Abstract

Europe is dealing with environmental problems that require cooperation beyond national and regional borders. Air pollution, water pollution, biodiversity loss, and waste management are the major issues that are not only complex but also cross borders. Therefore, it is necessary to provide collaborative responses that go beyond the capacity of individual countries. This inquiry centers on the question of what the best way is to set up and govern the transnational cooperation in Europe to confront these major environmental challenges. A systematic bibliographic review of the research conducted between 2010 and 2025 forms the basis of this work. The research combines semantic analysis and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) modeling to study 80 selected publications to find the tenets of the themes discussed. The identified topics are urban climate change adaptation and mitigation, climate policy and management, adaptation and vulnerability frameworks, land use and biodiversity impacts, and future climate projections and assessment. The findings show that there are strong synergies between biodiversity and climate adaptation, resilience, and environmental governance, as well as the great influence of climate change on the water management sector. The study has unveiled the significance of institutional policy frameworks in bringing about environmental cooperation across borders. In addition, it depicts the relationship between local urban projects and supra-regional policy strategies, in which the two can merge and function efficiently as long as they are working towards the common goal of environmental sustainability. This study is meant to shed more light on the area of environmental governance research, discovering areas that need more exploration, and providing some signposts on how to improve environmental involvement in Europe.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, environmental issues have become one of the most serious problems, which affect ecosystems, economies, and societies worldwide. Specifically in Europe, these issues appear as the significant consequences of a bad environment, for example, the waste management problem, air and water pollution [1,2], and deforestation. A few of these issues, like air pollution and marine degradation, do not recognize borders [3,4], making them inherent threats that require an international response. This makes a distinction that is quite important, as it outlines the need for decision-makers to be aware of the nature of environmental problems so that resources and efforts can be channeled appropriately [5,6]. Everything must be carried out in the most efficient way, which means that the least number of available resources are maximized.

These environmental challenges [7] have emerged as some of the most critical issues of the era, as they influence ecosystems, economies, and societies in every country of the world. Most of the problems in Europe can be exemplified by climate [8], biodiversity loss, air pollution, water pollution, deforestation, and waste management, but they can be stated as the main and specific factors which vary from region to region [3,4]. Different issues beyond the point of no return in the areas of pollution and deletion are environmental problems.

The societal implications of the environmental situation in Europe are deep and extensive. For instance, the climate is changing [9], with more floods, heatwaves, and droughts directly affecting human beings, infrastructure, and food security [10]. Biodiversity reduction leads to disturbances in ecosystem functions that are essential for agriculture, fisheries, and the ecosystem services that societies are dependent on for their livelihood and well-being [11,12]. The pollution of air, water [13], and land, as well as their related public health problems, has been the subject of a number of crises, with air pollution primarily target urban populations, who have the highest vulnerability to diseases related to air quality [14]. Apart from that, waters are polluted [15] by plastic waste, and coastal and marine environments have become environments where marine biodiversity and the fishing industry are under increased risk, thus negatively affecting the lives of people in coastal areas [16,17]. The interrelated causes of these environmental problems also have serious implications for the state of the economy [18]. Thus, for instance, the EU spends billions of EUR annually to implement measures of climate adaptation and mitigation [19]. Also, disparities in terms of physical and social distribution directly contribute to the multi-layered problems; those who are most affected always suffer the most [20,21]. The recognition of these cascading consequences calls for the application of integrated and collaborative environmental governance.

However, not all environment-related problems can be solved without the help of more than one country. Indeed, some environmental problems are global in nature, which means they require the cooperation of the global community, such as:

- Climate Change: A heating climate, more frequent extreme weather, and climate-induced sea level rises are the real causes of difficulties and need the implementation of coping and prevention measures beyond the national scale due to the very nature of greenhouse gas emissions and their consequences [3,10].

- Air Pollution: Particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), the major pollutants in air, are examples of transboundary air pollution that is created in one country but travels to other nations and spreads in regional areas, such that regional agreements [22] become a necessary approach [12,14].

- Water Resource Management: The joint management of rivers that are shared by two or more nations, e.g., the Danube and Rhine Rivers, presupposes transborder cooperation, as only in this way can sustainable use and cleanliness be secured [23,24].

- Marine Pollution: The garbage problem, uncontrolled fishing, and the loss of habitats in the Mediterranean and North Seas oblige the international society to come together and save the sea ecosystem [16,17].

- Biodiversity Loss: The Natura 2000 network in the European Union is an excellent example of how cooperation between different countries is effective in the protection of habitats and animal species that are beyond political borders [11].

While local waste management practices or urban greening projects [25] are examples of challenges that can be effectively addressed at the national or municipal level, coordinated action is the right choice for issues that are really wide and complex. It also shows that governance that is one-size-fits-all is not the best choice still [26].

Even if cooperation projects on environmental protection in Europe have been successful, some of the research has portrayed various deficiencies in the domain [27,28]. The first of the research gaps is that most of the research has concentrated on climate policy [28] or biodiversity and has not covered a full analysis of how transnational cooperation works across different environmental areas [3,4]. The second is that, despite the fact that successful cases are often talked about, the reasons for the failures are only partially understood, and the problem of overcoming barriers is neglected [6,20]. Moreover, the political, cultural [29], and socio-economic differences between European countries require an investigation of their contribution to the success of the cooperation efforts, particularly in the environment of the current geopolitical shifts [21,30]. This research aims to comprehend how cross-border environmental collaboration in Europe can be successful by looking into factors that have an impact on the positive or negative outcome of such a collaboration [31]. The main question to be answered is the manner of creating an effective structure and governance for handling not only climate change, loss of biodiversity, and pollution but also for facilitating the breakthrough of the current management gridlocks by investigating the state of the art and suggesting ways of breaking through.

With this objective in mind, the first and foremost important purpose of the bibliographic review is to carry out a comprehensive exploration of the transnational cooperation of environmental issues in Europe [32]. By giving the causes, barriers, and opportunities an in-depth coverage, the review sets out to reach the following objectives: (1) to identify and catalogue the chief environmental problems in Europe that could be resolved by transnational cooperation, (2) to evaluate the regulatory and governance frameworks that are either an obstacle to or a stepping stone for cooperation, (3) to disclose the best practices and what has been learned from past initiatives, (4) to appraise the role of political, economic, and cultural factors in cooperation, and (5) to design proposals that would lead to better transnational cooperation on environmental issues in Europe.

Finally, the main intent behind the review is to come up with ideas that will make environmental governance in Europe more effective and fairer so that the countries involved can jointly address the challenges happening next door under their national situations and priorities [33].

2. Literature Review

The discussion to implement transnational cooperation in the area of environmental policy in Europe [1] has grown over the last few decades [34] in both scientific and political contexts [35]. This is mainly because environmental problems are becoming increasingly complex and linked and, hence, do not obey any national boundaries. Transnational environmental governance is proposed as a powerful instrument to capture environmental pressures and deliver, if possible, appropriate reparations [36,37,38,39].

The wide-ranging definitions of transnational climate cooperation would really refer to types of cooperation based on countries [40], which may be at the level of bilateral treaties as one end or at the level of transnational, non-governmental organizations operated from several countries [5]. The models designated are the neo-realistic and neo-liberal schools of thought, which see the problem of international relations through different aspects. Whereas the realist approach is by nature power–security oriented, the liberal one grasps the very need for cooperation and institution-building to attain some modicum of a “common good” [28,41,42].

The topics concerning the environment which Europe is addressing are numerous and complex. Some of them include climate change [43], loss of biodiversity, water contamination, and air pollution [10,14,17,44]. The enormity of these problems can only be dealt with through international solutions, affecting the health and livelihood of millions [45]. “A sizable number of environmental issues must be tackled with great success in international cooperation, at least for Europe” [22,46,47]. Climate change remains one such critical issue crossing over into the larger global political agenda [48] rather than remaining inside national borders, as its repercussions do not restrict themselves within any nation [49,50].

Environmental cooperation amongst states is interesting in its current expansion and diversity in approach [49,51,52]. Many studies place more emphasis on other dimensions of cooperation [53]. For example, there are legal frameworks [54,55], cooperation through institutions [33,56], and the role of civil society [8,57]. Cooperation depends mostly on the kind of exchanges that have taken place between the cooperators, that is, past interactions. Personal experience with either conflict or cooperation is a driving force. Cooperation cannot take place in a vacuum [58]. For cooperation to take place, actors must feel secure, and engagements must bear fruit [59]. Koch [60] said, “Successful collaboration is based on the history of conflict or cooperation, the incentives for participants, the power and resource imbalances, the leadership, and the institutional design” [61]. Although the existing literature covers particular case studies, such as European climate governance [56] and water management initiatives [13,62], empirical evidence is often insufficient to fully explain the dynamics of transnational cooperation. Nonetheless, these findings lead toward an understanding [63].

Suitable regulations function as a precondition for fostering effective cooperation among countries. Different agencies operate cooperations on environmental concerns in the European Union [64] and the European Environment Agency, thus creating continental foundations [65,66]. These systems represent the legal framework essential for the cooperation platform and information and best practice sharing [35]. The European Union goes through a number of laws concerning environmental matters, such as the Water Framework Directive and the Air Quality Standards Directive, which shows a fair amount of commitment towards such policy initiatives [67]. However, different countries have different policies and priorities that sometimes make cooperation conducive [68].

The drivers of transnational environmental cooperation may seem positive theoretical elements [69], but we should not forget to acknowledge negative aspects of transnational cooperation [48]. Key success factors include sound institutional design, well-defined objectives, transparency, and the commitment of all actors involved [26]. National interests, cross-jurisdictional challenges, unequal distribution of resources, and the absence of a common vision for environmental policy impede effective cooperation [24,70]. Such dynamics are likely to structure the domain of transnational collaboration in Europe and indicate the directions of future discourse and research in the academic world [9,71].

