Abstract

Cultural landscapes are facing increasing challenges in terms of sustainable financing, owing to fiscal austerity and limited public funding. This study explores tourists’ willingness to pay (WTP) for the conservation of cultural landscapes through Japan’s Furusato Nozei (Tax payment to hometown)—a policy that pairs tax deductions with tangible “return gifts,” institutionalising a form of mixed (or “impure”) altruism that can convert intention into action. Using a survey of 500 visitors to Shibamata, Tokyo, we estimate an integrative model that links psychological pathways (motivation → destination evaluation), behavioural investments (time, spending, and interactions with residents), and socio-demographic characteristics. To analyse the collected data, we use partial least squares structural equation modelling. Results reveal that interaction with local communities has the strongest direct effects on WTP, while motivation influences WTP indirectly through destination evaluation. Age shows a negative relationship, whereas marital status has a positive one; income and gender are not significant predictors. These findings suggest that institutional incentives embedded in Furusato Nozei can transform altruistic intention into actual financial support for heritage conservation. This study contributes theoretically by linking institutional design to behavioural intention–action gaps and practically by providing insights for participatory and incentive-based heritage financing. The findings are based on a single-site case in Shibamata, Tokyo, and should therefore be interpreted within its local and cultural context.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Financial Crisis of Cultural Landscape

In this era of fiscal austerity and constrained public funding, a fundamental question arises: how can cultural landscapes establish sustainable financing mechanisms to ensure long-term conservation and development? Cultural landscapes—a significant category of World Heritage sites—reflect the unique production systems, customs, and cultural traditions of a region, encompassing tangible and intangible values (Rössler, 2006). Compared with singular architectural heritage, maintaining cultural landscapes often requires larger-scale and continuous investments to support routine upkeep, restoration, and infrastructure improvements (Guzmán et al., 2017). As these landscapes rely primarily on public funding and government support (Salpina et al., 2025), many heritage sites face financial shortfalls under fiscal constraints (Darlow et al., 2012). Cases such as the Cinque Terre in Italy illustrate the risks of landscape deterioration due to funding shortages and labour outmigration (Agnoletti et al., 2019). While tourism can revitalise certain landscapes—for example, heritage tourism in vineyard regions has promoted sustainable development (Ruiz Pulpón & Cañizares Ruiz, 2019)—tourism revenues alone often cover only a fraction of the conservation costs. Without innovative and stable funding channels, financial gaps jeopardise the physical integrity of cultural landscapes and undermine their contributions to tourism, community cohesion, and ecosystem services (Guzmán et al., 2017). Therefore, developing sustainable financing solutions, alongside broader public engagement, is an urgent priority for the long-term preservation and development of cultural landscapes (Salpina et al., 2025).

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Willingness-to-Pay Approaches

To address fiscal challenges and compensate for insufficient public funding, academic research and policy practice have widely employed the concept of willingness to pay (WTP) to quantify the economic contributions the public and tourists are willing to make to heritage conservation (Hanemann, 1991; Mitchell & Carson, 2013). Tourists are willing to pay for the development of cultural landscapes, heritage preservation, or improvements to cultural environments (Abuamoud, 2025; Batool et al., 2025; Cong et al., 2019; H. Li et al., 2023; Maeer et al., 2008; Quiroga, 2025). Researcher found that UK tourists were willing to support heritage conservation through admission fees (Moran, 2002); Alberini and Longo reported that Italian citizens were willing to pay additional taxes for the improvement of Venice’s cultural environment (Alberini & Longo, 2006). Bedate found that Spanish tourists expressed a clear willingness to pay for the restoration of archaeological sites (Bedate et al., 2009). Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of public contributions to support cultural landscape protection.

However, the existing WTP research has two major limitations. First, many studies remain at the intention level without examining the mechanisms that convert stated willingness into actual behaviour, reflecting the well-documented intention–behaviour gap (Ajzen, 1991; Sheeran & Webb, 2016). According to the theory of planned behaviour, intentions typically explain only a fraction of actual behaviour (often less than 30%), and self-interested motives tend to dominate when trade-offs are considered (Sheeran & Webb, 2016). In the absence of immediate incentives or reminders, intended contributions may fail to materialise (Conner & Norman, 2022). Second, traditional WTP formats are predominantly purely altruistic donations, which are often one-off or sporadic, lacking continuity and institutionalised mechanisms to generate stable funding streams (Jelinčić & Šveb, 2021; Lupu & Allegro, 2024). Therefore, these structural weaknesses highlight the need for mechanisms that not only encourage willingness but also institutionalise behavioural commitment.

1.3. Furusato Nozei: An Institutional Innovation for Sustainable Landscape Financing

To address this gap, Japan’s Furusato Nozei (Hometown Tax) system provides a compelling institutional model that bridges personal incentives with public benefits. Introduced in 2008, this programme allows taxpayers to select their preferred local municipalities for contributions, accompanied by tax deductions and, in many cases, material ‘return gifts’ (Hasegawa, 2017; Rausch, 2019). Funds raised through Furusato Nozei can be directly allocated by local governments to the protection, restoration, and maintenance of cultural landscapes and heritage, as well as to activities that support traditional culture and educational programmes (Donation to Municipality Produced by Furusato Choice, n.d.; Fukasawa et al., 2020). In practice, the programme has provided critical financial support for numerous community-based cultural landscape projects while revitalising local economies and enhancing regional branding (H. Li et al., 2024; Shimauchi et al., 2019). For instance, Nara Prefecture utilised Furusato Nozei contributions to restore sections of World Heritage temples (H. Li et al., 2024), while Inuyama City used the Furusato tax to preserve and restore its Edo-era castle town, aiming to attract tourists and boost the local economy (Toyoshima et al., 2024).

