Abstract

The manufacturing of detergent products such as laundry detergents or household cleaners is of increasing interest to the chemical industry. Surfactants and fatty acids are the most important ingredients in detergent formulations, as they are responsible for the cleaning power and the antimicrobial efficiency of the cleaning product. Computational tools can play a key role in the design and performance optimization of detergent products as they allow for quick and efficient screening of candidate surfactants in detergent formulations. In the present study, an automated fragmentation and parametrization protocol is utilized to investigate the adsorption of candidate fatty acid surfactants towards bacterial inner membranes. The effect of the surfactant size, concentration, and tendency for micelle formation on the degree of their adsorption on the inner membrane is examined. Analysis demonstrates that surfactant–inner membrane interaction weakens with surfactant size and aggregation tendency, as confirmed by pertinent experimental and simulation studies. The outcome of this study demonstrates that the adopted multiscale protocol allows for an accurate and cost-effective description of the systems examined at timescales much shorter than those required in laboratory experiments and atomistic simulations.

1. Introduction

Due to their ability to adsorb onto and solubilize bacterial membranes as well as their low toxicity and biodegradability, biosurfactants and fatty acids (FAs) have recently emerged as appealing antimicrobials and alternatives to synthetic surfactants [1,2,3,4]. Cationic surfactants, in particular the widely used quaternary ammonium compounds (quats), are the best known class of anti-microbial surfactants [1]. On the other hand, FAs are organic compounds that contain carboxylic acids and long, unbranched carbon chains and optionally double bonds [5,6]. Free FAs have been utilized in several membrane-mediated cellular processes, from the fusion of lipid vesicles and cells to the inhibition of the growth of bacteria via membrane disruption [7,8]. However, due to the complexity of the bacterial cell envelope, there is a growing need for a deeper understanding of the interactions between FAs and bacterial cells at the molecular level to further optimize the antimicrobial activity of the former [9,10].

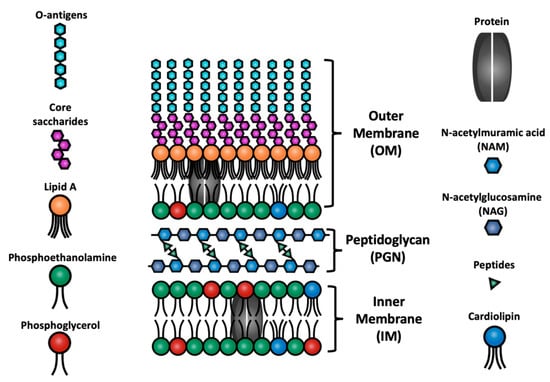

In the present study, a multiscale simulation approach was developed and utilized to examine the adsorption efficiency of FA anionic surfactants on bacterial membranes. In particular, this work is focused on the surfactant activity towards Gram-negative cell architecture, as found, for example, in Escherichia coli bacteria [11]. The cell envelope of the latter, illustrated in Figure 1, consists of an outer membrane (OM) composed of lipopolysaccharides and lipids, an intermediate peptidoglycan layer, and a phospholipid inner membrane [12]. Antimicrobials initially bind to the OM and subsequently penetrate the bacterial cell walls before adsorbing onto and solubilizing the inner membrane [13]. This study is focused on the final part of the antibacterial activity described earlier, i.e., the interactions of the fatty acids with the inner membrane.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the different components and the cell envelope of Gram-negative E. coli bacteria [13], “Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ref. [13]. Copyright 2022, Sharma, P.; Vaiwala, R.; Parthasarathi, S.; Patil, N.; Verma, A.; Waskar, M.; Raut, J. S.; Basu, J. K.; Ayappa, K. G.”.

Multiple factors govern the ability of surfactants to disrupt and solubilize the bacterial cell envelope, such as the chain length, the electric charge, their molecular topology, and the critical micelle concentration. On the other hand, the barrier properties of the peptidoglycan layer, the protonation state, and the bending modulus of the phospholipid bilayer have been found to impact its binding to the surfactants [13,14]. The activity of antimicrobial cleaning products has been extensively examined via laboratory experiments. For example, the time-kill kinetics assays evaluate antimicrobial activity by exposing the test microorganism to different concentrations of the antimicrobial agent over a specific duration [15]. Sharma et al. conducted time-kill kinetics assays against bacterial strains to determine the bactericidal activity of the antimicrobial agents over time [13]. Such studies have provided significant insights into the cleansing efficacy of antimicrobial agents and led to the design of detergent products with optimized cleansing performance. However, given the large number of factors influencing the performance of the candidate agents, laboratory work becomes frequently time-consuming and highly costly to cover the entire candidate space.

Furthermore, the nature of the FA–lipid interactions is poorly understood, mostly due to the inherent complexity of the cell envelope. For example, it remains unclear whether surfactant FAs bind to the OM and subsequently disrupt and solubilize it or whether they penetrate the OM through channels to access the inner membrane [13].

