Abstract

The spread of disinformation and the subsequent social pushback have elevated fact-checking to a core activity in modern newsrooms. Amid efforts to rebuild public trust, news media and dedicated organizations have expanded verification routines, institutionalizing fact-checking—a process globally stress-tested during the COVID-19 crisis. We conducted a content analysis of 25 fact-checking outlets’ public websites across Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany. Across cases, we identified a dual content strategy: (a) routine fact-checks targeting circulating falsehoods, and (b) complementary contextual pieces (explainers, in-depth reports, and analyses) that frame issues and processes. Both layers adhere to a shared culture of method, format, and transparency, often reflected in standards like IFCN and EFCSN, though methodological transparency remains an area for improvement. These outlets primarily focused on online disinformation but also monitored public discourse, with several showing degrees of topical or procedural specialization. These findings suggest that European fact-checking has matured into a hybrid model that combines routine debunking with context-building journalism under common professional norms, while requiring clearer methodological disclosure and cross-platform consolidation.

1. Introduction

The rise in disinformation in the networked society has placed fact-checking at the centre of debate, yet comparative studies that explain how its content strategy is configured remain scarce. To bridge this gap, we conduct a content analysis of the websites of 25 fact-checking organizations from Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany. This study outlines their dual strategy—verifications and “contextual content”—and their areas of specialization: either monitoring political discourse—first-wave fact-checking—or combating online disinformation—second-wave fact-checking (Graves, 2022).

1.1. Digital Journalism: Challenges, Competencies, and Social Function

The adaptation of journalism to the new digital environment has led to the emergence of new professional profiles that now play a central role in the production of news messages. Required to undergo continuous training in order to face the challenges of a complex and hybrid communication system (Chadwick, 2017), journalists have demonstrated their ability to produce information across multiple supports, channels, and formats, without renouncing the foundational principles of social communication. The social and communicative context frames current journalistic practices, which incorporate innovative processes (Sixto-García & López-García, 2023) to a greater or lesser extent depending on the territory.

Digital journalism is more than just a consolidated professional and academic field (Salaverría, 2019); in a context where disinformation threatens the proper functioning of democratic systems, digital journalism has also become one of the main mechanisms for mitigating that risk (Farkas, 2023). The rise in active audiences capable of producing content (Masip et al., 2019) and the popularization of social media platforms (Gil de Zúñiga & Cheng, 2021) have contributed to the consolidation of a platform society (van Dijck et al., 2018), which, together with media digitalisation and the spread of fake news, is challenging the social role and authority of journalism (Ekström et al., 2020).

In response, both media organizations and institutions committed to strengthening quality journalism—grounded in procedural transparency and greater audience participation (Amazeen, 2019; Graves, 2016)—have launched initiatives aimed at improving verification techniques and developing new tools that allow citizens to check the truthfulness of information. With new actors and new techniques in communication processes, contemporary digital journalism plays an essential role as a shield against disinformation (Martín García & Buitrago, 2022).

1.2. Fact-Checking: A Time-Honoured Journalistic Tool Renewed to Combat Disinformation

Although the term “post-truth” was not new when the Oxford Dictionaries selected it as the word of the year in 2016, that moment—marked by the impact of disinformation on processes such as the Brexit referendum or Donald Trump’s presidential campaign—triggered social alarms about the risks posed by online disinformation (Mantzarlis, 2018; Casero-Ripollés, 2018; Guallar et al., 2020; Adams et al., 2023).

The rise in citizens’ concerns about disinformation has led to the creation of new fact-checking tools. Fact-checking, which is the essence of journalism (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2014), requires traditional techniques to be updated and better tools to be introduced. In their view of journalistic roles in political and daily life (Hanitzsch & Vos, 2018), journalism researchers maintain that fact-checking is the backbone of this social communication technique, as they distinguish between classic, in-house verification—conducted before publication—and modern, external verification that targets either public discourse or online content (Mantzarlis, 2018; Redondo Escudero, 2018).

Changes in the communication ecosystem have also shaped newsroom attitudes toward fact-checking. In this context, the digitalisation of real-time journalism and the multiplication of sources has fostered the emergence of second-wave fact-checking—specialized in detecting and debunking online disinformation—which has evolved into a new journalistic genre or speciality (Cazzamatta, 2025b; Graves, 2022) and is now moving toward a process of institutionalization (L. Lauer & Graves, 2024).

Fact-checking has become an essential tool in combating disinformation in areas such as health—especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2025)—and politics (Liu et al., 2023). Numerous platforms (Vizoso & Vázquez-Herrero, 2019) and empirical studies support its effectiveness in reducing citizens’ misperceptions (Carey et al., 2022; Cotter et al., 2022; Costa-Sánchez et al., 2023). However, challenges remain due to the greater virality of false messages compared to accurate information (Singer, 2018; King & Wang, 2023).

Although verification is a core component of all journalistic practice, the current context has led to the emergence of a new specialization: a renewed form of watchdog journalism aimed at correcting long-standing weaknesses in digital journalism (Singer, 2018). Nevertheless, the growing importance of social media monitoring and the adoption of explanatory formats (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023) are fostering a diversification of roles (Ferracioli et al., 2022; Riedlinger et al., 2024), suggesting a process of maturation within this journalistic modality.

Despite the variety of approaches (Tejedor et al., 2024; Suomalainen et al., 2025), empirical evidence highlights substantial progress in quality journalism and the fight against disinformation (Moreno-Gil et al., 2022; López-Marcos & Vicente-Fernández, 2021; Martín-Neira et al., 2023) through fact-checking. During the pandemic, there were numerous cases in which the work of fact-checkers proved decisive (León et al., 2022).

