Abstract

Alternative tourism contributes to the sustainable development of tourism and to the participation of communities in managing tourism within their territories. For this reason, it is pertinent to study the concept, characteristics, and benefits of alternative tourism, as well as its relationship with tourism competitiveness, leading to a methodology for evaluating the potential of a territory as an alternative tourism destination. The main objective of this research is to design a Sustainable Development Index in Alternative Tourism (SDIAT) based on Colombia’s tourism competitiveness indicators, which are focused on the dimensions of sustainable development, as a tool to identify the capacities of a territory associated with the development of this type of tourism. The methodology includes the application of the Delphi technique through a multidisciplinary panel of 15 experts. Two rounds have been conducted for discussion and dissemination based on the experts’ opinions, allowing consensus validation of three dimensions with their weightings and relationships, along with 21 indicators proposed for the index, which are articulated with the measurement of tourism competitiveness. The contribution lies in generating a measurement proposal applicable to different contexts that supports tourism planning and informed decision-making by destination managers, contributing to the creation of inputs for public policy.

1. Introduction

A starting point for sustainable development and alternative tourism arises from the deficient planning of mass tourism, which influences the structure of the destination and generates social differentiation (). This situation occurs in both developed and developing countries, as phenomena such as gentrification and touristification emerge (). From this perspective, the development of alternative tourism represents an opportunity to contribute to the social and economic development of a region or community, strengthened through destination management.

() argues that the alternative tourism model seeks to contribute to local economies, fostering democratization in decision-making and tourism management, which enables a more equitable distribution of the benefits generated by tourism, while seeking to minimize the impact on the environment. Therefore, in this study, alternative tourism is presented as a development option that seeks to evaluate how its potential leads to the delimitation of activities that can be carried out in a given area. On the other hand, () contend that local tourism development has a territorial connotation, in which both internal or local and external factors are present, and whose negative effects must be minimized. In this respect, the most relevant conditions are related to local government and its integration capacity for integration with the community, the effective distribution of basic services to the population, ecological planning, and the proper use of financial resources.

Based on this, the need is identified to strengthen measurement as support for decision-makers in tourist destinations, particularly emerging ones that have committed to non-mass tourism. While mass tourism can be measured with traditional sustainability indicators yielding satisfactory results, such approaches overlook fundamental relationships intrinsic to alternative tourism. According to (), there is a need to develop an index that allows destination managers to interpret information on alternative tourism in order to plan, highlight, and strengthen territories for their development and inclusion in the tourism economy. Accordingly, this research proposes the creation of an index that is consistent with the dynamics of destinations opting for alternative tourism, where the development of tourism activity is founded on minimizing environmental impacts, respecting the cultural manifestations of the host community, and promoting an equitable distribution of benefits through local governance arrangements.

The index is a synthetic indicator (a composite measure that integrates multiple variables or partial indicators), flexible and applicable to similar contexts, constructed from a study of the sector’s business dynamics from the perspective of professional decision-makers. Its design facilitates the detection of sensitive signals of socio-environmental and governance performance particularly to alternative tourism, simplifying the interpretation and comparison of multidimensional realities and, in turn, supporting decision-making in tourism management (; ).

The review of the background shows that, although there are studies on tourism sustainability, few focus directly on alternative tourism. () conduct a bibliometric review of innovations in sustainable tourism, highlighting useful indicators for the construction of indices. Complementarily, () analyzes sustainability in community-based tourism, while () propose a research agenda on community-based alternative tourism, providing conceptual references that strengthen the proposal of the present index.

Among the most common methods for its elaboration are Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Goal Programming, and the Delphi Methodology. PCA is a statistical technique that reduces the dimensionality of quantitative data, generating uncorrelated components that summarize most of the variability of the original variables (). Goal Programming, on the other hand, is an optimization method that seeks to balance multiple conflicting objectives by assigning weights and minimizing deviations from established goals (). Finally, the Delphi Methodology is a structured process of expert consultation to reach consensus on the selection and weighting of indicators, especially useful when data are limited or when qualitative knowledge needs to be incorporated ().

The Delphi method may be preferable in tourism contexts where quantitative information is scarce or subjectivity is high, as it allows the integration of expert judgment to define which indicators are most relevant and how to weight them, thereby reducing arbitrariness in the construction of the synthetic index (). Moreover, it facilitates the validation and acceptance of the indicator among key stakeholders, a fundamental aspect in destinations with multiple interests and complex dimensions (). While PCA and Goal Programming depend on numerical data and clear objectives, Delphi provides qualitative flexibility and depth, complementing quantitative approaches and enhancing the robustness of the synthetic indicator. Therefore, in studies on sustainable tourism and strategic planning, the combination or use of the Delphi method has proven to be a valuable tool for building comprehensive, consensus-based, and locally applicable indicators (; ; ), This aligns with emerging destinations and alternative tourism, and is also suitable for this research, although it is important to note that as the proposed index matures, it should be combined with quantitative approaches.

Therefore, in this study, the development of alternative tourism is considered an opportunity that can be replicated in more vulnerable communities, promoting a form of tourism that is more human than economic (). Thus, based on the relationship between alternative tourism and sustainable development, this study proposes a Sustainable Development Index in Alternative Tourism (SDIAT), using Colombia’s tourism competitiveness indicators oriented toward the dimensions of sustainable development. The index proposed in this research is a tool to evaluate the potential of a territory in relation to the development of alternative tourism, which, as discussed later, suggests small-scale tourism activities (not mass tourism), environmental protection, respect for the cultural manifestations of the host community, as well as its participation in the tourism development of its territory and, consequently, economic and social benefits. This becomes a tool for destination managers to make informed and objective decisions regarding territorial development.

2. Literature Review

() defines alternative tourism as activities developed on a smaller scale, by local providers, consequently generating lower impacts and retaining a high proportion of profits within the locality. In this way, the concept confirms that alternative tourism differs from traditional tourism in terms of the number of visitors arriving at the destination, the type of tourism providers, and the control of tourism activities, which, in the case of alternative tourism, must minimize negative impacts from environmental, cultural, social, and economic perspectives (). Moreover, this typology of tourism, in general terms, is configured as a practice that encompasses diverse modalities, which imply respecting certain criteria that promote responsible, fair, just, and solidarity-based tourism ().

() proposes a series of characteristics of alternative tourism, namely (1) the local community controls tourism development; (2) development is moderate, with most entrepreneurs being locals; (3) it is primarily focused on minimizing negative impacts on the environment and on cultural manifestations and resources; (4) it encourages the involvement of other sectors of the local economy; (5) the economic benefits of tourism activity are received by the local community; (6) it strengthens the participation of women and other vulnerable groups (such as ethnic communities) in economic activity; (7) it connects with new market segments.

