Abstract

This study examines the role of creative resistance, or “artivism”, in Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement, a youth-led campaign against police brutality that peaked in October 2020. Drawing on Robert Entman’s Framing Theory, it analyzes how different art forms reframed public perceptions of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) and countered government efforts to delegitimize the protests. Using a qualitative approach, the research employs purposive sampling of Twitter-sourced art forms to explore how these pieces exposed systemic injustice, amplified protester voices, and mobilized local and global support. Findings reveal that artivists personalized SARS brutality, dismantled narratives portraying protesters as criminals, and invoked moral urgency through evocative symbolism, leveraging social media’s virality to sustain the movement’s momentum. The study highlights SARS’ paradoxical role as a state-sanctioned yet reviled entity, demonstrating how creative expressions clarified this ambiguity into a clarion call for reform. By situating #EndSARS within Nigeria’s protest legacy, this analysis underscores art’s transformative power in digital-age activism, offering a blueprint for resistance against oppression. It contributes to scholarship on social movements by illustrating how art and technology intersect to challenge power, preserve collective memory, and demand accountability, with implications for future struggles in Nigeria and beyond.

1. Introduction

Nigeria’s sociopolitical landscape has long been shaped by a robust tradition of protests and grassroots resistance, reflecting the resilience and determination of its people in confronting oppression and demanding justice. This legacy traced back to the colonial era with revolutionary events such as the Aba Women’s Riot of 1929, where women challenged unfair colonial tax policies, and the Abeokuta Women’s Revolt of 1947 led by Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, which resisted an exploitative taxation system (; ). Other notable uprisings within the period include the Lagos Market Women’s Protests of 1932 and 1940 under Alimotu Pelewura and the 1945 Nigerian General Strike by railway workers, which all signaled widespread discontent with colonial rule (; ). The 1949 Enugu Colliery Massacre (Iva Valley Shooting), where striking coal miners were killed by colonial forces, further incited resistance against systemic exploitation ().

This spirit of defiance persisted into the post-independence period. The 1978 “Ali Must Go” student protests against educational fee hikes, the 1989 Anti-SAP (Structural Adjustment Program) riots opposing economic austerity, and the 1993 June 12 protests challenging electoral annulment marked critical junctures in Nigeria’s democratic struggle (; ). More recently, movements like the 2012 Occupy Nigeria protests against fuel subsidy removal, the 2014 Bring Back Our Girls campaign for abducted Chibok schoolgirls (; ), and the 2024 End Bad Governance demonstrations against unfavourable economic policies have reaffirmed Nigerians’ enduring commitment to accountability and reform.

Within this continuum, the 2020 Sòrò-Sókè movement, translated from Yoruba as “Speak Up” or “Speak Louder”, emerges as a revolutionary chapter in Nigeria’s protest history. The movement, which was sparked by outrage over the Nigerian Police Force’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a unit notorious for brutality, extrajudicial killings, corruption, and arbitrary detentions, take on long-standing grievances against systemic injustice.

Initially ignited on Twitter (now X) in 2017, #EndSARS gained unprecedented momentum in October 2020, fueled by viral hashtags and distressing personal accounts of police violence. Early government attempts to dismiss it as a “Yahoo Boys” movement—a label for internet fraudsters—failed as it evolved into a broader youth-led demand for justice, police reform, and governance accountability. Notably, during the first month of the COVID-19 lockdown, police killings (18) outpaced virus-related deaths (12), intensifying public outcry ().

What distinguishes #EndSARS from prior movements is its seamless integration of physical protests with digital activism and creative resistance, or “artivism”. Nigerian youths harnessed visual art, music, skit, poetry, performances, and digital media not merely as expressive outlets but as potent tools for mobilization and solidarity. This creative ingenuity redefined Nigeria’s protest culture, blending traditional dissent with contemporary forms of expression and leveraging social media, particularly Twitter, to organize, inform, and counter state narratives (). Hashtags, viral videos, and real-time updates amplified testimonies of police brutality, dismantled the ambiguous perception of SARS as both a feared oppressor and a supposed crime-fighting necessity, and garnered global attention.

This study situates #EndSARS within Nigeria’s rich history of resistance, focusing on how creative resistance shaped its framing and sustained its momentum. Through a framing analysis grounded in Entman’s Framing Theory, it explores the interplay of artivism and activism, examining how these elements amplified marginalized voices, challenged oppressive systems, and redefined public discourse. Specifically, this research addresses the following questions: (1) How did artistic expressions during #EndSARS utilize Framing Theory to reframe public perceptions of police brutality and counter government narratives delegitimizing the protests? (2) In what ways did #EndSARS art forms amplify marginalized voices, expose systemic injustices, and mobilize local and global support for justice and reform? (3) How did the interplay of digital media and creative resistance shape the narrative and momentum of #EndSARS within Nigeria’s broader protest legacy? By exploring these questions, this study contributes to scholarship on the transformative role of art in social movements, positioning #EndSARS as both an extension of Nigeria’s protest legacy and a model for future resistance.

In a nation where youth face systemic disadvantages, the movement’s use of creative expression to narrate struggles and counter official misinformation highlights art’s power as a catalyst for social change. Following this introduction, the paper examines the historical and contextual background of #EndSARS, outlines its objectives, and discusses the theoretical and methodological approaches that underpin the study. It then analyzes three selected art forms to illustrate their role in reframing narratives and mobilizing support. The findings of the analysis are critically discussed before concluding with reflections on artivism’s legacy in the Sòrò-Sókè movement and its implications for future resistance.

2. Brief Background to the Study

The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was established in Lagos in 1992 as a tactical unit to address Nigeria’s rising insecurity like armed robbery, kidnappings, and contract killings, all of which emerged from the country’s turbulent political landscape, marked by prolonged military rule. In response, SARS was conceived as an elite force tasked with handling these violent crimes, conducting covert operations, and dismantling criminal networks. To enhance operational efficiency, SARS officers were granted autonomy, operating without uniforms or marked vehicles to maintain an element of surprise (). However, lack of oversight and accountability soon led to widespread abuses, and over time, SARS became notorious for extortion, torture, extrajudicial killings, and arbitrary arrests, particularly targeting young Nigerians perceived as affluent based on their appearance or possessions. Despite repeated calls for reform, the unit continued to operate with impunity, becoming a symbol of state-sanctioned violence and oppression.

The pervasive injustices inflicted by SARS after its expansion across the country in 2002 inevitably sparked resistance, which led to a social media campaign in 2017 under the hashtag #EndSARS, driven by activists such as Segun Awosanya (Segalink), Damilare Olabode (Letter_to_Jack), Michael Ugochukwu Stephens (Ruggedman), Abdul Mahmud (Great Oracle), Harrison Gwamnishu, and Oluyemi Fasipe (Yemie Fash) and organizations like Citizen Gavel (Tech4justice), among others. Through this platform, thousands of Nigerians shared personal testimonies of SARS brutality, which intensified demands for the unit’s abolition.

The movement gained momentum as it highlighted systemic issues within the Nigerian Police Force, including extrajudicial killings, torture, arbitrary detention, and deep-rooted corruption. A turning point came on 3 October 2020, when a video alleged that SARS operatives had killed 22-year-old Joshua Ambrose in Ughelli, Delta State (). This incident, coupled with the killing of Jimoh Isiaq by police on 10 October 2020, in Ogbomosho, Oyo State, escalated public outrage and triggered nationwide protests ().

The #EndSARS protests, which began on 7 October 2020, were initially peaceful but were later marred by violence. On 20 October 2020, the movement reached a tragic climax when unarmed protesters were massacred at the Lekki Toll Plaza in Lagos, allegedly by security forces and criminal elements hired by government officials (). Despite this repression, the movement unified Nigerians in a historic demand for justice, accountability, and an end to police brutality.

Twitter, in particular, played a pivotal role, serving as a dynamic tool for coordination, real-time documentation of abuses, and global outreach, thereby sustaining the movement’s momentum (). Meanwhile, artists across disciplines crafted contents that amplified protester voices, reframed narratives, and galvanized international solidarity. This synergy distinguished #EndSARS from prior Nigerian movements, empowering grassroots activists to shape discourse independently of traditional power structures ().