1.3. Fact-Checking: The State of Play

With the aim of fact-checking public discourse (Mantzarlis, 2018), the early 2000s saw the advent and consolidation of ex-post fact-checking in the United States, with three of the so-called “forerunners” leading the way (Graves, 2016): FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, and The Washington Post Fact-Checker. Fact-checking, as an innovative tool for improving democratic well-being, has become a transnational movement in journalism (Graves, 2018; L. G. Lauer, 2021; Moreno-Gil et al., 2022). The outcome is a global fact-checking movement with the aim to combat online disinformation (Abuín-Penas et al., 2023), with Europe now being one of the regions with the highest number of related projects: 125 active ones, according to the Fact-checking—Duke Reporters’ Lab database (Fact-Checking—Duke Reporters’ Lab, 2014). As European fact-checkers joined what Graves (2018) calls the “fact-checking movement”, with their distinct professional cultures yet common methods (Koliska & Roberts, 2024), they also displayed a diversity which can be analyzed by paying attention to its organizational roots and operating procedures—content strategy, transparency, thematic focus, and informational outputs (Mahl et al., 2024).

Following Hallin and Mancini (2004), initiatives led by legacy media were pivotal in rolling out fact-checking across Atlantic and Northern Europe, with world-renowned organizations such as BBC Verify, Reuters Fact Check, Channel 4 FactCheck, ZDFheuteCheck, dpa-faktencheck, and AFP Faktencheck at the forefront. Nonetheless, both models also feature prominent examples of independent fact-checking, such as Fullfact. In Mediterranean Europe, numerous independent ventures—Maldita, Newtral, Pagella Politica, and Facta, among others—have become key fact-checking brands; they typically partner with established media either for funding or to broaden their audience reach. France, which also falls under the Mediterranean model, shows a mixed landscape: major traditional outlets have launched fact-checking projects, Les Décodeurs (Le Monde) and Vrai ou Fake (France Info), while several independent initiatives such as Les Surligneurs have also gained prominence. Far from being a minor issue, the media systems in which fact-checkers operate are defining of their strategy. Recent studies show that verification practices are deeply conditioned by the structure of the media systems in which they operate. Thus, in the liberal model, fact-checkers tend to consolidate greater levels of organizational independence and financial stability, which also influences audience response to the content published by fact-checkers and the relationship between media and citizens (Cushion et al., 2021). In the pluralist polarized Mediterranean, routines and content selection are more affected by political parallelism and the need for collaboration with traditional media (López-Marcos & Vicente-Fernández, 2021; Magallón-Rosa, 2018).

In contrast, a political and civic approach to fact-checking is found in Eastern European countries, mainly the Balkans and countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union. The fight against Russian disinformation strategies as well as efforts to consolidate a greater and better democratic culture in their countries mark the character of these projects (Graves, 2018). The following should be cited: StopFake, VoxCheck and FactCheck Ukraine (Ukraine), FactCheck Georgia (Georgia), Funky Citizen (Romania), and Zašto ne? (Why not?) (Bosnia).

The fact that many of the projects cited are signatories to the Code of Principles of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) is probably the greatest exponent of an ongoing process of institutionalization (L. Lauer & Graves, 2024). Numerous fact-checking projects in Europe reinforce this dynamic: they operate with increasingly formalized routines, robust methodologies, and multi-layered workflow controls, strengthening their professional identity despite structural constraints such as resource scarcity or political polarization (Moreno-Gil et al., 2022). The IFCN seal requires data fact-checkers to comply with certain standards on independence and transparency of methodology, sources, funding, and correction policies. This quality seal is not without its problems, since in practice the connections between fact-checkers and their alliance policies are not fully transparent (Esteban-Navarro et al., 2021). At the European level, it is essential to mention the European Data Verification Standards Network (EFCSN), a network composed of 49 data verifiers from various countries (European Fact-Checking Standards Network [EFCSN], 2024).

In today’s landscape of information overload and the growing distrust of legacy media, transparency, methodological rigour, and audience empowerment have become key strategies for restoring trust and credibility, elements essential for any outlet’s survival as the fourth estate and a cornerstone of democratic functioning. Notably, there are significant differences in how, and to what extent, individual news organizations apply these transparency measures (Humprecht, 2020; Kumar, 2024; Seet & Tandoc, 2024; Ye, 2023).

The informational output of fact-checking outlets follows two broad lines: those that deploy truth scales—pioneered by PolitiFact’s Truth-O-Meter and The Washington Post Fact-Checker’s Pinocchios—and those following the example of FactCheck.org, which favour detailed textual explanations with no visual labelling. Vizoso and Vázquez-Herrero (2019) distil these alternatives into three complementary formats: textual verdicts, visual elements (emojis, icons), and graduated colour scales. In Europe, most fact-checkers employ some type of graduated scale, while systems that apply labels to indicate degrees of error or verdicts delivered solely through extended text are secondary options (Graves & Cherubini, 2016).

This is one of the main points of debate within the fact-checking community: while some organizations view truth scales as a powerful and effective way to reach audiences, others argue that they can be reductionist and oversimplify events for citizens (Graves, 2016). Public service media, in particular, often express reservations about using blunt labels such as “Lie” or “False” when concerning public officials or politicians (Graves, 2018).

Fact-checkers have also broadened their product catalogue toward content framed within explanatory journalism (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023; Riedlinger et al., 2024), offering context beyond straightforward debunking through thematic reportages, interactive infographics, and data visualizations, a practice first popularized by Les Décodeurs, which is a strategy aimed at avoiding the backfire effect (Cook & Lewandowsky, 2012) and is more closely aligned with prebunking approaches (Butcher & Neidhardt, 2021).

