Abstract

While place branding strategies are increasingly implemented in rural tourism, they are criticised for issues of exclusion and homogenisation. In response, attempts have been made to rejuvenate place branding by integrating the ideology of place-shaping. To explore the conceptual distinctions between place branding and place-shaping, and the potential for integrating these two approaches, this paper examines the process of tourism programme and beyond in a peripheral rural community in Southwest China. This case study collected qualitative data from 2016 to 2023 to describe how the village was transformed by a top-down tourism initiative and how local stakeholders subsequently shaped these changes. Our empirical investigation reveals that sustainable rural tourism development requires integrating place branding strategies with the place-shaping process. While the administrative and financial support was required to promote the place branding, the exogenous approach led to a brand alien to the place. In contrast, residents and other stakeholders have shaped a living place beyond the programme. It entails an integration where elements from the place branding and place-shaping are recruited, reinterpreted, and reconfigured to support sustainable, place-based development.

1. Introduction

Rural areas have changed from territories primarily organised around agricultural production to places where non-agricultural and non-economic objectives are increasingly important. These objectives include providing rural amenities, conserving biodiversity and ecosystems, and preserving socio-cultural landscapes. Within this context, rural tourism, which has been particularly theorised as a powerful reconfiguration of resources, provides an example of the new potential and uncertainty for rural development. The economic, sociocultural and environmental benefits of rural tourism have been recognised in the literature (Frederick, 1993; Sharpley & Roberts, 2004; Su et al., 2018). However, scholars have also expressed concerns regarding the commodification of rurality and the risk of creative destruction (Crouch, 2006; Rosalina et al., 2021; Tonts & Greive, 2002), particularly as urban consumers and investors increasingly flock to the countryside in pursuit of their imagined rurality.

To attract external consumers and investors, the remote and impoverished countryside, which is declining due to urban sprawl, could be constructed as a natural, picturesque and romantic rural idyll by place branding managers. The making of rurality, crafted through place branding strategies, has faced critiques for its neglect of local stakeholders, issues of homogenisation, and over-emphasis on visual amenity (Johansson, 2012). Attempts to rejuvenate place branding with participatory and inclusive approaches (Mettepenningen et al., 2012; Rebelo et al., 2020) have been made. These efforts blur the distinctions between place branding and place-shaping. It is necessary to make a clearer specification and understanding of these two middle-range concepts, and then explore the potential for integrating concepts and approaches to achieve place-based development—more place-sensitive, cross-sectoral and socially inclusive development (Weck et al., 2022).

This study aims to describe how a village has changed through the place branding strategies in the rural tourism programme and how multiple stakeholders have further shaped these changes. It further explores a critical research question: how can administrative, capital-led place branding strategies evolve into inclusive, sustainable place-shaping practices? To address these questions, an ethnographic case study was conducted in a peripheral rural community in Southwest China between 2015 and 2023. The research makes a marginal contribution by clearly delineating the conceptual boundaries between place branding and place-shaping while identifying the precise conditions for their integration. Ultimately, it provides a transferable framework for practitioners aiming to achieve place-based development.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Comparison

2.1. Place Branding and Place-Shaping

Places, and their range of goods and services, have become increasingly interchangeable (Horlings & Marsden, 2014). Therefore, providing a differentiated image to a place becomes a new rural development practice, especially in tourist villages. Place branding and place-shaping are two of the most widely applied strategies.

Branding strategies have expanded from products to places at the turn of the millennium, aiming to generate a network of associations in the consumers’ minds through visual, verbal, and behavioural expressions (Zenker et al., 2017). Many destinations adopt branding techniques to differentiate their identities and emphasise their uniqueness in a highly competitive market (Morgan et al., 2002). While most research on place branding focuses on countries (Dzenovska, 2005; Ooi, 2008; Szondi, 2007), cities (Andersson, 2016; Johansson, 2012; Rothschild et al., 2012), and tourist destinations (Campelo et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Rabbiosi, 2016), rural areas have recently also received some attention (Donner et al., 2017; Gulisova, 2020). Based on the characteristics and resources of a rural territory, place branding aims to construct and convey a preferred image of a place and to formulate a concept that resonates with a chosen target group (Johansson, 2012). Natural scenic resources, cultural experiences, culinary products and services (Kavoura & Bitsani, 2013; Lee et al., 2015; Vuorinen & Vos, 2013) are considered to serve as “unique selling points” in rural place branding to attract urban visitors. Therefore, place branding has been criticised as a form of neoliberal commodification that reduces places to fungible commodities within the global economy (Vanolo, 2017). Another critique in the literature is that the role of residents in place branding remains ambiguous, and their significance is systematically underestimated (Kavaratzis, 2012). The concept of place branding has evolved consequently. For a decade, place branding referred to an exogenous process driven by promotional and managerial objectives (Boisen et al., 2011; Papadopoulos, 2004; Skinner, 2008). Now it is increasingly understood as co-creative processes involving diverse stakeholders rather than as the outcome of a top-down process (Donner et al., 2017; Gulisova, 2020; Mettepenningen et al., 2012; Rebelo et al., 2020). This conceptual change has led to a significant convergence between the concepts of place branding and place-shaping.

Place-shaping was defined by Lyons, who introduced this term in his report (Lyons, 2007), as a wide range of local activities that affect the well-being of the local community. Unlike place branding, which is relatively focused more on urban areas, place-shaping has been quickly adopted in rural studies. According to Shucksmith (2010), place-shaping is connected with neo-endogenous rural development and new rural governance, in which boundaries between and within public and private sectors have become blurred. Place is understood as a social construct, continuously co-produced and contested in place-shaping. Change and development are no longer seen as linear, directed or predictable. is expressed in practices that are co-created between people and their environment (Horlings, 2016). Place-shaping not only connects people to a place, but also acknowledges their potential transformative agency to shape their place according to their own values, ideas and needs (Horlings et al., 2020).

In the research, the ideology of place-shaping has been gradually integrated into the strategies of place branding to make them more inclusive (Donner et al., 2017; Gulisova, 2020; Mettepenningen et al., 2012; Rebelo et al., 2020).

2.2. Governance and Actor-Network in Rural Development

The integrated theoretical basics and perspectives on governance and Actor-Network Theory (ANT) are required for a comprehensive analysis of rural development programmes.

Governance represents a fundamental shift from hierarchical, top-down government towards structures that include non-statutory actors as decision makers in local development processes (Rhodes, 2007; Furmankiewicz & Macken-Walsh, 2016). A more complex picture has been revealed in the arena of rural development, particularly in China. Here, multi-actor processes are actively shaped by a carefully regulated balance between hierarchical intervention and local initiatives, wherein the state retains a leading role (Oi, 1992; Van der Ploeg et al., 2015). State-led programmes often serve as a fulcrum to leverage rural revitalisation (Shen & Shen, 2022). However, assembled with wide-ranging observations of disastrous consequences caused by state-led development programmes in the global south, Scott (1998) emphasised the risks inherent in authoritarian planning. The concept of authoritarian environmentalism provides a nuanced perspective to understand the role of the state in China. While this non-participatory approach can be effective in policy-making and implementation in the face of severe environmental challenges, it aims can easily be undermined by a fragmented state during the implementation stage. Moreover, the exclusion of social actors and representatives creates a malign lock-in effect wherein low social concern simultaneously makes authoritarian approaches necessary and difficult (Gilley, 2012).

