Assessment of Geohydraulic Parameters in Coastal Aquifers Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography: A Case Study from the Chaouia Region, Western Morocco

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

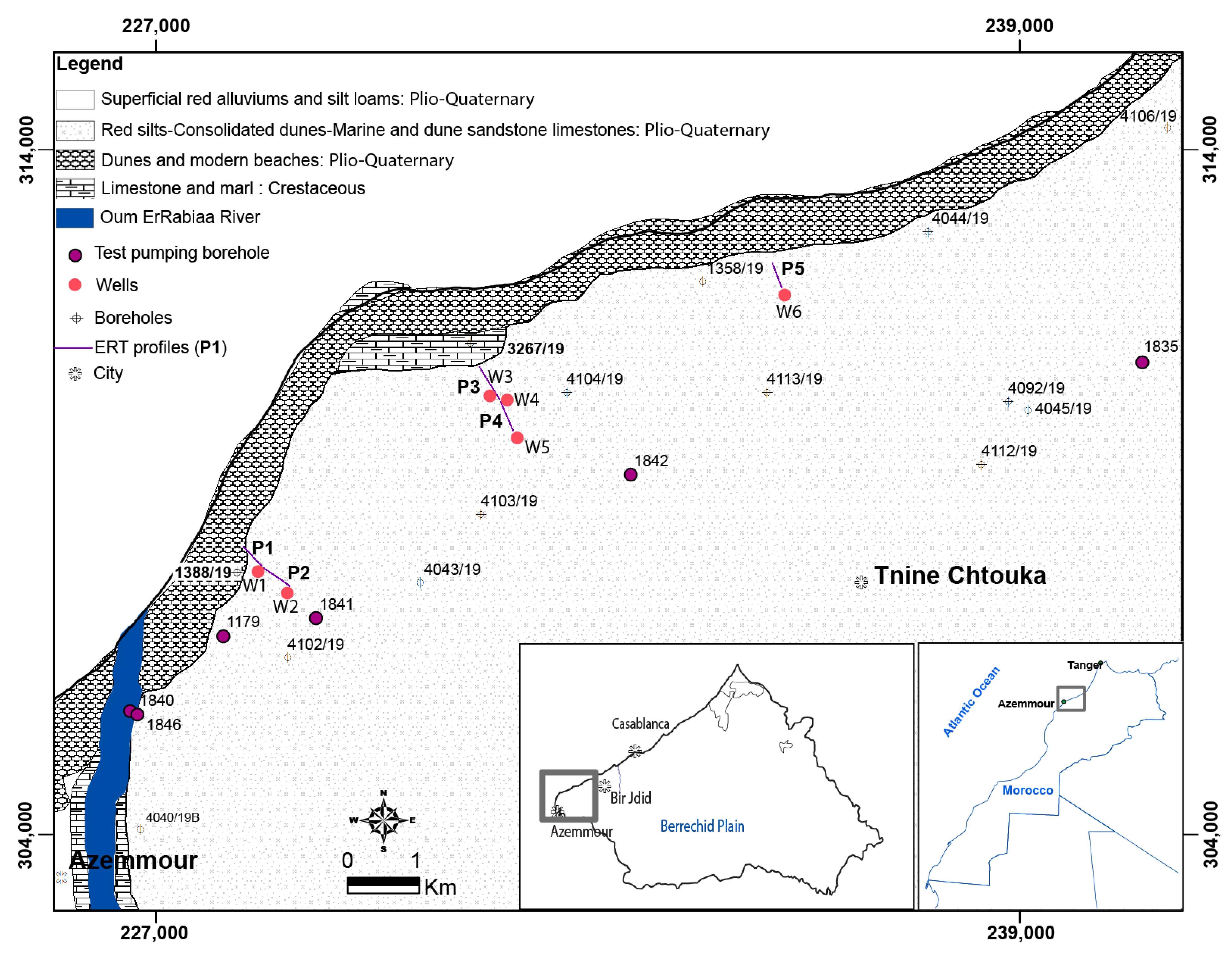

