Abstract

Background/Objectives: Running is one of the most popular physical activities worldwide and have been widely studied in relation to performance and injury prevention. In addition to measurements conducted under standardized laboratory conditions, inertial measurement units (IMUs) allow for the assessment of biomechanical parameters in real-world settings—particularly during endurance runs. The aim of this study was to investigate how running a half-marathon under field conditions affects exertion and various biomechanical parameters, as measured using IMUs. Methods: Twenty runners completed a half-marathon on a flat, even-surfaced walkway at a self-selected, constant pace corresponding to a brisk training run. In addition to lower limb biomechanics, heart rate (HR) and ratings of perceived exertion (REP) were also recorded. Results: A significant increase in both HR and RPE was observed toward the end of the half-marathon, indicating the presence of fatigue during the later stages of the run. The biomechanical results further demonstrate that this fatigue was associated with increased peak tibial acceleration, peak angular velocity in the sagittal plane of the foot, and peak rearfoot eversion velocity, while foot strike angle, stride frequency, and stride length remained unchanged. Furthermore, a progressive increase in ground contact time and a decrease in flight time were observed over the course of the run, resulting in an increased duty factor. Conclusions: These findings highlight the value of IMU-based assessments for detecting fatigue-related biomechanical changes during prolonged runs in real-world conditions, which may contribute to early identification of overload and inform injury prevention strategies.

1. Introduction

Running is one of the most widely practiced forms of physical activity and is associated with substantial health benefits. Beyond its health-promoting effects, the appeal of competition and performance comparison has become increasingly prominent, as evidenced by the growing number of marathon or half-marathon participants worldwide [1,2,3]. However, running also carries a notably high incidence of overuse injuries, with prevalence ranging from 19.4% to 92.4% among distance runners [4]. This is likely attributable in part to increased training volumes and intensities during competition preparation phases, although the relationship between training load and injury risk remains a subject of ongoing debate [5,6].

Given the multifactorial etiology of overuse injuries, attention has increasingly turned to biomechanical parameters that may act as modifiable risk factors.

In this context, several studies have focused on biomechanical parameters in distance running particularly in relation to muscular fatigue, which naturally accumulates during prolonged endurance runs or at higher intensities, in healthy, recovered, and acutely symptomatic runners [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

One of these biomechanical parameters is peak tibial acceleration (PTA), which provides information on how the shock wave resulting from the forces at initial ground contact (IC) propagates through the lower extremities and allows inferences about the internal forces acting on the musculoskeletal system [24,25]. Thereby, excessive values in PTA have been associated with increased mechanical strain on the tibia and surrounding structures, potentially predisposing athletes to bone stress injuries [11,26,27,28,29,30]. The influence of muscular fatigue on PTA has been examined primarily during running on treadmills or indoor running tracks, with inconsistent results. While some investigations suggest that muscular fatigue induces adaptations in running mechanics—reflected in increased PTA values [9,11]—other studies have not reported consistent evidence of such changes [7,12]. To date, apart from indoor running studies, only a few investigations have addressed PTA during endurance running in real-world settings, likewise with inconsistent results. For example, Morio et al. [18] reported no change in PTA during field running, whereas Ruder et al. [22] observed a decrease at the end of an endurance run.

In addition to the impact loading parameter PTA, it is also relevant to consider the influence of muscular fatigue on kinematic measures such as peak eversion velocity (evVel), peak angular velocity in the sagittal plane (PAV), and foot strike angle (FSA). In this context, several studies have shown that with increasing muscular fatigue, evVel increases significantly [10,11,31], whereas FSA may decrease significantly [12,20,32]. No recent study could be identified that examined the influence of muscular fatigue on PAV. However, this parameter is highly relevant as it reflects the foot rollover in the sagittal plane [33]. It may provide insights into the ability to actively decelerate plantarflexion after IC, a function that relies on the dorsiflexors and may be impaired by their fatigue, which in turn can influence shock absorption [34].

Furthermore, fatigue-related changes in spatiotemporal parameters—including step frequency (SF), ground contact time (tC), flight time (tF), and duty factor (DF)—are of particular interest, as they represent fundamental descriptors of running mechanics. They are generally stable at constant speeds but may show subtle changes under muscular fatigue, which can reflect compensatory strategies and influence running efficiency or injury risk [7,8,9,11,12,18]. However, the existing literature reports inconsistent findings regarding these adaptations, which may be partly explained by differences in methodological approaches such as running speed, exercise intensity, or running surface.

As shown, most studies investigating the effects of muscular fatigue on the above-mentioned biomechanical parameters have been conducted on treadmills or indoor running tracks, often with inconsistent results [7,8,9,10,11,15,17]. Further investigations have been carried out under field conditions, likewise reporting inconsistent findings or not including relevant parameters of impact loading (e.g., PTA) and foot rollover kinematics (e.g., evVel) in conjunction with spatiotemporal parameters [13,14,19,20,21,23].

These inconsistencies point to a broader issue: muscular fatigue appears to elicit different biomechanical responses depending on the running context. Specifically, the existing literature indicates that biomechanical adaptations in response to muscular fatigue may differ between treadmill and field running. This suggests that changes in parameters such as PTA are strongly influenced by the study design—particularly the running surface, speed, and intensity. Supporting this, higher PTA values have been reported during outdoor running compared to treadmill conditions [35,36,37]. Consequently, biomechanical variables associated with overuse injuries—such as medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) or tibial stress fractures (TSF)—identified through laboratory-based gait analysis may not accurately reflect their magnitudes during field running. To address this limitation, studies conducted in natural environments (e.g., on streets or sidewalks) are necessary to investigate how muscular fatigue influences biomechanical parameters under ecologically valid conditions [38]. Furthermore, a review by Xiang et al. [39] highlighted that, beyond impact parameters such as PTA or ground reaction forces, a holistic approach should be adopted by integrating additional biomechanical aspects, with inertial measurement units (IMUs) providing a promising tool for this purpose.

