Structural Determinants for the Antidepressant Activity of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction

2.2. Preparation of Oleum Hyperici

2.3. Ultrasonic Relaxation Spectroscopy

2.4. Infrared Spectroscopy

2.5. Conformational Search and Clustering Procedures

2.6. Theoretical Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

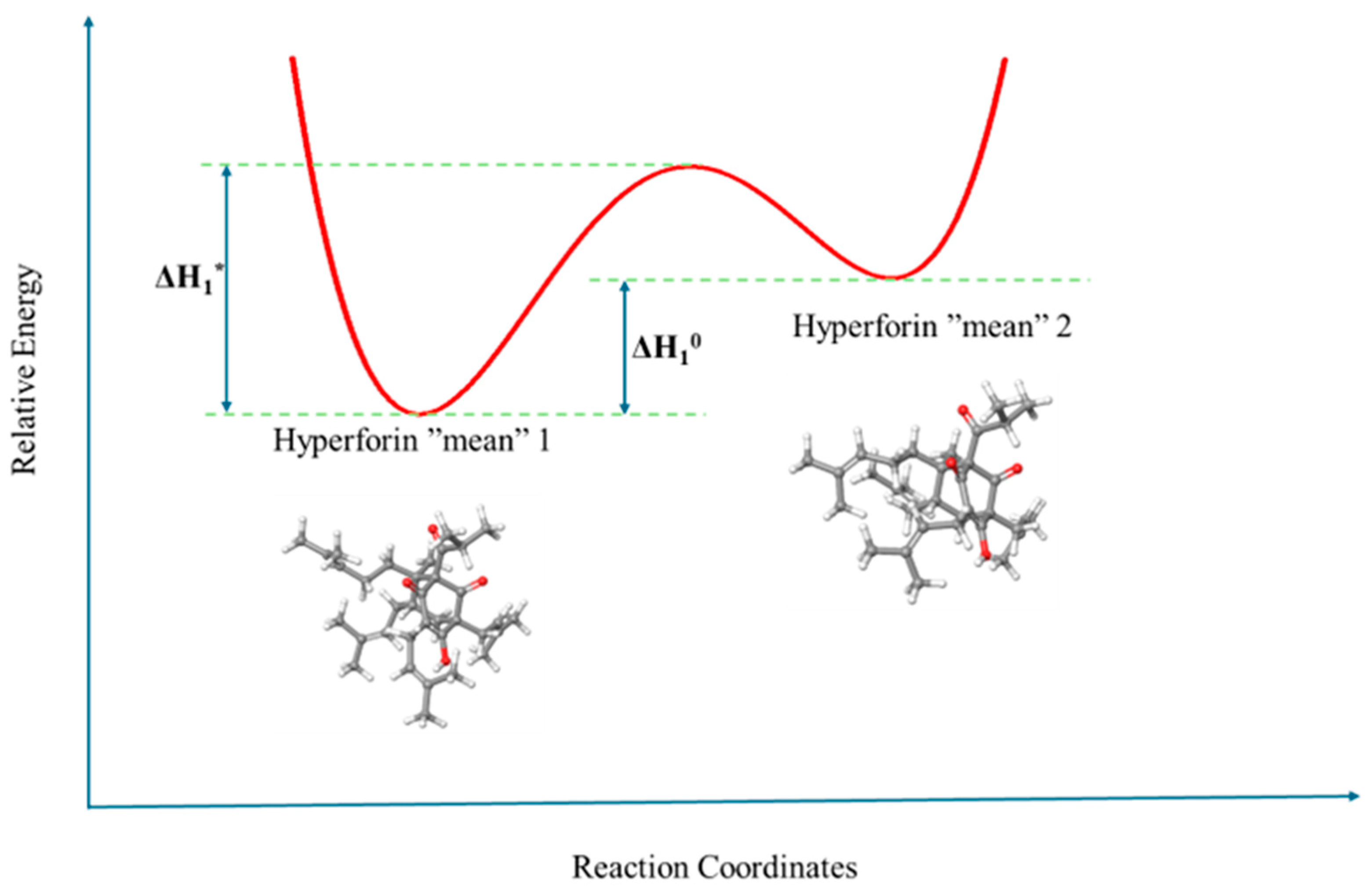

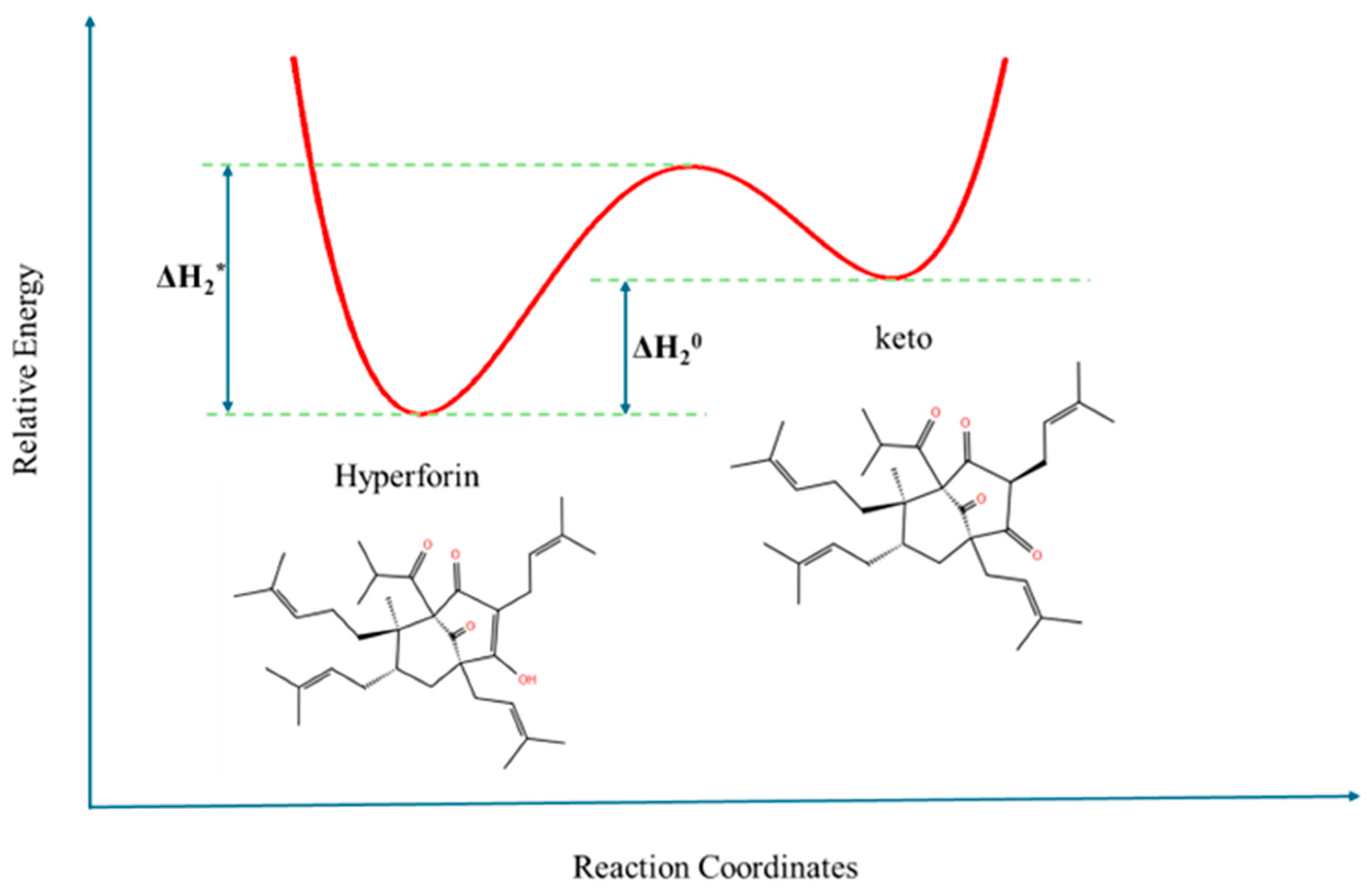

3.1. Structural Processes in Hyperforin Solutions

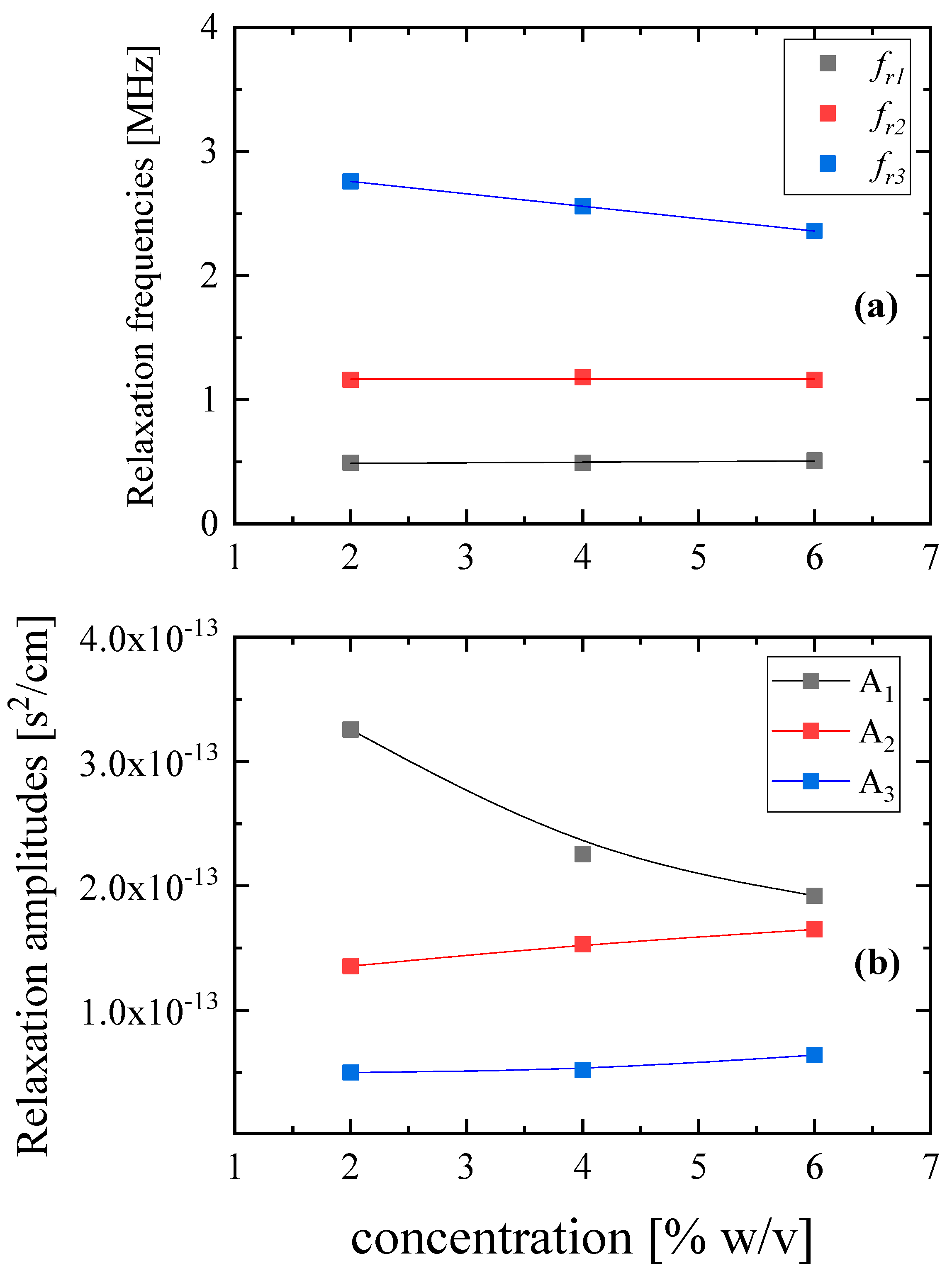

3.2. Ultrasonic Relaxation Spectroscopy—Concentration Effect on Relaxation Processes

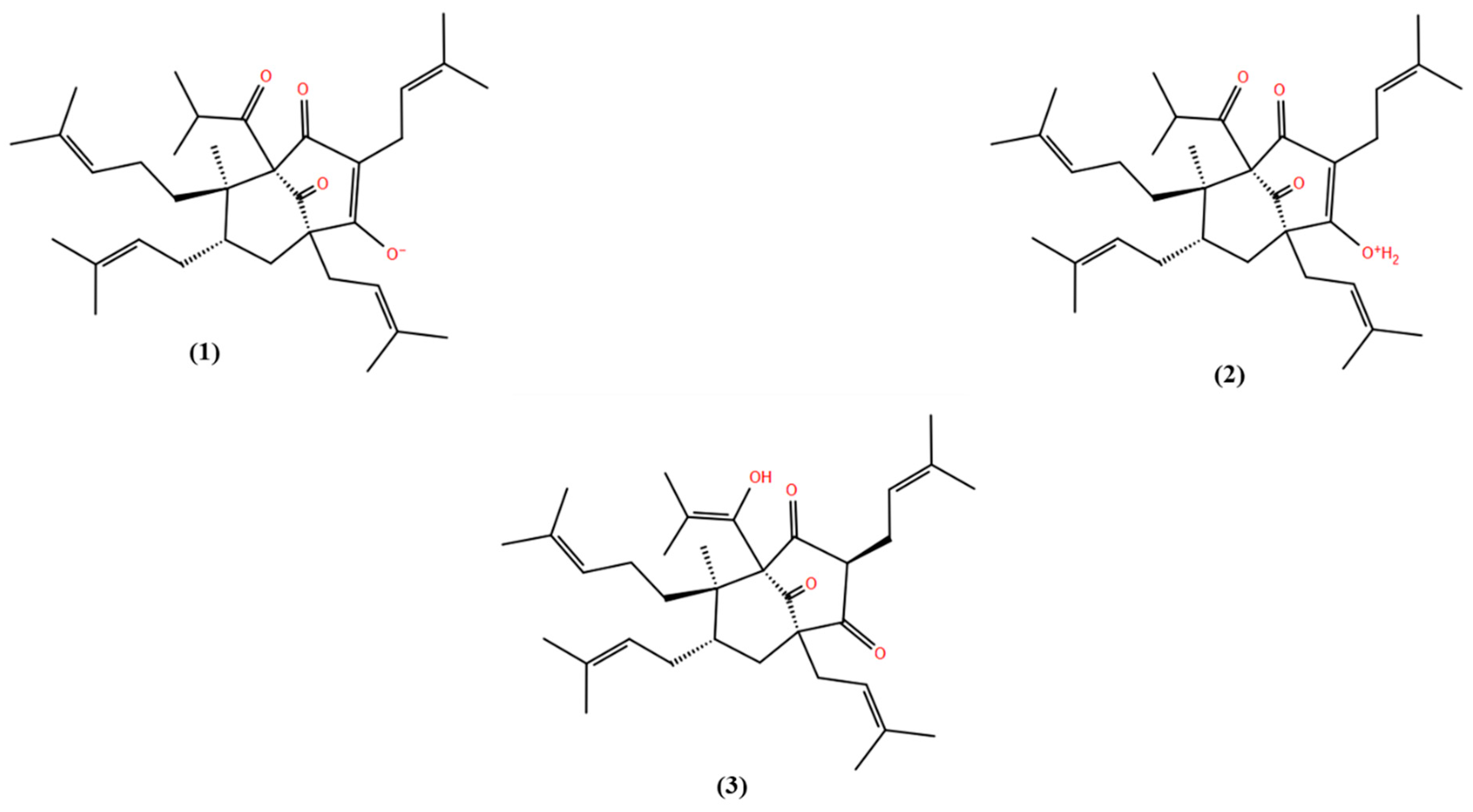

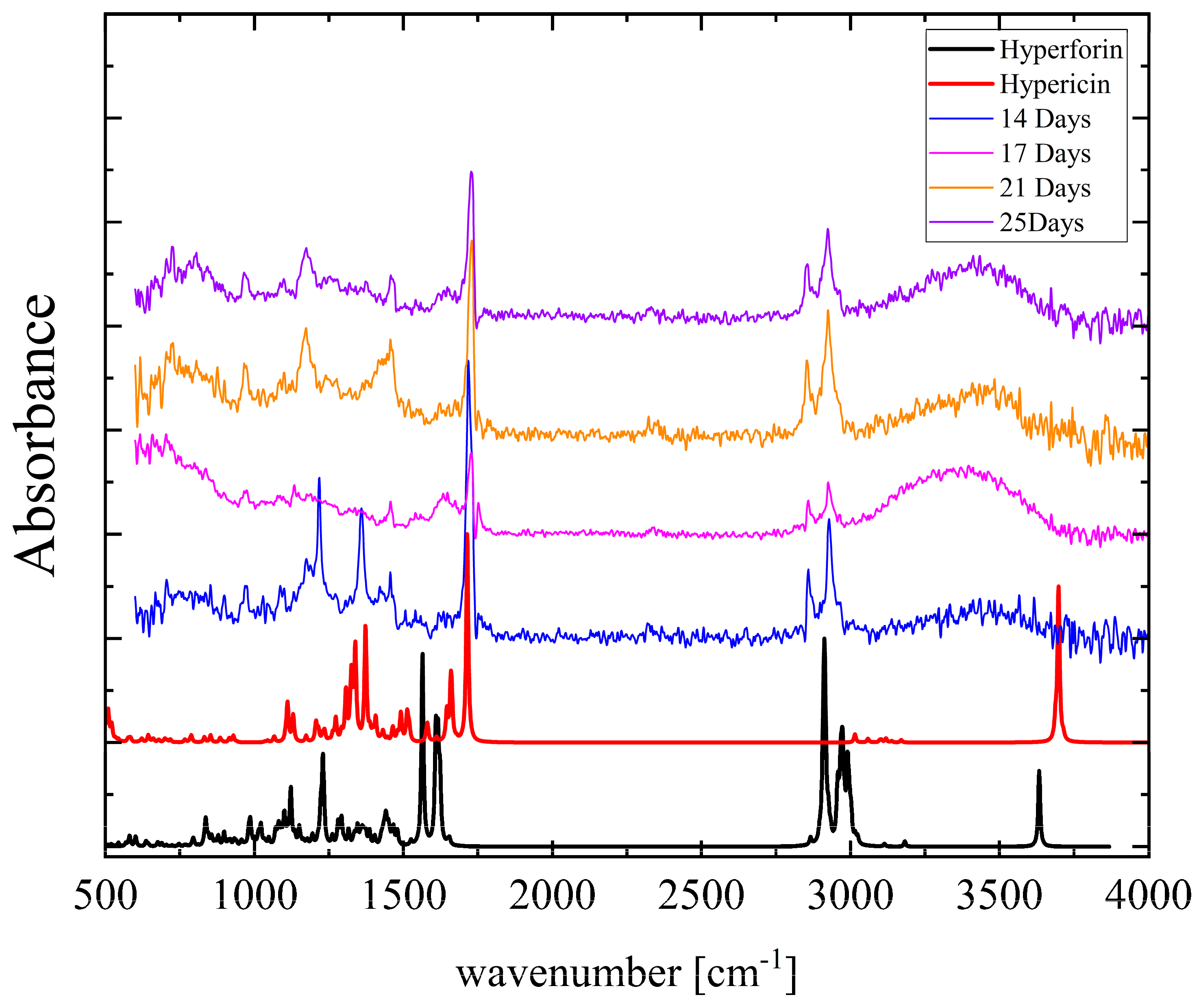

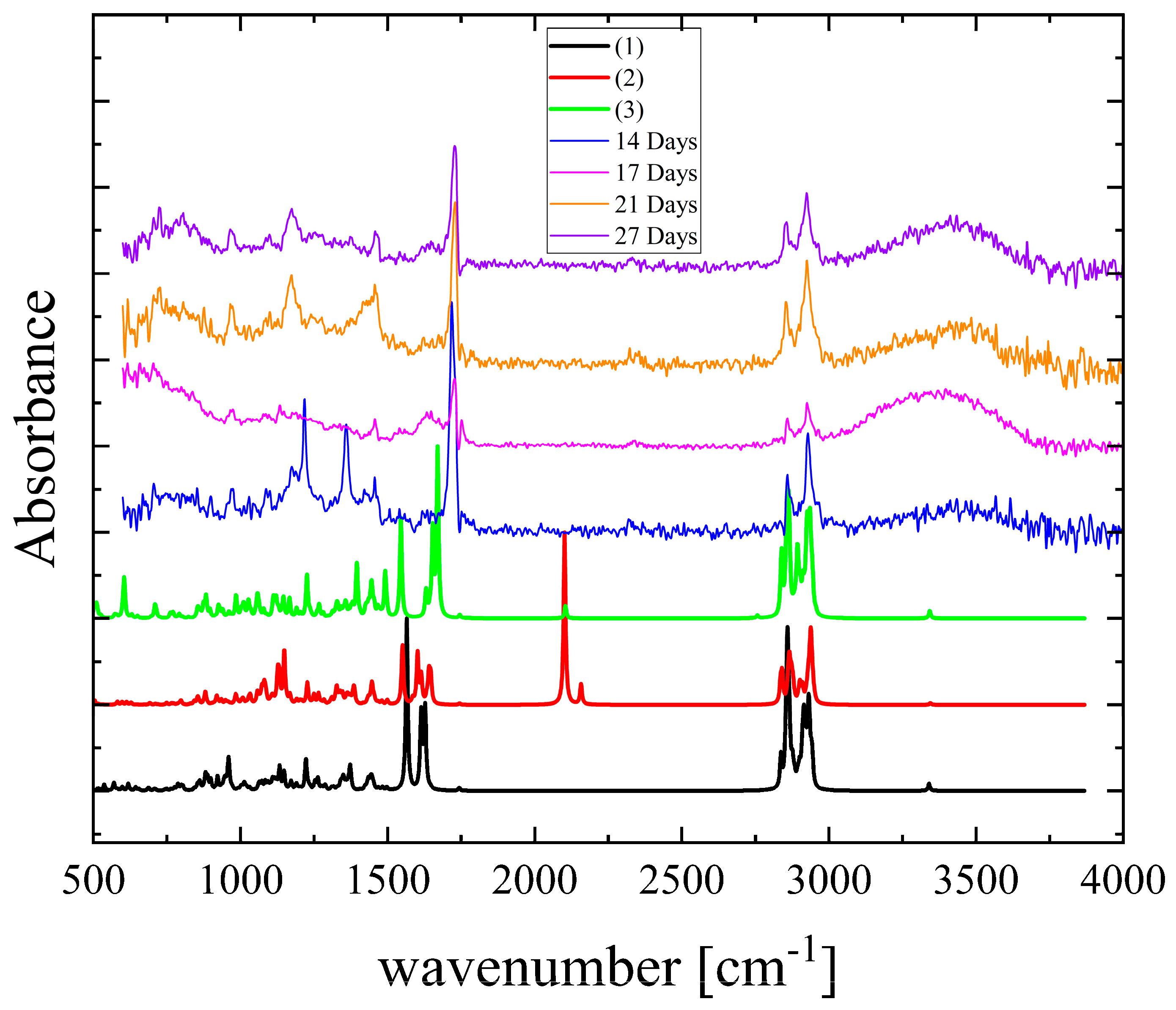

3.3. Vibrational Spectroscopy—Degradation Effect

3.4. ADMET Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butterweck, V.; Schmidt, M. St. John’s wort: Role of active compounds for its mechanism of action and efficacy. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2007, 157, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Sisking, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, G.; Borrelli, F.; Ernst, E.; Izzo, A.A. St John’s wort: Prozac from the plant kingdom. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001, 22, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, C.A.; Barnes, J.; Anderson, L.R. Herbal Medicines: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Linde, K. St. John’s wort—An overview. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2009, 16, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeson, J.M.; Sanford, B.; Monti, D.A. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): A review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature. Psychopharmacology 2001, 153, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.; Jobert, M. Effects of hypericum extract on the sleep EEG in older volunteers. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 1994, 7 (Suppl. S1), 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerhues, L. Hyperforin. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2201–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Wonnemann, M.; Singer, A.; Müller, W.E. Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of hypericum extracts. Life Sci. 1998, 63, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M.A.; Martínez-Poveda, B.; Amores-Sánchez, M.I.; Quesada, A.R. Minireview. Hyperforin: More than an antidepressant bioactive compound? Life Sci. 2006, 79, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.; Biber, A.; Erdelmeier, C. Hyperforin in Johanniskraut-Droge, -Extrakten und -Präparaten. Pharm. Unserer Zeit 2002, 5, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggelkraut-Gottanka, S.V.; Abu-Abed, S.; Müller, W.; Schmidt, P. Quantitative analysis of the active components and the by-products of eight dry extracts of Hypericum perforatum L. (St John’s wort). Phytochem. Anal. 2002, 13, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avato, P.; Guglielmi, G. Determination of Major Constituents in St. John’s Wort Under Different Extraction Conditions. Pharm. Biol. 2004, 42, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.F.; Ang, C.Y.W. Optimization of extraction conditions for active components in Hypericum perforatum using response surface methodology. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3364–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Noldner, M.; Koch, E.; Erdelmeier, C. Antidepressant activity of Hypericum perforatum and hyperforin: The neglected possibility. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998, 31 (Suppl. S1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdelmeier, C.A.J. Hyperforin, possibly the major nonnitrogenous secondary metabolite of Hypericum perforatum L. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998, 31 (Suppl. S1), 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, H.C.; Rentel, C.; Schmidt, P.C. Isolation, purity analysis and stability of hyperforin as a standard material from Hypericum perforatum L. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1999, 51, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouderis, C.; Tryfon, A.; Kabanos, T.A.; Kalampounias, A.G. The identification of Structural Changes in the Lithium Hexamethyldisilazide-Toluene System via Ultrasonic Relaxation Spectroscopy and Theoretical Calculations. Molecules 2024, 29, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarika, P.; Kouderis, C.; Kalampounias, A.G. Non-Debye segmental relaxation of poly-N-vinyl-carbazole in dilute solution. Mol. Phys. 2020, 119, e1802075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarika, P.; Papanikolaou, M.G.; Kabanos, T.A.; Kalampounias, A.G. Probing the equilibrium between mono- and di-nuclear nickel (II)-diamidate {[NiII(DQPD)]x, x = 1, 2} complexes in chloroform solutions by combining acoustic and vibrational spectroscopies and molecular orbital calculations. Chem. Phys. 2021, 549, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürsoy, O.; Smieško, M. Searching for bioactive conformations of drug-like ligands with current force fields: How good are we? J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tryfon, A.; Siafarika, P.; Kouderis, C.; Kalampounias, A.G. Insight into the Structural and Dynamical Processes of Peptides by Means of Vibrational and Ultrasonic Relaxation Spectroscopies, Molecular Docking, and Density Functional Theory Calculations. