Abstract

Background/Objectives: The external occipital protuberance (EOP) is an anatomical landmark with radiological and anthropological implications. Although the morphology and prevalence of EOP have been studied in many populations, data remain lacking for Northeastern Thais. Population-specific characterization of EOP variation may improve diagnostic and forensic accuracy applications. Materials and Methods: This study has investigated the prevalence and morphometry of EOPs using two primary sources: CT brain scans from 750 adult patients (375 males, 375 females) and anatomical investigations of 1060 dry skulls. EOPs were classified as Type I (flat), Type II (crest), or Type III (spur). Measurements for Type II (crest-shaped) EOPs were performed using standardized linear and angular parameters. Data differences were analyzed by sex and age group; intra- and inter-observer reliability was calculated for imaging measurements. Results: The study showed that Type II EOP was most common in both CT (56.1%) and dry skull (64.6%) samples. Type I was significantly more frequent in females (CT: 37.0%; dry skull: 32.8%), while Type III prevalence was higher in males (CT: 28.5%; dry skull: 18.4%). After age 60, the incidence of Type III declined in both datasets. Type II EOPs were significantly larger in males (mean crest length in CT: males 7.1 ± 0.1 mm, females 5.6 ± 0.1 mm; p < 0.001), with notable sex- and age-associated variation in associated angular dimensions. Conclusions: These findings established the first region-specific morphometric reference database for EOP in Northeastern Thais. The demonstrated sexual dimorphism in Type II EOP measurements provided the foundational data that may support future applications in clinical assessment, radiological interpretation, and forensic sex estimation in this population.

1. Introduction

The external occipital protuberance (EOP) is a prominent projection of the compact occipital bone at the midline of the posteroinferior cranium. Anatomically, EOP serves as the primary attachment site for the nuchal ligament and trapezius muscle. The morphological and metric significance of the occipital bone, including the EOP, has been recognized in anthropological and anatomical sciences since the early development of physical anthropology [1], with systematic investigations continuing throughout the 20th century [2] and expanding with modern imaging techniques [3]. The highest point of the EOP is named the inion, which can be used as a landmark in both anthropological and clinical settings. In the literature, based on its anatomical shape observed in CT images, dry craniums or cadaveric specimens, EOP is classified into three major types, including Type I (flat or smooth), Type II (crest), and Type III (spine, occipital spur, elongated-shaped), respectively [4,5,6]. It has been reported that Type II or III EOP development enlargement, attributed to mechanical forces acting on the insertion of ligament and muscle attachment sites, is associated with increased repetitive stress and tension, causing intensive neck muscle use, forward head posture, or poor posture habits [7,8].

Knowledge of the incidence and morphometry of the EOP types is significantly important in medical clinics and anthropological fields for many reasons. For surface anatomy and clinical landmarks, EOP is used in mapping for neuroimaging and as a guide for surgical interventions at the craniovertebral junction [9]. This information can inform local interventions like anesthetic or steroid injections for occipital neuralgia. In addition, variations in the EOP, particularly the presence of Type III, can be associated with symptoms such as pain or tenderness at the back of the head when lying down. Therefore, recognizing EOP variants can help clinicians to differentiate normal anatomical prominences from pathological developments such as tumor masses or exostoses and to prevent unnecessary intervention [8]. Moreover, its morphometry and distribution are also valuable in forensic and anthropological applications, particularly in sex determination of skeletal remains, as pronounced EOP Type III is more common in males [8,10]. Taken together, basic knowledge of EOP prevalence not only supports accurate diagnostics and targeted treatment in clinical practice but also aids surgical planning, pain management, and anthropological forensic assessments.