2.1. Alternative Tourism and Sustainable Development

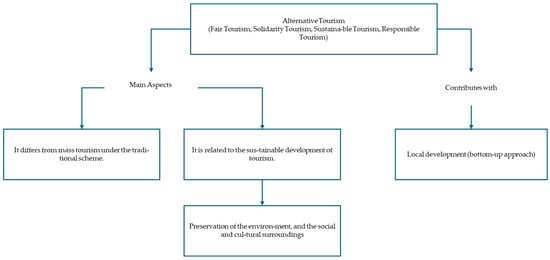

As proposed by (), alternative tourism is based on two main aspects: first, it stands in opposition to mass tourism under the traditional scheme; and second, it grounds its development in an environmental culture. This, in turn, relates to the interest in the sustainable development of tourism, which includes not only an environmental preservation focus but also social and cultural environments (). Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that alternative tourism must involve the adoption of practices different from mass or conventional tourism, fostering the development of approaches that articulate forms of coexistence in which interactions among living beings are not guided solely by economic purposes ().

In this regard, () state that local development based on alternative tourism, from the perspective of social viability, will depend on three main factors: (1) the local community’s perception of the area’s tourism potential; (2) the local community’s interest in actively participating in the process; and (3) the community’s organizational capacity. Additionally, () adds a fourth factor that would contribute to development: the local government, which leads tourism development processes through the implementation of public tourism policies, the promotion of entrepreneurship, cooperativism, and associativism, and investment in infrastructure and basic services—primarily for the benefit of the local community and secondarily for the provision of services to visitors. However, other authors warn that there is a real risk in cases where alternative tourism becomes overly focused on economic growth, thus deviating from the core objectives of this tourism approach (; ).

Likewise, some challenges have been identified for tourism service providers regarding sustainable tourism, including low levels of training among human resources in the tourism sector, limited access to investment capital, the need for faster responses to technological changes, and the strengthening of more competitive products (). For their part, () identify difficulties in managing alternative tourism that revolve around the high cost of training and educating tourists in a short period of time (during their stay at the destination), as well as the need to strengthen the preparedness of host community members in conflict resolution. This emphasizes the importance of communication following social interaction (between visitors and the local community), while highlighting a research gap in the use of qualitative approaches, mainly ethnographic methods, described by () as bottom-up local development.

In this regard, Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between concepts and characteristics of alternative tourism considered in the literature review.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of alternative tourism. Source: Based on the literature review.

2.2. Sustainable Development in Tourism

From the perspective of sustainable development proposed by () and adopted by the United Nations, () state that sustainability must encompass social, economic, and environmental factors. () support this view, noting that sustainable development in relation to tourism is framed within the direct impact generated by tourism activity on the achievement of the SDGs of the 2030 Agenda, responding directly to SDG 1 No Poverty, SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth, and SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities. Likewise, it indirectly contributes to SDG 2 Zero Hunger, SDG 5 Gender Equality, SDG 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, among others.

Given the above, within the development of tourism activity, different actors are conceived: the host community, government, public and private companies, academia, and tourists—each with the capacity to generate diverse impacts on the environment (destination). Therefore, insofar as there is conciliation among the different actors, impacts will be positive if sustainable development responds to the inseparability between the environment and human existence and development (). This requires valuing respect for nature, host communities, and actions on the environment that promote environmentally friendly practices at the destination. Thus, tourist destinations and their actors must be concerned with maintaining the capacity and quality of their natural and social resources in the long term ().

Achieving sustainable development in a tourist destination must be economically profitable, without damaging the physical and social environment, while meeting the needs of populations hosting an increasing number of tourists (; ). These populations, due to the greater flow of information and market dynamics, increasingly seek destinations consistent with the perspective of sustainable development (). This increase in demand allows for economic profitability, while the responsibility of maintaining the value promise of a sustainable destination lies with supply-side actors (). For this reason, consensus has been reached on variables that contribute to measuring the three dimensions of sustainable development.

2.2.1. Environmental Dimension

According to (), sustainable tourism must pursue environmental and landscape conservation through the prudent use of natural resources, the preservation of biodiversity (flora and fauna), and the protection of natural habitats. The conservation of the natural environment is essential for achieving memorable experiences and increasing tourists’ commitment to the destination. () note that landscape aesthetics are related to the natural attributes of the place, such as tropical forests, valleys, islands, and savannas, among others, which can generate connections with tourists; panoramic views and open spaces are also relevant. Similarly, () highlight the need for a quality environment (air, water, soil, temperature, among others), which also includes the quality of destination services (basic and tourism services), such as cleanliness of public areas and pollution levels. Therefore, environmental quality and its preservation constitute conditional factors for the successful development of the destination (; ; ). In this context, long-term sustainable development requires not only the efficient use of natural resources but also an accurate assessment of the direct impact generated by tourism activity in the areas where it takes place.

In addition, () emphasizes the importance of environmental preservation and consumption control from an ecological perspective. The author argues that the use of natural resources (especially energy resources) is the most important component to consider in the strategies for developing alternative tourism, in order to guarantee long-term sustainability and avoid soil degradation.

From the environmental perspectives of sustainable tourism development, cultural heritage and natural, marine, and wildlife biodiversity must also be protected (). () recognize natural resources such as energy, water, landscape, and biodiversity as essential components of a destination, and warn that overuse of these resources can cause deterioration and loss of tourism attractiveness due to congestion and excessive use. From this standpoint, recycling and regeneration rates of renewable resources are considered appropriate to demonstrate efforts in managing consumption and emissions, as well as being indicators of responsible destination and tourist management.

In this regard, () highlights the following aspects for the selection of construction materials with the purpose of protecting the environment of the territory where buildings will be constructed: “use of resources from the area where construction will take place (regional or local materials), increasing the useful life of materials, use of easily renewable materials that produce low environmental impact, recycling/reuse of construction materials (energy recovery), use of renewable or recycled components and energies, utilization of urban or industrial waste, and reduction in toxic components.”

2.2.2. Economic Dimension

In his study, () begins with the recognition of economic differences, which are considered necessary for social development. The author argues that alternative tourism stakeholders must be influenced by the tourism development of the community; that is, development is not only achieved by enhancing cultural characteristics but also requires valuing local traditions in the economy. Tourism practices should be considered for the creation of economic options in community development, which need to be collectively negotiated so that economic, social, and environmental benefits are generated.

Within the economic dimension, one of the main factors identified relates to income generation, resulting from opportunities developed through tourism, as tourism is understood as an activity that involves intensive labor, producing direct, indirect, and induced economic benefits for the local sector, thus aligning with several SDGs. One of the main indicators for measuring the economic development of this activity is the generation of jobs and income (). Tourism development can be measured in terms of the creation of new jobs and their current levels associated with tourism activity, income growth, and the improvement and access to basic services available, such as health, education, culture, and a reduction in inequality ().