In this context, IMUs, which combine accelerometers and gyroscopes, offer a particularly suitable solution for field-based research due to their compact size and lightweight design, as has been demonstrated in several field-based studies [13,18,33,36,37].

As demonstrated above, previous findings remain inconsistent, underscoring a crucial gap in knowledge regarding how fatigue affects running biomechanics under field conditions. This highlights the need for approaches that enable the comprehensive assessment of multiple biomechanical parameters outside the laboratory. Therefore, the aims of this study were twofold: (1) to investigate whether IMUs are suitable for capturing a broad range of biomechanical parameters during a half-marathon run under field conditions, extending beyond the more limited approaches used in previous research, and (2) to examine how such a run affects exertion and the above mentioned biomechanical parameters. It was hypothesized (I) that both heart rate and perceived exertion would significantly increase with the duration of the run. With respect to biomechanics, it was hypothesized (II) that PTA would significantly increase from the beginning to the end of the run as a result of acute muscular fatigue and a reduced capacity to absorb impact forces. Furthermore, it was hypothesized (III) that foot kinematics—specifically, evVel and PAV—would increase over the course of the run due to progressive muscular fatigue in the lower extremities, whereas the FSA would decrease. Regarding spatiotemporal parameters, it was hypothesized (IV) that, despite a constant running speed, increasing fatigue during a half marathon would lead to a decrease in strLen and tF, while SF and tC would increase. We also hypothesized (V) that exertion parameters are correlated with biomechanical parameters.

This study aims to demonstrate the potential of IMU-based systems for continuous, field-based monitoring of running biomechanics under fatigue conditions during prolonged endurance runs. Understanding how biomechanical parameters change under real-world conditions provides valuable insights for injury prevention in endurance runners. In addition, the findings may inform training strategies and fatigue monitoring through real-time feedback to promote safer and more efficient running over longer distances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In summary, 20 runners without any injuries in the last six months were recruited for this study. Demographic and running-related characteristics of the runners are presented in Table 1. Participants ran an average of 36.8 ± 21.8 km per week. During the half-marathon run, the average running speed was 11.4 ± 0.9 km/h.

Table 1.

Demographic and running-related characteristics of the runners (mean ± SD).

The runners were informed about the purpose and design of this study, signed an informed consent document, and completed a form with their personalized data. All procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chemnitz University of Technology (#101627696).

2.2. Experimental Setup and Procedures

2.2.1. Running

Data acquisition took place on a straight, flat concrete sidewalk approximately 1.4 km in length. Following an individual warm-up period of 5 to 10 min, each participant completed 15 laps on the sidewalk, totaling the official half-marathon distance of approximately 21.1 km. Running speed was self-selected and corresponded to each runner’s typical training pace, as suggested in previous studies [10,18]. Participants were instructed to choose a running pace they could maintain continuously over the entire half-marathon distance without the need to stop; however, a minimum speed of 10 km/h was required. The running speed was constantly checked by the experimenter on a bicycle with a speedometer [33,36]. During the half-marathon run, participants used their own running shoes. Runners rated their perceived exertion (RPE) on a 15-point Borg scale (from 6 to 20) at the beginning of the run and after each lap [40]. Furthermore, participants wore a Garmin Forerunner® 735XT (Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA) equipped with an external heart rate sensor (HRM-Pro™ Plus, Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA) to monitor heart rate (HR).

2.2.2. Sensor Setup

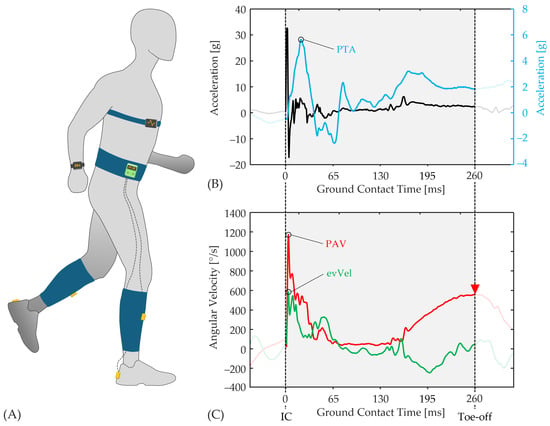

Based on Hill et al. [36], four small, lightweight inertial measurement units (IMU; ICM-20601, InvenSense, San Jose, CA, USA; weight: 4 g; sampling rate: 2000 Hz) combining a tri-axial accelerometer (measurement range: ±353 m/s2) and a tri-axial gyroscope (measurement range: ±4000°/s) were used to measure biomechanical data (Figure 1A). All IMUs were connected via cables to a data logger, which was secured on a belt around the participant’s waist. According to Kiesewetter et al. [41], one IMU was attached to the shaved medial aspect of each tibia, midway between the malleolus and tibial plateau, using double-sided adhesive tape, an elastic strap, and a compression sleeve to minimize sensor movement. The sensor axes were aligned with the longitudinal axes of the tibia. Additionally, an IMU was mounted on the heel cap of each running shoe using double-sided adhesive tape and secured with additional elastic tape.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the setup with inertial measurement units (IMUs), data logger, Garmin Forerunner®, and heart rate sensor; (B) Vertical acceleration data from the heel-mounted IMU (black line) as well as from the tibia-mounted IMU (blue line), showing peak tibial acceleration (PTA); (C) Angular velocities from the heel-mounted IMU in the frontal plane (green line) and sagittal plane (red line), used to determine peak rearfoot eversion velocity (evVel) and peak angular velocity for foot rollover sagittal (PAV). Toe-off was defined as maximum angular velocity in the sagittal plane, >100 ms post IC (red triangle). A sample dataset was used for illustration.