To better understand the prevalence across different populations, the EOP variations and morphometry have been documented in several countries, including India [11,12], Turkey [10,13], Korea [14], Australia [15], and France [16]. In the literature, however, the incidence of EOP types and morphometric data investigated in both CT scans and dry crania have never been reported in the Northeastern Thai population. Although the EOP variation has been documented in various populations, no morphometric data exist for Northeastern Thai populations, creating a critical gap in forensic identification standards for this region. This study addressed three specific goals: (1) establishing population-specific baseline morphology for forensic comparison, (2) cross-validating CT and osteological methods for dual-applicability, and (3) quantifying sexually dimorphic EOP parameters for integration into sex estimation protocols. We hypothesized that EOP morphology exhibited significant sexual dimorphism in Northeastern Thais, with Type III prevalence and Type II dimensions differing sufficiently between sexes to aid forensic identification. Therefore, this recent study aimed to provide the prevalence and comprehensive morphometric data on the EOPs observed from CT scans and dry skulls, which may assist clinicians in the diagnosis and management of occipital-related symptoms and improve radiological accuracy and forensic identification, reflecting our population-specific characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collections and Ethical Approval

This study has employed a quantitative, observational, descriptive cross-sectional study design by using computed tomography (CT) brain scans of patients with head injuries from the Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Srinagarind Hospital, and the cranial bone specimens from body donors systemically housed in the Unit of Human Bone Warehouse for Research (UHBW), Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University. Skeletal specimens represent individuals who died between 1978–2024. Geographically, the collection comprises skulls from individuals identified from Northeastern Thailand. The research protocol was approved by the Center for Ethics in Human Research, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, under ethics approval number “HE661603”.

2.2. CT Scan Collection and Analysis

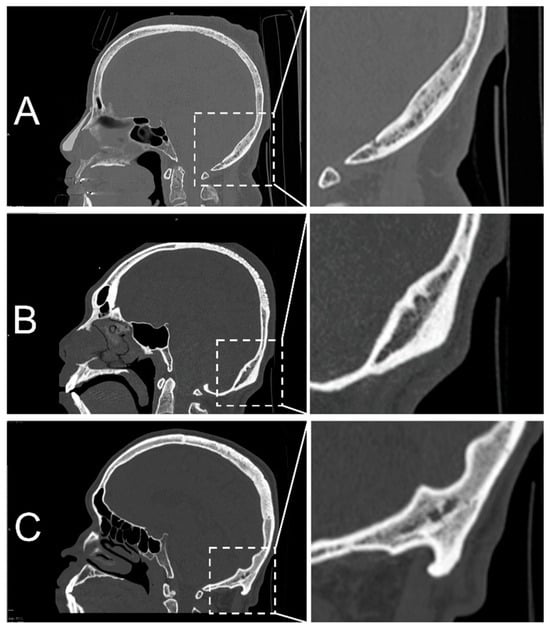

This retrospective analysis was conducted to investigate the incidence and morphology of EOP using CT brain head injury data obtained from the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) spanning from July 2022 to November 2023. A total of 750 patients (375 males and 375 females) with inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study before their demographics, including sex and age, were recorded. The patients had a mean age of approximately 53.71 ± 0.83 years (range 18 to 98 years). Then, the CT brain head injury images were systematically reviewed using bone window settings in both axial and sagittal planes, supplemented by lateral skull or scout images obtained from the PACS. Each patient’s EOP was further classified according to the morphological categories as shown in Figure 1. CT examination was performed using GE Optima CT660 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with the standard protocol of head injury. The multiplanar reconstruction of axial, coronal, and sagittal planes was performed using a bone reconstruction algorithm. The slice thickness and slice interval were set as 1 mm with the window width and window levels of 2400 and 600, respectively.

Figure 1.

Presence and types of EOP investigated in CT scans. (A) Type I (flat-shaped), (B) Type II (crest-shaped), and (C) Type III (spine/occipital spur/elongated-shaped).

2.3. Dry Skull Collection

This study has utilized a total of 1060 dry skull/cranial specimens following the exclusion based on the criteria that could affect the morphology and integrity of EOP type, such as evidence of trauma, lesions, surgical interventions, or other conditions. It was noted that while skulls with obvious pathological changes were excluded, subclinical age-related conditions (osteoporosis, metabolic bone disease) or ongoing skeletal development in young adults (18–25 years) could not be systematically assessed and represent potential confounding factors. These dry specimens were categorized into two groups: 187 skulls with unspecified sex and 873 identified skulls with documented sex and age information (399 females and 474 males). Two experienced observers (a radiologist and an anatomy professor) have performed the independent classifications. Intra-observer and inter-observer reliability were assessed using Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) with a two-way mixed effects model and absolute agreement. All measurements demonstrated excellent reliability, with intra-observer ICC values ranging from 0.962 to 0.997 and inter-observer ICC values ranging from 0.980 to 0.999. These results indicate high consistency and reproducibility of the measurement protocol.

