Abstract

Slope failures frequently occur during rainfall, earthquakes, and long-term weathering, and reinforcing bar insertion is widely used worldwide to prevent such failures. In this method, steel bars are installed in pre-drilled holes and bonded to the ground with grout, with a pressure plate resisting deformation; however, tensile forces generated during slope movement may crack the hardened grout and reduce performance. To address this issue, we propose an Early-stage Prestressed Reinforcing Bar Insertion Method, in which tensile load is applied to the bar before grout hardening. Grout is injected while maintaining tension, allowing the bar to remain prestressed after construction and inducing compressive stress in the grout, which is expected to improve resistance against tensile loading. A field construction test and numerical finite-element analysis were conducted to verify performance. The test confirmed constructability within half a day and retained tensile force of 42 kN after 30 days. The numerical model reproduced measured axial forces and indicated that the hardened grout remained in compression, with an average compressive stress of 3680 kN/m2. These results demonstrate that prestressing can enhance grout tensile resistance. The method shows promise for future application and potential extension to similar anchoring systems.

1. Introduction

Numerous slope failures of natural and cut slopes have been reported as a result of frequent earthquakes and heavy rainfall events in the world [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Among various countermeasures applied to rock-based slopes, the reinforcing bar insertion method is one of the most common techniques. In this method, a steel bar is inserted into a pre-drilled hole, grouted to integrate it with the surrounding ground, and fitted with a pressure plate at the bar head to stabilize the slope. Because the construction technique has been well established, it has been widely applied and is considered to provide sufficient stabilization performance [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. A mixture of general-purpose cement and admixture is used for the grout, and it takes approximately 10 h to solidify. Since the reinforcing bar initially carries almost no axial force immediately after construction and develops tensile force only when the slope begins to move, it cannot restrain the small initial deformation.

A construction method similar to the reinforcing bar insertion method is the rockbolt method. For rockbolts, it is common practice to apply tension after installation, and numerous studies have investigated this approach [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Rashedi, M. M. reported that pre-tensioned rockbolts enhance confinement of bedding rock layers, activate friction before sliding, and reduce displacement more effectively than passive bolts. This study analytically evaluates bolt contribution at discontinuities, considering joint roughness, bolt inclination, pre-tension, and rock strength, and concludes that pre-tensioned bolts are especially effective when the surrounding rock or grout is strong [34]. Ranjbarnia, M. reported that pre-tensioning increases confinement and shear resistance prior to sliding. A simplified analytical model incorporating axial and shear force development is presented, along with a 3D numerical analysis for plastic behavior. The findings show that pre-tensioning and joint roughness significantly improve sliding resistance, particularly in high-strength rock slopes [35].

If tensile load could also be applied to the reinforcing bars after construction in reinforcing bar insertion works, as in the case of rockbolts, the pressure plate would press against the slope, which could contribute to suppressing the initial displacement. However, there are few studies or construction cases in which the load is applied after installation. NCHRP Report 701 reported that reinforcing bar insertion works are generally passive and not post-tensioned; there have been a few special cases in which light tension was applied to the upper nails to control deformation [36]. In the case of reinforcing bar insertion works, applying load after construction may cause damage to the hardened grout near the bar head.

Therefore, this study proposes the “Early-stage Prestressed Reinforcing Bar Insertion Work,” which aims to introduce tensile force into the bar without causing damage to the hardened grout. This method involves continuously applying tensile load to the reinforcing bar during the period in which the grout is injected and allowed to harden. It is an original technique proposed and only one prior study exists on a similar concept by the authors [37]. This approach prevents a concentrated load from acting locally on the head of the hardened grout. In addition, as a reaction to the tensile load applied to the bar, a compressive load acts on the grout. When large deformations occur in the slope due to events such as earthquakes or heavy rainfall, significant tensile loads may act on the grout; however, in this method, the grout remains in a compressed state at the initial stage, providing enhanced resistance against tensile loading.

A research flowchart in this paper is shown in Figure 1. The methodology, including the structure and construction procedure of the proposed method, is described in Section 2. A field construction test of the proposed method was carried out on an actual slope in Section 3. Furthermore, to examine the mechanical behavior observed during the test, a numerical back-analysis using the finite element method was conducted based on the measured data in Section 4. Finally, the findings and future challenges are summarized and discussed in Section 5.

Figure 1.

Research flowchart.

