The Influence of Strain Rate Variations on Bonded-Particle Models in PFC

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

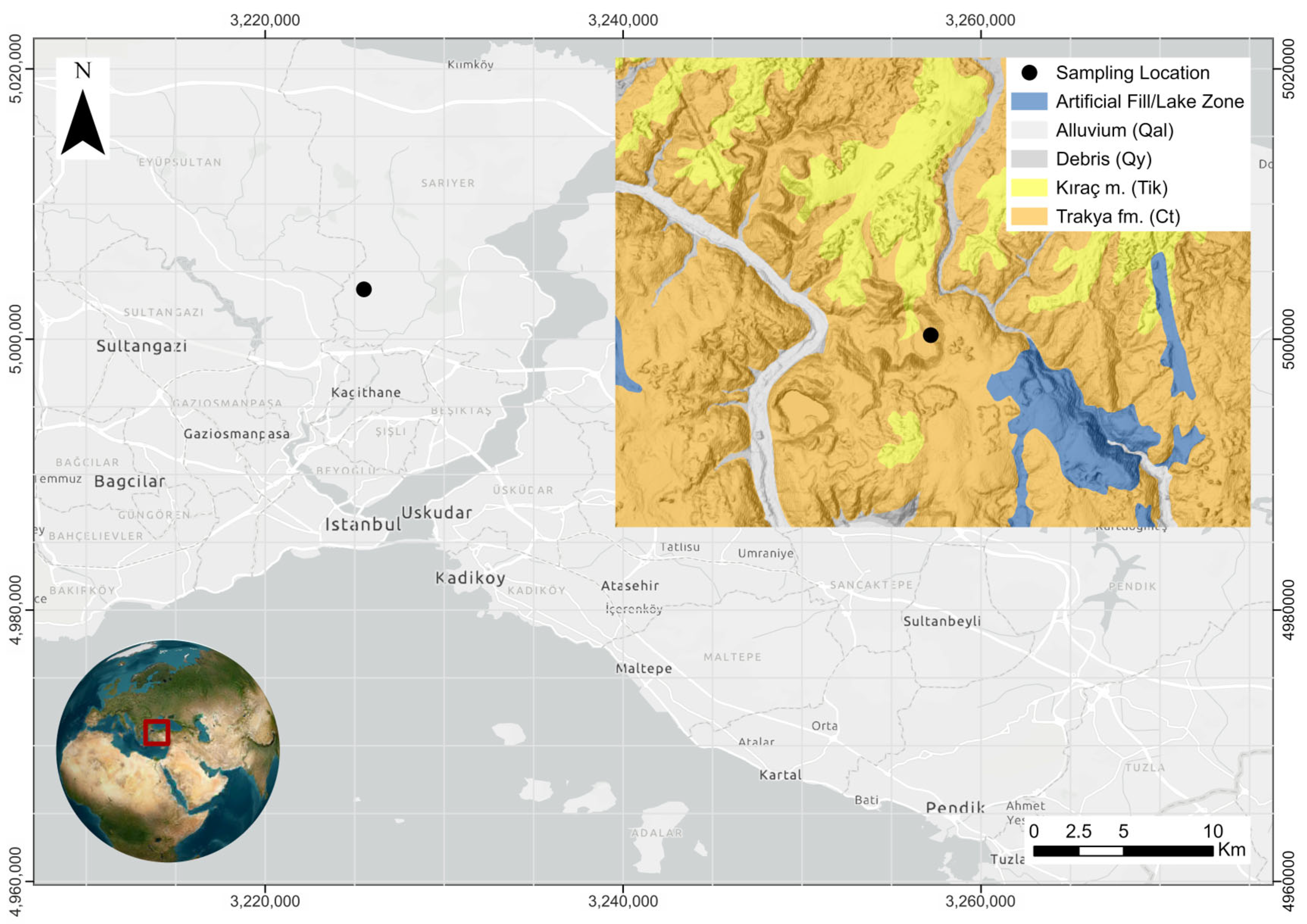

2.1. Rock Material and Specimen Geometry

2.2. Bonded-Particle and Contact Models in PFC

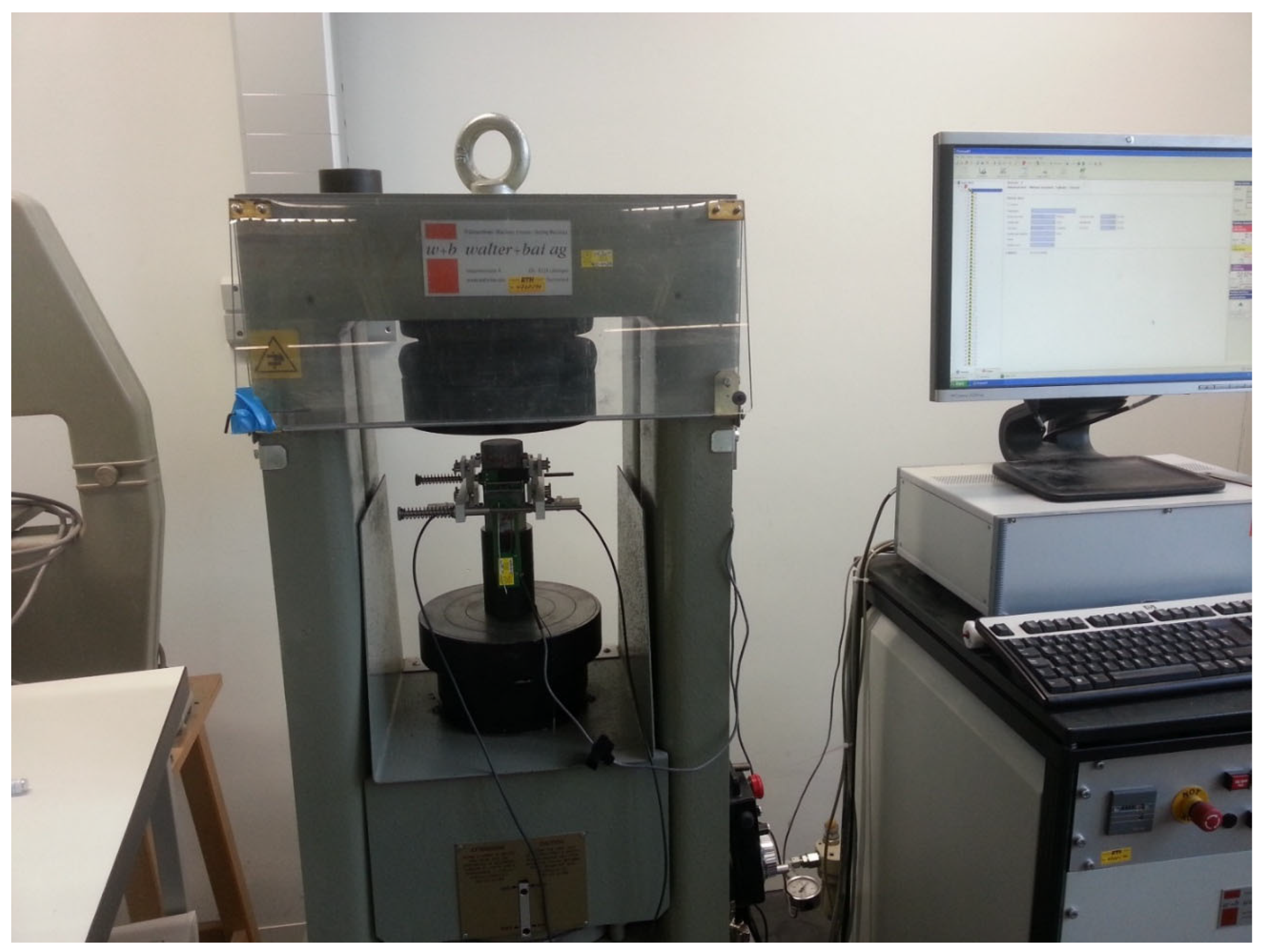

2.3. Calibration and Simulation Setup

3. Results

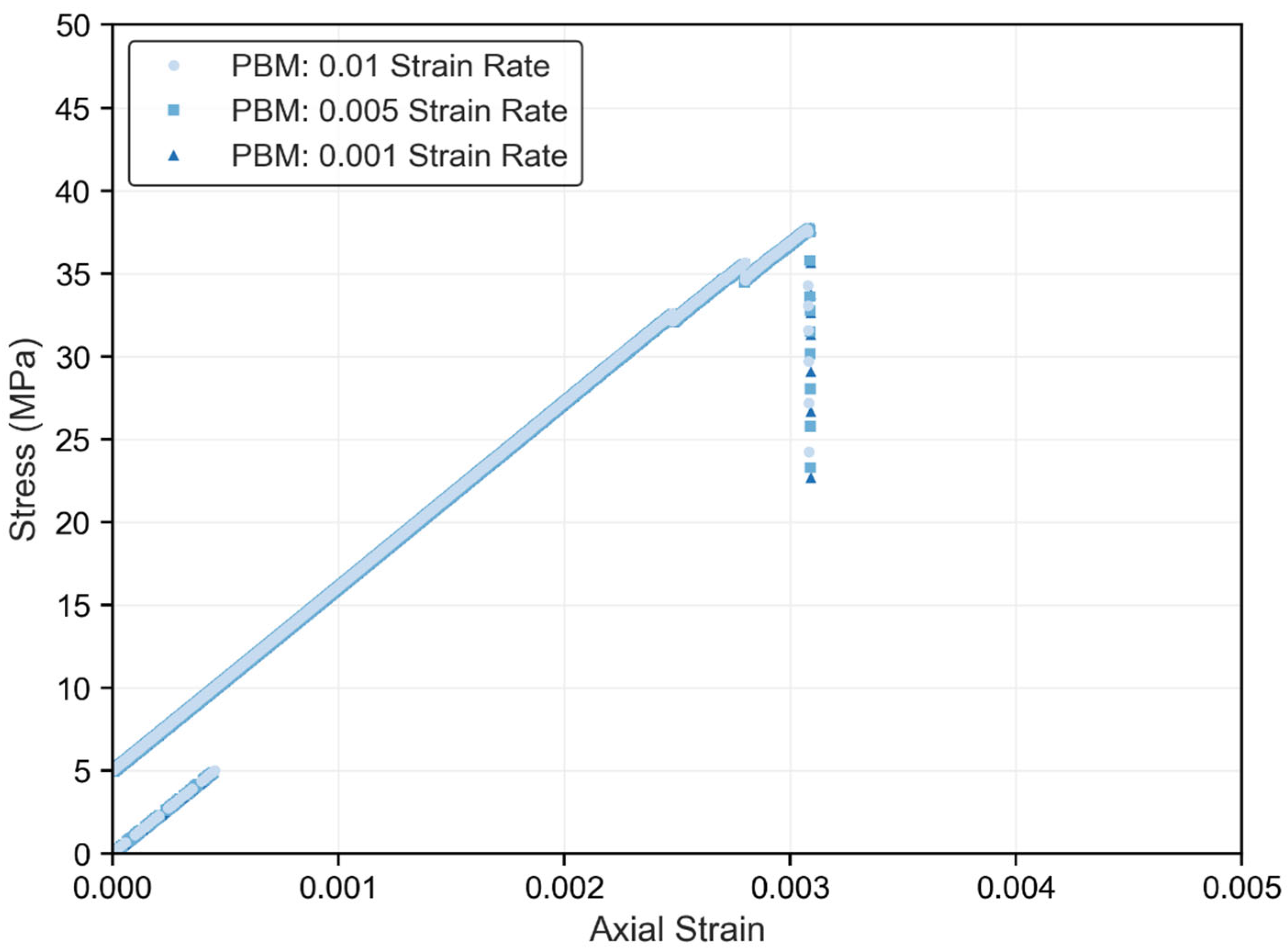

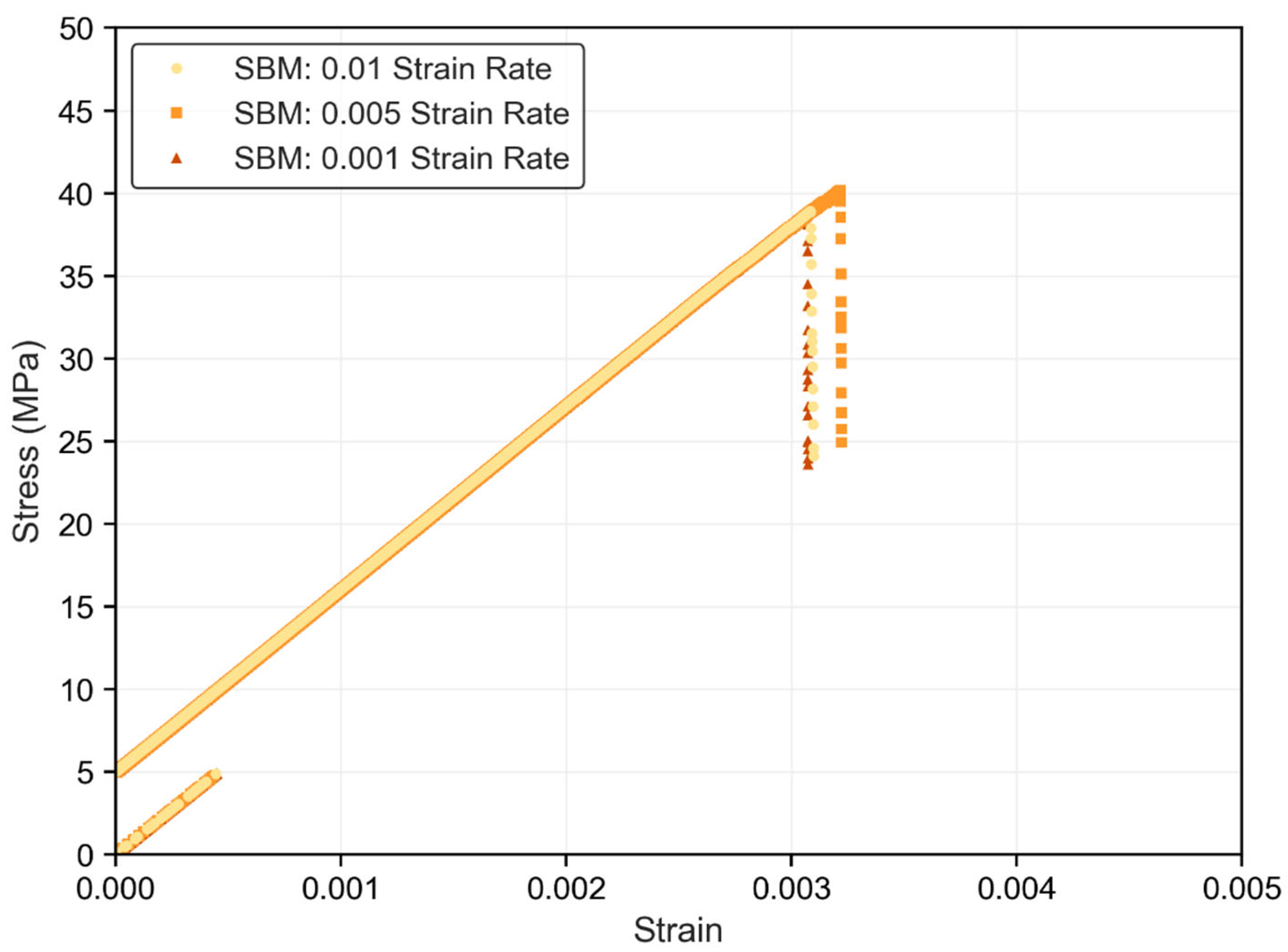

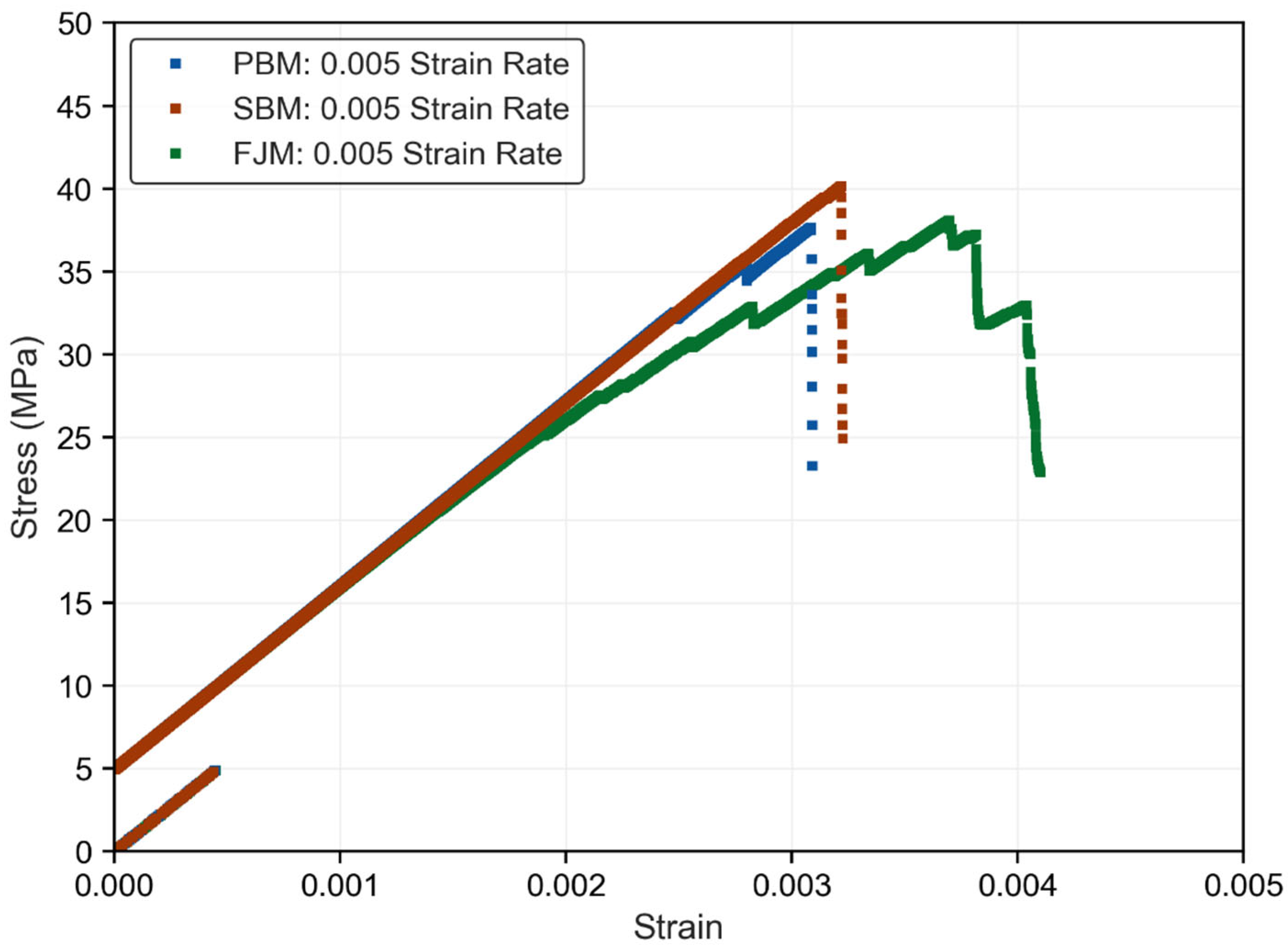

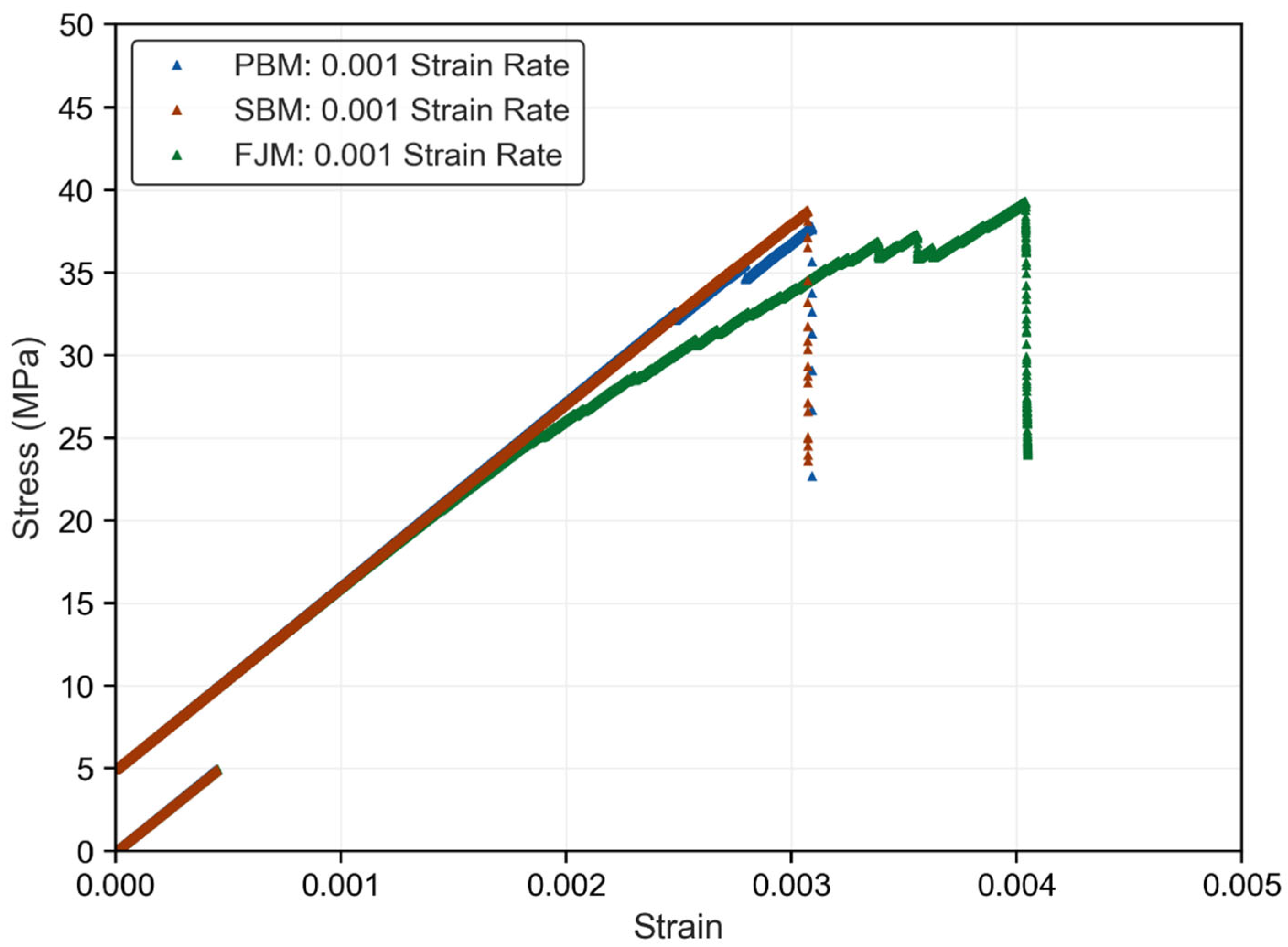

3.1. Rate-Dependent Stress–Strain Behavior of the Models

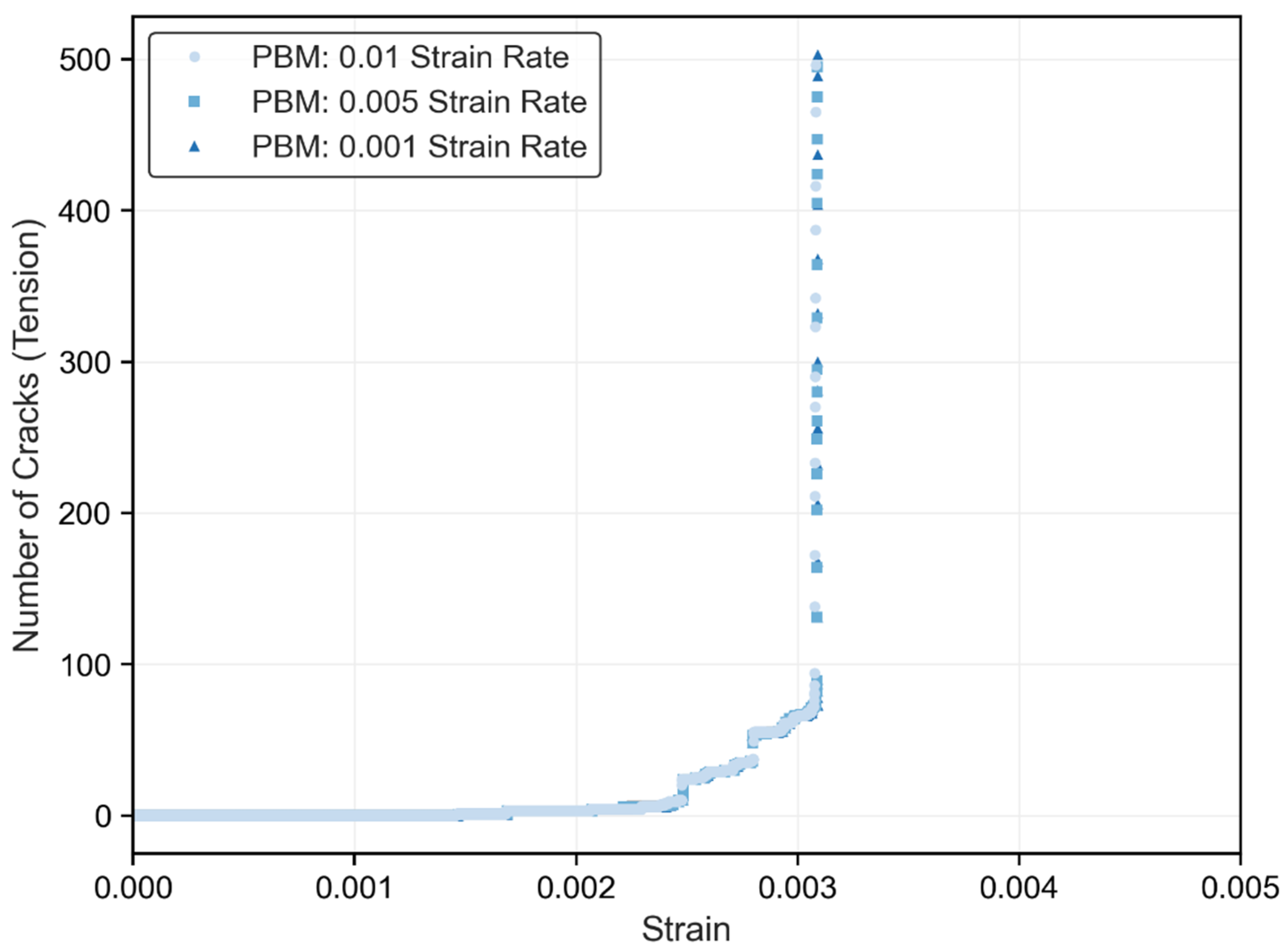

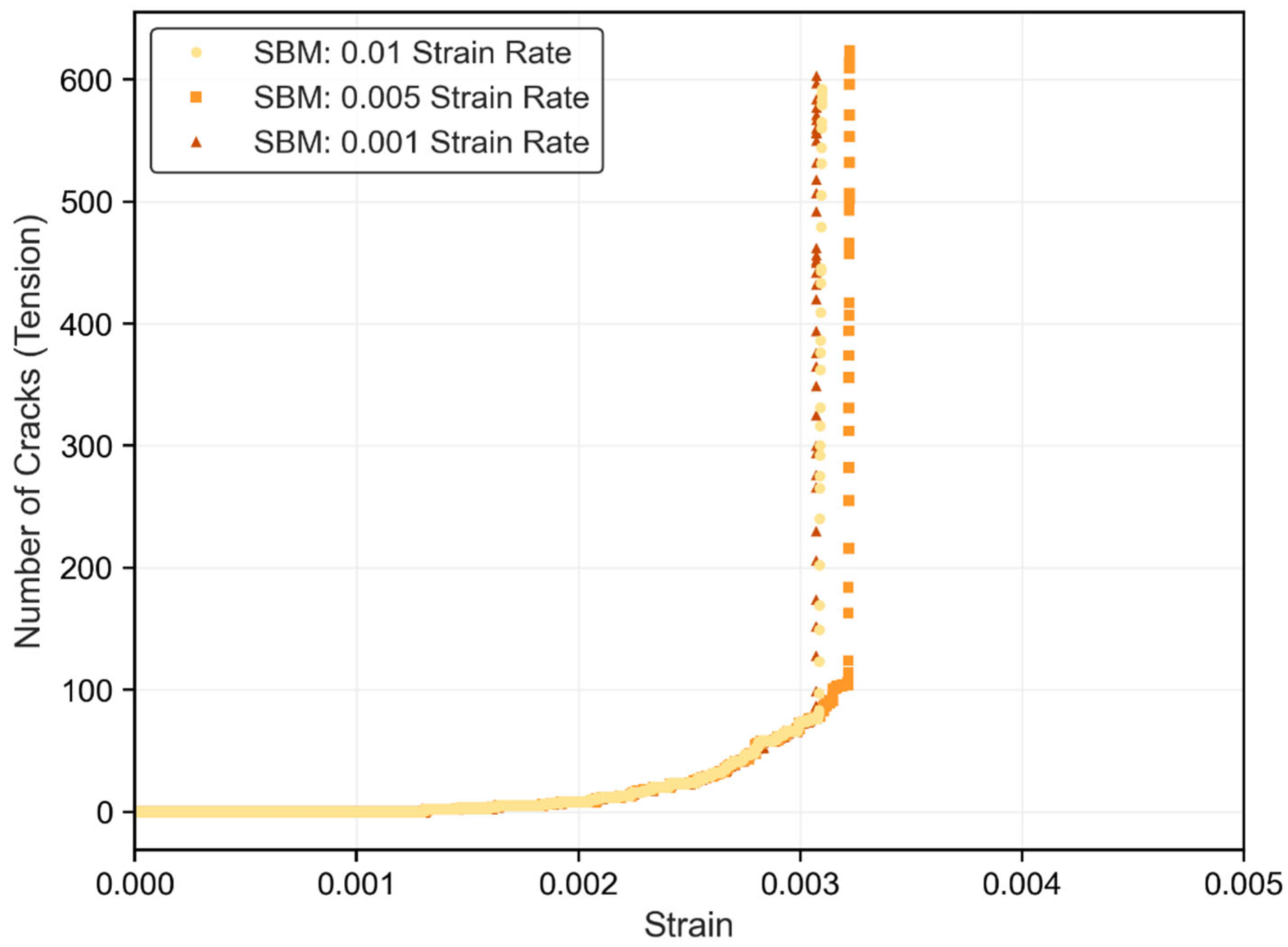

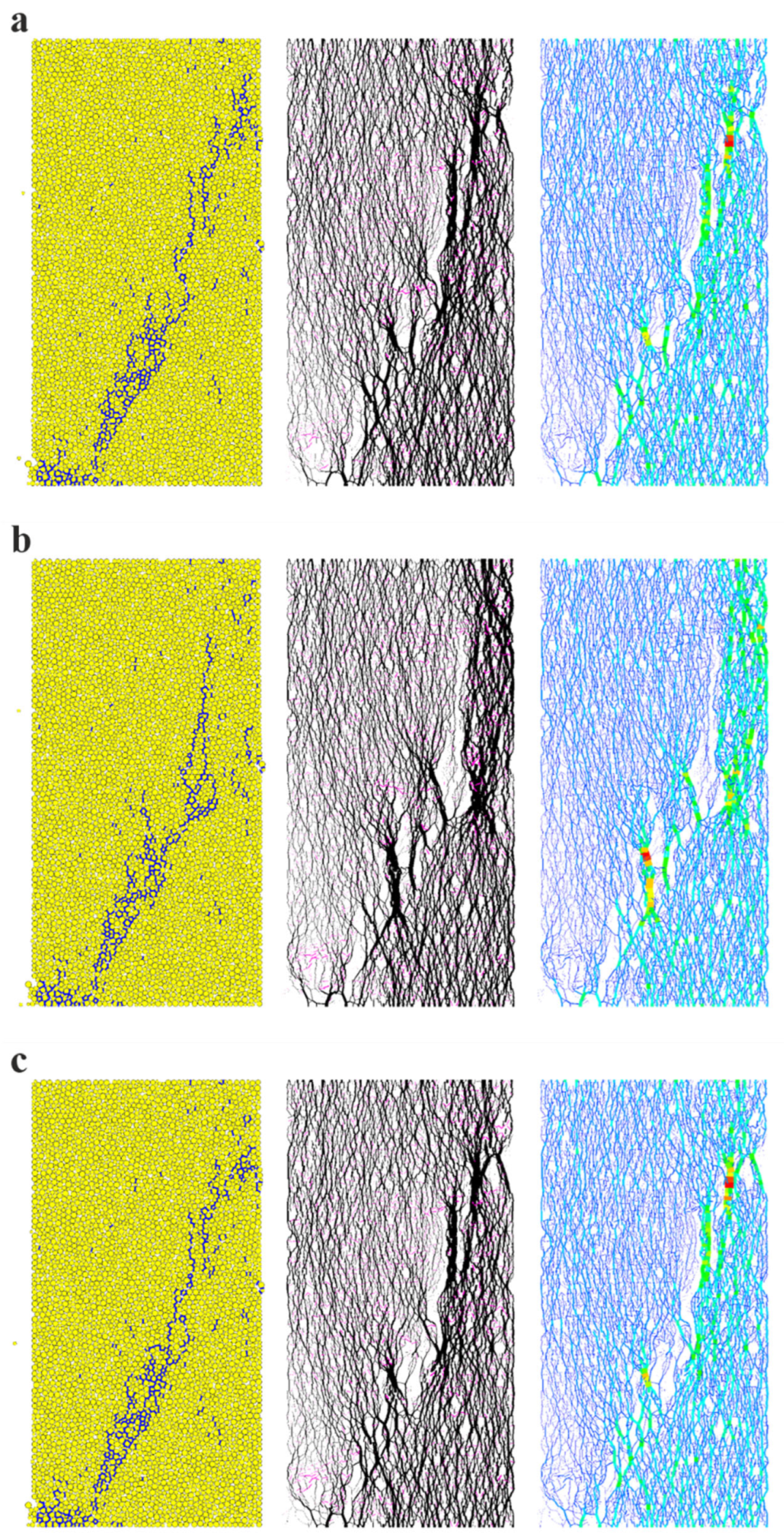

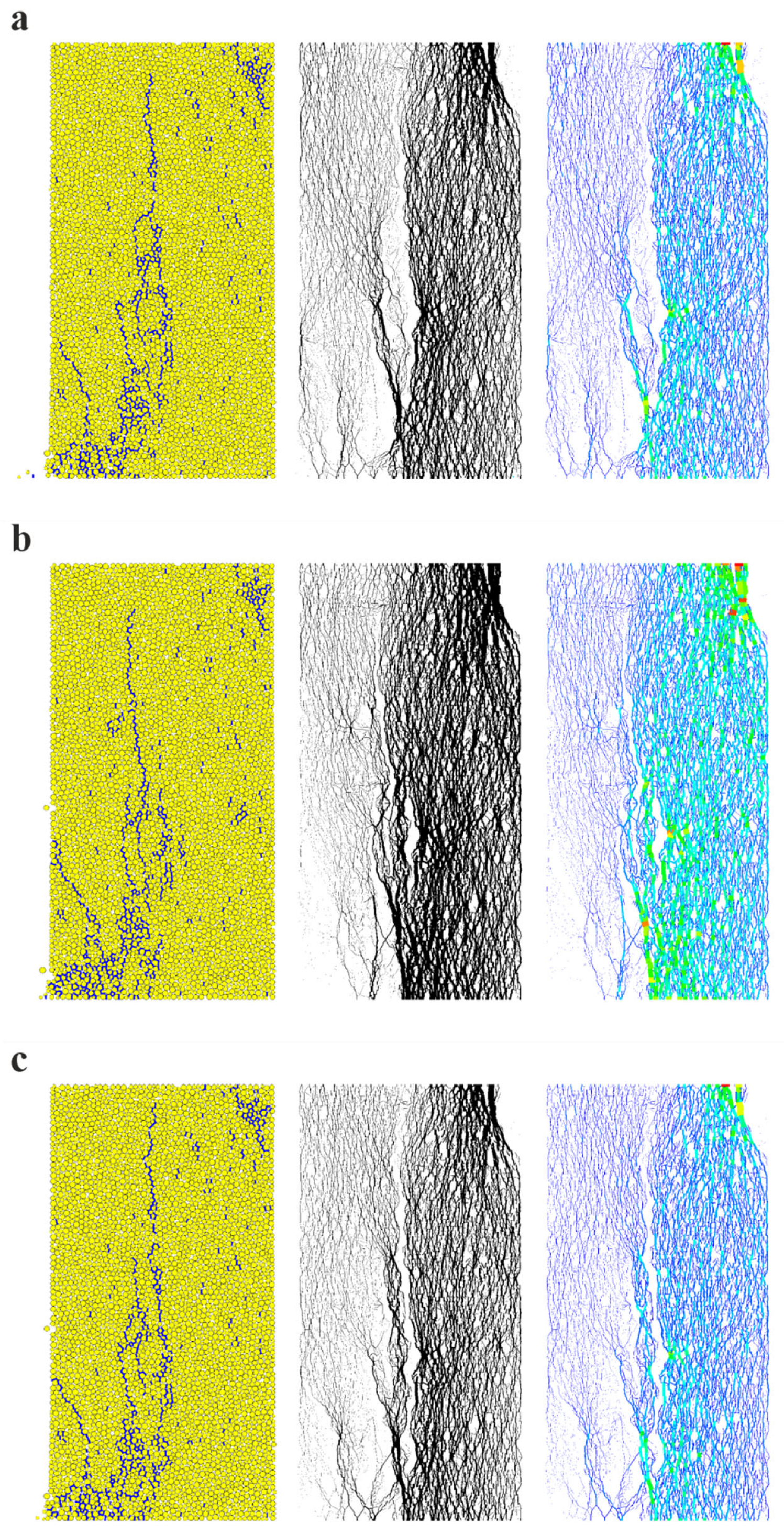

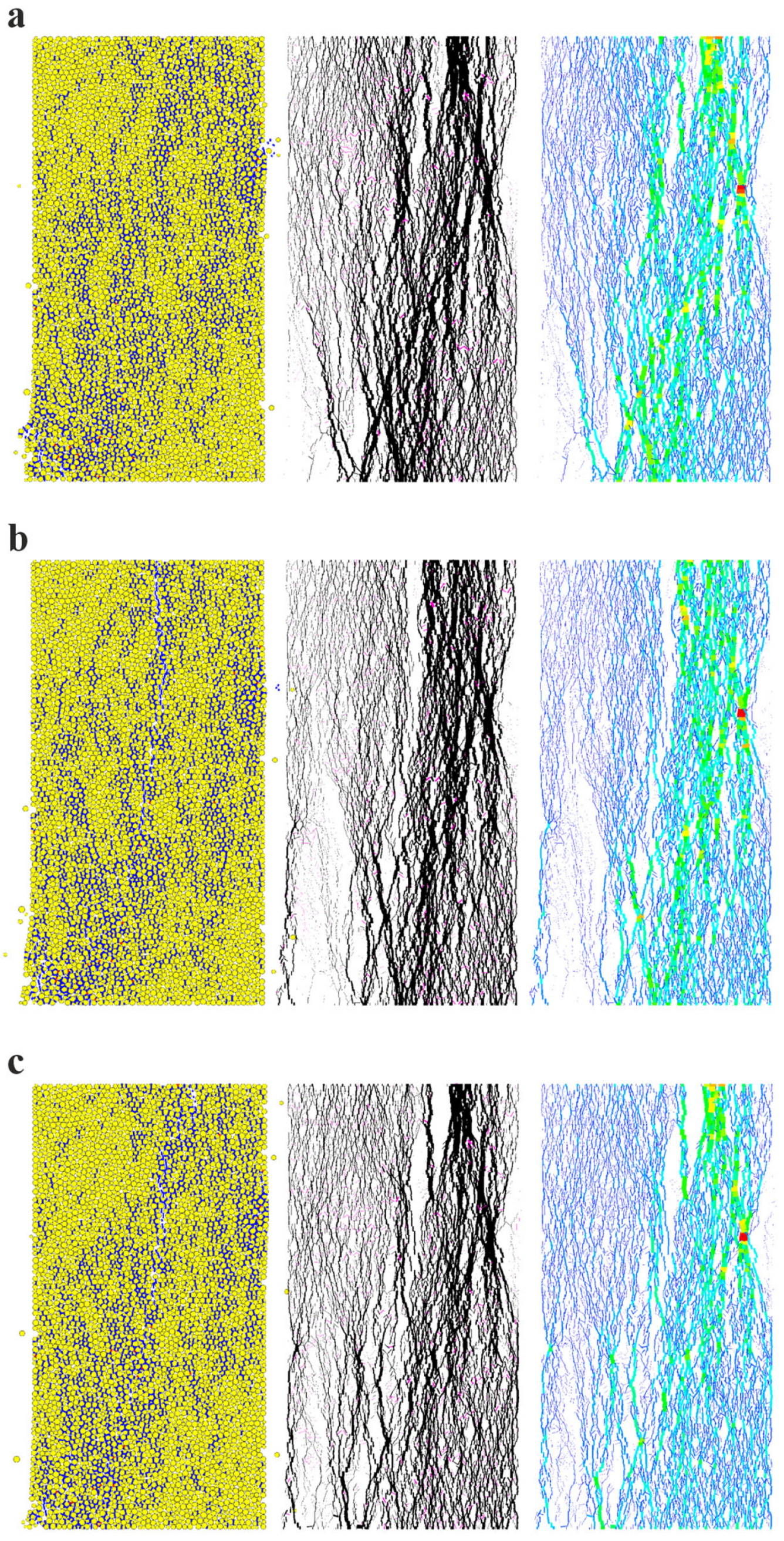

3.2. Crack Evolution Under Different Strain Rates

3.3. Failure Patterns of the Models Based on Strain Rate Variations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, W.G.; Zhao, Y.S.; Xu, S.G.; Dusseault, M.B. Effect of Strain Rate on the Mechanical Properties of Salt Rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C.T.; Smith, M.B. Hydraulic Fracturing: History of an Enduring Technology. J. Pet. Technol. 2010, 62, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.T.; Hoek, E. Underground Excavations in Rock; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Younis, R.M. Empirical Scaling of Formation Fracturing by High-Energy Impulsive Mechanical Loads. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 173, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Ji, Y.; Wu, W.; Kwok, C.Y. Unloading-Induced Failure of Brittle Rock and Implications for Excavation-Induced Strain Burst. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzé, F.V.; Bouchez, J.; Magnier, S.A. Modeling Fractures in Rock Blasting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997, 34, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusay, R. The ISRM Suggested Methods for Rock Characterization, Testing and Monitoring: 2007–2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, O.; Ito, I.; Terada, M. Influence of Strain Rate on Dilatancy and Strength of Oshima Granite under Uniaxial Compression. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1981, 86, 9299–9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajtai, E.Z.; Duncan, E.J.S.; Carter, B.J. The Effect of Strain Rate on Rock Strength. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1991, 24, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, S.; Hashiba, K.; Fukui, K. Loading Rate Dependency of the Strengths of Some Japanese Rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 58, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiba, K.; Fukui, K. Index of Loading-Rate Dependency of Rock Strength. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2015, 48, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O. Simulating Stress Corrosion with a Bonded-Particle Model for Rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2007, 44, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Wong, L.N.Y. Choosing a Proper Loading Rate for Bonded-Particle Model of Intact Rock. Int. J. Fract. 2014, 189, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cai, M. Modeling Time-Dependent Deformation Behavior of Brittle Rock Using Grain-Based Stress Corrosion Method. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 118, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Kong, F.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, B. Effect of Strain Rate on Mechanical Response and Failure Characteristics of Horizontal Bedded Coal under Quasi-Static Loading. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kwok, C.Y.; Duan, K. Rate Effect of Rocks: Insights from DEM Modeling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 181, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O.; Cundall, P.A. A Bonded-Particle Model for Rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 1329–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O. A Flat-Jointed Bonded-Particle Material for Hard Rock. In Proceedings of the 46th US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Chicago, IL, USA, 24–27 June 2012; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Potyondy, D.O. The Bonded-Particle Model as a Tool for Rock Mechanics Research and Application: Current Trends and Future Directions. Geosystem Eng. 2015, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, E. Usability Assessment of Different Contact Models for Modelling the