The literature is replete with publications indicating that researchers are still working on the issue, especially on some mechanics and conditions that facilitate cooperation [43,56]. Analyses of existing approaches, challenges, and opportunities should therefore at once contribute to scientific debates and serve to guide policy decisions for European countries [35] to arrive at effective and sustainable solutions for pressing environmental challenges [72,73]. Works by Haas [7] and Cashore [2] remain a source of insights for argument and discussion in broadening the dimensions of complexity of transnational environmental cooperation [60,74,75]. The dive into the literature review shows that five main themes largely speak of transnational environmental cooperation in Europe. These themes, their main results, research issues, and frequently employed strategies extracted from the writings are systematically laid out in Table 1. This organized overview is the conceptual base of the current work, figuring out the knowledge clusters that exist and which the next analytical methods (semantic analysis and LDA modeling) will confirm, elaborate, and analyze for their connections inside the sampled document corpus.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings from the systematic literature review on transnational environmental cooperation in Europe (2010–2025), organized by the five main thematic clusters identified through LDA modeling.

3. Materials and Methods

This study is based on a systematic and planned analysis of the literature (systematic literature review), recognized as the optimal method for effectively collecting research results, identifying knowledge gaps, and discovering recurring thematic patterns within a specific time frame [76]. The chosen methodology was designed to ensure a comprehensive and holistic approach to the complex issue of cross-border environmental cooperation in Europe. Understanding the dynamics, challenges, and conditions associated with global environmental cooperation and, in particular, identifying the key determinants of its success or failure would not be possible without the use of such a rigorous analytical framework [77].

The methodological approach adopted combines a solid theoretical foundation with an empirical analysis of the literature. This means that the framework not only organizes existing knowledge but also allows for its critical evaluation in the context of identified theoretical models of cooperation. This dualism is key to achieving an in-depth interpretation and goes beyond a simple compilation of publications. Therefore, the critical importance of having a methodological framework that is rooted in theoretical models and at the same time based on a detailed discussion of the literature is the main argument justifying the choice of this method [78].

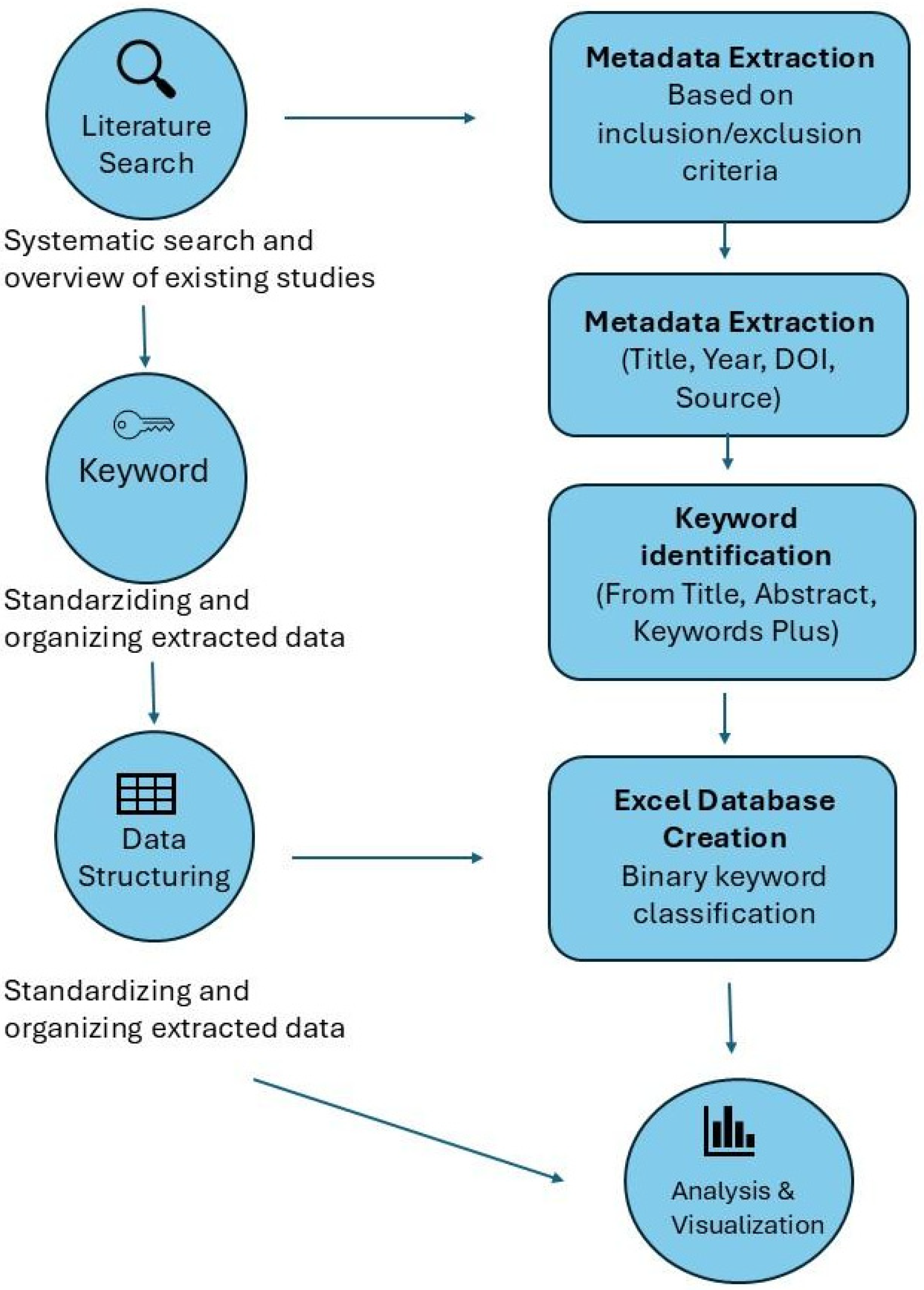

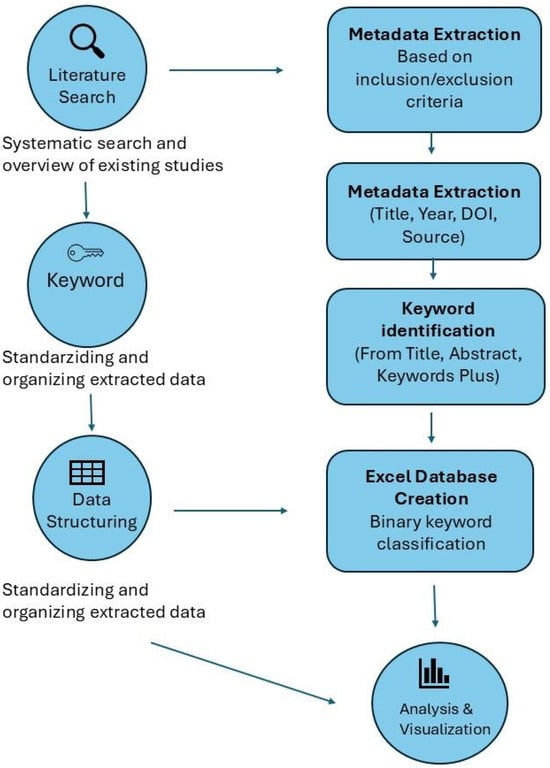

The concept of this article is based on an analysis of studies conducted between 15 January 2010 and 15 January 2025, which were retrieved from the Web of Science database. However, the review, which is not fully compliant with PRISMA standards, uses an individual systematic approach tailored to the scope and objectives of the study. Using tools such as semantic analysis and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) modeling, the authors have gained a comprehensive understanding of what is happening in cross-border environmental cooperation in Europe through a very detailed review of the literature. The method used combines the best features of social science methods with quantitative methods, revealing the interrelationships, characteristics, and connections present in the selected literature collection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological flowchart of the study, summarizing the main stages of the systematic bibliographic review, from the database search and article screening to semantic analysis and LDA topic modeling.

The exploration of the pertinent literature was accomplished by searching the Web of Science database, which is the source of a large number of peer-reviewed articles spanning multiple fields. The articles were selected methodically through a certain combination of 10 keywords (biodiversity, climate change impacts, ecosystem services, governance, policy, water management, sustainability, carbon storage, resilience) which are related to “transnational cooperation,” “environmental governance,” “EU climate policy,” “biodiversity conservation,” and “climate change adaptation.” These words were intentionally chosen so as the literature they point to would be that which reflects the interaction of environmental challenges and cooperative governance processes across borders [36]. The searches were not restricted by the country, but only research within the European context was selected. Studies conducted outside the EU were excluded by the authors in the preliminary literature review because they were not relevant to the topic of the study. The search string that was used is as follows: (((TS = (‘transnational cooperation’)) OR TS = (‘regional cooperation’))) AND TS = (‘environmental governance’) AND (TS = (‘climate change adaptation’) OR TS = (‘biodiversity conservation’) OR TS = (‘EU environmental policy’)). The search was expanded to include publications from both scientific journals and the grey literature, excluding articles that had not been peer-reviewed, were not necessarily from international organizations, and mainly concerned the intensification of climate change and migration. In total, 80 peer-reviewed research articles (Appendix A) were confirmed for the research. Data was collected from the relevant research under evaluation, and comprehensive analyses were conducted on each paper to extract essential information. The information included the paper’s title, publication year, keywords, primary objectives, methodologies employed, and study findings. The titles of the articles were enumerated in an Excel spreadsheet, where each relevant piece of information was recorded systematically. The “Keywords Plus” method, which is an automatically generated feature by the Web of Science (WoS) database based on the titles of cited articles, was used to structure the list of keywords that would be used to generate automatic keywords based on citation data and to ensure that the selection of terms was not influenced by the authors’ perspectives. This method, which utilizes citation data to assign additional descriptive terms, guarantees that the selection of terms is objective and not influenced by the authors’ subjective perspectives, thus covering a broader thematic scope of the literature [79,80,81]. This approach helps in making a more bias-free and inclusive portrayal of the major themes present in the literature. Connecting “Keywords Plus,” the authors were able to find common terms that were noticeable in the studies, which thus helped the authors to better see what the literature was all about.

