Abstract

Aim: This study aimed to determine the oral health profile of children with autism spectrum disorder and to analyze the impact of their oral health status on their personal quality of life and the quality of life of their families. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional online study was conducted on 121 parents. A self-structured questionnaire was used to collect data on sociodemographic characteristics, parents’ perceptions of their child’s oral health, oral hygiene practices, and access to dental care. Additionally, the Parental–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ-16, 16 items) and the Family Impact Scale (FIS-8, 8 items) were employed. The data were analyzed descriptively and using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Results: No significant differences were found in FIS-8 and P-CPQ-16 scores between parents and children based on their sociodemographic characteristics. However, a significant association was observed between P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 total scores and the type of used dental care (general dental practice vs. adapted practice and general anesthesia, p ≤ 0.001), dental visit frequency (regular vs. occasional, p < 0.05), child cooperation level during dental visits (cooperative vs. uncooperative, p ≤ 0.001), and dental care access challenges (p < 0.05). Parents reported a high prevalence of poor oral health in their children: the experience of tooth decay (48.1%), malocclusion (47.1%), bruxism (38.8%), bad breath (34.7%), and toothache (28.8%) in the previous 12 months. Most children brushed their teeth daily (89.3%), often with the help of their parents (44.6%). The most frequently reported difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene was the children’s unwillingness to cooperate (62.8%). Conclusions: Poor perceived oral health in children with autism spectrum disorder is significantly linked to a lower quality of life for both them and their families, especially when access to dental care is difficult and there is a lack of cooperation. Addressing these barriers and the high prevalence of oral health problems through tailored strategies is critical to improving children’s well-being.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex and heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder defined by social communication and interaction deficits accompanied by repetitive behaviors or intensely restricted interests. Although the underlying etiology is believed to be multifactorial, incorporating genetic, environmental, and immunological factors, the worldwide prevalence has increased systematically over the past 20 years. According to recent estimates, the overall prevalence ranges from 1.5% to 2%, with men experiencing a higher incidence than women [1,2]. It is crucial to emphasize that recent advancements in the understanding of autism have led to a shift in terminology, with Autism spectrum condition (ASC) increasingly being preferred over Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This change is driven by a growing recognition of the need to adopt a more inclusive, person-centered language that reflects the heterogeneity of the condition. Both ICD-11 and DSM-5 recommend the use of ASC to reduce stigma and to better capture the diverse neurodevelopmental profiles and strengths of individuals on the spectrum. This shift aligns with current efforts to promote a more nuanced and respectful discourse surrounding autism in clinical and research contexts [3]. In Croatia, the Croatian Register of Persons with Disabilities and the Croatian Institute of Public Health systematically collect and monitor data about people with ASD. As per the latest data available, 4730 persons with ASD have been reported, with a prevalence rate of 1 per 1000 populations (i.e., the number of diagnosed cases as per available records). The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in the population aged 0 to 19 years is 3574 individuals, including 724 females [4].

Children with autism spectrum disorders frequently exhibit unique behavioral and sensory habits that have a major influence on their oral health. These habits cover a wide range of factors, such as poor food choices, self-harming tendencies, negative drug reactions, increased sensitivity to oral hygiene products, and reduced sensitivity to dental pain [5]. Food selectivity is especially concerning because it can have a substantial impact on oral health by resulting in nutritional deficiencies, making children more prone to diseases like gingivitis, slowing the healing of wounds, and raising the risk of oral cavity infections. When it comes to eating habits, individuals with ASD frequently exhibit a preference for soft, sugary foods, which makes them more prone to dental cavities [6,7]. Caries and gingivitis can also be caused by poor oral hygiene, which is frequently brought on by heightened sensory responses and a lack of fine motor skills. Additionally, gingival overgrowth and decreased salivary flow may result from the medications prescribed to this population. Furthermore, the tendency to harm oneself by biting or stabbing oneself, which is frequently observed in conjunction with angry and tantrum-prone episodes, often results in ulcers, damage to the oral mucosa, bruxism, and subsequent dental damage [5,7,8,9].

