Factors That Influence the Teachers’ Involvement in Outdoor, Nature-Based Educational Activities and Environmental Education Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

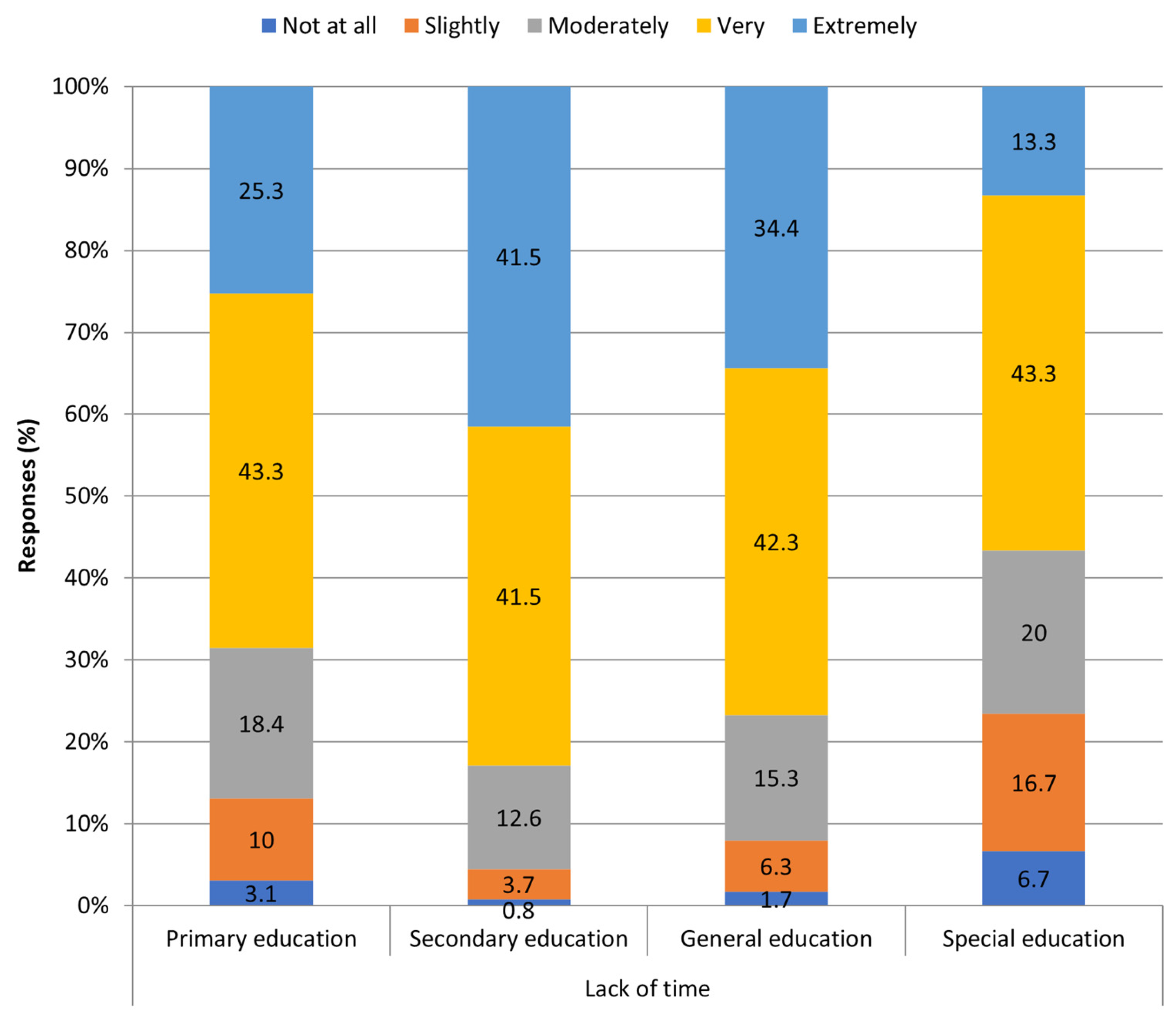

3.1. Factors Limiting the Number of Visits Organized by the School to Places Outside the School Premises Where Pupils Can Have Direct Contact with Nature

