Abstract

Water erosion is a major driver of soil degradation in arid and semi-arid regions, where the lack of vegetative cover and intense rainfall accelerate erosion processes. Field experiments were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of stone walls (SW) as a soil conservation practice in reducing soil erosion using the universal soil loss equation. Furthermore, the support practice factor (P) was estimated via integrating computational measurements of changes in A horizon thickness with slope profiles. Six sites with varying slope gradients (8%, 10%, 15%, and 25%) implementing SW were compared to neighboring sites lacking this practice in the northeastern parts of Jordan. SW reduced average annual soil loss by 83%, lowering the average annual erosion rate from 58 t.ha−1.yr−1 (severe risk) to 10 t.ha−1.yr−1 (slight risk). The implementation of SW stabilized the thickness of the A horizon and organic matter contents across different slope gradients. In contrast, the absence of SW led to greater soil displacement and accumulation of organic matter at the lower slopes, indicating higher erosion risks. The average estimated P factor was 0.35. These findings underscore the effectiveness of conservation practices in controlling soil erosion, enhancing soil quality, and promoting sustainable land use in arid and semi-arid environments. Wider adoption of such measures can significantly contribute to combating soil degradation and improving agricultural productivity in similar regions worldwide.

1. Introduction

Water-induced soil erosion is a serious widespread issue accounting for 85% of global soil degradation [1]. Annual costs related to erosion impact the global economy by billions of dollars and risk crop losses in vulnerable regions [2,3]. This type of erosion poses a significant ecological threat to soils particularly in semi-arid and arid regions [4,5]. While a complete prevention of soil erosion is unfeasible, it can be minimized to acceptable levels through effective soil conservation strategies [6,7]. The extent of soil erosion is primarily influenced by factors such as soil erodibility, rainfall erosivity, topography, vegetation cover, and conservation practices [8].

In arid and semi-arid areas, the erosion process is exacerbated by sporadic heavy rainfall [9,10], low native plant density [11,12], and inadequate land management practices [13,14]. Moreover, projected climate change is expected to increase rainfall variability and intensity in these zones, further escalating soil erosion risk [15].

Human activities including farming, logging, and overgrazing further intensify soil erosion, particularly on poorly vegetated soils [16]. This erosion has a detrimental impact on soil quality, reducing its depth and water-holding capacity while altering its physical, chemical, and biological properties [17,18].

In sloping areas, water erosion further degrades soil quality by displacing soil organic matter, nutrients, and particles from the A horizon down the slope [19,20]. For instance, soil erosion was triggered by extensive cultivation leads to a thinner A horizon and less fertile soil [21]. Moreover, in these regions, soil thickness and rock fragment cover are more influential than other soil properties in determining hydrological and erosion behaviors [22]. These impacts pose substantial challenges to sustainable agriculture and ecosystem stability in arid and semi-arid landscapes.

Given the challenges associated with soil erosion, effective assessment is crucial for implementing targeted soil conservation practices (SCPs). The Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) is a widely used tool for evaluating regional-scale annual soil loss due to water erosion. Globally, various SCPs, such as contour stone walls, terracing, contour plowing, and cover cropping, have been implemented to conserve soil by reducing runoff, improving soil fertility, and enhancing soil quality [23]. Among various SCPs, contour stone walls have regional significance in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern agriculture, offering effective erosion control through slope stabilization and organic matter retention [24,25].

Stone walls have been used for a long time to manage water erosion in various Mediterranean countries, stabilizing the soil surface layer (A horizon), increasing organic matter, and promoting the accumulation of crop residues [21,25]. Stone walls are effective practice in reducing soil water erosion. It was reported that stone bunds reduced soil water erosion by 68% [26]. On the European scale, the risk of soil erosion was reduced by 3% using stone walls [27]. Modeling the impact of support practices (P-factor) on soil erosion reduction in the European Union revealed average P-factor estimated at 0.9702. This factor accounted for contour farming, stone walls and grass margins, with grass margins having the largest impact (57% of the total erosion risk reduction) followed by stone walls (38%) [28]. However, these stone walls must be maintained and repaired each year by the local populations [29]. In northern Jordan, particularly in the Wadi Ziqlab catchment area, various soil conservation techniques have been implemented over the years, with stone walls being the most common method. The area, characterized by highly variable elevations and limited rainfall, faces significant surface soil erosion due to its low native plant density and intense storms. In addition to stone walls, small, scattered areas occasionally feature stone tree basins, terraces, contour lines, gradoni, and wadi control measures. Farming practices, including the construction of stone walls, plowing, removal of surface rocks, and incorporation of plant residues into the soil, have significantly contributed to reducing soil erosion and increasing the thickness of the A horizon [30]. However, despite their widespread use and importance, previous studies have not quantified stone wall effectiveness in relation to slope gradients using integrated empirical and computational approaches, revealing a significant knowledge gap.

Although numerous studies have explored the effectiveness of SCPs like stone walls, none had quantified their impact across varying slope gradients using empirical measurements of soil horizon thickness and integrated computational models. This study addresses this gap by providing a comprehensive assessment of stone wall conservation techniques and their effect on soil quality and erosion control in sloping, arid regions. This novel methodology combining empirical soil thickness profiles with USLE modeling contributes new insights for improved soil conservation planning and sustainable land use in arid environments.