Molecular and mesoscale simulations can shed light on mechanisms governing the lipid–surfactant association and thus can successfully complement experimental work. Molecular dynamics (MDs) simulations have been employed to study structural properties of bacterial membranes and their interactions with small molecules and antibiotics. All-atom force fields have been optimized to accurately describe the self-assembly behavior of a wide range of lipid bilayers [16,17,18]. Lee et al. [19] examined the binding and insertion mechanisms of cationic surfactants into lipid bilayers via MD simulations. Other studies have provided a molecular-level understanding of the free energy landscape of the OM, demonstrating that the free energy barriers for molecular translocation across the OM are quite distinct from the respective energy barriers in the inner membrane [20]. Structural properties of the interface of the external layer of the outer membrane of the E. coli bacteria with water have also been investigated via MD simulation [21]. Moreover, surfactant and FAs collective properties like self-assembly and partitioning of surfactants [22,23] that play a crucial role in their interactions with mammalian cell membranes, have been thoroughly examined via atomistic MD simulations. However, given the long timescales associated with the surfactant uptake by the phospholipid, a fully atomistic simulation of such phenomena would reach several hundreds of ns, thus requiring several weeks in current HPC workstations [13,19]. An alternative to the all-atom MD simulation approach is coarse-graining mesoscopic techniques [22,24]. To simulate at longer time scales, one needs to simplify the simulation model. Indeed, for large-scale collective motions, or for mechanisms operating on long timescales, not all atomistic details of the model are essential. In these approaches, several atoms of a molecule/system are grouped into super atoms (coarse-grained beads) and non-relevant degrees of freedom are eliminated, thus allowing systems of large sizes and accessing longer time scales. At the coarse-grained level, MARTINI is a well-established parameterization scheme, specifically developed to investigate biological interactions, mainly focused on lipid membrane characteristics and protein−ligand interaction [25]. In particular, coarse-grained models for the OM of Gram-negative bacteria have been developed in the Martini-3 framework [26]. The coarse-grained model force field was parametrized and validated against all-atom MD simulations [26].

A robust simulation technique that bridges the gap between atomistic and mesoscopic simulation is dissipative particle dynamics (DPDs) [27]. Groot and co-workers applied DPD simulations to a bilayer of phosphatidylethanolamine [28]. The membrane structural attributes were found to qualitatively match with fully atomistic simulations and experiments reported in the literature. Furthermore, membrane disruption when the phospholipid bilayer was exposed to nonionic surfactants was also investigated [28]. Other reported DPD studies on lipid membranes examined the structural and thermodynamic properties [29], their response to shear flow [30] and the development of a CG potential for solvent-free DPD simulation [31].

In the present work, the phospholipids and surfactant FAs parameter sets were obtained via a well-established Automated Fragmentation and Parametrization (AFP) [32] protocol. This protocol allows us to automatically translate information from the chemical atomistic domain to the mesoscale at the coarse-grained level. As stated earlier, the present study focuses on the interaction and adsorption of surfactant FA molecules onto the bacterial inner membrane and the effects of structural and collective properties on their adsorption efficiency. The findings of this work reveal that the extent to which the surfactants adsorb onto the inner membrane is a function of their hydrophobic chain length as well as their clustering tendency.

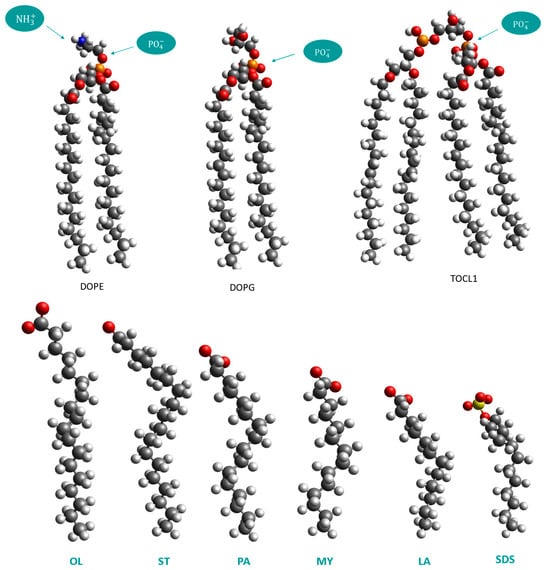

Specifically, the adsorption efficiency of dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as well as of salts of laurate, myristate, palmitate, stearate, and oleate (or its trans isomer elaidate) FAs, is investigated. The atomistic structures of the phospholipids constituting the bacterial inner membrane, together with the candidate FAs, are illustrated in Figure 2. Previous atomistic MD simulations reported an increased bacterial kill efficacy of laurate over other surfactants, supporting findings of contact time-kill experiments with E. coli suspensions [13]. To make a fair comparison between the adsorption efficiencies of the candidate FAs as well as to examine their tendency to form micellar aggregates, the surfactant concentration in each system was higher than its respective CMC. In addition, surfactants of varying hydrophobic chain length are introduced to examine size effects on their overall adsorption efficiency. Section 2 describes the adopted simulation approach, whereas in Section 3, the major results of the study are presented and discussed.

Figure 2.