2.3. Data Analysis

Raw data from the IMUs were analyzed post-processing using MATLAB 2024a (MathWorks™, Natick, MA, USA). Prior to analysis, signals were filtered to reduce noise using a zero-lag, 4th-order Butterworth low-pass filter—applied at 80 Hz for accelerometer data and 50 Hz for gyroscope data [41].

Biomechanical Parameters

For accurate detection of IC and stride segmentation, the vertical acceleration signal from the heel-mounted IMU was further processed using a zero-lag Butterworth high-pass filter at 80 Hz. The first prominent peak in the filtered signal was identified as IC, ensuring a valid detection of foot strike events for subsequent gait analysis [42]. The stride duration (strD) was then calculated as the time between two consecutive ICs. In addition, the SF was calculated as the inverse of the time between two consecutive ICs, multiplied by two (assuming that the right and left legs have the same step duration). According to Sabatini et al. [43], toe-off was identified as the point at which the angular velocity in the sagittal plane of the foot-mounted sensor reaches its maximum value, occurring at least 100 ms after IC (Figure 1C). Furthermore, tC was defined as the interval between IC and the corresponding toe-off event, while tF was computed as follows (1):

tF = strD − tC

The duty factor (DF), representing the proportion of time the foot is in contact with the ground during a stride, was used to assess mechanical work [20,44]. A higher DF indicates a longer tC, whereas a lower DF reflects longer tF and reduced tC. The following Equation (2) was used to calculate the relative DF:

DF = tC (tF + tC)−1 * 100%

The highest peak in the vertical acceleration signal of the tibia-mounted sensor was defined as PTA (Figure 1B). To assess evVel, the maximum angular velocity in the frontal plane of the shoe-mounted sensor was analyzed [45] (Figure 1C). For foot rollover, PAV was determined within 100 ms after IC, following the approach described by Bräuer et al. [33] (Figure 1C). To determine the FSA at IC, the orientation of the shoe in the sagittal plane was calculated using angular velocity data from the heel-mounted IMU [46]. This signal was integrated to obtain the foot angle (θ). To correct for integration drift and offset, a nulling algorithm was applied using two consecutive stance phases where the foot was flat on the ground, identified by minimal changes in θ. A linear offset correction between these points was subtracted from θ. FSA was then defined as the corrected orientation angle at IC. A detailed description of this procedure can be found in Mitschke et al. [46]. The drift- and offset-corrected θ signal, along with the corresponding vertical and horizontal acceleration data, was used to calculate strLen between two consecutive ICs [46]. Due to technical issues (such as cable breakage or sensor failures) occurring during testing, all biomechanical parameters were calculated based on data from only one leg per runner.

2.4. Statistics

Each runner completed a total of 15 laps. For each lap, means were calculated for all biomechanical parameters. Subsequently, for lap 1 as well as laps 8 and 15, group means and standard deviations (mean ± SD) were calculated across all runners. The three laps represent different race segments: the start (L1), running in a “non-fatigued state”, running in the middle of the race (L8), and running in a “fatigued state” (L15). This segmentation into three phases was based on the approach of Prigent et al. [20].

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, Version 30.0). All data were visually inspected and tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In cases where normality was confirmed, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to compare the three laps (L1, L8, and L15), followed by a Bonferroni-corrected post hoc test. If the assumption of normality was violated, the Friedman test was applied for the same laps, with subsequent Dunn-Bonferroni tests used for post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all analyses. In addition, effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated to quantify the magnitude of differences when statistical significance was found. The coefficients were interpreted as trivial (d < 0.2), small (d < 0.5), medium (d < 0.8), or large effects (d ≥ 0.8) [47]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess linear relationships between exertion parameters (RPE and HR) and biomechanical parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Exertion Parameters

Table 2 presents the results for the exertion parameters. For both parameters, the lowest values were observed in L1 and the highest in L15. The ANOVA revealed significant differences across laps. Subsequent post hoc tests showed significant pairwise differences between all laps, with large effect sizes (d > 0.98).

Table 2.

Effects of running duration and muscular fatigue on heart rate (HR) and perceived exertion (RPE) (mean ± SD). Statistically significant group differences are indicated with *, while significant differences between laps 1 (L1), 8 (L8), and 15 (L15) are marked with a, b, and c, respectively; effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported for the respective pairwise comparisons.

3.2. Biomechanical Parameters

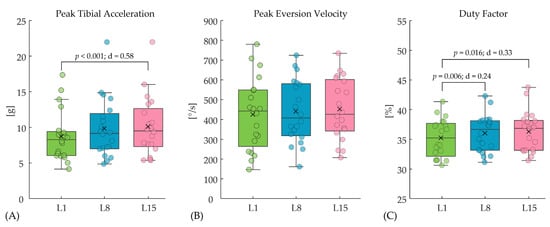

The biomechanical parameters for the three examined segments of the half-marathon are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. An increase in PTA over the course of the run was measured. ANOVA revealed significant differences between L1 and L15 (p < 0.001) with a medium effect size (d = 0.58). For both evVel and PAV, increases in angular velocities were observed from L1 to L15. While evVel showed only a trend toward higher velocities, PAV exhibited significant differences between all three laps (L1 vs. L8: p = 0.046; L1 vs. L15: p = 0.011; L8 vs. L15: p = 0.024), with trivial (L8 vs. L15: d = 0.012) to small effect sizes (L1 vs. L8: d = 0.31; L1 vs. L15: d = 0.42). No significant difference in FSA was found between the laps (p = 0.210).