2.4. Classification of EOP Types

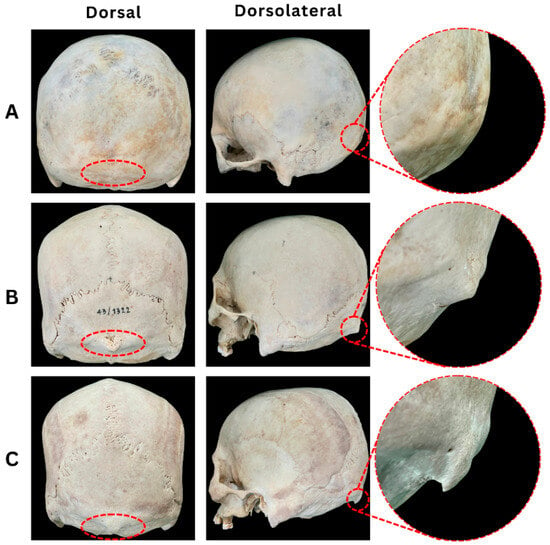

The EOP types investigated in both CT scan images and dry skull samples in this study were classified into three types (“Type I” [flat or smooth type], “Type II” [crest type], and “Type III” [spine/spur/elongated type], respectively) depending on their shapes as previously described [4,5,13]. It was noted that, in our study, these types of EOP could also be obviously determined in both CT images (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and dry skull samples as demonstrated in Figure 3. All classifications were performed independently by both observers across both dry skull and CT scan sample types.

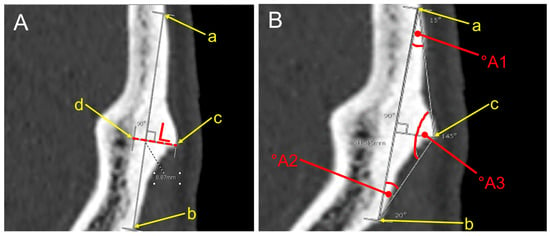

Figure 2.

Morphometric measurements of EOP Type II (crest). (A) Length of the EOP crest (L): the distance between the tip (point c or also called “inion”) and the compact bone base (point d) of EOP, a line drawn through and perpendicular to the baseline drawn between the ends of the two bases (a and b) of the EOP Type II. (B) Measurement of three angles of a triangle (°A1, °A2, and °A3) drawn through 3 points (a, b, and c) of EOP Type II.

Figure 3.

Presence and types of EOP (red ovals and circles) based on their shapes observed on dry cranial bones. (A) Type I (flat or smooth), (B) Type II (crest-shaped), and (C) Type III (spur/spine or elongated-shaped).

2.5. Morphometric Measurements

Since EOP Type II appears as compact bone with a predominantly triangular geometric configuration on the CT scan image (Figure 2), this study attempted to quantify its morphological characteristics (Figure 3). EOP morphology was evaluated by using sagittal plane images, with the clearest EOP visualization selected based on concurrent axial plane assessment, as demonstrated in Figure 2. For morphometric analysis, three reference points (a, b, c) were established on the selected images, followed by measurement of the designated angles, °A1, °A2, and °A3, respectively. Subsequently, the length of the EOP crest (L) was measured by drawing a straight line from the point c to the base of the compact bone margin of the EOP (point d). This measurement required drawing a line perpendicular to the triangular baseline between points a and c (named “inion”), as demonstrated in Figure 2A. All measurements were performed independently by two radiologists before data reliability analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by using SPSS version 28 software and the normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.), median, frequency, and percentage. Morphological data of EOP were analyzed and compared between male and female groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test, while comparisons across different age groups were conducted using the independent median test. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using pairwise comparison analysis. The measurement consistency of EOP Type II data from CT images was evaluated for both inter-observer reliability and intra-observer reliability using the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Reliability

