Abstract

This paper studies the connection between the 4As factors and tourist satisfaction and evaluates the impact of digital interaction that can either strengthen or weaken the effect of these factors. The study has been conducted in five major tourist destinations in Serbia with 577 tourists as the sample, who used high category hotels. Bayesian statistics allowed a specific evaluation of the effects of predictors and the effects of moderation. The findings reveal that all the 4As determinants are important predictors of tourist satisfaction with attractions and amenities playing the strongest roles. Digital interaction: Digital interactions will become a major mediator of its presence, with an amplification of the effect of ancillary services and accessibility in the case of attractions and amenities, and a dependent effect on the perceptions of authenticity and technological literacy by the tourists. The research is relevant to the theoretical discussion on the impact of digitalization in tourism because it extends the concept of the 4As framework by providing it with a digital aspect. Practical implications show that there is a necessity to introduce a balance between digital and physical aspects of the tourist experience to maximize visitor satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the important sectors that contribute to economic and social development where tourist satisfaction acts as a basic indicator to the success of a tourist destination (Sangpikul, 2018). The formation of tourists’ perceptions and experience are influenced by several factors including attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services, which are known as the 4As framework (Ketut et al., 2024). These elements are crucial in the creation of the destination’s competitive advantage and long-term sustainability in the market (San Martín et al., 2019). Contemporary trends in tourism, however, point to a growing need for the integration of digital technologies, which have a significant impact in defining the way tourists explore, experience, and evaluate destinations (Oviedo-García et al., 2019). Although many studies have proven the significance of physical and infrastructural factors in the satisfaction of tourists, traditional models of satisfaction fall short in the context of accelerated digitalization (Jebbouri et al., 2022; Dziekański et al., 2024). Digital engagement, which includes the usage of smart technologies, social networks, and interactive platforms, has become a key component of the tourism experience as it enables customized services and deeper interaction with destinations (Ge & Chen, 2024). Previous theoretical approaches to tourist satisfaction, such as the Expectancy-Disconfirmation Model (Oliver, 1980) and the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999) were mostly focused on the psychological dimensions of satisfaction, without taking into account the moderating influence of digital behavior. Based on these foundations, this research adds the concept of digital engagement to the existing 4As framework, therefore creating a multidimensional approach to the analysis of the tourist experience.

However, though the topic of digital engagement has undergone intense study, in most works it has been considered an isolated factor. It is not widely researched yet how it can moderate the effect on tourist satisfaction of basic destination attributes (Muskat et al., 2019). In addition, existing theoretical models, such as the Smart Tourism Framework (Gretzel et al., 2015), the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989) and the Digital Experience Theory (DEM; Law & Sun, 2012), provide solid grounds for understanding digital behavior, but are seldom empirically tested within the context of integration with the 4As framework. It is in this direction that this research broadens the previously existing foundation of theory, providing a conceptual synthesis of traditional elements of the tourist experience and modern digital interactions.

The research gap is especially prominent in Serbia, where tourism is playing an increasingly important role in the economy’s development, but is challenged in terms of innovation and digitalization (Savić & Pavlović, 2018). Despite the rich cultural and natural heritage, the Serbian tourism sector is still mostly based on traditional models of tourism visitor attraction, while digital technologies application is uneven and confined to some tourist destinations (Vujadinović et al., 2023). This imbalance illustrates the larger digital division that is typical of the post-transition economies of Southeast Europe, where infrastructure development is frequently outpacing institutional adaptation and the level of digital literacy. As such, Serbia is a valuable context to study the role of digital engagement when it comes to enhancing the competitiveness of destinations still in transition between traditional and smart tourism (Cimbaljević et al., 2019). At the same time, national strategic documents for the development of tourism in Serbia highlight the importance of the digital transformation as the pillar of sustainable growth, but the practical application is fragmented and uneven among the regions (Vukelić et al., 2023). Understanding these asymmetries is important in understanding the mechanisms via which digital engagement can mediate the relationship between core destination attributes and tourist satisfaction. This fills the empirical and theoretical gap in the existing literature and contributes to the validation of the 4As framework in the context of developing market conditions under implications relevant for other transition tourism systems in the Balkans and beyond.

The general purpose of the research is to investigate the moderating effect of digital engagement in the 4As factors–tourist satisfaction relationship in Serbian tourist destinations. By analyzing the interdependence of traditional elements of the tourist experience and digital technologies, the research aims at a deeper understanding of the modern factors that influence the perceptions and the satisfaction of tourists. The obtained findings will contribute to the academic literature in terms of broadening the 4As framework by incorporating digital engagement and explaining its effect on the tourist’s satisfaction. On the practical side, the results will have benefits to those involved with tourism policy-making and destination management in Serbia, with recommendations for the optimization of digital strategies and the competitiveness of the destinations. A better understanding of the role of digital engagement can be a part of the process of developing innovative approaches in destination management and the improvement of the whole tourist experience, thereby fostering the long-term sustainability and growth of the tourist sector.

The context of Serbia offers the unique opportunity to examine this relationship in a market in transition, where digital maturity, infrastructural development and visitor expectations are uneven. The methodological contribution of this paper lies in the application of the idea of Bayesian statistical modeling, which helps to increase precision in the determination of the moderating effects and the range of modern analytical methods used in tourism research.

2. Theoretical Background

Tourist satisfaction has been well-documented as a multidimensional construct and one of the most reliable indicators of the success of any destination, and it has a direct impact on its competitiveness, reputation, and visitor loyalty (Park et al., 2018; Chernyshev et al., 2023; Van Phung et al., 2024). Prior studies make a distinction between objective destination attributes, such as infrastructure, accessibility, quality of services, and subjective experiential factors, such as emotional attachment, authenticity, and perceived value (Virkar & Mallya, 2018; Papadopoulou et al., 2023; Huete Alcocer & López Ruiz, 2020; Biswas et al., 2021). However, the relationship between these dimensions is not uniform across contexts and the level of satisfaction is often determined by a combination of the physical, emotional, and cultural, rather than isolated effects. Accessibility and infrastructure have been identified, on numerous occasions, as key enablers of destination satisfaction. Studies point out that well-developed transportation networks, efficient transit systems, and good signage contribute to more positive perceptions of comfort, convenience, and safety (Breiby & Slåtten, 2018; Govindarajo & Khen, 2020). Eid et al. (2019) further contend that the accessibility of information and responsiveness of services contribute equally to overall travel experience and therefore it is suggested that the accessibility should be understood as both physical and informational. Nevertheless, most of these studies take a functionalist perspective on accessibility and do not address its psychological and symbolic aspects, such as the role of digital mobility and access to online information and how they shape the perceived accessibility in the digital age among tourists.

Beyond the physical features, emotional and cultural experiences play a fundamental role in creating satisfaction. Al-Msallam (2020) shows the significance of emotional attachment produced during a visit to the perceived value and behavioral intentions. Similarly, Biswas et al. (2021) believe that destinations that encourage emotional bonds through authentic encounters can lead to increased tourist loyalty. Cultural authenticity also adds further richness to such a relationship: Tian et al. (2020) indicate that people who view destinations as authentic are more satisfied and hold more positive intention to recommend, and Jeong and Kim (2020) highlight the mediating role of the quality of cultural events in increasing destination image. Yet, these studies tend to consider emotions and authenticity as static products instead of dynamic processes affected by interaction and feedback and these dimensions are increasingly shaped by digital environments.

