Abstract

Background/Purpose: The study aimed to analyze the dimensions and width-to-length ratios of the maxillary anterior teeth in young native Cambodian adults and to assess their relationship with the golden proportion, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism. Materials and Methods: Maxillary study casts of 193 eligible Cambodian subjects, aged 18 to 25 years, were retrospectively evaluated. The width and length of their maxillary anterior teeth were measured using a digital caliper. Descriptive statistics, independent-samples t-test at 95% confidence intervals, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to analyze the data. Results: There was a high level of similarity between first and second quadrant measurements. Females showed slightly higher standard deviations for central incisors and lateral incisors than males across most ratios, indicating more variability in the width-in-length ratios for females. Males exhibited significantly greater tooth dimensions than females. The following results showed statistical significance with p < 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals. The mean crown width of the central incisors was 8.16 mm in males (CI: 8.03–8.29) and 7.87 mm in females (CI: 7.78–7.96). For the lateral incisors, the mean crown width was 6.69 mm in males (CI: 6.53–6.85) and 7.64 mm in females (CI: 7.43–7.85). The width-to-length ratio of the central incisors was higher in females (mean = 0.88; CI: 0.86–0.91) compared with males (mean = 0.87; CI: 0.84–0.89). Overall, proportional relationships remained consistent across genders. The golden proportion guideline was not applicable, as observed ratios ranged from 0.90 to 1.67 (all below 1.618), and RED values exceeded 80%. The null hypothesis was rejected due to the significant gender differences found in tooth dimensions and width-to-length ratios. Conclusions: There was no significant difference in maxillary anterior tooth dimensions for the right and left sides among the Cambodian population. Males had statistically larger teeth than females. Width-to-length ratios were greater in females for central incisors; however, the proportional relationships between the genders remained relatively consistent. The golden proportion and RED proportions did not exist within this population. A smaller size characterizes Cambodian dentition compared to that of other ethnic groups. Finally, these results can serve as an indicator for planning customized esthetic treatment in Cambodians. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to ensure the representation of the whole Cambodian population.

1. Introduction

Dental esthetics has become a critical factor in the pursuit of esthetic perfection, as it not only influences overall appearance but, with the rise in social media, also heightens awareness of how an individual’s teeth affect social impressions when smiling. Restoring or replacing the esthetic zone remains challenging, as the dimensions and proportions of the maxillary anterior teeth play a crucial role in smile design.

In 1973, Lombardi suggested that the golden proportion (GP) for anterior teeth is 1.618:1, a ratio Levin later applied to esthetic dentistry in 1978 [1,2]. According to this standard, the maxillary lateral incisor (LI) ratio should be 0.618 (62%) of the width of the maxillary central incisor (CI), and the LI should be 0.618 (62%) of the width of the canine (CA) when viewed in a frontal plane. However, in 2001, Ward proposed the idea of recurring esthetic dental (RED) proportion, concluding that a ratio of 0.70 (70%) would display a more pleasing appearance than 0.618 (61.8%). This idea stated that the proportion of the adjacent width of the maxillary teeth should remain constant when viewed from the front as they progress distally from the midline [3]. Following a 2007 survey of North American dentists, he concluded that smiles with a 70% RED proportion for normal-length teeth were preferred over the GP [4]. However, other authors claimed that the GP was not found to exist between the perceived widths of the maxillary anterior tooth dimension [5,6,7,8].

Previous studies have shown sexual dimorphism in CI and CA in both females and males, with CA exhibiting notably greater significant gender-based differences [9,10,11]. Additionally, ethnic, racial, and geographical backgrounds also influence tooth dimensions and proportions. For example, Cinelli et al. reported that Caucasians have a greater width and a higher W/L ratio in the CI than Asians [12]. Thus, these parameters are investigated in various populations. Several authors have revealed differences within the Asian population, with males having wider and longer teeth than females [9,13,14,15,16,17]. Knowing the appearance of different ethnicities and races can aid practitioners with patients’ treatment preferences, especially regarding esthetics. However, only limited data are available for non-Caucasians and many ethnic groups, as much of the existing literature has mostly focused on Western populations. Even with current resources on tooth size differences between genders and among Asian populations, there remains a lack of evidence for the Cambodian population. No reports on the sexual dimorphism in this population may also explain why the GP is applied in only certain groups. Gaining a deeper understanding of their physical tooth morphology would be an advantage as a guideline when practicing in multicultural communities, especially for dentists working in Cambodia, Southeast Asia, or in countries where many Cambodians reside.

