Abstract

We quantified how exhibit design and routine management shape behavior and space use in captive harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). Using a species-specific ethogram, scan sampling and focal follows on adult females housed in a modern zoo exhibit, we estimated time budgets, mapped space use across depth-defined zones, and modeled behavior sequences as first-order transition networks. Locomotion dominated activity (swimming/active travel), with resting and enrichment-related behaviors next most frequent; social and play behaviors occurred at low but non-negligible rates. Seals showed clear depth preferences, concentrating active swimming in deeper zones and using liminal/shallow areas for rest. Transition graphs revealed stable, low-entropy loops (e.g., swim → turn/pace → swim) consistent with repetitive locomotor routines, while enrichment and feeding windows temporarily diversified sequences and increased exploration. Overall, integrating time budgets with Markov-style transition analysis and spatial heatmaps provides a compact welfare-oriented dashboard: it identifies where exhibit depth and refuge availability support positive behavioral diversity, flags repetitive cycles as targets for enrichment, and offers actionable metrics to evaluate husbandry changes over time.

1. Introduction

The survival of numerous animal and plant species is increasingly threatened by factors such as human population growth, habitat fragmentation, and the intensification of anthropogenic activities. In response to these pressures, biodiversity conservation—encompassing genetic, species, and ecosystem diversity—has become a globally recognized priority [1,2]. Conservation strategies are articulated through two complementary approaches: in situ conservation, which focuses on protecting and restoring natural habitats, and ex situ conservation, which is carried out in controlled environments such as zoological parks and wildlife centers. These institutions play a crucial role in safeguarding endangered species, preserving their genetic diversity, and, where possible, promoting their reintroduction into the wild [3,4].

Since the ratification of the Council Directive 1999/22/EC of 29 March 1999 (Relating to the Keeping of Wild Animals in Zoos), zoological institutions have assumed an increasingly central role in ex situ conservation programs [1]. Their mission has expanded to encompass educational, scientific, and managerial responsibilities, with a strong emphasis on animal welfare and public awareness.

Effective captive conservation therefore requires careful attention to the welfare of the individuals involved, understood not only in terms of physical health but also as the opportunity to express a full range of natural behaviors within an appropriate environmental context [5,6,7].

To this end, exhibit design should account for the species-specific needs of the animals, incorporating elements that simulate natural habitats and implementing environmental enrichment strategies that stimulate cognitive and behavioral capacities. An animal’s well-being, the adequacy of its environment and its overall health can be assessed by the presence of species-specific behaviors, similar to those observed in the wild [8]. For marine mammals in particular, enrichment programs can combine structural or environmental features (e.g., habitat complexity, refuges), occupational or feeding-based devices (e.g., puzzle feeders, variable feeding schedules), sensory stimuli, and social or cognitive challenges, all aimed at increasing behavioral diversity and promoting positive welfare states [9,10]. Such enrichment techniques have been shown to enhance behavioral diversity, reduce stereotypies, and promote positive interactions with the environment [9,10]. Moreover, behavioral studies conducted in controlled settings provide valuable ethological data that are often difficult to obtain in the wild, supporting improved animal management, exhibit design, and conservation practices [11].

Another critical aspect of managing animals under human care involves interactions with visitors, which can influence both behavioral and spatial dynamics in positive or negative ways. Several studies have shown that visitor numbers and the associated noise, as well as other anthropogenic activities such as construction work, can modify activity budgets, vigilance, social interactions, and enclosure use in zoo-housed animals [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Monitoring these interactions is therefore essential to ensure a balance between educational objectives, visitor experience, and animal welfare.

The harbor seal (Phoca vitulina L.), widely distributed along the coasts of the Northern Hemisphere, is a species that, although not currently endangered, faces multiple anthropogenic threats such as human disturbance, marine pollution, and habitat degradation. Although relatively few studies have focused on professionally managed harbor seals, available evidence indicates that both husbandry practices and visitor presence can markedly influence their behaviors under human care. In a wildlife rehabilitation setting, studies have shown that environmental enrichment reduced stereotypical behaviors and promoted the development of foraging skills in Eastern Pacific harbor seal pups (Phoca vitulina richardii), supporting the use of enrichment as a welfare tool in managed care [12]. In a zoo context, studies have reported that harbor seals submerged more frequently as visitor numbers increased, suggesting that crowd size can affect activity patterns and space use in this species [13,18]. The behavioral ecology of harbor seals in permanent, professionally managed settings remains comparatively understudied, particularly in terms of detailed time budgets and spatial use of exhibits, highlighting the need for further research to optimize management practices and enhance individual welfare.

Within this framework, the present study aims to analyze the behavior of a group of female harbor seals housed at Parco Faunistico Le Cornelle (Italy). The main objectives of the research are to:

- Evaluate the effect of environmental and social enrichment on individual and group behavior of harbor seals;

- Describe harbor seals’ daily patterns using time budget methodology;

- Characterize the spatial distribution patterns of individuals within the exhibit.

The results are expected to enhance our understanding of the behavior of Phoca vitulina in controlled environments, providing useful insights for developing evidence-based management strategies aimed at improving animal welfare and strengthening ex situ conservation programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group

The study was conducted on four captive-born female harbor seals (Phoca vitulina L.) housed at Parco Faunistico Le Cornelle (Valbrembo, Bergamo, Italy). Individual data for the study subjects are summarized in Table 1, while photographs of the individuals are provided in Figure 1. Among the four females currently housed in the park, Schizzo is the only individual that has reproduced, and the only one transferred from Northern Europe to the park in 2011. The other three females were born at Parco Faunistico Le Cornelle in 2017 and are paternal half-siblings, as they share the same sire.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the four study individuals. For each seal the table reports sex, date of birth, name, and year of arrival at the facility; all individuals are female.

Figure 1.

Individual photographs for photo-identification (A–D): (A) Schizzo; (B) Mohana; (C) Zoe; (D) Rhea.

2.2. Exhibit Description and Management Procedures

The facility is divided into two main sections: an outdoor area, which includes the main exhibit and a secondary pool, and an indoor area not accessible to the public.

The indoor section consists of a building containing an area for food preparation and water-quality monitoring. It also includes a small freshwater pool with a variable depth of 10–30 cm, always accessible to the seals. The indoor area is directly connected to the outdoor exhibit by a 7 m corridor equipped with a gate that remains open during park operating hours (9:00–17:00 in spring), allowing free movement of the animals between the two sections.

Each seal receives a diet consisting exclusively of fish (2–2.5 kg per day per individual, equivalent to approximately 3000 kcal), supplemented with specific nutritional additives.

The secondary pool, also not visible to the public, has a maximum depth of 1.2 m and is directly connected to the main exhibit through a gated corridor. It is frequently used by keepers to temporarily separate an individual from the group for veterinary examinations or training sessions.