2. Materials and Methods

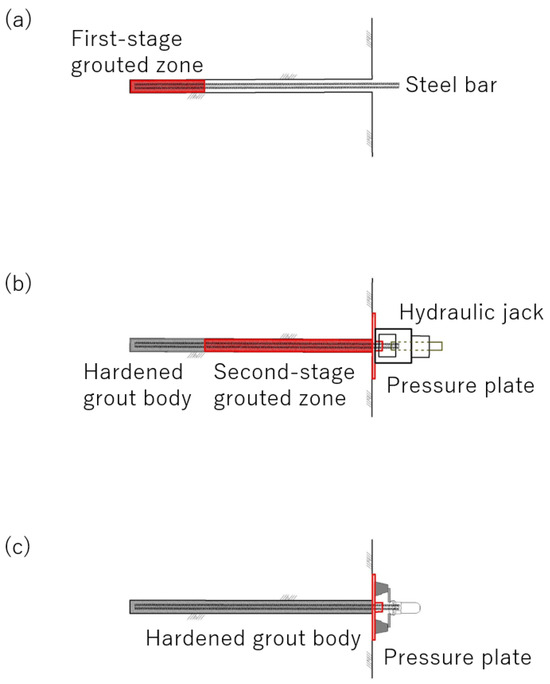

The reinforcing material and construction procedure used in “Early-stage prestressed reinforcing bar insertion method” are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Procedure of the Early-stage Prestressed Reinforcing Bar Insertion Method. (a) Insert the steel bar and allow the first-stage grouted zone to harden. (b) While tensioning the steel bar, allow the second-stage grouted zone to harden. (c) Fix the pressure plate and remove the jack.

Similar to the conventional reinforcing bar insertion method, a steel bar is first inserted into a pre-drilled hole, and the tip portion is bonded to the ground by primary grout injection. After the tip grout has hardened, a tensile force is applied to the steel bar using a jack, while the remaining portion around the bar is grouted and bonded to the surrounding ground by secondary injection. Once the surrounding grout has hardened, the bar head is connected to the pressure plate, and the jack load is released to complete the construction. In this method, it is desirable for the grout to harden rapidly because the reinforcing bar must be kept under tension until the grout has fully solidified. Therefore, a fast-setting grout material (i.e., super rapid-hardening mortar) is used instead of ordinary grout.

At this stage, the reinforcing bar retains an elastic compressive force, which not only restrains the ground surface through the pressure plate but also induces a compressive state in the hardened grout body. During subsequent slope deformation, tensile loads act on both the steel bar and the hardened grout due to the movement of the pressure plate. Because the grout body is initially under compression due to prestress, it is expected to exhibit higher strength against tensile loading. If this method can be fully established, technological expansion to similar techniques—such as anchor works—can also be expected.

3. Construction Test

The field construction test was conducted on a natural slope located in Sanda City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. The testing period was one month, from July 1 to July 31.

3.1. Test Conditions

3.1.1. Climatic Conditions

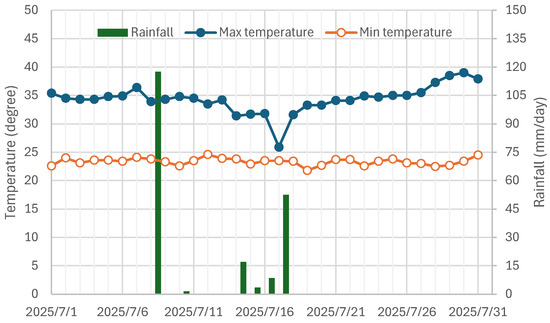

The maximum and minimum temperatures and the daily precipitation during the testing period are shown in Figure 3. As it was midsummer, the daytime maximum temperature was approximately 35 °C, while the minimum was about 24 °C. Around July 8 and July 17, the precipitation increased due to the approach of a typhoon.

Figure 3.

Climatic conditions.

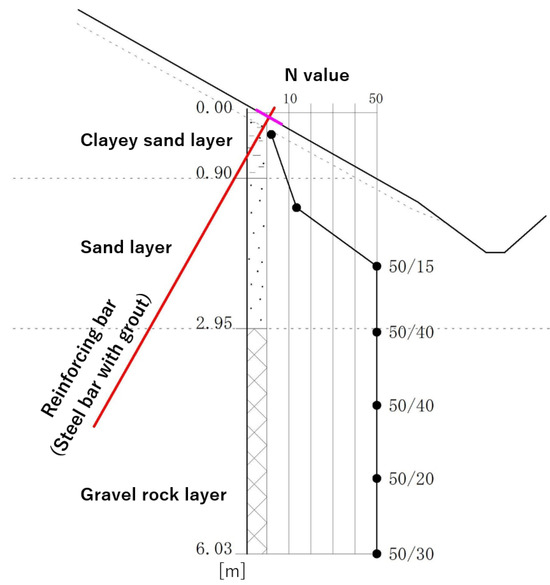

3.1.2. Ground Conditions

A cross-section and a soil profile of the test ground are shown in Figure 4. The slope inclination is 35°. The surface layer consists of sandy clay with N-values ranging from 2 to 13. Taking the test location as the reference point, the soil at depths of 1 to 3 m is sandy soil with N-values between 13 and 50, while the layer below a depth of 2.95 m is gravel rock with N-values exceeding 50. The groundwater table is located at a depth of −2.08 m. The reinforcing bar, which consists of a steel bar, grout and pressure plate, was installed approximately perpendicular to the slope surface under these ground conditions.

Figure 4.

Soil profile of the test ground.

