Abstract

The Botanical Garden of Southern Federal University (SFedU Botanical Garden) is the first botanical garden in the steppe zone of southern Russia, founded in 1927. The priority task of the SFedU Botanical Garden was the introduction of woody plants for greenery and forestry. It has been shown that the introduction of woody plants was the root cause of their invasion in the region. A total of 24 species of invasive trees and shrubs have been identified in the Priazovsky district of the Rostov region. Using species with high seed reproductive capacity and resistance to climatic factors to expand the range of woody plants used for greenery in urban areas poses a real threat of invasion. Thus, 83 species spread spontaneously from the SFedU Botanical Garden collections across its territory, 50 of which are not currently found in the regional culture. An important step in the management of invasive woody plants is for municipalities to adopt basic assortment lists for greening purposes. The SFedU Botanical Garden’s collection policy for woody plants should focus on reducing the number of species in living plant collections by removing species that self-seed and currently have no scientific, educational, or practical use. These species can be stored in a seed bank for future use. The introduction policy of the SFedU Botanical Garden should be aimed at mobilizing and introducing species that are not only highly resilient and effective in providing ecosystem services, but also possess properties that limit their invasion.

1. Introduction

Over the past 200 years, virtually all geographical barriers to the spread of plants have been destroyed [1]. Currently, the invasion of alien plants has become a serious global threat to the environment and the economy [2,3,4]. This process is exacerbated by climate change, which contributes to the transport, establishment, and spread of invasive species [5]. Another important factor influencing global plant invasions is historical and recent changes in land use [6]. Therefore, the development of effective measures for monitoring and controlling invasive species is considered by many countries to be a matter of national biosecurity [7].

In order to determine the specifics for a regional strategy to manage invasive plants in the steppe zone of southern Russia, particular attention is paid to studying the naturalization processes of alien species belonging to woody life forms. Over the past 100 years, grassland ecosystems (prairies, savannas, steppes, meadows) have been strongly influenced by the invasion of woody plants (Woody Plant Encroachment) [8,9,10]. The invasion of woody plants into grassland communities leads to a decrease in species diversity [11], grass biomass [12], groundwater resources [13], and animal habitat loss [14]. In general, the invasion of alien tree species into zonal steppe communities can alter the structure, functions, and species composition of the ecosystem as a whole.

The main way that non-native woody plants get into new areas is through their introduction for agriculture, forestry, and landscaping [15,16,17]. It has been shown that the success of naturalization of alien tree species in America and Europe is mainly determined by the history of their introduction, in particular the frequency of their planting [1,18]. Of the 235 species of woody plants that have naturalized in North America, 85% were introduced for landscaping, and 14% for agriculture or forestry [19]. In Europe, 572 tree species have become naturalized as a result of cultivation [18]. In China, 454 plant species have become naturalized as a result of introduction [20]. Of the 616 invasive species on 18 island groups in the Caribbean region, more than half (54%) were intentionally introduced for landscaping purposes [21]. The invasion of non-native tree species into steppe communities in Russia, as a result of large-scale afforestation programs, is also a proven fact [22]. It should be noted that until recently, most introduced woody plants were considered very useful and necessary for the development of humanity, but now an increasing number of such species are considered dangerous to biodiversity [23].

Botanical gardens played a global role in the introduction of plants. From the 17th to the early 20th century, botanical gardens were the main centers for introducing plants. The St. Louis Declaration on Invasive Plant Species notes that “The introduction and improvement of plants are fundamental to modern agriculture, providing diversity of plants used for food, forestry, landscaping, horticulture, and other purposes.” Currently, botanical gardens involved in plant introduction focus primarily on species that are valuable for horticulture [24], as well as on finding commercial ornamental plants (releasing new varieties) and trading them. There is now growing evidence of a significant link between the activities of botanical gardens and plant invasions around the world. Botanical gardens located in global biodiversity hotspots have often been involved in the introduction of ecological weeds listed by the IUCN as among the world’s most dangerous invasive species [25]. Even with botanical gardens gradually moving away from introduction towards the conservation of biological diversity, there are still many opportunities for the unintentional spread of alien species. Botanical gardens face serious difficulties in managing their living collections to prevent plant invasions [26]. This is important to consider, as the modern essence of any botanical garden is its plant collections, which number around 80,000 to 100,000 taxa worldwide [27]. For example, it has been established that 769 species cultivated in botanical gardens in the Midwest, the United States, and Canada are spreading spontaneously throughout the territory [28].

Thus, the introduction of plants for horticulture leads to the emergence of invasive species and can negatively affect biological diversity. This contradicts the current focus of botanical gardens—biodiversity conservation. At the same time, in many regions of the world, it is impossible to abandon the introduction of woody plants and ecosystem services provided by already introduced exotic species [29,30,31]. It should be agreed with Heywood [32] that one of the consequences of global climate change will be the demand for new germplasm of all plant species. In this regard, the introduction of plants may take on new significance. Modern methods for introducing woody plants should consider not only the ecosystem and economic benefits of cultivating non-native species, but also the possible consequences of their invasion, taking into account ongoing climate change. Developing a methodology for managing invasions of exotic tree species that are of great economic and ecosystem importance is also an important task. This area of activity could become a priority for botanical gardens. It is therefore important to have an understanding of the experience of individual botanical gardens with the introduction of woody plants, as this may be unique. In this regard, the experience of introducing woody plants at the Botanical Garden of Southern Federal University (SFedU Botanical Garden) is of interest. This is the first botanical garden in the steppe zone of southern Russia, established in 1927. Due to the fact that the local flora is poor in trees and shrubs valuable for landscaping and forestry, the priority task of the SFedU Botanical Garden was to introduce woody plants.