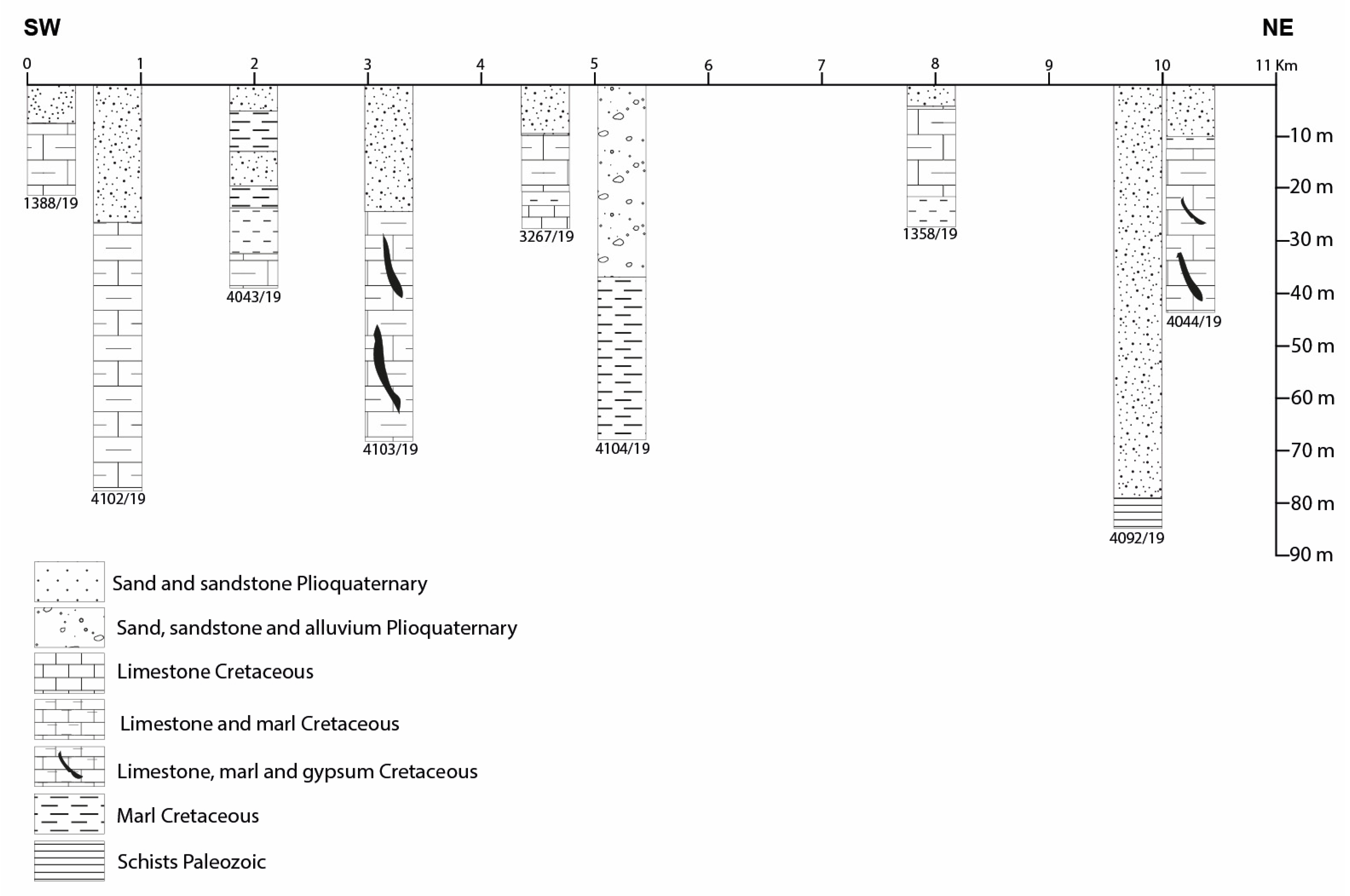

2.1. Study Area Setting

2.2. Geoelectrical Data

2.3. Estimation of Geohydraulic Parameters

- Calculation of hydraulic conductivity (K) using the empirical formula of Heigold et al. [22].