The main exhibit includes both an aquatic and a terrestrial section.

The land area covers approximately 60 m2 and features a raised rocky structure extending about 7 m into the pool. The main pool occupies an area of about 130 m2, with a gradual slope and a maximum depth of 3 m on the western side. This side is bordered by glass panels that allow underwater viewing by visitors. Additional visibility is provided from the southern fence, which overlooks both the pool and the land area.

The transition zone between water and land serves as the feeding area, where meals are provided three times daily (09:30, 11:00, and 15:30) and last 5–7 min. During feeding, keepers simultaneously conduct behavioral training sessions using vocal commands and visual targets to elicit specific movements or responses, which are subsequently reinforced with food rewards.

Keepers also perform routine maintenance tasks and introduce environmental enrichment devices (floating or submerged objects, toys, or novel stimuli) in the water every 2–3 days to stimulate exploratory behavior and prevent habituation to enrichment stimuli.

2.3. Data Collection

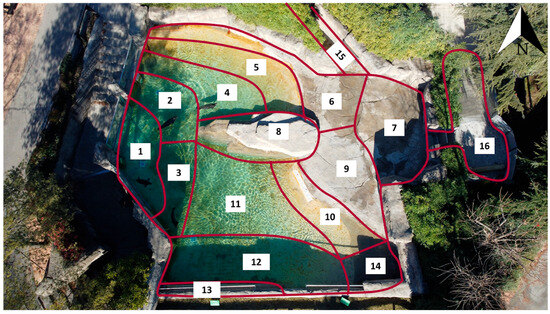

To facilitate spatial recording, the entire exhibit was mapped through aerial footage obtained using a DJI Mini 2 drone (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The area was then measured and divided into sixteen subareas, defined according to the presence of structural features and water depth (subareas 1–16).

A brief description of each subarea is provided in Table 2 and an aerial photo with labels is provided in Figure 2, from the deepest zones adjacent to the underwater windows (subareas 1–3) to the shallow “beach” areas (subareas 5, 10, 14) and the land sections (subareas 6–9), as well as the indoor facilities (subarea 15) and secondary pool (subarea 16).

Table 2.

Spatial zoning of the seal exhibit and functional descriptions. Sixteen subareas delineate depth gradients, emergent substrates, and functional areas of the main and secondary tanks: deep (subareas 1–3); gently sloping bottoms (4, 11); shallow “beach” transitions (5, 10, 14); emergent/terrestrial (6, 7, 9); raised central rock ledge (8); grate (13); indoor area and corridor (15); secondary tank and connecting corridor (16). Subareas were used to code animal location during behavioral observations; routine feeding occurred in subarea 10. Note: Cardinal directions are relative to the exhibit plan; “beach” denotes a shallow transition from water to land.

Figure 2.

Overhead view of the exhibit with a spatial partition into 16 subareas (1–16). Subarea boundaries are outlined in burgundy; the north arrow (top right) indicates map orientation. The numbering corresponds to the areas already defined in Table 2 and is used to code position during observations. The partition includes the main pool, the terrestrial (emergent) surfaces, and the secondary tank with the connecting corridor.

Behavioral observations were carried out using two standard methods: scan sampling and focal sampling [19,20,21].

Scan sampling consisted of systematic observations conducted at regular time intervals to record each individual’s behavioral state and environmental context [19]. Observations were carried out from 8 March to 4 April 2022, between 09:00 and 16:30, excluding feeding periods, with a sampling interval of 5 min. This protocol yielded an average of over 90 scans per day.

For each interval and individual, the following parameters were recorded:

- Position: subarea occupied at the time of observation.

- Behavioral microcategory: specific behavioral module observed.

- Behavioral macrocategory: general functional class of behavior.

During each scan, additional contextual variables were also noted:

- Meteorological conditions.

- Presence of keepers, feeding times, or enrichment events.

All scan data were entered into standardized recording sheets listing the behavioral microcategories and the spatial subdivision of the exhibit.

Focal sampling consisted of continuous observations of a single individual for a predefined period, during which all behavioral events were recorded in sequence [19,20]. In this study, focal sessions were conducted from 13 March to 1 April 2022, concurrently with scan sampling, between 09:00 and 16:30, with a break from 12:00 to 13:30. Each individual was observed in 15 min focal sessions, resulting in 6 h of observation per day (1 h 30 min per individual). To minimize time-related bias, the observation order of individuals was rotated daily so that each subject was monitored during different times of the day.

Behavioral data were collected simultaneously and independently by three trained researchers at predetermined sampling intervals. Each observer recorded behaviors using the same ethogram and data sheet. After data collection, the three datasets were compared and checked for inconsistencies; any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus to ensure accuracy and consistency of the observations. Formal inter-rater reliability statistics were not calculated, but this procedure was used to verify the correctness of data recording.

All data were recorded in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for subsequent behavioral and frequency analyses. Photographic and video recordings were collected throughout the study period for data validation and individual identification, using Canon EOS 1300D (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and EOS 1000D (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) cameras.

2.4. Data Analysis

Scan sampling data were entered into two dedicated Excel databases. Data organization was optimized using lookup functions (VLOOKUP), pivot tables, and charts to cross-reference specific and general behavioral categories. A “notes” column was used to include contextual information relevant for interpretation but not suitable for main tabulation. Data analysis produced several graphical outputs, including spatial-use maps and behavioral flow diagrams derived from transition matrices. Transition matrices were constructed from focal-sampling data by relating, for each individual, each behavioral microcategory to the immediately preceding one [22,23]. This allowed quantification of the total number of behavioral transitions during the observation period. Transitions were grouped into frequency classes: 1–20; 21–50; 51–100; 101–1000; >1000. Each frequency interval was represented with a distinct arrow thickness and color to visualize transition intensity in individual flow diagrams. These diagrams, produced using Rhinoceros software (v. 6.23; Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, WA, USA), were instrumental in outlining individual behavioral profiles and highlighting intra-group differences. Spatial-use maps were produced using Adobe Photoshop (v. 21.0; Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) based on the sixteen subareas. These allowed the analysis of both individual and group distribution and the frequency of use of each zone in relation to behavioral macrocategories.

Scan sampling data were filtered to correlate behavioral macrocategories (at both individual and group levels) with exhibit subareas. Both absolute and percentage values were considered, using two distinct scales:

- Absolute values: 0; 1–50; 51–200; 201–1000; >1000.

- Percentage values: 0%; 0.01–10%; 11–25%; 26–50%; >50%.

The same color coding was applied to both scales, differentiated according to the behavioral macrocategory analyzed. Six total graphs were produced for each macrocategory—two for the whole group (absolute and percentage) and four for individual seals (percentage scale).