Recent scholarship introduces the digital sphere as an important factor in redefining the ways of forming and maintaining satisfaction. Suhartanto (2018) discusses the influence of digital marketing and user-generated content on destination perception, whereas Seetanah et al. (2020) observe that communications online directly improve satisfaction. However, the integration of digital engagement, defined as active interaction with digital tools, platforms, and communities, is conceptually fragmented. Although Torabi et al. (2022) recognize the potential of digital engagement in creating long-term loyalty, they do not investigate the moderating role of digital engagement in the relationship between destination attributes and satisfaction. This gap highlights the importance of having a comprehensive model that brings together traditional determinants of satisfaction (the 4As framework) and more modern dimensions of digital behavior, providing a more holistic picture of the modern tourist experience.

The tourist experience and its relation to satisfaction can still be measured by one of the most widely used frameworks, the 4As model (attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services). While its comprehensiveness has been established through many empirical studies, scholars are more frequently noticing its conceptual rigidity and the lack of analytical adaptability to new forms of tourism (Echtner, 2002; Karim et al., 2021; Hanim et al., 2023). Attractions, as the first and often dominant component of the model, have long been considered as one of the main motivators with regard to destination choice and destination satisfaction (Echtner, 2002). However, Wang et al. (2009) show that this relation is not uniform because while natural attractions promote deeper emotional connections and long-term loyalty, cultural attractions produce more fluctuating levels of satisfaction depending on visitor expectations and the interpretive context. This implies that standardized constructs within the 4As model usually fail to reflect the subjective and experiential diversity of tourists’ perceptions. Karim et al. (2021), studying Central Karakoram National Park, reiterate the importance of attractions but highlight that the effect of attractions is conditional on complementary factors like infrastructure, accessibility, and promotion of destination. Similarly, Hanim et al. (2023) point out that the sustainability and maintenance of attractions have a direct impact on satisfaction, particularly if there is a mismatch between the expectations of visitors, created through marketing, and the real experience at the site. These findings taken together suggest the interdependence of the 4As dimensions and that the mere presence of attractions would not necessarily lead to satisfaction in the absence of functional support systems, adequate services, and consistent destination management. Yet, one important gap exists: the traditional model of the 4As primarily addresses tangible and infrastructural determinants, neglecting the increasingly influential role that digital environments play in how tourists perceive, access, and evaluate tourist attractions. Modern travelers interact with destinations via online platforms, social media, and digital storytelling long before and after they physically visit the destination, dimensions not originally part of the 4As model. Therefore, a further expansion of the framework to include the digital engagement as a mediating or moderating element provides a better representation of modern tourist behavioral and satisfaction mechanisms.

H1:

Attractions significantly influence tourist satisfaction.

Accessibility has traditionally been considered a critical factor in the level of satisfaction of tourists with their trip, and is a measure of the physical connectivity, ease of mobility, and functionality of a given destination. However, its role is by no means universal or straightforward. Dumitrașcu et al. (2023) show that insufficient transportation networks and limited road facilities may significantly lower the level of satisfaction owing to lack of comfort and convenience. Yet, Utomo et al. (2024) warn that the development of infrastructure alone does not always bring in more visitors or ensure satisfaction if there is an absence of complementary amenities and appealing services at the destination. This observation contests the assumption, often built into the 4As framework, that accessibility will help to enhance the tourist experience in a similar way in different cases. Ismail and Rohman (2019) provide empirical evidence that destinations that have well-organized public transportation, efficient transit systems, and clearly marked tourist routes tend to receive higher satisfaction ratings. On the contrary, Yusuf et al. (2024) noticed that there is a paradox as accessibility acts as an instrumental factor to attract first-time visitors but it lacks the ability of retaining loyalty, unless it is complemented with qualitative dimensions such as hospitality, service experience, and perceived safety. This finding emphasizes the fact that accessibility can not be considered an objective or infrastructural factor, but rather is a subjective judgment of ease, comfort, and perceived value. Thus, although the previous research supports the positive relationship between accessibility and satisfaction, the intensity of this relationship is related to the psychological experience of tourists and the interaction between the physical and experiential aspects of travel. Taking such nuances into account, this study hypothesizes that:

H2:

Accessibility positively influences tourist satisfaction.

Amenities are one of the basic dimensions in the 4As model, and they include facilities and services that determine the comfort, convenience, and overall quality of the tourist experience. However, their impact on tourist satisfaction does not seem to be linear or universal. Wulandari et al. (2024) emphasize that, in agritourism destinations, amenities contribute greatly to the satisfaction of tourists only if they are carefully adapted to the wishes and expectations of certain groups of people. This finding challenges the common notion of the universality of the 4As model by suggesting that the impact of amenities is highly contingent on the type of destination and profile of visitors. Marwani et al. (2023) further argue that the modernization of amenities can be ambivalent in their outcomes. While the better infrastructure may appeal to a wider range of people, over-urbanization may destroy the authenticity and defeat the satisfaction of tourists seeking authentic and traditional experiences. This is especially apparent in rural and ecotourism contexts where a lack of contextual sensitivity in amenity design may result in a lack of perceived authenticity and emotional connection to the destination. On the other hand, Astuti and Dewi (2022) reveal that even good services do not necessarily translate into satisfaction if marketing communication bears inflated expectations that the destination is not able to meet. This points to a recurrent limitation of the 4As framework: the conceptualization of amenities focuses mainly on the tangible dimension of service quality and ignores the perceptual and the experiential dimension, which depend on tourist expectations and destination image. Consequently, the amenities versus satisfaction interaction needs to be considered as both functional and psychological, combining service quality and authenticity and expectation management. In light of the reviewed literature, this study posits that:

H3:

The quality and diversity of tourist amenities positively influence tourist satisfaction.

Despite the fact that ancillary services may be regarded as peripheral to the 4As framework, they are fundamental in relation to the overall tourist satisfaction and overall destination image. These services, including guided tours, information centers, emergency services, and translation services, form the connective tissue that complements and bolsters other destination features. However, they have often been underrated in theoretical models of tourist satisfaction. Pai et al. (2020) find that well-organized ancillary services, especially guided tours and accessible information centers, significantly raise satisfaction levels for first-time visitors by enhancing their orientation and lowering uncertainty. Nevertheless, as we see from Siregar and Siregar (2022), the availability of such services does not mean satisfaction, efficiency, accessibility, and responsiveness are the characteristics of their actual effectiveness. This does not only mean that destinations have to be able to offer ancillary services but that they also have to integrate them into a coherent and user-friendly systems. Car et al. (2018) take this forward and address an increasingly incompatible overlap of the design of ancillary services as traditionally executed and contemporary digital dynamics. When tourists cannot access maps, guides, or booking systems via digital platforms, even high-quality services can be perceived as out of date or inefficient. These findings show a major limitation of the 4As model which considers ancillary services as fixed, operational entities rather than as adaptive factors in a digitalized tourism ecosystem. Recent studies have pointed to the key of the success of ancillary services being the combination of functionality and interactivity. Efficient digital integration in the form of real-time assistance apps, multilingual chatbots, and GPS-based tourist navigation can transform these traditionally dormant services into dynamic touchpoints that can serve to replenish tourist trust and comfort. Moreover, the human aspect is still important: over-automation can reduce the authenticity and the empathy present with direct contact between humans (Azis et al., 2020; Seseli et al., 2023). Therefore, a hybrid model with innovation around technology and with personalized assistance seems to be the most efficient way to increase satisfaction. While ancillary services used to be on the periphery of the satisfaction systems, currently the evidence is such that they are strategically important. As long as they are accessible and have digital connection, they can have a positive impact on the perception of safety and ease and improved quality of experience for the tourists.

