glutathione S-transferase (GST; PDB ID: 1GNW) for detoxification pathways; Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα; PDB ID: 3ERT) for endocrine disruption potential; and Interleukin-6 (IL-6; PDB ID: 1ALU) for inflammation response assessment. All protein structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and carefully prepared for docking simulations. The crystallographic water molecules and co-crystallized ligands were removed to eliminate steric interference. Protein structures were then energy minimized using UCSF Chimera 1.14 [9,10] to relieve local strain and optimize geometric conformation. The minimization process involved 300 steepest descent steps at 0.02 Å step size, followed by 10 conjugate gradient steps at 0.02 Å with update intervals of 10 steps. Subsequently, Gasteiger partial charges were assigned using the Dock Prep module within Chimera to ensure accurate electrostatic representation for docking. The resulting minimized and charge-balanced protein models were then saved in PDBQT format for use in subsequent molecular docking analyses. This selection of target proteins provides a comprehensive biological context for evaluating the biocompatibility, ADMET behavior, and potential systemic effects of pristine and metal-doped PET-derived fluorescent carbon quantum dots (PET-CQDs).

2.3. Docking Protocol

The molecular docking of pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDs was carried out against the selected human protein targets to evaluate their binding affinities and potential biocompatibility profiles. Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina (1.1.2) integrated within the PyRx 0.8 platform [9,10]. Each protein target was prepared with a defined grid box centered on its active or allosteric binding pocket to ensure site-specific docking. During the simulations, all compounds were screened, and their poses were ranked based on their binding energies (kcal/mol), which reflect the strength and stability of the ligand–protein interactions. Following the docking runs, the lowest-energy conformations of each PET-CQDs–protein complex were selected for further analysis. The interaction profiles, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, electrostatic interactions, and π–π stacking, were examined using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer (v20.1). This visualization provided detailed insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the affinity and stability of pristine versus metal-doped PET-CQDs within the binding sites of the human enzymes.

2.4. ADMET Properties

The pharmacokinetic features of the PET-CQDs and their metal-doped structures, as well as absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET), were assessed using SwissADME and ADMETSAR server [11]. The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) for their structures was generated using Optical Structure Recognition (OSRA) and used for the ADMET analysis. The SMILES are presented in Table 1.

2.5. Data Analysis

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted between the DFT properties of PET-CQDs against their binding affinities on the different proteins using OriginLab Pro.