3. Results

3.1. Ethogram

Behavioral categories were identified based partly on previously published ethograms [13,18] and primarily on direct field observations conducted during this study. The final behavioral repertoire comprised 16 microcategories grouped into five macrocategories: Interaction (I), Moving (M), Playing (PL), Resting (R), and Social Interaction (SI). The microcategories included, among others: interactions with keepers and visitors (I-K, I-V); locomotor patterns such as swimming at the surface with the head above water (SHAW), underwater swimming with the ventral side up (SUW-U) or down (SUW-D), and terrestrial locomotion (ML); play behaviors (PL-G, PL-E, PL-C, PL-SP); resting postures including ventral (R-D), dorsal (R-U), underwater (R-UW), and vertical (R-V) positions; and social interactions with conspecifics (SI-S) and the behavior termed “Shaking the Fin” (SI-SF). Part of the categorical framework was adapted from reference studies on harbor seals in controlled environments, while most categories were refined through direct observation of the study group. For subsequent analyses, the 16 behavioral microcategories were grouped into five broader modules (macrocategories) used to calculate time budgets. Table 3 lists the 16 microcategories, their abbreviations, corresponding general module, full behavioral description, and operational definitions. An additional category, “Out”, was included as both a micro- and macrocategory to indicate periods when the individual was out of view or not observable.

Table 3.

Ethogram of behaviors used in this study. Macro-categories—Interaction (I), Playing (PL), Resting (R), Moving (M), Social Interaction (SI), and Out (OUT)—are subdivided into micro-categories with full names and concise operational definitions. These codes were used for standardized data recording and subsequent analyses (focal/scan sampling). Abbreviations are expanded in the first column and definitions are self-contained to allow the table to stand alone.

3.2. Time Budget

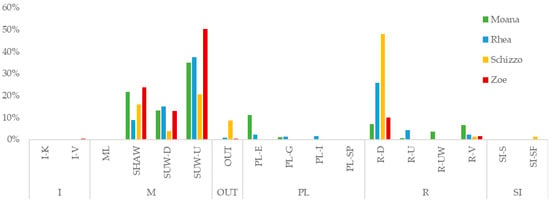

For each individual, the percentage of time spent performing each behavioral microcategory was calculated. Aggregated data show that the Moving category represented the predominant component of the seals’ time budget, accounting for approximately 65% of the total observation time. This was followed by Resting (28%), Playing (about 4.5%), and Interaction, Social Interaction, and OUT, which together represented around 3% of all recorded behaviors. However, when analyzed individually, marked differences emerged among subjects, with distinct behavioral profiles that remained stable over the observation period.

Zoe displayed a clear predominance of locomotor activity, with 87% of her time budget devoted to the Moving category. Within this, the most frequent behavior was underwater swimming with the ventral side up (SUW-U), which alone accounted for 50% of all observations. Other locomotor behaviors, including SUW-D and SHAW, comprised the remaining 37%. No terrestrial locomotion (ML) was observed, indicating an exclusively aquatic activity pattern. Affiliative and play behaviors were negligible, cumulatively representing about 1% of total behaviors. The Resting category made up about 12% of Zoe’s time budget, primarily R-D (ventral resting, 10%), followed by R-V (vertical resting, 1.5%), with minimal occurrences of R-U and R-UW.

Schizzo spent most of her time resting, with 50% of total observations belonging to the Resting category. Among these, ventral resting (R-D) was dominant (48%), while all other resting postures accounted for less than 2% combined. The Moving category represented a smaller proportion than in the other individuals (40.5%), including SUW-U = 21%, SHAW = 16%, SUW-D = 4%, and ML < 0.1%. Schizzo was the only individual to display the “Shaking the Fin” (SI-SF) behavior, which accounted for 1.22% of her total activity and occurred exclusively during inactive phases. Affiliative and play behaviors were negligible, cumulatively representing less than 2% of her behaviors. Additionally, Schizzo showed the highest rate of OUT events (9% of total time budget).

Mohana exhibited the greatest investment in play behavior, with 12% of her total time budget assigned to the Playing category. Of this, 11% was attributed to environmental play (PL-E), such as exploring surfaces or objects within the pool. Her locomotor repertoire was the most diverse, and she showed the second-highest proportion of movement overall (M = 70%). Frequent alternation was observed between SUW-U (35%), SUW-D (13%), and SHAW (22%), while terrestrial movement (ML) was absent. Resting behaviors were less frequent than in other individuals, accounting for 18% of her time budget.

Rhea displayed a more balanced behavioral profile between the Moving and Resting categories. The Moving category accounted for approximately 61% of her time, while Resting represented 32%. She was the only individual to perform PL-C behavior (interactive play), with a frequency of 1.58%. Rhea made extensive use of both underwater swimming modes (SUW-U 37%, SUW-D 15%), though with less alternation compared to Mohana. SI and I categories were present but limited (SI = 0.2%; I = 0.3%), and OUT behavior occurred in less than 1% of the total observed time. Figure 3 and Table S1 provide a summary of the breakdown of the time budget of the seal group divided by individual.

Figure 3.

Time budget by behavioral microcategory for the four individuals. Bars show the percentage of observation time allocated to each behavior for Mohana, Rhea, Schizzo, and Zoe. Along the x-axis, codes are grouped by macrocategory (I, M, OUT, PL, R, SI) following the ethogram (Table 3). In general, underwater swimming with belly up (SUW-U) is the predominant behavior for Moana and Rhea; Schizzo devotes a large share to resting with belly down (R-D); Zoe shows a more heterogeneous distribution with notable contributions in SHAW and PL-E. The OUT category is minor for most subjects. Full code definitions are provided in Table 3.

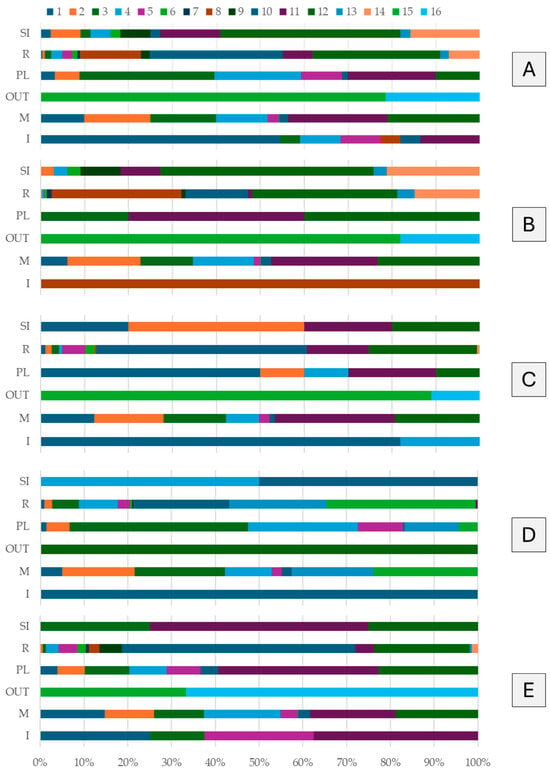

3.3. Spatial Distribution of Behaviors

The analysis confirmed a highly selective use of the habitat, with clearly defined patterns in the spatial distribution of behaviors.