Additionally, the agency of local inhabitants becomes critical in this context. From the governance perspective, power is reconceptualised as a matter of social production rather than mere social control. Local actors are cast as the catalysts for change through collective, neo-endogenous action, mobilising resources to re-assert the place identity (Shucksmith, 2010). Heritage, for instance, is often adopted as an attempt to shape the place identity (Dicks, 2000). But, when the emphasis is placed solely on heritage’s monumental aspects and economic potential, it overlooks its dialectical relationship with place identity, which can provoke passivity or outright rejection from residents (Del Pozo & Gonzalez, 2012). Beyond passive resistance, villagers also actively adopt various development strategies in response to the changing market environment and policy intervention (Lai et al., 2017).

Building on the recognition of multi-actor processes, Actor-Network Theory (ANT) provides a methodology to delve deeper by including both human and non-human elements and tracing how their relationships are formed and translated (Latour, 1996; Law, 2008). All engaged agents, texts, nature environment and all the fluctuations could be preserved in ANT. It leads to a better understanding of the establishment and the evolution of networks (Heeks & Stanforth, 2007). From this perspective, the process of place-shaping can be conceptualised as the effort to build an alternative network, composed of residents, their local knowledge, and daily practices. In contrast, the dominant network of place branding is assembled by developmentalist configuration, scientific and technical knowledge, semiotic and commercial representations.

Furthermore, ANT provides profound implications for spatio-temporal analysis. Harvey (1997) clarified that space and time are not independent realities, but relations of processes and events. Networks pleat and fold space-time through the mobilisations, cumulations and re-combinations that link subjects, objects, domains and locales (Murdoch, 1998). The delineation and characterisation of space-time is useful to think of place (Massey, 1995).

2.3. Conceptual Comparison Between Place Branding and Place-Shaping

Grounded in the literature review and theoretical basis, this research seeks to clarify the concepts of place branding and place-shaping by delineating their conceptual characteristics and formulating operational indicators (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Conceptual Comparison and Operational Indicators: Distinguishing between Place Branding and Place-shaping.

The primary distinction between place branding and place-shaping lies in their interpretation of place. Place branding frames place as an instrumental, marketable product that can be produced, promoted and consumed. In contrast, place-shaping views it as a social construct that is continually co-produced and contested between people and their environment. As mentioned in the literature review, place branding is driven by promotional and managerial objectives, often manifested through market-oriented slogans and measurable economic outcomes which could be identified in official materials. Place-shaping, however, aims at enhancing the well-being of the local community. This is reflected in narratives and actions concerning improved livelihoods, collective initiatives and strengthened cultural identity among local inhabitants.

Place branding and place-shaping are driven by distinct actor-networks and governance models. The former refers to an exogenous, top-down endeavour, driven by a coalition of external actors, including government agencies, enterprises and urban planners, whom has been described as the developmentalist configuration1. Their agency is performed in the decision-making and informing process. External resources and leadership play important roles, whereas local inhabitants are often overlooked as target groups and stakeholders in consultation processes. By contrast, place-shaping is a neo-endogenous and grassroots process where local inhabitants are the dominant actors. This approach is characterised by common consensus, voluntary contributions and actions among local actors.

The type of knowledge system and the resulting manifestations further distinguish these two concepts. Development operators employ their scientific and technical knowledge to construct a marketable brand image. This is manifested through standardised, symbolic, and replicable representations, such as official logos, unified signage and promotional events. Place-shaping, however, is rooted in the local knowledge, for instance, stories, folklore and experiential knowledge spread among local inhabitants. It is disseminated through social and daily practice, manifesting in the adaptive use of resources and the perpetuation of cultural traditions.

The characteristics of space-time are especially different between place branding and place-shaping. Place branding is characterised by clear spatiotemporal boundaries. Its activities are spatially confined to clearly demarcated administrative or geographical zones and temporally marked by clear start and end points, such as the launch of a tourism campaign. In contrast, place-shaping is a pervasive and continuous process in the space-time continuum. It unfolds through the continuity and gradualness of daily life. While Table 1 frames place branding and place-shaping as Weberian ideal types, these distinctions are not mutually exclusive in practice, but rather a continuum ranging from one side to another. Therefore, this empirical research provided a contextualised scenario to explore how place branding and place-shaping strategies are distinctly engaged with rural tourism development. This study also investigates whether and under what conditions these two different practices could be integrated. The integration process should be a mutual reconfiguration where elements from the distinct networks of place branding and place-shaping are recruited, reinterpreted and reconfigured.

3. Methods

3.1. Case Study Area and Background

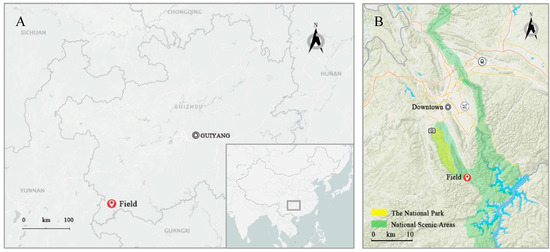

Fieldwork was conducted between 2016 and 2023 in a village named ‘Shilong’ in Guizhou Province, situated in the mountainous southwest of China. This region’s karst landscape is characterised by its fragility and low soil fertility, which has historically resulted in low agricultural productivity and incomes for local farmers. Consequently, Guizhou has recorded the largest number of poor in China, with 4.02 million people living in poverty as of 20162.

New market possibilities are emerging in rural areas, especially in peripheral regions that have not benefited much from urbanisation and industrialisation and where subsistence agriculture has preserved the natural and cultural landscape. Shilong Village is one of the poverty-stricken rural communities in Guizhou, consisting of 46 households with a total population of 182 residents. The village is located near the provincial boundary, distant from both the capital city of Guizhou (Guiyang) and the downtown area of its administrative county (see Figure 1). Although this less-developed mountainous area was designated as a National Park in 2004, Shilong Village derived little benefit from the rural tourism development due to its peripheral location. The village lies 11 kilometres from the main tourist attractions of the National Park, separated by mountain ranges. Nevertheless, its location within the National Scenic Areas (see Figure 1B) subjects it to development restrictions that prohibit environmentally damaging production activities such as breeding and processing industries. As a result, the economic activities within the village have been confined to subsistence agriculture on twenty-one hectares of cultivated land for decades. Younger generations had to migrate for off-farm employment to supplement family income. In 2016, the annual per capita income in the village was only about 4000 yuan (USD 1002 in 2016 PPP prices3), less than one-third of the per capita disposable income of rural residents in China.

