Abstract

Background/Objectives: The recovery of latent fingerprints from submerged evidence remains a critical challenge in forensic science, as ridge details deteriorate rapidly once under water. This study aims to compare the effectiveness of three established fingerprint development techniques—cyanoacrylate fuming, small particle reagent (SPR), and powder dusting—on non-porous substrates (glass slides and stainless steel blades) immersed in different water types representative of Rajasthan’s Shekhawati region. The objective was to evaluate the influence of water composition and immersion duration on the quality and reproducibility of developed prints. Methods: Experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. Fingerprints were submerged in hard water, mineral water, and rainwater for durations of 10 min, 1 day, 5 days, and 10 days. Each condition was replicated three times. Developed fingerprints were assessed for ridge clarity using a five-point scoring scale, and the results were statistically analyzed using Chi-Square and correlation tests. Results: Cyanoacrylate fuming consistently produced the highest quality ridge detail across all submersion periods, particularly in mineral and rainwater environments. SPR exhibited moderate effectiveness, while powder dusting showed limited performance under all conditions. Statistical analysis indicated that fingerprint quality was significantly affected by water composition, substrate type, and immersion duration (p < 0.001). Conclusions: The study highlights that fingerprint recovery from submerged non-porous evidence depends strongly on water chemistry and exposure time. Cyanoacrylate fuming is confirmed as the most reliable method, while environmental variables such as ion content and water hardness play decisive roles in fingerprint preservation and visualization.

1. Introduction

As fingerprints are unique and, in most cases, permanent, fingerprints still top other biometrics as the most reliable form of biometric identification [1,2,3]. Latent fingerprints (i.e., an invisible deposit left by finger ridges on a surface) are an invaluable source of identifying evidence to criminal cases through forensic investigations. Latent fingerprints on an object are unsurpassed as a method for identification of suspects, but, as soon as they come into contact with an aquatic environment, the integrity and the quantifiable recoverability of these latent fingerprints are rapidly degraded, making them a challenge for the forensic analyst to utilize [4,5,6,7,8]. The persistence and quality of recoverable fingerprints on submerged evidence is a function of the composition of water, properties of the substrate surface, and the degree of submersion duration [9].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that exposure of the hands to water potentially compromises fingerprint quality in a number of ways, including dissolution of water-soluble components, mechanical washing effects, and biological degradation. Additionally, the chemical composition of different water types can either speed up or slow down the degradation processes, depending on factors such as mineral content, pH level, and number of microorganisms. The variability in such means varies, thus making it important to evaluate the procedures used for particular conditions of water [10,11,12].

Various development methodologies have exhibited varying degrees of effectiveness in recovering concealed latent fingerprints. Results demonstrate that cyanoacrylate fuming outperforms conventional wet chemical techniques in efficacy and its ability to produce a polymerized structure on non-porous surfaces, such as glass and metal, that were previously immersed [13,14,15,16]. In the presence of moisture and fingerprint residue, cyanoacrylate monomers polymerize, producing white ridges that can be enhanced with colors. The small particle reagent (SPR) functions effectively in aqueous conditions due to its adherence to stable lipid residues in water [14,17,18,19]. Molybdenum disulphide (MoS2) or activated carbon in SPR suspends and detaches from the lipid components of fingerprint residue, facilitating the visualization of ridge patterns on moist surfaces. Traditional powder dusting is generally utilized on dry surfaces; nevertheless, its efficacy decreases on prints subjected to water due to insufficient adherence to those prints [14,20,21]. Other common methods, like ninhydrin, iodine fuming, and silver nitrate techniques, demonstrate considerable deficiencies. In aquatic environments, porous surfaces are generally the exclusive substrates on which ninhydrin and silver nitrate exhibit effectiveness. Chemical methods are useless on non-porous substances, including glass or metal [22,23,24]. Furthermore, prints produced through iodine fuming are transient, making this technique inappropriate for moist surfaces [13]. This requires a particular system for managing evidence obtained from water.

This study selected three distinct water types to assess their impact on the degradation and recovery of latent fingerprints. These are as follows:

1.1. Hard Water from Rajasthan’s Shekhawati Region

It contains elevated levels of dissolved minerals, primarily calcium, magnesium, and fluoride [17,18]. This region was specifically chosen to test fingerprint deterioration in an environment with naturally elevated mineral content, reflecting certain forensic geographical contexts.

1.2. Commercial Mineral Water

A standardized comparison point used with regulated and constant composition. Commercial mineral water with a specified concentration of minerals facilitates the comparison of standardized mineral content to naturally occurring water sources, offering a controlled reference for inferring the effects of other ions on fingerprint preservation [19].

1.3. Rainwater

The selected samples provide a low-mineral environment with contrasting compositions, primarily influenced by atmospheric constituents and contaminants. Rainwater typically has a lower mineral content; however, it may also contain pollutants, influenced by geographical location and air quality [25].

The Shekhawati region of Rajasthan was specifically selected for this study due to its distinctive hydrochemical characteristics. The area is known for its high mineral content, elevated hardness levels, and the presence of dissolved ions such as calcium, magnesium, and fluoride, which vary considerably between groundwater, mineral water, and rainwater sources. These parameters influence the rate of chemical and physical degradation of fingerprint residues when submerged, making the region an ideal model for studying latent print recovery in mineral-rich aquatic environments. The inclusion of these regional factors adds ecological and forensic relevance to the comparative analysis.

The substrate material significantly influences the quality of fingerprint deposition and the efficacy of development techniques [20]. We selected non-porous surfaces, specifically stainless steel blades and glass slides, for the examination of surfaces encountered at crime scenes. Surface properties such as reflectivity, smoothness, and electrical conductivity yield distinct fingerprint residues and development reagents when subjected to different conditions.

Research has been conducted on the recovery of submerged fingerprints from contaminated water; however, there exists a significant gap in understanding the comparative effects of various water types on the quality of recovered fingerprints [24]. The studies did not include comparisons with controlled mineral water; however, it assessed latent print development following submersion in freshwater and seawater. Although degradation was less in freshwater, seawater also exhibited suboptimal performance [13,15,20]. A study assessed development methods, including SPR and cyanoacrylate fuming, on firearm surfaces retrieved from water. However, they did not conduct a systematic comparison of water types or recommend the most suitable method(s) for each surface type [21]. A study evaluates the effectiveness of the technique and the impact of water composition; however, their investigation into latent print development on submerged objects lacks depth in this area [26]. The researchers examined fingerprints on glass and metal surfaces retrieved from stagnant water, highlighting the importance of surface material; however, they did not conduct a systematic analysis of water types or submersion duration [24].

No previous studies have systematically compared the effects of hard water from the Shekhawati Region of Rajasthan, commercial mineral water, and rainwater on latent fingerprint development on various non-porous surfaces and development techniques. Therefore, this study aims to achieve the following:

- i.

- Evaluate the influence of different water compositions on the quality and recoverability of latent fingerprints on non-porous surfaces.

- ii.

- Three development techniques (powder dusting, activated charcoal-based SPR, and cyanoacrylate fuming) are assessed for their effectiveness under varying submersion conditions.

- iii.

- Identify optimal recovery protocols for each substrate type, water composition, and duration of submersion.

This research will systematically evaluate these variables to provide forensic investigators with evidence-based guidance for recovering and developing latent fingerprints from evidence submerged in various aquatic environments, thereby aiding in the recovery of critical identifying evidence in criminal investigations.

The novelty of this research lies in its region-specific comparative evaluation of fingerprint recovery across distinct water types characteristic of the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. By integrating hydrochemical variability with practical forensic assessment, this study contributes new insights into optimizing fingerprint development protocols for aquatic evidence.

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials and Equipment

2.1.1. Substrates

This study utilized two non-porous substrates: glass slides and stainless steel blades.

