Travel Behaviour and Tourists’ Motivations for Visiting Heritage Tourism Attractions in a Rural Municipality

Abstract

1. Introduction

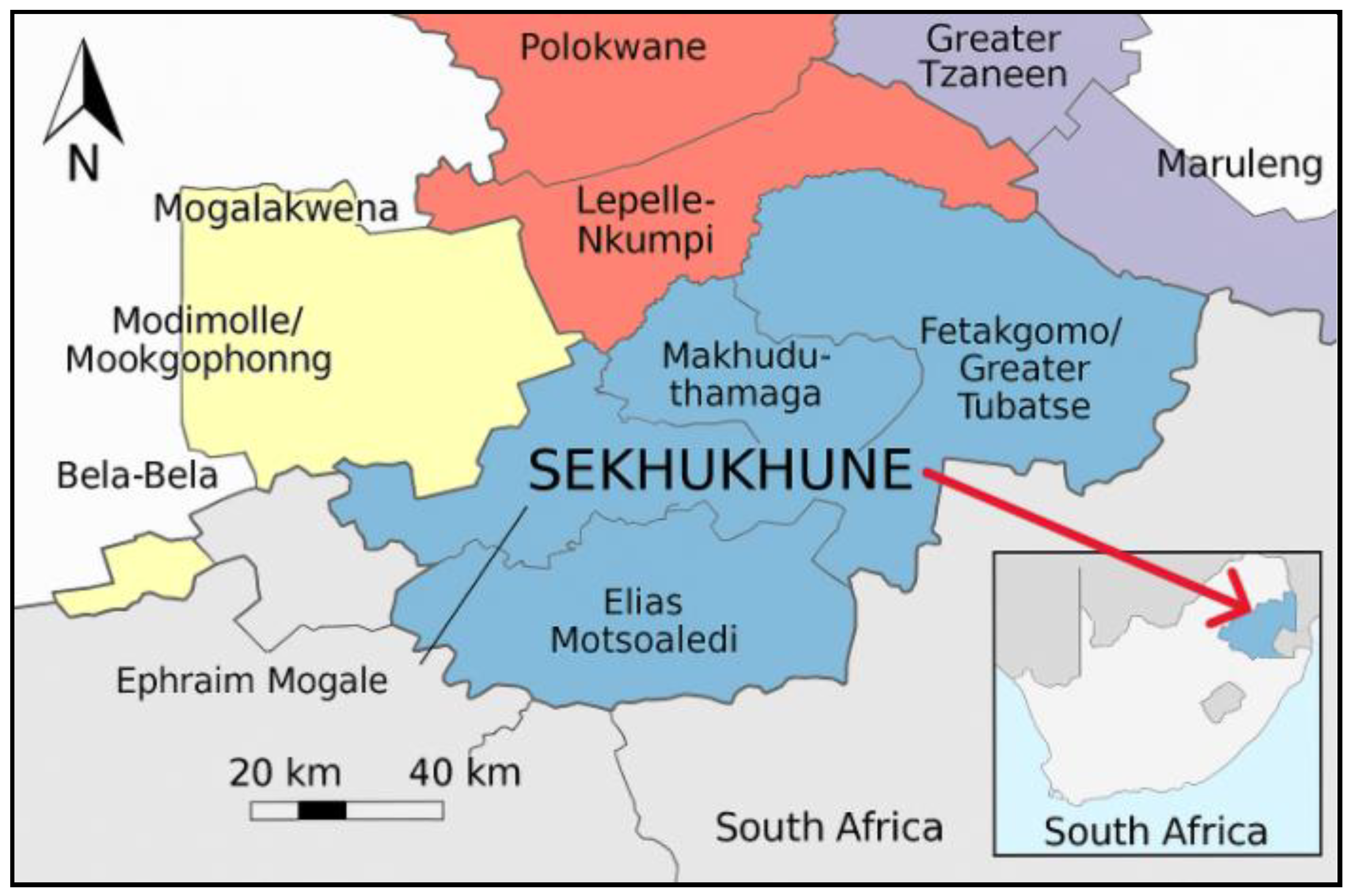

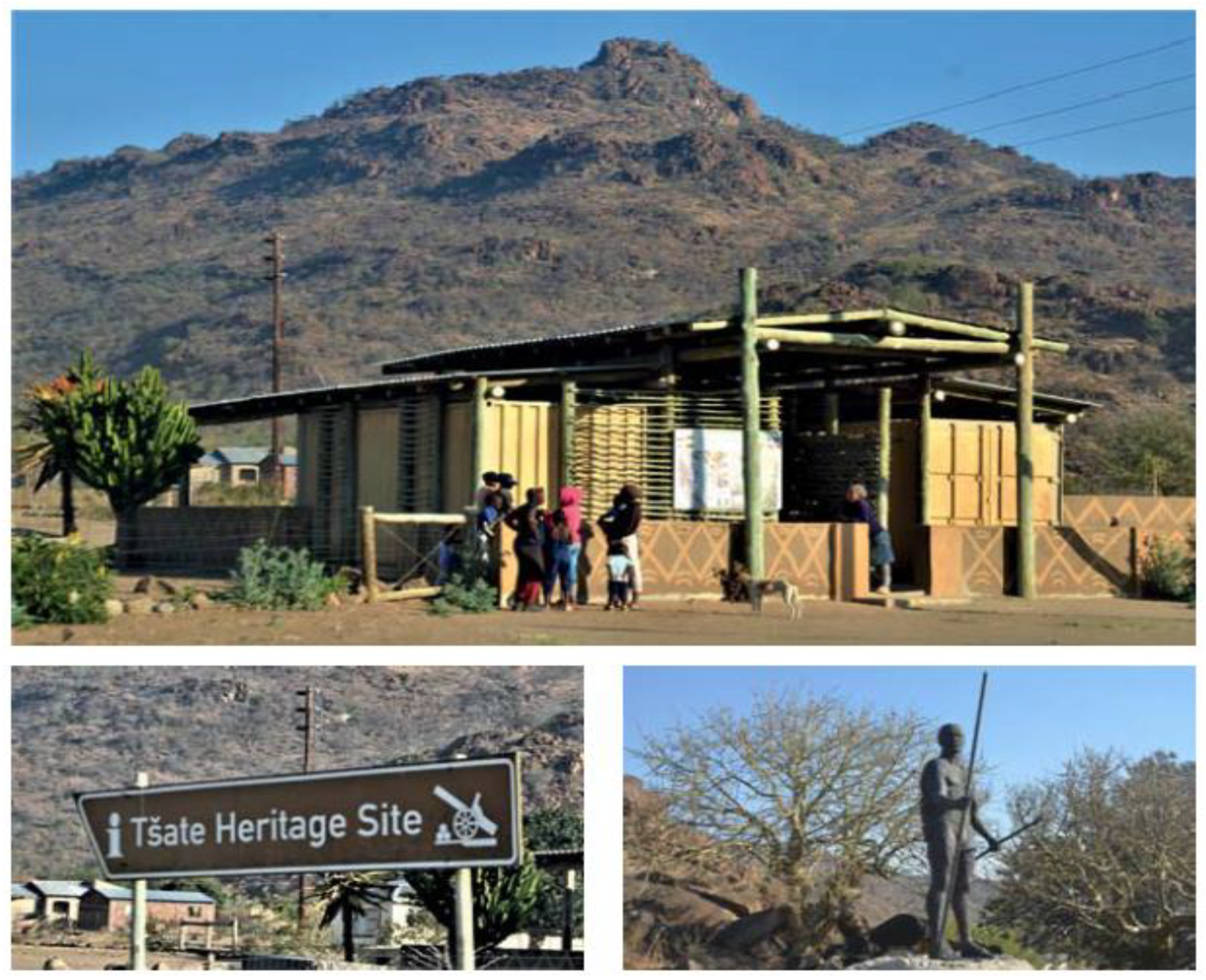

2. The Study Area

3. Literature Analysis

3.1. Characteristics of Heritage Tourism Products

3.2. Heritage Tourism: Tangible and Intangible

3.3. Tourist Motivations and the Theory of Planned Behaviour

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Profile of Visitors to the SDM

5.2. Frequency of Travelling for Heritage Tourism Purposes

5.3. Attractions/Activities, Enjoyment and Participation

5.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.5. Regression Coefficients Results

