The Need for Standardization of Forensic Anthropological Case Reporting Practices in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

| What is your highest degree obtained? | n = 106 High school (0.0%) Associates (AA/AS) (0.0%) Bachelors (BS/BA) (7.5%; n = 8) Master’s (MS/MA) (27.4%; n = 29) PhD (63.2%; n = 67) MD (1.9%; n = 2) |

| How many years of experience do you have? | n = 106 1–2 (9.4%; n = 10) 3–4 (12.3%; n = 13) 5–7 (14.2%; n = 15) 8–10 (12.3%; n = 13) 11–15 (15.1%; n = 16) 16–20 (11.3%; n = 12) 21–25 (12.3%; n = 13) 26–30 (6.6%; n = 7) 31–35 (4.7%; n = 5) 36–40 (0.0%) 41–45 (0.0%) 46–50 (0.9%; n = 1) 51+ (0.9%; n = 1) |

| What is your gender? | Open response (n = 102): Woman (76.5%; n = 78) Man (17.6%; n = 18) Non-binary, agender, or genderqueer (5.9%; n = 6) |

| What is your sex? | Open response (n = 104): Female (81.7%; n = 85) Male (18.3%; n = 19) |

| What is your age? | Open response (n = 99): 23–75 years; 39 years average |

| In what type of context do you work? (Select all that apply) | n = 106 Laboratory (Federal) (10.4%; n = 11) Laboratory (State) (5.7%; n = 6) Medical Examiner’s/Coroner’s office (17.0%; n = 18) Contracting company (3.8%; n = 4) Academia (51.9%; n = 55) Freelance (7.5%; n = 8) Postdoctoral fellow (2.8%; n = 3) Museum (1.9%; n = 2) Other (15.1%; n = 16) N/A—student (18.9%; n = 20) |

| Are you a sole practitioner? | n = 105 Yes (32.4%; n = 34) No (67.6%; n = 71) |

| Do you work in a team-based work environment with other forensic anthropologists? | n = 105 Yes (61.0%; n = 64) No (39.0%; n = 41) |

| Are you certified by the American Board of Forensic Anthropology? | n = 106 Yes (30.2%; n = 32) No (69.8%; n = 74) |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about demographics? | Open response |