This study aims to evaluate potential water erosion in Wadi Ziqlab, assess the effectiveness of stone walls as a SCPs, and estimate the support practice factor (P) using the USLE model. The research compares two sites: one employing stone-walls (SW) as a SCPs and one without stone walls (No-SW), using an innovative approach that integrates computational soil loss calculations with empirical measurements of soil thickness and slope profiles. This novel methodology for estimating the support practice factor (P) offers a fresh perspective that has not been previously applied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

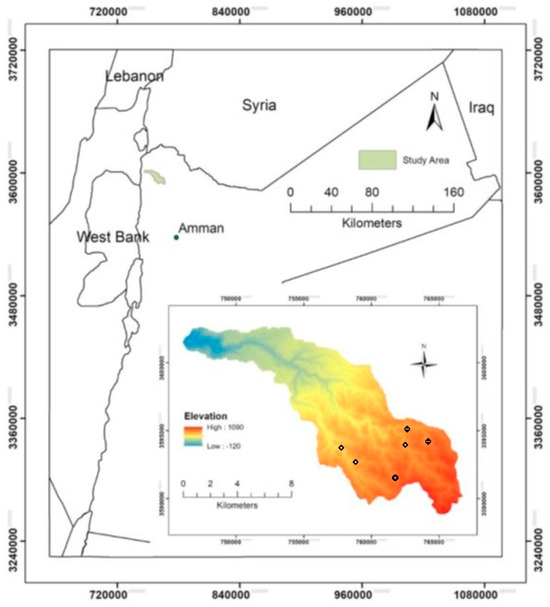

The study was carried out in the Wadi Ziqlab catchment area, located between latitudes 32° 23″ to 32° 34″ North and longitudes 35° 33″ to 35° 50″ East, extending from the northern highlands to the eastern mountains bordering the Jordan Valley (Figure 1). The region features highly variable elevations, ranging from 200 m below sea level in the Jordan Valley to over 1075 m above sea level on the southeast side. The area experiences limited rainfall during wet, cold winters and long, hot, dry summers, with mean annual temperatures averaging between 14.3 °C and 17.9 °C. Most rainfall occurs between November and March, totaling 450 to 550 mm annually (average 490 mm). Accordingly, the climate is classified as semi-arid to lower dry subhumid (Mediterranean sub-humid).

Figure 1.

Location of study area and sites.

The combination of low native plant density and frequent high-intensity storms makes surface soil erosion a significant concern. Land use includes bare soil, bare rock, olive, grape, pomegranate orchards, open forests, and wheat fields, often mixed within the same area. Conservation practices, such as stone walls and plowing perpendicular to the longest field axis, are commonly employed to reduce runoff and soil erosion. The soils are mainly derived from limestone parent material and are classified as Haploxerepts (Typic, Lithic, Chromic, and Vertic subgroups) and Xerorthents (Typic and Lithic subgroups). They are slightly to highly calcareous, depending on rainfall and topographic position [31].

Both stone-wall (SW) and non–stone-wall (No-SW) sites were situated within similar land-use systems dominated by olive-tree cover. This ensured comparable vegetation and management conditions, allowing the analysis to focus primarily on the effects of slope gradient and stone-wall conservation. The SW plots represent areas where the government implemented soil and water conservation measures about 45 years ago; these structures were typically limited to relatively small portions of the cultivated terrain. During the initial site assessment, around 50 potential locations representing diverse land-cover types and management histories were evaluated. To minimize effects of vegetation, only those locations where both SW and No-SW plots shared the same cover (olive trees) were retained for detailed analysis. All plots were managed by local farmers following their regular agricultural practices, while researchers conducted field sampling without interfering with on-farm management.

2.2. Study Sites and Soil Sampling and Analysis

Four locations with varying slope gradients (8%, 10%, 15%, and 25%) were selected within the study area (catchment). In each location, two adjacent fields were chosen: one applying SW and a control field without SW. The selection was made based on the similarity of topographical features between the two fields (slope length (L), gradient (S), and land use). Slope length varied by location, ranging from 60–120 m, with an overall average of 82 m across all sites. Soil sampling was conducted at the beginning of the rainy season of 2017 to capture conditions prior to significant erosion events, ensuring consistency across sites. Composite samples were formed by mixing several subsamples collected randomly within each designated slope position. From each field, three composite surface soil samples (at the upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L) positions) were taken along a transect line. The depth of the A-horizon was determined by excavating a soil profile pit, visually identifying the horizon based on its darker color and higher organic content, and measuring from the soil surface to the transition point where the composition and color distinctly changed to the B-horizon. Soil profile pits were excavated to a minimum depth of 40 cm or until the B horizon was reached, using a standardized digging protocol. The A-horizon thickness was then recorded in centimeters. A total of 36 samples six per field were collected, air dried, stored in plastic jars, transferred to the lab and analyzed for texture by the hydrometer method [32] and total organic matter by the method [33]. Each soil sample analysis was performed in triplicate to ensure precision, and instruments were calibrated regularly against standard references. Samples were oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h prior to analysis to standardize moisture content. Slope gradients were measured in situ with a clinometer and verified using Global positioning system (GPS) altitudinal data to ensure accuracy within ±0.5%.

2.3. Estimation of Soil Loss

The USLE soil loss equation is expressed as follows:

where A represents the computed soil loss per unit area, measured in tons per hectare per year (t.ha−1.yr−1), based on the units chosen for the soil erodibility factor (K) and the time period for the rainfall-erosion factor (R), R is the rainfall and runoff factor, K is the soil erodibility factor, L is the slope-length factor, S is the slope-steepness factor, C is the cover management factor; and P is the support practice factor [8,34].

The R factor (rainfall erosivity factor) was estimated from the Iso-erodent map of North Jordan [35]. R values for the studied areas ranged from 264 to 430, with an average of 330 MJ.mm.ha−1.hr−1.year−1.

The K factor (soil erodibility factor) was calculated using the following equations:

a is soil organic matter (%), b (structure code = 2), c (permeability code = 6).

Variability in soil properties within sites was assessed and incorporated into the estimation of the K factor using mean and standard deviation values.