Table 3.

Effects of running duration and muscular fatigue on peak tibial acceleration (PTA), peak eversion velocity (evVel), peak angular velocity in the sagittal plane (PAV), and foot strike angle (FSA) (mean ± SD). Statistically significant group differences are indicated with *, while significant differences between laps 1 (L1), 8 (L8), and 15 (L15) are marked with a, b, and c, respectively; effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported for the respective pairwise comparisons.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the three examined laps of the half-marathon (L1, L8, and L15) for the biomechanical parameters (A) peak tibial acceleration, (B) peak eversion velocity, and (C) duty factor.

Table 4 presents the results for spatiotemporal parameters. No significant differences were found for strLen (p = 0.484) and SF (p = 0.210). Moreover, neither parameter showed an increasing or decreasing trend over the three laps. For tC, a significant increase with a small effect size was observed between laps L1 and L8 (p = 0.022; d = 0.29) as well as between L1 and L15 (p = 0.044; d = 0.34). In contrast, tF significantly decreased over the course of the run from lap L1 to L8 (p = 0.036; d = 0.15) and from L1 to L15 (p = 0.020; d = 0.23). For DF, ANOVA revealed significant differences between L1 and L8 (p = 0.006) as well as between L1 and L15 (p = 0.016), both indicating small effect sizes (L1 vs. L8: d = 0.24; L1 vs. L15: d = 0.33) (Figure 2C).

Table 4.

Effects of running duration and muscular fatigue on spatiotemporal parameters stride length (strLen), step frequency (SF), ground contact time (tC), flight time (tF), and duty factor (DF) (mean ± SD). Statistically significant group differences are indicated with *, while significant differences between laps 1 (L1), 8 (L8), and 15 (L15) are marked with a and b, respectively; effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported for the respective pairwise comparisons.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate the relationships between exertion parameters and biomechanics. Moderate positive correlations were found between evVel and both RPE (ΔL15–L1: r = 0.49, p = 0.030) and HR (ΔL15–L1: r = 0.45, p = 0.045). Other biomechanical parameters showed very low correlation coefficients with RPE and HR, none of which reached statistical significance.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that muscular fatigue can substantially influence running biomechanics, which has been associated with performance reduction and a potentially elevated risk of injury [48]. In the present study, muscular fatigue was induced by having participants run a half-marathon. By using of IMUs, biomechanical data could be collected under real-world conditions, which resulted in findings with higher ecological validity. For the half-marathon run, the running speed was set individually for each participant to correspond to a brisk training run but was limited to a speed that allowed the run to be completed without interruption. Maintaining a constant running speed throughout the entire run was essential to avoid speed-related confounding effects on parameters such as PTA, strLen, SF, and others. It was hypothesized that (I) exertion parameters (II) impact loading, (III) kinematics, and (IV) spatiotemporal parameters change as fatigue progressed. Furthermore, we hypothesized that there is a correlation between exertion parameters and biomechanical parameters (V).

4.1. Exertion Parameters

During the half-marathon run, a significant increase in fatigue was observed from L1 to L8 and L15, as indicated by raised exertion parameters HR and RPE, both demonstrating large effect sizes (Table 2). Therefore, it can be assumed that the runners experienced a high level of physiological fatigue, particularly towards the end of the run. This assumption is supported by significant fatigue-related changes in several biomechanical parameters. Based on the significant increase and the large effect in exertion parameters, Hypothesis (I) can be confirmed.

4.2. Impact Loading

At each foot strike, especially at IC, the lower extremities experience impact forces several times body weight within a short time [49,50]. During prolonged runs, this mechanical loading contributes to muscular fatigue, which reduces the ability of the muscles to effectively attenuate impact forces [8]. In this context, Mizrahi et al. [34] demonstrated that muscle fatigue of the shank, including the tibialis anterior, was associated with a reduction in the mean power frequency of electromyographic activity—an established indicator of muscular fatigue. At the same time, their study reported a significant increase in PTA. It can be concluded that such muscular fatigue results in a diminished or delayed shock-attenuation response. Our study revealed a significant increase in PTA throughout the run, corresponding to a medium effect size (Table 3). This indicates that increased muscular fatigue in the lower extremities was pronounced in our study, making it more difficult for the runners to effectively absorb and manage shock waves generated during each foot strike. Therefore, our findings provide support for confirming Hypothesis (II).

Our findings are consistent with previous studies conducted on treadmills [9,11]. For example, Derrick et al. [11] investigated PTA during an exhaustive treadmill run. Muscular fatigue resulted in a significant 20.7% increase in PTA at the end of the run. While PTA values may be lower due to the treadmill setting, where reduced maxima are expected compared to sidewalk running [35,36,37], the fatigue-induced increase remains comparable to that observed in our study. Furthermore, Mizrahi et al. [9] demonstrated that fatigue during a 30 min treadmill run led to an approximately 50% increase in PTA, suggesting that fatigue significantly amplifies mechanical loading on the shank and may elevate the risk of overload injuries. The higher PTA increase reported in the referenced study was probably due to the intensity being above the anaerobic threshold, in contrast to our study, where participants should run at lower intensity (below anaerobic threshold) for a longer duration.