Though the movement was violently suppressed, its legacy endures as a catalyst for a new generation of activists, demonstrating the transformative potential of digital media and art in confronting entrenched institutions. The movement’s significance extends beyond its immediate outcomes by offering a model of resistance in the digital age.

3. Objective of the Study

This study aims to conduct a critical analysis of art forms that emerged from Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement, examining their role as instruments of creative resistance and narrative reframing. Specifically, it investigates how these artistic expressions countered government efforts to delegitimize the protests—often by portraying them as criminal or frivolous—while foregrounding systemic injustices, particularly police brutality. By unpacking the layered meanings embedded in these works, the research illustrates how art served not only as a medium of dissent but also as a powerful catalyst for shaping public discourse around policing in Nigeria.

A key focus is the paradoxical role of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a state-sanctioned unit established to combat violent crime yet widely reviled as a perpetrator of terror and oppression against citizens. Despite long-standing public distrust, SARS’ abuses gained critical visibility through the #EndSARS movement, amplified significantly by artistic and visual protest forms. This study evaluates how these art forms dismantled government narratives, exposed the unit’s brutality, and galvanized collective demands for justice and systemic reform. By so doing, it highlights the transformative capacity of art to unify voices, challenge power, and reframe perceptions of a deeply contested institution, contributing to broader understandings of creative resistance in social movements.

4. Framing Theory

Robert Entman’s Framing Theory provides a robust lens for analyzing how information is selectively presented to shape perceptions of reality. Entman posits that frames are cognitive schemata that organize experience by highlighting certain aspects of an issue while downplaying others, thereby influencing attitudes, beliefs, and actions (). According to him, framing operates through four key functions: “define problem” (Problem Identification of the issue and why it matters), “diagnose causes” (Causal Interpretation refers to explaining what or who is responsible for the issue), “make moral judgments” (Moral Evaluation, that is, assigning ethical judgements to the situation or involved parties), and “suggest remedies” (Treatment Recommendation involves suggesting solutions or actions to address the issue) (). These functions guide how individuals interpret complex phenomena and make decisions, making the theory particularly suited to dissecting the role of art in social movements.

In the context of Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement, Framing Theory reveals how artistic expressions served as tools to reframe public narratives around police brutality, counter government disinformation, and mobilize collective action. This study applies Entman’s framework to analyze sampled art forms, demonstrating how they strategically communicated the movement’s demands and reshaped discourse about the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). Below, each framing function is explored with specific examples from the #EndSARS artivism.

4.1. Problem Identification: Exposing Police Brutality and Systemic Injustice

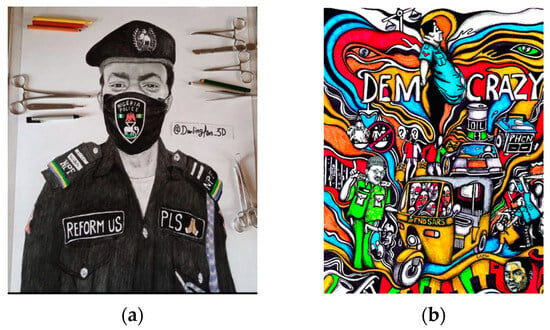

The #EndSARS movement used various art forms to consistently frame police brutality as a critical and pervasive issue in the Nigerian society. Paintings, posters, murals, songs, and performances employed visuals elements like bloodied fists, broken chains, and victim silhouettes to spotlight SARS’ oppressive actions (see Figure 1). Through this framing function, artivists served two purposes with their works; the first is they raise awareness by visually representing the brutality and injustice, and by that, they helped bring attention to issues that were often ignored or normalized. And secondly, it humanizes victims by constantly presenting portraits of individuals who suffered at the hands of SARS, thereby creating emotional connections that encouraged the populace to empathize with the victims.

Figure 1.

Samples of #EndSARS artworks framing police brutality as systemic injustice. (a) For Tina, Artist: Jemila Arayela; (b) Untitled, Artist: Elaebi Amaremo (Eli the Great).

4.2. Causal Interpretation: Identifying Systemic Roots

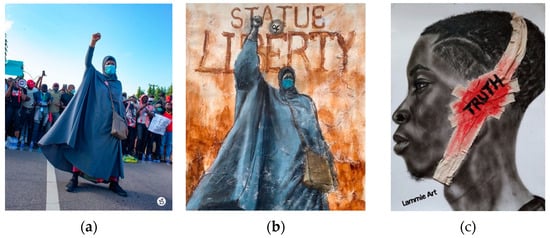

Through the lens of Framing, artists like Darlington Okoduwa and Laolu Senbanjo framed the issue of SARS as a symptom of deeper systemic corruption within Nigeria’s government and police force. Okoduwa’s 3D piece, with its phrase “Serve the people, not the government”, and Senbanjo’s depictions of entrenched corruption, presented the problem as an institutional issue rather than an isolated incident (see Figure 2). By exposing SARS as a threat to citizens rather than a crime-fighting necessity, these works challenged public indecision—as some feared a society without SARS—while urging critical scrutiny of state power and demands for accountability.

Figure 2.

Samples of #EndSARS artworks exposing systemic corruption as the root of SARS’s brutality. (a) Brain Surgery, Artist: Darlington Okoduwa (Darlinton 3D); (b) DEMOCRAZY, Artist: Laolu Senbanjo.

4.3. Moral Evaluation: Advocating Justice and Human Rights

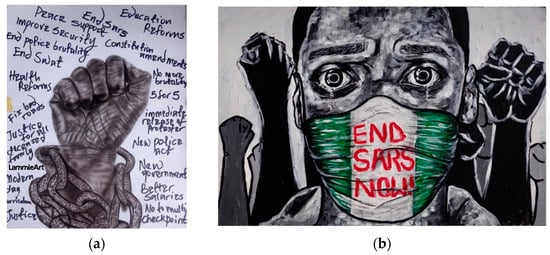

The moral dimension of #EndSARS artivism emerged through cultural and religious motifs that highlighted ethical violations. The viral photograph of Aisha Yesufu, dubbed Nigeria’s “Statue of Liberty” (captured by Victor Odiba), alongside works like Bakare Omodara’s call to “face the truth”, invoked shared values of fairness and community (see Figure 3). This framing transcended ethnic and class divides, uniting Nigerians in a collective stance against oppression and reinforcing SARS’ illegitimate actions as a moral outrage.

Figure 3.

Samples of #EndSARS artworks advocating justice and human rights through moral outrage. (a) Protest Image of Aisha Yesufu, Artist: Victor Odiba; (b) Statue of Liberty, Artist: Tunde Lasisi; (c) Untitled, Artist: Bakare Omodara.

4.4. Treatment Recommendation: Mobilizing for Change

Beyond critique, these art forms offered actionable solutions, embedding phrases like “End SARS Now”, “Reform the Police”, and “Justice for All” in pieces by Sabina Silver, Bakare Omodara, and many more (see Figure 4). These calls transformed passive discontent into active participation, encouraging protests, petitions, and social media amplification. By presenting tangible steps, the art fueled the movement’s momentum, empowering individuals to envision and pursue systemic reform.

Figure 4.

Samples of #EndSARS artworks mobilizing for systemic reform. (a) ENDSARS, Artist: Bakare Omodara; (b) We No Go Gree, Artist: Sabina Silver.

In contrast, government and pro-establishment narratives framed #EndSARS as a national security threat, alleging foreign interference and portraying activists as unpatriotic to justify repression. Artivists countered this delegitimization by leveraging Entman’s framing functions to expose brutality, attribute systemic causes, invoke moral urgency, and propose solutions. This strategic use of art not only mobilized local and global solidarity but also positioned #EndSARS within Nigeria’s broader struggle for democratic accountability.

Framing Theory thus reveals the pivotal role of #EndSARS artivism in communicating complex issues accessibly and impactfully. By redefining SARS from a necessary evil to a symbol of injustice, these art forms amplified calls for change, offering a blueprint for how creative expression can drive social movements in the digital age.