Figure 1.

Maps of the field location. Source: Authors’ own work. (A) The geographic location of the field in Guizhou, China; (B) The field location within the city and the National Scenic Areas.

A pivotal change occurred in 2016, when the local government initiated an industrial upgrading in this poverty-stricken village, aiming to transition from subsistence agriculture to commercial fruit production and rural tourism. The intervention was primarily driven by China’s national strategy of poverty alleviation. Poverty alleviation has been a long-term mission for the Chinese government since the Reform and Opening-up in 1978. Through a series of economic and institutional reforms and national anti-poverty strategies, the share of the population living in extreme poverty in China dropped from 88.3% in 1981 to 0.8% in 2016. Eradicating extreme poverty by 2020 was a commitment the Chinese government made in their 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020). In the background of socio-economic transformation, structural poverty rendered the remaining poor more vulnerable. Targeting poverty-stricken households and villages, a total of 128 thousand impoverished villages and 88.4 million poor people were identified across China by June 2016. Shilong Village was one of the identified impoverished villages, enabling customised intervention.

The top-down intervention coincided with a broader socio-economic shift towards a service- and consumption-based economy. A significant growth in demand for rural amenities has emerged, fuelled by an expanding middle class in China. It is within this dual context of targeted poverty intervention and shifting economic demand that the tourism industry was selected as one of the targeted measures to spur economic growth and poverty alleviation in Guizhou province (Donaldson, 2007).

3.2. Data Acquisition

In this ethnographic case study, an actor-oriented approach is adopted to explore the ‘ongoing, socially-constructed, negotiated, experiential and meaning-creating processes’ (Long, 2003) of the tourism development programme in Shilong Village. This approach emphasises the central significance of actors’ agency without undermining the importance of social structure. It further connects broader global and national transformations with the micro interactional settings and localised arenas, allowing for the elucidation of everyday life, representations and institutional and structural constraints within the process of place branding and place shaping.

The empirical data for this ethnographic case study were primarily collected through immersive fieldwork in Shilong Village and its affiliated town government. This was supplemented by selected external trips with officials and experts during their execution of administrative tasks and programme operations. Fieldwork was undertaken over multiple, extended periods: from July to August 2016, January to March 2018, March 2019 and August 2023. This longitudinal fieldwork enabled to trace the process of the rural tourism programme, including its identification, preparation, implementation, stagnation and restart. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, contact with key informants was maintained through social media and phone calls.

A range of social actors were consulted as primary informants (see Table 2). Among local inhabitants, all 46 households in Shilong Village were visited, with 22 residents selected as key informants based on their representations of gender, age, education level and livelihood strategies. Interviews were also conducted with all relevant local government officials, village cadres, staff from the tourism enterprise (referred to as S Ltd. in this research), as well as planners and scholars who are primarily responsible for the rural tourism programme. The catering company was included as it represents one of the most successful external business initiatives, as recommended by both residents and government officials. Additionally, perspectives from inhabitants of neighbouring towns were incorporated through snowball sampling to ensure the inclusion of diverse viewpoints.

Table 2.

List of informants.

To uphold ethical standards and ensure participant anonymity, the names of all interviewees and locations have been omitted, with the exception of the village name. It is because place name constitutes a critical component of any branding processes and simultaneously serve as core symbols of identity (Medway & Warnaby, 2014) in place-shaping. All interviewees, including inhabitants, government officials and experts, provided verbal, informed consent for their involvement in the study, with the explicit understanding that their individual responses would be fully anonymised in all research outputs.

During the fieldwork, the first author resided with a local household in Shilong Village, gradually building rapport and integrating into the local community. Daily interactions, such as participating in villagers’ daily group dances and providing voluntary homework tutoring for local children, served as important avenues for establishing trust. In the role of researcher, the first author was granted permission to participate in the rural tourism programme as a participant observer and became acquainted with government officials and experts. This engagement facilitated unique research access, including permission to attend internal meetings and a one-month residency at the town government office. It enabled sustained observation of the administrative procedures of the programme’s development. The hybrid position facilitated critical understanding of the interplay between top-down initiatives and bottom-up practices, while ongoing reflexivity was maintained to scrutinise the influence of the positionality on data collection and interpretation with the supervision of the second author.

The ethnographic fieldwork allowed for in-depth, repeated interviews and participant observation. This study included 44 formal and numerous informal interviews. A semi-structured interview protocol was applied flexibly, with question guides tailored to different actors. Topics included place-based daily practice and local identity, experiences and perceptions with the tourism programme, and power relationships. Interviews, conducted entirely in Chinese, averaged over one hour in duration, and key informants lasted more than three hours. To minimise potential respondent inhibition, all interviews were documented through detailed field notes rather than electronic recording. Immersive participant observation was conducted, including routines of daily life, community gatherings, festival preparations, official meetings and planning sessions.

Additional qualitative data were derived from secondary documents and co-created resource maps. A wide range of secondary materials was collected, including government policy documents on poverty alleviation and tourism development, internal meeting minutes, and promotional materials for the branding. Furthermore, resource maps were co-created with villagers to visually represent their lived experience of place. The strategic deployment of multiple data collection methods from different types of actors ensured method and data source triangulation (Carter et al., 2014) to enhance the validity and richness of the findings.

A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive thematic analysis was employed to analyse the qualitative data. Initial codes were manually generated and grouped into themes based on the theoretical concepts from the literature review in the deductive analysis, including “objectives”, “approaches & stakeholders”, “knowledge systems” and “manifestations” (see Table 1). Concurrently, data that diverged from these predetermined themes prompted the refinement, grouping and synthesis of codes into the emergent inductive theme, notably “space-time”. This iterative process, moving between the data and theoretical frameworks, enabled the systematic identification and development of all themes concerning the conceptual differences of place branding and place-shaping.

The limitations of this ethnographic case study need to be acknowledged. The findings are inherently context-bound to the field. Furthermore, the gaps between longitudinal field visits, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in some continuous processes that could not be directly observed, relying instead on participant recall during subsequent visits.

4. Place Branding in the Tourism Development Programme

Place branding strategies have been implemented to launch the tourism development programme in the village since June 2016. Following the local government’s guidelines for producing a ‘moderately development-oriented’ village, Shilong Village was renamed, and a series of projects were initiated between June 2016 and December 2017.

4.1. Producing a ‘Moderately Development-Oriented’ Village

The local government’s initial conceptualisation of the village brand emerged in 2016 under guidance from higher-level authorities, branding Shilong as a ‘moderately development-oriented’ village. On 16 July 2016, the prefectural party secretary visited the village, accompanied by a delegation of officials from prefectural, county and town4 levels. Impressed by the well-preserved natural and cultural landscape, the secretary proposed the branding initiative, aiming to avoid over-development and over-commercialisation of rural culture and landscapes.