6. Implications of the Study

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2019). Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychology Review, 126, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Sousa, A. (2018). The problems of tourist sustainability in cultural cities: Socio-political perceptions and interests management. Sustainability, 10(2), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieux, J. (2022). Industrial heritage: A new cultural issue. In Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe. Available online: https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/arts-in-europe/monument/industrial-heritage-a-new-cultural-issue (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Angelidou, M., Karachaliou, E., Angelidou, T., & Stylianidis, E. (2017, August 28–September 1). Cultural heritage in smart city environments. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R., Hughes, K., Ding, P., & Liu, D. (2014). Chinese and international visitor perceptions of interpretation at Beijing built heritage sites. Journal for Sustainable Tourism, 22, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, N., & Kunwar, A. (2020). Tourist satisfaction: Relationship analysis among its antecedents and revisit intention. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 8(1), 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, L. (2013). Heritage tourism. In I. Rizzo, & A. Mignosa (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of cultural heritage (pp. 345–360). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Brand South Africa. (2025). Craft celebrated on heritage day. Available online: https://brandsouthafrica.com/91215/history-heritage/craft-celebrated-on-heritage-day/brandsouthafrica.com (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Briedenhann, J., & Wickens, E. (2020). Problems and prospects for heritage tourism in South Africa: Perspectives from marginalized communities. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(6), 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, C., Ilovan, O. R., Fekete, A., & David, L. (2023). Exploring relationships between heritage tourism and community development: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101073. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron, J. P. (2003). Tourism and sustainable development indicators: The gap between theoretical demands and practical achievements. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(1), 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Yang, Z., & Huang, X. (2023). How visitors perceive heritage value: A quantitative study. Sustainability, 15(7), 6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Wang, Y., Zou, M., & Li, J. (2022). Antecedents of rural tourism experience memory: Tourists’ perceptions of tourism supply and positive emotions. Behavioral Sciences, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council on Higher Education. (2020). Higher education qualifications sub-framework (HEQSF) of South Africa. CHE. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacations. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. (1977). Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2024). Greater Sekhukhune District Municipality profile. Available online: https://www.cogta.gov.za/ddm/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Take4_2020.06.25-SEKHUKHUNE-District-Profiles-Final-Version-.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Dias, Á., Viana, J., & Pereira, L. (2024). Barriers and policies affecting the implementation of sustainable tourism: The Portuguese experience. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoska, T., & Petrevska, B. (2012). Indicators for sustainable tourism development in Macedonia. In Proceedings of the first international conference on business, economics and finance: From liberalization to globalization—challenges in the changing world (pp. 389–400). Goce Delcev University, Faculty of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- European Space Agency. (2024). Sustainable tourism indicators. Available online: https://business.esa.int/projects/sustainable-tourism-indicators (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Fernández, G. A., Pérez-Gálvez, J. C., & López-Guzmán, T. (2016). Tourist motivations in a heritage destination in Spain. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 7(3), 226–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourist motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgeard, V. (2023, August 6). 15 Ways traveling abroad can transform your life. Brilliantio. Available online: https://brilliantio.com/how-traveling-abroad-changes-you (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Gebhard, K., Meyer, M., & Roth, S. (2007). Criteria for sustainable tourism for the three biosphere reserves Aggtelek, Babia Gora and Sumava. Ecological Tourism in Europe (ETE) & UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- George, R. (2013). Marketing tourism in South Africa (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giliberto, F., Nocifora, E., & Rinaldi, C. (2023). Re-imagining heritage tourism in post-COVID Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 15(4), 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps. (2024). Map of sekhukhune district municipality. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Sekhukhune+District+Municipality (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Griffin, K. (2011). The trials and tribulations of implementing indicator models for sustainable tourism management: Lessons from Ireland. In R. Phillips, & C. L. Bruni (Eds.), Quality-of-life community indicators for parks, recreation and tourism management (pp. 115–133). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Grobbelaar, L., Bouwer, S., & Hermann, U. P. (2019). An exploratory investigation of visitor motivations to the Barberton–Makhonjwa Geotrail, South Africa. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 25(2), 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, N., Taubman-Ben-Ari, O., & Ben-Artzi, E. (2020). The contribution of driving with friends to young drivers’ intention to take risks: An expansion of the theory of planned behavior. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 139, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D. R., & Dada, Z. A. (2014). Mutations and transformations: The contested discourses in contemporary cultural tourism. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, 7(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Habanabakize, T., & Dickason-Koekemoer, Z. (2021). The nexus between the tourism industry and country risk in South Africa. Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences, 58, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Drivers of customer decision to visit an environmentally responsible museum: Merging the theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(9), 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Lee, S., & Hwang, J. (2020). The impact of tourists’ environmental attitudes on pro-environmental behavior: The moderating role of social norms. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Henama, U. S. (2017). Tourism politics in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, U. P., & Bouwer, S. C. (2023). Motives to visit urban ecotourism sites: A study of a botanical garden in South Africa. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 14(2), 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, U. P., & Du Plessis, L. (2014). Travel motives of visitors to the national zoological gardens of South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 20(3), 1162–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, U. P., van der Merwe, P., Coetzee, W. J., & Saayman, M. (2016). A visitor motivational typology at Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage Site. Acta Commercii, 16(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A., Makridis, C., Baker, M., Medeiros, M., & Guo, Z. (2020). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 intervention policies on the hospitality labor market. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, S. M., Ismail, H. N., & Fuza, Z. I. M. (2020). Elderly and heritage tourism: A review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 447, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, G. (2001). Tourism research. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Khumalo, T., Sebatlelo, P., & Van Der Merwe, C. D. (2014). Who is a heritage tourist? A comparative study of constitution hill and the hector Pieterson memorial and museum, Johannesburg, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khunou, P. S. (2016). Development of a sustainable community-based tourism model: With special reference to Phokeng [Doctoral thesis, University of North West]. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. J., & Hwang, J. (2020). Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? Journal for Hospitality & Tourism Management, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, M., & Saayman, M. (2013). Assessing the viability of first-time and repeat visitors to an international jazz festival in South Africa. Event Management, 17(3), 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M., Saayman, M., & Hermann, U. P. (2014). First-time versus repeat visitors at the Kruger National Park. Acta Commercii, 14(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2021). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination using an extended theory of planned behavior model. Tourism Management, 37, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lebaka, M. E. K. (2020). The case of the Bapedi tribe in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, 46(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. H., & Jan, F. H. (2019). Ecotourism behavior of nature-based tourists: An integrated perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 58(7), 913–933. [Google Scholar]