The purpose of this research was to analyze the anatomic crown length, width, and proportions of the maxillary permanent anterior tooth groups (CI, LI, and CA) in the young native Cambodian adults. Additionally, the result can provide reference data to assist dentists in determining patients’ ideal natural tooth size. The null hypothesis was that there would be no differences in the mean width, length, and W/L ratio across the three tooth groups by gender. Secondly, it aimed to determine whether their relationships follow the GP and whether symmetry and sexual dimorphism exist within the population. Additionally, an investigation on the prevalence of GP would be performed to evaluate the relationship between Cambodian subjects and Caucasians. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine maxillary anterior tooth proportions in the Cambodian population, therefore filling a gap in the regional literature and contributing to more population-specific guidelines for smile design.

2. Materials and Methods

Maxillary study casts were retrospectively evaluated, and dimensions of anterior maxillary teeth were measured. Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research at the Ministry of Health in Phnom Penh, Cambodia (numbers 164 and 137 NECHR). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Oral and written informed consent were obtained from all participants.

Patients from Roomchang Dental Hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, who fulfilled the following criteria, were included in this research. Of 193 eligible research subjects, 123 were females (63.73%) and 70 (36.27%) were males. A convenience sampling method was employed, as only patients with complete, high-quality study casts and informed consent were included. Random or consecutive selection was not feasible due to the retrospective design and reliance on available clinical records.

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:

- People of Cambodian origin, based on their self-report and documentation, 18–25 years of age, living in Cambodia, and not exclusively from Phnom Penh.

- Missing maxillary posterior tooth/teeth solely for orthodontic treatment purposes.

- No interdental spacing nor crowding between their teeth.

- No restorations or prostheses.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Missing or malformed maxillary anterior teeth.

- Visible wear.

- Established gingivitis and periodontitis, including recession.

2.1. Data Collection

All maxillary impressions were taken and analyzed by board-certified dentists at the Roomchang Dental Hospital in Cambodia. Stainless-steel impression trays (Falcon Medical Italia, Lucca, Italy) with irreversible hydrocolloid material (Aroma Fine Plus Normal Set, GC Showayakuhin Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) were used. They were taken according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Furthermore, all impressions were inspected for defects, including bubbles. They were then disinfected and immediately placed in a plastic bag with a damp napkin.

Subsequently, they were sent to the in-house dental laboratory, where diagnostic study casts were fabricated by a lab technician using white type IV gypsum hard stone within 15 min (THS-S, Taiwan Ying Ko Tzu She Tang Gypsum, Co., New Taipei City, Taiwan). Obvious bubbles on occlusal surfaces were then checked and removed before any gross excess and plaster extensions were trimmed and completely air-dried. No impression defects were found after the fabrication.

2.2. Tooth Dimension Measurements

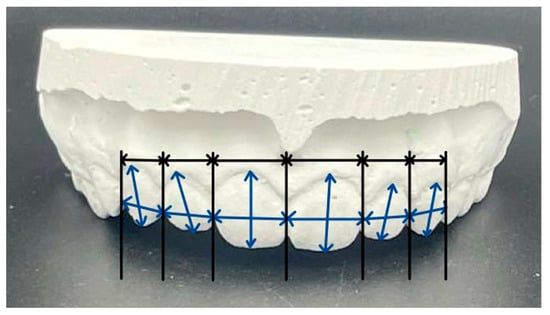

The dimensions of the six maxillary anterior teeth were measured directly on the study model using a digital caliper (RISEMART, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), which had a measuring range of up to 150 mm and was precisely read to the nearest 0.1 mm, with a measurement accuracy of ±0.2 mm. The digital caliper was calibrated by zero-setting and verifying measurement consistency across its range to ensure accuracy before data collection. All measurements were performed by a board-certified orthodontist with over 10 years of working experience. The maximum width dimension of the teeth was obtained by measuring the distance between the tooth’s mesial and distal contact points perpendicular to the long axis. When measuring the crown length, the most apical point of the marginal gingiva to the incisal edge of the tooth was recorded on a line parallel to the long axis of the tooth. An accurate representation of the measurement with one of the participants’ tooth models is shown in Figure 1. All measurements were made of the facial surface of the tooth and recorded in millimeters. All data were recorded using Excel version 16.86 (Microsoft Excel 2023, Microsoft®, Redmond, WA, USA).

Figure 1.

