1. Introduction

Food encounters are among the most memorable—and potentially challenging—elements of travel. Culinary culture shock (CCS) refers to the discomfort, surprise, or aversion travelers experience when confronting unfamiliar dishes, flavor profiles, or dining practices that diverge from their habitual diets(

Mkono, 2020). While CCS has been discussed in intercultural adaptation and gastronomy, much of the existing work implicitly assumes long-term adjustment processes. In contrast, most leisure trips are short and tightly scheduled; travelers must interpret, evaluate, and cope with culinary disconfirmation within days and often under social pressure from companions or guides (

Ellis et al., 2018). Although early work (e.g.,

Cohen & Avieli, 2004) acknowledged that unfamiliar or unpalatable foods can trigger anxiety and avoidance, research has only partially addressed the psychological and behavioural dimensions of such encounters, with limited process-oriented accounts of how they unfold during short-term trips. This short-horizon, trip-bounded nature of CCS raises distinct theoretical and practical questions that have received relatively limited attention compared with the extensive literature on the positive side of food experiences. Research in food tourism and consumer behavior often celebrates culinary encounters for enhancing destination image, cultural understanding, and memorable experiences (

Hjalager, 2004;

Björk & Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2016). Yet not all encounters are uniformly positive. Even within globally connected dining landscapes, individuals’ preferences are deeply shaped by cultural upbringing, habits, and sensory conditioning (

Rozin, 2006). When tourists meet markedly different cooking methods, ingredients, textures, or service etiquette, CCS may arise and spill over to the broader evaluation of the trip. Seminal work acknowledged that unfamiliar or unpalatable foods can generate anxiety and avoidance (e.g.,

Cohen & Avieli, 2004). Building on this foundation, the present study focuses specifically on how CCS unfolds during short-term travel and how it shapes destination evaluations.

From a theoretical perspective, long-term culture shock models emphasize gradual adaptation across months or years (

Oberg, 1960;

Ward et al., 2020). Such models illuminate background mechanisms but only partially capture the immediacy and recursiveness of CCS during short trips, where sensory reactions precede deliberation and where travelers may cycle rapidly between curiosity and discomfort within the same day. Expectancy–disconfirmation theory (EDT) offers a complementary lens: satisfaction is shaped by the match/mismatch between expectations and lived experience. In culinary settings, expectation disconfirmation is inherently embodied—aroma, taste, and texture elicit visceral responses that can amplify or attenuate subsequent cognitive appraisal. Integrating EDT with an embodied view of tasting allows CCS to be conceptualized as a process rather than a static state: disconfirmation triggers appraisal, emotion, and coping actions, which then reshape subsequent expectations as the trip progresses.

At the same time, not all travelers react similarly to CCS. Prior tourism and gastronomy studies show meaningful heterogeneity in motivations, prior exposure, and willingness to explore (

Björk & Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2016;

Yeung et al., 2022). Moreover, social influence—from peers, guides, service staff, and online sources—can shape the interpretation of the same culinary signal, nudging travelers toward avoidance, cautious sampling, or enthusiastic immersion. Rather than treating social influence as a separate “strategy,” we consider it a cross-cutting mechanism that conditions all coping responses by altering perceived norms, expectations, and perceived risk.

This article investigates CCS in Guangzhou, China, a major culinary destination where travelers frequently encounter flavor profiles (e.g., emphasis on freshness, textures, and light seasoning) that may differ from their habitual preferences. Our aim is not to study only culinary-motivated tourists; instead, we examine ordinary travelers whose primary motives (e.g., sightseeing, visiting friends, business, education) may or may not include food exploration. Situating culinary experiences within broader travel contexts clarifies that CCS can arise incidentally and vary across the same itinerary. Framing the setting in this way also distinguishes cross-regional (within-country) from cross-cultural (across countries) encounters, both of which can trigger CCS in different ways, and prevents over-generalizing from a single type of mobility.

Against this backdrop, we address three questions:

RQ1. How do travelers emotionally, cognitively, and behaviorally experience CCS during short-term trips?

RQ2. What coping trajectories—such as avoidance, gradual adaptation, and immersion—emerge, and how are they conditioned by social influence and situational affordances?

RQ3. How does CCS reshape travelers’ evaluations of the destination and their post-trip behavioral intentions?

Our study makes four contributions. First, it reframes CCS as a trip-bounded process, complementing long-term adaptation accounts by specifying the temporality and dynamics of culinary disconfirmation in mainstream tourism. Second, it integrates EDT with an embodied perspective to propose the Palate Adaptation Spiral Model (PASM)—a process model in which expectation disconfirmation initiates recursive cycles of appraisal, coping, and re-appraisal within the span of a trip. Third, it theorizes social influence as a cross-cutting mechanism that can either accelerate adaptation (e.g., guided tastings, peer encouragement) or entrench avoidance (e.g., vicarious negative experiences), thereby explaining why the same encounter yields divergent paths. Fourth, it translates these mechanisms into design levers for practitioners: pre-trip expectation alignment, transparent/pictorial menus that reduce uncertainty, and sequencing of tasting opportunities to scaffold adaptation.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews scholarship on culinary culture shock, expectancy–disconfirmation, and coping in tourism, and develops the PASM perspective that guides our analysis.

Section 3 details the empirical setting in Guangzhou and the qualitative design used to capture short-horizon processes.

Section 4 presents the findings, organized by coping trajectories and the role of social influence.

Section 5 discusses theoretical and managerial implications and notes limitations and future research directions.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative, multiple-source design to explore how travelers experience and cope with culinary culture shock (CCS) during short-term trips. A qualitative approach is appropriate for CCS research because the phenomenon involves subjective emotions, sensory perceptions, and meaning-making processes that are best captured in context rather than through standardized measurement instruments (

Creswell & Poth, 2016).

Data triangulation was used to enhance interpretive depth (

Flick, 2014). We combined (1) semi-structured interviews with travelers, (2) in situ ethnographic observations, (3) participant-generated food diaries, (4) short interviews with frontline service practitioners, and (5) document analysis (menus, visitor brochures, and online food guides). This multi-source strategy produced a rich dataset enabling us to understand CCS both as an individual experience and as a socially situated event.

Data were analyzed following reflexive thematic analysis (

Clarke & Braun, 2014), which treats researcher subjectivity as a resource and emphasizes iterative engagement with data. Analytic rigor was further enhanced through investigator triangulation and member-checking procedures, described in

Section 3.4.

