Abstract

Background/Objectives: Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) is associated with gingival recession and dentin exposure. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite (HAp) reduces DH by occluding dentinal tubules, with conventional toothpaste formulations showing benefits. High-density HAp mouthwashes may enhance bioavailability, but comparative evidence is scarce. This trial assessed the immediate desensitizing efficacy of a conventional HAp toothpaste and a high-density HAp mouthwash after professional oral hygiene. Methods: One hundred participants were randomized 1:1 to Biorepair® (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) Total Protection Toothpaste (Control) or Biorepair® (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) High-Density Mouthwash (Test). Assessments were performed at baseline (T0), post-debridement (T1), and after product use (T2). The primary endpoint was patient-level Schiff Air Index (SAI). Secondary endpoints included tooth-level SAI, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores, and gingival recession (GR). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07057141) and followed CONSORT 2025 guidelines. Friedman and Dunn’s tests and regression models were applied. Results: Both groups showed significant reductions in hypersensitivity. Patient-level mean SAI decreased from 1.47 to 0.66 in the Control and from 1.48 to 0.45 in the Test group, while VAS declined from 3.66 to 1.57 (Control) and from 4.15 to 1.37 (Test). Post hoc analyses showed significant intragroup reductions between T0/T1 and T2 in both groups, with no significant differences between groups at any timepoint. GR remained stable across the study. Regression analyses identified follow-up time and GR as significant predictors, whereas treatment allocation was not, indicating that the acute advantage of the mouthwash at T2 did not persist once longitudinal trends were considered. Conclusions: Both HAp formulations effectively reduced dentin hypersensitivity 30 s after application. The high-density mouthwash exhibited slightly lower mean values at T2, although these differences were not statistically significant.

1. Introduction

Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) is a common clinical condition characterized by a short, sharp pain arising from exposed dentin in response to thermal, tactile, osmotic, or evaporative stimuli, which cannot be attributed to any other form of dental pathology [1]. Its prevalence in the adult population has been reported to range between 10% and 30%, with higher incidence among patients presenting with gingival recession, non-carious cervical lesions, and periodontal disease [2]. The exposure of dentinal tubules due to loss of enamel or cementum is the primary etiological factor, with the hydrodynamic theory being the most widely accepted explanation of the underlying mechanism [3]. According to this theory, external stimuli cause fluid movement within dentinal tubules, activating pulpal mechanoreceptors and eliciting pain [4,5].

Over the years, numerous therapeutic strategies have been proposed to manage DH, including in-office and at-home treatments [6,7,8,9]. Among the latter, toothpastes and mouthrinses containing active agents such as potassium salts, fluoride, arginine, and biomimetic hydroxyapatite (HAp) have gained widespread popularity [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. HAp-based products, in particular, have attracted considerable attention because of their biomimetic composition, which closely resembles the mineral phase of human enamel and dentin [21,22]. Their ability to occlude exposed dentinal tubules and promote remineralization suggests a promising role in reducing hypersensitivity.

In recent years, the term “biomimetic hydroxyapatite” has been increasingly used in dental literature, although not always with scientific accuracy. In dentistry, biomimetic should be reserved for hydroxyapatite (HAp) formulations specifically engineered to reproduce the key physicochemical, crystallographic, and nanostructural characteristics of biological enamel and dentin. True biomimetic HAp consists of nano-sized crystals (<100 nm) with low crystallinity and carbonate substitution, parameters that replicate the ultra-structure and chemical composition of native dental apatite and mimic the physiological processes that govern enamel remineralization [14,21,23,24,25]. Owing to this structural similarity, biomimetic HAp exhibits high bioaffinity for dental tissues: it can integrate into the acquired pellicle, form a mineralized surface layer, and achieve deep, stable occlusion of exposed dentinal tubules, resulting in measurable reductions in dentinal hypersensitivity [26,27,28,29,30,31].

This definition highlights a crucial distinction: not all hydroxyapatites included in toothpastes can be considered biomimetic. Standard formulations generally contain micro-sized or highly crystalline HAp particles, which primarily exert a mechanical tubule-plugging effect without replicating the interfacial and molecular interactions typical of enamel-like remineralization [32,33,34,35,36]. In contrast, biomimetic nano-HAp interacts with enamel and dentin at a deeper level, promoting the formation of a stable, enamel-like mineral phase, with superior intratubular sealing and longer-lasting clinical effects.

Products containing microRepair® (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) represent an example of scientifically valid biomimetic hydroxyapatite technology. These formulations rely on microcrystalline zinc-substituted hydroxyapatite (Zn-HAp), an engineered HAp in which ionic substitutions enhance bioactivity, affinity for dentin proteins, and integration with the existing mineral matrix, thereby more closely reproducing the behavior of physiological hydroxyapatite [14,23]. Its mechanism of action is immediate and physical: following professional debridement, Zn-HAp selectively adheres to clean exposed dentin and rapidly occludes dentinal tubules, reducing fluid flow according to the hydrodynamic theory of pain [3,4,14].

For these reasons, the designation “biomimetic hydroxyapatite toothpaste” is scientifically justified for engineered Zn-HAp-based products such as microRepair® (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) yet should not be applied to formulations that merely include generic hydroxyapatite without biomimetic design. This conceptual clarity is essential for accurately interpreting mechanisms of action and anticipating clinical outcomes among different hydroxyapatite-based products [10,21,23].

Several clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of HAp-containing toothpastes in alleviating DH, reporting encouraging improvements in subjective pain scores and objective sensitivity indices [10,11,37,38,39]. More recently, mouthrinse formulations containing HAp have been introduced as alternatives or adjuncts to toothpaste [40,41]. High-density HAp mouthwashes are of particular interest: these formulations contain elevated concentrations of zinc-HAp microcrystals suspended in a more viscous vehicle, designed to increase retention on the tooth surface and enhance immediate tubule occlusion. However, while toothpastes have been extensively investigated, few well-designed randomized clinical trials have evaluated the immediate desensitizing effect of high-density HAp mouthwashes in comparison with biomimetic HAp toothpastes [11,37,42]. Additionally, the immediate impact of professional oral hygiene procedures—such as scaling and biofilm removal—on gingival recession and sensitivity perception remains underexplored, despite evidence that these procedures can transiently modify gingival margin position and hypersensitivity outcomes [43]. Another potentially influential but understudied factor is the severity of gingival recession, which may affect DH indices such as the Schiff Air Index (SAI) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [44,45].