H4:

Well-developed ancillary services increase tourist satisfaction.

Considering the relationships derived from the traditional 4As model, it can be clearly seen that tourist satisfaction is no longer determined by physical, infrastructural, or service-related characteristics. Given the increased penetration of digital technologies into all aspects of the tourism experience, digital engagement may be considered a higher order driver that mediates the translation of attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services into perceived value and satisfaction. This evolution requires a more in-depth investigation of the moderator role of digital interaction, since technological interaction becomes an increasing key decision-maker in the quality, personalisation, and authenticity of modern touristic experiences.

Furthermore, digitalization is increasingly changing the nature of the tourist experience, being not only a direct determinant of satisfaction, but also a moderator changing the relationship between traditional destination attributes, attraction, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services—and satisfaction. Within the Smart Tourism Framework (Gretzel et al., 2015), digital technologies are defined as enablers of value co-creation, relating to the experience of interacting with tourism destinations facilitated through personalized, real-time, and data-driven decision-making processes. Similarly, the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989) reveals that tourists’ attitudes towards digital technologies, such as perceived usefulness and ease of use, play significant roles in shaping the behavioral engagement and the level of their satisfaction. Theoretical linkage is supported by empirical research. Mayer et al. (2023) and Yuksel et al. (2024) show how digital technologies can improve perceived destination quality, improve accessibility, and also personalize service experiences. For instance, augmented and virtual reality, interactive maps, and user-generated content are used to give tourists the chance to visit attractions before physically going there, thus increasing familiarity and decreasing uncertainty (Sonuç & Süer, 2023; Rui et al., 2024). Nonetheless, Nasir et al. (2020) warn against the excessive mediation through digital technologies as it might lose a sense of authenticity and diminish the emotional experience between tourists and destinations, similar to what is found in the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), where the manufactured experience loses its spontaneity and authenticity. Accessibility, which traditionally referred to physical infrastructure, has moved into the virtual world. Su et al. (2018) determine that digital mapping, real-time transport information, and navigation applications are important for improving perceptions of accessibility. However, as pointed out by Seseli et al. (2023), differential digital literacy levels are likely to exclude certain visitor segments, diminishing inclusiveness and satisfaction. At the same time, the function of amenities is being reconceptualized through smart technologies: Yuksel et al. (2024) indicate that Smart Tourism Technology Experiences (STTEs) increase satisfaction through personalization and forecasting, while Castillo Canalejo and Jimber del Río (2018) suggest that excessive use of algorithmic suggestions limits serendipity and local interaction. Digital transformation is also beneficial for ancillary services. According to Azis et al. (2020) and Rui et al. (2024), digital guides and interactive information systems contribute to learning and orientation; however, according to Seseli et al. (2023), an overload of automation can compromise the human service exchange of empathy and naturalness. Finally, the quality of digitalization is shown by being part of hybrid models that combine technological innovation and interpersonal connection and is in line with the Digital Experience Theory (Huang et al., 2017), where there is a synergy between human and technological touchpoints that leads to satisfaction. From a theoretical perspective, these results together suggest that digital engagement acts as a moderator of the effect of the 4As factors by making them stronger (e.g., attraction visibility, informational accessibility, and service efficiency), as well as weaker (e.g., uncertainty, lack of personalization). However, when poorly managed, digitalization can also introduce experiential detachment, thereby weakening these relationships. Accordingly, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H5:

Digital engagement moderates the impact of the 4As factors on tourist satisfaction.

Despite a large body of empirical research, there is limited engagement between theoretical models of satisfaction and contemporary concepts of digital engagement. There is a lack of critical integration of classic theories, such as the Expectation–Disapproval Theory and the Experience Economy, with new models, such as TAM and the Smart Tourism Framework, which limits understanding of how digital technologies shape tourist perceptions and loyalty.

An overview of relevant research is presented below, with an emphasis on authors who have dealt with similar topics and variables in the context of tourism and hospitality. Based on their findings, the research constructs used in this paper were designed and modified. The statements in the questionnaire were not adopted identically, but were adapted to the specific context of the research, the language of the respondents, and the objectives of the study, while maintaining the theoretical framework and logic of measurement from previous works. This approach allowed the instrument to maintain scientific validity, while at the same time reflecting real conditions in the analyzed tourist environment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of previous studies related to the applied constructs and analytical methods.

While previous studies offer empirical findings that are helpful to understand the context of destination attributes and understand their effects on tourist satisfaction and digital engagement, the theoretical basis between destination attributes, tourist satisfaction, and digital engagement is lacking. Early research on tourist satisfaction was largely based on the Expectancy-Disconfirmation Theory (Oliver, 1980) which describes satisfaction as a comparison of expectations and experience. However, this framework does not take into account the dynamic and interactive nature of digital tourists’ behavior which is now at the heart of understanding contemporary consumption in tourism. The Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999) built upon this base and highlighted emotional and sensory engagement but did not incorporate technology and digital interaction as intermediaries to value creation. More recent frameworks, such as the Smart Tourism Framework (Gretzel et al., 2015) and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989), emphasize the importance of digital interaction and its influence on tourists’ perceptions, loyalty, and satisfaction (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2014; Ge & Chen, 2024). However, theoretical connections between digital behavior and the traditional 4As of destination competitiveness are still underdeveloped. The current paper breaks this gap by synthesizing these frameworks into a holistic model that links physical, institutional, and technological parts of the tourist experience.

3. Methodology

The study was carried out in five major cities of Serbia (Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, Kragujevac, and Leskovac) (Figure 1) with a total of 877 valid responses in 900 distributed surveys (high response rate of 97.4%). The sample was made up of tourists staying in 3-, 4-, and 5-star hotels, in order to ensure the representativeness of high category accommodation facilities in these destinations. The research was carried out to analyze the influences of the 4As factors (attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services) on tourist satisfaction with the moderating role of digital engagement. The sample consisted of tourists accommodated in higher categories of hotels (4 and 5 stars) in the most important tourist destinations in Serbia (Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, Kopaonik). This sample structure permits the use of a high degree of data reliability, as the respondents have a relevant experience with a high quality of service. However, this approach is possibly limiting the possibility of generalizing the results to a wider tourist population, especially to tourists staying in lower-class accommodation or using alternative forms of tourism. In future studies, it is recommended to increase the sample to increase the external validity and allow for a more representative assessment of tourist satisfaction for different profiles of tourists. The sample contained both domestic and foreign tourists so there was the opportunity to analyze possible cultural differences in the perception of satisfaction and digital behavior. The proportion of domestic tourists was estimated at around 58.7% and that of international tourists was about 41.3% of the sample. This estimate is a rough reflection of the structure of the tourism traffic in Serbia, although in the official sources there are no data exclusively for the hotel accommodation in the same tourism segment (Perić et al., 2018; Tourism Organization of Serbia, 2025). This same approach enhances the external validity of the results, because comparisons can be made between the various markets for tourism and degrees of digital literacy. Although the reported response rate of 97.4% is statistically high, this was made possible by standardization of procedures and direct access in hotel facilities with completely voluntary and anonymous participation. Interviewer training and pilot testing of the instrument considerably decreased the danger of response bias. Additionally, the validity verification methods were applied (KMO, Bartlett, Cronbach’s alpha, CFA fit indices) that were implemented to verify the internal consistency and representativeness of the sample, hence implying high internal and external validity of the research.