3.2. Research Setting and Sampling

Fieldwork was conducted in Guangzhou, China, a major metropolitan hub known for its Cantonese cuisine and diverse food culture, making it an ideal setting to examine culinary culture shock (CCS) during short-term travel. Data collection took place between February and July 2024, covering both shoulder and peak travel seasons to capture variation in traveler motives and situational contexts.

- (1)

Sampling Strategy and Eligibility

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling to maximize variation in culinary experiences. Recruitment took place on-site at Shangxiajiu Pedestrian Street, Qingping Market, museum cafés, hotel lobbies, and Guangzhou South Railway Station, as well as through referrals from two local tour operators. Eligibility criteria required travelers to (a) spend at least two full days in Guangzhou, (b) have consumed at least one local meal, and (c) be willing to discuss their food experiences in depth.

- (2)

Sample Characteristics

The final sample comprised 30 primary participants: 16 domestic travelers from other provinces of China (cross-regional tourism) and 14 international travelers from Europe (UK, Germany, Finland, France), North America (US, Canada), Southeast Asia (Singapore, Malaysia), and South Africa.

Participants ranged in age from 19 to 62 years (M = 34.7), with gender evenly distributed (15 female, 15 male). Trip purposes included leisure (21 participants), business (6 participants), and education/exchange (3 participants).

- (3)

Supplementary Participants

To enrich contextual understanding, we conducted 11 short interviews with local stakeholders: 4 hotel concierges (average 12 min each), 3 chefs or restaurant managers (average 15 min each), 2 licensed tour guides, and 2 culinary instructors from Guangzhou cooking schools.

These interviews were used solely to contextualize service scripts, menu design, and culinary norms and were not coded as part of the primary tourist dataset.

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

- (1)

Semi-Structured Interviews

Thirty in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face in Mandarin, Cantonese, or English (based on participant preference) during the stay or within one week post-trip. Interviews lasted 35–75 min (M ≈ 52). The interview guide was researcher-developed based on previous CCS and food tourism literature (

Chang et al., 2011;

Mak et al., 2017) and piloted with three travelers. Core topics included expectations, memorable encounters, emotional/behavioral reactions, coping strategies, and post-trip reflections. Interviews were audio-recorded with consent, transcribed verbatim, and member-checked by participants.

- (2)

Ethnographic Observation

Ethnographic observations were conducted during food tours, market visits, and restaurant meals. Where consent was given, we shadowed participants from the interview sample to observe nonverbal reactions, hesitation, peer influence, and situational triggers of CCS. Additional opportunistic observations of other tourist groups in public dining spaces were recorded for contextual richness.

- (3)

Food Diaries

Ten participants kept daily food diaries, logging dishes consumed, emotional responses, and reflections on adaptation strategies. These diaries captured within-trip temporal dynamics (e.g., progression from avoidance to experimentation).

- (4)

Social Media Review

To triangulate international travelers’ representations of Guangzhou food, we systematically reviewed public Instagram posts tagged with #GuangzhouFood, #CantoneseCuisine, and similar hashtags using a VPN outside mainland China. Only publicly available posts were included, and usernames were anonymized. Posts were used descriptively to complement interview data and were not treated as a separate primary dataset.

- (5)

Airport Observation

To explore end-of-trip purchasing behavior, we conducted short intercept interviews with five travelers at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport (average 4 min each) and recorded fieldnotes on duty-free food purchase patterns (with participant consent).

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) as outlined by

Clarke & Braun (

2014), which conceptualizes analysis as an active and iterative process of meaning-making rather than a mechanical procedure. RTA treats researcher subjectivity as an analytical asset, emphasizing reflexivity and theoretical sensitivity.

- (1)

Analytic Process

Familiarization: The research team engaged in repeated reading of interview transcripts, food diaries, and fieldnotes, supplemented by listening to audio recordings to capture tone and nuance. Memos were written during this stage to document early impressions and potential sensitizing concepts.

Generating Codes: Initial codes were developed inductively within NVivo 14, allowing patterns to emerge from the data without applying a pre-existing codebook. Codes captured emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions of CCS.

Searching for Themes: Codes were iteratively clustered into candidate themes (e.g., avoidance, gradual adaptation, immersion) based on semantic and latent meaning connections. The food diary entries and ethnographic observations were cross-compared to test the robustness of themes.

Reviewing Themes: Candidate themes were reviewed for internal coherence and external distinctiveness. Disconfirming cases (e.g., travelers who bypassed adaptation entirely) were actively sought to ensure thematic boundaries were well-defined.

Defining and Naming Themes: Each final theme was clearly named and supported with data extracts, illustrating its conceptual essence. Thematic maps were developed to visualize relationships among themes and subthemes.

Producing the Report: The final narrative integrates participant quotes, diary excerpts, and observation notes with theoretical interpretation, linking coping trajectories to expectancy–disconfirmation theory.

- (2)

Collaborative Reflexivity

In keeping with RTA’s epistemological stance, intercoder reliability was not calculated. Instead, two researchers independently coded a subset of five transcripts and compared interpretations in peer debriefing sessions. Rather than “resolving discrepancies” in a positivist sense, the purpose was to deepen interpretive insight, challenge assumptions, and refine the coding frame. Divergent readings were treated as opportunities for theoretical elaboration.

- (3)

Triangulation

We employed data triangulation (interviews, diaries, observations, practitioner interviews) to capture multiple perspectives on CCS and enrich thematic development. Investigator triangulation was used by involving two analysts in code development and theme refinement, enhancing analytic depth.

- (4)

Member Checking and Audit Trail

To strengthen credibility, preliminary themes were shared with six participants in their preferred language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or English). Participants’ feedback (e.g., confirming that “gradual adaptation” accurately captured their process) was incorporated into theme definitions. An audit trail was maintained through analytic memos, reflexive journals, and version-controlled NVivo project files, allowing transparency in coding decisions and theme evolution.

- (5)

Ensuring Rigor

Our approach prioritizes theoretical resonance, transparency, and depth over numeric consensus, aligning with

Clarke & Braun (

2014)’s view that trustworthiness in RTA is achieved through reflexivity, rich description, and coherence between data and interpretation.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the ethical principles of the [University Name] Research Ethics Committee and was approved under protocol number 2024-TRV-013 prior to data collection.

