Abstract

The main objective of this paper is to investigate how the interest in the value of performing arts and the awareness of the value of performing arts among local youth in Dhofar can influence their inclinations towards performing arts. Moreover, we have incorporated the perceived brand equity of the Dhofar region as a moderator in the proposed model. A structured questionnaire was administered to a sample of young residents in the Dhofar region (N = 415). The measurement instrument was developed based on the established literature concerning youth behavior, territorial branding, and the perceived value of performing arts. All items were measured using five-point Likert scales. The main theoretical constructs were operationalized as arithmetic means (composite scores) of their corresponding items: VPA (Value of Performing Arts, 9 items), APA (Awareness of Performing Arts, 10 items), YI (Youth Inclination, 11 items), and DBE (destination brand equity). Data analysis proceeded in several stages using Stata 17. The paper concludes that there is a positive and statistically significant effect of VPA on YI. Furthermore, our results confirmed that there is a positive relationship between the awareness of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts. Moreover, the results indicated that destination brand equity is not a significant moderator in the relationship, which means that there is no moderating effect of DBE that was confirmed on either path. This study underscores the need of preserving intangible cultural heritage by stimulating interests and developing suitable practices to make the Dhofarian youth inclined towards performing traditional arts. The findings of this study offer some policy implications to policymakers to sustain creating an interest in valuing traditional arts performance and increasing the awareness of these types of events, which are influential factors in shaping youth inclination towards performing traditional arts. The study suggests that generating awareness is vital in creating the intention among local youth to perform traditional arts. These findings suggest that policymakers provide support for traditional art performances by devising an institutional policy that provides structural support to increase interest and awareness. The paper is an original contribution as it has provided insights into how the extent of the interest in the value of performing arts and the awareness of the value of performing arts could influence the inclination of local youth to perform art activities in the Dhofar region. Secondly, this study explores whether perceived brand equity moderates this relationship.

1. Introduction

Oman is a country that has a distinctive culture in the Middle East. The country has different governorates, each of which has its own unique culture (i.e., sub-culture) that differentiates it from the others. One of them is the Dhofar governorate with a unique legacy. Dhofar is rich in intangible cultural heritage and attracts tourism because of this reason. For example, Omanis have their own related frankincense traditions, oral poetry of different forms, unique Arabic dialectic, i.e., “Al Jabalia Language”, and traditional arts performances that include the use of traditional music and dance. The UNESCO acknowledges various forms of intangible heritage culture, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, and ritual and cultural practices. Omanis have preserved and safeguarded their culture.

Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage reflects the unique identity of a nation and is a guarantee towards cultural continuity, belonging, and pride. These forms of intangible cultural heritage are expected to contribute towards building social cohesion in the region. Such intangible cultural heritage that manifests in different forms is expected to contribute positively towards creating economic opportunities and promoting the country as a tourist brand (Swain et al., 2023), which is the key challenge for the youth of the country.

The Dhofar governorate that preserves their intangible cultural heritage because of youth awareness and inclination is likely to support the growth of the tourism sector and may contribute further to driving a higher number of tourists and creating jobs in the tourism sector (Gulvady et al., 2023). In short, youth inclination and awareness towards performing art protects it from vanishing and promotes cultural tourism. Therefore, it is expected that youth inclination towards performing arts should be promoted through awareness to promote cultural tourism and develop the region as a brand for performing arts.

In this study, the researchers particularly focus on one aspect of the intangible cultural heritage that has not received substantial investigation in the literature, which is the lack of youth inclination towards performing arts. The performing arts have the ability of stimulating cultural renaissance and sustainability; however, the interests of youth are the same. Performing arts can add new perspectives into existing practices and stimulate understanding for traditional knowledge, abilities, skills, and designs (Borgonovi, 2004). If executed appropriately through value creation, performing arts can offer an exciting mechanism to generate local pride which will develop the youth’s inclination towards the same.

Performing arts creates opportunities for developing youth inclination towards the same because of developing intercultural dialog to nurture emotions for acceptance of unlike cultures and stimulate common understanding between different societies. Performing arts can demolish boundaries between the immaterial and the material, leveraging the innovative potential of those engaged to start to outline a new intervention space (Nelson et al., 2016). Several studies have empirically proved that organized performing activities by young people can stipulate a powerful context in which youngsters can grow competencies necessary for healthy adulthood (Delgado & Humm-Delgado, 2017; Block et al., 2022).

Structured performing arts activities can offer youngsters an emotionally diverse (Davico et al., 2022) and socially intensive experience (Daykin et al., 2008) as well as providing the physical and artistic challenges that promote positive development (Parker et al., 2018). However, the current youth is highly tilted towards financial and economic gains (Asad et al., 2025). Hence, destination branding may significantly boost cultural tourism and may enhance the inclination of youth towards performing arts.

In contrast, globally, the youth pay less interest and hardly be inclined to engage in performing traditional arts (Abbing, 2019) and Omani youth are not an exception to this. Studies globally indicated a decline in the youth participation in performing arts (Masunah, 2017). In the available literature, external factors such as globalization, urbanization, and the emergence of modern technologies (Ta’Amnha et al., 2024) were deemed to be influential in decreasing the youth’s inclination towards performing arts (Fitryansyah, 2024). Contrarily, our study adds to the existing literature by investigating how youth inclination towards performing arts can be developed through value, awareness, and destination branding as these attributes have hardly gained attention by scholars.

Therefore, the specific objectives of the researchers are identified below:

- To investigate the impact of value of performing arts over youth inclination towards performing arts.

- To investigate the impact of awareness of performing arts over youth inclination towards performing arts.

- To identify the moderating role of destination brand equity over the relationship between the value of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts.

- To identify the moderating role of destination brand equity over the relationship between the awareness of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts.

Thus, we intend to offer novel insights and provide practical recommendations for various stakeholders to preserve an important aspect of intangible heritage culture, “performing arts.” We have also incorporated the perceived brand equity of the region as a moderator in the proposed model. Perceived brand destination is proposed as a contextual variable that may weaken or strengthen the relationship between youths’ inclination towards performing arts and their actual interest and awareness about the value of performing arts. Investigating this dynamic is important not only for heritage preservation but also for destination development strategies that aim to position cultural identity as a key asset.

2. Literature Review

Cultural heritage is declining all over the world because the upcoming generation is hardly interested in culture and history because of market situations and competition. Considering the same issue, the purpose of the study is to analyze the identified factors that may promote youth inclination towards performing arts; moreover, the moderating role of destination branding has been added to the model to understand the role of economic aspects in promoting youth inclination towards performing arts. Considering the developed framework, the following theories support the argument which underpins the theories for the proposed framework: Self-Determination Theory and culture reproduction theory.

2.1. Value of Performing Arts

From an economics perspective, performing arts can offer interesting income and employment opportunities and harness local natural and cultural resources (Baldin et al., 2018); open new venues for entrepreneurial activities because of low level of ‘entry hurdles’ (Sinapi & Juno-Delgado, 2015); and add to the innovation (Asad et al., 2024) and diversification of the tourist experience and revolutionize current models of tourism development (C. L. Chen, 2021). Prior research showed how creative economies, which encompass performing arts, can contribute towards economic prosperity and knowledge dissemination.

The creative industries contribute immensely to creating, converting, and distributing knowledge and have grown at a faster rate than the world’s economy in late years, with trade in creative services and goods developing by an average proportion of 8.8%. They have the capacity to foster economic growth and job creation, reinforce entrepreneurship and innovation, support rural and urban regeneration, and encourage exports. Through creative performance, tourists are not only equipped with a new ability, skill, or knowledge, but with a significant message to take to their countries and share with their peers, therefore expanding the experience’s impact through articulative memorabilia (Noonan, 2021).