The evaluation of the content of the articles was performed by semantic analysis using VOSviewer 1.6.20 [82,83], a leading software tool for creating and illustrating bibliometric networks. We used VOSviewer 1.6.20 to analyze the co-occurrence of author keywords and Keywords Plus to delineate the topical clusters and figure out the prevalence of themes in the set of texts. The analysis was limited to producing a keyword co-occurrence map and a heatmap, where the link strength between words signified the number of times those keywords were used jointly in the same article. We opted for full counting as our counting method to make sure that every occurrence of a keyword in an article was given the same weight in the network construction [83,84]. This data analysis based on the resulting keyword co-occurrence heatmap thus very efficiently revealed the major themes and their interrelationships in the field of transnational environmental cooperation.

The Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model was employed to delve into the data and identify the central themes of the literature that was passed through the aforementioned feature extraction method. For this, the Gensim library in Python 3.11 was used. The LDA model is a perfect example of a natural language processing concept widely used in machine learning that, in large text datasets, discovers hidden topic structures [84]. The model that was used went through all the texts of the selected articles, thereby connecting them together by main topics and keywords.

4. Results

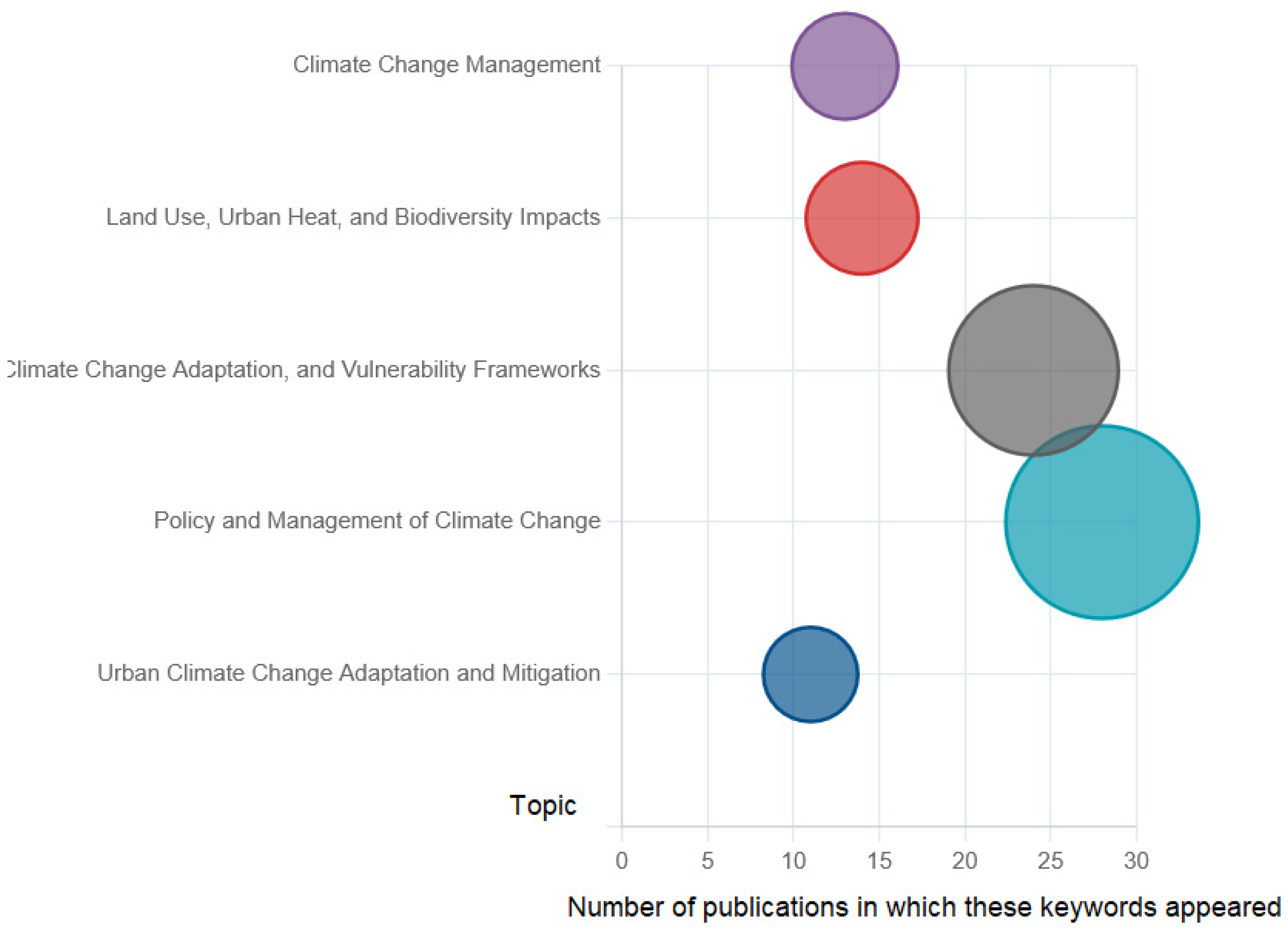

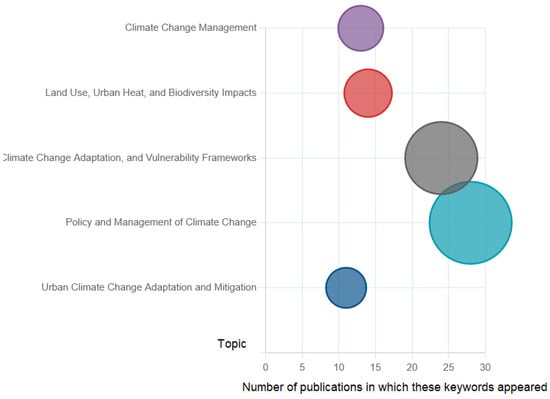

This method consequently helped to spell out the most major fields of themes of the trend and tested the environmental aspect of the globe in international settings with the emergence of sub-topics. The LDA thematic model presents five main themes identified in the 80 publications. Each bubble represents one theme. The X-axis shows the number of publications assigned to each topic, and the Y-axis shows the topic number. The size of the bubble is proportional to the share of the topic in the entire collection, reflecting its importance and dominance.

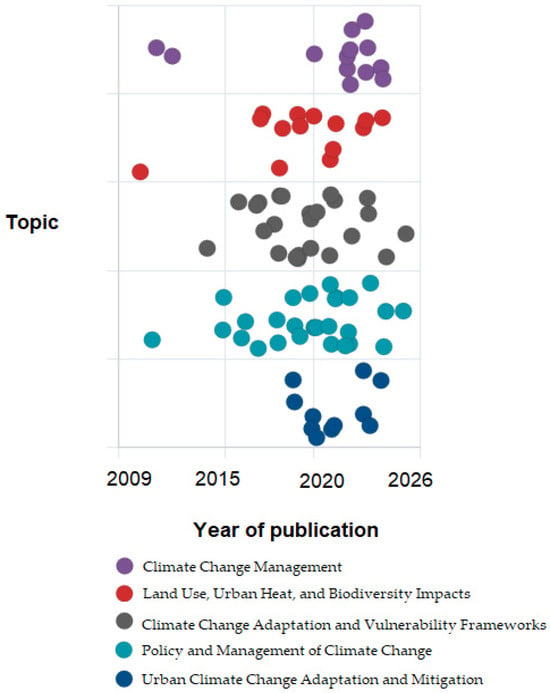

The LDA modeling (Figure 2) picked up five major thematic groups in the literature, providing a systematic summary of the main regions of transnational environmental cooperation activities:

Figure 2.

LDA model output showing the distribution of documents across the five main topics identified in the literature on transnational environmental cooperation in Europe.

- Urban Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: This theme puts a spotlight on the role of urban planning, ecosystem services, and renewable energy in the context of climate change

- Policy and Management of Climate Change: The policy cluster is indicative of the fact that the major thrust of the policy is to adopt set targets, carbon management, and conservation in the fight against climate change.

- Climate Change Adaptation and Vulnerability Frameworks: By applying the concept of vulnerability analysis, planning, and user awareness, one may say that the trend is mostly about the measures to be taken for achieving adaptation to climate change and the vulnerability of humans [58].

- Land Use, Urban Heat, and Biodiversity Impacts: This is where the issues of sustainable land management [69], urban heat island mitigation, and biodiversity conservation discussed were found as the solutions to create climate-friendly cities of the future.

- Climate Change Management, Future Projections, and Assessment: This thematic group involves planning, monitoring, and global cooperation [60], which are parts of the future imagining and the assessment thereof. In brief, the mentioned themes refer to the different levels of transnational environmental cooperation, which range from local to general policies.

The themes selected in combination reflect the diverse nature of global environmental cooperation [17], including city-related activities as special measures and general policy frameworks as well.