Unlike conventional donations (Aseres & Sira, 2020), the system combines private incentives (return gifts) with public contributions (cultural landscape conservation) to reflect the concept of institutionalised impure altruism (Hasegawa, 2017; Rausch, 2019). Through this design, individuals gain a ‘warm-glow’ psychological reward and tangible benefits, substantially enhancing participation feasibility and attractiveness (Andreoni, 1989, 1990). By institutionalising these incentives, Furusato Nozei provides a sustainable funding mechanism that supports the long-term preservation of cultural landscapes (Ajzen, 1991; Leonard, 2008; Sheeran & Webb, 2016). Nevertheless, while the system provides an innovative framework for mobilising private resources, its broader applicability remains uncertain. Tourism-dependent municipalities, for example, continue to face structural fiscal pressures and unequal donor distribution (Hasegawa, 2017). Moreover, comparative research on similar schemes abroad—such as the UK’s National Lottery Heritage Fund (National Lottery Heritage Fund, 2018) or Korea’s Hometown Love Donation System (Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, n.d.)—remains limited, cautioning against direct generalisation of the Japanese model without contextual adaptation.

1.4. Research Objectives and Contributions

Despite the growing recognition of its significance, empirical research on the programme within the context of cultural landscape conservation remains limited, particularly from the perspective of tourists as contributors and regarding the determinants of their WTP (Aseres & Sira, 2020; Wang & Ya, 2023; Witt, 2019). Building on the aforementioned context, this study examines the influence of tourists’ WTP for cultural landscape conservation through Furusato Nozei. To this end, a comprehensive conceptual framework is proposed, integrating three key dimensions: psychological mechanisms (motivation and destination evaluation), behavioural investment (social interactions, time, and monetary expenditure), and demographic conditions (e.g., income and age). This framework enables an analysis of how these factors influence tourists’ WTP for Furusato Nozei contributions.

This study makes three principal contributions to the literature. First, it advances theoretical understanding by incorporating the concepts of institutionalised impure altruism and the intention–behaviour gap into cultural landscape research, demonstrating how institutional design can mediate the translation of willingness into action. Second, from an empirical standpoint, it provides one of the first quantitative assessments focusing on tourists as external yet essential stakeholders in heritage financing—an aspect often overlooked in existing research. Third, at the policy level, the findings generate actionable insights for designing incentive-based contribution systems that enhance funding sustainability while recognising real-world economic and administrative constraints. Importantly, rather than uncritically promoting the Japanese model, this study situates Furusato Nozei within a broader comparative perspective, outlining both its potential and its context-specific limitations for cultural landscape governance.

2. Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Basis

Tourists’ WTP for the conservation of cultural landscapes is not merely a matter of economic rationality but also the outcome of an interplay between multiple psychological mechanisms, actual behavioural investments, and socio-demographic conditions. Within the Furusato Nozei framework, this process becomes particularly complex because contributors—often tourists or non-residents—balance altruistic motives with tangible incentives. Tourism decision-making is shaped by subjective cognition and emotional processing (Ajzen, 1991; Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Chi & Qu, 2008; Hosany & Gilbert, 2010; Oliver, 2014), moulded by immersive experiences and resource commitments at destinations (Arkes & Blumer, 1985; Kyle et al., 2004b; Lee, 2016; Ramkissoon et al., 2013), and constrained by socio-demographic factors (Carson et al., 2003; Snowball, 2008; Tuan & Navrud, 2007). To systematically uncover the mechanism through which tourists support cultural landscapes via Furusato Nozei, this study adopts an integrative framework comprising (1) psychological pathways, (2) behavioural investment, and (3) socio-demographic conditions.

2.1. Psychological Pathway

Tourists’ WTP often originates from motivations and is progressively transformed into cultural landscape conservation via Furusato Nozei, through destination image formation and satisfaction and loyalty (Prayag & Ryan, 2012; Yoon & Uysal, 2005).

Motivations influence destination choice by functioning as push factors (e.g., desire to escape, rest, seek novelty, health, or social interaction) or pull factors (e.g., heritage, cuisine, cultural resources, or natural attractions) (Kim & Lee, 2002). These motivations influence how tourists perceive destinations, which reflects tourists’ Cognitive Images (CI) (functional/tangible attributes, such as landscapes and cultural attractions, or psychological/abstract attributes, such as hospitality and atmosphere) and Affective Images (AI) (emotional responses evoked by the destination) (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Qu et al., 2011). Thus shaping the Satisfaction and loyalty (SI) and subsequent emotional attachment (da Costa Mendes et al., 2010).

Notably, recent studies highlight substantial conceptual and empirical overlap between ‘destination image’ and ‘satisfaction/loyalty’, as both reflect tourists’ global evaluations of destination attributes (Chen & Tsai, 2007; Prayag, 2009). Consequently, some researchers have advocated treating these constructs as comprehensive latent factors that capture tourists’ overall destination evaluation (Stylidis et al., 2017; Tasci & Gartner, 2007). Therefore, we adopted a comprehensive construct—Destination Evaluation—to avoid methodological redundancies. Destination Evaluation is a unified construct that integrates perceptual (image-related) and experiential (satisfaction- and loyalty-related) dimensions.

Hypothesis (H1).

Motivation positively affects destination evaluation.

Hypothesis (H2).

Destination evaluation positively affects WTP.

2.2. Behavioural Investment

Behavioural investment in tourism is defined as the continuous allocation of time, monetary resources, and cognitive engagement during conscious consumption and interaction with residents (Alrawadieh et al., 2019; Antón et al., 2017; Cevdet Altunel & Erkurt, 2015). Longer stays facilitate deeper exploration, whereas higher expenditures indicate greater engagement with local services and experiences. Drawing on sunk cost and investment–commitment theory (Arkes & Blumer, 1985; Rusbult, 1980), prior investment can foster continued commitment—but only when individuals perceive value congruence and fairness. In the context of Furusato Nozei, tourists’ engagement may either reinforce or weaken their willingness to contribute.

If contributions are framed primarily as transactional exchanges for return gifts or tax benefits, the crowding-out effect (Frey & Jegen, 2001) may lower sustained WTP. Interpersonal interaction exhibits similar ambivalence. Superficial or commercially mediated interactions often fail to generate authentic social bonds (MacCannell, 2004; Cohen, 1988), thereby limiting behavioural spillover into sustained prosocial or community-supportive contributions (Maki et al., 2019; Truelove et al., 2014).

Conversely, authentic, trust-based exchanges foster emotional reciprocity and moral obligation, strengthening place attachment and social identity (Kyle et al., 2004b; Ramkissoon et al., 2013), creating the social–psychological context for enduring support and higher willingness to pay (Jang & Feng, 2007), in the context of Furusato Nozei (López-Mosquera & Sánchez, 2012).

