Pathogen Surveillance of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks in Southern Pennsylvania, USA Using Targeted and Metatranscriptomic Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

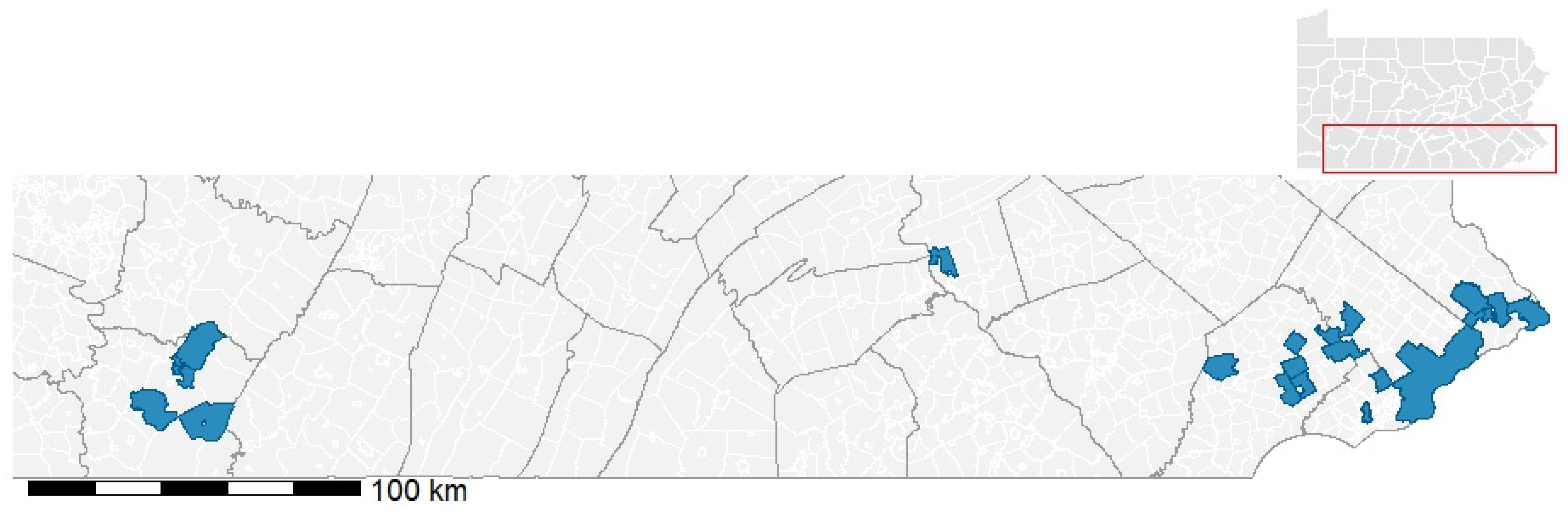

2.1. Ticks and Nucleic Acid

2.2. Metatranscriptomics with MinION MK1C

2.3. Targeted Pathogen Detection

2.4. Cytochrome b Gene PCR for Host Blood Meal Source Detection

3. Results

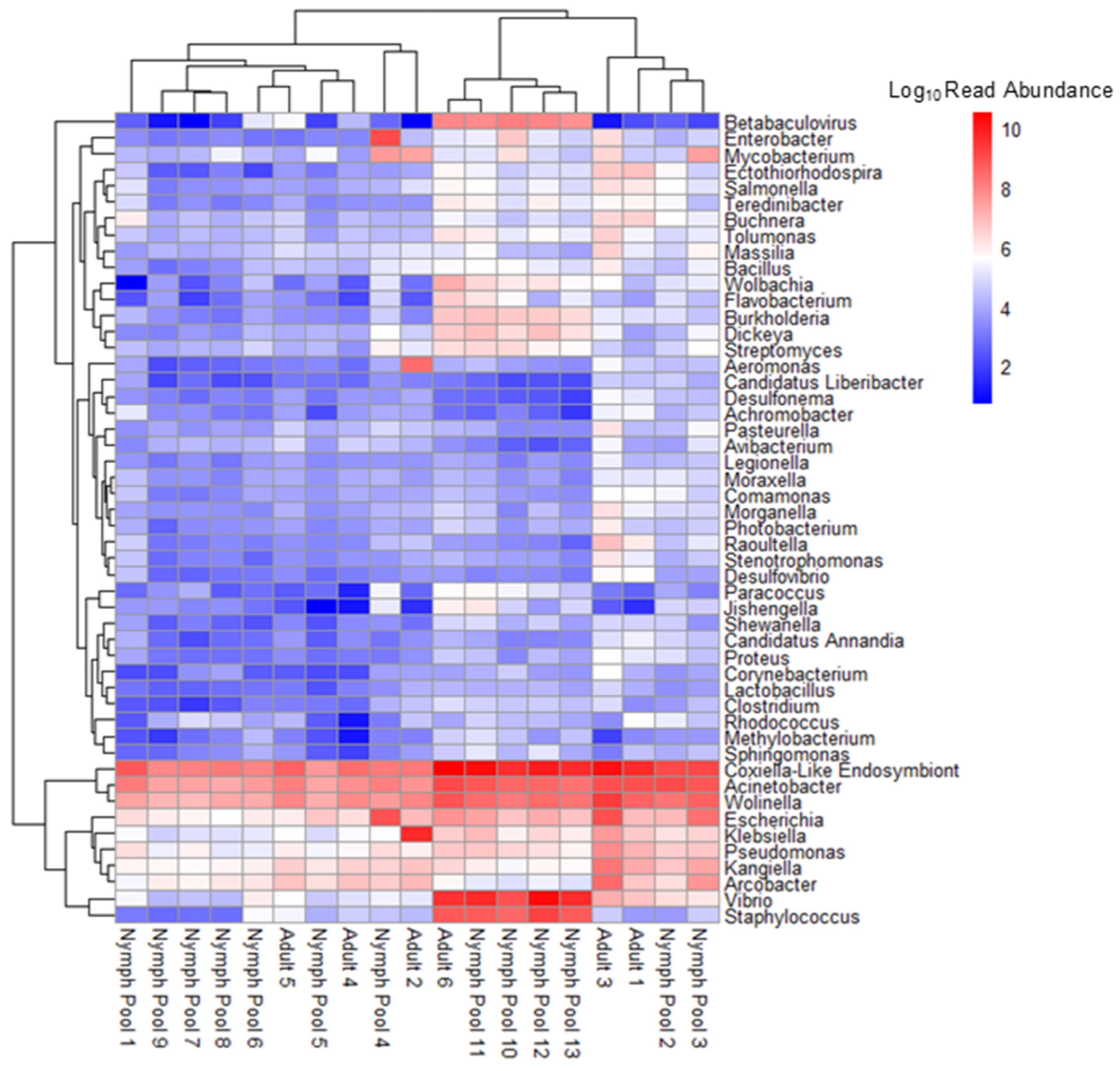

3.1. Metatranscriptomics with MinION MK1C

3.2. Targeted Pathogen Detection

3.3. Cytochrome b Gene PCR for Host Blood Meal Source Detection

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Egizi, A.; Bulaga-Seraphin, L.; Alt, E.; Bajwa, W.; Bernick, J.; Bickerton, M.; Campbell, S.; Connally, N.; Doi, K.; Falco, R.; et al. First Glimpse into the Origin and Spread of the Asian Longhorned Tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, in the United States. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, T.; Occi, J.L.; Robbins, R.G.; Egizi, A. Discovery of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) Parasitizing a Sheep in New Jersey, United States. J. Med. Entomol. 2018, 55, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-APHIS. Monitoring Haemaphysalis longicornis, the Asian Longhorned Tick, Populations in the United States. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/monitoring-h-longicornis-plan-final-january-2024.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Asian Longhorned Ticks (Haemaphysalis longicornis). Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/asian-longhorned#:~:text=Asian%20longhorned%20ticks%20(Haemaphysalis%20longicornis,impact%20both%20animals%20and%20people (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Price, K.J.; Witmier, B.J.; Egizi, A.; Kane, A.J.; Tantum, C.; Jordan, R.A.; Glorioso, A.G.; Hutchinson, M.L. Distribution and density of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) on public lands in Pennsylvania, United States. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkel, D.; Herndon, R.; Noh, S.; Lahmers, K.; Todd, S.; Ueti, M.; Scoles, G.; Mason, K.; Fry, L. A U.S. Isolate of Theileria orientalis, Ikeda Genotype, Is Transmitted to Cattle by the Invasive Asian Longhorned Tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, W.; Perry, J.; Hermance, M. Transovarial Transmission of Heartland Virus by Invasive Asian Longhorned Ticks under Laboratory Conditions. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.; Ford, S.; Snellgrove, A.; Hartzer, K.; Smith, E.; Krapiunaya, I.; Levin, M. The Ability of the Invasive Asian Longhorned Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) to Acquire and Transmit Rickettsia rickettsii (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae), the Agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, under Laboratory Conditions. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.; Aryes, B.; Maes, S.; Witmier, B.; Chapman, H.; Coder, B.; Boyer, C.; Eisen, R.; Nicholson, W. First Detection of Human Pathogenic Variant of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Field-Collected Haemaphysalis longicornis, Pennsylvania, USA. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; White, S.; Shaw, D.; Egizi, A.; Lahmers, K.; Ruder, M.; Yabsley, M. Theileria orientalis Ikeda in Host-Seeking Haemaphysalis longicornis in Virginia, USA. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, S.I.; Binetruy, F.; Hernández-Jarguín, A.M.; Duron, O. The Tick Microbiome: Why Non-Pathogenic Microorganisms Matter in Tick Biology and Pathogen Transmission. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, J.; Melgar, M.; Swei, A.; Delwart, E.; Lane, R.S.; Chiu, C.Y. Metagenomic-Based Surveillance of Pacific Coast Tick Dermacentor occidentalis Identifies Two Novel Bunyaviruses and an Emerging Human Rickettsial Pathogen. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, L.; Travanty, N.V.; Watson, D.W.; Seagle, S.W.; Boyce, R.M.; Reiskind, M.H. Microbiome of Invasive Tick Species Haemaphysalis longicornis in North Carolina, USA. Insects 2024, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, R.; Lipkin, W.I. Discovery and Surveillance of Tick-Borne Pathogens. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.T.; White, S.A.; Shaw, D.; Garrett, K.B.; Wyckoff, S.T.; Doub, E.E.; Ruder, M.G.; Yabsley, M.J. A Multi-Seasonal Study Investigating the Phenology, Host and Habitat Associations, and Pathogens of Haemaphysalis longicornis in Virginia, USA. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufts, D.M.; Goodman, L.B.; Benedict, M.C.; Davis, A.D.; VanAcker, M.C.; Diuk-Wasser, M. Association of the Invasive Haemaphysalis longicornis Tick with Vertebrate Hosts, Other Native Tick Vectors, and Tick-Borne Pathogens in New York City, USA. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.J.; Khalil, N.; Witmier, B.J.; Coder, B.L.; Boyer, C.N.; Foster, E.; Eisen, R.J.; Molaei, G. Evidence of Protozoan and Bacterial Infection, Co-Infection, and Partial Blood Feeding in the Invasive Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis in Pennsylvania. J. Parasitol. 