Abstract

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) are the main pollinators of many plant species, particularly agricultural crops. The concern over Colony Collapse Disorder of bee colonies in recent years necessitates the use of new approaches for their conservation in in situ and ex situ conditions. Modern techniques for cryopreservation of drone spermatozoa allow for the preservation of their genetic diversity. Some of the challenges in the field of cryopreservation are the alterations induced by the low temperatures, including morphological disruptions, plasma membrane integrity, formation of reactive oxygen species, DNA fragmentation, loss of motility, mitochondrial activity and viability, early hyperactivation, depletion of proteins from the acrosome region, premature capacitation, reduced sperm–oocyte fusion, and the occurrence of other cellular cryoinjuries. The objective of the current study is to contribute to the ongoing efforts in identifying substances added to semen extenders aimed at inhibiting cryogenic-induced changes. Our study investigates the impact of antioxidant supplements, scilicet vitamins C, vitamin E, and L-carnitine, on attenuating the adverse effects of cryogenic storage on drone spermatozoa. Using a Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis, we evaluated the effectiveness of various antioxidants added to the extender in maintaining sperm motility parameters following liquid nitrogen storage. The data indicated significant differences in sperm traits among treatments with supplements after post-thawing. These findings emphasize the advantageous contribution of these added antioxidants within semen extenders for drone spermatozoa in preserving sperm quality parameters. The establishment of novel protocols for cryogenic storage of honey bee drone spermatozoa, incorporating low-cytotoxicity additives, is of utmost importance for the conservation of this endangered species.

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Challenges in Cryopreservation

Long-term low-temperature storage of animal genetic resources and specifically the cryopreservation of male gametes reproductive capacity represents an effective approach for the preservation of the diversity of various wild and domesticated animal species. Cryopreservation techniques for genetic material are now widely used to preserve endangered plant and animal species, and their improvement is a subject of interest and innovation by environmental and agricultural scientists [1,2]. Such an approach would make possible not only the preservation of various species but would also be the first step of their reintroduction into their natural habitats affected by poor agricultural practices, preserving valuable lines in specialized botanical gardens [3]. The first attempts to cryopreserve honey bee drone spermatozoa were made during the late 1970s and early 1980s with the purpose of subsequent artificial insemination of the queens, but today the focus has shifted to the preservation of the species as whole in the context of challenges like climate change, spread of diseases, mass use of pesticides, etc. The main challenges with low temperature storage of drone semen are summarized in the loss of gametes motility after thawing, which subsequently leads to a decrease in their fertilizing capacity. Modern approaches to improving the process of low-temperature storage of male bee gametes rely largely on the selection of appropriate cryoprotective ingredients in the media that exhibit a good protective effect and low cytotoxicity. Nonetheless, it is imperative to consider the type and impact of the diluent on male gametes when optimizing sperm preservation methodology [4,5]. The cryopreservation and artificial insemination of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) has gained significant interest due to the concern of Colony Collapse Disorder. Current cryopreservation protocols for honey bee drone semen produce results with varying and controversial outcomes. The present study demonstrates the effect of three widely distributed antioxidants used as additives in cryopreservation media on the motility characteristics of honey bee drone spermatozoa in the process of cryopreservation and subsequent thawing.

1.2. Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidants and Their Role in Cryopreservation