- Limpopo Tourism. (2025). Pedi living culture tourism route. Available online: https://limpopotourism.penit.co.za/route/pedi-living-culture-tourism-route/limpopotourism.penit.co.za (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Lötter, M. J. (2016). A conceptual framework for segmenting niche tourism markets [Doctoral thesis, Tshwane University of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Magutshwa, L. (2020). Heritage tourism as a tool for regional economic development in South Africa: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 10(3), 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Manetsi, T. (2017). State-prioritised heritage: Governmentality, heritage management and the prioritisation of liberation heritage in post-colonial South Africa [Doctoral thesis, University of Cape Town]. [Google Scholar]

- Mangwane, J., Hermann, U. P., & Lenhard, A. I. (2019). Who visits the apartheid museum and why? An exploratory study of the motivations to visit a dark tourism site in South Africa. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(3), 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, S. (2019). Cultural heritage and tourism development in South Africa: Problems and prospects. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(5), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J. E., & Siphambe, G. (2023). Rural heritage and tourism in Africa. In C. Rogerson, & J. Saarinen (Eds.), Routledge handbook of tourism in Africa (pp. 211–225). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B., & du Cros, H. (2018). Cultural tourism: The partnership between tourism and cultural heritage management. The Haworth Hospitality Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mengich, O. (2013). Township tourism: Understanding tourist motivation [Ph.D. thesis, Gordon Institute of Business Science, University of Pretoria]. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, L. S., Grehl, M. M., Rutter, S. B., Mehta, M., & Westwater, M. L. (2022). On what motivates us: A detailed review of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. Psychological Medicine, 52(10), 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzeza, D., Hermann, U. P., & Khunou, P. S. (2018). An exploratory investigation towards a visitor motivational profile at a provincial nature reserve in Gauteng. South African Journal of Business Management, 49(1), 1–8. Available online: https://sajbm.org.za/index.php/sajbm/article/view/217 (accessed on 14 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, T. (2019). Digital heritage tourism: Innovations in museums. World Leisure Journal, 61(3), 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, T. (2022). The commercialization of heritage tourism in South Africa: Implications for authenticity and community participation. South African Journal of Cultural History, 14(2), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Negrușa, A., & Yolal, M. (2012). Cultural tourism motivation—The case of Romanian youths. Annals of Faculty of Economics, University of Oradea, 1(1), 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Ngondo, E., Hermann, U. P., & Venter, D. H. (2024). Push and pull factors affecting domestic tourism in the Erongo Region, Namibia. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 53(2), 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H. H., & Cheung, C. (2013). The classification of heritage tourists: A case of Hue City, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwanyana, N., & Ndlovu, Z. (2021). Craft markets and local artisans in heritage tourism: A case study of KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Phori, M. M. (2023). A sustainable heritage tourism development framework for the Sekhukhune District Municipality, Limpopo [Doctoral thesis, Tshwane University of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Phori, M. M., Hermann, U. P., & Grobbelaar, L. (2024). Residents’ perceptions of sustainable heritage tourism development in a rural municipality. Development Southern Africa, 41(3), 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (2018). Cultural Tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M. (2014). Reframing place-based economic development in South Africa: The example of local economic development. In C. M. Rogerson, & D. Szymańska (Eds.), Bulletin of geography. Socio-economic series No. 24 (pp. 203–218). Nicolaus Copernicus University. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Tourism and regional development: The case of South Africa’s distressed areas. Development Southern Africa, 32(3), 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M., & Nel, E. (2016). Planning for local economic development in spaces of despair: Key trends in South Africa’s distressed areas. Local Economy, 31, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2020). COVID-19 tourism impacts in South Africa: Government and industry responses. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 31(3), 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M., & Van Der Merwe, C. (2016). Heritage tourism in the global south: Development impacts of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, South Africa. Local Economy, 31(1–2), 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J., & Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Setting cultural tourism in Southern Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 24(3&4), 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Scoon, R. (2022). Geotraveller 50: Eastern limb of the bushveld igneous complex: Spectacular landforms, famous geosites and discovery of platinum. Technical Report. GeoBulletin. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhukhune District Municipality (SDM). (2025). Sekhukhune development agency annual report 2017/2018. Available online: https://www.sekhukhunedistrict.gov.za/sdm-admin/documents/SDA%20Annual%20report%202017%202018%20amended.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Shifflet, D. K., & Associates. (1999). Pennsylvania heritage tourism study. Available online: http://www.china-up.com:8080/memberbook/information/6/Pennsylvania%20Heritage%20TourismStudyfinalreport.