Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods as High-Capacity Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Co3O4 Yolk-Shell Microspheres

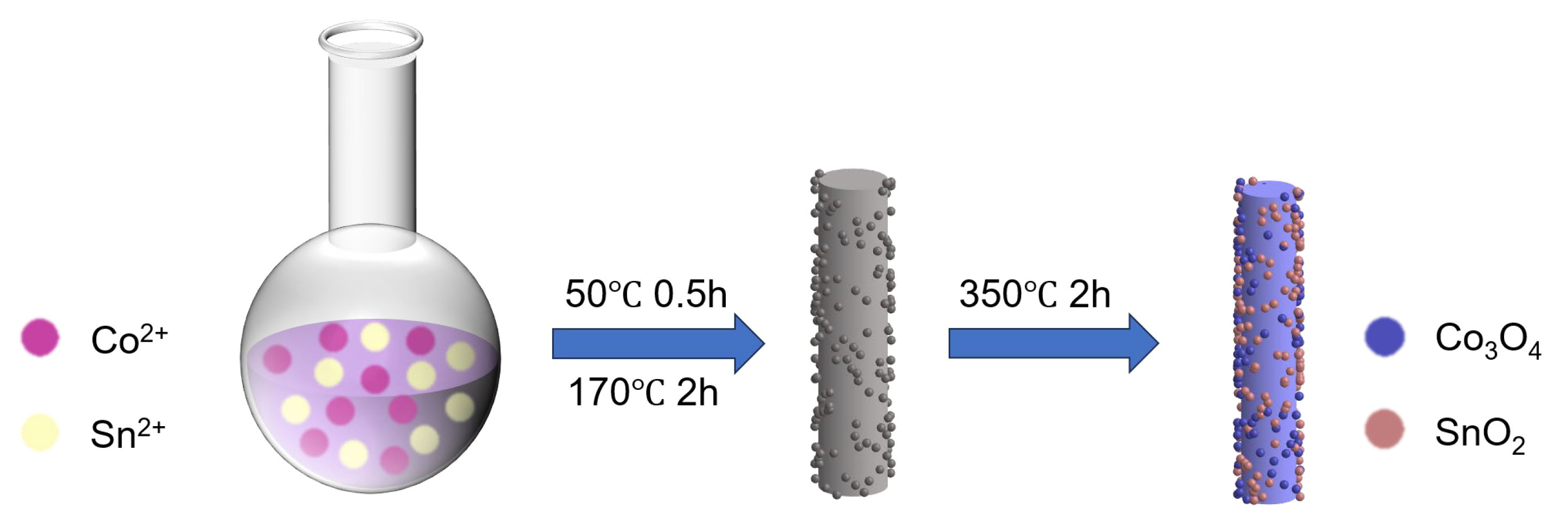

2.2. Preparation of Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods

2.3. Material Characterization Methods

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results

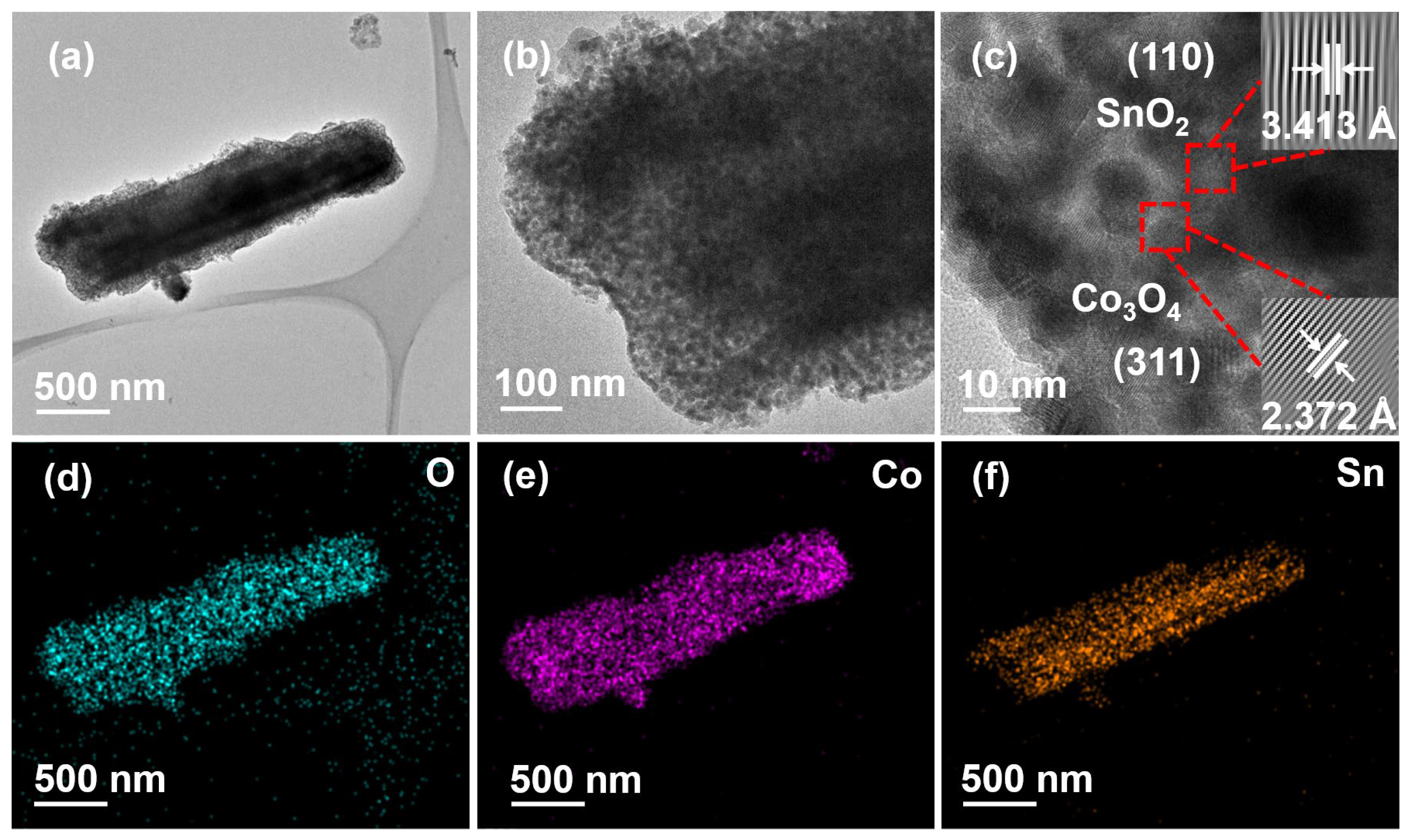

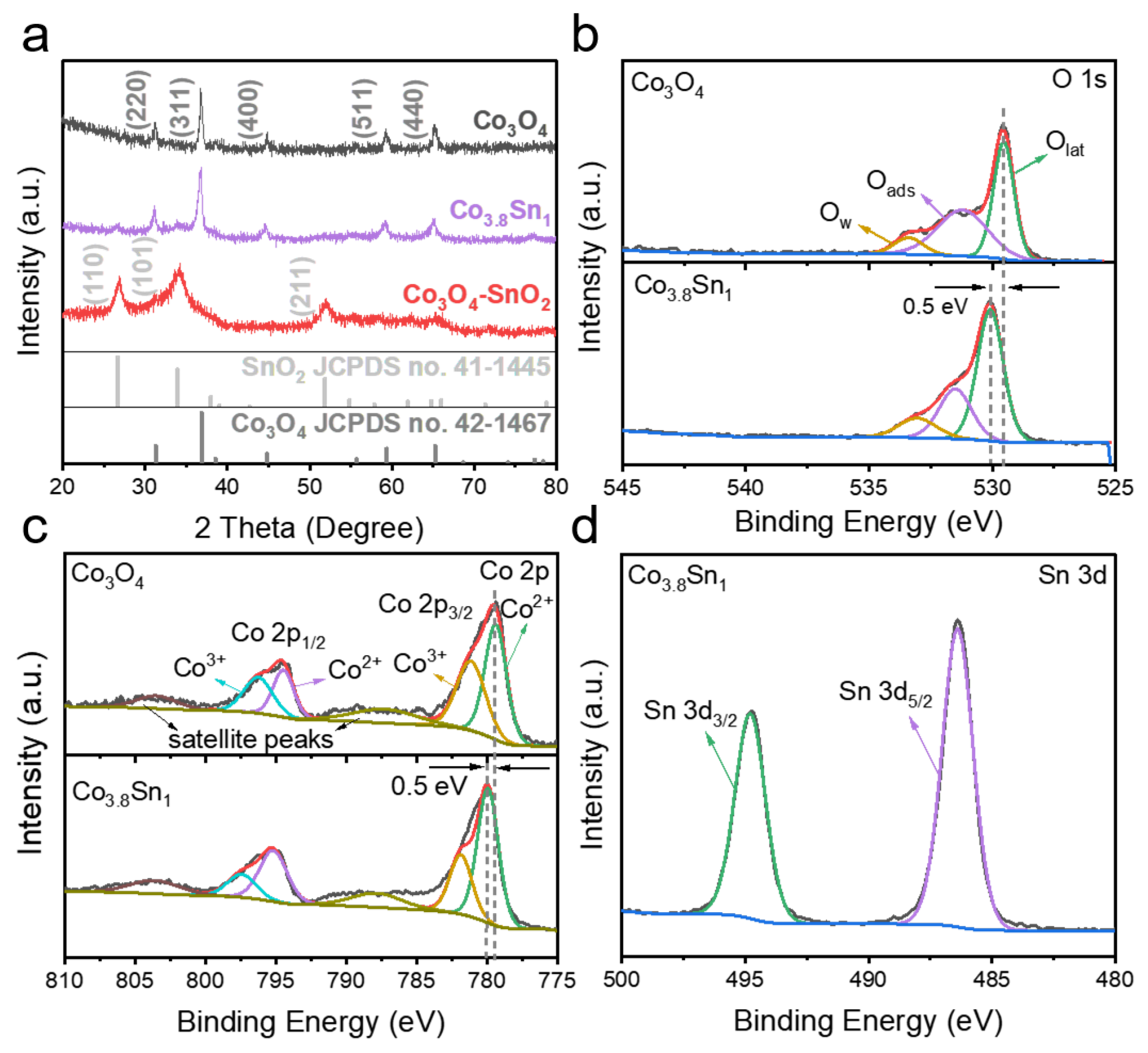

3.1. Structural Characterization and Phase Analysis of Materials

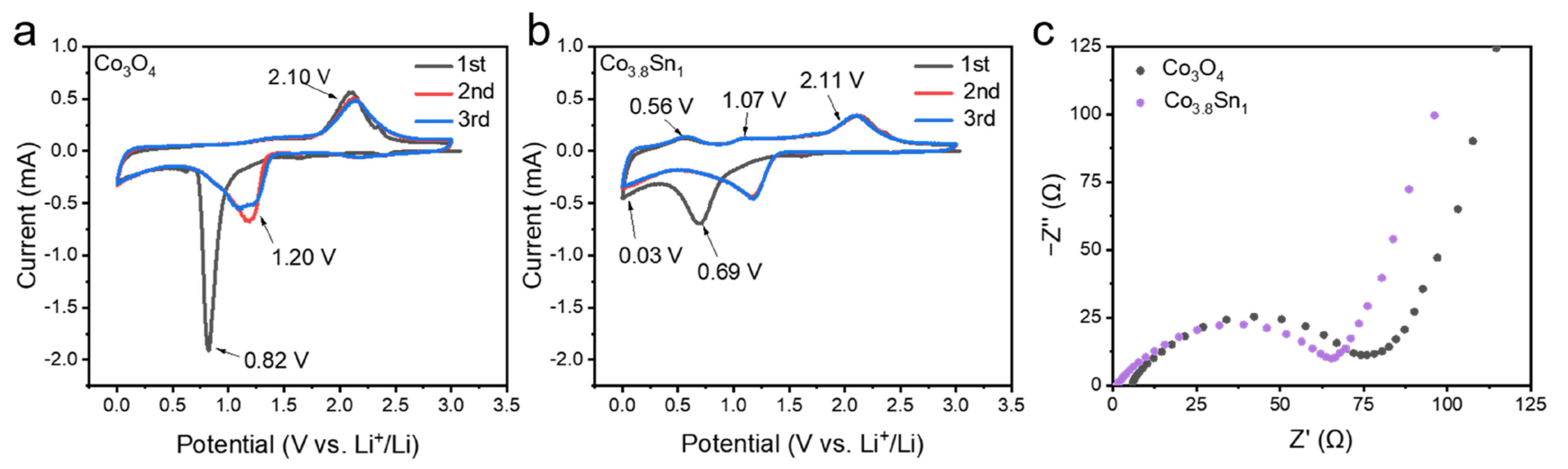

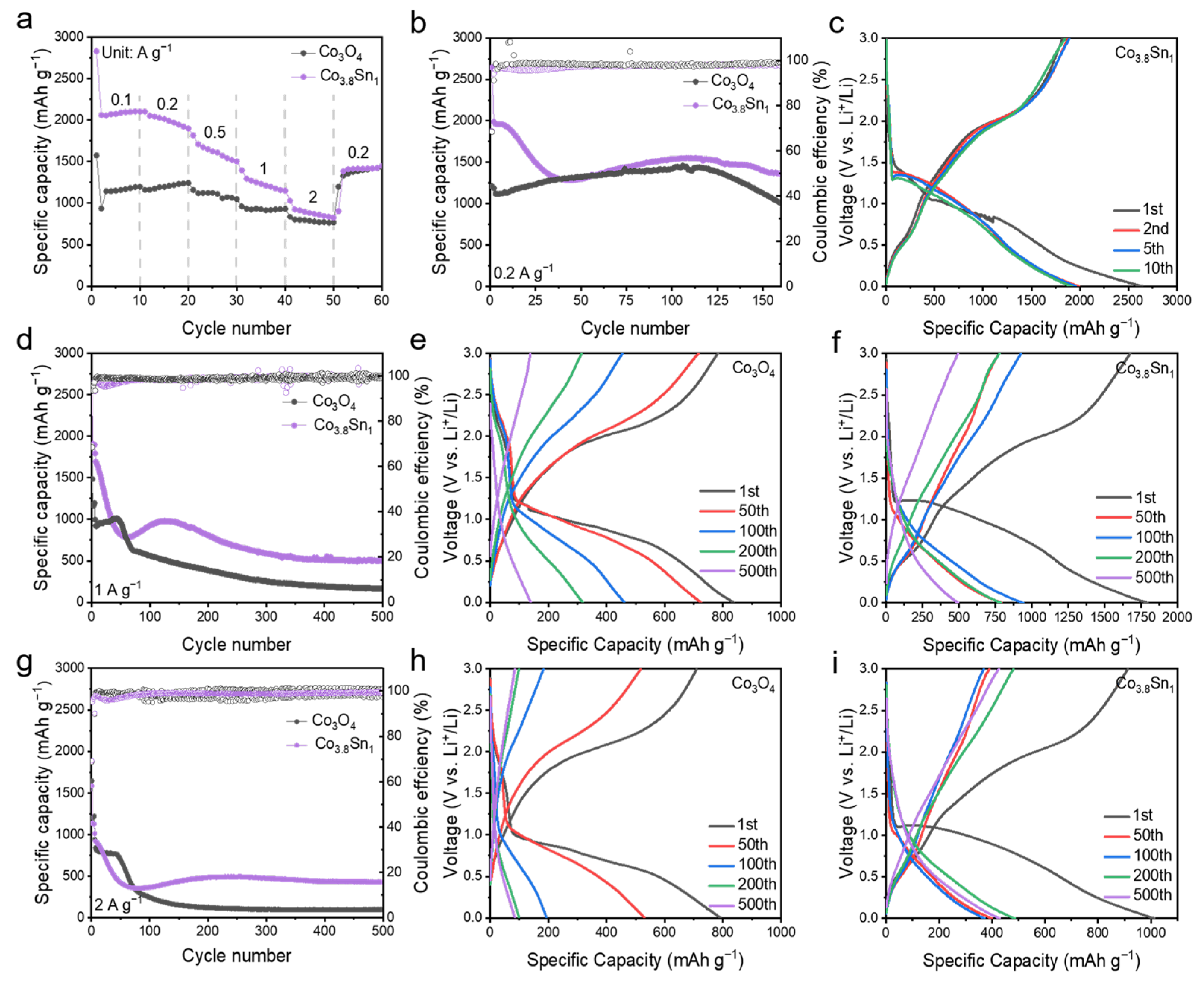

3.2. Electrochemical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, G.; He, L.; Wu, T.; Cui, G. The design of fast charging strategy for lithium-ion batteries and intelligent application: A comprehensive review. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Huang, T.; Li, L.; Xiong, W.; Huang, S.; Ren, X.; Ouyang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Cost-effective natural graphite reengineering technology for lithium-ion batteries. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yuan, Y.F.; Zheng, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.T.; Yin, S.M.; Guo, S.Y. Capsule-like Co3O4 nanocage@ Co3O4 nanoframework/TiO2 nodes as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2019, 253, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Bongard, H.; Spliethoff, B.; Schmidt, W.; Weidenthaler, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, D.; Schith, F. Controllable synthesis of mesoporous peapod-like Co3O4@carbon nanotube arrays for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7060–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shen, X.; Wang, G. Solvothermal synthesis and gas-sensing performance of Co3O4 hollow nanospheres. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 136, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mu, X.; Du, M.; Lou, Y. Porous rod-shaped Co3O4 derived from Co-MOF-74 as high-performance anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2017, 84, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, N.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y. Facile synthesis of Co3O4 with porous capsule-shaped structure and its lithium storage properties as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 31567–31575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, J.; Ramirez, D.; Myers, J.C.; Lodge, T.P.; Parsons, J.; Alcoutlabi, M. Performance and morphology of centrifugally spun Co3O4/C composite fibers for anode materials in lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 16010–16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.F.; Guo, Z.P.; Du, G.D.; Wexler, D.; Liu, H.K. Preparation of tin nanocomposite as anode material by molten salts method and its application in lithium ion batteries. Phys. Status Solidi A 2009, 11, 2546–2550. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Yao, T.; Liu, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, C.; Li, F.; Meng, L.; Cheng, Y. Porous N-doped carbon nanoflakes supported hybridized SnO2/Co3O4 nanocomposites as high-performance anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 560, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Hwa, Y.; Kim, H.C.; Choi, J.H.; Sohn, H.J.; Hong, S.H. SnO2@Co3O4 hollow nano-spheres for a Li-ion battery anode with extraordinary performance. Nano Res. 2014, 7, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Nie, Y.; Deng, P.; Wang, Q.; Xue, X. Facile synthesis and lithium storage performance of SnO2-Co3O4 core-shell nanoneedle arrays on copper foil. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 586, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, N.; Shi, D.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y. Superior lithium storage performance of SnO2-modified Co3O4 microflowers self-assembled with porous nanosheets as anode materials in Li-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 967, 171751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, D.; Li, W.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Catalytic activity boost of CeO2/Co3O4 hollow derived from CeCo-glycolate via yolk-shell structural evolution. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Fu, L.; Zuo, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Co3O4/CuO Hybrid hollow microspheres as long-cycle-life lithium-ion battery anode. Chem. Asian J. 2025, 20, e202401184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.; Shin, D.; Jeong, H.; Kim, B.; Han, J.; Lee, H. Highly water-resistant La-doped Co3O4 catalyst for CO oxidation. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10093–10100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ang, E.H.