Furthermore, destination management includes communications and their systems as part of the necessary infrastructure to generate economic benefits (). Poor communication among stakeholders, the local government, and the central government may lead to inadequate policies for environmental and sustainable destination management, reflecting inefficiency in management and hindering the provision of more competitive activities that generate added value for the territory ().

Within this dimension, two elements are discussed: the flexibility of the tourism offer and the costs for tourists. The first refers to the availability of time within a year to carry out leisure and tourism activities (public holidays in each country), which may represent an opportunity to generate flexible job offers outside the high season (). The second, costs for tourists, is initially developed within the conception that sustainability is more of a cost than an investment, without understanding that sustainable development is a crucial factor for the competitive development of a tourist destination. Public policy must therefore work on creating conditions for an affordable tourism offer in terms of costs for tourists, where service quality will largely depend on committed and qualified employees ().

2.2.3. Social Dimension

From a planning perspective, different scales exist—international, national, regional, or local—which must be aligned for the development and management of tourism activity. This implies integrating tourism into society and into economic, social, and environmental dynamics, focusing on leveraging both internal and external strengths of the environment. () indicates that environmental problems are created by people and their communities, which is why there is a need to involve the local community in tourism dynamics, holistic tourism planning, and the development of sustainability strategies. In this sense, as Louis-Joseph, cited by (), mentions, local community development (LCD) emphasizes the creation of connections among economic, social, and cultural factors that enhance identity, resilience, and sustainability capacities within the community. This directly promotes efforts toward the conservation of ecological processes and the protection of heritage and biodiversity.

From this planning process arises the identification of cultural attractions and their impacts, leading to a long-term vision. Planning processes have evolved, introducing ideas of local community participation, an understanding of cultural value systems, the involvement of social acceptance as part of the commitment to protecting local resources, and the creation of local economic benefits (). According to (), when sustainable tourism is addressed, social and economic benefits for destination residents are expected, which is linked to social satisfaction and acceptance of the activity. This relates to local culture and values, conservation of natural resources, and tourist satisfaction, highlighting the importance of envisioning the tourism industry through economic, social, and environmental lenses. These perspectives frame reflections on tourism practices in line with the principles of Sustainable Development ().

These ideals of sustainable development must be supported by logistical processes related to destination accessibility and its natural resources (), cultural diversity associated with the geographical and social environment (), and security (). This includes addressing barriers that currently limit tourism activities for some population segments due to deficient destination management. For example, the right of people with disabilities to a barrier-free environment, including freedom of movement and equal access to cultural and historical assets (). Furthermore, security is one of the aspects of destinations that determines tourism competitiveness, since potential tourists may be influenced in their travel decision by the safety conditions of the place and protection services such as police coverage (). Nevertheless, accessibility to the destination plays a fundamental role in tourism development. In this sense, the () includes variables related to air, land, and port connectivity, emphasizing the quality of transport infrastructure, in accordance with international guidelines on safety, efficiency, and comfort.

2.3. Tourism Competitiveness for the Sustainable Development of Tourism

The World Economic Forum (WEF) defines competitiveness as the set of factors, policies, and institutions that determine a country’s level of productivity. () explain that competitiveness is based on classical economics, where it is understood as a set of resources in a given social, economic, and political context, and productivity as the result of managing these resources, interpreted as the level of prosperity an economy achieves (). On the other hand, (), cited by (), define competitiveness as the ability to increase tourism expenditure and thereby naturally attract more tourists—through effective destination management—while providing memorable, adaptable, and satisfactory experiences tailored to their needs. This directly impacts locals’ quality of life and increases the destination’s capital for future generations.

From a business perspective, () states that competitiveness is the ability of an entrepreneur or a country to design, produce, and market products (goods and services) more attractively than competitors. Thus, competitiveness is relative and multidimensional. It should be clarified that competitiveness is not an end in itself but rather a means to achieve the objective of improving conditions for the local community (). In this regard, () suggest that economies must generate the necessary conditions to obtain not only economic but also social and environmental gains.

Accordingly, () stress that tourism competitiveness must include increased tourism revenues and a positive impact on the host community, considering tourism as an alternative to improve local living conditions while addressing environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and economic prosperity (). Research on tourism competitiveness is of great interest and relevance since it allows establishing the tourism potential of a destination in relation to others by identifying and analyzing its comparative and competitive advantages (). Regarding the measurement of tourism competitiveness, most countries rely on the methodology proposed by the World Economic Forum, despite some criticisms related to the lack of standardization for direct comparison among indices (). Nevertheless, these tourism competitiveness monitors are fundamental tools for tourism planning and the strategic management of destinations ().

In this regard, sustainability is not only related to the competitiveness of a destination but also plays a key role in strengthening it (). Through its economic, social, and environmental dimensions, sustainability contributes to the differentiation of a destination (), enhances the tourist experience by ensuring the long-term preservation of resources, and attracts more conscious travelers, which ultimately reinforces the competitive position of the destination (). Such destinations generate greater benefits for the local community while simultaneously increasing their attractiveness and resilience (). Although the conceptual evolution of this relationship is recognized, challenges still persist, such as effective measurement (), stakeholder coordination, and adaptation to different socioeconomic contexts, which are essential for the long-term success of destinations ().

Sustainability positively influences the competitiveness of tourism destinations and businesses by enhancing image, reputation, and consumer preference (). Previous studies have shown that sustainability leads to better competitiveness outcomes, even surpassing traditional factors (). At the same time, it enables access to new markets, fosters customer loyalty, and reduces risks associated with resource dependency—representing competitive advantages that are further reinforced by innovation processes and efficient resource management ().

2.4. Measuring Tourism Sustainability

The question of how sustainable tourism should be measured defies a single answer and lies at the intersection of scientific validity, governance, and the social appropriation of knowledge. On the one hand, the literature warns that across the research cycle—from asking the right questions to ensuring reproducibility—up to half of the effort may be wasted if end-users are not engaged early (). On the other hand, community-based experiences show that resident involvement in the design, collection, and reporting of indicators enhances relevance, strengthens negotiation with authorities, and counters non-neutral measurement agendas (). The integration of public decision-makers contributes policy-cycle knowledge and more strategic data use, yet encounters tensions between short political horizons and sustainability needs, as well as the dilemma between comparability and local specificity (; ).