3.2. Report Preparation

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

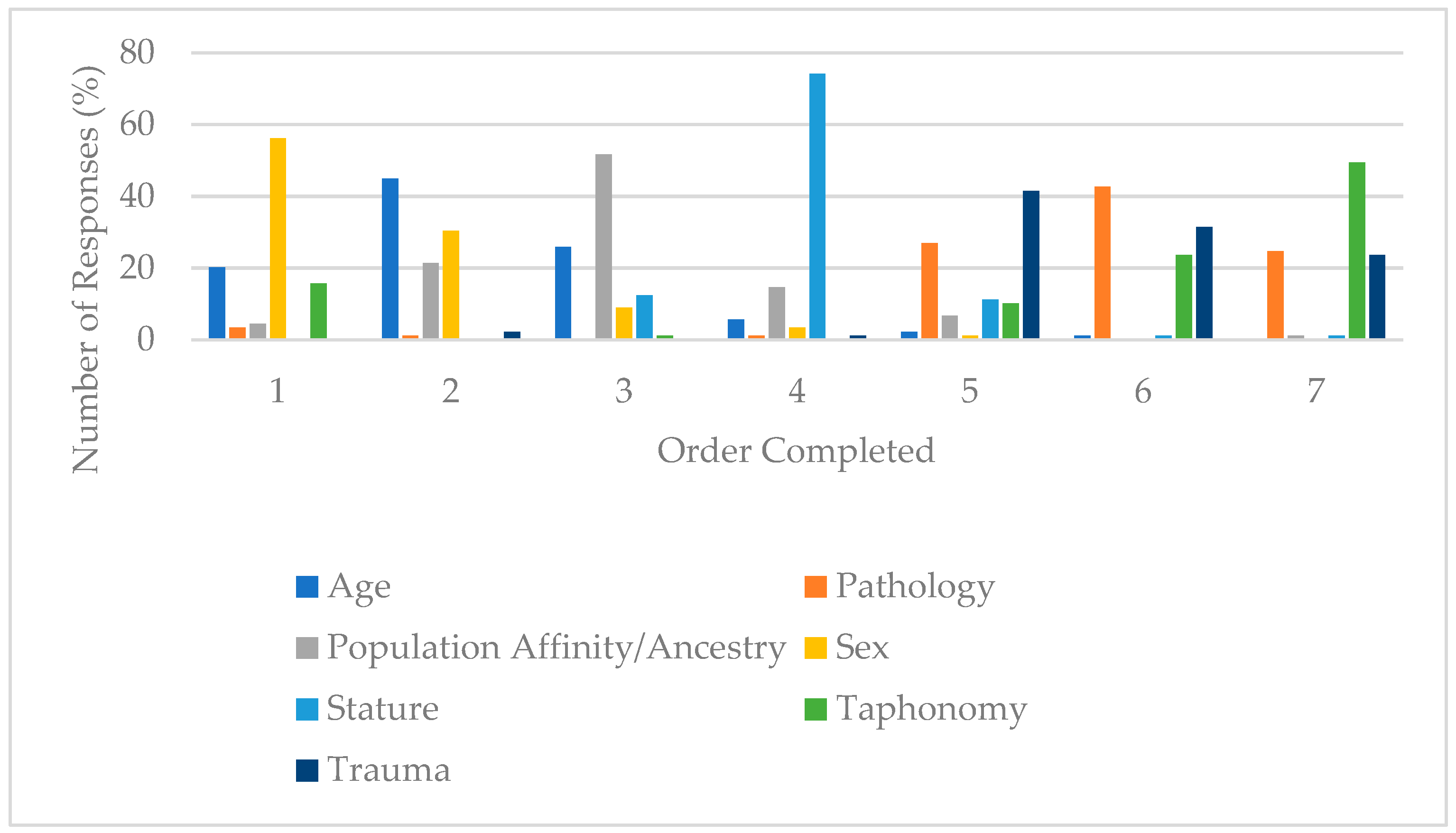

| In what order do you complete the biological profile? | Arrange in order 1–7: Age Pathological analysis Population affinity/ancestry Sex Stature Taphonomic analysis Trauma analysis (see Figure 1) |

| In what order do you organize your case report? | Arrange in order 1–7: Age Pathological analysis Population affinity/ancestry Sex Stature Taphonomic analysis Trauma analysis (see Figure 2) |

| Which of the following terms do you use to refer to the subject of a case report? (Select all that apply) | n = 89 “Individual” (87.6%; n = 78) “Decedent” (56.2%; n = 50) “Specimen” (6.7%; n = 6) “Person” (14.6%; n = 13) “Case” (28.1%; n = 25) Other (fill in) |

| Do you include a skeletal inventory in your case reports? | n = 90 Yes (94.4%; n = 85) No (5.6%; n = 5) |

| Do you include a skeletal homunculus to demonstrate the completeness of remains? | n = 88 Yes (73.9%; n = 65) No (26.1%; n = 23) |

| Do you quantify the completeness of the remains in a case report (using percentages or other numerical representations)? | n = 88 Yes (31.8%; n = 28) No (68.2%; n = 60) Explain |

| How many pages is your typical case report? | n = 86 1–2 (1.2%; n = 1) 3–4 (24.4%; n = 21) 4–5 (27.9%; n = 24) 5–6 (18.6%; n = 16) 6–7 (0.0%) 8–9 (9.3%; n = 8) 10+ (18.6%; n = 16) |

| Do you usually cite peer-reviewed literature in your case reports? | n = 89 Yes (91.0%; n = 81) No (9.0%; n = 8) |

| When conducting skeletal analyses for the biological profile, how often do you have the published methods in front of you? | n = 88 Always (59.1%; n = 52) Frequently (33.0%; n = 29) Sometimes (8.0%; n = 7) Rarely (0.0%) Never (0.0%) |

| Would you cite a book chapter in a case report? | n = 88 Yes (79.5%; n = 70) No (20.5%; n = 18) Explain |

| Would you cite a presentation from a professional meeting in a case report? | n = 88 Yes (28.4%; n = 25) No (71.6%; n = 63) Explain |

| Would you cite an unvalidated method in a case report? | n = 88 Yes (22.7%; n = 20) No (77.3%; n = 68) Explain |

| Do you include an estimation of postmortem interval in your case reports? | n = 88 Yes (55.7%; n = 49) No (44.3%; n = 39) Other (explain) |