3. Results and Discussion

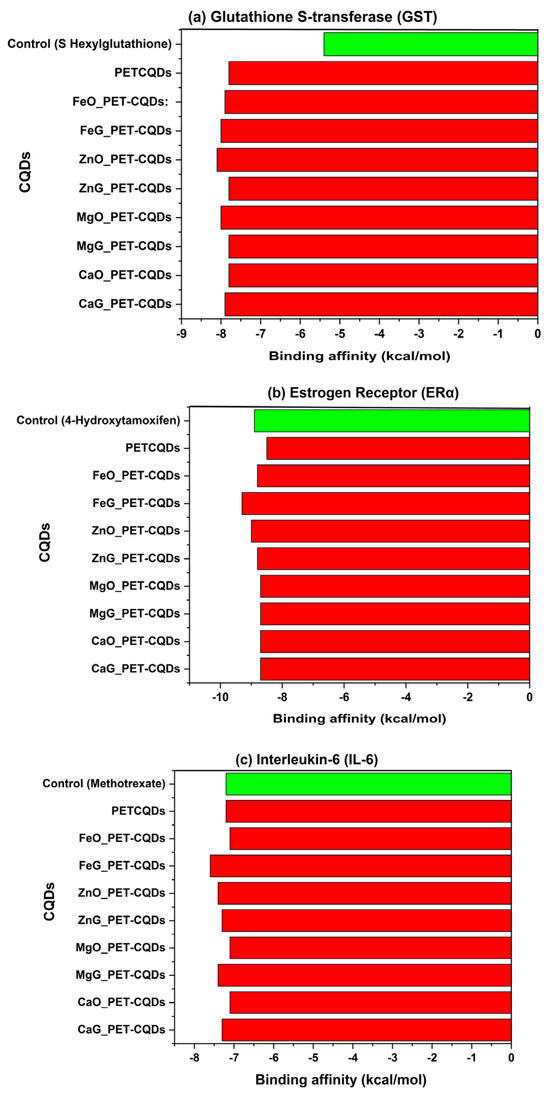

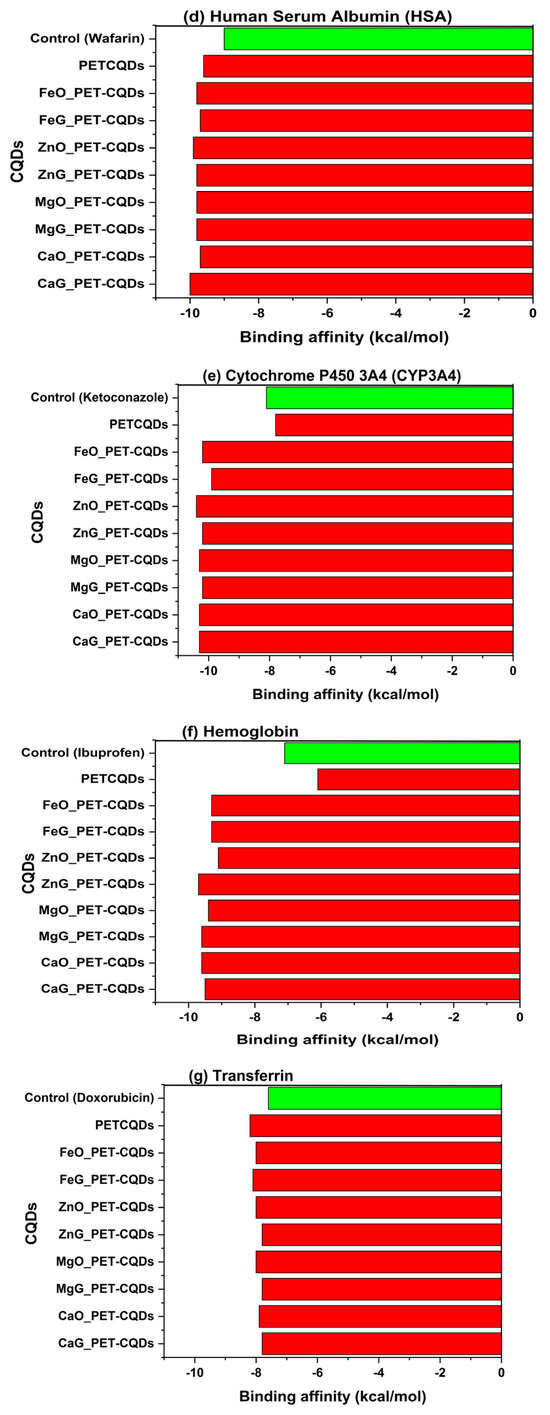

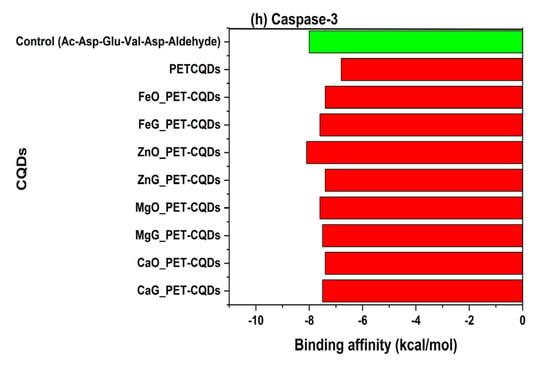

The molecular docking analysis evaluated the interaction between pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDs with several human proteins responsible for distribution, metabolism, detoxification, endocrine response, inflammation, and cytotoxicity. The docking scores or binding affinities in comparison with control compounds are presented in Table S1 and Figure 1a–h. The results generally indicated that some CQDs bind more strongly to the target proteins compared to their respective control ligands, suggesting significant interaction potential. Overall, binding affinities ranged from −7.3 to −10.4 kcal/mol, with slight variations depending on the metal type and doping site.

Figure 1.

The binding affinities of pristine and doped PET-CQDs to different human proteins in comparison with control compounds.

3.1. Detoxification Pathways

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) is a phase II detoxification enzyme that conjugates xenobiotics with glutathione (GSH) for their solubilization and elimination [12]. This is vital for defense against oxidative stress. Inhibition of GST impairs this detoxification pathway, potentially causing increased oxidative damage and toxin accumulation [13]. In this study, the control ligand (GSH) exhibited a binding affinity of −5.4 kcal/mol, whereas PET-CQDs and their metal-doped variants demonstrated significantly stronger interactions, with binding affinities ranging from −7.8 to −8.1 kcal/mol (Figure 1a). Among these, ZnO_PET-CQDs (−8.1 kcal/mol) and FeG_PET-CQDs (−8.0 kcal/mol) showed the most pronounced binding energies, indicating the highest inhibitory potential toward GST, while CaO_PET-CQDs, MgG_PET-CQDs, and pristine PET-CQDs exhibited slightly lower affinities (−7.8 kcal/mol). Mechanistically, these enhanced affinities can be attributed to the ability of the metal-doped CQDs to engage in amide–π, π–alkyl, and π–π stacking interactions involving residues such as Phenylalanine (PHE), Alanine (ALA), Isoleucine (ILE), and Tyrosine (TYR), as well as hydrogen bonding through Lysine (LYS) within the receptor’s ligand-binding domain (Figure S2). The combination of aromatic domains and polar functional groups on the CQD surface supports these interactions by mimicking the electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding stabilization normally provided by GSH during conjugation [14]. These results indicate that metal doping increases CQD–protein affinity through higher surface reactivity and polarity, but excessive or prolonged interaction with GST may transiently compete with natural substrates and influence detoxification pathways [10].

3.2. Endocrine Disruption Potential

The estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that regulates gene expression in response to endogenous estrogens [15]. Because it binds both natural hormones and environmental chemicals, ERα is widely used in in vitro and in silico assays to screen for endocrine-disrupting compounds [16,17]. Altered activation or inhibition of this receptor can disrupt hormonal balance and pose endocrine-related health risks [17]. In this study, the native ligand (4-hydroxytamoxifen) exhibited a binding affinity of −8.9 kcal/mol, serving as the reference standard for ERα interaction. The metal-doped PET-CQDs displayed comparable or slightly stronger affinities, ranging from −8.5 to −9.3 kcal/mol, with FeG_PET-CQDs (−9.3 kcal/mol) and ZnO_PET-CQDs (−9.0 kcal/mol) showing the most pronounced interactions (Figure 1b). The interaction analysis showed that the doped CQDs form π–alkyl contacts with ALA350, MET388, and LEU346, and hydrogen bonds with ARG394 and THR347 within the ERα ligand-binding domain (Figure S3). These interactions stem from the aromatic graphitic core and polar surface groups of the CQDs [4], allowing mixed hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond stabilization in the pocket. Despite these favorable interactions, the results indicate that PET-CQDs and their metal-doped variants are unlikely to activate or inhibit ERα under physiological conditions, suggesting a low risk of endocrine disruption.