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Tanner, S.W.; Thompson, N.; Cheatham, T.E. Clustering Molecular Dynamics Trajectories: 1. Characterizing the Performance of Different Clustering Algorithms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 2312–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Performance of B3LYP Density Functional Methods for a Large Set of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory 2008, 4, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Milanović, Ž.B.; Dimić, D.S.; Avdović, E.H.; Milenković, D.A.; Marković, J.D.; Klisurić, O.R.; Trifunović, S.R.; Marković, Z.S. Synthesis and comprehensive spectroscopic (X-ray, NMR, FTIR, UV–Vis), quantum chemical and molecular docking investigation of 3-acetyl-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-2H-chromen-7-yl acetate. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1225, 129256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, Ž. Structural properties of newly 4,7-dihydroxycoumarin derivatives as potential inhibitors of XIIa, Xa, IIa factors of coagulation. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1298, 137049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lou, C.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. admetSAR 2.0: Web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics 2019, 15, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, G.; Lee, P.W.; Tang, Y. admetSAR: A comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 26, 3099–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oziminski, V.P.; Wojtowicz, A. New theoretical insights on tautomerism of hyperforin—A prenylated phloroglucinol derivative which may be responsible for St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) antidepressant activity. Struc. Chem. 2020, 31, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, I.; Rudshteyn, B.; Liebman, J.F.; Greer, A. Computed Regioselectivity and Conjectured Biological Activity of Ene Reactions of Singlet Oxygen with the Natural Product Hyperforin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giussi, J.M.; Gastaca, B.; Lavecchia, M.J.; Schiavoni, M.; Cortizo, M.S.; Allegretti, P.E. Solvent effect in keto–enol tautomerism for a polymerizable β-ketonitrile monomer. Spectroscopy and theoretical study. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1081, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvounis, I.G.; Siafarika, P.; Kalampounias, A.G. Vibrational and ultrasonic relaxation spectroscopic study of keto-to-enol tautomerism: The case of acetylacetone. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1286, 135592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandamer, M.J. Introduction to Chemical Ultrasonics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, K.F.; Litovitz, T.A. Absorption and Dispersion of Ultrasonic Waves; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Risva, M.; Siafarika, P.; Kalampounias, A.G. On the conformational equilibria between isobutyl halide (CH3)2CH–CH2X (X=Cl, Br and I) rotational isomers: A combined ultrasonic relaxation spectroscopic and computational study. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2022, 630, 413697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigoias, S.; Kouderis, C.; Mylona-Kosmas, A.; Boghosian, S.; Kalampounias, A.G. Proton-transfer in 1,1,3,3 tetramethyl guanidine by means of ultrasonic relaxation and Raman spectroscopies and molecular orbital calculations. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 229, 117958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Venkatanarayanan, N.; Ho, C.Y.X. Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süntar, I.P.; Akkol, E.K.; Yilmazer, D.; Baykal, T.; Kirmizibekmez, H.; Alper, M.; Yesilada, E. Investigations on the in vivo wound healing potential of Hypericum perforatum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schempp, C.M.; Pelz, K.; Wittmer, A.; Schöpf, E.; Simon, J.C. Antibacterial activity of hyperforin from St John’s wort, against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus and gram-positive bacteria. Lancet 1999, 353, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzzati, N.; Gabetta, B.; Strepponi, I.; Villa, F. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and multiple mass spectrometry studies of hyperforin degradation products. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 926, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, J.T.; Kim, A.; Nelson, K.; Bullard-Roberts, A.L.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Quave, C.L. The Chemical and Antibacterial Evaluation of St. John’s Wort Oil Macerates Used in Kosovar Traditional Medicine. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoli, P. Role of Hyperforin in the Pharmacological Activities of St. John’s Wort. CNS Drug Rev. 2004, 10, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, K.; Singer, A.; Henke, B.; Müller, W.E. Hyperforin activates nonselective cation channels (NSCCs). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 145, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, C.; Tian, F.; Xiao, B. TRPC Channels: Prominent Candidates of Underlying Mechanism in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, D.; Zündorf, I.; Dingermann, T.; Müller, W.E.; Steinhilber, D.; Werz, O. Hyperforin is a dual inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-1 and 5-lipoxygenase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 64, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurglics, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. Hypericum perforatum: A ‘modern’ herbal antidepressant: Pharmacokinetics of active ingredients. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolussi, S.; Drewe, J.; Butterweck, V.; Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E. Clinical relevance of St. John’s wort drug interactions revisited. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1212–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.B.; Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Wisely, G.B.; Serabjit-Singh, C.J.; Wilson, T.M.; Collins, J.L.; Kliewer, S.A. St. John’s wort induces hepatic drug metabolism through activation of the pregnane X receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7500–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Chaofeng, L.; Tang, Y. admetSAR—A valuable tool for assisting safety evaluation. In QSAR in Safety Evaluation and Risk Assessment; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Koyu, H.; Haznedaroglu, M.Z. Investigation of impact of storage conditions on Hypericum perforatum L. dried total extract. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisenbacher, P.; Kovar, K.A. Analysis and stability of Hyperici oleum. Planta Med. 1992, 58, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.; Georgieva, S.; Sotirova, Y.; Andonova, V. In silico study of the toxicity of hyperforin and its metabolites. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Hyperforin | Keto | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 536.8 | 536.8 | 536.8 | 522.77 | 536.8 |

