1. Introduction

In an era where environmental concerns are at the forefront of global discussions, the role of technology in promoting sustainable tourism has gained special and significant attention. Understanding the behavior and motivation of young travelers towards eco-friendly travel solutions is critical, as they represent a growing segment of the global tourism market (

Clark & Nyaupane, 2023;

Mansoor et al., 2025). Young individuals are often considered early adopters of technology, making them key players in the shift towards more sustainable travel behaviors using eco-friendly travel apps (

Chin et al., 2024;

Smith & Anderson, 2018). However, despite the growing availability of these applications, little is known about how young individuals perceive the negative environmental impacts of tourism and how this shapes their adoption intention and attitudes towards the value of these apps. This brings the primary question to the agenda: “how does young travelers’ perception of tourism’s environmental consequences affect their attitudes and intentions toward adopting eco-friendly travel applications?” The current study seeks to find the answer to this question.

The tourism industry, besides being beneficial for economies and cultural exchange, has been a major contributor to environmental degradation. Issues such as increased carbon emissions, resource depletion, and ecosystem destruction are well documented (

Gössling & Peeters, 2015). To mitigate these effects, the integration of eco-friendly technologies in travel planning and execution has become a promising approach (

Chakraborty, 2024;

Erdogan et al., 2022;

Gavrilović & Maksimović, 2018;

Jasrotia & Roy, 2024). However, existing literature has predominantly focused on general attitudes towards sustainable tourism or government policies aimed at reducing tourism’s environmental impact (

Boley et al., 2017). Few studies have explored how eco-friendly travel apps can serve as a bridge between awareness of environmental impacts and sustainable travel behavior, particularly among young individuals.

In recent years, researchers have focused more on studying a specific segment of tourist demand: “Youth”. Young travelers are considered “the emerging visitors in the tourism industry” (

Pendergast, 2009). This market segment is significant not only because it is expanding but also because it symbolizes the future of tourism (

Vukic et al., 2014). Generational theory, which considers demographic factors, plays a key role in population analysis by categorizing generations, associating each birth year with its corresponding age group (

Pendergast, 2009). The generation, which now includes the young, is Generation Z (Gen Z), who were born from the mid-1990s to the early 2010s and who are supposed to be between 12 and 27 years old now. Growing up in the 2000s, Generation Z has been profoundly influenced by global challenges like climate change and resource scarcity, fostering their tendency toward sustainability and mindful consumption (

Khalil et al., 2021;

Wu et al., 2024). In connection with this,

Fuentes-Moraleda et al. (

2019) pointed out that younger consumers appear more understanding and are more supportive of sustainable travel initiatives.

From this scientific point of view, this study aims to fulfill the research gap by investigating the interrelation between the perceptions of tourism’s negative environmental impacts and their sustainable travel behaviors as well as analyzing the mediating roles of intention to adopt eco-friendly travel apps and attitudes toward the value of these apps in this relationship. Understanding this dynamic is crucial, as it can reveal how technology can drive environmentally responsible actions among younger travelers, a group that will increasingly shape tourism trends in the coming decades (

Buffa, 2015;

D’Arco et al., 2023;

Zeng et al., 2022).

The studies regarding sustainable behaviors in the tourism context are based on several theories, including the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (

Ajzen, 1985,

1991), cognitive dissonance theory (

Festinger, 1957), and the value-belief-norm theory (

Stern, 2000). This study is grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which is one of the most prominent frameworks for understanding human behavior in relation to intention and action (

Ajzen, 1991). The TPB is especially considered suitable for this study, as it enables a nuanced exploration of both psychological and behavioral dimensions included in eco-friendly travel app adoption, which cannot fully be identified by alternative models like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which primarily focuses on ease of use and perceived usefulness. The TPB incorporates subjective norms (

Ajzen, 1985,

1991), making it especially appropriate in the context of youth behaviors, where peer influence and social expectations are considered to strongly shape both attitudes and adoption intentions.

Previous studies have utilized the TPB to investigate technology adoption in various fields, including tourism and environmental sustainability. For instance,

Lam and Hsu (

2006) applied the TPB to explain tourists’ intention to engage in sustainable travel behaviors, while

M. F. Chen and Tung (

2014) employed it to assess pro-environmental behaviors, showing that attitudes toward sustainability positively affect individuals’ behavioral intentions. This theory is particularly relevant here, as it allows for an examination of how perceptions of the environmental consequences of tourism (attitudes) influence their intention to use eco-friendly travel apps and engage in sustainable travel behaviors. Additionally, TPB’s emphasis on intention aligns well with the study’s focus on adoption intentions and attitudes toward the value of these apps. Hence, in the current study, sustainable travel behavior represents tourists’ reported behaviors rather than their observed behaviors due to financial, ethical, and time challenges (

Juvan & Dolnicar, 2016) and measures to what extent they agree on their willingness to be part of sustainable travel practices.