3.2. Factors Limiting the Opportunities the Schools Provide for Outdoor Activities Inside the School Premises

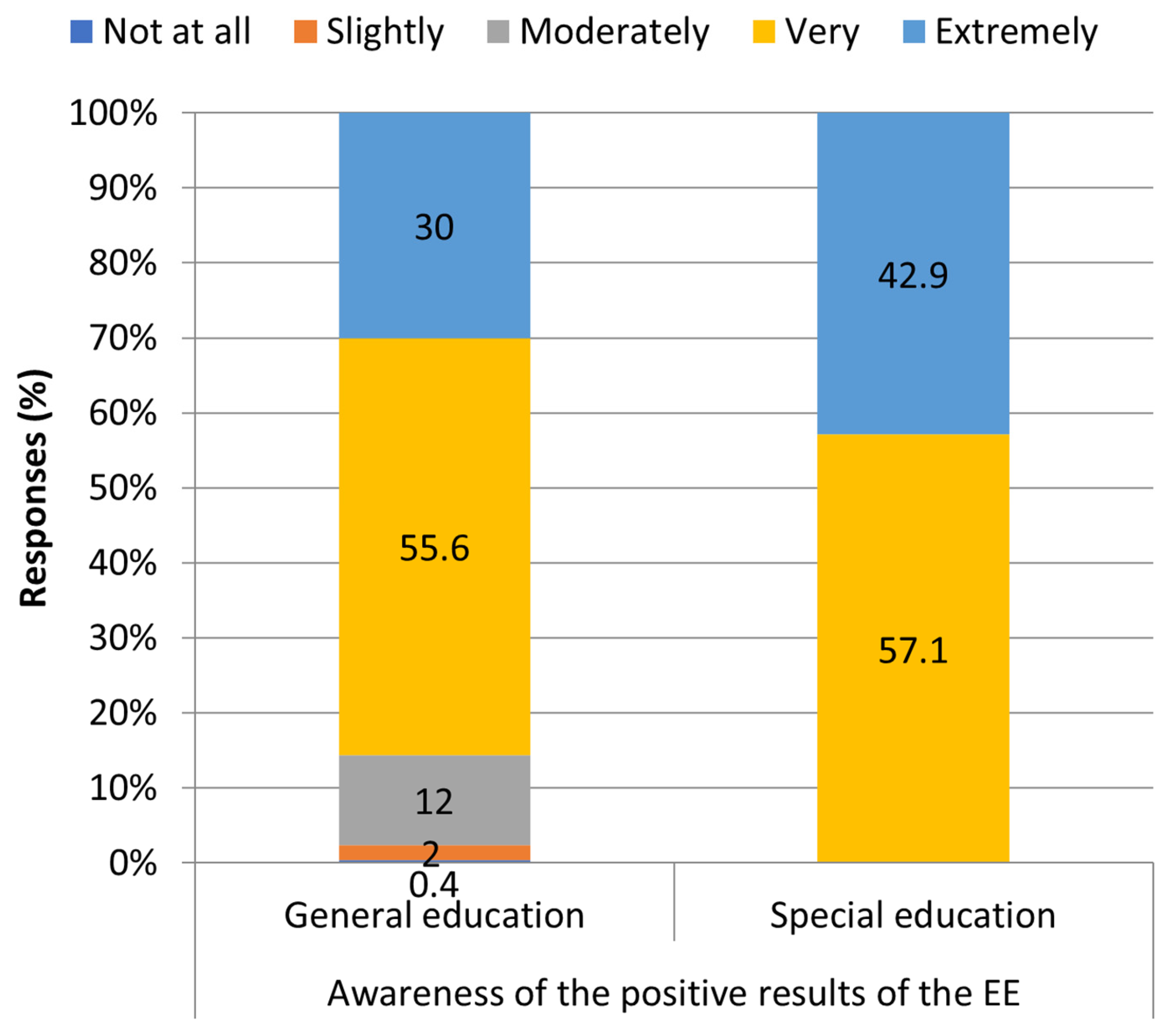

3.3. Factors That Influence the Teachers Who Show Interest in the Implementation of EEPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robinson, J.M.; Barrable, A. Optimising early childhood educational settings for health using nature-based solutions: The microbiome aspect. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Cormack, A.; McRobert, L.; Underhill, R. 30 Days wild: Development and evaluation of a large-scale nature engagement campaign to improve well-being. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, S.; Staats, H.; Corraliza, J.A. Experiencing nature in children’s summer camps: Affective, cognitive and behavioural consequences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.G.; Barene, S. Exploring the Associations Between School Climate and Mental Wellbeing: Insights from the MOVE12 Pilot Study in Norwegian Secondary Schools. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsanuto, S.; Cassese, F.P.; Tafuri, F.; Tafuri, D. Outdoor Education, Integrated Soccer Activities, and Learning in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Project Aimed at Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, G. “Building roots”—Developing agency, competence, and a sense of belonging through education outside the classroor. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Lauterbach, G.; Spengler, S.; Dettweiler, U.; Mess, F. Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, K.; Collins, C.; Bolger, M.K.; Butler, F. Science Education in Primary Students in Ireland: Examining the Use of Zoological Specimens for Learning. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Feucht, V.; Becker, M.; Dierkes, P.W. Environmental Education in Zoos—Exploring the Impact of Guided Zoo Tours on Connection to Nature and Attitudes towards Species Conservation. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2022, 3, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Savahl, S. Nature as children’s space: A systematic review. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 291–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Experiencing nature: Affective, cognitive, and evaluative development. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; Kahn, P.H., Jr., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 117–151. [Google Scholar]