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Sieras, S. G. (2024). Impact and identities as revealed in tourists’ perceptions of the linguistic landscape in tourist destinations. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 6(1), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Richards, G. (2013). Routledge handbook of cultural tourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- South African Tourism. (2025). The pedi living culture route, Limpopo. Available online: https://www.southafrica.net/gl/en/travel/article/the-pedi-living-culture-route-limpopo-explore-the-ways-of-the-pedi-people (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ștefan, S. C., Popa, S. C., & Albu, S. F. (2020). Implications of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory on healthcare employees’ performance. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 59, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M. M. (2021). The challenges of managing cultural heritage sites in China: A review. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 11(2), 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M. M., & Wall, G. (2019). Community participation in tourism at a world heritage site: Mutianyu Great Wall, Beijing, China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(2), 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subadra, I. N., Sutapa, I. K., Artana, I. W. A., Yuni, L. K. H. K., & Sudiarta, M. (2019). Investigating push and pull factors of tourists visiting Bali as a world tourism destination. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research, 8(7), 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- The Heritage Council. (2025). What is heritage tourism? Available online: https://www.heritagecouncil.ie/about/what-is-heritage (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Timothy, D. J. (2017). Cultural heritage and tourism: An introduction. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. J. (2022). Cultural heritage and tourism: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2015). Heritage tourism (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tlabela, K., & Munzhedzi, P. (2022). The development of heritage tourism infrastructure in rural South Africa: A Limpopo case study. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 20(4), 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation—UNESCO. (2020a). Intangible cultural heritage lists. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation—UNESCO. (2020b). World heritage and sustainable tourism programme. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation—UNESCO. (2023a). Cultural landscapes. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/#1 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation—UNESCO. (2023b). Tourism and culture synergies: Annual report. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380073 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation—UNESCO. (2024). What is meant by “cultural heritage”? Available online: https://en.unesco.org/frequently-asked-questions/definition-of-the-cultural-heritage (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation—UNWTO. (2004). Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations: A guidebook. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284407481 (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation—UNWTO. (2024). Measuring seasonality. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development/unwto-international-network-of-sustainable-tourism-observatories/tools-tourism-seasonality#:~:text=To%20measure%20the%20degree%20of,effort%20designed%20to%20reduce%20seasonality (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Van Der Merwe, C. D. (2016). Tourist guides’ perceptions of cultural heritage tourism in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 34, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, I. (2007). Imitating heritage tourism: A virtual tour in Sekhukhuneland, South Africa [Aegis-EU Working Paper]. Available online: https://www.aegis-eu.org/archive/ecas2007/papers/01-609-Kessel-Ineke-van_imitating-heritage-tourism.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Viljoen, J., & Henama, U. S. (2017). Growing heritage tourism and social cohesion in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Viviers, P., Botha, K., & Perl, C. (2013). Push and pull factors of three Afrikaans arts festivals in South Africa. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 35(2), 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J. D. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behaviour. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5, 100–121. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, L., He, B., Liu, L., Li, C., & Zhang, X. (2019). Sustainability assessment of cultural heritage tourism: Case study of Pingyao ancient city in China. Sustainability, 11(1392), 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. (2019, October). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its application for learners/students. Applied Teaching Seminar. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti, A., Putri, E. D. H., Indriyanti, I., Rahayu, E., & Asshofi, I. U. A. (2023). Community-based heritage tourism management model: Evidence from empirical validation. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 12(1), 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L., & Wall, G. (2020). Planning for heritage conservation and tourism: Stakeholders’ perspectives on the Great Wall of China. Tourism Management, 77, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & Li, Z. (2023, April 19–21). Geographically weighted Cronbach’s alpha. 31st Annual Geographical Information Science Research UK Conference (pp. 1–6), Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Characteristics | Category | Frequency (N) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 98 | 47% |