Long-term low-temperature storage often leads to decreased sperm motility and viability [6,7]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are identified as one of the primary factors adversely impacting the viability and reproductive capacity of spermatozoa. ROS are typically generated from oxygen as byproducts during cellular metabolism. They participate in numerous physiological processes, including the regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis and steroidogenesis. Furthermore, ROS are integral to signaling pathways crucial for male fertility, encompassing sperm maturation, DNA compaction, flagellar modification, capacitation, hyperactivation, acrosome reaction, etc. [8]. Various factors, including diverse storage conditions, elevate the production of ROS, which correlate with structural and functional alterations in spermatozoa, encompassing apoptosis, lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, DNA damage, reduced motility, and morphological damage [8,9,10]. Antioxidants can mitigate the adverse effects of ROS and enhance the quality of spermatozoa [3]. Cells possess effective mechanisms to counteract ROS, primarily through antioxidants. Major antioxidants found in seminal plasma include enzymatic antioxidants such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase (enzyme triad), along with non-enzymatic antioxidants like vitamins C and A, glutathione, and L-carnitine (LC) [11,12]. Studies have shown that semen extenders supplemented with superoxide dismutase can enhance the freeze–thaw resilience of both bull spermatozoa [13] and stallion spermatozoa [14]. Supplementation with superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase maintained the quality of spermatozoa in dogs for 10 days at 4 °C [15]. According to some authors, antioxidants protect against the formation of lipid peroxidation in frozen-thawed sperm [16]. The use of resveratrol, vitamin E, and LC has also been shown to support sperm motility and viability while reducing DNA fragmentation [17,18]. Earlier studies have demonstrated that vitamins A and vitamin E positively affect spermatozoa during the freeze–thaw process by enhancing motility [17]. Vitamins E (tocopherol) and C (ascorbic acid or ascorbate) serve as crucial non-enzymatic antioxidants in seminal plasma across various species [19,20]. Vitamin E functions by inhibiting lipid peroxidation in cell membranes through scavenging peroxyl (ROO•) and alkoxyl (RO•) radicals [21]. The recycling of α-tocopherol is maintained by ascorbate or thiols, thereby sustaining the reduction in peroxyl radicals in the plasma membrane of cells [22]. Various data have illustrated the beneficial role of vitamin E supplementation in freezing media, enhancing the post-thaw survival and DNA integrity of spermatozoa [17,23]. The other most common non-enzymatic water-soluble antioxidant, vitamin C, inhibits lipid peroxidation via the action of Fe2+ and Cu2+ ions [24,25]. Other authors demonstrated that antioxidants enhance sperm motility and viability and exert a positive effect against DNA damage in sperm cells [26]. In contrast, research has yielded inconsistent results regarding the preservation of sperm characteristics when vitamin C is incorporated into the extenders during cryopreservation [27]. However, the effectiveness of antioxidants and different supplements in maintaining sperm quality during semen cryopreservation remains a topic of debate.

1.3. Cryopreservation of Honey Bee Drone Spermatozoa in Antioxidant Supplemented Media

Research into the effectiveness of antioxidants on the motility characteristics of drone sperm cells during long-term storage at ultra-low temperatures is extremely insufficient. Simplified protocols for cryobanking of drone spermatozoa would not only result in broadly applied practices for preservation of genetic material among environmental scientists, but would also provide a tool for beekeepers to preserve specific genetic lines in their apiaries. The presented research analyzes the alterations in the kinetic profile of drone spermatozoa following cryopreservation for 72 h and subsequent thawing in trehalose–dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-based cryoprotective media supplemented with the antioxidants vitamin C (ascorbic acid), vitamin E (tocopherol), and LC. The aim of the research is focused on the optimization of sperm cryopreservation success in honey bee drones by adding proper antioxidants in the cryoprotective media in order to preserve sperm cell motility.

2. Materials and Methods

Honeybee drones were collected from private apiaries, taking into account factors affecting their fertilizing capacity [28]. Ejaculates were obtained from drones at the 25th day of development by the method of manual eversion of the phallus. The drones were collected at the last week of May from seven healthy bee colonies with no difference in feeding and treatment between them. The procedure consists of applying pressure manually to the abdomen of the drone. Under this pressure, the abdomen of the mature drone contracts until the cornua of the endophallus are exposed. Additional pressure along the sides of the abdomen lead to the eversion of the endophallus, resulting in the appearance of a semen drop. Ejaculates were collected from the tip of the everted endophallus using a SCLEY® syringe (Elgersburg, Germany) under a Nexius Zoom High-Precision Trinocular Stereo Microscope (Duiven, The Netherlands) (6.7×–45×). To eliminate individual variation, all freshly collected ejaculates were pooled and diluted with a cryopreservation diluent at a ratio of 1:12. The diluent consisted of the following components (percentage ratio): 8% trehalose, 2% DMSO, 20% egg yolk, and 70% buffer (3% citric acid; 1% glucose; 6% Tris), adjusted to a final pH of 8.

After obtaining and pooling the ejaculates, initial sperm characteristics were measured. The analyses were performed using the Sperm Class Analyzer (SCA) by conducting Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA). The analyses were performed using the specialized SCA software modules for Motility and Concentration (SCA, Microptic, Barcelona, Spain®) were used.