5. Methods

This study employs a qualitative approach to analyze artistic expressions from Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement, with data primarily sourced from Twitter (now X), as it was a key platform for the movement’s digital ar(c)tivism. A purposive sampling method was utilized to select data, guided by criteria aligned with the study’s objectives of examining art’s role in framing resistance and countering false narratives. To ensure methodological rigor, the search process, time frame, and selection criteria are detailed below, followed by the analytical approach.

The search for various art forms was conducted on Twitter using a combination of hashtags and keywords central to the #EndSARS movement. Primary search terms included #EndSARS, #EndPoliceBrutality, #LekkiMassacre, #EndInjustice, and #SoroSoke, which were prevalent during the protests and associated with digitally shared contents. Additional keywords such as “art”, “painting”, “skit”, “illustration”, “drawing”, and “photograph” were used to filter for creative expressions. The search time frame spanned 3 October to 31 October 2020, covering the peak of the #EndSARS protests, including key events like the protest art event on 17 October and the Lekki Toll Gate massacre on 20 October 2020. This period was chosen to capture the diverse art forms created and shared during the movement’s peak, ensuring relevance to the study’s focus on real-time digital artivism.

From this search, approximately 60 diverse art forms were retrieved, encompassing a range of forms such as paintings, photographs, skits, posters, music, illustrations, and performances shared via tweets, retweets, or replies. The pool included viral images, protest art paintings, and activist-driven content, identified through Twitter’s search functionality and engagement metrics (e.g., retweets, likes, quotes, and mentions). To narrow the selection, retrieved data were evaluated based on their prominence, measured by social media engagement (e.g., retweets exceeding 1000 or likes exceeding 2000) and their ability to advance the #EndSARS campaign’s themes—challenging false narratives, exposing systemic injustices, mobilizing support, amplifying protester voices, and highlighting hidden abuses. From this process, three significant art forms were selected for in-depth content analysis: Debo Adebayo’s skit “End SARS Now! E Fit Be You Next”, Chigozie Obi’s painting Ezu River, and the uncredited photograph The Blood-Stained Flag. These were chosen for their high engagement, diverse artistic forms (performance, visual art, and photography), and alignment with Framing Theory’s functions, as detailed in Section 4.

The content analysis involved a close reading of each sample’s visual and textual elements, such as symbolism, color, composition, and accompanying captions or hashtags, to uncover how they construct meaning within the #EndSARS context. Guided by Entman’s Framing Theory (), the analysis applied the four functions—problem identification, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and treatment recommendation—to dissect how these artworks shaped perceptions of police brutality and mobilized support. The selected art forms were examined to assess their role in achieving the study’s objectives:

- Challenging False Narratives: Countering government portrayals of victims and protesters as criminals or threats, thereby reframing their identities and struggles.

- Exposing Systemic Injustices: Revealing deep-rooted abuses perpetrated by the Nigerian Police Force, particularly the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), as institutional rather than isolated acts.

- Mobilizing Public Support: Galvanizing local and global participation in the movement through emotional resonance and calls to action.

- Amplifying Protester Voices: Elevating marginalized perspectives to center the experiences of those affected by SARS brutality.

- Highlighting Hidden Injustices: Bringing to light abuses that might otherwise have been obscured or ignored, ensuring visibility for systemic issues.

This method allowed for a deep exploration of how artivism intersected with digital platforms to drive the movement’s narrative and influence collective action. By focusing on these purposively selected samples with significant Twitter engagement, the study provides a focused yet rich understanding of creative resistance during the Sòrò-Sókè protests.

6. Analysis of Selected Samples

6.1. “End SARS Now! E Fit Be You Next” by Debo Adebayo (Mr. Macaroni)

Debo Adebayo, widely known as Mr. Macaroni, is a Nigerian comedian and actor who emerged as a key artivist during the #EndSARS movement. Leveraging his substantial social media platform, he transitioned from just a pure entertainer to social commentator, using satire to spotlight police brutality and systemic injustice. His skit “End SARS Now! E Fit Be You Next”, a 2-min-25-s dramatic piece shared on various social platforms, including Twitter on 11 October 2020, exemplifies this shift. Despite his arrest after the major protests, Adebayo persisted in advocating for police reform, making this work a resonant contribution to Sòrò-Sókè’s agenda. This satirical skit was selected for its performative power in humanizing SARS’ victims and critiquing societal complicity, as well as its social media engagement, evidenced by its widespread reach on Twitter with over 112,000 retweets, 133,000 likes, and over 674,000 views, reflecting its role in mobilizing online and offline protesters.

The skit features Mr. Macaroni as the “Daddy”, a dismissive father representing older-generation skepticism toward the #EndSARS protests, alongside his daughter Motunde, who seeks to join the movement, and his son Richard, who becomes a victim of SARS brutality (see Figure 5). The narrative unfolds as Mr. Macaroni mocks the protesters, labeling them “criminally minded” youths flaunting wealth without “9–5” jobs, while casually greeting SARS officers who reinforce his views. The tone shifts dramatically when the officers reveal a slain “criminal” in their truck, identified by Motunde as her brother, Richard. A flashback revealed Richard’s fatal encounter with SARS, triggered by his “shiny jewelry”, exposing the arbitrary violence Daddy had denied. Stricken, Daddy confronts the officers, holding his son’s body in a wrenching reversal of his earlier stance (see Appendix A for the full transcript).

Figure 5.

Still from End SARS Now! E Fit Be You Next by Debo Adebayo, showing Daddy’s grief over Richard’s SARS-inflicted death. Source: Artist’s Twitter page.

Applying Entman’s Framing Theory in dissecting how the skit reframes police brutality, we analyzed the four framing functions as follows: Problem Identification—the skit vividly defines police brutality as an urgent crisis, using Richard’s death to personalize SARS’ violence. The flashback, which showed officers harassing and shooting Richard for his appearance, mirrors countless real-life testimonies shared during #EndSARS, making the issue tangible and relatable. The title, “E Fit Be You Next”, stresses the universal threat, challenging apathy among viewers. Causal Interpretation—SARS is framed as the root cause, not merely as rogue actors but as a symptom of systemic failure. Daddy’s initial defense of the officers, reinforcing government narratives that SARS protects society, crumbles when his son becomes a victim, implicating state-sanctioned impunity. The skit critiques societal complicity, as Daddy’s elitism blinds him until the tragedy strikes him. Moral Evaluation—the piece invokes a moral awakening, shifting from Daddy’s callous endorsement of SARS to anguished outrage. Cultural motifs, like the familial bond between Daddy and Richard, appeal to shared values of justice and protection, uniting viewers across generations. This ethical reframing delegitimizes SARS’ actions, exposing their brutality as a violation of human rights. Treatment Recommendation—the skit implicitly calls for action through various hashtags—#EndSARS, #EndPoliceBrutality, and #ReformPoliceNG—urging viewers to reject passivity and demand reform. Daddy’s transformation from skeptic to mourner models a shift from indifference to activism, encouraging collective resistance.

The skit counters government narratives that branded protesters as criminals or foreign agitators, a stance Daddy initially parrots. By revealing Richard—a presumed “criminal”—as an innocent son, it dismantles these falsehoods, humanizing victims and aligning with the study’s aim to challenge delegitimizing rhetoric. Its satirical tone, paired with a tragic climax, amplifies protester voices, mobilizes support, and exposes hidden injustices, resonating widely due to Adebayo’s over 1.5 million followers at the time.

“E Fit Be You Next” exemplifies artivism’s power within #EndSARS, blending humor and drama to reframe police brutality as a systemic, personal, and moral crisis. Its viral impact, evidenced by the post interactions, underscored its role in raising awareness and inspiring action, cementing Adebayo’s skit as a cornerstone of the movement’s creative resistance.

