Abstract

This study investigates how women at a Muslim island community-based tourism (CBT) site convert performed respectability and routine paperwork into everyday organizational authority. Drawing on four months of ethnographic fieldwork in Bang Rong, Phuket—supported by seventeen semi-structured interviews, three years of social-media observation (2023–2025), and analysis of rosters, ledgers, receipts, and LINE threads—the study examines how gendered norms and material devices structure authority in daily tourism practice. The analysis identifies an authorization stack (veil, uniform, tone) and a set of paperwork devices (ledgers, rosters, receipts, digital groups) that make women’s visibility both morally credible and institutionally legible. Using a poststructural feminist lens and Barriteau’s gender-system framework, the article develops an interpretive, case-derived Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, showing that moral credit converts into procedural authority only when respectability cues align with control of at least one device. Conversion, however, remains partial and contingent: strategic levers stay largely male or mosque-adjacent unless women obtain rights-bearing tools, such as co-signature authority, petty-cash control, or platform access, along with institutional protection against sanction. Age, class, and endorsement shape these trajectories, enabling some women to consolidate authority while rendering others easily replaceable. The study contributes: (1) a case-specific, empirically grounded account of authority formation in island CBT; (2) an analytic lens for understanding how performance, devices, and rights interact in this setting; and (3) practice-oriented implications for small-island CBT contexts that emphasize shared device access, rotating administrative duties, co-signature and budget rights, and safeguards against organizational capture.

1. Introduction

Community-based tourism (CBT) is widely promoted as a pathway to inclusive and sustainable development, especially on small islands where economic bases are narrow, ecologies are fragile, and communities depend heavily on external intermediaries (Goodwin & Santilli, 2009; Scheyvens, 1999). Yet the participatory promise often obscures a familiar pattern: gendered hierarchies are reproduced within CBT systems. At many sites, “respectable” women become the public face of hospitality while ordinary women are routed into low-paid feminized tasks framed as natural extensions of care (Duffy et al., 2012). Although CBT research documents participation and livelihood gains, we know far less about how gendered authority is actually produced in daily coordination—how routine practices such as posting rosters, closing ledgers, or signing contracts are linked to the reproduction or contestation of power.

This article addresses that gap by examining how women at a Muslim island CBT site convert performed respectability and routine paperwork into organizational authority and why this conversion remains partial, uneven, and class differentiated. The study draws on four months of ethnographic fieldwork in Bang Rong, a prominent CBT site in Phuket, supported by seventeen semi-structured interviews, three years of social-media observation (2023–2025), and analysis of rosters, ledgers, receipts, and LINE communication threads. Using Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis (FPDA), the analysis traces how discourse, embodied practice, and control of material devices shape who becomes credible, who becomes audible, and who gains procedural or strategic power in everyday tourism coordination.

Conceptually, the article introduces the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, which synthesizes poststructural feminist perspectives with Barriteau’s (1998) distinction between ideological norms and material relations. The model identifies two linked mechanisms, (1) an authorization stack—veil, uniform, tone—that renders women morally credible and procedurally legible and (2) a material position composed of both paper power (control of ledgers, rosters, receipts, and digital groups) and resource levers (budget discretion, roster authority, platform access, and signatory rights), which together convert moral credit into coordination or strategic authority. The contribution of the model is offered cautiously and situated within this single case: it proposes one possible way of understanding how ideological legitimacy may become material authority in CBT, rather than claiming a universal mechanism. The model also shows why this conversion often stalls without rights-bearing tools (signatures, budgets, platform access) and institutional shields against sanction. Age and class further shape trajectories by structuring women’s access to devices, buffers, and endorsements.

Guided by this framework, the article asks three questions:

- (1)

- How does CBT foster classed and cohort-specific feminine subjectivities that perform respectability?

- (2)

- How do paperwork and digital devices convert respectability into coordination authority?

- (3)

- Under what conditions does coordination consolidate into autonomy—or stall and reverse?

The study makes three contributions. Empirically, it provides a case-based, generational account of authority formation in island CBT. Theoretically, it advances an analytical lens linking performance, devices, and rights, explaining how ideological and material conditions jointly shape gendered authority within this setting. Practically, it identifies context-specific implications for small-island CBT—formalizing women’s front-stage roles, democratizing access to administrative and financial devices, and establishing safeguards against organizational capture. Taken as a whole, this research offers a grounded account of how authority is assembled, negotiated, and at times stalled in one Muslim island community—an account that may serve as a comparative reference point for future work on gender, tourism, and rural governance.

2. Bang Rong in Context: Tourism Evolution and Gender Order

2.1. Tourism Development in Bang Rong

To situate the study’s analytical focus on gendered authority, this section outlines how Bang Rong’s tourism sector evolved and how shifting governance structures shaped everyday coordination roles.

Located in northeastern Phuket, Bang Rong is the largest of nine villages in Pa Khlok subdistrict (≈3000 residents; ~80% Muslim). Proximity to Ao Por Pier and Phuket International Airport, along with mangroves, seagrass habitats, and productive rubber and pineapple plots, positioned the village early for tourism. Its development unfolded across several phases shaped by local leadership and national tourism policy.

Foundations (1993–1999). Prior to tourism, villagers organized debt-relief and savings groups to manage indebtedness and land loss. These initiatives strengthened household liquidity and collective decision-making, providing early institutional scaffolding for later tourism initiatives (Theingthae, 2017).

Early ecotourism (1999–2010). Mosque-based leaders-initiated education-oriented ecotourism—guided mangrove walks, small-boat trips, simple meals, and island excursions. Although modest in scale, these activities established a conservation identity and a basic visitor management system. Alignment with national “self-sufficiency” and controlled-ecotourism policies brought visibility and technical support, culminating in a Thailand Tourism Award (2010).

Transition and vulnerability (2011–2019). Tourism gradually expanded from ecotourism to a broader CBT frame. However, revenues remained low and products narrow. The passing of the first-generation imam–village chief exposed person-dependent governance, creating a vacuum and generating factional contestation around religious and village offices. CBT participation weakened during this period.

Re-centering and revival (2021–present). Drawing on tourism experience, Man A reorganized operations and reconnected CBT to village development agendas. The COVID-19 Phuket Sandbox created renewed opportunity: a family-centered team (Man A, Woman A, their son, and relatives) professionalized reception, relocated activities to an organic farm and coconut grove, and diversified offerings (batik, rubber tapping, dessert-making, cooking, crab-bank observation) (see Figure 1 for landscape context). Pricing moved to premium tiers, and international visitors predominated. Bang Rong adopted a hybrid governance posture—cultivating tour-operator channels while keeping community participation open—alongside new sustainability certifications and third-generation leadership development.

Current debates. Bang Rong is now recognized as one of Phuket’s most active CBT sites, operating year-round with standardized products and clearer channels. However, reliance on family stewardship concentrates authority, transparency remains uneven, and margins are sensitive to sessional labor. Importantly for this study, CBT’s shift away from mosque governance has opened procedural space for women to assume coordination roles in reception, finance, and product design—while strategic decisions continue to gravitate toward male brokers.

This governance trajectory provides the institutional backdrop for analyzing how women convert respectability and paperwork into authority, and why such conversion remains constrained.

2.2. Bang Rong’s Gendered Moral Order

Bang Rong’s everyday life is shaped by an Islamic moral order in which modest dress, measured speech, and calibrated public presence signal respectability and moral trustworthiness. These norms strongly influence which community activities women can participate in and the kinds of authority they can exercise. Women are expected to embody ideals of the “good wife/mother”—care, reliability, and discretion—which align closely with CBT tasks such as cooking, welcoming visitors, preparing supplies, and maintaining simple accounts. The headscarf, adjusted in style and color according to context, enables women’s visibility in tourism spaces while signaling continued adherence to local expectations of modesty.

By contrast, men’s roles as household heads and community representatives position them at the center of decision-making circuits. Friday prayers and post-prayer discussions around the mosque function as informal governance arenas where information circulates and external contacts are cultivated. Because these spaces are male-dominated, men accumulate the social capital and networks needed for negotiations, pricing, contracts, and dealings with officials, reinforcing their position as default representatives of the community.

Two mechanisms enforce these boundaries: reputational regulation—gossip, teasing, and moral commentary that discipline women perceived as overstepping—and gendered spatial organization, which situates women’s CBT contributions in kitchens, courtyards, markets, and reception areas, while deliberation remains anchored in mosque-linked male spaces. Thus, although recent CBT organizational changes have expanded women’s administrative and front-stage responsibilities, strategic representation and formal negotiation remain largely male.

These intersecting moral, spatial, and reputational dynamics shape which forms of women’s respectability become visible and auditable—and which remain disqualified from strategic authority. They provide the ideological foundation for the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model developed in Section 6, explaining why women’s authority in CBT is often procedural rather than strategic.