The global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by what became popularly known as an “infodemic” (León et al., 2022), though the metaphor is increasingly questioned due to the complexity of the phenomenon (Simon & Camargo, 2021). The crisis was characterized by social panic and high uncertainty (Casero-Ripollés, 2021). Combating disinformation—now a societal priority—requires not only addressing false news, especially given the pandemic’s impact (Calvo-Gutiérrez & Marín-Lladó, 2023) but also restoring trust in truthful information (van der Meer et al., 2023). This effort entails strengthening media literacy (Robinson et al., 2021) and improving journalists’ critical thinking and technological skills (Reed et al., 2020). In this context, the work of fact-checkers in Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany is especially relevant due to the number and significance of the projects involved.

So, the aim of this research is to understand the strategy used by European fact-checkers to combat misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this goal, the focus is placed on four key elements: content strategy, verification formats, transparency, and types of disinformation. The research questions are as follows:

- RQ1. Which types of informational outputs were most frequently produced by the fact-checkers in the sample during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ2. Do the fact-checkers in the sample comply with the standards of source transparency, methodological transparency, and correction transparency set out in the widely adopted guidelines of the IFCN and the EFCSN?

- RQ3. Do they use their own verification formats—scales, labels, or verdicts—and how prominent are they in their strategy?

- RQ4. What were the types of disinformation that fact-checkers focused on during the pandemic?

2. Materials and Methods

Based on these questions, an analysis sheet was developed, incorporating the following parameters:

- Content type: Determine whether fact-checkers produce fact-checks and/or contextual content.

- Fact-checks: Any publication issued by a fact-checker that, within a specific format, aims to detect and debunk disinformation of any kind by identifying a potential piece of disinformation (whether a statement or online content), delivering a verdict on it (possibly via a truthfulness scale), and, where relevant, offering an explanatory account of the process with the sources consulted (Graves, 2016; Pavleska et al., 2018).

- Contextual content: All materials published by fact-checkers in formats other than the standard fact-check, designed either to provide breaking news or to furnish audiences with deeper, broader knowledge of a topic. These pieces largely correspond to traditional journalistic genres (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023).

- Fact-check formats: One of the main innovations of fact-checking has been the introduction of truthfulness scales to assess the factual legitimacy of a piece of content. It was, in fact, a fundamental element in establishing fact-checking as a distinct practice in its origins. The Washington Post Fact-Checker’s “Pinocchios” and Politifact’s “Truth-O-Meter” are iconic examples (Álvarez Gromaz & López García, 2016; Drobnic-Holan, 2024). Verification scales can be categorized into four types, inspired by the model of Vizoso and Vázquez-Herrero (2019):

- Textual scale + Textual description: The verdict is resolved with a short sentence or word (e.g., False, True, Misleading). It is complemented by an extensive textual development.

- Visual scale + textual Description: The verdict is depicted with graphical elements (figures, icons) representative of the verdict. It is complemented by an extensive textual explanation.

- Colour scale + Textual description: The degree of veracity is associated with a colour scale. It is complemented with an extensive textual development.

- Textual description only: No scale is incorporated; verification is conveyed solely through an extensive textual development.

- Transparency: Three parameters are incorporated, which are access to fact-checking methodology, access to sources, and access to corrections. Drawing on web-usability standards (Nielsen, 2000) and the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 (2018), we assume that transparency is more effective when it is accessible and usable (one click away). It signals a commitment to traceability and spares the audience from navigating the site in search of a separate corporate page.

- Access to fact-checking methodology: There are one or more highlighted hyperlinks to the methodology used to perform the verification.

- Access to sources: There are one or more highlighted hyperlinks leading to the sources used for the verification.

- Access to corrections: There are one or more prominent hyperlinks leading to pages or forms where the user can exercise claims to review the verifications.

- Main format of the content published by fact-checkers: Distinction between text, audio, audiovisual, and infographic.

- Type of disinformation: The classification by Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) is used, which includes satire or parody, misleading content, impostor content, fabricated content, false connection, false context, and manipulated content. The classification is completed with “Does not appear” and “Several results”.

For coding, the authors applied an initial pilot phase that allowed the codebook to be adjusted (see Supplementary Materials). After this, a part of the sample was coded independently by two researchers. Three publications were chosen per medium. Discrepancies were reviewed in joint sessions, iteratively refining the definitions before proceeding to the full coding of the corpus. The sample is based on 2410 publications made in 2021—during which a complete and particularly intense pandemic cycle occurred, which includes the vaccine rollout and three major infection waves (third, fourth and fifth)—on the websites of 25 European fact-checkers, accessed via the desktop web version. The data source for the sample was the Duke’s Reporters Lab database. The selection focused on Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany. These five countries were chosen to secure a representative spread across the three media system models identified by Hallin and Mancini (2004), while also being globally recognized democracies with diverse, well-established media ecosystems that have enabled numerous fact-checking initiatives to flourish.

Outlets were chosen from the Duke’s Reporters Lab database. To size and standardize the sample in each country, we applied two relevance indicators: (a) the Sistrix Visibility Index, which measures a site’s performance in search-engine results, and (b) content volume (more than 50 pieces on coronavirus in the sample year). Membership/non-membership of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) and the European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN) was also considered (but not exclusionary). After applying these criteria, we retained the five outlets with the highest visibility scores with enough content volume in each country, yielding a balanced sample of 25 fact-checkers.

Two methods were used for content extraction. First, the Sistrix explorer, by creating a database of 100 random URLs corresponding to searches such as “coronavirus,” “COVID”, “pandemic,” or “vaccine” (with the respective translation in each country), and framed in the year 2021. Once the full sample was compiled, a threshold of 100 publications was established to ensure meaningful results; as in most cases, this number represented more than 30% of all content published about coronavirus during the period under analysis. The second method involved manual extraction. This latter approach was applied when Sistrix yielded few or no relevant results. Manual extraction proceeded as follows:

In the case of outlets with more than 100 COVID-19-related publications, manual extraction yielded large datasets, from which a random sample of 100 items was selected. This applied to BR24 #Faktenfuchs (117 publications), BBC Verify (120 publications), and Les Verificateurs (393 publications).

