Abstract

Background: Periapical surgery is indicated for persistent periapical lesions that do not respond to conventional endodontic therapy, yet postoperative recovery is often hindered by pain, swelling, and delayed healing. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes are autologous biomaterials with regenerative potential, capable of modulating inflammation and promoting tissue repair. Methods: This preliminary randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of PRF membranes in improving postoperative outcomes—specifically pain, swelling, and quality of life—after apicoectomy. Twenty patients requiring periapical surgery were randomly allocated to a PRF group (n = 10) or a control group (n = 10). In the PRF group, autologous PRF membranes were applied over the resected root-end and into the osteotomy cavity before flap closure. In the control group, no PRF membranes or any additional biomaterial were applied, apart from the standard root-end filling material (MTA), which was identically used in both groups as part of the routine apicoectomy protocol. All patients were blinded to allocation, and outcomes were assessed by an independent blinded evaluator. Facial swelling was quantified by 3D facial scanning, pain was recorded daily using a visual analog scale (VAS), and quality of life was evaluated with the PROMIS-29+2 Profile. Results: The PRF group showed significantly reduced swelling (mean volume difference, 7.12 cm3; p = 0.025), lower pain scores (VAS: 1.80 ± 1.22 vs. 3.80 ± 2.44; p = 0.034), and improved quality-of-life domains, including higher Physical Function (p = 0.032) and lower Sleep Disturbance (p = 0.008) scores. Conclusions: Within the limitations of this pilot study, PRF membranes enhanced postoperative recovery after periapical surgery by reducing swelling and pain while improving patient-reported outcomes. Larger multicenter trials are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

1. Background

Periapical surgery is crucial for treating chronic periapical infections and lesions that do not respond to conventional endodontic therapy [1,2]. In the first few days after surgery, patients often experience significant pain, inflammation, and edema. Although these are short-term problems, they can cause significant discomfort, highlighting the need for innovative techniques to alleviate these symptoms and improve overall recovery and quality of life [3,4]. These challenges highlight the need for further investigation of novel methodologies that can improve short-term surgical outcomes. Such methodologies have been linked to faster recovery, reduced postoperative pain, less swelling, and enhanced wound healing in postoperative examinations of pain and edema, both of which have considerable impacts on patient comfort and recuperation [4,5,6].

One promising advancement in regenerative dentistry is the use of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) [7]. This autologous biomaterial, derived from a given patient’s blood, contains a variety of growth factors and cytokines that facilitate the processes of tissue regeneration and healing [8]. PRF functions as a scaffold, stimulating cell proliferation and angiogenesis and reducing inflammation [9,10,11]. Its application in periapical surgery has been documented in [12,13]. Numerous studies have revealed PRF’s efficacy in enhancing bone healing and tissue regeneration at surgical sites, thereby establishing its value as an adjunct in complex dental and maxillofacial surgeries [14,15,16,17].

Despite these promising findings [15], more comprehensive clinical evidence is needed to ascertain the efficacy of PRF in periapical surgery. Studies have highlighted that more robust data are required in order to validate the benefits of PRF across a range of clinical scenarios, particularly in relation to its potential for alleviating postoperative pain and swelling, which are primary concerns for patients undergoing periapical surgery [3,18,19].

Therefore, the primary objective of this preliminary single-blind randomized controlled trial was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes in enhancing postoperative recovery after periapical surgery. The study focused on key outcomes, including facial swelling, pain intensity, and patient-reported quality of life, to provide evidence on the potential of PRF to improve healing and comfort in endodontic microsurgery.

The null hypothesis of this randomized clinical trial was that the application of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes would not result in any significant difference in postoperative pain, swelling, or healing outcomes compared with the control group.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The aim of this preliminary randomized controlled clinical trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of PRF membranes in enhancing postoperative recovery following an apicoectomy. The study was conducted at the Department of Oro-Maxillofacial Surgery and Stomatology, Semmelweis University.

2.2. Participants

Twenty participants were enrolled and randomly assigned to two groups (1:1 allocation):

- PRF Group (n = 10): standard apicoectomy with PRF membrane application;

- Control Group (n = 10): standard apicoectomy without PRF membrane.