The LS factors (slope and steepness factors) were estimated using the following equations:

L is the slope-length factor (m), S is the slope-steepness factor (%), and θ is the slope angle. The crop management factor (C) was obtained from tables provided by [17,34]. The support practice factor (P) was estimated using three different approaches: (1) tables provided by Wischmeier [34], (2) using USLE without incorporating the P factor, and (3) soil thickness measurements across different slope positions (upper, middle, and lower) for two sites (one with SW and one without (No-SW), using the following approaches:

The second approach involved calculating soil loss for both sites (SW and No-SW) using Equation (1) and the following approach:

Since the equation is the same for both sites and does not include the P factor, the ratio of ASW to ANo-SW can be used to estimate the P factor:

The third approach involved measuring the thickness of the A horizon of the upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L) positions for both sites (SW and No-SW) and lengths of transects. This approach involved using the gradient (angle of the slope) derived from the change in thickness to length ratio reflecting the effectiveness of SW in reducing soil erosion using the following equation:

where Δ Thickness is the difference in horizon thickness (A horizon) between the upper and lower parts of the transect, and L is the length of the transect.

The second step involved relating the slope angle to erosion, typically higher angles denote higher erosion. The support practice factor (P) was then estimated by using the following standard formula.

By incorporating the slope angle and the length of transect yield the following equation:

where θSW and θNo-SW are the slope angles for SW and No-SW, respectively. This formula assumes the support practice (stone walls) reduces erosion by lowering the effective slope.

This approach assumes that reductions in effective slope gradient due to stone walls directly correspond to decreased erosion potential, a premise supported by field observations. While this method provides an innovative proxy for P estimation, it relies on accurate slope and soil thickness measurements and may be sensitive to spatial heterogeneity. Together, these methods provide a comprehensive framework combining empirical measurements and modeling to robustly assess the effectiveness of stone walls in mitigating erosion under varying slope conditions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Independent t-tests were performed to evaluate differences in the measured parameters between stone wall (SW) and no stone wall (No-SW) sites. Additionally, one-way ANOVA was used to assess variation among slope positions (upper, middle, lower) within each treatment, followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests for multiple comparisons. Data normality was initially assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When normality assumptions were not met, variables were log-transformed to satisfy test requirements. Statistical significance was set at . All analyses were conducted using Statistica version 9.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil Properties of Studied Sites

The studied soils were predominantly clay-textured, with clay contents of 68.2% in SW and 66.4% in No-SW sites, while sand contents averaged 17.3% and 17.8%, respectively (Table 1). Organic matter was slightly higher under SW conditions (1.2%) compared to No-SW (1.03%). Both sites exhibited similar structure and permeability codes (2 and 6), indicating moderately developed structure and slow permeability typical of fine-textured soils.

Table 1.

Average silt, clay, sand contents (%), organic matter content (%), and thickness of A horizon (cm) of studied sites.

These data indicate that stone wall (SW) sites exhibited improved soil quality characteristics related to erosion resistance, such as thicker topsoil and greater organic content, supporting their suitability for comparative erosion studies.

3.2. Soil Erosion

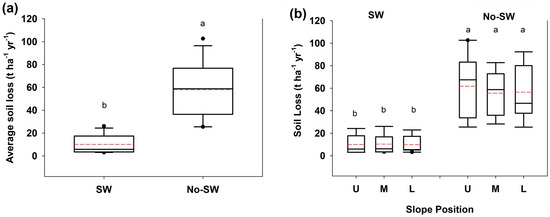

Figure 2a shows average annual soil Loss (t ha−1.yr−1) in sites applying stone walls (SW) and sites with no stone walls No-SW. This graph clearly illustrates that SW sites experience significantly (p < 0.002) reduced soil erosion as compared with areas with No-SW. Stone walls act as physical barriers that slow water flow, reducing the kinetic energy that leads to soil displacement [36]. Additionally, these barriers promote water infiltration into the soil rather than allowing surface runoff, further reducing soil loss [37,38]. This corresponds to an average reduction in annual soil loss of approximately 83%, indicating a strong protective effect of stone walls against erosion. In the Ethiopian highlands, SCPs such as stone walls and soil bunds reduced soil erosion by 81% in a watershed with deep soils and gentle slopes as compared to shallow and steep slopes [39]. Furthermore, SCPs improved soil organic content, and the effectiveness of these practices varied with soil depth [40]. Such practices-maintained soil productivity and minimized soil degradation [41]. Improvements in organic matter are likely due to reduced runoff and enhanced retention of organic residues, which contribute to soil fertility and structure. Figure 2b shows annual soil loss in sites applying stone walls (SW) and sites with no stone walls (No-SW) across different slope positions (upper, middle, lower). Within each treatment (SW and no-SW), soil loss did not differ significantly among slope positions (U, M, L). Pairwise comparisons confirmed that all No-SW positions (U, M, L) had significantly higher soil loss than any SW position, emphasizing that the presence of stone walls effectively minimized soil erosion regardless of slope position.

Figure 2.

(a) Average annual soil loss (±standard error) in sites with stone walls (SW) and without stone walls (No-SW). Statistical comparison between sites was performed using an independent t-test. (b) Average annual soil loss (±standard error) in SW and No-SW sites across slope positions: upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L). Differences among slope positions within each treatment were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. Letters denote statistically significant differences or lack within each site, with indicating no significant difference.

In SW sites, soil erosion was stabilized, whereas higher soil erosion in No-SW sites was observed at upper as compared to the lower positions. This pattern is consistent with natural movement of soil downhill due to gravity, where runoff water and soil accumulate as they move downslope. Lower slope positions tend to collect runoff and eroded material from the upper positions, which explains the higher soil loss in these areas [42]. Furthermore, slope position influences soil properties and crop yields, with lower slopes generally showing higher productivity due to downslope movement of soil, organic matter, and moisture [43]. For effective soil conservation, it is essential to focus on the upper and middle, where soil loss majorly occurs [44]. Targeted SCPs in these areas can prevent excessive soil displacement and accumulation in downstream areas, helping to preserve both topsoil and organic matter in upper slopes. The implementation of soil conservation measures is essential for maintaining long-term soil sustainability and agricultural productivity, especially on sloping lands prone to erosion [45]. Given this, prioritizing SCP application in all slope positions maximizes erosion control benefits and productivity gains. A key consequence of soil erosion is the loss of organic matter, which is typically concentrated in the uppermost soil layers. As erosion removes these fertile layers, the soil’s organic matter content is drastically reduced, leading to lower soil fertility and diminished water retention capacity. By reducing soil loss, SCPs like stone walls not only preserve the physical structure of the soil but also retain vital organic matter within the soil profile. This retention of organic matter is critical to sustaining soil quality and agricultural productivity over time, promoting resilience to further degradation.