3.1.3. Reinforcing Bar Material

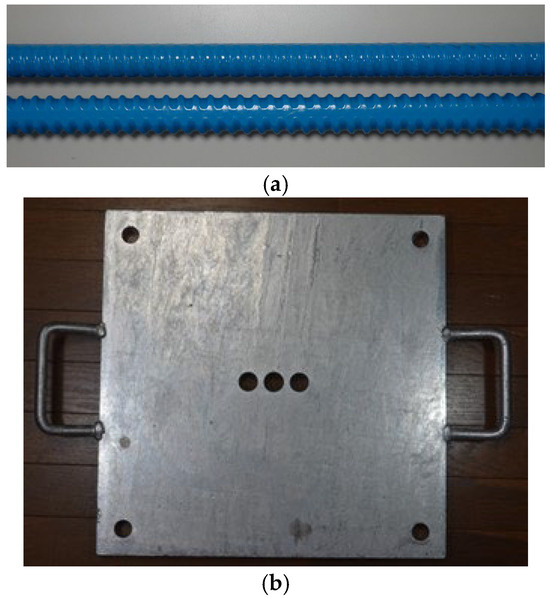

The materials used in the reinforcing bar—namely the steel bar, grout, and pressure plate—are described below. The steel bar employed was an AG Non-Slip EP bar (Figure 5a) [38,39,40,41], with a length of 5 m and a diameter of 19 mm. This bar is a deformed steel bar (SD345) coated with a high-adhesion type epoxy resin for corrosion protection. The grout injected into the borehole consisted of ultra-rapid-hardening cement (Haitascon Cement) with a water–cement ratio of 30%, to which 1.3% of SikaCem admixture was added. Preliminary tests in air confirmed that solidification was completed in approximately 3 h. Unconfined compression tests were conducted on a total of 14 specimens, and compressive strengths ranging from 18,000 to 25,000 kN/m2 were obtained. However, since these experiments were conducted in air, further investigation is required to understand the properties of the hardened grout body in the ground. A steel pressure plate measuring 400 mm × 400 mm × 20 mm in thickness was used (Figure 5b). Three holes were provided at the center of the plate: one for the steel bar to pass through and be fastened with a nut, and two for the injection pipes to pass through during grout placement.

Figure 5.

Reinforcing bar material. (a) Steel bar. (b) Pressure plate.

3.1.4. Test Procedure

A drilling machine (SD-type) was installed on the slope, and a borehole with a diameter of 65 mm was excavated. The steel bar was then inserted into the hole, followed by grout injection into the primary grouting section, as shown in Figure 2a. During grout injection, the flow rate and pressure were controlled using a flow management meter at intervals of 1 L for flow rate and 10 kPa for pressure.

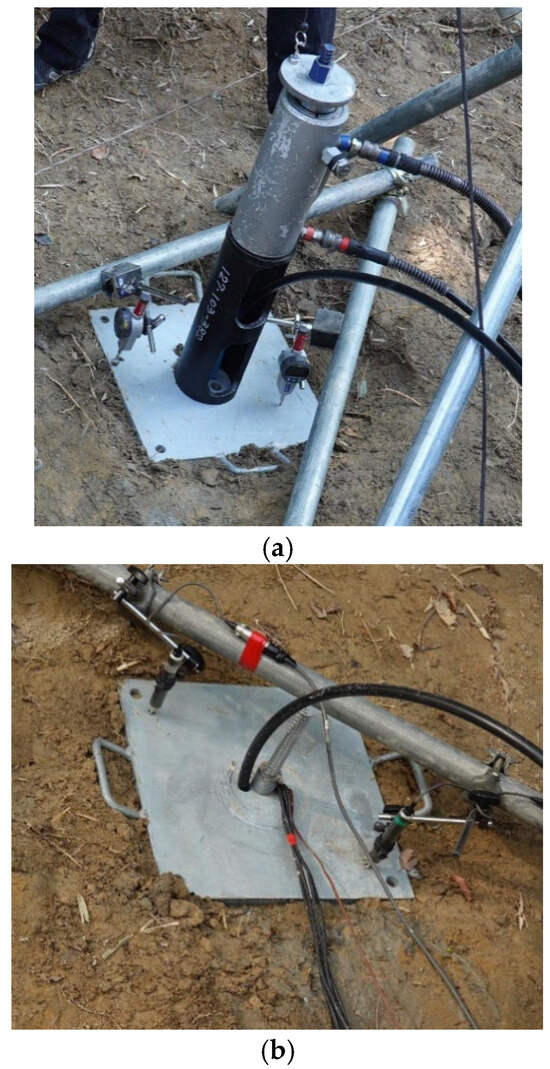

Approximately 3 h after the injection, when the grout was presumed to have hardened, the process of applying tensile force to the steel bar was initiated. First, a reaction frame was then constructed above the pressure plate, and a tensile force of approximately 42 kN was applied to the bar head using a hydraulic jack while maintaining the grip on the bar (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Construction situation, (a) Tensile loading using a jack, (b) After construction.