- (1)

Informed Consent and Voluntary Participation

All participants received a plain-language information sheet describing the study aims, procedures, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Consent was obtained either in writing or verbally (recorded) before participation. For participants recruited in public spaces, consent was reconfirmed prior to audio recording or observational shadowing.

- (2)

Confidentiality and Anonymity

Participants were assured that their identities would remain confidential. Pseudonyms are used throughout the manuscript, and any potentially identifying details (e.g., workplace names, exact travel dates) were either generalized or removed during transcription.

- (3)

Data Security and Access

Audio recordings, transcripts, food diaries, and observation notes were stored on encrypted drives accessible only to the core research team. Data files were version-controlled, and backup copies were kept on secure institutional servers.

- (4)

Language and Translation Procedures

Interviews were conducted in Mandarin, Cantonese, or English depending on participant preference. For non-English interviews, professional transcription was followed by translation into English by bilingual members of the research team. A subset of transcripts underwent back-translation to verify meaning equivalence, minimizing translation bias.

- (5)

Member Checking

To enhance credibility and ensure respectful representation of participants’ voices, summary transcripts or thematic synopses were shared with six participants for member checking. Minor clarifications suggested by participants (e.g., about restaurant context, dish names) were incorporated into the dataset.

- (6)

Ethical Handling of Supplementary Data

Food diary entries and practitioner interview transcripts were anonymized before analysis. For social media data referenced in Findings (e.g., Instagram, Xiaohongshu posts), we used only publicly available content, removed usernames, and paraphrased quotes where necessary to prevent traceability.

By implementing these procedures, we ensured that the study complied with international ethical standards and that participant dignity, privacy, and data security were safeguarded throughout the research process.

4. Findings

4.1. Emotional and Psychological Responses to Culinary Culture Shock

Tourists in Guangzhou display a spectrum of affective and cognitive reactions when encounters with unfamiliar dishes disconfirm prior expectations built through home cuisines, travel media, and word of mouth. Our ethnographic notes from night markets and traditional tea houses repeatedly record an approach–withdrawal pattern at the first encounter with fermented or texturally complex items. One first-time French visitor described stinky tofu as “rotten, pungent, almost metallic… I instinctively backed away”, adding that he needed several visits and watching locals enjoy it before taking a small bite; even then, “the fermented tang lingered unpleasantly.” (Interview) The same expectation–disconfirmation arc emerged among domestic travelers from Northern China who anticipated primarily savoury profiles: “I ordered char siu expecting smoky richness, but the sweetness overwhelmed me… like dessert for dinner—something I had to mentally recalibrate.” (Interview)

Document analysis of English-language travel forums and guidebook chapters on Cantonese food consistently highlighted “original flavours” and subtle seasoning as points of friction for visitors accustomed to heavier spices or sauces. Rather than counting forum percentages, we treat these as recurrent themes that triangulate with interviews and observation. In high-end restaurants, our field notes repeatedly recorded requests for additional condiments from tourists with spice-forward taste habits, while others explicitly asked staff “how locals balance sweetness.”

Frontline staff narratives corroborate the emotional intensity of early encounters. A concierge at an international hotel recalled an executive who returned from a lunch featuring chicken feet and switched to room service: “He said it wasn’t only eating the feet—it was watching the enthusiasm of others at the table.” (Staff interview) In a dim sum workshop, tactile contact produced a distinct threshold: “Holding the actual feet—feeling skin and tiny bones—made me physically uncomfortable. It was a psychological barrier I hadn’t expected.” (Workshop participant)

Taken together, these traces illustrate how expectancy–disconfirmation triggers heightened arousal, protective withdrawal, or curiosity-driven sampling, setting the stage for the coping patterns that follow.

4.2. Coping Trajectories How Tourists Navigate Culinary Culture Shock

Three distinct coping trajectories emerged from the thematic analysis: Avoidance, Gradual Adaptation, and Full Immersion. These trajectories represent how travelers regulate their emotional and sensory responses to culinary culture shock over the course of a short trip. Avoidance involves rejecting or minimizing exposure to local cuisine; gradual adaptation reflects cautious experimentation and stepwise engagement; and full immersion represents active pursuit of local flavors as a source of pleasure and novelty. The following sections elaborate each trajectory in detail, illustrating them with verbatim participant quotations, diary excerpts, and ethnographic observations.

A summary of themes and subthemes, with representative interview/diary excerpts and observation notes, is provided in

Table 1.

4.2.1. Avoidance

A subset of travelers stabilize the situation by reverting to familiar fare or environments (international cafés, hotel restaurants) when uncertainty or aversion is high. Our breakfast observations at three international hotels repeatedly documented Western guests bypassing local congee and rice-roll stations in favor of scrambled eggs, toast, and pastries; field notes capture this as a persistent pattern, not a statistically sampled proportion. One British tourist explained: “By day three, the constant ‘adventure’ exhausted me… an expat café grounded me.” (Interview) For some, avoidance reflects risk management. A Korean traveler with coeliac disease described repeated miscommunication about gluten and “giving up and eating only at the hotel… I knew I was missing ‘real Cantonese,’ but the risks felt too great.” (Interview)

Observation notes and dining diaries indicate that prolonged avoidance often narrows itineraries: travelers allocate less time to food-centric places (markets, traditional tea houses) and more to malls or chains. Importantly, avoidance is rarely final; it frequently coexists with controlled experiments at other meals.

4.2.2. Gradual Adaptation

The most common movement we observed was toward small, reversible trials supported by gateway dishes, menu clarity, and peer modeling. Food tours and hotel concierges routinely sequence tastings from milder items (e.g., har gow) to bolder textures (e.g., chicken feet), building early successes before harder tests. Many independent travelers adopted parallel rules such as “one new dish per meal.” A Malaysian visitor’s diary captured a five-day climb: “Day 1: steamed shrimp dumplings—familiar. Day 3: roast goose—richer but approachable. Day 5: snake soup—herbal, not my favorite, but I felt proud to try it.” (Interview/diary)

Peer observation reduced perceived downside: “I’d point to what others were eating; if they smiled, I ordered the same.” (Interview) Guidebooks also provided scripts for progression (e.g., introductory sections on ‘Cantonese for beginners’ leading to ‘advanced’ items), which respondents cited when explaining why certain menus felt safe to try first.