Similarly to our study, Morio et al. [18] investigated PTA during a continuous run conducted on a road. However, in contrast to our findings, the authors did not observe any significant changes in PTA by the end of the running session. In their study, participants ran at their self-selected constant speed, similar to a typical 1 h training run. Apparently, the duration of the run (1 h) or the running speed was too low and thus the level of fatigue was insufficient to elicit a significant increase in PTA. The authors explained the low RPE values as an indication that the exercise intensity was not high enough to induce substantial fatigue [18]. In contrast, Ruder et al. [22] reported a pronounced level of fatigue in their participants, who completed a full marathon. Toward the end of the run, a significantly reduced PTA was observed. The authors attributed the approximately 15% decrease in PTA to a corresponding 15% reduction in running speed at the end of the race, likely resulting from fatigue-induced performance decline. Subsequently, the authors normalized PTA to running speed and showed that, after adjusting for speed, PTA remained unchanged toward the end of the run. This observation further highlights the contrast to the results of the present study, where PTA increased despite a constant running speed.

4.3. Kinematics

Regarding kinematics, only PAV increased significantly with running duration (Table 3). This change likely reflects fatigue-induced alterations in neuromuscular control, particularly involving the tibialis anterior. The ability to actively decelerate the plantarflexion after IC appeared to diminish, likely due to compromised eccentric control by the dorsiflexors, leading to progressively higher angular velocities across the analyzed segments. The PAV values observed in this study are in line with previously reported findings, such as those examining the influence of running shoes on biomechanics (757.8–814.1°/s) [41] or assessing foot rollover characteristics (845.6–919.5°/s) [33], when measured using IMUs. However, no comparable values for PAV during prolonged runs could be found in the existing literature.

Notably, despite the significant increase in PAV, the FSA remained unchanged throughout the run, suggesting that runners maintained a consistent foot strike pattern despite muscular fatigue (Table 3). FSA values are comparable to those reported in the literature [41,51,52].

To date, only a limited number of studies have examined how muscular fatigue affects FSA. For example, Prigent et al. [20] reported a significant reduction in FSA during a road half-marathon run. This reduction suggests a flatter foot placement at IC. During treadmill running, Hazzaa and Mattes [32] observed a significant reduction in FSA following muscular fatigue, particularly when the plantarflexors were fatigued. Furthermore, Giandolini et al. [12] reported that a 110 km ultramarathon induced significant FSA adaptations depending on foot strike pattern: non-rearfoot strikers showed an increase, while rearfoot strikers showed a decrease, resulting in convergence between groups. In contrast, other studies have reported no change in FSA with increasing fatigue. For example, Camelio et al. [7] observed no change in FSA before and after a 30 min submaximal treadmill run. The authors attributed this to the low intensity (approx. 12/20 on RPE scale), which may not have been sufficient to induce muscular fatigue affecting FSA.

In summary, FSA can be influenced by muscular fatigue when the level of exertion is sufficiently high, and this effect appears to depend on the foot strike pattern. In our study, all runners exhibited FSA > 15° at baseline, indicating a consistent rearfoot striking; thus, further subdivision was unnecessary. Although exertion increased substantially (RPE: 15.9 ± 2.2), no significant FSA changes were observed. Even when participants were subdivided into higher- and lower-fatigue groups (RPE > 16 or HR > 165 bpm), results for FSA remained inconsistent.

Overall, the findings do not provide consistent evidence that localized muscle fatigue induces measurable changes in FSA. Comparable results were found for evVel. Although a slight increasing trend was observed across all runners on average, the change was not statistically significant (Table 3). Generally, similar values for evVel have been reported in other studies [31,41,45]. Only few studies have investigated the effects of muscular fatigue on evVel. For example, Shih et al. [31] reported a significant increase during an intense 30 min treadmill run, with strong correlations to RPE and HR (r = 0.911 and r = 0.960). Our finding showed similar associations between evVel and exertion, though with moderate correlation strength. These results suggest that increasing exertion is linked to higher evVel, potentially reflecting fatigue-related adaptations in lower limb control, even though evVel did not significantly change across laps.

Derrick et al. [11] also observed a significant increase in evVel during an exhaustive treadmill run. The relative increase (12.6%) was larger than in our study (6.4%), which may be explained by their higher running speeds, as evVel is known to rise with speed (12.2 km/h vs. 11.4 km/h) [45]. In contrast, Dierks et al. [10] reported markedly lower evVel in runners with and without patellofemoral pain (PFP), likely due to slower running speeds (~9 km/h). In both groups, evVel increased significantly during the run, with similar relative changes, suggesting no specific effect of PFP on evVel. Generally, the current evidence regarding biomechanical risk factors for running-related injuries remains conflicting [5]. In particular, there is limited evidence regarding the relationship between muscular fatigue and running-related injuries.

As our results indicate, a significant effect of muscular fatigue was observed only for PAV. For evVel, a trend toward higher values at the end of the run was found, as also reflected in the correlations between evVel and HR as well as rating of RPE. In contrast, no fatigue-related effect was evident for the FSA. Therefore, Hypothesis (III) can only be partially accepted.

4.4. Spatiotemporal Parameters

Regarding spatiotemporal parameters, the results of this study indicate that both SF and strLen remained constant throughout the half-marathon, despite progressive muscular fatigue (Table 3). This suggests that running speed was maintained consistent across the entire race.