Subsequently, grout was injected into the secondary grouting section, as shown in Figure 2b. About 3 h after the secondary injection, the grout was judged to have hardened. A ram chair was used to secure a space between the hydraulic jack and the pressure plate, after which the steel bar and the pressure plate were manually fastened with bolts. Finally, the hydraulic jack and the reaction frame were removed to complete the construction (Figure 6b).

Strain gauges were attached along the bar at distances of 0.5 m (Point A), 1.1 m (Point B), 1.75 m (Point C), and 3.0 m (Point D) from the bar head. Measurements were continuously recorded during construction and for 30 days thereafter.

3.2. Test Results

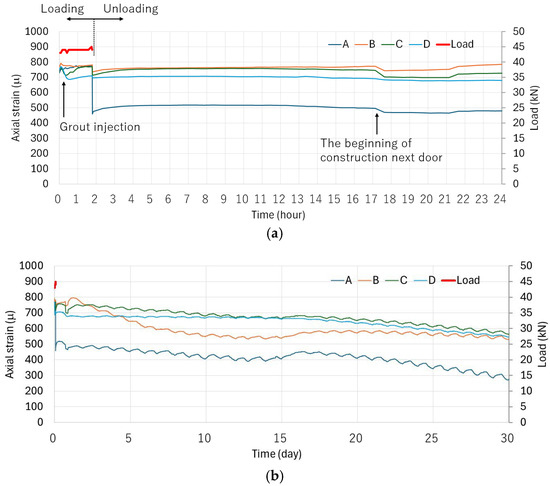

The measurement results of the tensile load applied by the hydraulic jack and the axial strains generated in the steel bar are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a,b present the results for the short term (1 day) and long term (30 days) measurements, respectively.

Figure 7.

Axial strain and tensile load of the steel bar, (a) Short term (1 day), (b) Long term (30 days).

As shown in Figure 7a, the strain increased with the start of tensioning and reached approximately 700–800 µ. This value was in good agreement with the calculated strain of about 750 µ, which was estimated from the applied tensile load by the jack. During grout injection under a maintained tensile load, no significant change in strain was observed, indicating that the reinforcing bar remained stably prestressed. Although the hydraulic jack was removed at approximately t = 2 h after measurement started, no marked change in strain was observed at Points B–D. The reinforcing bar maintained its tensile state for 24 h, allowing the method to perform as intended. In contrast, the strain at Point A decreased by about 300 µ. This behavior will be examined in the next chapter through numerical analysis.

Afterward, the strains remained nearly constant up to t = 24 h. A slight decrease in strain was observed around t = 18 h, which is presumed to have been caused by the construction of another reinforcing bar insertion 2 m away. When the measurements were continued up to t = 30 days, Figure 7b shows that the strains at Points A–D gradually decreased over time by 5% to 15%. Small daily fluctuations were also observed, which are considered to result from temperature variations between day and night. Around t = 16 days, the strain temporarily increased, likely due to changes in ground conditions caused by rainfall, as shown in Figure 3. Measurements were discontinued after t = 30 days, and it remains unclear whether the strain would continue to decrease or converge to a constant value thereafter. This issue is also examined in the following chapter through numerical analysis.

In this test, only one specimen was used and strain was measured at only four points; therefore, it will be necessary to increase the number of specimens and measurement points in future tests to improve the reliability.

4. Numerical Analysis

To reproduce the conditions of the construction test and to investigate the mechanism in greater detail, a back-analysis of the construction test was conducted using the 3-dimensional finite element analysis tool “PLAXIS 3D” version 2024.3.

4.1. Analytical Conditions

4.1.1. Model

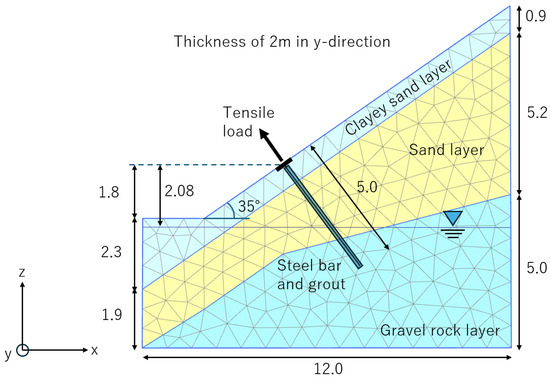

The analytical model together with the coordinate system is shown in Figure 8. The model dimensions are 12 m in the x-direction, 2 m in the y-direction, and 12.1 m in the z-direction. The model consists of 19,509 nodes and 13,005 elements, using a tetrahedral finite element mesh. It was assumed that the reinforcing methods are arranged at 2 m intervals in the y-direction, and the center of the modeled reinforcing element was placed at y = 1 m. Regarding the boundary conditions, as shown in Figure 8, the bottom boundary was fixed in the x, y, and z directions, the side boundaries in the x-direction were fixed against x-direction displacement, and the side boundaries in the y-direction were fixed against y-direction displacement. Groundwater level was set at 2.08 m below the reinforcing bar head, and the soil above this level was modeled as unsaturated, while the soil below it was modeled as saturated.