4.2.3. Full Immersion

A smaller cohort reframed difference as distinction and sought deep engagement through classes, markets, and unmodified recipes. In a cooking workshop, a participant reported that making lo mai gai “changed my perspective—from ‘mushy’ to a symphony of textures.” (Workshop interview) Staff noted that immersion-oriented guests explicitly asked for “as locals eat it” preparations and soon recommended specific vendors to others. We interpret immersion not as a fixed trait (e.g., “neophilia”) but as a late-stage stance that becomes more likely after several scaffolded wins.

4.3. Role of Social Influences and Peer Recommendations

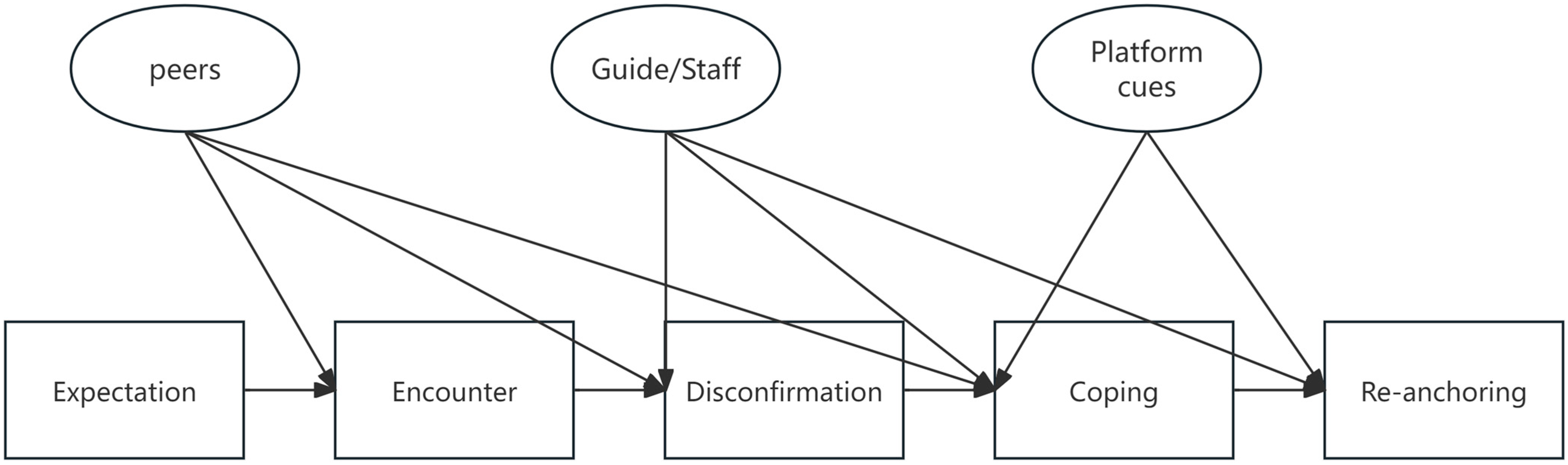

This study finds that social influence is not a stand-alone “strategy” but a transversal scaffold that attaches to multiple phases of the PASM loop—Expectation setting, Encounter, Disconfirmation, Coping, and Re-anchoring—altering the probability that a hesitant diner moves from avoidance to micro-experiments and, eventually, to immersion (see

Figure 1 for attachment points). Three channels recur across our materials: peers at the table, frontline staff and guides, and pre-encounter descriptors in English-language forums and guidebooks. Each channel works through three mechanisms: framing unfamiliar cues in meaningful language, sequencing experiences from mild to bold, and vicarious sampling that partitions risk.

Peers: scripts that shrink perceived downside. Group dining generated immediate, low-cost scripts: splitting one portion of a feared item, letting the most cautious person take the first nibble from a “safe side” of a plate, pairing a novel texture with a familiar staple, or adopting the shared rule of “one new dish per meal.” In our field notes from Shamian Island and the old-town teahouses, we repeatedly observed that a single, visibly positive first-bite reaction—often accompanied by laughter or surprise—was enough to convert an onlooker from categorical refusal to a micro-trial. One participant put it simply: “I’d point to what others were eating—if they smiled while chewing, I ordered the same.” Conversely, a single horror anecdote (“I got sick that time”) inflated perceived variance for an entire category and stalled trials for the rest of the meal. These peer cascades explain why the same tourist oscillated across meals: who sits next to whom, and who bites first, changed the decision context.

Frontline staff and guides: translation, sequencing, and visible care. Staff who used non-technical framings were consistently effective at reframing aversive signals as craft: “that silky mouthfeel signals freshness,” “a touch of sweetness balances roast aroma,” or “bone-in keeps moisture; chew is tender rather than rubbery.” Such framings lifted a dish out of a “risk” frame into a “style” frame. Guides and concierges also practiced sequencing: mild dim sum first, recognisable roasts second, then texture-forward items like chicken feet or duck tongue—“wins” were deliberately placed early so diners built trust before the hard test. A guide explained the choreography during one observed tour: “I serve the most cautious diner last for the challenging item and seat them next to the most enthusiastic taster—contagion does the rest.” Where kitchens briefly showed the mise-en-place or plated a half-portion to reduce commitment, hesitant diners shifted to conditional trials (“I’ll try two bites if we can also order congee”).

Forums and guidebooks: expectation calibration before the first bite. Our document analysis showed that neutral, plain-language descriptors—“crispy exterior,” “lightly sweet glaze,” “silky tofu”—and clear photos functioned as pre-encounter scripts. Several interviewees traced their first successful local order to a dish they had seen described in a guidebook paragraph that avoided hyperbole but specified texture and seasoning. By contrast, generic superlatives (“must-try,” “best ever”) produced little actionable guidance and rarely featured in participants’ decision stories. This calibration at the Expectation node reduced the shock at Encounter and softened negative disconfirmation.

How scaffolds fail. Over-selling—“you’ll love it!”—inflated expectations and sharpened disappointment at the first bite; normative frames—“this is for real locals”—silenced questions about portioning or preparation and pushed cautious diners back to the safe menu. We documented group conservatism in time-tight meals: once one person declared a category off-limits (“no offal today”), companions deferred to harmony. These failures matter because they explain backward steps in the spiral after apparent breakthroughs: the context, not the character, changed.

Mini-cases that show the mechanisms working together.

Clay-pot pivot: A Singaporean traveler wandered into a small shop, froze at the menu, and was rescued by the owner who brought a bao zai fan and narrated the crispy rice crust. “Without her, I would have ordered fried rice and missed this.” The staff framing gave a reason to try; the portioning kept the risk bounded; the crunch delivered a sensory win that re-anchored future expectations.