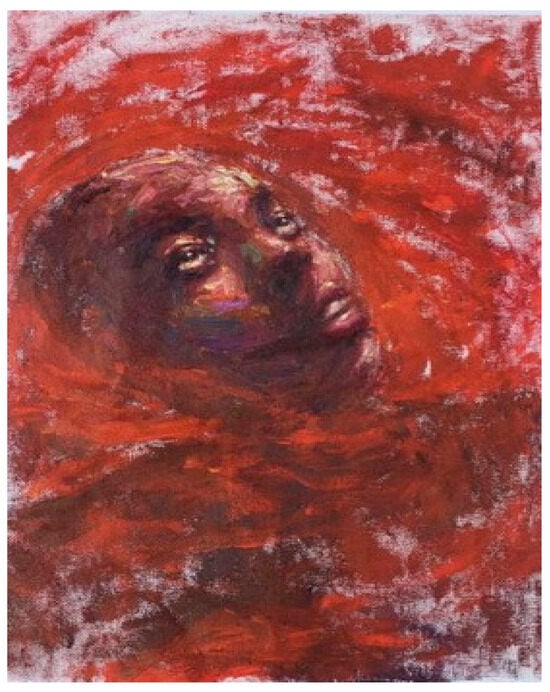

6.2. Ezu River by Chigozie Obi

Chigozie Obi, a Nigerian visual artist, contributed to the #EndSARS movement through her involvement in the Protest Art Live Painting event at Lekki Toll Gate on 17 October 2020. Organized by the art community led by herself, Ayo Sanusi, and Kehinde BB, other artists who participated in the session include Tunde Lasisi, Donna Duke, Jemima Arayela, Oluwaseun Akinlo, Julius Agbaje, Sotonye Jumbo, Ken Nwadiogbu, and others. This initiative invited artists to create works on-site to raise awareness and funds for the cause. Obi’s oil-on-canvas painting Ezu River was one of the event’s emotive pieces as it depicts a young boy floating lifelessly in a blood-red river, his pale form and unblinking eyes stark against the gory expanse (see Figure 6). The proceeds from the sale of the artwork, along with those from other works created during the live session, supported legal aid for protesters and SHquseNG, an organization that aids queer activists (). This highlights art’s dual role as both expression and action.

Figure 6.

Ezu River by Chigozie Obi, painted during #EndSARS protests, depicting a boy’s death in a blood-red river. Source: Artist’s Twitter page.

Art X Lagos, a prominent international art fair in West Africa, shared the artwork, along with three others created at the event, on their official social handles. This was part of their discussions and virtual showcase after the 2020 fifth edition of the fair was recalibrated to highlight the protests. The exhibition featured a visual archive of over 100 artists, filmmakers, and photographers who were at the forefront of documenting the #EndSARS protests. The piece garnered over 2000 retweets and 3000 likes across platforms, indicating significant online visibility.

The painting was inspired by the Awkuzu atrocities in Anambra State, where SARS operatives were allegedly accused of dumping victims’ bodies into the Ezu River. It depicts the 2013 discovery of approximately 35 corpses that were linked to officer James Nwafor and his men (). Obi personalizes this horror through the story of Chijioke Iloanya, a 20-year-old arrested by SARS, whose father endured extortion and waded through corpses in a futile search for his son’s body. The boy’s serene yet haunting posture, submerged in a calm, blood-filled river, juxtaposes innocence with the brutality that claimed his life, documenting the systemic violence of SARS.

Ezu River reframes narratives by shedding light on the injustice of SARS brutality. The Entman’s framing functions manifest in the following manners: Problem Identification—the blood-filled river defines police brutality as a pervasive crisis, with the boy symbolizing victims like Chijioke Iloanya. The overwhelming red, dominating the canvas, mirrors the scale of bloodshed, while the title Ezu River ties it to a documented atrocity. Created amid the Lekki protests, the painting inherently demands attention to abuses often obscured by official silence. Causal Interpretation—Obi implicates SARS, systemic corruption, and government impunity as the root causes, the river serving as a metaphor for state-sanctioned violence. The calm surface belies the chaotic brutality preceding the boy’s death, critiquing the chilling detachment of these acts, recalling the father’s harrowing search to highlight systemic failure. This framing dismantles narratives justifying SARS as a crime-fighting necessity, rather exposing it instead as a perpetrator of terror against the youth it was meant to protect. Moral Evaluation—the boy’s ghostly pallor and unblinking eyes invoke a moral outrage, reflecting the innocence lost to senseless violence. Anchored in the Ezu River, a site of mass murder and national memory, the painting appeals to shared values of justice and humanity, uniting audiences across divides. Its motionlessness intensifies the ethical violation, framing SARS’ actions as utterly unconscionable. Treatment Recommendation—as a live protest artwork, Ezu River implicitly calls for justice and reform. Its creation at Lekki Toll Gate embed in it a demand for action. Its fundraising role further transforms grief into tangible support for resistance, fueling and sustaining the movement’s momentum. The visual impact—red as a cry for attention, sacrifice, and anger—compels reflection and urges viewers to act.

Obi counters government narratives dismissing #EndSARS as unpatriotic by rooting her work in the undeniable Ezu River tragedy and Chijioke’s story, humanizing victims falsely labeled criminals. The painting amplifies silenced voices, notably the father’s anguish, and unearths hidden injustices, resonating with Siyanbola et al. view of art as a spotlight for societal issues (). Its protest context and emotional weight incited outrage, fueling the Sòrò-Sókè call for accountability.

Ezu River emerges as a powerful artifact of #EndSARS artivism, merging memorialization with resistance. It immortalizes victims’ suffering, critiques systemic oppression, and sustains the movement’s momentum through its practical contributions. Obi’s work exemplifies art’s transformative role, reframing SARS brutality as a personal and collective crisis demanding justice.

6.3. The Blood-Stained Flag (Uncredited)

The Blood-Stained Flag, an uncredited viral image from the Lekki Toll Gate massacre on 20 October 2020, is a striking and enduring visual symbol of the #EndSARS movement. The image, which was captured by an anonymous protester at nighttime, shows a Nigerian flag with its green and white stripes smeared with vivid red blood, held up closely by another protester, their face partially visible against the dark backdrop (see Figure 7). The image, which was widely circulated on Twitter that night, captured the violence unleashed on peaceful demonstrators. This turned a national emblem of unity and peace into a glaring testament to state betrayal. While the exact metrics are scarce because the image cannot be attributed to any original author, it has been shared and retweeted countless times, garnering millions of engagements. Rihanna’s post of the image alone garnered over 550,000 engagements and millions of impressions on Twitter, while her Instagram post received over 1.3 million engagements.

Figure 7.

Blood-Stained Flag (uncredited), capturing a blood-smeared Nigerian flag from the Lekki massacre. Source: Twitter.

The background context intensifies the weight of this visual. After days of #EndSARS protests, Lagos State Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu declared a 24 h curfew on 20 October 2020, announced at 1:00 p.m. and initially set to begin at 4:00 p.m., but later postponed to 9:00 p.m. Despite this curfew, peaceful protesters at Lekki Toll Gate chose to stay, exercising their constitutional right to peaceful assembly and protest. However, around 7:00 p.m., the Nigerian Armed Forces accompanied by the Nigerian police officers arrived at the protest ground. The protesters, on the other hand, believing that if they sang the national anthem and waved their flags, they would be safe. In doing so, the demonstrators knelt and sang in defiance. Yet, the officers opened fire on the protesters, staining the flag with blood. A popular Nigerian disc jockey, DJ Switch, who was at the venue, livestreamed the event on her Instagram page. The livestream captured this horror, which provided crucial evidence of the attack and was vital in countering government denials of the massacre. In parts of her stream, protesters were seen trying to remove a bullet from a man’s leg and using the flag to stem the bleeding leg ().

In the aftermath, with all the overwhelming evidence all over the media, the government attempted to deny the events. Government spokespersons claimed that security forces did not kill protesters, stating that they only used blank bullets in an attempt to disperse them. Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu was also at the center of this misinformation, as he initially denied that no one was killed at Lekki, but later tweeted the same day that only one person died in the hospital from blunt force trauma and that the connection to the shooting was still under investigation (). The Nigerian military also, as usual, denied responsibility, labeling various media reports as “fake news”.

The precise number of casualties from the Lekki Toll Gate massacre remains uncertain due to conflicting reports and government denials. Amnesty International documented 38 deaths, SBM Intelligence estimated 46, and the 2021 Lagos Judicial Panel officially confirmed 9 fatalities. Additionally, a leaked memo in 2023 revealed the Lagos State Government’s plans for the mass burial of 103 victims, suggesting a higher death toll (; ; ; ).