Hypothesis (H3).

Engagement (actual time and money already spent) affects WTP.

Hypothesis (H4).

Interacting with the locals affects WTP.

2.3. Socio-Demographic Conditions

Socio-demographic characteristics shape both the capacity and propensity of individuals to contribute to public goods, including heritage and landscape conservation. Income, age, gender, marital status, and residential location have long been recognised as important predictors of willingness to pay (WTP) in environmental and tourism valuation studies (Hanli et al., 2023; Jeon & Yang, 2021). Yet, their effects are context-dependent and may interact with institutional settings and incentive structures such as Furusato Nozei (Ramdas & Mohamed, 2014).

Classic environmental valuation and tourism economics studies highlight income as a key determinant of WTP (Onofrio et al., 2025). While higher-income individuals often exhibit greater WTP due to stronger financial ability and pro-social signalling motives (Hanemann, 1991; Hanli et al., 2023; Tuan & Navrud, 2007), this relationship is not necessarily linear, one research exploration completed, input provided, environmental protection provided, possible existential U-shape, inverted U-shape, negative or positive polarity (H. Zhao et al., 2023). Within the Furusato Nozei scheme, tax deductions may convert altruistic giving into optimisation behaviour, thus attenuating the expected positive income–WTP link. Younger donors tend to embrace digital platforms and novel participation formats (Onofrio et al., 2025), whereas older individuals prioritise stability and may view incentive-based schemes with scepticism (Kemperman et al., 2019). In a study of alternatives to single-use plastic food containers, age had a slightly negative effect on willingness to pay (S. Zhao et al., 2025). Gender differences reveal contrasting value orientations: women typically engage in emotionally driven, pro-social giving (Brown & Minty, 2008), while men are more responsive to instrumental or status-based incentives (Andreoni & Vesterlund, 2001). Gender may therefore moderate how contributors interpret the symbolic versus material aspects of Furusato Nozei. Marital status further shapes awareness and motivation; married donors may demonstrate stronger intergenerational concern, viewing heritage conservation as part of family and community continuity (Jeon & Yang, 2021). Residential proximity—either physical or symbolic—reflects the degree of place attachment. distant donors can develop “virtual proximity” through emotional narratives, showing that attachment can be socially constructed rather than purely geographic (Wei et al., 2021). Overall, demographic influences are neither uniform nor unidirectional; instead, they interact with psychological and behavioural pathways, amplifying or moderating their effects on WTP.

Hypothesis (H5a).

Age affects WTP.

Hypothesis (H5b).

Gender affects WTP.

Hypothesis (H5c).

Marriage situation affects WTP.

Hypothesis (H5d).

Household income affects WTP.

Hypothesis (H5e).

Address affects WTP.

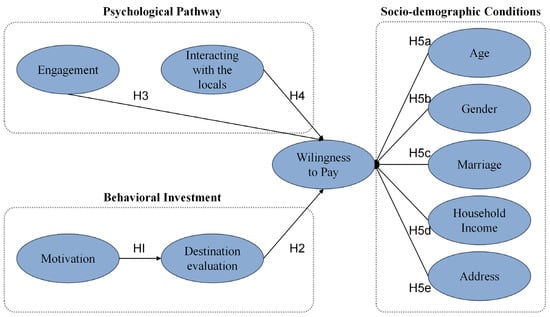

As shown in Figure 1, behavioural investment starts the chain: motivation improves destination evaluation (H1), and destination evaluation directly increases willingness to pay (H2). The psychological pathway adds parallel routes, where engagement and interaction with locals directly affect willingness to pay (H3–H4). Socio-demographic conditions (age, gender, marital status, income, address) directly affect willingness to pay (H5a–e), shaping individual capacity and propensity. We expect destination evaluation, engagement and interaction with locals to be the primary drivers, with socio-demographics explaining between-group differences.

Figure 1.

Research model and hypotheses.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

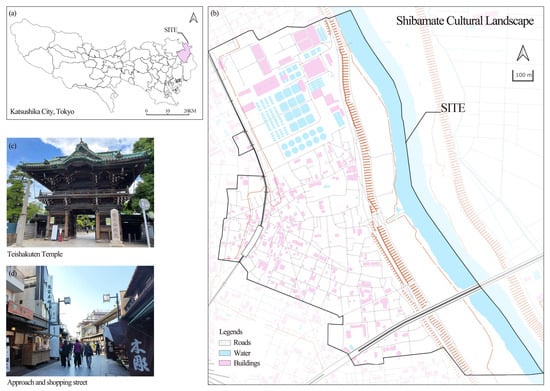

Shibamata (Figure 2), located in Katsushika Ward, Tokyo, is a historic district renowned for its traditional streets and the Shibamata Taishakuten Temple. The area integrates tangible elements, such as historic architecture and streetscapes, with intangible components, including local festivals, rituals, and community narratives, to form a distinctive cultural landscape. Shibamata was selected as the case study because it exemplifies how tourism, community participation, and heritage financing intersect within a metropolitan context. It also serves as one of the districts in Tokyo to receive targeted Furusato Nozei contributions. This combination of authenticity, visitor popularity, and institutional relevance makes Shibamata a representative model for exploring the mechanisms linking visitor behaviour, willingness to pay (WTP), and sustainable cultural landscape management.

Figure 2.

Location of Shibamata and study area. Created by the authors. (a) Boundary map of the Shibamata Cultural Landscape. The base map in (b) is sourced from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI) Vector Tiles (https://maps.gsi.go.jp/vector/, accessed on 10 July 2025) and processed by the authors with customized colors and linework. (c,d) Photographs taken by the authors in 2025.

3.2. Data Acquisition

A questionnaire survey targeting tourists who had visited Shibamata was conducted in February 2023, in collaboration with Freeasy Questionnaire Inc. (Osaka, Japan), a professional online survey company in Japan, with over 13 million registered part-time respondents (https://freeasy24.research-plus.net/, accessed on 10 August 2025). Although online panels may involve selection bias, the platform’s large and demographically balanced pool allows for stratified sampling to approximate Japan’s tourist population.

In the preliminary screening phase, 4000 randomly selected respondents were asked whether they had visited Shibamata in the past two years. Of these, 760 confirmed their visits. From this subset, 250 male and 250 female respondents were randomly selected for the survey. The final sample size of 500 meets the recommended 10:1 ratio of observations to model parameters for PLS-SEM, providing adequate statistical power and model stability (Hair, 2014).