Failure Behaviour of Sedimentary Rocks Under Unconfined Stress Conditions. Yerbilimleri 2022, 43, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lom, N.; Ülgen, S.; Sakinç, M.; Şengör, A.M.C. Geology and Stratigraphy of Istanbul Region. Geodiversitas 2016, 38, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözübol, A.M.; Aysal, N. Cebeciköy Kireçtaşı Ocaklarında Litolojik ve Yapısal Kökenli İşletme Sınırları. İstanbul Yerbilim. Derg. 2008, 21, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ündül, Ö.; Tuzrul, A. The Engineering Geology of Istanbul, Turkey. IAEG 2006 2006, 392, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ündül, Ö.; Çobanoğlu, B.C.; Taz, F. The Differences of Strength and Deformation Properties of Dikes and Host Rocks in the Paleozoic Sequence of Istanbul. Jeol. Muhendisligi Derg. 2018, 42, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ündül, Ö.; Çobanoğlu, B.C.; Taz, F. İstanbul Paleozoyik İstifi’ndeki Dayklar Ile Yan Kayalarının Dayanım ve Deformasyon Özelliklerindeki Farklılıklar. J. Geol. Eng. 2018, 42, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A. A Computer Model for Simulating Progressive Large Scale Movements in Blocky Rock Systems. In Proceedings of the Symposium of the International Society of Rock Mechanics, Nancy, France, 4–6 October 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A Discrete Numerical Moder for Granular Assemblies. Geotechnique 1979, 1, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A. UDEC: A Generalized Distinct Element Program for Modelling Jointed Rock; Report PCAR-I-80, Peter Cundall Associates Report; European Research Office, US Army: Washington, DC, USA, 1980; Contract, DAJA37-79-C-0548. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y. PFC2D Simulation on Stability of Loose Deposits Slope in Highway Cutting Excavation. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, E.; Erguler, Z.A. Effect of Gap Geometries on the Crack Initiation Stress of Synthetic Rock Material. In Proceedings of the European Geosciences Union 2021, Virtual, 19–30 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, L.; Wei, J.; Pu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L.; Mi, X. Stress Evolution in Rocks around Tunnel under Uniaxial Loading: Insights from PFC3D-GBM Modelling and Force Chain Analysis. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 134, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; He, L.; Zhao, H. A Theory of Slope Shear Scouring and the Failure Mechanism of PFC3D on a Gangue Slope. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.M.; Kjølaas, J.; Larsen, I.; Li, L.; Gotusso Pillitteri, A.; Sønstebø, E.F. Comparison between Controlled Laboratory Experiments and Discrete Particle Simulations of the Mechanical Behaviour of Rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2005, 42, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, H.; Crosta, G.B. Numerical Modeling of Rock Mechanical Behavior and Fracture Propagation by a New Bond Contact Model. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 78, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, H. DEM Analysis of Failure Mechanisms in the Intact Brazilian Test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 102, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaaddini, M.; Sheikhpourkhani, A.M.; Mansouri, H. Flat-Joint Model to Reproduce the Mechanical Behaviour of Intact Rocks. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 1427–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.T. Rock Characterization Testing and Monitoring. ISRM Suggested Methods; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; ISBN 0080273084. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. Application of Experimental Design and Optimization to PFC Model Calibration in Uniaxial Compression Simulation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2007, 44, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, J.A.; Suzuki, K.; Brzovic, A.; Ivars, D.M. Application of Synthetic Rock Mass Modeling to Veined Core-Size Samples. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2016, 81, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, C. Calibration of the Discrete Element Method: Strategies for Spherical and Non-Spherical Particles. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 851–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O. Parallel-Bond Refinements to Match Macroproperties of Hard Rock. In Proceedings of the 2nd FLAC/DEM Symposium, Melbourne, Australia, 14–16 February 