Oral hygiene is a crucial aspect of the overall health of children with ASD and has a major impact on their quality of life. Many children with ASD have difficulty maintaining oral hygiene due to increased tactile sensitivity, communication difficulties, and additional factors such as limited fine motor skills and resistance to brushing [6]. These challenges often lead to various dental and health complications, including pain, which can further impact essential daily functions such as eating, sleeping, and social interactions [10,11,12,13]. Parents of children with ASD often face significant challenges with daily oral hygiene, with more than half of autistic children requiring partial or full assistance with tooth brushing [13,14,15]. As a result, parents caring for their child’s oral hygiene and dental care often feel very stressed. They struggle with emotional pressure, high medical bills, missed working hours, and changes in family and personal life. Many parents report that they face significant challenges when adequate dental care is not available or when conventional treatment methods prove ineffective for their child. It is therefore important to consider not only the oral health needs of the child but also how these needs affect the whole family. This broader perspective makes it possible to develop comprehensive care plans and support systems that improve the well-being of both the child and their family [11,12,13].

Despite the increasing interest in the health of children with ASD, oral health and its impact on quality of life remain relatively underexplored, particularly from the subjective perspective of parents. However, parents are most familiar with the daily challenges, routines, and behavioral changes in their children, making their observations an invaluable source of information [11,12,13]. In Croatia, although several studies have been conducted on the oral health of children with autism and its impact on the child and family quality of life, the parental perspective has been neglected [16,17,18]. In this context, this research aimed to collect data on the self-assessment of parents regarding the oral health of their children with ASD over the past 12 months, their oral hygiene habits, and the perceived impact of oral health on the quality of life of both the child and the family. The primary hypothesis of this study was that parents of children with autism spectrum disorder believe that poor oral health and limited access to dental care affect the quality of life of both the child and the family, and the oral hygiene habits of children with ASD differ from the appropriate recommendations for oral health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted via a self-administered online survey, which took place between 1 and 31 March 2025. This study was conducted by the Department of Restorative Dentistry and Endodontics at the University of Split, School of Medicine. This study followed the guidelines of the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [19].

This study consisted of a convenience sample, including parents of children with ASD who were members of the Autism Association of Croatia, comprising 17 individual associations. All associations were contacted via email on two occasions and were asked to forward the survey to their members’ parents/caregivers. Given that a larger study was conducted with the aim of assessing the quality of life of families, children, and persons with developmental disabilities, this study represents only a smaller segment, focusing specifically on children aged 3 to 18 years with a confirmed medical diagnosis of ASD and without any other type of disability.

The questionnaire was created using the Google Forms platform and distributed anonymously through the above-mentioned associations. To reduce selection bias and ensure a geographically diverse sample from across Croatia, each association received a brief explanation of the study’s purpose along with a request to share the survey link. Participation was open to anyone who expressed a willingness to participate, ensuring voluntary and anonymous involvement. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the questionnaire, where participants were provided with detailed information about the study. Completion of the questionnaire was considered consent to participate. No financial or other incentives were offered for their participation. Ethical approval of this study was adopted by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of the University of Split on 10 February 2025 (approval number 2181-198-03-04-25-0011).

2.2. Participants and Sample Size

According to a sample size calculator, based on an estimated population of 3574 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Croatia, the required sample size was calculated to be 347. However, since not all families of children with autism are members of the associations, it was not possible to determine the exact number of individuals who received the survey invitation. The required sample size was further determined based on the total score of the short form of the Parental–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ), as reported in a longitudinal study involving Brazilian children and adolescents with ASD who were aged 6 to 14 years [20]. Using the baseline mean P-CPQ score of 13.2 and a standard deviation of 6.4, the sample size was calculated with a 10% margin of error and a 95% confidence level. Based on these parameters, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 91 participants with ASD. The same sample size was also reported in another study conducted in Brazil involving children and adolescents with ASD [12].

To be eligible for participation, respondents had to be parents or primary caregivers of at least one child formally diagnosed with ASD, residing in Croatia, and having children aged 3 to 18 years. Parents of younger children, adults with ASD, and those who submitted incomplete responses were excluded. Additionally, individuals were excluded if they were not the primary caregiver of a child with ASD, if the child had not received a formal diagnosis, or if the respondent did not reside in Croatia. Incomplete questionnaires were also excluded from the final analysis.