2023, 109, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.J.; Witmier, B.J.; Eckert, R.A.; Boyer, C.N. Recovery of Partially Engorged Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) Ticks from Active Surveillance. J. Med. Entomol. 2022, 59, 1842–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.T.; Bak, J.M.; Hu, R.; Nicholson, M.C.; Kelly, C.; Mather, T.N. Determining the duration of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) attachment to tick-bite victims. J. Med. Entomol. 1995, 32, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, I.M.; Ramundo, M.S.; Coletti, T.M.; da Silva, C.A.M.; Valenca, I.N.; Candido, D.S.; Sales, F.C.S.; Manuli, E.R.; de Jesus, J.G.; de Paula, A.; et al. Rapid Viral Metagenomics Using SMART-9N Amplification and Nanopore Sequencing. Wellcome Open Res. 2023, 6, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Salzberg, S.L. Pavian: Interactive Analysis of Metagenomics Data for Microbiome Studies and Pathogen Identification. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livengood, J.; Hutchinson, M.L.; Thirumalapura, N.; Tewari, D. Detection of Babesia, Borrelia, Anaplasma, and Rickettsia spp. in Adult Black-Legged Ticks (Ixodes scapularis) from Pennsylvania, United States, with a Luminex Multiplex Bead Assay. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020, 20, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, V.J.; Todd, S.M.; Carbonello, A.A.; Michalak, P.; Lahmers, K.K. Coinfection of Cattle in Virginia with Theileria orientalis Ikeda Genotype and Anaplasma marginale. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2022, 34, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Lah, E.F.; Yaakop, S.; Ahamad, M.; Md Nor, S. Molecular Identification of Blood Meal Sources of Ticks (Acari, Ixodidae) Using Cytochrome b Gene as a Genetic Marker. Zookeys 2015, 478, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brenner, A.E.; Muñoz-Leal, S.; Sachan, M.; Labruna, M.B.; Raghavan, R. Coxiella burnetii and Related Tick Endosymbionts Evolved from Pathogenic Ancestors. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13, evab108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Li, S.S.; Chen, K.L.; Yang, C.; Zhou, X.