3.3. Soil Organic Matter

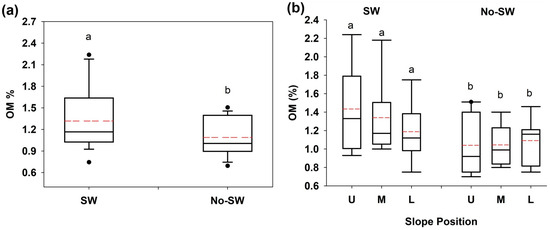

Organic matter plays a vital role in maintaining soil health and fertility, as it enhances soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability [46]. Figure 3a depicts soil organic matter content in SW vs. No-SW Sites. This figure shows that organic matter content is significantly higher (p < 0.039) in SW sites compared to No-SW sites. The higher organic matter content in SW areas demonstrates the added benefits of soil conservation beyond erosion control [47]. The reduction in soil erosion in SW areas leads to better retention of nutrient-rich topsoil, which contains a higher concentration of organic material [48]. Moreover, the slower water runoff allows organic matter, such as decomposing plant material, to accumulate in the soil, enriching its fertility. This contributes to enhanced soil microbial activity and nutrient cycling, promoting sustainable soil productivity.

Figure 3.

(a) Average organic matter content (OM %) (±standard error) in sites with stone walls (SW) and without stone walls (No-SW). Statistical comparison between sites was performed using an independent t-test. (b) Average organic matter content (OM %) (±standard error) in SW and No-SW sites across slope positions: upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L). Differences among slope positions within each treatment were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. Letters denote statistically significant differences or lack within each site, with indicating no significant difference.

Figure 3b depicts organic matter content by slope position (Upper, Middle, Lower). In SW sites, organic matter content is slightly higher (not significant) in the upper than other slope positions due to the movement of organic material downhill with water runoff, which accumulates at the lower positions. Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference in organic matter contents between all positions in both treatments.

The middle and upper slope positions show relatively lower organic matter content as some of it is washed downslope [49]. The concentration of organic matter at the lower slope positions suggests that erosion and runoff not only displace soil particles but also deplete soil nutrients and organic material from the upper slopes [50]. This could lead to nutrient imbalances across the landscape, with lower slopes becoming overly nutrient-rich and upper slopes becoming depleted [51]. In contrast, the SW sites exhibited higher organic matter content at the upper slope positions compared to the lower ones. This reversal of the typical downslope enrichment pattern indicates that stone walls effectively minimize the erosion and transport of organic material. By acting as barriers, they reduce runoff velocity, trap plant residues, and stabilize the A horizon, thereby retaining more OM in the upper and middle slope positions [52,53,54]. Consequently, less organic matter is displaced to the lower slopes, which explains the relatively lower OM content observed there. This highlights the role of SW in preserving nutrient-rich top-soil upslope and maintaining a more balanced distribution of organic matter across slope positions. Effective SCPs that stabilize soil across all slope positions are therefore crucial in preventing the loss of organic matter and maintaining balanced soil fertility. Additionally, preserving OM can support increased soil water retention and aggregation, reducing susceptibility to further erosion. In addition to improving organic matter retention, SCPs such as stone walls also play a key role in maintaining the physical structure of the soil. One of the most critical indicators of soil stability is the thickness of the A horizon, which can be heavily affected by soil erosion processes. By preventing the removal of the topsoil layer, these conservation practices contribute significantly to stabilizing the A horizon. This contributes to preserving habitat for soil biota and maintaining ecosystem functions essential for long-term soil health.

3.4. Thickness of a Horizon

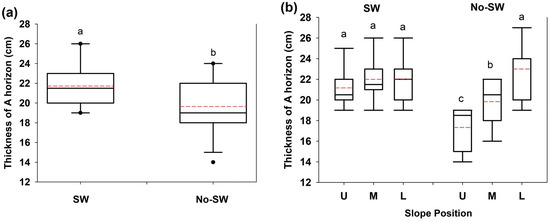

Figure 4a depicts average values of the thickness of A horizon (cm) in SW vs. No-SW Sites. The thickness of the A horizon is greater (p < 0.013) in SW sites compared to No-SW ones. SCPs help prevent the loss of the uppermost fertile soil layer, which is essential for plant growth and water retention. In areas without conservation practices, the A horizon tends to be thinner due to continuous erosion, which strips away this critical layer [55]. A thinner A horizon reduces the soil’s capacity to support crops and other vegetation, leading to reduced agricultural productivity [17,56,57]. The results show that soil conservation practice(s) investigated in the current study are effective in preserving the thickness of the A horizon, ensuring long-term soil sustainability and resilience against erosion. This preservation supports better moisture retention and nutrient availability, which are critical for sustained plant productivity.

Figure 4.

(a) Thickness of A horizon (±standard error) in sites with stone walls (SW) and without stone walls (No-SW). Statistical comparison between sites was performed using an independent t-test. (b) Thickness of A horizon (±standard error) in SW and No-SW sites across slope positions: upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L). Differences among slope positions within each treatment were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Letters denote statistically significant differences or lack within each site, as revealed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Figure 4b displays the thickness of the A horizon by slope position (upper, middle, lower). There is clear evidence from Figure 4b that the A horizon is consistently thicker in the SW sites compared to the No-SW sites, highlighting the effectiveness of stone walls in conserving topsoil. Statistical analysis showed significant differences in the thickness of A horizon between all positions in No-SW and no significant difference between all positions in SW. In the No-SW sites, the thickness of the A horizon increases downslope from the upper to the lower slope positions, reflecting the erosional removal of surface soil from upslope areas and its subsequent deposition at the lower positions. By contrast, in the SW sites the thickness of the A horizon remains relatively uniform across slope positions, indicating that the stone walls effectively reduced soil erosion and limited the downslope translocation of soil material. This stabilization of the A horizon is particularly important, as it preserves soil fertility, enhances water-holding capacity, and supports long-term productivity by preventing the progressive loss of nutrient-rich topsoil from the upper and middle slope positions. Such stabilization also helps maintain soil structure and microbial habitats necessary for ecosystem function.