The questionnaire comprised three sections. The first section collected socio-demographic information (Table 1). The second section measured the latent variables included in the proposed model (Table 2). The third section assessed WTP through Furusato Nozei, asking, ‘What is your opinion about utilising the Furusato Nozei system (hometown tax donation) for the conservation of Shibamata’s cultural landscape and regional development?’ Respondents were required to select one of four options: Not interested in Furusato Nozei; Interested but have not considered it; Already donated to other municipalities, but interested in donating to Shibamata; Intend to donate.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample data.

Table 2.

Items measured for potential variables of the hypothetical model.

Rather than measuring monetary WTP, this categorical design captures institutional willingness and behavioural intention, which are more appropriate for analysing Furusato Nozei participation where tax and return-gift mechanisms shape contribution behaviour. The participants were informed about the survey’s purpose and provided consent for utilising their responses. To address response bias and reliability, outliers and inconsistent responses were excluded prior to analysis. As a result, 500 valid responses were retained, yielding an effective response rate of 100% among eligible participants.

3.3. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarises the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. The sex ratio was balanced (50% male and 50% female). The largest age group was 31–50 years. More than half of the respondents were married (56%), and over 50% reported an annual household income below 7 million JPY. Additionally, 46.2% of respondents resided in Tokyo. These figures approximate the demographic structure of Japan’s domestic tourists, supporting the sample’s contextual representativeness.

3.4. Questionnaire Design

The second section measured latent variables, including motivation, destination image, satisfaction and loyalty, interaction with locals, and engagement. All constructs were assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). To ensure content validity and contextual relevance, two doctoral researchers in urban and landscape planning reviewed the questionnaire. A pilot test involving six previous visitors to Shibamata verified item clarity and response time; wording adjustments were made accordingly. The final measurement items and their corresponding references are listed in Table 2.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

This study employed partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) for empirical analysis. This method was chosen for three reasons: the study’s exploratory nature, focusing on prediction rather than strict model fit; the presence of non-normal data distribution in behavioural variables; and the model’s moderate sample size with multiple latent constructs, where PLS-SEM offers greater robustness than covariance-based SEM (Hair, 2014). Prior to model estimation, categorical socio-demographic variables were dummy-coded: female = 1, male = 0; married = 1, unmarried = 0; Tokyo = 0, other regions = 1. Annual household income (10,000 JPY) was treated as a continuous variable by assigning the midpoint of each income bracket (e.g., an income range of 100–200 was coded as 150).

4. Results

The results are presented in the following sections. First, the measurement model was assessed. Second, the model fit and explanatory power of the structural model were examined. Finally, the hypotheses were tested.

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model was evaluated in terms of indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2019). Table 3 reports the standardised factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent construct. All indicator loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, while α and CR values were greater than 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency reliability. All the AVE values were greater than 0.50, confirming convergent validity. Before testing the structural relationships, collinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF). As shown in Table 3, all the VIF values were well below the conservative threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2019)—multicollinearity was not a concern.

Table 3.

Construct validity and reliability.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). As reported in Table 4, the square root of the AVE for each construct was generally higher than its correlation with other constructs, indicating adequate discriminant validity. For HTMT, all values were below the conservative threshold of 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2014), supporting discriminant validity among the constructs. As all criteria were satisfied, and the excess was marginal, discriminant validity was considered acceptable for the purposes of this study.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT ratio.

4.2. Structural Model

To evaluate the structural model, this study followed the standard two-step PLS-SEM procedure (Hair et al., 2019), in which model fit was assessed based on multiple goodness-of-fit indices, including the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), discrepancy measures (d_ULS and d_G), and the normed fit index (NFI). The results indicate that the SRMR values were 0.050 for the saturated model and 0.060 for the estimated model, both below the recommended threshold of 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2014; Hu & Bentler, 1999), suggesting an acceptable model fit.

The discrepancy measures also provided further support. The d_ULS value was 0.806 for the saturated model and 1.188 for the estimated model, while the d_G values were 0.392 and 0.401, respectively. These results did not indicate problematic model misspecification.

Additionally, the NFI values (0.880 for the saturated model and 0.878 for the estimated model) approached the commonly recommended cutoff of 0.90, further suggesting an adequate model fit. Although NFI is less emphasised in PLS-SEM than in SRMR, its values provide additional evidence for global model adequacy (Hair et al., 2019). Considered together, these results demonstrate that the revised model exhibits an acceptable level of global fit, providing a reliable basis for subsequent structural model analyses.

4.3. Validation of Hypotheses

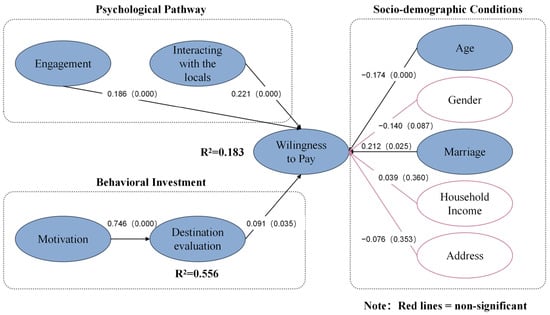

As shown in Figure 3 and Table 5, most of the hypotheses presented in Section 2 were statistically supported (p < 0.01). The structural model demonstrated satisfactory explanatory power, with the endogenous construct WTP accounting for 18.3% of the variance (R2 = 0.183), which is acceptable for behavioural and social science research (Si et al., 2022). Motivation significantly influenced destination evaluation (β = 0.746, p < 0.001), and destination evaluation exerted an effect on WTP (β = 0.091, p = 0.035). Similarly, engagement (β = 0.186, p < 0.001) and interaction with locals (β = 0.221, p < 0.001) significantly enhanced WTP. Among demographic factors, age was negatively associated with WTP (β = −0.174, p < 0.001), whereas marriage status showed a positive effect (β = 0.212, p < 0.05). Conversely, sex, household income, and address were not significant predictors of willingness to pay.

Figure 3.

Output of structural equation.

Table 5.

Hypotheses test results.