Figure 1.

Research area (Source: Author’s work created in QGIS software, https://qgis.org/).

In order to guarantee a valid data analysis, the distribution of respondents was proportional to the touristic importance and size of each city. A total of (8%) accounted for the response, so it was not only the bigger areas of tourism that were included. The survey was designed and carried out from December 2024 to February 2025 and the primary data collection method was based on structured questionnaires (Appendix A). The surveys were administered in hotel facilities where tourists were staying and the data collection process was performed by trained students of tourism and social sciences that had undergone specialized training in research methodology and interviewing techniques.

This approach assured the standardization of procedures and avoided sources of potential research bias. To ensure the validity and reliability of the instruments used, a pilot study was carried out with 50 respondents so that the questions could be optimized and the research design modified prior to the main study. The questionnaire consisted of closed-ended questions, which can be quantified, and was based on relevant dimensions of the tourist experience, such as hotel service satisfaction, quality of facilities, accessibility, and digital engagement, in order to explore the impact on the tourists’ overall satisfaction. To ensure the representativeness of the sample, the G*Power 3.1.9.7. version, test was used to determine the best sample size when using desired statistical power (power = 0.80), alpha level (a = 0.05), and expected effect size (Cohen d = 0.3) (Goulet-Pelletier & Cousineau, 2018). Based on this analysis, a sample size of N = 700 respondents was considered enough to obtain reliable and statistically significant results; the further increase in the collected responses (N = 877) further enhanced the robustness of the results.

The research was conducted in accordance with the basic ethical principles of social science research and the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the research, and their participation was voluntary and anonymous. No data that could lead to the identification of the respondents were collected, nor were the participants exposed to physical, psychological, or social risk. Since the research was based on an anonymous questionnaire and did not cover sensitive topics, formal ethical approval was not required, but it was conducted in accordance with the highest standards of scientific and research ethics. Potential moral hazard was minimized by ensuring data confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right of the respondents to refuse participation at any time without any consequences.

The socio-demographic analysis of the sample shows that it is balanced in gender distribution with slightly more female respondents. The age distribution has revealed that more than half of the tourists are within the age group of 30–39 years, followed by 18–29 years, with a minimum presence of those above 50 years. Education-wise, the majority of the respondents have a university degree, with a significant portion having a master’s degree, while those with only high school education or a PhD are a smaller proportion. Employment status shows that almost 50% of the participants are in the working population, and a smaller percentage includes self-employed, students, and retired people. The distribution of income shows that the majority of respondents receive between EUR 500 and EUR 1000 per month, a large proportion earns more than EUR 1000, and a relatively smaller income group earns below EUR 500. The results indicate that the group of surveyed tourists mainly belongs to the group of medium income and higher education level, which is consistent with the group of targeted tourists in the higher category hotels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics.

Model and Measurements

The 4As framework is a fairly standard model in tourism research, but it does not have one obvious and sole author. The concept has been designed by several academic studies and practical applications in order to provide a systematic analysis of tourist destinations. Although it is usually credited to Morrison et al. (2013) who introduced the concept into the context of destination management and tourism marketing, its foundations come from previous models of destination competitiveness, notably the Crouch and Ritchie (1999) model, being the basis for the analysis of key success factors of tourist destinations. Morrison’s 4As Model further refined the model and focused on how to use the 4As framework to assess destination attractiveness, focusing on marketing strategies and the competitiveness of destinations. The four key factors of the 4As framework are attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services, all of which are important elements in shaping the tourist experience perception. Attractions are natural, cultural, and entertainment characteristics of the destination; accessibility includes transport links and ease of arrival; amenities and ancillary services include infrastructure, hospitality, and other supporting services that help a tourist’s experience (Xu et al., 2024). Some of the studies have extended this framework in the 5As or 6As models (Esmaeili Mahyari et al., 2024) that include other dimensions like awareness, activities, etc.

In order to fit the model with the current trends in tourism, this research combines tourist satisfaction and digital engagement into the original 4As model. Tourist satisfaction was defined as the level to which visitors’ expectations were met and digital engagement represents the increasing influence of technology on the tourists’ decision-making processes, including online platforms, social media, and interactive digital tools. For each construct, measurement items were adopted and adjusted from the previously validated studies: attractions, accessibility, amenities, and ancillary services from Chen and Chen (2010), Kolar and Zabkar (2010), Ali et al. (2018); digital engagement from and tourist satisfaction from Gajić et al. (2024) (Table 1). Each construct was measured by three to five indicators, giving a total of 23 observed indicators. The three-to-five-item choice for each construct is in line with the psychometric literature recommendations that three items are enough for achieving construct reliability, whereas five items provide greater factorial stability without respondent fatigue (Vyas & Vyas, 2024). Examples of such items are as follows: “The destination has various natural and cultural attractions” (attractions), “Public transport is efficient and available” (accessibility), “The destination has high quality local and international food” (amenities), “The destination is safe and medically supported” (ancillary services), and, “Social media content affected my decision to visit this place” (digital engagement).

All items were scored on a five-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). A five-point Likert scale (1–5) was applied in the research as it provides easier and more definite answers from respondents, particularly in international research where there is a risk of different interpretations of nuances among the larger number of available options. A five-point scale in research within the domain of tourism and hotel management is the most widely used, as this scale score provides high reliability, not too much cognitive load, and a fairly high level of discrimination of the variables (Jebb et al., 2021).

4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, reliability tests, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using SPSS 26.0, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and Bayesian regression analysis was performed using AMOS 26.0 and JASP. This methodological choice allowed for an in-depth evaluation of the reliability and the validity of the measurement instrument, in addition to hypothesis testing within the proposed model (Kyriazos, 2018). Descriptive statistics showed that all indicators had skewness values between −1 and +1, indicating symmetrical distribution of data, while the kurtosis values were between −1.5 and +1.5, proving that there are no significant deviations from the normal distribution (Finch, 2020). Cronbach’s alpha (α) was used to determine the reliability of the constructs, with all the factors above 0.7 indicating high internal consistency in measurement scales (Orçan, 2018).