- Soga, M.; Yamanoi, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kanai, T. What are the drivers of and barriers to children’s direct experiences of nature? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, K.L.; Freeman, C.; Seddon, P.J.; Recio, M.R.; Stein, A.; Heezik, Y. Restricted home ranges reduce children’s opportunities to connect to nature: Demographic, environmental and parental influences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 172, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: Evidence, consequences and challenges of loss of human-nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural England. Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: A Pilot to Develop an Indicator of Visits to the Natural Environment by Children; Natural England: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Natural England. Childhood and Nature: A Survey on Changing Relationships with Nature Across Generations; Natural England: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Mou, S. Outdoor Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S. Where are we going? International views on purposes, practices and barriers in school-based outdoor learning. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, G.W.; Donaldson, L.E. Outdoor Education a Definition. J. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1958, 29, 17–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glackin, M. ‘Control must be maintained’: Exploring teachers’ pedagogical practice outside the classroom. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilthuizen, Μ. Darwin Goes to Town: The Paths of Evolution in the Modern Urban Environment; University Publications of Crete: Crete, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tilling, S. Ecological science fieldwork and secondary school biology in England: Does a more secure future lie in Geography? Curric. J. 2018, 29, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Lance, K. Biophilic boulder: Children’s environments that foster connections to nature. Child. Youth Environ. 2012, 22, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M.; Dillon, J.; Teamey, K.; Morris, M.; Choi, M.Y.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. A Review of Research on Outdoor Learning; Field Studies Council: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, M.; Passy, R.; Waite, S.; Cook, R. Exploring schools’ use of natural spaces. In Risk, Protection, Provision and Policy, Geographies of Children and Young People; Freeman, C., Tranter, P., Skelton, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, P. To be in the garden or not to be in the garden—That is the question here: Some aspects of the educational chances that are inherent in tamed and untamed nature. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 15, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Barfod, K.S. Primary teachers’ experiences with weekly education outside the classroom during a year. Educ. 3-13 2019, 47, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.; Slingsby, D.; Tilling, S. Teaching Biology Outside the Classroom. Is It Heading for Extinction? A Report on Biology Fieldwork in the 14–19 Curriculum; Field Studies Council/British Ecological Society: Preston Montford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ulset, V.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Bekkhus, M.; Borge, A.I.H. Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, O.; Mérac, E.R.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Meloni, C.; Isoni, C.; Livi, S.; Fornara, F. A Comparison of Outdoor Green and Indoor Education: Psycho-Environmental Impact on Kindergarten and Primary Schools Teachers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, R. Biology fieldwork in schools and colleges in the UK: An analysis of empirical research from 1963 to 2009. J. Biol. Educ. 2010, 44, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Asunción, M.M.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Maiques, S. Transforming learning spaces on a budget: Action research and service-learning for co-creating sustainable spaces. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Jenkins, A.; Leach, J.; Roberts, C. Issues in Providing Learning Support for Disabled Students Undertaking Fieldwork and Related Activities; Geography Discipline Network: Gloucester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, E.; Bormpoudakis, D.; Tzanopoulos, J. Assessing challenges and opportunities for schools’ access to nature in England. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.M.; Chapman, N. Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyment, J.E. Green school grounds as sites for outdoor learning: Barriers and opportunities. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2005, 14, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk-Wesselius, J.E.; van den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D. Green Schoolyards as Outdoor Learning Environments: Barriers and Solutions as Experienced by Primary School Teachers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P.; Jensen, F.S.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. The extent and dissemination of udeskole in Danish schools. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov-Jessop, S. An Urban Jungle for the 21st Century. The New York Times, 28 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.S.M.; Atencio, M. Unpacking a place-based approach–“what lies beyond?” Insights drawn from teachers’ perceptions of outdoor education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 56, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atencio, M.; Tan, Y.S.M.; Ho, S.; Ching, C.T. The place and approach of outdoor learning within a holistic curricular agenda: Development of Singaporean outdoor education practice. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustam, B.; Daniel, E.S. Informal and formal environmental education infusion: Actions of malaysian teachers and parents among students in a polluted area. Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2016, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bentsen, P.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. Towards an understanding ofudeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Educ. 3-13 2009, 37, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkontelos, A.; Vaiopoulou, J.; Stamovlasis, D. Burnout of Greek Teachers: Measurement Invariance and Differences across Individual Characteristics. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysomalidou, A.; Takos, I.; Spiliotis, I.; Xofis, P. The participation of teachers in Greece in outdoor education activities and the schools’ perceptions of the benefits to students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.W.; Boyd, M.; Scott, L.; Colquhoun, D. Barriers to biological fieldwork: What really prevents teaching out of doors? J. Biol. Educ. 2015, 49, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; Haughton, C. The perception, management and performance of risk amongst Forest School educators. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 38, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.; Dickie, I. Learning in the Natural Environment: Review of Social and Economic Benefits and Barriers; NECR092; Natural England: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, S. Outdoor learning for children ged 2–11: Perceived barriers, potential solutions. In Proceedings of the 4th International Outdoor Education Conference “Outdoor Education Research and Theory: Critical Reflections, New Directions”, Victoria, Australia, 15–18 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock, G.R.; Zandvliet, D.B. Citizenship outcomes and place-based learning environments in an integrated environmental studies program. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, G.; Fandrem, H.; Dettweiler, U. Does “out” get you “in”? Education outside the classroom as a means of inclusion for students with immigrant backgrounds. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W. Early childhood environmental education: A systematic review of the research literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallner, P.; Kundi, M.; Arnberger, A.; Eder, R.; Allex, B.; Weitensfelder, L.; Hutter, H.P. Reloading Pupils’ Batteries: Impact of Green Spaces on Cognition and Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.T.; Kilmer, R.P.; Wang, C.; Cook, J.R.; Haber, M.G. Natural environments near schools: Potential benefits for socio-emotional and behavioral development in early childhood. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the MentalWell-Being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.F.; Zhou, J.; Fung, D.S.S.; Kua, P.H.J.; Huang, Y.X. Equine-assisted learning in youths at-risk for school or social failure. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1334430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.; Passy, R.; Gilchrist, M.; Hunt, A.; Blackwell, I. Natural Connections Demonstration Project, 2012-2016: Final Report; NECR215; Natural England: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, S.; Gray, T.; Ward, K. “Sowing and growing” life skills through garden-based learning to re-engage disengaged youth. Learn. Landsc. 2016, 10, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Esnaola, M.; Forns, J.