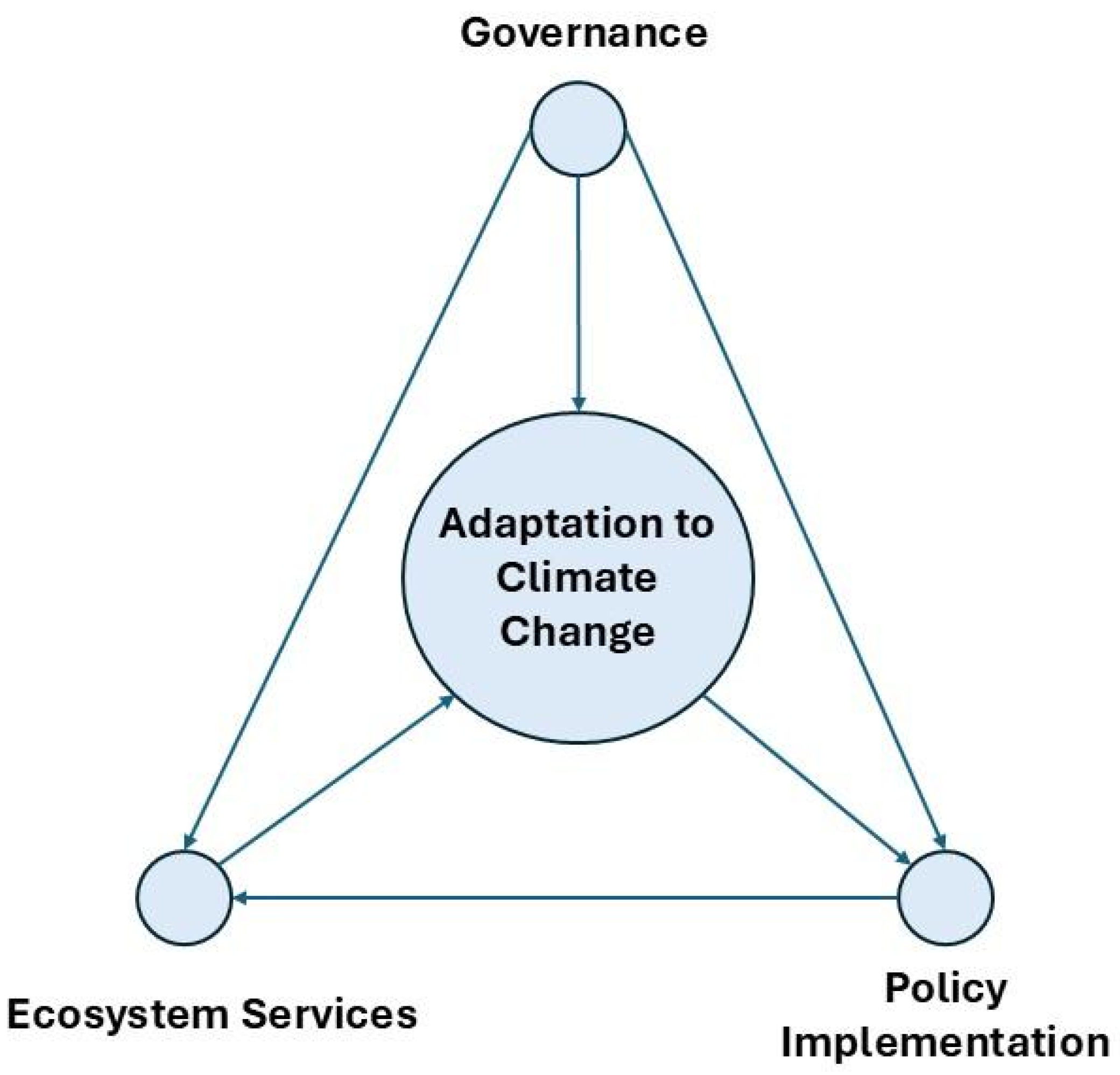

The network and density visualizations obtained from the semantic analyses reveal additional details about the interconnections between the main themes and the intensiveness of research. The network analysis clearly shows the significance of “adaptation to climate change” as the most relevant topic, being closely related to “ecosystem services,” “governance,” and “policy implementation,” thereby expressing the dependence of these factors on transnational environmental cooperation. The density maps back up the former and more vividly characterize the share of climate adaptation [65], biodiversity, and governance topics, suggesting that they are areas of priority for discourse on transnational cooperation.

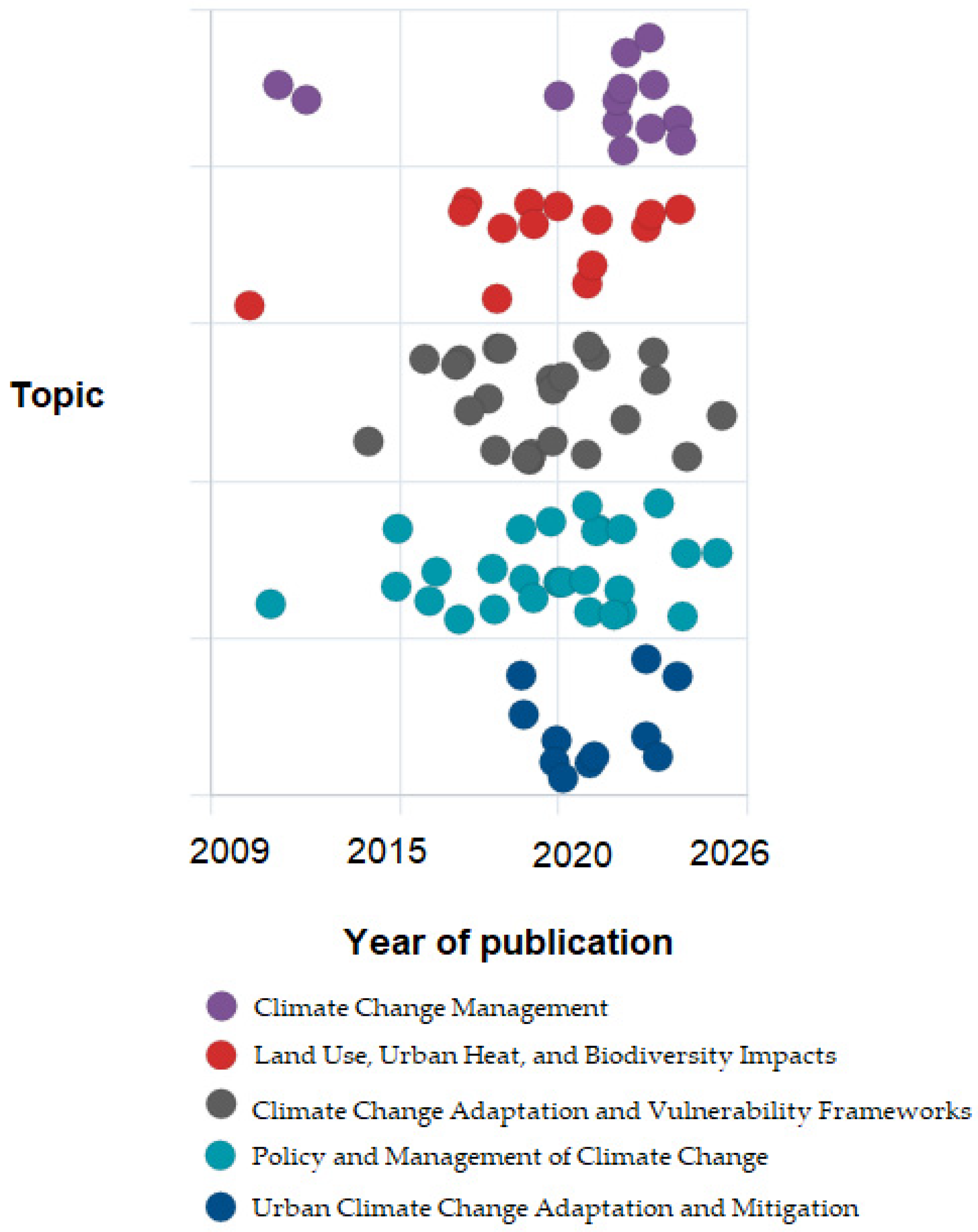

A two-dimensional t-SNE-like clustering plot is shown in Figure 3. This plot is a representation of the semantic structure of the sample document corpus, derived from Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) modeling. The LDA model was specifically configured to extract five distinct thematic topics, based on criteria such as model coherence and perplexity scores. The determination of the descriptive label for each cluster (Topic 1 through Topic 5) was achieved through a qualitative, in-depth analysis of the top 20 most frequently co-occurring words and the most representative documents within each automatically generated cluster. Such a scatterplot, derived from LDA, not only explores but also categorizes the five most substantial thematic clusters of the transnational environmental cooperation literature in Europe. The main idea with this representation is that any single document is a point, and the closeness of two points in the two-dimensional space gives an indication of the topical similarity of the two documents. The closer two points are, the more similar their topic distributions, which allows for an intuitive understanding of the relationships between individual publications. The distinct clusters, visually delineated by color— purple, red, grey, light blue, and dark blue—correspond to the following main themes, which were labelled based on the dominant keyword content and context of the documents in each cluster: (1) Urban Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation, (2) Policy and Management of Climate Change, (3) Climate Change Adaptation and Vulnerability Frameworks, (4) Land Use, Urban Heat, and Biodiversity Impacts, and (5) Climate Change Management, Future Projections, and Assessment. The lack of significant overlap between these clusters visually confirms the efficacy of the LDA model in identifying logical and well-defined topics. This spatial separation suggests that the model successfully condensed a large amount of text data into a coherent and easily interpretable medium, projecting high-dimensional word-count vectors into a lower-dimensional space while preserving the local and, to a large extent, global structure of the data.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional representation of the five LDA topics, where each point corresponds to one publication and spatial proximity indicates similarity in topic composition.

This visual is an essential element for the semantic analysis, visually expressing the connections between the main themes that go beyond the topics of climate adaptation, governance, biodiversity, and policy integration. The figure not only reflects the “what is already there” in the discussions of the subject area but also points out the unresolved issues and possible gaps in research. By this means, the chart is a complete thematic map of the literature that can provide advice for the academic world and decision-makers in the area of environmental governance in Europe.