Figure 1.

Bang Rong landscape: (A) Pineapple Plantation. (B) Coconut Plantation. (C) Rubber Plantation. (D) Seaside.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Thailand’s Community-Based Tourism Policy Ecology and Gendered Division of Labor

Community-based tourism (CBT) is commonly defined as tourism that is initiated, owned, and managed by local communities with the aims of distributing benefits equitably, strengthening local participation, and sustaining cultural and environmental resources (Goodwin & Santilli, 2009). In Thailand, CBT is widely promoted as a tool for inclusive development, especially in rural and small-island settings (JICA, 2019). Yet implementation varies considerably. Participation often ranges from symbolic involvement to meaningful decision-making (Tosun, 2000), and many initiatives appear “community-based” while strategic control remains concentrated among local elites or external actors (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., 2013). Scholars further note that CBT can reproduce existing social hierarchies and choreograph “authenticity” to meet tourist imaginaries (Sin & Minca, 2014). Thailand’s policy environment—shaped by the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy, OTOP schemes, provincial model-village programs, and certification regimes—encourages CBT development but simultaneously disciplines it through standardized expectations of service, hospitality, and community benefit (Sammukkeetham, 2021).

A gendered reading sharpens these critiques. While scholarship often highlights women’s empowerment through income, skills, and entrepreneurship (Susan, 2007; McCall & Mearns, 2021), evidence from the Global South shows uneven outcomes. Women are typically channeled into feminized, low-wage tasks aligned with domestic labor—homestays, cooking, craft retail—whereas men occupy brokerage positions tied to transport, negotiations, partnerships, and public representation (Duffy et al., 2012; Susan, 2007). In Thailand, studies consistently report that women shoulder front-of-house hosting and affective labor while men interface with officials, operators, and investors (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., 2013). In Muslim-majority coastal communities, modesty norms, mosque-centered rhythms, and gendered spatial practices further regulate women’s visibility and permissible participation (Kontogeorgopoulos, 2005). Certification and award systems often valorize “good service,” formalizing women’s emotional labor without granting strategic authority over prices, contracts, or governance.

Despite these insights, an important meso-level gap remains. Existing CBT and gender research rarely examines how gendered moral norms, spatial expectations, and routine administrative practices—posting rosters, closing ledgers, documenting receipts, managing digital communication groups—shape who becomes authoritative in everyday operations. Nor does it adequately explain how cultural legitimacy is converted into organizational power, particularly in Muslim Island settings where modesty, reputation, and kinship strongly regulate public life. This study addresses that gap by situating Bang Rong—a prominent Muslim Island CBT site in Phuket—within Thailand’s CBT policy ecology and its local Islamic moral order.

3.2. Performed Respectability and Feminine Subjectivity

Studies of gendered subject formation in post-structural feminist scholarship treat femininity and respectability not as inherent traits but as situated performances produced through discursive norms, embodied repetition, and community surveillance (Kelly, 2013). Within this tradition, several strands of literature clarify the mechanisms by which Bang Rong women cultivate moral legitimacy in tourism settings.

Skeggs’ analysis of “becoming respectable” is foundational. For Skeggs (1997/2014), respectable femininity is a classed moral project produced through continuous labor—appropriate dress, speech, comportment, and caregiving practices—that generates moral credit such as trust, recognition, and social value. This credit is symbolically powerful but often only weakly convertible into material gains.

Butler’s account of gender as a citational practice sharpens this mechanism. Respectability, like gender, is produced through repeated acts that cite recognizable norms—tone, honorific particles, veiling, uniforms, and kin roles—performed under social surveillance (Butler, 1990/2006). Deviations or “mis-citations” attract sanction, revealing the contingency and disciplinary force of the norm. Feminist readings of Foucauldian discipline further show how posture, modest comportment, and “professional” voice materialize these norms on the body (Bartky, 1990; Bordo, 1993).

Mahmood (2009) extends this tradition by reframing agency. Rather than assuming that empowerment must take the form of resisting norms, Mahmood argues that pious self-cultivation—modesty, discipline, virtuous demeanor—can furnish women with credibility and socially legible forms of authority. This insight is especially relevant for Muslim communities, where women’s disciplined comportment becomes the basis for being trusted as hosts, translators, and coordinators within tourism systems. Ahmed (2004) similarly shows how affect, kindness, and warmth circulate as affective capital that attaches virtue to bodies and spaces, especially in service economies.

Together, these studies conceptualize respectability as a citational, moral, and affective repertoire that produces recognizable subject positions. This mechanism forms the first layer of the paper’s Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model: the generation of moral credit through performed respectability.

3.3. Boundaries, Indexicality, and Sanction

While respectability operates through embodied performance, its credibility depends on the semiotic and social mechanisms that make such performances legible to others.

Boundary work, as described by Lamont and Molnár (2002), distinguishes symbolic boundaries—shared classifications of what counts as “proper,” “modest,” or “representative”—from social boundaries that regulate access to roles, resources, and rights-to-speak. These distinctions shape who is deemed suitable for front-stage representation (hosting, greeting, translation) and who remains in backstage coordination roles.

Indexicality clarifies how such eligibility becomes recognizable. Silverstein (2003) shows that indexes—dress cues, honorifics, accents, gestures, uniform colors, badges—signal social position and authorize or withhold voice in situ. Through indexical order, modest dress, soft tone, and uniformed hosting accumulate into an “authorization bundle” that grants women operational presence without necessarily conferring authorship or strategic control.

Sanction mechanisms ensure conformity. Classic anthropology highlights gossip, teasing, and ironic praise as low-cost means of policing moral boundaries (Gluckman, 1963). Contemporary status-construction theory adds that gender operates as a primary status frame: certain actors are presumed more competent for leadership tasks, while others are presumed supportive (Ridgeway, 2011). Violations of these expectations incur moral or reputational penalties.

Combined, boundary work, indexical cues, and sanction specify how performed respectability becomes recognized and regulated in daily tourism practice. These mechanisms constitute the second layer of the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model: the filtering of moral credit into conditional procedural authority.

3.4. Ideological–Material Relations in Barriteau’s Gender System

Eudine Barriteau’s gender system (1998) provides a structural lens for understanding the uneven conversion of moral legitimacy into organizational power in community-based tourism. She conceptualizes gender as an interlocking configuration of ideological relations—the norms and expectations defining proper femininity and masculinity—and material relations—access to resources, incomes, platforms, and decision-making authority.

This dual structure aligns closely with dynamics in Bang Rong. The ideological dimension corresponds to the community’s authorization stack of modest dress, uniformed hosting, calibrated tone, and kin-appropriate demeanor. The material dimension includes control over ledgers, schedules, rosters, budgets, digital platforms, and relationships with external partners. Ethnographic patterns reflect the interaction of these two dimensions:

- When ideological respectability aligns with material access, women convert moral credit into coordination authority (e.g., time-setting, flow management, payments).

- When ideological legitimacy is strong but material access is weak, conversion stalls, producing front-stage visibility without authorship.

- When material access outpaces ideological recognition, women face sanction and reputational policing.

Although other feminist approaches conceptualize empowerment through collective action, structural transformation, or resistance (Molyneux, 1985), Barriteau’s focus on how ideological norms and material arrangements co-produce everyday authority is particularly suited to explaining the micro-conversions observed in CBT settings. Her framework provides the third layer of the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model: the structural conditions that enable, constrain, or stall the translation of respectability into decision-making power.

Together, these strands of post-structural feminist scholarship anchor the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model that guides the analysis of Bang Rong. Skeggs and Butler clarify how women produce moral credit through performed respectability; Mahmood explains how disciplined modesty becomes a socially legible basis for authority; and Barriteau’s ideological–material lens specifies the structural conditions under which such credit can or cannot be converted into procedural or strategic power. This model directly frames the case study by offering a theoretical explanation for the central question of the article: how women’s authority in community-based tourism emerges through the situated conversion of respectability into organizational voice, and why this conversion remains partial, uneven, and class-differentiated within Bang Rong’s gender system.

4. Methodology

This study investigates how respectability and visibility are performed, recognized, and converted into authority in everyday community-based tourism. Because these dynamics are tacit, embodied, and situational, an ethnographic design was essential for capturing micro-performances, role-switching, and community surveillance. To analyze how such acts position women within Bang Rong’s gender system, I used Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse Analysis (FPDA), which examines how subjects are discursively produced through norms, shifting positions, and power effects. In line with FPDA, the analysis traced how women moved among multiple and sometimes contradictory subject positions depending on which discourse—religious, bureaucratic, or market-oriented—was activated (Baxter, 2008).