Conventional analyses of immotile spermatozoa (%) (IM), non-progressive spermatozoa (%) (NP), progressive spermatozoa (%) (PR), and rapid spermatozoa (%) were performed. Additionally, the kinetic profile of the spermatozoa was evaluated using the following CASA parameters: curvilinear velocity (µm/s) (VCL), straight-line velocity (µm/s) (VSL), average path velocity (µm/s) (VAP), linearity (%) (LIN = VSL/VCL), and straightness (%) (STR = VSL/VAP), both before and after cryopreservation.

For the purposes of the analysis, samples were aliquoted into four distinct sperm fractions. The first aliquot, devoid of antioxidants, served as the control. Vitamin C (1.5 mg/mL) was added to the second aliquot, vitamin E (1.7 mg/mL) to the third aliquot, and the fourth aliquot was supplemented with LC (2.5 mg/mL). All sperm samples were loaded into cryogenic straws (Cryo Bio Systems®, L’Aigle, France ) and equilibrated for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by 30 min at −20 °C, and subsequently placed in liquid nitrogen vapor. Cryopreserved samples were thawed at 35 °C in a water bath for 60 s, and sperm quality was assessed using SCA. All data is presented is analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10, with Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc Dunn test p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Motility Assay

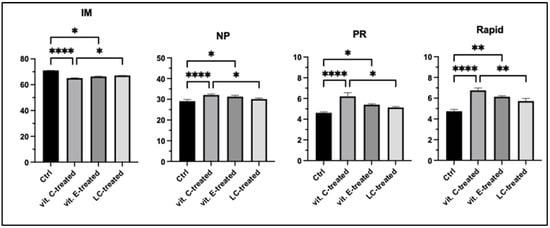

A variety of critical attributes of male gametes essential for successful fertilization must be preserved following cryogenic storage. Among these parameters, sperm motility is recognized as critical indicator of sperm quality, reflecting its functional capacity and overall viability. In this study, key sperm parameters were analyzed in fresh samples and post-thaw to evaluate the impact of cryopreservation on the functionality of drone sperm cells after supplementation with different antioxidants. CASA-analysis revealed statistically significant changes in sperm parameters between the three differently treated samples and the control. After freezing in liquid nitrogen vapor, a significant difference in sperm motility across all observed semen samples was detected (Figure 1). The percentage of immotile spermatozoa was significantly higher in the control group compared to the subpopulation treated with vitamin C (p < 0.0001) and vitamin E (p < 0.05). The obtained results indicate that the addition of ascorbic acid in the extender was associated with a significant increase in the percentage of progressive (p < 0.05) and rapid spermatozoa (p < 0.01) compared to the LC-treated spermatozoa. Between samples supplemented treated with vitamin E and LC, a significant statistical difference in the motility parameters of the sperm cells was not observed. Vitamin C supplementation appears to improve sperm motility parameters, when compared to the other two supplements. These results suggest the potential of vitamin C to enhance specific sperm parameters, emphasizing the need for further research into the biochemical and molecular mechanisms through which ascorbic acid exerts its protective effects on spermatozoa movement patterns.

Figure 1.

Sperm motility assay after cryopreservation of immotile spermatozoa (IM %), non-progressive spermatozoa (NP %), progressive spermatozoa (PR %), and rapid spermatozoa (%). Ctrl-control, vit. C-treated—cryopreserved sperm subpopulation with vitamin C supplementation, vit. E-treated—cryopreserved spermatozoa with supplementation of vitamin E, LC-treated—cryopreserved spermatozoa with LC supplementation in extender. Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc Dunn test. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

3.2. Kinetic Assay

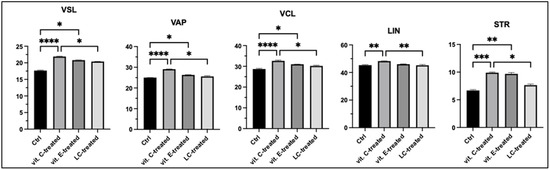

Cryogenic storage resulted in a substantial reduction in kinetic parameters across all samples compared to pre-freezing values, with CASA-derived semen parameters exhibiting significant variation, particularly in response to the different supplements compared to the control (Figure 2). Post-thaw spermatozoa kinetic analysis revealed the most significant changes in sperm curvilinear velocity, straight-line velocity, average path velocity, linearity, and straightness between the samples treated with vit. C and the control group (p < 0.0001) and between vit. C- and LC-treated samples (p < 0.05). No statistically significant difference was found between the groups treated with vitamin E and treated with LC. These findings underscore the profound impact of cryogenic storage on sperm functionality and highlight the differential effects of supplementation strategies on sperm metrics.

