1. Introduction

The integration of intraoral scanners (IOSs) into the digital workflow has significantly improved modern dental practice, especially in prosthodontics. These technologies allow for accurate prosthetic planning and fabrication by leveraging computer-aided design and computer-assisted manufacturing (CAD/CAM) systems [

1,

2,

3]. Compared to conventional impression techniques, IOSs offer several advantages, including enhanced patient compliance, reduced chairside time, elimination of impression material distortion, easier data storage and transfer, and the ability to visualize scanned surfaces in three dimensions [

2,

4,

5].

However, despite these advantages, several factors may compromise scan quality in clinical settings. Errors can occur in the presence of saliva, crevicular fluid, or blood on dental and gingival tissues, or due to patient movement during the scanning procedure [

3,

6,

7]. IOSs generally project a structured light grid onto the teeth and capture the resulting distortion using high-resolution cameras. These images are processed by dedicated software to reconstruct a 3D model of the scanned area. This principle is shared with industrial-grade scanners [

8,

9,

10].

Conventional impression materials, such as polyvinyl siloxane and polyether, are still regarded as the gold standard in fixed prosthodontics. This is largely due to the limited number of in vivo studies that thoroughly assess the accuracy of digital impressions, particularly in complex cases. Additional clinical validation is required before digital impressions can be fully endorsed as an alternative to conventional methods [

3,

11].

A fundamental parameter in evaluating IOS performance is accuracy, which comprises trueness—the ability to reproduce the actual geometry of an object—and precision, defined as the consistency among repeated measurements under identical conditions [

3,

12,

13,

14]. While trueness is typically assessed by comparing digital to conventional impressions, precision refers to the degree of variability among successive digital scans. A scanner with high precision is expected to minimize the dispersion of the dataset [

15]. Precision may be particularly affected when scanning large objects such as full arches, due to the accumulation of alignment errors and the limited field of view of the scanner.

Intraoral scanning generates a 3D surface dataset through the superimposition of multiple captured frames. Errors in this stitching process tend to increase with the size of the scanned area, as more images must be aligned, which can compromise the final accuracy [

16]. Although several in vitro studies have reported high precision for full-arch scans, these do not account for variables encountered in vivo, such as reflective surfaces, intraoral moisture, and patient motion [

7,

10]. Only a limited number of studies have directly evaluated scan precision in the oral cavity [

16,

17]. For example, Kwon et al. found a mean absolute precision of 56.6 ± 52.4 μm when comparing various intraoral scanners (i500, CS3600, Trios 3, iTero (Rochester, NY, USA), and CEREC Omnicam, Bensheim, Germany), demonstrating the feasibility of in vivo precision assessments [

16].

Knowing the precision of IOSs is clinically valuable; however, most tools for 3D superimposition analysis are proprietary and expensive. Open-source software may serve as a valid alternative, offering free and accessible means of analysis [

18]. Nevertheless, their adoption in dentistry has been limited due to low-quality and incomplete documentation [

18].

The aim of the present in vivo study is to evaluate the precision of two intraoral scanners, 3Shape Trios (Milan, Italy) and Planmeca Emerald (Helsinki, Finland), using open-source software. The protocol is based on a previously published method that assessed the Medit i500 scanner (Seoul, Republic of Korea) [

19].

The null hypotheses were as follows:

No differences in precision (i.e., variance of repeated measures) exist among repeated digital impressions. There are no significant differences in the percentage of clinically acceptable deviations, defined as <0.3 mm [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

This in vivo experimental study aimed to evaluate the precision of two commercially available intraoral scanners—3Shape TRIOS 3 and Planmeca Emerald S—by performing repeated full-arch scans of a single healthy subject under standardized clinical conditions. The study design was based on the protocol previously described by Lo Giudice et al., which investigated the accuracy of the Medit i500 scanner using open-source 3D analysis software [

19].

2.1. Subject Selection and Ethical Considerations

A single adult volunteer with a full upper dentition (excluding third molars) and a Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index of zero was enrolled. The subject presented no signs of periodontal disease, restorations, or malocclusions that could interfere with the scanning process. The study adhered to ethical guidelines in line with the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the ethical committee (prot. n.95-23, 14 December 2022, Messina Local ethical committee, A.O.U. G. Martino, A.O. Papardo, A.S.P.). Prior to any procedures, each participant was provided with a brief written description of the study’s objective. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before their participation. The in vivo setting was chosen to replicate routine clinical conditions, introducing intraoral variables such as humidity, patient movement, and soft tissue presence. Although ISO 5725-1 [

20] recommends at least 30 repetitions per specimen for full metrological validation, such repetition is not feasible in vivo due to patient discomfort, ethical limitations, and time constraints. Therefore, the present study adopted the validated in vivo precision protocol proposed by Lo Giudice et al. (2022) [

19], which used five consecutive scans per device, generating ten pairwise comparisons for each scanner. This approach provides robust intra-operator repeatability while maintaining clinical realism. The present investigation involved a single participant, selected to ensure high internal validity and to reduce biological variability among scans, consistent with prior in vivo precision studies [

19]. Power analysis was not performed because the experimental unit was the repeated scan pair rather than the participant. The design followed validated in vivo protocols where repeated measurements under identical conditions provide sufficient statistical power to detect inter-device variability [

14,

19].