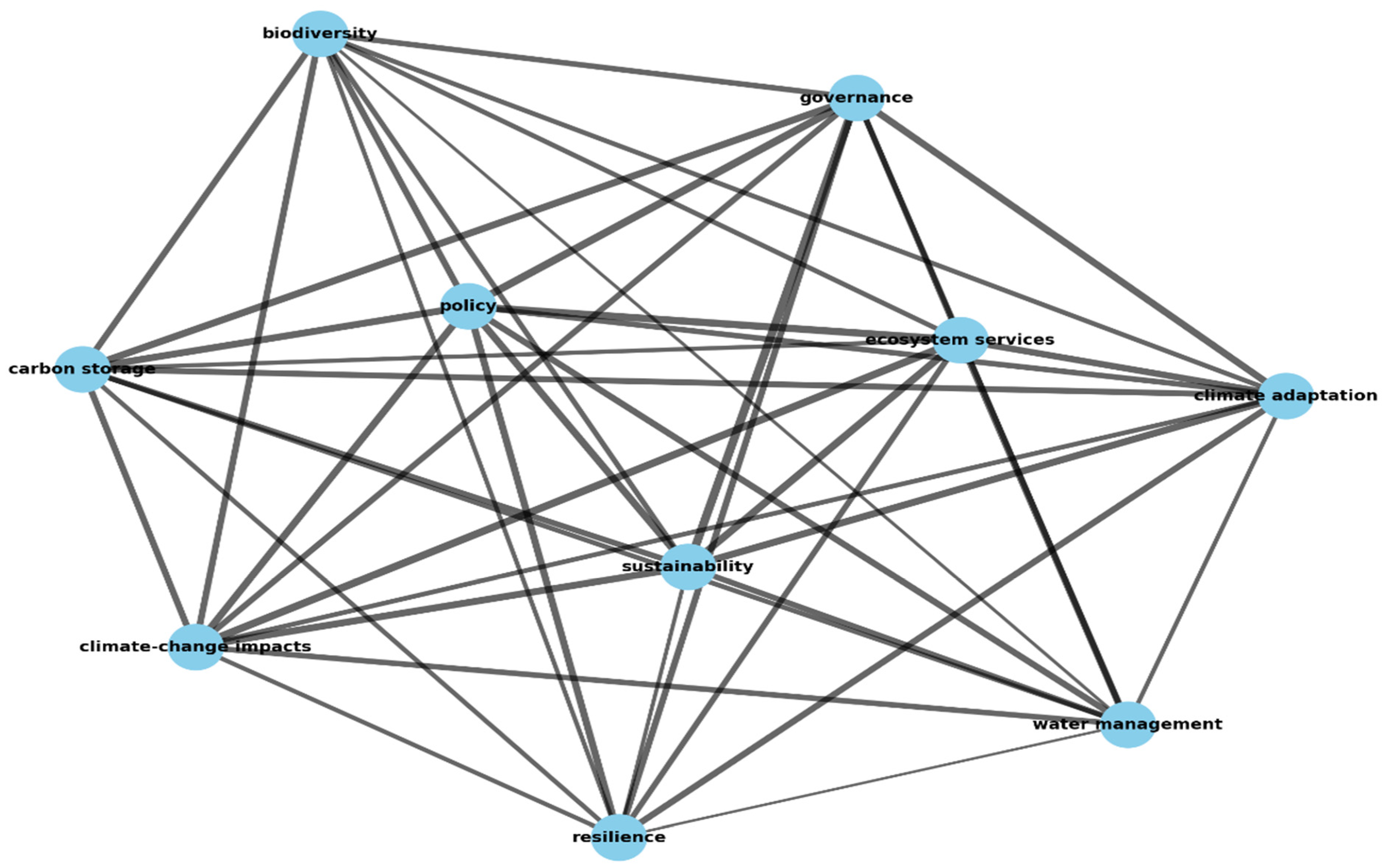

The examination of 80 works of the scholarly literature issued between 2010 and 2025 and taken by the Web of Science database has unveiled principal factors characterizing transnational environmental cooperation in Europe. By utilizing VOSviewer, a semantic analysis technique, some of the co-occurrence patterns of keywords that represent the thematic groupings and relationships of keywords in the text were found. The thickness of the lines in this graph, created using VOSviewer for semantic analysis, indicates the strength of the association or frequency of co-occurrence between the linked keywords. A thick line shows a higher association. For instance, if we take two keywords (e.g., “biodiversity” and “ecosystem services”), a strong association would mean that these two terms were most likely to co-occur in the 80 scientific papers that were examined. A thin line shows a lower association or less frequent co-occurrence. In summary, the line thickness is a way of visually showing how frequently and how close topics are in the research literature, thus uncovering the major linkages in the field of transnational environmental cooperation.

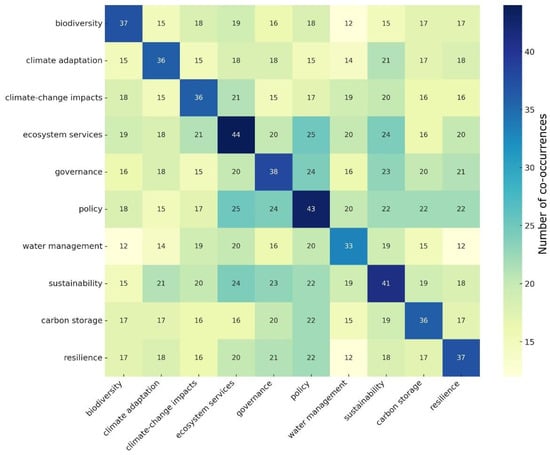

Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis:

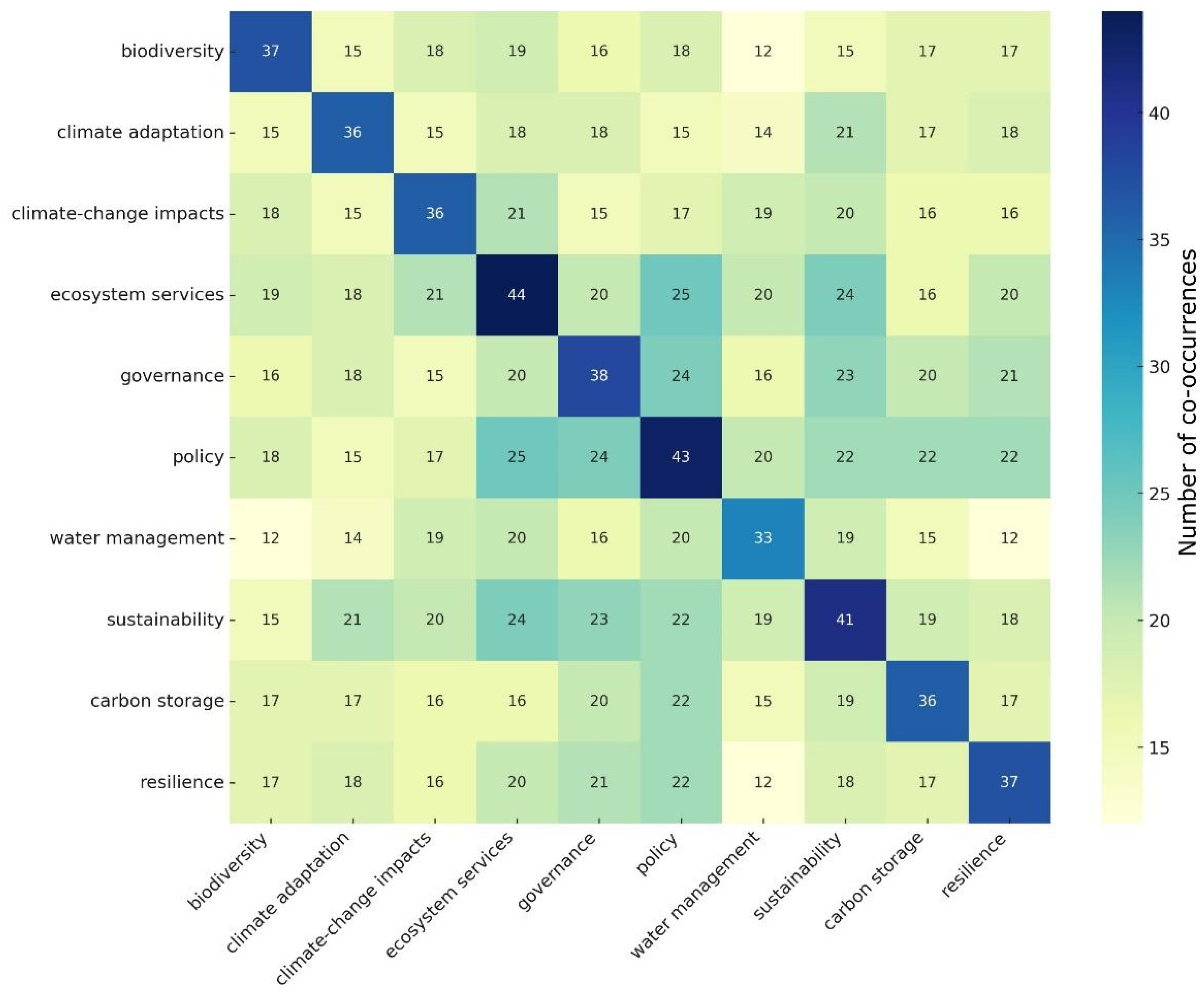

Figure 4 presents a heatmap to show the co-occurrence of environmental keywords across the 80 analyzed publications. The rows and columns of the heatmap represent the keywords identified (e.g., biodiversity, climate adaptation, policy, resilience). The blue color’s intensity reflects how often a pair of keywords are found together in the same publication. The strongest associations, i.e., the most frequent combinations, are represented by the darkest blue shades. The diagonal cells indicate the total occurrences of each keyword in the dataset. Each cell shows how many times the two keywords appeared together. This visualization signals adjacent thematic clusters, i.e., not only tightly interrelated concepts such as resilience and governance but also uncovered areas of (potential) research where relationships between the themes are weaker or even nonexistent. Hence, the heatmap offers a more explicit presentation of the dwell areas in both policy and academic debates of climate change, providing a superior grasp of how the issue of the interconnected nature of climate change is being solved in the literature.