Depending on the points stated so far, this study has two major objectives: (i) “to examine whether young travelers’ perceptions of tourism’s negative environmental consequences impact their attitudes and intentions towards adopting eco-friendly travel apps, using the Theory of Planned Behavior as a conceptual framework” and (ii) “to determine the mediating role of eco-friendly travel app attitudes and adoption intentions in the relationship between environmental perceptions and self-reported sustainable travel behaviors”. This study is considered significant, as it is expected to have the potential to influence both the design of eco-friendly travel apps and policymaking. By understanding what drives young travelers to adopt these apps and engage in sustainable travel behavior, app developers can create more effective tools that align with user needs and values. Additionally, policymakers can leverage these findings to promote the use of technology in environmental conservation strategies targeted at youth.

Unlike other studies, this research distinguishes itself by examining how eco-friendly travel applications serve as a technological conduit for translating environmental awareness into concrete behavioral intentions among youth travelers. Its novelty lies in examining not only adoption intention but also perceived app value as a key attitudinal variable that remains underexplored in existing literature. Previous studies have not extensively examined the role of eco-friendly travel apps in shaping youth travel decisions, making this study both timely and relevant in the context of sustainable tourism development (

Smith & Anderson, 2018;

Gössling & Peeters, 2015). From this aspect, this study is expected to provide a fresh perspective upon how digital tools can transform environmentally responsible actions. This paper, respectively, reviews the literature to justify the hypotheses of the study, provides methodological information, puts forward the findings through analyzing the data, then discusses the findings, comparing them with previous relevant studies, and concludes the research, providing implications for both future researchers and practitioners in the field of tourism.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

Tourism has been one of the largest and fastest-growing industries, along with the rapid developments and improvements in transportation technologies (

Bratić et al., 2025). While the number of international tourists was twenty-five million in the 1950s, it increased thirtyfold, reaching 760 million fifty years later. According to statistics, tourism accounts for one in four of all new jobs created worldwide. This means that ten percent of jobs are globally linked with the tourism industry (

Soja, 2022). Today, tourism is an important source of export and foreign currency for many countries. Tourism, which holds a significant share in the economy, owes much of its development to natural resources. Tourism and the natural environment mutually influence one another. Many types of tourism (such as coastal tourism, mountain tourism, winter tourism, and thermal tourism) develop based on natural resources (

Pešić et al., 2025). Therefore, the emergence of tourist demand in a region depends on the presence of these elements. When physical environmental conditions become less favorable, the life cycle of a tourist destination nears its end (

Gössling & Hall, 2006). Environmental resources provide one of the critical resources necessary for the creation of a tourism product. Compared to other economic sectors, tourism utilizes environmental resources to a greater extent. The use of these resources significantly supports a country’s economic and social development (

Tuna, 2007). Therefore, it can be said that there is a delicate relationship between tourism and the environment, and tourism activities should be carried out in an environmentally sensitive manner.

Tourism and the environment, as could be cogitated, symbolize a mutual relationship. On one hand, tourism is an activity highly dependent on the environment, while on the other hand, it significantly affects the environment. It is a sector that both extensively utilizes the environment and is obliged to protect it. Tourism activities require natural resources more than social data. The relationship between tourism and the environment is vital, and for tourism to continue to exist, the environment must be sustained (

Demir & Çevirgen, 2006). Although tourism was predominantly seen as an ‘environmentally friendly activity’ and a ‘smokeless industry,’ in later years, concerns began to emerge about possible ecological imbalances that could arise from tourism development. In the 1970s, with the expansion of tourism into new geographic areas and the visible emergence of its negative effects, the environmental impacts of tourism started to be questioned more frequently (

Holden, 2016). As a result, the tourism–environment (natural) relationship, particularly the negative environmental impacts of tourism on sustainable consumer behavior, has been widely studied by tourism academics.

Increasing knowledge and concerns about the negative impacts of tourism on the environment have heightened the need for sustainable tourism development. Sustainable tourism emphasizes the industry’s needs and the sustainable use of resources. It is defined as a tourism model that encompasses the ethical aspects of the sustainability ideology (

Saarinen, 2006). Sustainable tourism is not opposed to growth but argues that there are limits to growth. Therefore, it advocates not only for sustainable production but also for sustainable consumption. In the understanding of sustainable tourism, the environment is prioritized, and behaviors that reduce tourism’s negative environmental impacts are of great importance (

Holden, 2016). This is because the efforts of tourism producers alone will be insufficient to achieve the goals of sustainable tourism. It is crucial that these efforts be supported by sustainable consumption behaviors. At this point, the equation of tourism, consumption, and sustainability becomes an important agenda and research topic.

Individuals participating in tourism activities generate impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, and environmental damage through their travels. In the context of tourism, sustainable consumption is defined as individuals traveling on a more local scale using high-efficiency transportation methods and/or, more importantly, being willing to pay more to reduce the environmental impacts resulting from their travel (

Hall, 2009). In tourism literature, a sustainable consumer is described with the concepts “environmentally conscious consumer”, “green consumer”, “responsible consumer”, and “eco-friendly consumer”, and sustainable consumer behavior emphasizes environmentally friendly travel experiences (

Mehmetoglu, 2009). In the current study, sustainable consumer behavior is represented with “sustainable travel behavior”, which measures the willingness of individuals to mitigate the environmental impact of their travel.