This empowers those performing artists with exceptional skills in a new position of privilege as the transmitter of knowledge and the teachers of skills. Other scholars studied community-based co-creative tourism indicators as being important when looking at the financial advantages of co-creative tourism to communities. These include the following: a surge in local employment, an increase in annual income, more job opportunities, more product innovations, and broader market opportunities for skillful handcraft artisans (Cetină & Bădin, 2019).

The financial and societal value potential embedded in performing arts can be relevant to four Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are economic prosperity, which is SDG 8, diminishing inequalities, which is SDG 10, sustainable urban cities and communities which is SDG 11, and responsible production and consumption which is SDG 12 (UNESCO, 2020). The details of the linkage are mentioned in Appendix B. The UN promotes inspiring marginalized groups as one effective tool in the fight for sustainable development and eventually demolishing poverty. The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs stresses the role of youngsters in accomplishing sustainable social development as a partner in achieving the SDGs and one of the targeted ‘underserved’ societies the SDGs were written specifically for.

Youngsters are a vital and yet under-recognized stakeholder category playing a vital role in future cultural preservation programs. As tomorrow’s future leaders, stressing the local youth’s role in reviving performing arts and creative tourism practices is an expected partnership (Power, 2021). The importance of creative and cultural legacy in the sustainable development of youngsters is significantly strong as the performing arts sector employs more young people (15–29-year-olds) than any other sector in the economy, contributing 29.5 million jobs on the world’s stage (UNESCO, 2020).

More importantly, the positive economic repercussions of creative performing arts will be felt by all society categories, old and young in parallel. Whilst outmigration of youngster has been recognized as a building block in the way towards more favorable development dynamics in many communities, the utilization of performing arts endeavors to encourage the youth to expand their capabilities, social skills, and job opportunities, which could be one venue to avoid the negative impacts of rural migration (Zifkos et al., 2021).

Thus, while the value of performing arts and youth involvement appears marginal within tourism, these elements play a crucial role in shaping a destination’s brand image. Performing arts not only reflect the cultural identity of a place but also serve as a dynamic medium to engage youth and visitors. In the case of Al Hafsia, such initiatives have demonstrated potential in sustaining traditional practices, fostering community participation, and enhancing heritage conservation. Given what was mentioned above economically and socially, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

The value of performing art has a significant impact over youth inclination towards performing art.

2.2. Awareness of Performing Arts Among Youth

The educational approach of involving youth in educational experiences through dynamic participation has been popular on the pedagogical scene since John Dewey’s 1916 scholarly work, Democracy and Education (Dewey, 2024). Since then, many educational philosophers throughout the past years have added their insights regarding the practicality of Dewey’s argument and on how this involvement can be achieved, both inside and outside the traditional classroom setting. Past research has assumed that students do not digest course learning outcomes by merely sitting in class listening to teachers, memorizing by heart predesigned modules, and studying forecasted questions and answers. They must discuss and live through what they are learning, reflect upon it, link it to their own previous experiences, and implement it to their day-to-day lives (Sanders, 2006).

The involvement of youngsters can lead to an enriching psychological and physical exchange, pushing youth to spend these energies in the academic sphere, hence becoming more involved and therefore pleased by their academic experiences. There are currently louder voices that appreciate the value of non-formal education and its power in involving youngsters in active participation through community engagement. Possible positive consequences can include more equal chances for youngsters, encouraging active citizenship and supporting social and economic development.

Non-formal education is perceived as a necessary tool for active participation, since it was formerly developed for rural societies suffering from shortfalls in traditional educational models. Non-formal education can be “based on the active participation of individuals in the life of their surrounding community with which they communicate directly and where they acquire appropriate habits of doing, thinking and feeling”. In this sense, non-performing arts can be seen as potential non-formal learning activities, outside the classroom, and through which local youth can become more aware of its value and hence actively participate for the betterment of their societies.

In this vein, students can gain practical skills which may not always be taught in the formal classroom setting as well as better engagement with their culture, hence advancing societal sustainability (Han & Kim, 2021). Those newly gained skills may include creative capabilities, language, teamwork skills, notions of past legacy and history, empathy, and other fundamental social skills. Also, Hasan et al. (2023) have examined the level of youth awareness related to cultural and heritage in the Kelantan state in Malaysia. The result indicates eight elements that contribute to heritage in Kelantan, and more than half of the respondents are fully aware of the heritage. Hence, we hypothesize that non-formal education can heighten levels of awareness about the sustainable development implications of performing arts which, in return, can encourage higher levels of youth participation:

H2.

Awareness of performing art has a significant impact over youth inclination towards performing art.

2.3. Destination Brand Equity and Its Relationship with Value and Awareness of Performing Arts

Brand equity tackles the value of services, products, and corporate brands, and has lately been extended to measure the brands of nations and cities (Y. C. Chen et al., 2018). Therefore, some scholarly works have been conducted to better recognize the importance of brand equity in the perception of tourist destination attractiveness. Ekinci and Hosany (2006) identified whether tourists ascribed personality traits to tourism destinations. The findings of the study indicate that perception of destination personality is 3-dimensional: sincerity, excitement, and conviviality. The study also found that destination personality has a positive impact on perceived destination image and intention to recommend. In particular, the conviviality dimension moderated the impact of cognitive image on tourists’ intention to recommend.

Destination brand equity can be defined as the merging of fundamental factors that can be described as the total utility that tourists benefit from in a certain destination when compared to competing destinations. This means that a visitor’s intensity level of interest in tourism has a direct impact on their recognition and perceptions of the destination’s brand equity (Arvanitis, 2020). In the same vein, Rosa et al. (2021) determined the influence of practice-based active learning on students’ interest and response in learning about local culture in drama classes. The study showed a statistically significant increase in students’ interest and response to learning local culture through collaborative learning methods and role-play in drama classroom learning.

In theorizing customer-oriented destination brand equity, there are other important concepts to consider: expected quality, brand awareness, brand reputation, and brand switching rate. Brand awareness is the ability of a potential visitor to recall or recognize mentally that a particular destination is a member of a particular destinations category, for example: product positioning (Lim & Bendle, 2012). In other words, destination brand equity is a brand awareness concept that can potentially be the competence of the tourist in identifying some attractions as an integral part of a touristic place, like performing arts.

Destination brand awareness is recognized as a necessary step toward a tourist’s commitment to a city or country to visit, a fact that clarifies the constant relation of it to tourists’ loyalty towards certain destinations (Zhang et al., 2021). Speaking of tourism, repetitive tourists and a consistent intention to recommend or return to a geographical place are popular measurements of tourist loyalty. Such intentions most probably develop from a mix of perceptions, actual experience, and services received (Luo et al., 2023). In terms of years of publication, publication outlets, authorship, countries, methods, and theories adopted Swain et al. (2023) investigate the development of place branding research over time. They further integrate the antecedents, mediators, and consequences reported in the place’s branding literature. The findings of the study identify under-researched areas in place branding and provide directions to advance this research in terms of theory development, context, characteristics, and methodology.

In this paper, we study the effect of awareness and the value of performing arts on youth inclination to participate in performing arts mediated by the destination’s brand equity in tourism. Hence, it is vital to underline destination brand equity and image within the performing arts context. Swain et al. (2023) identified the impact of destination brand equity and the possible accompanied positive tourist experiences. This is primarily linked with the understanding of how tourists and the outer public process images and perceptions about a specific city as a travel destination (Mukoyani, 2022).