All surgeries were performed by the same experienced surgeon according to standardized protocols. Outcomes included postoperative swelling, pain intensity, and health-related quality of life, measured using 3D facial scanning, the VAS, and the PROMIS-29+2 Profile v2.1 questionnaire [12,13].

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The participants included males and females aged 20 to 65 years who required an apicoectomy of maxillary or mandibular anterior or premolar teeth (second premolar to second premolar) because of a persistent periapical pathology. Specific clinical indications included chronic apical periodontitis, symptomatic periapical lesions, or radiographically confirmed periapical radiolucency associated with clinical signs such as percussion tenderness, swelling, or sinus tract formation. Diagnosis was confirmed through clinical examination and periapical radiographs.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: systemic conditions (such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus), neuropsychiatric disorders, immunocompromised status, use of anticoagulant or immunosuppressive medications, pregnancy or lactation, and any absolute contraindications to oral surgery.

These criteria ensured a homogeneous and medically stable study population and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

No routine hematological or platelet count tests were performed, as all participants were systemically healthy (ASA I–II) and had no history of hematologic or bleeding disorders or medication affecting platelet function.

2.4. Ethical Approval and Consent

The study protocol was approved by the National Public Health Centre (Nemzeti Népegészségügyi Központ, NNK; registration number: 3736-1/2022/EKU; approval date: 17 January 2023), and all procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the 2024 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or other applicable ethical standards.

2.5. Trial Registration

This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06739200) and first posted on 18 December 2024, ensuring transparency and compliance with international clinical trial standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before any study procedures were carried out. Each individual received written and verbal explanations about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Every participant also provided explicit written consent for the publication of de-identified data or images. This process was conducted according to ethical standards and ensured transparency regarding data use and dissemination.

2.6. Randomization and Allocation Concealment

The participants were randomly allocated to the PRF and control groups using a 1:1 allocation ratio. A computer-generated random sequence was created using the random number generator function of IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) by an independent research coordinator (Semmelweis University), who was not involved in patient recruitment, surgery, or outcome assessment. Allocation was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE method), which were prepared according to the randomization list. At the time of surgery, the next envelope in sequence was opened by a surgical assistant (Department of Oro-Maxillofacial Surgery and Stomatology, Semmelweis University) who was not involved in patient assessment, thereby ensuring proper allocation concealment.

2.7. Blinding

The patients were blinded to their treatment allocation throughout the study, and outcome assessors were also blinded to minimize detection bias. Venous blood was collected only from patients in the PRF group for membrane preparation, as blood sampling in the control group without clinical indication would have been ethically unjustified. The operating surgeon could not be blinded due to the nature of the intervention. Therefore, the study design corresponds to a single-blind randomized controlled trial. To mitigate potential bias, all outcome data were collected and analyzed by independent evaluators who were unaware of the allocation.

2.8. Surgical Procedure

All surgeries were performed by the same experienced oral surgeon at the Department of Oro-Maxillofacial Surgery and Stomatology, Semmelweis University, to ensure procedural consistency.

With the patient under local anesthesia (2% lidocaine with epinephrine), a trapezoidal submarginal flap (Ochsenbein–Luebke design) was raised to access the periapical lesion [20]. The apical 3 mm of the root was resected perpendicular to its long axis. A 3 mm retrograde cavity was prepared using ultrasonic tips and filled with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), a well-documented material with respect to root-end fillings [21].

In the PRF group, PRF membranes were prepared immediately prior to surgery following the PRF Plus protocol(Process for PRF, Nice, France) in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines and national venipuncture regulations (HarmonyCom, Hungary). A total of 10 mL of autologous venous blood was collected from each patient into sterile plain glass tubes without any additives or silica coating and processed within one minute of collection using an IntraSpin® fixed-angle centrifuge (33° rotor angle; Intra-Lock International Europe, Salerno, Italy) at 1300 rpm for 8 min, corresponding to approximately 200 g of relative centrifugal force (RCF). The resulting fibrin clots were compressed using a Choukroun-type PRF Box (Process for PRF, Nice, France) to obtain standardized membranes of uniform thickness, which were then placed E [15].

In the control group, the same surgical protocol was followed without applying any membrane or placebo material. This approach ensured that any postoperative differences could be attributed solely to the use of PRF.