On a cumulative basis, over 40% of all observations were concentrated in the deeper central zones (subareas 11 and 12). Among these, subarea 12 was the most frequently used (≈22% of total observations), followed by subarea 11 (≈18%). An additional 38% of activities occurred in intermediate zones (1–4), particularly in subareas 2 and 3, each accounting for more than 10% of all records. In contrast, peripheral and less structured subareas (6, 7, 9, 13–16) were used only occasionally, with frequencies per area always below 3% (≈6% combined). These results indicate that the seals tended to favor certain portions of the exhibit—specifically, the central and mid-depth sections—while avoiding peripheral or less structured zones. Different behavioral categories also exhibited distinct spatial patterns. Moving behaviors occurred in the deeper open-water subareas (11 and 12), which together accounted for approximately 44% of all locomotor events. Resting behaviors were concentrated in the few suitable haul-out or resting subareas (10, 12, and 8), which together comprised about 75% of all resting events. Playing behaviors, although globally rare (≈5% of all recorded behaviors), were exclusively distributed between shallow-water and beach areas, occurring primarily in subareas 3, 4, and 11 (≈70% of all play observations). Social interactions between conspecifics (SI) and interactions with visitors or keepers (I) were extremely rare (both <1% of total observations) and did not significantly alter the overall spatial-use patterns.

Regarding individual patterns:

Schizzo showed a clear preference for the most secluded and deeper areas. She used subarea 12 more than any other seal, particularly for resting behaviors. In the Moving category, approximately 24% of her locomotor events occurred in subarea 11 and 23% in subarea 12, followed by subareas 2, 4, and 3 (≈42% combined). For Resting, Schizzo avoided the main beach area, resting mostly in subarea 12 (≈33% of her resting events) and subarea 8 (≈30%), both distant from the water’s edge. Only 14% of her resting events occurred in subarea 10 (main beach), much less than in the other individuals. Play behavior was extremely limited (only five total events), all in water: two in subarea 11, two in subarea 12, and one in subarea 3. Schizzo was also the only seal to display the “Shaking the Fin” (SI-SF) behavior, observed in subarea 12. In total, she performed 16 social interactions, half (48%) occurring in subarea 12. Interactions with visitors or keepers were absent—only one event was recorded (her sole Interaction observation), which took place in subarea 8 during contact with a keeper.

Zoe, one of the most active individuals, used space in a more exposed manner compared to Schizzo. During swimming activity, Zoe favored subarea 11 (≈27% of her Moving events), followed by subarea 12 (≈19%), and subareas 2 (16%), 3 (14%), and 1 (12%). This pattern suggests that Zoe regularly explored both the deeper central sections and areas closer to the viewing window or entrance (1–3). For Resting, Zoe primarily used the main haul-out area, with subarea 10 alone accounting for half of her resting events (47.9%). She also rested in water: ≈25% of resting in subarea 12 and ≈14% in subarea 11. Unlike Schizzo, Zoe frequently hauled out on the beach even in the presence of visitors. Her play behavior was rare (about five total events) but concentrated in subarea 1 (≈50% of all play events), close to the public viewing window—indicating play triggered by visual or object stimuli. Social behaviors were minimal (five total SI-S events: two in subarea 2, and the others in subareas 1, 11, and 12), confirming limited affiliative tendencies. Conversely, Zoe was the individual that interacted most frequently with visitors or keepers (11 Interaction events), mostly near the glass panels in subarea 1 (≈82% of her interactions), and occasionally in subarea 4.

Mohana exhibited an intermediate space-use pattern with some clear preferences. During Moving, she most often used subarea 12 (≈24% of her locomotor events), but unlike the others, she also favored subarea 3 (≈21%), a mid-depth zone. Other frequently used subareas included 11 (19%) and 2 (17%), indicating alternation between deeper and nearshore zones. For Resting, Mohana displayed a balanced use of both aquatic and terrestrial areas: subarea 12 (34%), 11 (22%), and 10 (22%) were used with similar frequency. Thus, Mohana rested both in deep water and on the main beach without a marked preference. Among all individuals, Mohana devoted the highest proportion of time to Playing. Although play events were few, she was the only seal observed playing in all aquatic and shallow areas. Her play behaviors occurred in subareas 3 (41%) and 4 (25%), i.e., in shallow nearshore waters, with some episodes in 11 (12%) and 5 (10%). Social interactions were absent (two total SI-S events, one in subarea 4 and one in subarea 10), indicating limited engagement with conspecifics. Interactions with visitors were also rare, limited to two cases (occasional approaches in subareas 1 and 10).

Rhea showed a versatile spatial-use pattern, distributing her activities across all available subareas. In the Moving category, no single area dominated: subareas 11 (20%), 12 (19%), and 4 (18%) were most frequently used, followed by 1 (15%), 3 (11%), and 2 (11%). This indicates that Rhea regularly explored both the central deep-water areas and the perimeter zones without strong preferences. In contrast, her Resting behavior showed a clear preference for the main haul-out area (subarea 10), where more than half of all resting events occurred (53%). Subarea 12 was her second most used resting zone (22%), while all other areas were marginally used for resting. Like Zoe, Rhea preferred to haul out on the exposed beach rather than resting underwater. Although rare, her play events occurred in deeper water: subarea 11 accounted for about 37% of her total play events, followed by subarea 12 (23%). Rhea was also the only seal to exhibit the play microcategory PL-C, observed exclusively in her. Despite the low frequency, Rhea showed slightly more social behavior than the others, with four total SI events (two in subarea 11, one in 3, and one in 12). She also engaged more frequently with visitors than Schizzo or Mohana, with eight Interaction events—mostly in subarea 11 (3 events, 37%) and subarea 1 and 5 (2 events each, ≈25%), suggesting both approach behaviors near the viewing glass and possible contact during keeper sessions. Figure 4 and Table S2 provide a summary of the spatial analysis and temporal balance for the group under examination.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of behavioral macrocategories across the 16 subareas. For each macrocategory—Interaction (I), Moving (M), Out of view (OUT), Playing (PL), Resting (R), Social Interaction (SI)—the stacked horizontal bar shows the percentage of events/time for that macrocategory occurring in each subarea 1–16; each row sums to 100%. Panels: (A) overall (all individuals), (B) Schizzo, (C) Zoe, (D) Mohana, (E) Rhea. Colors map to subareas as indicated in the legend. Subarea definitions are provided in Table 2, and the exhibit layout is shown in Figure 2.

