Palms Beyond the Forests: The Ex Situ Conservation at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

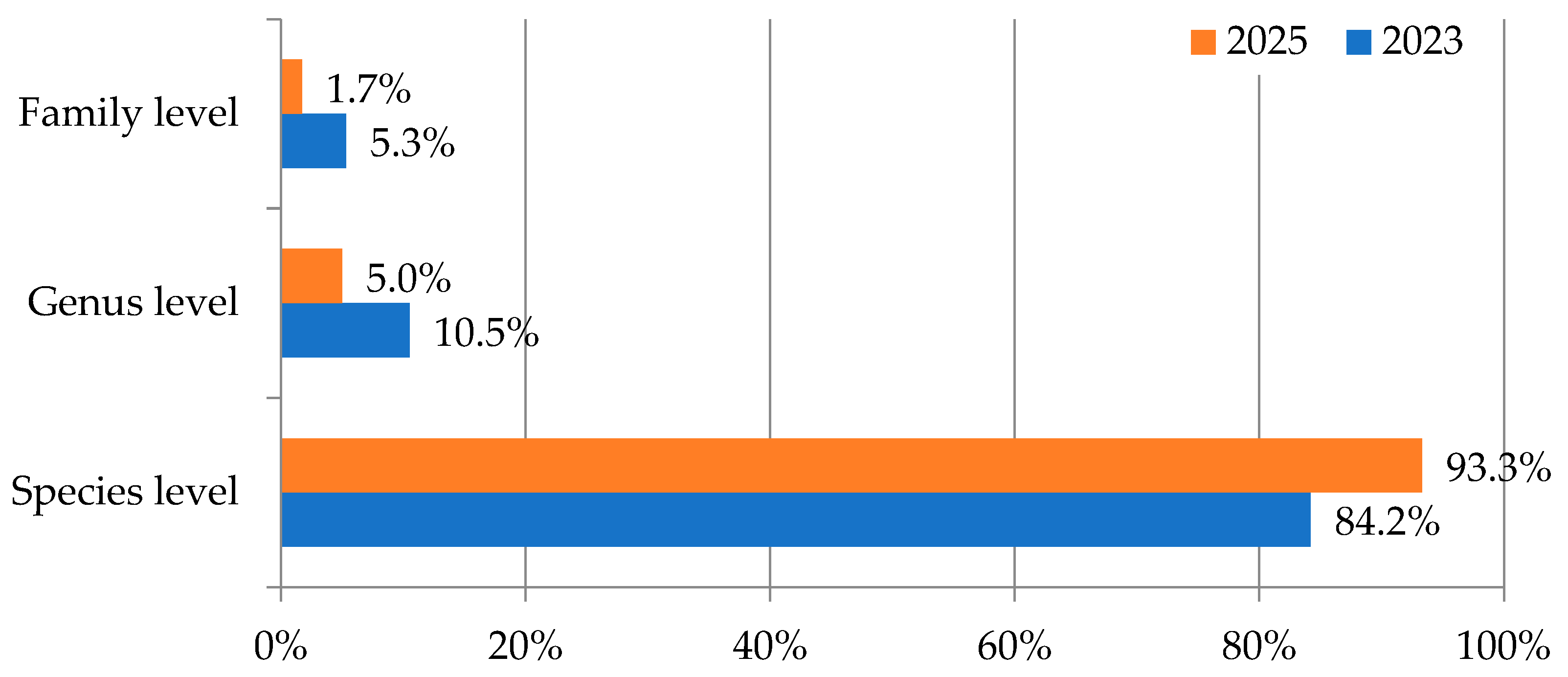

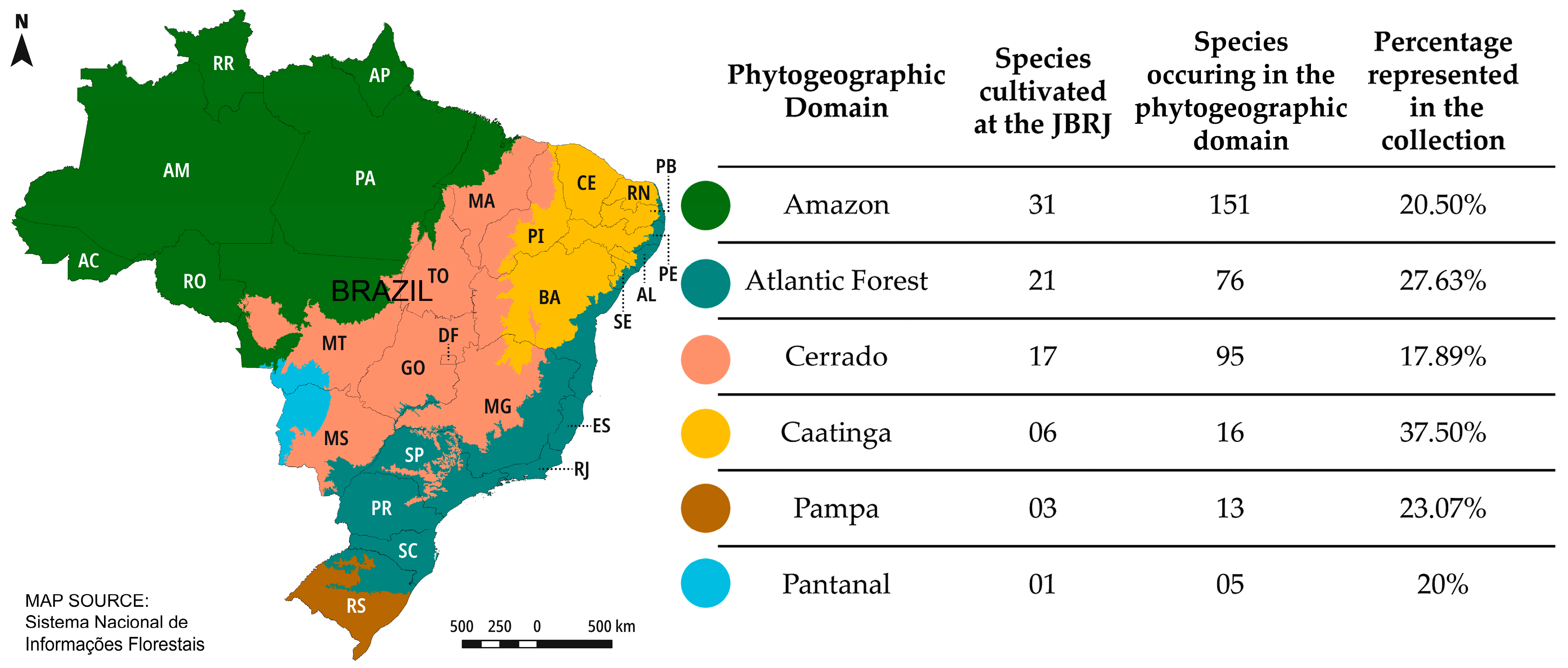

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Taxa |

|---|

| Acanthophoenix rubra (Bory) H.Wendl. |

| Acoelorraphe wrightii (Griseb. & H.Wendl.) H.Wendl. ex Becc. |

| Acrocomia aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. |

| Acrocomia intumescens Drude |

| Adonidia merrillii (Becc.) Becc. |

| Aiphanes hirsuta Burret |

| Aiphanes horrida (Jacq.) Burret |

| Aiphanes minima (Gaertn.) Burret |

| Allagoptera arenaria (Gomes) Kuntze |

| Allagoptera caudescens (Mart.) Kuntze |

| Archontophoenix alexandrae (F.Muell.) H.Wendl. & Drude |

| Archontophoenix cunninghamiana (H.Wendl.) H.Wendl. & Drude |

| Archontophoenix maxima Dowe |

| Areca catechu L. |

| Areca triandra Roxb. ex Buch.-Ham. |

| Areca vestiaria Giseke |

| Arenga engleri Becc. |

| Arenga undulatifolia Becc. |

| Astrocaryum aculeatissimum (Schott) Burret |

| Astrocaryum jauari Mart. |

| Astrocaryum murumuru Mart. |

| Attalea butyracea (Mutis ex L.f.) Wess.Boer |

| Attalea funifera Mart. |

| Attalea humilis Mart. |

| Attalea maripa (Aubl.) Mart. |

| Attalea oleifera Barb.Rodr. |

| Attalea phalerata Mart. ex Spreng. |

| Attalea speciosa Mart. ex Spreng. |

| Bactris concinna Mart. |

| Bactris gasipaes Kunth |

| Bactris major Jacq. |

| Bactris maraja Mart. |

| Bactris setosa Mart. |

| Bentinckia nicobarica (Kurz.) Becc. |

| Borassus aethiopum Mart. |

| Borassus flabellifer L. |

| Burretiokentia hapala H.E.Moore |

| Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. |

| Butia purpurascens Glassman |

| Butia yatay (Mart.) Becc. |

| Calamus ciliaris Blume |

| Calamus flagellum Griff. ex Walp. |

| Calyptrocalyx forbesii (Ridl.) Dowe & M.D.Ferrero |

| Calyptrocalyx spicatus (Lam.) Blume |

| Carpentaria acuminata (H.Wendl. & Drude) Becc. |

| Caryota mitis Lour. |

| Caryota urens L. |

| Chamaedorea metallica O.F.Cook ex H.E.Moore |

| Chamaerops humilis L. |

| Chambeyronia macrocarpa (Brongn.) Vieill. ex Becc. |

| Chrysalidocarpus madagascariensis (D.T.Fish) Becc. |

| Cocos nucifera L. |

| Copernicia alba Morong |

| Copernicia macroglossa H.Wendl |

| Corypha umbraculifera L. |

| Corypha utan Lam. |

| Cryosophila nana (Kunth) Blume |

| Cyrtostachys renda Blume |

| Desmoncus orthacanthos Mart. |

| Dictyosperma album (Bory) H.Wendl. & Drude ex Scheff. |

| Dictyosperma album var. aureum Balf.f. |

| Dictyosperma album var. conjugatum H.E.Moore & Guého |

| Dypsis decaryi (Jum.) Beentje & J.Dransf. |

| Dypsis lutescens (H.Wendl.) Beentje & J.Dransf. |

| Elaeis guineensis Jacq. |

| Elaeis oleifera (Kunth) Cortés |

| Euterpe edulis Mart. |

| Euterpe longibracteata Barb.Rodr. |

| Euterpe oleracea Mart. |

| Euterpe precatoria Mart. |

| Hyophorbe lagenicaulis (L.H.Bailey) H.E.Moore |

| Hyophorbe verschaffeltii H.Wendl. |

| Iriartea deltoidea Ruiz & Pav. |

| Latania lontaroides (Gaertn.) H.E.Moore |

| Leopoldinia piassaba Wallace |

| Leucothrinax morrisii (H.Wendl.) C.Lewis & Zona |

| Licuala grandis H.Wendl. ex Linden |

| Licuala peltata Roxb. ex Buch.-Ham. |

| Licuala rumphii Blume |