For outlets with fewer than 100 publications during 2021, all available COVID-19-related URLs within the main fact-checking categories were extracted. This was the case for ZDFheuteCheck (54 publications) and Channel 4 FactCheck (63 publications). The analysis sheet, in the form of a spreadsheet, can be found in the Supplementary Material of this work. The results are as follows in Table 1:

Table 1.

List of fact-checkers in the sample. Own compilation.

3. Results

3.1. Fact-Checks Are the Majority Content, but Several Fact-Checkers Incorporate Dual Strategies by Also Using Contextual Content

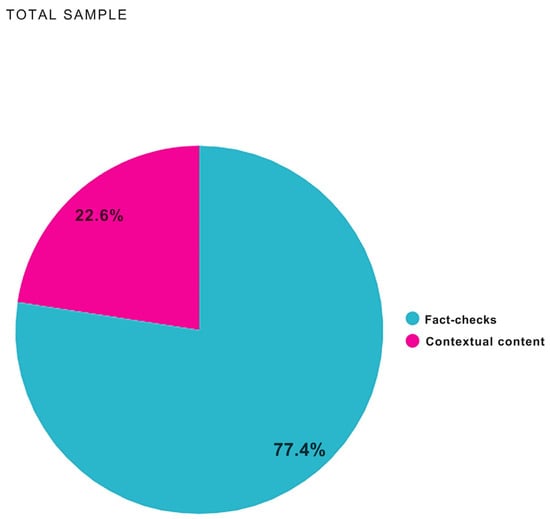

During the COVID-19 pandemic, European fact-checkers exhibited a dual content strategy. Besides fact-checks, the strategy was enriched with other journalistic genres, categorised as “contextual content”. Thus, most of the content published in the analysis period corresponded to fact-checks (77.4%), with contextual content accounting for 22.6% of the total. Figure 1 reflects this distribution.

Figure 1.

Type of content published in total sample: fact-checks vs. contextual content. Own compilation.

Taking into consideration the criterion of affiliation or origin, fact-checking continued to predominate among fact-checkers, be they linked to media organizations (81%), independent (70.1%), or NGO (92%). Contextual content had a higher presence among independent fact-checkers, which could be explained by the structure of their websites that incorporated large sections containing reports and analysis. This element was a minority among fact-checkers linked to media organizations, since contextual content falls outside the scope of the fact-checking section in the majority of cases. Table 2 illustrates this.

Table 2.

Contextual content vs. fact-checks among the sample’s independent fact-checkers. Own compilation. The table is sorted in descending order based on the volume of contextual content.

The percentage of contextual content was above 30% among four of the nine media in this group. In the case of Maldita, it was 28%. In any event, the percentage of contextual content presented by some of the media linked to legacy media organizations was by no means negligible, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Contextual content vs. fact-checks among the sample’s fact-checkers linked to media organizations. Own compilation. The table is sorted in descending order based on the volume of contextual content.

The percentages for BBC Verify (36%), Channel 4 FactCheck (41.27%), Les Décodeurs (54%), and ZDFheuteCheck (88.89%) were significant. In the case of the latter two, the structural issue of their respective websites was reproduced. The clearest example was the French fact-checker, whose website has its own architecture, which is not integrated into Le Monde and is wholly focused on expanding on news stories with data. A detailed review of this content exposed a key issue: fact-checkers used in-depth reports as the best way to elaborate on complex coronavirus stories, widening public understanding of every topic that surfaced. Its presence was higher than 53% in the contextual content of independent fact-checkers and 74% in the case of fact-checkers linked to media organizations. Overall, the percentage represented 64.3% of the publications.

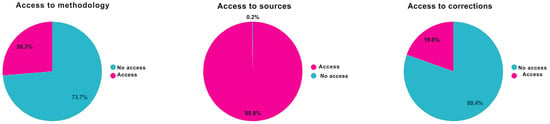

3.2. Parameters for Methodological Transparency Present Opportunities for Enhancement

Transparency is central to fact-checkers’ legitimacy and is the key benchmark in the IFCN Code of Principles. Within our sample, all but four outlets—BBC Verify, Channel 4 FactCheck, ZDFheuteCheck, and Bufale—are signatories. EFCSN membership is more limited, covering every Spanish outlet: Italy’s Pagella Politica and Facta, the UK’s FullFact, and Germany’s AFP Faktencheck and dpa-Faktencheck, while no French outlet has yet joined. We analyzed each organization’s transparency through three parameters: public access to methodology, sources used, and published corrections. Figure 2 shows the results:

Figure 2.

European fact-checkers’ transparency: access to methodology, sources, and corrections. Own compilation.

The near total transparency of access to sources was evident (99.8%). Such access was manifested through links that were either placed in the development of the fact-check itself, or listed at the end of the written piece, or a combination of both. There is strict compliance by fact-checkers with this parameter. As expected, during the COVID-19 pandemic, official sources (32.9%) were the fact-checkers’ main news stream, followed by newspaper archives (24.2%), experts (13.9%), and the scientific literature (9.8%).

The fact-checkers’ fervour regarding the transparency of sources was not reflected in the other two parameters: access to methodology was 26.3%, while access to corrections was 19.6%. Six outlets break this generic trend: CheckNews (100%), CORRECTIV (100%), Reuters (100%), Verificat (100%), Maldita (86%), and Newtral (41%). Meanwhile, independent fact-checkers’ involvement in fulfilling these parameters was found to be greater: access to methodology was 32.5%, and access to corrections was 25.6%. Among legacy media fact-checkers, the percentages were lower, at 16.9% and 17.9%, respectively. Figure 3 shows examples of access banners to methodology in some sample outlets.

Figure 3.