2.2. Operator Standardization

All scans were performed by one experienced operator with over ten years of clinical practice and extensive daily use of IOSs. This approach was adopted to minimize operator-related variability and enhance intra-operator repeatability. To ensure optimal device performance, the operator strictly adhered to the scanning protocols provided by each manufacturer, including device-specific calibration prior to each scan session.

2.3. Scanning Procedure

Each scanner was used to perform five consecutive scans of the maxillary arch on the same subject. No scanning sprays, opacifiers, or contrast agents were applied. The scanning sequence was standardized: the operator initiated the scan at the occlusal surfaces of the left second molar, progressing to the right second molar, followed by buccal surfaces and ending with palatal aspects. This sequence, recommended by the manufacturers, was selected to minimize deviation from best-practice techniques.

2.4. Data Processing and Format

All digital impressions were exported in the OBJ file format to maintain mesh fidelity and compatibility with open-source 3D analysis platforms. To isolate the relevant dental surfaces and eliminate interference from soft tissue, gingiva, and mucosa, digital trimming was performed using Autodesk Meshmixer (version 3.5.4). The segmentation process was conducted carefully to ensure that only anatomically consistent hard tissue regions were retained.

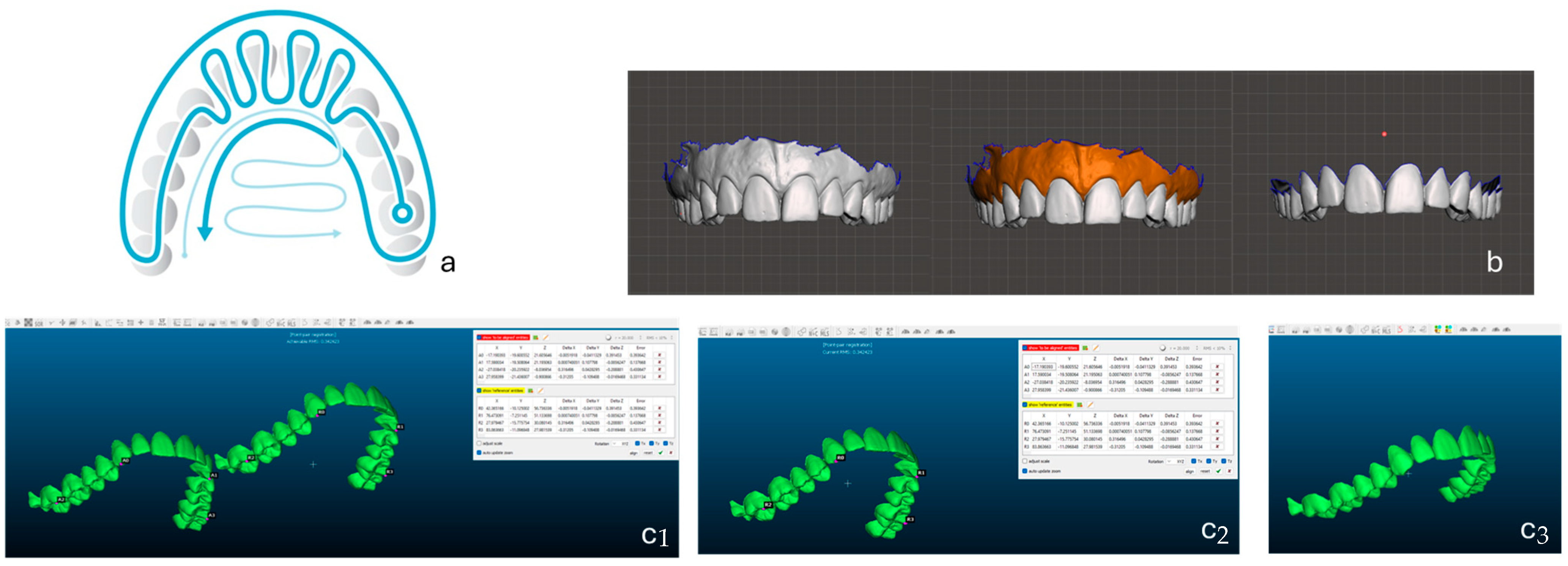

A schematic representation of the entire experimental workflow is provided in

Figure 1. The figure illustrates (a) the standardized scanning sequence (occlusal–buccal–palatal trajectory), (b) digital trimming and isolation of hard tissues in Autodesk Meshmixer, and (c(1–3)) subsequent alignment and deviation analysis performed in CloudCompare through landmark-based registration and iterative closest-point (ICP) refinement. This visual outline clarifies the sequential steps of the methodology and facilitates reproducibility of the protocol.