| Do you estimate and report on ancestry/population affinity? | n = 88 Yes (80.7%; n = 71) No (1.1%; n = 1) Other (explain) (18.2%; n = 16) |

| Which term do you use for ancestry/population affinity estimation? | n = 89 “Ancestry” (38.2%; n = 34) “Population affinity” (43.8%; n = 39) “Population affiliation” (1.1%; n = 1) “Race” (2.2%; n = 2) N/A (don’t report/discuss) (1.1%; n = 1) Other (explain) (13.5%; n = 12) |

| Do you provide definitions for the above terms? | n = 85 Yes (42.4%; n = 36) No (57.6%; n = 49) |

| Do you use pronouns in case reports to refer to the analyzed individual (e.g., “she/her,” “he/him,” “they/them”?) | n = 87 Yes (10.3%; n = 9) No (89.7%; n = 78) |

| Do you use the terms “feminine” and “masculine” to describe skeletal features for sex estimation? | n = 87 Yes (21.8%; n = 19) No (78.2%; n = 68) |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about report preparation? | Open response |

3.3. Peer Review

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

| Are all your case reports peer reviewed? | n = 82 Yes (75.6%; n = 62) No (24.4%; n = 20) |

| Do you use in-house (internal) peer reviewers for your case reports? | n = 82 Yes (74.4%; n = 61) No (12.2%; n = 10) N/A (13.4%; n = 11) |

| Do you use external peer reviewers (if not at a lab with other anthropologists)? | n = 82 Yes (28.0%; n = 23) No (41.5%; n = 34) N/A (30.5%; n = 25) |

| Do you provide peer reviews for forensic anthropologists at institutions other than your own? | n = 82 Yes (51.2%; n = 42) No (48.8%; n = 40) |

| If you peer review externally (i.e., not in traditional job description), do you charge a fee? | n = 71 Yes (1.4%; n = 1) No (98.6%; n = 70) If yes, how much? |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about peer review? | Open response |

3.4. Cognitive Biasability

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

| Do you believe that forensic anthropologists are objective? | n = 76 Yes (55.3%; n = 42) No (44.7%; n = 34) Explain |

| How objective do you think forensic anthropological reports are? | n = 76 Very objective (18.4%; n = 14) Somewhat objective (48.7%; n = 37) Moderately objective (28.9%; n = 22) Not very objective (3.9%; n = 3) Not objective at all (0.0%) |

| How often do you receive contextual information on a case prior to starting your analysis? | n = 78 Always (14.1%; n = 11) Frequently (30.8%; n = 24) Sometimes (32.1%; n = 25) Rarely (12.8%; n = 10) Never (10.3%; n = 8) |

| Does your place of employment have any bias mitigating procedures? | n = 76 Yes (47.4%; n = 36) No (52.6%; n = 40) Explain |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about cognitive biasability? | Open response |

3.5. Existing Standards

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

| Are you familiar with the Academy Standards Board’s Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Sciences (ASB OSAC) standards for best practice? | n = 83 Yes (88.0%; n = 73) No (12.0%; n = 10) |

| Are you familiar with the Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology (SWGANTH) guidelines? | n = 83 Yes (94.0%; n = 78) No (6.0%; n = 5) |

| How often do you look at and follow the ASB OSAC standards for best practice when completing a case report? | n = 82 Always (14.6%; n = 12) Frequently (26.8%; n = 22) Sometimes (31.7%; n = 26) Rarely (9.8%; n = 8) Never (17.1%; n = 14) |

| How important are the Daubert and Kumho standards in what methods you choose to use? | n = 82 Extremely important (17.1%; n = 14) Very important (40.2%; n = 33) Moderately important (24.4%; n = 20) Slightly important (3.7%; n = 3) Not important at all (14.6%; n = 12) |

| How important are the OSAC and SWGANTH standards in what methods you choose to use? | n = 82 Extremely important (19.5%; n = 16) Very important (34.1%; n = 28) Moderately important (25.6%; n = 21) Slightly important (11.0%; n = 9) Not important at all (9.8%; n = 8) |

| Do you feel that the OSAC standards for best practice provide beneficial standards when completing case reports? | n = 79 Yes (77.2%; n = 61) No (22.8%; n = 18) |

| Does your lab have a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)? | n = 82 Yes (76.8%; n = 63) No (23.2%; n = 19) |

| Do you think that standardization of case reporting across the field of forensic anthropology is important? | n = 80 Yes (71.3%; n = 57) No (28.8%; n = 23) Explain |