2.1.2. Development Materials

- Powder Method

Fluorescent fingerprint powder and application brush were used for this technique [22].

- Small Particle Reagent (SPR) Method

This method employed activated charcoal powder (specifications: chloride ≤ 0.20%, acid-soluble substances ≤ 3.50%, sulfate (SO4) ≤ 0.20%, loss on drying at 120 °C for 4 h < 15%), distilled water, and sodium lauryl sulfate (C12H25NaO4S, molecular weight: 288.38 g/mol, GRM 205-100G) as surfactant [15].

- Cyanoacrylate Fuming Method

Materials included superglue containing cyanoacrylate ester and solvents (alcohol, nitromethane, DMSO) and Borosil beakers (500 mL) with watch glass for creating fuming chambers [22,26].

During the development process, several potential interfering factors and precautionary measures were considered for each technique to ensure reliability of results. For cyanoacrylate fuming, excessive humidity or prolonged exposure time can lead to over-polymerization, resulting in background deposition and reduced ridge contrast; therefore, exposure duration was standardized at approximately five minutes and relative humidity was maintained within 60–70%. For the small particle reagent (SPR) method, variations in surfactant concentration or excessive mechanical agitation during immersion may cause partial ridge detachment or uneven particle deposition; hence, surfactant concentration and agitation intensity were carefully controlled. For the powder method, the presence of surface moisture or condensation can prevent proper adhesion of powder particles; therefore, all substrates were thoroughly air-dried before development. These precautions were consistently followed across all trials to minimize technique-induced variability and ensure reproducible results.

2.1.3. Additional Equipment

Additional equipment included measuring cylinders (100 mL), droppers (3 mL), plastic trays for substrate submersion (20.5 cm × 20.5 cm), precision weighing balance, hot plate, alcohol, permanent markers, gloves, magnifying glass, and ABFO scale for development and examination.

2.1.4. Water Samples

Three distinct water types were examined:

- Hard Water

From the Shekhawati Region of Rajasthan.

- Mineral Water

Bisleri bottled water containing Ca (1.0 mg), Mg (0.5 mg), K (0.1 mg) per 100 mL.

- Rainwater

2.1.5. Environmental Conditions

The study was conducted under controlled environmental conditions from August to September with an ambient temperature of 35 °C and relative humidity of 88%. Plastic trays were filled with one of the three water types for submersion experiments.

Rainwater was collected periodically during August–September from Sikar Road, Laxmangarh, Narodara Rural, Rajasthan. Hard water was sourced from Mody University of Science and Technology in the same region.

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Fingerprint Deposition

Non-porous surfaces (glass slides and stainless steel blades) were thoroughly cleaned with alcohol swabs prior to fingerprint deposition. Latent fingerprints were deposited in a natural state without introduction of stimuli (e.g., exercise-induced sweating) or post-collection enhancement. This approach was designed to mimic real-world conditions of fingerprint deposition during daily activities.

2.2.2. Submersion Protocol

The substrates with deposited fingerprints were submerged in separate trays containing hard water, mineral water, or rainwater for predetermined time intervals of 10 min, 1 day, 5 days, and 10 days. Control samples (without submersion) were developed using each technique for comparison. After each submersion period, substrates were air-dried for 30 min before applying development techniques under controlled conditions.

2.2.3. Development Techniques

- Powder Method

Fine fingerprint powder was carefully applied to the substrate surface using a soft brush with minimal pressure to ensure that powder adhered only to friction ridges and not the intervening furrows. Excess powder was gently removed without abrupt movements. Developed prints were examined under natural lighting against backgrounds that enhanced contrast.

- Small Particle Reagent (SPR) Method

For SPR development, suspensions were prepared containing 2 g of finely powdered activated charcoal in 15 mL of distilled water. A surfactant solution was created by dissolving 0.5 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 20 mL of distilled water. Six drops of this surfactant solution were added to the SPR suspension for each development.

Substrates were immersed in the SPR solution for 10 min to facilitate sufficient adsorption of latent print residues. After immersion, substrates were carefully removed and excess solution was rinsed off with tap water. Developed prints were photographed against a wall background to enhance ridge detail visibility.

- Cyanoacrylate Fuming Method

A borosilicate glass beaker served as the fuming chamber. A small amount of cyanoacrylate adhesive (superglue) was placed at the bottom of the beaker. The fingerprint-bearing substrate was suspended inside the beaker without contacting the adhesive. The beaker was gently heated on a hot plate, causing the cyanoacrylate to vaporize and release fumes into the chamber. Substrates were exposed to fumes for approximately 5 min to allow reaction with fingerprint residues. The developed prints were examined under natural light to evaluate quality.

2.2.4. Fingerprints Examination

Latent fingerprints that had been developed were analyzed and photographed. A high-resolution digital camera was used in a controlled setting to take all the fingerprint images to guarantee consistency in samples. To maximize the visibility of the ridges, it was decided to first take the images with varying exposure values. Although the implementation conditions of light and a series of photographic tests were applied, the ridge information acquired in the present research could not be taken at greater levels of clarity because of the natural deterioration of the fingerprints caused by a long exposure to water.

Image Processing and Enhancement Protocol: It is desired to make fingerprint images maximally interpretable and, at the same time, preserve forensic authenticity by processing them in a consistent manner:

- Initial Capture: All the images were scanned at a resolution of 600 dpi with a calibrated flatbed scanner with a constant lighting on (ambient temperature: 35 °C, relative humidity: 88%).

- Basic Normalization: The brightness and contrast were uniformly applied in all images using the standardized parameters (brightness + 10% contrast + 15%).

- Background Optimization: Future research will use high-quality image processing software (e.g., Adobe Photoshop with forensic plug-ins, ImageJ, or special fingerprint processing software, e.g., NIST Biometric Image Software) to reduce the effect of the background whilst maintaining genuine ridge features. In the current study, the background suppressions were intentionally restricted to prevent the artifacts that might cause distortion of the ridge morphology.

- No Artificial Enhancement: Other methods of digital enhancement (edge sharpening, sophisticated contrast control or ridges reconstruction algorithms) were tested, but these did not leave the ridge structure intact and produced artifacts and distortions. Since the maintenance of real ridges traits is a key factor in forensic interpretation, no artificial improvement other than equalization of brightness and contrast was used.

The pictures given are thus the exact state of the developed fingerprints as during laboratory analysis, so that the visual information is not modified.

- Assessment Protocol:

In order to reach experimental reproducibility and reduce the possibility of variability due to donors, all latent fingerprints were deposited by the same volunteer in controlled ambient conditions. All the experimental conditions were performed three times to ensure that development results were consistent. Two trained examiners were used in the assessment of the ridge clarity scores on the basis of the criteria mentioned in Table 1, and the average values were reported with standard deviations to demonstrate the consistency of the measurements. The inter-rater consensus was determined with the help of the Cohen kappa coefficient (k = 0.87, which means a strong agreement). This would help to ensure that the frequency of variation in quality of fingerprints was due to environment and methodological reasons and not due to variation in inter-donors or bias by examiners.

Table 1.

Criteria for fingerprint examination.