The thickness of the A horizon increases progressively from upper to lower slope positions. The lower positions tend to have a thicker A horizon because soil and organic material eroded from the upper slopes accumulate there [58]. Conversely, the upper positions have thinner topsoil due to continuous erosion. The relationship between slope position and the thickness of A horizon again highlights the downslope movement of soil. To maintain soil health across an entire slope, conservation practices should aim to reduce soil displacement from the upper to lower positions [47]. By stabilizing the A horizon throughout the slope, SW can help prevent erosion and maintain soil productivity at all positions. Therefore, integrated slope management combining SCPs with vegetation cover and land use planning is recommended to sustain soil integrity.

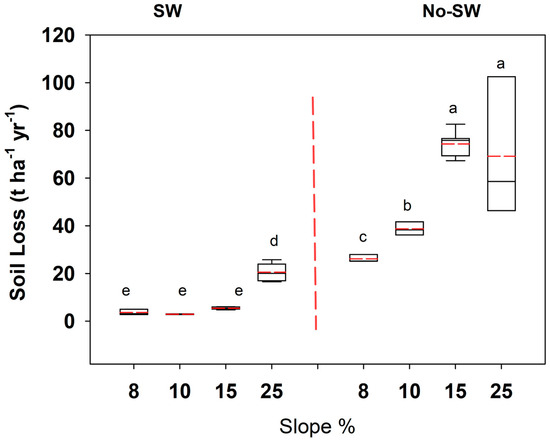

3.5. Soil Loss with Slope Gradient

Figure 5 confirms a positive relationship between slope gradient and soil loss, showing that soil loss increases progressively as the slope becomes steeper. Under the No-SW condition, the A-horizon thickness increases markedly from the upper to the lower slope positions, whereas in the SW plots it remains relatively uniform across slope positions, indicating the stabilizing effect of stone walls in reducing soil erosion. At slopes ranging from 8% to 25%, the soil loss remains consistently low, below 20 t.ha−1.yr−1. The soil loss values are relatively stable across all slope percentages, showing the effectiveness of SW in minimizing soil erosion, even as the slope increases. On the other hand, in no-SW Sites the soil loss significantly increases (p < 0.05) with the slope. At 8% slope, soil loss is minimal, but as the slope reaches 25%, soil loss rises dramatically, exceeding 100 t ha−1 yr−1. Statistical analysis showed no significant differences in soil loss between all positions in SW (Except 25% slope), and significant difference between all positions in No-SW (Except 15 and 25% slope). The data suggests that steeper slopes without SW are more prone to severe erosion. Steeper slopes experience higher rates of runoff, which accelerates erosion [59]. Previous research showed that soil loss generally increases with slope gradient, though the relationship is complex. On steep slopes, soil loss was found to increase linearly with the sine of the slope angle [60,61,62].

Figure 5.

Soil loss (±standard errors) as a function of slope gradient (%) in sites with stone walls (SW) and without stone walls (No-SW). One-way ANOVA () was applied to evaluate the effect of slope gradient on soil loss within each treatment. Letters indicate statistically significant differences among slope gradients within the SW and No-SW groups, as revealed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Our results confirm a strong interconnection between slope steepness, A-horizon thickness, soil organic matter (SOM), and erosion intensity. Steeper gradients enhance runoff velocity and soil detachment, leading to accelerated thinning of the A-horizon and depletion of SOM. In turn, reduced thickness of A and SOM weaken soil structure and resilience, further amplifying erosion risk. This reciprocal relationship is consistent with findings from [21] who demonstrated that steeper slopes were associated with lower SOM, and higher erosion hazards, ultimately threatening soil productivity and sustainability. The findings highlight that the observed erosion patterns confirm that rainfall intensity interacts with slope conditions to determine runoff magnitude and sediment loss. Steeper slopes consistently produced higher runoff volumes and sediment yields, which can be attributed to greater flow velocity and the enhanced capacity of surface water to detach and transport soil aggregates. These interactions strongly influenced the initiation of rills and gullies, particularly in areas where vegetation was sparse or soil structure was weak [63]. Therefore, the findings of this research reinforce the need for targeted soil conservation measures on steep slopes to control erosion and protect the soil. Techniques like terracing or stone walls are particularly important in steep areas to slow down water flow and reduce soil loss [64]. Integrated strategies combining physical barriers and vegetation cover enhance these effects, contributing to sustainable hillslope management.

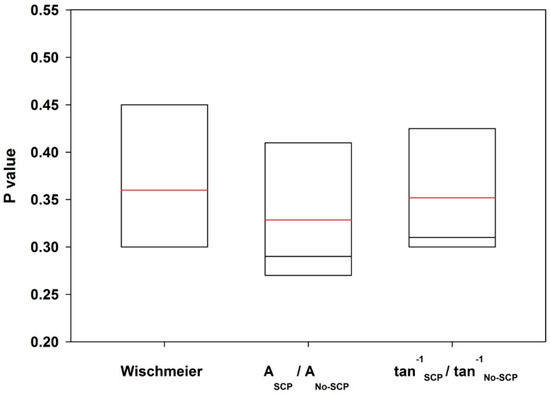

3.6. Estimation of Support Practice Factor

Estimating the support practice factor (P) is fundamental for quantifying soil erosion and assessing the effectiveness of soil conservation practices (SCPs). The results clearly demonstrate that the presence of stone walls (SW) significantly influences soil profile development and erosion patterns along the slope. As shown in Figure 4, the A-horizon thickness under SW conditions remained relatively stable across upper, middle, and lower slope positions, indicating effective control of surface runoff and soil displacement. In contrast, the No-SW slopes showed a pronounced increase in thickness toward the lower slope, reflecting progressive downslope soil movement and deposition. Similarly, Figure 5 reveals that soil loss increased sharply with slope gradient, particularly in the absence of stone walls, while SW-protected plots maintained considerably lower soil losses even at steeper slopes. These findings confirm that stone walls act as physical barriers that interrupt runoff flow, reduce its velocity, and enhance soil retention across slope gradients.