(Top) Atomistic models of the lipids 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-1-glycerol (DOPG), and 1,3-bis(1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho)-glycerol (TOCL1) that constitute the bacterial inner membrane. (Bottom) Left to right: Atomistic models of surfactants oleate (OL) or its stereoisomer elaidate, stearate (ST), palmitate (PA), myristate (MY), laureate (OL), and dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

2. Model and Method

All simulations were performed with the aid of Simcenter Culgi version 2211 [33]. As the surfactant number density in the simulation boxes was chosen to exceed their CMC values [13], the surfactant aggregation behavior was also probed. To examine system size effects on the simulation findings, systems comprising both single and double bilayer models were generated. The results showed minor system size dependence of the results.

As stated earlier, the AFP protocol [32] was used to map the atomistic models of both the phospholipids and the FAs to coarse-grained molecules. Each coarse-grained bead is, by definition, radially symmetric. This protocol is briefly described below.

2.1. Mapping the Atomistic Structures to Coarse-Grained Models

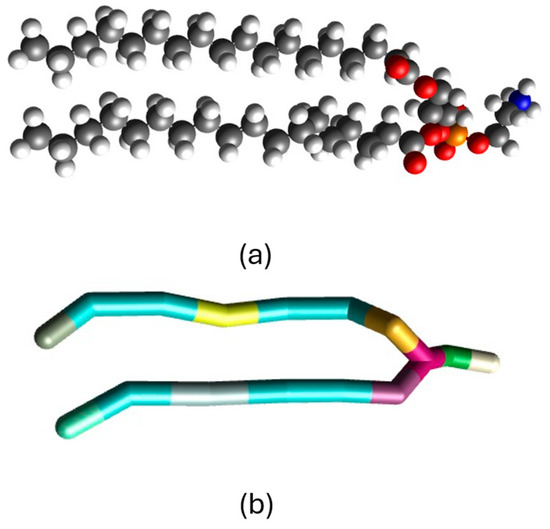

Each of the atomistic structures presented in Figure 2 was mapped to a coarse-grained soft-core molecule consisting of connected beads. A Monte Carlo approach that satisfies a scoring function was used to generate the optimal fragmentation of the atomistic models. Specifically, fragmentation is cast into a problem of global minimization, where a scoring function evolves by simulated annealing (a stochastic optimization method). The simulated annealing consists of moving the boundaries of trial fragmentations in a molecule and cutting through bonds accordingly. Each bead in the coarse-grained molecule comprises a fragment bearing a minimum number of three and a maximum of four heavy atoms of the atomistic structure. It should be noted here that the number of heavy atoms per bead is an adjustable parameter in our workflow. The atomistic structure, as well as the obtained coarse-grained equivalent for DOPE, is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(a) Atomistic structure of the DOPE phospholipid and (b) the mapped coarse-grained model.

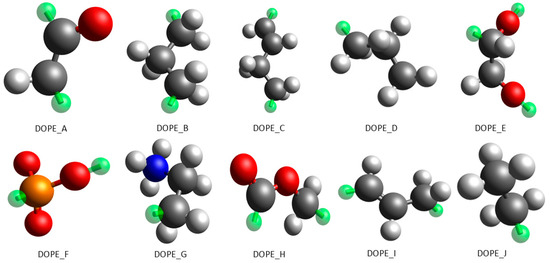

The fragmentation process for DOPE resulted in 10 different fragments. It should be noted that the stereochemistry of acid substituents in the lipids is not considered in the coarse-grained model. This is also the case in pertinent coarse-grained studies [29,34,35]. For the study of the bilayer–surfactant interactions, effects linked to the stereochemistry of the phospholipids can be considered as minor. All DOPE fragments, as well as their assigned bead-types, are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The ten different fragments of which the coarse-grained model of DOPE is composed. Color code: gray, carbon; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; white, hydrogen; orange, phosphorous; green, connector.

2.2. Parameterization of the Coarse-Grained Interactions

Following the fragmentation of the atomistic structures, the parametrization of the intra- and intermolecular interactions in the coarse-grained models was conducted.

2.2.1. Intramolecular Interaction Parameters

The basic principle in developing the bonded interaction potentials in the coarse-grained soft-core model was to construct the distribution function of each of these quantities from atomistic model simulations. The intramolecular interactions involving bond stretching and angle bending were represented by harmonic potentials. The bond potential, , as a function of the distance between fragments k and l, is given as follows:

where is the force constant and is the equilibrium bond length. The angle potential, as a function of the angle θklm between fragments k, l, and m is given as follows:

Here, is the force constant and is the equilibrium angle. The parameters , and in Equations (1) and (2), are obtained by fitting the bond and angle distributions obtained from short DPD simulations to corresponding mapped MD simulations.

2.2.2. Intermolecular Interaction Parameters

The intermolecular bead-bead interaction, , as a function of the distance between fragments i and j, is modeled by the purely repulsive Hoogerbrugge–Koelman interaction potential [36]

where is the repulsive interaction parameter and is the cutoff distance. The cutoff distance is, according to the AFP protocol, set to 7.66 Å, independent of fragments k and l. The bead-bead independent -parameter is obtained via four consecutive steps, which are briefly explained below.