Flaps were repositioned and closed using tension-free 3–0 silk sutures via the continuous locking technique [22]. Postoperative care instructions were standardized across both groups.

2.9. Postoperative Care

All the participants received standardized postoperative instructions. Pain was managed with 50 mg of diclofenac taken twice daily for three days [23]. Oral hygiene was maintained using 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash administered twice daily for one week. Sutures were removed on postoperative day 7. No antibiotics were prescribed routinely; they were only administered in cases with clinical indications [24]. However, no such cases occurred, and none of the participants required antibiotic therapy during the study. Because pain reduction was one of the anticipated potential benefits of PRF membranes, all patients—regardless of group allocation—received standardized analgesic care (diclofenac 50 mg twice daily for three days). This ensured that no participant was left untreated for pain in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Although the operating surgeon was not blinded due to the nature of the intervention, patient blinding, blinded outcome assessment, and standardized postoperative management were implemented to minimize bias in reporting and analysis.

2.10. Outcome Measures

Three primary outcomes were assessed to evaluate postoperative recovery: quality of life, pain intensity, and facial swelling. All measurements were performed using validated tools and standardized time points.

- Quality of Life (QoL):

Health-related QoL was assessed using the PROMIS-29+2 Profile v2.1 questionnaire, which measures physical function, emotional well-being, sleep disturbance, pain interference, and social participation. Assessments were conducted preoperatively and on postoperative day 7 to evaluate recovery progression [25].

- 2.

- Pain Intensity:

Pain levels were recorded daily for seven days using a 10-point VAS, where 0 indicated no pain and 10 represented the worst imaginable pain [26].

- 3.

- Facial Swelling:

Volumetric analysis of facial swelling was performed using 3D optical scans acquired with the Einstar 3D scanner (Shining 3D, Hangzhou, China) at two time points: preoperatively (T0) and on postoperative day 3 (T1). Volume changes were calculated using digital alignment and Boolean subtraction of 3D models.

2.11. Three-Dimensional Image Acquisition and Analysis

Three-dimensional (3D) facial images were acquired at two time points—preoperatively (T0) and on postoperative day 3 (T1)—using the Einstar handheld extraoral 3D scanner (Shining 3D, Hangzhou, China). This device has been validated for reliable volumetric facial soft-tissue analysis [27].

Figure 1 shows a representative preoperative 3D facial scan acquired prior to surgery (T0).

Figure 1.

Preoperative scan of the patient.

To standardize the acquisition process, all patients were seated in the same dental chair in the natural head position (NHP), with relaxed facial muscles and closed eyes. Scans were captured according to the manufacturer’s protocol for portrait scanning.

Initial image processing was performed using ExStar software (v1.2), and STL files were exported for further analysis. Pre- and postoperative models were aligned using the global best-fit algorithm in ZEISS GOM Inspect (v15.2; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Mesh refinement and trimming were carried out in Meshmixer (Autodesk, San Francisco, CA, USA), following the methodology described by Buitenhuis et al. [6].

Trimming boundaries were defined based on anatomical planes: above the Frankfurt horizontal plane, below the hyoid bone, posterior to the preauricular skin crease, and posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

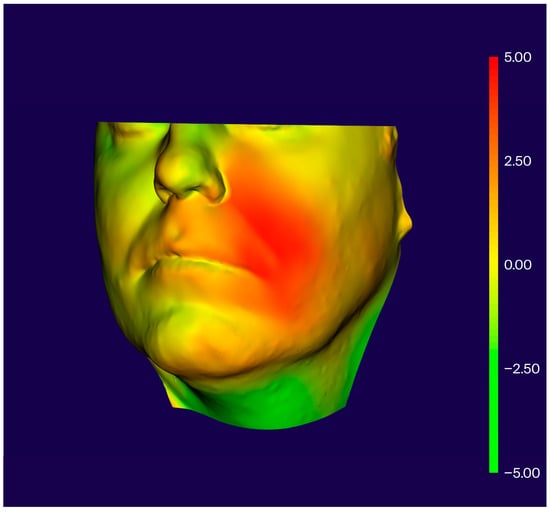

Volumetric swelling was calculated by generating solid bodies and performing Boolean subtraction between aligned scans, yielding the absolute volume difference between T0 and T1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Visualization of postoperative swelling after periapical surgery.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A significance threshold of α = 0.05 was adopted, and all reported p-values were two-tailed. Confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated and reported where applicable to provide precise estimates.