The author (Pike, 2005) explored the enhancement of the understanding of the complex challenges inherent in the development of tourism destination brand slogans. The results of the study showed that there has been relatively little discussion on the complexity involved in capturing the essence of a multi-attributed destination with a succinct and focused brand position, in a way that is both meaningful to the multiplicity of the target audiences of interest to stakeholders and effectively differentiates the destination from competitors. As a next point of discussion, it is vital to differentiate residents from potential and previous tourists, to enable tourism experts to harness the spirit of the city for the purpose of tourist attraction. This fact will potentially rationalize that, in addition to its direct impact, former information about a destination impacts the total perception because of the resulting affection towards the target destination.

Furthermore, the spread of positive word-of-mouth reviews on performing arts can significantly draw new tourists, which can be traced back to an overall positive evaluation of a destination and mirrors high levels of attitudinal loyalty (Mazlan, et al., 2025). Also, authors (Breed et al., 2024) have examined the influence of educational attainment, parental influence, and religious affiliation on youth participation in cultural festivals in Calabar. The results confirmed that educational attainment, parental influence, and religious affiliation had significant influence on youth participation in cultural festivals in Calabar.

Organizing events, like performing arts, are an important element within the strategic plans of the destination branding of a geographical region. Events and cultural performing arts are progressively used to improve cities’ image and improve sustainable tourism development. Cudny (2021) claimed that various geographical destinations on the planet have crafted events portfolios as a strategic tool to attract tourists and to develop their own destination brand.

Annually, an abundant number of performing arts events of various types push travelers to visit the cities that host them. Performing arts have evolved as a means of enhancing the image of destinations, adding life to city streets and offering citizens and tourists revived pride in the city (Cudny, 2019). Performing arts activities can be categorized as mega events if they satisfy the following stretching criteria: have an enormous number of tickets sold; a wide media coverage, especially on TV; a minimum of one million tourists; involve a large “public investment”; are “expensive to stage”; and have long-term permanent urban effect (Richards & de Senna Fernandes, 2023).

Since performing arts events are integral factors to attract tourists, they should be embedded into a destination’s branding strategy. As a practical consequence, this necessitates the accurate evaluation of the contribution of a performing arts event not only in terms of the direct economic contribution that it generates but in terms of its coherence with the destination’s brand values (Sharma & Hassan, 2018). This means including performing arts as an attraction of a destination in the consistent coherent integrated marketing campaign messages of cities and as a part of the overall branding strategy (Ziakas et al., 2024).

Given that a tourism destination is affected by a group of varied actions and experiences marketed under one brand roof, there is a challenge for performing arts planners and managers to fabricate these events constantly and coherently into the interrelationships among the remaining elements of the marketing mixed items and, hence, improve the destination’s brand equity. Luckily, most governmental authorities are persuaded that performing arts have the capacity to improve a geographical destination’s image and brand equity, leading to place distinctiveness and the attraction of travelers and guests (Gelder & Robinson, 2011). Given this conclusion, it is also vital to concentrate on what a performing arts show can do for a destination, and not merely what a destination can do for a performing arts show, since the place of a show might impact its content, objectives, and success.

Indeed, performing arts can be a strong driving force towards a more effective urban economy (Morrison, 2020). This is because they function at the intersection of culture, arts, media, recreation, and tourism. Being effective elements in the marketing and development plans of many cities, performing arts can stimulate a positive image as a geographical destination. This is particularly true if the performing arts at hand have a long historical heritage and/or have been reinvented and rediscovered. According to some researchers, performing arts have a long, deep-rooted correlation with urban cities and have become a vehicle for communicating the close relationship between a location and its identity (Hanna et al., 2021). Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H3.

Destination brand equity significantly moderates the relationship between value of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts.

H4.

Destination brand equity significantly moderates the relationship between the awareness of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts.

2.4. Framework Development

Performing arts serve not only as creative outlets but also as tools for emotional expression, social engagement, and identity formation among youth. However, in an era where digital entertainment and academic pressures dominate the lives of young people, the significance of performing arts is often undervalued, which calls for this research. Theories like Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Cultural Reproduction Theory (CRT) offer valuable frameworks for understanding the motivations behind youth inclination towards performing arts.

Self-Determination Theory, developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, posits that human motivation is driven by the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When these needs are satisfied, individuals are more likely to pursue activities with intrinsic motivation engaging in them for inherent satisfaction rather than external rewards. Performing arts inherently allow for personal expression and creative decision-making, thus supporting a young person’s sense of autonomy.

Participation in the performing arts develops skills and mastery over time (Guo & Liem, 2025). Performing arts-based activities are typically collaborative, involving group rehearsals, performances, and mutual feedback. From the SDT perspective, fostering environments that support these three needs can increase youth inclination towards performing arts. Additionally, Cultural Reproduction Theory, developed by Pierre Bourdieu, argues that education systems and cultural institutions often perpetuate existing social hierarchies by privileging the cultural capital of dominant classes.

Youth from middle- and upper-class families are more likely to be exposed to classical music, theater, and dance early in life. While CRT often highlights how inequality is reproduced, it also opens possibilities for transformative practices. When performing arts programs actively reflect and respect the backgrounds of diverse youth populations, they become vehicles of inclusion rather than exclusion (Howard, 2022). Increasing awareness and visibility of culturally diverse forms of performance helps legitimize them within educational and social spaces, encouraging broader participation.

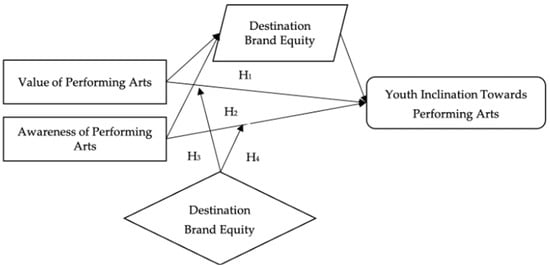

Moreover, considering the declining inclination of youth towards performing arts, because their focus is towards earning money, destination brand equity has been introduced in the model as a moderator (Sulaiman, 2025). This is because destination brand equity promotes tourism business and provides entrepreneurial activities for the youth related to performing arts. Thus, by using CRT as a lens, policymakers and educators can critically examine who has access to performing arts, whose stories are told, and how value is assigned to different art forms. Based on the above discussion and also the call for the integration of Self-Determination Theory and Cultural Reproduction Theory, the following framework has been developed by integrating the two theories, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Source: Authors’ own editing.

Together, SDT and CRT provide a comprehensive understanding of youth engagement in the performing arts. While SDT focuses on the internal psychological drivers of inclination, CRT sheds light on the external structural and cultural forces that enable or inhibit access. The intersection of Self-Determination Theory and Cultural Reproduction Theory offers a powerful framework for understanding and enhancing youth engagement in performing arts. Increasing awareness of performing arts and creating inclusive, motivational environments not only support individual growth but also contribute to a more just and culturally rich society. At the same time, if destination brand equity is promoted, it will further enhance youth inclination towards performing arts.

3. Methods

Data were collected between June and December 2024 using an online questionnaire administered through Google Forms. The survey link was disseminated via university student networks, youth clubs, and social media platforms (e.g., WhatsApp, Instagram, and X) targeting young individuals residing in the region. Prior to the main data collection, the questionnaire was pre-tested with 20 participants to ensure clarity, cultural appropriateness, and technical functionality. Minor modifications were made based on their feedback.