Figure 2.

Sperm kinetics assay after cryopreservation of curvilinear velocity (VCL µm/s), straight-line velocity (VSL µm/s), average path velocity (VAP µm/s), linearity (LIN = VSL/VCL %), and straightness (STR = VSL/VAP %). Ctrl—control, vit. C-treated—cryopreserved sperm samples with vitamin C supplementation, vit. E-treated—cryopreserved spermatozoa with supplementation of vitamin E, LC-treated—cryopreserved spermatozoa with LC supplementation in extender. Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc Dunn test. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

Alterations in the aforementioned evaluated sperm characteristics were observed across the four samples. The recorded parameters exhibited lowest values in the control. Specifically, spermatozoa supplemented with vitamin C demonstrated higher values in VCL, VSL, and VAP compared to the vitamin E- and LC-treated samples. In terms of movement trajectories, particularly linearity, spermatozoa supplemented with vitamin C achieved the highest percentage compared to LC-treated spermatozoa (p < 0.01). After freezing in liquid nitrogen and subsequent thawing, the STR parameter was highest in the vitamin C-treated group, followed by the vitamin E- and LC-treated samples. Vitamin C appears to improve sperm kinetics among the antioxidants evaluated, warranting its selection for further study. Our findings are consistent with those of other studies, highlighting a common trend in the challenges associated with the cryopreservation of spermatozoa [26,29,30]. The potential alterations in the preservation of biological integrity and reproductive competence of cryopreserved spermatozoa during liquid nitrogen storage emphasize the necessity for further rigorous and comprehensive scientific research.

4. Discussion

Drone spermatozoa are highly sensitive to the freeze–thaw process, resulting in considerable cell damage. Essential research into the mechanisms of action of antioxidants in the cryopreservation media is needed in order to improve outcomes in drone sperm cryopreservation. Despite the initial endeavors in the early 1980s, which yielded unsatisfactory outcomes, recent studies have revealed a concerning decline in drone gametes fertility post-thawing [31,32]. The results were in agreement with the findings of other authors, suggesting a consistent trend in the challenges faced in cryopreserving drone spermatozoa. Recent studies have shown that despite the retention of certain motility parameters post-thawing, there is a notable decline in fertility [33], underscoring the imperative need for novel supplementation strategies within cryopreservation media, particularly focusing on antioxidants.

Drone spermatozoa, residing within the queen’s spermatheca, exhibit sustained respiratory activity, thereby elevating the susceptibility to oxidative damage [34,35]. This heightened vulnerability is attributed to the reduced cytoplasmic volume and the abundance of unsaturated free acids within their plasma membrane, rendering them more prone to peroxidation compared to somatic cells, leading to lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and a diminished rate of sperm metabolism [36,37]. The inclusion of antioxidants in cryopreservation media serves to mitigate the impact of ROS on drone spermatozoa [38,39]. There is a pressing need for honey bee drone spermatozoa preservation to counter allelic losses caused by population declines linked to Varroa mites, Colony Collapse Disorder, and other threats [40]. However, utilizing preserved drone semen for instrumental insemination has yielded a worker production rate of only 47%, substantially lower than the desired 95–99%, indicating a low fertilization rate [32].

The toxicity of supplements employed as cryoprotective agents is a pivotal factor influencing the development of preservation protocols [39]. The inclusion of the commonly used DMSO has led to higher survival rates, establishing it as the preferred supplement in all studies on drone semen preservation to date [41]. Conversely, it has been noted that dimethyl sulfoxide can induce infertility in queens that are the offspring of treated sperm [42]. Additionally, the utilization of ethylene glycol has been demonstrated to decrease the viability of spermatozoa reaching the storage organ [41]. However, while storage prolongs the availability of sperm for fertilization, the fertilizing potential of frozen-thawed sperm is compromised due to alterations in the structure and physiology of the sperm cell. Our research investigates the impact of ascorbic acid, vitamin E, and LC supplementation during ultra-low temperature storage on sperm quality parameters. Vitamin C, functioning as an antioxidant, has the potential to positively affect specific sperm parameters and alleviate complications stemming from low temperatures. Oxidative stress during storage, whether in liquid or cryopreservation, can markedly reduce the number of viable spermatozoa by compromising their motility and quality [43].