2.13. Normality Testing

The data distribution for each outcome variable was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

If the data were normally distributed, parametric methods were applied. Specifically, independent-samples t-tests were used to compare the PRF and control groups, and paired-samples t-tests were used to assess within-group changes (e.g., pre- and postoperative differences).

If the normality assumptions were not met, appropriate non-parametric alternatives were used. These included the Mann–Whitney U test for between-group comparisons and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for within-group comparisons. The choice of statistical tests was thus guided by the distributional characteristics of each variable.

2.14. Between-Group Comparisons

Differences in postoperative outcomes between the PRF and control groups were analyzed using either parametric or non-parametric methods, as described above. These outcomes included volumetric swelling (3D analysis), pain intensity (VAS scores), and domain scores from the PROMIS-29+2 Profile v2.1 questionnaire. The homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test, and appropriate test statistics were applied based on variance equality.

2.15. Within-Group Comparisons

Pre- and postoperative changes within each group were evaluated using paired-samples t-tests, particularly for PROMIS domain scores and pain intensity.

2.16. Correlation Analysis

Associations between continuous outcome variables (e.g., swelling volume, pain scores, and PROMIS domains) were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Separate analyses were conducted for the total sample and each group independently.

2.17. Analytical Approach

A per-protocol analytical approach was used. All 20 participants completed the study with no protocol deviations or dropouts, ensuring valid pairwise comparisons within and between groups.

As this was a preliminary randomized pilot trial, no formal power calculation was conducted. The sample size (n = 20; 10 per group) was chosen based on feasibility considerations and aligned with accepted principles for pilot study design, which prioritizes procedural refinement and estimation of effect sizes for future confirmatory trials [28].

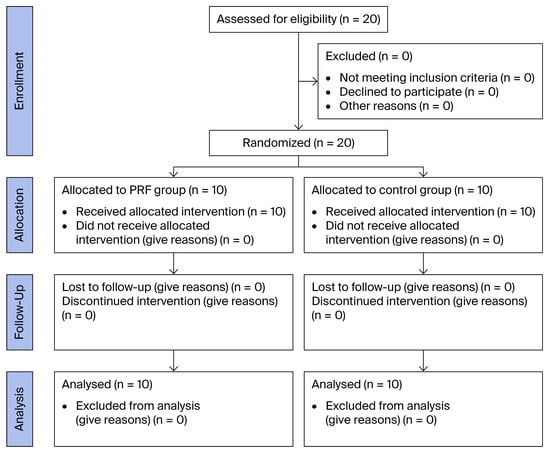

Figure 3 is a CONSORT flow diagram illustrating patient enrollment, randomization, allocation, and analysis across the study arms.

Figure 3.

CONSORT flow diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. No statistically significant differences were observed between the PRF and control groups in terms of age (40.3 ± 7.51 vs. 43.9 ± 7.43 years), while the sex distribution differed slightly, with the PRF group consisting of six males and four females and the control group comprising two males and eight females (Table 3). Additionally, the quality-of-life scores across all PROMIS-29+2 domains showed no significant group differences at baseline. For example, physical function scores were identical (18.7 ± 1.88 vs. 18.7 ± 2.58; p = 1.000), and anxiety levels were similar (7.9 ± 3.98 vs. 8.4 ± 3.86; p = 0.779), indicating comparable starting conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline (T0) quality-of-life dimensions.

Table 3.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the PRF and control groups.

3.2. Postoperative Quality of Life

On postoperative day 7, the PRF group showed statistically significant improvements across several PROMIS-29+2 domains relative to the control group. As shown in Table 4, patients who received PRF membranes reported better physical function, lower pain interference, improved sleep quality, and greater participation in social and cognitive activities. These findings suggest that PRF may positively influence early postoperative recovery and overall patient well-being.

Table 4.

Postoperative (T1, day 7 post-operation) quality-of-life dimensions.