Access banners to methodology in sample outlets: Maldita, Verificat, Newtral, CheckNews. Source: maldita.es, verificat.cat, newtral.es, liberation.fr.

However, the incorporation of certain elements of transparency in the textual explanations of the fact-checks themselves should be noted. Moreover, a lack of direct access did not imply that information on methodology and corrections was non-existent, as this was usually included in pages such as “About us”.

3.3. Personalisation and Branding in the Implementation of Truthfulness Scales

The results show the spread of the truthfulness scale model to 20 of the 25 media in our sample, with a presence in 67.4% of published content, whereas the remaining 32.6% was supported by textual descriptions. In this sense, the French fact-checkers were those that spurned truthfulness scales the most, the presence of which was found in just 10.2% of the published fact-checks. The rest were characterized by broad diversity. Colour scales predominated (37.6%) in the overall sample. Their presence predominated in Spain (56.7%) and Italy (81.4%). Textual scales accounted for 21% of the published fact-checks and were the most frequent in the United Kingdom (48.3%). Lastly, visual scales were present in 8.8% of the fact-checks, with Germany being the country where they were most frequent in percentage terms (29.2%).

Most fact-checkers adopt one or two formats but typically rely on a single one; its truthfulness scale acts as branding, helping audiences recognize their work at a glance. The hybridisation of these formats is worth noting, with elements from visual scales being combined with elements from textual scales. Despite such variety, European fact-check formats have no marketing agenda; they exist exclusively to provide accurate, accessible information. Textual development was found to be present in all fact-checks: text was the main format in 97.1% of the published fact-checks.

3.4. European Fact-Checkers Focus on Online Disinformation

The last parameter of analysis was the most frequent type of disinformation appearing in the sample’s fact-checks. Figure 4 depicts the landscape.

Figure 4.

Types of disinformation. Segmentation: national vs. total sample. Own compilation.

Fabricated content was the most frequent type (35%), followed by false context (13%), not listed (12.1%) and misleading content (10.9%). In overall terms, the attention paid to any type of disinformation, regardless of its higher or lower percentage of presence, was evident. However, when comparing individual fact-checkers, strategic differences became apparent. Such is the case of BBC Verify, with 46.9% of its fact-checks pertaining to the field of political fact-checking; or of CheckNews, whose strategy revolved around resolving community queries, which, in many instances, did not involve the presence of any type of disinformation (42.6%). In any event, most of the media in the sample had a hybrid fact-checking model, with more or less attention being paid to political fact-checking, where the focus was on looking for and debunking any kind of online disinformation.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this article was to analyze in detail the work undertaken by European fact-checkers in five countries—Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany—during the pandemic. The analysis placed attention on the fundamental aspects of fact-checking: content strategy, transparency, fact-check formats, and types of disinformation. The objectives of the study and the research questions have been resolved, allowing us to comment on relevant conclusions.

Firstly, during the pandemic, fact-checkers concentrated most of their efforts on producing fact-checks to counteract the surge of infodemic content that burst into the online sphere throughout this period. The ratio of 77.4% verifications/22.6% contextual content shows that fact-checks continue to be, in most of the media analyzed, the core of their activity. The proportion detected suggests that COVID-19 acted as a critical event that accelerated editorial innovation and pushed organizations to experiment with formats to combat a massive and mutating volume of disinformation. Fact-checkers recognize the limits of the strict format and have articulated a more hybrid response, combining factual analysis with interpretive and explanatory content. Thus, content analysis reveals distinct content strategies. On one hand, there are fact-checkers whose production is based almost exclusively on fact-checks. These are generally specific departments within legacy media outlets, such as Reuters Fact Check, AFP Factual, and EFE Verifica.

On the other hand, some fact-checkers develop a more complex content strategy, balancing production efforts between verifications and contextual content—such as in-depth reports, analyses, interviews, and chronicles. Comparative work on correction strategies across countries confirms the existence of this hybrid model (Cazzamatta, 2025a), while reinforcing explanatory approaches espoused by European platforms in the post-COVID-19 era (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023; Butcher & Neidhardt, 2021).

News stories like “Variante británica: más contagiosa, no más grave e igual ante las vacunas” [British variant: more contagious, not more serious, and the same when it comes to vaccines] (Viciosa, 2021) and “Les idées claires sur le COVID-19: l’origine du virus” [clear ideas about COVID-19: the origin of the virus] (Vaudano et al., 2021) are examples of this line of action, whose aim was to complement and overcome the limitations of fact-checking work and to provide context and knowledge about coronavirus (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023).

This strategy seeks to foster knowledge within the community, providing detailed and in-depth information on various pandemic-related topics while incorporating elements of media literacy and digital competence (García-Ruiz et al., 2014), a trend also observed in the Global South (Riedlinger et al., 2024). The coexistence of strict fact-checking and other journalistic genres suggests a maturation of the field: fact-checkers not only respond to specific disinformation but also produce explanatory content that contextualizes social, health, and political problems. Independent fact-checkers are prevalent in this category—Newtral, Maldita, Pagella Politica—though there are also notable examples among traditional media outlets, such as Les Décodeurs and BBC Verify. It is relevant that this maturation is occurring across the board, regardless of the media system in which each medium operates (Hallin & Mancini, 2004). This connects to the following point: the institutionalization of fact-checking.