The secretary (of the prefecture) contrasted Shilong with the overdeveloped tourism villages near the national park, which he likened to “young girls wearing too much makeup”. He pointed out that “we should construct a moderately development-oriented case with comprehensive protection as a model of poverty alleviation through tourism”. He especially emphasised the need to “preserve and revitalise the heritage of local architecture”.(A town cadre, 40s)

In addition to guidance from the prefectural leadership, the national pursuit of a “moderately prosperous society5”—a central policy initiative under the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020)—further shaped the programme’s direction, with poverty alleviation and rural development standing as its fundamental pillars. The conceptual alignment reflects a shared emphasis on balanced development that avoids extremes. Within this framework, scholars and planners who participated in the programme have developed their own interpretations of this balanced development.

For scholars who were invited to provide consultancy services for the programme, the balance entailed reconciling economic development with the conservation of natural and cultural resources. Their perspective was rooted in a humanistic tradition—the epistemological foundation of social sciences—which focuses on rural society, culture, relationships, and interactions between social groups in the scenario of rural development. This orientation often reflects an almost utopian aspiration to harmonise social, economic, cultural and ecological benefits. Notably, this scholarly emphasis on human dimensions resonated with policy discourse, as both the local government and experts formally endorsed the subjectivity of residents, advocating for “people-centred approaches to development”.

“It is necessary to underline some key ideas in the planning and building process, including the concept of harmony between humans and nature based on the mountain agricultural civilisation, the concept of shareable development for poverty alleviation and rural economic development, and the concept of ‘people-centred approaches to development’ with local farmers and their organisations.”(The scholar, 50s)

The planners conceptualised the “moderately development-oriented” brand as a strategic balance between modernism and pastoralism. Modernism is devoted to providing a decent modern life in rural areas. Improved rural infrastructure, adequate sanitation, equipped industrial services and facilities are the most impressive changes in Shilong Village. Pastoralism, conversely, was rooted in the rejection of modernism, leveraging the well-preserved natural and cultural landscape in the village to satisfy the pastoral imagination. Additionally, planners renovated all rural residences to “evoke nostalgia”, as planners said. Roman columns and marble adornment that represented a Westernised aesthetic were removed. The re-enchantment of rurality—amplified by local media—constructed a pastoral myth of rural place.

The vision of the village was summarised by the CEO of the design company as ”returning nature to art, revealing history through the work, and renovating the village with inherent landscape”, so that they could construct a countryside that makes people “enjoy the scenery and remember the nostalgia”.(The planner, 40s)

These dual representational narratives and strategies were properly executed in the branding process. The “moderately development-oriented” village aims to establish a harmonious balance between the needs of residents and urban tourists. For local inhabitants, it serves as a place for living and producing, whereas for tourists, it is a place for leisure and consumption. Through this process, rurality was romanticised into a marketable idyll, endowed with significant exchange value. It thereby functioned as a livelihood base for local farmers while simultaneously serving as a landscape of nostalgia for the urban middle class.

4.2. Renaming the Village

Villages have been named for as long as communities have resided there, and settlements have been established. Place names have served as symbols of local identity, reflecting how residents perceive themselves and their communities. Regarding the name “Shilong6” (石聋), residents shared various stories about a mythical “stone” (Shi in Chinese, 石) in the village—describing it as dragon-like, capable of chirping, or able to transmit sounds over great distances. However, these narratives culminate in a common memory of loss, marked by the stone’s breakage or fallen silence. It rendered the village, in a sense, “hearing impaired” (Long in Chinese, 聋).

“In the past, we had a stone here that was shaped like a dragon flying up to heaven. It’s how our village got the name ‘Stone Dragon’. Unfortunately, the stone later shattered.”(a native villager, 70s)

“On the hillside, there was a stone rooster and a stone hen. Behind the stone hen, there were two stone nests. The stone rooster had a hollow belly, and when the wind blew, it would make a loud sound. However, the stone rooster was later destroyed and doesn’t make that chirping sound anymore.”(a native villager, 80s)

“On the mountain, there was a large stone slab with two openings—one big and one small. That’s the ‘stone’ in the name of our village. At night, the mountains were covered densely with fragrant trees and pines, which were so thick that even moonlight could not penetrate through. If you walked past that large stone slab, you could surprisingly hear people talking, and the voices were from our village. Moreover, if you were walking on the mountain path and shouted towards that stone, all 18 households in the village at that time (when I was a child) could hear you loud and clear. One day, two brothers came to the village to visit their relatives for a feast. After getting drunk, they damaged the large stone slab on the mountain.”(a native villager, 70s)

In rural tourism, place names become central instruments in place branding strategies, where local folklore is often framed within romanticised pastoral discourses. A deliberate renaming initiative was involved in the branding strategies for Shilong Village, undertaken by the developmentalist configuration. The village’s name was changed from “石聋” (Shilong, with 聋 meaning ‘deafness’) to “石龙” (also pronounced Shilong, but with 龙 meaning ‘Loong’, auspicious Chinese dragon). This purposeful strategy exchanged a name previously associated with negative, pathological connotations for a new one connoted positive cultural symbolism, thereby aligning the toponym with commercial objectives.

The CEO of the design company proposed the renaming idea to the local government and the state-owned tourism enterprise. “The original name of the village was ‘Long’, which means deafness,” he began, recounting a local story about the broken stone. “The decision to change the name from ‘Long (聋 in Chinese, meaning deafness)’ to ‘Long (龙 in Chinese, meaning Loong, Chinese dragon)’ was made for commercial reasons. Loong symbolises prosperity and good fortune, while deafness denotes a pathological condition, which is not positive for business. When people look for leisure, a name meaning ‘deafness’ doesn’t sound healthy. That’s why it had to be changed.” The CEO explained the reason behind the proposal.(The CEO of the design company, 40s)

Toponyms can function as tourist attractions due to their extraordinary properties and their broader associations within popular culture (Light, 2017). In the case of Shilong, the original name carried negative representations. Whereas the new name “Loong”—a spiritual and cultural symbol in Chinese culture representing prosperity and good luck—is considered a form of symbolic capital that can be converted into economic value (Rose-Redwood et al., 2019). This strategy was captured by a local official’s comment on the necessity of renaming. “If this village develops tourism industries, then the name should be changed, just as a nearby village was renamed from ‘Ponor’ to ‘Ten thousand lucks’.” That exemplifies the potent link between toponymy and place branding in tourism, where names are strategically tied to a marketable “sense of place”. However, renaming a place has been criticised by urban geographers within the field of toponymic commodification (Kearns & Lewis, 2019; Rose-Redwood et al., 2019). This neoliberal spatial practice transforms local identity into commodified capital. In Shilong Village, however, most residents desired the renaming, perceiving it not as a loss of identity, but as a tangible opportunity for poverty alleviation.