In light of these gaps, the present randomized controlled clinical trial aimed to verify whether the desensitizing activity of biomimetic HAp—already documented in the medium and long term by previous studies [8,39]—could also manifest in the very short term, namely 30 s application. To this end, we evaluated and compared the immediate effects of a biomimetic HAp toothpaste (Control group) and a biomimetic high-density HAp mouthwash (Test group) on dentin hypersensitivity immediately after a standardized session of professional oral hygiene.

The primary null hypothesis was that no significant difference exists between the two interventions in terms of patient-level change in SAI across baseline (T0), post-hygiene (T1), and post-treatment (T2). Secondary null hypotheses were that no differences would be observed between groups at the tooth-level SAI and for VAS at both patient and tooth levels, and that the severity of GR would not significantly influence hypersensitivity scores.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

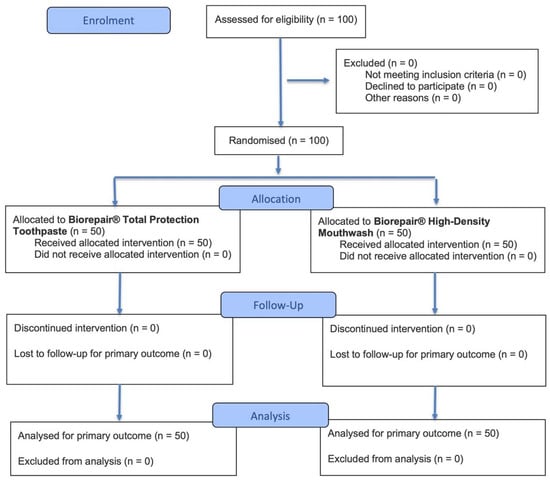

This was a prospective, single-center, randomized controlled clinical trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio, conducted between June 2024 and July 2025, approved by the Unit Internal Review Board (approval number: 2024-0703; approval date: 3 July 2024) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07057141). The research adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for studies involving human participants and complied with the CONSORT 2025 checklist criteria [46] (see Supplementary Table S1). All individuals provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Both the treatment procedures and the evaluation of outcomes were performed at the same clinical facility. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT 2025 [46] flowchart summarizing participant enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis.

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2025 flow diagram.

2.2. Study Setting

This clinical investigation was carried out at the Dental Hygiene Unit, Section of Dentistry, Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Pediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants eligible for the study were men and women aged between 18 and 70 years, in good general health (ASA I or II), who provided written informed consent. These criteria were defined based on methodological recommendations for dentin hypersensitivity trials, with the aim of minimizing systemic or pharmacological influences on pain perception and ensuring diagnostic consistency [47]. Inclusion required the presence of gingival recession (GR), clinically diagnosed by visible root exposure and confirmed by periodontal probing as a distance between the gingival margin and the cementoenamel junction ≥ 1 mm [48]. Moreover, participants needed to present dentin hypersensitivity, confirmed by a positive response to evaporative stimulus using the Schiff Air Index (SAI) and self-reported pain on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [49].

Exclusion criteria included individuals younger than 18 years of age, those with current or recent (<4 weeks) use of desensitizing toothpastes or mouthrinses [11], and pregnant or breastfeeding women, in order to avoid ethical concerns and hormonal-related changes that could affect dentin hypersensitivity outcomes [50]. Additional exclusion criteria were known allergy to product components; chronic use (≥3 months) of medications that may alter pain perception, such as long-term analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, or anti-inflammatory drugs [51]; the presence of untreated carious lesions or structural fractures of enamel and/or dentin in teeth affected by hypersensitivity, as these conditions could act as confounding factors [52]; and the presence of uncontrolled systemic diseases, including poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, active autoimmune or immune-mediated disorders, or ongoing malignant diseases, which may interfere with oral health, pain perception, or study safety [53].

The determination and application of the eligibility criteria followed a standardized three-step screening procedure. First, each participant’s electronic medical records were reviewed to verify general health status, ASA classification, chronic medication use, pregnancy or breastfeeding status, and the presence of systemic conditions relevant to exclusion. Second, a structured medical and dental questionnaire was administered to identify recent use of desensitizing products, allergies, pain-modulating medications, and lifestyle factors potentially influencing dentin hypersensitivity. Finally, a direct clinical examination was performed by a calibrated operator to confirm gingival recession, visible root exposure, and dentin hypersensitivity using SAI and VAS testing. This multi-layered approach ensured consistent, reproducible, and clinically reliable application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Interventions and Outcomes

After signing the informed consent document (baseline, T0), the following clinical parameters were recorded by an instructed operator: GR (distance between gingival margin and cementoenamel junction, expressed in millimeters), measured with a periodontal probe (UNC probe 15; Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) [48]; SAI (hypersensitivity assessment in response to a one-second air blast delivered from a dental syringe at approximately 1 cm from the gingival margin, scored on a scale of 0–3), evaluated on both the buccal and lingual/palatal surfaces of the affected teeth [49]; and VAS (self-reported pain intensity on a 10 cm horizontal line ranging from 0 = no pain to 10 = worst possible pain) [53]. At the tooth level, GR and SAI were measured for each individual tooth showing gingival recession and dentin hypersensitivity, while VAS scores were collected for each tooth immediately after the air stimulus. At the patient level, mean values of GR, SAI, and VAS were calculated by averaging the results obtained from all examined teeth of each patient.

Immediately after these baseline assessments, patients underwent professional supragingival oral hygiene treatment, performed using a piezoelectric instrument (Multipiezo, Mectron S.p.a., Carasco, Italy) and Gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA), followed by decontamination with glycine powder (Mectron S.p.a., Carasco, Italy).