Figure 8.

Analytical model (Unit: m).

Based on the soil profile obtained from the standard penetration test, the ground was divided into three layers from top to bottom: a clayey sand layer, a sand layer, and a gravel rock layer, as illustrated in Figure 8. These soil layers were modeled as elastic–perfectly plastic materials, and their physical parameters are listed in Table 1. The unit weight was set to typical values, while the Young’s modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle were estimated from the N-values referring to Ameratunga, J. et al. [42]. These values are only estimates and have a wide possible range; therefore, material property tests will be required to improve the accuracy of the analysis. Only the Young’s modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle of the surface clayey sand layer were obtained from a direct shear test.

Table 1.

Soil parameters.

The material parameters of the reinforcing components are summarized in Table 2. The steel bar and the pressure plate were modeled as elastic materials without yielding, whereas the improved ground around the grout was modeled as an elastic–perfectly plastic material. Only the simple model was applied, and thus issues remain regarding the validity of the modeling.

Table 2.

Reinforcing material parameters.

The steel bar was represented by embedded beam elements, which interact with the surrounding improved ground through interface springs that transmit normal and shear forces along the interface. The mechanical properties of the improved ground were set to typical values for concrete, and the tensile strength was assumed to be one-fifteenth of the compressive strength. The pressure plate was modeled using plate elements, and normal and shear interactions with the surrounding ground were represented through interface elements placed on its surfaces. The dimensions of these reinforcing components were the same as those described in the previous chapter.

4.1.2. Numerical Procedure

The analysis was carried out in the following six steps:

Step 1: Calculate the initial stress state with only the steel bar installed.

Step 2: Replace the material properties of the ground in the primary grouting section with those of the improved ground.

Step 3: Apply a tensile force of 42 kN to the head of the steel bar.

Step 4: Replace the material properties of the ground in the secondary grouting section with those of the improved ground.

Step 5: Install the pressure plate and rigidly connect its center to the steel bar.

Step 6: Release the tensile force applied to the head of the steel bar.

4.1.3. Cases

Four analysis cases were conducted. Case 1 was defined as the basic condition, and Cases 2 to 4 were performed to further investigate the influence of various factors.

Case 1: Same as the condition described above. This is a back-analysis of the construction test.

Case 2: To improve the accuracy of the analysis, the elastic modulus of the improved ground within the clayey sand layer was reduced to one-twentieth of that used in Case 1.

Case 3: No tensile force was applied (Step 3 was omitted). This corresponds to the conventional, commonly used rein-forcing bar insertion method.

Case 4: The order of the analysis steps was changed so that the tensile force was applied after the secondary grout injection (Steps 3 and 4 were interchanged). As described in Chapter 1, this assumes that a tensile load is applied to the reinforcing bar after construction is completed.