- Scoring System and Forensic Utility:

The scores were given to the prints developed using visual observation of the fingerprint on the basis of the clarity, visibility, and the overall quality of the fingerprint after it had been exposed to water (Table 1, Figure 1). It is worth mentioning that although the present study involved one of qualitative five-point scoring scales, this methodology was constructed to indicate a forensically useful system:

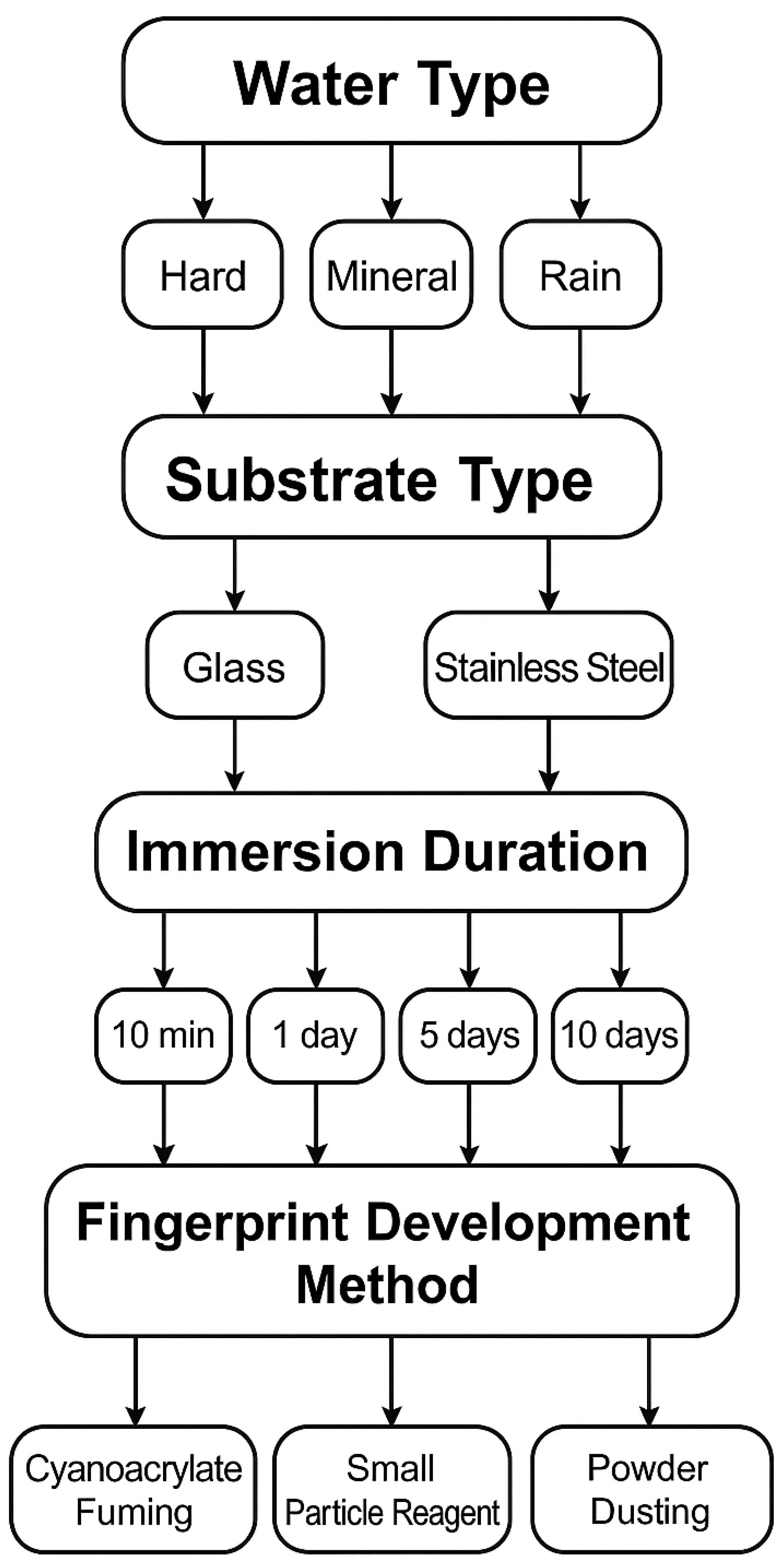

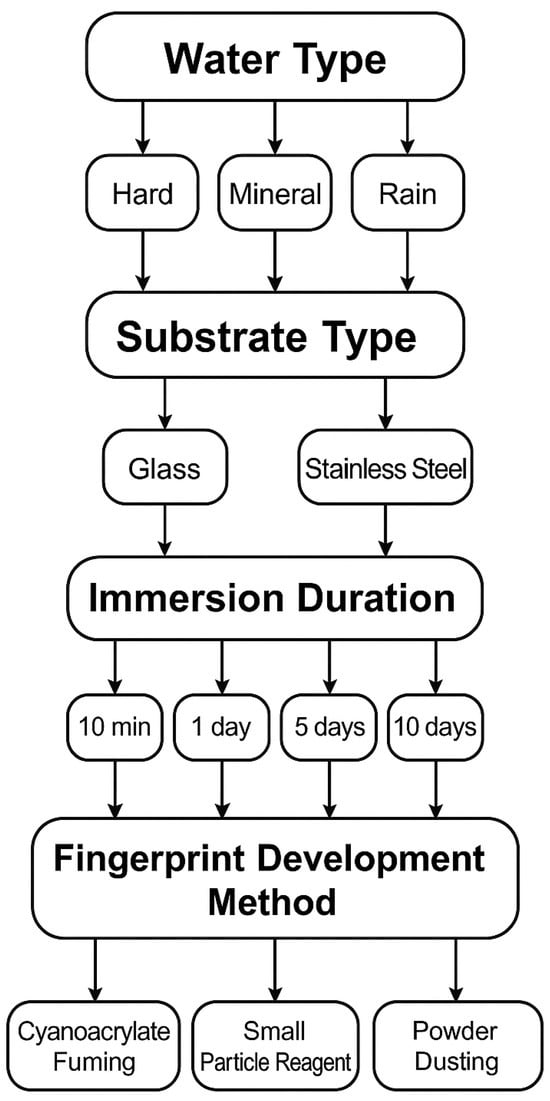

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental design showing relationships among water type (hard, mineral, rain), substrate type (glass, stainless steel), immersion duration (10 min, 1 day, 5 days, 10 days), and fingerprint development method (cyanoacrylate fuming, small particle reagent, and powder dusting).

- Scores 4–5 (Good to Excellent): Prints that can be compared and possibly identified, and have enough amount of ridge detail to elicit minutiae.

- Score 3 (Fair): Prints that have poor forensic value, and need to be improved or developed further.

- Scores 1–2 (Poor to Very Poor): Prints unsuitable for identification purposes

- Limitations and Future Improvements:

Although the five-point qualitative scoring scale offers a real-world evaluation of the utility of fingerprints in the field setting, we admit that quantitative objective measurement would contribute to the scientific accuracy of this review. Future research will include the following:

- Minutiae-Based Analysis: both Manual and Automated Counting of Type I (ridge endings) and Type II (bifurcations) minutiae by a group of independent examiners.

- Automated Quality Metrics: use of specialized software (e.g., NIST Biometric Image Software, VeriFinger SDK) for objective quality scores.

- Threshold Standards: usage of minimum number of minutiae to be used in positive identification in accordance with the Indian forensic guidelines and international guidelines (usually 12-point standard).

- Advanced Imaging: adoption of forensic light sources, fluorescent dyes after development, and special photography guidelines.

- Inter-Laboratory Validation: cooperation with forensic laboratories that have Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) to measure quality on the same basis.

3. Results and Discussion

The present study evaluated the effectiveness of three fingerprint development techniques—cyanoacrylate fuming, small particle reagent (SPR), and the powder method—in recovering latent fingerprints from substrates that were submerged in three different types of water: hard water, mineral water, and rainwater. Fingerprint quality was assessed over four time intervals (10 min, 1 day, 5 days, and 10 days) on both glass slides and stainless steel blades. The findings not only shed light on the comparative performance of these techniques under varying environmental conditions but also provide insights into the influence of substrate and water type on fingerprint degradation.