To quantify these effects, three approaches were used to estimate the P factor (Figure 6): the Wischmeier empirical method, which uses tabulated relationships between slope and conservation practice; the direct soil-loss ratio method, and the slope-based ratio method (derived from measured differences in soil thickness), which accounts for the reduction in effective slope angle caused by SCPs such as stone walls.

Figure 6.

Comparison of estimated support practice factor (p) value using the three methods.

Across all three approaches, the mean p value centered around 0.35, with corresponding ranges of 0.30–0.45, 0.27–0.42, and 0.31–0.43, respectively. Among them, the slope-based ratio method yielded the narrowest range, indicating a more stable and physically representative estimate of conservation efficiency. This method explicitly incorporates changes in slope geometry, providing a realistic assessment of how SCPs mitigate soil loss by modifying the slope profile and reducing runoff energy. The direct soil-loss ratio method also produced consistent results because it is based on observed field data. However, it may still be affected by temporal variations in rainfall or site heterogeneity, introducing moderate uncertainty. In contrast, the Wischmeier empirical approach exhibited the largest uncertainty and widest variability. This approach is based on generalized tables developed from experimental plots under specific conditions primarily in the U.S. Midwest during the mid-20th century. These tables relate p values to broad slope classes and management practices, assuming relatively uniform soil types, rainfall intensities, and conservation structures. However, in the present study, local slope gradients, stone wall configurations, and rainfall–runoff dynamics differ markedly from those empirical conditions. The Wischmeier tables also do not account for local variations in slope geometry, wall spacing, or micro-topography, which strongly influence runoff behavior and erosion potential. Consequently, applying those generalized relationships to the heterogeneous conditions of this study produced a wider p-value range (0.30–0.45), reflecting greater uncertainty and lower site specificity compared to the slope-based and direct ratio methods.

Overall, while all three methods produced comparable mean p values, the slope-based ratio method provided the most robust and physically interpretable results, followed by the direct soil-loss ratio method, whereas Wischmeier’s empirical approach showed the lowest precision under the studied conditions. These findings emphasize the importance of incorporating field-based observations and geometric slope adjustments to improve the accuracy of erosion modeling and better represent the real-world performance of conservation structures in sloping agricultural systems.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that stone wall (SW) conservation practices significantly reduced soil erosion and enhanced soil profile stability across varying slope gradients. Soils protected by SW maintained a more uniform and thicker A-horizon, particularly at upper and middle slope positions, compared to adjacent No-SW plots where marked thinning occurred upslope and accumulation downslope. The presence of SW also contributed to higher organic matter content, reflecting improved soil retention and reduced nutrient loss.

By integrating the measured A-horizon thickness into the estimation of the support practice factor (P), this study provided a more reliable and field-based assessment of conservation effectiveness. Among the three evaluated approaches, the slope-based ratio method yielded the most stable and physically meaningful p values, followed by the direct soil-loss ratio method, while Wischmeier’s empirical method showed greater uncertainty under local conditions.

These findings confirm that stone walls are an effective and low-cost soil conservation practice that reduces erosion to tolerable levels and supports long-term agricultural productivity in semi-arid Mediterranean landscapes. To sustain their performance, periodic inspection and maintenance every five years are recommended. Future work should explore the integration of biological conservation measures with stone walls to further enhance soil resilience and ecosystem stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G. and N.E.; methodology, M.A.G. and N.E.; software, M.A.G. and H.A.-Z.; validation, M.A.G., N.E. and N.M.; formal analysis, M.A.G., H.A.-Z. and N.M.; investigation, M.A.G., H.A.-Z. and N.E.; resources, M.A.G.; data curation, M.A.G., N.E. and H.A.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.G. and N.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G. and N.M.; visualization, M.A.G., H.A.-Z. and N.M.; supervision, M.A.G. and N.E.; project administration, M.A.G.; funding acquisition, M.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the deanship of research at the Jordan University of Science and Technology (grant number 2017/188).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Availability of data can be obtained upon special request to the main author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help offered by Yaser Mhawish from Integrated Water and Land Management unit, ICARDA for facilitating access to study sites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCPs | Soil Conservation Practices |

| SW | Stone Walls |

| USLE | Universal soil loss equation |

| t.ha−1.yr−1 | Tons per hectare per year |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| OM | Organic matter |