There is a growing number of studies focusing on perceptions over environmental impacts of tourism (

Hedlund, 2011;

Mikayilov et al., 2019;

Sroypetch et al., 2018;

Xu & Hu, 2021). Along with the increasing environmental concerns, assessing perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism and the influence on sustainable attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors has become an important research topic. While extant studies have extensively explored the interrelations between tourism, environmental sustainability, and consumer behavior, the literature reveals theoretical ambiguities and fragmented evidence concerning the mechanisms driving sustainable travel behavior. Earlier research predominantly delineates the environmental impacts of tourism or examines pro-environmental intentions in isolation. However, the existing literature lacks a systematic integration of attitudinal (e.g., value perception), intentional (e.g., adoption intention), and behavioral (e.g., sustainable travel actions) dimensions within a single model grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).

Despite the widespread application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), previous studies possess inconsistencies regarding the mediating influence of technological adoption and environmental attitudes in shaping sustainable behaviors. These theoretical controversies (particularly the inconclusive translation of ecological perceptions into tangible behavioral outcomes) underscore the need for a more comprehensive model that systematically unifies perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral constructs. Additionally, few studies have empirically validated the mediating mechanisms linking environmental attitudes, technological adoption, and sustainable behavior in tourism contexts. As a result, the present study addresses these theoretical and empirical gaps by developing and testing a TPB-based model that explains how travelers’ perceptions of eco-friendly travel apps shape their intentions and actual sustainable behaviors. This synthesis not only reconciles divergent findings across prior research but also provides a more holistic understanding of digital sustainability within contemporary tourism.

According to behavioral science, the perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, norms, behavioral intentions, willingness, etc., can be preconditions of actual behaviors, although they do not necessarily convert into actual behaviors (

Budeanu, 2007). Accordingly, the environmental perception was found to be effective on environmentally friendly purchasing behavior (

Laroche et al., 2001), green hotel choices (

Han et al., 2010), energy-saving and carbon-reduction behavior (

Qiao & Gao, 2017), and attitudes towards eco-labeled products (

Fairweather et al., 2005). Another study (

Mckercher et al., 2010) focused on assessing consumers’ awareness towards the relation between tourism and climate change and its impact on changing their vacation behaviors to reduce environmental impacts. Similarly,

Xu and Hu (

2021) examined the link between perceived environmental impacts of tourism and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) from residents’ perspectives and revealed that the perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism statistically affected ERB. In line with the findings of previous studies and the theory of planned behavior, the following hypothesis is developed:

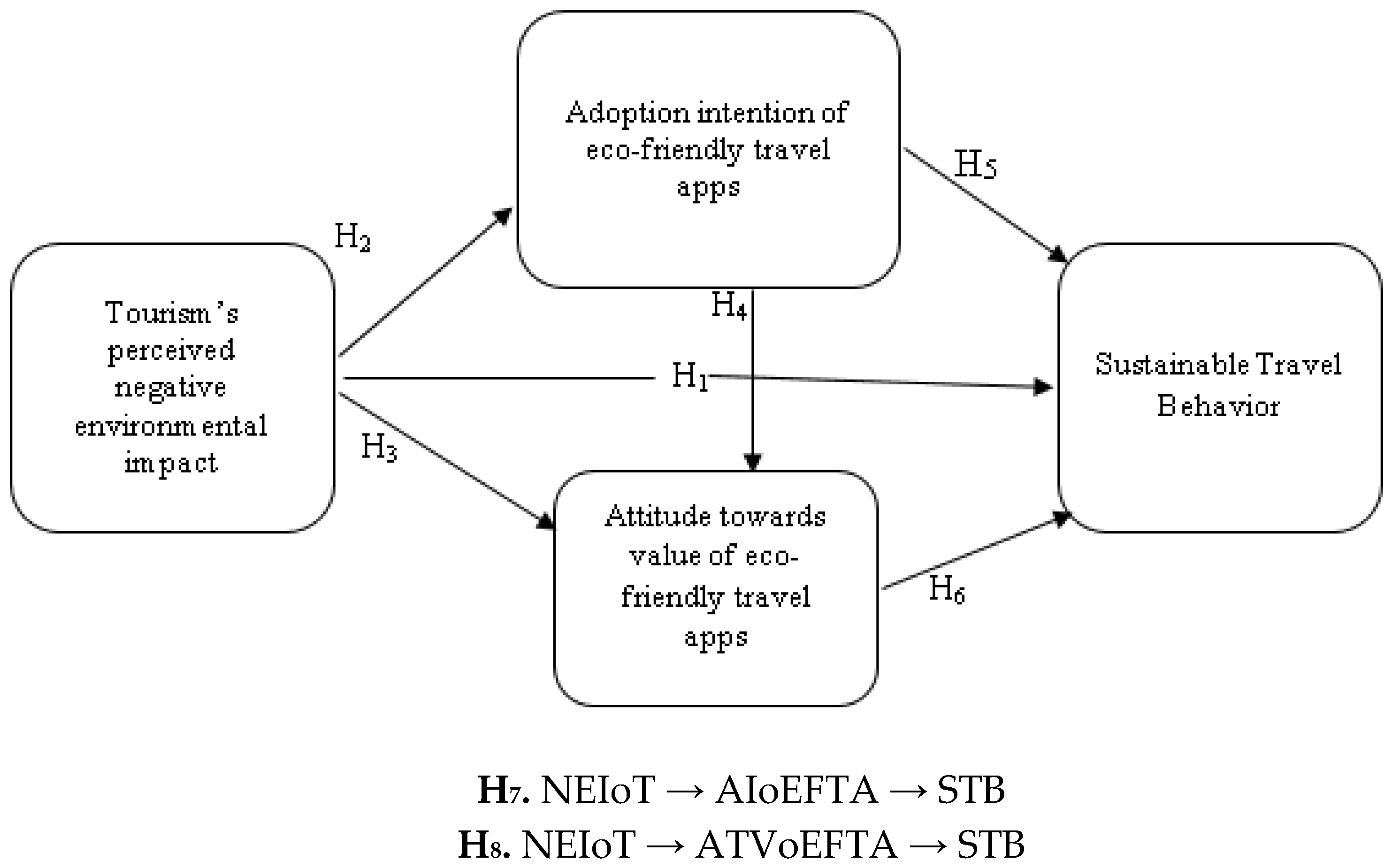

H1. The perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism are significantly linked with sustainable travel behavior.

In the current study, the behavioral intention is represented with “adoption intention of eco-friendly travel apps”, and attitude is represented with “attitude toward value of eco-friendly travel apps”. Both the theory of reasoned action (

Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and the theory of planned behavior (

Ajzen, 1985,

1991) assume that perception plays a significant role in shaping attitudes and behaviors. Behavioral intentions have been found effective on the selection of sustainable travel options (

Mohaidin et al., 2017). On the other hand, attitudes are considered significant determining factors, which influence individuals to behave in a more environmentally friendly way and contribute to sustainable tourism achievement (

Butnaru et al., 2022). Thus, intention and attitude are essential predictors and precursors to behaviors (

Ajzen, 1985,

1991). As a result, investigating the interaction between perceptions over negative environmental impacts of tourism, the intention to adopt eco-friendly travel apps, and attitudes towards the value of these apps seems to be important. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2. The perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism are significantly linked with the adoption intention of eco-friendly travel apps.

H3. The perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism are significantly linked with the attitude towards the value of eco-friendly travel apps.

Furthermore, technological factors provide benefits for tourism consumers to develop sustainable behaviors. There are empirical studies that found a nexus between sustainable tourism behavior/consumption and technology use (

Christodoulides et al., 2012;

Horng et al., 2022;

Parra-López et al., 2011). Innovative environmental technologies are thought to have the potential to transform consumer behaviors to reduce the environmental impact of their travel. Adopting environmental technologies in the hotel industry was found to have a significant influence on pro-environmental behavior (

Adeel et al., 2024). Accepting and adopting environmentally friendly technologies in tourism are seen as a way to protect the environment and involve consumers (travelers, tourists, etc.) in sustainable travel practices (

Gavrilović & Maksimović, 2018). Based on the existing literature and in line with the theory, the following hypotheses are developed:

H4. The adoption intention of eco-friendly travel apps is significantly linked with the attitude towards the value of eco-friendly travel apps.

H5. The adoption intention of eco-friendly travel apps is significantly linked with sustainable travel behavior.

H6. The attitude towards the value of eco-friendly travel apps is significantly linked with sustainable travel behavior.

The mediating roles of adoption intention and attitude toward the value of eco-friendly travel apps in the relationship between tourism’s perceived negative environmental impacts and sustainable travel behavior can be effectively framed within the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (

Ajzen, 1991). According to behavioral sciences, pro-environmental perceptions and beliefs do not necessarily result in behaviors (

Ajzen, 1985,

1991;

Budeanu, 2007;

Juvan & Dolnicar, 2016). Therefore, it is considered significant to analyze the mediating variables to better explain sustainable travel behavior. TPB posits that behavior is primarily influenced by intention, which is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (

Ajzen, 1991;

Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). From this point of view, perceptions of tourism’s environmental impacts may evoke a heightened sense of responsibility mediated by behavioral intention and attitude. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7. The perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism have a significant impact on sustainable travel behavior mediated by the adoption intention of eco-friendly travel apps.

H8. The perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism have a significant impact on sustainable travel behavior mediated by the attitude towards the value of eco-friendly travel apps.

All direct and indirect relationships are illustrated on

Figure 1.