4.2. Analytical Result

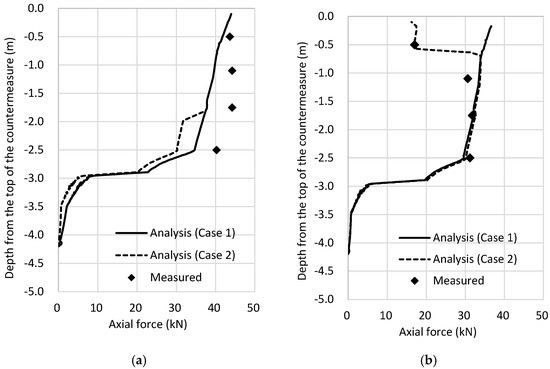

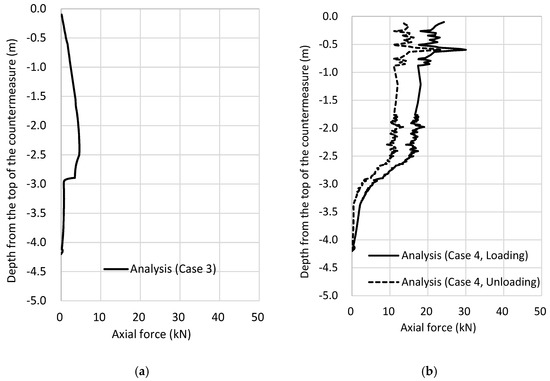

4.2.1. Axial Force in Steel Bar

The axial forces of the steel bar for Cases 1 and 2 are shown in Figure 9. Figure 9a,b show the loading condition (Step 5) and unloading condition (Step 6), respectively, together with the field measurements. The axial forces in the construction test were calculated from the measured axial strains, with the tensile direction taken as positive. For Figure 9a, the measured and numerical results at Point A (the nearest to the ground surface) were almost identical. At Points B to D, the difference between the measured and calculated values was within approximately 10–20%, showing good overall agreement. For Figure 9b, the measured values at t = 30 days were used for comparison. Although the results at Points B to D showed good agreement between the measurements and Case 1, the measured value at Point A was significantly smaller, resulting in a noticeable discrepancy. Considering the possibility that the grout near Point A had not sufficiently hardened during the field test, an analysis (Case 2) was also conducted, in which the elastic modulus of the improved ground in the clayey sand layer (0.74 m in length) was reduced to one-twentieth of the original value. This modification resulted in good agreement between the measured and numerical results at Point A, while also maintaining reasonable agreement at Points B to D. The unusually small measured strain at Point A could also be attributed to other factors, such as the relatively low stiffness of the clayey sand layer or insufficient fixation between the pressure plate and the steel bar. Nevertheless, the numerical analysis suggests that insufficient grout hardening may have been one of the contributing causes. Moreover, the analysis result of Step 6 converged to a stable state as a structural system, and the measured data were generally consistent with this converged result. Therefore, it is inferred that the measured values at t = 30 days were close to the stabilized condition.

Figure 9.

Analytical result of axial forces in the steel bar for Cases 1 and 2, (a) Step-5: Loading, (b) Step-6: Unloading.

The axial forces of the steel bar for Cases 3 and 4 are shown in Figure 10a,b, respectively. For Figure 10a, it is evident that when no tensile load is applied, the axial force in the reinforcing bar becomes very small. This confirms that, in conventional reinforcing-bar insertion methods, no tensile load is mobilized in the bar. For Figure 10b, when a tensile load is applied after grout hardening, a certain level of tensile force is generated in the bar; however, it remains approximately more than 50% smaller than that achieved by the proposed method. These results indicate that the proposed method enables tensile load to be efficiently introduced and maintained in the reinforcing bar.

Figure 10.

Analytical result of axial forces in the steel bar for Cases 3 and 4, (a) Case 3, (b) Case 4.

From these results, it was confirmed that the residual tensile force in the Early-stage prestressed reinforcing bar insertion method can be quantitatively evaluated using the finite element method.

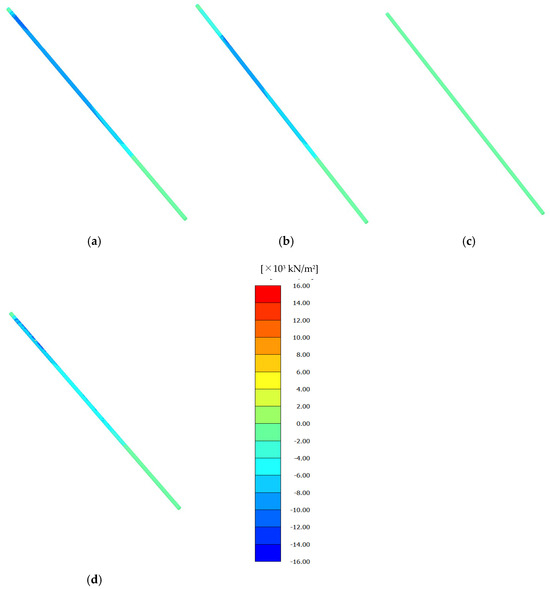

4.2.2. Axial Stress in the Hardened Grout Body

Figure 11 shows the longitudinal axial stress contours of the hardened grout body after the release of tensile load for Cases 1–4. The blue color indicates a compressive state. Table 3 shows the average compressive stress of the hardened grout and the apparent increase ratio of tensile resistance.

Figure 11.

Axial stress contour of the hardened grout body, (a) Case 1, (b) Case 2, (c) Case 3, (d) Case 4.

Table 3.

Summary of the analysis results for the hardened grout.

In Case 1, the hardened grout is in a state of compression, with particularly high compressive stresses developing in the vicinity of the head. Under the present analysis conditions, assuming that the tensile strength of the hardened grout is one-tenth of its compressive strength, it is estimated to be approximately 2000 kN/m2; the apparent load-bearing capacity increases by approximately 199% on average. In Case 2, although the compressive stress near the bar head is relatively small, the hardened grout is generally in a compressive state. Based on the previously discussed axial force results of the reinforcing bar, Case 2 is considered to most closely represent the field construction conditions. In the hardened grout body, an apparent tensile resistance increase of approximately 184% was observed. In Case 3, since no compressive prestress was applied, almost no stress developed in the hardened grout body. In Case 4, an average compressive stress of 2015 kN/m2 was generated. This value is 50% and 45% lower than those in Case 1 and Case 2, respectively.

These results indicate that in the early-stage prestressed reinforcing bar insertion method, the hardened grout body can be placed under a higher compressive state, which is expected to enhance its strength against tensile loading induced by slope deformation. Although further improvement in the strength of the hardened grout body may be expected by increasing the applied tensile load, excessive loading could cause damage to both the reinforcing bar and the grout body. Therefore, it is considered that the apparent increase in tensile resistance should reasonably be limited to approximately 199%, as indicated previously. It should be noted that this represents the average value for the entire hardened grout body, and excluding the lower portion, an improvement in strength of more than 199% can be expected.