| Licuala spinosa Wurmb |

| Livistona australis (R.Br.) Mart. |

| Livistona chinensis (Jacq.) R.Br. ex Mart. |

| Livistona decora (W.Bull) Dowe |

| Livistona saribus (Lour.) Merr. ex A.Chev. |

| Manicaria saccifera Gaertn. |

| Mauritia flexuosa L.f. |

| Mauritiella aculeata (Kunth) Burret |

| Mauritiella armata (Mart.) Burret |

| Nypa fruticans Wurmb |

| Oenocarpus bacaba Mart. |

| Oenocarpus distichus Mart. |

| Oenocarpus mapora H.Karst. |

| Oenocarpus minor Mart. |

| Oncosperma fasciculatum Thwaites |

| Oncosperma tigillarium (Jack) Ridl. |

| Orania palindan (Blanco) Merr. |

| Phoenicophorium borsigianum (K.Koch) Stuntz |

| Phoenix canariensis H.Wildpret |

| Phoenix dactylifera L. |

| Phoenix loureiroi Kunth var. loureiroi |

| Phoenix pusilla Gaertn. |

| Phoenix reclinata Jacq. |

| Phoenix roebelenii O’Brien |

| Phoenix rupicola T.Anderson |

| Phoenix sylvestris (L.) Roxb. |

| Phytelephas macrocarpa Ruiz & Pav. |

| Pinanga coronata (Blume ex Mart.) Blume |

| Pinanga patula Blume |

| Plectocomia elongata Mart. ex Blume |

| Pritchardia pacifica Seem. & H.Wendl. |

| Ptychosperma elegans (R.Br.) Blume |

| Ptychosperma macarthurii (H.Wendl. ex H.J.Veitch) H.Wendl. ex Hook.f. |

| Ptychosperma propinquum (Becc.) Becc. ex Martelli |

| Ptychosperma salomonense Burret |

| Ptychosperma sanderianum Ridl. |

| Raphia farinifera (Gaertn.) Hyl. |

| Raphia taedigera (Mart.) Mart. |

| Ravenea rivularis Jum. & H. Perrier |

| Rhapis excelsa (Thunb.) A.Henry |

| Rhopaloblaste ceramica (Miq.) Burret |

| Roystonea borinquena O.F.Cook |

| Roystonea oleracea (Jacq.) O.F.Cook |

| Roystonea regia (Kunth) O.F.Cook |

| Sabal bermudana L.H.Bailey |

| Sabal causiarum (O.F.Cook) Becc. |

| Sabal mauritiiformis (H.Karst.) Griseb. & H.Wendl. |

| Sabal mexicana Mart. |

| Sabal minor (Jacq.) Pers. |

| Sabal palmetto (Walter) Lodd. ex Schult. & Schult.f. |

| Salacca affinis Griff. |

| Salacca zalacca (Gaertn.) Voss |

| Saribus rotundifolius (Lam.) Blume |

| Socratea exorrhiza (Mart.) H.Wendl. |

| Syagrus botryophora (Mart.) Mart. |

| Syagrus cearensis Noblick |

| Syagrus cocoides Mart. |

| Syagrus coronata (Mart.) Becc. |

| Syagrus duartei Glassman |

| Syagrus kellyana Noblick & Lorenzi |

| Syagrus macrocarpa Barb.Rodr. |

| Syagrus oleracea (Mart.) Becc. |

| Syagrus picrophylla Barb.Rodr. |

| Syagrus pseudococos (Raddi) Glassman |

| Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.) Glassman |

| Syagrus schizophylla (Mart.) Glassman |

| Syagrus vagans (Bondar) A.D.Hawkes |

| Syagrus x camposportoana (Bondar) Glassman |

| Syagrus x matafome (Bondar) A.D.Hawkes |

| Tahina spectabilis J. Dransf. & Rakotoarin. |

| Thrinax parviflora Sw. |

| Thrinax radiata Lodd. ex Schult. & Schult.f. |

| Veitchia joannis H.Wendl. |

| Veitchia subdisticha (H.E.Moore) C.Lewis & Zona |

| Verschaffeltia splendida H.Wendl. |

| Wallichia oblongifolia Griff. |

| Washingtonia robusta H.Wendl. |

| Wodyetia bifurcata A.K.Irvine |

References

- Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Anja, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Moraes, M.; Grandez, C.; Balslev, H. Diversity of palm uses in the western Amazon. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 2771–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, K.P.; Longhi, S.J.; Witeck Neto, L.; Assis, L.C. Palmeiras (Arecaceae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Rodriguésia 2014, 65, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plants of the World Online (POWO). Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Bellot, S.; Lu, Y.; Antonelli, A.; Baker, W.J.; Dransfield, J.; Forest, F.; Kissling, W.D.; Leitch, I.J.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Ondo, I.; et al. The likely extinction of hundreds of palm species threatens their contributions to people and ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora e Funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available online: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Portaria n. 148, de 7 de Junho de 2022. Available online: https://in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-mma-n-148-de-7-de-junho-de-2022-406272733 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Barbosa Rodrigues, J. Palmae Mattogrossenses Novae vel Minus Cognitae; Leuzinger: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1898; p. 13. Available online: http://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/242527 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Santos, A.B. Colonização, Quilombos: Modos e Significações; Editora UnB e INCTI: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barstow, M.; Dobai, N.; Cowell, C. The Importance of Botanic Gardens in Tackling the Illegal Plant Trade; BGCI: Richmond, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.bgci.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2-FINAL_Illegal-Plant-Trade.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Kitching, M.; Sharrock, S.; Smith, P. Purpose and Trends in Exchange of Plant Material Between Botanic Gardens; BGCI: Richmond, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.bgci.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/PlantexchangeMRReduced-1.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Oldfield, S.F. Botanic gardens and the conservation of tree species. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, N.; Cunha, T.S.; Pereira, R.C.; Turini, L.R.; Barbosa, O.R.; Almeida, J.R. Gestão de jardins botânicos. Rev. Int. Ciênc. 2023, 13, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, N.; Donnelly, G. Intersecting Urban Forestry and Botanical Gardens to Address Big Challenges for Healthier Trees, People, and Cities. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.P.; Meyer, A.; Grinage, A. Global ex situ conservation of palms: Living treasures for research and education. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 711414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, T.M.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.; Bravo, C.; Taylor, T.C.; Fadrique, B.; Hogan, J.A.; Pardo, C.J.; Stroud, J.T.; Baraloto, C.; Feeley, K.J. Botanic gardens are an untapped resource for studying the functional ecology of tropical plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2019, 374, 20170390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosmann, M.; Groover, A.C. The importance of living botanical collections for plant biology and the “next generation” of evo-devo research. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Partnership for Plant Conservation. The Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2020–2030; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, Lei n. 10.316, de 6 de Dezembro de 2001. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10316.htm (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Brasil. Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. Resolução CONABIO n. 9, de 28 de Novembro de 2024. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-conabio-n-9-de-28-de-novembro-de-2024-613697262 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Almeida, T.M.H.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Peixoto, A.L. Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden: Biodiversity Conservation in a Tropical Arboretum. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M. Allegory of the palma mater: An invented tradition. Rodriguésia 2022, 73, e00142022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Rodrigues, J. Sertum Palmarum Brasiliensium; Typographique Veuve Monnom: Brussels, Belgium, 1903; Available online: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/242529 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Marcolin, N. A glória de um botânico: Há 110 anos João Barbosa Rodrigues publicava livro clássico sobre palmeiras. Rev. Pesqui. FAPESP 2013, 210, 88–89. Available online: https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/a-gloria-do-botanico/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- PCRJ (Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro). Revisão do Plano Municipal de Saneamento Básico para os Serviços de Abastecimento de Água e Esgotamento Sanitário; DRZ Geotecnologia e Consultoria LTDA: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://rio.rj.gov.br/dlstatic/10112/12401025/4313006/ETAPA1CaracterizacaodoMunicipioPMSBRJ.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Silva, L.A.E.; Fraga, C.N.; Almeida, T.M.H.; Gonzalez, M.; Lima, R.O.; Rocha, M.S.; Bellon, E.; Ribeiro, R.S.; Oliveira, F.A.; Clemente, L.S.; et al. Jabot—Sistema de gerenciamento de coleções botânicas: A experiência de uma década de desenvolvimento e avanços. Rodriguésia 2017, 68, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Jabot (Scientific Collections Management Software); Version 3.0; Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2025. Available online: http://rb.jbrj.gov.br/v2/consulta.php (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- CNCFlora—Centro Nacional de Conservação da Flora. Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. Brazil. Available online: https://cncflora.jbrj.gov.br/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- IUCN—International Union for Conservation of Nature. Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- BGCI. PlantSearch Online Database. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Richmond, UK. Available online: https://plantsearch.bgci.org/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Oliveira, A.R.; Teixeira, M.L.F.; Reis, R. As Palmeiras-Imperiais do Jardim Botânico; Editora Dantes: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; 112p. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Sistema Nacional de Informações Florestais (SNIF). Brasília, DF: Serviço Florestal Brasileiro (SFB). Available online: https://snif.florestal.gov.br/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Bediaga, B.; Lima, H.C.L.; Morim, M.P.; Barros, C.F. As atividades científicas durante dois séculos. In Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: 1808–2008; Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil. Relatório do Ministério da Agricultura, Comércio e Obras Públicas (RJ) do Ano de 1891; Imprensa Nacional: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1891; pp. 25–26. Available online: https://memoria.bn.br/docreader/DocReader.aspx?bib=873730&Pesq&pagfis=1 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Cavender, N.; Westwood, M.; Bechtoldt, C.; Donnelly, G.; Oldfield, S.; Gardner, M.; Rae, D.; McNamara, W. Strengthening the conservation value of ex situ tree collections. Oryx 2015, 49, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.P.; Barber, G.; Lima, J.T.; Barros, M.; Calonje, C.; Magellan, T.; Dosmann, M.; Thibault, T.; Gerlowski, N. Plant Collection “Half-life”: Can Botanic Gardens Weather the Climate? Curator Mus. J. 2017, 60, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.C.; Daibes, L.F.; Damasceno-Junior, G.A.; Lima, L.B. Water immersion and one-year storage influence the germination of the pyrenes of Copernicia alba Morong, a palm tree from a neotropical wetland. Hoehnea 2022, 49, e782021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold Arboretum. Developing an Exemplary Collection. Available online: http://arboretum.harvard.edu/stories/developingan-exemplary-collection-a-vision-for-the-next-century-at-the-arnold-arboretum-of-harvard-university/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Frugeri, G.C.; Nogueira, G.F.; Souza, A.L.X.; Scherwinski-Pereira, J.E. Designing ex situ conservation strategies for Butia capitata [Mart. (Becc.) Arecaceae], a threatened palm tree from the Brazilian savannah biome, through zygotic embryo cryopreservation. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2023, 14, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namoff, S.; Francisco-Ortega, J.; Lewis, C.E.; Zona, S.; Vamosi, J.C.; Griffith, M.P. How well does a botanical garden collection of a rare palm capture the genetic variation in a wild population? Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.P.; Noblick, L.R.; Dowe, J.L.; Husby, C.E.; Calonje, M. Can a botanic garden cycad collection capture the genetic diversity in a wild population? Int. J. Plant Sci. 2008, 169, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.P.; Beckman, E.; Callicrate, T.; Clark, J.; Clase, T.; Deans, S.; Dosmann, M.; Fant, J.; Gratacos, X.; Havens, K.; et al. Toward the Metacollection: Safeguarding Plant Diversity and Coordinating Conservation Collections; Botanic Gardens Conservation International–US: San Marino, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.bgci.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Toward-the-Metacollection-Coordinating-conservation-collections-to-safeguard-plant-diversity.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