3.4. Transition Matrices

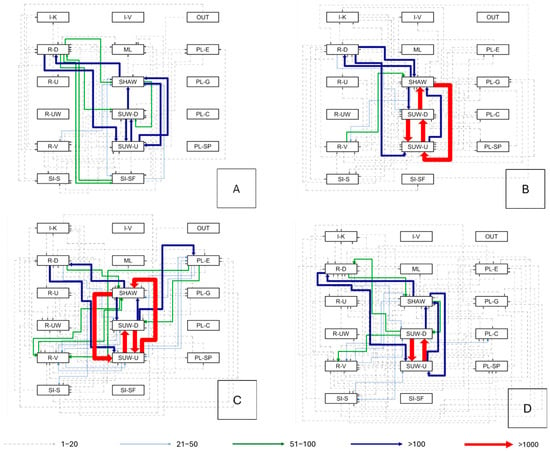

To evaluate behavioral sequence patterns, a transition matrix was calculated for each individual, documenting the number of times a given behavioral module (“trigger”) was immediately followed by another. This approach allows the identification of the most recurrent succession patterns among behavioral microcategories. On average, more than 70% of all transitions involved swimming cycles that included the microcategories SUW-U, SUW-D, and SHAW. Table S3 provides percentages of every transition made by the whole group.

For Schizzo, with a total of 4043 observed transitions, the most frequent sequences were almost symmetrical between SHAW and SUW-U: 21.17% of transitions occurred from SHAW to SUW-U, while 21.27% occurred in the opposite direction (SUW-U → SHAW). The SUW-D → SHAW sequence accounted for an additional 8.83%, followed by transitions where the ventral resting behavior (R-D) evolved into SUW-U (5.37%). Schizzo was the only individual exhibiting direct transitions between R-D and the microcategory SI-SF (“shaking the fin” during rest), suggesting an individual-specific expression of restlessness during inactivity. The transition matrix of Schizzo can be seen in Figure 5A and Table S4 provides percentages of every transition made by Schizzo.

Figure 5.

Transition networks among behavioral micro-categories (panels (A–D)). Each node denotes a behavior from the ethogram; directed arrows link the behavior at time t (source) to the next observed behavior (target). Arrow width and color encode transition frequency per legend: dashed grey = 1–20, light blue = 21–50, green = 51–100, dark blue = >100, red = >1000. Nodes are arranged by macrocategory (I, M, OUT, PL, R, SI). Panels: (A) Schizzo, (B) Zoe, (C) Mohana, (D) Rhea. Dashed links mark low-frequency transitions; red arrows highlight dominant pathways. Node labels follow the codes in Table 3; OUT denotes “out of view”.

Zoe, with 10,009 transitions, showed a repertoire dominated by alternations between the two types of underwater swimming: SUW-U and SUW-D followed each other in over 46% of all sequences. Moreover, the transitions SHAW → SUW-U and SUW-U → SHAW each reached 19.86%, while transitions from resting modules to swimming were extremely rare. These data confirm that Zoe displayed a strong tendency to maintain a continuous cycle between underwater swimming and fin movements, with few interruptions. The transition matrix of Zoe can be seen in Figure 5B and Table S5 provides percentages of every transition made by Zoe.

Mohana recorded 8557 total transitions. Alternations between SUW-U and SUW-D represented approximately 32% of the total, while the SHAW ↔ SUW-U sequences accounted for another 18%. A distinctive feature of Mohana’s matrix was the presence of transitions initiated by PL-E (play with exhibit elements): this microcategory originated about 235 transitions, which most often proceeded toward SUW-D, R-V, or SUW-U, indicating an exploratory behavioral pathway alternating between play and movement. The transition matrix of Mohana can be seen in Figure 5C and Table S6 provides percentages of every transition made by Mohana.

For Rhea, with 7443 transitions, the matrix revealed a more balanced distribution of sequences. Alternations between SUW-U and SUW-D comprised over half of all transitions, while 12.66% occurred from SUW-D to SHAW, and about 5% from SHAW to R-D, suggesting that fin agitation was often followed by a resting phase. Another distinctive feature of Rhea’s profile was the high number of transitions triggered by PL-G (playing with enrichment objects), which differentiated her from the other individuals.

Overall, the recurring patterns SUW-U ↔ SUW-D, SHAW ↔ SUW-U, and SUW-D → SHAW were shared across all seals and collectively represented 80% of all recorded transitions. This convergence highlights the strong repetitiveness of swimming sequences within the controlled habitat—an aspect that, in the absence of variable stimuli or foraging activities, could potentially develop into motor stereotypies. The transition matrix of Rhea can be seen in Figure 5D and Table S7 provides percentages of every transition made by Rhea.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethogram

The ethogram used in this study integrates consolidated taxonomies for P. vitulina [13,18] with additional microcategories derived from direct observation, maintaining continuity with the literature while enhancing descriptive resolution. In particular, the subdivision of Moving into SUW-U, SUW-D, and SHAW allows discrimination between functionally distinct locomotor patterns (dorsal/ventral underwater swimming vs. surface swimming), in accordance with published ethograms for common seals and other pinnipeds in zoological or experimental settings.

The explicit inclusion of categories for Resting (R-D, R-U, R-UW, R-V) and Social Interaction (SI-S) situates the behavioral repertoire within validated, comparable frameworks, facilitating time-budget and sequence analyses. Two classificatory decisions deserve methodological attention. First, including Shaking the Fin (SI-SF) as a microcategory enables the detection of a brief but potentially informative motor signal related to affective or attentional state—often overlooked in broader ethograms. Second, defining Resting Underwater (R-UW) distinguishes submerged rest from surface or vertical postures, a useful feature for both spatial-use analyses and physiological inference. Such refinements are particularly relevant in controlled environments, where repetitive behavioral sequences and visitor effects can modulate activity profiles, as previously demonstrated for common seals in zoo and aquarium contexts [18].

The ethogram’s architecture also functions as an interpretive bridge toward the welfare and enrichment literature. The subdivision of play behaviors (PL-E, PL-G, PL-C, PL-SP) allows correlations between variation in play repertoire and specific environmental interventions shown to reduce stereotypies and promote functional behaviors (e.g., development of foraging skills in rehabilitated pups; reduction in repetitive swimming through enrichment devices such as Artificial Kelp and Horse KONG™) [12,24]. Similarly, the refined swim categories facilitate detection of repetitive motor cycles (SUW-U/SUW-D/SHAW) that are sensitive to environmental complexity manipulations.

Finally, the inclusion of Interaction categories with keepers (I-K) and visitors (I-V), along with the OUT class (out of view), renders the ethogram sensitive to anthropogenic and visibility-related factors. This allows comparison with studies on visitor effects, where the intensity and predictability of human presence can yield negative, neutral, or positive outcomes, and permits a nuanced interpretation of avoidance or concealment (OUT) as situational responses. Overall, the proposed ethogram balances comparability with existing studies [25] and the ability to capture contextual subtleties typical of managed habitats.