2.5. Alignment and Superimposition Protocol

The 3D models were imported into CloudCompare software (version 2.12) for alignment and deviation analysis. Each scan was paired with all others from the same scanner, producing ten pairwise combinations (Scan 1 vs. Scan 2, Scan 1 vs. Scan 3, etc.).

An initial rough alignment was performed using four manually selected anatomical landmarks: the incisal edges of the right and left central incisors and the mesio-buccal cusp tips of the right and left first molars. These reference points provided symmetrical and reproducible regions for alignment. A refined alignment was then conducted using the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm, which iteratively minimizes the mean point-to-point distance between meshes to achieve optimal superimposition. ICP was selected because it is widely recognized as the gold-standard algorithm for 3D surface registration in both industrial metrology and dental accuracy assessment [

6,

20]. To minimize operator bias during landmark selection, the same operator performed all alignments twice on randomly selected scan pairs, achieving a repeatability error below 0.05 mm. This confirmed the reliability and consistency of the manual landmarking procedure. This two-step alignment ensured high reproducibility and minimized operator-dependent bias.

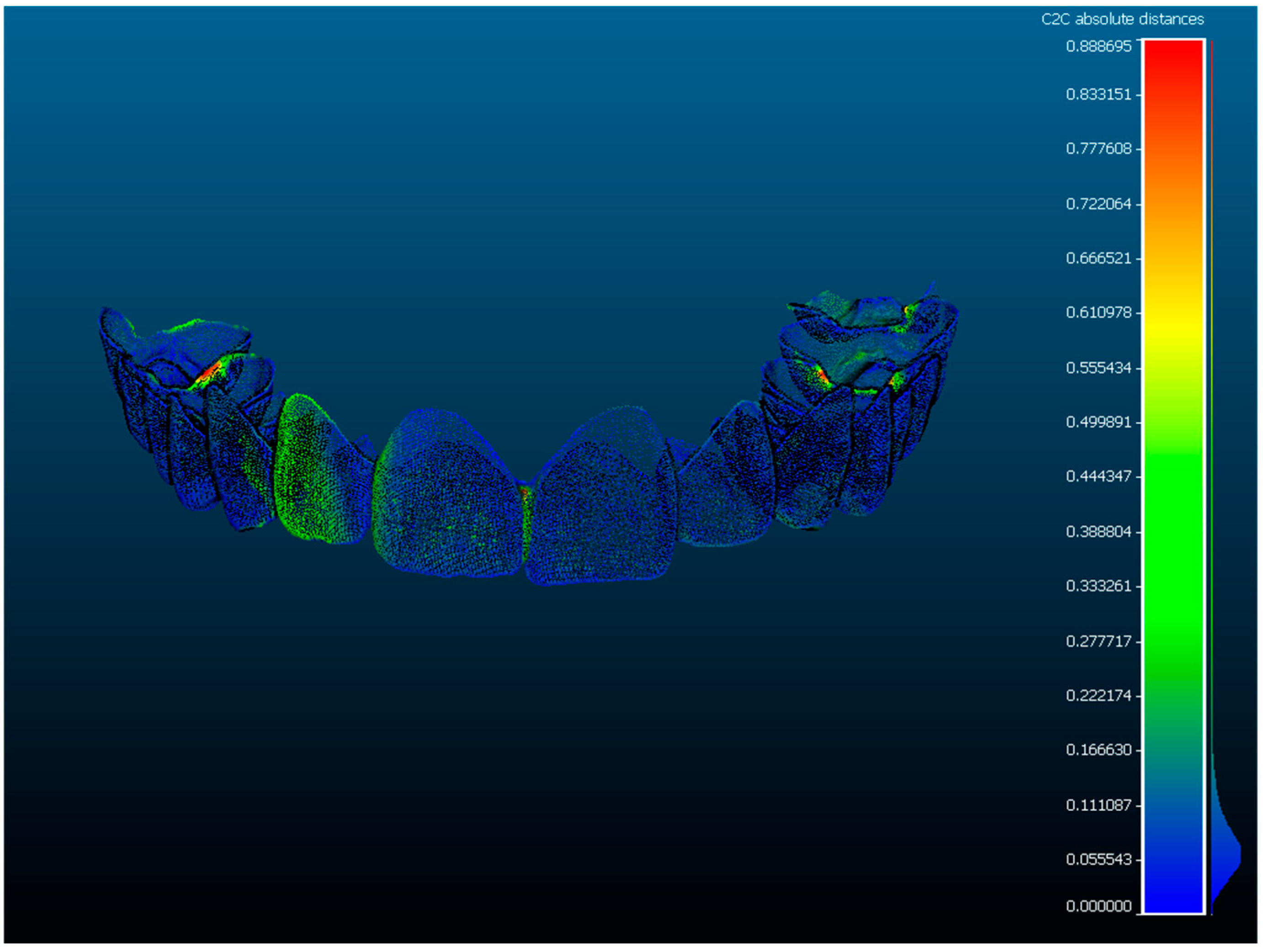

2.6. Deviation Assessment and Colorimetric Analysis

Once aligned, the surface-to-surface deviations were evaluated both qualitatively and quantitatively. Colorimetric deviation maps were generated to visualize spatial differences between the scans. These maps applied a calibrated chromatic scale to indicate areas of minimal and maximal deviation, facilitating intuitive visual interpretation.