Rather than applying FPDA as a narrow coding device, the analysis drew on its core principles to trace a specific discursive chain: from meaning-making practices (“what counts”) to the subject positions they make available (“who she becomes”), to the semiotic and material carriers that sustain these positions (“what carries it”), and finally to the forms of authority or sanction they produce (“what it buys”). This chain served as the study’s principal analytic scaffold. A multi-source qualitative corpus—participant observation, semi-structured interviews, social-media interactions, and local documentary materials—supported this analysis.

4.1. Research Design, Sampling, and Data Sources

Sampling strategy

Seventeen semi-structured interviews were conducted using purposive maximum-variation sampling across the key axes shaping respectability and authority in Bang Rong: cohort (older/middle/younger), class (elite/non-elite), gender, and degree of CBT involvement. The sample consisted of seven core CBT women (hosts, coordinators, entrepreneurs), four core CBT men (leaders, brokers, mosque-adjacent actors), four non-CBT women working in domestic or market sectors, and two non-CBT men. A local female translator supported interviews conducted in Phuket dialect. This sample size is appropriate for in-depth ethnography because it achieved information saturation—no new themes appeared after the fifteenth interview—and it ensured coverage of all key role types within the community.

Ethnographic fieldwork and triangulation

Four months of immersive fieldwork (August–December 2024) provided access to the everyday enactment of modesty, authority, and sanction. Fieldwork combined:

- Front-stage participation (guiding, translation, visitor management).

- Backstage tasks (online shop support, accounting, report and training preparation).

- Domestic and informal interactions (home visits, shared meals, errands).

These observations were systematically linked to:

- Three years of social-media interaction data (LINE, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok) from nine key CBT actors.

- Local documentary materials (ledgers, rosters, receipt threads, program briefs).

- Visual/spatial documentation of uniforms, signage, and workstations.

Triangulation across interviews, offline practice, and online behavior allowed comparison between normative claims and lived enactments, revealing discrepancies such as differences between online and offline modesty performance. A concise description of the corpus remains in Appendix A.1.

4.2. Data Analysis

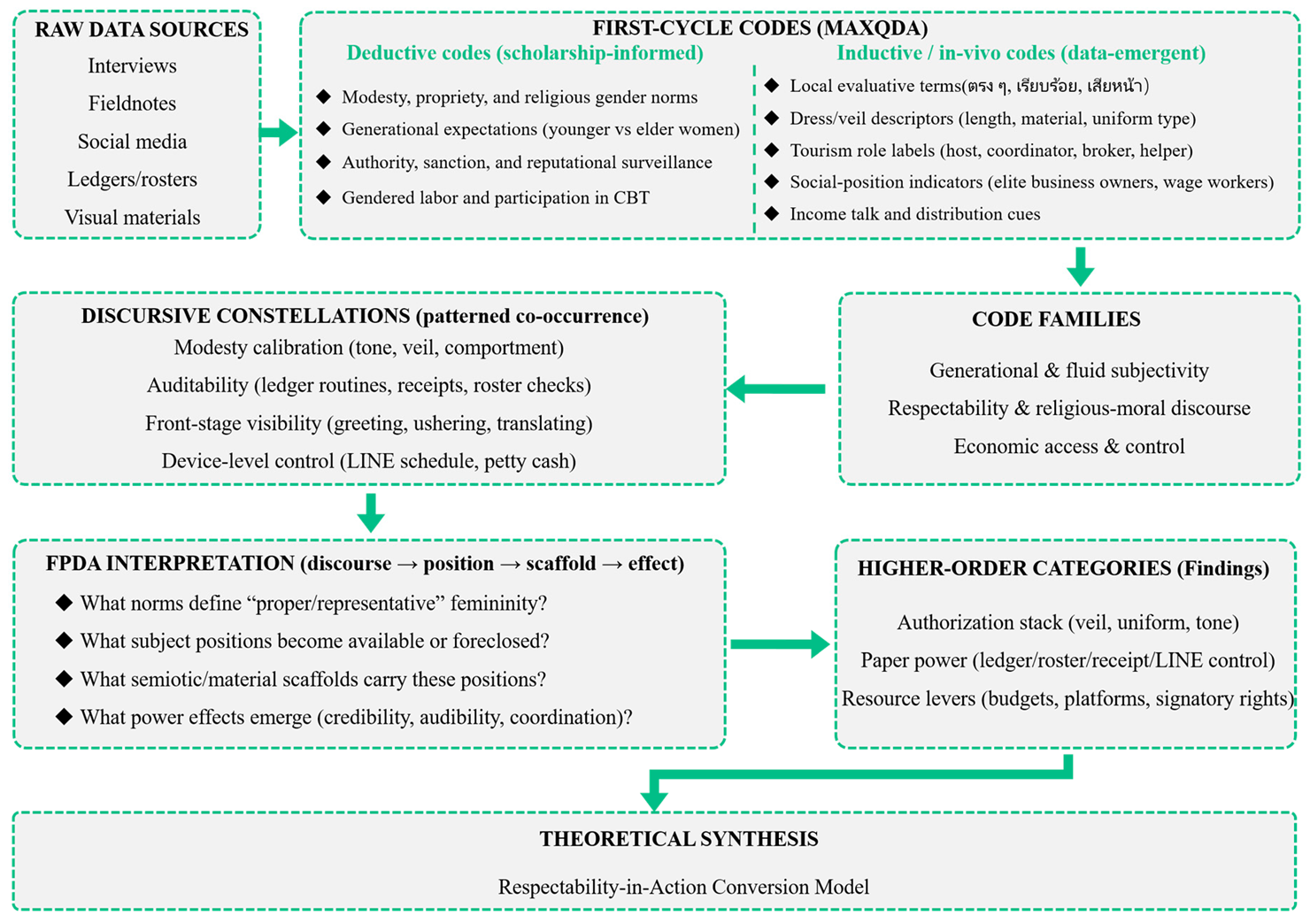

Data analysis proceeded in two linked cycles designed to ensure that higher-order categories—such as the authorization stack, paper power, and resource levers—were grounded in the empirical corpus rather than imposed.

First-cycle coding: deductive + inductive integration

In MAXQDA, I applied a blended coding strategy. Deductive codes, drawn from scholarship on feminist subjectivity, respectability politics, and gendered labor, included themes such as modesty and propriety, generational expectations, authority and sanction, and gendered divisions of CBT labor.

Alongside these, inductive and in vivo codes were developed from the data itself: local evaluative terms (e.g., “ตรง ๆ (direct/straightforward)”, “เรียบร้อย (proper, well-behaved)”, “เสียหน้า (to lose face)”), dress and veil descriptors, tourism role labels (host, helper, coordinator, broker), social-position markers (elite business owners, wage workers), and income-distribution cues. These codes captured how interlocutors themselves named, evaluated, and differentiated forms of femininity, work, and legitimacy.

Codes were then grouped into three families that recurred across the corpus:

- (1)

- Generational and fluid subjectivity;

- (2)

- Respectability and religious-moral discourse;

- (3)

- Economic access and control.

From codes to discursive constellations

To avoid analytic categories that merely mirrored theoretical expectations, I traced how codes clustered through co-occurrence across interviews, fieldnotes, LINE interactions, and documentary data. This process produced discursive constellations—recurrent patterned linkages that appeared even when data sources differed.

These included modesty calibration (tone, comportment, veil adjustments), auditability (ledger routines, receipt photos, roster checks), front-stage visibility (greeting, ushering, translating), and device-level control (final LINE schedule, petty cash, envelope reconciliation).

These constellations provided the empirical substrate from which interpretive categories were derived.

Second-cycle analysis: FPDA + episode matrices

Second-cycle analysis integrated materials into episode-level matrices mapping actors, settings, indexical cues, and outcomes. Building on FPDA, the analysis focused on:

- (1)

- Normative discourses defining “proper,” “modest,” or “representative” femininity.

- (2)

- Subject positions that were made available or withheld (e.g., “good representative,” “overstepping woman,” “trusted coordinator”).

- (3)

- Semiotic and material scaffolds—such as uniforms, tone, ledger books, rosters, and digital groups—that sustained these positions.

- (4)

- Power effects, including credibility, audibility, coordination rights, reputational sanction, and exclusion.

The FPDA chain (discourse → position → scaffold → effect) allowed systematic comparison of how modesty, paperwork, and resource access interacted across different scenes, producing different forms of authority or constraint.

Deriving higher-order categories

Only after these cycles did I synthesize higher-order interpretive categories: the authorization stack, paper power, and resource levers. These categories therefore represent analytical summaries of recurrent discursive constellations, not pre-determined typologies.

They provided the basis for the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, which was constructed from grounded patterns identifying how legitimacy becomes operational authority—and where this process stalls.