The objectives of the study were to analyze the SFedU Botanical Garden’s introduction policy with regard to woody plants, and to assess the SFedU Botanical Garden’s capacity to manage woody plant invasions in the region and identify priority steps in this direction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region, Climatic and Soil Conditions

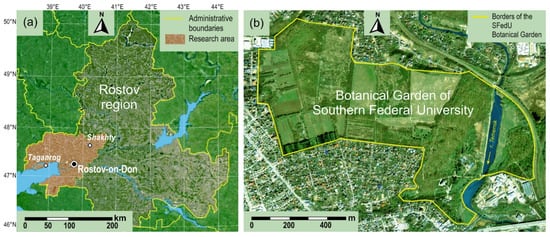

The results of the study are limited to the Azov climatic region of the Rostov region of Russia (Figure 1). It includes such large cities of the region as Rostov-on-Don, Taganrog, Azov, and Novocherkassk. The SFedU Botanical Garden is located in the city of Rostov-on-Don and covers an area of 160 hectares (47°13′ N; 39°39′ E).

Figure 1.

Study region: (a)—location of the study region; (b)—territory of the SFedU Botanical Garden.

The zonal vegetation type of the study region is steppe [33]. Native tree vegetation is represented by floodplain, wetland, and sand dune forests, as well as shrub communities.

The region has a humid continental climate with hot summers (Dfa). The average annual air temperature is +11 °C, and the vegetation period lasts 216 days. The average annual temperature in January (the coldest month) is −5.7 °C, and the average annual temperature in July (the warmest month) is +24.0 °C. The absolute minimum annual temperature is −31.9 °C, and the absolute maximum is +41.0 °C. The average annual precipitation is 618 mm, and the average annual evaporation is 840 mm. The climatic conditions of the region strictly regulate the range of woody plants used in agriculture, landscaping, and for meliorative goals. An exotic tree species that is promising for regional cultivation must combine high drought resistance with high frost resistance. This syndrome is characteristic of a limited group of woody plants [34].

The soil of the region is ordinary southern European black soil. The humus horizon is 75–100 cm thick, with a humus content of 3.9–4.7%. The granulometric composition is clayey. The carbonate level is high. The soil environment is neutral or slightly alkaline. Such soils are suitable for most woody plants.

2.2. Determination of the Taxonomic Composition of the Actual Range of Settlements and Invasive Tree Species in the Study Region

The actual range of woody plants included species that were sustainably cultivated in the region. Important criteria for the sustainable cultivation of a species are its occurrence in all large settlements, different types of plantings, the presence of specimens of different ages, and the cultivation of this species in local nurseries.

The following criteria were used to determine the invasive status of a species: self-reproducing populations (presence of individuals at all stages of ontogenesis); the ability to produce reproductive offspring; the ability to spread to new territories. The material was collected during surveys of green spaces in populated areas, artificial and natural plant communities, analysis of literary and archival sources, as well as herbarium samples from the Department of Botany of SFedU (RV) and the SFedU Botanical Garden (RWBG).

The territory of the SFedU Botanical Garden was studied in detail to identify alien species spreading spontaneously throughout it. Tree and shrub species that spontaneously spread from collections, entered the generative phase of ontogenesis, and produced viable seeds were classified as invasive for the SFedU Botanical Garden.

In the assessment of the seed reproductive capacity of woody plants, the presence of self-sown plants (woody plants of natural origin, grown from seeds, up to two years old) was recorded.

Publications and archival documents were used to analyze the introduction policy of the SFedU Botanical Garden.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Features of the SFedU Botanical Garden’s Introduction Policy

The actuality of introducing woody plants to the region was determined by the few species of local flora suitable for landscaping (Table 1) and unfavorable climatic conditions for the growth and development of woody plants.

Table 1.

List of woody plants cultivated in the Azov climatic region of the Rostov region.

The first collection of exotic trees in the SFedU Botanical Garden was created in 1930, and the first list of woody plants for landscaping settlements in the region was published by V.M. Kupchinov [35] in 1935 and included descriptions of 125 species of trees and 102 shrubs. Subsequently, assortment lists were published in 1952 and 2009. In addition, several fruit cultures were introduced, including Juglans regia L., Corylus avellana (L.) H.Karst. and C. colurna L., Prunus persica (L.) Batsch, Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Hippophae rhamnoides L., Cornus mas L., and species of the genus Citrus. The formation of an assortment for steppe afforestation was a secondary task.

The introduction of plants in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was established as a scientific direction. Until the second half of the 20th century, there were different views on the understanding of the term ‘introduction of plants’ in the botanical gardens of the USSR. In 1971, the Council of Botanical Gardens of the USSR approved the definition of plant introduction as ‘purposeful human activity aimed at introducing plants that did not previously grow in a certain natural-historical region into cultivation, or transferring them from the local flora’. And further, ‘…human activity aimed at enriching the plant resources of a country or region with new plants, as well as preserving endangered species.’ This definition did not contain a clear list of characteristics of the introduced plant and opened up opportunities for attracting plants that were of no economic value to regional culture.