The influence of fatigue on spatiotemporal parameters has been reported controversially in the literature. Our results on SF and strLen align with previous studies showing stable spatiotemporal parameters at consistent running speeds [7,11]. In contrast, other studies have reported that muscular fatigue leads to an increase in SF, which is often accompanied by a reduction in strLen [9,12,18]. SF has been proposed to increase as a compensatory strategy to reduce fatigue-related impact forces [18], serving as a protective mechanism against musculoskeletal loading. In this context, Verbitsky et al. [8] reported a decrease in SF in fatigued runners after a 30 min treadmill run near the anaerobic threshold, while it remained stable in a non-fatigue group. These findings, together with the absence of significant SF or strLen changes in our study and others (e.g., [7]), suggest that participants may not have reached sufficient fatigue to alter these parameters. However, Derrick et al. [11] reported very similar findings to our study during an exhaustive run. The authors observed an increase in PTA towards the end of the run, while both strLen and SF remained unchanged. Furthermore, the runners in their study exhibited a lower knee angle (higher flexion), a higher evVel as well as an increased rearfoot eversion angle at IC—findings that are consistent with the results of evVel observed in our study. According to the authors, changes in knee and subtalar joint angles at IC likely reduced the effective mass of the lower limb during impact, which in turn may have contributed to the observed increases in leg impact accelerations and shock attenuation. The authors emphasize that an increase in measured PTA does not necessarily indicate a higher injury risk if it results from a reduction in effective mass [11]. Since it is primarily the impact forces—rather than the accelerations—that are associated with injury risk, an elevated PTA under these conditions does not inherently imply increased mechanical load on the body.

A similar mechanism may help explaining the findings of the present study. In the present study, we observed increased PTA, evVel, and PAV during the later stages of the half-marathon run, while SF, strLen, and FSA remained unchanged. These findings suggest that muscular fatigue may have contributed to both a reduction in effective mass—through subtle kinematic changes such as increased knee flexion—and to less controlled and faster foot rollover movements in both the frontal (evVel) and sagittal planes (PAV). The combination of a reduced effective mass and increased segmental angular velocities likely led to the observed increase in PTA, despite the absence of changes in both strLen and SF.

In contrast to strLen and SF, both tC increased and tF decreased significantly over the course of the run, leading to a significant rise in DF. DF represents the proportion of the gait cycle spent in ground contact (Equation (2)). At constant running speed, a higher DF suggests a shift toward a more compliant or cautious running pattern, characterized by lower leg stiffness, increased knee flexion at IC, and vertical displacement, and reduced vertical ground reaction forces [11,53]. Additionally, muscular fatigue—particularly in the plantarflexors and hip extensors—could delay the push-off phase, contributing to a longer stance duration [54]. This prolonged tC may serve as a stabilizing strategy in the presence of reduced neuromuscular control, but may also facilitate the transmission of higher impact accelerations, as observed in the increased PTA. Similar observations have been reported by Möhler et al. [55] and Giovanelli et al. [19]: In both studies, SF remained constant, while tC increased and tF decreased, resulting in a higher DF. In the study by Möhler et al. [55], tC increased significantly, while tF decreased. Likewise, Giovanelli et al. [19] found a comparable shift during a mountain run, with tC increasing and tF decreasing, despite constant running speed and SF.

Based on our findings regarding the spatiotemporal parameters, Hypothesis (IV) can also only be partially accepted.

4.5. Limitations and Recommendations

This study has a few limitations. Firstly, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the study population. Since participants were primarily recreational runners with speeds between 10 and 13 km/h, results may not apply to elite athletes or slower beginners. The broad variability in fitness levels likely increased variance and reduced effect sizes. Future studies may benefit from recruiting more homogeneous subgroups (e.g., novice or experienced runners) to reduce variability. Additionally, instead of self-selected speeds, future protocols could include an incremental test prior to data collection, allowing testing at a defined relative intensity (e.g., near the anaerobic threshold) to ensure comparable loading across participants and enhance validity [9,34,40]. Secondly, one limitation of the measurement system was cable breakage in some participants due to mechanical stress on the connections, which restricted analysis to one leg. Future studies should consider using more robust cables or potentially wireless systems to allow for bilateral data collection and the assessment of interlimb coordination. However, any wireless system must provide sufficiently high sampling frequency to ensure accurate data acquisition [46]. Thirdly, the study by Derrick et al. [11] demonstrated that muscular fatigue is associated with increased knee flexion. We adopted this assumption. In future research, an IMU on each thigh could enable measurement of knee joint angles and investigation of fatigue effects on knee kinematics during prolonged running under field conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of IMU-based systems for continuous, field-based monitoring of running biomechanics under real-world fatigue conditions. Unlike previous studies limited by pre–post comparisons, laboratory constraints, or assessed only a narrow range of variables, our findings provide ecologically valid insights into the biomechanical adaptations occurring during prolonged endurance runs. The results demonstrate that muscular fatigue in the latter stages of a half-marathon is associated with increased PTA, PAV, and evVel, while FSA, SF and strLen remained unchanged. These changes likely reflect a reduction in effective mass and less controlled segmental motion. The observed increase in DF may indicate a fatigue-related adaptation through prolonged tC, potentially linked to reduced leg stiffness and delayed push-off.

From a practical perspective, these findings have several important implications for athletes, coaches, clinicians, and physiotherapists. The continuous monitoring of PTA, PAV, and evVel during real-time running opens new opportunities for early detection of fatigue-related deterioration in movement quality. This enables timely interventions—such as gait adjustments or terminating a training session—to prevent overload. Furthermore, the observed increases in segmental angular velocities underline the importance of targeted training for distal lower limb muscles to maintain control under fatigue. Strength and plyometric training aimed at preserving leg stiffness and reducing tC may further enhance fatigue resistance. Additionally, bilateral data collection offers valuable insight into asymmetric loading patterns, which may signal compensatory mechanisms or emerging imbalances. Early identification of such patterns can contribute to individualized training strategies and effective injury prevention.