Sperm is naturally endowed with particular small molecules that counteract free radicals, including carnitine, tyrosine, uric acid, and vitamin C, facilitated by secretions of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and pyridoxine along the male reproductive system. Extracellular antioxidants in sperm could play a pivotal role in safeguarding sperm membranes against oxidative stress [44,45,46,47]. Supplementation of vitamin C in sperm medium may confer advantages for direct swim-up-derived spermatozoa [31]. The oxidative stress encountered during sperm preparation and preservation processes may compromise sperm parameters.

Tocopherol is acknowledged for its role in enhancing male fertility. In vitro studies suggest that vitamin E supplementation could protect spermatozoa from the adverse effects of oxidative stress during preparation by preserving antioxidant processes under normal conditions [48]. Research findings indicate that higher levels of vitamin E supplementation are conducive to optimizing improvements in sperm parameters. Additionally, vitamin E has been reported to cooperate with antioxidant enzymes in preserving the functional competence of spermatozoa exposed to oxidative attacks [49]. In two studies from 2009 and 2016, their authors stated that vitamin E has been observed to enhance spermatozoa viability and reduce lipid peroxidation when subjected to oxidative stress inducers [49,50]. It is thought that vitamin E prevents membrane damage mediated by free radicals during sperm storage [51].

In addition, it has been reported that significant improvements in sperm parameters occur after antioxidant supplementation, including LC [52]. Research indicates that carnitines significantly enhance total motility, progressive motility, and sperm morphology, with no impact on sperm concentration. LC positively affects sperm motility, plasma membrane integrity, and mitochondrial function compared to sperm without added LC. Acrosome integrity is better preserved in the LC group compared to other sperm subpopulations. The antioxidant properties of LC may safeguard the mitochondrial membrane and DNA structure against ROS, maintain cellular homeostasis, limit the β-oxidation pathway, and facilitate the transport of fatty acids to mitochondria. LC supplementation in sperm-preserved media for buffalo, sheep, goat, rabbit, quail, and rooster semen cryopreservation has been shown to enhance the post-thawing quality of gametes [53,54,55]. Supplementary intake of LC and CoQ10 leads to improved hormonal profiles and enhanced sperm quality in rats [56]. LC is utilized as a supplement in cryopreservation extenders across various animal species and has been demonstrated to protect DNA and the mitochondrial membrane against reactive oxygen species (ROS) [54]. LC represents the sole biologically active carnitine isomer [56]. It modulates the transport of fatty acids to the mitochondria by facilitating the β-oxidation pathway, consequently maintaining cellular homeostasis [53].

Our research underscores the potential to optimize sperm preservation techniques by integrating antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and LC, thereby enhancing reproductive efficiency in drone populations via artificial insemination. The data suggest that the inclusion of vitamin C in the freezing medium plays a crucial role in preserving key sperm parameters following cryogenic storage. The results obtained from the presented study revealed that vitamin C supplementation in cryoprotective media improves drone sperm motility, kinematic parameters, and trajectory stability, which highlight its role as a valuable adjunct to improve the viability and functional quality of cryopreserved semen. The obtain result suggest that cryopreservation media supplemented with vitamin C improves sperm motility profile when compared to the other two supplements. This information highlights the potential perspective of the antioxidant as an enhancer of specific sperm kinetic parameters, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the mechanisms through which ascorbic acid exerts its protective effects on drone spermatozoa.