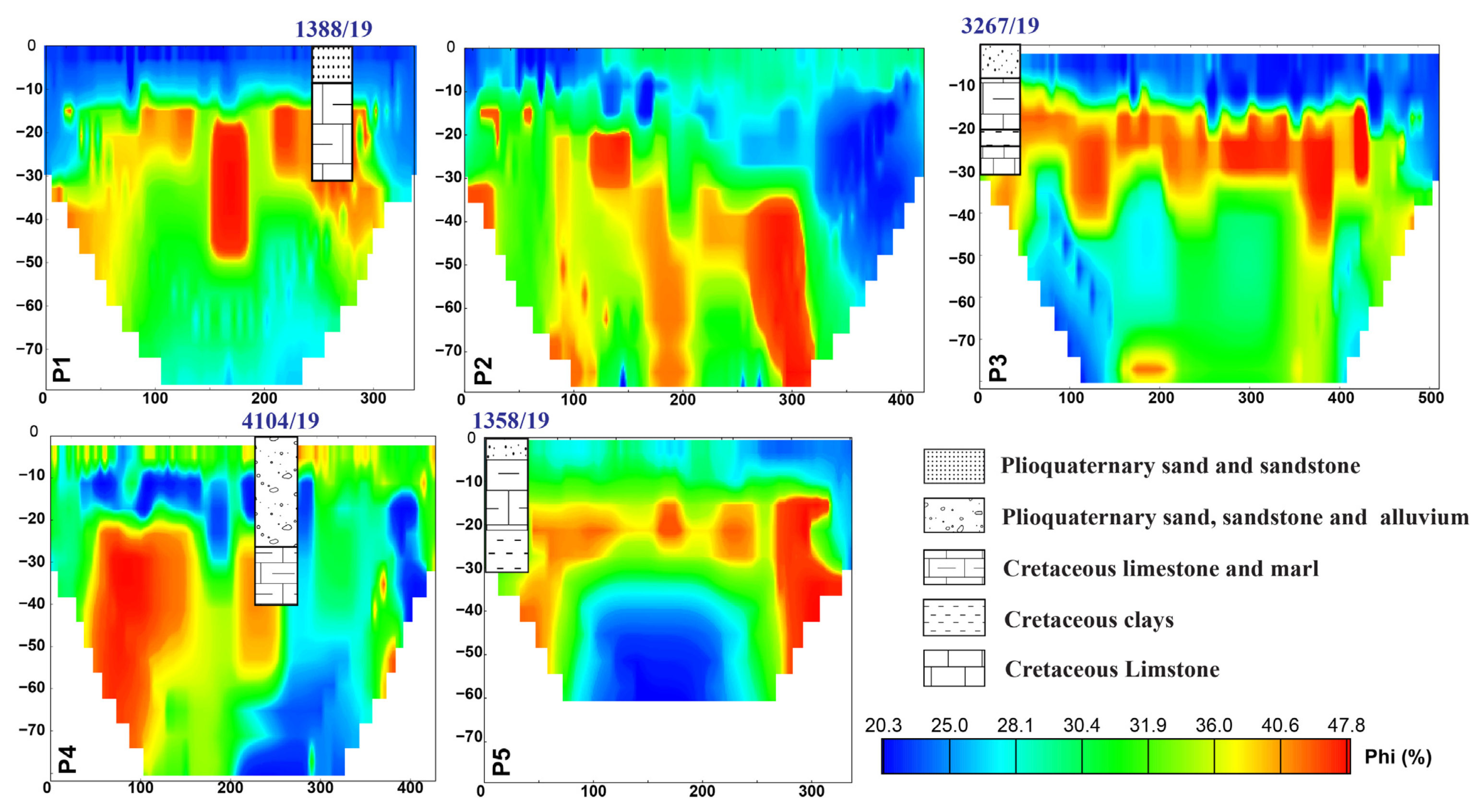

- Estimation of effective porosity (Φeff) using the logarithmic model of Marotz [21].