3.1. Fingerprint Recovery on Glass Slides

On glass slides, fingerprints submerged in mineral water demonstrated the highest initial quality. After 10 min, prints developed using both the cyanoacrylate fuming method and SPR method were rated as “excellent” with scores of 5, respectively, while prints produced by the powder method were considered “good” with a score of around 4. However, as the submersion time increased, the quality of prints declined markedly. At the 1-day interval, prints became “good” to “fair” and by days 5 and 10, the ridge details were either blurred or entirely lost, with mean scores dropping to between 1 and 2 (Table 2 and Table 3). In rainwater, although initial prints were classified as “good” across all three techniques, the SPR method demonstrated a slightly better performance compared to cyanoacrylate fuming and prints also followed a similar pattern of quality deterioration over time (Table 4 and Table 5). However, the quality of prints was good to very poor when submerged in hard water. Cyanoacrylate produced better prints as compared to SPR and the powder method over a prolonged period of time (Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 2.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on glass slides submerged in mineral water using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 3.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in Mineral Water on glass slide.

Table 4.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on glass slides submerged in rainwater using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 5.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in rainwater on a glass slide.

Table 6.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on glass slides submerged in hard water using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 7.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in Hard Water on a glass slide.

3.2. Analysis of Fingerprint Recovery on Stainless Steel Blades

When examining stainless steel blades, the results diverged somewhat from those on glass slides. In hard water, the quality of the developed prints was rated as “good” after 10 min and one day, although slight smearing was observed. By day 5, prints were downgraded to “fair” and, after 10 days, prints were no longer discernible (Table 8 and Table 9). On stainless steel surfaces submerged in mineral water, the fingerprints initially exhibited good quality with clear ridge detail; however, the presence of rust—an effect of the corrosion process—became evident by day 5, eventually leading to the absence of visible prints by day 10 (Table 10 and Table 11). Similarly, for samples immersed in rainwater, early impressions were only of “fair” quality with some ridge details evident. Yet, as time progressed, the clarity diminished significantly, with most prints classified as “poor” or “very poor” after extended submersion (Table 12 and Table 13).

Table 8.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on stainless steel blades submerged in hard water using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 9.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in Hard Water on stainless steel blades.

Table 10.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on stainless steel blades submerged in mineral water using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 11.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in Mineral Water on a stainless steel razor.

Table 12.

Scores and quality of fingerprints developed on stainless steel blades submerged in rainwater using cyanoacrylate fuming method, SPR method, and powder method.

Table 13.

A Timeline-Based Comparison of Cyanoacrylate Fuming, SPR, and Powder Method Using Glass Slides after Submersion of Samples in rainwater on a stainless steel razor.

Each experimental condition was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility of results, with one latent fingerprint deposited per substrate per trial. This produced triplicate data for every combination of water type, immersion duration, and development method. Statistical analysis was carried out on mean ridge clarity scores obtained from these replicates, and the corresponding standard deviation (SD) values were calculated to represent variability within each set. The SD values are reported in the relevant tables to indicate the precision and reliability of the results.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Chi-Square analyses were performed to evaluate the significance of the relationship between the variables: time duration, water type, fingerprint development technique, and quality scores. Case processing summaries indicate that all datasets used in the experiment had no missing values and were complete (Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16). Table 14 shows that all 75 cases for the interaction between time duration and quality of prints were valid. Similarly, Table 15 confirms that all 73 cases involving time duration, quality of prints, and water type were complete. Table 16 also reports full data availability for all 22 cases concerning water type, mean quality scores, and techniques used. This ensures the reliability and validity of the statistical analyses conducted. A crosstabulation of time duration and fingerprint quality shows a clear decrease in print quality over time (Table 17). High quality prints were mostly observed at 10 min and 1 day and the quality of prints declined by day 5 and day 10. An even distribution of samples across time intervals in Table 18 confirms the balanced comparison. The Chi-Square test for the relationship between time duration and quality of prints yielded a Pearson Chi-Square value of 55.556 (df = 12, p < 0.001) and a similar likelihood ratio (χ2 = 63.836, df = 12, p < 0.001), indicating that the observed differences in print quality over time were highly statistically significant (Figure 2). A separate Chi-Square analysis comparing the effect of water type, quality of prints, and time duration revealed significant correlations (p = 0.000 across tests) with a high linear-by-linear association, further confirming that the type of water in which the prints were submerged had a major impact on the quality retention of the fingerprints (Table 19). A three-way crosstabulation showed that fingerprint quality deteriorates and becoming poor and very poor with time across all water types was increasingly common after 5 and 10 days (Table 20). There was a sharp decline in the quality of fingerprints when submerged in hard water and mineral water compared to rainwater, where fair and good prints were slightly more preserved in earlier durations. Crosstabulation between water type, fingerprint development techniques, and mean quality scores showed that high mean scores were observed when cyanoacrylate and SPR methods were used in mineral and rainwater, while powder techniques mostly resulted in medium or low scores (Table 21). Hard water generally showed lower quality outcomes across all techniques, highlighting its adverse effect on fingerprint development. The Chi-Square test when comparing the different development techniques and their overall mean quality scores showed significant relationships (p = 0.004 for Pearson and p = 0.001 for the likelihood ratio), thereby establishing that the choice of technique critically influences the recovery of latent prints (Table 22). Statistical analysis was performed to quantify the variability in fingerprint quality scores across repeated trials. For each experimental condition, mean ridge clarity scores were calculated based on three independent replicates. The corresponding standard deviation (SD) values were computed and included in Table 4, Table 6, Table 8, Table 10, Table 12, Table 14, Table 17, Table 18, Table 20 and Table 21 to indicate statistical dispersion and reproducibility. These values provide a measure of consistency among repeated trials and allow comparison of technique reliability under different water types and immersion durations.

Table 14.

Summary of cases for the analysis of time duration and fingerprint quality.

Table 15.

Summary of cases for the three-way analysis of time duration, fingerprint quality, and water type.

Table 16.

Summary of cases for the analysis of water type, mean fingerprint quality, and development techniques.

Table 17.

Time duration × Quality of print Crosstabulation.

Table 18.

Time duration × Quality of print Crosstabulation.