4.2. Time Budget

In the dataset analyzed, the seals devoted on average approximately 65% of observed time to Moving, 28% to Resting, 5% to Playing, and less than 3% to social or human interactions and OUT periods combined. This pattern aligns with data reported for captive pinnipeds, where locomotion (random or group swimming) typically dominates the activity budget [14,26]; for instance, in one aquarium study, random and group swimming accounted for ~67% of observed time, with exploration comprising ~4% [26,27]. In the wild, time budgets are more evenly distributed among foraging, movement, and resting. Telemetry-based studies of P. vitulina show substantial proportions of time devoted to foraging and resting both at the surface and underwater—contrasting with the “locomotion-heavy” profiles seen in captivity [14,28]. This suggests that the absence of active hunting and the structural constraints of managed environments promote repetitive swimming cycles and predictable transitions among microcategories (SUW-U, SUW-D, SHAW) [12,24,26,27]. The low incidence of play and social behaviors in our sample is consistent with research showing that environmental complexity and foraging opportunities modulate behavioral diversity. Experimental studies on rehabilitating P. vitulina have shown that targeted enrichment reduces stereotypy and facilitates autonomous feeding skill acquisition (statistically suggestive trends, p ≈ 0.06–0.09) [12], while devices such as Artificial Kelp and Horse KONG™ significantly reduce the probability of exhibiting stereotypic behaviors in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) and grey seals (Halichoeurs grypus) [24,26]. Similar conclusions have been drawn across zoo and rehabilitation settings, where environmental enrichment for harbor seals and other pinnipeds consistently decreases stereotypic “pattern swimming” and increases exploratory or foraging-related behavior, supporting its use as a practical tool to improve welfare in managed environments [12,24,26,27,29]. These findings support the interpretation that a low-complexity environment promotes investment in repetitive swimming at the expense of play or exploration. Interactions with visitors and keepers represented <0.5% of all observations. The literature on the visitor effect reports heterogeneous outcomes—negative, neutral, or positive—depending on species, exhibit design, and the intensity or unpredictability of stimuli. Loud noises or sudden movements can be perceived as threats, eliciting avoidance and reduced visibility [25]. The limited frequency observed here suggests that contact with humans was confined to feeding and training sessions, without altering the structure of the time budget.

4.3. Spatial Use

Overall, the seals exhibited non-random use of their exhibit, concentrating activities in specific key subareas while neglecting others. This indicates that habitat features—such as water depth, shelter availability, and proximity to the public—strongly influenced spatial choices. The marked preference for subareas 11 and 12 confirms the importance of deep, open-water zones for swimming: in these subareas, seals performed most Moving behaviors, displaying repetitive underwater swimming patterns. This reflects the species’ natural ecology—common seals spend extended periods offshore, diving to depths of up to 500 m and covering tens of kilometers before returning to shore to rest after foraging [28,30,31]. In captivity, prolonged swimming sequences interspersed with brief resting bouts may echo an innate foraging drive expressed in a spatially constrained context. The near-stereotyped repetition of swimming cycles, with fixed dive–surfacing sequences and limited variability, could indicate frustration or boredom linked to spatial restriction. This potential motor stereotypy is well documented in captive marine mammals deprived of sufficient environmental stimulation. Prior research on pinniped welfare has shown that targeted environmental enrichments can reduce stereotypic behavior and promote more varied, natural patterns [12]. Introducing prey-like objects or novel sensory stimuli could therefore disrupt the monotony of repetitive swimming and encourage seals to explore underused exhibit zones.

Resting areas also proved crucial and highly selective: subarea 10 (the main haul-out beach connected to the water) was the preferred resting site, especially for captive-born individuals (Zoe, Rhea, Mohana). This aligns with the ecological needs of common seals, which require dry haul-out sites for thermoregulation, sleep, and digestion [32,33]. In nature, they select quiet beaches or rocky outcrops, often returning faithfully to the same sites [33]. In our study, Zoe and Rhea made extensive use of the exposed beach, suggesting it was perceived as both comfortable and safe. In contrast, Schizzo preferred to rest in water (subarea 12) or on secondary platforms (subarea 8), avoiding the main beach. This may reflect individual (age, social rank, temperament) or environmental (perceived disturbance) factors. As the oldest and the only individual not born at Parco Faunistico Le Cornelle, Schizzo sought more secluded, shaded resting zones. Subarea 12, distant from viewing windows and visitor traffic, offered greater privacy; indeed, Schizzo was most frequently observed resting there, while resting events near public-facing areas (subareas 1–3) were almost absent. This suggests that visitor presence can influence resting site selection: Schizzo avoided visual and acoustic exposure, whereas younger, captive-born seals appeared more tolerant of human presence. The “visitor effect” is known to vary among species and individuals, with visitors exerting negative, neutral, or even positive behavioral influences [25]. One study reported that P. vitulina spent more time underwater as visitor numbers increased [18], interpreted as potential avoidance behavior. Our observations of Schizzo—showing increased use of concealed areas—align with this pattern. Conversely, captive-born individuals (Zoe, Rhea, Mohana) appeared habituated to human presence; Zoe even displayed proactive interactions with visitors. No seal showed overt signs of acute stress in the presence of visitors (e.g., alarm vocalizations or flight responses). However, differentiated spatial choices indicate that for some individuals (e.g., Schizzo), continuous visual exposure may be undesirable and thus avoided. Play, social interaction, and human interaction behaviors provide further insight into individual personality and group dynamics. Play was rare and restricted to a few locations (shallow water and pool edges). This reflects both limited social or competitive stimulation (as P. vitulina is not highly social outside the breeding season) and the absence of stimulating objects or partners. Social species such as otariids or dolphins exhibit more frequent, interactive play, whereas the seals here—being solitary—engaged in individual play (e.g., PL-C, PL-SP) [34,35,36]. Younger seals, Mohana and Rhea, played slightly more; notably, Rhea exhibited PL-C, a behavior absent in others, consistent with her greater sociability. Schizzo, conversely, remained the least social member of the group, rarely interacting with conspecifics or staff. Zoe and Mohana showed intermediate levels. The overall scarcity of Social Interaction (<1% of total behaviors) is unsurprising given that P. vitulina is only aggregative under specific conditions (molting, breeding, mother–pup bonding). In captivity, the absence of competition for food or territory further reduces social motivation, explaining why most interactions were brief contacts or even defensive postures—such as Schizzo’s fin-shaking to keep others at a distance. This previously undescribed behavior may signal irritation or mild agitation, possibly linked to feeding anticipation or spatial defense. Interactions with visitors or keepers were rare but revealed consistent individual differences. Zoe, born and raised in captivity, was the most interactive, often swimming near the viewing glass, particularly during feeding or when prompted by keepers. This likely reflects a positive association between humans and food/training. Rhea showed mild interest, more focused on conspecifics than visitors; Mohana was largely indifferent; Schizzo actively avoided human contact. These differences reflect distinct temperaments—some individuals perceive humans as sources of stimulation or curiosity, while others as neutral or mildly stressful. In this sense, the stable individual patterns observed here are compatible with the broader concept of animal personality, in which shy-bold or proactive-reactive axes have been described for zoo mammals and, more recently, for pinnipeds [37,38,39]. From a welfare perspective, recognizing and accommodating such personality-like differences is important, because individuals with different temperaments may vary in how they experience and cope with visitor presence, exhibit design and enrichment [37,38]. Long-term studies indicate that visitors have minimal negative effects on seals and sea lions [25], yet subtle behavioral variations like those observed here merit attention from a welfare perspective. Schizzo’s ability to retreat to hidden areas (subarea 12) likely mitigates potential stress, under-scoring the importance of ethologically informed exhibit design: providing visual refuges, diverse enrichment opportunities, and options for both social interaction and voluntary isolation help each individual express its behavioral and psychological needs.