Also, composite reliability (CR) values were found to be above 0.8, further supporting the reliability of latent variables (Finch, 2020). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to obtain the latent structure of the questionnaire, and the result of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was 0.891, indicating that the sampling adequacy of the factor analysis was high. The test of sphericity by Bartlett (χ2 = 3421.57, p < 0.001) supported significant correlations among variables, and hence, the factor analysis was justified (Marsh et al., 2020). Principal component analysis with varimax rotation showed that all indicators had factor loadings greater than 0.6 explaining convergent validity. A total of 6 factors were extracted, which were in line with the theoretical framework of the study. The six-factor structure discovered is conceptually totally in line with the theoretical model upon which the research was based. The first four factors (attractions, accessibility, amenities, and services) represent the classic dimensions of the 4As framework which describes the physical and functional elements of a tourist destination. The fifth factor, tourist satisfaction, reflects the outcome aspect of the tourist experience, whereas the sixth factor, digital engagement, brings in a modern mediator that explains the impact that technology has on visitor perception and experience. This factor structure is not limited to a statistical outcome, but is a consequence of the theoretical idea that digital engagement is operating as a moderator between the traditional destination attributes and tourist satisfaction, which is coherent with the TAM (Davis, 1989) and Smart Tourism Framework (Gretzel et al., 2015) models. The factors defined in this way ensure the incorporation of classical and digital components of the tourist experience, so that a theoretical consistency between the empirical and conceptual structure of the model is achieved. Following EFA, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted in order to validate the factor structure with model fit indices which suggested a good model fit (χ2/df = 2.91, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.051, RMSEA = 0.047 (Phakiti, 2018)). The results established convergent and discriminant validity with average variance extracted (AVE) values greater than 0.50 and composite reliability (CR) greater than 0.80 to ensure the internal consistency of the constructs (Mia et al., 2019). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to confirm the latent factor structure revealed by exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Whereas EFA had a function in discovering underlying dimensions, CFA confirmed the accuracy of the observed indicators to their latent constructs in the theoretical 4As model. The resulting fit parameters (listed above) provided confirmation of excellent model fit and of factor validity, showing that the items were consistent with their theoretical constructs and that the measurement model was empirically stable for further hypothesis testing. Bayesian statistics were used to estimate the predictive effects of the 4As factors and digital engagement on tourist satisfaction with weakly informative priors as this reduces subjectivity when estimating parameters (Lecerf & Canivez, 2018). Bayesian methods were selected for their capacity to update prior knowledge with new data, effectively be applied to small to moderate samples, and provide greater evidence for effect sizes through Bayes factors (BFs) (Pek & Van Zandt, 2020).

Model Evaluation and Validity

Convergent validity (AVE = 0.678) shows that the latent variables are effective measures of the intended factors as its value is above the 0.5 threshold, in line with standard recommendations (Neufcourt et al., 2018). Discriminant validity (0.742) is confirmed by demonstrating that the factors are sufficiently distinct from one another in order to measure different aspects of the tourist experience. The Posterior Predictive Check (PPC = 0.823) suggests that the model successfully predicts the observed data, and the model’s function is important to the generalizability of the model (Deng et al., 2021). Additionally, the WAIC value (−1192.430) indicates a good model fit with lower WAIC values representing better predictive performance. The LOO-CV value (−1189.876) gives further confidence in the robustness of the model, with a lower value indicating stable predictions. This result, in agreement with WAIC, shows that the model is not overfitted with the sample and is reliable for future research. The Bayesian R2 (0.742) indicates that the model accounts for 74.2% variance in the tourist satisfaction with each other factor, showing a great relationship between predictors and the level of tourist satisfaction. This finding confirms that factors in the model play a key role to accurately predict the level of satisfaction, which is of value for optimizing tourism management strategies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Model validation metrics and fit indices.

Common method bias (CMB) was examined by Harman’s one factor analysis with the highest factor identified not being more than 30% of the total variance, indicating the lack of systematic method bias. In addition, all VIF values were less than 3.3 and Tolerance > 0.3, eliminating multicollinearity and confirming independence of the constructs. Non-response bias was examined by comparing early and late respondents using independent sample t-tests and no statistically significant differences were found (p > 0.05) which shows a negligible effect of this type of bias. Normality bias was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05) and analysis of parameters’ skewness and kurtosis, the values of which were within an acceptable range (from −2 to +2). These results confirm that there is no statistically significant deviation in the data from the normal distribution (Kline, 2023). Selection bias was minimized with stratified sampling according to destination and accommodation category which resulted in spatial and demographic diversity, maximizing the external validity of the results (Heckman, 1979). Social desirability bias was minimized through participant anonymity, neutral question wording, and lack of value judgments in the questionnaire which avoided the tendency for respondents to give socially desirable answers (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Homogeneity bias was further tested using the Levene’s test of equality of variances which revealed no statistically significant differences between groups (p > 0.05), confirming sample homogeneity and measurement stability. Response pattern bias was also analyzed in terms of the median and interquartile range (IQR < 1.2) and shows consistency of responses and no systematic patterns of responding. The combination of these methods demonstrates that the collected data have a high level of reliability, that the statistical error is minimal, and that the interpretation of the results is according to stable and unbiased indicators.

The significance of predictors and moderation effects was assessed using the Bayes Factor (BF) thresholds, where BF > 3 indicates moderate evidence, BF > 10 strong evidence, and the exclusion of zero from the Highest Density Interval (HDI) confirms credibility. Weakly informative prior distributions were applied to ensure that the results were primarily driven by observed data, while maintaining model robustness. Bayes Factors (BFs) were used to evaluate the strength of evidence, with BF > 3 indicating moderate evidence, BF > 10 strong evidence, and BF > 30 very strong evidence. Additionally, the 95% HDI was used to assess parameter credibility—when the HDI did not include zero, the effect was considered credible (Afshar et al., 2020) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prior distributions used for Bayesian estimation.

The results of the sensitivity analysis show that the model coefficients do not change too much with the choice of priors; this reflects the robustness of Bayesian estimates. The coefficient values for attractions, accessibility, amenities, ancillary services, and digital engagement show very small variations for previous types. For instance, we can see in the attractions factor a range of co-efficient values from 0.511 to 0.518, which means that there is a very small fluctuation in the estimation of the effect regardless of the prior used. Similarly, under amenities and ancillary services, the coefficients are in the range of 0.593 to 0.611, whereas for digital engagement, the coefficient values vary between 0.672 and 0.712. These small differences in coefficients validate that the model is stable in the face of different prior distributions guaranteeing robust and reliable results. In addition, digital engagement has the highest variance of priors, with values in the range of 0.672 (Non-Informative) to 0.712 (Optimistic). This may be an indication of its important role for the model as well as its sensitivity to changes in prior distributions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis.

5. Results

The analysis shows differences in the tourist perceptions regarding the various destination dimensions. The attractions were rated quite positively with the best rated dimension being the added value of the additional content to the overall visitor experience (m = 4.44, sd = 0.69), whereas the uniqueness of experiences was rated the lowest (m = 3.14, sd = 0.62), suggesting that more unique attractions are required. This factor is reliable as the internal consistency across items (α > 0.86) is good. Accessibility proved to be one of the most important problems: transport connectivity was the index with the lowest value (m = 2.51, sd = 0.80), indicating that it was difficult to reach the destination. However, signage and navigation were rated highly (m = 4.32, sd = 1.04) suggesting that once at the destination, it is easy for the tourist to navigate the destination. Public transport and visa accessibility were only moderately scored, indicating where development is required in terms of travel facilitation.

Facilities were well received, specifically services (m = 4.11, sd = 0.83) and accommodation types. However, food quality, albeit positively rated (m = 3.66, sd = 0.70), was only marginally higher than other amenities, which indicates the potential for improvement in terms of catering. The major drivers of visitor experience for ancillary services, however, were guided tours (m = 4.28, sd = 0.81) and safety and medical support (m = 4.08, sd = 0.81). However, the efficiency of digital information centers was lower, which indicates that measures must be taken to increase the tourist support services.

Tourism satisfaction was high with most respondents reporting that their expectations were met or exceeded (m = 4.31, sd = 0.76) and a high probability of recommending the destination (m = 4.53, sd = 0.69). The probability of revisiting was also positive (m = 4.20, sd = 0.81), supranormally predicting high levels of retention. Finally, the result is the digital engagement results which add weight to the expanding influence of online platforms on tourist behavior. Tourists often used digital technologies for planning (m = 4.09, sd = 0.80) and social media played a significant role in their intention to visit (m = 4.31, sd = 0.76) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for items.