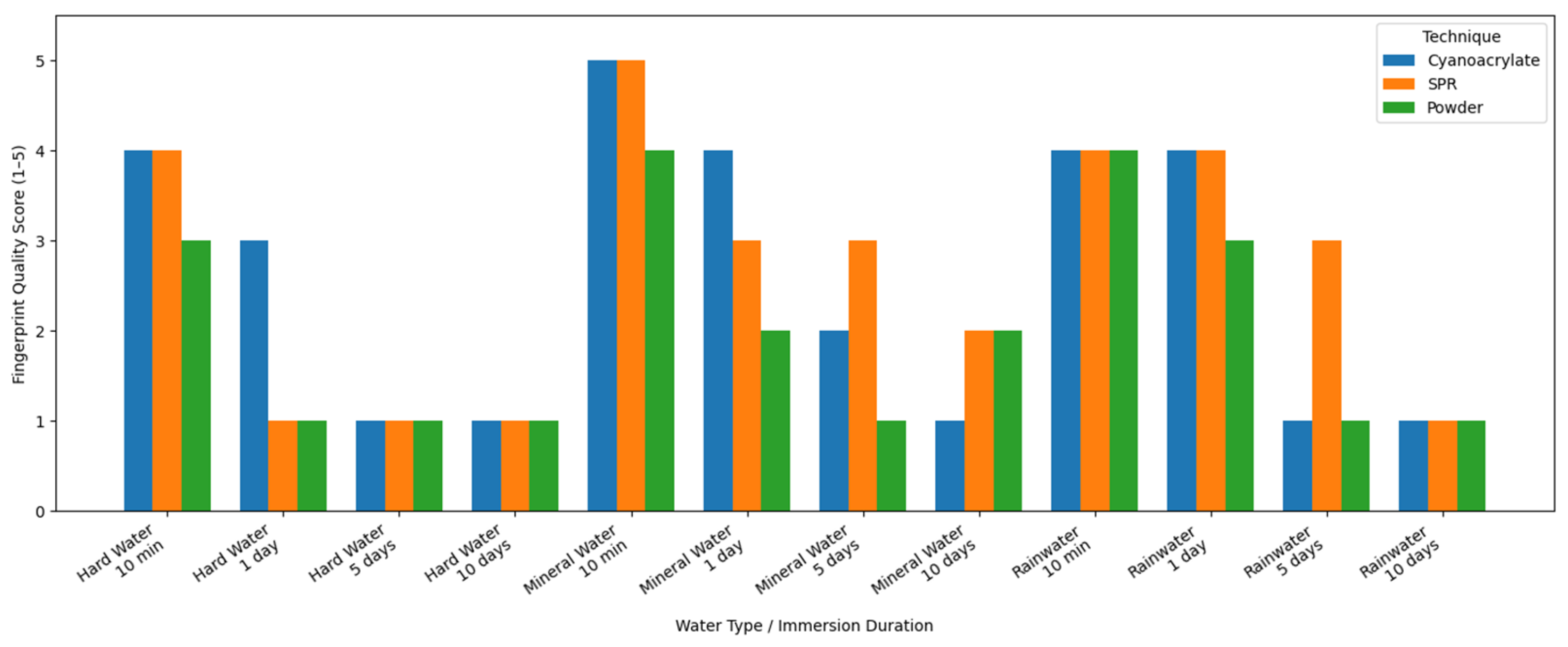

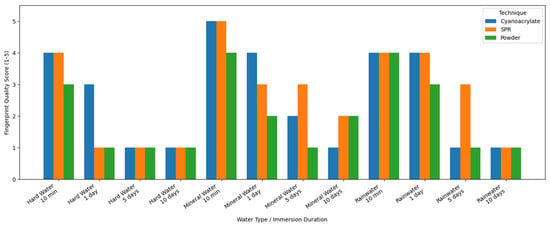

Figure 2.

Comparative fingerprint quality scores (1–5) for three development techniques—cyanoacrylate, small particle reagent (SPR), and powder—across different water types (Hard water, Mineral water, and Rainwater) and immersion durations (10 min, 1 day, 5 days, and 10 days). The clustered bar chart shows that cyanoacrylate consistently yields superior ridge clarity, with gradual degradation observed over time across all water types.

Table 19.

Chi-Square tests evaluating the association between water type, time duration, and fingerprint quality.

Table 20.

Time duration × Quality of prints × Water type Crosstabulation.

Table 21.

Water type × mean × Techniques used Crosstabulation.

Table 22.

Chi-Square test for the association between fingerprint development techniques and mean quality scores.

4. Discussion

The current research assessed the capability of three fingerprint development methods, including cyanoacrylate fuming, small particle reagent (SPR), and the powder method, to detect latent fingerprints on substrates immersed in three types of water: hard water, mineral water, and rainwater. The quality of a fingerprint was evaluated at four time intervals (10 min, 1 day, 5 days, and 10 days) on a glass slide and stainless steel blades. These results helped to not only illuminate the relative performance of these methods in different environmental conditions but also give information on the effect of substrate type and water type on fingerprint degradation [13,15,20,27].

4.1. Glass Slides Fingerprint Recovery

In contrast, the prints produced by the powder method are generally of lower quality [15]. The lower scores associated with the powder method might be due to its inherent limitations when dealing with water-damaged or aged fingerprints. Previous literature has also noted that the powder method is less effective on substrates that have undergone chemical or physical changes as a result of prolonged exposure to water [24].

The SPR method, although it performed well initially on certain substrates, did not consistently yield better results than cyanoacrylate fuming. This discrepancy might be due to differences in the substrate material or the chemical composition of the SPR (which is often charcoal-based) compared to cyanoacrylate ester fuming. Some earlier studies suggested that SPR might outperform cyanoacrylate fuming under specific conditions; however, our findings indicate that, on the substrates and water conditions tested, cyanoacrylate fuming remained superior [21].

Water type emerged as a critical factor affecting fingerprint quality [20,28]. Mineral water, which typically has lower levels of dissolved contaminants, allowed for the development of clearer and more distinct prints compared to hard water [19,29]. Hard water, enriched with higher concentrations of calcium, fluoride, and magnesium, appears to interact adversely with the fingerprint residue, leading to more rapid degradation [30]. This effect is consistent with previous studies that have identified high salinity and mineral content as detrimental to the preservation of latent prints [15]. Rainwater, which may have variable contaminant levels, produced intermediate results—with initial impressions being comparable to those in mineral water but deteriorating quickly as submersion time increased.

The time of submersion is another key variable. Across all water types and development techniques, the clarity and quality of fingerprint ridges decreased as the duration of submersion increased. This trend underscores the dynamic nature of fingerprint residue, which is prone to chemical, biological, and physical changes over time [31,32]. Even under optimal conditions, the protective elements of the fingerprint composition deteriorate gradually, resulting in less defined ridge details [33]. The significant decline in print quality observed at 5 and 10 days of submersion supports the inverse relationship between time and fingerprint clarity, as reported in prior research [16,20,26].

Furthermore, the substrate material also plays an important role in fingerprint recovery [20,34]. The results indicate that glass slides generally yield better quality prints compared to stainless steel blades. This difference is likely due to the smooth, non-reactive nature of glass which allows for better adhesion and less interference with the fingerprint residue.

4.2. Fingerprint Recovery on Stainless Steel Blades

Stainless steel, on the other hand, is susceptible to corrosion, especially when exposed to water over extended periods. The formation of rust and other corrosion products can obscure the ridge details, making it difficult to recover usable fingerprints. This finding is in line with previous studies that have demonstrated the challenges of developing fingerprints on metallic surfaces [35,36,37].

4.3. Statistical Analysis Using Chi-Square

The statistical analyses add further weight to these observations. The highly significant Chi-Square values indicate that the effects of time duration, water type, and development technique on fingerprint quality are robust and not attributable to random variation. The strong linear-by-linear associations observed in the analysis suggest that as the detrimental effects of water exposure increase, the quality of the prints declines in a predictable manner.

4.4. Methodological Considerations and Quality Assessment

- Image Quality and Visual Documentation Limitations:

We admit that the fingerprint images as provided in this study have drawbacks in terms of resolution and clarity as pointed out by reviewers. This is inherent to the nature of degraded fingerprints that are found in water as opposed to a shortcoming in photographic technique. The loss of the ridges when subjected to extended water exposure is a real forensic problem and our photographs can be used to show the true observation of the recovered prints as it would be seen by crime scene investigators. Images were scanned at the highest resolution possible (600 dpi) in a controlled lighting setup with the brightness and contrast levels being matched. We also intentionally did not use techniques of aggressive digital enhancement (edge sharpening, advanced filtering, ridge reconstruction algorithms) that might create artifacts or give the false impression of the actual quality of recovered prints. This is a more conservative method by which the presented visual evidence is forensic and does not falsely reflect the abilities and constraints of any development method within the conditions that were tested.

Future Enhancement of Visual Documentation: to improve image acquisition and processing, we suggest and intend to make the following changes to the future work, which include the following:

- State of the Imaging: forensic light sources (alternate light sources, UV light) and high-resolution digital microscopy.

- Fluorescent Enhancement: fluorescent dyes (e.g., Rhodamine 6G, Basic Yellow 40) should be applied after cyanoacrylate treatment in order to increase contrast to facilitate photography.