The full coding pathway and mini-coding pathway (3 Examples) are provided in Appendix A.2.

4.3. Reflexivity and Bias Mitigation

As a participant-observer, I adopted a reflexive stance throughout the fieldwork. As a male Chinese academic working in Thailand, my presence shaped interactions differently across cohorts: older women often performed heightened modesty in initial meetings, younger women treated me as a neutral confidant, and male leaders at times positioned me as an intermediary. These effects were documented in reflective fieldnotes and considered during analysis.

Triangulation across interviews, online–offline comparisons, and documentary evidence mitigated bias and strengthened interpretive reliability. Portions of translated fieldnotes and interview summaries were shared with two core interlocutors for limited member checking. All data were collected and stored in accordance with Thammasat University’s Social Science Ethics Board approval, with identifiers removed and visual data anonymized.

5. Findings

5.1. Generational and Fluid Gender Subjectivities

I treat feminine subjectivity as performed rather than possessed. Post-structural accounts read subject formation as discursively produced and reiterated in practice (de Beauvoir, 1949/1998; Butler, 1990/2006). Mahmood’s intervention matters in a Muslim CBT setting: ethical self-fashioning through modesty and discipline can be a mode of agency, not merely submission (Mahmood, 2009).

Here, feminine subjectivity denotes the discursively produced and affectively sustained ways of being a woman that become legible through embodied practices and can, under specific conditions, travel as power—as moral credit and procedural authority—without necessarily shifting strategic control. Operationally, “performing subjectivity” involves: (1) labels women enact (e.g., good mother, steward, brand ambassador); (2) embodied practices that make labels legible (veil/dress switches, tonal calibration, transparency rituals, platform work); and (3) affects that carry value (care, composure, diligence, piety).

Analytically I use FPDA to show how performances become legible and convertible, with generation and class shaping the exchange rate.

5.1.1. Repertoire

The repertoire summarizes patterned ways CBT renders femininity legible and usable in practice. Each role is grounded in repeated empirical pairings of labels and actions in the data—for example, “good mother” with set-up/clean and market stall work, or “good manager” with scheduling veto and ledger checking. These practices sit on specific carriers (ledgers/thresholds, rosters, uniforms, chat threads/phones, sites such as office, grove, pier). The Table 1 also includes a final column that offers my interpretive reading of the power effects attached to each pattern (moral credit, procedural authority, limits through gossip, audits, or male hand-offs).

Table 1.

Analytic summary of patterned performances of femininity observed in Bang Rong CBT (interpretive synthesis).

5.1.2. Three Vignettes

To illustrate how gendered subjectivities take shape in practice, this subsection presents three vignettes selected for their variation across cohort, class, and role. Each vignette draws on multiple sources (fieldnotes, interviews, meeting minutes, screenshots) and is followed by an FPDA snapshot linking patterning in speech, tone, and interaction to the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model.

Vignette 1—Woman F (Elder; Elite Receptionist/Mentor)

Woman F, recently elected president of the senior citizens’ club, carries both prestige and ambivalence. Her long career in provincial government makes her comfortable with officials, but inside the village she is sometimes regarded as “too Phuket Town.” This dynamic surfaced during preparations for the Pa Khao Pier Tourism Festival.

At a committee meeting behind the mosque she commented, using careful, formal Thai:

“Last year, Sophia’s food didn’t sell… maybe we should invite a few reliable Phuket Town vendors.”(Meeting minutes, 19 August 2024.)

The room fell quiet. A middle-aged woman looked down at her phone; two younger women exchanged glances. Afterward, Woman A whispered:

“She’s too polite… people think she looks down on them.”(Fieldnotes, 19 August 2024.)

Within two days, veiled Facebook posts appeared—

“Some people show off their cars like Phuket Town people,”

“If they love town so much, why stay in Pa Khao?”

(Facebook Groups, 21 August 2024)—an indirect sanction typical of village gossip.

When interviewed, Woman F offered a very different interpretation: “ฉันเป็นคนตรงไปตรงมา ผู้หญิงที่นี่ขาดความตรงไปตรงมา”—“I am a straightforward person; women here lack straightforwardness. “Her lexical choice, ตรงไปตรงมา (formal, bureaucratic register), lacked local softening particles (นะ, หน่อย). The absence of these markers produced declarative tone village women frequently interpret as aloof or superior.

Later in fieldwork, villagers gave contradictory assessments. After I interviewed Women F, Woman A quietly asked me: “Do you believe what she said about all the activities she joined? If it’s true, why doesn’t she take pictures?” (Fieldnotes, 9 September 2024).

Yet in an earlier interview, the same Woman A had praised her: “She is respectable… she knows how to communicate with outsiders and dresses very well. “My translator, Woman E, added another layer: “She is capable, but sometimes she doesn’t know how to do things—like desserts. No matter how you teach her, she can’t learn.”

These mixed assessments show that Woman F’s authority is situational: valued for external representation, questioned in everyday collaboration.

FPDA Snapshot

Norms invoked: Humility, collectivity, modest tone.

Self-positioning: “straightforward” → indexes bureaucratic/professional identity.

Community positioning: “too polite,” “looks down on people” → deviation from egalitarian norms.

Indexical cues: Formal Thai; no softeners; slow pacing; indirect Facebook sanction.

Effects: Procedural influence at the state–community boundary; fragile legitimacy in village settings.

Woman F’s tone, dress, and external networks grant her “safe” representational capacity with officials. Yet these same attributes expose her to moral scrutiny inside the village. Her authority is therefore segmented: strong at interfaces with government but constrained in internal decision-making. She illustrates how authorization and sanction can coexist, and how elite cultural capital converts only partially into strategic voice.

Vignette 2—Woman A (Middle Cohort; Administrator/Organizer, Audience-Indexed Communication)

By 8:30 a.m., the CBT LINE group was active: four visitor groups were arriving within two hours, two of them unannounced. At the farm office, Woman A balanced the ledger, coordinated vans, and reorganized staffing.

When thirty local students arrived, she tied on an apron and shifted to a warm, motherly persona, speaking in Phuket dialect: “Which is sweeter—our pineapples or the ones in town?”. The children laughed as she divided them into teams.

A second group—a delegation of mostly female northern Thai officials—arrived soon after. Here she adopted a different tone: calm, confident, professional. She described CBT as “women’s work”—mobilizing, scheduling, ensuring fairness—and used the ledger as a visual demonstration of accountability.

An international NGO team arrived next, overlapping with the northern group. Under strain, she offered a brief welcome and passed coordination to her son, muttering:

“It’s so hot… why did everyone choose today?”(Fieldnotes, 30 August 2024.)

Later, three women and a child requested a separate setup. At the time, Woman A did not know they were related to a senior southern tourism official. She looked startled but directed two boys to arrange a new table. The women made repeated requests (hot water, cushions). She later said:

“They were irritating… you just tell them we don’t have those fancy things.”(Field notes, 30 August 2024.)

Twenty minutes later, their relative—the delegation head—arrived, and her demeanor shifted again: warm toward the family, politely deferential toward him.

“Let Mr. A explain,” she said, stepping back.

FPDA Snapshot

- Norms invoked: Fairness, humility, respect for hierarchy.

- Positioning: Students → caring “mother/teacher”, Northern officials → competent peer coordinator, NGO team → overburdened organizer, VIP family → constrained service provider, Male leader → deferential representative.

- Indexical cues: Dialect shifts, tone changes, apron on/off, ledger visibility, deference forms.

- Effects: Strong procedural authority (scheduling, quality control), but strategic authority (pricing, representation) migrates upward to male brokers.

Woman A demonstrates high authorization-stack mastery—tone calibration, dialect shifts, modest presentation—and strong paper power. These allow her to run the day but not straightforwardly define its direction: on most occasions, her credibility converts into coordination power, while agenda-setting around prices, partnerships, and representation migrates upward to male brokers.

Yet this boundary is not rigid. In moments of operational urgency or where she has clear informational advantage—such as a temporary change to a bus route—she quietly overrides Man A’s suggestions in front of staff and he lets it pass. These small but telling episodes show that the line between “procedural” and “strategic” authority is negotiable rather than an impenetrable wall: her coordinating power can edge into decision-making when it can be framed as pragmatic adjustment rather than overt challenge.

Vignette 3—Woman B (Elite Entrepreneur; Contested Visibility)

During COVID-19 recovery, the mosque announced an entrepreneurship workshop for families who had lost income. Organizers proposed Woman B as a speaker because her family runs a well-known hotel and restaurant, and her grandfather had once been a mosque leader. Senior men immediately questioned her suitability.

She recalled: “Some elders didn’t like a woman speaking… especially one who doesn’t wear a veil.” (Interview, 8 October 2024). Several older women echoed these critiques to me, describing her as “too modern” or “not really Bang Rong.”