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence heatmap illustrating the frequency with which pairs of environmental governance and climate-related terms appear together in the analyzed publications.

A strong association between biodiversity and climate adaptation is noticed, which points to a very essential feature in the realm of the environment. This indicates that there is an increasing realization of the significant role of biodiversity in terms of climate change adaptation through the discussion of the fact that green ecosystems [76] provide various essential services that positively impact the resilience of human beings [72]. Similarly, the strong linkage between resilience and environmental governance points out the focus on the stability of the environment and society in the long run [85]. Clearly, there exists a clear correlation between sustainability and the necessity of fostering resilience; without resilience, sustainability remains an elusive aspiration, particularly in the face of significant environmental challenges. The text also throws some light on the significance of these areas in the environmental sector and warns against the negative impact of the environmental issues that remain unresolved.

Having a look at the heatmap, it is clearly seen that there is a moderate co-occurrence between policy and the words, such as climate adaptation and ecosystem services. Therefore, policy frameworks are often pointed out together with these environmental challenges, thus indicating that governing policy is crucial in the encouragement of cross-border environmental cooperation. Indeed, through the introduction of efficient policy, the goals concerning the environment are the means of actual performance according to which the expected results are possible to determine.

Network and Density Visualizations

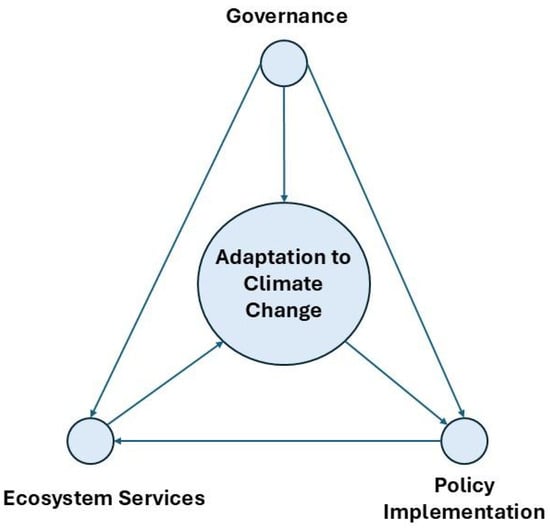

The network visualizations, which focus on networks created and the density of the data from the semantic analyses, provide more detailed information about the trends and their linked themes as well as the weight of the topics discussed in the research. A co-occurrence analysis is defined as a quantitative method for researchers to graph relationships by counting the number of times they find specific keywords or concepts together in one textual unit, e.g., a sentence or a paragraph. This analysis depicts the link between concepts; the more times terms appear together, the closer their relationship is considered to be. It can be seen from the network analysis (Figure 5) that “adaptation to climate change” is the main point, and hence it is the three main drivers of the network, i.e., “ecosystem services”, “governance”, and “policy implementation”, all of which are interrelated and, from the points of the key aspects in the transnational environmental cooperation, are influenced by “adaptation to climate change”. The presence of ecosystem services, governance, and policy implementation as major, closely linked nodes in the research network points at their pivotal role. Moreover, this also suggests that the beginning of any clean, transnational environmental partnership in Europe would have to be based on strong, joint work in these three areas. Turning to density maps, they indeed reflect the results and also show more clearly that climate adaptation, biodiversity, and governance are the bright spots where the focus is in the discussion about transnational cooperation. The visualizations indicate that these issues are the most salient ones in research and policy communication about cross-border environmental cooperation.

Figure 5.

Network analysis of keyword co-occurrence, highlighting the central role of climate change adaptation and its strong connections with ecosystem services, governance, and policy implementation.

Information inter alia from the semantic analysis included the interconnection of concepts and the deepness of the research in those areas. This explained the thematic grouping by LDA very well. The keyword co-occurrence network (Figure 6) was instrumental in identifying “adaptation to climate change” as the most central and relevant topic of the discourse.

Figure 6.

Keyword co-occurrence network (VOSviewer) depicting the main thematic clusters within the literature and the strength of associations between key concepts related to transnational environmental cooperation.

This central theme is depicted as being strongly linked to the three main network drivers: “ecosystem services,” “governance,” and “policy implementation,” thus pointing to the fundamental interdependence of these factors as the basis for the success of transnational environmental cooperation. The fact that these concepts appear as major, closely linked nodes in the research network implies that any solid partnership in Europe will have to be grounded in going forward with strong, joint work in these three areas.

5. Discussion

The bibliographic survey delivers a wide-angle sketch of the existing research that focuses on cross-border cooperation with an emphasis on environmental issues in the European Union and identifies the main trends and topics addressed. The results also align with, and disseminate, the findings of other, more specific, academic works in the sphere of the environmental policy and governance of the EU. The keyword analysis mentioned in the paper shows a particularly strong link between “biodiversity” and “climate adaptation,” which is also reflected in the literature that is discussed in the paper, where it is suggested that these two environmental challenges should be seen as one and that a holistic approach is the only viable option [58]. It is quite common to refer to this relationship as “nature-based solutions,” a term that is very much the focus of the publications of Tosun and Langlais, who are strong advocates for the use of services provided by nature to both take away carbon gases from the atmosphere and protect biodiversity [37]. Such a move is beyond the mere acting against a single pollutant and thus manifests a new paradigm in which environmental problems become interconnected systemic issues [86,87,88]. This viewpoint is, indeed, very much present in the recent literature, e.g., in works by the European Environment Agency, which continually emphasize the requirement for the implementation of policies which could be close to reality by accounting for the complex interactions between climate change, biodiversity loss, and other environmental pressures [89,90,91,92].

The strong link between “resilience” and “environmental governance” in the results has been one of the major features that defines the new paradigm in discussions that have been shifted from mere regulation to forming adaptive and solid systems. Such a line of thought is also consistent with the overall sustainability debate that shows the growing acknowledgement of the need for human and natural systems to adjust to unforeseen changes [38,42]. Phenomena like “planetary boundaries” [73] and “safe operating spaces” [57], which many examples refer to, such as the studies of Steffen et al., explicitly, are the means to highlight the role of stable governance in the revival of Earth’s self-regulating capacity. When it comes to the organizational level, the study results reveal that cooperation is gaining momentum in the direction of achieving governance that would support ecosystem and community resilience at both local and regional levels. The latter factor is indeed a prerequisite for being able to solve cross-border issues [67].

The gist of this is well in accord with the “Earth System Governance” model that Biermann and Kim put forth, which emphasizes the need for governance structures being not only equipped to handle complicated situations but also being able to encourage the system’s resilience in face of global-scale changes [26,90].

One of the accounts is climate change, which is an undeniable theme appearing in all kinds of environmental papers reviewed by the authors and is well-established in the European environmental policy discourse [50]. The European Commission and scholars such as Pahl-Wostl have left no stone unturned in depicting the process of climate change causing the water cycle to be disrupted and thus requiring cross-border collaboration for shared water bodies [23,24]. Societal issues have emerged simultaneously in the literature in the climate change and water areas, manifested as governance, societal and political understanding, changes, and knowledge [51]. Terminology changes from “policy” to phrases such as “climate adaptation” and “ecosystem services” highlight the importance of governance of the green agenda. Such a result corroborates the argument of academics like Jordan and Huitema, who maintain that a successful environmental policy depends, firstly, on the ability of the institution to perform its function and, secondly, on the engagement of the stakeholders in the design and conduct of the policy [38].

Thematic clusters discovered by LDA modeling shed light on some specific aspects of the topic that were not directly mentioned in the reviews. For example, the cluster “Urban Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation” reflects the trend of research on urban environmental governance [32,40]. This idea of cities being the primary locations of climate activities is the main point here, as was indicated in the publications that dealt with the issue of how cities can implement innovative, small-scale climate solutions as a result of being laboratories [32,58]. The mutual existence of “Policy and Management of Climate Change” and “Climate Change Adaptation and Vulnerability Frameworks” themes gives an indication that authors such as Happaerts and Van den Broeck [86] were talking about the same thing when they mentioned both mitigation and adaptation strategies. Reading through the “Land Use, Urban Heat, and Biodiversity Impacts” gestalt, one can see that these kinds of environmental issues are closely linked, which is a recurring topic in both the “European Green Deal” and other similar policy documents [19,72]. Moreover, “Climate Change Management, Future Projections, and Assessment” stays in line with the idea of monitoring at the international level and the role played by organizations such as the IPCC and the European Environment Agency in this regard [10,93].

The climate change adaptation theme seemed to be the central point of both the network and density visualizations [49]. These strong links between “adaptation to climate change,” “ecosystem services,” “governance,” and “policy implementation” give a good indication of the polycentric and multi-level nature of the environmental governance model that is currently very popular among researchers in the field [38,87]. Successful adaptation, as is found in the research here, is not a single event but a complex combination of realizing climate effects [74,75,76,77], applying ecosystem services for resilience, building strong governance systems, and pushing forward effective policies. This is in line with the claims of multi-sectoral and multi-level collaboration, which is the main theme throughout the broad literature [86,87].

Despite these valuable insights, this review, along with many others, has its limitations and reveals gaps in the literature. The research carried out here affirms the relevance of policy frameworks [52]; however, it does not go into the detail of the specific efficacy of individual policy instruments [82,83,84]. The focus of future investigations should be on finding ways to practically implement policies that will be effective in different sectors and regions, and they should also be tested in real-life scenarios [88,89,90,91]. Specifically, a subsequent logical and indispensable move in research would be to update the grey data on European Union laws, plans, and regulations (for instance, the Zero Pollution Action Plan, the National Emission Reduction Commitments, and the Ambient Air Quality Directive). These studies should evaluate the degree of cooperation among European nations, their effectiveness in addressing environmental issues, and the overall level of environmental governance. Authors should consider applying content analysis and metrics to evaluate the appropriateness and efficacy of environmental legislative tools at the regional level, including long-term cooperation efforts such as the agreements on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollutants dating back to the 1970s.