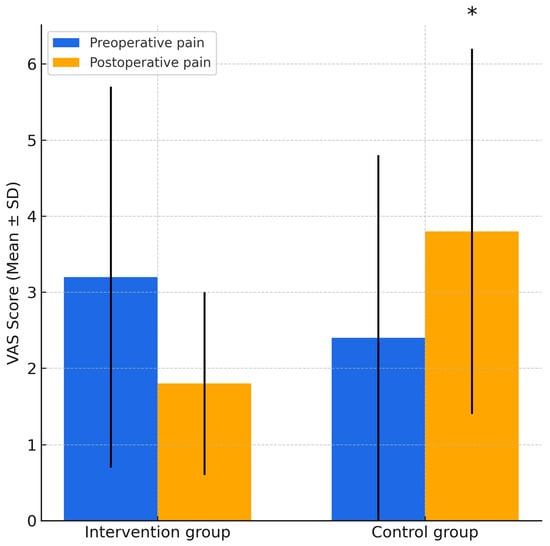

3.3. Postoperative Pain Assessment

Pain intensity was recorded daily using the VAS for seven consecutive days. As shown in Figure 4, the PRF group reported significantly lower average postoperative pain levels (1.80 ± 1.22) compared to the control group (3.80 ± 2.44). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.034; 95% CI: −3.82 to −0.18; F = 5.233, t = −2.315, df = 18), and the confidence interval did not cross zero, supporting the reliability of the finding. These results indicate that PRF membranes may improve pain control in the early postoperative phase.

Figure 4.

Comparison of preoperative and postoperative VAS pain scores in the PRF and control groups. Error bars represent standard deviations. * indicates a statistically significant difference between groups in postoperative pain (p = 0.034, independent-samples t-test).

3.4. Postoperative Swelling

Postoperative facial swelling was assessed on day 3 using 3D surface scanning and volumetric analysis. As shown in Table 5, the PRF group exhibited significantly lower swelling volume (15.93 ± 4.12 cm3) compared to the control group (23.05 ± 8.22 cm3), with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.025). These findings suggest that PRF membranes may contribute to reduced soft-tissue inflammation and improved healing in the early postoperative phase.

Table 5.

Volumetric analysis of swelling.

3.5. Correlation Analysis Results

Correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between postoperative swelling and various PROMIS-29+2 quality-of-life domains. As shown in Table 6, a statistically significant negative correlation was observed between swelling and sleep disturbance in the PRF group (r = −0.705; p < 0.05), suggesting that patients with greater facial swelling tended to report poorer sleep quality. No other domains demonstrated significant correlations with swelling in either group.

Table 6.

Correlation between swelling and quality-of-life dimensions.

3.6. Adverse Events

No adverse events were reported in either the PRF or control groups throughout the study period. All the patients completed the postoperative follow-up without complications, and no unexpected medical or surgical issues were observed. Adverse events were prospectively monitored and included postoperative infection, secondary bleeding, wound dehiscence, allergic reactions, delayed healing, and systemic complications (e.g., fever, hospitalization).

4. Discussion

The results of the present randomized controlled trial rejected the null hypothesis, demonstrating that the application of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes significantly improved postoperative outcomes compared with conventional apicoectomy. Patients treated with PRF exhibited markedly reduced facial swelling, lower pain intensity, and improved quality-of-life scores during the early postoperative period. These findings support the hypothesis that PRF can accelerate healing and enhance patient recovery following periapical surgery.

Several studies have previously demonstrated the clinical benefits of PRF in promoting soft-tissue healing and reducing postoperative discomfort. For instance, Fan et al. [15] provided a comprehensive overview of PRF applications in oral and maxillofacial procedures, highlighting PRF’s role in modulating inflammation and supporting tissue regeneration. Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Sinha et al. [3] confirmed that PRF significantly reduces postoperative pain and enhances healing in periapical surgery through the sustained release of growth factors. The biological basis for our findings is consistent with the platelet-related properties of PRF described by Dohan et al. [9], including its capacity to release growth factors that support soft-tissue healing. A randomized controlled clinical trial conducted by Meschi et al. [12] demonstrated that PRF combined with an occlusive membrane significantly improved bone healing and soft-tissue outcomes following root-end surgery.