| Does your place of work provide standard case reporting guidelines (e.g., report templates, suggested methods)? | n = 82 Yes (72.0%; n = 59) No (28.0%; n = 23) |

| Who do you believe has the responsibility to ensure standardization in the field of forensic anthropology? | n = 80 Professional organizations (e.g., AAFS, ABFA, etc.) (35.0%; n = 28) Individual labs (7.5%; n = 6) Individual practitioners (5.0%; n = 4) ASB/OSAC (26.3%; n = 21) Other (explain) (26.3%; n = 21) |

| The following definition should be considered when answering the next two questions. A universal standard can be defined as something that is followed by and applied to all in a particular group. | No response required |

| Do you believe it is necessary to create a universal standardization in methods and reporting for the field of forensic anthropology? | n = 78 Yes (60.3%; n = 47) No (39.7%; n = 31) |

| If provided a universal standard, would you follow it? | n = 77 Yes (74.0%; n = 57) No (26.0%; n = 20) |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about existing standards? | Open response |

3.6. Education and Training

| Question | Responses/Results |

|---|---|

| Have you ever taken the ABFA certification exam? | n = 81 Yes (37.0%; n = 30) No (63.0%; n = 51) |

| If you have not taken the ABFA exam, why have you not taken it? Select all that apply. | n = 51 Financial constraints (15.7%; n = 8) Time restraints (13.7%; n = 7) Not required for current position (27.5%; n = 14) not interested in joining (7.8%; n = 4) Do not qualify to complete the exam (35.3%; n = 18) Other (please specify) (43.1%; n = 22) |

| Do you think that ABFA certification should be required to be a forensic anthropologist? | n = 79 Yes (50.6%; n = 40) No (49.4%; n = 39) |

| Do you think a PhD should be required to work as a forensic anthropologist? | n = 78 Yes (29.5%; n = 23) No (70.5%; n = 55) |

| What, outside of formal education, did you do to gain experience in forensic anthropology? | Open response |

| How often are you asked to complete a task that you were not taught in traditional educational contexts (e.g., in classroom, laboratory, or field trainings during degree programs or postdoctoral work)? | n = 79 Frequently (24.1%; n = 19) Sometimes (36.7%; n = 29) Rarely (26.6%; n = 21) Never (12.7%; n = 10) |

| Can you provide an example of this task (e.g., postmortem interval estimation, facial approximation, photo superimposition, forensic archaeology)? | Open response |

| How important is archaeological excavation (e.g., body recovery via forensic archaeology) in your current position? | n = 80 Extremely important (31.3%; n = 25) Very important (18.8%; n = 15) Moderately important (22.5%; n = 18) Slightly important (13.8%; n = 11) Not important at all (13.8%; n = 11) |

| In your formal education, were you directly taught how to take osteometric measurements for the biological profile? | n = 79 Yes (93.7%; n = 74) No (6.3%; n = 5) |

| Have you ever mentored an individual wanting to become a forensic anthropologist (formally or informally)? Select all that apply. | n = 80 Yes, formally (65.0%; n = 52) Yes, informally (66.3%; n = 53) No (10.0%; n = 8) |

| Were you mentored in forensic anthropology? Select all that apply. | n = 80 Yes, formally (72.5%; n = 58) Yes, informally (17.5%; n = 14) No (11.3%; n = 9) |

| Do you believe that forensic anthropology education should be formally standardized (e.g., regulated/overseen by a regulatory body)? | n = 76 Yes (67.1%; n = 51) No (32.9%; n = 25) |

| Is there anything else you would like to mention about education and training? | Open response |

4. Discussion

4.1. Participant Demographics

4.2. Report Preparation

4.3. Peer Review

4.4. Cognitive Biasability

4.5. Existing Standards

4.6. Education and Training

4.7. Areas of Opportunity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAFS | American Academy of Forensic Sciences |

| ABFA | American of Forensic Anthropology |

| ANSI/ASB | American National Standards Institute/Academy Standards Board |

| DPAA | Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency |

| FBI | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| NAME | National Association of Medical Examiners |

| OSAC | Organization of Scientific Area Committees |

| PMI | Postmortem Interval |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedure |

| SWGANTH | Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology |

References

- Winburn, A.P.; Tallman, S.D. Forensic Anthropology. In Encyclopedia of Forensic Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.M.; Passalacqua, N.V.; Schmunk, G.A.; Fudenberg, J.; Hartnett, K.; Mitchell, R.A., Jr.; Love, J.C.; DeJong, J.; Petaros, A. The value and availability of forensic anthropological consultation in medicolegal death investigations. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2015, 11, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubelaker, D.H.; Shamlou, A.; Kunkle, A. Contributions of forensic anthropology to positive scientific identification: A critical review. Forensic Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zephro, L.; Galloway, A. Report writing and case documentation in forensic anthropology. In Forensic Anthropology and the United States Judicial System, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, A.M.; Crowder, C.M. Evidentiary Standards for Forensic Anthropology. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579. 1993. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/509/579/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136. 1997. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/522/136/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael, 526 U.S. 137. 1999. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/526/137/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Lesciotto, K.M. The Impact of Daubert on the Admissibility of Forensic Anthropology Expert Testimony. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, B.J.; Byrd, J.E. Interobserver Variation of Selected Postcranial Skeletal Measurements. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.; Boaks, A. How “Standardized” is Standardized? A Validation of Postcranial Landmark Locations. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Vidoli, G. Age-at-Death Estimation: Accuracy and Reliability of Common Age-Reporting Strategies in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Sci. 2023, 3, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, C.R.; Komar, D.A. Kumho, Daubert, and the Nature of Scientific Inquiry: Implications for Forensic Anthropology. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethard, J.D.; DiGangi, E.A. Letter to the Editor—Moving Beyond a Lost Cause: Forensic Anthropology and Ancestry Estimates in the United States. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 1791–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, T.; Crowder, C. “Somewhere in this twilight”: The circumstances leading to the National Academy of Sciences’ report. In Forensic Anthropology and the United States Judicial System, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- SWGANTH. Ancestry Assessment. 2013. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_ancestry_assessment.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- SWGANTH. Proficiency Testing. 2012. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_proficiency_testing.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- SWGANTH. Documentation, Reporting, and Testimony. 2012. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_documentation_reporting_and_testimony.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- SWGANTH. Qualifications. 2010. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_qualifications.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Forensic Anthropology Subcommittee. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science. 2023. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/organization-scientific-area-committees-forensic-science/forensic-anthropology-subcommittee (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- ANSI/ASB Standard 045; Standard for Stature Estimation in Forensic Anthropology. 1–10. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2019.

- ANSI/ASB Standard 090; Standard for Sex Estimation in Forensic Anthropology. 1–9. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2019.

- ANSI/ASB Standard 146; Standard for Resolving Commingled Remains in Forensic Anthropology. 1–11. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2021.

- ANSI/ASB Standard 133; Standard for Age Estimation in Forensic Anthropology. 1–9. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2024.

- ANSI/ASB Standard 147; Standard for Analyzing Skeletal Trauma in Forensic Anthropology. 1–11. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2024.

- ANSI/ASB Standard 148; Standard for Personal Identification in Forensic Anthropology. 1–10. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2024.

- Adams, D.M.; Goldstein, J.Z.; Isa, M.; Kim, J.; Moore, M.K.; Pilloud, M.A.; Tallman, S.D.; Winburn, A.P. A conversation on redefining ethics considerations in forensic anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 2022, 124, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, S.D.; Bird, C.E. Diversity and Inclusion in Forensic Anthropology Where We Stand and Prospects for the Future. Forensic Anthropol. 2022, 5, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, S.D.; Parr, N.M.; Winburn, A.P. Assumed differences, unquestioned typologies: The oversimplification of race and ancestry in forensic anthropology. Forensic Anthropol. 2021, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGangi, E.A.; Bethard, J.D. Uncloaking a Lost Cause: Decolonizing ancestry estimation in the United States. American. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2021, 175, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.H.; Williams, S.E. Ancestry studies in forensic anthropology: Back on the frontier of racism. Biology 2021, 10, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Board of Forensic Anthropology Website. 2025. Available online: https://www.theabfa.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Boyd, D.C.; Bartelink, E.J.; Passalacqua, N.V.; Pokines, J.T.; Tersigni-Tarrant, M. The American Board of Forensic Anthropology’s Certification Program. Forensic Anthropol. 2020, 3, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, N.V.; Pilloud, M.A. Education and Training in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Anthropol. 2020, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s Forensic Anthropology Division. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/ocme/services/forensic-anthropology-unit-technical-manuals.page (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Belcher, W.R.; Shiroma, C.Y.; Chesson, L.A.; Berg, G.E.; Jans, M. The role of forensic anthropological techniques in identifying America’s war dead from past conflicts. WIREs Forensic Sci. 2021, 4, e1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloud, M.A.; Passalacqua, N.V. “Why Are There So Many Women in Forensic Anthropology?”: An Evaluation of Gendered Experiences in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Anthropol. 2022, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, S.D.; George, R.L.; Baide, A.J.; Bouderdaben, F.A.; Craig, A.E.; Garcia, S.S.; Go, M.C.; Goliath, J.R.; Miller, E.; Pilloud, M.A. Barriers to entry and success in forensic anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 2022, 124, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSAC 2024-S-0001; Guidance Document for Understandings and Implementing the Minimal Components of a Quality Assurance Program in Forensic Anthropology Draft. 1–19. AAFS Standards Board: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2024.