Despite this resistance, she accepted the invitation: “Of course I’ll go up and speak. I’ll say what I want to say.” (Interview, 8 October 2024.)

On the workshop day, the imam and several older veiled women sat in the back row. Woman B—unveiled—spoke for nearly 30 min about using land titles for financing, working with foreign operators, and selling online. At one point she emphasized: “I can’t speak for my husband; I run my own business.”

Afterward, young women lined up to ask questions about pricing and social media, and she began receiving LINE messages seeking further advice. In the following weeks she informally promoted several young women’s snacks at her restaurant. A mosque committee member later told me privately: “I also ask her to deal with the foreign operator—she understands their way.” (Fieldnotes, 18 October 2024.)

However, at a neighborhood cake shop, two non-elite women offered sharply different readings of her status: “Woman B is a bit stingy… she makes so much money but doesn’t donate much.” Like her mother—rich people are always stingy.” (Fieldnotes, 24 September 2024.)

One woman then added gossip about her family: “Her father used to be a drug addict and had other women in Phuket Town… I don’t know why he came back. Don’t tell anyone I told you that!”. These comments reveal how lineage talk, moral judgment, and rumor are mobilized to limit her legitimacy even as others rely on her market-facing skills.

FPDA Snapshot

Norms invoked: Modesty, lineage, representativeness.

Community positioning: “too modern,” “not from here,” “stingy,” lineage suspicion.

Self-positioning: Independent entrepreneur; landowner; market-competent.

Indexical cues: Confident tone; no veil; long, uninterrupted speech in mosque venue → interpreted as overstepping.

Effects: High symbolic capital with youth and external partners; reputational policing by elders; legitimacy grounded more in market networks than moral endorsement.

Woman B shows a reverse configuration to most women in the study: she has strong material and market resources but weak ideological authorization. Externally, her entrepreneurial capital and operator connections generate strategic value, and young women treat her as a model. Internally, however, her lack of veil, “urban” manner, and contested lineage invite sanction, gossip, and moral doubt. Read through the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, she illustrates how strategic influence can grow through external platforms even when internal moral authorization remains partial and politically fragile.

5.1.3. Cross-Case Synthesis

This subsection draws together patterns that recur across the vignettes and the wider coded corpus. Empirically, older, middle, and younger women occupy different mixes of service, coordination, and entrepreneurial roles. Interpretively, I read these patterned mixes as three broad trajectories within Bang Rong’s gendered tourism regime. These patterns appeared consistently across fieldnotes, interviews, and digital records.

Generations: stable rules, adaptable performances

Across cohorts, core respectability norms—care, ritual, piety, calibrated visibility—remain stable, but their enactment shifts with life stage. Older women build service-voice through routine, uniformed, prayer-timed tasks that generate reliability and moral credit but rarely access itinerary design or pricing. Middle-cohort women use ledgers, spend thresholds, rosters, and role/veil switches to convert respectability into coordination authority. Younger women foreground autonomy (education, side businesses, flexible gigs), achieving personal independence more often than collective influence.

Class: uneven travel of moral credit

Class shapes how far performances move along CBT’s pipeline (module → platform → market → agenda). Non-elite women gain reliable inclusion, small income, and symbolic credit, but remain contained to labor roles. Elite women link performances to ownership—private venues, land-backed credit, operator/media networks—extending respectability into external representation and, at times, enterprise-level strategy.

Other axes: modulators, not drivers

Marital status, education, childcare, and mosque proximity further nuance these trajectories. Marriage and childrearing limit availability and reinforce service-oriented roles. Education, urban experience, and multilingual competence broaden women’s eligibility for public-facing and operator-facing work. Proximity to mosque networks softens reputational sanction by embedding women within respected kin circuits. These axes modulate—but do not override—the core dynamic: authority advances when culturally credible subjectivity aligns with control of devices and resource levers, and stalls when either side is constrained.

Across cases, subjectivities become effective when they are legible: transparency rituals and audience-indexed modesty make propriety visible, yielding moral credit and limited procedural authority, while gossip and certification regulate the credible range and keep brokerage male-fronted. Taken together, the vignettes show three trajectories—service, coordination, and constrained autonomy—and set up Section 5.2, which traces how respectability is negotiated into power and where conversion stalls.

5.1.4. Male and Macro Authority Structures

“After Friday prayers, about ten middle-aged men sit in a coffee shop opposite the mosque. Man A lays out travel guides, price lists, and certification forms on the table and reports directly to the mosque leadership. Two women in black robes serve coffee but do not sit or speak. The discussion proceeds entirely among men.”(Fieldnote, 13–18 November 2024.)

The women’s trajectories described in earlier subsections unfold within this wider field of male-centered authority. Interviews and observations show that, in Bang Rong, men do not rely on modesty scripts to gain legitimacy. Instead, their authority is anchored in mosque visibility, ritual leadership, kinship seniority, and brokerage roles linking the community to state agencies, tourism operators, and Islamic institutions. These pathways place men in strategic positions—public representation, pricing negotiations, contractual partnerships, and microphone rights—without requiring the continuous moral calibration demanded of women.

At the same time, macro-structures reinforce this asymmetry. State programs, certification systems, and tourism markets typically coordinate with male brokers as “community leaders”; Islamic norms frame men as guardians of moral order and public voice; and royal network recognition flows disproportionately through male intermediaries. Foreign capital and investment dynamics further concentrate land-based bargaining power in male hands due to lineage patterns and perceived community protection roles.

Read through the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, these dynamics create a stable structural backdrop: women must continuously perform and audit respectability to convert moral credit into procedural authority, while men begin from positions already institutionally authorized for strategic decision-making. This helps explain why women’s trajectories tend to plateau at coordination power and why strategic authority remains selective, negotiated, and politically contingent.

A visual summary of how these macro-structures reinforce gendered asymmetry appears in Appendix A.3.

5.2. Performing Respectability and Negotiating Visibility

5.2.1. Respectability as Authorization: Front-Stage Presence

This section shows how veil, uniform, and tone operate as an “authorization stack” that licenses women’s public visibility in CBT while keeping authorship/agenda elsewhere. The term refers to a layered ensemble of visual and vocal cues—headscarf/veil, CBT vest or uniform, and a soft, deferential register—that women themselves adjust across settings. The analysis draws on FPDA and on work on respectability, front-stage performance, pious self-fashioning, and indexical order, but the components of the stack are derived from repeated observed pairings in the data.

Veil: the indexical anchor

In Bang Rong the headscarf is both an ethical practice and a public interface. For tourists, it stabilizes a recognizable “Muslim host” identity; for villagers, it buffers against gossip and sanction. Women adjust length, material, palette, and pairing to audience and venue—moving along a spectrum from maternal modesty to elite cultural ambassadorship. Figure 2 shows common headscarf styles in bang rong. These are not mere style choices; they are indexical operators that cue who may greet, narrate, or coordinate (Mahmood, 2009).

Figure 2.

Common Headscarf Styles in Bang Rong. (A) Long neutral headscarf used in markets, government offices, and formal events. (B) Black long headscarf worn in mosque or when hosting tourists from Muslim countries. (C) Short silk scarf for casual, hands-on work such as cooking or small-group hosting. (D) Patterned batik headscarf for VIP receptions, conferences, and special occasions.

The full set of observed adjustments—including five contrasting cases across school groups, foreign seniors, government officers, Bangkok promotional events, and small family groups—is presented in Appendix A.4.

Across these cases, veil choices are not merely stylistic but grounded in women’s own reasoning about audience, propriety, and reputational risk. In interview, Woman A explained the logics behind her adjustments:

“The rules here aren’t that strict… mostly I choose what feels comfortable that day.”(Interview, 11 September 2024.)

But this flexibility narrows in settings with higher scrutiny. Reflecting on attire for international conferences, she noted:

“Batik—especially the pineapple pattern—shows Phuket culture. And a long veil tells them I’m Muslim.”(Field notes, 28 September 2024.)

In contrast, she described the market as a space of acute reputational surveillance:

“There are many people and a lot of gossip at the market. If I wear only a short veil, they will talk about my husband… I don’t want him to lose face.”(Interview, 12 September 2024.)

These excerpts illustrate the indexical layering of the authorization stack: long, dark veils secure moral protection in high-gossip environments; lighter or patterned veils index modern professionalism for female-official groups; fine batik and silk signal elite representativeness in promotional settings. The veil thus synchronizes two publics at once—tourists and villagers—authorizing presence while circumscribing authorship.

