Abstract

Soft and weak rocks present challenges for construction activities in various environments. Their genetic origin, geological and tectonic evolution, and exposure to atmospheric conditions control their weathering and degradation over time. Therefore, a sound characterization of the associated rock parameters is essential. Numerous tests have been developed and standardized or defined in recommendations to assess various geomechanical, petrological, and mineralogical parameters. However, these tests are still subject to modification or extension to address project-specific issues. Additionally, standardized tests do not consider regional climatic conditions that may affect weathering, meaning they do not reflect the degradation behavior that is observed in the field. The present study investigates the slaking resistance and degradability of a range of soft rocks. The workflow of widely used tests is employed to evaluate their representativeness for different rock types in practical applications. Depending on their genetic origin and mineral composition, fabric alterations affect the rate and style of rock disintegration differently. Soft sedimentary rocks react already to static slaking, i.e., water immersion, whereas crystalline and grain-bound rocks slake under dynamic action while undergoing attrition in a rotating slake durability drum. Zones of structural weakness, such as foliation planes, are responsible for material removal in the latter; sedimentary rocks, on the other hand, are subject to surface particle separation (suspension) and suction due to the presence of clay minerals. This study presents an approach that combines the results of several routine tests to help identify and refine the slaking susceptibility of different rock types. A routine for inspecting and documenting the evaluated slaking characteristics for infrastructure maintenance is proposed, and the wider implications in light of climate change are discussed. Some limitations of the transferability of laboratory values to field sites still have to be evaluated and validated in the future.

1. Introduction

1.1. Thematic Background

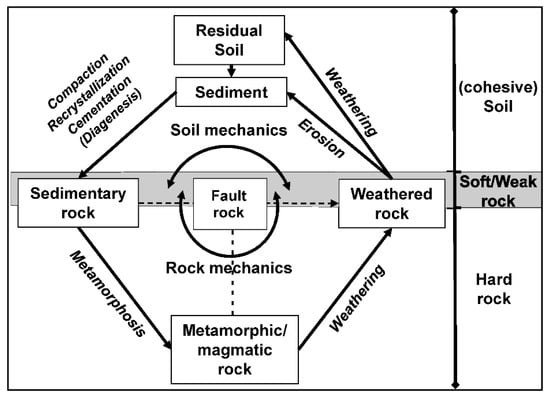

Slaking resistance, also known as durability, is an important rock property that affects the long-term stability of slopes and excavations [1,2]. Slaking is a disintegration process that is triggered by a water–rock interaction, resulting in cracks or flaking of exposed rocks. The ability of rocks to resist this type of water-induced degradation is referred to as slake durability [3]. Rocks with low slaking resistance are typically classified as soft or weak and originate from various lithologies, formation environments, and processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic sketch of formation and processes associated with weak/soft rocks (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Dobereiner and De Freitas (1986) [4]. Copyright 2001, Emerald Publishing Limited).

The terms “soft” and “weak” are often used interchangeably [4,5]. However, the definition may differ depending on the discipline in which they are studied. In rock mechanics, any rock with an uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of less than 25 megapascals (MPa) is commonly referred to as soft or weak rock [5,6]. This includes weathered crystalline rocks, early diagenetic sedimentary rocks, and highly porous volcanic rocks. ISO 14689 [7] proposes a UCS of less than 0.6 MPa to define soil. Mining engineers and engineering geologists define soft rocks as those that can be easily excavated with minimal to moderate tool wear [8,9]. The inherent rock properties that control excavatability and tool wear are rock fabric strength and abrasiveness, which are due to cohesive grain bonding and mineralogical composition, respectively [10,11]. Additional challenges associated with soft rocks include clogged discs in tunnel boring machines (TBMs) [12] and blocked TBMs in soft ground [13].

An alternative approach for the characterization of weak rocks is to assess material behavior in the presence of water [14,15]. These rocks react under atmospheric conditions with a rapid loss of their internal, mostly diagenetic, bonding and strength. This disintegration process is triggered by changes in water content, caused by repeated wetting and drying cycles or seasonal frost and thaw cycles. Eventually, these rocks are gradually converted into different types of soil [16]. Metamorphic and igneous rocks affected by weathering or tectonic shearing can also exhibit weak rock characteristics by losing internal grain bond strength and undergoing mineral alterations, such as clay mineral neoformations [17,18,19].

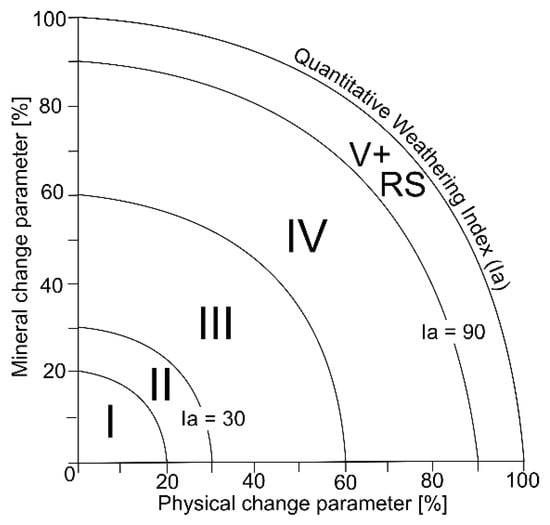

Although any type of rock can degrade due to weathering, weathering assessments [6] do not provide information on slaking behavior [20]. Knopp et al. [21] demonstrated that mineralogical changes occur during the initial stage of soft rock weathering when the rock’s microfabric remains intact. This is followed by an increase in porosity as weathering continues. The first stage is dominated by chemical weathering, while the second stage is characterized by physical weathering. Progressive weathering is characterized by an increase in both secondary mineral neoformation and fracturing (Figure 2), as well as a decrease in UCS [22]. However, quartz-rich rocks may exhibit little mineral neoformation and a fresh character even in advanced states of weathering, a phenomenon that cannot be detected by mineralogical analysis alone. Ceryan et al. [23] related the slake durability index to physio-mineralogical parameters obtained by P-wave velocity measurements to address this issue.

Similar processes occur in sedimentary rocks stored in water for up to 12 months, where microcracks coalesce, clay mineral structures break down due to ion exchange and leaching, and grain bonds weaken due to particle disintegration, eventually leading to rock breakage [24]. Some weak rocks exhibit a peculiarity: their strength is reversible depending on their water content and consistency, which gives them plastic behavior [25].

Site and laboratory tests are commonly used to characterize their deformation properties [26,27]. These rocks can lose strength within months to years of atmospheric exposure. In construction practice, soft rocks have shown rapid reactions when exposed to air and water, leading to accelerated degradation [28]. Depending on the lithology, they may exhibit various adverse properties with respect to underground construction activities, such as swelling, clogging, squeezing, and scouring [1,29]. These types of rocks are commonly fine-grained flysch, marls, claystones, siltstones, sandstones, or shales. The microstructure, porosity, and fracturing control the rate at which water infiltrates the rock [30].

The processes that eventually lead to slaking or disintegration are diverse. The mineralogical composition can cause the material to swell if water bonds to, or is incorporated into, clay minerals. Air pressure in the specimen increases as water infiltrates the pore space [31,32,33]. Stresses within the fabric can also enlarge the pores [34]. Thermal stresses can lead to tensile cracking during the drying process [35]. The pore interconnectivity and pore size significantly impact the reaction intensity when wetting the sample with water. With progressive lithification, the quality of the carbonate cement in fine-grained flysch rocks increases, thereby enhancing their slaking resistance [15].

Figure 2.

Weathering stages as a function of the proportion of mineral neoformation (Mineralogical Change Parameter) and amount of fracturing (Physical Change Parameter). ISRM weathering classes [36] in Roman numbers: I = fresh, II = slightly weathered, III = moderately weathered, IV = highly weathered, V = completely weathered, and RS = residual soil. Slaking of rocks is expressed within the Quantitative Weathering Index (Ia) (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ceryan et al. (2008) [23]. Copyright 2007, Springer Nature).

Sites situated in weak rock show enhanced weathering and debris mobilization from surrounding slopes. Ongoing climate change and the resulting increase in extreme weather events are placing a growing strain on infrastructure maintenance and inspection in Austria, occasionally necessitating the temporary closure of major highways [37]. Recent findings by Mishra et al. [38] indicate that at least 10% of landslides occurring in the Feldbach district (Styria) during a summer 2009 event were directly attributable to increased rainfall associated with anthropogenic climate change. Complementary simulations by Maraun et al. [39] further suggest that climate-induced alterations in precipitation regimes and land use may lead to an expansion of the affected area by up to 45%. Given their inherent sensitivity to intense rainfall, landslides and rockfall events in mechanically weak lithologies represent a significant hazard to public infrastructure.

The current research aims to combine standard testing routines established in current practice to draw conclusions about long-term slaking behavior. Information on disintegration patterns of weak rocks and local climatic and topographic conditions is used to formulate assessment schemes for maintaining road cuts, gabions, armor stones, and other retaining structures.

1.2. Current Practice of Rock Durability Testing

Testing soft or weak rocks typically involves three steps: identifying the rocks, testing their slaking resistance and durability, and determining their composition to assess swelling potential [20]. The identification as well as static testing identification of potentially weak rock is usually achieved by performing wetting tests according to ISO 14689 [7]. If the material shows little to no change after 24 h in water (grades 1 and 2 out of 5 are stable), two additional tests are performed since the ISO 14689 test does not adequately assess time-dependent long-term disintegration or degradation.