Overall, this study highlights the practical value of IMU technology for analyzing fatigue-related biomechanical changes and preventing running-related overuse injuries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K., C.M. and T.L.M.; methodology, P.K. and C.M.; software, C.M.; validation, P.K. and C.M.; formal analysis, P.K., C.M. and T.H.; investigation, P.K.; resources, P.K. and C.M.; data curation, P.K. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, P.K., C.M., T.L.M. and T.H.; visualization, T.H.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, P.K., C.M. and T.L.M.; funding acquisition, T.L.M. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Chemnitz University of Technology (reference number #101627696).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the runners for their dedication to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PTA | Peak tibial acceleration |

| evVel | Peak eversion velocity |

| FSA | Foot strike angle |

| PAV | Peak angular velocity in the sagittal plane |

| SF | Stride frequency |

| strLen | Stride length |

| DF | Duty Factor |

| tC | Ground contact time |

| tF | Flight time |

| IC | Initial ground contact |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| PFP | Patellofemoral pain |

| MTSS | Medial tibial stress syndrome |

| TSF | Tibial stress fractures |

| bpm | Beats per minute |

References

- Hennig, E.M. Eighteen years of running shoe testing in Germany—A series of biomechanical studies. Footwear Sci. 2011, 3, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-J.; Yang, F.; Gao, Y.; Su, Y.-F.; Sun, W.; Jia, S.-W.; Wang, Y.; Lam, W.-K. Gender and Age Differences in Performance of Over 70,000 Chinese Finishers in the Half- and Full-Marathon Events. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, D.; Rüst, C.; Cribari, M.; Rosemann, T.; Lepers, R.; Knechtle, B. Differences in participation and performance trends in age group half and full marathoners. Chin. J. Physiol. 2014, 57, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gent, R.N.; Siem, D.; van Middelkoop, M.; van Os, A.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Koes, B.W. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 469–480, discussion 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyssens, L.; Vanelderen, R.; Barton, C.; Malliaras, P.; Dingenen, B. Biomechanical Risk Factors Associated with Running-Related Injuries: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1095–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredette, A.; Roy, J.-S.; Perreault, K.; Dupuis, F.; Napier, C.; Esculier, J.-F. The Association Between Running Injuries and Training Parameters: A Systematic Review. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 650–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camelio, K.; Gruber, A.H.; Powell, D.W.; Paquette, M.R. Influence of Prolonged Running and Training on Tibial Acceleration and Movement Quality in Novice Runners. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbitsky, O.; Mizrahi, J.; Voloshin, A.; Treiger, J.; Isakov, E. Shock Transmission and Fatigue in Human Running. J. Appl. Biomech. 1998, 14, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.; Verbitsky, O.; Isakov, E.; Daily, D. Effect of fatigue on leg kinematics and impact acceleration in long distance running. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2000, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierks, T.A.; Manal, K.T.; Hamill, J.; Davis, I. Lower extremity kinematics in runners with patellofemoral pain during a prolonged run. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, T.R.; Dereu, D.; McLean, S.P. Impacts and kinematic adjustments during an exhaustive run. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giandolini, M.; Gimenez, P.; Temesi, J.; Arnal, P.J.; Martin, V.; Rupp, T.; Morin, J.-B.; Samozino, P.; Millet, G.Y. Effect of the Fatigue Induced by a 110-km Ultramarathon on Tibial Impact Acceleration and Lower Leg Kinematics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reenalda, J.; Maartens, E.; Homan, L.; Buurke, J.H.J. Continuous three dimensional analysis of running mechanics during a marathon by means of inertial magnetic measurement units to objectify changes in running mechanics. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 3362–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan-Roper, M.; Hunter, I.; W Myrer, J.; L Eggett, D.; K Seeley, M. Kinematic changes during a marathon for fast and slow runners. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2012, 11, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.L.-W.; Wong, D.W.-C.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Q.; Lam, W.-K.; Zhang, M. Changes in segment coordination variability and the impacts of the lower limb across running mileages in half marathons: Implications for running injuries. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, E.C.; van den Bogert, A.J.; Hamill, J. Kinematic adaptations during running: Effects of footwear, surface, and duration. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.-B.; Samozino, P.; Millet, G.Y. Changes in running kinematics, kinetics, and spring-mass behavior over a 24-h run. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morio, C.Y.-M.; Garcia, S.; Flores, N. Effects of one-hour road running and shoe on tibial accelerations in recreational runners. ISBS Proc. Arch. 2020, 38, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli, N.; Taboga, P.; Rejc, E.; Simunic, B.; Antonutto, G.; Lazzer, S. Effects of an Uphill Marathon on Running Mechanics and Lower-Limb Muscle Fatigue. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016, 11, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigent, G.; Apte, S.; Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Besson, C.; Gremeaux, V.; Aminian, K. Concurrent Evolution of Biomechanical and Physiological Parameters With Running-Induced Acute Fatigue. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 814172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya-Cuartero, J.; Pueo, B.; Villalon-Gasch, L.; Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M. Stability of Running Stride Biomechanical Parameters during Half-Marathon Race. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruder, M.; Jamison, S.T.; Tenforde, A.; Mulloy, F.; Davis, I.S. Relationship of Foot Strike Pattern and Landing Impacts during a Marathon. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2073–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong Lempke, A.F.; Hunt, D.L.; Willwerth, S.B.; d’Hemecourt, P.A.; Meehan, W.P.; Whitney, K.E. Biomechanical changes identified during a marathon race among high-school aged runners. Gait Posture 2024, 108, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, E.M.; Milani, T.L.; Lafortune, M.A. Use of Ground Reaction Force Parameters in Predicting Peak Tibial Accelerations in Running. J. Appl. Biomech. 