The mediation analysis revealed that destination evaluation played a significant mediating role in linking motivation to WTP (β = 0.068, p < 0.05). Specifically, motivation exerted an indirect influence on WTP through destination evaluation—tourists’ motivational factors shape their WTP primarily by enhancing their destination evaluation. As only one indirect pathway was identified, the total and specific indirect effects were identical (Table 6). These results underscore the central role of destination evaluation as a conduit through which motivational factors affect tourists’ payment intentions.

Table 6.

Total and specific indirect effects.

5. Discussion

5.1. Psychological, Behavioural, and Socio-Demographic Pathways to WTP

This study verified the core roles of psychological pathways, behavioural investment, and socio-demographic conditions in predicting tourists’ WTP. At the psychological level, motivation strongly enhanced destination evaluation, which in turn influenced WTP. This sequential relationship provides structured empirical evidence for tourism behaviour research (Chen & Phou, 2013; Crompton, 1979; Prayag et al., 2017; Yoon & Uysal, 2005). Even under fiscal instruments such as Furusato Nozei, tourists’ WTP reflects value judgements derived from cognitive–affective processing, aligning with destination image theory, which emphasises that cognitive and affective images jointly shape attitudes and behaviours (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Chi & Qu, 2008), rather than purely in tax efficiency.

Within the behavioural investment pathway, tourists who devoted more time, spending, and interpersonal engagement exhibited higher WTP. These findings are consistent with the sunk-cost effect (Arkes & Blumer, 1985) and place attachment research (Kyle et al., 2004a; Ramkissoon et al., 2013), but gain new relevance in the Furusato Nozei context. Here, prior engagement does not merely create a sunk cost—it fosters a sense of reciprocal participation. Interaction with residents strengthens the social significance of cultural landscapes and transforms tourists from ‘spectators’ into ‘co-creators’, making their payment behaviour more strongly rooted in emotional belonging and a sense of responsibility (Briedenhann & Wickens, 2004; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004; Ramkissoon et al., 2013).

Regarding socio-demographic conditions, the significant influence of marital status and age, and the non-significance of sex, income, and residential location, offer both theoretical and methodological insights. This finding contradicts numerous environmental economics studies, in which income is a primary predictor of WTP (Carson et al., 2003; Mitchell & Carson, 2013). We argue that this paradox stems from the institutional design of the Furusato Nozei system itself (Hasegawa, 2017; Rausch, 2019). The tax deduction mechanism effectively neutralises the income effect for many donors because contributions up to a certain limit have a near-zero marginal cost. This shifts the decision from ‘Can I afford this?’ to ‘Do I want to redirect my existing tax liability for this purpose and receive a gift?’. This institutional feature reshapes economic behaviour, making non-economic factors, such as emotional attachment and social roles, critically more important than pure financial capacity (Tax Policy Center, 2020). However, alternative explanations should be considered. Income was measured in broad self-reported categories, which may have constrained variability and masked subtle gradients among donors. Moreover, the surveyed population—tourists already capable of discretionary cultural spending—may be relatively homogeneous in financial terms, reducing observable income differences. Similarly, the absence of significant effects for gender and residential address may reflect measurement and sampling constraints rather than true null relationships. Gender differences in altruistic behaviour are well documented, but these effects can weaken when donation contexts combine emotional appeal with tangible returns. Likewise, residential location (Tokyo vs. other regions) may no longer be a decisive factor when online participation allows non-local donors to express “virtual proximity”. Married individuals with stronger family and social responsibilities may be more inclined to assume cultural protection responsibilities, whereas the mobility and short-term orientation of younger cohorts may weaken their willingness to make long-term contributions (Devaux et al., 2018).

Overall, these findings reveal that in Furusato Nozei, institutional incentives reconfigure traditional WTP determinants, shifting the explanatory focus from economic capability to emotional engagement and perceived social role.

5.2. Mechanism Operation and Policy Implications Under the Furusato Nozei System

The mediation analysis highlighted that motivation influenced WTP primarily through destination evaluation (β = 0.746 → β = 0.091)—policy interventions should strengthen the evaluative perception of destinations rather than relying solely on fiscal incentives. One actionable approach is to design altruistic framing campaigns (e.g., ‘Your donation restores one meter of a temple wall’), which directly connect motivational drivers with positive evaluations of the locality. Such message framing has been shown to enhance prosocial behaviours by appealing to moral satisfaction rather than material rewards (S. Li et al., 2022).

In terms of behavioural investment, tourist–resident interactions enhance WTP (β = 0.186 for engagement; β = 0.221 for interaction with locals) and foster long-term commitment to preservation activities—conservation extends beyond physical restoration to social reproduction and experiential participation (H. Li et al., 2023). These results suggest that participation-based mechanisms can operate as commitment devices that transform temporary experiences into long-term fiscal engagements. For example, Furusato Nozei projects allow donors to adopt a rice terrace, receive annual reports with photos, or participate in seasonal farming festivals. These measures allow tourists to form tangible, recurring bonds with the destination, effectively reducing the intention–behaviour gap and sustaining contributions over time.

Socio-demographic differences further indicate that a tailored policy design is necessary (Wu & Salleh, 2025). Married individuals—who showed higher WTP (β = 0.212, p < 0.05)—may respond to initiatives emphasising family responsibility and heritage transmission, whereas younger cohorts—whose WTP tends to be digitally mediated—may engage more through short-term or online programmes such as virtual heritage tours linked to micro-donations. This differentiation increases inclusivity and maximises policy efficiency by aligning motivational structures with destination evaluation pathways.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that Furusato Nozei can evolve from a transactional tax scheme into a participatory heritage-financing mechanism. By linking motivational framing, experiential participation, and demographic targeting to empirical determinants of WTP, policymakers can reinforce the financial and social sustainability of cultural landscapes through continuous, emotionally grounded public engagement.

5.3. International Comparisons and Broader Implications for Cultural Landscape Financing

Building on the empirical insights from Japan’s Furusato Nozei system, this section situates the system within a global context by comparing it to two other heritage funding mechanisms: the United Kingdom’s National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) and Korea’s Hometown Love Donation System (HLDS). The comparison (Table 7) highlights differences in funding sources, operational mechanisms, donor incentives, and governance and identifies the unique features of the Japanese system that may inform international practice.