Recent innovations in platelet-rich fibrin technology have introduced antibiotic-loaded PRF (AL-PRF), in which antimicrobial agents are incorporated into the fibrin matrix to provide localized antimicrobial delivery while retaining the autologous scaffold. A recent systematic review of in vitro studies reported that AL-PRF can inhibit bacterial growth and may enhance the structural stability of the fibrin scaffold; however, standardized preparation protocols and clinical evidence are still limited [29]. Although AL-PRF was not used in the present trial—and no systemic antibiotics were required for any participant—this next-generation approach may warrant investigation in future endodontic microsurgery studies to determine whether localized antimicrobial delivery confers additional clinical benefit beyond conventional PRF.

Regarding patient-reported outcomes, our findings align with those of Mubarak et al. [13], who emphasized the positive impact of PRF on patient comfort and quality of life. Our study builds on this through our application of the PROMIS-29+2 Profile, a multidimensional instrument that captures both the physical and psychological dimensions of recovery. The validity of PROMIS tools in oral surgery research has been confirmed in previous studies [25,30], supporting their application in our evaluation protocol.

Furthermore, swelling assessment using 3D optical imaging—as implemented in our study—has also been validated in the literature. Buitenhuis et al. and others have demonstrated that volumetric facial scanning provides reliable and reproducible measurements for postoperative evaluation [6,27], reinforcing the objectivity of our approach.

The results of this study suggest that PRF membranes may be a valuable adjunct in periapical surgery for promoting early postoperative recovery. The observed reduction in facial swelling, decrease in pain levels, and improved quality of life parameters in the PRF group support its clinical utility. These findings are consistent with prior evidence indicating that PRF enhances soft-tissue regeneration, modulates inflammation, and reduces postoperative discomfort [3,5,13,15,19]. PRF has also shown consistent regenerative outcomes in the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects, as reported in systematic reviews. Liu et al. [16] provided a detailed classification of PRF-based materials and emphasized their effectiveness as bone graft substitutes in maxillofacial regenerative procedures.

From a clinical standpoint, PRF is an autologous, low-cost biomaterial that can be prepared chairside without chemical additives or complex protocols [15,16]. Its ease of use and biological compatibility make it suitable for routine application in surgical endodontics. Notably, Al-Hamed et al. [19] and Ramos et al. [5] demonstrated improved healing and reduced morbidity when PRF was applied in third-molar surgeries, outcomes that align with our present findings in the periapical context. Clinical evidence from Praganta et al. [18] further supports the efficacy of advanced PRF protocols in reducing postoperative swelling and pain following oral surgical procedures.

Furthermore, the integration of validated patient-reported outcome tools such as the PROMIS-29+2 Profile aligns with current best practices in patient-centered research. The improvements in sleep quality, physical function, and social engagement observed in our study reinforce previous findings that emphasized the role of PRF in enhancing postoperative quality of life [4,13].

Taken together, the evidence supports the incorporation of PRF membranes into standard periapical surgical protocols, particularly in cases where accelerated healing, reduced morbidity, and improved patient experience are prioritized.

Moreover, while this study was conducted at a single academic institution using a standardized protocol, the findings may have broader applicability. PRF membranes are cost-effective, autologous materials that can be prepared with minimal equipment and are therefore feasible in a variety of clinical settings, including general dental practice and low-resource environments [15]. Future studies should investigate their utility in other oral surgical procedures and in diverse healthcare systems to assess the consistency of benefits across different patient populations, provider experience levels, and practice models.

5. Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size (n = 20) restricts its statistical power and may limit the ability to detect subtle group differences. Although appropriate for a preliminary investigation, these results should be interpreted with caution and validated through larger, adequately powered randomized trials [3,31].

Second, the short follow-up period of seven days captures only early postoperative outcomes. Long-term parameters such as bone regeneration, soft-tissue stability, and sustained quality-of-life improvements remain unaddressed. A volumetric follow-up study by Sharma et al. [32] demonstrated sustained healing in a large periapical lesion treated with PRF and bone substitute over a two-year period, supporting PRF’s long-term regenerative potential. Previous reports have shown that PRF may influence both short- and long-term healing, particularly when applied adjunctively in surgical procedures [19].

Third, this study was conducted at a single academic center under controlled conditions with one operator, enhancing internal consistency but potentially limiting external validity. Variability in surgical expertise, PRF preparation methods, and patient demographics across settings could influence clinical outcomes [4,33].