We apply Framing Theory to examine how the image counters narratives and denials of a tragic event that would otherwise have been swept under. The framing functions are as follows: Problem Identification—the bloodied flag defines state-sponsored violence as a crisis, its red stains on the white stripe, which should ideally symbolize peace, essentially conveying the massacre’s toll. The image, tied to Lekki’s documented brutality, immerses viewers in the loss of lives, further intensified by DJ Switch’s footage of a flag being used as a makeshift bandage. It demands recognition of a tragedy the state sought to erase. Causal Interpretation—The blood suggests involvement of security forces and government complicity, as the flag, intended to be revered by the state, is defiled, exposing a systemic failure. The government’s initial denials were shattered by the Judicial Panel’s ruling, which found Nigerian military culpable in the massacre and the 2023 leaked memo (; ). This framing exposes a state that assaults its citizens, contradicting its protective mandate. Moral Evaluation—the image invokes moral outrage by subverting the flag’s ideals of justice, peace, and unity. The blood evokes martyrdom, resonating with Adeniyi’s lament that “to be shot … while protesting is a stain on the conscience of any nation” (2020). Set against Nigeria’s history of state violence, such as the 2015 Zaria massacre and the 2018 attack on Shiite Muslims, the image unites viewers in condemning this ethical breach (, ). Treatment Recommendation—as a viral state violence symbol, the flag demands accountability and reform. The image gained global attention after foremost celebrities like Rihanna, Anthony Joshua, Beyoncé, Burna Boy, Nicki Minaj, Viola Davies, Kanye West, Odion Ighalo, and many others retweeted and reacted to it on their social media platforms (; ). Its impact was further amplified through creative recreations, such as Victoria Chiamaka’s incorporation of the bloodied flag imagery into her outfit at the 2021 Miss Africa in Russia and Bovi Ugboma’s symbolic reference to it during his 2021 Headies award ceremony performance in Nigeria (; ). These actions transformed the image into a global call for justice, intensified pressure on the government, and further fueled solidarity protests worldwide.

The image directly contradicts the government’s narratives denying the massacre. Its bloodied flag, used in both defiance and desperation, refutes claims of “blank bullets”. It amplifies silenced voices, from livestreamed victims to the 103 individuals buried, and exposes injustices concealed by official falsification. Drawing parallels with global protest imagery, such as Hong Kong’s bloodied and defaced flags during the 2019–2020 protests against mainland China, #EndSARS positions itself as a universal struggle against oppression.

The Blood-Stained Flag completely refutes government narratives that portrayed protesters as threats, instead portraying them as victims of state aggression. This embodies artivism’s power to reframe systemic violence. Its emotional charge, fueled by its tragic and historical significance, made it a rallying cry for justice. Its stark contrast of blood on white, reinforced by real-time evidence and subsequent revelations, indicts state brutality while honouring the sacrifices of the victims. As the image spread across social media, it bridged the local tragedy with global outrage, sustained the movement’s momentum, and solidified its place as a haunting yet enduring call for reform. As a rallying cry for justice, its emotional resonance and global reach ensure its enduring legacy as a testament to the #EndSARS struggle for reform.

7. Discussion of Findings

This study analyzes three #EndSARS art forms—Debo Adebayo’s satirical skit, Chigozie Obi’s Ezu River painting, and the Blood-Stained Flag photograph—to reveal artivism’s transformative power in reframing police brutality, countering government narratives, and mobilizing collective action through digital media. By operationalizing the four framing functions, these creative works address the research questions, revealing how visual, textual, and contextual elements amplify the #EndSARS movement’s impact. This discussion synthesizes the findings, situates them within global protest art scholarship, and highlights their unique contributions to Nigeria’s protest legacy, drawing parallels with movements like Black Lives Matter (BLM), the Polish Women’s Strike of 2020, and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement of 2014.

7.1. Problem Identification

The three art forms collectively frame police brutality as an urgent, systemic crisis rooted in state violence, aligning with Framing Theory’s problem identification function. Each piece employs distinct artistic strategies to humanize victims, expose abuses, and counter official attempts to portray protesters as mere criminals (). Adebayo’s skit, for example, brings the violence of SARS into focus through the story of Richard, whose narrative mirrors countless real-life testimonies. The tagline “E Fit Be You Next” (“You might be next”) universalizes the threat, reminding viewers that no one is safe from SARS’ unchecked power. Obi’s Ezu River painting confronts viewers with the 2013 Awkuzu SARS atrocities, depicting a lifeless boy floating in a blood-red river. The stark imagery unearths hidden abuses, forcing audiences to confront the scale of state violence. The Blood-Stained Flag, smeared with the blood of protesters killed during the Lekki Toll Gate massacre, stands as a symbol of state-sponsored brutality, transforming Nigeria’s national emblem into a cry for justice.

Comparative scholarship highlights art’s power to diagnose systemic injustices across global movements. () explores #EndSARS songs and artworks, like Chike’s “20.10.20”, which memorializes the Lekki massacre, and Laolu Senbanjo’s “DEMOCRAZY”, a searing critique of government corruption. These works frame SARS brutality as part of a broader web of systemic failures. Similarly, () examines BLM’s protest art, including graffiti on the Robert E. Lee statue, which visualizes systemic racism and police brutality as intertwined crises. In Poland, () highlights how Women’s Strike posters, such as Marta Frej’s image of a woman gagged by a Polish flag-coloured hand and Misior’s depiction of a woman crushed by a giant foot, frame abortion restrictions as structural violence. Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, as explored by Patsiaouras et al., used yellow umbrellas and the Lennon Wall’s Post-it notes to visualize electoral restrictions as threats to democratic autonomy ().

These global examples demonstrate how art names and visualizes systemic issues rooted in their socio-political contexts. #EndSARS art forms, like others, had deep ties to Nigeria’s socio-political context, drawing on local symbols and stories such as the bloodied flag or the Ezu River. They also leveraged digital platforms like Twitter to amplify their reach. For instance, () highlights how BLM murals, like those honoring Marcus-David Peters, who was killed by police, personalize systemic racism by centering victims’ stories, similar to the Ezu River memorializing Chijioke Iloanya. Both movements repurpose public symbols to identify the root problem and demand accountability. #EndSARS also leans into Nigeria’s oral and visual traditions, using satire and vivid imagery to make the crisis relatable to a broad audience. In Hong Kong, yellow umbrellas and Lennon Wall transformed urban spaces into platforms for dissent, visualizing resistance against China’s electoral restrictions (). Similarly, the #EndSARS movement uses art forms to transform physical and digital spaces into sites of resistance, bridging local and global audiences through Nigeria’s robust digital engagement.

Across these movements, art serves as a diagnostic tool, making systemic issues like police brutality, racism, electoral oppression, and reproductive injustice visible and urgent. The #EndSARS movement, for example, used Twitter to globalize local grievances, further amplifying their impact. This positioning not only reflects Nigeria’s resistance traditions but also constitutes a bold contribution to global protest art.

7.2. Causal Interpretation

Far from merely highlighting police brutality as a crisis, the three #EndSARS art forms dig deeper to expose its roots in systemic corruption and state impunity, aligning with Framing Theory’s causal interpretation function. Each piece strategically attributes blame to SARS and the Nigerian government, dismantling narratives that portray SARS as an essential crime-fighting unit. By weaving together local symbols, documented evidence, and the amplifying power of digital platforms, these works redirect the focus from victims or protesters’ misconduct to institutional failure, decisively challenging official denials and justifications.