| nAtom | 39 | 39 | 39 | 38 | 39 |

| nHet | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| nRing | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| nRot | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| HBA | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| HBD | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TPSA | 71.44 | 68.28 | 71.44 | 71.44 | 71.44 |

| logP | 6.76 | 6.76 | 7.48 | 7.36 | 8.14 |

| Parameter | Hyperforin | Keto | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 | −4.41 | −4.41 | −4.63 | −4.58 | −4.54 |

| HIA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| BBB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pgp inhibitor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pgp substrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PPB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CYP3A4 substrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CLp | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CLr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T ½ | −1.48 | −1.48 | −1.99 | −1.97 | −2.1 |

| MRT | −1.36 | −1.36 | −1.88 | −1.86 | −2.03 |

| Parameter | Hyperforin | Keto | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hERG 10 uM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| hERG 10–30 uM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nephrotoxicity | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin corrosion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin irritation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Skin sensitization | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Acute dermal toxicity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ames mutagenesis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute oral toxicity | −2.08 | −2.08 | −2.74 | −2.55 | −2.66 |

| FDAMDD | 2.0 | 2.02 | 1.56 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tryfon, A.; Petsis, G.; Siafarika, P.; Soubasi, E.; Kalampounias, A.G. Structural Determinants for the Antidepressant Activity of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. Physchem 2025, 5, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040056

Tryfon A, Petsis G, Siafarika P, Soubasi E, Kalampounias AG. Structural Determinants for the Antidepressant Activity of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. Physchem. 2025; 5(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleTryfon, Afrodite, George Petsis, Panagiota Siafarika, Evanthia Soubasi, and Angelos G. Kalampounias. 2025. "Structural Determinants for the Antidepressant Activity of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study" Physchem 5, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040056

APA StyleTryfon, A., Petsis, G., Siafarika, P., Soubasi, E., & Kalampounias, A. G. (2025). Structural Determinants for the Antidepressant Activity of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. Physchem, 5(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem5040056