The results confirmed that the European fact-checkers identified with the global fact-checking movement (Graves, 2018; Graves & Cherubini, 2016). Such identification manifested itself in a series of common practices and elements in the vast majority of the fact-checkers analyzed—clear path of homogenization (Cazzamatta, 2025b)—one of the main ones being that 21 of the 25 media in the sample were signatories to the IFCN Code of Principles, which deepens the idea of institutionalization (L. Lauer & Graves, 2024). For its part, the EFCSN includes 9 of the 25 outlets. The expansion of the IFCN and EFCSN among European fact-checkers suggests a trend towards formalization and regulation of the sector, which may impact relations with digital platforms, public disinformation policies, and information governance at the European level. Transparency and independence are the parameters governing the IFCN and EFCSN seals, which serve to legitimize the signatories’ actions in the eyes of the audience, thereby seeking the previously mentioned restoration of public trust in journalism (van der Meer et al., 2023). This is a fundamental issue for fact-checkers, who need to establish innovative approaches to overcome the biases and cognitive barriers users may activate when confronted with verifications (Ivask, 2024). This is especially critical for independent fact-checkers, whose economic viability depends largely on building broad, loyal, and trusting communities (López-Borrull & Sanz-Martos, 2019).

However, this study’s assessment of the transparency parameters revealed the need for the fact-checkers to make refinements in relation to the placement of elements for direct access to the methodology and corrections sections. Transparency of sources was found in the entire sample. Thus, while there remains room for improvement across the entire sample, independent fact-checkers—and particularly those operating under the EFCSN seal—score higher on all transparency parameters, a pattern consistent with evidence that non-newsroom entities display more acts of disclosure than their newsroom-affiliated peers (Seet & Tandoc, 2024), which may reflect organizational inertia, different editorial priorities, or difficulties in integrating external standards into their workflows.

Furthermore, the results revealed problems in placing links to methodologies and corrections. Transparency depends not only on availability but also on usability and information architecture. Such detected deficiencies may be limiting the pedagogical potential in terms of media literacy of fact-checkers (Robinson et al., 2021) at a time of high informational fragility (van der Meer et al., 2023). Therefore, this perspective opens an essential line of improvement to increase the public impact of fact-checking (Graves & Anderson, 2020), through the articulation of new spaces for interaction between fact-checkers and the audience. The maximization of social media outreach (using agile and explanatory audiovisual formats) and the development of formulas based on conversational artificial intelligence are postulated as viable solutions.

The use of truthfulness scales is an old topic of debate within the field of fact-checking (Graves, 2016), with voices questioning their use and effectiveness. The reality is that they are commonly used by the majority of fact-checkers. Indeed, the variety of formats found—visual scales, colour scales, and textual scales—and the adoption of a single format by each fact-checker showed that, besides their content assessment function, the aim was for them to serve as a fact-checker brand identifier. In any case, European fact-checkers have not developed scales that possess the same powerful image as the Pinocchios or the Truth-O-Meter—recent studies suggest a decrease in the effectiveness of fact-checking when using these truthfulness scales (Walter et al., 2019). Still, one thing that did characterize the fact-checkers was the development of broad explanations, mainly in the form of text with some incorporated multimedia elements. Depth of content was a definitive characteristic of the media in the sample, which used a dual content strategy of fact-checks and contextual content, conveyed mainly through in-depth reports (Moreno-Gil et al., 2023).