4. Data Analysis and Findings

The data was analyzed using SPSS for version 23.0 and AMOS 24.0 programs. For example, the reliability of the scales was tested through “Reliability Analysis” on SPSS, and the “Confirmatory Factor Analysis” and path analyses were conducted on AMOS. In the first place, the frequency analysis of demographics was performed.

Table 1 reveals that 52.1% of respondents are male, with 42.6% aged between 23 and 25 and 36.7% between 20 and 22. Additionally, more than half of the respondents have a monthly allowance/income under EUR 500. The table also indicated that the great majority of the respondents are always able to access the internet (63.1%) and feel very comfortable using mobile apps for traveling (47.9%). Additionally, almost 80% of respondents come from an urban residence background, and more than half of them (53.3%) travel only once within a year. Only a very small percentage of participants travel more than five times in a year (5.7%).

As illustrated in

Table 2, the Adoption Intention of Eco-friendly Travel Apps (AIoEFTA) exhibits robust factor loadings, with standardized estimates between 0.838 and 0.910. Correspondingly, ATVoEFTA (Attitude Towards the Value of Eco-friendly Travel Apps) exhibits robust standardized estimates ranging from 0.796 to 0.875. Finally, Sustainable Tourism Behavior (STB) exhibits a little lower still acceptable range of standardized values. Two items from the Sustainable Travel Behavior (STB) scale were removed due to standardized factor loadings below the acceptable 0.50 threshold, likely because they reflected high-effort or cost-intensive behaviors less aligned with the travel realities of our Gen Z sample, and their removal improved model fit and preserved construct reliability and validity (

Hair et al., 2010). The standardized estimates demonstrate that the measuring model has robust convergent validity across all constructs.

Table 3 displays the composite reliability (CR), Cronbach alpha reliability (α), average variance extracted (AVE), maximum shared variance (MSV), and maximum H reliability (MaxR(H)) for the principal constructs in this research: Perceived Negative Environmental Effects of Tourism (NEIoT), Intention to Adopt Eco-friendly Travel Apps (AIoEFTA), Attitude Towards the Value of Eco-friendly Travel Apps (ATVoEFTA), and Sustainable Tourism Behavior (STB).

All constructs exhibited robust internal consistency, with CR values between 0.779 and 0.905, surpassing the advised criterion of 0.70 (

Hair et al., 2010). In a similar vein, Cronbach’s alpha values also exceed the threshold value of 0.70. The AVE values, indicating the variance captured by the constructs, satisfied the acceptable threshold of 0.50. The MaxR(H) values reinforce the constructs’ reliability, signifying that the indicators are dependable measurements of their corresponding latent variables. To further ensure the robustness of the measurement model, several complementary statistical tests were conducted. Harman’s single-factor test was used to assess the potential for common method bias. The unrotated factor solution revealed that the first factor accounted for 45.11% of the total variance, which is below the recommended threshold of 50%, indicating that common method bias is not a serious concern (

Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Collinearity diagnostics were examined using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All constructs showed VIF values ranging from 1.00 to 1.83, well below the critical value of 5 (

Hair et al., 2010), confirming the absence of multicollinearity issues among the predictor variables. Furthermore, discriminant validity was further assessed using the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT;

Henseler et al., 2015). The computed HTMT values ranged from 0.40 to 0.85, all below the conservative threshold of 0.90, confirming satisfactory discriminant validity across all constructs. Combined with the Fornell–Larcker criterion and acceptable reliability indices, these results confirm the distinctiveness and adequacy of the measurement model constructs.

The correlation matrix, presented in

Table 3, underscores notable links among the constructs. The square roots of the AVE values, presented on the matrix’s diagonal, exceed the construct intercorrelations, so demonstrating discriminant validity (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Several significant relationships arise from the correlation analysis. NEIoT exhibited a positive correlation with AIoEFTA (r = 0.326,

p < 0.001), ATVoEFTA (r = 0.369,

p < 0.001), and STB (r = 0.413,

p < 0.001). The findings indicate that persons who perceive the negative environmental effects of tourism are more inclined to embrace eco-friendly travel applications, possess favorable opinions towards the utility of these applications, and participate in more sustainable tourist practices. AIoEFTA exhibited a robust correlation with ATVoEFTA (r = 0.719,

p < 0.001) and STB (r = 0.658,

p < 0.001), suggesting that individuals with greater intentions to adopt eco-friendly travel applications are inclined to possess more favorable attitudes regarding the value of these applications and are more predisposed to participate in sustainable tourism practices. ATVoEFTA exhibited a positive correlation with STB (r = 0.657,

p < 0.001), indicating that favorable perceptions of eco-friendly applications are connected with enhanced sustainable tourism behaviors.