2.3. The Survey

To meet the survey’s objectives, a semi-structured questionnaire was carefully constructed by a Croatian research team with diverse expertise, including an endodontic and restorative specialist (A.T.), a general practitioner who was also a PhD student (M.B.), and a dental student (L.P.). Its content was grounded in a thorough review of the relevant literature [12,13,16,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

The final version of the questionnaire consisted of six sections with a total of 70 items and required approximately 12 to 15 min to complete. The first section included nine questions focusing on the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender, age, education level, employment status, healthcare background, household income, place of residence, and the age and gender of their children. The second section comprised six questions related to the child’s dental care, including the type of dental services used, the frequency of dental visits, the child’s cooperation during appointments, difficulties encountered in accessing care, and whether dental care had been previously established. The third section contained twenty questions addressing parent- or caregiver-reported oral health problems experienced by the child in the past 12 months, including tooth decay, dental plaque, malocclusion, bruxism, halitosis, pain, and related issues. The fourth section consisted of eleven questions on oral hygiene practices, covering the frequency of toothbrushing, the level of independence in maintaining oral hygiene, manual coordination, the type of toothbrush used, the use of supplementary hygiene aids, main challenges in oral hygiene, receipt of professional guidance, and interest in oral health education. This section also included self-assessments of satisfaction with dental care availability and quality, perceived child’s oral health status, and the impact of the child’s oral health on the family’s quality of life. In the fifth section, the Parental–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) was used, which consisted of 16 questions, evaluating the children’s oral health and its effect on their overall well-being. It was divided into four subscales: oral symptoms (OSs), functional limitations (FLs), emotional well-being (EWB), and social well-being (SWB). The questions referred only to the frequency of events in the previous six months. The items are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, where ‘never = 0’, ‘once or twice = 1’, ‘sometimes = 2’, ‘often = 3’, and ‘every day or almost every day = 4’. An ‘I don’t know’ response was also permitted and scored as 0. Each subscale consisted of 4 items, with the score for each domain ranging from 0 to 16, while the overall score ranged from 0 to 64. The final section addressed the impact of the child’s condition on the family and was assessed using the Family Impact Scale (FIS-8), which consists of 8 items that evaluate the influence of oral health on family quality of life. The scale is divided into three domains: family activities, parental emotions, and family conflicts. The FIS-8 also employs a five-point Likert-like scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 32, with higher scores indicating a greater negative impact of the child’s oral condition on the family [28]. Both questionnaires used in this study—the P-CPQ-16 and the FIS-8—were previously validated in the Croatian language [29,30].

2.4. Data Analysis

All fully completed questionnaires were compiled using Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics provided summaries of the data, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables such as participants’ demographic characteristics, oral health status, and data related to the impact of oral health on the quality of life in children and their families, while means or medians with standard deviations or first and third quartiles were provided for continuous variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess the normality of data distribution. Group differences in P-CPQ and FIS-8 total scores were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test for two-category comparisons and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons involving three or more categories [31]. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

This study included 121 parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. The average age of parents was 41.7 ± 6.4 years (median = 41.0, Q1-Q3 = 38.00–46.00, min = 27, and max = 56) and the average age of children was 10.5 ± 4.1 years (median = 7.0, Q1-Q3 = 7.00–14.00, min = 3, and max = 17). Q1 and Q3 refer to the first and third quartiles, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed in FIS-8 and P-CPQ-16 scores in relation to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, socioeconomic status, and education, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data of parents and children compared to total scores of the FIS-8 and P-CPQ-16 questionnaires.

Table 2 presents information regarding dental care in comparison to total FIS-8 and P-CPQ scores. More than half of the respondents (57.9%) reported regular dental visits, and 76.9% had visited their dentist within the past 12 months. Nearly half of the respondents (49.6%) reported difficulties in accessing dental care, which was statistically associated with higher P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 scores (p ≤ 0.001). Approximately one-third (33.9%) of children were uncooperative during their dental visits and have also experienced statistically higher FIS-8 and P-CPQ scores (p ≤ 0.001). Statistically higher FIS-8 and P-CPQ scores were observed among parents whose children had been treated in dental offices with adaptation protocols or had undergone sedation or general anesthesia for dental procedures (p ≤ 0.001).

Table 2.

Dental care of children compared to total FIS-8 and P-CPQ-16 scores.