Tooth model representing the measurement. Frontal widths proportion of maxillary anterior measured by connecting vertical lines with perpendicular lines (black). Width and length measurements of the teeth (blue). Source: Photo by author.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 30.0.0.0 (SPSS Statistics, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) for tooth measurement data. Descriptive statistics were used to individually calculate the summary statistics for each tooth dimension for both genders. A comparison of the mean values between the two genders at 95% CI was completed with an independent-samples t-test. A p-value ≥ 0.05 was considered a deviation when the normal distribution was analytically tested for tooth dimensions and proportions using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. A Kruskal-Wallis test was performed on variables that did not meet the normal assumption to assess whether there were statistically significant differences between the tooth groups. Intra- and inter-examiner reliability testing was not performed, as a single examiner conducted all measurements. Multiple testing correction was not applied after the analysis. No correction for multiple testing was applied, as only pre-specified, hypothesis-driven comparisons were conducted, minimizing the potential for Type I error inflation.

3. Results

The gender distribution in this present study was 63.73% females and 36.27% males. There were 123 eligible female and 70 male subjects, totaling 193. The mean age of the female participants was 20.60 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.64 years. As for the male group, the mean was 19.94 with an SD of 2.58. By gender, there was no significant difference in mean age (p > 0.05).

3.1. Tooth Measurements and Ratios

Table 1 presents the mean values, standard deviations (SD), and 95% confidence intervals for the tooth dimensions and ratios by side and gender. It suggested that there was a high level of similarity between the measurements of the right and left teeth. It also revealed that the well-balanced distribution of all the anterior teeth within the male group. In females, mean tooth width ranged from 6.44 mm (LI) to 7.87 mm (CI), while in males, it ranged from 6.69 mm to 8.16 mm. Additionally, it demonstrated that the average tooth length was greater in males than in females. Females showed slightly higher SDs for CI and LI than men across most ratios, suggesting greater variability in W/L ratios. The mean W/L ratio spanned from 0.86 to 0.88 between both genders. There were only minor differences in the means between genders for each tooth ratio, suggesting a similar W/L proportion.

Table 1.

Sample size and mean values (SD) in mm, and 95% confidence intervals of width, length, and width-to-length ratio for each side and both sides of the teeth, by gender, for participating Cambodian subjects.

The normality of the data was assessed using both the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests (p > 0.05). Although the Shapiro–Wilk test is typically recommended for smaller sample sizes (n < 50), it was applied here as an additional check for consistency. Both tests indicated that most data sets followed a normal distribution. A potential deviation from normality was observed in the length of female CA, as indicated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with a p-value of 0.04. Given that this deviation was minimal and the Shapiro–Wilk test produced a comparable result, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied as a conservative follow-up analysis.

3.2. Comparison of Female and Male Samples

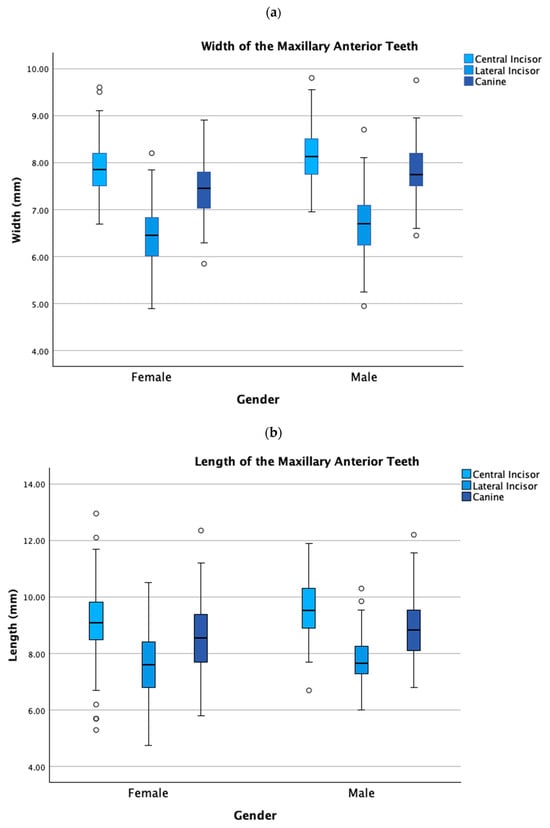

The average measurement and ratio of the teeth were combined into Figure 2, where the width and length of each tooth group were displayed individually. Further interpretation suggested that males generally had larger dimensions for all tooth types, whereas females had a marginally higher W/L proportion in CI. Despite that, the proportional relationships remained relatively stable across genders.