References

- Agassi, M. Soil Erosion, Conservation, and Rehabilitation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781000941944. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, M.; Philippidis, G.; Ferrari, E.; Borrelli, P.; Lugato, E.; Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. A Linkage between the Biophysical and the Economic: Assessing the Global Market Impacts of Soil Erosion. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, M.; Ferrari, E.; M’Barek, R.; Philippidis, G.; Boysen-Urban, K.; Borrelli, P.; Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. Remaining Loyal to Our Soil: A Prospective Integrated Assessment of Soil Erosion on Global Food Security. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 219, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Fleischer, L.R.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C.; Alewell, C.; Meusburger, K.; Modugno, S.; Schütt, B.; Ferro, V.; et al. An Assessment of the Global Impact of 21st Century Land Use Change on Soil Erosion. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naorem, A.; Jayaraman, S.; Dang, Y.P.; Dalal, R.C.; Sinha, N.K.; Rao, C.S.; Patra, A.K. Soil Constraints in an Arid Environment—Challenges, Prospects, and Implications. Agronomy 2023, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Dar, M.U.D.; Meena, R.S. Soil Erosion and Management Strategies. In Sustainable Management of Soil and Environment; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 73–122. ISBN 9789811388323. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.R. Soil Erosion and Agricultural Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13268–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.P.C. Soil Erosion and Conservation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781405144674. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini, T.; Galli, A.; Marsala, V.; Miccadei, E. Analysis of Soil Erosion Induced by Heavy Rainfall: A Case Study from the NE Abruzzo Hills Area in Central Italy. Water 2018, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, M.; Liu, D. The Impact of Land Use and Rainfall Patterns on the Soil Loss of the Hillslope. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.G.; Adam, M.A. The Impact of Vegetative Cover Type on Runoff and Soil Erosion under Different Land Uses. Catena 2010, 81, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Balasmeh, O.; Karmaker, T.; Babbar, R. Experimental Investigation and Modelling of Rainfall-Induced Erosion of Semi-Arid Region Soil under Various Vegetative Land Covers. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 1029–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.H.; López-Vicente, M.; Wu, G.L. Effectiveness of Re-Vegetated Forest and Grassland on Soil Erosion Control in the Semi-Arid Loess Plateau. Catena 2020, 195, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, M.; Elnaggar, A.; Omar, M.; Murtala, A.; Lawal, M.; Mosa, A. Land Degradation, Causes, Iamplications and Sustainable Management in Arid and Semi Arid Regions: A Case Study of Egypt. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 63, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Tian, Y.; Zhai, J.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, Q. Soil Erosion Resilience under Climate Extremes: Disentangling the Impacts of Vegetation Restoration and Rainfall Intensification across China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeraratna, S. Factors Causing Land Degradation. In Understanding Land Degradation: An Overview; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Lal, R. Principles of Soil Conservation and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9789048185290. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, D.; Patra, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Alam, N.M.; Jana, C.; Lal, R. Impacts of Soil Erosion on Soil Quality and Agricultural Sustainability in the North-Western Himalayan Region of India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoton, F.E.; Shipitalo, M.J.; Lindbo, D.L. Runoff and Soil Loss from Midwestern and Southeastern US Silt Loam Soils as Affected by Tillage Practice and Soil Organic Matter Content. Soil Tillage Res. 2002, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I.; Lal, R. Variability of Soil Physical Quality and Erodibility in a Water-Eroded Cropland. Catena 2011, 84, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wilson, G.V.; Hao, Y.; Han, X. Erosion Hazard Evaluation for Soil Conservation Planning That Sustains Life Expectancy of the A-Horizon: The Black Soil Region of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 2629–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, Z.; Cai, C.; Shi, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X. Soil Thickness Effect on Hydrological and Erosion Characteristics under Sloping Lands: A Hydropedological Perspective. Geoderma 2011, 167, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantappiè, M.; Lorenzetti, R.; De Meo, I.; Costantini, E.A.C. How to Improve the Adoption of Soil Conservation Practices? Suggestions from Farmers’ Perception in Western Sicily. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Poesen, J.; Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Meusburger, K.; Montanarella, L.; Alewell, C. The New Assessment of Soil Loss by Water Erosion in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera, C.; Djuma, H.; Bruggeman, A.; Zoumides, C.; Eliades, M.; Charalambous, K.; Abate, D.; Faka, M. Quantifying the Effectiveness of Mountain Terraces on Soil Erosion Protection with Sediment Traps and Dry-Stone Wall Laser Scans. Catena 2018, 171, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, D.; Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Govers, G.; Moeyersons, J. Effectiveness of Stone Bunds in Controlling Soil Erosion on Cropland in the Tigray Highlands, Northern Ethiopia. Soil Use Manag. 2005, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Himics, M.; Scarpa, S.; Matthews, F.; Bogonos, M.; Poesen, J.; Borrelli, P. Projections of Soil Loss by Water Erosion in Europe by 2050. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Meusburger, K.; van der Zanden, E.H.; Poesen, J.; Alewell, C. Modelling the Effect of Support Practices (P-Factor) on the Reduction of Soil Erosion by Water at European Scale. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 51, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, J.M.; Nadal-Romero, E.; Lana-Renault, N.; Beguería, S. Erosion in Mediterranean Landscapes: Changes and Future Challenges. Geomorphology 2013, 198, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohawesh, Y.; Taimeh, A.; Ziadat, F. Effects of Land Use Changes and Soil Conservation Intervention on Soil Properties as Indicators for Land Degradation under a Mediterranean Climate. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoA. The Soils of Jordan: Report of the National Soil Map and Land Use Project (Levels I, II, III, and JOSCIS Manual). In Ministry of Agriculture; Ministry of Agriculture and Hunting Technical Services Ltd.: Amman, Jordan, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G.W.; Bauder, J.W. Particle-Size Analysis. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 1: Physical and Mineralogical Methods; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 383–411. ISBN 9780891188643. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 961–1010. ISBN 9780891188667. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall Erosion Losses: A Guide to Conservation Planning; Agriculture handbook; Department of Agriculture, Science and Education Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1978.

