Abstract

The pacarana (Dinomys branickii) is a typical rodent of the Amazonian biome crepuscular habits, feeding on fruits, leaves, and roots. However, studies on these animals, inhabiting behaviors, and their parasites are limited. This study aimed to report the parasites found in fecal samples and a dead specimen of D. branickii in the Brazilian Cerrado. In 2023, fecal samples from five animals were collected and examined using flotation and simple sedimentation techniques for the identification of parasitic eggs. In 2025, a necropsy was performed on a decreased animal. Fecal samples of all animals were positive for eggs of Strongyloides spp., with two cases of co-infection with Oxyuroidea eggs and one with Trichuris sp. eggs. The Wellcomia branickii found during necropsy is a specific helminth of the pacaranas gastrointestinal tract. The natural geographical range of D. branickii is in the Western Amazon. Its introduction in the Cerrado, although for conservation purposes, reinforces the potential for this translocated species to disseminate non-native parasites outside its natural range.

1. Introduction

Dinomys branickii Peters, 1873, commonly known as pacarana, is a nocturnal rodent currently facing extinction. This species is the last extant member of the family Dinomyidae, originally found in South American countries such as Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil [1]. The only Brazilian state where pacarana is naturally reported is the state of Acre in the western Amazon biome [2]. This rodent is active at night or during twilight hours in nature. In captivity, these habits change due to human activities, making them active during the day [1]. Physically characterized as a large, robust, short-legged pacarana, it is at risk of extinction because of habitat limitations, low abundance, and phylogenetic singularity [3]. Dinomys branickii is a gregarious and exclusively herbivorous species, owing to a well-developed cecum that enables the digestion of fibrous plant material such as leaves, stems, roots, and fruits. This opportunistic habit controls excessive plant growth and promotes seed dispersal, which plays an important role in forest dynamics [4].

Studies on parasites of the pacarana are scarce and have been limited to animals in captivity [5,6], with a small number of described parasite species. The nematode Wellcomia branickii McLure, 1932, was described as a typical oxyurid of D. branickii [7]. A previous study conducted in Colombia, identified eggs of Strongyloides spp. by coproparasitological analysis [6]. There is a gap in the helminth fauna of Brazilian pacarana. The objective of this study was to describe the occurrence of parasitic forms in pacarana kept in captivity in a biome where they are considered exotic species.

2. Materials and Methods

Five specimens of D. branickii are currently maintained under human care at the Instituto Onça Pintada (Mineiros municipality, GO, Brazil; 17°54′00.5″ S and 53°00′21.7″ W), within the Brazilian Cerrado biome. These individuals, originating from the state of Acre, were part of an ex situ reproductive population established with the dual purpose of safeguarding the species and enabling research on its physiology, behavior, and reproduction. These are the only specimens of pacarana outside from the Amazon biome in Brazilian Cerrado.

The pacarana group, which is exotic in this region, was maintained in a medium enclosure with vegetation, semi-covered with tunnels, and isolated from other animals. Feeding consisted of seeds, as well as grasses and vegetation in the environment. In 2023, fecal samples were collected from each animal and sent for coproparasitological analysis. Samples were collected in the morning after observing natural defecation, without handling the animals. The feces were stored at 4 °C and subjected to flotation tests in a hypersaturated saline solution and sedimentation, according to [8].

In June 2025, one animal died and was necropsied. During necropsy, nematodes were found in the large intestine and mounted on temporary slides (with lugol) to examine internal structures, after that the parasite returned to the bottle with alcohol for storage [8]. The specimens were identified according to the literature [9,10,11]. This study was approved by the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Jataí (Protocol no. 011/2022) and SISBIO (License no. 54134-11).