Hotpot dares: A Spanish group turned a feared experience into a game—“We dared each other through the broths. Laughing made it bearable.” Peer vicarious sampling and shared risk converted aversion into a story of competence.

Breakfast ladder: Multiple concierges described guests who began with “something local but not too strange” and, after two mornings of small wins, returned asking where locals eat without modifications. The ladder was: congee + youtiao → har gow → roast meats → texture-forward items.

Why make social influence transversal. Treating social influence as a cross-cutting scaffold rather than a discrete strategy: peers, staff, and pre-encounter texts attach to different nodes (

Figure 1), shrinking uncertainty at Expectation/Encounter, increasing the feasibility of Coping, and naming wins at Re-anchoring (“now that you liked X, the natural next step is Y”).

4.4. Impact of Culinary Culture Shock on Destination Perception and Future Travel Intentions (Expanded, Methods-Consistent)

Food encounters proved to be narrative pivots in how visitors later described Guangzhou. Interviews and diaries repeatedly show that once early disconfirmation is reframed—via a small success, a lucid explanation, or a peer-shared joke—tourists re-narrate the city from “risky and opaque” to “subtle and crafted.” Conversely, when avoidance dominated the short stay, food remained a background worry that muted enthusiasm for non-food attractions.

From friction to finesse: positive re-narrations. A Japanese visitor who began with skepticism about sweetness reported that wonton noodles—“balanced, savoury, with springy textures”—“changed my mind. I’m planning to come back for the winter-melon soup I missed.” Several participants described signature dishes that became anchors for future trips: double-skinned milk after a blind-tasting class (“silkiness I would never have noticed”), lo mai gai after a cooking workshop (“from ‘mushy’ to a symphony once I made it myself”). These small wins carried symbolic freight: they stood for a broader capacity to navigate difference, and respondents linked them to non-food bravery (trying a neighborhood market, riding a bus, entering a locals-only tea house).

Stalled spirals and ambivalent re-narrations. Travelers whose encounters remained dominated by texture shock narrated mixed feelings about revisiting. One interviewee summarized: “Guangzhou’s sights were stunning, but I would hesitate to return unless I can better control my diet.” In diaries, we saw “safe routines”—same café, same mall, same dish—emerge as coping cocoons that stabilized the day but reduced cross-cultural contact. These cocoon days did not erase the trip’s value, yet respondents’ language about Guangzhou turned practical (“convenient, efficient”) rather than affective (“crave, miss, subtle”).

Spillovers beyond the table. Breakfast mattered disproportionately as a daily hinge: when diners added one local item to the morning tray and had it land well, afternoon itineraries drifted toward local markets or neighborhood snacks; when breakfast misfired, itineraries contracted toward known brands. Frontline managers noticed the same hinge and designed buffets to present ladders (Western options adjacent to gentle local items), enabling self-paced exploration. This design is not mere hospitality; in our materials, it was a destination strategy: a good morning win often became a late-day story retold to companions, consolidating Re-anchoring in PASM.

First-timers versus repeat visitors. Repeat visitors wrote about projects (“this trip I will finally understand X”) rather than tests (“can I handle X?”). One Thai respondent noted a three-trip trajectory—chicken feet → pig’s brain → fermented shrimp paste—framed not as thrill-seeking but as craft appreciation: “I came to respect the technique.” Repeaters’ diaries contained fewer category vetoes and more conditional trials (“I’ll try the steamed version at that tea house because yesterday’s steamed dish worked”). In PASM terms, prior trips had narrowed uncertainty at Expectation, making Coping less costly.