- Garvin, H.M.; Passalacqua, N.V. Current practices by forensic anthropologists in adult skeletal age estimation. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Suchey, J.M. Skeletal age determination based on the os pubis: A comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks methods. Hum. Evol. 1990, 5, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buikstra, J.E.; Ubelaker, D.H. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains, 3rd ed.; Arkansas Archaeological Survey: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hefner, J.T. Cranial Nonmetric Variation and Estimating Ancestry. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.T.; Linde, K.C. Atlas of Human Cranial Macromorphoscopic Traits; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 012814386X, 9780128143865. [Google Scholar]

- Işcan, M.Y.; Loth, S.R.; Wright, R.K. Age Estimation from the Rib by Phase Analysis: White Males. J. Forensic Sci. 1984, 29, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işcan, M.Y.; Loth, S.R.; Wright, R.K. Age Estimation from the Rib by Phase Analysis: White Females. J. Forensic Sci. 1985, 30, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, C.O.; Meindl, R.S.; Pryzbeck, T.R.; Mensforth, R.P. Chronological Metamorphosis of the Auricular Surface of the Ilium: A New Method for the Determination of Adult Skeletal Age at Death. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1985, 68, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phenice, T.W. Newly Developed Visual Method of Sexing the Os Pubis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1969, 30, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, N.R.; Jantz, L.M.; Ousley, S.D.; Jantz, R.L.; Milner, G. Data Collection Procedures for Forensic Skeletal Material 2.0.; The University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jantz, R.; Ousley, S. FORDISC 3.1; University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, V.L.; Galloway, A. Broken Bones: Anthropological Analysis of Blunt Force Trauma, 2nd ed.; Charles C. Thomas Publishing: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ortner, D.J. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, C.E.; Bird, J.D.P. Devaluing the Dead: The Role of Stigma in Medicolegal Death Investigations of Long-Term Missing and Unidentified Persons in the United States. In The Marginalized in Death: A Forensic Anthropology of Intersectional Identity in the Modern Era; Byrnes, J.F., Sandoval-Cervantes, I., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2022; pp. 94–117. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Specimen Definition and Meaning. 2024. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/specimen (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Agarwal, S.C. The bioethics of skeletal anatomy collections from India. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanacho, V.; Cardoso, F.A.; Ubelaker, D.H. Documented Skeletal Collections and Their Importance in Forensic Anthropology in the United States. Forensic Sci. 2021, 1, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, N.V.; Pilloud, M.A. The need to professionalize forensic anthropology. Eur. J. Anat. 2021, 25, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tallman, S.D.; Kincer, C.D.; Plemons, E.D. Centering Transgender Individuals in Forensic Anthropology and Expanding Binary Sex Estimation in Casework and Research. Forensic Anthropol. 2022, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.M.; Blatt, S.H.; Flaherty, T.M.; Haug, J.D.; Isa, M.I.; Michael, A.R.; Smith, A.C. Shifting the Forensic Anthropological Paradigm to Incorporate the Transgender and Gender Diverse Community. Humans 2023, 3, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, P.L.; Stockett, M.K. Feminist Anthropology Past, Present, and Future; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; ISBN 0812220056, 9780812220056. [Google Scholar]