4.2.3. Evaluation of the Present Analysis in Light of Previous Studies

In the present analysis, a simplified modelling approach was adopted in which the ground and hardened grout were represented by the Mohr–Coulomb model, while the reinforcing bars and bearing plates were assumed to behave elastically. However, Habtamu Kefyalew Molla et al. have demonstrated that axial force predictions can vary substantially depending on the choice of soil constitutive model (e.g., Mohr–Coulomb versus Hardening Soil). This suggests that, also in the present study, further refinement of the constitutive modelling for the ground and the hardened grout is necessary to improve analytical accuracy [43].

The slope investigated in this study has an inclination of 35°, at which it remains stable; consequently, the installation of reinforcing bars (soil nails) does not induce any ground deformation. Therefore, the initial concept of suppressing early-stage slope displacement could not be examined in this study. For example, M. Zhang et al. conducted a deformation analysis using three-dimensional FEM by applying external loads to the slope. In the future, similar deformation-based investigations will be required for the proposed method presented in this study [44].

5. Conclusions

A field construction test and numerical analysis (finite element analysis using PLAXIS 3D) were conducted for the early-stage prestressed reinforcing bar insertion method, in which a tensile force is applied to the steel bar before grout hardening. The main findings obtained from this study are summarized as follows:

(1) The field construction test confirmed that the entire construction procedure—including the two-stage grout injection and loading/unloading using a hydraulic jack—can be successfully carried out, and that the early-stage prestressed reinforcement bar insertion method can be installed within approximately half a day. Furthermore, it was verified that the tensile force in the steel bar did not disappear for 30 days after unloading the jack load at the bar head.

(2) The numerical analysis successfully reproduced the measured axial forces in the steel bar during tensile loading. After unloading, the analysis also reproduced the measured axial forces with reasonable accuracy. Although a discrepancy was observed near the ground surface, assuming insufficient grout hardening and reducing the stiffness of the improved ground significantly improved the accuracy of the reproduced results.

(3) The field measurements were continued for 30 days, and the long-term change in the tensile force of the bar beyond this period remains unknown. However, since the numerical results converged to a stable structural state and were in good agreement with the measured data, it is considered that the measured values at 30 days were close to the converged state.

(4) The numerical analysis showed that the hardened grout remained in a compressive state even after the tensile load at the bar head was released. When slope deformation occurs, tensile forces act on both the reinforcing bar and the hardened grout due to the movement of the pressure plate; however, by applying the proposed method, compressive pre-stress is introduced into the hardened grout, and its resistance to tensile loading is expected to improve by approximately 10%. Although increasing the prestressing load may lead to further improvement in strength, possible damage to the reinforcing bar and the grout must also be considered.

(5) The field construction test was limited to a 30-day measurement period, and the converged value of the axial force could not be confirmed. For future studies, long-term monitoring will be necessary to evaluate the time-dependent behavior of axial force, as well as the long-term performance of the reinforcing system, including steel corrosion and grout deterioration.