Finally, the analysis clearly situates European fact-checkers within the second wave of fact-checking, with a greater focus on combating disinformation in the online environment (Cazzamatta, 2025a; Ferracioli et al., 2022; Riedlinger et al., 2024). The data showed that political fact-checking, as pioneered by the Americans, carried more weight for fact-checkers in the United Kingdom (Teschendorf, 2024)—especially in the BBC and Channel 4—and France—with Les Décodeurs standing out once again. In this sense, the specialization of the two Italian fact-checkers—Pagella Politica and Facta—based on the same founders is striking, with the work of the former focusing on political fact-checking and that of the latter on online disinformation. The Italian case shows a growing trend towards organizational specialization, a possible path to future professionalization in Europe. However, the digital environment, especially social media, was the main focus of attention for these media organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has acted as a real catalyst in changing the editorial priorities of fact-checkers, who now must face a more diffused adversary, marked by the viral logic of the algorithms of the major platforms and the transnational circulation of disinformation. Several key implications emerge from this reality: (a) the reinforcement of the role of fact-checkers in European information governance and in their growing collaboration with the institutions of the continent; (b) the need to advance in strengthening their technological capabilities to respond to an increasingly complex ecosystem (what role is AI playing in this matter?); and (c) an expansion of the democratic function of fact-checking itself, which is no longer limited to policing political discourse but also operates as a shield against a fragmented, polarized, and highly dynamic disinformation ecosystem.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/journalmedia6040201/s1, Analysis Sheet; Codebook.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and X.L.-G.; methodology, J.C. and A.S.-R.; software, J.C. and A.S.-R.; validation, X.L.-G., J.C. and A.S.-R.; formal analysis, X.L.-G., J.C. and A.S.-R.; investigation, X.L.-G., J.C. and A.S.-R.; resources, X.L.-G.; data curation, J.C. and A.S.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and X.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and X.L.-G.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, X.L.-G. and A.S.-R.; project administration, X.L.-G.; funding acquisition, X.L.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article/result/activity is part of the R&D project Artificial Intelligence in Digital Media in Spain: Effects and Roles (PID2024-156034OB-C22), funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF/EU”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be accessed at https://zenodo.org/records/17237855?token=eyJhbGciOiJIUzUxMiJ9.eyJpZCI6IjgzMWUzYmIzLTRmYmMtNGU1My1hNWM2LTIzY2UyNWI3MGRiMCIsImRhdGEiOnt9LCJyYW5kb20iOiIzNDVlZWE4ZTg4NDAxZTVlM2NmY2VlNDlhMjI4NjQ2MCJ9.rZQfOBjWpg16OURwRGfM_LTI4x4-k9cfy3qIzR83KpEN6uCTTQxEIS3LyBbzixvAB8rzwBT3gWO6GShn3uFSlw (accessed on 23 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abuín-Penas, J., Corbacho-Valencia, J. M., & Pérez-Seoane, J. (2023). Análisis de los contenidos verificados por los fact-checkers españoles en Instagram. Revista de Comunicación, 22(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Z., Osman, M., Bechlivanidis, C., & Meder, B. (2023). (Why) is misinformation a problem? Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 18(6), 1436–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2025). The incidence of COVID-19 disinformation among citizens in the U.S., India, Brazil, and Spain. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazeen, M. A. (2019). Practitioner perceptions: Critical junctures and the global emergence and challenges of fact-checking. International Communication Gazette, 81(6–8), 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Gromaz, L., & López García, X. (2016). Los medios incorporan renovados filtros para gestionar la calidad en las redes sociales. Revista Latina de Comunicación, 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, P., & Neidhardt, A.-H. (2021). From debunking to prebunking: How to get ahead of disinformation on migration in the EU. European Policy Center. Available online: https://www.epc.eu/content/PDF/2021/Disinformation___Migration_2021_final_single.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Calvo-Gutiérrez, E., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2023). Combatting fake news: A global priority post COVID-19. Societies, 13(7), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J. M., Guess, A. M., Loewen, P. J., Merkley, E., Nyhan, B., & Phillips, J. B. (2022). The ephemeral effects of fact-checks on COVID-19 misperceptions in the United States, Great Britain and Canada. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(2), 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. (2018). Research on political information and social media: Key points and challenges for the future. El Profesional de la Información, 27(5), 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. (2021). O Impacto da COVID-19 no Jornalismo: Um Conjunto de Transformações em Cinco Domínios. Comunicação e Sociedade, 40, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzamatta, R. (2025a). Decoding Correction Strategies: How Fact-Checkers Uncover Falsehoods Across Countries. Journalism Studie, accepted/forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzamatta, R. (2025b). The content homogenization of fact-checking through platform partnerships: A comparison between eight countries. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 102(1), 120–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J., & Lewandowsky, S. (2012). The debunking handbook (Version 2). University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Sánchez, C., Vizoso, Á., & López-García, X. (2023). Fake news in the post-COVID-19 era? The health disinformation agenda in Spain. Societies, 13(11), 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K., DeCook, J. R., & Kanthawala, S. (2022). Fact-Checking the Crisis: COVID-19, Infodemics, and the Platformization of Truth. Social Media + Society, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, S., Morani, M., Kyriakidou, M., & Soo, N. (2021). Why media systems matter: A fact-checking study of UK television news during the Coronavirus pandemic. Digital Journalism, 10(5), 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnic-Holan, A. (2024). The principles of the truth-o-meter: PolitiFact’s methodology for independent fact-checking. PolitiFact. Available online: https://www.politifact.com/article/2018/feb/12/principles-truth-o-meter-politifacts-methodology-i/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Ekström, M., Lewis, S. C., & Westlund, O. (2020). Epistemologies of digital journalism and the study of misinformation. New Media & Society, 22(2), 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Navarro, M.-Á., Nogales-Bocio, A.-I., García-Madurga, M.-Á., & Morte-Nadal, T. (2021). Spanish fact-checking services: An approach to their business models. Publications, 9(3), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN). (2024, February 19). Code of standards. Available online: https://efcsn.com/code-of-standards/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Fact-Checking—Duke Reporters’ Lab. (2014). Duke reporters’ lab. Available online: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Farkas, J. (2023). Fake news in metajournalistic discourse. Journalism Studies, 24(4), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracioli, P., Kniess, A. B., & Marques, F. P. J. (2022). The watchdog role of fact-checkers in different media systems. Digital Journalism, 10(5), 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, R., Ramírez-García, A., & Rodríguez-Rosell, M.-M. (2014). Media literacy education for a new prosumer citizenship. Comunicar, 22(43), 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., & Cheng, Z. (2021). Origin and evolution of the News Finds Me perception: Review of theory and effects. Profesional de la Información, 30(3), e300321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L. (2016). Deciding what’s true. The rise of political fact-checking in american journalism. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L. (2018). Boundaries Not Drawn: Mapping the institutional roots of the global fact-checking movement. Journalism Studies, 19(5), 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L. (2022). Fact-checking movement. In G. A. Borchard, C. H. Sterling, & Sage Publications (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of journalism (2nd ed., pp. 631–634). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L., & Anderson, C. W. (2020). Discipline and promote: Building infrastructure and managing algorithms in a “structured journalism” project by professional fact-checking groups. New Media & Society, 22(2), 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L., & Cherubini, F. (2016). The rise of fact-checking sites in Europe. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/rise-fact-checking-sites-europe (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Guallar, J., Codina, L., Freixa, P., & Pérez-Montoro, M. (2020). Desinformación, bulos, curación y verificación. Revisión de estudios en Iberoamérica 2017–2020. Telos, 22(3), 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanitzsch, T., & Vos, T. P. (2018). Journalism beyond democracy: A new look into journalistic roles in political and everyday life. Journalism, 19(2), 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humprecht, E. (2020). How do they debunk “fake news”? A cross-national comparison of transparency in fact checks. Digital Journalism, 8(3), 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivask, S. (2024). Teaching safety of journalists: Student responses and solutions to occupational risks and hostility. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 79(3), 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. K., & Wang, B. (2023). Diffusion of real versus misinformation during a crisis event: A big data-driven approach. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliska, M., & Roberts, J. (2024). Epistemology of fact checking: An examination of practices and beliefs of fact checkers around the world. Digital Journalism, 13(3), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2014). The elements of journalism, revised and updated 3rd edition: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. Three Rivers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. (2024). Fact-checking methodology and its transparency: What indian fact-checking websites have to say? Journalism Practice, 18(6), 1461–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, L., & Graves, L. (2024). How to grow a transnational field: A network analysis of the global fact-checking movement. New Media & Society, 27(6), 3505–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, L. G. (2021). Similar practice, different rationales political fact-checking around the world. Universität Duisburg-Essen. [Google Scholar]