Table 4 shows the model fit statistics for the suggested structural equation model. The fit indices indicate an exceptional model fit according to the established standards in the literature (

Hu & Bentler, 1999;

Kline, 2016). The chi-square statistic (CMIN) was 137.344, accompanied by 71 degrees of freedom (DF). The chi-square test is influenced by sample size, although the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) is more frequently employed to evaluate model fit. The CMIN/DF ratio of 1.934 is within the suggested range of 1 to 3, signifying a great fit (

Kline, 2016). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.981 and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.975, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.95, hence suggesting an exceptional fit. The Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR), which quantifies the disparity between observed and predicted correlations, was 0.044, significantly lower than the threshold of 0.08, indicating an exceptional fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.047, below the recommended maximum of 0.06, indicating a close fit of the model to the data. The PClose value, which evaluates the null hypothesis that RMSEA is less than or equal to 0.05, was 0.635, exceeding the threshold of 0.05, so offering additional evidence that the model closely fits the data (

Browne & Cudeck, 1993).

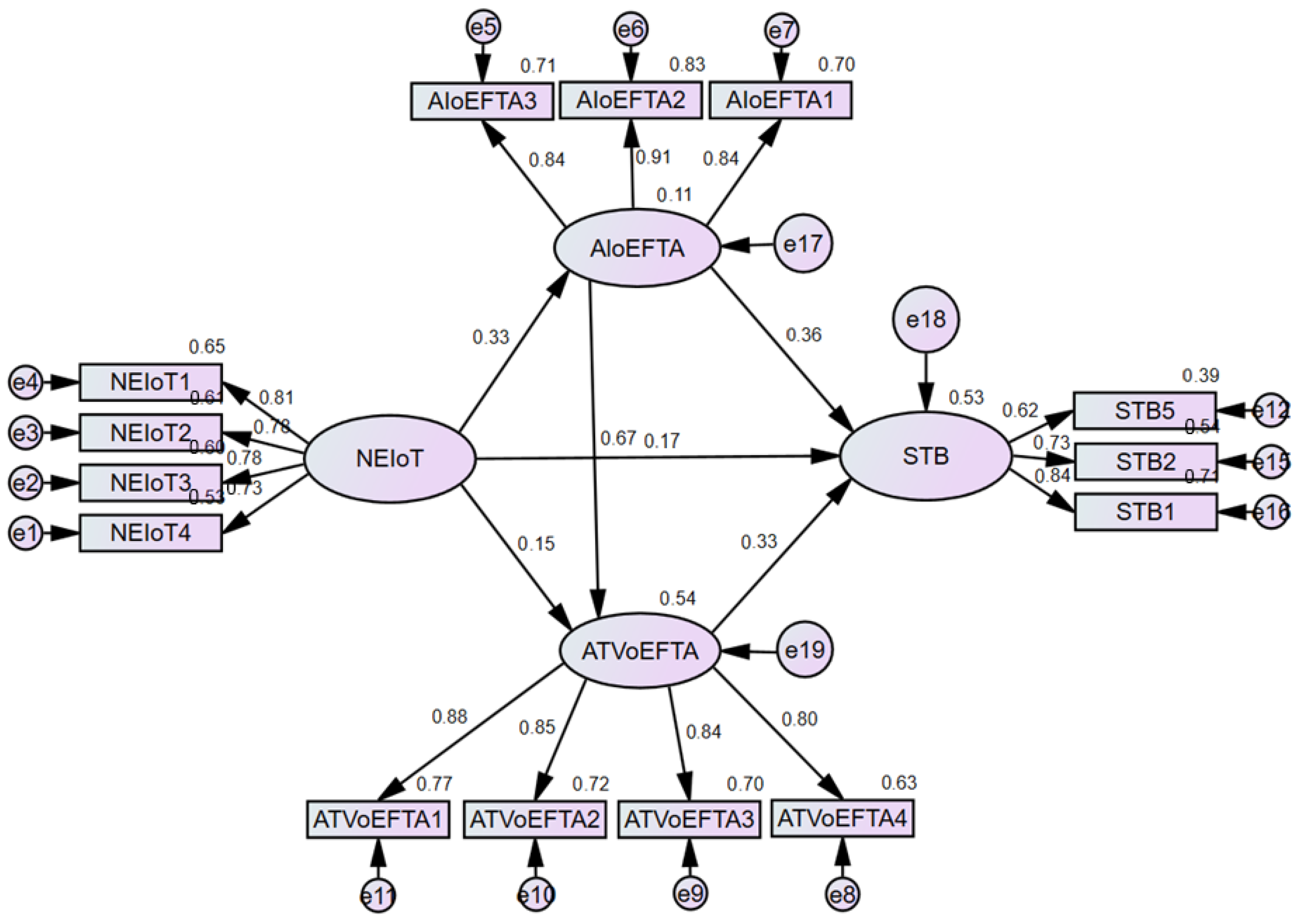

In the final stage, the hypotheses were tested. A statistical approach known as path analysis, which extends multiple regression techniques, was employed to clarify the relationships among the variables (see

Figure 2).

Table 5 illustrates the outcomes of the hypothesis testing, analyzing the direct links among the constructs. All proposed hypotheses were corroborated by statistically significant pathways (

p < 0.01).

