A Rare Case of Paternal Filicide Involving Combined Lethal Methods: Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation and Literature Review

Abstract

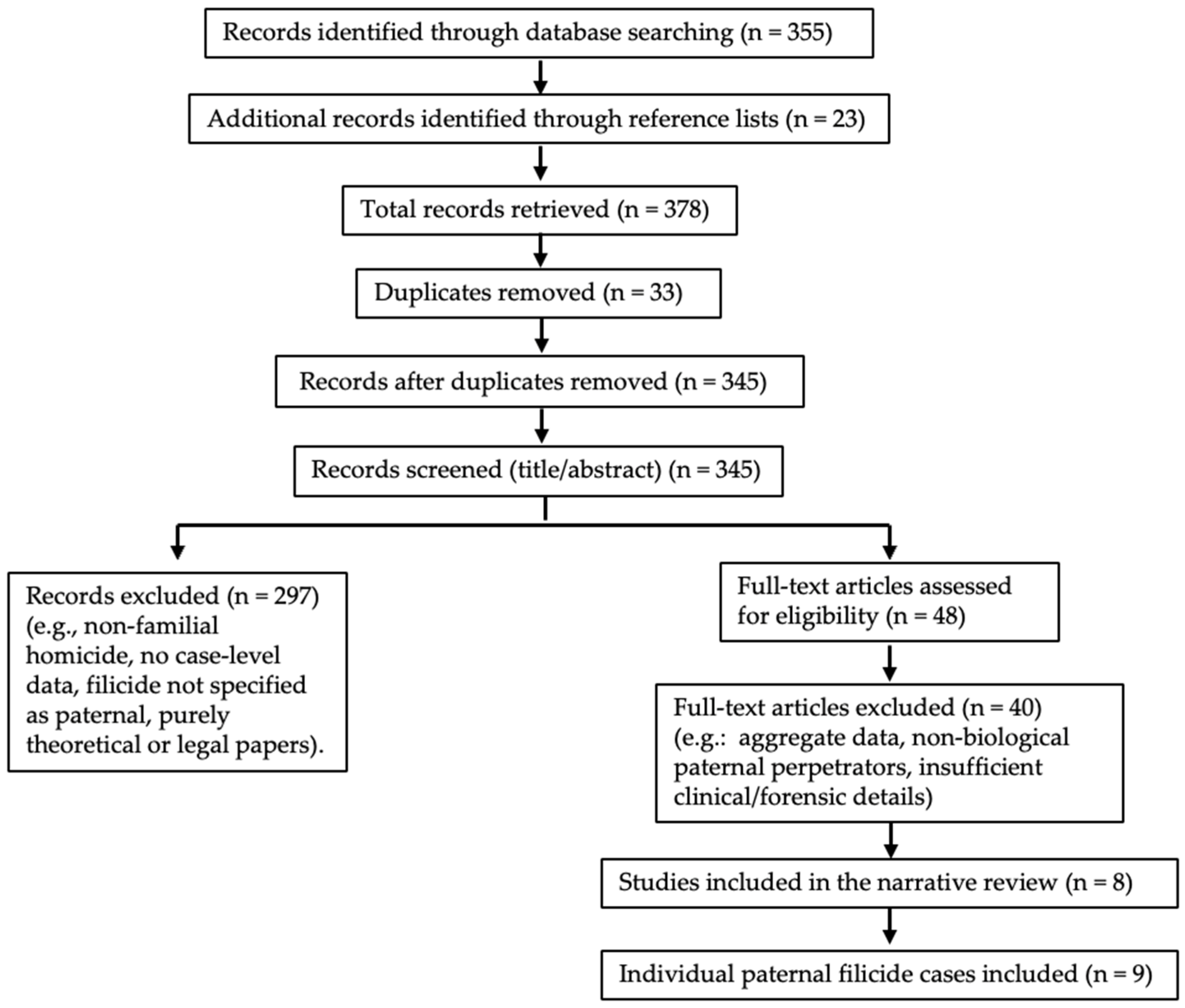

1. Introduction

2. Detailed Case Description

2.1. Case-Based Forensic and Psychiatric Evaluation

- Forensic medical inspection of the crime scene;

- Full autopsy, performed at the competent forensic pathology service, aimed at determining the cause of death and identifying the injury patterns. The autopsy was accompanied by toxicological analyses of biological samples (blood and urine) from the victim;

- Clinical and forensic psychiatric evaluation of the perpetrator, structured as follows:

- 1.

- medical history collection through consultation with the treating physician;

- 2.

- direct psychiatric examination through structured clinical interviews and behavioral observation;

- 3.

- document review, including prior medical records, forensic reports, and judicial files;

- 4.