Quantitative deviation data were calculated across all matched points for each pairwise comparison. Six deviation thresholds were evaluated: <0.01 mm, <0.05 mm, <0.1 mm, <0.2 mm, <0.3 mm, and <0.4 mm. These limits were selected according to previous studies demonstrating that surface deviations below 0.3 mm are clinically acceptable for full-arch digital impressions [

6,

19]. The percentage of surface points falling within each range was recorded, and mean ± standard deviation values were calculated across all scan pairs for each scanner.

2.7. Data Presentation

Results were tabulated separately for each scanner, with detailed reporting of the percentage of points within each threshold, providing a robust comparison of the scanners’ performance. A schematic illustration of the experimental workflow is provided in

Figure 1. Deviation and distribution between the scanners with interscan comparisons are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Representative colorimetric heat maps generated during the analysis are shown in

Figure 6, where green indicates minimal deviation and red/blue correspond to positive and negative discrepancies. These visualizations facilitate intuitive interpretation of spatial error distribution.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed to compare scanner precision. For each threshold (<0.01 mm to <0.4 mm), the mean percentage of surface points and corresponding standard deviations were computed across ten scan-pair comparisons per device.

Differences between the two scanners were evaluated using paired

t-tests at the <0.1 mm and <0.3 mm thresholds, representing high-resolution and clinically acceptable accuracy levels, respectively [

6,

19]. The significance level was set at

p < 0.05. The coefficient of variation (CV) was also calculated to quantify relative dispersion and assess measurement stability. For each inter-scanner comparison, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were also calculated to quantify the magnitude and precision of the observed differences.

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.2 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

Each 3D model obtained from the intraoral scans was sequentially labelled (Scan 1 to Scan 5) to facilitate pairwise comparisons. For each intraoral scanner, ten scan-pair combinations were generated (e.g., Scan 1 vs. Scan 2, Scan 1 vs. Scan 3, etc.), resulting in twenty total comparisons across the two devices. These were used to quantify the deviations in surface registration between repeated scans, expressed in millimetres (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

Colorimetric deviation maps were generated using CloudCompare to provide a visual representation of surface discrepancies. As shown in

Figure 6, green areas indicate minimal deviation between superimposed scans, while red and blue areas reflect positive and negative deviations, respectively. These maps allowed for intuitive assessment of spatial accuracy across the dental arch and facilitated the identification of regions with greater mismatch, typically in the posterior sectors (

Figure 6).

3.2. Quantitative Deviation Analysis

Surface deviation was evaluated across six thresholds: <0.01 mm, <0.05 mm, <0.1 mm, <0.2 mm, <0.3 mm, and <0.4 mm. For each scan pair, the percentage of points falling below these thresholds was calculated. Summary data for Planmeca and 3Shape scanners are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. The mean values and standard deviations for each threshold across the ten scan pairs were also computed.

3.3. Planmeca Emerald S

The Planmeca scanner demonstrated moderate repeatability. At the clinically accepted threshold of <0.3 mm, the average percentage of compliant surface points was 92.9% ± 6.8%, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 7.3%, indicating moderate data dispersion. In the more restrictive threshold of <0.1 mm, the mean was substantially lower (47.3% ± 13.7%), reflecting greater variability.