The name of a place is deeply imbued with personal and collective meaning, reflecting how people understand, present, and perceive a place and how the place is promoted and communicated in the tourism industry. The renaming of Shilong proceeded with the agreement of all stakeholders. However, two historical documents were discovered by the author, meticulously recording the village’s name as “Shilong” (石陇 in Chinese, meaning stone field). This name accurately reflects its karst terrain, with numerous rocky formations hidden deep within the mountains.

4.3. Programme Development

The branding strategy was operationalised through two successive projects. In early September 2016, the Fruit Orchard Project was initiated, aiming to replace subsistence corn farming with commercial fruit production. The local government invested 474,000 yuan (USD 119,000) to rejuvenate existing but underproductive loquat trees—originally planted from the earlier Grain for Green Programme in 2010—and to install a supporting water distribution system in the orchards. Subsequently, training for orchard management was organised by officials in the County Forestry Bureau and technicians hired by the County Poverty Alleviation Office.

Following the Fruit Orchard Project, the Rural Wellbeing Tourism Project was initiated in July 2017 by S Ltd., making a significant scaling-up of investment with 14 million yuan (USD 3 million). The project received crucial support from the local government in the form of land rights readjustment, converting 9.67 mu (1.59 acres) of arable land from 33 households into construction land. This project’s comprehensive aims were to upgrade rural infrastructure, renovate rural residences, construct hotel facilities, and develop well-equipped tourist services. These interventions were designed to capitalise on the unique character of this rural place, especially its cultural heritage and natural amenities.

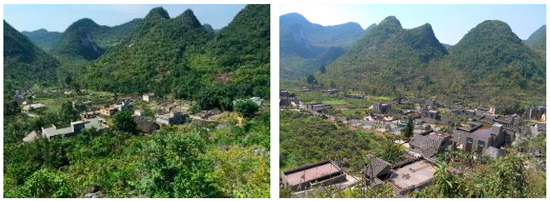

The tourism project formally commenced on 27 August 2017, mobilising all available labour in the community. Within just three months, remarkable progress was witnessed (see Figure 2). The comprehensive upgrade included the renovation of residential buildings, the construction of new hard-surfaced rural roads, and the installation of underground utilities for water, sewage, electricity and telecommunications. New public facilities such as squares, parking lots, public toilets and garbage collection points were also established. Beyond infrastructure, two abandoned traditional residences were converted into Bed & Breakfast hotels, serving as models for inhabitants interested in the hospitality industry. Additional tourism products and services were introduced, including a wine shop, a grocery store, a restaurant, and a craft workshop. Critically, the project facilitated the local inclusion by employing most underprivileged households as cleaners, forest rangers and shop lessors.

Figure 2.

An aerial view of the Shilong Village before and after the programme. Source: photographed by the author, July 2016 and March 2018.

While the powerful exogenous interventions significantly improved local incomes and living conditions, the process inevitably conflicted with the community’s traditional autonomy and rights. Residents’ bargaining power was limited, concerning land deals and planning details. In terms of land transfers and rental agreements, all terms and prices were unilaterally predetermined by the local government and the tourism enterprise, S Ltd., leaving the community and villagers with no room for negotiation. In addition, within the planning process, residents were confined to the role of passive consultees rather than active decision-makers. The core planning and design decisions were determined exclusively by planners, S Ltd. and the town government in their internal meetings. It resulted in a standardised aesthetic vision imposed uniformly across the village.

In response to the imposed renovation plan for rural residences, the top-down approach of place branding provoked resistance among some residents, especially those from relatively prosperous households. These households had previously invested a lot in decorating exterior walls and courtyards with their imaginations and cognitions of modernity and development, such as Roman columns and colourful ceramic wall tiles. However, exterior walls of rural residences would be varnished with grey paint finish, incorporating natural straw and quartz to conform to the image of rurality among planners (see Figure 3). Despite the resistance rooted in their pragmatic worldview, residents ultimately conceded to the renovation plan because of the future developmental promises from S Ltd. and the town government.

Figure 3.

The decorated exterior walls and courtyards before and after the programme. Source: photographed by the author, July 2016 and March 2018.

The development of the hospitality industry remained stagnant until the summer of 2018, constrained by the limited availability of construction land. In response, S Ltd. rented ten residential houses from villagers to operate the B&B business. However, merely three months after the contracts were signed, construction on a new highway started in the southeastern part of the village. The Wellbeing Tourism Project was suspended for two and a half years until March 2021, when the highway was completed and came into service. During the prolonged suspension, only a few individual tourists arrived. As a result, the family restaurant and the craft workshop did not commence operation.

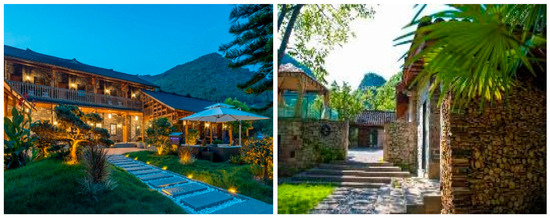

In April 2021, with the increased attention from the local government, S Ltd. resumed and intensified efforts to attract investment. Various social media platforms were utilised to promote and advertise the village of Shilong, encouraging investment from the private sector. Rural elites and urban investors successively began operating a B&B, snack shops, and restaurants (Figure 4). In 2023, the village attracted over 6000 tourists and created a dozen new employment opportunities for local residents. The annual output value of the tourism industry in Shilong reached 2 million yuan (USD 0.5 million).

Figure 4.

The B&B and the restaurant in the village of Shilong. Source: provided by professional managers of the B&B and the restaurant, August 2023.

5. Place-Shaping Beyond the Tourism Development Programme

Due to the limited availability of construction land for tourism development and the disruptive impact of highway construction, the rural tourism programme had been suspended for three years. During the suspension, the place was shaped by residents, just as before the programme’s initial implementation.

5.1. Place-Shaping Before the Programme

The village’s origins trace back approximately two centuries to the Jiaqing Reign of the Qing Dynasty, when people gathered in this remote mountainous area to evade taxation and military service under the Qing Dynasty’s Household Registration System. Subsequent natural disasters and consecutive famines during the Daoguang Reign prompted further waves of migration. This is the historical process of how the village was established in the mountains. For generations, residents’ livelihoods have long relied on small-scale agricultural production within traditional rural communities, where interpersonal relationships between rural inhabitants are defined and regulated based on kinship and geographical relations.

The highly localised social relationships and limited mobility among residents facilitated collective actions on natural resources reservation and management. This is reflected in the village’s forest coverage rate, which currently stands at 50%7. Since 1993, residents have established strict regulations (Box 1) on forest reservation and management, closing hillsides to facilitate afforestation. These community-level initiatives were reinforced by the National Grain for Green Programme (GGP), implemented in the village in 2010 and 2016. The programme intended to convert cultivated land with slopes over 25° to forest by compensating participating households with cash subsidy, free seedlings of loquat trees. Through these efforts, the local ecological environment has been effectively restored. The longstanding practice of collective forest management has also strengthened the awareness of collective property rights among residents. This was notably demonstrated during the reform of collective forest rights in 2011. While the national policy aimed to transfer forest use rights from the collective to individual households, residents firmly insisted that their rights should be recognised and confirmed by the community-level rather than allocated to individual households.