Table 7.

Summary of key characteristics of the three systems.

While NLHF relies on lottery revenues channelled into centrally managed heritage grants, Furusato Nozei and HLDS operate as decentralised donation systems in which individuals can directly support municipalities of their choice. This decentralisation explains Japan’s distinctive behavioural outcomes: donor autonomy activates psychological ownership and local trust, making contributions feel personal rather than bureaucratic. In contrast, the UK’s centralised grant model sustains transparency and professional oversight but limits emotional engagement, since contributors cannot select specific destinations. Donor incentives also diverge; Furusato Nozei and HLDS combine tax deductions with tangible return gifts, embodying ‘impure altruism’ by aligning private benefits with public contributions. This alignment of self-interest and social contribution encourages repeated participation and helps narrow the intention–behaviour gap observed in many donation schemes. The NLHF, offering only indirect social rewards, relies more on collective identification than on individual reciprocity—effective for national cohesion but less potent for sustained, place-based giving. Governance further differentiates the systems. Local governments manage Furusato Nozei and HLDS under national regulation, ensuring accountability while preserving local autonomy, whereas NLHF follows a centralised governance model that prioritises strategic national planning but limits donor influence over project allocation. Beyond these institutional contrasts, cultural foundations also matter. Japan’s Furusato Nozei is embedded in the traditions of reciprocity and local–urban linkages, transforming tax contributions into acts of place attachment. The UK model reflects a welfare-state legacy in which heritage is framed as a collective national good rather than a local responsibility. Korea’s HLDS, introduced in 2023, mirrors the Japanese design but is closely tied to regional equity policies, highlighting the role of institutional borrowing and adaptation. These cultural commentaries have been condensed here to emphasise their analytical significance rather than descriptive detail.

Regarding transferability, several features of Furusato Nozei offer lessons for other contexts: Destination-based framing, which personalises donations and enhances emotional salience; Participatory donor programmes, which institutionalise continued engagement through communication and feedback loops. However, wholesale replication is unlikely to succeed without comparable administrative capacity and social trust; adaptation must respect each country’s fiscal system and civic culture.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study validates the effects of psychological factors, behavioural investment, and socio-demographic conditions on tourists’ WTP, several limitations should be acknowledged and addressed in future research. To enhance clarity, these limitations can be grouped into methodological, contextual, and theoretical categories.

In methodological aspects, a common issue in contingent valuation studies is hypothetical bias, where respondents may overstate their WTP because the scenario involves no real financial consequence (Hensher, 2010). Recent meta-analyses show that this bias can be reduced through improved survey designs, such as cheap-talk or consequentiality scripts (Champ et al., 2009; Penn & Hu, 2018). Therefore, our WTP estimates should be interpreted as a potential upper bound of actual WTP. This lack of real-world consequences may also contribute to our finding of the insignificance of income. Future studies should also incorporate additional factors, including institutional incentives, community engagement, and cultural education.

In contextual aspects, this study focuses on Japan’s Furusato Nozei system, a unique institutionalised framework embedded within Japan’s fiscal and cultural context. While this offers valuable insights into incentive-based heritage financing, the findings are context-specific and may not directly generalise to other national systems. Empirical evidence shows that inter-municipal competition for donations has intensified spending on return gifts and reduced fiscal efficiency (Fukasawa et al., 2020), while theoretical models suggest that weak regulatory constraints can distort local government behaviour and undermine equity (Makino & Ogawa, 2025). Future research could examine the applicability of such institutionalised WTP mechanisms under different fiscal policies, cultural contexts, and tourism management systems and investigate how varying institutional arrangements influence tourists’ behaviours.

In theoretical aspects, this study relies primarily on survey data to capture tourists’ psychological states and behavioural investments. Future research could incorporate actual behavioural data, longitudinal tracking, or experimental interventions to validate the dynamic relationship between WTP and concrete conservation actions. Integrating qualitative approaches—such as interviews with donors or participatory observation—could also illuminate how emotional, cultural, and moral factors mediate institutional participation.

6. Conclusions

This study examined tourists’ WTP for cultural landscape conservation in Shibamata, Tokyo, through Japan’s Furusato Nozei system. By integrating psychological pathways, behavioural investments, and socio-demographic conditions into a partial least squares structural equation modelling, we identified the mechanisms through which tourists’ motivations and experiences are transformed into fiscal support for heritage protection.

The results revealed three key findings. First, WTP in cultural landscapes is not solely an economic preference but a product of institutional design that aligns personal motivation with public value—demonstrating that well-calibrated incentives can transform altruism into sustainable heritage financing. Second, behavioural investments, especially interactions with residents, serve as a bridge between cognitive intention and financial commitment, reaffirming that conservation is both a fiscal and a socio-emotional process. Third, demographic factors such as marital status and age exert notable influences, whereas income does not, reflecting the unique institutional design of Furusato Nozei, which reduces the role of financial constraints.

Theoretically, this research contributes to the understanding of institutional mechanisms by demonstrating that fiscal mechanisms can reconfigure pro-social motivations into stable public goods provision. Empirically, this study provides quantitative evidence from tourists’ perspectives on how cultural landscapes can be sustained through innovative funding mechanisms. Practically, the findings provide guidance for local governments and tourism practitioners on fostering lasting regional support through meaningful visitor experiences and destination images, rather than material return gifts. Effective heritage financing depends on cultivating long-term relationships and trust between visitors and communities, highlighting the potential of institutional design to promote more relational and sustainable forms of cultural landscape governance.