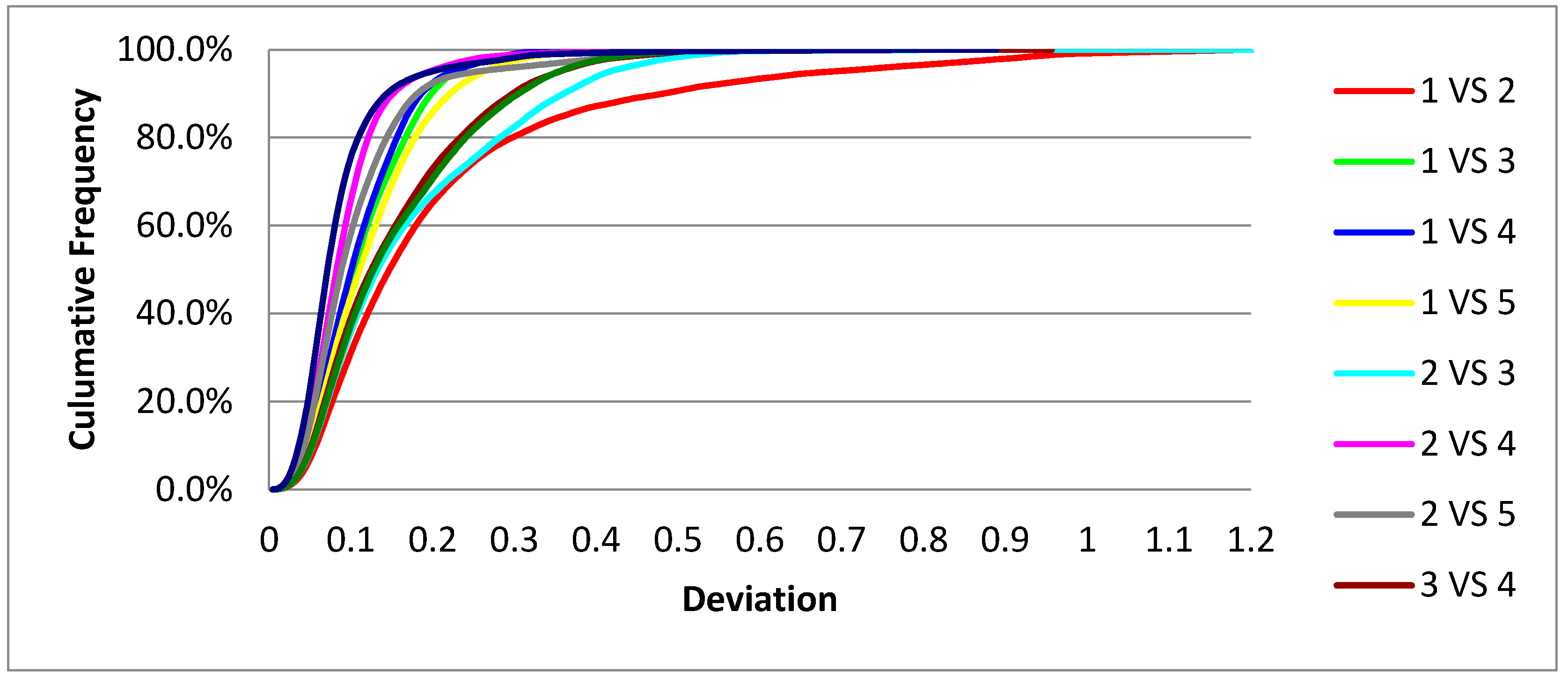

The cumulative distribution of deviation values (

Figure 2) and corresponding frequency distribution (

Figure 3) confirm that while most scan pairs reached acceptable accuracy by the 0.3 mm threshold, the scanner’s performance declined at narrower tolerances.