Adebayo’s skit masterfully critiques societal complicity alongside state failure. Through the character of Daddy, who initially defends SARS as a necessary shield against crime, the skit dismantles the flawed logic that underpins such defenses. However, when Daddy’s son, Richard, falls victim to SARS’ violence, the story shifts, revealing how state impunity shatters even those who buy into its rhetoric. This personal tragedy, echoing countless real-life accounts shared on Twitter during the protests, highlights the devastating reach of SARS’ unchecked power. Obi’s painting, Ezu River, depicts a blood-red river cradling a lifeless boy’s body. This striking image serves as a powerful metaphor for systemic corruption. The painting connects the 2013 Awkuzu SARS atrocities committed by officers like James Nwafor to a broader pattern of institutional violence (). By transforming an individual tragedy into a damning indictment of the system, the painting effectively critiques the underlying issues. The “Blood-Stained Flag”, soaked in the blood of protesters killed during the Lekki Toll Gate massacre, directly implicates the military and police. Its accusations are supported by the 2021 findings of the Lagos Judicial Panel and a 2023 leaked memo confirming mass burials (; ). These artworks debunk government claims of “blank bullets” or “fake news”, anchoring their critique in concrete, verifiable evidence.

Comparative scholarship reveals how protest art across movements attributes blame to systemic oppression, drawing parallels to the approach of #EndSARS. () notes that #EndSARS artworks connect police brutality to government corruption, similar to Obi’s painting and The Blood-Stained Flag, which expose state complicity. () explores how BLM’s graffiti on Confederate statues and storytelling at ACLU town halls shed light on systemic racism and police impunity, rejecting state narratives that sanitize historical oppression. () examines Polish Women’s Strike art, such as Karolina Misior’s image of a woman crushed by a giant foot, which blames abortion restrictions on the authoritarian Law and Justice Party. () analyze Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, where banners caricaturing Chinese politicians and the Lennon Wall’s pro-democracy messages attribute electoral restrictions to China’s authoritarian grip. These movements all employ art to redirect blame from marginalized groups to oppressive systems, but #EndSARS stands out for its precise focus on documented atrocities and its use of digital media to broadcast this blame to a global audience.

Unlike problem identification, which frames police brutality as an urgent crisis, causal interpretation emphasizes its systemic roots in corruption and impunity. This approach goes beyond naming the issue, exposing its persistence and offering a sharper critique of institutional failures. While problem identification draws parallels with global movements to highlight art’s diagnostic role, causal interpretation focuses on how movements like #EndSARS use art to attribute causation. #EndSARS uniquely leverages digital platforms to globalize its message, and by grounding their accusations in specific, evidence-backed events, these art forms challenge state narratives and demand accountability on a world stage. This clarity and reach set #EndSARS apart.

7.3. Moral Evaluation

The three art forms go beyond exposing systemic corruption to ignite a deep moral outrage, aligning with Framing Theory’s moral evaluation function. Through gripping narratives, evocative imagery, and the subversion of cherished symbols, these works frame SARS’ violence as a profound betrayal of justice, uniting Nigerians across ethnic, generational, and class lines. By anchoring their messages in universal values like family, innocence, and national pride, they cast state violence as not merely unjust but morally reprehensible, fueling a collective demand for change.

Adebayo’s skit taps into the universal bond of family to evoke deep emotional resonance. Daddy’s journey, from defending SARS as a necessary force to grieving his son’s death at their hands mirrors the betrayal felt by countless Nigerians. This personal tragedy, rooted in the shared value of parental love, bridges generational divides, rallying both young activists and older citizens in a unified call for justice. Obi’s Ezu River painting captures the destruction of innocence by SARS’ brutality. The “Blood-Stained Flag”, soaked in the blood of protesters slain at the Lekki Toll Gate, transforms Nigeria’s emblem of unity into a symbol of martyrdom. This image evokes Nigeria’s shared trauma from state violence, such as the 2015 Zaria massacre, where hundreds were killed by security forces (). Its raw depiction of loss transcends ethnic boundaries, stirring a collective sense of moral violation. As commentator Segun Adeniyi wrote, such violence is “a stain on the conscience of any nation”, framing SARS’ actions as an unforgivable moral failing that demands a national reckoning ().

Protest art scholarship globally reveals how movements employ similar strategies to provoke moral indignation. For instance, () explores how Black Lives Matter (BLM) murals, such as the projection of John Lewis’ image onto the Robert E. Lee statue, frame systemic racism as a moral violation. Similarly, () highlights Polish Women’s Strike art that casts abortion restrictions as assaults on human dignity, uniting protesters from diverse backgrounds. () analysis demonstrates how Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement art invoked democratic values to inspire collective resistance. These movements, like #EndSARS, aim to condemn systemic issues through art, exposing betrayal of public trust and transforming them into urgent ethical imperatives.

Distinct from problem identification, which identifies police brutality as a systemic crisis, and causal interpretation, which traces its causes to corruption and impunity, moral evaluation focuses on the moral weight of these failures. The art forms do not just diagnose or explain the problem; they judge it, framing SARS’ actions as a violation of shared human values. Moral evaluation highlights how #EndSARS art fosters emotional unity and moral clarity. They not only condemn state violence but also galvanize a diverse populace to demand justice, making the moral case for resistance both universal and uniquely Nigerian.

7.4. Treatment Recommendation

Each piece does more than expose systemic injustices and spark moral outrage; they channel these emotions into actionable solutions, aligning with Framing Theory’s treatment recommendation function. By embedding calls to action, raising funds for justice, and fostering global solidarity, these works transform collective grief and anger into concrete steps toward systemic reform. Harnessing Nigeria’s dynamic digital landscape, particularly Twitter, they amplify these demands, connecting local struggles to international support and making #EndSARS a powerful example of digital-age activism.

Adebayo’s skit integrates hashtags like #EndSARS and #ReformPoliceNG into its narrative, urging viewers to join protests, sign petitions, and demand transformative changes, such as the dissolution of SARS and comprehensive police reform. This direct call to action resonates with Nigeria’s youth, who fueled the movement’s momentum through protests and online campaigns. Obi’s Ezu River, created during the live protest art session and auctioned to fund legal aid for arrested protesters, turns artistic expression into practical support (). Its creation process and purpose embody collective resistance, channeling the pain of loss into resources for justice. The Blood-Stained Flag, amplified by activists and re-created in solidarity across Nigeria and abroad, became a viral symbol of accountability. With over millions of Twitter engagements, it inspired solidarity protests in cities like New York, London, Toronto, and Berlin, intensifying pressure on the Nigerian government to address state violence.

Comparative scholarship highlights how protest art advocates for solutions to systemic oppression. () notes that #EndSARS songs and artworks push for SARS’ abolition and accountability, echoing demands for structural change. () describes BLM’s graffiti and photography, such as murals in Richmond, Virginia, spurred calls for removing Confederate statues and establishing civilian review boards to oversee police conduct. () highlights Polish Women’s Strike posters and songs, which advocate reproductive rights and foster solidarity among diverse groups. () analyze Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, where study corners and Lennon Wall’s pro-democracy messages promoted electoral reform and civic engagement. These art forms do not stop at diagnosis, causation, or condemnation; they propose and inspire tangible steps toward reform through Treatment recommendations.

8. Conclusions

Reframing Resistance: Artivism and the Legacy of Sòrò-Sókè

This study critically analyzed three pivotal art forms from Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement: Debo Adebayo’s skit “E Fit Be You Next”, Chigozie Obi’s painting Ezu River, and the uncredited photograph of The Blood-Stained Flag. These art forms demonstrated how creative expressions amplified protesters’ voices, countered government delegitimizing narratives, and mobilized resistance. The Nigerian state attempted to undermine the movement by framing protesters as fraudsters, criminals, or a radical minority unreflective of the broader populace. However, these art forms delivered compelling counter-narratives rooted in justice, resistance, and collective agency. Through satire, evocative imagery, and symbolism, they redirected public discourse, affirmed the movement’s legitimacy, and offered a global audience an unfiltered glimpse into the aspirations and grievances of Nigerian youth.

Central to this analysis is the paradoxical role of SARS, a government-sanctioned unit tasked with combating crime yet widely reviled for its brutality, corruption, and extrajudicial violence. This duality fueled societal ambivalence, with some viewing SARS as a “necessary evil” for security, complicating calls for its abolition. The analyzed art forms resolved this tension by reframing SARS from an ambiguous protector to a clear oppressor. Adebayo’s skit shattered apathy with personal tragedy, Obi’s painting memorialized victims like Chijioke Iloanya to indict state impunity, and The Blood-Stained Flag transformed a national symbol into a global cry against betrayal. Together, these works bridged individual experiences with collective outrage, dismantling the government’s justificatory rhetoric, and exposing the human cost of systemic abuses.