At an initial stage, a COSMO surface for each of the molecules comprising the system is obtained. The COSMO surface represents the charge distribution around the molecule in hand and is calculated with a quantum calculation using the NWChem code [37], or through the computational framework AM1-Bond charge correction-COSMO [38], which allows us to calculate the charged “envelope” of a molecule. An example of the COSMO surface of a DOPE molecule is given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

COSMO surface profile of a DOPE molecule. Color code: red, negative; white, neutral; blue color, positive; gray color, no data.

Afterward, the molecular COSMO profile is split into different fragmental COSMO surfaces. In the case of the DOPE molecule, these surfaces belong to the fragments given in Figure 4. Following the COSMO surface calculation, the next step is to calculate the residual Gibbs free energy of mixing, , of two fragments k and l in a 50/50 molar ratio mixture using the COSMO surfaces of both fragments and the Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents (COSMO-RSs) equation [39]. In addition, the COSMO-volume of each fragment k must be obtained. The final step is to translate , and to a DPD -parameter using the empirically obtained equation:

where with the reference COSMO-volume of water trimer. The DPD intermolecular a-parameter is therefore related to density and excess (residual) Gibbs free energy quantities.

First, the intra- and intermolecular DPD parameters were used to generate an initial configuration of the soft-core inner membrane model solvated in water. To do this, the GUI of Simcenter Culgi was utilized. In all studied models, the lipid compositions for DOPE/DOPG/TOCL correspond to the inner membrane of E. coli, i.e., ∼75:20:5 [13]. The phospholipids’ center-of-mass z-position was 0.25 Lz and 0.75 Lz, respectively, where LZ is the box size in its longest dimension. The box size was chosen to be sufficiently large to allow for sufficient solvation of the lipid bilayer, as well as to be comparable to box sizes used in pertinent simulation studies. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions. The lipid hydrophilic groups were positioned such that they point towards the solvent molecules. The latter were placed in the box volume unoccupied by solute molecules to ensure that no water penetrates the bilayer structure. Each coarse-grained water bead contains 3 water molecules. Negatively charged single beads (counterions) were also added to the box to ensure charge neutrality. As the interactions of the ions with the remaining system components are mainly electrostatically driven, the ion type is of minor importance. On these grounds, we can set the ion-ion -parameter equal to the corresponding value of the interaction between a pair of water beads to a reasonable approximation.

It should be stressed here that the applied model accounts for hydrodynamic interactions but does not explicitly consider hydrophobic effects or entropic contributions of water molecules residing in the vicinity of the surfactant hydrophobic tail to its overall behavior. On these grounds, any preferential interactions are implicitly considered via differences in the respective interaction parameter values and ionic interactions. Entropic contributions can be explicitly captured via atomistically detailed potentials [19], but such studies are beyond the scope of the present work.

Prior to proceeding to the equilibration run, the system was subjected to energy minimization to remove high-energy overlaps. To ensure that the bilayer area reaches an equilibrium value, i.e., its surface tension is zero, an independent pressure coupling in the bilayer plane and perpendicular to the plane is required [40]. To this end, the system was simulated at the semi-isotropic isobaric isothermal ensemble (NPxPyPzT). All simulations were carried out at a temperature T = 298 K. The temperature and anisotropic pressures were maintained constant with the aid of the Andersen thermostat [41]. The duration of the run was 500,000 DPD steps with a time step equal to 0.02 DPD units. Fraaije et al. [42] performed an assessment on how the stochastic DPD time-step converts to physical time. Comparing the DPD diffusion coefficient to experimental data, they found that a time-step of 0.01 corresponds to 640 fs [42]. Therefore, since we are using a time step of 0.02, each step corresponds to 1.28 ps, i.e., larger by more than 3 orders of magnitude than the time steps used in atomistic simulations. In all cases, equilibration was verified by monitoring the box dimensions over the course of the simulation run. The simulation box size in the Z direction stabilized to an average value of 42 nm with an error of 0.2%. The associated fluctuations in the total potential energy and box density were of the same order.

Following the generation of the lipid bilayer models, surfactant molecules were placed randomly in the space between the two bilayers. The CMCs of the candidate surfactants vary from ~1 mM to ~25 mM [13,43,44]. In our study, 100 or 200 FA molecules were introduced into the bilayer models. This corresponds to a concentration of ~28 and ~56 mM, respectively.

Furthermore, to examine whether the aggregation behavior of the surfactants is the result of a kinetic effect, in addition to starting from a random distribution of FAs, systems where the latter were placed in contact with the bilayer were also generated.