3.3. Inflammation Response

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a multifunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a vital role in immune regulation, acute-phase responses, and inflammation signaling pathways [18]. Dysregulation of IL-6 activity is associated with chronic inflammation and various pathological conditions, making it an important biomarker for assessing the immunocompatibility of nanomaterials [19]. In this study, the control ligand exhibited a binding energy of −7.2 kcal/mol, whereas the pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDs showed lower or slightly stronger affinities, ranging from −7.1 to −7.6 kcal/mol. Among these, CaO_PET-CQDs and FeO_PET-CQDs demonstrated the most favorable interactions (−7.1 kcal/mol) (Figure 1c). The narrow variation in binding energies across all variants suggests moderate, nonspecific electrostatic binding rather than a strong or deep-pocket interaction [20], implying limited structural alteration of the cytokine upon complex formation (Figure S4). The ligand–protein interaction analysis (Figure S4) revealed that pristine PET-CQDs primarily interacted with IL-6 via π–cation and π–anion interactions involving ASP133 and ARG77, while metal-doped CQDs engaged predominantly through π–cation interactions with LYS28. Additionally, hydrogen bonding was observed between both pristine and doped CQDs and IL-6 residues GLU79, SER80, SER81, and THR25 (with the latter being unique to doped variants). Pristine PET-CQDs also exhibited π–alkyl and alkyl interactions with PHE78 and LYS28, further stabilizing the complex (Figure S4). These interactions likely result in transient conformational adjustments of IL-6 rather than permanent structural perturbations. The overall moderate binding strength and interaction pattern indicate that both pristine and doped PET-CQDs are unlikely to inhibit or upregulate IL-6 activity, thereby not interfering with normal inflammatory signaling. This observation supports the potential biocompatibility and non-immunogenic nature of PET-CQDs and their doped derivatives.

3.4. Distribution and Plasma Transport

Human Serum Albumin (HSA) is the most abundant carrier protein in human plasma and plays a crucial role in the distribution, transport, and bioavailability of endogenous and exogenous compounds [21]. Its interaction with nanoparticles provides information into their biodistribution and circulation behavior in physiological environments [22]. In this study, the control ligand, warfarin, exhibited a binding affinity of −9.0 kcal/mol, while all CQDs showed slightly stronger binding affinities ranging from −9.6 to −10.0 kcal/mol (Figure 1d). Among these, CaG_PET-CQDs (−10.0 kcal/mol) and FeO_PET-CQDs (−9.9 kcal/mol) displayed the highest affinities (Figure 1d). Critically, the metal-doped PET-CQDs demonstrated stronger binding interactions than the pristine PET-CQDs. This enhancement may be attributed to the increased surface polarity and coordination potential introduced by metal dopants, which promote metal–ligand complexation and electrostatic stabilization within the albumin binding pocket. The docking analysis revealed that both pristine and doped PET-CQDs formed hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions within Sudlow’s site I of HAS [23]. Specifically, π–sigma interactions were observed with VAL152 in both pristine and doped CQDs, while hydrogen bonding occurred through VAL162 in pristine PET-CQDs and SER159 in the doped variants. Interestingly, SER159 exhibited an unfavorable donor–donor interaction in the pristine CQDs, which may explain their relatively lower affinity. Additionally, both pristine and doped PET-CQDs engaged in π–cation interactions with ARG227, while π–alkyl interactions involved LYS156 and PRO224 (in pristine) and ALA154 (in doped variant) (Figure S5). Compared to the control ligand, the CQDs displayed a similar interaction profile, though ARG227 in warfarin formed hydrogen bonds with TRP165, interactions that were absent in the CQDs complexes (Figure S5). These findings suggest that PET-CQDs exhibit strong and stable binding with serum albumin, potentially facilitating their systemic circulation and transport in the bloodstream. However, excessively strong binding could potentially reduce the fraction of free CQDs available for tissue uptake, thereby modulating their pharmacokinetic profile [24].

3.5. Metabolism

Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) is a major phase I metabolic enzyme responsible for the oxidative biotransformation of a wide range of xenobiotics, including drugs and environmental pollutants [25]. Its broad substrate specificity and central role in hepatic metabolism make CYP3A4 an essential biomarker for assessing the metabolic compatibility and safety of new materials [8]. In this study, the native inhibitor ketoconazole exhibited a binding affinity of −8.1 kcal/mol, serving as the reference compound. The pristine PET-CQDs displayed a slightly lower affinity (−7.8 kcal/mol), whereas the metal-doped variants demonstrated markedly stronger binding energies ranging from −9.4 to −10.4 kcal/mol, with MgO_PET-CQDs and ZnO_PET-CQDs showing the highest affinities (−10.4 kcal/mol) (Figure 1e). This enhanced binding suggests that metal doping significantly increases the interaction strength between the CQDs and CYP3A4. Interaction analysis revealed that the binding primarily involves π–cation interactions between the doped metal centers (Fe2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+) of the CQDs and the heme-iron center of CYP3A4, mediated through the ARG106 residue (Figure S6). This specific interaction was absent in the pristine PET-CQDs, indicating that metal incorporation enhances the electronic affinity of the CQDs toward the enzyme’s active domain. These strong metal–heme interactions could suggest potential inhibitory effects on CYP3A4 activity by competing with substrate access to the heme site [26]. However, ADMET predictions (Table 2) indicated no significant inhibition of CYP3A4, implying that the observed interactions likely occur at peripheral or allosteric regions rather than the catalytic center. Consequently, while metal-doped PET-CQDs may transiently associate with the enzyme surface through electrostatic and coordination forces, they are unlikely to disrupt normal metabolic detoxification processes.

Table 2.

ADMET parameters, pharmacokinetic properties, druglike nature of metal-doped PET-CQDs (data collected from SWISSADME and ADMETsar databases).