- Meloro, R.; Tallman, S.D.; Streed, C.G., Jr.; Stowell, J.T.; Delgado, T.A.; Haug, J.D.; Redgrave, A.; Winburn, A.P. A Framework for Incorporating Diverse Gender Identities into Forensic Anthropology Casework and Theory. Curr. Anthropol. 2025, 66, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.H.; Pilloud, M. The need to incorporate human variation and evolutionary theory in forensic anthropology: A call for reform. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2021, 176, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloud, M.A.; Skipper, C.E.; Horsley, S.L.; Craig, A.; Latham, K.; Clemmons, C.M.J.; Zejdlik, K.; Boehm, D.A.; Philbin, C.S. Terminology Used to Describe Human Variation in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Anthropol. 2021, 4, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.; Craig, A.; Adams, D.M. Language use in ancestry research and estimation. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 66, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, H.R. Ancestry Estimation in Practice: An Evaluation of Forensic Anthropology Reports in the United States. Forensic Anthropol. 2022, 4, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett-McCann, K.; Fulginiti, L.C.; Galloway, A.; Taylor, K.M. The peer review process: Expectations and responsibilities. In Forensic Anthropology and the United States Judicial System, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Winburn, A.P.; Clemmons, C.M.J. Objectivity is a myth that harms the practice and diversity of forensic science. Forensic Sci. Int. Synerg. 2021, 3, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dror, I.E. Cognitive neuroscience in forensic science: Understanding and utilizing the human element. Philos. Trans. B 2015, 370, 20140255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulginiti, L.C. Standing up for forensic science. J. Forensic Sci. 2023, 68, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winburn, A.P. Subjective with a capital S? Issues of objectivity in forensic anthropology. In Forensic Anthropology: Theoretical Framework and Scientific Basis, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nakhaeizadeh, S.; Dror, I.E.; Morgan, R.M. Cognitive bias in forensic anthropology: Visual assessment of skeletal remains is susceptible to confirmation bias. Sci. Justice 2014, 54, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaeizadeh, S.; Hanson, I.; Dozzi, N. The power of contextual effects in forensic anthropology: A study of biasability in the visual interpretations of trauma analysis on skeletal remains. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, T.D.; Tersigni-Tarrant, M.A. Joint POW/MIA Accounting Agency Command/Central Identification Laboratory (JPAC/CIL) History. In Forensic Anthropology: An Introduction, 1st ed.; CRC Press LLC.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M.W.; Friend, A.W.; Stock, M.K. Navigating cognitive bias in forensic anthropology. In Forensic Anthropology: Theoretical Framework and Scientific Basis, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- SWGANTH. Education and Training. 2013. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2018/03/13/swganth_education_and_training.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Pink, C.M.; Cornelison, J.B.; Juarez, J.K. Standardizing Advanced Training in Forensic Anthropology: Defining a Clear Path to Achieve Forensic Specialization in Biological Anthropology. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2025, 186, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilloud, M.A.; Passalacqua, N.V.; Philbin, C.S. Caseloads in forensic anthropology. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2022, 177, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisensee, K.E.; Atwell, M. Human decomposition and time since death: Persistent challenges and future directions of postmortem interval estimation in forensic anthropology. Yearb. Biol. Anthropol. 2025, 186 (Suppl. 78), e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winburn, A.P.; Tallman, S.D.; Scott, A.L.; Bird, C.E. Changing the Mentorship Paradigm Survey Data and Interpretations from Forensic Anthropology Practitioners. Forensic Anthropol. 2022, 5, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, A.; Stoppacher, R. The Forensic Anthropology Report: A Proposed Format Based on the National Association of Medical Examiners Performance Standards. Med. Res. Arch. 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S.; Winburn, A.P. A hierarchy of expert performance as applied to forensic anthropology. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, N.R.; Tersigni-Tarrant, M. Core Competencies in Forensic Anthropology A Framework for Education, Training, and Practice. Forensic Anthropol. 2020, 3, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paradis, A.L.; Tallman, S.D. The Need for Standardization of Forensic Anthropological Case Reporting Practices in the United States. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040071

Paradis AL, Tallman SD. The Need for Standardization of Forensic Anthropological Case Reporting Practices in the United States. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040071

Chicago/Turabian StyleParadis, Alexandra L., and Sean D. Tallman. 2025. "The Need for Standardization of Forensic Anthropological Case Reporting Practices in the United States" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040071

APA StyleParadis, A. L., & Tallman, S. D. (2025). The Need for Standardization of Forensic Anthropological Case Reporting Practices in the United States. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040071