Box 1. The treaty of closing hillsides to facilitate afforestation 11 July 1993.

Since the Reform and Opening Up, our motherland has grown increasingly prosperous, and the people’s livelihoods have continued to improve. In accordance with the relevant documents and instructions of the CPC Central Committee, the importance of afforestation is deeply rooted in every citizen’s mind. People [in the village of Shilong] actively discussed it and prepared to close hillsides and facilitate afforestation. Based on collective consensus, the hill was sealed, and the treaty was made as follows:

- The enclosed hills include Spring Mountain, Golden Lion Mountain, Stone Dragon Mountain, and Flower Mountain.

- Several households manage a hill separately, prohibiting anyone from entering the sealed forest to cut or collect firewood. If anyone is found, he or she shall be fined 30.00 yuan, and 50 seedlings will be planted.

- If anyone is found to enter the sealed forest and cut down trees arbitrarily, each person shall be fined 30.00 yuan, and 200 saplings shall be planted.

Source: provided by the last village secretary, translated by the author.

The consciousness of collective ownership and forest conservation is embedded in the local folk beliefs. The local residents established temples and monuments for an old osmanthus tree, mountains, and the land. Among these, Spring Mountain holds particular significance as a sacred site for the community. Annually, on the date of Lichun—the beginning of spring in the traditional Chinese Calendar—the entire village gathers on Spring Mountain to conduct an animal sacrifice ceremony and feasts together, honouring the mountain deity and praying for good weather and harvest. The role of cultural practices, beliefs and customs in natural resources conservation and management has been acknowledged widely (Huang et al., 2020; Yuan & Liu, 2009).

The well-preserved natural and cultural landscape in the village has been shaped by the local community and state institutional arrangements. It then formed the essential foundation for the introduction of the rural tourism programme.

5.2. Place-Shaping During the Suspension of the Programme

The Wellbeing Tourism Project initially generated substantial physical transformation in the village, such as renovated rural residences and improved infrastructure. However, the provincial highway construction led to the suspension of the project for approximately two and a half years.

Simultaneously, the agricultural sector demonstrated remarkable progress. The loquat harvest yielded unprecedented quantity and quality in 2018. Farmers have acquired knowledge in organic production and sustainable farming, including fertilising, irrigating, pruning, and fruit-bagging. In the first harvest season, the village collectively generated over 300,000 yuan (USD 72,000) from loquat sales. Farm household incomes increased significantly, ranging from several thousand to more than 20,000 yuan (USD 5000).

The transition from traditional subsistence crops to commercial fruit cultivation has changed farmers’ livelihood strategies and patterns. Driven by the significant economic advantages of the loquat in subsequent years, farmers successively expanded their orchards. Corn, which used to be the food crop for self-consumption and the fodder crop for domesticated animals, has been successfully replaced by loquat trees across cultivated land. Therefore, rural households’ expenditure on commercial food and fodder has increased, and correspondingly, livestock numbers have declined. Some households have adapted by intercropping sweet potatoes beneath loquat trees as an alternative staple food crop. The livelihood pattern of “production for use” in self-sufficiency agriculture has been replaced by the logic of “production for exchange”.

The income from loquats is better than what we earn from corn. There are more than 30 loquat trees per mu, and each tree produces around 50 to 60 kg. The selling price ranges from 5 to 18 yuan per kilogram, so the income per mu could be exceed 10,000 yuan. We couldn’t earn anything when we planted corn, considering the cost of fertilisers, seeds, and labour. But now that we no longer grow corn, we can’t raise pigs anymore.(a farmer, 60s)

Apart from transformed livelihood strategies, local residents have shaped their own place in the realm of branding. While the new square is conspicuous to external actors because of its location and decoration, it is barely embraced in residents’ daily life, due to exposure to the valley wind and intense sunlight. Unexpectedly, residents have instead exploited the parking lot as their primary social space. Despite its intended function for parking tourist vehicles, this place is now utilised for daily chatting, group dancing and singing. During harvest seasons, farmers sell loquat fruits in the parking lot to individual tourists. The adaptive reuse of place demonstrates how residents’ subjective agency has gradually emerged through their daily use and creative process of place.

During the suspension of the programme, village cadres and privileged residents maintained high expectations for tourism development. Several households’ incomes have significantly increased through operating a wine shop, grocery stores, especially the house lessors who leased spare rooms to the highway construction teams or entire houses to S Ltd. Two younger households used rental earnings to purchase urban apartments and relocated to the city. The underprivileged residents also benefited from the tourism programme as loquat farmers, cleaners, and forest rangers. However, many believed the programme would be terminated. They perceived the highway construction through the mountains as potentially disruptive to the landscape. This concern is shared by numerous other residents.

6. Place Branding and Place-Shaping After the Programme

After the local government and S Ltd. gradually withdrew from the tourism programme and related operations, branding strategies gradually integrated with the process of place-shaping through the recruitment of multiple actors, the reinterpretation of place image, and the reconfiguration of resources. Rather than claiming the end of place branding, rural tourism development in Shilong Village has been reconfigured to a more complex, multi-stakeholder endeavour, involving the local government, the catering company, professional managers, and inhabitants. The local government and S Ltd. have undergone a passive withdrawal from their dominant positions in the power structure, largely due to constrained fiscal capacity following the COVID-19 pandemic and the broader context of public financial retrenchment. In response, the local government and S Ltd. have shifted their engagement to the digital promotion instead of further large-scale investment. To promote loquat sales and tourism development, they released promotional materials on various online platforms, emphasising natural and cultural heritage in the village.

Concurrently, a private catering company and several elite residents began operating small-scale tourism businesses in the village. The restaurant and B&B in the village have employed professional managers to optimise their commercial performance. With the help of managers, local villagers have also participated in the production and dissemination of promotional video content. Most residents now demonstrate familiarity with social media and travel applications, contributing to expanding the digital image of the place. Consequently, promotional content depicting the village as a beautiful, peaceful, and resource-rich but undiscovered destination is circulating across digital networks.

As the programme’s direct influence waned, the autonomy has progressively returned to the community. Local residents reclaimed their inherent rights to participate in the shaping of their own place. After the expiration of housing leasing contracts with S Ltd., residents intend to regain the use rights of their houses to operate restaurants and B&Bs independently. Agricultural production is undergoing a strategic shift as farmers reintroduce corn within loquat orchards to satisfy food self-sufficiency and revive livestock rearing. The resultant growth in small-scale pig production not only strengthens local food security but also plays an important socio-cultural role of livestock in traditional festival celebrations. Furthermore, residents collectively allocated the compensation funds from the highway construction to construct roads leading to the mountains, simultaneously facilitating rituals of mountain worship and orchard management. Tourism development is also being considered as another reason by village cadres.