The first additional test is the modified wetting–drying test (WDmod), introduced by Nickmann [40] as an extension of the ISO 14689 test. It assesses slaking rates by adding two additional cycles of water immersion with oven drying at 60 °C between the respective cycles, and has recently been issued in the recommendation of the German Geotechnical Society [41]. The WDmod introduces six categories of durability (VK 0 to VK 5) that can be applied to soft sedimentary rocks and weathered rocks in general (Table 1). An optional element of the WDmod is the crystallization test, which involves repeatedly exposing the rock to a salt solution [1]. If the rock resists the salt attack, it is classified as unconditionally hard rock [14].

Table 1.

Categories of durability of the WDmod [14,40,41,42]. (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Nickmann et al. (2025) [41]. Copyright 2025, John Wiley and Sons).

The second additional test is the slake durability test, which adds a dynamic component by subjecting the sample to mechanical action within a rotating drum made of steel mesh, while it is submerged in water [6,43,44]. The test result is the slake durability index (Id), expressed as the percentage of fragments retained in the drum after two cycles [43]. The slake durability test simulates the time-dependent behavior of rocks exposed to atmospheric and meteoric conditions (i.e., weathering). Initially, the test was intended primarily for shales and argillaceous rocks [45], but it is now applied to weak rocks in general [43]. For example, Selen et al. [30] have successfully performed slake durability tests on weathered serpentinite rock.

The International Society for Rock Mechanics’ (ISRM) suggested method [6] states that the maximum grain size for the rock (not the lump size) to be tested in the slake durability test should not exceed 3 mm. Another issue with the Id method is that it determines the Id as the mass greater than 2 mm retained in the steel drum, regardless of the grain shape and distribution of the material [46,47]. Comparisons with field weathering profiles revealed that the Id delivers overly optimistic durability values. To address this, Ersöz and Topal 2004 [48] developed an approach that uses either a slot-type steel drum mesh or saturates the rock lumps prior to testing. Cano and Tomás 2016 [46] introduced the Potential Degradation Index (PDI), which is expressed as the natural logarithm of the number of slaking cycles required to degrade 50% of the initial sample. Visual assessment and photographic documentation are thus important for characterizing the type or potential mechanism of degradation [15,48]. The Jar–Slake test provides an on-site method for quick classifications of degradation types; however, multiple types may occur within one sample, which makes visual assessment difficult [3].

Another testing procedure for assessing the degradability of weak crystalline rocks is described in EN 17542-1 [49]. Sample preparation is similar to the slake durability test, involving the preparation of rock lumps between 40 mm and 80 mm and the determination of a sieve curve. After four wetting–drying cycles, a second sieve analysis is performed, and the degradability index is expressed as the ratio of the D10 values before and after the test.

Even though these tests are well-established, standardized, and widely accepted, they are still not sufficient for evaluating durability and weathering to reflect degradation rates under field conditions [50]. The WDmod by Nickmann [40] omits cohesive material (i.e., small grain sizes < 0.063 mm) after each wetting–drying cycle, which may be satisfactory for weathering decay assessment. However, fine-grained components can play an important role in evaluating the engineering relevance of the rock’s decay products. For this reason, adapted and extended versions of slaking tests were developed to address project-specific questions related to disintegrated material, as occurs during tunneling or mining. Rock degradation and decay in mechanized tunneling, for example, is simulated by a modified slake durability test [51]. In this test, the material is not dried before or between cycles, and soil mechanical index parameters (e.g., Atterberg limits and grain size distribution) are determined after the test is complete. Hollmann and Thewes [12] and Thewes and Hollmann [52] developed a universal diagram to help operating engineers of EPBs identify the effects of groundwater or conditioning/support fluids on the clogging behavior of excavated material. Keaton and Mishra [53] adapted the slake durability test to predict the scour potential of streams carving through soft rock. Various studies have also emphasized the importance of conducting more than two cycles when evaluating high-durability rocks (e.g., refs. [54,55,56]). The DGGT [44] recommends performing up to six cycles if the material is highly resistant, in order to evaluate long-term rock decay behavior.

The mineralogical composition of the weak/soft rocks is assessed in the third step. Identifying and quantifying clay minerals using X-ray powder diffraction is especially essential. On the one hand, the swelling potential is critical in construction practice, and on the other hand, the mineral type and amount strongly control the slaking behavior. Kaspar et al. [15] demonstrated that the formation of fragments in flysch rocks is largely controlled by sheet minerals, resulting in platy flakes. In contrast, carbonate-rich rocks result in more resistant, rounded fragments. Furthermore, mineral types are indicators of time-dependent durability. The boundary where weak rocks transform into permanently hard (non-slaking) rocks is not sharp but is closely related to the transformation of illite into more stable, water-insensitive sheet silicate minerals, such as muscovite and chlorite, at temperatures of ~300 °C and depths of >10 km [40]. By analyzing the cumulative amount of clay minerals passing through a steel drum mesh, Gökçoğlu et al. [57] demonstrated that long-term effects become apparent after three or more cycles of the slake durability test. Conversely, stable minerals originating from crystalline rocks can transform into clay minerals (e.g., feldspar to kaolinite or mica to illite). Guo et al. [58] observed that clay mineral content reduces the tensile strength of sandstones during repetitive wetting–drying cycles. Thus, identifying and quantifying the mineralogical composition of a rock, in combination with knowledge of its genetic origin and petrographic microstructural investigations, allows one to draw conclusions about the state of diagenesis, the degree of alteration/weathering, and the approximate range of geotechnical parameters [17,40].

The present study applies established slake durability testing methods to rocks of diverse genetic origins, aiming to elucidate differences in slaking resistance and long-term durability across various lithologies. The test samples were selected based on the traditional UCS definition (<25 MPa) and their sedimentary origin with minimal diagenetic lithification. The influence of rock fabric, mineral content, and other laboratory parameters was assessed in static and dynamic slaking laboratory tests. The proportion of dynamic to static slaking durability resistance was investigated, and the rock fabric and composition were characterized to identify possible causative factors. The main contribution of this evaluation is to verify the practical value of the test results for estimating slaking rates and sensitivity. The discussion further explores the broader implications of weak rock disintegration for infrastructure hazard management and geotechnical asset management.

2. Materials and Methods

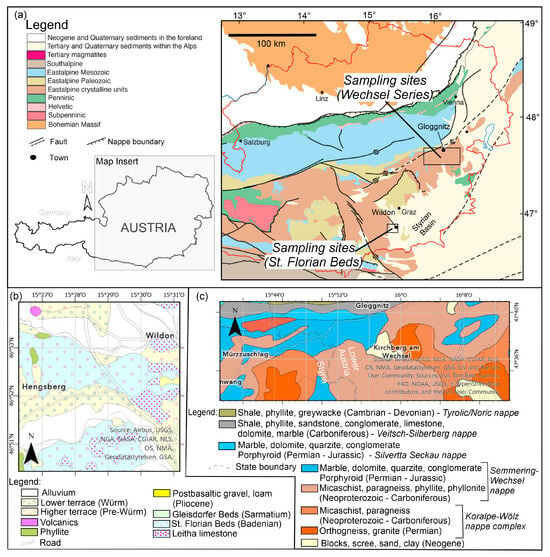

The tested rock samples encompass rocks from the Austrian Alps and adjacent basins. Twenty-two samples of Miocene sedimentary rocks (22 claystones and siltstones) were obtained from the St. Florian Beds in the Styrian Basin [59], and 49 samples of soft crystalline rocks and breccias (12 sericite phyllites, 7 carbonate and 5 sulfate breccias, 8 low-strength micaschists, 10 feldspar-richschists, 1 tectonized gneiss, and 6 cataclasites) were collected from the Wechsel region, a mountain pass between Graz and Vienna (Figure 3). The St. Florian beds were deposited during a marine transgression into the Styrian Basin around 15 million years ago. These sediments are locally intercalated with fluvial sands and contain fossils [60]. Rocks in the Wechsel region exhibit a complex tectonic evolution comprising amphibolite-facies Variscan basement rocks overlain by low-grade Permian-to-Upper Triassic rocks [61]. These rocks experienced intense imbrication, folding, and thrusting during the Eo-Alpine orogeny [62,63].

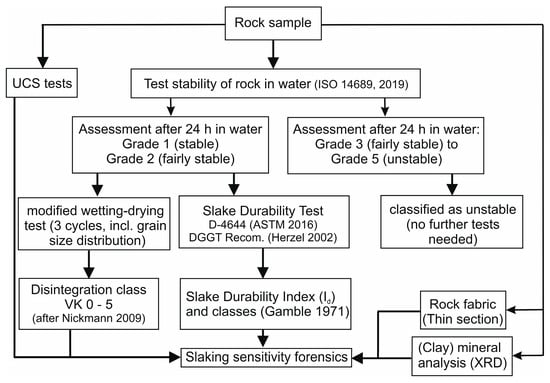

The testing routine setup is depicted in Figure 4. A total of 71 rock samples were retrieved from hand specimens and drill cores, covering a wide range of lithologies with respect to their diagenetic, tectonic, metamorphic, and hydrogeological attributes. From the Miocene sediments, hand specimens were collected from surface outcrops and the Hengsberg tunnel face, while for the Wechsel series rocks, drill cores extending to depths of up to 730 m were used to obtain samples.

First, wetting tests were conducted on all samples according to ISO 14689 [7], which involves storing the samples in deionized water at room temperature for 24 h. Rocks rated as Grade 1 or 2 were tested further under repeated static conditions (the modified wetting–drying test, WDmod) and under dynamic conditions in slake durability (SD) tests using a second set of samples.

The modified WD test [40] involves two additional wetting–drying cycles and sieving of the fragments [1]. Only fragments of >0.063 mm were used during additional cycles, and the proportions were taken into account in the subsequent grain size distribution curves. Fragment sieving after the modified WD test was performed according to ISO 17892-4 [64], utilizing sieves with aperture sizes of 63, 20, 6.3, 2, 0.6, 0.2, and 0.063 mm. Fine particle suspensions (<0.063 mm) were analyzed using a Micromeritics Sedigraph III particle size analyzer. The clay size fraction (<0.002 mm) for clay mineral analysis was extracted by sedimentation in cylinders following the hydrometer method [64].