After completion of the professional hygiene session (T1), GR, SAI, and VAS were reassessed at both the tooth and patient levels, since professional debridement may induce immediate variations in gingival margin position due to the removal of inflamed tissues and biofilm, as well as transient changes in dentin hypersensitivity perception. This additional recording ensured standardized baseline conditions before treatment allocation. In this way, it was possible to evaluate the difference in sensitivity after product application, considering the sensitivity measurement taken after professional oral hygiene as a negative control and thus assessing the changes observed following the application of the two products [54]. Subsequently, patients were randomly assigned to one of the two study groups. The Control group applied Biorepair® Total Protection toothpaste (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) on hypersensitive areas for 30 s, while the Test group rinsed with Biorepair® High-Density mouthwash (Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy) for 30 s. Table 1 shows the compositions of the two products used.

Table 1.

Composition of the tested products.

After the intervention (T2), clinical parameters were recorded again at both the tooth and patient levels in order to assess the effect of the treatments on dentin hypersensitivity.

The primary objective was to evaluate the change in dentin hypersensitivity—quantified by SAI patient level—across T0, T1, and T2 between the two groups. Secondary objectives were the same comparison for SAI at the tooth level and for VAS at both the patient and tooth levels, as well as to investigate whether the severity of gingival recession influenced SAI and VAS scores.

2.5. Sample Size

The determination of the required number of participants was performed considering two independent parallel groups and a continuous primary outcome, with a significance threshold set at α = 0.05 and a statistical power of 95%.

The sample size was estimated using the following formula:

where Z is the standard normal variate corresponding to 1.96 at 5% type 1 error, p is the expected proportion of the population expressed as a decimal and based on previous studies, and finally d is the confidence level determined by the researcher and expressed as a decimal, too.

The variable Schiff Air Index at patient level was chosen as the primary outcome. A mean of 2.72 was expected, and a difference between the means of 0.23, with a standard deviation of 0.32 [55]. Therefore, 50 patients per group were required for this clinical study.

2.6. Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly allocated to the Control or Test group with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The randomization sequence was generated using R software (version 4.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) through a computer-based algorithm to ensure equal probability of assignment. Allocation was performed by an independent operator not involved in data collection, and the assigned intervention was communicated to the clinical examiner immediately before treatment.

2.7. Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all clinical variables at both the tooth level and the patient level. Specifically, for gingival recession (GR), Schiff Air Index (SAI), and Visual Analog Scale (VAS), the following values were reported: mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, median, and maximum.

For inferential analysis, the Friedman test was applied to evaluate differences across timepoints (T0, T1, T2) within each group. When statistically significant results were detected, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s post hoc test to identify specific differences between time frames. A letter-based grouping method was used to facilitate the interpretation of statistically significant differences across comparisons [56].

In addition, linear regression models were performed to explore potential associations between gingival recession, hypersensitivity indices (SAI and VAS), treatment groups, and time in order to assess whether the severity of gingival recession or other covariates influenced dentin hypersensitivity outcomes.

All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Recruitment

A total of 100 patients were assessed for eligibility, all of whom met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate. Consequently, 100 participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into two groups: 50 were allocated to the Biorepair® Total Protection Toothpaste (Control group) and 50 to the Biorepair® High-Density Mouthwash group (Test group). All participants received the allocated intervention, with no losses to follow-up or discontinuations throughout the study period. Recruitment was conducted at the Dental Hygiene Unit, Section of Dentistry, University of Pavia, Italy, between June 2024 and July 2025. Therefore, all 100 patients were included in the final analysis, ensuring full adherence to the study protocol. Importantly, no adverse events or harms related to the use of either the toothpaste or the mouthwash were reported during the study period.

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the baseline demographic characteristics of the study participants and the distribution of examined teeth in both groups. The overall mean age was 51.3 ± 16.0 years (range 22–70), with males slightly older on average (54.1 ± 15.7) compared to females (48.4 ± 16.1). The gender distribution was balanced, with 51% males and 49% females. When stratified by treatment allocation, the Control and Test groups showed nearly identical demographic profiles, with mean ages of 51.6 ± 16.1 and 51.0 ± 15.9 years, respectively, and a comparable gender distribution (52% males in the Control group and 50% males in the Test group). None of the participants were current smokers, and no systemic conditions or medications known to affect periodontal health were reported, thereby minimizing potential confounding factors.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Regarding tooth position, the percentages are calculated out of a total of 80 teeth in each group. Each participant contributed between 1 and 3 teeth to the analysis in both groups, reflecting the variability in the number of eligible recession sites per patient. In the Control group, 46.3% of teeth were maxillary (n = 37) and 53.8% mandibular (n = 43), with a relatively even distribution across the four quadrants, ranging from 17.5% in quadrant 2 to 31.3% in quadrant 4. In the Test group, 41.3% of teeth were maxillary (n = 33) and 58.8% mandibular (n = 47). The quadrant distribution showed a slightly higher proportion of teeth in quadrant 4 (37.5%) compared with the other quadrants, which ranged from 20.0% to 21.3%.

3.3. Outcomes

3.3.1. Gingival Recession (GR)

At both the tooth level and the patient level, mean GR values remained stable across all study timepoints (T0, T1, T2) in both groups. In the Control group, mean GR was consistently 2.95 mm at the tooth level (95% CI: 2.39–3.51) and 3.04 mm at the patient level (95% CI: 2.46–3.62), with no detectable changes immediately after professional oral hygiene or after product application. Similarly, in the Test group, mean GR values were stable at 2.65 mm (95% CI: 2.15–3.15) at the tooth level and 2.80 mm (95% CI: 2.29–3.31) at the patient level throughout the entire observation period. Median values and ranges also confirmed the absence of variation between baseline, post-hygiene, and post-treatment assessments. Inferential analysis with the Friedman test confirmed these descriptive findings. No statistically significant differences were detected in GR values across timepoints within either group. At the tooth level, the Friedman statistic was 6.639 with an approximate p-value of 0.249, while at the patient level, the Friedman statistic was 3.378 with an approximate p-value of 0.642. Therefore, Dunn’s post hoc test was not performed. These results are illustrated in Table 3, which reports descriptive statistics and intra- and intergroup comparisons of GR values at both tooth level and patient level across all timepoints (T0–T2) in the Control and Test groups.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and intragroup/intergroup comparisons of GR tooth-level and patient-level values across all timepoints (T0–T2) in the Control and Test groups. Superscript letters indicate the results of multiple comparisons: lowercase letters denote intragroup differences across timepoints (T0–T2), while uppercase letters denote intergroup differences (Control vs. Test) at each corresponding timepoint. Means sharing at least one identical letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