1993, 9, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.A.; Bates, B.T.; Dufek, J.S.; Hreljac, A. Characteristics of shock attenuation during fatigued running. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.; Milner, C.; Hamill, J. Does increased loading during running lead to tibial stress fractures? A prospective study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, S58. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, M.B.; Mullineaux, D.R.; Milner, C.E.; Hamill, J.; Davis, I.S. Biomechanical predictors of retrospective tibial stress fractures in runners. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacoff, A.; Reinschmidt, C.; Nigg, B.M.; van den Bogert, A.J.; Lundberg, A.; Denoth, J.; Stüssi, E. Effects of foot orthoses on skeletal motion during running. Clin. Biomech. 2000, 15, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vtasalo, J.T.; Kvist, M. Some biomechanical aspects of the foot and ankle in athletes with and without shin splints. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983, 11, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, C.E.; Ferber, R.; Pollard, C.D.; Hamill, J.; Davis, I.S. Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.; Ho, C.-S.; Shiang, T.-Y. Measuring kinematic changes of the foot using a gyro sensor during intense running. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzaa Walaa Eldin, A.; Mattes, K. The effect of local muscle fatigue and foot strike pattern during barefoot running at different speeds. Dtsch. Z. Sport. 2019, 70, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuer, S.; Kiesewetter, P.; Milani, T.L.; Mitschke, C. The ‘Ride’ Feeling during Running under Field Conditions-Objectified with a Single Inertial Measurement Unit. Sensors 2021, 21, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.; Verbitsky, O.; Isakov, E. Fatigue-related loading imbalance on the shank in running: A possible factor in stress fractures. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 28, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, C.E.; Hawkins, J.L.; Aubol, K.G. Tibial Acceleration during Running Is Higher in Field Testing Than Indoor Testing. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Kiesewetter, P.; Milani, T.L.; Mitschke, C. An Investigation of Running Kinematics with Recovered Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction on a Treadmill and In-Field Using Inertial Measurement Units: A Preliminary Study. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruneau, M.M.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Morgan, K.D.; Moore, T.E.; Denegar, C.R.; Casa, D.J.; Devaney, L.L. Comparison of Step Rate and Tibial Acceleration During Treadmill and Real-world Running. JOSPT Open 2025, 3, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, C.E.; Foch, E.; Gonzales, J.M.; Petersen, D. Biomechanics associated with tibial stress fracture in runners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2023, 12, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L.; Gao, Z.; Wang, A.; Shim, V.; Fekete, G.; Gu, Y.; Fernandez, J. Rethinking running biomechanics: A critical review of ground reaction forces, tibial bone loading, and the role of wearable sensors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1377383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, L.M.; von Tscharner, V.; Fletcher, J.R.; Nigg, B.M. Quantification of the manifestations of fatigue during treadmill running. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2012, 12, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesewetter, P.; Bräuer, S.; Haase, R.; Nitzsche, N.; Mitschke, C.; Milani, T.L. Do Carbon-Plated Running Shoes with Different Characteristics Influence Physiological and Biomechanical Variables during a 10 km Treadmill Run? Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, C.; Heß, T.; Milani, T. Which Method Detects Foot Strike in Rearfoot and Forefoot Runners Accurately when Using an Inertial Measurement Unit? Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, A.M.; Martelloni, C.; Scapellato, S.; Cavallo, F. Assessment of walking features from foot inertial sensing. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 52, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, R.M. Energy-saving mechanisms in walking and running. J. Exp. Biol. 1991, 160, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, C.; Öhmichen, M.; Milani, T. A Single Gyroscope Can Be Used to Accurately Determine Peak Eversion Velocity during Locomotion at Different Speeds and in Various Shoes. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, C.; Zaumseil, F.; Milani, T.L. The influence of inertial sensor sampling frequency on the accuracy of measurement parameters in rearfoot running. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 20, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya-Cuartero, J.; Lopez-Arbues, B.; Jimenezolmedo, J.M.; Villalon-Gasch, L. Influence of Fatigue on the Modification of Biomechanical Parameters in Endurance Running: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2024, 17, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hreljac, A. Impact and overuse injuries in runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heß, T.; Milani, T.L.; Stoll, J.; Mitschke, C. Running and Jumping After Muscle Fatigue in Subjects with a History of Knee Injury: What Are the Acute Effects of Wearing a Knee Brace on Biomechanics? Bioengineering 2025, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breine, B.; Malcolm, P.; Galle, S.; Fiers, P.; Frederick, E.C.; de Clercq, D. Running speed-induced changes in foot contact pattern influence impact loading rate. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenfelder, J.; Sterzing, T.; Bullmann, M.; Milani, T.L. Heel strike angle and foot angular velocity in the sagittal plane during running in different shoe conditions. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2008, 1, O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, B.; Tucker, C.B.; Gallagher, L.; Parelkar, P.; Thomas, L.; Crespo, R.; Price, R.J. Grizzlies and gazelles: Duty factor is an effective measure for categorizing running style in English Premier League soccer players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 939676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, S.; Prigent, G.; Stöggl, T.; Martínez, A.; Snyder, C.; Gremeaux-Bader, V.; Aminian, K. Biomechanical Response of the Lower Extremity to Running-Induced Acute Fatigue: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 646042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, F.; Fadillioglu, C.; Stein, T. Fatigue-Related Changes in Spatiotemporal Parameters, Joint Kinematics and Leg Stiffness in Expert Runners During a Middle-Distance Run. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 634258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).