The slake durability tests were performed according to the procedures described in the ASTM D 4644 [43] to determine the slake durability index after two cycles (Id2). In accordance with Recommendation No. 20 of the Commission on Rock Testing of the German Geotechnical Society, DGGT [44], resistant rocks were tested for up to six cycles (Id6) or until more than 70% of the material in the drum was lost. The material was dried at 110 °C in a thermostatically controlled oven (BINDER FD 53), and from each sample, ten rock lumps, having an initial weight of 40–60 g, were produced. The lumps were placed in a steel drum with a mesh size of 2 mm, and rotated at 20 rpm in deionized water at a temperature of 22 °C.

Thin sections were prepared by cutting and formatting the rock samples into blocks that measured approximately 2 × 2 × 5 cm using a diamond saw. The blocks were then polished to a thickness of about 30 µm for inspection under a transmitted light microscope (Leica DM LMP). The bulk mineralogical composition of the material was determined using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer (Co Kα radiation, 40 kV and 40 mA; scan range, 4–85° 2θ; step size, 0.02° 2θ; time/step, 20 s) and quantified with internal standards. The clay mineral suspension obtained in the Atterberg sedimentation was filtered and sucked onto porous ceramic plates to obtain textured samples. The analysis was performed in a Philips PW 1830 diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation, 40 kV and 30 mA; scan range: 2.5–15° 2θ), and expansion of the clay minerals was induced by cation exchange reactions (Dimethyl sulfoxide) and treatment with glycerol. Quantification of the clay mineral suspension was done following the semi-quantitative procedure according to the Austrian Standard ON B 4810 [65].

The uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) was determined on cylindrical specimens with a diameter-to-length ratio of 2:1 (typically, diameter = 50 ± 5 mm and length = 100 ± 10 mm) using an MTS Model 815. The tests were conducted with a minimum duration of five minutes, following recommendation No. 1 of the Commission on Rock Testing of the German Geotechnical Society [66] and the Austrian standard ON B 3124-9 [67], and were load- and/or strain-controlled.

Figure 3.

Location maps of the sample sites: (a) Simplified geologic map of Austria with locations of the sample sites (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Spötl et al. (2021) [68]. Copyright CC-BY, the authors, published by Elsevier B.V (2021); (b) geological map of the area between Wildon and Hengsberg (Reprinted/adapted with permission from GBA (2022) [69]. Copyright CC-BY-4.0 (2022), Geologische Bundesanstalt (GBA); (c) geological map of the Wechsel region around Gloggnitz (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Geosphere Austria (2023) [70]. Copyright CC-BY-4.0 (2023), GeoSphere Austria).

Figure 4.

Flowchart illustrating the three categories of tests related to the strength, durability, and composition of weak and soft rock [7,40,43,44,45].

3. Results

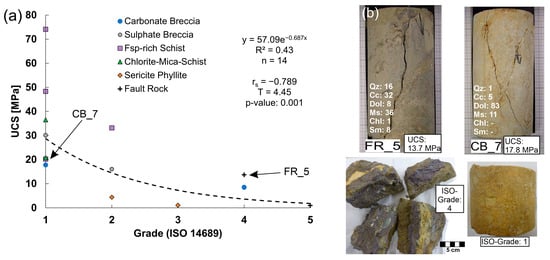

Representative samples were selected and retrieved from the Wechsel area to be tested for their UCS to verify that they were soft rocks in terms of their compressive strength (Figure 5a). All rocks except for one showed UCS values below 50 MPa, resulting in a moderate correlation between slaking grade according to ISO 14689 and the UCS. The classification of the remaining rocks from the St. Florian Beds was based on field assessments following the ISO 14689 guidelines. Clay and siltstones were assigned to categories R0 to R2 according to ISRM 1978 [36], qualifying them as weak rock [40]. All cataclastic and disturbed rocks (fault rocks), as well as all carbonate breccias (except for one sample), were assigned to ISO 14689 grades 4 and 5 (Figure 5b)—grade 3 comprised sericite phyllites, fsp-rich schists, and clay/siltstones.

Figure 5.

UCS and VK class assignment of the tested rocks: (a) Distribution of the UCS values in the different slaking grade classes for the rocks of the Wechsel series; (b) photodocumentation of a grade 4 fault rock (left) and a grade 1 carbonate breccia (right) [7].

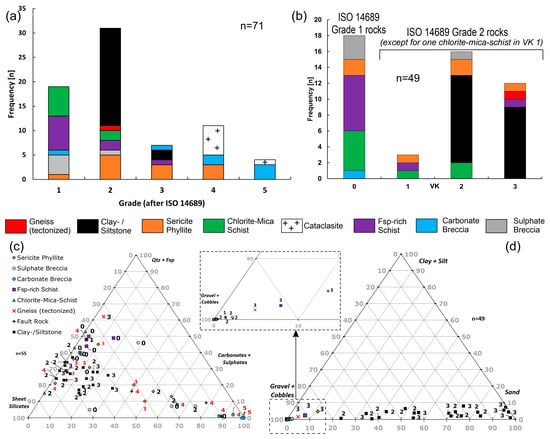

A total of 49 out of 71 samples were rated Grade 1 or 2 (Figure 6a). These samples exhibited minimal slaking, i.e., few cracks or surficial crumbling, and were thus tested further in modified WD and slake durability tests. After three consecutive cycles of static wetting–drying tests, all Grade 1 samples fell into category VK 0, showing no further slaking (Figure 6b). A total of 30 out of 31 samples initially described as Grade 2 were classified as VK 2 after three wetting and drying cycles. Some were classified as VK 3, and only two samples were classified as VK 1.

Figure 6.

Slaking grades, mineralogical composition, and grain size distributions of the investigated rocks: (a) Slaking grades of the investigated rock after ISO 14689; (b) VK classes of the durable samples with an initial Grade 1 and Grade 2 after ISO 14689 after a total of three slaking cycles; (c) ternary diagram showing the mineralogical composition of the investigated rock samples with the assigned ISO grades (red numbers) and VK classes (black numbers); (d) ternary diagram of the grain size distribution after the WDmod [7].

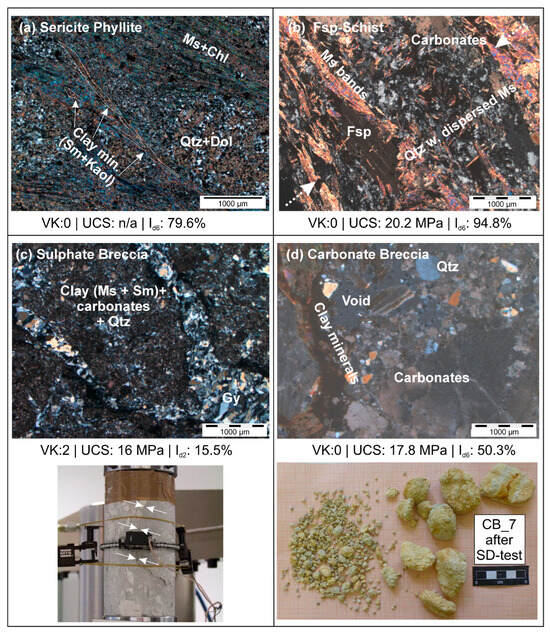

The only rock type present in all classes is sericite phyllite. Claystones and siltstones are only found in classes VK 2 and VK 3. Figure 6c shows the mineralogical composition of the investigated rock types. The ternary diagram illustrates the relationship between the primary rock fabric constituents, which are classified as quartz and feldspars, salts (carbonates and sulfates), and sheet silicates. Miocene sediments exhibit up to 30% carbonates (no sulfate phases are present in these rocks) and 50–75% sheet silicates. The quartz and feldspar content varies from 20 to 40%. Crystalline rocks of the Wechsel series have 30 to 85% sheet silicate content, 10 to 60% quartz and feldspar, and usually less than 10% carbonate. Only sericite phyllites with gypsum and calcite veins exhibit higher values. Brecciated and fault rocks have variable compositions and constitute the rock types with the largest number of samples that degraded during one cycle of the ISO 14689 WD test. Because the assigned grades and classes of durability are scattered throughout the diagram, it is not possible to make a statement about the potential slaking behavior based solely on mineralogical composition. This suggests that fabric elements (e.g., microfissures, bedding or foliation planes, and porosity) and grain boundary strength have a strong influence. The thin-section photographs show examples of fabric- and mineralogy-controlled properties of selected rocks (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Fabric details and observed fracture and slaking patterns of selected rocks: (a) Thin-section photograph of a sericite phyllite. The sample did not show changes during the WDmod (VK 0 class), but disintegrated in the slake durability test into smaller fragments, preferably along the narrowly spaced foliation planes. Note that the rock also comprised bands of swelling clay, which can favor disintegration; (b) feldspar schist with dispersed mica embedded in quartz and feldspars. Arrows indicate a principal stress direction normal to foliation during the UCS test. No reaction was observed in the WDmod cycles, but the UCS was low, probably due to fracture propagation along the grain boundaries along the finely dispersed muscovite grains; (c) thin-section photograph (top) of a sulfate breccia with gypsum and fine-grained groundmass of clay/mica, quartz, and carbonates. High material loss already after Id2. Fracture propagation through the UCS specimen (bottom) occurred preferentially along clast boundaries through the matrix (white arrows); (d) carbonate breccia thin-section photograph (top) with voids and point-to-point grain contacts not reactive/slaking in the static WD test, but extensive degradation was seen in the SD test (bottom). All thin-section photographs were taken with crossed nicols. Abbreviations: Chl = chlorite, Fsp = feldspar, Kaol = kaolinite, Ms = muscovite, Qtz = quartz, and Sm = smectite.