The main method used to select objects for introduction into the SFedU Botanical Garden was the climate analog method proposed by Mayer [36]. Over the years, the SFedU Botanical Garden has used the climatic zoning proposed by Mayer [36], Krussmann [37], W. Köppen [38], and the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone. The climate analog method proved to be very effective for tree life forms, but did not prevent the introduction of potentially invasive species. The ‘genus complexes’ method proposed by F. N. Rusanov [39] has been reflected in the garden’s introduction policy since the 1970s. It is precisely the use of this method that is associated with the sharp growth of the dendrological collection during those years (Figure 2). The essence of the method is that, for the introduction test, all species of the genus were mobilized as far as possible, without taking into account their biological and ecological properties and economic qualities. Species that responded positively to geographical transfer were left in the botanical garden for further introduction testing. The advantage of this method lies in the possibility of assessing phylogenetic relationships within a genus based on the response of species to changed conditions and evaluating the relative plasticity of species. In addition, large genus complexes offer more opportunities for obtaining new forms through hybridization. However, from the point of view of introduction, this method proved to be ineffective, very resource-intensive, and opened wide ‘gates’ into the collection for invasive species. The largest number of species was collected for the genus complexes Acer, Berberis, Cotoneaster, Crataegus, Lonicera, Malus, Sorbus, Spiraea, Syringa, Quercus (Table 2). However, only 6% of species from these genus complexes are currently in stable and sustainable regional cultivation. Only two perspective hybrids (Acer platanoides × A. truncatum and Corylus colurna × C. avellana Purpurea) were obtained at the SFedU Botanical Garden. Whereas, as a result of free pollination of species grown close to each other, numerous specimens of Crataegus and Lonicera of hybrid origin spread throughout the garden.

Figure 2.

Changes in the total number of tree species in the SFedU Botanical Garden collection over time.

Table 2.

Taxonomic composition of genus complexes and number of species in their composition in regional culture (excluding native species).

The mobilization of woody exotic species for introduction trials was mainly carried out through the exchange of seed samples for scientific purposes between botanical gardens and other botanical institutions around the world within the Index Seminum system. For the most part, these were seeds of woody exotic species obtained ex situ in donor botanical gardens. Thus, species that had already demonstrated their ability to produce viable seeds in new conditions were mobilized for introduction testing.

During the introduction test, the tree’s ecological and biological properties were assessed, such as winter hardiness, drought resistance, resistance to diseases and pests, and seed reproductive capacity [40]. The ecological and biological properties of the plants were assessed based on external characteristics using a five-point scale (the highest expression of a characteristic corresponds to 5 points). The potential of the plants for regional cultivation was assessed based on the sum of the points for all four properties (the higher the sum, the higher the potential). The assessment of seed productivity was included in the introduction test of exotic species because it was believed [41] that seed generations are more resistant to new conditions. In addition, seed reproduction is the most effective way of reproduction in cultivation for many woody plants. The highest score on the seed productivity scale means that the plant bears fruit abundantly and regularly, producing self-seeding in areas without irrigation. Thus, the plant assessed as the most promising for regional cultivation had a high potential for naturalization.

Empirical evidence has shown that a sufficiently reliable period for introduction testing is 12–15 years for trees, 5–7 years for shrubs, and 3–5 years for semi-shrubs. The long period of introduction testing for exotic trees influenced the formation of the SFedU Botanical Garden collections—due to the inability to keep experimental plant specimens in the introduction nursery for a long time, they were transplanted to permanent locations in the arboretum. The ‘genus complex’ method also influenced the species composition of the collections. The unjustified expansion of the collections was also facilitated by the main criterion for evaluating the work of botanical gardens in the USSR, which is still used today: the number of plant taxa cultivated in the garden’s collections. As a result, the dendrological collection of the SFedU Botanical Garden accumulated a relatively large number of species that had no economic, breeding, educational, or scientific application.

Thus, the methods used to select exotic species for introduction testing, mobilize source material, and form collections did not provide for barriers to the penetration of invasive woody plant species into the region. On the contrary, they contributed to this. And this is despite the fact that some biological characteristics inherent in ornamental plants themselves (rapid growth and rooting, formation of large numbers of flowers, fruits, and seeds, ease of reproduction) are known to contribute to their invasions [42]. In addition, the cultivation of ornamental plants intensifies the effect of propagule pressure. The absence of stable plant communities and the large number of vacant ecological niches in populated areas lead to the rapid spread of new alien species introduced for landscaping purposes [43].

3.2. The Role of SFedU Botanical Garden in Managing Woody Plant Invasions

3.2.1. Results of Introducing Woody Plants to SFedU Botanical Garden

To understand the role of SFedU Botanical Garden in the process of managing tree invasions, it is necessary to evaluate the results of the institution’s activities in introducing tree species into regional culture. The dynamics of the SFedU Botanical Garden’s tree collection is shown in Figure 2.

Over the past three decades, species that have not found economic or scientific application have begun to disappear from the collection due to a lack of resources. This has resulted in a reduction in the collection’s holdings.

A total of 1032 species of woody plants belonging to 204 genera from 66 families of angiosperms and gymnosperms underwent a full cycle of introduction testing at the SFedU Botanical Garden. A total of about 2000 species were involved in the introduction test, but some of them dropped out in the early stages of the introduction test due to low resistance. Based on the results of the introduction test of exotic species and an assessment of their ecological and biological properties, 540 species from 154 genera and 58 families were recommended as promising for regional cultivation [44]. Of these, 196 were trees, 329 were shrubs, and 15 were semi-shrubs. Thus, the effectiveness of mobilizing exotic trees for introduction testing was 27% (the ratio of species promising for cultivation to species involved in the testing). Only 105 alien species are sustainably cultivated in the region, accounting for 87% of the total range, including native species (Table 1).