- Determination of aquifer thickness (h) from depth analysis of inverted resistivity sections.

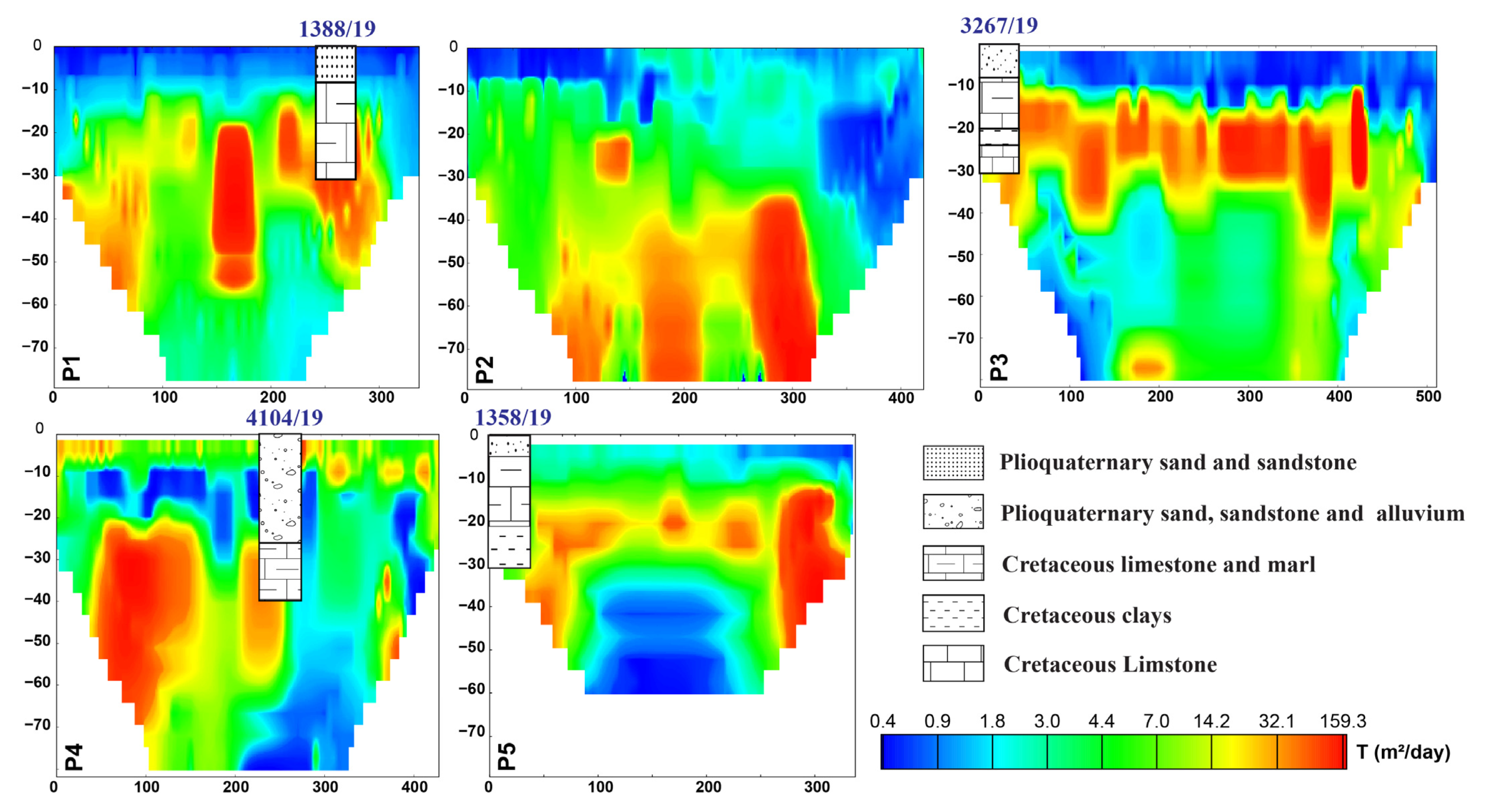

- Computation of transmissivity (T) by combining K and h to assess aquifer productivity.