Moreover, the review summarizes that the social and political dimensions are less emphasized points in the literature on transnational environmental cooperation [39,54]. Topics such as equity, fairness, and stakeholder participation, which are basic elements for cooperation to be sustainable [47], need more concentrated research to find out how they affect decision-making and the distribution of benefits and costs [92,93,94,95]. The question of the role of non-state actors, such as NGOs and businesses, in transnational environmental cooperation is also a matter of further deepening of understanding [55,95,96,97,98].

Ultimately, this review, although focusing on Europe, is still a good reminder of the global interconnectedness of environmental problems [30]. Scholars may want to consider the implications of Europe’s position in world environmental governance in addition to its role in international agreements [17,44,70].

To respond to the research questions raised in the study, the following conclusions are presented below.

The main environmental challenges in Europe that are the best subjects for transnational cooperation are climate change, loss of biodiversity, and air, water, and sea pollution. Regulatory and governance frameworks are key factors in either enabling or obstructing cooperation, with successful policies and institutions being the stepping stones to success. Experience and learning together offer the most efficient way of reaching the goal along the path of existing examples of best practices, which require worthwhile targets, proper zip codes, leadership, and change management. The collaboration type can be fundamentally influenced by political, economic, and cultural determinants, and the problems facing cooperation are found in the areas of equity, power, and priorities due to differences. The paper also features suggestions for enhancing international cooperation, which consist of the reinforcement of policy frameworks, the encouragement of cross-sector alliances, the improvement of public participation, and the resolution of equity and power issues.

6. Conclusions

This paper is a detailed summary of transnational environmental cooperation in Europe, outlining important topics, patterns, and research defects. The study highlights environmental problems, the role of policy conditions, and the necessity of comprehensive and cooperation. The thorough and integrated use of LDA modeling and semantic analysis showed that, among the research pieces on transnational environmental cooperation in Europe, topics like adaptation to climate change, biodiversity protection, and the effective governance of natural resources make up the most dominant and highly interconnected thematic core. This discovery emphasizes how these three particular areas are not only most visible in academic discourse and policy formulation but also indicate that they serve as the core framework for comprehending the implementation of environmental challenges across borders.

The research also identifies different areas for further study. It is more investigation that will confirm or dismiss the effectiveness of the instruments given, besides the social and political, and at the social and political implementation and monitoring stages, wider environmental cooperation is essential. Addressing these gaps will be important for promoting our understanding of transnational environmental cooperation and, of course, for the design of more effective strategies of environmental sustainability in Europe. Longitudinal studies should be the main focus of future research to evaluate the lasting effects of cooperative frameworks. Comparative studies between different areas might also be useful in identifying the local conditions that support or limit environmental partnerships.

In conclusion, the study has illustrated that effective cross-border environmental collaboration in Europe is an absolute necessity if the region is to solve the most urgent issues like climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. The research has thus empowered people to be convinced that governance structures that are robust, clear policy frameworks, and masse, inclusive, and adaptive management approaches are the most important factors to get past institutional and political barriers that are still preventing cooperation. Success is contingent upon being able to reach an agreement on the diverse interests of stakeholders, building trust through joint learning and open leadership, and going further to ensure that participation is fair to all sectors and regions. This article points measures on the basis of research evidence that could potentially be more effective in enhancing the capacity of cooperative mechanisms such as regulating coherence, multi-level partnerships, and embedding continuous monitoring and evaluation. The implementation of such strategies could pave the way for transnational cooperation to break through existing blocks and eventually lead to the creation of a much more resilient and environmentally sustainable future, which would, in turn, support the long-term ecological and social well-being of Europe. The practical implications of these findings highlight the necessity for policymakers and practitioners to formulate governance models that are capable of adapting to changing conditions, encourage stakeholder participation, and also set up implementation as well as monitoring systems that are effective for the achievement of sustainable results. On a theoretical level, the research sheds light on the role of power relations, institutional configuration, and interdisciplinary methodologies in influencing transnational collaboration in the process of governance paradigm extension.

Future research should really aim at conducting longitudinal studies to evaluate the lasting effects and viability of cooperative models, together with comparative surveys in different regional places to reveal local elements that are either supportive or obstructive to cooperation. Furthermore, additional probing into the social and political forces that are driving equity and power relations in cross-border ventures will become obligatory going forward. These explorations will not only enrich the knowledge of how to develop governance models that exhibit adaptive features but also will enable them to respond effectively to the changing environmental and social problems. By pushing forward these research areas in conjunction with the utilization of practical strategies, transnational collaboration will be able to overcome the current deadlocks and move towards more resilient and sustainable environmental outcomes, which will then, in turn, be able to contribute to the long-term ecological and social well-being of Europe.

Author Contributions

M.W.: conceptualization, project administration, visualization, writing—review and editing; R.A.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, supervision; M.F.: writing—review and editing, validation, supervision; V.R.: writing—review and editing, visualization; J.V.: data curation, conceptualization, visualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Nr. | Title | Year of Publication |

| 1 | The role of regions in the European environmental governance system | 2020 |

| 2 | Climate policy integration in the European Union | 2021 |

| 3 | Integrated water management in the EU: Lessons from the Danube | 2020 |

| 4 | The European Green Deal and its implementation | 2021 |

| 5 | Air quality in Europe—2019 report | 2019 |

| 6 | Multilateral environmental agreements in Europe | 2019 |

| 7 | AR6 Climate Change Report | 2021 |

| 8 | The role of the EU’s biodiversity strategy in addressing biodiversity loss | 2020 |

| 9 | Transboundary air pollution in Europe | 2021 |

| 10 | Biodiversity loss in Europe: Causes and implications | 2020 |

| 11 | Collaborative water governance in Europe | 2020 |

| 12 | Transboundary environmental governance in the EU | 2020 |

| 13 | Planetary boundaries in Europe | 2021 |

| 14 | Governing the European Green Deal | 2022 |

| 15 | The Mediterranean Sea: Plastic pollution and policy solutions | 2020 |

| 16 | The transnational regime complex for climate change | 2012 |

| 17 | Implementing transboundary environmental governance | 2020 |

| 18 | The road to Paris: Contending climate governance discourses | 2016 |

| 19 | Navigating regional environmental governance | 2012 |

| 20 | Rethinking transnational environmental governance | 2021 |

| 21 | Climate politics, metaphors, and the fractal carbon trap | 2019 |

| 22 | Architectures of earth system governance | 2020 |

| 23 | Governance without a state: Can it work? | 2010 |

| 24 | Transnational environmental governance | 2012 |

| 25 | Social movements, the climate crisis, and new forms of governance | 2021 |

| 26 | Environmental policy and politics in the European Union | 2016 |

| 27 | The politics of the earth: Environmental discourses | 2013 |

| 28 | The European Green Deal: A model for global climate leadership | 2019 |

| 29 | The European environment—State and outlook 2020 | 2019 |

| 30 | The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics | 2016 |

| 31 | International environmental agreements and their role in European policies | 2012 |

| 32 | The planetary boundaries framework and global environmental governance | 2016 |

| 33 | De facto governance: Climate engineering | 2019 |

| 34 | Climate change, biodiversity, and sustainable development | 2018 |

| 35 | Sub- and non-state climate action | 2018 |

| 36 | Transnational climate governance | 2021 |

| 37 | Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services | 2019 |

| 38 | Sixth Assessment Report | 2021 |

| 39 | Policy innovation in a changing climate | 2014 |

| 40 | Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action | 2018 |

| 41 | Entry into force and then what? The Paris Agreement | 2017 |

| 42 | Climate adaptation governance: Policy and practice in the EU strategy | 2019 |

| 43 | The emergent network structure of the multilateral environmental agreement system | 2013 |

| 44 | Climate tipping points—Too risky to bet against | 2019 |

| 45 | Collaborative approaches in environmental governance | 2022 |

| 46 | Biodiversity and transnational governance: An evolving agenda | 2020 |

| 47 | Explaining goal achievement in international negotiations: The EU and the Paris Agreement | 2017 |

| 48 | Transnational multistakeholder partnerships for sustainable development | 2016 |

| 49 | Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet | 2015 |

| 50 | The global environmental outlook 6 | 2022 |

| 51 | The state of the global climate | 2021 |

| 52 | European Union climate governance and multilevel policymaking | 2019 |

| 53 | Governing complex systems: Social capital for the anthropocene | 2018 |

| 54 | A theory of global governance: Authority, legitimacy, and contestation | 2018 |

| 55 | Biodiversity Loss in Europe: A Policy-Based Response | 2015 |

| 56 | Integrating Climate Adaptation into Urban Planning Strategies | 2025 |

| 57 | The Role of Governance in Sustainable Water Management | 2024 |

| 58 | Ecosystem Services in Agricultural Landscapes: A European Perspective | 2018 |