Moreover, several potential sources of bias must be acknowledged. The single-center design and strict eligibility criteria may have introduced selection bias, limiting the diversity of the study population. The use of a single-blind protocol (blinding only participants but not the surgeon) may have led to performance bias, as the surgeon was aware of group allocations. Although outcome assessments were performed by an independent evaluator, detection bias cannot be fully excluded. These factors may have influenced this study’s internal validity and must be addressed in future multicenter and double-blind trials to enhance methodological robustness.

Additionally, although validated instruments such as the PROMIS-29+2 were used to assess patient-reported outcomes, the sample’s cultural and linguistic characteristics may have influenced interpretation, as highlighted by Hungarian validation studies of the PROMIS framework [30]. Finally, no preoperative platelet count was obtained, which could have provided additional biological correlation with the quality of PRF clots.

While encouraging, these findings are limited by these methodological constraints. Larger, multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up periods are warranted to validate the observed benefits, assess long-term regenerative outcomes, and compare PRF with other autologous biomaterials such as platelet-rich plasma or advanced PRF variants.

6. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this preliminary randomized controlled trial, the use of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes significantly enhanced postoperative recovery following periapical surgery, resulting in reduced facial swelling, lower pain intensity, and improved quality-of-life outcomes. These findings indicate that PRF can serve as a simple, autologous, and cost-effective adjunct to conventional apicoectomy. Although encouraging, the results should be validated through larger multicenter studies with longer follow-up periods to confirm long-term regenerative effects. PRF appears to be a promising biomaterial for improving patient-centered outcomes in endodontic microsurgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., T.W., É.K. and G.S.; data curation, M.M., É.K., T.W. and M.P.; formal analysis, M.M. and T.W.; investigation, M.M. and G.K.; methodology, M.P., G.K., Z.N. and G.S.; project administration, M.M. and É.K.; resources, M.M., T.W., M.P., Z.N., É.K. and G.S.; software, T.W. and G.K.; supervision, Z.N.; validation, T.W., M.P., G.K., G.S. and É.K.; visualization, M.M. and M.P.; writing—original draft, M.M.; writing—review and editing, T.W., M.P., É.K. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Public Health Centre (Nemzeti Népegészségügyi Központ, NNK; registration number: 3736-1/2022/EKU; approval date: 17 January 2023) and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06739200); initial registration occurred on 12 December 2024 and was publicly posted on 17 December 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any study procedures. Each individual received written and verbal explanations about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. All participants also provided explicit written consent for the publication of de-identified data or images. This process adhered to ethical standards and ensured transparency regarding data use and dissemination.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PRF | Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| A-PRF | Advanced Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| L-PRF | Leukocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| MTA | Mineral Trioxide Aggregate |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| STL | Standard Tessellation Language |