Uniform: organizational cover, not a claim

At Bang Rong CBT, the uniform—a short-sleeved logo shirt (including the 2025 blue “pineapple-field” variant)—functions as organizational cover, not a claim to leadership. Like the veil, it is part of the authorization stack: it bureaucratizes women’s presence (“I speak for CBT, not myself”), licensing hosting and coordination while pricing, partnerships, and microphones remain male-fronted. Two patterns recur in fieldwork:

Selective adoption

Uniforms appear mainly on VIP or large-group days and are often paired with aprons. Leaders frequently opt out. In a 2024 delegation visit, all service staff wore uniforms, while Man A wore formal attire and Woman A wore a tailored blouse (Figure 3). As one woman explained:

Figure 3.

Group photo of all members of Bang Rong CBT receiving foreign delegations in 2024.

“If I wear the shirt, people know I’m working for the community and family”(Woman C, interview, 14 October 2024.)

Gendered exit

Because the uniforms were too masculine and not very attractive, the women would immediately take them off after the event.

“People gossip… better to change quickly.”(Woman G, fieldnotes, 11 September 2024.)

Young men often remained in uniform longer, reinforcing public assumptions that they “own” operational authority.

Mixed-group asymmetry

FPDA Snapshot

Norm: Modesty; collective duty.

Position: Uniformed = staff/volunteer; non-uniformed = host/planner.

Indexical: Logo shirt, apron on/off, removal timing, contrast with leaders’ attire.

Effect: Procedural clearance to host/coordinate; strategic decisions remain elsewhere.

Read with Goffman and Butler, the uniform is a front-stage costume that sediments a service identity through repetition. Its value is real—organizational cover authorizes reception and flow-keeping—but its selective, event-bound use both signals and re-produces hierarchy: uniforms travel with procedural work; non-uniformed attire ac-companies representation. In the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model, the uniform strengthens women’s legitimacy for procedural work but visually marks the boundary between service and strategy—reinforcing how respectability authorizes coordination yet rarely converts into agenda-setting authority.

Tone: the final-mile scaffold

Because of language asymmetries, not all women engage tourists directly; still, where hosting occurs, register—soft volume, hedges, honorifics, dialect choice—acts as the final authorizer. Tone “keys” the role (Goffman, 1959/1971); repeated softeners sediment modest femininity (Butler, 1990/2006); and breaches attract gossip/corrective takeover (Gluckman, 1963).

Across interactions, tone operates as the final “key” that stabilizes women’s legitimacy. With male leaders, women soften register and hand authority upward—“Let Man A explain” (Fieldnotes, 30 August 2024). With female officials, tone shifts into confident, collegial warmth that enables smooth coordination. In low-stakes encounters, women keep speech minimal and procedural, signaling that no higher-level representation is required. Multilingual switches (Thai–English) broaden communication but do not alter the hierarchical reading of their voice, which remains coded as service rather than strategy.

Tone also enables veiled critique. Humor and irony let women express dissent without breaching modesty norms. Discussing a religious leader’s inconsistency, Woman A laughed:

“เขาบอกว่าอย่าทำบุญวัดพุทธ… แต่เขากินเหล้าเงียบ ๆ แกงหม้อใหญ่เลยนะ” (khao bok wa ya tham-bun wat phut… tae khao kin lao ngiap ๆ, gaeng mor yai loei na)

“He told me not to donate to Buddhist temples… but he secretly drinks—a whole big pot of stew, right?”

The idiom แกงหม้อใหญ่ (gaeng mor yai, “big pot of stew”) humorously flags contradiction; the particle นะ (na) softens stance and keeps the critique socially safe.

Across these moments, Woman A uses intonation, slang, particles, and humorous framing to convert critique into socially acceptable commentary, maintaining modest femininity while signaling awareness of hypocrisy and double standards.

FPDA Snapshot

Norms invoked: Modesty, deference, harmony.

Self-positioning: Softly humorous insider; “good representative” who critiques without confrontation.

Community positioning: Elders/leaders framed as inconsistent or performative, but only through coded humor.

Indexical cues: Laughter; idiomatic teasing (แกงหม้อใหญ่); softening particles (นะ); playful tone → reduce face-threat and keep critique indirect.

Effects: Hosting and coordination remain authorized; critique becomes possible only through softened, coded speech rather than explicit challenge.

In combination, veil–uniform–tone translate moral legibility into procedural authority: women can greet and narrate, smooth flows, allocate helpers, and coordinate rosters or small budgets. The same stack also inscribes limits—it codes voice as care/service rather than command and pre-authorizes hand-offs at strategic thresholds (pricing, partnerships, public microphones).

Respectability in Bang Rong is not merely displayed; it is calibrated and carried through concrete devices (veil styles, uniforms, tonal registers). This authorization stack makes women’s visibility morally secure and institutionally legible, reliably purchasing process power—and just as reliably stopping at strategy. Section 5.2.2 Paper Power shows how ledgers, receipts, LINE updates, and rosters operationalize that process power in day-to-day coordination—“the hand that closes the ledger sets the day”—and where conversion still breaks.

5.2.2. Paper Power: The Hand That Closes the Ledger Sets the Day

In this study, paper power refers to women’s control over the device-level routines that make daily CBT work auditable—ledgers, rosters, receipts, LINE posts. This control allows women to determine how the day runs (payments, timings, staffing), but not what the day should be (prices, partnerships, contracts), which remain tied to higher-level resource levers such as budget discretion, platform access, and signatory rights.

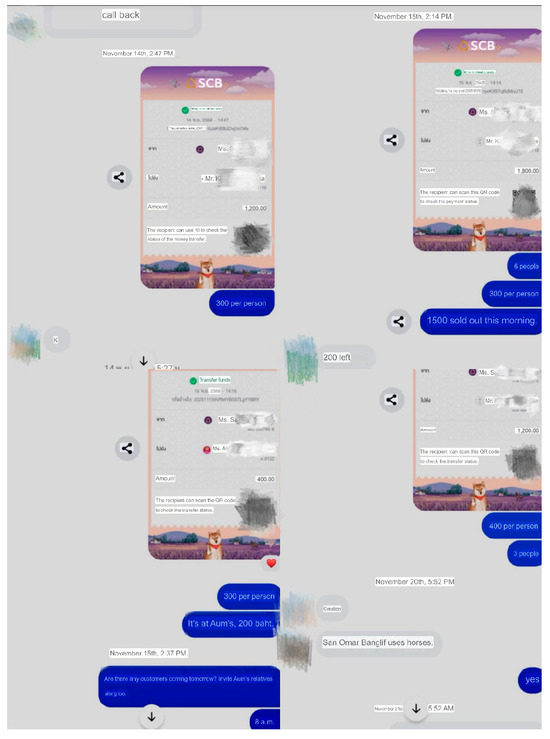

In Bang Rong, financial stewardship is a public test of respectability. The domestic repertoire—keeping accounts, reporting expenditures, guarding the purse—travels into CBT as a codified practice that both authorizes presence and cultivates subjectivity. Since the 2021 re-organization under Man A and Woman A, day-to-day money work has shifted from committee minutes to a device ecology managed by Woman A (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Transfer records (Translated Vision), 14–20 November. After the activity, Woman A transferred wages (400 THB/200 THB per worker) from her personal account to Man B and Woman G, who then distributed the payments to the rest of the team. She explained that paying everyone directly would be slow and risk mistakes; delegating distribution to trusted intermediaries was “easier and faster for many people”.

- Intake and storage. Client transfers arrive in a bank account under Man A’s name; cash is pooled by Woman A in red envelopes.

- Recording. Household and CBT ledgers, together with receipt bundles and LINE photo-receipts, make inflows and outflows traceable.

- Disbursement. Workers are paid daily from the envelope or via transfer. Expenses <5000 THB are executed unilaterally; ≥5000 THB require joint discussion but are usually paid by her.

These transfers illustrate the core mechanism of paper power: Woman A remains the nodal point for receiving funds, allocating amounts, and initiating payouts, even when actual distribution is delegated.

Through these routines, moral credibility becomes allocative practice: Woman A sequences payments, prioritizes purchases, and effectively closes the day. Her own gloss captures this conversion: “I manage the funds… I have the final say.” Woman A Interview 8, September 2024.

FPDA Snapshot: Norm (respectable stewardship) → Position (“trusted coordinator”) → Scaffolds (ledger, envelope, receipts, transfer records) → Effect (allocative control; managerial subjectivity).

Cross the 57 paper-related actions recorded in my fieldnotes (August–December 2024), women performed almost all device-level tasks. All 15 ledger pages and all receipt bundle I documented during observation periods were compiled by women, and 30 of 38 daily payouts were executed by women (based on contemporaneous transfer logs and envelope-distribution notes). By contrast, price and partnership announcements—identified through LINE operator threads and meeting minutes—were largely male (8 of 11 announcements).