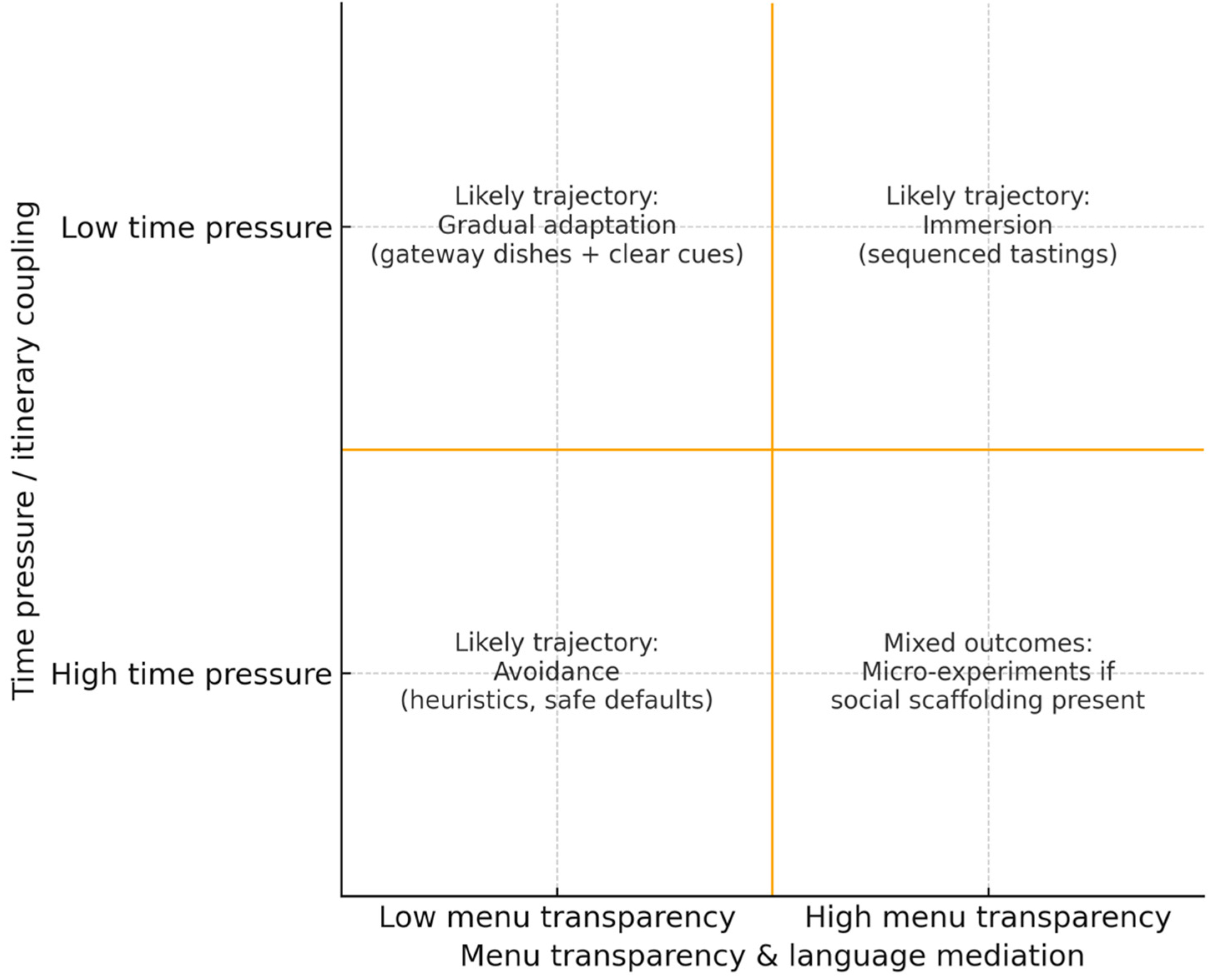

Business versus leisure framing. Business travelers faced tighter schedules and role obligations (hosting, being hosted), increasing stakes of an error at lunch. Several described conservative ordering before meetings and then bolder dinners once the day’s goals were secured. Leisure travelers, especially in pairs, had more temporal slack to repair a misfire (order a backup dish, walk back to a stall after a circuit). This difference aligns with our quadrant logic in

Figure 2: low transparency + high pressure reliably produced fallback; high transparency + low pressure permitted incremental boldness.

Memory and identity work after return. Follow-up interviews weeks later showed that successful adaptation frequently became identity talk: “I finally understand why texture matters,” “I brought rice-roll techniques home.” Some participants sought Cantonese restaurants or tried home cooking; others adopted micro-habits (a simple congee at breakfast) that kept the trip present. Where spirals had stalled, respondents remembered architectural landmarks more than tastes; where spirals had advanced, they remembered flavours by name and narrated Guangzhou as a place of culinary finesse rather than generic “Chinese food.”

Implications for destination managers. These patterns suggest interventions at PASM nodes, not generic cheerleading. At Expectation/Encounter, make menu transparency effortless (photos, ingredient lists, preparation tags). At Coping, script a one-new-dish rule and make sharing frictionless (half-portions, tasting spoons). At Re-anchoring, prompt the “next step” (“If you liked X, try Y”). Doing so increases the likelihood that food experiences become loyalty anchors rather than avoidance memories.

4.5. The Five Stages of the Palate Adaptation Spiral Model (Greatly Expanded, Aligned to Declared Methods)

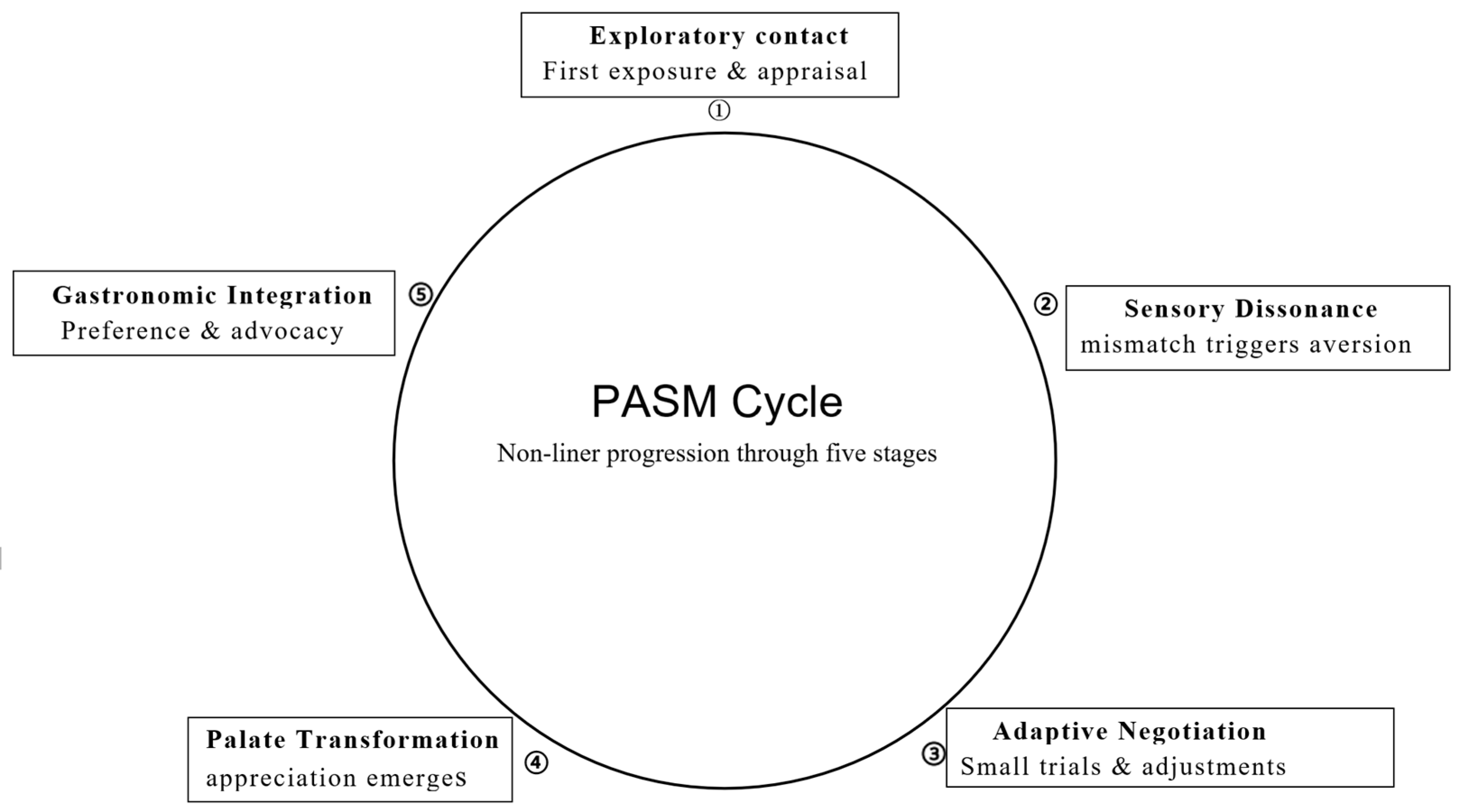

The PASM model integrates our longitudinal interviews, dining diaries, and repeated ethnographic observations to explain why the same traveler can both regress and leap forward within a few meals (

Figure 3). Culinary adjustment proceeds as a recursive loop of expectation, encounter, disconfirmation, coping, and re-anchoring illustrated in

Figure 3, see also

Table 2 for stage-wise progress and regressive factors.”.