The research on vitamin C, vitamin E, and LC into cryopreservation extenders exhibits considerable potential for enhancing spermatozoa viability and fertilizing ability, thereby advancing reproductive biotechnologies and contributing to conservation initiatives. The role of cryobiology and the resulting reproductive biotechnology techniques in the preservation and reintroduction of a number of endangered species is widely used [57], but in the case of honey bees, must be explicitly emphasized. Similar approaches have already proven effective for some species in farms and zoological gardens [58]. Developing an effective media for long term cryopreservation of drone semen will provide an opportunity for the creation of genetic collections as ex situ reserve pool of honey bee populations [59]. However, while current analysis underscores the use of antioxidants in the cryorpreservation media for drone sperm cells, further research is required to determine the precise mechanisms by which these antioxidants optimize drone semen cryogenic storage protocols and facilitate consistent reproducible outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The preservation of bee colonies requires timely measures, given the challenges they face, namely changing climate conditions, poor colony management, and anthropogenic impacts on their natural habitats. Combining these factors with the spread of diseases and the reduction in natural immunity of bees as a result of the use of pesticides and monoculture practices requires the adoption of modern approaches for their conservation. Simplifying protocols for long-term ultra-low temperature storage of male bee gametes will facilitate the acquisition and storage of genetic material by beekeepers and will open the possibility of conducting artificial insemination practices in field and laboratory conditions. Modern cryopreservation techniques for drone spermatozoa have shown promising results in preserving the motility profile of the gametes. The incorporation of antioxidants into cryopreservation media is an essential element in preserving cells from ROS and the detrimental effects of low temperatures during cryopreservation. Further research in this direction would provide an opportunity to preserve the genetic diversity of honey bees and would deepen the knowledge of the effects of antioxidants during cryopreservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. and D.D.; methodology, T.T.; software, D.D. and T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by The Bulgarian National Science Fund (BNSF) in implementation of project No. KP-06 M66/6 of 15.12.2022/.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work is realized with the support of The Bulgarian National Science Fund (BNSF) in implementation of project No. KP-06 M66/6 of 15.12.2022/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| LC | L-carnitine |

| SCA | Sperm Class Analyzer |

| CASA | Computer-Assisted Sperm Analyzer |

| Ctrl | Control |

| IM | Immotile spermatozoa |

| NP | Non-progressive spermatozoa |

| PR | Progressive spermatozoa |

| VCL | Curvilinear velocity |

| VSL | Straight-line velocity |

| VAP | Average path velocity |

| LIN | Linearity |

| STR | Straightness |

References

- Kaviani, B.; Kulus, D. Cryopreservation of Endangered Ornamental Plants and Fruit Crops from Tropical and Subtropical Regions. Biology 2022, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, G.; Boettcher, P.; Besbes, B.; Danchin-Burge, C.; Baumung, R.; Hiemstra, S.J. Cryoconservation of Animal Genetic Resources in Europe and Two African Countries: A Gap Analysis. Diversity 2019, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella-Arnizaut, I.B.; Roeder, D.V.; Fenster, C.B. Use of botanical gardens as arks for conserving pollinators and plant-pollinator interactions: A case study from the United States Northern Great Plains. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2022, 31, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, J.; Boettcher, P.; Honkatukia, M. Innovations in Cryoconservation of Animal Geneticresources. Practical Guide; Food and Agcricultural Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023; pp. 1–277. [Google Scholar]