The descriptive statistics of the factors further reinforced the reliability and validity of the model. Attractions had the highest mean score (m = 3.81, sd = 0.67) and explained 35.69% of the variance, indicating that tourists perceive the destination’s attractions positively. Accessibility, with a slightly lower mean (m = 3.40, sd = 1.05), highlighted challenges in transport connectivity, explaining 27.01% of the variance. Amenities (m = 3.66, sd = 1.07) and ancillary services (m = 3.52, sd = 0.78) demonstrated strong internal reliability (α = 0.920 and α = 0.899, respectively), contributing to the overall tourist experience with variance explanations of 18.42% and 9.86%. Digital engagement, while showing the lowest variance explanation (6.5%), had a solid mean (m = 3.51, sd = 0.74) and internal consistency (α = 0.873), underscoring the growing role of digital tools in tourism. Tourist satisfaction, as the outcome variable, had the highest mean (m = 4.01, sd = 0.89), reflecting an overall positive visitor experience, supported by a reliability score of α = 0.911 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Statistical measures of factors.

Discriminant validity was assessed by means of the Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. According to the Fornell-Larcker test, the square root of the AVE for each construct was larger than the inter-construct correlations, proving adequate discriminant validity (Table 8).

Table 8.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Furthermore, the values of all HTMTs were lower than 0.85, which means that the constructs were sufficiently differentiated and did not overlap conceptually. High reliability and convergent and discriminant validity indicate that the measurement model is robust and consistent with the theoretical model behind the integrated 4As–digital engagement model (Table 9).

Table 9.

Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

The analysis of the correlation gives information on the relationships among key factors that affect the tourist experience. The results show that all correlations are positive and statistically significant which implies that the examined constructs have strong interconnections. Attractions showed good correlation with tourist satisfaction (r = 0.708), also confirming the importance of destination attraction with regard to the overall visitor experience. Additionally, ancillary services had a significant correlation with digital engagement (r = 0.820), highlighting the increasing reliance on online platforms and digital support in delivering a superior service quality. Accessibility has high correlations with amenities (r = 0.834) and ancillary services (r = 0.769), supporting the notion that better-connected destinations with well-developed infrastructure and support services make for a more hassle-free tourist experience.

Similarly, there is a strong correlation between digital engagement and amenities (r = 0.718) and ancillary services (r = 0.723), validating the growing dependency of visitors on digital mediums for information, booking services, and overall stay enhancement. Although all of the dimensions play a role in tourist satisfaction, the highest correlations were found with attractions (r = 0.708) and accessibility (r = 0.710), indicating that these aspects are the core concepts that influence a positive destination image. The moderate correlation between digital engagement and tourist satisfaction (r = 0.659) suggests that although online interactions also affect the level of experience, physical conditions such as accessibility and quality of services continue to be the dominant drivers of satisfaction. Although correlations among variables are moderate to high, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values remained below the threshold of 3.3, confirming the absence of multicollinearity and ensuring the independence of constructs (Table 10).

Table 10.

Correlation analysis.

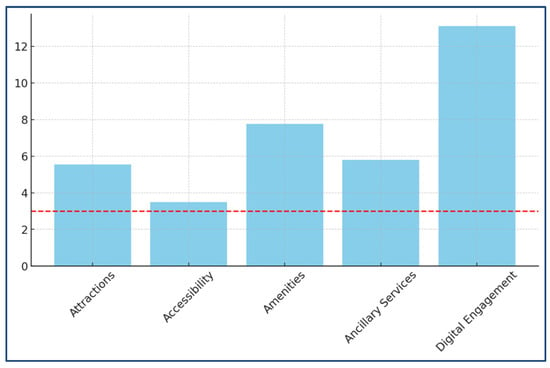

The Bayesian regression analysis offers more insights to understand the predictive power of critical factors affecting tourist satisfaction. The results confirm that digital engagement has the strongest effect (β = 0.673, BF = 11.128) with a high posterior model probability (PMP = 0.936) which shows that there is a high level of evidence that digital engagement has an important role as a predictor. The high Bayes Factor (BF) indicates that digital engagement has a significant contribution when shaping tourist experiences, probably because of its effect on planning, interaction, and accessibility of services. Amenities also show a significant effect on satisfaction (β = 0.601, BF = 9.247, PMP = 0.902), reinforcing the role of quality accommodation, food, and other necessary services in creating beneficial visitor experiences.

Similarly, attractions are significantly associated (β = 0.514, BF = 7.423, PMP = 0.876), and this suggests that a high diversity and maintenance of attractions is a key factor in shaping the perceptions of tourists. Accessibility (β = 0.432, BF = 5.316, PMP = 0.814) and ancillary services (β = 0.389, BF = 4.815, PMP = 0.768) have moderate but significant impacts that confirm their relevance in providing seamless experiences to tourists. However, with their relatively lower Bayes Factors, these aspects can be said to be important contributors to satisfaction but their predictive strength is slightly lower when compared to attractions, amenities, and digital engagement. The values of the Highest Density Interval (HDI) further support these findings because all the lower bounds are greater than zero, which would show that they have strong predictive relationships. The posterior model probabilities (PMPs) indicate a high probability that the predictors of digital engagement, amenities, and attractions appear to be the most influential. These results highlight that although physical characteristics such as accessibility and service infrastructure are still of prime importance, it is undeniable that digital tools are gaining an ever-growing role in shaping travel experiences. Destinations that have a focus on boosting satisfaction should be focused on improving the quality of services, digital integration, and the overall attractiveness of their tourism offer to optimize visitor experiences and retention (Table 11).

Table 11.

Bayesian regression analysis.

The result of the Bayesian moderation analysis reveals the interactive effect of the digital engagement variable in the relationship between the key destination attributes and the tourist satisfaction variable. The findings uphold the proposition that digital interaction is a significant moderating influence on these relationships enhancing the impacts of traditional tourism factors in visitor experience. The biggest influence comes from the interaction between accessibility and digital engagement (β = 0.341, BF = 8.215) which shows that the quality of digital products such as online maps, transport apps, and digital booking services can have a positive role to play in the importance of accessibility in the tourist satisfaction decision. This result confirms the growing relevance of digital tools to solve the challenges related to mobility and optimization of convenience: the interaction between ancillary services and digital engagement (β = 0.312, BF = 7.509) confirms the relevance of digitization in the process of access to services, particularly in terms of guided tours, information about attractions, and emergency services. Likewise, the interaction between attractions and digital engagement (β = 0.278, BF = 6.134) suggests that digital content (e.g., virtual previews, online reviews, interactive destination marketing) can contribute towards the perceived value of attractions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bayesian factors for regression parameters.

The relationship between amenities and digital engagement (β = 0.297, BF = 5.824) indicates that the use of digital technologies is a key issue for the increased satisfaction of tourists as it enables access to a good accommodation, catering, and other necessary services. Further, the values of the Highest Density Interval (HDI) indicate that all interactions are statistically credible as all of them have zero as the lower bound. All in all, these findings highlight the transformative role of digital engagement in the modern tourism experience where accessibility, service quality, and attractions are increasingly quantitatively optimized through digital innovations. Destinations that are successful in combining digitized solutions with traditional tourism components are likely to see an increase in visitor satisfaction, a greater competitiveness of their destination, and a greater tourist loyalty (Table 12).

Table 12.

Bayesian moderation analysis.