Recent studies on rehabilitating P. vitulina pups have shown that regular exposure to stimuli and enrichment reduces stereotypies and promotes natural behaviors, improving foraging competence and adaptability [12]. Accordingly, management interventions could enhance welfare by increasing environmental complexity in underused zones (subareas 6, 7, 9, 13–16) through the addition of play devices, scents, or hidden food, thereby balancing spatial use within the habitat.

4.4. Transition Matrices

The transition matrices revealed a highly ritualized behavioral structure in which over 70% of successions involved the triad SUW-U ↔ SUW-D ↔ SHAW. This “swimming cycle” describes repeated alternations between dorsal and ventral underwater swimming and brief surface intervals, suggesting that the absence of active foraging sustains a low-entropy (highly predictable) locomotor pattern. Similar reductions in exploratory variability and increases in “pattern swimming” have been reported for P. vitulina and Halichoerus grypus in captivity prior to enrichment, with exploratory behaviors increasing and stereotypies decreasing afterward [24]. The limited frequency of transitions from this motor cycle to resting or play modules indicates low behavioral permeability—once initiated, the cycle tends to self-sustain. In the literature, such sequential rigidity is interpreted as a consequence of environments with few variable or goal-directed stimuli and is often classified as motor stereotypy (pattern swimming/pacing) in pinnipeds. These behaviors can be mitigated through enrichments introducing manipulability and controlled unpredictability (e.g., Artificial Kelp, Horse KONG™), with significant effects on reducing repetition and disengagement from caregiver orientation [24,26]. Individual-specific transitions—for example, R-D ↔ SI-SF observed only in Schizzo—may represent “sequence signatures,” compatible with forms of restlessness during inactivity. Similar micro-patterns have been described in studies of visitor effects, where high or unpredictable acoustic/visual loads can shift sequences from resting states to motor-control chains (e.g., fin agitation or re-engagement in swimming) before behavioral homeostasis is restored [25]. Overall, our transition matrices align with evidence that P. vitulina in captivity exhibits simplified behavioral sequence structures in low-variability environments, whereas enriched scenarios increase transition diversity and promote shifts toward exploratory and play modules.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the behavioral profile observed was dominated by a highly predictable motor cycle (SUW-U ↔ SUW-D ↔ SHAW), with locomotion strongly prevailing in the time budget, resting occupying a smaller but consistent portion, and play and interactions remaining rare. This is consistent with previous reports for captive pinnipeds, where repetitive swimming patterns often emerge in the absence of ecological challenges such as real foraging. These patterns are among the most documented repetitive behaviors in captive marine mammals and are sensitive to the quality and diversity of enrichment provided [29]. Spatial use was markedly non-random: seals concentrated swimming in the deeper, open-water subareas (11–12), while haul-out behavior occurred mainly on the exposed beach (10). Individual differences were evident: the most human-sensitive seal (Schizzo) preferred sheltered, out-of-sight areas, suggesting that visual exposure to the public is not uniformly tolerated. This aligns with the “visitor effect” framework, where human presence can yield negative, neutral, or positive responses depending on species, individual traits, and exhibit design [25]. Our findings support this interpretation and recommend exhibit designs that offer visual escape routes and buffer zones for all individuals. The transition matrices confirmed low permeability from the swimming cycle to play or resting modules: once engaged, locomotor sequences tend to self-perpetuate. Literature indicates that structured, manipulable enrichments significantly reduce repetitive behaviors and increase exploration and behavioral variability, altering both time budgets and sequence topology [24]. Therefore, management strategies should include measurable, targeted interventions:

- Increase the complexity of underused subareas by introducing foraging tasks and sensory stimuli to redistribute space use;

- Provide permanent acoustic and visual refuges for more sensitive individuals while monitoring visitor density/noise alongside behavioral changes;

- Schedule temporally contingent enrichments (before/after feeding, during peak visitor hours) to maximize behavioral switching from repetitive swimming to exploratory states.

Recent evidence on P. vitulina and other pinnipeds shows that combining puzzle feeders, artificial kelp, and rotational toys enhances exploration and reduces pattern swimming during enrichment periods [27]. Overall, integrating a high-resolution ethogram, time-budget analysis, spatial-use mapping, and transition matrices offers an operational framework for decision-making: identifying where to intervene (underused zones), which enrichment devices to use (those with proven efficacy), and when to implement them (peak visitor periods), while respecting individual differences. This approach shifts the focus from basic wellness to quality of well-being, incorporating emotional state, environmental control, and behavioral variability as explicit welfare objectives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jzbg6040064/s1, Table S1. Global percentages of behavioral modules; Table S2. Percentage distribution of behaviors by subarea; Table S3. Overall transition matrix among behavioral microcategories; Table S4. Individual transition matrix (Schizzo); Table S5. Individual transition matrix (Zoe); Table S6. Individual transition matrix (Mohana); Table S7. Individual transition matrix (Rhea); Figure S1. Photographic exemplars of behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., V.R. and R.C.; methodology, E.S., G.G., F.L.L. and R.C.; formal analysis, M.B., C.C. and G.G.; investigation, M.B., P.C. and R.C.; resources, E.S. and V.R.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, P.C., G.G., F.L.L., V.R., R.C. and E.S.; supervision, E.S., V.R. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval was not required as there was no physical interaction with the study subjects. Behavioral observations of the seals occurred at a safe distance outside the exhibit and the subjects were free to move and interact without any alteration or manipulation by the researchers.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to restrictions, e.g., privacy or ethical.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/convention/text/default.shtml (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Wilson, E.O.; Peter, F.M. (Eds.) Biodiversity; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-309-03783-9. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 489–490. [CrossRef]