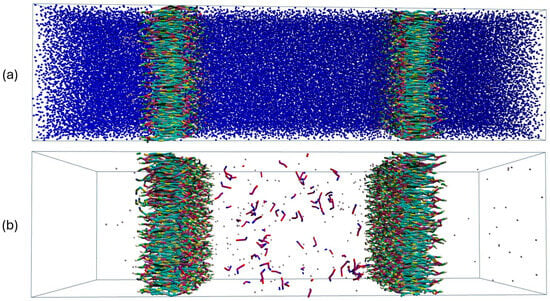

For all systems, production runs of 1,000,000 steps were conducted afterward at the canonic (NVT) ensemble. Snapshots of equilibrated LA-loaded bilayer models are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Snapshot of the initial configuration of the double-bilayer model. Water is depicted in blue color. (b) Snapshots of equilibrated configurations of the double-bilayer models where LA surfactants are introduced. Water molecules are omitted for clarity.

3. Results and Discussion

To gain insight into the surfactant–surfactant and bilayer–surfactant interactions, the respective intermolecular radial distribution functions (RDF) were evaluated. The latter effectively counts the average number of b neighbors in a shell at distance r around an a particle (molecule) defined as follows:

where a and b represent two different types of molecules, and the RDF is calculated by taking the center of mass of each molecule. The indices i and j refer to molecules of type a and b, respectively, and the sums on the right-hand side of (3) run over the total number of molecules of type a and b. The RDF is normalized so that it becomes 1 for large separations in a homogenous system.

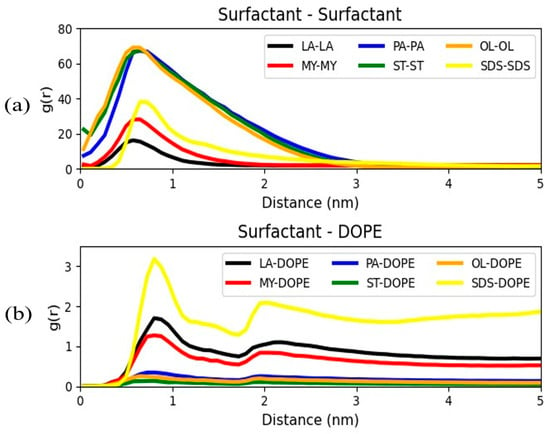

The surfactant–surfactant intermolecular RDFs are presented in Figure 7a. Additionally, RDFs between the surfactants and each one of the bilayer components, DOPE, DOPG, and TOCL1, were calculated. As the aforementioned RDFs present very similar behavior, Figure 7b only illustrates the RDFs between the surfactants and the DOPE phospholipid. This phospholipid bears the highest proportion in the lipid bilayer.

Figure 7.

Radial distribution functions between (a) the surfactant FAs and (b) the DOPE and surfactant FAs.

Examining the top panel of Figure 7, we can detect that the surfactant–surfactant RDFs reach a peak at a large distance ranging from 0.7 to 0.9 nm. This denotes that, at these distances, the surfactants tend to aggregate in micellar structures. We can also discern that the magnitude of these peaks is proportional to the surfactant size. Hence, larger size surfactants are more prone to form clusters, and the lowest peak is reported for laurate, the smallest size surfactant [13]. In particular, palmitate, oleate, and stearate curves are very similar, demonstrating that there is a critical chain length above which surfactant–bilayer interactions become negligible and aggregation behavior dominates.

On the other hand, examination of the DOPE-surfactant curves displayed in Figure 7b, shows the existence of a primary peak located at approximately 0.8 nm and a secondary peak at around 2 nm. DOPE appears to have the strongest interaction with SDS, followed by laurate. As the hydrophobic tail of laurate and SDS is of the same size, the higher lipid affinity for SDS can be ascribed to its larger sulfate headgroup compared to the smaller carboxylic headgroups of the other anionic surfactants. It can also be observed that lipid–surfactant interactions weaken with surfactant size.

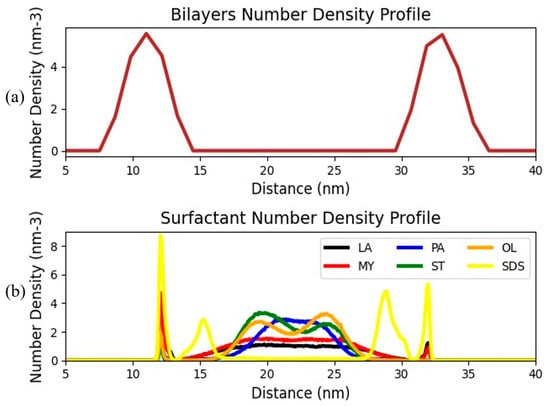

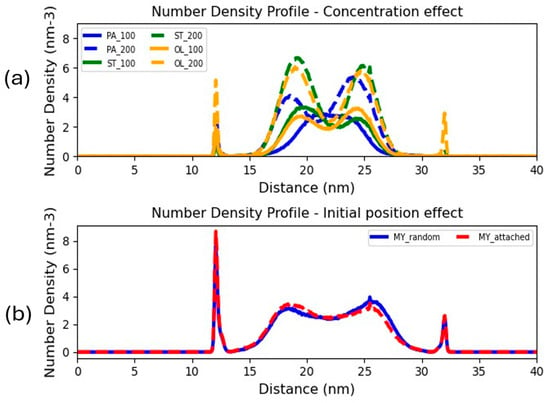

Following the inspection of favorable FA–bilayer interactions, we proceeded to the examination of the degree of adsorption of the surfactant FAs onto the bilayer. To achieve this, the number density profiles of both the phospholipids and the bilayers were evaluated. Figure 8 illustrates the number density distribution (the number of particles that are present in a particular volume) of the bacterial inner membrane, as well as the corresponding profiles of the incorporated surfactants for systems loaded with 100 surfactants and FAs.