Figure 6d illustrates how the rock’s fabric can resist slaking and disintegration during repetitive WD cycles in the WDmod test through grain size distribution. Initially, specimens were retrieved from 10 cm drill cores or large hand specimens, ensuring that all rocks were >63 mm in grain size. Miocene sediments degrade into fine components, ranging from 20 to 98% sand. As disintegration increased, the number of VK3 samples in the sand-rich region increased. However, there are VK 2 samples in the sand corner because the diagram reflects the grain size distribution after the third WDmod cycle. For example, the VK 2 rocks remained largely unchanged after the first cycle and then disintegrated in consecutive cycles. Conversely, the VK3 rocks disintegrated strongly at first and then changed less until the third cycle. Notably, the proportion of silt and clay remained low (less than 10%) throughout the investigated samples. Except for three crystalline VK 3 class samples, the grain-bound rocks clustered in the gravel–cobble corner region. However, their rate of absolute disintegration into particles smaller than 2 mm was much lower compared to the sedimentary rocks. The VK 0 and 1 samples were densely clustered in one corner of the diagram, while the VK 2 rocks were slightly off (see the small insert in Figure 6d). According to Nickmann [40], the location of the samples in the ternary diagram indirectly indicates the degree of weathering. Fresh, unweathered rocks disintegrated into coarser components and plotted closer to the gravel corner. For example, the crystalline rocks split along preferred zones, such as foliation planes, where weathering zones propagated into the rock. The remaining pieces were thus intact rock fragments that were less susceptible to slaking and disintegration in repetitive weathering and disintegration (WD) cycles. With progressive weathering, the decay products usually become smaller [71], and generally, there is an increase in VK 3 towards the sand corner. However, rocks assigned to higher VK classes also exhibited higher proportions of coarse fragments. In this context, grain size distribution is a useful tool since VK provides limited information on how rock fragments disintegrate, but not how they are distributed.

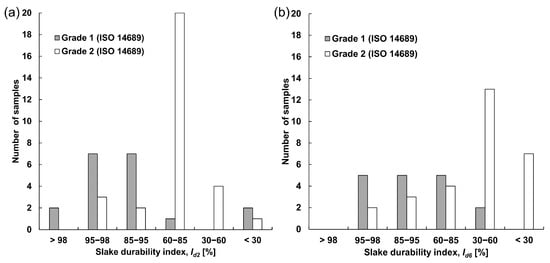

Most samples that showed almost no slaking after three wetting–drying cycles (Grade 1/VK 0) had slake durability indices of 85% or higher (Figure 8a). Rocks that degraded completely (i.e., Id < 30%) were gypsum- and anhydrite-rich sulfate breccias.

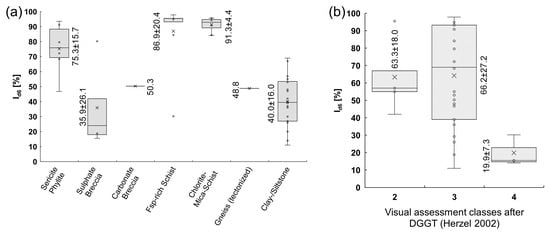

Figure 8.

Slake durability indices after two and six cycles, respectively. Id values are grouped according to the slake durability classes of Gamble 1971 [45]. (a) Slake durability indices after two cycles; (b) slake durability indices after four additional cycles (i.e., Id6) performed on the same set of rocks. Note that the rocks that were already in the lowest class were removed from the plot since they were not tested further if Id2 < 30 [7].

Grade 2 samples exhibited greater variability in Id2 values; most fell within the 60–85% range and were classified as moderately resistant to slaking. After six cycles, none of the samples remained in the highest durability class, and most of the Grade 2 rocks were found in the two lowest classes (Figure 8b). Conversely, none of the Grade 1 rocks degraded enough to fall into the lowest class.

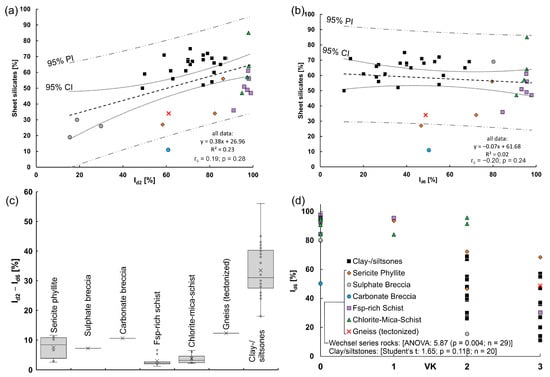

Slake durability tests were performed up to six cycles to identify long-term degradability factors. Kaspar et al. 2024 [15] demonstrated that sheet silicates, in particular, negatively impact the slaking resistance of early diagenetic rocks, such as flysch. This was also observed in the fine-grained sedimentary rocks investigated in this study. After two testing cycles, these rocks still exhibited Id values of >50% (Figure 9a). Conversely, after four additional cycles, the data points for the claystones and siltstones migrated toward lower Id values, while the weathered, sheared, and sheet silicate-rich crystalline rocks showed very little additional degradation (Figure 9b). An increase of up to 40% was observed from Id2 to Id6 for the clay and siltstones, while the other rocks were less than 15% (Figure 9c). The crystalline rocks exhibited stronger degradation if they were assigned to the VK 2 and VK 3 classes. For VK 0 and VK 1, Id6 does not fall below 80%. Durability in the VK 2 and VK 3 classes dropped to 20–30% (Figure 9d).

Figure 9.

Slaking behavior in the context of the mineralogical composition and the number of testing cycles performed on the analyzed rocks: (a) Id2 vs. sheet silicate content. After only two cycles, the samples exhibited an apparent positive effect and a weak correlation between the sheet silicate content and slaking resistance; PI = prediction interval, CI = confidence interval. (b) Id6 vs. sheet silicate content. There was no correlation, and the Id decreased significantly for sedimentary, sheet silicate-rich rocks (i.e., clay- and siltstones); (c) relative decrease of Id between the 2nd and 6th cycle for the different rock types; (d) range of Id6 within the VK classes.

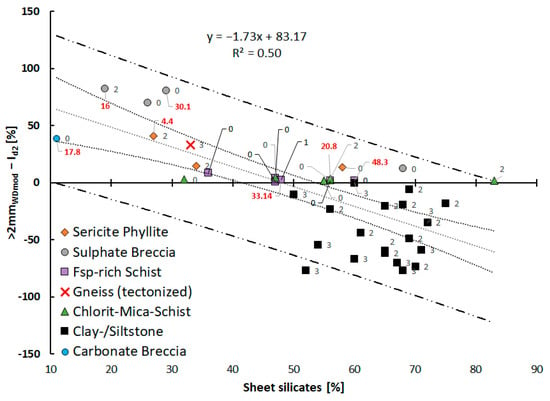

To quantify the difference between the static and dynamic slaking effects, we correlated and analyzed the sieve curves of the modified wetting–drying test and the slake durability index (Id2). In both cases, the samples had undergone three drying cycles since the material used for slake durability tests is dried before testing. The material for the wetting–drying (WD) test was tested with its natural water content and dried after each cycle. The slake durability index essentially represents the proportion of the initial sample that is greater than 2 mm due to the mesh size of the steel drum. This value is linked to the proportion of particles greater than 2 mm after the modified wetting–drying test by subtracting Id2 from the proportion of particles greater than 2 mm in the WDmod test. The difference is the dynamic part of slaking resistance (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Correlation between the difference of Id and >2 mm WDmod and the content of sheet silicates. Rocks exhibiting negative values were highly sensitive to static slaking. The positive values are indicators for rocks susceptible to dynamic slaking. Black datapoint labels are the assigned VK classes, red italics labels are UCS values in MPa.

One might intuitively expect dynamic action to result in greater rock degradation than static conditions. However, the values range from +80% to −80% for the dataset under investigation (Figure 10). Very weak rocks, such as clay and siltstones, exhibited negative values, indicating that they are more degraded after three repetitive wetting–drying cycles at 24 h each than after two dynamic cycles of the slake durability test. Soft, sheet silicate-rich crystalline rocks tended to exhibit the same slaking behavior in the two types of tests, suggesting that there is little to no difference between static and dynamic slaking behavior. The more positive the values, the higher the dynamic slaking sensitivity compared to static conditions. For these types of rocks, a higher sheet silicate content is associated with less dynamic action required to degrade the rock during the slake durability test. Sulfate breccias, for example, exhibit very high values and are already degraded after two slake durability cycles despite showing almost no slaking in the wetting–drying cycles. None of the VK 0 and VK 1 rocks plotted in the negative field around the zero axis, which confirms their high slaking resistance. VK 2 data points are present in both regions, and except for one sample, VK 3 data points are present only in the negative region. Crystalline rocks that have experienced grain size and cohesion reduction due to shearing are less susceptible to static slaking than inherently fine-grained rocks. Unlike clay-siltstones, the tectonized gneiss sample (Figure 11) did not crumble under static conditions nor did it develop a negative ratio of 2 mm WDmod to Id2. Mineralogical analysis by XRD revealed no neoformation of clay minerals that could lead to more severe static slaking, with muscovite being the only sheet silicate species present in this rock.

Figure 11.

Procedure for linking the results of the modified WD test to the Id2 for evaluating the dynamic slaking proportion. A rock exhibiting an Id2 = 61.1% has a dynamic slaking proportion of 33.2% if the proportion >2 mm WDmod = 94.3%.