| 59 | Air Quality and Health: Emerging Policy Challenges | 2017 |

| 60 | Carbon Storage Solutions in the EU Forestry Sector | 2017 |

| 61 | Mainstreaming Resilience into Regional Environmental Policy | 2016 |

| 62 | Nature-Based Solutions for Coastal Climate Adaptation | 2010 |

| 63 | Sustainability Indicators for European Environmental Reporting | 2017 |

| 64 | Renewable Energy Integration and Biodiversity Trade-offs | 2022 |

| 65 | Transboundary Water Management and Governance Innovation | 2011 |

| 66 | Green Infrastructure and Urban Heat Mitigation in Europe | 2012 |

| 67 | The Future of EU Climate Law: Pathways for Policy Integration | 2020 |

| 68 | Adaptive Governance in the Face of Climate Extremes | 2014 |

| 69 | Cross-Sectoral Approaches to Climate Resilience | 2011 |

| 70 | Innovative Financing Models for Ecosystem Restoration | 2018 |

| 71 | Policy Gaps in the Implementation of the European Green Deal | 2024 |

| 72 | Monitoring Biodiversity under the EU 2030 Strategy | 2023 |

| 73 | Integrating Traditional Knowledge into Climate Policy Frameworks | 2013 |

| 74 | Trade-offs between Land Use and Carbon Sequestration Goals | 2020 |

| 75 | Sustainable Land Management under Drought Pressure | 2024 |

| 76 | Resilience Thinking in Flood Risk Governance | 2016 |

| 77 | The Role of Citizen Science in Environmental Monitoring | 2017 |

| 78 | Multi-Level Governance for Biodiversity Conservation | 2011 |

| 79 | Climate-Resilient Agriculture: Policies and Practice | 2011 |

| 80 | Evaluating the Effectiveness of Ecosystem-Based Adaptation | 2011 |

References

- Schreurs, M.A. Environmental Politics in Japan, Germany, and the United States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cashore, B.; Auld, G.; Newsom, D. Governing Through Markets: Forest Certification and the Emergence of Non-State Authority; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, J.; Lang, A. Governing the European Green Deal: Multilevel Governance and Policy Coherence. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 133, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.; Oberthür, S.; Van Schaik, L. Climate Policy Integration in the European Union: Trends and Drivers. Environ. Polit. 2021, 30, 715–737. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, P.; Dempsey, J. Social Impacts of Protected Areas: A Review with Implications for Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Happaerts, S.; Van Den Brande, K.; Bruyninckx, H. Multilateral Environmental Agreements in Europe: Balancing Between Regional Integration and Global Commitments. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2019, 19, 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, P.M. When Knowledge Is Power: Three Models of Change in International Environmental Institutions. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2015, 1, 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, D.; Parks, L. Social Movements, the Climate Crisis, and New Forms of Governance. Environ. Polit. 2021, 30, 1123–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Policy Innovation in a Changing Climate: Sources, Patterns, and Effects. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. AR6 Climate Change Report; IPCC Publications: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leip, A.; Weiss, F.; Lesschen, J.P.; Westhoek, H. Impacts of European Livestock Production: Nitrogen, Sulphur, Phosphorus and Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land-Use, Water Eutrophication and Biodiversity; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Deng, Z.; Lei, R.; Davis, S.J.; Feng, S.; Zheng, B.; Cui, D.; Dou, X.; Zhu, B.; et al. Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conca, K. Governing Water: Contentious Transnational Politics and Global Institution Building; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Air Quality in Europe—2019 Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Langlais, R. (Eds.) Handbook on Climate Change and (Trans)Boundary Water Management; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Hardesty, B.D.; van Franeker, J.A.; Eriksen, M.; Siegel, D.; Galgani, F.; Law, K.L. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Global Environmental Outlook 6; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Essop, B. The Capitalist State: Towards a Critical Political Economy; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal and Its Implementation; EU Publications: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs, M.A. Transboundary Environmental Governance in the EU: Learning from Successes and Challenges. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; et al. Planetary Boundaries in Europe: Aligning Policy with Global Limits. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd7671. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González, M. International Environmental Agreements and Their Role in European Policies. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2012, 14, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Integrated Water Management in the EU: Lessons from the Danube; EU Publications: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Collaborative Water Governance in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Lenschow, A. Environmental Policy Integration: Greening Sectoral Policies in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Betsill, M.M.; Gupta, J.; Kanie, N.; Lebel, L.; Liverman, D.; Schroeder, H.; Siebenhüner, B. Earth System Governance: People, Places, and the Planet; Science and Implementation Plan of the Earth System Governance Project; IHDP: Bonn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, T.; Held, D.; Young, K.; Beeson, M. Gridlock: Why Global Cooperation Is Failing When We Need It Most; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Falkner, R. The Paris Agreement and the New Logic of International Climate Politics. Int. Aff. 2016, 92, 1107–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagers, S.C.; Matti, S.; Vasileiadou, E. Culture and the Environment: Politics, Power and Participation. Environ. Polit. 2011, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Balsiger, J.; Prys-Hansen, M. The Role of Regions in the European Environmental Governance System: Policy Innovation and Multi-Level Cooperation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020, 30, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressers, J.T.A.; O’Toole, L.J., Jr. (Eds.) Policy Design and the Challenges of Implementation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Urban Climate Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. Governance Without a State: Can It Work? Regul. Gov. 2010, 4, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelle, C.; Oberthür, S. (Eds.) Environmental Policy Integration: Greening Sectoral Policies in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Delreux, T.; Happaerts, S. Environmental Policy and Politics in the European Union; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Jordan, A. Transnational Environmental Governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, T.; Roger, C.; Stripple, J. Transnational Climate Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D.; van Asselt, H.; Forster, J. (Eds.) Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. Cooperation and Discord in Global Climate Policy. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Castán Broto, V.; Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. Governing Complex Systems: Social Capital for the Anthropocene; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zürn, M.A. Theory of Global Governance: Authority, Legitimacy, and Contestation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S.; Hoffmann, M. Climate Politics, Metaphors, and the Fractal Carbon Trap. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The State of the Global Climate; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Blackstock, K.; Ingram, J. Implementing Transboundary Environmental Governance: Lessons from Collaborative Catchment Management. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020, 30, 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; et al. Climate Change, Biodiversity, and Sustainable Development: Harnessing Synergies and Avoiding Trade-Offs. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Galaz, V.; et al. The Planetary Boundaries Framework and Global Environmental Governance. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Kim, R.E. Global Governance for the Environment; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lenton, T.M.; Rockström, J.; Gaffney, O.; Rahmstorf, S.; Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Climate Tipping Points—Too Risky to Bet Against. Nature 2019, 575, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsiger, J.; VanDeveer, S.D. Navigating Regional Environmental Governance. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2012, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.I.; Groff, M.; Tamás, P.A.; Dahl, A.L.; Harder, M.; Hassall, G. Entry into Force and Then What? The Paris Agreement and State Accountability. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 830–836. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, S.; Gehring, T. (Eds.) Conceptual Challenges to Multilateralism; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, R.E. The Emergent Network Structure of the Multilateral Environmental Agreement System. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgera, E. Biodiversity and Transnational Governance: An Evolving Agenda. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2020, 9, 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Transnational Climate Governance. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2009, 9, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, T.; Chan, S.; Hsu, A.; Clapper, A.; Elliott, C.; Faria, P.; Kuramochi, T.; McDaniel, S.; Morgado, M.; Roelfsema, M.; et al. Sub- and Non-State Climate Action: A Framework to Assess Progress, Implementation, and Impact. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, L. Collaborative Approaches in Environmental Governance. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 35, 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Möller, I. De Facto Governance: How Authoritative Assessments Construct Climate Engineering as an Object of Governance. Environ. Polit. 2019, 28, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, M.; Stone, D. Rethinking Transnational Environmental Governance. Environ. Polit. 2021, 30, 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, T.; Jørgensen, K.E.; Wiener, A. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of European Union Politics; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wurzel, R.K.; Connelly, J.; Liefferink, D. European Union Climate Governance and Multilevel Policymaking; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Knill, C.; Tosun, J. (Eds.) Policy-Making in the European Union; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, G.M.; Barrett, M.; Burgess, N.D.; Cornell, S.E.; Freeman, R.; Grooten, M.; Purvis, A. Planetary Boundaries: Assessing Evidence for Approaching Critical Thresholds in Global Environmental Systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 1869–1882. [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo, E.C.H.; et al. Climate Adaptation Governance: Policy and Practice in the EU Strategy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lenschow, A. (Ed.) Environmental Policy: Europeanization and Multi-Level Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, S.; Groen, L. Explaining Goal Achievement in International Negotiations: The EU and the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, K.; Lövbrand, E. The Road to Paris: Contending Climate Governance Discourses in the Post-Copenhagen Era. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P.; et al. The European Green Deal: A Model for Global Climate Leadership. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefferink, D. Environmental Politics and Policy: Theories and Evidence; Longman: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pareto, V. Manuale di Economia Politica con una Introduzione alla Scienza Sociale; Società Editrice Libraria: Milano, Italy, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldor, N. Welfare Propositions of Economics and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility. Econ. J. 1939, 49, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P.J. Interpersonal comparisons of utility: Why and how they are and should be made. In Handbook of Utility Theory; Barbera, S., Hammond, P.J., Seidl, C., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 207–259. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, G.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Chen, H. How well do authors’ keywords and Keywords Plus represent the content of an article? J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Borrás, S. Governing Green Transitions: Global Innovations and European Experiences; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Happaerts, S.; Van den Broeck, P. (Eds.) The Multi-Level Governance of Climate Change: Perspectives on the EU and Its Member States; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weale, A.; Pridham, G.; Williams, A.; Porter, M. Environmental Governance in Europe: An Ever Closer Ecological Union? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational Multistakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development. Glob. Gov. 2016, 22, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, J. Environmental Policy in Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Kim, R.E. Architectures of Earth System Governance: Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 45, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). The European Environment—State and Outlook 2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Sixth Assessment Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zelli, F.; van Asselt, H. (Eds.) The Emergence of Climate Change Regimes: Between International Law and Regional Initiatives; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Balsiger, J.; Prys-Hansen, P. Environmental Policy and Politics; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eckersley, R. The Green State: Rethinking Democracy and Sovereignty; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, Á.; Elliott, M.; Carstensen, J.; Heiskanen, A.S.; van de Bund, W. Marine Management—Towards an Integrated Implementation of the European Marine Strategy Framework and Water Framework Directives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 2159–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G. (Ed.) Area-Based Conservation: Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. The Water Governance Jigsaw: Connecting Societal Problems with Water Resources Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.