3.3.2. Schiff Air Index (SAI)

Analysis of SAI values revealed a progressive and significant intragroup reduction over time in both study arms, as detailed in Table 4. At both the tooth level and the patient level, the Control and Test groups showed a similar pattern: SAI values at T2 were significantly lower than at T0 and T1, whereas no significant differences were detected between T0 and T1. This intragroup trend is reflected in Table 4 by the change in lowercase superscript letters (from a at T0–T1 to b at T2).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and intragroup/intergroup comparisons of SAI tooth-level and patient-level values across all timepoints (T0–T2) in the Control and Test groups. Superscript letters indicate the results of multiple comparisons: lowercase letters denote intragroup differences across timepoints (T0–T2), while uppercase letters denote intergroup differences (Control vs. Test) at each corresponding timepoint. Means sharing at least one identical letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

At the tooth level, the Control group showed a decrease in mean SAI from 1.42 (95% CI: 1.18–1.66) at baseline to 1.20 (95% CI: 0.92–1.48) after professional oral hygiene and to 0.58 (95% CI: 0.34–0.82) at T2. The same pattern was observed at the patient level (1.47 → 1.26 → 0.66). The Test group exhibited an analogous reduction, with tooth-level values decreasing from 1.42 (95% CI: 1.17–1.67) to 1.28 (95% CI: 1.01–1.55) and then to 0.42 (95% CI: 0.17–0.67), and patient-level values from 1.48 → 1.31 → 0.45.

Inferential analyses confirmed these patterns. The Friedman test showed significant changes over time (tooth-level χ2 = 165.5, p < 0.0001; patient-level χ2 = 108.6, p < 0.0001), and post hoc Dunn’s tests indicated that the significant pairwise differences occurred between T0 and T2 and between T1 and T2 in both groups, with no significant differences between T0 and T1.

Crucially, no intergroup differences were detected at any timepoint, as indicated in Table 4 by identical uppercase superscript letters between the Control and Test groups (A at T0 and T1; B at T2). Thus, although both interventions led to significant improvements over time, their effects were comparable at all evaluated timepoints.

3.3.3. Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

VAS values demonstrated a clear and progressive reduction in dentinal hypersensitivity over time within each study group, as detailed in Table 5. At both the tooth level and the patient level, the Control and Test groups showed significant intragroup improvements, with VAS scores at T2 being significantly lower than those recorded at T0 and T1. No significant differences were observed between T0 and T1 in either group, as reflected by the identical lowercase superscript letters (a at both timepoints).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and intragroup/intergroup comparisons of VAS tooth-level and patient-level values across all timepoints (T0–T2) in the Control and Test groups. Superscript letters indicate the results of multiple comparisons: lowercase letters denote intragroup differences across timepoints (T0–T2), while uppercase letters denote intergroup differences (Control vs. Test) at each corresponding timepoint. Means sharing at least one identical letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

At the tooth level, the Control group showed a decrease in mean VAS from 3.78 (95% CI: 2.95–4.61) at baseline to 3.24 (95% CI: 2.37–4.11) after professional oral hygiene, reaching 1.50 (95% CI: 0.87–2.13) at T2. Similarly, patient-level values declined from 3.66 (95% CI: 2.95–4.37) to 3.16 (95% CI: 2.37–3.95) and then to 1.57 (95% CI: 0.93–2.21).

The Test group exhibited the same pattern of improvement, with tooth-level VAS values decreasing from 4.10 (95% CI: 3.38–4.82) at baseline to 3.83 (95% CI: 3.08–4.58) after hygiene and to 1.35 (95% CI: 0.61–2.09) at T2. Patient-level scores similarly fell from 4.15 (95% CI: 3.46–4.84) to 3.71 (95% CI: 2.97–4.45) and then to 1.37 (95% CI: 0.71–2.03).

Inferential statistics supported these descriptive findings. The Friedman test showed highly significant reductions across timepoints (tooth-level χ2 = 168.1, p < 0.0001; patient-level χ2 = 105.8, p < 0.0001). Post hoc Dunn’s analyses confirmed significant intragroup reductions between T0 and T2 and between T1 and T2 in both groups, with no significant differences between T0 and T1.

Importantly, no intergroup differences were observed at any timepoint, as indicated in Table 5 by the identical uppercase superscript letters (A at T0–T1 and B at T2 for both groups). Thus, although both groups showed substantial and comparable reductions in dentinal hypersensitivity over time, neither treatment demonstrated superiority over the other at any evaluation point.

3.3.4. Regression Analysis

Linear regression models were applied to evaluate predictors of dentin hypersensitivity. Gingival recession (GR) emerged as a significant factor for both outcomes. For SAI, greater recession was associated with higher hypersensitivity scores (β = 0.105, SE = 0.024, t = 4.32, p < 0.001). Similarly, GR showed a positive association with VAS (β = 0.244, SE = 0.073, t = 3.36, p = 0.001), indicating that increased recession corresponded to greater self-reported pain. Follow-up time was also identified as a significant predictor. SAI values decreased progressively across timepoints (β = –0.467, SE = 0.041, t = –11.33, p < 0.001), reflecting clinical improvement. VAS scores showed a similar pattern (β = –0.146, SE = 0.014, t = –10.35, p < 0.001), confirming reduction in pain perception over the course of the study. In contrast, treatment group allocation (toothpaste vs. mouthwash) did not significantly influence outcomes. For SAI, the estimate was β = –0.042 (SE = 0.074, t = –0.57, p = 0.571), while for VAS it was β = 0.254 (SE = 0.219, t = 1.16, p = 0.247). These findings indicate that the improvements observed over time were independent of the assigned intervention. These outcomes are detailed in Table 6, which reports the significant linear regression models for clinical outcomes.

Table 6.

Significant linear regression models for clinical outcomes.

4. Discussion

The present randomized clinical trial investigated the immediate desensitizing efficacy of two biomimetic HAp formulations—a conventional toothpaste (Control) and a high-density mouthwash (Test)—following professional oral hygiene.