- Specialized Software: it is necessary to implement a background suppressing software (Adobe Photoshop with forensics plug-ins, ImageJ with Ridge detection algorithms, or commercial fingerprint analysis packages) that will be able to suppress backgrounds without removing ridges.

- Standardized Procedures: implementation of SWGFAST (Scientific Working Group on Friction Ridge Analysis, Study and Technology) principles of fingerprint photography and documentation.

- Multi-Modality: white light, oblique lighting, and reflected ultraviolet imaging (RUVIS) are used to produce a comprehensive documentation.

Such improvements would make the results much easier to interpret and, at the same time, preserve the integrity of forensic evidence.

- Objective Quality Metrics and Quantitative Analysis:

One of the major weaknesses of the present research is that instead of quantitative measures, qualitative scoring was used and on a five-point scale that is subjective. Although this scoring system was intended to portray a sensible forensic utility of the system (where a Score of 4–5 was regarded as useful prints; that is one that would allow the identification of the suspect), we acknowledge the fact that a quantitative analysis that would be based on minutiae was supposed to be more powerful and more scientifically sound.

- Proposed Quantitative Metrics for Future Studies:

- 1.

- Minutiae Count Analysis:

- ○

- Counting of Type I (ridge endings) and Type II (ridge bifurcations) minutiae manually by various independent examiners.

- ○

- Setting of a threshold value according to the minimum requirements of identification (12 points standard in most jurisdictions, although, again, this differs across countries).

- ○

- Comparison with other jurisdictional standards like the ones prescribed by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) of India.

- 2.

- Ridge Flow Continuity Index:

- ○

- Measures of ridge flow interruptions per unit area quantitatively.

- ○

- Ridge width and clarity measurement.

- 3.

- Automated Quality Scores:

- ○

- Application of NIST Fingerprint Image Quality (NFIQ) algorithm.

- ○

- Commercial AFIS quality metrics (e.g., match scores, quality flags) are used.

- ○

- The use of ISO/IEC 29794-1 standards of biometric sample quality [38].

- 4.

- Inter-Examiner Reliability:

- ○

- Statistical confirmation based on the kappa coefficient of Cohen when it comes to categorical measurements.

- ○

- Coefficients of intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) on continuous measures.

- ○

- Random duplicate analysis of test–retest reliability.

- Justification for Current Methodology:

The qualitative method used in the paper is based on more practical limitations in standard regional forensic laboratories in India and other developing environments:

- Equipment Availability: AFIS or software to detect minutiae are not available to many forensic laboratories in rural and semi-urban locations.

- Extreme Degradation: a significant number of samples in this experiment (especially at 5- and 10-day immersion times) showed such intense degradation that they could not be reliably counted using the manual method even at a minutiae level.

- Practical Relevance: the scoring system is also directly proportional to the decision-making of field investigators: is this print useful to be analyzed further or not?

Nevertheless, we admit that the inclusion of objective measures in the subsequent research will deepen the scientific validity of findings and allow us to compare it more accurately with the international research.

- Establishment of Threshold Standards:

Subsequent versions of this study will determine the partnership perimeters:

- Minimum Minutiae Count: prints must contain ≥12 clearly identifiable minutiae points for potential identification (adjustable based on jurisdictional requirements).

- Ridge Clarity Index: development of a quantitative metric assessing ridge edge sharpness and contrast using image analysis software.

- Comparison Standards: review of qualitative scores with quantitative measures in order to authenticate the scoring system employed in the study.

Such improvements will help in comparing them with international standards and make more conclusive arguments on the forensic usefulness of recovered prints.

4.5. Environmental and Chemical Factors

- Temperature and pH Considerations:

Besides water chemical composition, other environmental forces like temperature and pH are also significant in the preservation and degradation of latent fingerprints that were submerged in water. Temperature changes can speed up the rate of diffusion and dissolution of organic particles in fingerprint impressions, whereas changes in pH may change the ionization and chemical stability of fatty acids, amino acids, and sebaceous materials used in forming ridge patterns. Even though temperature and pH have not been regulated separately in the current study, the differences present between the types of water indirectly indicate the effect due to their impact on the mineral composition and ionic equilibrium.

Systematic variation in the ambient temperature during experiments (35 °C) and relative humidity (88%) was not explicitly varied and instead maintained and measured. The following studies will be conducted in order to quantify the effects of these parameters in combination and establish optimal recovery protocols in various environmental conditions. Experiments with dietary manipulation of temperature (range: 10–40 °C) and pH (range: 4–9), independently, would be informative on the exact processes of fingerprint degradation.

- Ion–Residue Interactions:

The stability of latent fingerprint residues in hard water is strongly affected by the interaction of multivalent cations and multivalent anions. Ions including Ca2+, Mg2+, and F can change the composition of the residues in such a way as by ionic bridging, saponification of lipids, and swelling of the residues, which eventually result in the decline in the ridge clearness. Hard water has a mineralization degree which facilitates such ionic exchanges and thus leads to even more pronounced degradation than the degradation caused by rainwater or mineral water.

- Mechanisms of Degradation:

In particular, insoluble saponification reactions of fatty acids in a fingerprint residue between calcium ions and fatty acids break the lipid matrix, which supports the adhesion of SPR. Magnesium ions could interfere with sites of cyanoacrylate polymerization by competing with amino acid functional groups. The presence of fluoride ions, especially in groundwater of the Shekhawati region, has the potential to break the hydrogen bonding of networks and encourages hydrolysis of the ester bonds within sebaceous components.

The knowledge of such ion–residue interactions will have a beneficial impact on the understanding of how fingerprints are destroyed in the water. The implications of these findings, in forensic terms, are that the submerged evidence should be recovered and preserved as quickly as possible and that underwater or drowning crime scenes should be investigated with a focus on the exposure time and the water chemistry in the area, as this may have a significant influence on recoverability of the fingerprints.

- Practical Forensic Implications:

To forensic practitioners, the findings indicate the following:

- Rapid Evidence Collection: evidence that is submerged in hard water must be given priority to recover and process it immediately.

- Water Sampling: sampling of water at crime scenes can be used to analyze the water samples chemically and can assist in predicting the probability of fingerprint preservation.

- Method Selection: cyanoacrylate fuming should be the initial technique of development in situations where submersion is of hard water.

- Chain of Custody: detailed documentation of water exposure conditions should be included in evidence documentation

4.6. Study Limitations and Methodological Constraints

Despite the fact that the current research study offers practicality in terms of recovering latent fingerprints on submerged non-porous surfaces, there are a number of limitations which need to be considered to help put the results into perspective and to lead the way forward in conducting future studies.

- Experimental Design Limitations:

- 1.

- Controlled Laboratory Conditions: the experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions (constant temperature: 35 °C, relative humidity: 88%), which may not fully replicate the complexity of natural aquatic environments. Real-world crime scenes involve additional variables such as the following:

- ○

- Water current and turbulence

- ○

- Sediment and particulate contamination

- ○

- Sunlight exposure and UV degradation

- ○

- Diurnal temperature fluctuations

- ○

- Presence of aquatic vegetation

- 2.

- Biological and Microbiological Factors: There was no independent analysis of factors like biofilm formation, colonization, and microbial activity that might also have a further effect on residue degradation. Fingerprint residues contain organic constituents that microorganisms can process in order to degrade them faster than in the case with chemical factors only.

- 3.

- Single Donor Limitation: The fingerprints were taken on one volunteer to minimize inter-individual differences in the composition of the residues. Although this method provides consistency to compare with the previous analysis, it restricts the extrapolation to a spectrum of fingerprint patterns. Future research is required to include the following:

- ○

- Various donors of different sebaceous glands activity.

- ○

- Various ages (juvenile and adult prints).

- ○

- Male and female donors to determine the hormonal effects on the residue composition.