3.4. 3Shape TRIOS 3

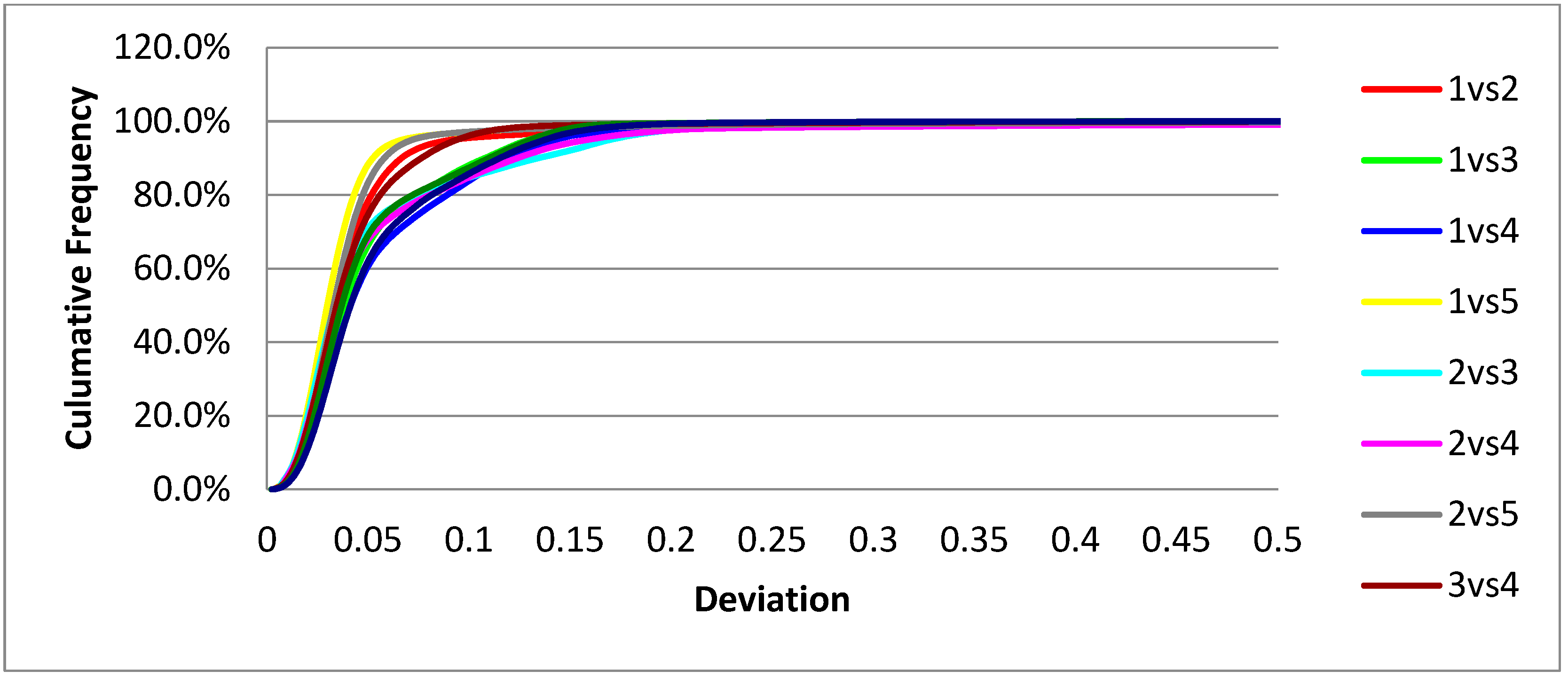

The 3Shape scanner exhibited superior precision. At the <0.3 mm threshold, the average percentage of points within acceptable deviation was 99.3% ± 0.4%, with a CV of just 0.4%, reflecting excellent repeatability and consistency across all scan pairs. At the <0.1 mm threshold, the scanner still maintained high performance, with an average of 89.6% ± 5.7%. Deviation trends are graphically illustrated in

Figure 4 (cumulative distribution) and

Figure 5 (frequency distribution), showing tightly clustered values and minimal variability.

Representative colorimetric heat maps (

Figure 6) illustrate the spatial distribution of deviations between repeated scans for both scanners. TRIOS 3 maps display predominantly green areas, indicating high repeatability and minimal surface variation, while Planmeca Emerald S maps show broader red and blue regions, especially in the posterior sectors. These visual results corroborate the quantitative findings reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2 and support the statistical significance of the observed differences (

p < 0.001).

3.5. Comparative Statistical Analysis

To statistically compare scanner performance, paired t-tests were conducted on the percentage of compliant points at the <0.1 mm and <0.3 mm thresholds across the ten scan-pair sets per scanner.

These findings confirm that 3Shape TRIOS 3 outperformed Planmeca Emerald S with statistical significance at both evaluated thresholds.

3.6. Combined Performance and Clinical Relevance

When combining the scan-pair results from both devices (n = 20), the overall mean precision at the <0.3 mm threshold was 96.1% ± 4.6%, with a combined coefficient of variation of 4.8%. This supports the clinical acceptability of both scanners within the evaluated threshold.

Nonetheless, the 3Shape scanner consistently delivered more accurate and reliable scans, especially at stricter tolerances, supporting its use in clinical applications where high precision is critical.

The use of colorimetric maps has allowed for an effective visualization of the deviations between the compared models, with a representative example shown in

Figure 6. Through the use of a color scale, these maps indicate areas with the most significant deviations, facilitating the visual interpretation of data.

The research also conducted a quantitative analysis of the deviations, focusing on the cumulative frequency of points recording a deviation below pre-established threshold. The results of this analysis were summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, where percentage data of points within specific deviation limits, along with mean values and standard deviations for each pair of models, were reported.

4. Discussion

The present in vivo study compared the precision of two widely used intraoral scanners—3Shape TRIOS 3 and Planmeca Emerald S—using a standardized full-arch scanning protocol and an open-source analytical workflow. Precision, defined as the degree of agreement among repeated measurements under identical conditions, represents a fundamental aspect of the overall accuracy of intraoral scanning, complementing trueness as established by ISO 5725-1 [

20]. The study focused exclusively on precision—the consistency among repeated measurements—without including a reference-based control group for trueness assessment. This design choice was deliberate, as the primary aim was to evaluate intra-operator repeatability under realistic clinical conditions rather than the absolute accuracy of each device. Nonetheless, the absence of a control group is acknowledged as a limitation, as it precludes direct comparison to a ground-truth model. Future research should include a reference scanner or master cast to quantify trueness in parallel with precision.