The primary null hypothesis, stating that no differences would exist between groups in patient-level SAI across T0, T1, and T2, was not rejected. Both groups demonstrated significant reductions in hypersensitivity over time, as shown by the significant intragroup changes from T0/T1 to T2. However, post hoc analyses revealed no significant differences between the two groups at any timepoint, including T2, as indicated by the identical uppercase superscript letters in Table 4. Although the Test group showed slightly lower mean values at T2, this difference was not statistically significant. Regression models were consistent with these findings, as treatment allocation did not emerge as an independent predictor of SAI once all timepoints and covariates were incorporated, indicating that improvements were driven primarily by time and gingival recession rather than by differences between formulations.

The secondary null hypotheses, which stated that no differences would be observed between groups for tooth-level SAI and VAS at both tooth and patient levels, were likewise not rejected. Both tooth-level and patient-level hypersensitivity scores (SAI and VAS) decreased significantly over time in both groups, but no intergroup differences were detected at any timepoint, confirming that the desensitizing effect was comparable between the two formulations. GR values remained stable across all timepoints, confirming that neither intervention modified the extent of root exposure during the single-session evaluation period. This stability is consistent with the physiological and methodological constraints of the present trial: all GR measurements were obtained minutes apart within a single appointment using a UNC-15 probe with 1 mm precision. Under these conditions, sub-millimetric shifts cannot be detected once measurements are rounded to whole millimeters. This interpretation aligns with contemporary periodontal literature, which indicates that detectable gingival margin changes occur over days to weeks during healing after scaling and root planing, rather than immediately after supragingival debridement [2,48,54]. To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have demonstrated within-appointment GR changes following professional supragingival hygiene alone.

However, regression models identified GR as an independent predictor of both SAI and VAS, with greater recession associated with higher hypersensitivity and pain perception, consistent with the established etiological role of root exposure in DH [2,48,54]. Taken together, these findings indicate that although both formulations rapidly reduced hypersensitivity, their effects did not differ significantly between groups. The small, non-significant numerical advantage observed in the Test group at T2 does not represent a true between-group separation and is not sustained when all timepoints and covariates are modeled simultaneously.

In the acute setting, the rapid intragroup desensitizing effect observed in this trial is biologically plausible and supported by mechanistic evidence. Both tested formulations contain zinc-substituted biomimetic hydroxyapatite (HAp, microRepair®—Coswell S.p.A., Funo, BO, Italy), which exerts an immediate physical action on exposed dentin. Following professional debridement, the dentin surface is clean, reactive, and highly permeable, facilitating the adsorption of HAp microcrystals and the rapid formation of a mineral-rich biomimetic layer that seals tubule entrances. This early occlusion reduces dentinal fluid movement according to the hydrodynamic theory, producing fast improvements in hypersensitivity scores. SEM and permeability studies have shown that HAp-containing formulations can block tubules and repair superficial mineral loss after short contact times [57], while clinical evidence confirms measurable reductions in hypersensitivity immediately or shortly after application of biomimetic HAp products [58]. A recent review further supports the capacity of zinc-HAp to integrate rapidly with both enamel and dentin and promote early mineral deposition [14].

These mechanistic insights help explain the marked intragroup reductions observed at T2. They do not, however, imply a significant difference between formulations, which was not supported by the statistical findings of the present trial.

The present results are coherent with the available literature and extend it by (i) demonstrating immediate, chairside reductions in hypersensitivity with both HAp formulations and (ii) confirming the predictive role of GR for both SAI and VAS outcomes. Meta-analytic evidence has shown that HAp-containing products consistently reduce dentin hypersensitivity compared with placebo (mean relative reduction 39.5%, 95% CI 48.93–30.06) and fluoride (23%, 95% CI 34.18–11.82), with a non-significant trend toward superiority over other desensitizing agents [10]. These findings align with RCTs documenting clinically significant decreases in hypersensitivity with nano-HAp dentifrices compared to fluoride or calcium sodium phosphosilicate [38,59]. The association between GR and DH is also supported by clinical and epidemiological evidence, as teeth with exposed root surfaces show higher sensitivity levels [2,48], and etiological models emphasize that gingival tissue loss exposes patent dentinal tubules that exacerbate pain [54].

Randomized clinical trials further corroborate these patterns. Amaechi et al. [38] demonstrated significant reductions across stimuli over 8 weeks with nano-HAp toothpastes, comparable to CSPS controls. Polyakova et al. [11] reported measurable benefits by 2 weeks and more robust effects by 4 weeks, while Vlasova et al. [55] observed progressive Schiff score decreases at 3, 7, and 14 days. Scribante et al. [18] further confirmed the clinical effectiveness of HAp-based dentifrices in pediatric patients, demonstrating significant remineralizing and desensitizing effects. These data collectively mirror the improvements observed in the present trial and confirm the desensitizing efficacy of HAp across formulations and time scales.

Importantly, previous studies assessing HAp toothpaste typically report intergroup separation after days or weeks of use [11,38]. The present trial differs in focusing on immediate, within-session effects and demonstrates that such rapid improvements occur with both formulations, but without significant differences between them. The liquid vehicle of the mouthwash may facilitate HAp deposition and rapid tubule interaction [60,61,62,63,64,65], but in this trial, it did not produce a statistically significant advantage over toothpaste in the acute timeframe.

These results parallel broader findings from mouthrinse literature. Potassium-salt rinses have demonstrated significant DH reductions over 2–8 weeks [41], and oxalate- and nitrate-based rinses have shown measurable improvements in Schiff and VAS scores compared with placebo or brushing alone [65,66]. Our findings—rapid improvement after a single application of both formulations—are compatible with this rationale, suggesting that contact with an active desensitizing agent immediately after scaling exerts a rapid physical effect on exposed tubules.

Head-to-head comparisons with fluoride dentifrices further support this interpretation. Butera et al. [67] reported that patients with white-spot lesions treated with HAp toothpaste experienced greater reductions in SAI and VAS than those treated with 1450 ppm fluoride at 30 and 90 days, with significant improvements already detectable by day 30. Naim et al. [37] confirmed that HAp-based RCTs often require several weeks of use to reveal between-group differences. In contrast, the present trial demonstrates that although a brief 30 s exposure is sufficient to produce meaningful intragroup reductions, it does not generate detectable intergroup differences in the acute phase.