Limited Substrate Variety: Glass and stainless steel are the most frequent examples of non-porous surfaces found at the crime scenes, but the other substrates should be investigated:

- ○

- Plastic materials (polyethylene, polypropylene, PVC).

- ○

- Surfaces made of ceramics and porcelain.

- ○

- Painted or coated metals.

- ○

- Laminated surfaces.

- 4.

- Fixed Time Intervals: the time intervals that were chosen (10 min, 1 day, 5 days, 10 days) might not fully show the degradation kinetics. Sampling more often (e.g., every hour during the first 24 h) may indicate some critical transition points.

- Assessment and Documentation Limitations:

- Subjective Scoring System: The five-point qualitative scoring system is practical and representative of forensic utility, although it is not as quantitative as minutiae-based analysis or automated quality measures. This restriction has been discussed in detail in Section 4.4.

- Image Quality Constraints: As it has been admitted, the process of visual recording of poor fingerprints is quite difficult by nature. The clarity and resolution of the images provided indicate real-life circumstances of forensic conditions, as opposed to a lack of photons; however, it can be observed that further research would be improved by the use of more sophisticated imaging modalities.

- Limited Development Technique Variations: There are many variations in each technique (cyanoacrylate, SPR, powder) (e.g., different powder compositions, SPR surfactant concentration, cyanoacrylate exposure time). This experiment used conventional procedures without a systematic investigation of the optimization of individual method.

- Environmental Control Limitations:

- Temperature and pH: These factors were not manipulated separately to determine their respective effect on degradation as they were monitored.

- Water Chemistry Complexity: There are hundreds of dissolved compounds in the natural water sources. Major ions, which were the subject of the study, were Ca2+, Mg2+, and F−, but the remaining were not analyzed:

- ○

- Trace metals

- ○

- Organic pollutants

- ○

- Dissolved oxygen levels

- ○

- Potential of oxidation–reduction

- ○

- Total dissolved solids (TDS)

- Statistical and Analytical Limitations:

- Sample Size: Although all conditions were repeated thrice, the sample sizes could be larger, which would enhance the statistical power and allow identification of the nuanced effects.

- Statistical Tests: Chi-Square tests suit categorical data but fail to give the scale of effects. Future research is required to include the following:

- ○

- Continuous variables analysis of variance (ANOVA).

- ○

- Multiple variables regression to predict quality scores.

- ○

- Survival analysis in order to model the kinetics of degradation.

- Generalizability Considerations:

Despite all these issues, the pattern of performance was similar in all the replicates, which highlights the trustworthiness of cyanoacrylate fuming as a sound method of evidence salvage in the local environment of the Shekhawati region. The results give useful background data to the forensic practitioner in a similar geographical and hydrochemical setting, though it is expected that the findings might not translate directly to many different aquatic habitats (e.g., marine water, industrial effluents, brackish water).

- Reproducibility and Validation:

All the experimental protocols, scoring criteria, and raw data are accessible on request to improve the reproducibility. Replication of this study in other laboratories and geographic areas would be an independent replication and, thus, there would be confidence in the results and the context-specific differences in the effectiveness of technique.

5. Conclusions

Overall, as it can be seen, the study reveals that the most effective method of developing latent fingerprints on substances that have been subjected to water is the cyanoacrylate fuming technique, which is superior to both the SPR and powder technique under the circumstances tested. The nature of water, the period of submersion, and the material used are known to have a great bearing on the quality of fingerprint development. Hard water and extended exposure destroy fingerprint details, thus making mineral water a relatively favorable environment in preserving the details. Moreover, non-porous and non-corrosive surfaces, such as glass slides, provide better results as compared to reactive surfaces such as stainless steel. This finding is not only useful in the body of knowledge in forensic science but also a practical finding for the crime scene investigators who are trying to maximize fingerprint recovery in harsh environmental conditions.

On the whole, the combination of the effective statistical analysis with the systematic experimental design makes it clear that the selection of the development technique and the mindfulness of the environmental factors are essential aspects that should be considered when trying to retrieve latent fingerprints on surfaces that were exposed to water.

- Methodological Contributions and Future Directions:

Despite the established methodology of the development techniques discussed in this paper, the paper brings forward a new environmental aspect in that the efficacy of the development techniques are compared in the different water chemistries of hard water, mineral water, and rainwater that were found in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. The methodology is useful in improving the operational applicability of the existing procedures and offers the empirical advice or direction to forensic practitioners in the context of water-related evidence recovery.

Nevertheless, we recognize that there exist severe methodological constraints, which will be tackled in further studies. Although the five-point qualitative scale of scoring used is practical and would offer a rational evaluation of the fingerprint utility in the field situation, it is recommended that future studies consider objective quantitative measures to increase the level of scientific rigidity and allow for making a clear comparison with the international standards.

- Specific Recommendations for Future Research:

In future investigations, limitations that are present should be countered by the inclusion of the following:

- Objective Minutiae-Based Quality Metrics:

- i.

- Counting of Type II and Type I minutiae Manual and automated (Type I and Type II) Minutiae counting.

- ii.

- Setting of threshold values that corresponded to the forensic identification standards (e.g., 12-point minimum required to be identified as positive).

- iii.

- Measures of continuity of ridge flows and quantitative clarity.

- iv.

- Use of universal measure of biometric quality (ISO/IEC 29794-1, NIST NFIQ) [38].

- Advanced Imaging and Documentation Techniques:

- i.

- Application of forensic light sources (alter light sources, UV light, RUVIS).

- ii.

- Introduction of fluorescent dyes after development of increased contrast.

- iii.

- Background suppressing image processing software with background preserving ridges.

- iv.

- Multi-imaging (white light and oblique lighting and reflected UV) of complete documentation.

- v.

- Implementation of SWGFAST guidelines of standardized fingerprint photography.

- Expanded Experimental Design:

- i.

- Several fingerprint donors to determine inter-individual compositional variability.

- ii.

- A wide range of ages and both sexes in order to measure the influence of hormones and age.

- iii.

- Other types of substrates (plastics, ceramics, coated metals, painted surfaces, etc.).

- iv.

- Long time series with increased sampling rate to obtain degradation kinetics.

- Independent Environmental Variable Analysis:

- i.

- Controlled independent variable systematic variation in temperature (10–40degC range).

- ii.

- pH change (4–9 range) to measure the acidity/alkalinity effects.

- iii.

- Evaluation of water flow dynamics (static and flowing water).

- iv.

- Assessing the effects of UV radiation and sunlight degradation.

- v.

- Microbiological tests such as biofilm formation and colonization of bacteria.

- Advanced Chemical and Physical Analysis:

- i.

- Extensive water chemistry (trace metals, organic pollutants, TDS, oxidation–reduction potential).

- ii.

- Interaction analysis spectroscopic (FTIR, Raman spectroscopy) of residue-water.

- iii.

- Pre- and post-submersion surface analysis of substrates (SEM, AFM, contact angle measurements).

- iv.

- Degradation processes Kinetic modeling.

- Enhanced Statistical and Validation Approaches:

- i.

- Extensive water chemistry (trace metals, organic pollutants, TDS, oxidation–reduction potential).

- ii.

- Interaction analysis spectroscopic (FTIR, Raman spectroscopy) of residue-water.

- iii.

- Pre- and post-submersion surface analysis of substrates (SEM, AFM, contact angle measurements).

- iv.

- Degradation processes Kinetic modeling.

- Practical Forensic Protocol Development:

- i.

- User-friendly field testing kits of water chemistry.

- ii.

- Decision matrices that are used to match water parameters with the best development techniques.

- iii.

- Aquatic evidence recovery standard operating procedures (SOPs).

- iv.

- Forensic Personnel Training Modules on the basis of study findings.