Figure 2.

(a) Width of the maxillary anterior teeth. (b) Length of the maxillary anterior teeth.

The results of independent-samples t-tests comparing the two genders are shown in Table 2, with any significant differences in width, length, and W/L ratio. The crown width of CI, LI, and CA, and the length of CI were significantly different between genders, suggesting that male teeth were, on average, wider and slightly longer in these tooth groups (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found in the length value of LI and CA, as well as CI-W/L, LI-W/L, and CA-W/L (p > 0.05). Collectively, these data points revealed that tooth proportions were similar across genders, despite differences in size.

Table 2.

Independent-samples t-test between genders.

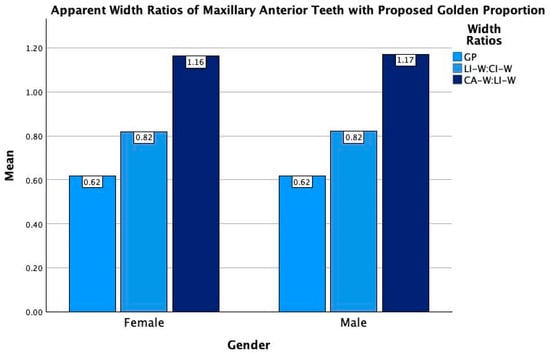

3.3. Golden Proportion and RED

Various ratios among teeth were examined to determine whether a GP and RED relationship existed within the population (Table 3). Every proportional value was below the GP of 1.618, as most were 1.05 and 1.23. Additionally, the width ratios of LI to CI and CA to LI ranged from 0.82 to 1.16, indicating an increase where a proportional decrease was expected. This is shown in Figure 3, where the width-in-width ratio means are displayed separately by gender. In addition, they all exceeded the typical RED standard range of 70–80%. As a result, although none of the tooth sizes in this population strictly adhered to these guidelines, the proportions remained balanced, albeit non-ideal.

Table 3.

Length-in-width, length-in-length, and width-in-width ratios to check for GP and RED relationships.

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing comparison of apparent width ratios of both genders’ maxillary anterior teeth with the proposed golden proportion guideline. GP Golden proportion; LI-W Length-in-width; CI-W Central incisor-in-width; CA-W Canine-in-width.

4. Discussion

The data collected in this study suggested that the CI dimension was the largest among the three maxillary anterior tooth groups. CA followed it while LI presented the smallest size. Comparable studies conducted in the UK, Europe, and Hong Kong have yielded similar results [11,17,18]. Moreover, the right CI teeth in the Cambodian population were slightly larger than the left CI teeth, while the LI and CA were smaller. However, they were not highly significant. This marginal difference could be due to the inconsistent reference points during the tooth measurement. Furthermore, variability in caliper positioning may have introduced systematic measurement errors. To mitigate this, standardized measurement points were established, as outlined. However, the absence of intra-examiner reliability tests may also have contributed to these errors. Of 140 CIs measured on 70 subjects by Mavroskoufis, 86–90% were reported to have neither identical dimensions nor forms [19]. Another study also failed to identify any significant differences after measuring 658 incisors [20].

Compared with studies that used the same measurement method shown in Table 4, the Cambodian population was found to have narrower widths and lengths than those of other populations, except the Southern Chinese. As reported by Magne, the White population displayed the longest and broadest similar tooth size [21]. Regarding W/L ratios, Cambodian teeth demonstrated a similar yet slightly higher ratio, indicating broader teeth relative to their lengths compared to Southern Chinese and Saudi [14,17]. Conversely, they significantly exceeded the lower ratios of European and White populations [21,22]. As a result, this comparison revealed that the Cambodians’ were smaller than those of other ethnicities. These differences may be due to each population’s genetics, environmental influences, racial characteristics, or regional factors exerting a selective influence. The calcification of teeth and the composition of the minerals involved in tooth growth and development are examples of genetic factors, whereas diet, nutrition, radiation, and chemicals are examples of environmental factors [16,23]. Additionally, a study has confirmed that tooth dimensions can be influenced by ethnicity and gender [16]. Therefore, dentists and laboratory technicians should consider ethnicity when designing restorations.

Table 4.

Comparison with existing studies of different racial groups. Measured in mm.