Cultivated alien species represent 72 genus from 34 families. Some of these species were cultivated in the region even before the SFedU Botanical Garden was established. These are Acer negundo, A. platanoides, Ailanthus altissima, Amorpha fruticosa, Celtis occidentalis, Fraxinus pennsylvanica, Gleditsia triacanthos, Morus alba, and Parthenocissus inserta. Two species, Acer negundo and Ailanthus altissima, have not been cultivated in the region in recent decades, but thanks to spontaneous dispersal, they are now a stable part of the urban flora. Among the cultivated alien species, 61 are trees, 42 are shrubs, and 2 are semi-shrubs. It should be noted that the practice of greening populated areas has been very conservative in terms of increasing the diversity of tree species by introducing new exotic species. This is especially true for shrubs. Despite the fact that there are many more shrub species that are promising for regional cultivation in terms of their ecological and biological properties than trees, only a small proportion of them are cultivated on a stable and continuous basis [44]. This is due to the fact that shrubs have less architectural, planning, and ecological significance than trees, a shorter ontogenesis. Therefore, the range of shrubs varies significantly depending on the location and time, with only the core of the most sustainable and irreplaceable species remaining constant through time (Table 1).

The chorology of alien species that have passed the introduction test during the entire period of SFedU Botanical Garden’s activity and are present in regional culture is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Natural ranges of alien tree species that have undergone introduction trials, are cultivated, and have become invasive in the region.

Among the species that have undergone introduction testing, those originating from North America, East Asia and China, Central and Middle Asia, the Far East, and Japan predominate. Among cultivated species, exotic species from North America significantly predominate.

3.2.2. Assessment of Woody Plant Invasion in the SFedU Botanical Garden

Serious attention was paid to the problem of invasive alien species in the second half of the 20th century [45]. Research into the invasion of woody plants in the Rostov region began only in the late 1990s [40].

Twenty-four species of invasive woody plants (Table 4) were identified in the region [46,47], which have self-reproducing populations, produce reproductive offspring, and spread to new territories. They belong to 22 genera from 14 families. Among them are 16 species of trees and 8 species of shrubs. All of these species, except for Elaeagnus angustifolia (the method of introduction of this species is unknown), are ‘escapees’ from culture.

Table 4.

List of invasive woody plant species for the Priazovsky climatic region of the Rostov region and SFedU Botanical Garden.

Within dendrological collections, regular self-seeding has been observed for 186 species of woody plants. However, for some species, self-seeding is not long-lasting, and seedlings die from drought or frost in the first two years. Of these species, only 83 have spontaneously spread beyond the collection. Their occurrence in the SFedU Botanical Garden varies, but for all of them, specimens of different ages have been recorded, at different stages of ontogenesis, including the generative stage. These species have been identified as invasive to the SFedU Botanical Garden. Invasive species for the SFedU Botanical Garden belong to 44 genera from 24 families. Of the 83 species invasive to the garden territory, 50 are not currently found in regional culture. Specimens of these species have not been found outside the boundaries of the SFedU Botanical Garden, which may be due to the high level of management of these areas. However, a railway runs along the border of the SFedU Botanical Garden, and the Temernyk River flows through the territory (Figure 1), which creates additional risks for the spread of alien species.

Based on the results obtained, it should be noted that the conservatism of ornamental tree culture with regard to expanding its diversity in the region has become a significant barrier to the invasion of alien tree species. In addition, this has provided an opportunity and time to assess the invasive potential of alien species that are promising in terms of their ecological and biological properties and economic qualities for regional cultivation, and to make adjustments to the introduction testing program.

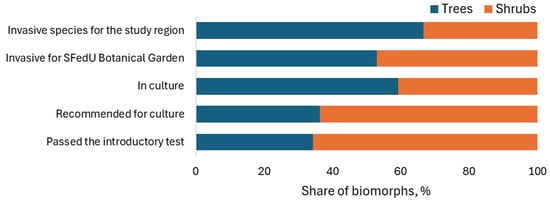

It is advisable to consider the relationship between the invasive potential of tree species and their life form. The predominance of trees over shrubs among invasive species in the region can be linked to the proportion of these life forms in the regional culture, from which they are “runaways” (Figure 3). However, the predominance of trees over shrubs in the group of species invasive to the SFedU Botanical Garden territory (44 tree species, 39 shrub species) cannot be explained by the proportion of these life forms among the species that have passed the introduction test (the number of shrubs is almost three times higher than the number of trees).

Figure 3.

Ratio of trees and shrubs among exotic species that have passed the introduction test and among invasive species.

The predominance of trees over shrubs among invasive species may be due to the more powerful root system of tree seedlings, which can reach groundwater when mature. This allows them to survive successfully in arid conditions and compete successfully with native vegetation [48].

The distribution of species by area is presented in Table 3. In general, the chorological structure of invasive species corresponds to that in the collection and in regional culture. Among the invasive species in the SFedU Botanical Garden, North American flora species lead with an almost twofold advantage. Among the species cultivated in the region and invasive to the region, those originating from North America also predominate. The relatively high representation of North American species among invasive plants can be attributed both to their predominance among cultivated species and to their greater plasticity in relation to climate change (Table 3) [49]. With the exception of U. pumila, the ranges of invasive species are located south of the point of introduction. Accordingly, they exhibit higher drought tolerance at the point of introduction than native species.

In terms of seed dispersal, the vast majority of these species are zoochorous (fruit crops are also anthropochorous) and anemochorous. Amorpha fruticosa is dispersed by water, while Genista tinctoria and Cytisus austriacus are ballistic.

The change in the number of species in the series ‘species that have passed the introduction test’—‘species promising for culture’—‘species cultivated in the region’—‘invasive species in the region’ has a hyperbolic shape (Figure 4a). Of the introduced species that are sustainably cultivated in the region, 23% have become invasive here. This contradicts the ‘rule of tens’ [50] to a certain extent and is more in line with the calculations of Pfadenhauer and Bradley [51], who determine the invasion rate to be between 17% and 25%.