3. Results

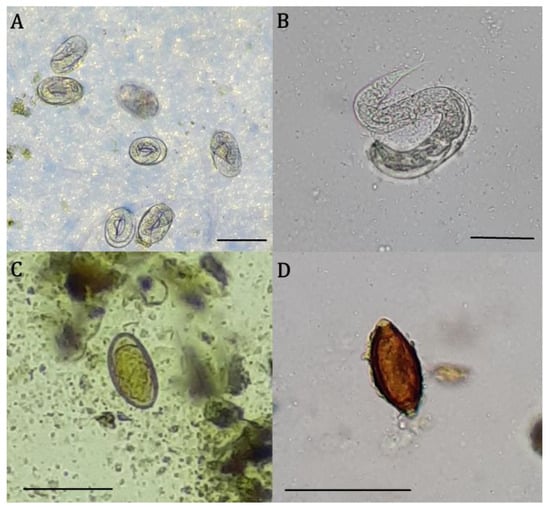

Fecal samples from five pacaranas tested positive for parasitic eggs. Samples showed parasitic forms: five were positive for Strongyloides spp. eggs, with two coinfections—one with Oxyuroidea eggs and another with Trichuris sp. eggs (parasitic forms are shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Parasitic forms found in feces of Dinomys branickii at the Instituto Onça Pintada, in the Brazilian Cerrado. (A) Larvated egg of Strongyloides sp. found in flotation test, Scale bar = 50 µm; (B) Rhabditiform larva of Strongyloides sp. found in sedimentation test, Scale bar = 30 µm; (C) Oxyuridea egg found in sedimentation test, Scale bar = 100 µm; (D) Trichuris sp. egg found in flotation test, Scale bar = 100 µm.

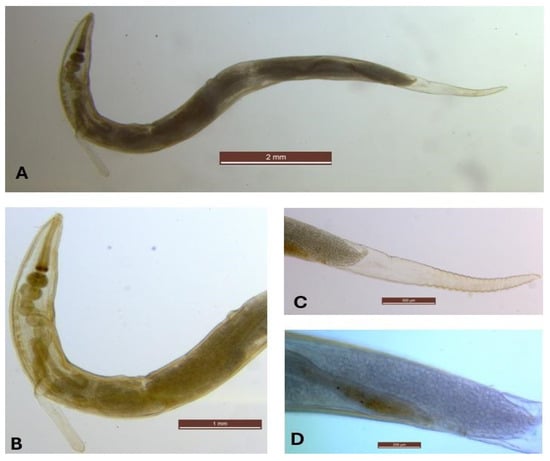

After the death, one pacarana was necropsied and inspected for parasites. The helminths were identified as W. branickii (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wellcomia branickii found during necropsy of Dinomys branickii at the Instituto Onça Pintada in the Brazilian Cerrado. (A) Female, total view, Scale bar = 2 mm; (B) Anterior, Scale bar = 1 mm and (C) Posterior end, Scale bar = 300 µm; (D) Uterus with eggs, Scale bar = 200 µm.

4. Discussion

The genus Strongyloides comprises numerous species infecting humans and a wide variety of animal hosts. Rodents, ruminants, domestic animals, and humans have been frequently described as hosts of Strongyloides species [12]. This parasite has previously been reported in D. branickii, primates, birds, and carnivores, all found in the same zoo [6]. In Brazil, species belonging to this genus have been reported in rodents [13]. The occurrence of this genus in the animals in this study may be associated with two hypotheses: parasitism originating from the native biome of species linked to Amazonian rodents, or adaptation of Strongyloides species found in the Cerrado biome. In either case, the introduction of exotic species, like pacarana, must be monitored as they can introduce new pathogens into the biome or even serve as new reservoirs for local species, expanding the distribution of these groups. Despite the presence of Strongyloides sp. in fecal samples in 2023 the parasite was not found during necropsy in 2025. The absence could be related to time and no adaptation to the environment. Enclosure conditions, cleaning and maintenance, could affect parasite survival and ability to maintain oneself [5].