Regression analyses further clarified the determinants of hypersensitivity reduction. GR consistently emerged as a key predictor, with greater recession associated with higher SAI and VAS scores, in line with previous evidence [2,48,54]. Assessment timepoint was another significant factor, as both SAI and VAS progressively decreased throughout the session, reflecting the combined effect of professional debridement and HAp application. In contrast, treatment allocation did not significantly influence outcomes in the regression models, indicating that overall improvements were driven by time and the extent of root exposure rather than by differences between toothpaste and mouthwash formulations.

Limitations are the short follow-up restricted to acute effects, the single-session evaluation period that does not allow the detection of potential delayed or cumulative adverse effects, a single-center design limiting external validity, the absence of an active comparator beyond HAp, and unmeasured covariates (e.g., diet, salivary flow, hygiene habits) that may influence DH. Moreover, because the same clinician performed both the interventions and all real-time assessments, evaluator blinding was not feasible, introducing a potential risk of examiner or performance bias. Although allocation concealment was ensured, neither operator blinding nor evaluator blinding could be implemented. Consequently, all clinical outcomes were assessed by the same clinician who performed the interventions, which may introduce additional examiner or performance bias. Furthermore, the eligibility criteria were intentionally defined without minimum or maximum thresholds for GR, SAI, or VAS in order to include a clinically representative spectrum of hypersensitivity severity rather than restricting the sample to predefined intensity levels. The exclusion of participants with untreated carious lesions, enamel or dentin fractures, or defective tooth structures was aimed at preventing confounding conditions that could mimic hypersensitivity or alter baseline pain perception, thus contributing to a more homogeneous sample and reducing variability in pain responses. Additionally, all clinical measurements were performed by the same trained operator to minimize inter-operator variability; however, this methodological choice, together with the distinct application modalities of the two products, further contributed to the impossibility of implementing operator and evaluator blinding, representing a relevant limitation of the study design. GR management was beyond the scope, though confirmed as an independent predictor. Finally, a further limitation is the absence of a non-HAp control arm, which would have allowed comparison not only between HAp formulations but also against standard hygiene products without active biomimetic components.

Future research should extend follow-up to confirm the persistence of the immediate desensitizing effects observed, incorporate longer-term monitoring to assess potential late-onset side effects, include multicenter trials, test HAp directly against fluoride and potassium-based comparators, and employ mechanistic approaches such as imaging or biochemical analyses to clarify tubule occlusion dynamics. Additionally, future studies should evaluate whether combining Hap-based treatments with adjunctive products such as toothpaste and mouthrinse formulations provides synergistic or longer-lasting desensitizing effects. Such investigations would consolidate the role of HAp in DH management and help define treatment strategies tailored to patient-specific profiles, particularly gingival recession severity.

5. Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial demonstrated a rapid and significant desensitizing effect of biomimetic HAp formulations, with marked reductions in SAI and VAS already evident 30 s after product application (T2). Both the toothpaste and the high-density mouthwash produced comparable and progressive improvements, and intragroup analyses confirmed significant reductions from T0/T1 to T2 in both groups. Importantly, no significant differences were observed between the two formulations at any timepoint, indicating that the desensitizing effect was independent of the delivery vehicle. Regression models further supported this finding, as treatment allocation was not identified as an independent predictor of hypersensitivity. Gingival recession remained stable throughout the session, confirming that neither protocol altered soft-tissue conditions in the short term. Clinically, these findings support the use of both HAp-based toothpaste and HAp-based mouthwash for immediate relief of dentin hypersensitivity. Since the two formulations demonstrated similar performance, clinicians may base their choice on patient preference, ease of use, or adjunctive indications rather than on differences in efficacy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oral5040100/s1, Table S1: CONSORT 2025 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., M.P. and A.B.; methodology, A.S., M.P. and A.B.; software, A.S. and M.P.; validation, A.S., M.P., A.C., S.C. and A.B.; formal analysis, A.S. and M.P.; investigation, S.C. and A.B.; resources, A.S. and A.B.; data curation, A.S., M.P. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and A.B.; visualization, A.S., M.P., A.C., S.C. and A.B.; supervision, A.S. and A.B.; project administration, A.S., M.P., and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Unit Internal Review Board (approval number: 2024-0703) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT07057141). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects involved signed the informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CONSORT | Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials |

| DH | Dentin Hypersensitivity |

| GR | Gingival Recession |

| HAp | Hydroxyapatite |

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trial |

| SAI | Schiff Air Index |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Dionysopoulos, D.; Gerasimidou, O.; Beltes, C. Dentin hypersensitivity: Etiology, diagnosis and contemporary therapeutic approaches—A review in literature. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katirci, G.; Celik, E.U. The prevalence and predictive factors of dentine hypersensitivity among adults in Turkey. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayan, G.; Misilli, T.; Buldur, M. Home-use agents in the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: Clinical effectiveness evaluation with different measurement methods. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Bakri, M.M.; Yahya, F.; Ando, H.; Unno, S.; Kitagawa, J. The role of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in the transduction of dental pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contac, L.R.; Pop, S.I.; Bica, C.I. Enhancing pediatric comfort: A comprehensive approach to managing molar-incisor hypomineralization with preemptive analgesia and behavioral strategies. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Scardina, G.A.; Pezzullo, S.; Scribante, A. Home oral care domiciliary protocol for the management of dental erosion in rugby players: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, M.; Shetty, B.; Fazal, I.; Khan, S.F.; Shah, M.A.; Kamath, V.; Faruk, S.; Jalaj, V.; N, N.S. Effectiveness of two wavelengths of diode laser and amorphous calcium phosphate-casein phosphopeptide mousse in the treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity: A randomized clinical study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 1257136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosco, V.; Vitiello, F.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Gatto, M.L.; Orilisi, G.; Mengucci, P.; Putignano, A.; Orsini, G. Assessment of the remineralizing potential of biomimetic materials on early artificial caries lesions after 28 days: An in vitro study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Romeo, M.; Reda, M.; Zampetti, P.; Paduano, S.; Scribante, A. Dentin Hypersensitivity Treated with Diode Laser and Aminefluoride: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Dent. 2025, 2025, 1399815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limeback, H.; Enax, J.; Meyer, F. Clinical evidence of biomimetic hydroxyapatite in oral care products for reducing dentin hypersensitivity: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Doroshina, V.; Arakelyan, M.; Novozhilova, N.; Babina, K. The effect of toothpastes containing hydroxyapatite, fluoroapatite, and Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite nanocrystals on dentin hypersensitivity: A randomized clinical trial. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipour, H.S.; Bagheri, H.; Babazadeh, S.; Khorshid, M.; Shooshtari, Z.; Shahri, A. Evaluation and comparison of the effects of a new paste containing 8% L-arginine and CaCO3 plus KNO3 on dentinal tubules occlusion and dental sensitivity: A randomized, triple blinded clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.C.; Riva, J.J.; Firmino, R.T.; Schünemann, H.J. Formulations of desensitizing toothpastes for dentin hypersensitivity: A scoping review. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2022, 30, e20210410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Carolina, M.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Quintini, M.; Lelli, M.; Tarterini, F.; Foltran, I.; Scribante, A. Biomimetic action of zinc hydroxyapatite on remineralization of enamel and dentin: A review. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, A.N.P.; Kelesoglu, E.; Sagır, K.; Kargul, B. Remineralization potential of a novel varnish: An in vitro comparative evaluation. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldur, B.; Taskaya, B. Clinical effectiveness and parental acceptance of silver diamine fluoride in preschool children: A non-randomized trial. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonguc-Altin, K.; Selvi-Kuvvetli, S.; Topcuoglu, N.; Kulekci, G. Antibacterial effects of dentifrices against Streptococcus mutans in children: A comparative in vitro study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribante, A.; Pascadopoli, M.; Bergomi, P.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L.; Bizzi, F.M.; Butera, A. Evaluation of two different remineralising toothpastes in children with drug-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis: A randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 25, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- AlQhtani, F.A.B.A.; Abdulla, A.M.; Kamran, M.A.; Luddin, N.; Abdelrahim, R.K.; Samran, A.; AlJefri, G.H.; Niazi, F.H. Effect of adding sodium fluoride and nano-hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to the universal adhesive on bond strength and microleakage on caries-affected primary molars. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Castro, B.; Flores-Ledesma, A.; Rubio-Rosas, E.; Teutle-Coyotecatl, B.; Flores-Ferreyra, B.I.; Argueta-Figueroa, L.; Moyaho-Bernal, M.L.A. Comparison of the physical properties of glass ionomer modified with silver phosphate/hydroxyapatite or titanium dioxide nanoparticles: In vitro study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, C.; Gayathri, V.S.; Sowmya, S.V.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Albar, N.H.M.; Bhandi, S. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: A comprehensive review. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathaiah, S.; Maganur, P.C.; Syed, A.A.; Kakti, A.; Hussain Jaafari, A.H.; Albar, D.H.; Renugalakshmi, A.; Jeevanandan, G.; Khurshid, Z.; Ali Baeshen, H.; et al. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) in arresting coronal dental caries in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossù, M.; Saccucci, M.; Salucci, A.; Di Giorgio, G.; Bruni, E.; Uccelletti, D.; Sarto, M.S.; Familiari, G.; Relucenti, M.; Polimeni, A. Enamel remineralization and repair results of biomimetic hydroxyapatite toothpaste on deciduous teeth: An effective option to fluoride toothpaste. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschoppe, P.; Zandim, D.L.; Martus, P.; Kielbassa, A.M. Enamel and dentine remineralization by nano-hydroxyapatite toothpastes. J. Dent. 2011, 39, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarup, J.S.; Rao, A. Enamel surface remineralization: Using synthetic nanohydroxyapatite. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2012, 3, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglar, S.; Erdem, U.; Dogan, M.; Turkoz, M. Dentinal tubule occluding capability of nano-hydroxyapatite: An in-vitro evaluation. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2018, 81, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunam, D.; Manimaran, S.; Sampath, V.; Sekar, M. Evaluation of dentinal tubule occlusion and depth of penetration of nano-hydroxyapatite derived from chicken eggshell powder with and without sodium fluoride: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2016, 19, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, I.; Chauhan, S.; Amaranath, B.J.J.; Das, N.; Johnson, L.; Mehrotra, V. Effect of commercially available nano-hydroxyapatite containing desensitizing toothpaste and mouthwash on dentinal tubular occlusion: A SEM analysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2023, 15 (Suppl. S2), S1027–S1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C.; Tan, S. Nano hydroxyapatite–silica with a core-shell structure for long-term management of dentin hypersensitivity. iScience 2024, 27, 111474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schestakow, A.; Lefering, G.J.; Hannig, M. An ultrastructural in-situ study on the impact of desensitizing agents on dentin. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, M.; Majidinia, S.; Bagheri, H.; Hoseinzadeh, M. The effect of formulated dentin-remineralizing gel containing hydroxyapatite, fluoride, and bioactive glass on dentin microhardness: An in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 4788668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepla, E.; Besharat, L.K.; Palaia, G.; Tenore, G.; Migliau, G. Nanohydroxyapatite and its applications in preventive, restorative and regenerative dentistry: A review of literature. Ann. Stomatol. 