“The compensation from the highway construction was 3000 yuan per person, which would be spent in just a few months if distributed. We discussed and decided to invest this money in road construction as a long-term asset. This road leading to our ‘Mother Mountain’ is not only beneficial for the harvesting and transportation of loquats but also for future tourism development.”(a village cadre, 50s)

The existing cultural activities in Shilong Village, such as mountain deity worship and the long table banquet, have received recognition from the town government and operational support from the catering company. On 16 April 2023, a Loquat Festival was organised by the town government and the catering company, attracting thousands of urban tourists (Figure 5). The event programme extended beyond agricultural activities like fruit picking and sales to incorporate rural markets, harvest rituals, and communal feasting. In the process, these traditions are being strategically reinterpreted and reconfigured to align with contemporary tourism frameworks. This initiative significantly strengthened cultural identity and fostered social integration within the community.

Figure 5.

The Loquat Festival in the village of Shilong. Source: local news media.

7. Conclusions

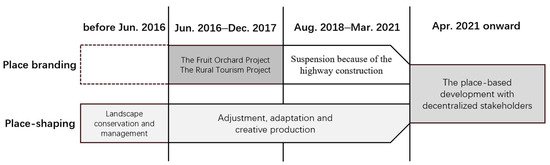

This study analyses the rural tourism programme in Shilong Village through the conceptual lenses of place branding and place-shaping, examining the evolving practices and perceptions of diverse stakeholders in the process of tourism programming and beyond (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The process of tourism programming and beyond in the concepts of place branding and place-shaping.

Place branding is widely acknowledged as a powerful political instrument in public management (Kavaratzis, 2012; Martínez, 2016), facilitating rural development through the commodification of local resources. In this case, place branding essentially functioned as an administrative and capital-led development intervention, prioritising symbolic and visual strategies. The rural place was abstracted as a developmental landscape that could ideally satisfy the economic values, cultural connotation, amenity and ecological functions, and the national political mandates for poverty alleviation and rural revitalisation. Although multiple stakeholders are involved in place branding, local authorities and the exogenous investor were dominant over programme implementation. Bruckmeier and Tovey (2016) report similar elitist development approaches in rural development programmes in Germany, Greece and Denmark.

Although this approach proved effective in rapidly changing the physical landscape of place and improving publicity and promotion, it generated a place lacking in inclusiveness and authenticity, ultimately leading to a brand which is alien to the place (Kavaratzis, 2012). With such an exogenous, top-down approach, stakeholders’ participation and involvement remain insufficient to achieve an inclusive and authentic place brand. Rural residents were almost excluded from the branding decisions of their own place.

During the suspension of the rural tourism programme, the place was shaped by residents, just as before the programme’s initial implementation. Rural residents’ agency revealed through their daily practices and creative adaptations. Compared with the branding practice, the village is a lived place in place-shaping, characterised by rich and complex practices and perceptions in the community. The central role of residents as the principal stakeholders has been asserted in the literature (Kavaratzis, 2012; Rebelo et al., 2020), not merely because of their connection to the place identity (Martínez, 2016), but because residents are the legitimate owners of the place and the creators of local sociocultural assets. Therefore, enabling resident self-representation and active engagement in tourism decision-making (Scheyvens & Biddulph, 2018) is indispensable to achieving sustainable and inclusive development.

After the rural tourism programme, the dominant developmental configuration retreated to the backseat role. Branding strategies gradually integrated with the process of place-shaping through the recruitment of multiple actors, the reinterpretation of place image, and the reconfiguration of resources. Mutually understanding, learning and beneficial relationships between different stakeholders have been promoted. This evolving approach demonstrates how branding strategies can become integrated with the process of place-shaping to achieve place-based development. Ultimately, integration manifests as the emergence of a new, hybrid place-based strategy enabling a development approach that is both competitively positioned and socially sustainable. It enables all stakeholders, especially residents, to collaboratively drive long-term and sustainable development based on the complexities and fluid meaning of the place (Rebelo et al., 2020).

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that sustainable rural tourism development requires integrating place branding strategies with the place-shaping process. While the administrative and financial support from powerful developmental configurations was required to promote the place branding, the top-down approach led to a brand alien to the place. In contrast, residents and multiple stakeholders have shaped a living place through rich and complex practices and perceptions beyond the programme. It entails an integration where elements from the place branding and place-shaping are recruited, reinterpreted, and reconfigured, if a mutually understanding, learning and beneficial relationship is established without central authority domination. Theoretically, this study advances the integration of place branding and place-shaping by identifying their conceptual differentiations and prerequisite conditions. The ethnographic case study demonstrates how the rural tourism programme evolves from exogenous intervention to neo-endogenous development. The identification of conditions that enable the transition offers valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers. Policies should address the tension between necessary exogenous intervention in development phases and the systematic cultivation of endogenous capacity. It required explicit plans for the gradual transfer of decision-making authority to local communities, while emphasising shared interests and values to form common visions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.S. and T.T.; methodology, T.T.; investigation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualisation, T.T.; supervision, S.S.; funding acquisition, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China, grant number 22YJC840027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the Science Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University and the provisions of its Charter (https://fzc.hzau.edu.cn/info/1041/3010.htm).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express their sincere gratitude to Reviewers for taking their time and effort to review this manuscript. All valuable comments and suggestions helped a lot to improve the manuscript. Sincere thanks are extended to the local government and residents for their warm welcome and for generously sharing their experiences and perceptions, which were crucial to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | de Sardan (2005) gives the name ‘developmentalist configuration’ to the essentially cosmopolitan world of experts, bureaucrats, NGO personnel, researchers, technicians, project chiefs and field agents, who make a living, so to speak, out of developing other people, and who, to this end, mobilize and manage a considerable amount of material and symbolic resources. |

| 2 | The national poverty line is annual per capita income of RMB3026 in 2016, equivalent to $2.2 per day (PPP). |

| 3 | Purchasing power parities (PPP) between Chinese Yuan and US dollar is 3.989 in 2016, according to the data in data.oecd.org. |

| 4 | The administrative divisions of China have four levels: the provincial, prefectural, county and township level. The basic level autonomy serves as an organizational division and does not belong to a level of government, which named as communities in urban areas or villages in rural areas. |

| 5 | ‘Moderately prosperous’ is a term borrowed from Confucian philosophy by Deng Xiaoping after he launched the Reform and Opening-up in China in 1979. It is used to describe a society in which people’s basic living needs could be met. There are ten criteria have been set out, including per capita incomes, Engel coefficient index, habitable area, the urbanization ratio, enrolment rate, doctors per thousand. |

| 6 | Shi (石) is stone, Long (聋) is deafness in Chinese. This name means a village that couldn’t hear the voice from outside. |

| 7 | The village’s total area is 1.2 square kilometres, and the forest cover of the land area is 895 mu (0.6 square kilometres). |