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, J. Imidazole-intercalated cobalt hydroxide enabling the Li+ desolvation/diffusion reaction and flame retardant catalytic dynamics for lithium ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.M.; Pawar, B.S.; Hou, B.; Ahmed, A.T.A.; Chavan, H.S.; Jo, Y.; Cho, S.; Kim, J.; Seo, J.; Cha, S.N.; et al. Facile electrodeposition of high-density CuCo2O4 nanosheets as a high-performance Li-ion battery anode material. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 69, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Gao, Z.; Hu, X.; Ling, R.; Cai, S.; Zheng, C.; Hu, W. Highly reversible and fast sodium storage boosted by improved interfacial and surface charge transfer derived from the synergistic effect of heterostructures and pseudocapacitance in SnO2-based anodes. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, S.; Selvam, K.; Babu, B.; Swaminathan, M. The simple hydrothermal synthesis of Ag-ZnO-SnO2 nanochain and its multiple applications. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 16365–16374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Wang, H. Metal organic framework derived Co3O4/Co@N-C composite as high-performance anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 855, 157538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, Y. Metal-organic framework-templated hollow Co3O4 nanosphere aggregate/N-doped graphitic carbon composite powders showing excellent lithium-ion storage performances. Mater. Charact. 2017, 132, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, N.; Zhai, C.; Yang, D. Synthesis of Co3O4@ SnO2@C core-shell nanorods with superior reversible lithium-ion storage. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 9511–9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zheng, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Peng, D. 3D Graphene encapsulated hollow CoSnO3 nanoboxes as a high initial coulombic efficiency and lithium storage capacity anode. Small 2018, 14, 1703513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.X.; Shi, Y.; Wong, J.I.; Ding, M.; Yang, H.Y. Designed hybrid nanostructure with catalytic effect: Beyond the theoretical capacity of SnO2 anode material for lithium ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Fu, L.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods as High-Capacity Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Physchem 2025, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040054

Zhang Q, Zhu J, Fu L, Liu D, Zhang Y. Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods as High-Capacity Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Physchem. 2025; 5(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qiyao, Jingchao Zhu, Lichao Fu, Dapeng Liu, and Yu Zhang. 2025. "Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods as High-Capacity Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries" Physchem 5, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040054

APA StyleZhang, Q., Zhu, J., Fu, L., Liu, D., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Co3O4/SnO2 Hybrid Nanorods as High-Capacity Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Physchem, 5(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040054