2014, 5, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, N.M.; John, J.; Nagappan, N.; Prabhu, S.; Kumar, E.S. Evaluation of dentifrice containing nano-hydroxyapatite for dentinal hypersensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bologa, E.; Stoleriu, S.; Iovan, G.; Ghiorghe, C.A.; Nica, I.; Andrian, S.; Amza, O.E. Effects of dentifrices containing nanohydroxyapatite on dentinal tubule occlusion: A scanning electron microscopy and EDX study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, A.; Ibraheem, W.I.; Meshni, A.A.; Preethanath, R.S.; Anil, S. Nano-hydroxyapatite in the remineralization of early dental caries: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntavee, A.; Juntavee, N.; Hirunmoon, P. Remineralization potential of nanohydroxyapatite toothpaste compared with tricalcium phosphate and fluoride toothpaste on artificial carious lesions. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 5588832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, J.; Sen, S. The remineralizing and desensitizing potential of hydroxyapatite in dentistry: A narrative review of recent clinical evidence. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, B.T.; Lemke, K.C.; Saha, S.; Luong, M.N.; Gelfond, J. Clinical efficacy of nanohydroxyapatite-containing toothpaste at relieving dentin hypersensitivity: An 8 weeks randomized control trial. BDJ Open 2021, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, S.; Zwanzig, K.; Doenges, H.; Kuchenbecker, J.; Meyer, F.; Enax, J. Daily application of a toothpaste with biomimetic hydroxyapatite and its subjective impact on dentin hypersensitivity, tooth smoothness, tooth whitening, gum bleeding, and feeling of freshness. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, B.; Pebbili, K.K.; Shukla, K. Potassium oxalate-based mouth rinse for rapid relief in dentinal hypersensitivity. J. Oral Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.; Deschamps Muniz, R.P.; Almeida Lago, M.C.; da Silva Júnior, E.P.; Braz, R. Clinical efficacy of mouthwashes with potassium salts in the treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oper. Dent. 2023, 48, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarpour, M.; Jafari, S.; Rafiee, A.; Alizadeh, M.; Vossoughi, M. Protective effect of various toothpastes and mouthwashes against erosive and abrasive challenge on eroded dentin: An in vitro study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, M.; Alshail, F.; Alqahtani, S.H.; Aloriny, T.S.; Alsharif, A.; Kujan, O. Short-term effects of scaling and root planing with or without adjunctive use of an essential-oil-based mouthwash in the treatment of periodontal inflammation in smokers. Interv. Med. Appl. Sci. 2015, 7, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olley, R.C.; Wilson, R.; Moazzez, R.; Bartlett, D. Validation of a cumulative hypersensitivity index (CHI) for dentine hypersensitivity severity. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzinadah, S.H.; Alhaddad, A.J. A randomized clinical trial of dentin hypersensitivity reduction over one month after a single topical application of comparable materials. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 69, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto, Y.; Horibe, M.; Inagaki, Y.; Oishi, K.; Tamaki, N.; Ito, H.O.; Nagata, T. Association of gingival recession and other factors with the presence of dentin hypersensitivity. Odontology 2014, 102, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Oh, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.S. A randomized clinical trial for comparing the efficacy of desensitizing toothpastes on the relief of dentin hypersensitivity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, R.L. Protected from harm, harmed by protection: Ethical consequences of the exclusion of pregnant participants from clinical trials. Res. Ethics 2023, 19, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.; Parkinson, C.P.; Davies, M.; Claydon, N.C.A.; West, N.X. Randomised clinical trial to evaluate changes in dentine tubule occlusion following 4 weeks use of an occluding toothpaste. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majji, P.; Murthy, K.R. Clinical efficacy of four interventions in the reduction of dentinal hypersensitivity: A 2-month study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2016, 27, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.C.B.; Oliveira, L.; Silva, J.A.B.; Santos, W.B.B.; Ferreira, L.R.S.L.; Guiraldo, R.D.; Vilhena, F.V.; D’Alpino, P.H.P. Effectiveness of bioactive toothpastes against dentin hypersensitivity using evaporative and tactile analyses: A randomized clinical trial. Oral 2024, 4, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X.; Tenenbaum, H.C.; Wilder, R.S.; Quock, R.; Hewlett, E.R.; Ren, Y.F. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity: An evidence-based overview for dental practitioners. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, N.; Samusenkov, V.; Novikova, I.; Nikolenko, D.; Nikolashvili, N.; Gor, I.; Danilina, A. Clinical efficacy of hydroxyapatite toothpaste containing polyol germanium complex (PGC) with threonine in the treatment of dentine hypersensitivity. Saudi Dent. J. 2022, 34, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H. An algorithm for a letter-based representation of all-pairwise comparisons. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2004, 13, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, M.; Putignano, A.; Marchetti, M.; Foltran, I.; Mangani, F.; Procaccini, M.; Roveri, N.; Orsini, G. Remineralization and repair of enamel surface by biomimetic Zn–carbonate hydroxyapatite containing toothpaste: A comparative in vivo study. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, G.; Procaccini, M.; Manzoli, L.; Giuliodori, F.; Lorenzini, A.; Putignano, A. A double-blind randomized-controlled trial comparing the desensitizing efficacy of a new dentifrice containing carbonate/hydroxyapatite nanocrystals and a sodium fluoride/potassium nitrate dentifrice. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.L.; Zheng, G.; Lin, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.D.; Han, J.M. Network meta-analysis on the effect of desensitizing toothpastes on dentine hypersensitivity. J. Dent. 2019, 88, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannig, C.; Basche, S.; Burghardt, T.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Hannig, M. Influence of a mouthwash containing hydroxyapatite microclusters on bacterial adherence in situ. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, M.; Marchisio, O.; Foltran, I.; Genovesi, A.; Montebugnoli, G.; Marcaccio, M.; Covani, U.; Roveri, N. Different corrosive effects on hydroxyapatite nanocrystals and amine fluoride-based mouthwashes on dental titanium brackets: A comparative in vitro study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, S.A.; Salama, R.I. Antiplaque and remineralizing effects of Biorepair mouthwash: A comparative clinical trial. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2016, 26, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosola, S.; Marconcini, S.; Giammarinaro, E.; Marchisio, O.; Lelli, M.; Roveri, N.; Genovesi, A.M. Antimicrobial efficacy of mouthwashes containing zinc-substituted nanohydroxyapatite and zinc L-pyrrolidone carboxylate on suture threads after surgical procedures. J. Oral Sci. Rehabil. 2017, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Peetsch, A.; Epple, M. Characterization of the solid components of three desensitizing toothpastes and a mouthwash. Mater. Werkst. 2011, 42, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.C.; Perfekt, R.; McGuire, J.A.; Milleman, J.; Gallob, J.; Amini, P.; Milleman, K. Potassium oxalate mouthrinse reduces dentinal hypersensitivity: A randomized controlled clinical study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.; Sufi, F.; Milleman, J.L.; Milleman, K.R. Efficacy of a 3% potassium nitrate mouthrinse for the relief of dentinal hypersensitivity: An 8-week randomized controlled study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Montasser, M.A.; Abd El Latief, M.H.; Modica, G.G.; Scribante, A. Home oral care with biomimetic hydroxyapatite vs. conventional fluoridated toothpaste for the remineralization and desensitizing of white spot lesions: Randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).