These tallies were reconstructed from fieldnotes, real-time message logs, and role-allocation records, which cannot be reproduced in full due to confidentiality restrictions but are fully documented in the analytic audit trail. Everyday practices that constitute this device-level control are illustrated in Figure 5, which shows how women record, post, and coordinate CBT operations through ledgers and digital documentation. Together, they show a consistent pattern: women control the routines that make money and time auditable, while men appear more frequently in outward-facing, and announcement roles (For action tallies, see Appendix A.5).

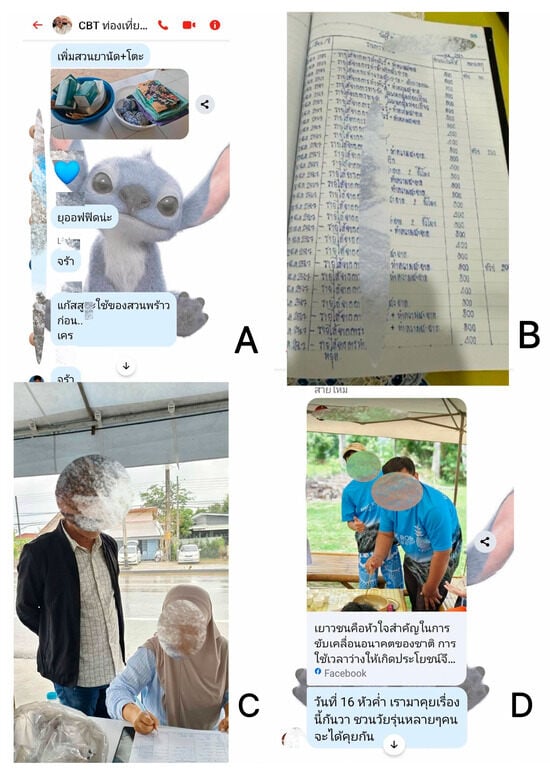

Figure 5.

Everyday Practices of Paper Power in Bang Rong CBT. (A) Woman C posts the day’s preparation tasks in the CBT Facebook group. Her message reads: “We have an activity tomorrow—everyone please prepare the items listed here.” Through such posts, routine labor becomes visible and auditable to members.(B) Woman A’s CBT ledger, recording daily income and expenditures in handwritten form. (C) During a donation ceremony, Woman A registers amount and signs her name, performing accountable stewardship in public view. (D) Woman A convenes members through a Facebook announcement reading: “Please come help today—there is a lot of work. “These digital messages coordinate schedules and allocate responsibilities in real time.

Alongside these routines sits the second layer that ultimately caps or extends paper power: resource levers, defined as the rights-bearing capacities attached to a person’s name. In Bang Rong, these resource levers—budget discretion, roster/platform control, platforms external channel, and signatory rights—set the ceiling of paper power. Table 2 specifies each lever with operational indicators and field evidence.

Table 2.

Resource levers and field evidence (August–December 2024).

These levers establish the ceiling of paper power. Two brief scenes show where that ceiling holds.

Scene 1: Borrowing for the regional expo (September 2024).

When CBT sought funds for exhibition costs in Singapore/Malaysia, Man A proposed borrowing from a wealthy CBT ally in Phuket Town. Yet it was Woman A who was tasked with the request. The allied leader later phoned me privately to verify intentions: “Why isn’t Man A coming in person? Is Woman A using this for her family?” He ultimately refused. The reputational cost fell on her; Man A’s relationship remained intact. Without signatory legitimacy, her allocative authority does not shield her from suspicion.

Scene 2: Planning the organic farmland module (August–November 2024).

During planning meetings at the new farmland, Man A outlined strategic components—crop choices, marketing, operator interest—while Woman A, though present, confined her contributions to logistics: worker numbers, payment timing. When asked why she did not comment on strategic issues, she responded: “I don’t know much about agriculture… I just make sure everything is right.” Her operational competence did not translate into authorship.

These scenes show how the absence of resource levers—notably signatory rights and external platform control—limits women’s strategic influence and exposes them to disproportionate reputational risk.

In sum, paper power turns respectability into action: ledgers, envelopes, receipts, and LINE posts make work auditable and cultivate a recognizable managerial subjectivity—prudent, timely, accountable. But without resource levers—account ownership, platform control, signatory rights—this coordination power remains bounded. Women become the muscle of implementation while authorship stays elsewhere, producing a patterned divide between process power and strategy power that Section 5.2.3 examines in practice.

5.2.3. How Authorization Stacks Meet Resource Positions in Practice

This subsection steps back from individual scenes to map how the observed stacks and resource positions combine across cases. The previous sections showed how women perform respectability through veil choices, uniform calibration, and tone management, and how these semiotic practices authorize their front-stage presence. This subsection examines how these ideological performances interact with material positions—control of devices, budgets, schedules, and platforms—to shape women’s actual roles in Bang Rong’s CBT.

In practice, women’s trajectories cluster around the alignment or misalignment of these two domains. When women perform strong authorization but lack access to organizational devices or external-facing responsibilities, their participation stabilizes as service visibility: they host, usher, translate, or assist, but do not sequence the work of others. Women D and G exemplify this pattern. Their interactions display impeccable modesty and soft tone, yet without control over cash, rosters, or LINE threads, they remain confined to day-rate service roles. Woman D summarized her role as “ช่วยทุกอย่าง แต่ไม่ต้องคิดเรื่องใหญ่” (“I help with everything, but I don’t have to think about big matters,” interview, 11 October 2024).

Where authorization combines with everyday device control, women gain coordination power. Woman A’s case demonstrates how the ability to close ledgers, reconcile envelopes, and issue final schedules turns respectability into allocative authority. Through routine posting, recording, and staff assignment, she “runs the day,” even as prices, partnerships, and public microphones remain elsewhere.

Women who depart modesty scripts but hold valuable sectoral or linguistic resources occupy a zone of contested coordination. Woman E, with strong English and operator links, reliably designs products and liaises with visitors, yet reputational talk about her remarriage and houseboat narrows her credible range. Woman C’s LGBTQ identity is buffered by kinship networks and caregiving reputation, allowing her to coordinate kitchen flows, but her legitimacy remains negotiable.

Finally, low conformity combined with low resources produces marginalized participation. A gender-nonconforming teenage helper, despite initial inclusion, attracted gossip for dress and demeanor, eventually self-withdrawing from visible tasks. Without the scaffolds of modest tone, kinship buffers, or device access, their presence became socially unsustainable.

Across cases, the empirical pattern is clear: respectability authorizes presence, but material access determines reach. Stacks without resources yield stable service; stacks plus device control produce coordination; resources without stacks generate contested authority; and the absence of both precipitates exit.

5.2.4. Pathways, Conditions, and Blockages in Bang Rong

These patterns produce two common movement pathways—and predictable points of failure—within Bang Rong’s CBT.

Pathway 1: Service → Coordination (frequent)

Women move from service roles into coordination when their authorization stack is paired with control of at least one everyday device. Issuing the final LINE schedule, updating the roster, reconciling envelopes, or approving small purchases gradually builds a record of dependable stewardship. Over time, these practices are read by others as evidence of fairness and competence, allowing women to orchestrate timings, allocate labor, and manage daily expenditures.

However, this progression is easily disrupted. Ledger and envelope control concentrated in a single administrator restricts opportunities for others to build comparable audit trails. When men “counter-post” by relabeling women’s updates as drafts, women’s authorship is symbolically downgraded. In addition, low or unstable compensation for coordination tasks makes the role unattractive relative to private gig income, limiting the pool of women willing to take on these responsibilities. As Woman G said when asked if she wanted to help Woman A manage CBT: “No, I don’t want to; I want to manage my own business.” (Woman G interview, 23 October 2024).

Pathway 2: Coordination → Autonomy (rare)

Movement from allocative coordination to strategic autonomy requires more than paper power. Women need resource levers: direct authority over budgets, control over external-facing platforms, or signatory rights that allow them to formalize decisions in their own names. They must also have buffers that protect them from takeover or sanction—male allies, committee endorsement, or external mandates that legitimize their leadership.

Indicators of autonomy include setting price points, managing operator relations without hand-off, or appearing as the legal signatory on contracts or invoices. These situations occurred in only a handful of cases. Woman B occasionally negotiated with operators and set pricing for products she owned, but her autonomy was anchored in private assets rather than communal endorsement. Others, despite strong coordination abilities, never crossed into agenda-setting because contracts, budgets, and public representation remained bundled with male brokers or mosque-linked leaders.

Local thresholds constrain this pathway. Pricing and partnership talk routinely recenters men at mosque–state interfaces. Women who speak assertively risk modesty sanctions that narrow their credible range. Without signatory rights, even those who “run the day” remain procedurally powerful but strategically dependent. Where external partners prefer male interlocutors, women’s coordination roles plateau regardless of competence.