The target population consisted of youths aged 18 to 30 years living in the Dhofar region of Oman. A convenience sampling technique was employed due to the absence of a comprehensive youth sampling framework and the practical constraints of reaching dispersed respondents. This method allowed for the inclusion of participants who were accessible and willing to take part in the study. While convenience sampling facilitates data collection from a broad audience, it also limits the generalizability of the findings to the wider youth population. To ensure data validity, participants were required to indicate their age and place of residence within Dhofar at the beginning of the survey. Responses that did not meet this inclusion criteria were excluded from the analysis. A total of 500 questionnaires were returned, out of which 415 were deemed valid for further analysis after screening for incomplete responses and non-eligible participants. Ethical considerations were strictly observed. The cover page of the questionnaire described the purpose of the study, emphasized voluntary participation and anonymity, and included an informed consent statement. Respondents were able to withdraw at any point without consequence.

The measurement instrument was developed based on the established literature concerning youth behavior, territorial branding, and the perceived value of performing arts. All items were measured using five-point Likert scales. The main theoretical constructs were operationalized as arithmetic means (composite scores) of their corresponding items: VPA (Value of Performing Arts, 9 items), APA (Awareness of Performing Arts, 10 items), YI (Youth Inclination, 11 items), and DBE (destination brand equity). Data analysis proceeded in several stages using Stata 17:

- Internal consistency for the final scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

- Preliminary data screening involved evaluating the normality assumption of the composite scores using Skewness and Kurtosis tests (sktest).

- Prior to index construction, two DBE items (DB_1 “Dhofar is very famous” and DB_5 “Dhofar is better than other similar destinations”) were excluded due to weak/discordant item–total correlations and conceptual misalignment with the remaining items; the final DBE composite was computed on the six retained items.

- Potential common method bias (CMB) was preliminarily assessed using Harman’s one-factor test (Principal Component Factor Analysis—PCF) on all 36 individual items comprising the final scales.

- Beyond Harman’s single-factor test, we contrasted a one-factor model (all items loading on a single latent factor) with a four-factor measurement model (VPA, APA, YI, and DBE). The single-factor model exhibited poor fit (RMSEA = 0.113; CFI = 0.755; SRMR = 0.087), whereas the four-factor model exhibited an improved fit (RMSEA = 0.091; CFI = 0.842; SRMR = 0.059), suggesting the data are not dominated by a single common factor. Procedural remedies were also implemented (anonymity, clear instructions, fixed item grouping).

- Convergent validity was evaluated by examining standardized item loadings from separate Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) for each construct. Discriminant validity was assessed by examining the inter-construct correlation matrix (Pearson’s r) and applying the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which involved comparing the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE, calculated from CFA loadings) with inter-construct correlations.

- In each single-factor CFA we computed AVE and Composite Reliability (CR) from standardized loadings (adequacy thresholds: AVE ≥ 0.50; CR ≥ 0.70). Discriminant validity was assessed via the Fornell–Larcker criterion by comparing √AVE with inter–construct correlations. As reported in the Results, VPA and APA did not meet the Fornell–Larcker requirement, which informed our choice to test the hypotheses using path analysis on observed composites with robust SEs, complemented by a latent SEM as a robustness check.

- The primary analytical strategy involved path analysis on observed composite scores using the SEM command. Based on the normality test results, all models were estimated using Maximum Likelihood (ML) with robust standard errors (vce(robust)). Two main path models were evaluated:

- A moderation model testing direct and interaction effects on YI (using mean-centered predictors for interactions).

- A mediation model assessing DBE’s potential mediating role. The proportion of variance explained in YI was assessed using R-squared (R2), and predictor importance using Cohen’s effect size (f2), derived from auxiliary linear regressions. Overall model fit indices were not applicable for these path models.

- All items were drawn from established scales and adapted to the Dhofar context (see Appendix A). After reliability checks, we formed unit-weighted composites for each construct (arithmetic means). As a robustness check, we estimated models using CFA factor scores; the pattern of results was unchanged.

- We interpret impacts using unstandardized coefficients (β), Cohen’s f2 (small ≈ 0.02, medium ≈ 0.15, large ≈ 0.35), and R2.”

- As a robustness check and to account for measurement errors, a full Structural Equation Model (SEM) with latent variables was estimated for the mediation structure, specifying VPA, APA, YI, and DBE as latent factors, also using ML with robust standard errors. Its fit was assessed using the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) and the Coefficient of Determination (CD).

4. Results

Initially, Table 1 is resented that shows the demographics of the respondents who participated in the study. The initial assessment for internal consistency detected a high level for scale reliability coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha for VPA (0.9386), APA (0.9386), and YI (0.9490). The inter-construct correlation matrix (Table 2) revealed a critically high positive correlation between VPA and APA (r = 0.8937, p < 0.001), indicating severe multicollinearity. Both VPA and APA showed strong positive correlations with YI (r = 0.829 and r = 0.891, respectively; p < 0.001). DBE exhibited weak, non-significant correlations with VPA and APA, but a small, statistically significant negative correlation with YI (r = −0.106, p = 0.030). The initial assessment of the DBE scale revealed that two items—DB_1 (“Dhofar is very famous”) and DB_5 (“Dhofar is better than other similar destinations”)—exhibited weak correlations with the rest of the scale and were deemed conceptually divergent, possibly reflecting symbolic dimensions not aligned with youth perceptions. Consequently, these two items were excluded, and the final DBE composite index was calculated using the remaining six items.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the constructs.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation matrix among composites (VPA, APA, YI, and DBE). p < 0.001 for starred coefficients.

Normality tests (sktest) confirmed significant non-normality (p < 0.05) for all four composite constructs (VPA, APA, YI, and DBE), validating the use of robust standard errors in subsequent SEM analyses.

Harman’s one-factor test performed on all individual items indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 50.8% of the total variance; while not exceeding common thresholds definitively, this substantial proportion suggests that Common Method Bias (CMB) warrants caution in interpretation.

CFAs show high standardized loadings for VPA, APA, and YI, while three DBE indicators are comparatively weaker. Convergent validity is adequate for VPA (CR = 0.939; AVE = 0.633; √AVE = 0.795), APA (CR = 0.943; AVE = 0.623; √AVE = 0.789), and YI (CR = 0.949; AVE = 0.630; √AVE = 0.794); for DBE (CR = 0.803; AVE = 0.423) it is marginal. Discriminant validity between VPA and APA is not met under the Fornell–Larcker criterion (r = 0.8937 > √AVE_VPA = 0.795 and √AVE_APA = 0.789), confirming substantial empirical overlap. Accordingly, the primary analyses use path models on observed composites with robust SEs, complemented by a latent-variable SEM as a robustness check.