- León, B., Martínez-Costa, M. P., Salaverría, R., & López-Goñi, I. (2022). Health and science-related disinformation on COVID-19: A content analysis of hoaxes identified by fact-checkers in Spain. PLoS ONE, 17(4), e0265995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Qi, L., Wang, L., & Metzger, M. J. (2023). Checking the fact-checkers: The role of source type, perceived credibility, and individual differences in fact-checking effectiveness. Communication Research, 52(6), 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Borrull, A., & Sanz-Martos, S. (2019). Desmontando fake news a través del conocimiento colaborativo. Anuario ThinkEPI, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marcos, C., & Vicente-Fernández, P. (2021). Fact checkers facing fake news and disinformation in the digital age: A comparative analysis between Spain and United Kingdom. Publications, 9(3), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Rosa, R. (2018). Nuevos formatos de verificación. El caso de Maldito Bulo en Twitter. Sphera Publica, 1(18), 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mahl, D., Zeng, J., Schäfer, M. S., Egert, F. A., & Oliveira, T. (2024). “We follow the disinformation”: Conceptualizing and analyzing fact-checking cultures across countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19401612241270004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzarlis, A. (2018). Fact-checking 101. In C. Ireton, & J. Posetti (Eds.), Journalism, “fake news” & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training (pp. 85–100). UNESCO. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1641987 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Martín García, A., & Buitrago, Á. (2022). Valoración profesional del sector periodístico sobre el efecto de la desinformación y las fake news en el ecosistema mediático. Revista ICONO14, 21(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Neira, J.-I., Trillo-Domínguez, M., & Olvera-Lobo, M.-D. (2023). Ibero-American journalism in the face of scientific disinformation: Fact-checkers’ initiatives on the social network Instagram. El Profesional de La Información. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, P., Ruiz-Caballero, C., & Suau, J. (2019). Active audiences and social discussion on the digital public sphere. Review article. El Profesional de La Información, 28(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon-Vegas, X., & Mauri-Ríos, M. (2022). Bringing journalism back to its roots: Examining fact-checking practices, methods, and challenges in the Mediterranean context. El Profesional de La Información. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon-Vegas, X., Rodríguez-Martínez, R., & Mauri-Ríos, M. (2023). Explanatory journalism within European fact checking platforms: An ally against disinformation in the post-COVID-19 era. Societies, 13(11), 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. (2000). Designing web usability: The practice of simplicity. New Riders Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pavleska, T., Školkay, A., Zankova, B., Ribeiro, N., & Bechmann, A. (2018). Performance analysis of fact-checking organizations and initiatives in Europe: A critical overview of online platforms fighting fake news. Available online: https://goo.gl/7jkJQ1 (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Redondo Escudero, M. (2018). Verificación digital para periodistas: Manual contra bulos y desinformación internacional. Editorial UOC. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, K., Walsh-Childers, K., Fischer, K., & Davie, B. (2020). Restoring trust in journalism: An education prescription. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 75(1), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlinger, M., Montaña-Niño, S., Watt, N., García-Perdomo, V., & Joubert, M. (2024). Fact-Checking Role Performances and Problematic COVID-19 Vaccine Content in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Media and Communication, 12, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S., Jensen, K., & Dávalos, C. (2021). “Listening literacies” as keys to rebuilding trust in journalism: A typology for a changing news audience. Journalism Studies, 22(9), 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, R. (2019). Digital journalism: 25 years of research. Review article. El Profesional de La Información, 28(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, S., & Tandoc, E. C. (2024). Show me the facts: Newsroom-affiliated and independent fact-checkers’ transparency acts. Digital Journalism, 12(10), 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. M., & Camargo, C. Q. (2021). Autopsy of a metaphor: The origins, use and blind spots of the ‘infodemic’. New Media & Society, 25(8), 2219–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. B. (2018). Fact-Checkers as Entrepreneurs: Scalability and sustainability for a new form of watchdog journalism. Journalism Practice, 12(8), 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixto-García, J., & López-García, X. (2023). Innovative innovation in journalism. Journalism, 26(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, K., Nykänen, N., Seeck, H., Kim, Y., & McPherson, E. (2025). Fact-Checking in Journalism: An Epistemological Framework. Journalism Studies, 26(10), 1129–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, S., Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., & Gracia-Villar, M. (2024). Unveiling the truth: A systematic review of fact-checking and fake news research in social sciences. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 14(2), e202427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorf, V. S. (2024). Understanding COVID-19 Media Framing: Comparative Insights from Germany, the US, and the UK During Omicron. Journalism Practice, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, T. G. L. A., Hameleers, M., & Ohme, J. (2023). Can fighting misinformation have a negative spillover effect? How warnings for the threat of misinformation can decrease general news credibility. Journalism Studies, 24(6), 803–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The platform society. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vaudano, M., Sénécat, A., & Maad, A. (2021). Les idées claires sur le COVID-19: L’origine du virus. Le Monde. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/03/20/les-idees-claires-sur-le-covid-19-l-origine-du-virus_6073883_4355770.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Viciosa, M. (2021). Variante británica: Más contagiosa, no más grave e igual ante las vacunas. Newtral. Available online: https://www.newtral.es/variante-britanica-no-grave-vacunas/20210416/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Vizoso, Á., & Vázquez-Herrero, J. (2019). Fact-checking platforms in Spanish. Features, organisation and method. Communication & Society, 32(1), 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N., Cohen, J., Holbert, R. L., & Morag, Y. (2019). Fact-checking: A meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Political Communication, 37(3), 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information Disorder. Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking. Council of Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. (2018). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ye, Q. (2023). Comparison of the transparency of fact-checking: A global perspective. Journalism Practice, 17(10), 2263–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).