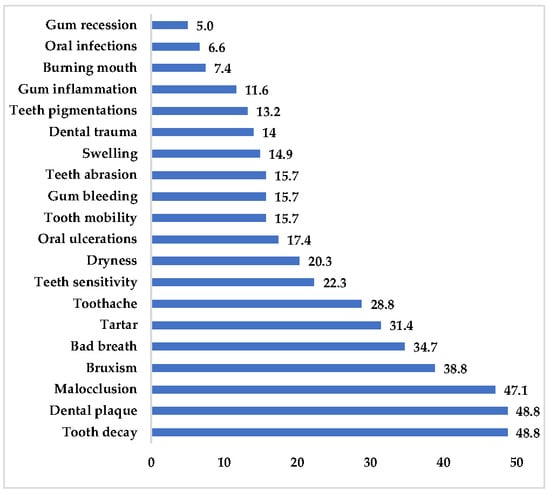

Figure 1 illustrates oral health problems reported by parents in the past 12 months. Nearly half of the children experienced dental caries (48.8%) or dental plaque (48.8%), followed by orthodontic issues such as malocclusion (47.1%). Other commonly reported problems included bruxism (38.8%), halitosis (34.7%), calculus (31.4%), and toothache (28.8%).

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of a child’s oral health in the past 12 months based on parental self-assessments.

Table 3 presents the reported oral hygiene practices of children. Most of them brush their teeth once (43.0%) or twice (46.3%) a day. Slightly less than half (44.6%) require parental assistance in maintaining oral hygiene. Fluoride toothpaste was used by 70.2% of children. Other adjunctive oral hygiene aids were used less frequently, such as dental floss (14.0%) and interdental brushes (14.0%), which was hardly surprising for this specific age group. The main difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene was the child’s non-cooperation (resistance or refusal), which was reported by 62.8% of parents.

Table 3.

Oral hygiene practices of children.

Table 4 presents the P-CPQ-16 results. The total mean ± SD score was 18.4 ± 12.5. Among the subscales, emotional well-being recorded the highest score, with a mean ± SD of 5.84 ± 4.38. This subscale included items related to irritability (1.64 ± 1.34), distress (1.62 ± 1.35), and anxiety (1.50 ± 1.37).

Table 4.

Results of P-CPQ-16 scores shown as the mean (SD) and median (IQR).

Table 5 presents the FIS-8 results. The total mean ± SD score was 8.90 ± 6.60. Among the subscales, parental activities recorded the highest score, with a mean ± SD of 5.16 ± 3.92. This subscale included items related to the need for attention (1.95 ± 1.44).

Table 5.

Results of FIS-8 scores shown as the mean ± SD and median (Q1–Q3).

4. Discussion

Oral health is a crucial component of overall well-being, with oral diseases posing significant public health concern due to their high prevalence and associated health burden. These conditions contribute to social, economic, and psychological consequences, impacting an individual’s and their family’s quality of life [32]. Children with special needs often tend to face increased oral health burdens, characterized by limited access to preventive care, a higher prevalence of extractions, and reduced availability of healthcare services, all of which can adversely affect their overall health and quality of life [33]. Therefore, this study aimed to assess parental- and caregiver-reported oral health information, as well as the quality of life of families with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders using the P-CPQ 16 and FIS-8 scales.

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders often experience more oral health issues, including tooth decay, periodontal disease, and self-injurious behaviors such as trauma and bruxism [5,6,7,8,9]. The most significant oral health problems reported by parents in the present study were tooth decay (48.8%), dental plaque (48.8%), and malocclusion (47.1%) in their children. Dental caries represents a significant oral health concern among individuals with autism spectrum disorder. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis from 2025 identified a significant difference in dental caries severity between children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their neurotypical peers, as measured by the DMFS index [34]. According to a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of caries in this population was estimated at 60.6%, highlighting the urgent need for targeted preventive strategies [35]. Similar findings were observed in a study conducted at the Dubai and Sharjah Autism Centers, where 77.0% of children diagnosed with autism experienced dental caries, which is statistically more than healthy children [36]. In contrast, one study conducted among Libyan children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder, compared to a healthy control group, found that children with ASD were more likely to be caries-free, had lower DMFT scores, but exhibited higher unmet periodontal treatment needs than their unaffected peers [37].