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; López-Vicente, M.; Castro Pascual, M.; Su, J.; et al. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Senapati, A. Effect of sensory diet through outdoor play on functional behaviour in children with ADHD. Indian J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 46, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, S.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J.; Novakovic, E.G.; Burns, V.E. Introducing the use of a semi-structured video diary room to investigate students’ learning experiences during an outdoor adventure education groupwork skills course. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gallardo, J.R.; Verde, A.; Valdés, A. Garden-Based Learning: An Experience with “At Risk” Secondary Education Students. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 44, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, C.A. Perspective: Casting light on sleep deficiency. Nature 2013, 497, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, L.; Murray, R. Forest School and its impacts on young children: Case studies in Britain. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.F.; Kuo, F.; Sullivan, W.C. Views of nature and self-discipline: Evidence from inner city children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magntorn, O.; Helldén, G. Reading Nature-experienced teachers’ reflections on a teaching sequence in ecology: Implications for future teacher training. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2006, 2, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M.; LaFollette, S. Assessing the status of environmental education in Illinois elementary schools. Environ. Health Insights 2009, 3, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukma, E.; Ramadhan, S.; Indriyani, V. Integration of environmental education in elementary schools. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1481, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Underwood, C.; Wojciehowski, M.; Nayquonabe, T. Empathy Capacity-Building through a Community of Practice Approach: Exploring Perceived Impacts and Implications. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S.; Murfield, J.; Dillon, L.; Wilkin, A. Education Outside the Classroom: Research to Identify What Training Is Offered by Initial Teacher Training Institutions; National Foundation for Educational Research: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cárceles, J.O.; Fernández, G.E.A.; Fernández-Díaz, M.; Fernández, J.M.E. School gardens: Initial training of future primary school teachers and analysis of proposals. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, R.D.; Floyd, M.F.; Hammitt, W.E. Environmental socialization: Quantitative tests of the childhood play hypothesis. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, G.; Fenwick, A.; Lynch, J. Place-responsive pedagogy: Learning from teachers’ experiences of excursions in nature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 792–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.; Morris, M.; O’Donnell, L.; Reid, A.; Rickinson, M.; Scott, W. Engaging and Learning with the Outdoors: The Final Report of the Outdoor Classroom in a Rural Context Action Research Project; National Foundation for Education Research: Slough, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovich, A.; Miedijensky, S. From a guided teacher into leader: A three-stage professional development (TSPD) model for empowering teachers. High. Educ. Stud. 2019, 9, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amissah-Essel, S.; Hagan, J.E.; Schack, T. Assessing the Quality of Physical Environments of Early Childhood Schools within the Cape Coast Metropolis in Ghana Using a Sequential Explanatory Mixed-Methods Design. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 1158–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javornik, S.; Mirazchiyski, E.K. Factors Contributing to School Effectiveness: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2095–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S. Losing our way? The downward path for outdoor learning for children aged 2–11 years. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2010, 10, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Barnes, M.; Jordan, C. Do Experiences with Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, T.; Waters, J.; Clement, J. Child-initiated learning, the outdoor environment and the ‘underachieving’ child. Early Years 2013, 33, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenaj, Z.S.; Moshammer, H.; Berisha, M.; Weitensfelder, L. Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Question |