3.6. Systemic Biocompatibility

Hemoglobin (Hb) serves as a vital indicator of systemic biocompatibility and blood compatibility, as its interactions with foreign materials can influence nanoparticle stability, circulation, and potential interference with oxygen transport [27]. Evaluating hemoglobin binding is therefore crucial in predicting the safe systemic performance of engineered nanomaterials. In this study, the control ligand, ibuprofen, exhibited a moderate binding affinity of −7.1 kcal/mol, while all metal-doped PET-CQDs demonstrated markedly stronger interactions, ranging from −9.3 to −9.6 kcal/mol. The MgG_PET-CQDs (−9.6 kcal/mol) and FeO_PET-CQDs (−9.3 kcal/mol) showed the highest affinities, indicating strong yet stable association with hemoglobin (Figure 1f). In contrast, the pristine PET-CQDs displayed a much lower affinity (−6.1 kcal/mol), even weaker than the control ligand. This suggests that metal incorporation significantly enhances protein–nanomaterial interactions. The interaction profile revealed that metal-doped PET-CQDs form hydrogen bonding with polar amino acid residues SER102 and SER103 within the globin pocket of Hb. Additionally, a network of π–sigma, π–π stacked, and π–alkyl interactions was identified with LEU101, PHE98, and VAL62, respectively (Figure S7). These interactions collectively contribute to the stable binding orientation and structural compatibility of the doped CQDs within the hemoglobin cavity. Mechanistically, such interactions suggests that metal-doped PET-CQDs exhibit strong yet reversible binding, enabling stable dispersion in the bloodstream without significantly disturbing the heme’s oxygen-binding function [27]. The enhanced binding observed for doped variants may be attributed to metal coordination and improved surface polarity, which facilitate favorable electrostatic and π-interactions with the hemoglobin residues. In contrast, the pristine PET-CQDs, which showed the weakest binding, interacted mainly through π–cation and π–anion interactions involving LYS56, GLU27, and GLU23, and π–alkyl contacts with ALA26, resulting in less stable and less specific associations. Generally, these results suggest that metal doping enhances the hemocompatibility of PET-CQDs by promoting reversible, non-toxic coordination and hydrogen-bond interactions with hemoglobin. This implies a potential low risk of hemolytic toxicity and supports their safe systemic circulation potential for biomedical applications.

3.7. Uptake and Bioavailability

Transferrin (Tf) is a glycoprotein responsible for iron transport and cellular uptake via receptor-mediated endocytosis, playing a pivotal role in maintaining metal ion homeostasis [28]. Its interaction with engineered nanomaterials serves as an indicator of cellular internalization efficiency and bioavailability, as nanoparticles that bind transferrin can exploit the transferrin receptor (TfR) pathway for targeted uptake into cells [29,30]. In this study, the control ligand doxorubicin exhibited a binding affinity of −7.6 kcal/mol, while the PET-CQDs and their metal-doped variants demonstrated stronger interactions, with binding energies ranging from −7.8 to −8.4 kcal/mol. Among these, FeG_PET-CQDs (−8.1 kcal/mol) showed the highest affinity for transferrin, followed closely by other doped variants (Figure 1g). The enhanced binding observed in the Fe-doped system is consistent with its surface metal composition, which favors metal–ligand coordination within transferrin’s metal-binding domain.

Detailed protein–ligand interaction analysis (Figure S8) revealed that both pristine and doped PET-CQDs formed coordination and chelation interactions with iron-binding residues, including tyrosine (TYR), cysteine (CYS), asparagine (ARG), and methionine (MET). These residues are critical for Fe3+ stabilization and transport, suggesting that doped CQDs especially FeG_PET-CQDs can mimic ferric ions and interact through similar coordination chemistry. This mechanism may facilitate enhanced transferrin recognition and receptor-mediated cellular internalization, a property advantageous for targeted nanodelivery applications [31,32]. However, the strong binding affinity of Fe-doped CQDs also implies the need for careful optimization, as excessive competition with native ferric ions could potentially disturb iron metabolism or interfere with natural metal transport pathways.

3.8. Apoptotic or Cytotoxicity Signaling

Caspase-3 is a central executioner enzyme in apoptosis, mediating programmed cell death through substrate cleavage [33]. Its activation is a sensitive biomarker of cytotoxicity, making it a key target for evaluating the pro- or anti-apoptotic effects of nanomaterials [34]. In this study, the control ligand Ac-DEVD-CHO exhibited a binding affinity of −8.0 kcal/mol, which was stronger than that of both the pristine PET-CQDsCQDs (−6.8 kcal/mol) and most metal-doped variants (−7.4 to −7.6 kcal/mol). Specifically, ZnO_PET-CQDs demonstrated the highest binding affinity among the doped forms (−8.1 kcal/mol) (Figure 1h). These relatively moderate binding energies indicate weak to transient interactions between the CQDs and the active cysteine site of caspase-3. Interaction analysis (Figure S9) revealed that binding primarily occurred through π–donor hydrogen bonding interactions, suggesting limited engagement with the catalytic residues of the enzyme. This weak affinity implies that both pristine and metal-doped PET-CQDsCQDs are unlikely to induce or inhibit caspase-3 activation, thereby posing minimal risk of apoptosis induction. The absence of strong or covalent interactions with the catalytic cysteine pocket supports the notion that the CQDs act as biologically inert entities toward apoptotic signaling pathways. This finding aligns with the ADMET predictions (Table 2), which showed low cytotoxic potential and favorable biocompatibility profiles across all CQD variants. Collectively, these results confirm that metal-doped PET-CQDs maintain structural and biochemical safety without triggering apoptotic or cytotoxic responses in human systems.