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often encounter substantial behavioral challenges, including aggression and self-harming behaviors, which elevate the risk of orofacial trauma. Common craniofacial characteristics, such as anterior open bite and Class II malocclusion, further increase their vulnerability to dental injuries, particularly to the maxillary central and lateral incisors [38]. In this study, 47.1% of parents reported malocclusion, while 38.8% noted bruxism in their children. Similarly, a study conducted in Alexandria, Egypt, found that self-injurious behavior and bruxism were significantly more common among children with ASD, with 32% of these children affected, compared to only 2% in the control group (p < 0.001) [39]. These findings highlight the heightened risk of dental issues in children with ASD, underscoring the importance of early intervention and tailored dental care for this population.

Oral hygiene is a crucial aspect of dental care, yet individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often face difficulties maintaining proper oral hygiene due to sensory sensitivities and behavioral challenges. A notable challenge in providing dental care for individuals with ASD is their resistance to routine oral hygiene practices, particularly when caregivers carry out these tasks. The sensory discomfort associated with brushing, along with issues like motor coordination difficulties, can lead to inconsistent oral care, increasing the risk of dental conditions such as caries and gum disease. Consequently, caregivers and dental professionals must adapt strategies and provide supportive interventions to help these individuals manage their oral health effectively [7]. In this study, nearly half of the children (46.3%) brushed their teeth twice or more times a day, while 43.0% brushed once a day. The majority (44.6%) required partial parental assistance during brushing, while 27.3% needed full assistance. The primary challenge in maintaining oral hygiene was the child’s non-cooperation, including resistance and refusal to engage in the brushing routine, as reported by 62.8% of the parents. Other studies have reported differing findings, such as a study from São Paulo, Brazil, which found that 64.2% of parents assist their children with brushing their teeth. In comparison, 45.0% noted that their child becomes anxious or nervous before or after brushing [40]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Croatia among caregivers reported that most participants (66.7%) maintained their oral hygiene with the help of their caregivers [16]. In this study, parents or caregivers did not report sufficient use of auxiliary oral hygiene aids, as only 14.0% of children used dental floss or an interdental brush. This is an important finding, as inadequate interdental cleaning can contribute to plaque accumulation and increase the risk of caries and periodontal problems. However, it is important to note that the use of dental floss in children is less crucial than effective plaque control achieved through regular toothbrushing. A somewhat higher proportion of children (33.3%) used dental floss in a study on autism spectrum disorder conducted in San Francisco, highlighting a notable difference in oral hygiene practices compared to the present sample [14]. Children with autism face significant challenges in maintaining oral hygiene, particularly with toothbrushing and using interdental aids. Sensory sensitivities to toothpaste taste and difficulties with motor coordination make these tasks more challenging. Furthermore, behaviors such as food selectivity, unusual eating habits, and prolonged food retention in the mouth can contribute to poor oral health. As a result, these factors can lead to an increased risk of dental caries and periodontal issues in children with autism. Therefore, a tailored approach to oral care is essential, considering their unique needs and sensitivities, to prevent dental complications and promote better oral health outcomes [41].

This study used the P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 scales to assess the quality of life of parents/caregivers associated with the oral health of their child. The sociodemographic characteristics of parents/caregivers in this study did not influence P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 scores. Similar findings were observed in a cross-sectional study conducted at the Autism Institute of Amazonas in Manaus, Brazil, where P-CPQ and FIS scores showed no statistically significant differences according to sex, age, family income, maternal education level, or dental caries experience in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder [21]. Furthermore, a study conducted among parents with children with intellectual disabilities has also confirmed those results regarding FIS-14 scores [22]. However, another study from Brazil investigating the parental perception of the oral health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder found that family functioning, as assessed by FIS-4 scores, was less affected by oral conditions in families where parents had an elementary school degree (OR = 0.314), while it was most affected in families whose income was less than or equal to the minimum wage (OR = 3.049) [12].