In parallel, expert panels can produce robust systems, while multi-stakeholder participatory schemes introduce explicit weightings through “power indices” that render visible—though may also reproduce—pre-existing asymmetries of influence in decision-making (). Taken together, the evidence suggests that the most credible measurement emerges from polycentric arrangements that combine community participation, technical leadership, and articulation with public policy under clear rules for transparency, data quality, and accountability, thereby minimizing research “waste” and maximizing the social utility of indicators (). The literature converges that indicators and composite indices are useful to operationalize sustainable tourism and to support evidence-informed decisions by translating complexity into comparable metrics, provided they rest on rigorous, validated designs (; ). Nonetheless, a triple tension persists: (i) scale of application—standardization for comparability versus local adaptation for contextual relevance—without a universal optimum; (ii) selection and measurement—primacy of the “measurable” over the “material,” compounded by sociocultural and environmental data gaps; and (iii) authorship—community and territorial actor participation versus technical expertise and politico-institutional steering—each with distinct advantages and limits.

Evidence further indicates that while indicators have increased literacy and deliberation on sustainability, their translation into concrete policy change remains modest, functioning more as enablers of dialogue than as direct drivers of transformation (). Consequently, indicator development should bridge global and local scales, broaden thematic coverage with valid metrics, strengthen governance and data infrastructure, build technical capacities, and integrate multi-actor participation and emerging technologies responsibly to close the measurement–action gap.

In this context, proposing a Sustainable Development Index for Alternative Tourism is both pertinent and necessary: it translates a complex problem—encompassing scientific validity, governance, and social ownership of knowledge—into an operational, comparable metric that supports evidence-based decision-making, reduces research waste across the project cycle, and explicitly manages tensions between standardization and local specificity as well as between expert authorship and community participation. Although this study privileges expert authorship, it adopts a polycentric approach via the Delphi technique and aligns with tourism-competitiveness indicators, thereby reinforcing methodological rigor, legitimizing multi-actor weightings, and orienting management toward closing the measurement–policy gap. The resulting instrument provides concrete inputs for planning, investment prioritization, and performance evaluation in destinations seeking to consolidate non-mass, inclusive, and environmentally responsible modalities.

3. Materials and Methods

The research focuses on the proposal of a Sustainable Development Index in Alternative Tourism (SDIAT), carried out as an exploratory qualitative study. The indicators selected for the dimensions and variables are drawn from the Regional Tourism Competitiveness Index of Colombia (ICTRC), which is aligned with the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index proposed by the (). To achieve the objective, the Delphi method is applied, a technique that has been used in previous studies to reach consensus (; ), given its relevance as a method of social validation and its proven usefulness in addressing complex issues (). The method begins with a theoretical pre-selection of dimensions and variables, following proposals such as (), based on the collection of theoretical contributions suited to the context of the research. This research adopts a qualitative exploratory design () appropriate for contexts where theoretical constructs are still being developed and empirical data are limited. The study aims to generate an initial approximation to the construction of a measurement index by consulting expert judgment through the Delphi technique ().

In selecting the expert panel, emphasis was placed on the need for balance across different contexts, namely academic, business, and governmental. This heterogeneous participation enables the problem situation to be approached from a comprehensive perspective with a high level of expertise on the subject. For this reason, authors such as () consider a sample of 10–15 experts to be sufficient. The sampling is non-probabilistic and based on convenience, due to the need to ensure that the profiles of the experts meet the thematic experience criteria. Participants were contacted via email and telephone calls to explain the project and confirm their participation. Follow-up calls were conducted throughout the process (see Table 1 for the characteristics of the panel).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the panel participants.

In the process of forming the expert panel convened for the Delphi technique exercise, a balance was deliberately ensured in the representation of the three perspectives included in the panel. Each of the expert categories (academics, business professionals, and government-affiliated experts) was allocated 33% of the seats on the panel. This balance facilitated the integration of these perspectives and enabled them to be viewed as complementary. The contributions of each group highlighted distinct strengths: the academic experts provided theoretical and methodological rigor; business professionals contributed expertise and pragmatism derived from practical experience; and government actors brought a strategic orientation within the regulatory context.

Each participant was asked to rate, from their perspective and experience, first, the weightings associated with the relevance of the dimensions of sustainable development in alternative tourism, the identification of competitive and comparative advantages for each of the selected variables, as well as their relative weights. The analysis reveals a convergence around the environmental and social dimensions of alternative tourism, although perspectives vary by sector. Academics prioritize ecological sustainability and community cohesion as drivers of innovation and governance, while business leaders approach it from a profitability standpoint, integrating ESG criteria and authenticity as sources of reputational value. Governments view it as a tool for territorial development and resilience, and NGOs emphasize regeneration and community participation. Overall, alternative tourism emerges as a hybrid model where conservation, equity, and innovation coexist with the pursuit of competitiveness.

Variables were classified according to their nature: comparative advantages were associated with the natural and cultural resources inherent to the territory (such as landscape, air quality, or biodiversity), while competitive advantages reflected the management capacities, planning, and institutional coordination (such as accessibility, employment, or recycling). This classification enabled an analysis not only of what the territory possesses, but also of how it manages and enhances those resources in line with the sustainable development of alternative tourism.

The weight assigned to each dimension of sustainable development reflects a consensus reached by the participating panel members, based on its relevance in the context of alternative tourism. This consensus is the result of two rounds of feedback, in which the convergence of perspectives and priorities among participants—from academia, government, and the private sector—represents not only individual preferences but a collective agreement that legitimizes both the structure and the relevance of the proposed index ().

These weightings were expressed as percentage points, with a maximum total of 100%. Based on the responses, a final selection was made considering the mean of the answers.

where d is the variables associated with sustainable development, j is the dimension of sustainable development (environmental, economic, and social), i is the number of variables taken from the ICTRC or measured through other methods, xc is the variable from the ICTRC or measured through other methods, and z is the observed area or tourist destination

where iD is the Index of the sustainable development dimension, k1 is the weighting of the competitive advantage, k2 is the weighting of the comparative advantage, l is the number of variables associated with the sustainable development dimension, and p is the percentage weight assigned to d according to its relevance in the calculation of the variable

where IDSTA is the sustainable development index in alternative tourism and q is the level of relevance of the sustainable development dimension (j).

The selection of environmental, economic, and social variables follows the sustainable development framework that integrates ecosystem conservation, economic viability, and sociocultural cohesion, in line with the SDGs and with multi-actor destination governance. Thus, Table 2 presents the dimensions of sustainable development in tourism, the associated variables, and the authors supporting them.

Table 2.

Dimensions and variables of sustainable development in alternative tourism.

In alternative tourism contexts—typically small-scale and strongly rooted in place—soil quality becomes a key differentiator compared with mass destinations because it conditions ecological functioning (infiltration, fertility, resilience) and the landscape integrity upon which nature- and culture-based experiences are built. Together with landscape aesthetics, air and water quality, energy consumption, biodiversity, construction materials, and recycling, this variable enables a fine-grained assessment of destination pressure and carrying capacity, guiding low-impact and circular-economy practices. Thus, the environmental block not only monitors “state” and “pressure” but also provides early signals for the adaptive planning these destinations require to uphold their value proposition and avoid degradation pathways typical of mass tourism.