Both scanners achieved precision levels consistent with the clinically acceptable threshold of <0.3 mm, a limit commonly adopted in prosthodontic literature to ensure proper marginal adaptation and passive fit [

6,

7,

15,

21]. However, the quantitative findings demonstrated a clear difference between the two devices: TRIOS 3 achieved 99.3% ± 0.4% of points within the <0.3 mm threshold and 89.6% ± 5.7% within the <0.1 mm range, whereas Planmeca Emerald S reached 92.9% ± 6.8% and 47.3% ± 13.7%, respectively. The statistically significant results (

p < 0.001) confirm that these differences are not attributable to random variation. The deviation thresholds applied in this study (<0.01 mm to <0.4 mm, with <0.3 mm as the clinically acceptable limit) were derived from the literature on complete-arch accuracy [

6,

22,

23]. This threshold has been consistently adopted in the literature as the upper limit for clinical acceptability in full-arch digital impressions, ensuring marginal adaptation comparable to conventional materials [

6,

15,

24]. These boundaries align with ISO 5725-1 standards and ensure comparability with previous investigations by Ender and Mehl (2013) [

6] and Lo Giudice et al. (2022) [

19], who validated similar precision criteria in in vitro and in vivo contexts, respectively.

From a clinical perspective, these outcomes underscore the importance of distinguishing between scanners according to the tolerance requirements of specific rehabilitative procedures. [

25,

26] While both systems may be suitable for conventional restorative workflows—such as single crowns or short-span prostheses—where dimensional deviations up to 300 µm do not compromise adaptation [

3,

27,

28], only TRIOS 3 demonstrated repeatability compatible with the more stringent tolerance levels (<100 µm) needed for implant-supported or full-arch restorations [

6,

29,

30]. In these cases, even minimal inter-scan variability can translate into clinically significant misfits, jeopardizing passive fit and potentially leading to mechanical complications such as screw loosening or prosthetic stress [

31,

32].

The findings are coherent with previous in vivo and in vitro investigations assessing IOS performance. Ender and Mehl [

6] reported that cumulative errors tend to increase with the length of the scanned arch, particularly beyond the premolar region. Similarly, Kwon et al., [

14] observed a mean absolute precision of 56.6 ± 52.4 µm when comparing five intraoral scanners, noting that posterior sectors exhibited the greatest deviations. In our study, colorimetric deviation maps (

Figure 6) confirmed that discrepancies were concentrated in the posterior segments for both scanners, yet more pronounced with Planmeca Emerald S. This pattern is consistent with the limited field of view and frame-stitching accumulation intrinsic to the scanning technology [

10,

16,

28]. The lower standard deviation observed for TRIOS 3 reflects its higher capture frequency and larger field of view, which minimize cumulative stitching errors. In contrast, Planmeca Emerald S, based on sequential image stitching with smaller optical frames, is more susceptible to cumulative drift, particularly in posterior regions. These hardware and software differences account for the disparity in precision consistency between devices.

The high performance of TRIOS 3 can be attributed to its advanced optical triangulation and real-time correction algorithms, which enhance surface recognition and reduce cumulative drift. These characteristics explain the low standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV = 0.4%) recorded in our dataset, reflecting exceptional measurement repeatability. Comparable findings were described by Lo Giudice et al., [

19], who, using an open-source protocol similar to the present one, reported a precision of 98.8% ± 1.4% within the <0.3 mm threshold for the Medit i500 scanner. The current results not only confirm the feasibility of open-source metrology but extend its validation to multiple scanner systems, reinforcing reproducibility across platforms.

The integration of open-source software (Autodesk Meshmixer and CloudCompare) proved effective for both qualitative and quantitative analyses. Previous reviews have expressed concern that non-commercial software may suffer from incomplete documentation or limited standardization [

33]; however, our workflow demonstrated that, when properly configured, open-source solutions can yield precise, repeatable, and cost-efficient results. This represents a relevant contribution for academic and clinical environments where access to proprietary metrology tools is restricted. By enabling accurate superimposition and deviation measurement through freely available tools, this study supports the democratization of digital metrology in dental research [

18].

The methodological design also contributes to the internal validity of the results. Scans were performed consecutively on a single healthy subject by an experienced operator following manufacturer-recommended trajectories (occlusal–buccal–palatal path). This minimized intra-operator variability and reduced random errors associated with repositioning or recalibration. Similar approaches have been recommended by Müller et al., [

17] and Schmidt et al., [

20], who highlighted operator experience and scan strategy as key determinants of reproducibility. The five-scan per-device design yielded ten pairwise comparisons per scanner, generating a statistically robust dataset for precision estimation.

Clinically, the differences observed between scanners should guide the practitioner’s device selection based not only on global accuracy but also on the consistency required for the intended application. High-precision procedures such as digital implant guide fabrication, long-span frameworks, and longitudinal digital monitoring of soft tissue changes demand the lowest possible variance among scans. Conversely, less demanding restorative workflows may tolerate higher variability without significant impact on clinical outcomes [

21,

22,

23].