- administration of selected psychodiagnostic instruments, including

- ○

- SCID-5 (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5) for the assessment of major psychiatric disorders;

- ○

- MMPI-2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2) for personality structure and potential dissimulation or distortion;

- ○

- PCL-R (Psychopathy Checklist–Revised) for the evaluation of antisocial and psychopathic traits;

- ○

- WAIS-IV (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition) to assess global cognitive functioning and rule out significant intellectual deficits.

2.2. Circumstantial Data and Event Reconstruction

2.3. Crime Scene Findings and Inspection

2.4. Post-Mortem Findings

2.5. Psychiatric–Forensic Profile of the Perpetrator and Judicial Outcome

- SCID-5 confirmed the diagnosis of adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, DSMV-309.4 (F43.25) [12], with no evidence of psychosis or mood disorders with psychotic features.

- MMPI-2 revealed a valid and consistent profile marked by elevations on scales 4 (Psychopathic Deviate), 6 (Paranoia), and 9 (Hypomania), reflecting emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, interpersonal conflict, and a tendency to externalize blame. No significant elevation was observed on scales 2 (Depression) or 8 (Schizophrenia).

- PCL-R indicated a moderate score (21–23/40), below the clinical cutoff, with greater expression of Factor 1 traits (superficial affect, lack of empathy, manipulativeness) and less pronounced Factor 2 traits (impulsivity, antisocial behavior).

- WAIS-IV showed an overall IQ within normal limits (90–109), with no evidence of cognitive deterioration or intellectual disability.

3. Discussion

- Perpetrator: age, available sociodemographic information, psychiatric history, post-homicide behavior;

- Victim: age, sex, presence of medical or psychiatric conditions;

- Event: presumed motive, method of killing, reported cause of death, toxicological findings.

3.1. Diagnostic Framing and Typology of Filicide

- the recent and conflictual separation of the parents, with a judicial order of paternal removal from the family home due to physical and psychological violence toward the mother;

- the total absence of prior violent behavior toward the child, who was instead attacked at the first opportunity of contact post-separation;

- the symbolic and temporal choice of assault, coinciding with the first exclusively shared time with the child at the family home;

- the use of combined lethal means, with a high destructive charge and demonstrative potential (asphyxiation, penetrating wounds, use of adhesive tape, body concealment);

- the subsequent low-lethality suicidal staging, which in fact was never carried out and bears no real self-harm intent, more plausibly demonstrative and aimed at eliciting a reaction in the ex-partner.

3.2. Crime Dynamics and Medico-Legal Aspects

3.3. Post-Crime Behavior and Suicide Assessment

3.4. Psychopathological Profile and Criminal Responsibility Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flynn, S.M.; Shaw, J.J.; Abel, K.M. Filicide: Mental illness in those who kill their children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourget, D.; Bradford, J.M.W. Homicidal parents. Can. J. Psychiatry 1990, 35, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, A.; Kumpulainen, K.; Karkola, K.; Vanamo, T.; Merikanto, J. Maternal and paternal filicides: A retrospective review of filicides in Finland. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2010, 38, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Putkonen, H.; Amon, S.; Eronen, M.; Klier, C.M.; Almiron, M.P.; Cederwall, J.Y.; Weizmann-Henelius, G. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics: A comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourget, D.; Gagné, P. Maternal filicide in Québec. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2002, 30, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Resnick, P.J. Child murder by parents: A psychiatric review of filicide. Am. J. Psychiatry 1969, 126, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanesi, R.; Rocca, G.; Candelli, C.; Solarino, B.; Carabellese, F. Death by starvation: Seeking a forensic psychiatric understanding of a case of fatal child maltreatment by the parent. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 223, e13–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Dawson, M. Filicide and criminal justice outcomes: Are maternal and paternal perpetrators treated differently? Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 157, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, K.; Dobash, R.E.; Dobash, R.P. The murder of children by fathers in the context of child abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M. Canadian trends in filicide by gender of the accused, 1961–2011. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 47, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temrin, H. Paternal Filicide in Sweden: Background, Risk Factors and the Cinderella Effect. Evol. Psychol. 2024, 22, 14747049241265623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcanlı, T.; Okur, İ.; Aksoy Poyraz, C.; Kocabaşoğlu, N.; Aslıyüksek, H. Patterns in paternal and maternal filicide: A comparative analysis of filicide cases in Turkey. J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 69, 2110–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, M.; Lorente, M. Killing of sons and daughters: A systematic review for analysing the elements to distinguish the different features and circumstances related to these filicides. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.; Shaw, J.; Abel, K.M. Homicide of infants: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi-Guarnieri, D.; Janofsky, J.; Keram, E.; Lawsky, S.; Merideth, P.; Mossman, D.; Schwart-Watts, D.; Scott, C.; Thompson, J., Jr.; Zonana, H. AAPL practice guideline for forensic psychiatric evaluation of defendants raising the insanity defense. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2002, 30, S3–S40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Völlm, B.A.; Clarke, M.; Herrando, V.T.; Seppänen, A.O.; Gosek, P.; Heitzman, J.; Bulten, E. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on forensic psychiatry: Evidence based assessment and treatment of mentally disordered offenders. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 51, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrun, K.; Collins, S. Evaluations of trial competency and mental state at time of offense: Report characteristics. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1995, 26, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatteo, D.; Olver, M.E. Use of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised in Legal Contexts: Validity, Reliability, Admissibility, and Evidentiary Issues. J. Personal. Assess. 2021, 104, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgen, T.G.; Bang, N.; Nonstad, K.; Søndenaa, E. Adaptive and cognitive functioning in forensic examinations. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codice Penale: Con Costituzione e Leggi Complementari, 49th ed.; Edizioni Giuridiche Simone: Naples, Italy, 2026.