Figure 4.

Bar chart of woody plant species that have passed the introduction test, cultivated in the region, and invasive species. (a) Dynamics of the number of species in the continuum ‘Passed the introductory test—recommended based on the results of the introduction test for the culture—introduced into the culture—escaped from the culture (invasive species for the region)’ (b) Dynamics of the number of species in the continuum ‘Passed the introductory test—self-seeding within the collection—invasive for the SFedU Botanical Garden’.

The ratio of species that regularly self-seed in the SFedU Botanical Garden to the number of species that have passed the introduction test is 18% (Figure 4b). The ratio of invasive species in the SFedU Botanical Garden to the number of species that regularly self-seed is 45%. In general, the presence of self-seeding in exotic species at the introduction test site is a relatively reliable predictor of invasiveness. However, to diagnose this trait, the introduction test must be conducted for about five years after the plant enters the generative phase.

Based on the study of woody plant species invasive to the SFedU Botanical Garden territory, the following assumptions can be made. In terms of the risk of invasion, all alien species of the genus Crataegus and deciduous shrubs of the genus Lonicera, which are the most common invasive species in the SFedU Botanical Garden, should be considered dangerous. The cultivation of Acer tataricum subsp. aidzuense (a species very similar in ecological and biological properties to the native A. tataricum) may also pose a threat. Cultivation of Elaeagnus umbellata, Colutea arborescens, and C. orientalis, which are highly drought-resistant and undemanding in terms of soil thanks to their symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, Fontanesia fortunei, due to its high drought resistance and winter hardiness combined with the absence of phytophages and diseases, Padus virginiana, due to its combination of high seed reproductive capacity and vegetative mobility, is highly likely to lead to the emergence of new invasive species in the region. The semi-shrubby vine Clematis vitalba, a biomorph not found in the local nemoral flora, poses a very serious threat to floodplain forests [52]. At the same time, the species is highly drought-resistant and winter-hardy in the region, is not affected by diseases and pests, is resistant to herbicides, and is vegetatively mobile. All these species should not be allowed into regional cultivation.

3.2.3. SFedU Botanical Garden’s Capabilities for Managing Woody Plant Invasions

The naturalization of alien tree species is a growing global problem, as they are often actively planted far beyond their natural ranges for forestry, reclamation, or ornamental purposes [53]. Therefore, this process must be centrally managed. During the USSR times, SFedU Botanical Garden was the only organization in the region engaged in the introduction of woody plants and having access to foreign plant resources. However, at the end of the 20th century, this access became potentially open not only to all organizations but also to private individuals. In other words, the possibility of managing invasions by adjusting introduction policies disappeared. The uncontrolled importation of ornamental plants into Russia has already had a significant impact on the species composition of phytopathogens [54]. At the same time, as the only institution in the region with scientific experience in the introduction of woody plants, the SFedU Botanical Garden must take on the functions of controlling and managing invasions of woody plants. The main areas of activity are set out in the 14 principles of the voluntary Code of Conduct on Forest Plantations and Invasive Alien Trees [55]. This code takes into account the provisions of the Code of Conduct on Horticulture and Invasive Alien Plants published by the Council of Europe [56], intended for the horticultural industry and trade, and the European Code of Conduct for Botanical Gardens on Invasive Alien Species [24].

We will focus only on some of the most relevant areas of work carried out by the SFedU Botanical Garden. In our opinion, it is impossible to eradicate alien tree species that have long since ‘escaped’ from cultivation and spread widely throughout the region, and, moreover, it is not advisable for most species. At the same time, it is necessary to proceed from the ratio of the benefits of cultivating alien species to the potential harm from their invasion [57]. In the regional climate, which is uncomfortable for human habitation and requires reclamation, alien woody plants have played a significant positive role. A clear example is the consequences of the mass death of Fraxinus pennsylvanica over the past three years, which accounted for more than 15% of plantings in populated areas and protective forest strips for agricultural purposes, from the pest Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire. This invasive tree species made a significant contribution to the ecosystem services provided by artificial woodlands. In addition, it is known that measures aimed at eradicating invasive species are rarely successful [58,59,60], and the results are often only temporary [61]. In some cases, control methods targeting one invasive species can contribute to secondary invasions [62]. Furthermore, the removal of alien tree species is very costly [63]. The SFedU Botanical Garden’s activities with regard to these species may be limited to monitoring in order to predict the long-term consequences of their invasion. Of course, the SFedU Botanical Garden should take all measures to prevent the spread of invasive tree species on its territory by removing them. The possibilities for their regional cultivation should be determined by the scientific community based on a comprehensive analysis of the possible negative consequences and expected ecosystem services. This requires coordination of efforts at the regional level.

Unfortunately, regional municipalities do not have long-term plans for managing green spaces, as is practiced in the US and Canada (Urban Forest Management Plans—UFMP) [64]. The first step in solving this problem could be to return to the practice of approving a basic range of plants for greening municipal formations, which was used in the USSR. The basic range is a list of plants that provide significant ecosystem services in the region, including the most sustainable and durable trees. These trees should make up at least 70% of the main types of green spaces (squares, gardens, parks, and urban forests). The main assortment is developed by specialized scientific institutions and approved by the municipality for a period of 10 years (5 years is proposed). It must be implemented when designing green spaces in municipalities. In addition, the main assortment is a tool for managing the assortment of local nurseries of ornamental plants. One of the management objectives is to reintroduce local species such as Quercus robur and Acer campestre into the urban landscape.