For reliability analysis, morphological characteristics of EOP Type II were assessed by two different radiologists using CT scan data from 20 patients. Analyzed by using the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), the results demonstrated high ICCs for intra-observer reliability: radiologist 1 (L, 0.99–0.998; °A1, 0.949–0.99; °A2, 0.91–0.982; °A3, 0.986–0.997) and radiologist 2 (L, 0.998–1; °A1, 0.927–0.985; °A2, 0.938–0.987; °A3, 0.975–0.995). The inter-observer reliability also showed high ICC values (L, 0.999–1; °A1, 0.946–0.992; °A2, 0.975–0.996; °A3, 0.983–0.997). These findings indicated the excellent measurement reliability for various EOP Type II parameters between two observers, confirming the consistency and reproducibility of the CT morphological assessment methodology.

3.2. Types and Prevalence of EOP Observed in CT Scans and Dry Skulls

As investigated in both CT scan images and dry skulls, it was revealed that the types of EOP observed in the Northeastern Thai population could be classified into three major types: Type I (flat or smooth), Type II (crest-shaped), and Type III (spur/spine or elongated-shaped), respectively, as demonstrated in Figure 1 and Figure 3.

Table 1 showed that the highest incidence of EOP found in Northeastern Thais was Type II in both CT (51.1%) or dry skull (64.6%) investigations as compared to that of Type I (CT [24.7%], dry bone [21.3%]) and Type III (CT [19.2%], dry skull [14.1%]), respectively. Compared to males, it was observed that the prevalence of only EOP Type I was higher in females (CT [37%] and dry skull [32.8%]). In the same vein, Type III was more present in males (CT [28.5%] and dry skull [18.4%]) when compared to females (CT [10%] and dry skull [10%]), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of EOPs investigated in the Northeastern Thai CT scan images and dry skulls compared between sexes.

3.3. Incidence of EOPs According to Age Groups

Based on age range groups, it was revealed that the highest incidences on CT scans were found in Type I (18–30 years; 28.1%), II (31–40 years; 64.2%), and III (41–50 years; 24.4%), respectively (Table 2). On dry skulls, the Type II could be observed in the highest prevalent rate at two age ranges of 41–50 years (66.5%) and more than 60 years (66.5%). In both investigations (CT and dry skulls), Type III of EOP was found to be decreased after the age of 60 years (CT, 20.8% and dry skulls, 10.7%) as demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of EOP types according to age groups observed in CT images and dry skulls.

3.4. Morphometric Parameters Investigated in CT Scans of EOP Type II

Descriptive data of morphometric parameters measured from EOP Type II in CT scans with different age groups were shown in Table 3. It demonstrated that the maximum length of EOP Type II in females was observed in the 31–40 years age group (6.1 ± 0.5 mm), whereas in males, the greatest EOP length was found in the 41.50 years age group (7.16 ± 0.5 mm). Such lengths were inversely proportional to the narrowest angle measured at °A3 of females (137.89° ± 5.8) and males (132.8 ±1.9°) as compared to other age groups. However, the angular degrees of °A1 and °A2 varied among age groups of individual gender (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive morphometrical data of EOP Type II according to gender and age group.

3.5. Comparison of EOP Type II Measured in CT Scans Between Sexes

Table 4 shows that median values of all morphometric parameters for EOP Type II, including length (L) and angular measurements (°A1–°A3), were significantly greater in males compared to females (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Comparison of EOP I (crest-shaped) morphometry (length and angles) depending on gender.