References

- Andersson, I. (2016). ‘Green cities’ going greener? Local environmental policy-making and place branding in the ‘Greenest City in Europe’. European Planning Studies, 24(6), 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisen, M., Terlouw, K., & van Gorp, B. (2011). The selective nature of place branding and the layering of spatial identities. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(2), 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmeier, K., & Tovey, H. (2016). Rural sustainable development in the knowledge society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., Thyne, M., & Gnoth, J. (2014). Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum, 41(5), 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, D. (2006). Tourism, consumption and rurality. In C. Paul, M. Terry, & M. Patrick (Eds.), Handbook of rural studies (p. 355). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, P. B., & Gonzalez, P. A. (2012). Industrial heritage and place identity in Spain: From monuments to landscapes. Geographical Review, 102(4), 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sardan, J.-P. O. (2005). Anthropology and development: Understanding contemporary social change. Zed Book. [Google Scholar]

- Dicks, B. (2000). Heritage, place and community. University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J. A. (2007). Tourism, development and poverty reduction in Guizhou and Yunnan. The China Quarterly, 190, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M., Horlings, L., Fort, F., & Vellema, S. (2017). Place branding, embeddedness and endogenous rural development: Four European cases. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(4), 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzenovska, D. (2005). Remaking the nation of Latvia: Anthropological perspectives on nation branding. Place Branding, 1, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, M. (1993). Rural tourism and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 7(2), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmankiewicz, M., & Macken-Walsh, Á. (2016). Government within governance? Polish rural development partnerships through the lens of functional representation. Journal of Rural Studies, 46, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, B. (2012). Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environmental Politics, 21(2), 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulisova, B. (2020). Rural place branding processes: A meta-synthesis. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 17, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. (1997). Justice, nature and the geography of difference. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heeks, R., & Stanforth, C. (2007). Understanding e-Government project trajectories from an actor-network perspective. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(2), 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G. (2016). Connecting people to place: Sustainable place-shaping practices as transformative power. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 20, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G., & Marsden, T. K. (2014). Exploring the “New Rural Paradigm” in Europe: Eco-economic strategies as a counterforce to the global competitiveness agenda. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G., Roep, D., Mathijs, E., & Marsden, T. (2020). Exploring the transformative capacity of place-shaping practices. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Tian, L., Zhou, L., Jin, C., Qian, S., Jim, C. Y., Lin, D., Zhao, L., Minor, J., Coggins, C., & Yang, Y. (2020). Local cultural beliefs and practices promote conservation of large old trees in an ethnic minority region in southwestern China. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 49, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M. (2012). Place branding and the imaginary: The politics of re-imagining a Garden city. Urban Studies, 49(16), 3611–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. (2012). From “necessary evil” to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A., & Bitsani, E. (2013). E-branding of rural tourism in Carinthia, Austria. Tourism, 61(3), 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, R. A., & Lewis, N. (2019). City renaming as brand promotion: Exploring neoliberal projects and community resistance in New Zealand. Urban Geography, 40(6), 870–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y., Chan, E. H. W., & Choy, L. (2017). Village-led land development under state-led institutional arrangements in urbanising China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Studies, 54(7), 1736–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. (2008). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B. S. Turner (Ed.), The new blackwell companion to social theory (3rd ed., pp. 141–158). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. H. J., Wall, G., & Kovacs, J. F. (2015). Creative food clusters and rural development through place branding: Culinary tourism initiatives in Stratford and Muskoka, Ontario, Canada. Journal of Rural Studies, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. (2017). Tourism and toponymy: Commodifying and consuming place names. In New research paradigms in tourism geography (pp. 141–156). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N. (2003). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. (2007). Place-shaping: A shared ambition for the future of local government. The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, N. M. (2016). Towards a network place branding through multiple stakeholders and based on cultural identities: The case of “The Coffee Cultural Landscape” in Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 9(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. (1995). Places and their pasts. History Workshop Journal, 39(1), 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, D., & Warnaby, G. (2014). What’s in a name? Place branding and toponymic commodification. Environment and Planning A, 46(1), 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettepenningen, E., Vandermeulen, V., Van Huylenbroeck, G., Schuermans, N., Van Hecke, E., Messely, L., Dessein, J., & Bourgeois, M. (2012). Exploring synergies between place branding and agricultural development practice. Sociologia Ruralis, 52(4), 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2002). Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition. Elsevier Science & Technology Books. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J. (1998). The spaces of actor-network theory. Geoforum, 29(4), 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi, J. C. (1992). Fiscal reform and the economic foundations of local state corporatism in China. World Politics, 45(1), 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.-S. (2008). Reimagining Singapore as a creative nation: The politics of place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N. (2004). Place branding: Evolution, meaning and implications. Place Branding, 1(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbiosi, C. (2016). Place branding performances in tourist local food shops. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, C., Mehmood, A., & Marsden, T. (2020). Co-created visual narratives and inclusive place branding: A socially responsible approach to residents’ participation and engagement. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (2007). Understanding governance: Ten years on. Organization Studies, 28(8), 1243–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P. D., Dupre, K., & Wang, Y. (2021). Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Redwood, R., Vuolteenaho, J., Young, C., & Light, D. (2019). Naming rights, place branding, and the tumultuous cultural landscapes of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geography, 40(6), 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, N. H., Alon, I., & Fetscherin, M. (2012). The importance of historical Tang dynasty for place branding the contemporary city Xi’an. Journal of Management History, 18(1), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2018). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R., & Roberts, L. (2004). Rural tourism—10 years on. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(3), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M., & Shen, J. (2022). State-led commodification of rural China and the sustainable provision of public goods in question: A case study of Tangjiajia, Nanjing. Journal of Rural Studies, 93, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. (2010). Disintegrated rural development? Neo-endogenous rural development, planning and place-shaping in diffused power contexts. Sociologia Ruralis, 50(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H. (2008). The emergence and development of place marketing’s confused identity. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(9–10), 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Huang, S., & Huang, J. (2018). Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 42(7), 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szondi, G. (2007). The role and challenges of country branding in transition countries: The Central and Eastern European experience. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 3, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M., & Greive, S. (2002). Commodification and creative destruction in the Australian rural landscape: The case of Bridgetown, Western Australia. Australian Geographical Studies, 40(1), 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J. D., Ye, J., & Schneider, S. (2015). Rural development: Actors and practices. In P. Milone, F. Ventura, & J. Ye (Eds.), Constructing a new framework for rural development (pp. 17–30). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Vanolo, A. (2017). City branding. The ghostly politics of representation in globalising cities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorinen, M., & Vos, M. (2013). Challenges in joint place branding in rural regions. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 9(3), 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, S., Madanipour, A., & Schmitt, P. (2022). Place-based development and spatial justice. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J., & Liu, J. (2009). Fengshui forest management by the Buyi ethnic minority in China. Forest Ecology and Management, 257(10), 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Braun, E. (2017). Questioning a “one size fits all” city brand: Developing a branded house strategy for place brand management. Journal of Place Management and Development, 10(3), 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).