In the economic dimension, variables such as income, service provision, communications, employment level, supply flexibility, and costs for tourists capture the destination’s capacity to generate local added value efficiently and resiliently. In emerging destinations based on alternative tourism, supply flexibility functions as a differentiating factor because it allows portfolios, calendars, and local value chains to adjust to seasonality, shocks, and niche preferences without compromising socio-environmental standards; this favors decent jobs outside the high season, affordable prices, and a better distribution of rents toward local MSMEs. In parallel, the endowment and quality of services and communications enable low-footprint, knowledge-intensive business models (e.g., specialized guiding, heritage interpretation), while managing costs for tourists contributes to competitiveness without shifting overuse pressures onto ecosystems.

In the social dimension, alignment with national/regional planning, accessibility, community participation, cultural diversity, social acceptance of the activity, social satisfaction, heritage, and safety each gauge, to some extent, the community’s consent for tourism and its alignment with territorial values. In alternative destinations, social satisfaction synthesizes local perceptions of benefit distribution, cultural respect, and effects on everyday life, operating as a signal of legitimacy and reputational risk. Moreover, coherence with planning instruments, inclusive accessibility, and safety strengthen social cohesion and the visitor experience. Transversally, these variables reflect governance and participation practices: community participation shapes acceptance and satisfaction; concerted planning guides investment and rules of use; and safety, together with heritage management, requires collaborative arrangements among the state, community, and businesses—core elements for alternative tourism to uphold its sustainability promise.

3.1. Delphi Method

The Delphi method is a process aimed at reaching consensus among a group of experts on a specific topic. According to (), this method is characterized by the anonymity of participants, the iteration of the process in each round, controlled feedback, and the provision of a statistical response that enables data interpretation and analysis. Consensus is achieved once a stable response from the panel members is reached, when all items in the questionnaire have been either approved or rejected, or when the mean is greater than 3.5 (). During the process, experts receive controlled feedback to allow the reevaluation of ratings, following the proposal of ().

The present study includes a sample of 15 participants, which is consistent with exploratory studies that employ the Delphi technique (; ; ). () emphasize that smaller, carefully selected panels are appropriate in qualitative research contexts where depth of insight is prioritized over sample size. Nevertheless, the study acknowledges the panel size as a limitation. Future phases of the research will incorporate broader participation to ensure greater representativeness and contextual relevance, particularly during the validation and testing stages of the index.

3.1.1. First Round—Weighting of Relevance by Dimension for Alternative Tourism (pi) and Variables

Through a formal invitation sent to the panel members, an initial questionnaire was distributed to evaluate the weighting of sustainable development dimensions, the identification of comparative and competitive advantages, and their weights. Each expert returned the questionnaire for the collection and categorization of information. In this round, participants in Phase 1 were asked to indicate the relevance weighting for each sustainable development dimension (j), taking into account that the sum of the three dimensions must equal 100% (responses had to be given in integer multiples). In Phase 2, participants had to select, for each of the variables (d) associated with the SD dimensions, whether it corresponded to a competitive or comparative advantage for the tourist destination. In Phase 3, participants assigned a percentage weight for each variable considered within the dimension, with the total sum of weights adding up to 100% for each SD dimension.

3.1.2. Second Round—Confirmation of Response and Position

In the second round, experts were provided with feedback on the results obtained in the first round and were asked to either confirm their position/response or modify it according to their perspective and expertise, both in terms of weighting the dimensions and variables and in the selection of competitive and comparative advantages.

It is important to clarify that this study corresponds to the conceptual design phase of the Sustainable Development Index in Alternative Tourism (SDIAT). As such, it focuses on the theoretical structuring and expert-based validation through the Delphi method, without advancing into the empirical validation phase. The pilot implementation of the index is planned for a subsequent stage of the project, which will involve additional stakeholders and testing in selected territories to assess its practical relevance and reliability in real-world settings.

4. Results

Within the framework of the Delphi method, the way alternative tourism is conceived shows clear contrasts among academia, the business sector, governments, and NGOs. From the academic sphere, the emphasis falls mainly on the environmental dimension (30–50%). Here, only 3 out of the 19 variables are understood as competitive advantages, and priority is given to ecosystem conservation, community innovation, and social cohesion over immediate profitability. This sector proposes tools such as environmental impact metrics, responsible accommodation policies, local knowledge networks, feedback systems between guests and communities, and regenerative objectives that aim for a net-positive balance.

In contrast, the business sector concentrates between 50% and 55% of the weighting on the economic dimension and recognizes 13 competitive advantages, viewing alternative tourism as a premium niche or a diversification pathway. Its strategy focuses on packaging green experiences, monetizing authenticity, standardizing ESG data, and linking customer loyalty to sustainability. NGOs and the government sector assign between 35% and 45% of importance to the environmental component (12 competitive advantages) and view alternative tourism as a tool for ecosystem restoration and community empowerment. Their actions focus on eliminating the use of plastics, achieving carbon balance, promoting community certifications, and fostering bio-regional narratives.

Table 3 and Table 4 present the weighting by dimensions and variables, as well as the identification of competitive and comparative advantages. From this perspective, alternative tourism is understood as a driver for rural development, resilience, and territorial revitalization, leading to the promotion of incentives, observatories, and master risk management plans.

Table 3.

Weighting of relevance for each dimension.

Table 4.

Identification of Competitive and Comparative Advantages Based on the Variables of the Sustainable Development Dimensions.

The analysis of the Delphi panel, according to Table 5, shows that in the environmental dimension, there is broad consensus around those variables considered comparative advantages, such as landscape aesthetics, air, water, and soil quality, as well as biodiversity. However, only three elements—energy consumption, construction materials, and recycling alternatives—reach the category of competitive advantage. This highlights that environmental factors are perceived more as basic requirements than as elements capable of strategically differentiating destinations. In contrast, within the economic dimension, most variables—income, service provision, communications, employment, and flexibility of supply—are classified as competitive advantages. This result confirms the panel’s orientation toward economic value generation as the main driver of competitiveness in alternative tourism, with costs to tourists remaining a merely comparative aspect.

Table 5.

Weightings of Competitive and Comparative Advantages by Variable.

Meanwhile, in the social dimension, a more balanced situation is observed. While community participation and social satisfaction remain in the category of comparative advantages, other variables related to territorial planning, accessibility, cultural diversity, social acceptance, cultural heritage, and security are recognized as competitive advantages. This pattern reinforces the relevance of social factors as pillars of differentiation for destinations. These findings suggest that the competitive model of alternative tourism is mainly supported by the economic dimension and social cohesion, relegating the environmental component to the role of a necessary but insufficient condition for achieving true differentiation.