The same was observed in Trichuris sp., a nematode frequently described in rodents. This is the first report of parasitism of D. branickii by this parasite. Trichuris sp. is a parasite which has been described as parasitizing Cuniculus paca [4] as well. This animal is from the western Amazon, the same region of origin as D. branickii in our study. However, many rodents can be parasitized by nematodes of this genus [12], including C. paca that is found in both Amazonian and Cerrado biomes. The proximity of life cycles and fiscal similarity between pacarana and paca and other rodents likely favor the adaptation of the parasite [1].

The family Oxyuridae is typically found in birds and mammals. One member of this family is W. branickii, which has been described in pacarana [5]. Initially, in 2023, we identified the presence of oxyurid eggs through stool examinations but were unable to identify them to the species level. The presence of an Oxyroidea without a species suggests two hypotheses: first: pacarana came to Cerrado already infected with this parasite from Amazon; second they become infected by an Oxyroidea present on Cerrado biome. However, when we identified adult individuals through necropsy in 2025, we were able to identify the oxyurid species involved. The discovery of animals positive for W. branickii a few years after their introduction into the Cerrado biome indicates that these animals carried the pathogen from the Amazon. The oxyurid nematode W. branickii despite being part of pacaranas helminfauna should not be able to maintain in Cerrado. Even under different biome conditions, this nematode maintained an active biological cycle, demonstrating its ability to adapt to a new biome. At this time, it is not possible to assess whether the presence of an exotic pathogen poses a risk to the local fauna; however, it is a possibility that should be monitored in future studies, especially with rodents such as capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), guinea pigs (Cavia sp.), agoutis (Dasyprocta sp.), and pacas (Cuniculus sp.), which share common ancestors with pacarana, and therefore may present related issues [14].

The pacarana is a rodent originating from the Amazon biome and the group created in captivity in the Brazilian cerrado is important for conservation. However, it may also pose a risk for native animals in the biome. Exotic individuals can be reservoirs of different parasites [15]. The present study highlights this by the presence of W. branickii; this species is only found in pacaranas. The presence of this helminth in a new biome makes it possible that another species can have contact with this parasite. The same happens to Trichuris sp. and Strongyloides spp., both species not typically found in D. branickii in nature. These discoveries show the importance and consequences of maintaining species outside their habitats.