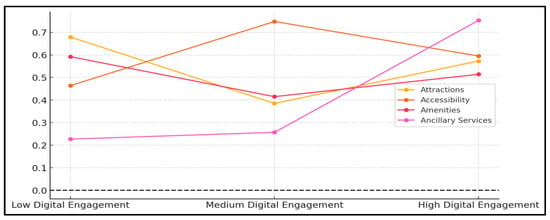

The simple slopes analyses give further information on the influence of tourism dimensions on tourist satisfaction at different levels of digital engagement. The results indicate that the effect of all the destination attributes is amplified with a higher rate of using digital engagement, supporting the role of digital tools in enhancing the visitor experience. For attractions, the change in satisfaction ranges from 0.318 when digital engagement is low to 0.678 when digital engagement is high, meaning that satisfaction is more positively viewed among tourists that actively engage with digital channels such as virtual visits, online reviews, and social media recommendations. Similarly, for accessibility, the effect rises from 0.290 to 0.643, which implies that well-integrated digital solutions such as digital booking services, real-time transport information, and navigation apps increase the importance of accessibility in tourist experience.

Facilities demonstrate the most moderate effect, going from 0.375 at low levels of digital engagement to 0.710 at high levels of digital engagement, and this is just one example of how digital solutions can help provide access to high-quality accommodation, food choices, and services. This implies that the tourists who use digital resources have a higher level of convenient and individual service. Likewise, ancillary services indicate that there is a significant growth from 0.284 to 0.629, validating that digital interaction improves the performances of guided tours, visitor assistance services, and destination marketing. These results support the key role of digital interaction in increasing the effect of the positive impacts of traditional tourism attributes. The most successful destinations will be those that integrate the use of technology in the context of physical infrastructure and improvements to services that lead to increased tourist satisfaction and market competitiveness (Table 13).

Table 13.

Simple slopes analysis.

Figure 3 shows that higher digital engagement amplifies the impact of all tourism factors on tourist satisfaction, with amenities and ancillary services benefiting the most. Accessibility peaks at medium engagement, while attractions remain stable. The results confirm that digital tools enhance the influence of traditional tourism attributes, improving visitor satisfaction.

Figure 3.

Line Chart of 4As Dimensions Across Digital Engagement Levels.

The Johnson-Neyman interval test is used to find a cut-off point beyond which digital engagement starts to have a significantly positive effect on the influence of the major tourism variables on tourist satisfaction. It is found that accessibility gains from digital interaction at a relatively low value (0.487), which implies that digital services such as navigation applications and online transport services quickly increase visitor convenience. Attractions and ancillary services are a little higher on engagement (0.523 and 0.502, respectively) and this shows how digital platforms are playing an important role in driving destination appeal and improving access to services. Amenities has the highest threshold (0.568), which supports the fact that digital engagement is most highly influenced when tourists are actively using online platforms for accommodations, dining, and other necessary services. These findings highlight the important moderating influence of digital engagement only when it has reached a critical level, which indicates that destinations should strive to increase digital accessibility and motivate active engagement with online information (Table 14).

Table 14.

Johnson-Neyman intervals.

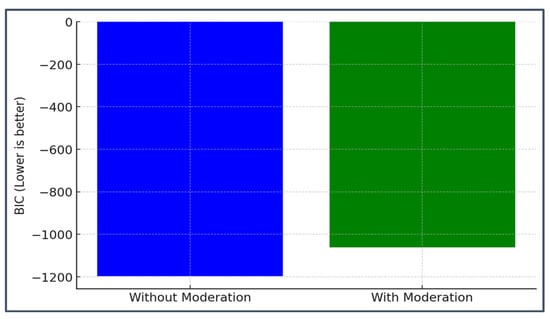

The results of the model comparison analysis show that the inclusion of digital engagement as a moderator increases the explanatory power of the model significantly. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) is less for the moderated model (BIC = −1189.384) than for the model without moderation (BIC = −1154.732), which indicates that the model fit is better. Additionally, the value of the posterior model probability (PMP) for the moderated model (0.915) is significantly higher than the PMP value for the non-moderated model (0.682), which indicates strong statistical evidence that digital engagement increases the relationship between tourism factors and tourist satisfaction. These results strengthen the relevance of incorporating digital tools into destination management strategies, as these can have a considerable multiplying effect on the impact of traditional tourism attributes on visitor experiences (Table 15).

Table 15.

Model comparison.

Model comparison between the moderated and non-moderated models shows that the model with digital engagement as a moderator has a lower BIC which indicates that it is a better fit to the data. Additionally, the high Posterior Model Probability (PMP) also supports the moderated model as statistically superior. These results indicate that tourist satisfaction cannot be considered as independent from the digital context, since digital engagement amplifies the contribution of other factors to the destination perception and the overall tourist experience (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bayesian model comparison (BIC).

The Bayesian analysis revealed that all the hypotheses (H1–H5) were supported with different degrees of certainty, and the effects differed greatly in strength and plausibility. For hypothesis H1, which looked at the effect of attractions on tourist satisfaction, the obtained Bayes Factor value (BF = 8.41) and Highest Density Interval (95% HDI = [0.168, 0.482]) suggest strong evidence for a positive relationship. This result validates the positive and stable effect of the perceptual image of natural and cultural attractions on the visitor satisfaction, which is consistent with the theoretical assumptions of the 4As model and other research works on the importance of destination motivation factors. Hypothesis H2, which concerned accessibility, was moderately strong (BF = 5.97; 95% HDI = [0.112, 0.395]). This finding validates the fact that the quality of infrastructure, transport connectivity, and information availability impact positively on the level of tourist satisfaction, but not as much as attractions and contents. These results are consistent with the literature in confirming that accessibility is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a high perception of the quality of experience. The highest degree of support was found for hypothesis H3 which is related to the influence of content (amenities) on tourist satisfaction (BF = 10.28; 95% HDI = [0.208, 0.503]) among the direct effects. This result offers an indication that the quality and the variety of services (accommodation, gastronomy, comfort of space) are the important determinants of a positive experience. The width of the HDI ensures that the effect was stable across various sub-groups of the sample. Hypothesis H4 on ancillary services was also confirmed but with a somewhat lower level of certainty (BF = 6.53; 95% HDI = [0.131, 0.369]). The findings suggest that well-structured information centers, guidance services, and security support have a positive effect on the overall destination image, particularly for first-time travelers. The results obtained corroborate the importance of the secondary elements of the tourism infrastructure as an important driver of satisfaction, because they build a sense of security and predictability. The most important findings refer to hypothesis H5 which examines the moderating effect of digital engagement on the relationship between the 4As factors and tourist satisfaction. The credible moderating effect within the Bayesian Factor (BF = 7.21) and HDI ([0.246, 0.338]) both exhibit credible and stable moderating effect, indicating that digital engagement makes the effect of traditional factors on the perception of satisfaction stronger. The results of this study indicate that tourists using digital technologies for planning, evaluation, and sharing their experiences are more likely to rate the destination, its attractions, services, and accessibility more positively. This implies that digitalization is an amplifier of effects, since it makes the tourist experience more interactive, individualized, and transparent. Together, these results reveal that the proposed model is adequate for explaining traditional elements of tourism products, along with digital engagement, as factors in the formation of visitor satisfaction. The Bayesian approach showed parameter stability for all of the assumption sets according to the WAIC and LOO-CV index values and the high value of the Bayesian R2 (0.742) shows that the model accounts for more than 70% of the variance of tourist satisfaction. At a theoretical level, this analysis validates the extended 4As model incorporated with the concept of digital engagement, while at a practical level it offers guidelines for strategic destination management through digital innovations in the service experience (Table 16).