The significance of this case study lies in its demonstration of digital artivism’s transformative power within social movements. Unlike traditional protest methods, #EndSARS leveraged Twitter’s real-time engagement to globalize local grievances, a strategy that sets it apart from Nigeria’s previous protests and connects it to other global movements. BLM used murals and graffiti to localize resistance in cities like Richmond, Virginia (); similarly, Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement relied on spatial aesthetics like the Lennon Wall to transform urban spaces (), whereas #EndSARS fused physical symbols with digital platforms to bridge local and global audiences. The Polish Women’s Strike, with its localized street protests, songs, and posters (), shared similarities with #EndSARS but emphasized digital activism in a resource-constrained context. Twitter data from October 2020 revealed that the hashtag #EndSARS garnered over 28 million engagements globally, illustrating its ability to transform local grievances into a global conversation (). These distinctions highlight #EndSARS as a uniquely digital movement, yet its shared reliance on art to diagnose issues, attribute blame, evoke outrage, and propose solutions aligns it with global protest artivism.

Beyond countering narratives, these works served as both mirrors and catalysts within the Sòrò-Sókè movement. They reflected the lived experiences of police brutality while galvanizing local and global support, transforming passive outrage into sustained resistance. Their emotional resonance, amplified by digital platforms, underscored artivism’s ability to connect personal grief with communal resolve. Practical contributions, such as Obi’s painting funding legal aid, further illustrate art’s role as an active force in social change. By situating #EndSARS within Nigeria’s protest legacy, from the 1929 Aba Women’s Riot to 2024’s #EndBadGovernance protests, this study positions it as both a continuation of historical resistance and a blueprint for leveraging creative expression against systemic oppression.

The universal lessons from this case study resonate far beyond Nigeria. By studying digital artivism in movements like #EndSARS, scholars and activists gain insight into how marginalized groups articulate deep-seated grievances against political, economic, and social exclusion. The art forms analyzed here reveal the discontent of Nigerian youth, who are systematically disadvantaged yet empowered through creative resistance to demand accountability. This mirrors global struggles, such as BLM’s fight against systemic racism, Poland’s resistance to reproductive oppression, and Hong Kong’s push for democratic autonomy. In these struggles, art becomes a voice for those excluded from elite privileges. These studies illuminate the power of creative expression to humanize systemic injustices, foster solidarity, and preserve collective memory, offering a framework for understanding and supporting resistance worldwide. As historical artifacts, #EndSARS art forms not only preserve the movement’s spirit but also inspire future struggles, proving that art, amplified by media technology, can pierce denial and apathy to forge a path toward justice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A. and F.G.; Methodology, T.A.; Formal analysis, F.G.; Investigation, T.A.; Resources, F.G.; Data curation, F.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.A. and F.G.; Writing—review and editing, T.A. and F.G.; Supervision, T.A.; Funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Canada Research Chair (CRC) program and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) through funding awarded to Taiwo Afolabi. The Centre for Socially Engaged Theatre at the University of Regina received support from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the Faculty of Media, Art and Performance (MAP), and the University of Regina. Research partners in Nigeria included Theatre Emissary International (TEMi) and its social enterprise, Mobile Research Lab (MRL). The Article Processing Charge (APC) was partially funded by the Dean of the Faculty of Media, Art and Performance, University of Regina.

Data Availability Statement

This study utilizes data from a digital archive project conducted by the Centre for Socially Engaged Theatre (C-SET), led by Friday Gabriel and Dr. Taiwo Afolabi, documenting protest art’s role in resisting oppressive systems across social movements in Nigeria, the United States, Canada, Bangladesh, and other regions. Selected artworks analyzed herein are publicly accessible via social media platforms and online news outlets. The complete archive is openly available at www.artivism.ca/home accessed on 5 January 2025, providing access to resources supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLM | Black Lives Matter |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS | Special Anti-Robbery Squad |

Appendix A

- Skit Transcript: “End SARS now! E fit be You Next” by Debo Adebayo (Mr. Macaroni)

- Characters:Mr. Macaroni: DaddyMotunde: Mr. Macaroni’s DaughterRichard: Mr. Macaroni’s SonSARS Officer 1: Police officerSARS Officer 2: Police officerSARS Officer 3: Police officer{Mr. Macaroni steps out of his home onto the street, engaged in a phone call.}

- Mr. Macaroni: (Speaking on the phone) Let’s go.Motunde: (Rushing out to speak with her father) Daddy, you are the one I’m talking to.Mr. Macaroni: You are talking to me that what?Motunde: Daddy, I want to go and join the protest.Mr. Macaroni: What protest are you joining?Motunde: EndSARS now.Mr. Macaroni: Shut up your mouth! What do you know that is the meaning of EndSARS? (Motunde displays discontent.) Okay, all these youths that are shouting EndSARS, what job are they doing that they are driving big Benz?Motunde: (Surprised) Ah, Daddy!Mr. Macaroni: (Interrupting) What job are they doing? That’s why I called my friends now, all the religious leaders, the pastors, the imam, all of them. They are not saying anything. I don’t want to say we are jealous, but I’m concerned. During my own time, if you’ve not done 9–5, you cannot have money. You cannot have good money; you cannot live a good life. That’s why the government is not saying anything because they know that the youths will talk a bit and get tired.Motunde: (Expressing disagreement) It’s not supposed to be like this. Daddy, we are supposed to …Mr. Macaroni: (Cutting her off) Shut up your mouth! Are you suffering from SARS?Motunde: Daddy, is it until they catch me that I’ll suffer from them?Mr. Macaroni: (Interrupting) Shut up your mouth! Don’t worry. I will take you to my Ikoyi residence, the way my friends are doing. When your brother comes now, I will fly you abroad so no evil can come to you, no SARS can disturb you.{A police truck passes by; officers hail Mr. Macaroni.}SARS Officer 1: Ah baba!Mr. Macaroni: How are you? (Addressing the officer) SARS, well done, well done! Scorpion, the real Scorpion.SARS Officer 1: Na, you nah.Mr. Macaroni: (Referring to protesters) You see all these people shouting EndSARS? They are criminally minded.SARS Officer 1: They are criminals!Mr. Macaroni: Yes.SARS Officer 1: They are shouting EndSARS. In two or three days time, they’ll tired. {Motunde looks dismayed.}Mr. Macaroni: They will be tired; they will be tired, my brother.SARS Officer 1: You know why?Mr. Macaroni: Yes.SARS Officer 1: Government! Did they talk?Mr. Macaroni: Of course not.SARS Officer 1: Powerful people like you …Mr. Macaroni: That we should be talking. We are not dying anything. We don’t care.SARS Officer 1: In fact, as we are talking now, we just wasted one of them.Motunde: (Exclaiming) Hah!Mr. Macaroni: Okay, a criminal is there now?SARS Officer 1: We killed the criminal.Mr. Macaroni: Motunde, come so that you will know what this people are fighting for; they are protecting us from criminals like this.{Officers reveal the victim in the truck, shocking Motunde and Mr. Macaroni.}Motunde: (Exclaiming) Brother Richard! (Turning to her father, Mr. Macaroni) Daddy, see what I’m talking about. Brother Richard. Daddy, see! (Starts weeping){Mr. Macaroni slaps and lashes out at the officers.}Mr. Macaroni: Who is a criminal? This is my son now. Richard, Richard! (Mr. Macaroni clinched to his son’s body and was crying.){A flashback reveals the events leading to Richard’s demise.}Richard: (In pain) Please …SARS Officer 3: Are you mad? (Harassing Richard)SARS Officer 1: Get down! (Continues the assault) I said get down! We don’t use shiny jewelries; you are using shiny jewelries.Richard: Oh my God! What have I done? What have I done? (Desperate) Can I call my father?SARS Officer 1: It will not be well with your father!SARS Officer 2: (Commanding his colleagues) Waste this boy for me there now. {The officers fatally shoot Richard and carry his body.}SARS Officer 1: Anybody that’s fresh like this is a criminal.SARS Officer 2: Waste him.SARS Officer 3: It will not be well with you{They place Richard’s body in the truck}{Scene fades out}#EndSARS #EndPoliceBrutality #ReformPoliceNG(The End)