The P-CPQ-16 subscale with the highest mean (SD) in this study was emotional well-being, with a mean (SD) of 5.84 (4.38). Similar results were observed in a study conducted in Alfenas-MG, Brazil, among parents of children with special healthcare needs using the P-CPQ-33, where the mean (SD) score for the emotional well-being subscale was 11.34 (5.82) [23]. However, other studies have reported contrasting findings, identifying oral symptoms as the subscale with the highest mean scores. This was observed in a study among parents of autistic children following full mouth rehabilitation under general anesthesia, with a mean score of 5.80 (2.30) [24], as well as in a study conducted in Piracicaba, SP, Brazil [12], where the mean was 3.58 (2.69). Similarly, a study from Sergipe, Brazil [9], reported a mean of 8.95 (3.35), and research involving children with special needs in Johannesburg, South Africa, found a mean (SD) of 4.62 (3.91) [25]. One study investigating parental perceptions of the oral health-related quality of life of autistic children in Saudi Arabia identified social well-being as the subscale with the highest mean (SD), reported as 11.95 (6.00) [26].

The FIS-8 subscale with the highest mean (SD) in this study was parental activities, recorded with a mean (SD) of 5.16 (3.92). A study among parents of autistic children following full mouth rehabilitation under general anesthesia using the FIS-14 scale has also identified family activities as the subscale with the highest mean (SD) of 5.73 (3.14) [24]. On the other hand, a study investigating parental perceptions of the oral health-related quality of life of autistic children in Saudi Arabia using the FIS-14 scale identified family emotions as the subscale with the highest mean (SD), reported as 4.98 (3.70) [27].

In the present study, significantly higher scores on both the P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 scales were observed among children who underwent sedation or general anesthesia for dental treatment, those who were uncooperative during dental care, whose parents reported difficulties in providing oral care, or whose dental care had not yet been established (p < 0.05). These findings are consistent with previous research. One study reported that children undergoing comprehensive dental treatment under general anesthesia initially showed significantly higher scores on both the P-CPQ and FIS, indicating a greater negative impact on their oral health-related quality of life [42]. Similarly, Guney et al. (2018) also demonstrated that children who required sedation or general anesthesia due to uncooperative behavior or extensive dental needs presented with higher levels of dental anxiety and poorer quality of life scores before treatment, as measured by both scales [43].