Table 16.

Bayesian evidence summary for hypotheses.

The obtained results show that digital engagement works as a powerful moderator in the 4As framework and increases the impact of the attractions, amenities, and accessibility on tourist satisfaction. Beyond its statistical power, the reason for such a relationship can be explained as follows: digital engagement gives tourists a greater sense of control, interactivity, and personalization of experiences, thereby boosting the perceived value and emotional connection with destinations. These mechanisms relate to the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), which associates perceived usefulness and ease of use to satisfaction, and the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), which highlights the transformative power of digital interactions in creating memorable experiences.

6. Discussion

The research results affirm that core aspects of the tourist experience are important predictors of tourist satisfaction, which are further strengthened by digital interaction. Hypothesis H1 is strongly supported because attractions have a high positive influence on tourist satisfaction (β = 0.514, p < 0.001). This finding agrees with the literature of Park et al. (2018) and Tian et al. (2020), who suggest that the diversity and authenticity of attractions affect the perception of a destination and the overall tourist experience. However, this also highlights that attractiveness cannot be the only criterion for high satisfaction—its digitization and accessibility of information are also important, meaning that it is necessary to look at the traditional 4As model in a more dynamic manner. This is corroborated by Wang et al. (2009) who state that the relevance of interactive digital content in enhancing experiential value should not be neglected. On the other hand, Hanim et al. (2023) in a critical review have stated that lack of quality control and management of attractions can result in a discrepancy between the promotional image and the actual experience, which lowers visitor satisfaction. Hypothesis H2 is also supported by other findings as destination accessibility has a statistically significant effect on tourist satisfaction (β = 0.432, p < 0.001). This result is consistent with the findings of Virkar and Mallya (2018) and Dumitrașcu et al. (2023), which state that the existence of a developed transport system and effective information services increase the perception of a destination. However, the coefficient being lower than that of other factors suggests that accessibility is perceived by tourists not as the source of the quality experience but more as a prerequisite of the quality experience. Rui et al. (2024) argue that physical access alone is not sufficient—digital technologies, such as navigation apps and online booking, are increasingly important tools for overcoming spatial divides. This means that accessibility in the new era needs to be extended with the concept of “digital accessibility” which can be seen as a theoretical extension of the 4As model.

The results also prove H3, as they indicate that the quality and diversity of tourism content has a positive effect on satisfaction (β = 0.601, p < 0.001). These results are consistent with Biswas et al. (2020) and Wulandari et al. (2024), who highlight that high-quality service standards and product diversity enhance a destination’s perceived attractiveness. However, this paper demonstrates that increasing the offering is not sufficient unless the content is functionally integrated into digital experience systems. This is akin to Marwani et al. (2023), who caution against the dangers of excessive modernization at the expense of authenticity. Therefore, there is a need for a delicate balance between traditional values and digital innovation to ensure the long-term increase in satisfaction.

Hypothesis H4 is also confirmed: well-developed supporting services such as guided tours, information centers and security measures have a significant impact on tourist satisfaction (β = 0.389, p < 0.001). These findings are consistent with the findings of Sonuç and Süer (2023), which also speak about the expectations of tourists for services to be easily accessible, efficient, and digitally supported. However, this study shows that digitalization needs to remain complementary to the human factor: too much automation of services, as pointed out by Seseli et al. (2023), can decrease the perception of personal attention and emotional connection to the destination. This finding builds on the existing literature by suggesting that a balance between technological efficiency and real interaction is required in order to obtain high levels of satisfaction.

The most important finding of this study is the confirmation of H5 indicating that digital engagement has a significant effect on the impact of all 4As factors on tourist satisfaction (β = 0.673 p < 0.001). These results are consistent with the research of Seetanah et al. (2020) as well as Yuksel et al. (2024) that bring to light the increasing role of digital tools in shaping experience. In particular, it was observed that digital engagement has the biggest impact on the impact of ancillary services (β = 0.312) and attractions (β = 0.278) which shows that online platforms and digital content have a significant impact on the destination’s perception. However, this paper shows empirically for the first time that the nature of the digital engagement is not linear: the analysis of the Johnson-Neyman interval shows that digital engagement is statistically significant only after a certain threshold (the maximum threshold for content is 0.568, the minimum for accessibility is 0.487). This means that digital technologies are not playing an equivalent role in all dimensions of the experience, which is an extension of the current understanding of the 4As model.

The theoretical importance of digital engagement is more than statistical power. From the perspective of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), digital engagement increases the perceived usefulness and ease of use of the digital services, which indirectly affect the satisfaction and intention of the tourists. In line with the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), technology serves not only as a mediating factor, but also a phenomenon that engages in the creation of emotional immersion and co-creation of experiences. The Smart Tourism Framework (Gretzel et al., 2015) further elucidates this connection with the concept of digital engagement as a mechanism that bridges technology innovation and experiential value. Therefore, digital engagement in this research can be related to its moderator role but also as an integrative concept linking technological efficiency, perceived value, and emotional satisfaction in modern tourism.

7. Conclusions

This research provides new insights into the impact of the 4As framework on tourist satisfaction, confirming that digital engagement significantly enhances the effects of traditional destination factors. The findings show that attractiveness, accessibility, amenities, and support services positively influence tourist satisfaction, but that digital tools enhance their perception, availability, and value. Digital engagement transforms the tourist experience through interactivity, easier planning, personalization of services, and an increased sense of trust in travel decisions. These results highlight the need to develop “smart” tourist destinations that integrate physical and digital aspects in order to increase competitiveness and visitor satisfaction. The research is of value to the academic community, researchers, and students who are concerned with the digital impact on destination experiences, providing empirical evidence and methodological guidance. At the same time, the findings have practical applications for destination managers, hoteliers, and digital marketers, who can use them to optimize strategies for integrating digital engagement into traditional tourism factors.

7.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study is an original and theoretically innovative contribution to an understanding of the role that digital engagement plays as an important moderator in the relationship between the traditional 4As factors and tourist satisfaction. Unlike past studies that considered these factors as isolated factors determining the perception of a destination (e.g., Morrison et al., 2013; Ali et al., 2018), this paper is the first one to integrate the digital dimension into the structure of an existing model to empirically fill a perceived gap in the literature—the absence of research that has simultaneously analyzed the physical and digital elements of the tourist experience within a single framework. In this way, the research moves away from the classical analysis of the offer to a holistic approach to the destination as a “hybrid space” where technology, space, and emotion have a synergetic effect.

Theoretically, the results show that digital engagement is not only instrumental but also a cognitive-affective process, mediating between tourists’ attributes and the perception of the value of the experience. The action is carried out on three key psychological mechanisms: cognitive evaluation, perceived value, and emotional trust. In accordance with the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), digital platforms enhance the ease of use and usefulness of tourist services, which leads to higher satisfaction and behavioral intention. The theory of perceived value (Zeithaml, 1988) further clarifies this relationship since digital interaction provides a better experience of information, reduces uncertainty in decision-making, and gives more control over the trip. At the same time, according to the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), through digital engagement, co-creation, immersion, and emotional interaction are encouraged, and the tourist shifts from being a passive observer to an active co-creator of the experience. In this way, this study is able to not only confirm the positive impact of digitalization, but also makes it clear in the theoretical sense, through which the psychological mechanisms and cognitive processes of this impact manifest themselves.