While some authors have noted gender differences in maxillary anterior tooth dimensions, others have reported no statistically significant dimorphism [14,17]. The current study’s findings are mainly consistent with those of Hasanreisoglu et al., who documented sexual dimorphism, indicating that males have greater dental width and length than females in the Turkish population [9]. It showed that their mean width was 0.25–0.34 mm greater than that of the opposite gender, whereas their mean length was 0.12–0.44 mm. Rakhshan et al. also reported sexual dimorphism in their report on the Iranian population, in which males showed larger CI and CA than females [24].

The results of this research did not align with the GP standard, as they fell below the proportional value of 1.618. Investigations by other studies also revealed that GP relationships did not exist among many other ethnic groups, such as the Irish, Malaysians, and Turks [5,9,10]. Additionally, the present study did not strictly adhere to the RED standard either, as the LI and CI widths were smaller than the CA and LI, respectively. The tooth groups were slightly wider than the RED standard’s proportional guidelines, which expected the proportional value to decrease. Furthermore, Magne et al. observed that strict adherence to these two principles could result in anterior teeth with an unnaturally narrow appearance and inadequate visibility of posterior teeth. Therefore, while these proportions can create an esthetically pleasing smile, they should be applied in a flexible and judicious manner to enhance the natural harmony of different populations’ dental ratios [21,22]. In this case, this standard might serve only as a guide and cannot be expected to represent a natural look among young Cambodians, despite their wishes.

In summary, this study provides valuable insights into the dimensions and proportions of maxillary anterior teeth among young Cambodian adults, highlighting gender differences and deviations from common esthetic ratios. Understanding these specific tooth dimensions and proportions can help dentists and lab technicians base their references on the local population, rather than relying on esthetic norms from neighboring or Western countries. This approach may enable them to achieve a more natural-looking smile for their Cambodian patients, whether they are seeking treatment in orthodontics, restorative, cosmetic, or implant dentistry. Moreover, the findings offer practical value for digital dentistry by advancing personalization of CAD/CAM-based smile design workflows and contributing to the development of population-specific esthetic guidelines.

Limitations

This study’s small, non-representative sample and gender imbalance limit generalizability and statistical power, especially regarding sexual dimorphism. Reliance on study casts may have restricted impression control and omitted potentially relevant clinical information. Future research should integrate 3D digital measurement and intra-oral scanning across multiple centers to achieve more precise and reliable dental assessments. Since the research was conducted at a single center, its findings may restrict the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Additionally, the study’s sample size and type only describe tooth measurements but fail to demonstrate Cambodian golden esthetic standards. These limitations highlight the need for larger, more diverse samples and advanced digital methods to obtain more comprehensive, evidence-based insights in dental research. Multicenter, digitally integrated studies are essential for developing population-specific esthetic guidelines.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, no significant difference in maxillary anterior tooth dimensions was found between the right and left quadrants. Males showed larger tooth measurements than females, confirming sexual dimorphism within this population. Furthermore, Cambodians’ teeth were smaller than those of other ethnicities. The GP guidelines and RED proportions were not applicable to either gender, suggesting that universal esthetic ratios may not be suitable for this population. These findings highlight the need for establishing population-specific esthetic guidelines to support more accurate clinical evaluation and smile design.

Finally, these results can serve as an indicator for planning customized esthetic treatment in Cambodians, especially prosthetics. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine if age, tooth shape, gingival shape and its thickness, or arch shape also influence gender-related findings in the esthetic zone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and B.S.; Methodology, A.T. and B.S.; Validation, A.O. and B.S.; Formal Analysis, A.O. and B.S.; Investigation, V.P. and H.Y.T.; Resources, V.P. and H.Y.T.; Data Curation, A.O. and A.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.T., B.S., A.O., V.P. and H.Y.T.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.S. and C.v.S.; Visualization, A.T.; Supervision, C.v.S.; Project Administration, C.v.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research of the Ministry of Health in Phnom Penh, Cambodia (No. 164 NECHR on 26 May 2023 and 137 NECHR on 11 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to Roomchang Dental Hospital, for supporting this study by providing with all the study casts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Veasna Phit and Hong You Tith were employed by the hospital Roomchang Dental Hospital. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CA | Canine |

| CI | Central incisor |

| GP | Golden proportion |

| LI | Lateral incisor |

| RED | Recurring esthetic dental |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| W/L | Width-to-length ratio |