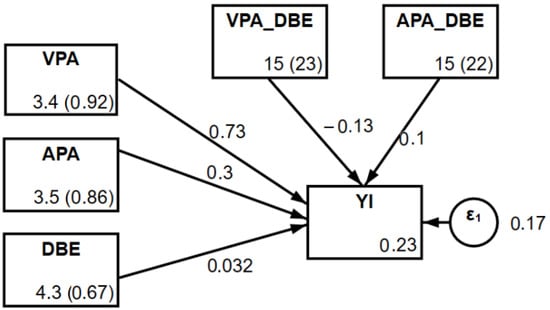

The moderation model, estimated using path analysis with robust standard errors (Figure 1 and Table 3), revealed significant direct effects.1 APA emerged as the dominant positive predictor of YI (β = 0.735, p < 0.001). VPA also had a significant positive effect, albeit smaller (β = 0.166, p = 0.006). Notably, DBE exerted a significant negative direct effect on YI (β = −0.063, p = 0.016). Critically, neither interaction term reached conventional significance levels: the VPA × DBE interaction was marginal (β = −0.131, p = 0.098), and the APA × DBE interaction was clearly non-significant (β = 0.102, p = 0.224). These findings, based on robust estimation, differ notably from preliminary non-robust analyses, particularly regarding the non-significance of the VPA × DBE interaction. The overall variance explained in YI by the main predictors (VPA, APA, and DBE) was substantial (R2 = 0.802). Cohen’s f2 effect sizes confirmed the primary role of APA (f2 = 0.575, large effect), followed by VPA (f2 = 0.023, small effect) and DBE (f2 = 0.016, small effect) in explaining the variance in YI.

Table 3.

Structural equation model results (dependent variable: youth inclination, YI; N = 415).

The mediation model, also estimated with robust standard errors (Table 4), confirmed the lack of a mediating role for DBE. Neither VPA nor APA predicted DBE (p = 0.136 and p = 0.395, respectively). Consequently, the indirect effects of VPA and APA on YI via DBE were non-significant (p = 0.229 and p = 0.439). However, the model confirmed significant direct effects on YI from VPA (β = 0.148, p = 0.012), APA (β = 0.759, p < 0.001), and DBE (β = −0.065, p = 0.014). Total effects on YI remained significant for VPA (β = 0.157, p = 0.007) and APA (β = 0.754, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Direct, indirect, and total effects from the SEM mediation model.

Finally, the full latent variable SEM, estimated for the mediation structure to account for measurement errors, achieved reasonable fit (SRMR = 0.059, CD = 0.988) and provided further insights. It strongly corroborated the lack of discriminant validity between VPA and APA at the latent level (estimated correlation Φ = 0.951). The latent structural paths reinforced the dominant positive impact of APA_Lat2 on YI_Lat (β = 1.111, p < 0.001) and the significant negative impact of DBE_Lat on YI_Lat (β = −0.063, p = 0.042). Notably, in this latent model, the direct path from VPA_Lat to YI_Lat became non-significant (p = 0.196). The absence of mediation via DBE was also upheld at the latent level. These latent variable results generally align with the path analysis findings but highlight the dominance of APA and reinforce the negative DBE effect when measurement error is considered. This result may suggest that the impact of perceived value (VPA) is largely mediated or absorbed by awareness (APA), especially when constructs are defined at the item level, allowing for the internal variance structure to emerge more clearly. Therefore, although the model with composite indicators provides a clear and interpretable framework, the latent model underscores the conceptual overlap between VPA and APA, which should be carefully considered in future research and measurement design.3 The latent SEM corroborated the dominance of APA and the negative DBE effect while showing that VPA’s direct path to YI became non-significant once measurement error and the overlap with APA were modeled explicitly, underscoring the caution needed when attributing unique effects to VPA in composite-score regressions.

Sensitivity analyses. To probe the APA/VPA overlap, we re-estimated the moderation model using (i) APA only and (ii) VPA only as predictors of YI (plus DBE and interactions). Conclusions were unchanged: APA remained a strong positive predictor (R2 ≈ 0.79; APA f2 ≈ 0.58), whereas VPA alone yielded a smaller positive association (R2 ≈ 0.69). In both specifications, DBE retained a small negative direct effect and no significant interactions emerged.

This study investigated the interplay between perceptions of performing arts (value—VPA; awareness—APA), destination brand equity (DBE), and youth inclination (YI) towards territorial engagement in the region as shown in Figure 2. In the following are the answers to the research questions:

Figure 2.

Path analysis. Source: Stata 17 output on authors’ input.

- 1.

- Does the perceived value of performing arts (VPA) positively influence youth inclination (YI)?

Yes, the results indicate a positive and statistically significant effect of VPA on YI when measured as a composite score (β = 0.166, p = 0.006 in the moderation model; β = 0.148, p = 0.012 in the mediation model). However, this effect disappears in the latent variable model once measurement error and the overlap with APA are accounted for (p = 0.196), suggesting that the unique contribution of VPA may be overestimated in composite models due to its empirical redundancy with APA.

- 2.

- Does awareness of performing arts (APA) influence youth inclination (YI)?

Absolutely. APA consistently emerges as the strongest and most stable predictor of YI across all models. In both composite and latent models, APA has a large, positive, and highly significant effect (e.g., β = 0.735, p < 0.001 in the moderation model; β = 0.759, p < 0.001 in the mediation model; β = 1.111, p < 0.001 in the latent SEM). This reinforces the idea that awareness of cultural practices is a key driver of youth engagement within the territory.

- 3.

- Does destination brand equity (DBE) have a direct effect on YI?

Yes, and unexpectedly, the effect is negative and significant in all models (e.g., β = −0.063, p = 0.016 in the moderation model; β = −0.065, p = 0.014 in the mediation model; β = −0.063, p = 0.042 in the latent SEM). This finding suggests that higher perceptions of brand equity are associated with lower youth inclination, potentially indicating a misalignment between the official brand narrative and youth identity or expectations.

- 4.

- Does DBE moderate the relationship between VPA/APA and YI?

No. While the interaction term VPA × DBE was marginally negative in preliminary non-robust models (p < 0.05), it did not reach statistical significance when robust standard errors were applied (β = −0.131, p = 0.098). The APA × DBE interaction was clearly non-significant (β = 0.102, p = 0.224). Therefore, no moderating effect of DBE was confirmed on either path.

- 5.

- Does DBE mediate the relationship between VPA/APA and YI?

No. Neither VPA nor APA significantly predicted DBE (VPA → DBE: p = 0.136; APA → DBE: p = 0.395), and the indirect effects were non-significant as well (VPA: p = 0.229; APA: p = 0.439). Hence, DBE does not function as a mediator between performing arts perceptions and youth inclination.

The findings offer several insights but also highlight important methodological considerations.

Firstly, the refinement of the destination brand equity (DBE) scale required the exclusion of two items: DB_1 (“Dhofar is very famous”) and DB_5 (“Dhofar is better than other similar destinations”). These items, relating to broad fame and comparative superiority, correlated weakly or negatively with other DBE items focusing on attractiveness, uniqueness, and quality of life aspects. Their removal improved the scale’s consistency (α = 0.821) and subsequent model performance. This suggests that the symbolic dimensions of fame and competitive standing, often central to official branding narratives, may not resonate positively or consistently with the youth’s perspective in Oman. Young people might perceive these macro-level brand attributes differently, or even negatively, compared to more tangible aspects of the region’s identity, hinting at a potential disconnect between official branding and youth perceptions.

Secondly, a critical methodological finding emerged regarding the discriminant validity between Value of Performing Arts (VPA) and Awareness of Performing Arts (APA). The extremely high correlation (r = 0.8937) and the failure to meet the Fornell–Larcker criterion (sqrt(AVE_VPA) = 0.795 < 0.8937; sqrt(AVE_APA) = 0.789 < 0.8937) strongly indicate that these two constructs were not empirically distinct in our sample. This suggests a significant conceptual overlap, where valuing local arts and being aware of them are almost indistinguishable aspects of the same underlying positive orientation or engagement. Statistically, this manifested as severe multicollinearity, complicating the interpretation of the unique contribution of VPA versus APA in the multivariate models. While both constructs are clearly important drivers of youth inclination (YI), as evidenced by their strong bivariate correlations and the large f2 for APA, attributing specific unique effects based on the regression coefficients should be performed with extreme caution. The robust models suggest APA (awareness) is the statistically dominant predictor when both are included, possibly reflecting that awareness is a more proximal antecedent to inclination than value alone, but this interpretation is tentative given the lack of discriminant validity.