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Zhang, Y.K. Growth Dynamics and Tissue Localization of a Coxiella-like Endosymbiont in the Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.L.; Qiu, Q.G.; Cheng, T.Y.; Liu, G.H.; Liu, L.; Duan, D.Y. Composition of the Midgut Microbiota Structure of Haemaphysalis longicornis Tick Parasitizing Tiger and Deer. Animals 2024, 14, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufts, D.M.; Sameroff, S.; Tagliafierro, T.; Jain, K.; Oleynik, A.; VanAcker, M.C.; Diuk-Wasser, M.A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Tokarz, R. A Metagenomic Examination of the Pathobiome of the Invasive Tick Species, Haemaphysalis longicornis, Collected from a New York City Borough, USA. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-APHIS. Bovine Theileriosis. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/bovine-theileriosis-infosheet.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- USDA-APHIS. Emerging Risk Notice: Theileria orientalis Ikeda. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/theileria-orientalis-ikeda-notice.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Tufts, D.M.; Goethert, H.K.; Diuk-Wasser, M.A. Host-pathogen associations inferred from bloodmeal analyses of Ixodes scapularis ticks in a low biodiversity setting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e00667-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Livengood, J.; Young, K.; Lint, C.; Thirumalapura, N.; Price, K.J.; Tewari, D. Pathogen Surveillance of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks in Southern Pennsylvania, USA Using Targeted and Metatranscriptomic Screening. Parasitologia 2025, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5040064

Livengood J, Young K, Lint C, Thirumalapura N, Price KJ, Tewari D. Pathogen Surveillance of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks in Southern Pennsylvania, USA Using Targeted and Metatranscriptomic Screening. Parasitologia. 2025; 5(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleLivengood, Julia, Kelsey Young, Candy Lint, Nagaraja Thirumalapura, Keith J. Price, and Deepanker Tewari. 2025. "Pathogen Surveillance of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks in Southern Pennsylvania, USA Using Targeted and Metatranscriptomic Screening" Parasitologia 5, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5040064

APA StyleLivengood, J., Young, K., Lint, C., Thirumalapura, N., Price, K. J., & Tewari, D. (2025). Pathogen Surveillance of Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks in Southern Pennsylvania, USA Using Targeted and Metatranscriptomic Screening. Parasitologia, 5(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5040064