First contacts were highly visual and social. We repeatedly observed diners scanning neighboring tables, peeking at other guests’ plates as de facto menus, and hovering over illustrated pages to anchor on familiar shapes (dumpling forms, noodle bowls, clear broths). Talk at the table focused on safety predicates (“bone-in?” “spicy?” “gelatinous?”) and portion risk (“let’s split one”). Pre-arrival expectations—based on guidebooks or prior experience with globalised “Chinese food”—shaped the meaning of what was seen; a roast’s sheen signaled “too sweet” to one diner and “balanced glaze” to another. In a breakfast scene we recorded, a diner voiced the internal debate aloud: “I want to try the market snacks later, but if this first dish goes wrong, I’ll feel off all morning.” Companions offered bounded-risk tactics—“one plate for the table,” “add a congee as a base”—and the group moved.

Where

Figure 2 attaches. Peer scripts and staff framings begin here, compressing uncertainty before the first bite.

Dissonance occurred when sensory reality (aroma, mouthfeel, aftertaste) violated the mental model carried into the meal. We recorded micro-withdrawals—pushing a plate away a few centimeters, water sips after small bites, brief silence—followed by explanatory talk (“sweetness hides the roast,” “the chew is cartilage-like”). Interviews framed the discomfort mostly as texture rather than flavour: “slimy,” “too bouncy,” “sticky,” or “a smell that arrives before the food.” Mixed-clientele restaurants described routine service adaptations for cautious visitors: smaller portions of challenging items, gentle preparations, and quiet explanations of what to expect. These adaptations did not eliminate dissonance; they bounded it, keeping diners in the loop rather than ejecting them into categorical refusal.

Why reversals happen. If dissonance hits under low transparency + high time pressure (

Figure 2), diners often retreat to anchors for the rest of the day. The same diner, under high transparency + low pressure, may accept a second attempt that afternoon.

By the third or fourth meal, many travelers authored work-arounds: pairing unfamiliar textures with familiar bases (congee, rice), requesting milder sauces, separating components, or negotiating portion sizes. A participant reflected: “I avoided the hotpot at first; with a mild broth and friends talking me through the numbing pepper, it became enjoyable.” Menus in tourist areas provided bridging language (“wood ear fungus—crunch similar to mushrooms”), which diners cited as helpful. Guides and concierges suggested pairings that preserved identity while moderating shock: roast meats with plain congee; steamed seafood before braised offal. Importantly, negotiation here is not dilution; it is scaffolding—a technique to keep the diner inside the cuisine long enough for sense-making.

Peer vicarious sampling and staff sequencing lower the threshold; time slack keeps repair (ordering a fallback) feasible.

Repeated, well-sequenced exposures produced a qualitative shift in hedonic talk and descriptive vocabulary. Early comparisons (“it’s like…”) gave way to specific sensory terms (“silky rolls that carry the soy dressing,” “roast at the edge of sweet without stickiness”). One diary entry traced the shift precisely: “Day 2: rice rolls slippery and bland. Day 6: delicate texture that perfectly carries the sauce—I can now taste the rice.” Workshops and market visits added visible labour to the mental model—soaking, skimming, gentle braising—recoding “strange” as crafted and deliberate. At this point, diners began to generalise trust: success with one steamed item spilled into confidence for other steamed preparations at the same vendor (“same cook → probably okay”).

Re-anchoring in PASM. Each small success tightens the expectation range for the next encounter; disconfirmation becomes less extreme, and Coping shifts from avoidance to exploration by default.

Weeks after returning home, several participants reported seeking out Cantonese dishes locally or recreating accessible items in home kitchens. One respondent who once struggled with congee said: “I now make rice porridge for breakfast. I even introduced preserved egg to my family.” Others wrote about showing friends how to order in Cantonese restaurants, narrating technique and texture as markers of cosmopolitan competence. Integration did not require universal love; it required ownership of a few flavours and stories that expressed respect for the cuisine’s logic.

Non-linearity, again. Even integrated diners may reject a dish later if context shifts (noisy stall, time pressure, vague menu). In PASM, this is not failure; it is the spiral revisited under new conditions.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

Across sections, EDT operates as the spine of PASM: expectation (pre-trip scripts, menu semiotics) → disconfirmation (embodied reactions) → coping (avoidance/adaptation/immersion, socially scaffolded) → re-anchored expectations for the next encounter. We show how service choreography and social cues systematically shift transitions along this loop.

This study advances the understanding of culinary culture shock (CCS) by theorising how travellers negotiate unfamiliar food environments through a dynamic, processual lens. Whereas prior food-tourism research has tended to emphasise celebratory or hedonic aspects of tasting the local (e.g., culinary authenticity, gastronomic satisfaction), our findings foreground the ambivalence, hesitation, and embodied strain that frequently accompany first encounters with unfamiliar textures, aromas, and preparation techniques. In doing so, the study complements existing accounts of food tourism’s upside with an empirically grounded explanation of when and why culinary encounters become difficult—and how tourists move through those difficulties toward accommodation or rejection.

First, we conceptualise CCS as a multi-determinant, situationally embedded phenomenon. Beyond trait-based food neophobia, tourists’ responses emerge from the joint influence of (i) cultural distance (storied norms about what is edible, appropriate, or desirable), (ii) sensory expectations (anticipated flavour–texture profiles and their violations), (iii) person-level dispositions (risk tolerance, prior exposure, dietary rules), and (iv) contextual dining factors (menu design, service scripts, social setting). Framing CCS in this way moves the literature from static, individual-difference explanations toward a trait–state interplay account in which dispositions are activated or dampened by concrete service and social contexts.

Second, our Palate Adaptation Spiral Model (PASM) offers a non-linear account of culinary adjustment. Rather than a single trajectory from “shock” to “acceptance,” we show that travellers cycle through five recurrent stages—exploratory contact, sensory dissonance, adaptive negotiation, palate transformation, and gastronomic integration—often looping back when a new dish, texture, or context re-triggers resistance. The spiral metaphor captures this recursivity and contingency: movement is possible in both directions; progress in one cuisine or dish category does not guarantee generalised acceptance elsewhere. This processual view extends linear acculturation models by theorising micro-transitions catalysed by concrete service cues (portioning, condiments, sequencing) and social cues (peer reactions, local guidance).