2011; pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Potyondy, D.O. A Grain-Based Model for Rock: Approaching the True Microstructure. In Proceedings of the Bergmekanikk i Norden 2010—Rock Mechanics in the Nordic Countries, Kongsberg, Norway, 9–12 June 2010; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, X.T.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, S.; Wu, W. Rockmass Damage Development Following Two Extremely Intense Rockbursts in Deep Tunnels at Jinping II Hydropower Station, Southwestern China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2013, 72, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbaum, U. Stress-Rate Dependency of Uniaxial Compressive Strength of Hard Rock with Regard to Test Procedure Standards. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 82, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Wong, L.N.Y. Loading Rate Effects on Cracking Behavior of Flaw-Contained Specimens under Uniaxial Compression. Int. J. Fract. 2013, 180, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wei, J.; Niu, L.; Li, S.; Li, S. Numerical Simulation on Damage and Failure Mechanism of Rock under Combined Multiple Strain Rates. Shock. Vib. 2018, 2018, 4534250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cebeciköy Siltstone | PBM | SBM | FJM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak strength (MPa) | 37.83 | 38.95 | 37.94 | 38.32 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 3.78 | 9.80 | 10.02 | 3.61 |

| Young Modulus (GPa) | 11.30 | 11.54 | 11.09 | 10.91 |

| Micro Parameter | PBM | SBM | FJM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum grain size | 0.8 × 10−3 | 0.8 × 10−3 | 0.8 × 10−3 |

| Maximum grain size | 1.6 × 10−3 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 1.6 × 10−3 |

| Radius multiplier | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Bond effective modulus | 8.3 × 109 | 1.5 × 1010 | 1.5 × 1010 |

| Bond normal-to-shear stiffness ratio | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Moment-contribution factor | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| Tensile strength | 3.0 × 107 | 3.3 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| Cohesion/Tensile strength ratio | 10 | 20 | 8.25 |

| Friction coefficient | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ündül, Ö.; Zengin, E. The Influence of Strain Rate Variations on Bonded-Particle Models in PFC. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040082

Ündül Ö, Zengin E. The Influence of Strain Rate Variations on Bonded-Particle Models in PFC. Geotechnics. 2025; 5(4):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜndül, Ömer, and Enes Zengin. 2025. "The Influence of Strain Rate Variations on Bonded-Particle Models in PFC" Geotechnics 5, no. 4: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040082

APA StyleÜndül, Ö., & Zengin, E. (2025). The Influence of Strain Rate Variations on Bonded-Particle Models in PFC. Geotechnics, 5(4), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040082