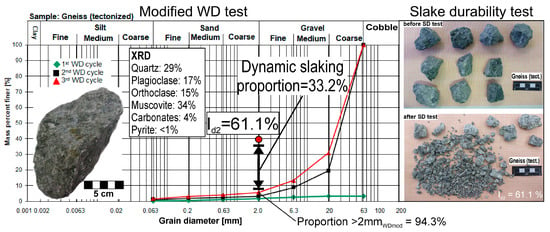

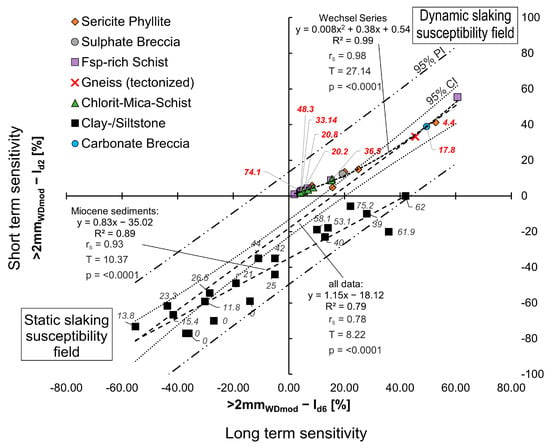

To assess long-term slaking sensitivity, the Id2 and Id6 are linked to the >2 mm WDmod. Figure 12 shows a diagram that allows one to qualitatively determine the slaking sensitivity of different rock types. The more negative the value, the higher the static slaking sensitivity of a rock when it comes in contact with water. The plot also shows that fine-grained, sedimentary, sheet silicate-rich rocks lie at or below the zero percent line. Static slaking does not seem to affect fine-grained, soft, crystalline rocks (e.g., phyllites and micaschists), as material loss mostly occurs through the removal of surficial material along structurally defined features, such as foliation planes, during mechanical action, as occurs in the rotating drums during the slake durability test. These rocks lose material in a layer-by-layer pattern rather than breaking apart from the inside, resulting in rounded components where the ten initial fragments remain largely intact. However, some flakes were removed from the samples, classifying them as Type II (ASTM D 4644) and Class 3 (DGGT Rec. No.20) (Table 2; Figure 13a). If the fabric’s integrity is already significantly degraded, fragmentation similar to that observed in clastic sedimentary rocks may occur (Figure 13b).

Figure 12.

Plot of the dynamic components after two and six slaking cycles to determine the slaking sensitivity of rocks. Crystalline and diagenetic cemented sediments are plotted in the upper right quadrant, where the dynamic slaking component increased with more positive values. Rocks near the origin are resistant to slaking in the short and long term (red italicized numbers indicate the UCS). Miocene sediments (clay- and siltstones) are plotted in the lower left and lower right quadrants. The more negative the values, the more the rock is prone to slaking under static conditions and tends to crumble into smaller fragments (Datapoint labels show the proportion > 2 mm WDmod). Note that the slaking assessment is of a qualitative nature, as well as a function of the laboratory tests conducted in the course of this investigation.

Table 2.

ASTM [43] and DGGT [44] visual assessment classes after the slake durability test.

Figure 13.

Examples of comparisons of slaking patterns of soft/weak rocks from crystalline and sedimentary origins. (a) Low-strength, high-durability Fsp-rich schist; (b) Fsp-rich schist with loss of fabric cohesion retrieved near a fault zone; (c) clay-/siltstone exhibiting negative dynamic slaking patterns in the short term (Id2) and positive in the long term (Id6).

Crystalline rocks with a UCS > 20 MPa were plotted near the origin, and dynamic slaking sensitivity increased along the fitted line due to increased fabric degradation, resulting from processes such as tectonic shearing or weathering. Miocene sedimentary rocks were found in the negative region, indicating high static slaking potential. The more negative the values, the higher the slaking sensitivity and fragmentation (i.e., low proportions of <2 mm WDmod).

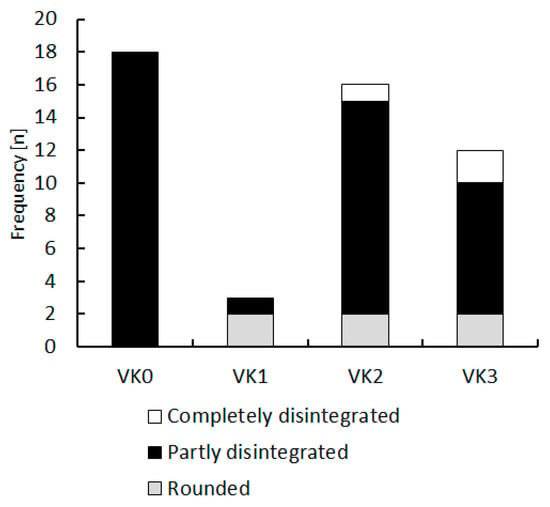

Table 2 shows the ASTM D 4644 classifications [43] and the DGGT recommendations [44] for comparison. Figure 14a illustrates the range of the visual assessment in relation to the slake durability index, emphasizing the issue of the quantity of rock pieces greater than 2 mm that remained in the drum after six cycles, relative to the grain size characteristics of the retained fragments. In class 3, for example, the Id ranges from 20% to nearly 100% (Figure 14b), indicating that, despite crumbling into smaller pieces, the rocks still exhibited very high slaking resistance in the slake durability test. At the same time, class 3 rocks after DGGT are present in all VK classes (Figure 15). When transferred to real site conditions, such as a cut slope, the Id would yield an overly optimistic assessment.

Figure 14.

Ranges of Id6: (a) Range of the Id6 for each rock type; (b) range of the Id6 within the visual assessment classes. None of the samples fell into class 1 [44].

Figure 15.

Distribution of the DGGT degradability classes within the VK classes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mineralogical Controls of Slaking Processes

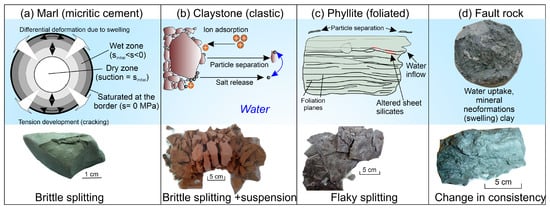

Sheet silicates are considered a key element in understanding the slaking and disintegration behavior of soft and weak rocks, negatively affecting long-term slaking resistance. In sedimentary clastic sediments, such as claystones and siltstones, but also marls, the fabric consisting of fine pores and small grain sizes favors the buildup of a suction gradient, which is accompanied by swelling of clay minerals during wetting and shrinkage during drying [72]. Fine-grained, weakly cemented clastic rocks may experience particle separation and salt release [24] (Figure 16). Lempp [73] also recognized that weak sedimentary rocks do not actually take up water when submerged; rather, compressed air causes tension in the pore space due to suction, which enhances degradation by damaging grain bonds. More pores and fracture spaces become available in subsequent wetting–drying cycles, where degradation continues. Rocks rich in clay minerals in an early diagenetic stage may exhibit plastic behavior upon wetting rather than breaking into small pieces.

Figure 16.

Slaking patterns observed in different soft and weak rocks: (a) Dense and compact marl (sketch reprinted/adapted with permission from Alonso et al. (2010) [72]. Copyright 2010, Geological Society of London); (b) fine-grained clastic sediment (sketch reprinted/adapted with permission from Liu et al. (2023) [24]. Copyright CC-BY (2023), the authors); (c) phyllite with closely spaced foliation acting as entry points and surfaces for water and mineral alterations, respectively; (d) fault rock exhibiting a plastic behavior after water uptake.

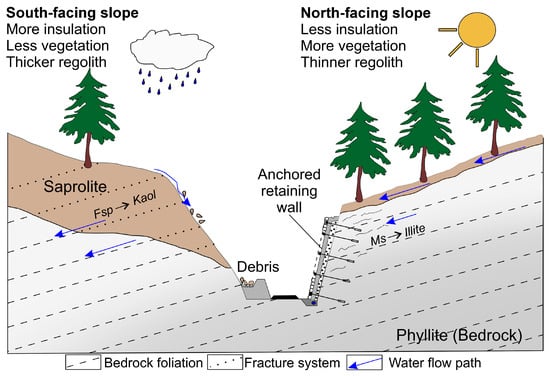

In crystalline rocks, sheet silicates primarily consist of mica and chlorite minerals, which have a low negative surface charge deficit. This makes them less sensitive to ion exchange and dissolution. The clay minerals found in these rocks result from alteration (e.g., hydrolysis) and can contribute to rock disintegration. These rocks tend to split along foliation planes defined by sheet silicates, which are the areas where weathering can most easily attack the rock. In grain-bound sedimentary rocks, such as carbonates, degradation is caused by joints and fractures. The properties of the remaining pieces resemble those of the unaltered rock, as indicated by positive dynamic slaking proportions. Additional degradation occurs only if the rock is subjected to mechanical action, such as a slake durability test. Such rocks then loosen along preexisting structural features, such as foliation planes, or due to cement dissolution from chemical weathering. These rocks lose material in a layer-by-layer pattern rather than breaking apart from the inside. Compared to static conditions, the carbonate and sulfate breccias showed the highest dynamic slaking potentials.

Discrimination, based on mineralogical properties and fabric characteristics, is assessed by comparing the fragmentation characteristics of static and dynamic slaking tests. As strength decreases, crystalline and grain-bound rocks become more susceptible to slaking and disintegration. The more sensitive sedimentary clastic sediments are, the smaller the remaining pieces become.