The application of the Delphi technique in the creation of a Sustainable Development Index for alternative tourism enables the structured integration of expert perspectives, considering both the comparative and competitive advantages of a territory. In Colombia, cultural landscapes, biodiversity, and natural resources represent the comparative base for differentiating destinations. However, the true potential of alternative tourism relies on the management capacity to transform these assets into competitive advantages through strong community organization and governance. Thus, tourism competitiveness is not defined solely by resource availability but by the community’s ability to manage them sustainably, creating authentic experiences that promote local development. The structured Delphi approach, by collecting diverse and informed expert consensus, supports the formulation of indicators that reflect not only the richness of the environment but also institutional maturity, management capacity, and social responsibility in tourism offerings.

5. Discussion

The findings obtained through the Delphi method closely align with the theoretical framework of sustainable tourism development proposed by the () and recently revisited by (). The results confirm that the different actors in the tourism system recognize the interdependence between the environmental, social, and economic dimensions, although they rank them differently. The priority given by academia and NGOs, or government entities, to the environmental dimension reflects a marked concern for the conservation of natural resources, biodiversity, and ecological impacts. This perspective coincides with what was stated by () and (), who advocate for the responsible use of resources and the preservation of landscapes as fundamental bases for long-term competitiveness. However, the evidence also shows that, in practice, these environmental variables are treated more as basic requirements than as true competitive factors, which creates tension with the principles of the 2030 Agenda regarding the integration of sustainability as a central axis of tourism planning. This finding raises questions about the real capacity of stakeholders to move beyond a logic of mere impact management toward the active regeneration of ecosystems, an aspect that constitutes a pillar of sustainable tourism.

On the other hand, the priority orientation of the business sector and the intermediate weighting given by governments confirm the assertions of () and (), who point out that, in order to be viable, sustainable tourism must also be economically profitable and generate tangible benefits for communities. The variables with the greatest weight in the economic dimension—income, employment, service provision, communications, and flexibility of supply—are directly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals linked to economic growth, poverty reduction, and social equity. Likewise, in the social dimension, factors such as territorial planning, safety, and cultural diversity reinforce the arguments of () and () about the importance of local community development (LCD) as a basis for resilience and social cohesion.

Overall, the results of this study confirm that alternative tourism constitutes a strategic space for the materialization of the principles of sustainable development in destinations. Nevertheless, they also highlight the need to advance toward collaborative governance mechanisms that articulate the interests and priorities of the different actors, as proposed by (), in order to prevent any of the three dimensions from being subordinated to the others.

6. Conclusions

The results obtained show that alternative tourism constitutes a relevant strategy to promote sustainable development in tourist destinations, provided that an adequate articulation between the environmental, economic, and social dimensions is achieved. Through the use of the Delphi technique, it was possible to design a Sustainable Development Index in Alternative Tourism (IDSTA), which allows the potential of territories in this type of tourism to be assessed. The consensus reached by the experts highlights the importance of the environmental component as a necessary condition for responsible tourism development, while also recognizing that the economic and social factors are those that enable the consolidation of competitive and sustainable processes over time.

It is important to note that the proposed model is designed to be adaptable. While the dimensions of sustainable development—environmental, economic, and social—are universal and conceptually stable, the specific variables and indicators within each dimension can be adjusted and contextualized to reflect the unique characteristics, priorities, and capacities of different territories. This flexibility allows the index to be applied in diverse destinations while maintaining methodological coherence and local relevance.

Nevertheless, the research also shows that, although there is broad awareness of the importance of the environmental component, it is mainly perceived as a basic requirement rather than a true source of differentiation. In this sense, the findings indicate the need to move toward public policies and governance mechanisms that integrate the different actors of the tourism system, in order to balance priorities and ensure that alternative tourism is consolidated as a driver of local development, social inclusion, and environmental protection. The proposed methodological approach paves the way for future applications in other geographical contexts and provides inputs for strategic decision-making in tourism planning processes.

The contribution of this index to the tourism sector will materialize in the generation of metrics that strengthen the strategic planning process, starting from baselines that allow sector managers to measure, plan, and manage sustainable tourism in the country. Applying the index will make it possible to obtain an assessment of the conditions of each territory with its specificities, based on the identification of development gaps, thus providing support for the formulation of public policies tailored to and consistent with the realities of the territory.

Alternative tourism offers a unique opportunity to promote equity and social inclusion by creating fairer conditions for participation and benefit-sharing among the various stakeholders within a territory. Unlike conventional tourism, this approach recognizes and values traditional knowledge, local wisdom, and community ties, allowing women, Indigenous communities, and informal workers to be actively integrated into the tourism value chain. These historically marginalized groups can benefit through solidarity economy models, self-managed enterprises, decent employment, and involvement in decision-making processes. Thus, alternative tourism contributes not only to economic development but also to social and cultural empowerment, strengthening local identities and reducing inequality gaps.