| Female | 110 | 53% | |

| Year of birth | 1960–1969 | 4 | 2% |

| 1970–1979 | 27 | 13% | |

| 1980–1989 | 83 | 40% | |

| 1990–1999 | 73 | 35% | |

| 2000 and after | 21 | 10% | |

| Highest level of Education | No formal education | 11 | 5% |

| Matric | 33 | 16% | |

| Higher Certificate | 32 | 16% | |

| Diploma | 68 | 33% | |

| Advanced Diploma | 42 | 20% | |

| Postgraduate Diploma | 14 | 7% | |

| Masters | 5 | 3% | |

| PhD/Doctorate | 2 | 1% | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 134 | 65% |

| Self-employed | 45 | 22% | |

| Student | 10 | 5% | |

| Unemployed | 16 | 8% | |

| Annual Income | <R25,000 | 24 | 12% |

| R25,001–75,000 | 2 | 1% | |

| R75,001–150,000 | 16 | 8% | |

| R150,001–250,000 | 54 | 27% | |

| R250,001–350,000 | 55 | 27% | |

| R350,001–500,000 | 44 | 21% | |

| >R50,000 | 11 | 5% | |

| Province of permanent residence | Gauteng | 132 | 64% |

| Mpumalanga | 25 | 12% | |

| North West | 20 | 10% | |

| Free State | 7 | 4% | |

| Northern Cape | 1 | 1% | |

| Limpopo | 21 | 10% |

| Frequency of Heritage Tourism Travel | Frequency (N) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Once a year | 64 | 31% |

| Twice a year | 123 | 59% |

| More than twice a year | 21 | 10% |

| TOTAL | 208 | 100% |

| Heritage Attractions/Activities | Frequency (N) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Historic sites (i.e., Tjate Heritage Site) | 14 | 7% |

| Cultural landscapes (i.e., Mohlake Royal Valley) | 12 | 6% |

| Ruins and archaeological sites (i.e., Ekholweni Heritage Site) | 60 | 29% |

| Sites associated with mining, industrial and agricultural heritage | 70 | 34% |

| Sites of important events and commemorations (i.e., Manone—Kgosi Mampuru II Annual Commemoration & Ekholweni Annual Heritage Festival) | 52 | 25% |

| Collections which collectively promote objects of heritage significance (i.e., museums, trails, tours and festivals) | 16 | 8% |