- Codice di Procedura Penale: Con Costituzione e Leggi Complementari, 48th ed.; Edizioni Giuridiche Simone: Naples, Italy, 2026.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samir, N.Y.A.; Abouzahir, H.; Belhouss, A.; Benyaich, H. A case report of paternal filicide covered up as a fall. Int. J. Forensic Med. 2021, 3, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najari, F.; Soleimani, L.; Najari, D. Filicide by electrocution. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Forensic Med. 2019, 9, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli, S.R. Filicide-suicide: A case report on triple hanging. J. Chitwan Med. Coll. 2021, 11, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, F.; Meganck, R.; Audenaert, K. A case study of paternal filicide-suicide: Personality disorder, motives, and victim choice. J. Psychol. 2016, 151, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.B.; Rolf, C.M.; Goolsby, M.E.; Hunsaker, J.C., 3rd. Filicide-suicide: Case series and review of the literature. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2015, 36, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikary, A.K.; Behera, C. Homicidal methanol poisoning in filicide-suicide. Med.-Leg. J. 2017, 85, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melez, İ.E.; Avşar, A.; Başpınar, B.; Melez, D.O.; Şahin, F.; Özdeş, T. Simultaneous homicide-suicide: A case report of double drowning. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazer, D.; Kannikeswaran, N.; Schmidt, C. Commotio cordis: A case report of a fatal blow. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourget, D.; Grace, J.; Whitehurst, L. A review of maternal and paternal filicide. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2007, 35, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hatters Friedman, S.; Resnick, P.J. Child murder by mothers: Patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, M.; Koenraadt, F. Filicide: A comparative study of maternal versus paternal child homicide. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2008, 18, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, D.F.; Evinç, Ş.G. Killing One’s Own Baby: A Psychodynamic Overview with Clinical Approach to Filicide Cases. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. 2021, 32, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, L.; Bramante, A.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M. Mothers who murdered their child: An attachment-based study on filicide. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, P.G.; Campbell, M.; Olszowy, L.; Hamilton, L.H.A. Paternal filicide in the context of domestic violence: Challenges in risk assessment and risk management for community and justice professionals. Child Abus. Rev. 2014, 23, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez Borrego, S.; Guàrdia Olmos, J.; Aliaga Moore, Á. Child homicide by parents in Chile: A gender-based study and analysis of post-filicide attempted suicide. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2013, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Wilson, M.I. Some differential attributes of lethal assaults on small children by stepfathers versus genetic fathers. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1994, 15, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes-Shackelford, V.A.; Shackelford, T.K. Methods of filicide: Stepparents and genetic parents kill differently. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G. An overview of filicide. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inoue, H.; Ikeda, N.; Ito, T.; Tsuji, A.; Kudo, K. Homicidal sharp force injuries inflicted by family members or relatives. Med. Sci. Law 2006, 46, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.H.; Hrouda, D.R.; Holden, C.E.; Noffsinger, S.G.; Resnick, P.J. Filicide-suicide: Common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2005, 33, 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- Putkonen, H.; Weizmann-Henelius, G.; Lindberg, N.; Eronen, M.; Häkkänen, H. Differences between homicide and filicide offenders: Results of a nationwide register-based case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacco, S.; Tarter, I.; Lucchini, G.; Cicolini, A. Filicide by mentally ill maternal perpetrators: A longitudinal, retrospective study over 30 years in a single Northern Italy psychiatric-forensic facility. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2023, 26, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, W.C.; Lee, E.; Montplaisir, R.; Lazarou, E.; Safarik, M.; Chan, H.C.O.; Beauregard, E. Revenge filicide: An international perspective through 62 cases. Behav. Sci. Law 2021, 39, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.G.; Friedman, S.H.; Resnick, P.J. Fathers who kill their children: An analysis of the literature. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, L.; Poulin, B.; Marleau, J.; Roy, R.; Webanck, T. Filicidal women: Jail or psychiatric ward? Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.H.; Hrouda, D.R.; Holden, C.E.; Noffsinger, S.G.; Resnick, P.J. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: An examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J. Forensic Sci. 2005, 50, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.G.; Carabellese, F. Evaluation and management of violence risk for forensic patients: Is it a necessary practice in Italy? J. Psychopathol. 2021, 27, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Tyson, D.; Arias, P.F.; Razali, S. The challenge of understanding and preventing filicide. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1159443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year | Perpetrator Demographics | Psychiatric History | Victim Demographics | Victim Medical History | Motive | Method of Filicide | COD 1 | Post-Homicide Behavior | Toxicology (Victim) | Toxicology (Perpetrator) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samir NYA, 2021 [24] | NR 2 | Negative | M, 1 yrs | NR | Spouse revenge and paternal jealousy. | Repeated blunt impact (against wall) and biting | Multiple blunt force injuries | False claim of accident (fall from sofa) → full confession | NR | NR |