|---|---|

| School activities related to nature outside the school area | In the current school year, 2022–2023, how many opportunities will pupils at your school have to participate in school-organized visits to locations outside the school area (e.g., fieldwork, field trips, educational and teaching visits)? |

| Of these visits to locations outside the school area, how many will take place in natural settings where pupils can have direct contact with nature (e.g., nature reserves, national parks, forests, wetlands)? | |

| Of these visits to locations outside the school area, how many will take place in urban and peri-urban green sites where pupils still have direct contact with nature (e.g., gardens, parks)? | |

| Of these visits to locations outside the school area, how many will be at nature education sites where pupils can experience indirect contact with nature (e.g., zoos, museums, aquariums)? | |

| Nature and school activities related to nature within the school area | What kind of vegetation and how much vegetation does your school have? |

| In addition to visits to locations outside the school area, in what ways does your school provide opportunities for pupils to learn about or interact with nature? | |

| School activities in direct contact with nature | In your opinion, what factors might limit the number of visits organized by your school to places where pupils can have direct contact with nature? |

| What are the possible reasons that may limit the opportunities your school provides for pupils to interact directly with nature in the natural environment of the school area? | |

| With which activities does the direct contact of the pupils with nature take place during the outdoor activities of your school? | |

| How do you think pupils were affected during the school activities in direct contact with nature? | |

| Environmental Education Programs (EEPs) | In your opinion, what influences those teachers who show interest in implementing EEPs in your school? |

| How do you think the EEPs have helped the pupils at your school? | |

| It is a fact that a large part of teachers does not conduct EEPs. What do you think this is due to? |

| Factors Limiting School Visits to Places Where Direct Contact with Nature Can Be Practiced | School Categories | H/Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ lack of knowledge and training about outdoor learning environments | Primary-high schools | −41.900 | 0.023 |

| Primary-middle schools | −44.964 | 0.010 | |

| High-middle schools | 3.064 | 1.000 | |

| General-vocational high schools | −0.603 | 0.546 | |

| General-special education schools | −3.077 | 0.002 | |

| Teachers’ lack of familiarity with the natural environment | Primary-high schools | −26.212 | 0.280 |

| Primary-middle schools | −40.9 | 0.022 | |

| High-middle schools | 14.734 | 1.000 | |

| General-vocational high schools | 0.351 | 0.726 | |

| General-special education schools | −2.436 | 0.015 | |

| Lack of time to prepare and organize outdoor activities | Primary-middle schools | −62.434 | 0.000 |

| Primary-high schools | −79.051 | 0.000 | |

| Middle-high schools | −16.617 | 1.000 | |

| General-vocational high schools | −0.332 | 0.740 | |

| General-special education schools | −3.528 | 0.000 | |

| Lack of time to visit these places | Middle-primary schools | 7.978 | 1.000 |

| Middle-high schools | −87.974 | 0.000 | |

| Primary-high schools | −79.996 | 0.000 | |

| General-vocational high schools | 1.242 | 0.214 | |

| General-special education schools | −3.543 | 0.000 | |

| The demanding curriculum, which makes trips to nature a secondary priority | Middle-primary schools | 7.959 | 1.000 |

| Middle-high schools | −90.180 | 0.000 | |

| Primary-high schools | −82.221 | 0.000 | |

| General-vocational high schools | 2.457 | 0.014 | |

| General-special education schools | −4.522 | 0.000 | |

| Lack of budget to visit these places | Middle-primary schools | 2.231 | 0.328 |

| Middle-high schools | |||

| Primary-high schools | |||

| General-vocational high schools | −1.347 | 0.178 | |

| General-special education schools | 0.693 | 0.489 | |

| Concern for the health and safety of pupils | Middle-primary schools | 2.898 | 0.235 |

| Middle-high schools | |||

| Primary-high schools | |||

| General-vocational high schools | 0.824 | 0.410 | |

| General-special education schools | 0.705 | 0.481 | |

| Lack of suitable and accessible places to visit | Middle-primary schools | 2.066 | 0.356 |