Figure 8.

(a) Number density profiles of (a) the phospholipid bilayer in the FA-free model and (b) the surfactant molecules for the systems loaded with FAs.

Focusing on the top panel, one can easily discern the peaks located at distances approximately equal to 11 and 33 nm, corresponding to the double bilayer molecules. On the other hand, the bottom panel curves display surfactant peaks in the vicinity of the bilayer lipids, thus clearly demonstrating an adsorption of the surfactants onto the lipid bilayer. To assess the degree of the FA adsorption, the number density profiles were integrated. The surfactants were ranked based on their adsorption efficiency as follows: SDS > LA > MY > PA> ST > OL. The previous finding denotes that the adsorption efficiency of the surfactant is inversely proportional to its chain length. This is consistent with findings from contact time kill experiments reporting that shorter chain surfactants, laurate and SDS, show better bacterial kill efficacies compared to longer chain surfactants [13].

Further examination of the larger size surfactant number density profiles reveals the existence of secondary peaks located in the region of solvent confined by the two phospholipid bilayers, ranging between 15 and 27 nm. These peaks denote the tendency of larger size surfactants (ST, PA, and OL) to form aggregates rather than interacting with the lipid bilayers. Specifically, we can discern a double peak for ST and OL (the largest size FAs), detected at approximately 19 and 24 nm, revealing the existence of two distinct FA populations in this region. The similarity in the density profiles of the earlier-mentioned surfactants is expected, as their only structural difference is the fact that oleate is unsaturated. On the other hand, the number densities in the bilayer-free region of the other FAs decrease as the surfactant size drops. In the case of SDS, two additional peaks at distances approximately equal to 4 nm from the phospholipids are detected, whereas no sign of SDS surfactants is observed in the intermediate solvent region. We stress here that the distinction between the left and the right interface peaks for SDS is an artifact of the way the simulation is conducted.

To examine concentration effects on the surfactant adsorption tendency, the surfactant density profiles for systems containing 100 and 200 FAs were obtained. The density profiles for all examined surfactants exhibited minor concentration effects. Indicatively, the profiles of the larger size FAs (PA, ST, and OL) displayed in Figure 9a exhibit, as expected, higher peaks in the region confined by the bilayers at elevated concentration. However, the general order of adsorption efficiency is not altered, demonstrating that the increase in surfactant concentration has a minor effect on their overall adsorption efficiency.

Figure 9.

(a) Number density profiles of (a) Surfactant number density profiles for systems loaded with 100 and 200 PA, ST, and OL surfactants. (b) Number density profiles of MY surfactants initially placed randomly in the region confined by the 2 bilayers or in close proximity to the bilayer surface.

Complementary to the investigation of concentration effects on the FAs adsorption behavior, we conducted additional simulations starting from configurations where the surfactants were placed close to the bilayer to check if the initial position of the former impacts their adsorption efficiency. As similar behavior was detected for all examined surfactants, Figure 9b displays the density profiles for a representative system loaded with 200 MY surfactants, placed either randomly or close to the bilayer surface. We can discern from Figure 9b that the initial placement of the surfactants hardly affects their density distribution; in other words, surfactant adsorption is not kinetically driven.

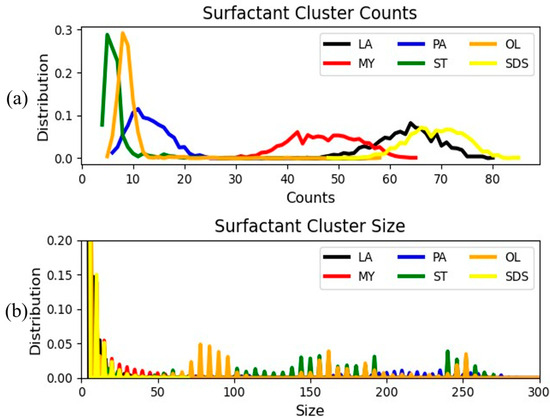

As stated earlier, the tendency of surfactants to form aggregates and, more specifically, their critical micelle concentration [13] has been shown to be one of the key factors governing their adsorption efficiency. To assess the propensity of the candidate surfactants to aggregate, a cluster analysis was performed. The minimum distance between beads of different molecules at which the molecules were considered to belong to the same cluster was set to 0.76 nm, which equals 1 DPD length unit. The minimum cluster size was set to 1, thus implying that each isolated molecule was considered to belong to a cluster. As the results for both examined concentrations exhibit very similar behavior, only the distribution of the number of clusters and cluster sizes for models containing 100 surfactants are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Distributions of (a) the number of clusters and (b) the sizes of the clusters formed by the surfactants under study. The lines are a guide to the eye.