5. Conclusions

The new record of parasites in D. branickii demonstrates the potential of this species to act as a reservoir. The introduction of animals from different regions or exotic species and their role as reservoirs has already been demonstrated in other cases, such as wild boars in the Brazilian Cerrado [15]. This study describes the occurrence of three nematodes in D. branickii: Strongyloides spp., Trichuris sp., and W. branickii, with the first report of Trichuris sp. in this host. This study reinforces the importance and impact of translocated species as reservoirs for parasites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.-S., R.M.P.M., Í.A.B., A.T.d.A.J., L.S., T.J.S. and D.G.d.S.R.; methodology, L.F.-S., A.P.C.G., M.L.M.M., M.M.d.M.B., R.M.P.M., M.C.C.d.S., M.A.B.d.P., S.R.C.-S. and D.G.d.S.R.; validation, R.M.P.M., L.d.S.Q., Í.A.B., A.T.d.A.J., L.S., T.J.S. and D.G.d.S.R.; formal analysis, L.F.-S., A.P.C.G. and D.G.d.S.R.; investigation, L.F.-S., A.P.C.G., M.L.M.M., M.M.d.M.B., R.M.P.M., M.C.C.d.S., M.A.B.d.P., S.R.C.-S., L.d.S.Q. and D.G.d.S.R.; resources, A.T.d.A.J., L.S., T.J.S. and D.G.d.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.-S., A.P.C.G., M.L.M.M., M.M.d.M.B., R.M.P.M., M.C.C.d.S., M.A.B.d.P., S.R.C.-S., L.d.S.Q. and Í.A.B.; writing—review and editing, L.F.-S., A.T.d.A.J., L.S., T.J.S. and D.G.d.S.R.; supervision D.G.d.S.R.; project administration and D.G.d.S.R.; funding acquisition, A.T.d.A.J., L.S., T.J.S. and D.G.d.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Goiás (FAPEG) grant number 202310267001408 and 202510267000577, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) scholarships to L.F.S. and A.P.C.G., and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico research grant to D.G.S.R.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work was submitted to the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals at the University of Jataí (CEUA), protocol number 011/22, 26 August 2022 and by the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) through the Biodiversity Authorization and Information System (SISBIO number 54134-11).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meritt, D.A. The Pacarana, Dinomys branickii. In One Medicine; Ryder, O.A., Byrd, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1984; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, E.F.; Casali, D.; Costa-Araújo, R.; Garbino, G.S.T.; Libardi, G.S.; Loretto, D.; Loss, A.C.; Marmontel, M.; Moras, L.M.; Nascimento, M.C.; et al. Lista de Mamíferos do Brasil. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Rodríguez, C.A.; Corrales-Escobar, J.D.; Giraldo-López, A. Confirmación de la presencia y nuevos registros del pacarana (Rodentia: Dinomyidae: Dinomys branickii) en Colombia. Mastozool. Neotrop 2014, 21, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.L.; Osbahr, K. Composición botánica y nutricional de la dieta de Dinomys branickii (Rodentia: Dinomyidae) en los Andes Centrales de Colombia. Rev. UDCA Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2013, 16, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbahr, K. Efecto de las condiciones de cautiverio sobre la presencia de Wellcomnia branickii, un nematodo específico del pacarana (Dinomys branickii) un estudio de caso. Rev. UDCA Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2003, 6, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, M.C.; Ramírez, G.F.; Osorio, J.H. Principales Helmintos encontrados en un Centro de fauna Cautiva en Colombia. Boletín Científico Cent. Mus. Mus. Hist. Nat. 2013, 17, 251–257. Available online: https://revistasojs.ucaldas.edu.co/index.php/boletincientifico/article/view/4535 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Tantaleán, M. Nuevos registros de nematodes parásitos de animales de vida silvestre new records of parasite nematodes from wildlife in Peru. Rev. Peru. Biol. 1998, 5, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoffmann, R.P. Diagnóstico de Parasitismo Veterinário; Sulina: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 1987. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Anderson, R.C.; Chabaud, A.G.; Willmott, S. Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Archival Volume; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2009; p. 463. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hugot, J.P. Sur le genre Wellcomia (Oxyuridae, Nematoda), parasite de Rongeurs archaïques. Bull. Mus. Hist. Nat. 1982, 4, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, G.W. Nematode parasites of mammals: With a description of a new species, Wellcomia branickii, from specimens collected in the New York Zoological Park, 1930. Zoologica 1932, 15, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.J.; Henrique, H.O.; Gomes, D.C.; Roberto, R.M. Nematóides do Brasil. Parte V: Nematóides de mamíferos. Rev. Bras. Zoo. 1997, 14, 1–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.O.; Leiner, N.O.; Ferrando, C.P.R.; Andrade-Silva, B.E.D.; Gentile, R.; Maldonado, A. First report of the intestinal helminth community in the broad-headed spiny-rat Clyomys laticeps (Rodentia, Echimyidae). Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2020, 29, e009420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, V.S.; Lobo, F.E.F.; Neto, A.G.d.S.; da Silva, M.I.A.; Virgilio, L.R.; Oliveira, M.N.; Nascimento, R.L.D.; Correa, M.J.; Pereira, F.B.; Ramos, D.G.d.S.; et al. Gastrointestinal nematodes in Cuniculus paca (Linnaeus, 1766) from hunting fauna in the Western Amazonian region. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2024, 53, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes-Silva, L.; Maia, G.O.; Alves-Ribeiro, B.S.; Assis-Silva, Z.M.; da Costa, G.E.S.; Alves, J.V.d.O.A.; Silva, V.L.d.B.; Zago, E.A.; Moraes, I.d.S.; Ferraz, H.T.; et al. Helminths of zoonotic importance in Tayassuidae and Suidae in Brazilian Midwest: Risks for human and domestic animal health. Parasitology 2025, 152, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).