Beyond its immediate implications for prosthodontics, the validation of open-source workflows contributes to broader clinical integration of digital technologies. Digital imaging and 3D scanning are increasingly complemented by diagnostic modalities such as CBCT or MRI, which enhance both accuracy and functional assessment [

34]. The synergy between scanning, virtual planning, and additive manufacturing has been demonstrated in maxillofacial reconstruction and surgical navigation [

35,

36], underscoring how precision analysis forms the foundation for successful computer-assisted treatment. When comparing our results to previous studies, TRIOS 3 displayed a precision (99.3% ± 0.4% within < 0.3 mm) comparable to or exceeding that reported by Lo Giudice et al. (2022) [

19] for Medit i500 (98.8% ± 1.4%), while Planmeca Emerald S demonstrated slightly lower but still clinically acceptable performance. Kwon et al. (2021) [

14] observed wider variability among scanners under in vivo conditions, reinforcing the value of the present findings in confirming repeatability using an open-source protocol. The novelty of this research lies in demonstrating that free, non-proprietary platforms—Autodesk Meshmixer and CloudCompare—can achieve metrological reliability equivalent to commercial systems, enabling cost-effective and transparent validation workflows in clinical research. The reliability of CloudCompare as a deviation-analysis platform has been documented by Chruściel-Nogalska et al. (2017) [

33], who demonstrated accuracy comparable to commercial metrology tools for surface registration. Lo Giudice et al. (2022) [

19] further validated the same open-source workflow for intraoral scanner evaluation, confirming its metrological robustness and reproducibility in clinical applications.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, the study presents several limitations. The use of a single subject and a single dental arch restrict the generalizability of the results and precludes formal power analysis. Only precision was evaluated, without trueness measurements or reference-standard validation. Future investigations should include a larger sample size determined through power analysis, multiple operators to evaluate inter-operator variability, and comparative assessments of open-source versus proprietary metrology software. Incorporating trueness measurements and reference-based models will further enhance the external validity of future research. Precision alone was investigated, whereas trueness—the deviation from a physical reference standard—was not measured, limiting the completeness of the accuracy assessment [

7,

12]. Furthermore, soft-tissue regions were intentionally trimmed to improve measurement consistency, which excludes clinically relevant data for edentulous or partially edentulous arches [

31,

36,

37]. Future research should include larger and more heterogeneous samples, multiple operators, and combined trueness-precision analysis to enhance external validity.

In conclusion, within these boundaries, the present work demonstrates that open-source tools can provide reliable, reproducible, and clinically meaningful measurements of intraoral scanner precision. Both scanners achieved precision suitable for clinical application, yet the statistically superior repeatability of TRIOS 3 indicates its suitability for procedures requiring high fidelity. The results corroborate the concept that accessible, transparent analytical workflows can effectively support precision-based digital dentistry, facilitating broader adoption of accurate and cost-efficient digital workflows in both clinical and research contexts [

38,

39].

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this in vivo investigation, both intraoral scanners evaluated—3Shape TRIOS 3 and Planmeca Emerald S—demonstrated clinically acceptable precision for full-arch digital impressions, as defined by deviation values within the <0.3 mm threshold. Nevertheless, statistically significant differences were found in repeatability and measurement stability, indicating superior performance of TRIOS 3. The scanner achieved 99.3% ± 0.4% precision within < 0.3 mm and 89.6% ± 5.7% within < 0.1 mm, compared with 92.9% ± 6.8% and 47.3% ± 13.7%, respectively, for Planmeca Emerald S (p < 0.001).These findings suggest that while both devices are suitable for general restorative procedures, TRIOS 3 offers a level of precision more appropriate for demanding applications such as implant-supported rehabilitations, full-arch frameworks, and digital monitoring of peri-implant or soft-tissue changes over time. The reduced variability observed with TRIOS 3 also supports its use in longitudinal assessments where reproducibility between scans is critical.

From a methodological perspective, the present research confirms the validity of an open-source analytical workflow combining Autodesk Meshmixer and CloudCompare for precision evaluation. This approach enables accurate and cost-effective assessment of digital devices without reliance on proprietary metrology platforms, representing a valuable tool for clinicians and institutions seeking reproducible, transparent, and accessible evaluation methods.

Future studies should expand the investigation to multiple subjects, different operators, and various scanning trajectories, integrating both trueness and precision assessments. Such evidence will contribute to defining standardized protocols for scanner validation and to optimizing digital workflows that align with the principles of precision, reproducibility, and clinical reliability in contemporary dentistry. Clinicians are encouraged to consider not only the general acceptability of digital impressions, but also the specific performance characteristics of each scanner. Factors such as repeatability, scan trajectory optimization, and precision thresholds must be critically assessed when selecting a device for specific clinical applications. Furthermore, the current findings highlight the need for ongoing validation of intraoral scanners in real-world conditions, and support the development of standardized, reproducible protocols for evaluating digital impression quality.

Future studies involving a larger sample size, multiple operators, and the inclusion of trueness measurements are recommended to further confirm these results and expand the generalizability of the findings.