- Dziekonska, A.; Partyka, A. Current Status and Advances in Semen Preservation. Animals 2023, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkok, A.; Selçuk, M. Sperm storage and artificial insemination in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Int. J. Sci. Lett. 2020, 2, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulov, A.; Kaskinova, M.; Berezin, A.; Saltykov, E.; Lakrina, E. Creation of a Biobank of the Sperm of the Honey Bee Drones of Different Subspecies of Apis mellifera L. Animals 2023, 13, 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, S.; Finelli, R.; Agarwal, A. Reactive oxygen species in male reproduction: A boon or a bane? Andrologia 2021, 53, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanocka, D.; Kurpisz, M. Reactive oxygen species and sperm cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2004, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.; Gibb, Z.; Baker, A. Causes and consequences of oxidative stress in spermatozoa. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2016, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Agarwal, A. Oxidative stress and male infertility: From research bench to clinical practice. Andrology 2002, 23, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. The Role of the Natural antioxidant mechanism in sperm cells. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpour, R.; Jafari, R.; Tayef, N. The effect of antioxidant supplementation in semen extenders on semen quality and lipid peroxidation of chilled bull spermatozoa (short paper). Iranian J. Vet. Res. 2012, 13, 246–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cocchia, N.; Pasolini, M.; Mancini, R. Effect of sod (superoxide dismutase) protein supplementation in semen extenders on motility, viability, acrosome status and erk (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) protein phosphorylation of chilled stallion spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Prete, C.; Ciani, F.; Tafuri, S. Effect of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase supplementation in the extender on chilled semen of fertile and hypofertile dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 19, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, D.; Valcacia Silva Almeida, F.; Nunes, F.; Guerra, M. Effects of antioxidants and duration of pre-freezing equilibration on frozen-thawed ram semen. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, H.; Check, J.; Peymer, N.; Bollendorf, A. Effect of natural antioxidants tocopherol and ascorbic acids in maintenance of sperm activity during freeze-thaw process. Arch. Androl. 1994, 33, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbarzadeh, S.; Garjani, A.; Ziaee, M.; Khorrami, A. Coq10 and l-carnitine attenuate the effect of high ldl and oxidized ldl on spermatogenesis in male rats. Drug Res. 2014, 64, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K. Vitamin E and oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 11, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E. Action of ascorbic acid as a scavenger of active and stable oxygen radicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Ball, A. Effect of (alpha)-tocopherol and tocopherol succinate on lipid peroxidation in equine spermatozoa. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2005, 87, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, S.; Bicudo, D.; Sicherle, C. Lipid peroxidation and generation of hydrogen peroxide in frozen-thawed ram semen cryopreserved in extenders with antioxidants. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 122, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Gil, M.; Carvajal, E.; Cuello, G. Survival and in vitro fertility of boar spermatozoa frozen in the presence of superoxide dismutase and/orcatalasa. Andrology 2005, 26, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford Clarendon Press: Leicester, UK, 1999; pp. 1–936. [Google Scholar]