| Middle-high schools | |||

| Primary-high schools | |||

| General-vocational high schools | 0.823 | 0.410 | |

| General-special education schools | 2.188 | 0.029 |

| Factors Limiting School Visits to Places of Direct Contact with Nature | Percentage of School Teachers Who Provide Outdoor Learning Opportunities for Pupils | Number of Visits to Natural Areas Where Pupils Can Have Direct Contact with Nature (e.g., Nature Reserves, National Parks, Forests, Wetlands) | Number of Visits to Urban and Peri-Urban Green Sites Where Pupils Still Have Direct Contact with Nature (e.g., Gardens, Parks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of time to visit these places | −0.144 ** | −0.045 | 0.012 |

| Lack of budget to visit these places | −0.004 | −0.101 * | −0.032 |

| Lack of suitable and accessible places to visit | −0.100 * | −0.148 ** | −0.074 |

| Concern for the health and safety of pupils | 0.021 | −0.005 | −0.044 |

| The demanding curriculum, which makes trips to nature a secondary priority | −0.215 ** | −0.091 * | −0.028 |

| Teachers’ lack of knowledge and training about outdoor learning environments | −0.313 ** | −0.120 ** | −0.075 |

| Teachers’ lack of familiarity with the natural environment | −0.342 ** | −0.109 * | −0.069 |

| Lack of time to prepare and organize outdoor activities | −0.302 ** | −0.119 ** | 0.007 |

| Factors That Limit the Opportunities That the School Provides to Pupils for Direct Interaction with Nature in the Natural Environment of the School Space | Percentage of School Teachers Who Provide Outdoor Learning Opportunities for Pupils | Frequency of Use, for Educational Activities, of the School’s Natural Environment Where Children Can Have Direct Contact with Nature |

|---|---|---|

| Teachers do not appreciate the value of the school’s natural environment | −0.291 ** | −0.171 ** |

| Teachers fear that during activities in the school’s natural environment, they will disturb other classes of pupils or be disturbed by pupils from other classes | −0.324 ** | −0.187 ** |

| Teachers feel they are exposed to being watched or surveilled | −0.255 ** | −0.149 ** |

| Teachers consider outdoor learning activities a waste of time | −0.406 ** | −0.198 ** |

| Factors Affecting Teachers’ Interest in EEPs | Teachers’ Interest in the Implementation of EEPs | |

|---|---|---|

| Factors that motivate teachers to implement EEPs | Personal interest in the environment | 0.139 ** |

| Awareness of the positive results of the EE | 0.218 ** | |

| Social contribution | 0.218 ** | |

| Social recognition | 0.066 | |

| Professional development | 0.023 | |

| Professional prestige | 0.103 * | |

| Factors that prevent teachers to implement EEPs | Lack of motivation | −0.108 * |

| Lack of training | −0.165 ** | |

| Lack of time | −0.101 * | |

| Lack of pupil safety | −0.007 | |

| Lack of educational material | 0.036 | |

| Lack of financial resources | 0.031 | |

| Lack of teacher self-confidence and experience | −0.226 ** | |

| Percentage of school teachers who provide outdoor learning opportunities for pupils | 0.418 ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chrysomalidou, A.; Takos, I.; Spiliotis, I.; Xofis, P. Factors That Influence the Teachers’ Involvement in Outdoor, Nature-Based Educational Activities and Environmental Education Programs. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010003

Chrysomalidou A, Takos I, Spiliotis I, Xofis P. Factors That Influence the Teachers’ Involvement in Outdoor, Nature-Based Educational Activities and Environmental Education Programs. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrysomalidou, Anastasia, Ioannis Takos, Ioannis Spiliotis, and Panteleimon Xofis. 2026. "Factors That Influence the Teachers’ Involvement in Outdoor, Nature-Based Educational Activities and Environmental Education Programs" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010003

APA StyleChrysomalidou, A., Takos, I., Spiliotis, I., & Xofis, P. (2026). Factors That Influence the Teachers’ Involvement in Outdoor, Nature-Based Educational Activities and Environmental Education Programs. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg7010003