The IDSTA index decisively contributes to the visibility of a viable development model in all aspects required for the performance of the sector—social, environmental, and economic—in harmony with the principles of conservation, inclusion, and competitiveness. It contributes to balanced management aimed at improving the quality of life of the territories that commit to this type of tourism. Future phases should consider expanding the panel to include social actors, whose voices are essential for capturing grassroots perspectives. Their inclusion would enrich the index by incorporating community-based insights into sustainability and tourism governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.O.-C. and L.M.P.-D.; methodology, I.A.O.-C.; validation, I.A.O.-C., L.M.P.-D. and X.F.V.-T.; formal analysis, I.A.O.-C. and L.M.P.-D.; investigation, I.A.O.-C. and L.M.P.-D.; resources, I.A.O.-C.; data curation, I.A.O.-C. and L.M.P.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.P.-D.; writing—review and editing, I.A.O.-C. and X.F.V.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Consejo Profesional de Administración de Empresas (CPAE) and the Universidad de San Buenaventura, under the framework of the Ponte RegiON 2024 call, through the Association Agreement No. 07 of 2024 [(Grant Number: CPAE-USB-07-2024)]. The APC was funded jointly by the Consejo Profesional de Administración de Empresas and the Universidad de San Buenaventura.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de San Buenaventura Cali (protocol code CieEco2-II-2022, approved on 12 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participants were fully informed about the objectives of the research, and confidentiality and responsible use of data were guaranteed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This article is the result of a research project developed under the Ponte RegiON 2024 call, co-financed by the Consejo Profesional de Administración de Empresas (CPAE) and the Universidad de San Buenaventura. The authors especially thank both institutions for their financial and academic support, as well as all participants and collaborators who made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Adongo, C. A., Taale, F., & Adam, I. (2018). Tourists’ values and empathic attitude toward sustainable development in tourism. Ecological Economics, 150, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A., & Mitra, S. (2012). A methodology for assessing tourism potential: Case study Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 2(9), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Masroori, R. S. (2006). Destination competitiveness: Interrelationships between destination planning and development strategies and stakeholders’ support in enhancing oman’s tourism industry. Griffith Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Alsheref, F. K., Khairy, H. A., Alsetoohy, O., Elsawy, O., Fayyad, S., Salama, M., Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Soliman, S. A. E. M. (2024). Catalyzing green identity and sustainable advantage in tourism and hotel businesses. Sustainability, 16(12), 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza-Panca, C., Franco, J., Cornejo, J., Maquera-Luque, P., Poma, D., Epiquen, A., & Sifuentes, L. (2025). Social perception of the tourist use of the El Angolo Hunting Preserve: Future of alternative tourism. Journal of Posthumanism, 5(5), 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baros, Z., & Dávid, L. (2007). A possible use of indicators for sustainable development in tourism. Anatolia, 18(2), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzekar, G., Aziz, A., Mariapan, M., Ismail, M. H., & Hosseni, S. M. (2011). Delphi technique for generating criteria and indicators in monitoring ecotourism sustainability in Northern forests of Iran: Case study on Dohezar and Sehezar Watersheds. Folia Forestalia Polonica, Series A, 53(2), 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra Gualdrón, S. B., Cruz Vásquez, J. L., & Gallardo Sánchez, C. F. (2024). Indicadores ambientales para el turismo sostenible en San Gil—Colombia: El punto de vista de los actores locales a través del método Delphi. Revista de Estudios Regionales, 3(131), 49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Blancas, F. J., Lozano, M., Casas, F. M., & Oyola, M. (2010). Indicadores sintéticos de turismo sostenible: Una aplicación para los destinos turísticos de Andalucía. Revista Electrónica de Comunicaciones y Trabajos de ASEPUMA, 11(1), 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future: Report of the world commission on environment and development. Geneva, UN-Dokument A/42/427. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Cabezas-Correa, L. C., Vieira Salazar, J. A., & Echeverri Rubio, A. (2022). Turismo alternativo de base comunitaria: Agenda futura de investigación. Cuadernos de Turismo, 49(2), 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, R. (2013). Sostenibilidad y turismo: De la documentación internacional a la planificación en España. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 61, 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, I., & Glasziou, P. (2009). Avoidable waste in the production and reporting og research evidence. Lancet, 374(9683), 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Dagostino, R. M., Maoldonado, O. A., Ramos, K. J., & Espinoza, R. (2015). ¿Puede el turismo alternativo potenciar el desarrollo local en Latinoamérica? Spanish Journal of Rural Development, 6(1), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-K., & Kuo, H.-Y. (2015). Bonding to a new place never visited: Exploring the relationship between landscape elements and place bonding. Tourism Management, 46, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chim-Miki, A., Batista-Canino, R., & Medina-Brito, P. (2016a). La competitividad nacional del sector de turismo: Una comparación de la medida interna vs la medida externa. Revista Turydes: Turismo y Desarrollo, 9(20), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chim-Miki, A., Castillo-Palacio, M., & Gadotti dos Anjos, S. (2016b). Competitividad y producción turística: Diferentes medidas de la evolución del destino. Revista Gestión and Desarrollo, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, H., & Parpairis, A. (2000). Tourism and the environment: Some observations on the concept of carrying capacity. In H. Briassoulis, & J. V. Straaten (Eds.), Tourism and the environment (pp. 91–105). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A., & Noakes, S. (2012). Towards an understanding of the drivers of commercialization in the volunteer tourism sector. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(2), 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracolici, M., & Nijkamp, P. (2009). The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A study of Southern Italian regions. Tourism Management, 30(3), 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R., & Kubickova, M. (2013). From potential to ability to compete: Towards a performance-based tourism competitiveness index. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 2(3), 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M., & Goffi, G. (2016). Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian destinations of excellence. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111(Pt B), 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoska, T., & Petrevska, B. (2012, September 13–15). Indicators for sustainable tourism development in Macedonia [Conference Proceedings]. First International Conference on Business, Economics and Finance “From Liberalization to Globalization: Challenges in the Changing World” (pp. 289–400), Stip, North Macedonia. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Padilla, V. T., Travar, I., Acosta-Rubio, Z., & Parra-López, E. (2023). Tourism competitiveness versus sustainability: Impact on the World Economic Forum model using the Rasch methodology. Sustainability, 15(18), 13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, G. G., & Andrade, M. A. (2017). Desarrollo sustentable: Estrategia en las empresas para un futuro mejor. Alfaomega. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza-Huamanchumo, R. M., Botezan, I., Sánchez-Jiménez, R., & Villalba-Condori, K. O. (2024). Ecotourism, sustainable tourism and nature based tourism: An analysis of emerging fields in tourism scientific literature. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 54(2), 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, I. (2023). Explorando el nexo entre la gobernanza del turismo sostenible, la resiliencia y la investigación sobre la complejidad. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(3), 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, Y., & Prastacos, P. (2001). Sustainable tourism indicators for Mediterranean established destinations. Tourism Today, 1, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández López, R., Vilalta Alonso, J. A., Quintero Silverio, A., & Chávez Gomis, R. M. (2020). Indicador sintético mediante el análisis multivariado de la varianza aplicado al sector turístico. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 8(1), 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, M. L., & Mariotti, A. (2023). Sustainable tourism indicators as policy making tools: Lessons from ETIS implementation at destination level. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1719–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gândara, J., & Chim-Miki, A. (2016). Destination evaluation through the prioritization of competitiveness pillars: The case of brazil. In A. Artal-Tur, & M. Kozak (Eds.), Destination competitiveness, the environment and sustainability: Challenges and cases (pp. 24–39). CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Goffi, G., Cucculelli, M., & Masiero, L. (2019). Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R., Zuñiga-Collazos, A., Castillo-Palacio, M., & Padilla-Delgado, L. M. (2023). An exploratory attitude and belief analysis of ecotourists’ destination image assessments and behavioral intentions. Sustainability, 15(14), 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A. (2005). Economía política y desarrollo turístico. In Tourism studies and the sciencies. Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Iamkovaia, M., Arcila Garrido, M., Cardoso Martins, F., Izquierdo González, A., & Vallejo Fernández de la Reguera, I. (2020). Analysis and comparison of tourism competitiveness in Spanish coastal areas. Investigaciones Regionales – Journal of Regional Research, 47(47), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S., Lovelock, B., & Coetzee, W. J. L. (2021). Liberating sustainability indicators: Developing and implementing a community-operated tourism sustainability indicator system in Boga Lake, Bangladesh. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1651–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J. A., Vera-Rebollo, J. F., Perles-Ribes, J., Femenia-Serra, F., & Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A. (2021). Sustainable tourism indicators: What’s new within the smart city/destination approach? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1556–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M., Bakri, N., & Rasoolimanesh, M. (2015). Local community and tourism development: A study of rural mountainous destination. Modern Applied Science, 9(8), 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E., Carneiro, M., & Marques, C. (2020). Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskey, K. L. K., May, T. A., Fan, Y., Bright, D., Stone, G., Matney, G., & Bostic, J. D. (2023). Flip it: An exploratory (versus explanatory) sequential mixed methods design using Delphi and differential item functioning to evaluate item bias. Methods in Psychology, 8, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krce Miočić, B., Razovič, M., & Klarin, T. (2016). Management of sustainable tourism destination through stakeholder cooperation. Journal of Contemporary Management, 21(2), 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Krittayaruangroj, K. (2023). Research on sustainability in community-based tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(11), 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulusjärvi, O. (2017). Sustainable destination development in northern peripheries: A focus on alternative tourism paths. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 12(2–3), 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L., & Sam, T. H. (2024). Community sustainability through sustainable community-based tourism. Revista De Gestão-RGSA, 18(3), e06983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M. (2024). What is qualitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal, 33(2), 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzana, N. L., Gallardo, D., Villaverde, L. D., Herrero, M., Srur, M., & Martínez, M. d. l. P. (2023). Decifrando las similitudes y diferencias entre la gentrificación y turistificación. Cuadernos de Turismo, 53, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinello, S., Butturi, M. A., Gamberini, R., & Martini, U. (2023). Indicators for sustainable touristic destinations: A critical review. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 66(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata Cabrera, F. (2010). La selección sostenible de los materiales de construcción. Tecnología y Desarrollo, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Mendez, A., García-Romero, A., Serrano de la Cruz Santos-Olmo, M., & Ibarra-García, V. (2016). Determinantes sociales de la viabilidad del turismo alternativo en Atlautla, una comunidad rural del centro de México. Investigaciones Geográficas, 90, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G., & Torres-Delgado, A. (2023). Medición del turismo sostenible: Una revisión del estado del arte de los indicadores de turismo sostenible. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniche, A., & Gallego, I. (2022). Benefits of policy actor embeddedness for sustainable tourism indicators design: The case of Andalusia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1756–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Pelaez, M., Tovar-Meléndez, A., & Salazar-Araujo, E. (2023). Revisión documental sobre el turismo sostenible en el marco de los ODS. Journal of Tourism & Development, 40, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano, M., & De Fuentes, A. (2020). Turismo alternativo y localización territorial: El caso de la Península de Yucatán, México. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 18, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. (2008). Sustainable tourism innovation: Challenging basic assumptions. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(1), 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, J. W., Jr., & Hammons, J. O. (1995). Delphi: A versatile methodology for conducting qualitative research. The Review of Higher Education, 18(4), 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myga-Piątek, U. (2011). The concept of sustainable development in tourism. Problemy Ekorozwoju, 6(1), 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nardo, M., Saisana, M., Saltelli, A., & Tarantola, S. (2005). Tools for composite indicators building (EUR 21682 EN). Joint Research Centre, European Commission. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC31473 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Narváez, E. (2014). El turismo alternativo: Una opción para el desarrollo local. RevIISE: Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 6(6), 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Neupane, S. M., & Bhattarai, P. C. (2024). Constructing the scale to measure entrepreneurial traits by using the modified Delphi method. Heliyon, 10(7), e28410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newal, J. (1992). The challenge of competitiveness. Business Quarterly, 56(4), 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, G. M., & Campos, F. J. A. (2025). Un Análisis bibliométrico de la producción científica sobre el turismo sustentable: Tendencias y nuevas perspectivas. El Periplo Sustentable, 48, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C., & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilelienė, L., Grigaliūnaitė, Ž., & Bogoyavlenska, J. (2024). A bibliometric review of innovations in sustainable tourism research: Current trends and future research agenda. Sustainability, 16(16), 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1991). La ventaja competitiva de las naciones. Vergara. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, S., & Ioannides, D. (2017). Contextualizing the complexities of managing alternative tourism at the community-level: A case study of a nordic eco-village. Tourism Management, 60, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A. (2023). Turismo alternativo como impulsor del cosmopolitismo (Opiniones y Ensayos). PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 1(21), 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, G. (2004). Sustainable tourism development: A case study of Bazaruto Island in Inhambane, Mozambique. University of the Western Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J., & Crouch, G. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. University of Calgary. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, B., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2020). Sustainability as a key factor in tourism competitiveness: A global analysis. Sustainability, 12(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saló, A., Teixidor, A., Fluvià, M., & Garriga, A. (2020). The effect of different characteristics on campsite pricing: Seasonality, dimension and location effects in a mature destination. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Amortegui, L., Clemente-Almendros, J. A., Medina, R., & Grueso Gala, M. (2019). Sustainability and competitiveness in the tourism industry and tourist destinations: A bibliometric study. Sustainability, 11(22), 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmoski, G. J., Hartman, F. T., & Krahn, J. (2007). The Delphi method for graduate research. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 6(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J., & Xu, B. (2024). Evaluation model of urban tourism competitiveness in the context of sustainable development. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1396134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D., Svagzdiene, B., Jasinskas, E., & Simanavicius, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustainable Development, 29(1), 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelnikova, M., Ivanova, R., Skrobotova, O., Polyakova, I., & Shelopugina, N. (2023). Development of inclusive tourism as a means of achieving sustainable development. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11(1), 01–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A., & López Palomeque, F. (2018). Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level: A case study of the Catalan coast. Sustainability, 10(2), 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S. H., Lin, Y. C., & Lin, J. H. (2006). Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of the resource, community and tourism. Tourism Management, 27(4), 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, N. (2011). Economics of tourism destinations. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. (2013). Asymmetrical dialectics of sustainable tourism: Toward enlightened mass tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2015). The global competitiveness report 2014–2015. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-competitiveness-report-2014-2015 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (2019). The travel and tourism competitiveness report 2019. Travel and tourism at a tipping point. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga-Collazos, A., Castillo-Palacio, M., & Chim-Miki, A. F. (2012). Análisis de la Producción de Investigación Científica Internacional sobre Turismo en Colombia y Brasil y el Desarrollo Turístico Actual de los Países. Turismo em Análise, 23(2), 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Collazos, A., Padilla-Delgado, L. M., & Tabarquino Muñoz, R. A. (2022). Una propuesta de diseño de política pública para el sector de turismo en el Distrito Especial de Santiago de Cali, Colombia. In M. C. Bahia, M. G. da Costa Tavares, & S. L. Figueiredo (Eds.), Turismo, lazer e patrimônio na Pan-Amazônia (pp. 31–48). Editora NAEA. Available online: https://www.naea.ufpa.br/index.php/livros-publicacoes (accessed on 5 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).