3.9. Relationship Between Quantum Chemical Descriptors of PET-CQDs and Their Binding Affinities

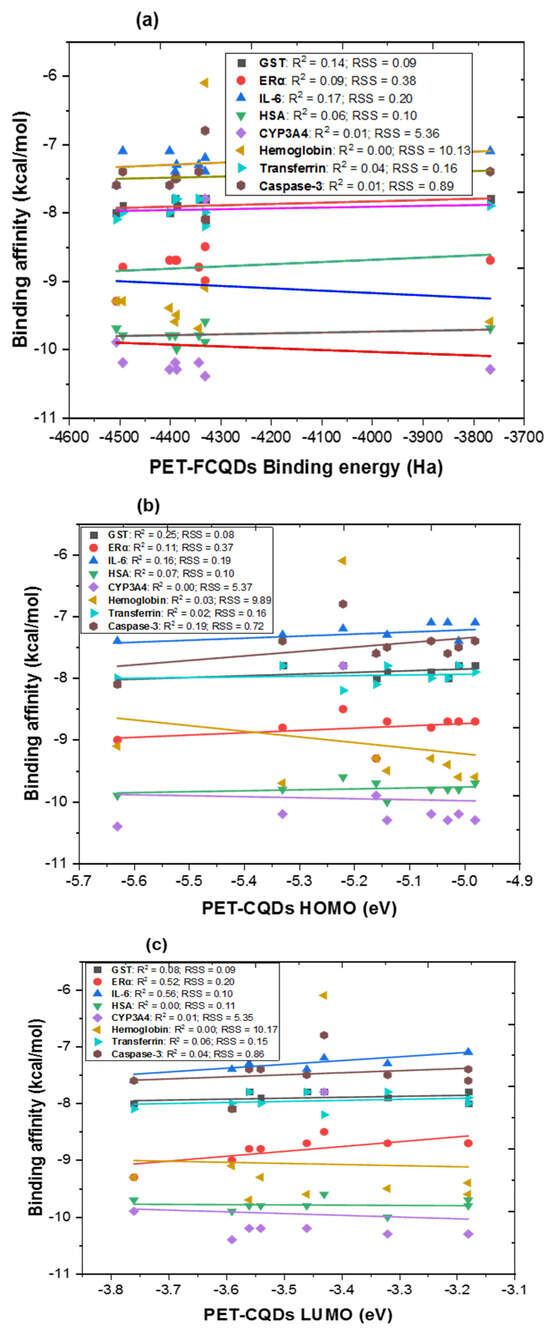

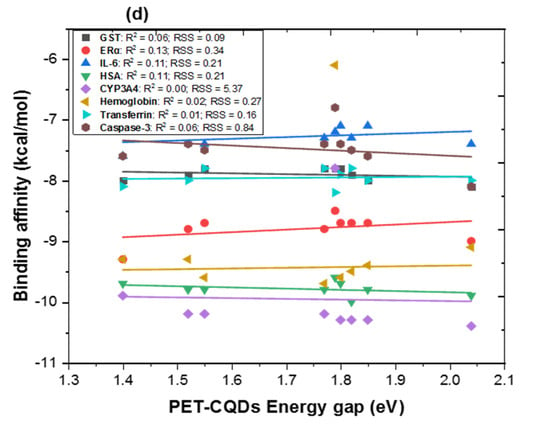

Figure 2 presents the multiple linear regression analysis linking key quantum chemical descriptors of PET-CQDs (Table S2), namely binding energy, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and the energy gap (ΔE), with their corresponding docking-derived binding affinities toward selected human proteins. These DFT parameters are critical indicators of molecular stability and reactivity [2]. Specifically, binding energy reflects overall molecular stability; HOMO represents the electron-donating potential; LUMO indicates electron-accepting ability; and the energy gap (ΔE) defines the molecule’s overall chemical reactivity and polarizability [8]. By correlating these descriptors with protein–ligand binding affinities, the electronic features governing CQDs–protein interactions can be better understood.

Figure 2.

Multiple linear regression between DFT results of PET-CQDs (a) binding energy, (b) highest occupied molecular orbital [HOMO] (c) lowest unoccupied molecular orbital [LUMO] and (d) energy gap against binding affinities for the different proteins. R2 = coefficient of determination; RSS = residual sum of squares.

As shown in Figure 2a, the relationship between DFT-calculated binding energy and protein binding affinity revealed generally weak positive correlations (R2 < 0.2), indicating that total binding energy alone does not strongly predict protein interaction strength. Among all proteins, GST (R2 = 0.14) and IL-6 (R2 = 0.17) exhibited the most noticeable dependence, suggesting that detoxification and inflammatory proteins are slightly more sensitive to changes in the overall stability of the CQD structures. In Figure 2b, a moderately stronger relationship was observed between HOMO energy and binding affinity, particularly for GST (R2 = 0.25), ERα (R2 = 0.11), IL-6 (R2 = 0.15), and Caspase-3 (R2 = 0.19). This implies that electron-donating ability, reflected by higher HOMO energy, may facilitate molecular recognition, especially in proteins containing polar or hydrophobic binding pockets capable of engaging in π–π or electrostatic interactions. For LUMO energy (Figure 2c), relatively strong correlations were observed for ERα (R2 = 0.52) and IL-6 (R2 = 0.56), indicating that electron-accepting capacity plays a notable role in the interaction of CQDs with receptor proteins involved in endocrine and inflammatory signaling. This suggests that frontier orbital alignment between CQDs and target proteins could influence specific binding modes, particularly where charge–transfer interactions occur. Similarly, the energy gap correlation (Figure 2d) was generally weak (R2 < 0.25), reflecting that global reactivity alone does not dictate binding. These results highlight that while dopant-induced electronic modifications can alter the frontier orbital characteristics, protein–CQD binding is primarily driven by localized electronic density, surface charge distribution, and polar functionality rather than overall reactivity. Collectively, these findings reveal that HOMO and LUMO energies, rather than total binding energy alone, are the most influential electronic descriptors governing PET-CQD interactions with biological macromolecules. The stronger correlations observed for ERα and IL-6 suggest that the electronic frontier orbitals, particularly the ability of CQDs to donate (HOMO) or accept (LUMO) electrons play a central role in modulating receptor binding and recognition. Metal doping appears to enhance electron delocalization and orbital overlap, thereby improving selective affinity toward proteins involved in endocrine and inflammatory regulation.