| Created landscapes (i.e., botanic and public gardens) | 6 | 3% |

| Built structures and surroundings | 9 | 4% |

| Cultural performances (i.e., Menyanya) | 103 | 50% |

| Cultural Languages | 16 | 8% |

| Rituals and beliefs (i.e., Go phasa badimo) | 37 | 18% |

| Social practices (i.e., Koma, lebollo) | 28 | 14% |

| Traditional dance, drama and music (i.e., Kiba, dinaka, dipepetlwane, diketo) | 68 | 33% |

| Human activities (traditional modes of transport, gardening, household chores) | 6 | 3% |

| Multi-cultural interactions | 20 | 10% |

| Stories and histories which shape the character and essence of the host community (i.e., the history of Bapedi) | 75 | 36% |

| Traditional cuisine/food (i.e., Malamogodu) | 28 | 14% |

| Motivator to Visit Heritage Attractions | Impact Loading | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Label | Relaxation and Novelty Motivators | Fun and Family Motivators | Educational Motivators | Heritage Appreciation Motivators | Socio-Cultural Motivators |

| Factor 1: Relaxation and novelty motivators | |||||

| To relax | 0.713 | ||||

| To get away from my daily routine | 0.845 | ||||

| To explore a new destination | 0.770 | ||||

| To meet people with similar interests | 0.671 | ||||

| To experience different lifestyles | 0.677 | ||||

| Factor 2: Fun and family motivators | |||||

| To have fun | 0.580 | ||||

| To get refreshed | 0.809 | ||||

| To spend time with family and friends | 0.831 | ||||

| Factor 3: Educational motivator | |||||

| To learn about history | 0.497 | ||||

| To learn about culture | 0.686 | ||||

| To learn new things | 0.665 | ||||

| To escape from a busy environment | 0.529 | ||||

| Factor 4: Heritage appreciation motivators | |||||

| To rest physically | 0.639 | ||||

| To do something out of the ordinary | 0.807 | ||||

| To visit museums and galleries | 0.814 | ||||

| To appreciate nature | 0.786 | ||||

| To appreciate architecture | 0.767 | ||||

| To visit historical places | 0.601 | ||||

| Factor 5: Socio-cultural motivators | |||||

| To visit cultural attractions | 0.508 | ||||

| To participate in entertainment | 0.622 | ||||

| To share a familiar or unfamiliar place with someone | 0.633 | ||||

| To participate in cultural performances | 0.541 | ||||

| To study, learn or research | 0.650 | ||||

| To participate in recreational activities | 0.799 | ||||

| To view and buy art and craft | 0.797 | ||||

| To experience traditional dance, drama and music | 0.819 | ||||

| To enjoy traditional cuisine and drink | 0.830 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy: 0.86 | |||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity: 4377.574 | |||||

| Significance: 0.00 | |||||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.863 | 0.852 | 0.835 | 0.908 | 0.907 |

| Eigenvalue | 1.822 | 1.221 | 1.172 | 11.579 | 3.127 |

| Dependent Variables | Predictors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel Motivators | Perceptions and Attitudes | R | R-Square | B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||

| Overall | Overall | 0.211a | 0.0446 | 0.2191 | 0.0706 | 0.2112 | 3.1014 | 0.0022 | 0.0798 | 0.3583 |

| To explore a new destination | Increased awareness and respect for local culture | 0.387a | 0.1499 | 0.2390 | 0.1044 | 0.3021 | 2.2898 | 0.0232 | 0.0330 | 0.4450 |

| To experience different lifestyles | Sexual promiscuity and prostitution | 0.358a | 0.1285 | 0.3041 | 0.0945 | 0.3517 | 3.2170 | 0.0015 | 0.1175 | 0.4906 |

| To learn about history | Increased incidents of crime | 0.356a | 0.1266 | −0.2170 | 0.0633 | −0.3700 | −3.4279 | 0.0008 | −0.3420 | −0.0921 |

| To escape from a busy environment | Increased incidents of crime | 0.356a | 0.1269 | −0.1404 | 0.0666 | −0.2274 | −2.1071 | 0.0365 | −0.2718 | −0.0089 |

| To do something out of the ordinary | Enhanced participation in cultural activities | 0.355a | 0.1261 | 0.2697 | 0.1239 | 0.2662 | 2.1760 | 0.0309 | 0.0251 | 0.5143 |

| An opportunity to learn about other cultures | −0.3126 | 0.1571 | −0.2636 | −1.9896 | 0.0482 | −0.6226 | −0.0026 | |||