| Najari F, 2019 [25] | NR | Bipolar disorder, intermittent treatment | M, 8 yrs | NR | Marital conflict and custody dispute | Electrocution during sleeping 3 | Cardiac complications due to electrocution | Also killed ex-wife by strangulation | Negative | NR |

| Parajuli, SR, 2021 [26] | 35 yrs, farmer; recently separated. | Negative | M, 5 yrs; F, 3 yrs | Negative | Probable altruistic motive to prevent suffering | Incomplete hanging with single ligature | Asphyxia | Suicide by hanging | NR | NR |

| Declercq, F, 2016 [27] | Father of 3; self-employed; high education; elevated socio-economic status | Schizoid Personality Disorder. Major depression post-separation; prior suicide attempt by overdose | M, 9 yrs | Autism and rare genetic disease (same as deceased sibling) | Dual motive: spousal revenge and altruism | Sedatives followed by manual strangulation | Asphyxia | Unsuccessful suicide attempts by drug overdose, auto-strangulation, and attempted drowning | Positive | Positive |

| Shields LB, 2015—Case 2 [28] | 46 yrs | History of alcohol-fueled rampages and threats | M, 9 months | NR | NR | Firearm | Gunshot wounds | Completed suicide by gunshot wound (intraoral) | NR | Blood ethanol 0.176 g/100 mL |

| Shields LB, 2015—Case 3 [28] | NR | NR | F, 13 yrs | Angelman syndrome | Altruism | CO intoxication | Asphyxia due to CO intoxication; contributory cause: positional asphyxia (prone position on mattress) | Completed suicide by CO poisoning | CO-Hb post-mortem 66% | CO-Hb post-mortem 75% |

| Sikary AK, 2017 [29] | Male, father; business owner in financial distress | NR | M, 18 yrs | Poliomyelitis; mental and physical disability | Altruism (Financial loss and hopelessness) | Methanol poisoning | Methanol toxicity (39.5 mg/100 mL) | Suicide by jumping in front of train with wife | Methanol 39.5 mg/100 mL; ethanol 1.8 mg/100 mL | NR |

| Melez İE, 2023 [30] | M, 30 yrs, shipyard worker | NR | F, 5 yrs | NR | Spousal revenge and child custody dispute | Drowning (Victim bound to perpetrator) | Asphyxia due to drowning | Drowning—suicide | NR | NR |

| Nazer D, 2021 [31] | NR | NR | M, 6 months | Negative | Accidental | Blunt trauma to chest | Cardiac arrest secondary to commotio cordis | Called EMS 4; confessed to assault | NR | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cecannecchia, C.; Giacani, E.; Baldari, B.; Bellomo, A.; Cipolloni, L.; Cioffi, A. A Rare Case of Paternal Filicide Involving Combined Lethal Methods: Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation and Literature Review. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040080

Cecannecchia C, Giacani E, Baldari B, Bellomo A, Cipolloni L, Cioffi A. A Rare Case of Paternal Filicide Involving Combined Lethal Methods: Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation and Literature Review. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleCecannecchia, Camilla, Elena Giacani, Benedetta Baldari, Antonello Bellomo, Luigi Cipolloni, and Andrea Cioffi. 2025. "A Rare Case of Paternal Filicide Involving Combined Lethal Methods: Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation and Literature Review" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040080

APA StyleCecannecchia, C., Giacani, E., Baldari, B., Bellomo, A., Cipolloni, L., & Cioffi, A. (2025). A Rare Case of Paternal Filicide Involving Combined Lethal Methods: Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation and Literature Review. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040080