Focusing on the top panel of Figure 10, it appears that the higher size surfactants form less clusters compared to their lower size counterparts. Specifically, stearate and oleate exhibit very similar behavior. This lies in accordance with the work of Sharma et al. [13] who report minor differences in the aggregation kinetics of the two surfactants. Furthermore, the larger size FAs (PA, ST, and OL) form bigger clusters than their smaller size counterparts, as shown in Figure 10b. This suggests that, although the larger size FAs form a small number of clusters, they have a higher tendency to aggregate. The trends detected in this figure are consistent with the earlier presented findings, demonstrating a lower adsorption tendency for the larger size FAs, contrary to shorter surfactants as laurate and SDS, that exhibit a high affinity for the lipid bilayer. The high clustering behavior of larger size surfactants also explains the large peaks in the surfactant–surfactant RDFs of these FAs, displayed in Figure 7a. In accordance with relevant experimental and simulation studies [13], the tendency of a surfactant to aggregate is inversely proportional to the magnitude of its CMC. Interestingly, SDS presents a low tendency to aggregate despite its low CMC (~8 mM) [13]. This can be attributed to its highly favorable interactions with the bilayer, as illustrated in Figure 7b.

4. Conclusions

With the aid of dissipative particle dynamics simulations, we have shed light on the adsorption behavior of anionic FA surfactants in the inner membrane of E. coli bacteria. In accordance with experimental and simulation studies, our findings demonstrate that the adsorption efficiency of the candidate surfactants is inversely proportional to their hydrophobic tail length and aggregation tendency. Moreover, our results indicate that larger surfactants prefer forming micelles even when placed initially close to the bilayer. SDS appears to exhibit the highest adsorption efficiency due to its short hydrophobic chain length and its bulky headgroup.

An atomistic simulation of such systems would require simulation times of several hundreds of ns [13,19]. Based on current supercomputing power, such simulations would require at least a week. Our simulation protocol is much faster since the adsorption runs require less than 24 h each on four CPU cores. Furthermore, the fragmentation protocol and the parameterization method manage to correctly describe the interactions among the constituent molecules. On these grounds, the adopted simulation approach constitutes a highly efficient alternative to microscopic simulations and experimental approaches as it allows for capturing the major mechanisms that govern the antimicrobial activity of surfactants and fatty acids significantly faster than lab experiments and atomistic simulations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully thanks Panos Petris, Jan van Male and Jan-Willem Handgraaf for fruitful discussions and their constructive comments on the manuscript. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ioannis Tanis was employed by the Siemens Industry Software Netherlands B.V., Pr. Beatrixlaan 800, 2595 BN Den Haag, Netherlands. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Falk, N. A Surfactants as Antimicrobials: A Brief Overview of Microbial Interfacial Chemistry and Surfactant Antimicrobial Activity. J. Surf. Deter. 2019, 22, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerklotz, H. Interactions of surfactants with lipid membranes. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 41, 205–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.B.; Yao, J.; Frank, M.W.; Jackson, P.; Rock, C.O. Membrane disruption by antimicrobial fatty acids releases low-molecular-weight proteins from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 5294–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.K.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional Biomolecules of the 21st Century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desbois, A.P.; Smith, V.J. Antibacterial free fatty acids: Activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obukhova, E.S.; Murzina, S.A. Mechanisms of the Antimicrobial Action of Fatty Acids: A Review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2024, 60, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, E.K.; East, J.M.; Jones, O.T.; McWhirter, J.; Simmonds, A.C.; Lee, A.G. Interaction of fatty acids with lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1983, 728, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, F.; Motta, P.; Barbiroli, A.; Signorelli, M.; La Rosa, C.; Janaszewska, A.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B.; Fessas, D. Influence of Free Fatty Acids on Lipid Membrane–Nisin Interaction. Langmuir 2020, 36, 13535–13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Shelley, J.C.; Klein, M.L. Molecular Dynamics Study of the Effect of Surfactant on a Biomembrane. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 5979–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Vaiwala, R.; Gopinath, A.K.; Chockalingam, R.; Ayappa, K.G. Structure of the Bacterial Cell Envelope and Interactions with Antimicrobials: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Langmuir 2024, 40, 7791–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenaillon, O.; Skurnik, D.; Picard, B.; Denamur, E. The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, W.; Khalid, S. Molecular Simulations of Gram-Negative Bacterial Membranes Come of Age. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2020, 71, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Vaiwala, R.; Parthasarathi, S.; Patil, N.; Verma, A.; Waskar, M.; Raut, J.S.; Basu, J.K.; Ayappa, K.G. Interactions of Surfactants with the Bacterial Cell Wall and Inner Membrane: Revealing the Link between Aggregation and Antimicrobial Activity. Langmuir 2022, 38, 15714–15728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laatiris, A.; El Achouri, M.; Rosa Infante, M.; Bensouda, Y. Antibacterial activity, structure and CMC relationships of alkanediyl α,ω-bis(dimethylammonium bromide) surfactants. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, T.J. Methods for screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity: A review of protocols, advantages, and limitations. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 14, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, R.W.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. Development of the CHARMM Force Field for Lipids. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B.; Venable, R.M.; Freites, J.A.; O’Connor, J.W.; Tobias, D.J.; Mondragon-Ramirez, C.; Vorobyov, I.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Pastor, R.W. Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 7830–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjevik, Å.A.; Madej, B.D.; Dickson, C.J.; Lin, C.; Teigen, K.; Walker, R.C.; Gould, I.R. Simulation of lipid bilayer self-assembly using all-atom lipid force fields. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 10573–10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jeon, T.-J. The binding and insertion of imidazolium-based ionic surfactants into lipid bilayers: The effects of the surfactant size and salt concentration. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 5725–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.S.; Parkin, J.; Khalid, S. The Free Energy of Small Solute Permeation through the Escherichia coli Outer Membrane Has a Distinctly Asymmetric Profile. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 3446–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn, K.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M. Structural Properties of the Water/Membrane Interface of a Bilayer Built of the E. coli Lipid A. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 5846–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, W.; DeVane, R.; Klein, M.L. Coarse-grained molecular modeling of non-ionic surfactant self-assembly. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 2454–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.T.; Warren, D.B.; Pouton, C.W.; Chalmers, D.K. Using Molecular Dynamics to Study Liquid Phase Behavior: Simulations of the Ternary Sodium Laurate/Sodium Oleate/Water System. Langmuir 2011, 27, 11381–11393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, G.; Klein, M.L. Coarse-grain molecular dynamics simulations of diblock copolymer surfactants interacting with a lipid bilayer. Mol. Phys. 2004, 102, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.C.T.; Alessandri, R.; Barnoud, J.; Thallmair, S.; Faustino, I.; Grünewald, F.; Patmanidis, I.; Abdizadeh, H.; Bruininks, B.M.H.; Wassenaar, T.A.; et al. Martini 3: A general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaiwala, R.; Ayappa, K.G. Martini-3 Coarse-Grained Models for the Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Outer Membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 1704–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, R.D.; Warren, P.B. Dissipative particle dynamics: Bridging the gap between atomistic and mesoscopic simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 4423–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, R.D.; Rabone, K.L. Mesoscopic Simulation of Cell Membrane Damage, Morphology Change and Rupture by Nonionic Surfactants. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Gao, L.; Fang, W. Dissipative Particle Dynamics Simulations for Phospholipid Membranes Based on a Four-To-One Coarse-Grained Mapping Scheme. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Y.; He, L.; Wang, X.; Li, S. Asymmetric Lipid Membranes under Shear Flows: A Dissipative Particle Dynamics Study. Membranes 2021, 11, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevink, G.J.A.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. Efficient solvent-free dissipative particle dynamics for lipid bilayers. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 5129–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraaije, J.G.E.M.; van Male, J.; Becherer, P.; Serral Gracià, R. Coarse-Grained Models for Automated Fragmentation and Parametrization of Molecular Databases. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 2361–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcenter Culgi, version 2211. Software for Multiscale Computational Chemistry Simulations. Siemens Digital Industries Software B.V.: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2022.