- Eltaif, N.I.; Gharaibeh, M.A.; Al-Zaitawi, F.; Alhamad, M.N. Approximation of Rainfall Erosivity Factors in North Jordan. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, G.; Poesen, J.; Wesemael, B.V.; Vanmaercke, M.; Teka, D.; Deckers, J.; Goosse, T.; Maetens, W.; Nyssen, J.; Hallet, V.; et al. Effects of Land Use, Slope Gradient, and Soil and Water Conservation Structures on Runoff and Soil Loss in Semi-Arid Northern Ethiopia. Phys. Geogr. 2013, 34, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Y.M.; Jasińska, J.; Yadeta, L.T.; Świtoniak, M.; Puchałka, R.; Gebregeorgis, E.G. Soil Loss Estimation for Conservation Planning in the Welmel Watershed of the Genale Dawa Basin, Ethiopia. Agronomy 2020, 10, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvade, S.; Upadhyay, V.B.; Kumar, M.; Imran Khan, M. Soil and Water Conservation Techniques for Sustainable Agriculture. In Sustainable Agriculture, Forest and Environmental Management; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akale, A.T.; Dagnew, D.C.; Belete, M.A.; Tilahun, S.A.; Mekuria, W.; Steenhuis, T.S. Impact of Soil Depth and Topography on the Effectiveness of Conservation Practices on Discharge and Soil Loss in the Ethiopian Highlands. Land 2017, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonas, A.; Temesgen, K.; Alemayehu, M.; Toyiba, S. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Soil and Water Conservation Practices on Improving Selected Soil Properties in Wonago District, Southern Ethiopia. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 2017, 8, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbanshi, J.; Das, S.; Paul, R. Quantification of the Effects of Conservation Practices on Surface Runoff and Soil Erosion in Croplands and Their Trade-off: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.E.; Schuman, G.E. Cultivation and Slope Position Effects on Soil Organic Matter. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1988, 52, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sereenonchai, S.; Kongsurakan, P.; Yuttitham, M.; Hatano, R. Variations of Soil Properties and Soil Surface Loss after Fire in Rotational Shifting Cultivation in Northern Thailand. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1213181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, H.; Liang, C.; Chang, X.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X. Spatial Variation in Soil Physico-Chemical Properties along Slope Position in a Small Agricultural Watershed Scale. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, D.D.; Midmore, D.J.; West, L.T. Erosion and Productivity of Vegetable Systems on Sloping Volcanic Ash–Derived Philippine Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bashir, H.; Zafar, S.; Rehman, R.; Khalid, M.; Awais, M.; Sadiq, M.; Amjad, I. The Importance of Soil Organic Matter (Som) on Soil Productivity and Plant Growth. Biol. Agric. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muche, K.; Molla, E. Assessing the Impacts of Soil Water Conservation Activities and Slope Position on the Soil Properties of the Gelda Watershed, Northwest Ethiopia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2024, 2024, 6858460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, R.J.; Sims, B.G. Fertility Gradients in Naturally Formed Terraces on Honduran Hillside Farms. Agron. J. 1999, 91, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikova, O.O.; Demidov, V.V.; Farkhodov, Y.R.; Tsymbarovich, P.R.; Semenkov, I.N. Influence of Water Erosion on Soil Aggregates and Organic Matter in Arable Chernozems: Case Study. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.A.; Zhang, J.H.; Nie, X.J. Effect of Soil Erosion on Soil Properties and Crop Yields on Slopes in the Sichuan Basin, China. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi, M.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Knief, C.; Ghotbi, M.; Kent, A.D.; Horwath, W.R. The Patchiness of Soil 13C versus the Uniformity of 15N Distribution with Geomorphic Position Provides Evidence of Erosion and Accelerated Organic Matter Turnover. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 356, 108616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolka, K.; Biazin, B.; Martinsen, V.; Mulder, J. Soil and Water Conservation Management on Hill Slopes in Southwest Ethiopia. I. Effects of Soil Bunds on Surface Runoff, Erosion and Loss of Nutrients. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 142877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampenhout, K.; Nyssen, J.; Gebremichael, D.; Deckers, J.; Poesen, J.; Haile, M.; Moeyersons, J. Stone Bunds for Soil Conservation in the Northern Ethiopian Highlands: Impacts on Soil Fertility and Crop Yield. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 90, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, G.; Tesfaye, S.; Van Parijs, I.; Poesen, J.; Vanmaercke, M.; van Wesemael, B.; Guyassaa, E.; Nyssen, J.; Deckers, J.; Haregeweyn, N. Impact of Soil and Water Conservation Structures on the Spatial Variability of Topsoil Moisture Content and Crop Productivity in Semi-Arid Ethiopia. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 238, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplot, V.; Lorentz, S.; Podwojewski, P.; Jewitt, G. Digital Mapping of A-Horizon Thickness Using the Correlation between Various Soil Properties and Soil Apparent Electrical Resistivity. Geoderma 2010, 157, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Gebremichael, D.; Vancampenhout, K.; D’aes, M.; Yihdego, G.; Govers, G.; Leirs, H.; Moeyersons, J.; Naudts, J.; et al. Interdisciplinary On-Site Evaluation of Stone Bunds to Control Soil Erosion on Cropland in Northern Ethiopia. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 94, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Preti, F.; Romano, N. Terraced Landscapes: From an Old Best Practice to a Potential Hazard for Soil Degradation Due to Land Abandonment. Anthropocene 2014, 6, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshaneh, G.T. Effect of Slope Position on Soil Physico-Chemical Properties with Different Management Practices in Small Holder Cultivated Farms of Abuhoy Gara Catchment, Gidan District, North Wollo. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 3, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Sun, T.; Fei, K.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.; Wu, Y.; Ni, L. Effects of Erosion Degree, Rainfall Intensity and Slope Gradient on Runoff and Sediment Yield for the Bare Soils from the Weathered Granite Slopes of SE China. Geomorphology 2020, 352, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Nearing, M.A.; Risse, L.M. Slope Gradient Effects on Soil Loss for Steep Slopes. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1994, 37, 1835–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapolka, N.M.; Dollhopf, D.J. Effect of Slope Gradient and Plant Growth on Soil Loss on Reconstructed Steep Slopes. Int. J. Surf. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2001, 15, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, G.J.; So, H.B. Predicting the Effect of Slope Gradient on Soil Erosion Rates for Steep Landscapes; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Sun, L.; Tang, Z. Effects of Rainfall and Slope on Runoff, Soil Erosion and Rill Development: An Experimental Study Using Two Loess Soils. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wei, W.; Chen, L. Effects of Terracing Practices on Water Erosion Control in China: A Meta-Analysis. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).