Combined analysis of static and dynamic slaking properties is an important complement to assessing rock slope behavior in terms of long-term stability and its response to extreme weather events, such as cloudbursts, flash floods, and gully erosion. Franklin and Chandra [74] demonstrated that rocks with low slaking durability are susceptible to landslides. The discrepancy between the long-term static and dynamic slaking behavior of clay and siltstones could be reflected in the testing conditions. In wetting–drying tests, samples experience suction stresses for 24 h, whereas in the water tank of the slake durability apparatus, they experience them for only 10 min. If the strength of the sample does not drop significantly within this timeframe, then it can survive the mechanical action imposed by the drum with comparatively little material loss. Depending on the rock fabric, certain lithologies may not fully saturate during the routine slake durability test, in which the rock is immersed in water for only 10 min. Long-term experiments by Liu et al. [24] have demonstrated that it takes rock fabric several months to be affected by water saturation. Another possible factor could be related to scale effects. For the wetting–drying test, the samples weigh up to 2 kg and are several decimeters long. The fragments used in the slake durability test were usually no larger than 5 cm in diameter and weighed 40–60 g, which corresponds to the (semi)-intact fragment size produced during the WD test. Rock mass features (block size) and water conditions are two critical aspects for assessing the potential for long-term adverse behavior in soft rock, such as swelling, slipping, clogging, and raveling [1]. In tunneling through soft ground, for example, the rock is also exposed to air and/or in contact with temporary support fluids, enhancing the degradation. Hollmann and Thewes [12] used the slake durability index as an indicator for the intensity of liberation of fine-grained cohesive material. Atterberg limits of the decay products of the slake durability test, water content, and associated plasticity and consistency indices are determined, which provides an estimation of stickiness and clogging potential. The mineralogical composition and diagenetic lithification are key elements controlling the stickiness of the excavated rock on the tool or TBM cutter disc.

The current visual assessment of the rock after the slake durability test revealed two issues with the classification scheme: First, the material > 2 mm in the drum was not further considered in terms of grain size distribution. Second, the assessor’s judgment was subjective in determining what is considered partly or completely disintegrated. Additionally, terms such as “large” and “small” are subjective. Ersöz and Topal [48] presented a classification scheme for a broader range of rocks that included additional laboratory parameters, such as porosity, Schmidt hammer hardness, and point load index results. Moreover, they introduced a slot-type steel drum mesh. The PDI adds valuable information to the tests as well. It should be noted that these testing routines are very time-consuming and laborious, so their applicability to wider practical use is questionable.

4.2. Environmental Impact on Slaking Processes

Weathering is a long-term process that occurs in different climates with different mechanisms (physical or chemical) and severity. Further investigation is needed to evaluate the transferability of laboratory tests to rock types in various climatic settings. Some studies have shown that freeze–thaw aging decreases slaking resistance much more than wetting–drying does [55,75]. Additionally, the UCS values decrease when rock undergoes multiple freeze–thaw cycles [76]. It is also important to consider drying the samples at lower temperatures that more realistically reflect natural weather conditions (i.e., max. 60 °C). Nickmann et al. [14] emphasized that drying cycles are the most critical part of the wetting–drying test. He et al. [77] also demonstrated the strong effects that immersion time and wetting–drying cycles have on the disintegration rate of soft, weathered granites. Gökçoğlu et al. [57] found that multiple wetting and drying cycles affect slaking resistance by weakening mineral grain bonds.

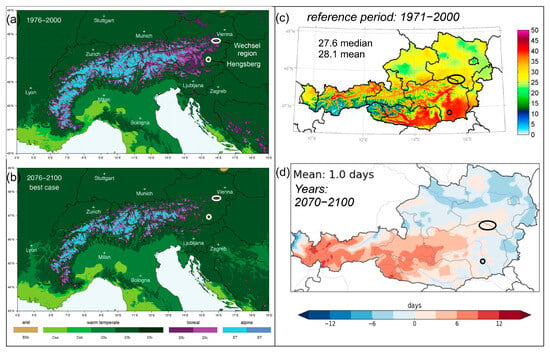

The weathering characteristics and degradation of rocks, which depend on the climate setting, can be used to estimate potential future hotspots of rock degradation. For example, these hotspots could appear along unprotected road cuts. In the case of Austria, optimistic climatic models (i.e., Representative Concentration Pathway RCP 4.5) indicate a shift toward increased freeze–thaw cycle frequency in alpine regions, especially above 1000 m [78]. There is no strict meteorological definition of a freeze–thaw cycle, but it typically involves temperatures staying above zero for two to six hours during the day and falling below zero at night. An increase in freeze–thaw cycles occurs at the expense of a decrease in ice days, i.e., when the temperature always lies below 0 °C. Regions currently in the Dfc and Dfb climate types, such as the Wechsel–Semmering region, will experience an increase in freeze–thaw cycles of 3–9 days in January and February, which are the coldest months of the year in Austria. Outer alpine regions like the St. Florian region and intra-alpine valleys will experience reductions in freeze–thaw cycles by 1–6 days. At the same time, cumulative precipitation and the intensity of extreme daily precipitation rates are expected to increase in all seasons. Strong precipitation events are especially likely during the winter season [79]. Figure 17 illustrates Austria’s current and anticipated future climatic zones [80] and the predicted changes in freeze–thaw cycles until the end of the century [79].

Figure 17.

Climate scenarios for Austria: (a) Current Köppen–Geiger climate classification based on observed HISTALP data (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Rubel et al. (2017) [80]. Copyright 2016, the authors); (b) shift of climate zones anticipating a best-case scenario of RCP 2.6. (Climate codes: C = warm temperature, D = snow, E = polar, T = tundra, f = fully humid, a = hot summer, b = warm summer, and c = cool summer); (c) distribution of freeze–thaw days in Austria; (d) long-term change in freeze–thaw days (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Chimani et al. (2016) [78]. Copyright CC-BY-4.0 (2016), GeoSphere Austria).

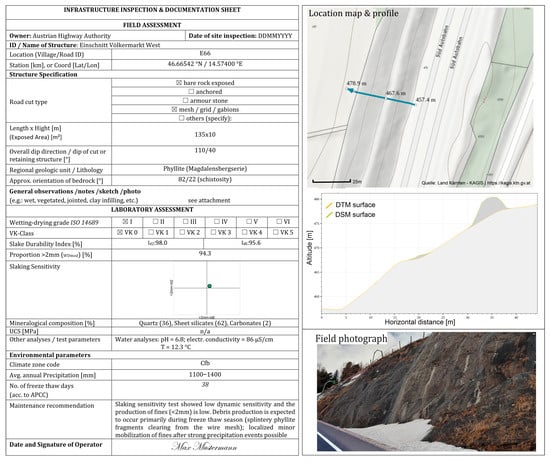

The road infrastructure asset maintenance and inspection routines should be adapted and individualized based on the climatic conditions, local topographic setting, and geologic setting. Figure 18 shows a suggested structure for a standardized inspection protocol with the relevant field- and laboratory-based assessment methods. The rock sample exhibits low slaking under dynamic and static conditions, with low liberation of fines. It is located in an area that experiences 25 freeze–thaw cycles, and it is exposed along a road cut with mesh protection. Freeze–thaw cycles have a more pronounced impact on rock weathering than wetting–drying alone, leading to an accelerated rate of degradation that necessitates enhanced surface protection. Systematically identifying vulnerable hotspots enables the targeted implementation of additional protective measures—such as soil nails, surface coverings, or grading—to reduce the risk of catastrophic failure during high-intensity rainfall events [81,82].

Figure 18.

Inspection and documentation sheet for site and laboratory characterizations in infrastructure maintenance routines.

One challenge is determining at which point highly weathered parent rock and redeposited, early diagenetic, weak rock begin to exhibit similar geomechanical properties, and whether they can be tested in a lab using the same methods. The saprolite in Figure 19, for example, still contains some original fabric elements; however, the material is completely disintegrated [83,84]. Depending on the terrain and local conditions, the degree of degradation differs for the same lithology. It may be necessary to perform climate-region- and site-specific testing, including freeze–thaw tests in alpine settings, salt environment tests in marine settings, and long-term wetting tests in fluvial, lacustrine, and coastal regions, to capture the entire spectrum of slaking behavior. Knowledge of the geologic origin of the rock and diagenetic evolution can provide insight into which active minerals to expect and which potential alteration products could develop at a specific site.

Figure 19.

Climate, exposure, and rock structure controlled the degradation of a soft rock slope, such as phyllite, and associated practical considerations for infrastructure measures. Neoformation of clay minerals (Kaolinite and Illite) at the expense of feldspars and muscovite. Enhanced debris production and progressive weathering front in the surrounding bedrock of a retaining wall, leading to a reduced cohesion between ground and structure (modified and compiled in line with [83,84]). (Reprinted/adapted with permission from Leone et al. (2020) [83]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons).

5. Conclusions

Grain-bound rocks lose their cohesion in situ due to weathering that activates mechanical zones of weakness, such as foliation planes. Meanwhile, weak sedimentary rocks are in the stage of developing a cohesive framework through diagenetic processes. The processes that form this framework are manifold and range from compaction to recrystallization to cementation. These processes increase cohesion and grain-bound strength and are collectively termed lithification. Applying established slaking tests to different rock types can assess the nature and intensity of rock disintegration by performing grain size distribution analyses and linking them to slaking tests. Combining routine slaking tests with grain size distributions of decay products evaluates the sensitivity and degree of fragmentation of different rock types. The present approach uses the proportion of decay products to determine if certain rocks are susceptible to enhanced slaking. Considering the climatic conditions of the sampling sites allows the tests to be individualized or adjusted to the actual on-site conditions. However, it should be noted that the slaking sensitivity assessment presented here is qualitative and based on widely used standardized laboratory tests (i.e., slake durability, wetting–drying tests, and grain size analyses). However, it can serve as a quick, rule-of-thumb assessment based on the results of these tests. The absolute slaking intensity and weathering rates observed in the field depend on various environmental factors, such as the exposure time of the rock and the climatic setting.