| Species | Threat Status * | N° of Botanical Gardens with the Species (in Addition to JBRJ) ** |

|---|---|---|

| Exotic species | ||

| Acanthophoenix rubra (Bory) H.Wendl. | CR | 08 |

| Adonidia merrillii (Becc.) Becc. | VU | 77 |

| Bentinckia nicobarica (Kurz.) Becc. | EN | 04 |

| Burretiokentia hapala H.E.Moore | EN | 23 |

| Dictyosperma album var. aureum Balf.f. | CR | 02 |

| Dictyosperma album var. conjugatum H.E.Moore & Guého | CR | 01 |

| Dypsis decaryi (Jum.) Beentje & J.Dransf. | VU | 88 |

| Hyophorbe lagenicaulis (L.H.Bailey) H.E.Moore | CR | 102 |

| Hyophorbe verschaffeltii H.Wendl. | CR | 82 |

| Latania lontaroides (Gaertn.) H.E.Moore | EN | 64 |

| Ravenea rivularis Jum. & H. Perrier | VU | 63 |

| Sabal bermudana L.H.Bailey | EN | 61 |

| Sabal causiarum (O.F.Cook) Becc. | VU | 52 |

| Tahina spectabilis J. Dransf. & Rakotoarin. | CR | 25 |

| Native species | ||

| Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. | VU | 114 |

| Butia purpurascens Glassman | EN | 03 |

| Butia yatay (Mart.) Becc. | VU | 32 |

| Euterpe edulis Mart. | VU | 38 |

| Syagrus botryophora (Mart.) Mart. | VU | 13 |

| Syagrus kellyana Noblick & Lorenzi | EN | 05 |

| Syagrus macrocarpa Barb.Rodr. | EN | 08 |

| Syagrus picrophylla Barb.Rodr. | VU | 07 |

| Native Species | Number of Specimens with Known Provenance | Endemic to Brazil | Threat Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. | 00 | Yes | VU |

| Butia purpurascens Glassman | 01 | Yes | EN |

| Butia yatay (Mart.) Becc. | 00 | No | VU |

| Euterpe edulis Mart. | 07 | No | VU |

| Syagrus botryophora (Mart.) Mart. | 01 | Yes | VU |

| Syagrus kellyana Noblick & Lorenzi | 01 | Yes | EN |

| Syagrus macrocarpa Barb.Rodr. | 01 | Yes | EN |

| Syagrus picrophylla Barb.Rodr. | 01 | Yes | VU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbosa, C.M.F.; Gonzaga, D.R.; Favares, T.; Mynssen, C.M.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Almeida, T.M.H.d. Palms Beyond the Forests: The Ex Situ Conservation at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010004

Barbosa CMF, Gonzaga DR, Favares T, Mynssen CM, Coelho MAN, Almeida TMHd. Palms Beyond the Forests: The Ex Situ Conservation at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbosa, Claudia Maria Ferrari, Diego Rafael Gonzaga, Thiago Favares, Claudine Massi Mynssen, Marcus Alberto Nadruz Coelho, and Thaís Moreira Hidalgo de Almeida. 2026. "Palms Beyond the Forests: The Ex Situ Conservation at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010004

APA StyleBarbosa, C. M. F., Gonzaga, D. R., Favares, T., Mynssen, C. M., Coelho, M. A. N., & Almeida, T. M. H. d. (2026). Palms Beyond the Forests: The Ex Situ Conservation at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010004