| NHP | Natural Head Position |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Lieblich, S.E. Current concepts of periapical surgery: 2020 update. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 32, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchi, C.; Rosen, E.; Taschieri, S. Non-surgical root canal treatment and retreatment versus apical surgery in treating apical periodontitis: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Jain, A.K.; Rao, R.D.; Sivasailam, S.; Jain, R. Effect of platelet-rich fibrin on periapical healing and resolution of clinical symptoms in patients following periapical surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2023, 26, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuk, J.G.; Lindeboom, J.A.; Van Wijk, A.J. Effect of periapical surgery on oral health-related quality of life in the first postoperative week using the Dutch version of oral health impact profile-14. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 25, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.U.; Bizelli, V.F.; Baggio, A.M.P.; Ferriolli, S.C.; Prado, G.A.S.; Bassi, A.P.F. Do the new protocols of platelet-rich fibrin centrifugation allow better control of postoperative complications and healing after surgery of impacted lower third molar? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, M.B.; Klijn, R.J.; Rosenberg, A.; Speksnijder, C.M. Reliability of 3D stereophotogrammetry for measuring postoperative facial swelling. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Zucchelli, G.; Pikos, M.A.; Salama, M.; Lee, S.; Guillemette, V.; Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Bishara, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.L.; et al. Use of platelet-rich fibrin in regenerative dentistry: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan, D.M.; Choukroun, J.; Diss, A.; Dohan, S.L.; Dohan, A.J.; Mouhyi, J.; Gogly, B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, e37–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan, D.M.; Choukroun, J.; Diss, A.; Dohan, S.L.; Dohan, A.J.; Mouhyi, J.; Gogly, B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: Platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, e45–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan, D.M.; Choukroun, J.; Diss, A.; Dohan, S.L.; Dohan, A.J.; Mouhyi, J.; Gogly, B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part III: Leucocyte activation: A new feature for platelet concentrates? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, e51–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Fluckiger, L.; Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Sawada, K.; Sculean, A.; Schaller, B.; Miron, R.J. Comparative release of growth factors from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, N.; Vanhoenacker, A.; Strijbos, O.; Dos Santos, B.C.; Rubbers, E.; Peeters, V.; Curvers, F.; Van Mierlo, M.; Geukens, A.; Fieuws, S.; et al. Multi-modular bone healing assessment in a randomized controlled clinical trial of root-end surgery with the use of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin and an occlusive membrane. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4439–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, R.; Adel-Khattab, D.; Abdel-Ghaffar, K.A.; Gamal, A.Y. Adjunctive effect of collagen membrane coverage to L-PRF in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects: A randomized controlled clinical trial with biochemical assessment. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, M.; Gabbay, J.; Ai, A. Endodontic surgery and platelet concentrates: A comprehensive review. Periodontol 2000 2025, 97, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Perez, K.; Dym, H. Clinical uses of platelet-rich fibrin in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 64, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhai, P.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y. Platelet-rich fibrin as a bone graft material in oral and maxillofacial bone regeneration: Classification and summary for better application. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3295756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szentpeteri, S.; Schmidt, L.; Restar, L.; Csaki, G.; Szabo, G.; Vaszilko, M. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin membrane in surgical therapy of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praganta, J.; De Silva, H.; De Silva, R.; Tong, D.C.; Thomson, W.M. Effect of advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF) on postoperative level of pain and swelling following third molar surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 82, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamed, F.S.; Tawfik, M.A.; Abdelfadil, E.; Al-Saleh, M.A.Q. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin after mandibular third molar extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, I.; Malik, A. Evaluation of the Ochsenbein-Luebke flap technique in periapical surgery at Punjab Dental Hospital Lahore Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2003, 15, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Johnson, T.M.; Huang, D. Materials for retrograde filling in root canal therapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, CD005517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleier, D.J. The continuous locking suture technique. J. Endod. 2001, 27, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamed, S.F. Pain management following dental trauma and surgical procedures. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penarrocha, M.; Sanchis, J.M.; Saez, U.; Gay, C.; Bagan, J.V. Oral hygiene and postoperative pain after mandibular third molar surgery. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2001, 92, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Schalet, B.D.; Cella, D. PROMIS®-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.; Meszaros, B.; Wursching, T.; Polyak, M.; Kammerhofer, G.; Nemeth, Z.; Szabo, G.; Nagy, K. Evaluation of a structured light scanner for 3D facial imaging: A comparative study with direct anthropometry. Sensors 2024, 24, 5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.C.; Davis, L.L.; Kraemer, H.C. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, W.; Zurek, J.; Niemczyk, S.; Kepa, M.; Zieba, N.; Misiolek, M.; Wiench, R. Antibiotic-Loaded Platelet-Rich Fibrin (AL-PRF) as a New Carrier for Antimicrobials: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenei, B.; Bato, A.; Mitev, A.Z.; Brodszky, V.; Rencz, F. Hungarian PROMIS-29+2: Psychometric properties and population reference values. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 2179–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Penaloza, D.; Penarrocha-Diago, M.; Cervera-Ballester, J.; Penarrocha-Diago, M.; Tarazona-Alvarez, B.; Penarrocha-Oltra, D. Pain and quality of life after endodontic surgery with or without advanced platelet-rich fibrin membrane application: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Tandan, M.; Soi, S.; Gupta, A. Surgical management of a large endodontic periapical lesion with bone putty and platelet-rich fibrin: A case report with a two-year volumetric follow-up. Cureus 2024, 16, e69355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.L.; Gulabivala, K. Factors that influence the outcomes of surgical endodontic treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).