The Köppen–Geiger atlas shows that the study areas currently lie in regions Cfb and Dfb, but they may change to Cfb by 2100. Even in the most optimistic and now unattainable best-case scenarios, the effects of climate change are evident and point to a significant shift in climate zones in Austria by 2100. This shift in climatic zones is associated with changes in weathering regimes, such as enhanced freeze–thaw action in alpine regions and increased winter precipitation in outer alpine areas.

Therefore, the nature, proportion, and intensity of slaked rock can inform maintenance interval planning for road infrastructure. For instance, a phyllite roadcut may produce splintery particles that can be cleared in the spring after the freeze–thaw season ends. In lower regions where the weakly cemented St. Florian beds are located, climate models indicate fewer freeze–thaw cycles but wetter conditions with more intense precipitation. These sites would require more attention to clearing in the summer, when increased sediment mobilization is expected. A holistic view of the laboratory values, the location, exposure, and orientation of the exposed rocks (Figure 18) could be a valuable tool to identify which sites have to be cleared. However, it must be emphasized that a testing and calibration phase involving detailed documentation of the frequency and amount of material actually cleared by the road authorities is required to efficiently use the system. This information can then be used to estimate the amount of degraded rock per m2 of exposed rock per year. Scaling the decay behavior observed in the laboratory to actual field conditions poses the greatest challenge in this context, as it requires feedback from the field sites.

Clastic sedimentary rocks exhibited high static slaking sensitivity, while soft crystalline rocks showed elevated dynamic susceptibility if they were weak due to tectonic fabric disturbances or mechanically activated weakness zones (e.g., weathered foliation planes). Mineral analyses and thin sections can aid in identifying secondary mineral neoformations. In addition to quantitative assessment, visually documenting the fragments is important because the fabric controls the fragments’ grain shape. Rocks dominated by sheet silicates, such as phyllites and micaschists, tend to form splintery, flaky pieces. Carbonates can undergo dissolution (karstification), and fine-grained clastic sediments can undergo suction gradient formation and clay suspension formation due to surface particle removal or ion exchange.

The fabric and mineralogic composition-controlled disintegration is also reflected in their weathering pattern on a field scale, depending on the climatic conditions. Earthworks and structures in these settings face challenges in light of climate change, as extreme weather events, freeze–thaw cycles, and enhanced weathering require adapted maintenance strategies. This may involve more frequent debris clearing, shorter drainage pipe cleaning intervals due to scaling-related clogging caused by increased water inflow through the altered rock [85], or inspection of structures situated in lithology susceptible to slaking and degradation. To assess all alteration and degradation processes occurring in the rock mass, it may be helpful to include chemical rock parameters in the future, too [86]. Further studies are required to validate the proposed scheme on a larger scale, beyond laboratory index values, in order to make reliable suggestions and recommendations for the maintenance and operation of infrastructure situated in rock formations sensitive to slaking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and C.L.; methodology, M.K.; software, M.K.; validation, C.L., G.P. and V.R.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., C.L., G.P. and V.R.; resources, C.L.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, V.R.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, V.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly funded by the Climate and Energy Fund and was carried out under the program The Austrian Climate Research Programme, ACRP; No. KR21KB0K00001 (Grant ID FO999901436).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Supported by TU Graz Open Access Publishing Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hashemnejad, A.; Aghda, S.M.; Talkhablou, M. Introducing a new classification of soft rocks based on the main geological and engineering aspects. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 4235–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selen, L.; Panthi, K.K.; Mørk, M.B.; Sørensen, B.E. Compositional features and swelling potential of two weak rock types Affecting Their Slake Durability. Geotechnics 2021, 1, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, P. Improving the jar slake, slake index and slake durability tests for shales. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 1998, 4, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobereiner, L.; De Freitas, M.H. Geotechnical properties of weak sandstones. Géotechnique 1986, 36, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, M.A. Critical issues in soft rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 6, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.A.; Vogler, U.W.; Szlavin, J.; Edmond, J.M. Suggested methods for determining water content, porosity, density, absorption and related properties and swelling and slake-durability index properties. Int. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1979, 16, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14689; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Identification, Description and Classification of Rock. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2017.

- Verhoef, P.N.W. Wear of Rock Cutting Tools—Implications for the Site Investigation of Rock Dredging Projects; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; ISBN 90 5410 434 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, M.; Latal, C.; Blümel, M.; Pittino, G. Is soft rock also non-abrasive rock? An evaluation from lab testing campaigns. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1124, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuro, K. Drillability prediction: Geological influences in hard rock drill and blast tunnelling. Geol. Rundsch. 1997, 86, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, M.; Latal, C.; Pittino, G.; Blümel, M. Hardness, strength and abrasivity of rocks: Correlations and predictions. Geomech. Tunn. 2023, 16, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, F.S.; Thewes, M. Assessment method for clay clogging and disintegration of fines in mechanised tunnelling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 37, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoun, S.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Shahriar, K.; Rostami, J.; Azali, S.T. Evaluation of tool wear in EPB tunneling of Tehran Metro, Line 7 Expansion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 61, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickmann, M.; Spaun, G.; Thuro, K. Engineering geological classification of weak rocks. In Proceedings of the 10th Congress of the International Association for Engineering Geology and the Environment (IAEG), London, UK, 6–10 September 2006; Culshaw, M., Reeves, H.J., Jefferson, I., Spink, T.W., Eds.; Geological Society: Nottingham, UK, 2006. Paper No. 492. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, M.; Latal, C.; Frühwirt, T.; Blümel, M. Assessment of factors controlling the slaking behaviour of rocks from the Rhenodanubian Flysch Zone, Austria, using mineralogical-geomechanical laboratory tests. In New Challenges in Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering—Proceedings of the ISRM Rock Mechanics Symposium, EUROCK 2024; Tomás, R., Cano, M., Riquelme, A., Pastor, J.L., Benavente, D., Ordóñez, S., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2024; pp. 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, J.; Moormann, C. Classification of the weathering-dependent disintegration behaviour of weak rocks. In Proceedings of the XVII ECSMGE-2019 “Geotechnical Engineering, Foundation of the Future”, Reykjavik, Iceland, 1–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedmüller, G. Neoformations and transformations of clay minerals in tectonic shear zones. TMPM Tschermaks Petr. Mitt. 1978, 25, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtel, T.; Möller, P.; Bürger, M. Veränderlich feste Gesteine als Erdbaustoff—Neuerungen im straßenbautechnischen Regelwerk. In Vorträge zur Erd- und Grundbautagung 2023 (FGSV C 15); FGSV: Köln, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://verlag.fgsv-datenbanken.de/tagungsbaende?kat=Erd-+und+Grundbau&tagungsband=2392&_titel=Ver%C3%A4nderlich+feste+Gesteine+als+Erdbaustoff+%E2%80%93+Neuerungen+im+stra%C3%9Fenbautechnischen+Regelwerk (accessed on 20 July 2025). (In German)

- Song, Q.; Song, K. A Review of the evolution characteristics and argillization of clay interbeds in rockslides. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FGSV. Merkblatt über Veränderlich Feste Gesteine als Erdbaustoff; Road and Transportation Research Association: Cologne, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-86446-293-1. Available online: https://www.fgsv-verlag.de/m-vfg (accessed on 20 July 2025). (In German)

- Knopp, J.; Steger, H.; Moormann, C.; Blum, P. Influence of weathering on pore size distribution of soft rocks. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2022, 40, 5333–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flandes, N.E.; Villalobos, F.A.; King, R. The effect of weathering on the variation of geotechnical properties of a granitic rock from Chile. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2023, 56, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceryan, S.; Tudes, S.; Ceryan, N. A new quantitative weathering classification for igneous rocks. Environ. Geol. 2008, 55, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liao, J.; Xia, C.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L. Micro-meso-macroscale correlation mechanism of red-bed soft rocks failure within static water based on energy analysis. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 6457–6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M. Latest progress of soft rock mechanics and engineering in China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 6, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.R.E.; Sousa, R.L.E.; Zhou, C.; Karam, K. Evaluation of geomechanical properties of soft rock masses by laboratory and In Situ testing. In Soft Rock Mechanics and Engineering; Kanji, M., He, M., Ribeiro e Sousa, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 187–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, I.; Frühwirt, T.; Hölzl, H.; Marcher, T. Argillaceous soft rock in-situ test program in tunneling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 11523–11539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbanas, Ž.; Grošić, M.; Briški, G. Behaviour of engineered slopes in flysch rock mass. In SHIRMS 2008, Proceedings of the First Southern Hemisphere International Rock Mechanics Symposium, Perth, Australia, 16–19 September 2008; Potvin, Y., Carter, J., Dyskin, A., Jeffrey, R., Eds.; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Perth, Australia, 2008; pp. 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, M.; Miao, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Study on large deformation and failure mechanism of deep buried stratified slate tunnel and control strategy of high constant resistance anchor cable. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 144, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selen, L.; Panthi, K.K.; Vistnes, G. An analysis on the slaking and disintegration extent of weak rock mass of the water tunnels for hydropower project using modified slake durability test. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 1919–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Coal Measures mudrocks: Composition, classification and weathering processes. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 1988, 21, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauther, R.; Günther, C. Veränderlich-feste Gesteine als geotechnisches Material am Beispiel des Tonsteins aus Minden (Minden Mudstone as an example of slaking rock material). BAW Mitteilungen 2017, 101, 49–60. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11970/104391 (accessed on 21 July 2025). (In German).