Hypothesis 1, which proposed that the Perceived Negative Environmental Impact of Tourism (NEIoT) positively affects Sustainable Tourism Behavior (STB), was corroborated with a beta coefficient of 0.172. H2 identified a significant influence of NEIoT on AIoEFTA (Adoption Intention of Eco-friendly Travel Apps), with a beta coefficient of 0.326, corroborating the hypothesis that persons who recognize more environmental consequences are more inclined to embrace eco-friendly travel applications.

In a similar vein, H3 was validated, indicating that NEIoT exerts a positive influence on ATVoEFTA (Attitude Towards the Value of Eco-friendly Travel Apps) with a beta coefficient of 0.151. H4 exhibited a robust positive relationship between AIoEFTA and ATVoEFTA (β = 0.669), signifying that increased adoption intention results in more favorable perceptions of the value of these applications. Furthermore, AIoEFTA exerted a positive impact on STB (β = 0.363), corroborating the theory that the intention to embrace eco-friendly applications leads to sustainable tourist behavior. Ultimately, ATVoEFTA was determined to have a substantial impact on STB (β = 0.333), indicating that a favorable disposition towards eco-friendly travel applications promotes more sustainable tourist behaviors.

In order to test Hypotheses 7 and 8, Hayes Macro Model 4 analysis was conducted. As illustrated in

Table 6, Perceived Negative Environmental Impact of Tourism (NEIoT) was found to influence Sustainable Travel Behavior (STB) both directly and indirectly through two mediators: Adoption Intention of Eco-friendly Travel Apps (AIoEFTA) and Attitude Towards the Value of Eco-friendly Travel Apps (ATVoEFTA). Specifically, the partial mediation effect through AIoEFTA was 0.0711, and through ATVoEFTA it was 0.0896.

The total indirect effect was 0.1607, suggesting that a significant portion of NEIoT’s impact on STB is mediated via AIoEFTA and ATVoEFTA. Despite these strong mediation effects, NEIoT retained a significant direct effect of 0.1218 on STB, indicating partial rather than full mediation. Overall, the model explained a substantial 40.5% of the variance in STB. As a result, Hypotheses 7 and 8 are also supported.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the interrelations between tourism’s environmental consequences, the adoption of eco-friendly mobile apps, the attitude towards the value of eco-friendly travel apps, and sustainable travel behavior, with a particular focus on young travelers. Tourism, as a sector, has long contributed to both positive cultural exchange and significant environmental challenges, including carbon emissions, resource depletion, and habitat destruction. As awareness of these consequences has grown, so too has the demand for technological solutions to mitigate tourism’s environmental impact. Eco-friendly travel apps represent one such solution, offering users ways to make sustainable choices more accessible and actionable. The current study shows that youth perceptions of tourism’s environmental impact positively influence their intention to adopt these apps, with strong attitudes toward the value of these apps reinforcing the likelihood of sustainable travel behavior. These findings underscore a valuable contribution to the literature on sustainable tourism and environmental technology adoption, highlighting the role of eco-friendly mobile applications as facilitators of positive environmental change. By linking environmental perceptions, adoption intentions, and attitudes with sustainable behavior, this study enriches the understanding of the psychological and behavioral mechanisms underlying sustainable tourism practices, particularly within the increasingly influential youth demographic. Therefore, it can be stated that this study uniquely contributes by positioning eco-friendly travel apps as significant mediators that translate environmental perception into action, addressing a gap in the current literature, which often overlooks the role of digital platforms in achieving sustainability. As a result, it is possible to make some theoretical and practical recommendations.

6.1. Implications

From a theoretical perspective, the finding relying on the significant but weak effect of perceived negative environmental impacts of tourism on sustainable travel behavior reinforces the need to expand the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explicitly incorporate technology adoption as a factor influencing sustainable travel behaviors. Given the positive influence of eco-friendly travel apps observed in this study, the TPB framework may benefit from an additional variable that represents technological adoption as a driver of pro-environmental behavior. This potential extension could provide a more comprehensive theoretical understanding of sustainable travel choices, as supported by findings from

Mohaidin et al. (

2017) on the role of technology in encouraging eco-friendly actions. Furthermore, future research should explore whether these findings are consistent across different cultural contexts, as cultural factors may influence attitudes and intentions related to eco-friendly technology adoption. Research by

M. F. Chen and Tung (

2014) suggests that cultural variations can play a substantial role in shaping consumer behavior, indicating that cross-cultural studies could broaden the theoretical application of these findings.

Furthermore, it is suggested that longitudinal studies be conducted to analyze the lasting impact of eco-friendly app adoption on sustainable travel behavior. The findings of this study provide a valuable snapshot, yet longer-term research could reveal whether initial adoption leads to sustained eco-friendly behavior over time, further enriching the literature on the role of environmental technology in tourism. By investigating these areas, future studies can advance theoretical knowledge and provide deeper insights into how technological and environmental factors intersect to influence sustainable travel practices.