4. Discussion

This study has evaluated the prevalence and morphometry of EOP types in the North-Eastern Thai population using both CT scans and dry skulls to provide the first population-specific dataset for our region. In both CT scans and skull specimens, three main EOP types (I, II, III) were also identified in Thais, similar to other populations [10,11,13,14,15,16]. It was found that Type II EOP was most common in Northeastern Thais (51.1% in CT scans and 64.6% in dry skulls). This incidence is notably higher than that of some reports from Indian [11], Turkish [10,13], or French populations [16], where Type I may predominate or Type III is comparatively more frequent [17]. Compared between sexes, Type I was observed more frequently in Thai females (CT: 37%, dry skull: 32.8%) than males, consistent with previous investigations that less-pronounced EOP forms were typically more common in women [17,18]. In contrast to females, Type III (spur/spine-shaped) showed a marked male predominance, found in 28.5% of males in CT scans and 18.4% in male skulls, versus 10% in females in both CT and skeletal data. This incidence was related to a previous study, demonstrating that EOP spurs were significantly more prevalent in males [18]. Our recent study has revealed the decreased incidence of Type III EOP after age 60 in both investigation modalities. It was assumed that it may reflect bone remodeling or age-related morphologic changes, though some studies indicated the relative stability of Type III prevalence in certain populations like French adults [16]. For morphometric analysis, the maximum EOP Type II length was greatest in males aged 41–50 years (7.16 ± 0.5 mm) and in females aged 31–40 years (6.1 ± 0.5 mm). Across age groups, the characteristic crest length and associated angles (°A1–°A3) varied, but all morphometric parameters were significantly larger in males (p < 0.001). Our results were comparable to previous studies that have demonstrated the strong sexual dimorphism in the EOP, especially for forensic sex estimation [5,14,19,20]. Although sex determination using a discrimination method is being developed in our anthropological forensic association, as reported in dry lumbar vertebrae [21], forearm bones [22], femur [23], ulnar [24], sternum [25], clavicle [26], occipital bone [27], and tibia and fibula [28], the sexual dimorphism in the EOP has never been reported. For further investigation, it is possible to use the Type II EOP morphometry observed in this recent study for sex estimation because all parameters were significantly different between sexes.

Our sample’s wide age range (18–98 years) required consideration of age-related skeletal changes that may influence EOP morphology. Young adults (18–25 years) may still undergo final cranial maturation, as skull development can extend to 25 years of age. In the youngest cohort (18–30 years) of this study, the relatively lower Type III prevalence (13.5% in CT scans) compared to the 41–50 age group (24.4%) may reflect incomplete EOP development, as mechanical stress effects from nuchal musculature accumulate over time [4,5]. On the contrary, the decline in Type III EOP after age 60 may be influenced by multiple factors: (1) age-related bone resorption and osteoporosis potentially reducing prominent bony features; (2) decreased mechanical loading from reduced mobility and muscle use, particularly of dorsal neck extensors; and (3) pathological conditions affecting bone remodeling. While our exclusion criteria eliminated obvious pathological specimens, subclinical conditions in CT patients cannot be entirely excluded. This cross-sectional design prevents distinguishing developmental maturation from age-related remodeling. It is possible that future longitudinal studies with bone density measurements and detailed medical histories would better elucidate these mechanisms.

The predominance of Type II in Northeastern Thais contrasts, for example, with South Indians, where Type I or Type III may be more prevalent, and Turkish populations in whom Type III (spur) prevalence is high and strongly associated with male sex [10,13,17]. In French young adults, the enlarged EOPs did not show major secular trends, and the overall incidence was lower, particularly in females [16]. Consistent with the literature, pronounced EOP (Type III/spine) is a reliable marker for male sex, useful for forensic and anthropological applications. Measurement reliability assessments in our study demonstrated the excellent intra- and inter-observer agreement (ICC values 0.91–1.0), underscoring the reproducibility of the CT-based morphometric method, as established in recent Turkish studies [13,29]. This is the first time to demonstrate that the Northeastern Thai population is characterized by a high prevalence of Type II EOP, distinctive sex-linked differences in EOP type and dimensions, and a reduction in Type III EOP with advanced age, highlighting both the population specificity and broader pattern consistency with previous studies [17,18].