Future research should extend this framework through experimental and longitudinal approaches that capture real behavioural outcomes, and through cross-cultural comparisons that test the adaptability of institutionalised WTP models in diverse governance and value systems. Such efforts would enhance our understanding of sustainable cultural landscape financing in an era of fiscal austerity. While the findings offer useful implications for heritage policy, they should be interpreted with caution. The results are context-specific and based on a single institutional setting; direct transfer of the Furusato Nozei model may entail fiscal or equity risks if governance and incentive structures differ.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and R.M.; methodology, Y.T. and R.M.; software, Y.T.; validation, R.M., S.L. and J.X.; formal analysis, Y.T.; investigation, R.M.; resources, Y.T.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and J.X.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, K.F.; project administration, K.F.; funding acquisition, K.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Grant Number 24K03144.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the Guidelines of the Human Research Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University. (https://www.chiba-u.ac.jp/general/JoureiV5HTMLContents/act/frame/frame110001606.htm, accessed on 24 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The questionnaire responses were collected anonymously and cannot be shared in raw form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WTP | Willingness to Pay |

| M | Motivation |

| CI | Cognitive Images |

| AI | Affective Images |

| SI | Satisfaction and loyalty |

| E | Engagement |

| IL | Interaction with Locals |

| DE | Destination Evaluation |

| SRMR | Standardised Root Mean Square Residual |

| NLHF | National Lottery Heritage Fund |

| HLDS | Hometown Love Donation System |

References

- Abuamoud, I. (2025). Assessing tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainable tourism in Petra, a contingent valuation study. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology, 24, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., Oom do Valle, P., & da Costa Mendes, J. (2013). The cognitive-affective-conative model of destination image: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(5), 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M., Errico, A., Santoro, A., Dani, A., & Preti, F. (2019). Terraced landscapes and hydrogeological risk. Effects of land abandonment in Cinque Terre (Italy) during severe rainfall events. Sustainability, 11(1), 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberini, A., & Longo, A. (2006). Combining the travel cost and contingent behavior methods to value cultural heritage sites: Evidence from Armenia. Journal of Cultural Economics, 30(4), 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z., Prayag, G., Alrawadieh, Z., & Alsalameen, M. (2019). Self-identification with a heritage tourism site, visitors’ engagement and destination loyalty: The mediating effects of overall satisfaction. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7–8), 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C., Camarero, C., & Laguna-García, M. (2017). Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseres, S. A., & Sira, R. K. (2020). Estimating visitors’ willingness to pay for a conservation fund: Sustainable financing approach in protected areas in Ethiopia. Heliyon, 6(8), e04500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. (n.d.). With Japan as inspiration, South Korea unveils donation system to rejuvenate local economies. Available online: https://www.asiapacific.ca/publication/japan-inspiration-south-korea-unveils-donation-system (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, N., Wani, M. D., Shah, S. A., & Dada, Z. A. (2025). Tourists’ attitude and willingness to pay on conservation efforts: Evidence from the west Himalayan eco-tourism sites. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(8), 18933–18951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedate, A. M., Herrero, L. C., & Sanz, J. A. (2009). Economic valuation of a contemporary art museum: Correction of hypothetical bias using a certainty question. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33(3), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedenhann, J., & Wickens, E. (2004). Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—Vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tourism Management, 25(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P. H., & Minty, J. H. (2008). Media coverage and charitable giving after the 2004 tsunami. Southern Economic Journal, 75(1), 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. T., Mitchell, R. C., Hanemann, M., Kopp, R. J., Presser, S., & Ruud, P. A. (2003). Contingent valuation and lost passive use: Damages from the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Environmental and Resource Economics, 25(3), 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevdet Altunel, M., & Erkurt, B. (2015). Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(4), 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, P. A., Moore, R., & Bishop, R. C. (2009). A comparison of approaches to mitigate hypothetical bias. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 38(2), 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., & Phou, S. (2013). A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tourism Management, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C. G.-Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L., Zhang, Y., Su, C.-H., Chen, M.-H., & Wang, J. (2019). Understanding tourists’ willingness-to-pay for rural landscape improvement and preference heterogeneity. Sustainability, 11(24), 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M., & Norman, P. (2022). Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 923464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Mendes, J., Oom do Valle, P., Guerreiro, M. M., & Silva, J. A. (2010). The tourist experience: Exploring the relationship between tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 58(2), 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Darlow, S., Essex, S., & Brayshay, M. (2012). Sustainable heritage management practices at visited heritage sites in Devon and Cornwall. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 7(3), 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, N., Berthold, E., & Dube, J. (2018). Economic impact of a heritage policy on residential property values in a historic district context: The case of the old city of Quebec. Review of Regional Studies, 48(3), 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donation to Municipality Produced by Furusato Choice. (n.d.). Donation to Japanese municipality produced by Furusato choice. Available online: https://www.furusato-tax.jp/donationtojapan/en (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(5), 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, E., Fukasawa, T., & Ogawa, H. (2020). Intergovernmental competition for donations: The case of the Furusato Nozei program in Japan. Journal of Asian Economics, 67, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, P. C., Roders, A. R. P., & Colenbrander, B. J. F. (2017). Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, W. M. (1991). Willingness to pay and willingness to accept: How much can they differ? The American Economic Review, 81(3), 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanli, S., Xin, Z., Chunhung, L., Jingbo, J., & Hayat, K. R. (2023). Tourists’ willingness to pay for the non-use values of ecotourism resources in a national forest park. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 14(2), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K. (2017). Japan’s “Furusato Nouzei”(hometown tax): Which areas get how much, and is it really working? [Bachelor’s thesis, Duke University]. Available online: https://sites.duke.edu/djepapers/files/2017/11/kayhasegawa-dje.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., & Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D. A. (2010). Hypothetical bias, choice experiments and willingness to pay. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 44(6), 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., & Gilbert, D. (2010). Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences toward hedonic holiday destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 49(4), 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. S., & Feng, R. (2007). Temporal destination revisit intention: The effects of novelty seeking and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 28(2), 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinčić, D. A., & Šveb, M. (2021). Financial sustainability of cultural heritage: A review of crowdfunding in Europe. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(3), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.-Y., & Yang, H.-W. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourists’ wtp: Using the contingent valuation method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemperman, A., van den Berg, P., Weijs-Perrée, M., & Uijtdewillegen, K. (2019). Loneliness of older adults: Social network and the living environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-S., & Lee, C.-K. (2002). Push and pull relationships. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G., Graefe, A., Manning, R., & Bacon, J. (2004a). Effect of activity involvement and place attachment on recreationists’ perceptions of setting density. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(2), 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G., Graefe, A., Manning, R., & Bacon, J. (2004b). Predictors of behavioral loyalty among hikers along the Appalachian Trail. Leisure Sciences, 26(1), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J. (2016). The relationships amongst emotional experience, cognition, and behavioural intention in battlefield tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, T. C. (2008). Richard H. Thaler, Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness: Yale university press, New Haven, CT, 2008, 293 pp, $26.00. The Social Science Journal, 45(4), 700–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Chen, J., Ikebe, K., & Kinoshita, T. (2023). Survey of residents of historic cities willingness to pay for a cultural heritage conservation project: The contribution of heritage awareness. Land, 12(11), 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Ikebe, K., Kinoshita, T., Chen, J., Su, D., & Xie, J. (2024). How heritage promotes social cohesion: An urban survey from Nara city, Japan. Cities, 149, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Saayman, A., Stienmetz, J., & Tussyadiah, I. (2022). Framing effects of messages and images on the willingness to pay for pro-poor tourism products. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1791–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N., & Sánchez, M. (2012). Theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm theory explaining willingness to pay for a suburban park. Journal of Environmental Management, 113, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, A., & Allegro, I. (2024). Circular financing mechanisms for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage. In Adaptive reuse of cultural heritage: Circular business, financial and governance models (pp. 523–544). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. (2004). Staged authenticity—Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Tourism: The Experience of Tourism, 2(3), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeer, G., Fawcett, G., & Killick, T. (2008). Values and benefits of heritage. A research review. Heritage Lottery Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, A., Carrico, A. R., Raimi, K. T., Truelove, H. B., Araujo, B., & Yeung, K. L. (2019). Meta-analysis of pro-environmental behaviour spillover. Nature Sustainability, 2(4), 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Makino, Y., & Ogawa, H. (2025). Ending the race for return gifts: Do gift caps in the Furusato Nozei program work? CIRJE, Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. (n.d.). Easy to understand! Hometown tax payment. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/jichi_zeisei/czaisei/czaisei_seido/furusato/about/index.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Mitchell, R. C., & Carson, R. T. (2013). Using surveys to value public goods: The contingent valuation method. RFF Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D. (2002). Guy Garrod and Ken Willis 1999, economic valuation of the environment: Methods and case studies. Environmental and Resource Economics, 21(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Lottery Heritage Fund. (2018, December 20). About. Available online: https://www.heritagefund.org.uk/about (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Nguyen Viet, B., Dang, H. P., & Nguyen, H. H. (2020). Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1796249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIRA. (n.d.). A new stage for the Furusato Nozei system/my vision/papers. Available online: https://english.nira.or.jp/my_vision/2018/01/a-new-stage-for-the-furusato-nozei-system.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Oliver, R. L. (2014). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Onofrio, F., Rodella, I., & Gilli, M. (2025). Navigating WTP disparities: A study of tourist and resident perspectives on coastal management. Frontiers in Environmental Economics, 4, 1497532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, J. M., & Hu, W. (2018). Understanding hypothetical bias: An enhanced meta-analysis. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(4), 1186–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. (2009). Tourists’ evaluations of destination image, satisfaction, and future behavioral intentions—The case of Mauritius. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 26(8), 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H., Kim, L. H., & Im, H. H. (2011). A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32(3), 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, E. (2025). Beyond fishing: The value of maritime cultural heritage in Germany. Marine Policy, 182, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdas, M., & Mohamed, B. (2014). Impacts of tourism on environmental attributes, environmental literacy and willingness to pay: A conceptual and theoretical review. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 144, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H., Weiler, B., & Smith, L. D. G. (2013). Place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour: A comparative assessment of multiple regression and structural equation modelling. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 5(3), 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, A. (2019). Japan’s furusato nozei tax program. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 19(3), 6. [Google Scholar]