Thirdly, the substantive findings from the robust path models revealed a compelling picture. Both VPA and APA positively predict YI, confirming the central role of performing arts perception in fostering youth engagement. However, destination brand equity (DBE) consistently showed a significant negative direct effect on YI. This counterintuitive finding suggests that a higher perceived brand equity, as measured by this scale, is associated with lower youth inclination towards territorial engagement. This warrants further investigation, potentially through qualitative methods, to understand why a seemingly positive brand image might alienate or disengage youth. It might relate to perceptions of authenticity, commercialization, or a mismatch between the brand image and youth identity.

Furthermore, the moderation analysis using robust standard errors did not support the initial hypothesis (or preliminary non-robust findings) that DBE negatively moderates the VPA–YI relationship. The interaction effect, while negative, was not statistically significant (p = 0.098). Therefore, based on this more reliable analysis, we find no evidence that a strong brand perception significantly weakens the positive link between valuing performing arts and youth inclination. The mediation analysis also confirmed that DBE does not function as an intermediary between VPA/APA and YI.

This study has several limitations. Conceptually, the empirical indistinguishability between VPA and APA suggests that “valuing” and “being aware of” performing arts may reflect a single underlying orientation among youth. This is indicated by the Fornell–Larcker criterion on composites (r = 0.894 exceeding √AVE for both VPA = 0.795 and APA = 0.789) and by the very high latent correlation in the full SEM (Φ ≈ 0.951). Substantively, the small but consistent negative DBE→YI association may reflect a misalignment between institutional branding frames and youths’ lived identities; qualitative follow-ups (e.g., focus groups) could test mechanisms such as perceived commercialization or authenticity loss. Policy-wise, the evidence points to prioritizing awareness-raising and meaningful access over top-down destination branding if the goal is to foster youth engagement.

On measurement, DBE shows marginal convergent validity (AVE = 0.423), warranting cautious interpretation and future refinement of indicators. Regarding APA/VPA, future work could (a) model a higher-order Performing Arts Orientation factor subsuming awareness and value, or (b) sharpen item content to separate familiarity/knowledge from attitudinal valuation (e.g., scenario-based and behavioral-frequency items), reassessing discriminant validity via EFA/CFA and HTMT. Finally, potential common method bias remains a concern in a cross-sectional, single-source design: although our four-factor measurement model fit better than a one-factor solution and robust SEs were used, future studies should add procedural (temporal/psychological separation) and statistical remedies (marker variable or latent method factor). The latent SEM offered useful robustness checks—confirming the negative DBE effect and the absence of mediation—while showing that VPA’s direct path to YI vanishes once measurement error and overlap with APA are accounted for, underscoring the importance of improved construct delineation.

Despite these limitations, the study underscores the vital importance of awareness and perceived value of local performing arts for engaging youth. It also raises critical questions about the effectiveness and resonance of current destination branding strategies with the younger generation in Oman, highlighting a potentially counterproductive negative relationship between brand equity and youth inclination. Future research should aim to refine the measurement of VPA and APA to achieve better discriminant validity, employ methods to mitigate CMB, and explore the complex, potentially negative, role of destination branding on youth engagement through mixed methods approaches.

5. Discussions

The aim of this study is twofold; first it aims to investigate the relationship between the interest in the value of performing arts and the awareness of the value of performing arts could influence the inclination of local youth to perform art activities in Oman. Secondly, this study explores whether the perceived brand equity moderates this relationship.

Our results confirmed that there is a positive relationship between the interest in the value of performing arts and the inclination of local youth to perform art activities (H1 is supported). This result is in line with the theoretical underpinning of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which stipulates that individuals are likely to be more engaged and motivated in performing certain activities (i.e., artistic activity) that are personally meaningful or valuable to them. It could be argued that interest in the value of performing arts allow local youth to self-express themselves and thus provide a sense of autonomy and it further enhances relatedness by allowing youth to connect and collaborate with each other. Our result empirically justifies the argument of Chung (2021) that a lack of interest in valuing arts activities results in less engagement and youth participation in performing art activities.

Vanherwegen and Lievens (2014) argued, based on the culture reproduction theory, that education and social aspects are relevant factors in influencing active participation in arts activities. This theory of cultural reproduction contends that certain cultural and habitual aspects are reproduced across generations and transmitted to one generation to another through education and practices. Over time, local youth grow up and internalize the value of appreciating performing arts. The role of community, family, and school is vital during this process to instill this value and therefore it will be translated into more inclinations to perform art activities. Catterall (2012) affirmed the role of education as an essential mechanism to embed the value of arts among youth during their childhood. Ennis and Tonkin (2018) provided further evidence as to why youth would value performing arts activities and they articulated this by providing empirical justification that youth put emphasis on wellbeing and leisure values which could justify their inclination towards performing arts.

Furthermore, our results confirmed that there is a positive relationship between the awareness of performing art and youth inclination towards performing arts. When local youth in Oman are made aware or familiar with art performances, they tend to develop an interest and preference towards these artistic events. Awareness campaigns could signal the message that performing arts are still relevant and current and therefore attract youth attention to perform arts. Montoya et al. (2017) argued based on the mere exposure effect of the model that individuals tend to recognize, prefer, and like events that they are repeatedly exposed to. For example, local youth will be likely to recognize, prefer, and like performing arts activities, because they are exposed to them during awareness campaigns. These local youth tend to prefer what they are familiar with. Awareness breeds familiarity, appreciation, and ultimately, action.

Although counterintuitive, a small negative association between Destination Brand Equity and youth inclination can arise when branding emphasizes external audiences more than local participation. Perceptions of commercialization (authenticity loss), brand–identity dissonance, or a shift in attention/resources from access and training to outward promotion may reduce youths’ willingness to engage. These mechanisms align with sustainability concerns around inclusivity and community co-benefits. We therefore recommend co-creating branding narratives with youth stakeholders, rebalancing investments toward access (spaces, mentors, and micro-grants), and evaluating branding content for inclusivity and authenticity.

Moreover, our results indicated that Destination Brand Equity is not a significant moderator in the relationship. Theoretically, a higher positive perception about a destination would make the local place of higher interest in valuing performing arts and because of this it would lead to more inclination towards performing arts. In addition, the brand equity of a destination increases the awareness of such a destination and in return leads to more inclination towards performing arts. However, this theoretical underpinning did not receive empirical support in the context of Oman. It seems that for the local youth in Oman, their inclination towards performing arts is influenced by other factors rather than city or destination where the performing arts are located. These factors are related to their intrinsic motivation, such as self-expression, passion, and the need for leisure and wellbeing. Therefore, we could argue that local youth in Oman may derive their interest in performing local arts driven by intrinsic needs that are independent of the location of where the arts are performed. To support this, Mornell (2012) regarded that intrinsic motivational factors are crucial in guiding individuals towards performing arts, because they are fundamental aspects that guide an individual’s behavior towards achieving their best in different contexts.

6. Conclusions

The main objective of this study is to investigate whether the relationship between the interest in the value of performing arts and the awareness of the value of performing arts could influence the inclination of local youth to perform art activities and explore whether they perceive brand equity.