For limitations, our study was retrospective and we had no control over the standardization of CT image demographic data for all participants, which may introduce variability. Only individuals with available head CT scans or dry skull specimens were included, potentially leading to selection bias and limiting generalizability to the wider Northeastern Thai population. The cross-sectional nature of the analysis could prevent any direct assessment of causality between EOP morphology and clinical symptoms or lifestyle factors. Unfortunately, our study did not evaluate the possible associations between EOP types and clinical manifestations because of a lack of symptomatic data in both samples. Morphometric measurements in this study were limited to the sagittal plane of CT scans and anterior–posterior perspectives on dry skulls, possibly overlooking more complex 3D variations in EOP morphology. In addition, the wide age range (18–98 years) encompassed individuals undergoing final skeletal maturation (18–25 years) and those potentially experiencing age-related bone remodeling, reduced mobility affecting muscle attachments, or pathological conditions. These factors may influence EOP morphology independently of population characteristics. The absence of bone density data or comprehensive medical histories limited our ability to control for pathological influences in elderly participants.

Although the recent study employed the descriptive statistics rather than predictive modeling, this approach was appropriate for establishing foundational population-specific reference data. Future research needs to incorporate these parameters into the multivariate discriminant function analyses for comprehensive sex estimation models.

5. Conclusions

We have provided the first comprehensive data on the prevalence and morphometry of EOP types in the Northeastern Thai population using both CT scans and dry skulls. The crest-shaped Type II EOP was the most common form, with pronounced sex differences and a reduction in Type III (spur) incidence in older individuals. All morphometric parameters of Type II EOP were significantly greater in males, suggesting the value of EOP features for sex estimation in forensic and clinical settings. These findings enhance the region-specific anatomical knowledge, supporting accuracy in diagnostic, surgical, and anthropological applications in the Northeastern Thai population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K. and S.I.; methodology, G.B., P.C. and P.A.; formal analysis, S.D. and C.P.; resources, S.I. and W.K.; data curation, G.B., P.C. and P.A.; visualization, G.B. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.K. and S.I.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; project administration, S.I.; funding acquisition, S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (Grant No. RR67003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The human ethical approval was obtained from the Center for Ethics in Human Research, Khon Kaen University (approval code: HE661603, 2 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (Grant No. RR67003).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Todd, T.W.; Lyon, D.W., Jr. Endocranial suture closure: Its progress and age relationship. Part I. Adult males of white stock. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1924, 7, 325–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, W.M. Human Osteology: A Laboratory and Field Manual of the Human Skeleton; Missouri Archaeological Society: Springfield, MO, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bolanowski, W.; Śmiszkiewicz-Skwarska, A.; Polguj, M.; Jędrzejewski, K.S. The external occipital protuberance: The role of testicular hormones. Folia Morphol. 2005, 64, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, D.; Ashraf, A.; Niknejad, M. Occipital spur. Radiopaedia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülekon, I.N.; Turgut, H.B. The external occipital protuberance: Can it be used as a criterion in the determination of sex? J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, R.C.; Abela, C.; Eccles, S. Painful exostosis of the external occipital protuberance. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 68, e174–e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Q.; Xiao, C.; Lau Rui Han, S.; Hu, S.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y.; Xiong, X.; Fang, S. The Association of Occipital Spur with Craniocervical Posture and Craniofacial Morphology. J. Pain Res. 2025, 18, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, S.R.; Varghese, E.; Kumbargere, S.N.; Chandrappa, P.R. Fused cervical vertebrae: A coincidental finding in a lateral cephalogram taken for orthodontic diagnostic purposes. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016217566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, S.; Ono, H.; Ishii, H. Correlation of the external occipital protuberance with venous sinuses: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2022, 44, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlayan, F.; Güller, H.; Öncü, E.; Kuzey, N.; Dalcı, H. The Frequency of Occipital Spurs in Relation to the Cephalic Index: An Anatomorphometric Cone Beam CT Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 27, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Singh, P. External occipital protuberance classification with special reference to spine type and its clinical implications. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2023, 45, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Asghar, A.; Srivastava, N.N.; Gupta, N.; Jain, A.; Verma, J. An Anatomic Morphological Study of Occipital Spurs in Human Skulls. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasani, H.; Özkan, M.; Celik, H.H. Assessment of external occipital protuberance morphometry in CT scans: Implications for determining age and sex. Int. J. Morphol. 2025, 43, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.I.; Han, S.H. Non-metric Study of the External Occipital Protuberance for Sex Determination in Koreans: Using Three-dimensional Reconstruction Images. Korean J. Phys. Anthropol. 2015, 28, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, D.; Sayers, M.G. A morphological adaptation? The prevalence of enlarged external occipital protuberance in young adults. J. Anat. 2016, 229, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, T.; Jaouen, A.; Kuchcinski, G.; Badr, S.; Demondion, X.; Cotten, A. Enlarged External Occipital Protuberance in young French individuals’ head CT: Stability in prevalence, size and type between 2011 and 2019. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manaswi, S.; Sanaba, P.N.; Vasudha, K. Torus occipitale and occipital bun: Case series of autapomorphic traits. MRIMS J. Health Sci. 2023, 11, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Porrino, J.; Sunku, P.; Wang, A.; Haims, A.; Richardson, M.L. Exophytic external occipital protuberance Prevalence pre- and post-iPhone introduction: A retrospective cohort. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2021, 94, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macaluso, P.J. Metric sex determination from the basal region of the occipital bone in a documented french sample. Bull. Mém. Soc. Anthropol. 2011, 23, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, D.J.; Moore-Jansen, P.H. Metric variation in the human occipital bone: Forensic anthropological applications. J. Forensic Sci. 2001, 46, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonthai, W.; Kwanyou, A.; Puntawangkoon, S.; Waehama, R.; Poodendaen, C.; Arun, S.; Chaiyamoon, A.; Iamsaard, S.; Duangchit, S. Sexual dimorphism and population-specific sex estimation equations using morphometricanalysis of dry lumbar vertebrae in a Northeastern Thais. Int. J. Morphol. 2024, 42, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonthai, W.; Srisen, K.; Poodendaen, C.; Phetnui, P.; Unsri, S.; Iamsaard, S.; Hazarika, M.; Duangchit, S. Population-specific equations for stature estimation using forearm bones: Insights from Northeastern Thailands diverse ethnic landscape. Anthropol. Anz. 2024, 81, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonthai, W.; Poodendaen, C.; Kamwong, J.; Sangchang, P.; Duangchit, S.; Iamsaard, S. Sex and stature estimations from dry femurs of Northeastern Thais: Using a logistic and linear regression approach. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 38, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putiwat, P.; Srisen, K.; Phetnui, P.; Kamwong, J.; Duangchit, S.; Arun, S.; Iamsaard, S.; Boonthai, W.; Poodendaen, C. Independent validation of sex estimation equations using ulnar dimensions and weight in a northeastern Thai population. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 40, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poodendaen, C.; Klaikran, S.; Maihong, A.; Choompoo, N.; Duangchit, S.; Boonthai, W.; Tangsrisakda, N.; Arun, S.; Chaimontri, C.; Iamsaard, S. Biological sex and stature estimations from dry sternum: A population-specific study in Northeastern Thais. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 11, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poodendaen, C.; Namwongsakool, P.; Iamsaard, S.; Tangsrisakda, N.; Samrid, R.; Chaimontri, C.; Boonthai, W.; Duangchit, S. Stature estimation and sex determination from contemporary Northeastern Thai clavicles using discriminant function and linear regression analyses. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 38, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkban, T.; Iamsaard, S.; Lapyuneyong, N.; Tasu, P.; Poodendaen, C.; Srisen, K.; Boonthai, W.; Duangchit, S. Sex determination by using discriminant function analyses from the Northeastern-Thai occipital bones. Int. J. Morphol. 2024, 42, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangchit, S.; Poodendaen, C.; Phetnui, P.; Tasu, P.; Boonthai, W.; Tangsrisakda, N.; Iamsaard, S. Sex determination and stature estimation using logistic and linear regression models: A population-specific study of tibia and Fibula in Northeastern Thais. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 40, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlayan, F.; Polat, B.; Tugluoglu Dalci, H.L.; Oncu, E.; Kuzey, N.; Guller, H. An Anatomorphometric Study of Occipital Spurs and Their Association with Dental Occlusion. Cureus 2024, 16, e51827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).