- Parchekani, J.; Allahverdi, A.; Taghdir, M.; Naderi-Manesh, H. Design and simulation of the liposomal model by using a coarse-grained molecular dynamics approach towards drug delivery goals. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.; Lyubartsev, A.P. Development of a bottom-up coarse-grained model for interactions of lipids with TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Comput. Chem. 2024, 45, 1364–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogerbrugge, P.J.; Koelman, J.M.V.A. Simulating Microscopic Hydrodynamic Phenomena with Dissipative Particle Dynamics. Europhys. Lett. 1992, 19, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, M.; Bylaska, E.J.; Govind, N.; Kowalski, K.; Straatsma, T.P.; Van Dam, H.J.J.; Wang, D.; Nieplocha, J.; Apra, E.; Windus, T.L.; et al. NWChem: A comprehensive and scalable open-source solution for large scale molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Schüürmann, G. COSMO: A new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1993, 2, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Eckert, F.; Reinisch, J.; Wichmann, K. Prediction of cyclohexane-water distribution coefficients with COSMO-RS on the SAMPL5 data set. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschwitz, J.; Olubiyi, O.O.; Hub, J.S.; Strodel, B.; Poojari, C.S. Chapter Seven-Computer simulations of protein–membrane systems. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translatioal Science; Strodel, B., Barz, B., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 170, pp. 273–403. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.C. Molecular dynamics simulations at constant pressure and/or temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 2384–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraaije, J.G.E.M.; van Male, J.; Becherer, P.; Serral Gracià, R. Calculation of Diffusion Coefficients through Coarse-Grained Simulations Using the Automated-Fragmentation-Parametrization Method and the Recovery of Wilke–Chang Statistical Correlation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, P.P.; Steim, J.M. Physical properties of fatty acyl-CoA. Critical micelle concentrations and micellar size and shape. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 7573–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, W.U.; Jain, A.K. Electrometric determination of critical micelle concentration of soap solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interf. Electrochem. 1967, 14, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).