An important area of activity for the SFedU Botanical Garden should be the creation of a seed bank for woody plants [65,66]. Most woody species from the garden’s living collections produce orthodox seeds, which can be stored for long periods at sub-zero temperatures. This primarily applies to plants that are not currently of scientific or practical interest. Removing some tree species from living collections and storing them in a seed bank will reduce the risk of invasion and cut the costs of maintaining dendrological collections.

Currently, the formation of collections is defined as the main function of botanical gardens in Russia. However, the introduction of woody plants in the steppe zone in the context of climate change, invasion, and evolution of phytophages and phytopathogens may become an even more pressing task than it was a century ago. In terms of countering invasions, introduction should be aimed at introducing woody plants with induced sterility into cultivation [67]. Species that do not have obvious resource value should not be included in introduction trials.

4. Conclusions

The primary cause of the invasion of alien woody plants in the region is their introduction for landscaping and artificial reforestation purposes. A total of 24 species are considered invasive in the region. Among them are 16 species of trees and 8 species of shrubs. Expanding the range of woody plants for landscaping settlements with species that have high seed reproductive capacity and resistance to climatic factors poses a real threat of their invasion. Thus, 83 species from the collections of the SFedU Botanical Garden spontaneously spread throughout the garden, 50 of which are currently not found in regional cultivation. Of these, the species of the genera Crataegus and Lonicera, as well as Acer tataricum subsp. aidzuense, Elaeagnus umbellata, Colutea arborescens and C. orientalis, Fontanesia fortune, Padus virginiana, and Clematis vitalba, may pose the greatest danger as potential invasive species. At present, the SFedU Botanical Garden’s ability to manage the introduction of woody plants into the region is limited. An important step in organizing the management of invasive alien plant species is for municipalities to adopt lists of the main range of plants for landscaping purposes. The policy of the SFedU Botanical Garden should be aimed at collecting plant species that have high potential for scientific, educational, or practical use and are characterized by a limited risk of invasion. It is advisable to exclude species that reproduce by self-seeding and currently have no scientific, educational, or practical significance from collections of living plants. These species can be stored in a seed bank for future use. The SFedU Botanical Garden’s introduction policy should be aimed at mobilizing and introducing species that are not only highly resilient and effective in providing ecosystem services, but also have properties that limit their invasion (primarily sterility). All species that spontaneously spread throughout the SFedU Botanical Garden should be eradicated. Thus, all botanical gardens involved in plant introduction must take into account that this process is inevitably accompanied by the appearance of invasive species in the region. In this regard, botanical gardens should focus their efforts on finding and creating forms and varieties of woody plants that are incapable of seed and vegetative reproduction. The transition from introduction to biodiversity conservation (essentially species collection) also does not eliminate the risk of invasion. The example of the SFedU Botanical Garden shows that even woody species can spontaneously spread from the collection area over time, and it is only a matter of time before they cross the boundaries of the botanical garden.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.K.; Data curation, B.L.K., O.I.F. and M.V.K.; Formal analysis, B.L.K., A.A.D. and P.A.D.; Investigation, B.L.K., O.I.F., M.V.K., M.M.S., A.A.D. and P.A.D.; Methodology, B.L.K.; Project administration, B.L.K.; Software, A.A.D.; Writing—original draft, B.L.K., O.I.F., M.V.K., M.M.S., A.A.D. and P.A.D.; Writing—review and editing, B.L.K., O.I.F., M.V.K., M.M.S., A.A.D. and P.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (no. FENW-2023-0008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Strategic Academic Leadership Program of the Southern Federal University (“Priority 2030”).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reichard, S.H.; Hamilton, C.W. Predicting Invasions of Woody Plants Introduced into North America: Predicción de Invasiones de Plantas Leñosas Introducidas a Norteamérica. Conserv. Biol. 1997, 11, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, K.A.; Dukes, J.S. Plant invasion across space and time: Factors affecting nonindigenous species success during four stages of invasion. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradova, Y.K.; Tokhtar, V.K.; Notov, A.A.; Mayorov, S.R.; Danilova, E.S. Plant invasion research in Russia: Basic project and scientific fields. Plants 2021, 10, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.P.; Singh, J.S. Invasive alien plant species: Their impact on environment, ecosystem services and human health. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslippe, J.R.; Veenendaal, J.A. Plant Invasions in a Changing Climate: Reshaping Communities, Ecosystem Functions, and Services. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2025, 56, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, M.B.; Tobak, Z.; Kaim, D.; Szillasi, P. Historical and recent land use/land cover changes as a driving force of biological invasion: A Hungarian case study. Biol. Invasions 2025, 27, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.M.; Barker, K.; Francis, R.A. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Biosecurity and Invasive Species; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Volume 24, pp. 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.R.; Andersen, E.M.; Predick, K.I.; Schwinning, S.; Steidl, R.J.; Woods, S.R. Woody Plant Encroachment: Causes and Consequences. In Rangeland Systems. Springer Series on Environmental Management; Briske, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, C.M.; Huynh, A.; Pennings, S.C. Woody structure facilitates invasion of woody plants by providing perches for birds. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 8032–8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.S.; Sano, E.E.; Ferreira, M.E.; Munhoz, C.B.R.; Costa, J.V.S.; Rufino Alves Júnior, L.; de Mello, T.R.B.; da Cunha Bustamante, M.M. Woody Plant Encroachment in a Seasonal Tropical Savanna: Lessons about Classifiers and Accuracy from UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.F.P.; Kansbock, L.; Rossato, D.R.; Kolb, R.M. Woody plant encroachment constrains regeneration of ground-layer species in a neotropical savanna from seeds. Austral Ecol. 2022, 47, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Shoender, J.R.; McCleery, R.A.; Monodjem, A.; Gwinn, D.C. The importance of grass cover for mammalian diversity and habitat associations in bush encroached savanna. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 221, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Kharel, G.; Zou, C.B.; Wilcox, B.P.; Halihan, T. Woody plant encroachment impacts on groundwater recharge. Rev. Water 2018, 10, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Soto, E.; Johnson, P.J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Barrett, G.A.; Segundo, J. Woody plant encroachment drives habitat loss for a relict population of a large mammalian herbivore in South America. Therya 2020, 11, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, S.H.; White, P. Horticulture as a pathway of invasive plant introductions in the United States: Most invasive plants have been introduced for horticultural use by nurseries, botanical gardens, and individuals. Bioscience 2001, 51, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.-C.; Yang, Q.; Kinlock, N.L.; Pouteau, R.; Pyšek, P.; Weigelt, P.; Yu, F.-H.; van Kleunen, M. Naturalization of introduced plants is driven by life-form-dependent cultivation biases. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, B.L.; Dmitriev, P.A.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V.; Fedorinova, O.I. Woody flora of the Northern city cemetery of the Rostovon-Don city, Russia. Ecosyst. Transform. 2025, 8, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucharova, A.; Van Kleunen, M. Introduction history and species characteristics partly explain naturalization success of North American woody species in Europe. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, S.E. Assessing the Potential of Invasiveness in Woody Plants Introduced in North America; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M.; Hulme, P.E. Botanic gardens play key roles in the regional distribution of first records of alien plants in China. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Sandoval, J.; Ackerman, J.D. Ornamentals lead the way: Global influences on plant invasions in the Caribbean. NeoBiota 2021, 64, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokhtar, V.K.; Kurskoy, A.Y. Invasive species of plants of the steppe sections in the south-west of the Central Russian Upland (Belgorod region). In Proceedings of the Steppes of Northern Eurasia: Materials of the X International Symposium, Orenburg, Russia, 27–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isajev, V.; Stankovic, M.; Orlovic, S.; Bojic, S.; Stojnic, S. The importance of woody plant introduction for forest trees improvement. AGROFOR Int. J. 2017, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H.; Sharrock, S. European Code of Conduct for Botanic Gardens on Invasive Alien Species; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Richmond, VA, USA, 2013; 61p. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, P.E. Addressing the threat to biodiversity from botanic gardens. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaedi, D.I.; Putri, D.M.; Kurniawan, V. Assessing the invasion risk of botanical garden’s exotic threatened collections to adjacent mountain forests: A case study of Cibodas Botanical Garden. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosmann, M. Research in the garden: Averting the collections crisis. Bot. Rev. 2006, 72, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culley, T.M.; Dreisilker, K.; Clair Ryan, M.; Schuler, J.A.; Cavallin, N.; Gettig, R.; Havens, K.; Landel, H.; Shultz, B. The potential role of public gardens as sentinels of plant invasion. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambani, A.E. Are introduced alien species more predisposed to invasion in recipient environments if they provide a wider range of services to humans? Diversity 2021, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Giro, Z.; Pedraza Olivera, R.; Lamadrid Mandado, R.; Hu, J.; Vila, L.F.; Sleutel, S.; Fievez, V.; De Neve, S. Invasive woody plants in the tropics: A delicate balance between control and harnessing potential benefits. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobul’ská, L.; Demková, L.; Pincáková, G.; Lošák, T. Alien Plant Invasion: Are They Strictly Nature’s Enemy and How Can We Use Their Supremacy? Land 2025, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H. The role of botanic gardens as resource and introduction centres in the face of global change. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurka, H.; Friesen, N.; Bernhardt, K.-G.; Neuffer, B.; Smirnov, S.; Shmakov, A.; Blattner, F. The Eurasian steppe belt: Status quo, origin and evolutionary history. Turczaninowia 2019, 22, 5–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visakorpi, K.; Manzanedo, R.D.; Görlich, A.S.; Schiendorfer, K.; Altermatt Bieger, A.; Gates, E.; Hille Ris Lambers, J. Leaf-level resistance to frost, drought and heat covaries across European temperate tree seedlings. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupchinov, V.M. Assortment for planting streets and parks in Rostov-on-Don. In Collection of Works of the Rostov-on-Don Botanical Garden Named After the Comintern for 1934; Bureau of Economic Bulletins: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 1935; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, G. Climate Analogs and Weather Predictions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1909; 250p. [Google Scholar]