These enhancements will boost the generalizability and scientific rigor of the findings and still make them practically relevant to the field investigators. Future studies can close the divide between applied forensic practice and scientific validation through the combination of objective quantitative measurements with sophisticated imaging technology.

Although the limitations have been mentioned, this study brings much-needed baseline data to the forensic practitioners working in the Shekhawati region and such areas with the presence of water with a high mineral content. The universal excellence of cyanoacrylate fuming under varying conditions makes it the technique of choice as a method of recovering fingerprints on non-porous evidence that has been immersed in water. The statistical confirmation of the effects of water type and the time of immersion offers the evidence-based approach to the prioritization of the evidence recovery work and the choice of the relevant development approaches in the context of the case-specific environmental factors.

Further studies that will consider the mentioned methodological improvements will expand on the suggested background findings to establish holistic, scientifically supported protocols of fingerprint recovery in aquatic environments that can be utilized in a wide range of geographical and environmental settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.S. and A.G.; Methodology: A.G., M.S. and V.D.; Validation: S.S. and K.K.; Formal analysis: S.S.; Investigation: A.G. and M.S.; Resources: K.K.; Data curation: V.D.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.G. and M.S.; Writing—review and editing: S.S. and K.K.; Visualization: A.G.; Supervision: S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the individual who provided fingerprint samples for this study. No personal or identifying information was collected.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere gratitude to the Department of Forensic Science, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Mody University of Science and Technology, Lakshmangarh, Rajasthan, for providing laboratory facilities and technical assistance during the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| ABFO | American Board of Forensic Odontology |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CGWB | Central Ground Water Board |

| Cl− | Chloride Ion |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| GRM | General Reagent Grade |

| K | Potassium |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| MoS2 | Molybdenum Disulfide |

| Na | Sodium |

| pH | Potential of Hydrogen (acidity/alkalinity scale) |

| SDS | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate |

| SO42− | Sulfate Ion |

| SPR | Small Particle Reagent |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Abedi, M.; Afoakwah, C.; Bonsu, D.N.O.M. Lip print enhancement. Forensic Sci. Res. 2022, 7, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, A.; Farrukh, M.A.; Ali, S.; Khaleeq-ur-Rahman, M.; Tahir, M.A. Development of latent fingermarks on various surfaces using ZnO-SiO2 nanopowder. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, S.; Sodhi, G.S.; Sanjiv, K. Visualization of Latent Fingermarks using Rhodamine B: A new method. Int. J. Forensic Sci Pathol. 2015, 3, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, M.M. Forensic Fingerprints; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saharan, S.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, B. Novel C stain-based chemical method for differentiating real and forged fingerprints. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, S.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, B. Forge fingerprints: Fabrication, development, and detection techniques. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Leg. Med. 2021, 24, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, S.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, B. Application of Hertzberg stain in the identification and differentiation of polyvinyl acetate-based forged fingerprints. Curr. Sci. 2022, 123, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, S.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, B. Iodine Potassium Iodide as a Potential Stain for Detection of Polyvinyl Acetate Based Forged Fingerprints. J. Punjab-Acad. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, I.Y. Effects of Aquatic Environments on the Detection of Latent Fingermarks on Paper. Master’s Thesis, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bleay, S.M.; Bailey, M.J.; Croxton, R.S.; Francese, S. The forensic exploitation of fingermark chemistry: A review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Forensic Sci. 2021, 3, e1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brčeski, I.; Vaseashta, A. Environmental forensic tools for water resources. In Water Safety, Security and Sustainability: Threat Detection and Mitigation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 333–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thandauthapani, T.D. The Role of Wetting Effects on the Development of Latent Fingermarks. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, C. Recovery of latent fingerprints on different substrates submerged under fresh water: A review. IP Int. J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 8, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.K.; Lee, H.C.; Ramotowski, R.; Gaensslen, R. Advances in Fingerprint Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dhall, J.K.; Kapoor, A. Development of latent prints exposed to destructive crime scene conditions using wet powder suspensions. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 6, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, S.; El Dine, F.B.; Elwakeel, Y.; AbdAllah, N. Development of latent fingerprints on non-porous surfaces recovered from fresh and sea water. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ground Water Year Book: Rajasthan 2021–2022; Central Ground Water Board, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India: Jaipur, India, 2022. Available online: https://share.google/8xCBq9GfQ4nl8sSYi (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P. The Quality Analysis of Ground Water of Fatehpur Shekhawati Block of Sikar District in Rajasthan: Assessing the Impact of High Fluoride Concentration in Groundwater on Public Health. J. Adv. Sch. Res. Allied Educ. 2019, 16, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Parag, Y.; Elimelech, E.; Opher, T. Bottled water: An evidence-based overview of economic viability, environmental impact, and social equity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.; Afoakwah, R.; Appiah, R.; Asante, E.; Arthur, F.; Khariyal, S. Optimization of the superglue fuming and powder technique for the enhancement of latent fingerprints from objects submerged in water: An experimental study in Ghana. J. Forensic Sci. Med. 2023, 9, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onstwedder, J., III; Gamboe, T., Jr. Small particle reagent: Developing latent prints on water-soaked firearms and effect on firearms analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 1989, 34, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.; Paula, R.B.A.; Okuma, A.; Costa, L.M. Fingerprint Development Techniques: A Review. Rev. Virtual Química 2021, 13, 1278–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapecar, M. Finger marks on glass and metal surfaces recovered from stagnant water. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yamashita, B.; French, M. Fingerprint Sourcebook-Chapter 7: Latent Print Development; US Department Justice Office Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mouli, P.C.; Mohan, S.V.; Reddy, S.J. Rainwater chemistry at a regional representative urban site: Influence of terrestrial sources on ionic composition. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, A.; Francés, F.; Verdú, F. Solving underwater crimes: Development of latent prints made on submerged objects. Sci. Justice 2013, 53, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbrah, G.S. Cyanoacrylate fuming method for detection of latent fingermarks: A review. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F. Recovery of latent fingermarks on metal part of motorcycle submerged in different aquatic environments. Sains Malays. 2021, 50, 2343–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.E.Z.; Santana, R.G.; Guilhermetti, M.; Camargo Filho, I.; Endo, E.H.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Nakamura, C.V.; Dias Filho, B.P. Comparison of the bacteriological quality of tap water and bottled mineral water. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2008, 211, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, H.; P Lamba, N.; Kumar, P. Physico-Chemical Analysis of Groundwater of Shekhawati Vicinity of Rajasthan (Pre-Monsoon). Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadd, S.; Islam, M.; Manson, P.; Bleay, S. Fingerprint composition and aging: A literature review. Sci. Justice 2015, 55, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, A.; Ramotowski, R.; Weyermann, C. Composition of fingermark residue: A qualitative and quantitative review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 223, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alcaraz-Fossoul, J.; Mestres Patris, C.; Balaciart Muntaner, A.; Barrot Feixat, C.; Gené Badia, M. Determination of latent fingerprint degradation patterns—A real fieldwork study. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2013, 127, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.J.; Downham, R.; Sears, V. Effect of substrate surface topography on forensic development of latent fingerprints with iron oxide powder suspension. Surf. Interface Anal. 2010, 42, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadry, S. Corrosion analysis of stainless steel. Eur. J. Sci. Res 2008, 22, 508–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran, S.T.; Baranidharan, K.; Uthayakumar, M.; Parameswaran, P. Corrosion studies on stainless steel 316 and their prevention-a review. Incas Bull. 2021, 13, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucha-Urbanik, K.; Skowrońska, D.; Papciak, D. Assessment of corrosion properties of selected mineral waters. Coatings 2020, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 29794-1:2024; Information Technology—Biometric Sample Quality—Part 1: Framework. ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).