In this study, a structured questionnaire was conducted to a sample of young residents in the Dhofar region (N = 415). The measurement instrument was developed based on the established literature concerning youth behavior, territorial branding, and the perceived value of performing arts. All items were measured using five-point Likert scales.

The results indicate a positive and statistically significant effect of VPA on YI. Furthermore, our results confirmed that there is a positive relationship between the awareness of performing arts and youth inclination towards performing arts. Moreover, our results indicated that destination brand equity is not a significant moderator in the relationship, which means that no moderating effect of DBE was confirmed on either path. These results are alien to those of Catterall (2012), Ennis and Tonkin (2018), Montoya et al. (2017), and Mornell (2012).

The findings of this study offer some policy implications to policymakers to sustain creating interest in valuing traditional arts performance and increases the awareness of these types of events that are influential factors in shaping youth inclination towards performing traditional arts. The study suggests that generating awareness is vital in creating the intention among local youth to perform traditional arts. These findings suggest that policymakers can provide support for traditional art performances by devising an institutional policy that provides structural support to increase interest and awareness.

6.1. Implications

This study underscores the need of preserving intangible cultural heritage by stimulating interest and developing suitable practices to make the youth inclined towards performing traditional arts. To do so, the study empirically highlighted that creating interest in valuing traditional arts performance and increasing the awareness of these types of events are influential factors in shaping youth inclination towards performing traditional arts. We offer a set of recommendations to develop the interests of valuing and promoting the awareness of traditional arts in Oman in an effort towards preserving one of the most important aspects intangible cultural heritage in the region.

First, the community is responsible for fostering early exposure to the importance of preserving intangible cultural heritage as an important aspect of identity reflection. For this purpose, the role of the community is to develop some early exposure strategies to instill these values among the youth in Oman. For example, incorporating traditional arts into the curriculum in early stage of schools by educators can provide an early exposure mechanism for youth to appreciate the value of intangible heritage by sustaining the practices of traditional performance arts as part of identity reflection of the region. Furthermore, schools, colleges, and universities as part of their community role are encouraged to design events to promote the importance and interests among youth. Therefore, organizing traditional heritage events including art performances will embed interest values among the youth and they will become more confident in performing arts. Moreover, partnerships with professional artistic performers are decisive in promoting interests and awareness among local youths. These professionals can demonstrate art performing and storytelling sessions towards enhances the participation and the acceptance of arts performance among the youth. Incentives and recognition can play an important role in creating interest in valuing traditional art performance. This includes granting a scholarship for young performers and rewarding them accordingly.

6.2. Policy Implications

At country level, it is recommended to provide support for traditional art performances by devising an institutional policy that provides structural support to increase the interest and the awareness of performing arts among the local youth. Such a policy should facilitate the provision of the essential resources that enable the performance of traditional arts and mandate the requirement of integrating such elements into the educational program at different levels (schools and universities). Thus, in the curriculum for the promotion of tourism and culture, the concept of destination brand equity and the promotion of traditional activities should be added.

On the other hand, generating awareness is vital in creating the intention among local youth to perform traditional arts. Thus, the government should launch campaigns using social media to promote Omani culture, and for the promotion of Omani arts, especially performing arts. Therefore, the utilization of social media campaigns may prove to be a valid option for the tourism and heritage ministry in Oman. Such campaigns should aim to highlight the history and beauty of traditional performances.

6.3. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Despite the several policy and practical implications, the study has certain limitations. The first limitation is regarding the culture, as people, even those who were involved in performing arts were hardly motivated to participate in the study, unless they confirmed that their identities would not be revealed. Moreover, the construction of destination brand equity needs to be enriched with more information. The variable of destination brand equity needs to be evaluated for an additional three angles including self-congruity, authenticity, and place identity. The addition of these dimensions to destination brand equity will help to align the variable with brand meanings relevant to young people. Additionally, considering the negative effect of destination brand equity, which is surprising, there is a great need to conduct a qualitative study. Qualitative studies will identify a better way to understand the phenomenon under observation, hence, in the future researchers are recommended to conduct a qualitative study over destination brand equity, where data collection is a challenge due to cultural issues. Moreover, the same aspects but with different meanings are followed in European countries; thus, comparing Omani cultural festivals and cultural activities with other festivals in Edinburgh or Stratford upon Avon may provide a more in-depth analysis and comprehension.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; methodology, M.A.; software, E.d.B.; validation, A.Q.; formal analysis, E.d.B.; investigation, M.A.B.A.S.; resources, M.A.B.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.O.B.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and L.E.-M.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, E.d.B.; project administration, M.A.B.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The corresponding author on behalf of all the authors of the paper, declare that the Ministry of Higher Education Research & Innovation, Oman has sponsored this study under the grant number; BFP/RGP/CBS/23/065.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to get an exemption from the Dhofar University Research Ethics & Biosafety Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The use of verbal consent was deemed most appropriate to protect participant anonymity and confi-dentiality, given the cultural issues. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Dhofar University Research Ethics & Biosafety Committee. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research, procedures, risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the Mohammed Ali Bait Ali Sulaiman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendix A

Items used for the measurement of constructs.

- Interest in the Value of Performing Arts Among Local Youths

- I enjoy participating in Dhofarian performing arts activities.

- I believe that Dhofarian performing arts contribute positively to my community.

- I think that Dhofarian performing arts are an important form of self-expression.

- I have access to Dhofarian performing arts programs in my area.

- I feel that participating in Dhofarian performing arts enhances my social skills.

- I think that Dhofarian performing arts can help reduce stress and improve mental wellbeing.

- I have attended a Dhofarian performing arts event in the past year.

- I believe that engaging in Dhofarian performing arts can improve my creativity.

- I think that Dhofarian performing arts should receive more funding and support from local governments.

- Awareness of the Value of Performing Arts Among Local Youths

- I am aware of different forms of Dhofarian performing arts.

- I believe that Dhofarian performing arts play an important role in cultural heritage.

- I understand how Dhofarian performing arts can impact personal development.

- I know of local organizations that promote Dhofarian performing arts for youth.

- I am aware of events and programs related to performing arts in my area.

- I understand that Dhofarian performing arts can enhance emotional intelligence.

- I know that Dhofarian performing arts can provide opportunities for collaboration and teamwork.

- I believe that Dhofarian performing arts can promote inclusivity and diversity.

- I have seen or heard discussions about the importance of Dhofarian performing arts in the media.

- I feel that Dhofarian performing arts are valued in community.

- Youth Inclination Towards Performing Arts

- I am interested in participating in Dhofarian performing arts activities.

- I believe that Dhofarian performing arts are a valuable way to express myself.

- I would like to take classes related to Dhofarian performing arts.

- I think Dhofarian performing arts provide a fun way to socialize with peers.

- I often seek out opportunities to attend Dhofarian performing arts events.

- I believe that participating in Dhofarian performing arts can enhance my confidence.

- I find Dhofarian performing arts to be an important part of youth culture.

- I think Dhofarian performing arts can positively impact my future career prospects.

- I would recommend participating in Dhofarian performing arts to others my age.

- I often engage with Dhofarian performing arts through social media or online platforms.

- I feel that Dhofarian performing arts should be promoted more in schools and community programs.

- Destination Brand Equity

- Dhofar is well known and recognized among young people.

- When I want to enjoy cultural or social activities, Dhofar is the first place that comes to mind.

- Dhofar consistently offers enjoyable and high-quality experiences for young residents.