Funding

This work was supported by Chouju Reinforced Soil Co., Ltd. to whom we express our deep gratitude.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as a collaborative research project with Chouju Reinforced Soil Co., Ltd. The author would like to express their sincere gratitude for their valuable cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Kakuta Fujiwara have received research grants form company Chouju Reinforced Soil Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Chiaro, G.; Singh, J.; Kiyota, T.; Higuchi, Y. Earthquake-induced flow-type slope failure: The 2016 Takanodai landslide, Japan. Geosciences 2022, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Moriguchi, S.; Nakamura, S.; Matsushima, T. Numerical analysis of the 2021 Atami debris flow using a depth-integrated model. Landslides 2024, 21, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, J.; Ogura, M.; Sassa, K. Shallow and deep-seated landslide differentiation using support vector machines: Chuetsu area, Japan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2015, 26, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y.; Sassa, K.; Fukuoka, H.; Wakai, A.; Wakai, F. Landslides associated with spheroidally weathered mantle rocks during Typhoon Talas (2011) in the Kii Peninsula. Eng. Geol. 2019, 261, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawajiri, S.; Wakai, A.; Uchida, T.; Furuya, G. Geotechnical characteristics and seismic stability of slope failures in Atsuma-town, Hokkaido. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, S.; Miura, S.; Yamazaki, H. Rainfall-induced failures of volcanic slopes subjected to freeze–thaw in Hokkaido. Soils Found. 2013, 53, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, S.; Miura, S.; Uchida, T.; Yamazaki, H. Slope failures/landslides over a wide area in the 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake. Soils Found. 2019, 59, 2376–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, M.; Higuchi, Y.; Ono, Y. Evaluating earthquake-induced widespread slope failure hazards using an AHP–GIS combination. Nat. Hazards 2023, 117, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Okamoto, T. Large deep-seated landslides controlled by geologic structures in the Chichibu belt, Japan. Eng. Geol. 2015, 193, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, G.; Sassa, K.; Takara, K. Distribution and mobility of coseismic landslides triggered by the 2018 Hokkaido Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Saito, H.; Nishimura, T.; Okamoto, T. Landslide disasters in Ehime Prefecture resulting from the July 2018 heavy rain in western Japan. Soils Found. 2019, 59, 2405–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, N. Atami landslides 2021, Japan: Landfill issues and slope failure mechanisms. Saf. Extrem. Environ. 2025, 4, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; Yoshida, M.; Uchimura, T. Variation in the frequency and characteristics of landslides in Japan. Catena 2025, 238, 109812. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, Q.; Sassa, K.; Takara, K. Preliminary investigation of the 20 August 2014 debris flows triggered by a severe rainstorm in Hiroshima City, Japan. Geoenviron. Disasters 2015, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R. Investigation of seismic damage to existing buildings by using remotely observed images. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 161, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Wang, L. Study on the effectiveness of reinforcing bar insertion work with a circular pipe. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q. Loose fill slope stabilization with soil nails: Full-scale test. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2008, 134, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Nakagawa, A.; Nakanishi, H. Soil-nail pull-out interaction in loose fill materials. Int. J. Geomech. 2006, 6, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaideen, S.M.; Goh, S.-H.; Wong, K.S. Laboratory study of soil–nail interaction in loose, completely decomposed granite. Can. Geotech. J. 2004, 41, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.-J.; Li, X.; Wong, L.S.; Cheung, R.W.M. Influence of degree of saturation on soil nail pull-out resistance in compacted completely decomposed granite fill. Can. Geotech. J. 2007, 44, 1314–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, C.Y.; Ng, C.W.W.; Sun, H.W. Influence of soil nail orientations on stabilizing mechanisms of loose fill slopes. Can. Geotech. J. 2013, 50, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, C.Y.; Ng, C.W.W.; Sun, H.W. Numerical experiments of soil nails in loose fill slopes subjected to rainfall infiltration effects. Comput. Geotech. 2005, 32, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J. Nail reinforcement mechanism of cohesive soil slopes under earthquake conditions. Soils Found. 2010, 50, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkiti, C.O.; Long, M. Performance of soil nails in Dublin glacial till. Can. Geotech. J. 2008, 45, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdandoust, M. Seismic performance of soil-nailed walls using a 1g shaking table. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. Analytical model of fully grouted rock bolts subjected to tensile load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 45, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.F.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Analytical analysis of the full-range behaviour of grouted rockbolts based on a tri-linear bond–slip model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, L.B.; Cabrera, J.; Segura, F. A new analytical solution to the mechanical behaviour of fully grouted rockbolts subjected to pull-out. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2653–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenevin, I.; Hurtrez, J.-E.; Binet, S.; Vandembroucq, D. Laboratory pull-out tests on fully grouted rock bolts and numerical interpretation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 9, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymen, A.; Karakus, M.; Canakci, H.; Pamukcu, C. Effect of grout strength on the axial stress distribution of fully grouted rock bolts. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 76, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Li, Z. Mechanical behaviour of fully grouted GFRP rock bolts. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 79, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Stillborg, B. A rock bolt and rock mass interaction model. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1999, 36, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Song, L. Study on grout cracking and interface debonding of rockbolt-grouted system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, M.M.; Ranjbarnia, M. Analytical simulation of passive and pre-tensioned grouted rockbolts in bedding rock slopes. Amirkabir J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 52, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbarnia, M.; Rashedi, M.M.; Dias, D. Analytical and numerical simulations to investigate effective parameters on pre-tensioned rockbolt behavior in rock slopes. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. NCHRP Report 701: Proposed Specifications for LRFD Soil-Nailing Design and Construction; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mita, K.; Okuzono, S. Proceedings of the 12th Symposium on Sediment-Related Disasters; Japan Society of Civil Engineers: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Society of Civil Engineers. Design and Construction Guidelines for Reinforced Concrete Structures Using Epoxy-Coated Reinforcing Bars; Concrete Library No. 112; JSCE: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M.; Takewaka, K. Fundamental study on various properties of corrosion-resistant reinforcing bars coated with a new resin method. Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2009, 31, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashiguchi, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Takewaka, K.; Akira, Y.; Moniwa, M. Examination on Applying of Thermal Sprayed Galvanic Anode Cathodic Protection System for Reinforced Concrete Structure. In Advances in Construction Materials: Proceedings of the ConMat’20; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1097–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, K.; Ishida, T.; Akira, Y.; Takewaka, K. A study on adhesion and fatigue characteristics of reinforcing bars coated with PVB resin and silica sand. Adv. Constr. Mater. (ConMat’20) 2020, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameratunga, J.; Sivakugan, N.; Das, B.M. Correlations of Soil and Rock Properties in Geotechnical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, H.K.; Gebregziabher, H.F. Numerical Study of Soil–Nail Structural Elements Performance Using Different Soil Constitutive Models. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2025, 4602104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, E.; Chen, Z. Ground movement analysis of soil nailing construction by three-dimensional (3-D) finite element modeling (FEM). Comput. Geotech. 1999, 25, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).