3. Results and Discussion

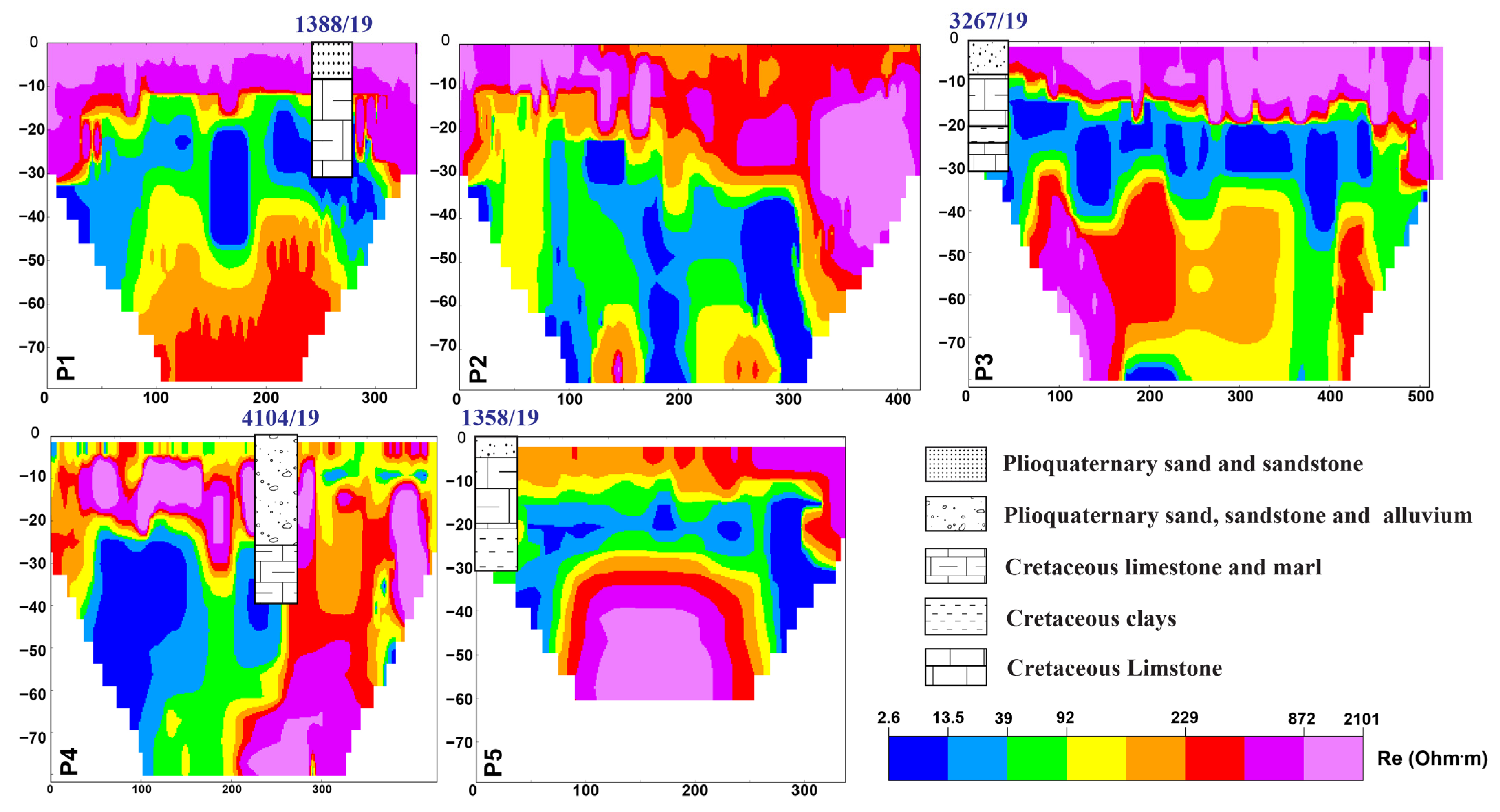

3.1. ERT Modeling

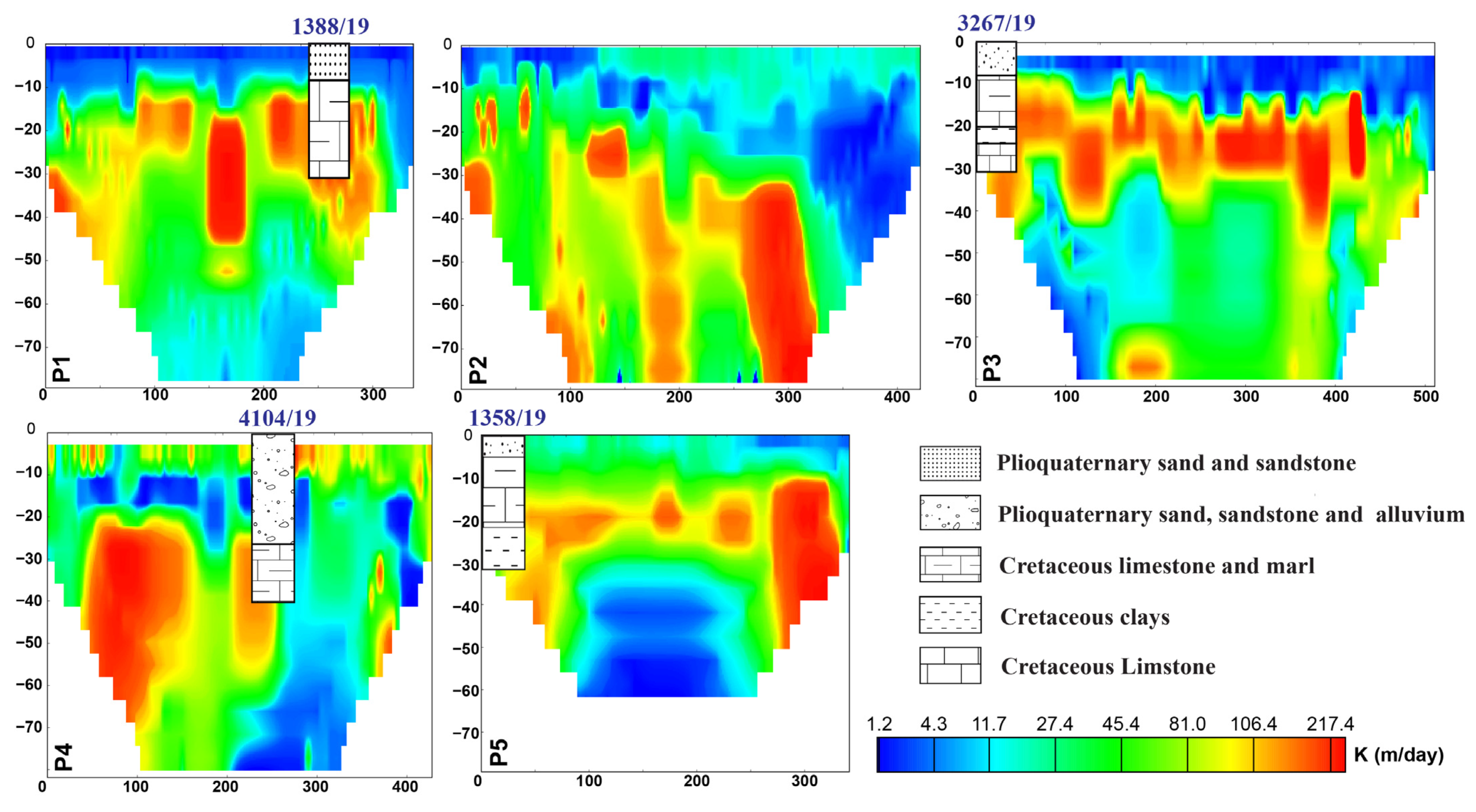

3.2. Geohydraulic Parameters Estimation

- The inherent limitations of ERT, including limited vertical resolution, the influence of lateral heterogeneity, and uncertainties associated with the inversion process.