- Miščević, P.; Cvitanović, N.Š.; Vlastelica, G. Degradation processes in civil engineering slopes in soft rocks. In Soft Rock Mechanics and Engineering; Kanji, M., He, M., Ribeiro e Sousa, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T. Testing methods of indurated soils and soft rocks suggestions and recommendations. In Technical Committee on Indurated Soils and Soft Rocks; International Society for Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R. Temperature-induced deterioration mechanisms in mudstone during dry–wet cycles. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 2965–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISRM. International society for rock mechanics commission on standardization of laboratory and field tests: Suggested methods for the quantitative description of discontinuities in rock masses. Int. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1978, 15, 319–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinprecht, V.; Kaspar, M. Advances in remote sensing techniques in engineering geology for infrastructure inspection and site characterization. Geomech. Tunn. 2025, 18, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.N.; Maraun, D.; Knevels, R.; Truhetz, H.; Brenning, A.; Proske, H. Climate change amplified the 2009 extreme landslide event in Austria. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraun, D.; Knevels, R.; Mishra, A.N.; Truhetz, H.; Bevacqua, E.; Proske, H.; Zappa, G.; Brenning, A.; Petschko, H.; Schaffer, A.; et al. A severe landslide event in the Alpine foreland under possible future climate and land-use changes. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickmann, M. Abgrenzung und Klassifizierung Veränderlich Fester Gesteine Unter Ingenieurgeologischen Aspekten; Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, Reihe B—Ingenieurgeologie Hydrogeologie Geothermie, Heft 12; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: Munich, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-89937-112-3. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Nickmann, M.; Baumgärtel, T.; Plinninger, R. Determination of the slaking potential of rock using the combined method of wetting-drying and crystallization tests—Recommendation No. 27 by Commission 3.3. of the DGGT and Working Group 5.1.5 of the FGSV. Geotechnik 2025, 48, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickmann, M.; Spaun, G.; Thuro, K. Untersuchungen zur Klassifizierung veränderlich fester Gesteine unter ingenieurgeologischen Aspekten. In Veröffentlichungen von der 15. Tagung Ingenieurgeologie; Moser, M., Ed.; Friedrich-Alexander-Universität: Erlangen, Germany, 2005; pp. 157–162. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. Standard Test Method for Slake Durability of Shales and Similar Weak Rocks (D 4644-16); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herzel, P. Empfehlung Nr. 20 des Arbeitskreises 3.3 “Versuchstechnik Fels” der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geotechnik e. V.: Zufallsbeständigkeit von Gestein—Siebtrommelversuch. Bautechnik 2002, 79, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.C. Durability-Plasticity Classification of Shales and Other Argillaceous Rocks. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, M.; Tomás, R. Proposal of a new parameter for the weathering characterization of carbonate Flysch-like rock masses: The Potential Degradation Index (PDI). Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 2623–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremias, F.T.; Cripps, J. Laboratory testing and classification of mudrocks: A review. Geotechnics 2023, 3, 781–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersöz, T.; Topal, T. Classification and modification of slake durability test for different types of rocks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 17542-1; Earthworks—Geotechnical Laboratory Tests—Part 1: Degradability Test Standard. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- Ulusay, R. The present and future of rock testing: Highlighting the ISRM Suggested Methods. In The ISRM Suggested Methods for Rock Characterization, Testing and Monitoring: 2007–2014; Ulusay, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, F.S. Bewertung von Boden und Fels auf Verklebungen und Feinkornfreisetzung beim Maschinellen Tunnelvortrieb. Doctoral Dissertation, Ruhr-University, Bochum, Germany, 2014. Available online: https://hss-opus.ub.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/opus4/frontdoor/index/index/year/2018/docId/4036 (accessed on 22 July 2025). (In German).

- Thewes, M.; Hollmann, F.S. Assessment of clay soils and clay-rich rock for clogging of TBMs. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 57, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaton, J.R.; Mishra, S.K. Modified slake durability test for erodible rock material. In Scour and Erosion, Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Scour and Erosion (ICSE-5), San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–10 November 2010; Geotechnical Special Publication No. 210; Burns, S.E., Bhatia, S.K., Avila, C.M.C., Hunt, B.E., Eds.; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2010; pp. 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusay, R.; Arikan, F.; Yoleri, M.F.; Çaǧlan, D. Engineering geological characterization of coal mine waste material and an evaluation in the context of back-analysis of spoil pile instabilities in a strip mine SW Turkey. Eng. Geol. Bull. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1995, 40, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Bofill, J.; Corominas, J.; Soler, A. Behaviour of the weak rock cut slopes and their characterization using the results of the Slake Durability Test. In Engineering Geology for Infrastructure Planning in Europe; Hack, R., Azzam, R., Charlier, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 104; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Niu, X.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, P.; Xia, J.; Lin, Y.; Tang, L.; Nie, Q.; Lin, K. Study on the Disintegration Resistance of Different Types of Schist on the Eastern Slope of the Tongman Open-Pit Mine. Processes 2025, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçoğlu, C.; Ulusay, R.; Sönmez, H. Factors affecting the durability of selected weak and clay-bearing rocks from Turkey, with particular emphasis on the influence of the number of drying and wetting cycles. Eng. Geol. 2000, 57, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Gu, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, Z. Effect of cyclic wetting–drying on tensile mechanical behavior and microstructure of clay-bearing sandstone. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritscher, M. Wasserempfindlichkeit Wechselnd Fester Gesteine des Steirischen Tertiärs. Master’s Thesis, Graz University of Technology, Graz, Austria, 2012. (In German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flügel, H.W.; Neubauer, F. Steiermark: Erläuterungen zur Geologischen Karte der Steiermark 1:200,000; Geological Survey of Austria: Vienna, Austria, 1984; 127p. [Google Scholar]

- Pfleiderer, S.; Reitner, H.; Leis, A. Availability, dynamics and chemistry of groundwater in the Bucklige Welt region of Lower Austria. Austrian J. Earth Sci. 2017, 110, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeiras, A.G. Geology of Kirchberg am Wechsel and Molz Valley Areas (Semmering Window), Lower Austria. Jahrb. Geol. Bundesanst. 1967, 110, 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, R.; Yuan, S.; Yu, S.; Genser, J.; Liu, B.; Guan, Q. The Wechsel Gneiss Complex of Eastern Alps: An Ediacaran to Cambrian continental arc and its Early Proterozoic hinterland. Swiss J. Geosci. 2020, 113, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17892-4; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2016.

- ON B 4810; Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Frost Susceptibility of Mixtures for Unbound Bases for Road and Airfield Construction—Test Methods. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Mutschler, T. Uniaxial compression tests on rock samples—Recommendation No. 1 (revised) of the Commission on Rock Testing of the German Geotechnical Society. Bautechnik 2004, 81, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ON B 3124-9; Testing of Natural Stone; Mechanical Properties of Rock; Modulus of Elasticity, Stress-Strain Curve and Poisson’s Ratio Under Uniaxial Compressive Loading. Austrian Standard International: Vienna, Austria, 1986. Available online: https://www.austrian-standards.at/en/shop/onorm-b-3124-2024-10-01~p3812660 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Spötl, C.; Dublyansky, Y.; Koltai, G.; Honiat, C.; Plan, L.; Angerer, T. Stable isotope imprint of hypogene speleogenesis: Lessons from Austrian caves. Chem. Geol. 2021, 572, 120209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBA. Geodaten—Bundesland Steiermark (1:200,000); Tethys Research Data Repository; Geologische Bundesanstalt (GBA): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoSphere Austria—Bundesanstalt für Geologie, Geophysik, Klimatologie und Meteorologie. Multithematische Geologische Karte von Österreich 1:1,000,000. GeoSphere Austria/CC BY 4.0. 2023. Available online: https://gis.geosphere.at/portal/home/item.html?id=1508ed1e2bf34137a4f62a6c1495eacd (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Vivoda Prodan, M.; Mileusnić, M.; Arbanas, S.M.; Arbanas, Z. Influence of weathering processes on the shear strength of siltstones from a flysch rock mass along the northern Adriatic coast of Croatia. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2017, 76, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.E.; Pineda, J.A.; Cardoso, R. Degradation of marls; two case studies from the Iberian Peninsula. Geol. Soc. Lond. Eng. Geol. Spec. Publ. 2010, 23, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempp, C. Die Entfestigung Überkonsolidierter, Pelitischer Gesteine Süddeutschlands und ihr Einfluß auf die Tragfähigkeit des Straßenuntergrundes. Ph.D. Thesis, University Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 1979. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.A.; Chandra, R. The slake-durability test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1972, 9, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, A.; Liu, G. Laboratory investigation of disintegration characteristics of purple mudstone under different hydrothermal conditions. J. Mt. Sci. 2012, 9, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, S.; Kang, Y.; Liu, X. A prediction model for uniaxial compressive strength of deteriorated rocks due to freeze–thaw. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2015, 120, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Weng, Z. Disintegration Characteristics of Highly Weathered Granite under the Influence of Scouring. Water 2024, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimani, B.; Heinrich, G.; Hofstätter, M.; Kerschbaumer, M.; Kienberger, S.; Leuprecht, A.; Lexer, A.; Peßenteiner, S.; Poetsch, M.S.; Salzmann, M.; et al. Endbericht ÖKS15—Klimaszenarien für Österreich. Daten, Methoden und Klimaanalyse; ZAMG: Vienna, Austria, 2016; ISBN 978-3-903171-02-2. (In German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APCC. Second Austrian Assessment Report on Climate Change (AAR2); Huppmann, D., Keiler, M., Riahi, K., Rieder, H., Eds.; Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, F.; Brugger, K.; Haslinger, K.; Auer, I. The climate of the European Alps: Shift of very high resolution Köppen-Geiger climate zones 1800–2100. Meteorol. Z. 2017, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]