References

- Lombardi, R.E. The Principles of Visual Perception and Their Clinical Application to Denture Esthetics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1973, 29, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.I. Dental Esthetics and the Golden Proportion. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1978, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, D.H. Proportional Smile Design Using the Recurring Esthetic Dental (Red) Proportion. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 45, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.H. A Study of Dentists’ Preferred Maxillary Anterior Tooth Width Proportions: Comparing the Recurring Esthetic Dental Proportion to Other Mathematical and Naturally Occurring Proportions. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2007, 19, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marzok, M.I.; Majeed, K.R.A.; Ibrahim, I.K. Evaluation of Maxillary Anterior Teeth and Their Relation to the Golden Proportion in Malaysian Population. BMC Oral Health 2013, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, H.; Köseoğlu, M.; Bayindir, F. An Investigation of the Esthetic Indicators of Maxillary Anterior Teeth in Young Turkish People. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallala, R.; Gassara, Y.; Garrach, B.; Touzi, S.; Harzallah, B. The Assessment of Golden and Red Proportions among a North-African Population. Tunis. Med. 2023, 101, 899–902. [Google Scholar]

- Pursnani, R.A.; Saxena, A.; Parihar, A.; Chauhan, S.P.; Verma, N.; Pushparekha, G. Comparing the Existence of Golden Proportion Using Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions in Primary and Permanent Dentition: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 17, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanreisoglu, U.; Berksun, S.; Aras, K.; Arslan, I. An Analysis of Maxillary Anterior Teeth: Facial and Dental Proportions. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005, 94, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, M.; Bready, M.; Quinn, F.; O’Connell, B.C.; Houston, F.J.; O’Sullivan, M. Maxillary Anterior Tooth Dimensions and Proportions in an Irish Young Adult Population: MAX TOOTH IRISH POPULATION. J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, T.B.; Beyuo, F.; Wilson, N.H.F. Upper Anterior Tooth Dimensions in a Young-Adult Indian Population in the UK: Implications for Aesthetic Dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 223, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, F.; Piva, F.; Bertini, F.; Russo, D.S.; Giachetti, L. Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions and Relative Width Proportions: A Narrative Literature Review. Dent. J. 2023, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiyama, T.; Marcushamer, E.; Griffin, T.J.; Arguello, E.; Magne, P.; Gallucci, G.O. Comparison of the Anatomic Crown Width/Length Ratios of Unworn and Worn Maxillary Teeth in Asian and White Subjects. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2012, 107, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, S.K.; Zhang, H.D.; Chang, T.; Dhungana, M.; Acharya, L.; Chen, L.L.; Ding, Y.M. Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions and Proportions in a Central Mainland Chinese Population. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 17, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sandeep, N.; Satwalekar, P.; Srinivas, S.; Reddy, C.S.; Reddy, G.R.; Reddy, B.A. An Analysis of Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions for the Existence of Golden Proportion: Clinical Study. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, C. Evaluation of Influence Factors on the Width, Length, and Width to Length Ratio of the Maxillary Central Incisor: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.Y.; Millar, B.J. Biometric Assessment of Maxillary Anterior Tooth Dimensions in a Hong Kong SAR Population. Open J. Stomatol. 2022, 12, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Varo, A.; Arroyo-Cruz, G.; Martínez-de-Fuentes, R.; Jiménez-Castellanos, E. Biometric Analysis of the Clinical Crown and the Width/Length Ratio in the Maxillary Anterior Region. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 113, 565–570.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroskoufis, F.; Ritchie, G.M. Variation in Size and Form between Left and Right Maxillary Central Incisor Teeth. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1980, 43, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, S.M.; Lewis, A.B.; Kerewsky, R.S. Sex Difference in Tooth Size. J. Dent. Res. 1964, 43, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, P.; Gallucci, G.O.; Belser, U.C. Anatomic Crown Width/Length Ratios of Unworn and Worn Maxillary Teeth in White Subjects. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Habib, S.R.; Ali, M.; Alshahrani, A.S.; Alotaibi, N.M.; Alahaidib, F.A. Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimension and Relative Width Proportion in a Saudi Subpopulation. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Halim, M.S.; Khalid, S.; Ghani, Z.A.; Jamayet, N.B. Evaluation of Golden Percentage in Natural Maxillary Anterior Teeth Width: A Systematic Review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 845.e1–845.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshan, V.; Ghorbanyjavadpour, F.; Ashoori, N. Buccolingual and Mesiodistal Dimensions of the Permanent Teeth, Their Diagnostic Value for Sex Identification, and Bolton Indices. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8381436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).