- I always have positive and memorable experiences in Dhofar.

- Compared with other places in Oman, Dhofar offers a more authentic and enjoyable experience.

- Dhofar reflects my personality and lifestyle as a young person.

- My friends and peers think positively about people who engage with Dhofar’s culture and events.

- Dhofar is my preferred destination for leisure, relaxation, and cultural experiences.

Appendix B

| Economic Prosperity (Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 8) | Diminishing Inequalities (SDG 10) | Sustainable Urban Cities and Communities (SDG 11) | Responsible Production and Consumption (SDG 12) |

|

|

|

|

Notes

| 1 | Global model fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA) are not reported as the estimated path analysis models were saturated/just-identified (df = 0), precluding a global test of fit; model evaluation relies on path significance, R2, and theoretical consistency, as outlined in the Methods. |

| 2 | APA_Lat (10 items), VPA_Lat (9 items), YI_Lat (11 items), and DBE_Lat (6 items) are latent constructs estimated using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) based on the corresponding sets of observed indicators. |

| 3 | The full output of the latent variable SEM is not reported in detail in this paper for the sake of brevity, as its primary role is to account for measurement error. Nonetheless, the main findings are clearly summarized in this paragraph and broadly align with the composite-based models. |

References

- Abbing, H. (2019). The changing social economy of art. Springer Books. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis, P. (2020, June 10–11). Dancing to enhance the destination image: Co-creating a guinness world record. Tourism Hospitality Events, International Conference (p. 36), Kyoto, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, M., Fryan, L. H., & Shomo, M. I. (2025). Sustainable entrepreneurial intention among university students: Synergetic moderation of entrepreneurial fear and use of artificial intelligence in teaching. Sustainability, 17(1), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M., Sulaiman, M. A., Awain, A. M., Alsoud, M., Allam, Z., & Asif, M. U. (2024). Green entrepreneurial leadership, and performance of entrepreneurial firms: Does green product innovation mediates? Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2355685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, A., Bille, T., Ellero, A., & Favaretto, D. (2018). Revenue and attendance simultaneous optimization in performing arts organizations. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, E. P., Wong, M. D., Kataoka, S. H., & Zimmerman, F. J. (2022). A symphony within: Frequent participation in performing arts predicts higher positive mental health in young adults. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F. (2004). Performing arts attendance: An economic approach. Applied Economics, 36(17), 1871–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breed, A., Marambio, H. U., Pells, K., & Timalsina, R. (Eds.). (2024). Children, youth, and participatory arts for peacebuilding: Lessons from Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia, and Nepal. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Catterall, J. S. (2012). The arts and achievement in at-risk youth: Findings from four longitudinal studies (Research Report# 55). National Endowment for the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Cetină, I., & Bădin, A. L. (2019). Creative and cultural industries in Europe–case study of the performing arts in Romania. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, 13(1), 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. L. (2021). Cultural product innovation strategies adopted by the performing arts industry. Review of Managerial Science, 15(5), 1139–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. C., King, B., & Lee, H. W. (2018). Experiencing the destination brand: Behavioral intentions of arts festival tourists. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 10, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F. M. Y. (2021). Developing audiences through outreach and education in the major performing arts institutions of Hong Kong: Towards a conceptual framework. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 14(3), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. (Ed.). (2019). Urban events, place branding and promotion: Place event marketing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cudny, W. (Ed.). (2021). Place event marketing in the Asia Pacific region: Branding and promotion in cities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davico, C., Rossi Ghiglione, A., Lonardelli, E., Di Franco, F., Ricci, F., Marcotulli, D., Graziano, F., Begotti, T., Amianto, F., Calandri, E., Tirocchi, S., Carlotti, E. G., Lenzi, M., Vitiello, B., Mazza, M., & Caroppo, E. (2022). Performing Arts in Suicide Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daykin, N., Orme, J., Evans, D., Salmon, D., McEachran, M., & Brain, S. (2008). The impact of participation in performing arts on adolescent health and behaviour: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(2), 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M., & Humm-Delgado, D. (2017). The performing arts and empowerment of youth with disabilities. Pedagogia Social Revista Interuniversitaria, 30, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (2024). Democracy and education. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, Y., & Hosany, S. (2006). Destination personality: An application of brand personality to tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, G. M., & Tonkin, J. (2018). ‘It’s like exercise for your soul’: How participation in youth arts activities contributes to young people’s wellbeing. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(3), 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitryansyah, M. A. (2024). Perceptions and attitudes of urban Muslim youth towards modernity and globalization. al-Madinah: Journal of Islamic Civilization, 1(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, G., & Robinson, P. (2011). Events, festivals, and the arts. In Research themes for tourism (pp. 128–145). CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Gulvady, S., Soliman, M., Almuhrzi, H., & Al-Aamri, M. S. H. (2023). Cultural tourism and community development: Dhofar governorate as a case. In Exploring culture and heritage through experience tourism (pp. 169–179). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G. Q., & Liem, G. A. (2025). The impact of co-curricular activities on youth development: A self-determination theory perspective. Trends in Psychology, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. S., & Kim, J. H. (2021). Performing arts and sustainable consumption: Influences of consumer perceived value on ballet performance audience loyalty. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S., Rowley, J., & Keegan, B. (2021). Place and destination branding: A review and conceptual mapping of the domain. European Management Review, 18(2), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R., Mohamad, W. S. N. W., Hassan, K., Noordin, M. A. M. J., & Ramlee, N. (2023, April). A study on youth awareness towards cultural and heritage in Kelantan state. In AIP conference proceedings (Vol. 2544, No. 1). AIP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, F. (2022). Artistic production and (re)production: Youth arts programmes as enablers of common cultural dispositions. Cultural Sociology, 16(4), 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. C., & Bendle, L. J. (2012). Arts tourism in Seoul: Tourist-orientated performing arts as a sustainable niche market. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(5), 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C. Y., Tsai, C. H., Su, C. H., & Chen, M. H. (2023). From stage to a sense of place: The power of tourism performing arts storytelling for sustainable tourism growth. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(8), 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masunah, J. (2017). Creative industry: Two cases of performing arts market in Indonesia and South Korea. Humaniora, 29(1), 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mazlan, C. A., Abdullah, M. H., Hashim, N. S., Wahid, N. A., Pisali, A., Uyub, A. I., & Hidayatullah, R. (2025). Discovery the intersection of performing arts in cultural tourism: A scoping review. Discover Sustainability, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., Vevea, J. L., Citkowicz, M., & Lauber, E. A. (2017). A re-examination of the mere exposure effect: The influence of repeated exposure on recognition, familiarity, and liking. Psychological Bulletin, 143(5), 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mornell, A. (2012). Art in motion: Motor skills, motivation, and musical practice. II. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A. M. (2020). Marketing and managing city tourism destinations. In Routledge handbook of tourism cities (pp. 135–161). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mukoyani, L. M. (2022). Role of cultural diversity in influencing the destination brand equity of Mombasa county, Kenya [Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University]. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A. C., Dawkins, C. J., Ganning, J. P., Kittrell, K. G., & Ewing, R. (2016). The association between professional performing arts and knowledge class growth: Implications for metropolitan economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 30(1), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, D. S. (2021). The arts and culture sector’s contributions to economic recovery and resiliency in the United States. In Key findings. National Assembly of State of Arts Agencies. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, A., Marturano, N., O’Connor, G., & Meek, R. (2018). Marginalised youth, criminal justice and performing arts: Young people’s experiences of music-making. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(8), 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]