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, data collection was conducted exclusively online via autism-focused associations gathered under a national umbrella organization. Although all 17 member associations were contacted and asked to distribute the survey to their members, participation was limited to families affiliated with these organizations. According to national data, there are 3574 registered children with autism spectrum disorder in Croatia, and based on this population, the required sample size calculated using a sample size calculator was 347. However, as not all families of children with ASD are members of such associations, it was not possible to determine how many individuals received the invitation, nor to what extent the final sample is representative. Secondly, one limitation of this study was that the types and severity levels of autism among participants were not identified or differentiated. This lack of specification may have influenced the findings, as individuals with varying forms and degrees of autism can exhibit different characteristics and responses, potentially affecting the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, convenience and snowball sampling methods may have introduced sampling bias and led to an overrepresentation of certain caregiver profiles. Self-reported data introduce the possibility of recall and social desirability bias, and the child’s ASD diagnosis or caregiver status was not externally verified; furthermore, although validated instruments (P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8) were used, reliance on parental self-reporting may also lead to subjective interpretation and potential response bias. Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, incomplete responses had to be excluded, and no follow-up was possible. Lastly, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to conclude causality between the studied variables.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant oral health challenges faced by children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Croatia and the associated impact on their families’ quality of life. High rates of dental problems, such as caries, plaque, and malocclusion, along with behavioral barriers to oral hygiene and dental care access, were frequently reported by caregivers. The findings reveal that uncooperative behavior, a lack of established dental care, and the need for sedation or general anesthesia are strongly associated with poorer oral health-related quality of life scores, as measured by the P-CPQ-16 and FIS-8 scales. Despite the lack of significant associations with sociodemographic variables, the emotional and practical burden on families was evident. These results underscore the need for tailored oral health programs, increased awareness, and support systems to improve dental outcomes and overall well-being for children with ASD and their families. Future studies should aim to include larger, more representative populations and incorporate clinical oral examinations to validate self-reported data and provide a more comprehensive assessment of oral health status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.B., L.P. and A.T. Data curation: M.B., L.P. and A.T. Formal analysis: M.B. and A.T. Methodology: M.B. and A.T. Validation: A.T. Writing—original draft: M.B., L.P. and A.T. Writing—review and editing: M.B., L.P. and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Medicine, the University of Split, Split, Croatia, on February 10, 2025 (Class: 029-01/25-02/0001, Approval No.: 2181-198-03-04-25-0011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all of the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaing, C.C.; Lin, L.S.; Long, S.; Ke, X.Y.; Fukunaga, K.; Lu, Y.M.; Han, F. Signalling pathways in autism spectrum disorder: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales Hidalgo, P.; Voltas Moreso, N.; Canals Sans, J. Autism spectrum disorder prevalence and associated sociodemographic factors in the school population: EPINED study. Autism 2021, 25, 1999–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Clough, S. Autism spectrum condition: An update for dental practitioners—Part 1. Br. Dent. J. 2024, 237, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Report on People with Disabilities in the Republic of Croatia; Public Health Service: Zagreb, Croatia, 2023; Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Bilten_-_osobe_s_invaliditetom_2023.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Sami, W.; Ahmad, M.S.; Shaik, R.A.; Miraj, M.; Ahmad, S.; Molla, M.H. Oral Health Statuses of Children and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Umbrella Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E.; Fiori, F.; Ferraro, G.A.; Tessitore, A.; Nazzaro, L.; Serpico, R.; Contaldo, M. Autism Spectrum Disorder, Oral Implications, and Oral Microbiota. Children 2025, 12, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prynda, M.; Pawlik, A.A.; Emich-Widera, E.; Kazek, B.; Mazur, M.; Niemczyk, W.; Wiench, R. Oral Hygiene Status in Children on the Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.F.; Salerno, C.; Bravaccio, C.; Ingenito, A.; Sangianantoni, G.; Cantile, T. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Oral Health Status: Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.P.; Du, R.; Peng, S.; McGrath, C.P.; Yiu, C.K. Oral health status of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of case-control studies and meta-analysis. Autism 2020, 24, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallea, A.; Vetri, L.; L’Episcopo, S.; Bartolone, M.; Zingale, M.; Di Fatta, E.; D’Albenzio, G.; Buono, S.; Roccella, M.; Elia, M.; et al. Oral Health and Quality of Life in People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, C.; Campus, G.; Bontà, G.; Vilbi, G.; Conti, G.; Cagetti, M.G. Oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescent with autism spectrum disorders and neurotypical peers: A nested case-control questionnaire survey. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 26, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.C.F.; Barbosa, T.S.; Gavião, M.B.D. Parental perception of the oral health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, V.d.S.; Fernandez, M.d.S.; Nunes, F.d.S.; Vieira, I.S.; Martins-Filho, P.R.S. Parental Caregivers Perceptions of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Dent. Health Oral Disord. Ther. 2020, 11, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagda, R.; Le, T.; Lin, B.; Tanbonliong, T. Oral Hygiene Practice and Home-Care Challenges in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in San Francisco: Cross-Sectional Study. Spec. Care Dentist. 