References

- Adeniyi, O. (2020, October 29). #EndSARS: Lekki and the blood-stained flag. The Herald. Available online: https://www.herald.ng/endsars-lekki-and-the-blood-stained-flag-by-olusegun-adeniyi/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Aderoju, D. (2020, October 21). Beyoncé, Rihanna, Demi Lovato, Diddy and more join Nigeria’s movement against police brutality. People. Available online: https://people.com/music/nigeria-end-sars-movement-celebrities-react/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Adiwu, T. O. (2022). Art forms in crisis: The role of songs and visual artworks created in response to the #EndSARS protests in Nigeria. Schweizer Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft, 39, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Agbo, G. E. (2021). The #EndSARS protest in Nigeria and political force of image production and circulation on social media. IKENGA: International Journal of Institute of African Studies, 22(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AHA. (2004). Riot or rebellion? The women’s market rebellion of 1929. American Historical Association. Available online: https://www.historians.org/resource/riot-or-rebellion-the-womens-market-rebellion-of-1929/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Akoleowo, V. O. (2022). African feminism, activism and decolonisation: The case of Alimotu Pelewura. African Identities, 22(4), 963–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. (2016). Nigeria: Military cover-up of mass slaughter at Zaria exposed. Amnesty International Report. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/04/nigeria-military-cover-up-of-mass-slaughter-at-zaria-exposed/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Amnesty International. (2018). Nigeria: Security forces must be held accountable for killing of at least 45 peaceful Shi’a protesters. Amnesty International Report. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2018/10/nigeria-security-forces-must-be-held-accountable-for-killing-of-at-least-45-peaceful-shia-protesters/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Amnesty International. (2021). The Lekki Toll Gate shooting: Between denials and half-truths. Amnesty International Report. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2021/02/nigeria-end-impunity-for-police-violence-by-sars-endsars/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Ansari, A., & Brueggeman, T. (2014, May 4). Demand for return of hundreds of abducted schoolgirls in Nigeria mounts. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2014/05/03/world/africa/nigeria-abducted-girls/index.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- BBC. (2020, April 17). Coronavirus: Security forces kill more Nigerians than COVID-19. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52317196 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Busari, S. (2012, January 13). What is behind Nigeria fuel protests? CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2012/01/06/world/africa/nigeria-fuel-protest-explained/index.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Byfield, J. A. (2003). Taxation, women, and the colonial state: Egba women’s tax revolt. Meridians, 3(2), 250–277. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338582 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Channels TV. (2023). Leaked memo shows Lagos govt approved N61m for mass burial of 103 ENDSARS victims. Channels Television. Available online: https://www.channelstv.com/2023/07/23/leaked-memo-shows-lagos-govt-approved-n61m-for-mass-burial-of-103-endsars-victims/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Dambo, T. H., Ersoy, M., Auwal, A. M., Olorunsola, V. O., & Saydam, M. B. (2022). Office of the citizen: A qualitative analysis of Twitter activity during the Lekki shooting in Nigeria’s# EndSARS protests. Information, Communication & Society, 25(15), 2246–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbejule, E. (2021). Panel of inquiry finds Nigerian army culpable in Lekki ‘massacre’. Aljazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/11/16/panel-of-inquiry-finds-nigerian-army-culpable-in-lekki-massacre (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erunke, J. (2017, December 3). #EndSARS: We won’t scrap SARS, police reply anti-SARS campaigners. Vanguard. Available online: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/12/endsars-wont-scrap-sars-police-reply-anti-sars-campaigners/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Ezeugwu, C. A., Omeje, O. V., Erojikwe, I., Nwaozuzu, U.-C., & Nnanna, N. (2021). From stage to street: The #EndSARS protests and the prospects of street theatre. IKENGA: International Journal of Institute of African Studies, 22(2), 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITV News. (2020, October 21). Beyonce adds voice to #EndSARS campaign after protests in Nigeria over police brutality. ITV News. Available online: https://www.itv.com/news/2020-10-21/beyonce-adds-voice-to-endsars-campaign-after-protests-in-nigeria-over-police-brutality (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Jaja, S. O. (1982). The Enugu Colliery Massacre in retrospect: An episode in British administration of Nigeria. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 11(3/4), 86–106. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41857119 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Kazeem, Y. (2020). How a youth-led digital movement is driving Nigeria’s largest protests in a decade. Quartz Africa. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/1916319/how-nigerians-use-social-media-to-organize-endsars-protests (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Kądrzycka, A. K. (2022). I love freedom!—The role of art in social movements: Women’s strike protests in Poland 2020 [Master’s thesis, The Arctic University of Norway]. [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin, I., & Tsegyu, S. (2022). #EndSARS Protest: A discourse on the impact of digital media on 21st-century activism in Nigeria. Galactica Media: Journal of Media Studies, 4(4), 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, E., & Busari, S. (2020, October 21). President calls for calm after protesters shot during Nigeria demonstration. CNN. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/10/21/africa/nigeria-protests-eyewitnesses-intl/index.html (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Mobaraki, A. (2021). Art as protest: How creative activism shaped “Black Lives Matter” in Richmond, Virginia. The Yale Undergraduate Research Journal, 2(1), 21. [Google Scholar]

- Odion-Akhaine, S. (2009). The student movement in Nigeria: Antinomies and transformation. Review of African Political Economy, 36(121), 427–433. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27756290 (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Okorie, E. N. (2020). Annulment of June 12, 1993, presidential election and the elusive question for democracy in Nigeria. South East Journal of Political Science, 5(1), 27–40. Available online: https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/SEJPS/article/view/1334 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Olabimtan, B. (2021a, February 27). Did Bovi’s #EndSARS outfit violate the national flag act? The Cable NG. Available online: https://www.thecable.ng/did-bovis-endsars-outfit-violate-the-national-flag-act/amp/# (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Olabimtan, B. (2021b, December 5). Lagos releases #EndSARS panel report. The Cable. Available online: https://www.thecable.ng/download-lagos-releases-endsars-panel-report/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Olonilua, A. (2020, October 20). #EndSARS: DJ Switch, others help protesters shot at Lekki Toll Gate. Punch NG. Available online: https://punchng.com/endsars-dj-switch-others-help-protesters-shot-at-lekki-toll-gate/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Omeni, A. (2022). Policing and politics in Nigeria: A comprehensive history. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Oyemakinde, W. (1975). The Nigerian general strike of 1945. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 7(4), 693–710. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41971222 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Patsiaouras, G., Veneti, A., & Green, W. (2018). Marketing, art and voices of dissent: Promotional methods of protest art by the 2014 Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Marketing Theory, 18(1), 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princewill, N. (2021, June 29). How a Nigerian model used a Russian beauty pageant and a bloodied flag to protest police brutality. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/29/africa/nigerian-model-russia-pageant-intl/index.html (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Sahara Reporters. (2020). Awkuzu: Untold stories of SARS’ deadliest den. Sahara Reporters. Available online: https://saharareporters.com/2020/10/20/awkuzu-untold-stories-sars-deadliest-den (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Sanusi, A. (n.d.). #ENDSARS protest live art. Ayo Sanusi. Available online: https://ayosanusi.com/endsars-protest-live-art (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- SBM Intelligence. (2020). Chart of the week: Bloody tuesday. SBM Intelligence. Available online: https://www.sbmintel.com/2020/10/chart-of-the-week-bloody-tuesday/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Siyanbola, A. B., Uzzi, F. O., & Adeyemi, O. A. (2023). The evocative role of arts in social movements: A digital illustration of visual imageries emblematizing Nigerian EndSARS protests. Journal of Fine Arts, Chiang Mai University, 14(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Uwalaka, T. (2024). Social media as solidarity vehicle during the 2020 #EndSARS Protests in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 59(2), 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).