- Conde, D.A.; Flesness, N.; Colchero, F.; Jones, O.R.; Scheuerlein, A. An Emerging Role of Zoos to Conserve Biodiversity. Science 2011, 331, 1390–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosey, G.; Melfi, V.; Pankhurst, S. Zoo Animals: Behaviour, Management and Welfare; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-969352-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sueur, C.; Pelé, M. Importance of Living Environment for the Welfare of Captive Animals: Behaviours and Enrichment. In Animal Welfare: From Science to Law; La Fondation Droit Animal, Éthique et Sciences (LFDA): Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensohn, S.; Shotton, J.; Bowley, H.; Davies, S.; Thompson, S.; Justice, W.S.M. Assessment of Welfare in Zoo Animals: Towards Optimum Quality of Life. Animals 2018, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcphee, M.; Carlstead, K. The Importance of Maintaining Natural Behaviors in Captive Mammals. In Wild Mammals in Captivity: Principles and Techniques for Zoo Management, 2nd ed.; Kleiman, D.G., Thompson, K.V., Baer, C.K., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 303–313. ISBN 978-0226440101. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G.; Clubb, R.; Latham, N.; Vickery, S. Why and How We Use Environmental Enrichment to Tackle Stereotypic Behaviour? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makecha, R.N.; Highfill, L.E. Environmental Enrichment, Marine Mammals, and Animal Welfare: A Brief Review. Aquat. Mamm. 2018, 44, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G. Visitors’ Effects on the Welfare of Animals in the Zoo: A Review. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. JAAWS 2007, 10, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudeau, K.; Johnson, S.; Caine, N. Enrichment Reduces Stereotypical Behaviors and Improves Foraging Development in Rehabilitating Eastern Pacific Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina richardii). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 219, 104830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, A.; Stevens, J.; Vervaecke, H. The Short and Long Term Effects of Visitor Numbers on the Behaviour of a Group of Captive Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina). In Proceedings of the BIAZA Research Symposium, Hull, UK, 15–16 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.J.F. Activity Budgets: Analysis of Seal Behaviour at Sea; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Quadros, S.; Goulart, V.D.L.; Passos, L.; Vecci, M.A.M.; Young, R.J. Zoo Visitor Effect on Mammal Behaviour: Does Noise Matter? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.; Sullivan, M. The Visitor Effect in Zoo-Housed Apes: The Variable Effect on Behaviour of Visitor Number and Noise. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2020, 8, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob-Hoff, R.; Kingan, M.; Fenemore, C.; Schmid, G.; Cockrem, J.F.; Crackle, A.; Van Bemmel, E.; Connor, R.; Descovich, K. Potential Impact of Construction Noise on Selected Zoo Animals. Animals 2019, 9, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.; Thyssen, A.; Laevens, H.; Vervaecke, H. The Influence of Zoo Visitor Numbers on the Behaviour of Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina). J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2013, 1, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, J. Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, M.; Martin, P. Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-108-77646-2. [Google Scholar]

- Carpino, C.; Castiglioni, R.; Sacchet, E.; Milesi, A.; Marano, L.; Leonetti, F.L.; Romano, V.; Giglio, G.; Sperone, E. Behavioral and Spatial Analysis of a Symphalangus Syndactylus Pair in a Controlled Environment. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril-García, E.E.; Hoyos-Padilla, E.M.; Micarelli, P.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Sperone, E. Behavioural Responses of White Sharks to Specific Baits during Cage Diving Ecotourism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabietti, Y.; Spadaro, C.; Tigani, A.; Giglio, G.; Barbuto, G.; Romano, V.; Fedele, G.; Leonetti, F.L.; Venanzi, E.; Barba, C.; et al. Surface Behaviours of Humpback Whale Megaptera Novaeangliae at Nosy Be (Madagascar). Biology 2024, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, K.; Benedetti, A.; Goulart, V.D.L.R.; Deming, A.; Nollens, H.; Stafford, G.; Brando, S. Environmental Enrichment Devices Are Safe and Effective at Reducing Undesirable Behaviors in California Sea Lions and Northern Elephant Seals during Rehabilitation. Animals 2023, 13, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwen, S.L.; Hemsworth, P.H. The Visitor Effect on Zoo Animals: Implications and Opportunities for Zoo Animal Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.; Bay, M.; Martin, M.; Hatfield, J. Behavioral Effects of Environmental Enrichment on Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina concolor) and Gray Seals (Halichoerus grypus). Zoo Biol. 2002, 21, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J.; Bell, A.; Wilson, S.; Cuculescu, M. The Impact of Puzzle Feeders, Ice-Pops and Artificial Seaweed on Captive Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina) Behaviour. BioShorts 2024, 1, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, H.M.; Hooker, S.K.; Mikkelsen, L.; Van Neer, A.; Teilmann, J.; Siebert, U.; Johnson, M. Drivers and Constraints on Offshore Foraging in Harbour Seals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F.E. Marine Mammal Cognition and Captive Care: A Proposal for Cognitive Enrichment in Zoos and Aquariums. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rosing-Asvid, A.; Teilmann, J.; Olsen, M.T.; Dietz, R. Deep Diving Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina) in South Greenland: Movements, Diving, Haul-out and Breeding Activities Described by Telemetry. Polar Biol. 2020, 43, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, G.; Cremer, J.; Kirkwood, R.; Van Der Wal, J.T.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Brasseur, S. Spatial Distribution and Habitat Preference of Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina) in the Dutch North Sea; Wageningen Marine Research: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Granquist, S.M.; Hauksson, E. Seasonal, Meteorological, Tidal and Diurnal Effects on Haul-out Patterns of Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina) in Iceland. Polar Biol. 2016, 39, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.D.; Lydersen, C.; Ims, R.A.; Kovacs, K.M. Haul-Out Behaviour of the World’s Northernmost Population of Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina) throughout the Year. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renouf, D.; Lawson, J.W. Play in Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina). J. Zool. 1986, 208, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.; Makecha, R.; Kuczaj, S. The Development of Social Play in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2014, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Komaba, M.; Komaba, K.; Matsuya, A.; Kawakubo, A.; Nakahara, F. Social Object Play between Captive Bottlenose and Risso’s Dolphins. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, V.; Borstel, U. Assessing and Influencing Personality for Improvement of Animal Welfare: A Review of Equine Studies. CABI Rev. 2013, 2013, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetley, C.L.; O’Hara, S.J. Ratings of Animal Personality as a Tool for Improving the Breeding, Management and Welfare of Zoo Mammals. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vere, A.J.; Lilley, M.K.; Highfill, L. Do Pinnipeds Have Personality? Broad Dimensions and Contextual Consistency of Behavior in Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina) and California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).