| To visit museums and galleries | More income for community members | 0.412a | 0.1700 | −0.1577 | 0.0739 | −0.1892 | −2.1337 | 0.0342 | −0.3036 | −0.0119 |

| Increased incidents of crime | −0.1392 | 0.0680 | −0.2152 | −2.0456 | 0.0423 | −0.2734 | −0.0049 | |||

| Enhanced participation in cultural activities | 0.3100 | 0.1250 | 0.2957 | 2.4806 | 0.0140 | 0.0634 | 0.5566 | |||

| To appreciate nature | An increase in pollution in the community | 0.350a | 0.1225 | 0.1511 | 0.0763 | 0.2194 | 1.9790 | 0.0493 | 0.0004 | 0.3017 |

| More diseases in the community | 0.2988 | 0.1204 | 0.3013 | 2.4821 | 0.0140 | 0.0613 | 0.5364 | |||

| To appreciate architecture | Less poverty in the community | 0.384a | 0.1471 | 0.1643 | 0.0735 | 0.1850 | 2.2372 | 0.0265 | 0.0194 | 0.3093 |

| To visit cultural attractions | More income for community members | 0.393a | 0.1545 | −0.1986 | 0.0730 | −0.2435 | −2.7208 | 0.0072 | −0.3426 | −0.0546 |

| Enhanced participation in cultural activities | 0.4007 | 0.1234 | 0.3908 | 3.2479 | 0.0014 | 0.1572 | 0.6441 | |||

| To participate in entertainment | Enhanced participation in cultural activities | 0.370a | 0.1372 | 0.4333 | 0.1292 | 0.4075 | 3.3532 | 0.0010 | 0.1783 | 0.6882 |

| To share a familiar or unfamiliar place with someone | An increase in the value of land and property | 0.391a | 0.1529 | −0.1910 | 0.0780 | −0.2345 | −2.4485 | 0.0153 | −0.3449 | −0.0371 |

| An increase in littering | −0.2047 | 0.0955 | −0.2448 | −2.1437 | 0.0334 | −0.3930 | −0.0163 | |||

| To participate in recreational activities | Increased incidents of crime | 0.404a | 0.1630 | −0.1555 | 0.0668 | −0.2459 | −2.3277 | 0.0210 | −0.2873 | −0.0237 |

| More investment in the community | −0.2786 | 0.1405 | −0.2547 | −1.9828 | 0.0489 | −0.5558 | −0.0013 | |||

| An opportunity to learn about other cultures | 0.3978 | 0.1555 | 0.3316 | 2.5572 | 0.0114 | 0.0908 | 0.7047 | |||

| To view and buy art and craft | More diseases in the community | 0.434a | 0.1885 | 0.2921 | 0.1133 | 0.3010 | 2.5784 | 0.0107 | 0.0685 | 0.5156 |

| An opportunity to learn about other cultures | 0.4100 | 0.1543 | 0.3392 | 2.6563 | 0.0086 | 0.1054 | 0.7146 | |||

| To experience traditional dance, drama and music | An opportunity to learn about other cultures | 0.399a | 0.1591 | 0.4216 | 0.1602 | 0.3420 | 2.6311 | 0.0093 | 0.1054 | 0.7378 |

| To enjoy traditional cuisine and drink | An opportunity to learn about other cultures | 0.423a | 0.1791 | 0.4817 | 0.1536 | 0.4028 | 3.1366 | 0.0020 | 0.1787 | 0.7848 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phori, M.M.; Hermann, U.P.; Grobbelaar, L. Travel Behaviour and Tourists’ Motivations for Visiting Heritage Tourism Attractions in a Rural Municipality. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050260

Phori MM, Hermann UP, Grobbelaar L. Travel Behaviour and Tourists’ Motivations for Visiting Heritage Tourism Attractions in a Rural Municipality. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050260

Chicago/Turabian StylePhori, Madiseng M., Uwe P. Hermann, and Leane Grobbelaar. 2025. "Travel Behaviour and Tourists’ Motivations for Visiting Heritage Tourism Attractions in a Rural Municipality" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050260

APA StylePhori, M. M., Hermann, U. P., & Grobbelaar, L. (2025). Travel Behaviour and Tourists’ Motivations for Visiting Heritage Tourism Attractions in a Rural Municipality. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050260