- Jedrzejowska, R.; Wolski, J.; Hilczer, J. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in male fertility. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2013, 66, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M.R.; Kohram, H.; Zare Shahaneh, A.; Zhandi, M.; Sharideh, H.; Nabi, M.M. The effects of different levels of vitamin E and vitamin C in modified Beltsville extender on rooster post-thawed sperm quality. Cell Tissue Bank. 2015, 16, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer, P.B.; Bucak, M.N.; Büyükleblebici, S.; Sarıözkan, S.; Yeni, D.; Eken, A.; Akalın, P.P.; Kinet, H.; Avdatek, F.; Fidan, A.F.; et al. The effect of cysteine and glutathione on sperm and oxidative stress parameters of post-thawed bull semen. Cryobiology 2010, 61, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metz, B.N.; Tarpy, D.R. Reproductive and Morphological Quality of Commercial Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Drones in the United States. J. Insect Sci. 2021, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, G.; Mansour, J.; Ibrahim, R.; Azoury, J.; Azoury, J.; Mourad, M.; Azoury, J. What are the effects of vitamin C on sperm functional properties during direct swim-up procedure? Zygote 2019, 27, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, A.; Hassan, B.; Aitken, R. Addition of vitamin C mitigates the loss of antioxidant capacity, vitality and DNA integrity in cryopreserved human Semen samples. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbo, J.R. Survival of honey bee (Hymenoptera, Apidae) spermatozoa after 2 years in liquid-nitrogen (−196 °C). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1983, 76, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftanoglu, O.; Peng, Y. Preservation of honey-bee spermatozoa in liquid nitrogen. J. Apic. Res. 1984, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobey, S.; Tarpy, D.; Woyke, J. Standard methods for instrumental insemination of Apis mellifera queens. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.M.; Williams, V.; Evans, J.D. Sperm storage and antioxidative enzyme expression in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Insect Mol. Biol. 2004, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirich, G.F.; Collins, A.M.; Williams, V.P. Antioxidant enzymes in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Apidologie 2002, 33, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, L.R. An ionic basis for a possible mechanism of sperm survival in the spermatheca of the queen honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Physiol. 1973, 44, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pertusa, J.; Yaniz, J.L.; Nunez, J.; Soler, C.; Silvestre, M.A. Effect of different oxidative stress degrees generated by hydrogen peroxide on motility and DNA fragmentation of zebrafish (Danio rerio) spermatozoa. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcay, S.; Cakmak, S.; Cakmak, I.; Mulkpinar, E.; Gokce, E.; Ustuner, B.; Sen, H.; Nur, Z. Successful cryopreservation of honey bee drone spermatozoa with royal jelly supplemented extenders. Cryobiology 2019, 87, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Guzmán-Novoa, E.; Morfin, N.; Buhr, M. Improving viability of cryopreserved honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) sperm with selected diluents, cryoprotectants, and semen dilution ratios. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.K.; Herr, C. Factors affecting the successful cryopreservation of honey bee (Apis mellifera) spermatozoa. Apidologie 2010, 41, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, J.; Bienefeld, K. Toxicity of cryoprotectants to honey bee semen and queens. Theriogenology 2012, 3, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbo, R. Sterility in honey bees caused by dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Hered. 1986, 77, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comish, P.; Drumond, A.; Kinnell, H.; Anderson, R.; Matin, A.; Meistrich, M. Fetal cyclophosphamide exposure induces testicular cancer and reduced spermatogenesis and ovarian follicle numbers in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Sterling, E.; Young, I.; Thompson, W. Comparison of individual antioxidants of sperm and seminal plasma in fertile and infertile men. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 67, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showell, M.; Mackenzie-Proctor, M.; Brown, J.; Yazdani, A.; Stankiewicz, M.; Hart, R. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, F.; Sansone, A.; Romanelli, F.; Paoli, D.; Gandini, L.; Lenzi, A. The role of antioxidant therapy in the treatment of male infertility. Asian J. Androl. 2011, 13, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanian, S.; Farahbod, F.; Rafieian, M.; Ganji, F.; Adib, A. The effects of Vitamin C on sperm quality parameters in laboratory rats following long-term exposure to cyclophosphamide. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2017, 8, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarizadeh, A.A.; Malmir, M.; Naderi Noreini, S.; Faraji, T.; Ebrahimi, Z. The effect of vitamin E on sperm motility and viability in asthenoteratozoospermic men: In vitro study. Andrologia 2021, 53, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daramola, J.; Adekunle, E.; Oke, O.; Ogundele, O.; Saanu, E.; Odeyemi, A. Effect of vitamin E on sperm and oxidative stress parameters of West African Dwarf goat bucks. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2016, 19, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.G.; Bilaspuri, G. Antioxidant effect of vitamin E on motility, viability and lipid peroxidationof cattle spermatozoa under oxidative stress. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2009, 27, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gurel, A.; Coskun, O.; Armutcu, F.; Kanter, M.; Ozen, O. Vitamin E against oxidative damage caused by formaldehyde in frontal cortex and hippocampus: Biochemical and histological studies. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2005, 29, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, L.; Salehpour, S.; Hosseini, S.; Allameh, F.; Jahanmardi, F.; Azizi, E.; Hashemi, T. Effect of antioxidant supplementation containing L-carnitine on semen parameters: A prospective interventional study. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2021, 25, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerolini, S.; Zaniboni, L.; Maldjian, A.; Gliozzi, T. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid and a-tocopherol enrichment in chicken sperm on semen quality, sperm lipid composition and susceptibility to peroxidation. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, A.; Sharafi, M.; Masoudi, R.; Shahverdi, A.; Esmaeili, V.; Najafi, A. L-Carnitine in rooster semen cryopreservation: Flow cytometric, biochemical and motion findings for frozen-thawed sperm. Cryobiology 2017, 74, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, S.; Corduk, M.; Suicmez, M.; Cedden, F.; Yildirim MKilinc, K. The effects of dietary L-carnitine supplementation on semen traits, reproductive parameters, and testicular histology of Japanese quail breeders. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2007, 16, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Z.; Imani, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Mofid, M.; Dashtnavard, H. Effect of oral L-carnitine on testicular tissue, sperm parameters and daily production of sperm in adult mouse. Yakhteh Med. J. 2009, 11, 382–389. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, S.; McManus, C.; Blackburn, H. Conservation of animal genetic resources: A new tact. Livest. Sci. 2016, 193, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, H.; Maxwell, C. A review on reproductive biotechnologies for conservation of endangered mammalian species. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2007, 99, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryła, M.; Trzcińska, M.; Samiec, M.; Kralka-Tabak, M. The Importance of In Situ and Ex Situ Protection of Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) in Poland with Emphasis on Drone Semen Cryopreservation—A Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2025, 25, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).