3.10. ADMET Properties of Metal-Doped PET-CQDs

The ADMET properties of the PET-CQDs and metal-doped PET-CQDs are summarized in Table 2. The lipophilicity of a compound, often expressed as the logarithm of its partition coefficient (Log P), is a key determinant of membrane permeability and bioavailability. It reflects a molecule’s affinity for lipid environments and plays a critical role in its ability to permeate biological membranes, including the intestinal epithelium [35]. The pristine PET-CQDs exhibited a consensus Log Po/w value of 1.13, which falls within the optimal range for oral drug candidates [36]. Upon metal doping, a slight decrease in Log P values was observed across all variants (ranging from 0.38 to 0.64), suggesting reduced lipophilicity. This trend implies enhanced hydrophilicity and lower membrane affinity, which could reduce bioaccumulation potential [37]. Among the doped CQDs, Zn-G and Fe-G variants maintained relatively higher lipophilicity (Log P ~ 0.64 and 0.63, respectively), indicating they may possess better membrane permeability compared to other metal-doped forms.

In terms of aqueous solubility, all variants were classified as “soluble.” Metal doping enhanced the solubility of PET-CQDs (Table 2). The pristine PET-CQDs exhibited a Log S of −3.60, corresponding to a solubility of 0.0734 mg/mL, whereas doped CQDs, particularly Ca-O and Mg-O PET-CQDs, demonstrated significantly higher solubility, reaching up to ~18.6 mg/mL. This dramatic increase highlights the role of metal doping in improving the dispersibility of CQDs in biological fluids, thereby enhancing their potential for systemic circulation or intravenous applications.

From a pharmacokinetic perspective, all CQDs demonstrated high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, indicative of strong oral bioavailability. Skin permeability values (Log Kp) remained low across all compounds (approximately −8 cm/s), aligning with low transdermal absorption potential. All variants were identified as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrates, which suggests they may be subject to efflux mechanisms in the intestinal or blood–brain barrier, potentially affecting overall absorption and distribution. Nonetheless, Caco-2 permeability predictions were favorable, supporting the possibility of efficient intestinal uptake and systemic exposure.

With respect to drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry filters, all metal-doped CQDs passed Lipinski, Veber, Egan, and Muegge rules, reinforcing their potential as drug-like and bioactive molecules. The bioavailability scores remained consistent across variants, in the range of 0.55–0.56, indicating moderate systemic availability. Importantly, no PAINS (Pan Assay Interference Structures) alerts were detected, which is favorable for drug development. However, Brenk alerts were triggered in some doped variants, particularly those involving beta-keto anhydride, charged oxygen, or heavy metal-related groups, which could indicate chemical instability or metabolic liabilities. Additionally, synthetic accessibility scores increased slightly following doping (from ~3.3 to ~4.9), implying a moderate increase in synthetic complexity, though still within a manageable range for experimental synthesis.

The absorption and distribution profile were further supported by positive predictions for human intestinal absorption (HIA) and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, suggesting that CQDs can reach both systemic and central nervous system compartments. All compounds showed positive Caco-2 permeability as well. Moreover, subcellular localization predictions indicated a tendency for mitochondrial accumulation, which may be beneficial in targeting mitochondrial pathways or, conversely, could raise concerns for mitochondrial toxicity, depending on concentration and exposure duration.

In terms of metabolism, none of the PET-CQDs or their metal-doped variants were predicted to be substrates for major cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2C9, CYP3A4). Furthermore, they were not predicted to inhibit CYP450 isoforms, including CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2C19, which is important in avoiding potential drug–drug interactions. CYP inhibitory promiscuity was also low, indicating low likelihood of metabolic interference, a critical factor in ensuring metabolic safety and biocompatibility.

Regarding excretion, predictions showed variations in plasma (CLp) and renal (CLr) clearance, with most doped CQDs, particularly Fe- and Zn-doped variants, showing evidence of active clearance pathways. The half-life (T1/2) for all variants was relatively short (ranging from 0.01 to 0.09), indicating rapid systemic elimination, which may reduce the risk of bioaccumulation but also limit therapeutic exposure windows. Likewise, the Mean Residence Time (MRT) remained short across all compounds, consistent with fast clearance dynamics.

The toxicity profiles of all PET-CQDs and their doped analogues were generally favorable. They were predicted to be non-mutagenic (negative Ames test) and non-carcinogenic, which supports their biosafety for potential biomedical use. No significant cardiac toxicity was identified, as hERG inhibition was weak. All compounds were categorized in acute oral toxicity Class III, with LD50 values ranging from 500 to 5000 mg/kg, suggesting low acute toxicity in line with other nanomaterials. However, biodegradability varied depending on the doping site. While pristine PET-CQDs and all graphitic-site doped variants were predicted to be readily biodegradable, most carbonyl-site doped variants (Ca-O, Mg-O, Fe-O, Zn-O) were not readily biodegradable.

4. Conclusions and Recommendation

This study provides a comprehensive computational assessment of the biocompatibility and protein interaction behavior of pristine and metal-doped polyethylene terephthalate–derived fluorescent carbon quantum dots (PET-CQDs). By integrating molecular docking, ADMET prediction, and DFT–docking correlation analysis, the findings reveal that metal doping significantly influences biological interactions in a protein-specific manner rather than producing a universally optimal variant.

Overall, metal incorporation enhanced the binding affinities of PET-CQDs (−7.8 to −10.4 kcal/mol) through synergistic π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and metal–ligand coordination, primarily involving amino acid residues such as arginine (ARG), tyrosine (TYR), and serine (SER). However, the most favorable dopant varied across biological targets:

- GST interacted best with PET-CQDs, CaO_PET-CQDs, MgG_PET-CQDs, and FeG_PET-CQDs.

- ERα exhibited strong binding to all doped variants, indicating potential endocrine receptor affinity.

- IL-6 binding was most favorable for CaO_PET-CQDs and FeO_PET-CQDs.

- HSA showed the highest affinity for CaG_PET-CQDs and FeO_PET-CQDs.

- CYP3A4 favored pristine PET-CQDs, suggesting minimal interference with metabolic detoxification.

- Hemoglobin bound strongly to MgG_PET-CQDs (−9.6 kcal/mol) and FeO_PET-CQDs.

- Transferrin showed a preference for FeG_PET-CQDs, while caspase-3 displayed only weak, transient interactions across all variants.