Across both pathways, Bang Rong’s pattern is consistent: respectability enables participation, paper power stabilizes coordination, and resource levers determine whether coordination can ever become authorship.

Where stacks and resources align, women consolidate meaningful authority; where they diverge, reputational policing, counter-posting, and institutional filters reassert the strategic ceiling.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model (After Barriteau)

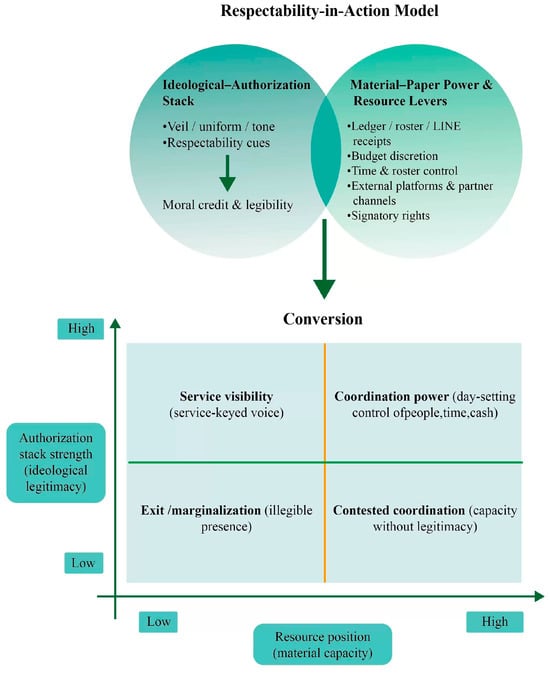

Building on Barriteau’s distinction between ideological formations and material arrangements, the findings point to a dynamic conversion process rather than two parallel domains. We call this mechanism the Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model.

At its core, the model explains how gendered respectability—performed through culturally legible scripts—can be converted into varying degrees of authority, and why this conversion often plateaus before reaching strategic power.

Ideological formation: the authorization stack

The authorization stack refers to the ensemble of semiotic cues—veil calibrations, uniform choices, tonal softeners, front-stage comportment—through which women enact morally credible subjectivity. These cues are continually audited by community members and external audiences, generating moral credibility and procedural legibility. Ideologically, the stack positions women as trustworthy custodians of interactional order.

Material arrangement: paper power and resource levers

Material arrangements operate through two interlinked layers.

- Paper power is the operational hinge: control over account books, rosters, receipts, and LINE groups that make daily action auditable. This layer enables the distribution of time, labor, and cash.

- Resource levers constitute the institutional layer: budget discretion, roster-setting rights, access to external platforms, and—rarely—signatory authority. These levers determine whether procedural influence can be extended into agenda setting.

Conversion outcomes

Alignments and misalignments between these two formations create four patterned outcomes across community-based tourism settings:

- Strong stack × low resources → service visibility. Respectability authorizes presence but does not travel beyond front-stage service roles.

- Strong stack × high resources → coordination power. Paper power and resource access allow women to orchestrate daily flows of people, time, and expenditures.

- Weak stack × low resources → marginalization/exit. Illegible or non-normative performances attract soft sanctions, narrowing opportunities for meaningful participation.

- Weak stack × high resources → contested coordination. Competence and network capital may expand scope, but legitimacy remains fragile and open to reputational policing.

Modulators of conversion

The trajectory and outcome of this conversion are modulated by local demographic and social logics. Middle-aged women often move more easily into coordination roles due to seniority norms; young women may be viewed as insufficiently communal; elite women can secure partial autonomy through assets and external ties but attract moralized scrutiny when departing modesty norms; non-elite women with paper power remain answerable without buffers of savings or endorsements.

Implications

The model shows that durable empowerment in CBT hinges less on generic “participation” than on the efficient conversion of legitimacy into allocative discretion. Where legitimacy and resource access move together, authority consolidates; where they diverge, soft sanctions, counter-posting, and institutional filters re-stabilize the strategic ceiling.

The underlying mechanism—the alignment of culturally credible subjectivity with control of organizational devices—may be portable across CBT settings. What varies is the symbolic form that legitimacy takes: Islamic modesty in Bang Rong, professional etiquette in non-Muslim communities, or customer-service scripts in market-driven contexts. Across these different environments, strategic authority emerges only when ideological credibility and material leverage operate in tandem.

6.2. Governance Recommendation for Small-Island CBT (SIDS-Relevant)

Although Phuket is not formally a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), Bang Rong exhibits similar conditions: narrow economic bases, environmental exposure, and reliance on a small set of intermediaries (Sarmento, 2024). These conditions make them vulnerable to organizational capture and place women at a disadvantage in decision-making structures. The findings of this study point to governance practices that may support gender-equitable coordination in similar CBT settings.

A. Strengthening Women’s Procedural Legitimacy

At many small-island CBT sites, women already perform most of the front-stage labor, yet their authority remains informal. Formalizing this labor helps convert respectability into recognized responsibility—a pattern documented at community tourism sites in Fiji, Samoa, and northern Thailand (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., 2013; Hampton & Jeyacheya, 2020). Policy pathways:

- Provide written role recognitions or appointment notes for women who coordinate visitor flows, host, or translate.

- Include women in routine public-facing communication—welcome remarks, itinerary briefings, daily updates—to institutionalize their procedural voice.

These measures may help translate socially acknowledged respectability into organizational legitimacy.

B. Distributing Administrative and Financial Levers

The findings show that women achieve authority when access to resources—petty cash, rosters, digital groups, and documents—is broadened rather than concentrated. Broadening resource control—such as rotating roster/LINE access, petty-cash rights, and platform postings—has been shown to strengthen women’s authority in CBT settings (Vujko et al., 2024; Promburom, 2022). Policy pathways:

- Introduce rotating control of small petty-cash budgets and roster editing.

- Standardize procedures for posting schedules, closing ledgers, and documenting expenses.

- Name operational female coordinators as official counterparts in partner contracts and communications.

Such distributive mechanisms may enable women to convert ideological legitimacy into coordination authority.

C. Building Institutional Safeguards Against Capture

Durable empowerment requires protection against the re-centralization of power. Mixed-gender oversight bodies, open financial reporting, and term limits have improved governance in small-island tourism across the Pacific and Indian Ocean (Hampton & Jeyacheya, 2020; Biddulph & Scheyvens, 2018). Policy pathways:

- Establish gender-balanced CBT committees with term limits and clear mandates.

- Publish quarterly financial summaries and keep a shared contract register.

- Rotate control of communication and coordination tools (ledger, roster, messaging groups) and require transparent handovers.

- Develop mentorship pathways pairing senior women with younger or non-elite women to sustain succession and skills transfer.

These measures may help reduce governance risk and ensure that authority does not re-consolidate within a small male-brokered network.

6.3. Conclusions

This study has shown that women’s authority in Bang Rong’s community-based tourism does not arise simply from participation but from the situated conversion of cultural legitimacy into organizational power. By examining how modesty norms, reputational surveillance, and device-level coordination intersect, the analysis demonstrates that authority in CBT is assembled through everyday practices rather than formal mandates. The Respectability-in-Action Conversion Model clarifies this dynamic by identifying when performed respectability becomes procedurally consequential and where conversion stalls, reframing empowerment as a contingent process rather than an automatic outcome of participation.

The findings address a key gap in CBT scholarship by specifying the meso-level mechanisms linking gendered moral orders with control of material devices. Women advance when culturally credible subjectivities align with access to paperwork, platforms, and routines that structure daily operations, whereas strategic authority remains limited when rights-bearing tools—signatory power, budget discretion, platform control—are concentrated in male-brokered networks. These insights suggest context-specific governance implications for small-island CBT systems: institutional changes that distribute administrative devices, formalize procedural responsibilities, and prevent organizational capture may broaden women’s roles.

Beyond the empirical case, the Respectability-in-Action approach offers a situated analytic lens rather than a universal model for examining how legitimacy and resources interact to shape gendered authority in community-based tourism. By specifying the alignment required between legitimacy regimes and organizational devices, the model provides a meso-level mechanism that bridges feminist theories of subject formation with tourism governance scholarship. Its core logic may be relevant across diverse contexts—Muslim and non-Muslim, island and mainland—even as symbolic forms of legitimacy (e.g., Islamic modesty, professionalism, cosmopolitan capital) vary. Future research should test this portability and examine how such alternative legitimacy regimes shape the conversion process. Ultimately, by reframing empowerment as a dynamic and culturally mediated form of authority conversion, this study contributes a contextually grounded perspective for analyzing gendered power across community tourism settings in the Global South.

6.4. Limitations