2024, 44, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, H.; Schulte, A.G.; Fricke, O.; Schmidt, P. Tooth Brushing Behavior and Oral Health Care of People with Early Childhood Autism in Germany. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavic, L.; Brekalo, M.; Tadin, A. Caregiver Perception of the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Special Needs: An Exploratory Study. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancić Jokić, N.; Majstorović, M.; Bakarcić, D.; Katalinić, A.; Szirovicza, L. Dental Caries in Disabled Children. Coll. Antropol. 2007, 31, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Bakarcić, D.; Prpić, I.; Ivancić-Jokić, N.; Bilić, I.; Lajnert, V.; Buković, D. Dental Status as a Quality Control Health Care Parameter for Children with Disabilities. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, J.S.; Fernandes, R.F.; Andrade, Á.C.B.; Almeida, B.D.C.; Amorim, A.N.D.S.; Lustosa, J.H.D.C.M.; Mendes, R.F.; Prado, R.R., Jr. Impact of dental treatment on the oral health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Spec. Care Dent. 2021, 6, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.V.; Damasceno, M.E.S.; Zacarias Filho, R.P.; Hanan, S.A. Oral health-related quality of life among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A cross-sectional study. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín. Integr. 2024, 24, e230126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.S.; Fernandez, M.S.; Viana, V.S.; Silva, N.R.J.; Rodrigues, K.P.; Vieira, I.S.; Martins-Filho, P.R.S.; Santos, T.S. Factors Associated with the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Intellectual Disabilities. ODOVTOS-Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 23, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Caldeira, F.I.; Baeta-de-Oliveira, L.; Bintencourt-Reis, C.L.; Pedreira-de-Almeida, A.C.; Alves-Nogueira, D.; Coelho-de-Lima, D.; Silva-Barroso-de-Oliveira, D. Use of P-CPQ to Measure the Impact of Oral Health on the Quality of Life of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Rev. CES Odont. 2022, 35, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswad, N.A.; Abushanan, A.; Ali, S. Comparative Evaluation of Parental Perceptions of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Autistic and Non-Autistic Children after Full Mouth Rehabilitation under General Anesthesia. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 31, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nqcobo, C.; Ralephenya, T.; Kolisa, Y.M.; Esan, T.; Yengopal, V. Caregivers’ Perceptions of the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Special Needs in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 2019, 24, a1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, S.C.; Mubaraki, S.A.; Ahmed, Y.T.; Alturki, R.Y.; Almahfouz, S.F. Parental Perceptions of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Autistic Children in Saudi Arabia. Spec. Care Dentist. 2013, 33, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancio, V.; Faker, K.; Bendo, C.B.; Paiva, S.M.; Tostes, M.A. Individuals with Special Needs and Their Families’ Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Foster Page, L.A.; Gaynor, W.N.; Malden, P.E. Short-form versions of the Parental-Caregivers Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) and the Family Impact Scale (FIS). Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2013, 41, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumini, M.; Slaj, M.; Katic, V.; Pavlic, A.; Trinajstic, Z.M.; Spalj, S. Parental influence is the most important predictor of child’ s orthodontic treatment demand in a preadolescent age. Odontology 2020, 108, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhac, M.; Zibar Belasic, T.; Perkovic, V.; Matijevic, M.; Spalj, S. Orthodontic treatment demand in young adolescents—Are parents familiar with their children’ s desires and reasons? Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun-Harris, L.A.; Canto, M.T.; Vodicka, P.; Mann, M.Y.; Kinsman, S.B. Oral Health Among Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020025700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, R.P.; Klein, U. Autism Spectrum Disorders: An Update on Oral Health Management. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2014, 14, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, T.P.; da Mota, D.G.; Bitencourt, F.V.; Jardim, P.F.; Guimarães Abreu, L.G.; Zina, L.G.; Guimarães de Abreu, M.H.N.; Vargas-Ferreira, F. Dental Caries of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, S.N.; Gimenez, T.; Souza, R.C.; Mello-Moura, A.C.; Raggio, D.P.; Morimoto, S.; Lara, J.S.; Soares, G.C.; Tedesco, T.K. Oral health status of children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 27, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.A. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2011, 19, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakroon, S.; Arheiam, A.; Omar, S. Dental caries experience and periodontal treatment needs of children with autistic spectrum disorder. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, P.M.; Parascandolo, S.; Fiorillo, L.; Cicciù, M.; Cervino, G.; D’Amico, C.; De Stefano, R.; Salerno, P.; Esposito, U.; Itro, A. Dental Trauma in Children with Autistic Disorder: A Retrospective Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3125251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khatib, A.A.; El Tekeya, M.M.; El Tantawi, M.A.; Omar, T. Oral Health Status and Behaviours of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Case–Control Study. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 24, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, S.R.V.; Lopes-Herrera, S.A.; Santos, T.H.F.; Danielle, A.; Martins, A.; Sawasaki, L.Y.; Fernandes, F.D.M. Oral hygiene and habits of children with autism spectrum disorders and their families. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2020, 12, e719–e724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, G.; Karayagmurlu, A.; Dagli, I.; Aren, G.; Soylu, N. Oral Health Status in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross Sectional Study from Turkey. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, Z.D. Effects of dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia on children’ s oral health-related quality of life using proxy short versions of OHRQoL instruments. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 308439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisour, E.F.; Heidari, F.; Nekouei, A.H.; Jahanimoghadam, F. Postoperative acute psychological complications following dental procedures under general anesthesia in uncooperative children. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).