- Krussmann, G. Handbuch der Laubgeholze; Parey: Berlin/Hamburg, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Das geographische System der Klimate. In Handbuch der Klimatologie; Köppen, W., Geiger, R., Eds.; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1936; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rusanov, F.N. Method of generic complexes in plant introduction. Bull. GBS USSR Acad. Sci. 1977, 81, 15–20. Available online: http://www.studfiles.ru/preview/2246767/page:2/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Kozlovsky, B.L.; Ogorodnikov, A.Y.; Ogorodnikova, T.K.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V.; Fedorinov, O.I. Flower Woody Plants of the Botanical Garden of Rostov University: Ecology, Biology, Geography; Old Russian: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 2000; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov, V.I. Development of Issues of Seeds of Introduced Plants in the Botanical Gardens of the USSR. Success of Introduction; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1973; pp. 290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleunen, M.; Essl, F.; Pergl, J.; Brundu, G.; Carboni, M.; Dullinger, S.; Early, R.; González-Moreno, P.; Groom, Q.J.; Hulme, P.E.; et al. The changing role of ornamental horticulture in alien plant invasions. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhariya, M.K.; Banerjee, A.; Raj, A.; Kittur, B.H.; Kerketta, S. Plant Invasion in the Urban Landscape: An Ecological Synthesis. In Invasive Alien Plants in Urban Ecosystems; Singh, R., Bhadouria, R., Tripathi, S., Kohli, R.K., Singh, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, B.L.; Ogorodnikova, T.K.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V.; Fedorinova, O.I. Assortment of Woody Plants for Green Construction in the Rostov Region; Publishing House South Federal University: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 2009; 416p. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, J.H.; Chong, K.Y.; Lum, S.K.Y.; Wardle, D.A. Trends in the direction of global plant invasion biology research over the past two decades. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, B.L.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V.; Fedorinova, O.I.; Sereda, M.M.; Kapralova, O.A.; Dmitriev, P.A.; Varduni, T.V. Adventive tree species in urban flora of Rostov-on-Don. Biol. Bull. Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol. State Pedagog. Univ. 2016, 6, 430–437. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovskiy, B.L.; Fedorinova, O.I.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V. Invasion of the Parthenocissus inserta (Kern.) K. Fritsch. in Floodplain Forests of Rostov Oblast. Russ. J. Biol. Invasions 2020, 11, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.R. Rangeland Conservation and Shrub Encroachment: New Perspectives on an Old Problem. In Wild Rangelands: Conserving Wildlife While Maintaining Livestock in Semi-Arid Ecosystems; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 53–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.T.; Heinen, H.; Koch, O.; de Avila, A.L.; Hinze, J. The Range Potential of North American Tree Species in Europe. Forests 2024, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.; Fitter, A. The Varying Success of Invaders. Ecology 1996, 77, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfadenhauer, W.G.; Bradley, B.A. Quantifying vulnerability to plant invasion across global ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2024, 34, e3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskiy, B.L.; Fedorinova, O.I.; Kuropyatnikov, M.V.; Dmitriev, P.A. Clematis vitalba L. as potentially invasive species of Rostov region. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2017, 7, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavaux, C.S.; Crowther, T.W.; Zohner, C.M.; Delavaux, C.S.; Crowther, T.W.; Zohner, C.M.; Robmann, N.M.; Lauber, T.; Van den Hoogen, J.; Kuebbing, S.; et al. Native diversity buffers against severity of non-native tree invasions. Nature 2023, 621, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selikhovkin, A.V.; Drenkhan, R.; Mandelshtam, M.Y.; Musolin, D.L. Invasionsof insect pests and fungal pathogens of woody plants into the northwestern part of European Russia. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Earth Sci. 2020, 65, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundu, G.; Richardson, D.M. Planted forests and invasive alien trees in Europe: A Code for managing existing and future plantings to mitigate the risk of negative impacts from invasions. In Proceedings of 13th International EMAPi Conference, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 20–24 September 2015; Daehler, C.C., van Kleunen, M., Pyšek, P., Richardson, D.M., Eds.; NeoBiota: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; Volume 30, pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H.; Brunel, S. Code of Conduct on Horticulture and Invasive Alien Plants; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, Austria, 2011; Volume 162, Available online: https://www.eppo.int/media/uploaded_images/ACTIVITIES/invasive_plants/Code_of_conduct_Horticulture_Invasive_Alien_Plants_May2011_EN.pdf.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Dickie, I.A.; Bennett, B.M.; Burrows, L.E.; Nuñez, M.A.; Peltzer, D.A.; Porté, A.; Richardson, D.M.; Rejmánek, M.; Rundel, P.W.; Van Wilgen, B.W. Conflicting values: Ecosystem services and invasive tree management. Biol. Invasions 2014, 16, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G.; Maxwell, B.D.; Menalled, F.D.; Rew, L.J. Lessons from agriculture may improve the management of invasive plants in wildland systems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 4, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettenring, K.M.; Reinhardt Adams, C. Lessons learned from invasive plant control experiments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, I.; Liu, G.; Petri, L.; Schaffer-Morrison, S.; Schueller, S. Assessing vulnerability and resistance to plant invasions: A native community perspective. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2021, 14, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, S.M.; Munson, S.M.; Bradford, J.B.; Butterfield, B.J. Influence of climate, post-treatment weather extremes, and soil factors on vegetation recovery after restoration treatments in the southwestern US. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2019, 22, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.E.; Ortega, Y.K.; Runyon, J.B.; Butler, J.L. Secondary invasion: The bane of weed management. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 197, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, L.; Larcher, F.; Devecchi, M. Urban green management plan: Guidelines for European cities. Front. Hortic. 2023, 2, 1105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wassenaer, P.J.; Satel, A.L.; Kenney, W.A.; Ursic, M. A framework for strategic urban forest management planning and monitoring. trees, people, and the built environment. In Proceedings of the Urban Trees Research Conference, Birmingham, UK, 13–14 April 2011; pp. 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Haidet, M.; Olwell, P. Seeds of success: A national seed banking program working to achieve long-term conservation goals. Nat. Areas J. 2015, 35, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambugu, P.W.; Nyamongo, D.O.; Kirwa, E.C. Role of Seed Banks in Supporting Ecosystem and Biodiversity Conservation and Restoration. Diversity 2023, 15, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocko, A.L.; Lu, H.; Magnuson, A.; Brunner, A.; Ma, C.; Strauss, S.H. Phenotypic expression and stability in a large-scale field study of genetically engineered poplars containing sexual containment transgenes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).