Third, we refine expectancy–disconfirmation theory for gastronomic contexts by specifying a visceral pathway: disconfirmation in the culinary domain is not merely cognitive (“these tastes different from what I expected”) but somatic, producing immediate bodily resistance (aversion, recoil, loss of appetite) that can overwhelm otherwise favourable cognitions about “authenticity.” We show how travellers deploy coping repertoires—avoidance, staged exposure, and immersion—to regulate this visceral dissonance, and how those repertoires are scaffolded (or frustrated) by service design and social interactions.

Fourth, the study contributes to embodied experience perspectives in tourism by documenting how tactile and textural properties of dishes (e.g., gelatinous, cartilaginous, bony) carry cultural meanings that shape destination judgements. This moves beyond cognitive appraisals of quality to theorise sensorial moralities—implicit rules about what textures count as “clean,” “fresh,” “comforting,” or “edible”—and shows how these rules travel with tourists and are negotiated in situ.

Fifth, we identify social influence as a transversal mechanism that operates across all five PASM stages. Peer modelling, local explanation, and knowledgeable intermediaries (guides, chefs, servers) modulate both the onset and dissipation of sensory dissonance, accelerating movement toward either acceptance or rejection. This extends social-learning accounts by specifying the moments of leverage (first bite, shared tasting, narration of provenance, staff-led reframing) at which social cues most effectively re-anchor expectations.

Finally, by situating Guangzhou’s culinary field as the empirical setting, the study clarifies boundary conditions. The model is most applicable where cuisines are (a) high in textural salience, (b) normatively diverse in notions of edibility, and (c) richly narrated by local actors. Under such conditions, small changes in menu semiotics (naming, imagery, sequence) and service choreography (portioning, exemplars, condiments) disproportionately shape adaptation trajectories. These conditions specify where platform or venue-level interventions should expect the largest behavioural yield.

6.2. Practical Implications

Our findings translate into operational guidance for DMOs, tour operators, and F&B providers seeking to reduce CCS without diluting culinary integrity.

First, make gastronomy a core brand pillar and communicate a comfort-to-authenticity ladder across all touchpoints (“entry/intermediate/heritage”). Then operationalise the ladder through curated tasting journeys (tours, prix-fixe, concierge paths) that move from recognisable flavour anchors to texturally or organoleptically challenging items. Within a meal, place the most unfamiliar textures after a successful anchor dish and use portioning (taster sizes, half plates) to reduce commitment costs. The brand promise (“you can climb safely”) and the service choreography (“this is how you climb”) must be inseparable.

Second, redesign menus to use plain-language descriptors of texture and intensity, discreet icons/line drawings, and brief provenance/technique micro-stories. Where translation is needed, prefer bridging terms (“wood ear fungus—crunch like mushrooms”) over literal but opaque labels, and add a compact “How locals eat it” sidebar (customary condiments, expected mouthfeel). Offer negotiation tools—modular condiment ladders, bounded heat/sweetness adjustments, and taster portions of texture-intense items—framed as regional variants or chef-recommended first steps, not “tourist versions,” so adaptations preserve culinary legitimacy.

Third, train front-of-house teams to deliver anticipatory reassurance (“the aroma comes from long simmering”), propose pairings that modulate intensity, and give micro-coaching on first bites (where to start, how to debone, what texture to expect). In parallel, engineer positive peer influence: communal tasting moments (chef’s-pass mini-bites, circulating shared plates), seating mixes that seed social modelling, and theatrical table-side reveals (steam-basket lifts, carving) that spark curiosity before contact. Normalize a “one-new-dish” challenge and make opting in face-saving and easy.

Fourth, use hotel/DMO/operator channels to deliver concise visual primers (30–60-s clips on hallmark textures/techniques), interactive menus with pronunciation and pairing tips, and micro-itineraries (“Dim Sum Day 1/Day 3/Day 5”) that mirror the ladder(

Kivela & Crotts, 2006). On site, deploy QR-linked overlays from the printed menu to short explanations or plating videos. This pre-exposure and just-in-time guidance normalise expectations, reduce first-bite surprise, and keep guests progressing along the PASM.

Finally, track low-intrusion KPIs—taster-to-full-order conversion, return-visit ordering breadth, plate-return/leftover markers for high-challenge dishes, and brief open-text feedback on texture. Run A/B tests on labels, iconography, and sequence to identify cues that unlock progression, then feed wins back into menu language, staff scripts, seating and reveal choreography. Establish authenticity guardrails (no permanent dilution; adjustments within traditional bounds) so learning improves access without eroding identity.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This inquiry used a qualitative, multi-source design (semi-structured interviews; ethnographic observation in restaurants, markets, and classes; document and diary materials). While this design enabled depth and triangulation, several limitations remain.

Scope and transferability. Findings are grounded in Guangzhou’s culinary field. Textural salience and local narratives are distinctive; generalisation to cuisines with different normative textures or service scripts should be cautious. Comparative, multi-site replications could test where PASM stages compress or expand and which leverage points travel well.

Temporal horizon. Most accounts are short-stay snapshots. Panel or return-visit designs could map whether “palate transformation” stabilises, regresses, or diffuses to other cuisine categories months later.

Individual-difference calibration. We treated food neophobia and cultural openness qualitatively. Future work should integrate validated psychometrics (e.g., food-neophobia scales; cultural intelligence) to model how dispositions interact with contextual cues to propel or stall movement across PASM stages. Mixed-methods designs could then specify thresholds at which narration or sequencing flips outcomes.

Researcher positionality and interaction effects. Ethnographic presence and the act of asking about “difficult” dishes may shape what participants notice and report. Reflexive logs and multi-researcher observation would help mitigate this, as would covert measures (e.g., unobtrusive plate-return metrics) approved under strict ethics.

Ethics and inclusion. Dietary rules, allergies, and medical conditions intersect with CCS. Future studies should more explicitly sample and theorise these non-negotiable boundaries to distinguish between culturally malleable aversions and hard constraints and to outline inclusion-first sequencing and labelling practices.

Digital mediation. While our practical section proposes pre-exposure tools, we did not empirically test them here. Experiments with menu iconography, short-form primers, or guided tasting scripts can quantify their effects on first-bite reactions, ordering breadth, and stated revisit intention.