- Rössler, M. (2006). World heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landscape Research, 31(4), 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Pulpón, Á. R., & Cañizares Ruiz, M. d. C. (2019). Potential of vineyard landscapes for sustainable tourism. Geosciences, 9(11), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C. E. (1980). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16(2), 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpina, D., Casartelli, V., Marengo, A., & Mysiak, J. (2025). Financing strategies for the resilience of cultural landscapes. Lessons learned from a systematic literature and practice review. Cities, 162, 105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimauchi, T., Nambo, H., & Kimura, H. (2019). Funding tourism promotion and disaster management through hometown tax donation program. Journal of Global Tourism Research, 4(1), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, W., Jiang, C., & Meng, L. (2022). The relationship between environmental awareness, habitat quality, and community residents’ pro-environmental behavior—Mediated effects model analysis based on social capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowball, J. D. (2008). Measuring the value of culture: Methods and examples in cultural economics. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D., Shani, A., & Belhassen, Y. (2017). Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tourism Management, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A. D., & Gartner, W. C. (2007). Destination image and its functional relationships. Journal of Travel Research, 45(4), 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax Policy Center. (2020). How did the TCJA affect incentives for charitable giving. Available online: https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-did-tcja-affect-incentives-charitable-giving (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Toyoshima, Y., Kawakami, M., & Shen, Z. (2024). The current factors impeding the preservation and utilization of historical buildings in Japan. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, 12(4), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H. B., Carrico, A. R., Weber, E. U., Raimi, K. T., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2014). Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Global Environmental Change, 29, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, T. H., & Navrud, S. (2007). Valuing cultural heritage in developing countries: Comparing and pooling contingent valuation and choice modelling estimates. Environmental and Resource Economics, 38(1), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., & Ya, J. (2023). Tourists’ willingness to pay conservation fees: The case of Hulunbuir Grassland, China. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 14(3), 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y., Liu, H., & Park, K.-S. (2021). Examining the structural relationships among heritage proximity, perceived impacts, attitude and residents’ support in intangible cultural heritage tourism. Sustainability, 13(15), 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, B. (2019). Tourists’ willingness to pay increased entrance fees at Mexican protected areas: A multi-site contingent valuation study. Sustainability, 11(11), 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2023, February 14). Challenges of Furusato Nozei, Japan’s hometown tax programme. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/02/japans-hometown-tax-programme-show-challenges-for-the-future-tax-system/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Wu, F., & Salleh, N. H. M. (2025). Residents’ willingness to pay for heritage conservation: Insight from a discrete choice experiment. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 13(4), 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Yang, Y., Chen, Y., Yu, H., Chen, Z., & Yang, Z. (2023). Driving factors and scale effects of residents’ willingness to pay for environmental protection under the impact of COVID-19. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 12(4), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Tan, Q., Li, Y., & Li, J. (2025). Revealing determinants shaping the sustainable consumption of single-use plastic food container substitutes. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 110, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).