In light of the findings, it is possible to make several practical recommendations to encourage sustainable travel behaviors among young travelers. Initially, governments, tourism boards, and educational institutions should invest in awareness campaigns targeting youth, highlighting the environmental impacts of tourism and the role of eco-friendly travel apps as solutions to mitigate these impacts. Studies by

Qiao and Gao (

2017) and

Xu and Hu (

2021) emphasize that awareness is an essential driver of eco-friendly behavior, particularly when combined with accessible solutions. By promoting the convenience and positive environmental impact of eco-friendly travel apps, such campaigns could significantly increase their adoption among young users. Additionally, app developers are encouraged to design platforms that directly incentivize sustainable choices. Features like loyalty points, discounts, or partnerships with environmentally conscious brands could reinforce sustainable behavior by rewarding eco-friendly choices. This approach aligns with the findings of

Christodoulides et al. (

2012), who note that rewards are effective motivators for shaping consumer behavior.

Collaboration between eco-friendly app developers and tourism service providers, such as green-certified hotels and electric vehicle rental companies, is also recommended. Through these partnerships, apps could offer users real-time sustainable options, expanding the range of eco-friendly choices available to them during their travel planning. This recommendation echoes the work of

Gavrilović and Maksimović (

2018), who underscore that the easier it is to access eco-friendly options, the more likely consumers are to choose them. Educational institutions can also play a vital role by integrating responsible tourism and sustainability into their curricula, especially within tourism and hospitality programs.

Gössling and Peeters (

2015) argue that structured educational interventions can foster long-term environmental responsibility, and this approach would empower the next generation of travelers to prioritize sustainable choices.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study presents valuable insights; however, there are some limitations that future research should address to enhance the generalizability and depth of findings. First, the study is geographically limited, with data collected from university students in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which may affect the cultural generalizability of the findings. Second, the cross-sectional design provides a snapshot of attitudes, intentions, and behaviors at a single point in time, which does not capture the evolution of sustainable travel behavior over an extended period. Another limitation of this study lies in the reliance on self-reported app usage, which may be subject to recall bias or social desirability effects. Although participants were asked to name specific eco-friendly travel apps and were provided with concrete examples to standardize understanding, we acknowledge the possibility of misinterpretation or overreporting of sustainable behavior.

This study also lacks a key driver of Generation Z’s behavior: social influence, such as peer recommendations, online reviews, or influencer endorsements, which are particularly relevant for understanding the behavior of Generation Z. Gen Z is considered highly responsive to peer opinions, influencer endorsements, and social media trends, all of which can significantly shape both their attitudes toward new technologies and their willingness to adopt so-called “green” apps. Finally, although this study focused on youth perceptions, intentions, and behaviors, it did not account for detailed demographic variations, such as socioeconomic background or prior travel experience, which could influence sustainable travel choices. Addressing these limitations in future studies would strengthen the reliability and scope of research in this area.

In light of these limitations, several recommendations are made for future researchers. To broaden the generalizability of results, future studies should consider cross-cultural comparisons, exploring whether the relationships identified in this study hold across different regions and cultural backgrounds. Studies by

M. F. Chen and Tung (

2014) suggest that cultural factors can significantly influence attitudes and behavioral intentions, indicating that examining diverse cultural contexts could provide a richer understanding of eco-friendly app adoption and sustainable tourism behavior. Longitudinal research is also recommended to investigate whether adoption of eco-friendly travel apps leads to sustained changes in behavior over time, as this approach could capture the long-term impact of attitudes and intentions on travel behavior, addressing the limitation of the present study’s cross-sectional design. Furthermore, future research could enhance the rigor of this inclusion criterion by verifying actual app usage through digital logs, screen recordings, or passive data collection methods. Additionally, future studies may consider developing or adopting a validated scale to assess the perceived eco-friendliness of travel apps to further mitigate subjectivity.

Additionally, future researchers are suggested to incorporate constructs related to social influence into the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) framework, adding survey items on peer usage or perceived social approval, or conducting follow-up qualitative interviews to explore how digital communities reinforce sustainable app adoption. Examining specific demographic subgroups within the youth population, such as differences based on socioeconomic status, education level, and travel experience, could yield more nuanced insights. Research by

Budeanu (

2007) has shown that demographic variables play a crucial role in shaping environmental perceptions and sustainable behaviors, so targeting these factors could provide more precise data on what motivates different segments of youth to adopt sustainable travel practices. Furthermore, future researchers should consider the influence of app design and usability factors on adoption and behavior, as the user experience of eco-friendly apps may significantly impact their effectiveness. Findings from

Adeel et al. (

2024) emphasize the importance of user-centered design in green technology adoption, suggesting that incorporating features like carbon footprint calculators or eco-friendly travel recommendations could enhance sustainable choices.

Finally, examining the role of policy interventions on eco-friendly app adoption and sustainable travel behavior would provide useful insights into how external incentives or requirements could further encourage eco-friendly tourism. Policies such as subsidies for sustainable travel options, certifications for eco-friendly travel services, or mandates for green practices within the tourism sector could support the adoption of eco-friendly apps, as suggested by

Han et al. (

2010). Exploring these policy impacts would contribute valuable information on the potential for collaborative efforts between governments, industry stakeholders, and app developers to advance sustainable tourism.