The ADMET analysis demonstrated that the PET-CQDs possess favorable biocompatibility and safety characteristics, including high gastrointestinal absorption, enhanced aqueous solubility (reaching ~18.6 mg/mL for Ca–O and Mg–O doped variants), low skin permeability, and no mutagenic or carcinogenic alerts. Notably, none of the CQDs inhibited the major CYP450 isoforms, indicating a low likelihood of metabolic disruption.

Regression modeling between DFT-derived descriptors and docking affinities further showed that the HOMO and LUMO energies are critical predictors of selective protein binding—particularly for ERα and IL-6—highlighting the central role of electronic structure in governing biological reactivity. Collectively, these findings indicate that controlled metal doping of PET-CQDs enables tunable biocompatibility and target specificity, allowing rational selection of dopant–site configurations aligned with intended biomedical functions. For example, CaG-PET-CQDs and FeO-PET-CQDs appear more suitable for albumin-mediated plasma transport, FeG-PET-CQDs for transferrin-driven uptake, and MgG-PET-CQDs for blood-compatible or systemic formulations.

In summary, target-guided dopant optimization provides a strategic framework for designing PET-derived CQDs with balanced biological performance, safety, and functional selectivity. Future experimental work—including protein-binding assays, cytotoxicity testing, and metabolic stability evaluations—is essential to validate these computational predictions and establish their potential for biosensing, drug delivery, and broader biomedical applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/physchem5040055/s1, Figure S1: (a) Green one-step synthesis of PET-CQDs and (b) ATR-FTIR characterization; Figure S2: Representative 2D protein–ligand interactions of GST with control and PET-CQD variants. Interactions are shown for the (a) untreated ligand (Control), (b) undoped PET-CQDs, (c) Zn-doped PET-CQDs (ZnG), and (d) Ca-doped PET-CQDs (CaO). Hydrogen bonds (green), hydrophobic contacts (pink), π–π interactions (purple), and other relevant interactions are highlighted. Key amino acid residues involved in binding are labeled, illustrating how doping influences the interaction profile of PET-CQDs with GST; (b) Figure S3: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction for ERα with control and PET-CQD variant. The diagrams highlight Conventional Hydrogen Bonds (green dashed lines) and π–Alkyl interactions (pink dashed lines) between ERα residues and the bound ligand. (a) Control and (b) CaG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S4: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction profiles showing the binding of ligands within the IL-6 binding site. The diagrams illustrate the interaction differences between: (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-CQDs, (c) MgG_PET-CQDs variant, and (d) ZnG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S5: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams showing the binding mode of ligands within the Human Serum Albumin (HSA) binding site. The diagrams compare the interaction profiles of (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-FCQDs variant, and (c) CaG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S6: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams illustrating the binding modes within the CYP3A4 active site. The figure compares the interaction profiles of (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-FCQDs variant, and (c) MgG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S7: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams illustrating the binding modes within the Haemoglobin binding pocket. The figure compares the interaction profiles of (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-FCQDs variant, and (c) MgG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S8: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction for Transferrin. The figure compares the interaction profiles of (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-FCQDs variant, and (c) MgG_PET-CQDs variant; Figure S9: Representative 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams illustrating the binding modes within the Caspase 3 active site. The figure compares the distinct interaction profiles of (a) Control ligand, (b) PET-CQDs variant, and (c) ZnG:PET-CQDs variant. Table S1: Binding affinities for the different PET-CQDs against different proteins; Table S2: Quantum chemical properties for the different PET-CQDs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.E.; methodology, C.E.E. and T.O.M.; software, C.E.E. and T.O.M.; validation, C.E.E. and Q.W.; formal analysis, C.E.E.; investigation, C.E.E. and T.O.M.; resources, C.E.E., Q.W. and M.S.; data curation, C.E.E.; writing—original draft preparation, C.E.E. and I.S.E.; writing—review and editing, C.E.E., Q.W., M.S. and I.S.E.; visualization, C.E.E.; supervision, C.E.E. and Q.W.; project administration, C.E.E. and Q.W.; funding acquisition, C.E.E. and Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Award number: 24KF0131) through a Special Research Fellowship application, and partial funding was provided by the Special Funds for Innovative Area Research and Basic Research (Category B) (No. 22H03747, FY2022–FY2024, No. 24K20941, FY2024–FY2026 and No. 25K03267, FY2025–FY2028) of Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Sharma, A.K.; Kuamri, N.; Chauhan, P.; Thakur, S.; Kumar, S.; Shandilya, M. Comprehensive Insights into Carbon Quantum Dots: Synthesis Strategies and Multidomain Applications. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Suzuki, M.; Masuda, G.; Nakajima, D.; Lu, S. Green One-Step Synthesis and Characterization of Fluorescent Carbon Quantum Dots from PET Waste as a Dual-Mode Sensing Probe for Pd(II), Ciprofloxacin, and Fluoxetine via Fluorescence Quenching and Enhancement Mechanisms. Surfaces 2025, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, J.; Lan, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, K.; Song, X.; Zeng, L. Metal Ions-Doped Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 1333101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Wang, Q.; Tochukwu, O.M.; Miho, S.; Weiqian, W.; Daisuke, N. Dual-site doping of PET-derived carbon quantum dots with alkali-earth and transition metals for adsorption of PFOS, ibuprofen, sucralose, and decabromodiphenyl oxide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 372, 133418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, T.R.; Raj, A.; Tseng, T.H.; Xiao, H.; Nguyen, R.; Mohammed, F.S.; Halder, S.; Xu, M.; Wu, M.J.; Bao, S.; et al. Biocompatibility of nanomaterials and their immunological properties. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 042005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Chung, C.; Eiken, M.K.; Baumgartner, K.V.; Fahy, K.M.; Leung, K.Q.; Bouzos, E.; Asuri, P.; Wheeler, K.E.; Riley, K.R. Silver nanoparticle interactions with glycated and non-glycated human serum albumin mediate toxicity. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1081753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Nandi, A.; Simnani, F.Z.; Singh, D.; Sinha, A.; Naser, S.S.; Sahoo, J.; Lenka, S.S.; Panda, P.K.; Dutt, A.; et al. In silico nanotoxicology: The computational biology state of art for nanomaterial safety assessments. Mater. Des. 2023, 235, 112452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Maduka, T.; Wang, Q.; Islam, M.R. In Silico Screening of Active Compounds in Garri for the Inhibition of Key Enzymes Linked to Diabetes Mellitus. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1597–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Wang, Q. Sex toys for pleasure, but there are risks in silico toxicity studies of leached micronanoplastics and phthalates. Hyg. Environ. Health Adv. 2024, 10, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Duru, C.E.; Ovuoraye, P.E.; Wang, Q. Evaluation of nanoplastics toxicity to the human placenta in systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 446, 130600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Wang, Q. Box–Behnken design and machine learning optimization of PET fluorescent carbon quantum dots for removing fluoxetine and ciprofloxacin with molecular dynamics and docking studies as potential antidepressant and antibiotic. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari, A.M.A.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Z.W.; Zhang, J.; Tew, K.D.; Townsend, D.M. The Multifaceted Role of Glutathione S-Transferases in Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnasser, S.M. The role of glutathione S-transferases in human disease pathogenesis and their current inhibitors. Genes Dis. 2024, 12, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Viçosa, D.; Teixeira, V.H.; Santos, H.A.; Machuqueiro, M. Conformational Study of GSH and GSSG Using Constant-pH Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 7507–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripps, S.M.; Marshall, S.A.; Mattiske, D.M.; Ingham, R.Y.; Pask, A.J. Estrogenic endocrine disruptor exposure directly impacts erectile function. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanle, E.K.; Xu, W. Endocrine disrupting chemicals targeting estrogen receptor signaling: Identification and mechanisms of action. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribay, K.; Kim, M.T.; Wang, W.; Pinolini, D.; Zhu, H. Predictive Modeling of Estrogen Receptor Binding Agents Using Advanced Cheminformatics Tools and Massive Public Data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, M.; Zohora, F.T.; Anka, A.U.; Ali, K.; Maleknia, S.; Saffarioun, M.; Azizi, G. Interleukin-6 cytokine: An overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boraschi, D.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Italiani, P. In Vitro and In Vivo Models to Assess the Immune-Related Effects of Nanomaterials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stank, A.; Kokh, D.B.; Fuller, J.C.; Wade, R.C. Protein Binding Pocket Dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, G.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Marino, M.; Fasano, M.; Ascenzi, P. Human serum albumin: From bench to bedside. Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; He, Q. The interaction of nanoparticles with plasma proteins and the consequent influence on nanoparticles behavior. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Wu, X. Review: Modifications of human serum albumin and their binding effect. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1862–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, T.; Trieu, V.; Myers, S.; Qazi, S.; Saund, S.; Lee, C. Sub-15 nm Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Emerging Frontiers and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevrioukova, I.F.; Poulos, T.L. Structural and mechanistic insights into the interaction of cytochrome P4503A4 with bromoergocryptine, a type I ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 3510–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, Y.; Yoneda, S.; Yasuda, K.; Kurita, N.; Kawagoe, F.; Mikami, B.; Takita, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Ikushiro, S.; Takimoto-Kamimura, M.; et al. Cooperative inhibition in cytochrome P450 between a substrate and an apparent noncompetitive inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Satue, C.; Jansman, M.M.T.; Thulstrup, P.W.; Hosta-Rigau, L. Optimization of Hemoglobin Encapsulation within PLGA Nanoparticles and Their Investigation as Potential Oxygen Carriers. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Qian, C.; Wang, X.; Qian, Z.M. Transferrin receptors. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.R.; Bernabeu, E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Patel, S.; Kozman, M.; Chiappetta, D.A.; Holler, E.; Ljubimova, J.Y.; Helguera, G.; Penichet, M.L. The transferrin receptor and the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents against cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Lei, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Yan, F.; Cai, L.; Tian, J.; et al. Oral delivery of teriparatide utilizing biocompatible transferrin-engineered MOF nanoparticles for osteoporosis therapy. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, M.J.; Loureiro, J.A.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Pereira, M.C. Transferrin Receptor-Targeted Nanocarriers: Overcoming Barriers to Treat Glioblastoma. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Bing, T.; Liu, X.; Shangguan, D. Transferrin receptor-mediated internalization and intracellular fate of conjugates of a DNA aptamer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, R.; Tantry, I.Q.; Ahmad, W.; Siddiqui, S.; Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Moinuddin; Hassan, M.I.; Habib, S.; et al. Apoptosis: A Comprehensive Overview of Signaling Pathways, Morphological Changes, and Physiological Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2024, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Kwon, S.H.; Zhou, X.; Fuller, C.; Wang, X.; Vadgama, J.; Wu, Y. Overcoming Challenges in Small-Molecule Drug Bioavailability: A Review of Key Factors and Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhra, M.; Qasem, R.J.; Aldossari, F.; Saleem, R.; Aljada, A. A Comprehensive Exploration of Caspase Detection Methods: From Classical Approaches to Cutting-Edge Innovations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.A.; Berger, B.K.; Kogelman, K. 10.18—Chromatographic Separations and Analysis: Supercritical Fluid Chromatography for Chiral Analysis and Semi-Preparative Purification. In Comprehensive Chirality, 2nd ed.; Cossy, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 355–393. [Google Scholar]

- Vidaurre, R.; Bramke, I.; Puhlmann, N.; Owen, S.F.; Angst, D.; Moermond, C.; Venhuis, B.; Lombardo, A.; Kümmerer, K.; Sikanen, T.; et al. Design of greener drugs: Aligning parameters in pharmaceutical R&D and drivers for environmental impact. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).