- Uncertainties related to pumping tests and the spatial variability of hydraulic properties at the field scale.

- Possible discrepancies between estimates and measurements, although the ranges derived from ERT remain broadly consistent with those from pumping tests despite differences in scale and methodology.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benoit, J.; Hardaway, C.S.; Hernandez, D.; Holman, R.; Koch, E.; McLellan, N.; Peterson, S.; Reed, D.; Suman, D. Mitigating Shore Erosion Along Sheltered Coasts; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/11764/mitigating-shore-erosion-along-sheltered-coasts (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Steyl, G.; Dennis, I. Review of coastal-area aquifers in Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 2010, 18, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfahani, J. Hydraulic parameters estimation by using an approach based on vertical electrical soundings (VES) in the semi-arid Khanasser valley region, Syria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2016, 117, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, S.; Kurse, E.E.; Ainchil, J.E. Estimation of hydraulic parameters using resistivity tomography (ERT) and empirical laws in a semi-confined aquifer. Near Surf. Geophys. 2018, 1, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.M.; Yeh, W.W.-G. Optimal pumping test desiggn for parameter estimation and prediction ingroundwater hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 1990, 49, 4491–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marsily, G. Quantitative Hydrogeology: Groundwater Hydrology for Engineers; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; 440p, ISBN 0-12-208915-4. [Google Scholar]

- Binley, A.; Slater, L.D.; Fukes, M.; Cassiani, G. Relationship between spectral induced polarization and hydraulic properties of saturated and unsaturated sandstone. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, K.; Gorelick, S.M. Saline tracer visualized with three-dimensional electrical resistivity tomography: Field-scale spatial moment analysis. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W05023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, J.C. Apport de la Tomographie Électrique a la Modélisation des Écoulements Densitaires dans les Aquifères Côtiers: Application a Trois Contextes Climatiques Contrastes (Canada, Nouvelle-Caledonie, Sénégal). Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. D’Avignon et des pays de Vaucluse, Avignon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lekmine, G. Quantification des Paramètres de Transport des Solutés en Milieux Poreaux par Tomographie de Résistivité Électrique: Développements Méthodologiques et Expérimentaux. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Paris Sud, Orsay, France, 2011. 160p. [Google Scholar]

- George, N.J.; Atat, J.G.; Umoren, E.B.; Etebong, I. Geophysical exploration to estimate the surface conductivity of residual argillaceous bands in the groundwater repositories of coastal sediments of EOLGA, Nigeria. NRIAG J. Astron. Geophys. 2017, 6, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadili, A.; Najib, S.; Boualla, O.; Makan, A.; Mehdi, K.; Kharis, A. Estimation of geohydraulic parameters in coastal aquifers based on VES transformed to ERT profiles. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, J.J.; Wuilleumier, A. Projet GAIA-Année 3-Exploitation des Cycles D’injections et de Soutirages de Gaz Aux Sites de Lussagnet et Izaute Pour Déterminer les Paramètres Hydrodynamiques de L’aquifère des Sables Infra-Molassiques. Rapport D’étape. BRGM/RP-67369-France. 2018. Available online: https://infoterre.brgm.fr/rapports/RP-67369-FR.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Fadili, A.; Malaurent, P.; Najib, S.; Mehdi, K.; Riss, J.; Makan, A. Groundwater hydrodynamics and salinity response to oceanic tide in coastal aquifers: Case study of Sahel Doukkala, Morocco. Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 2459–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Yang, L. Estimation of coastal aquifer properties: A review of the tidal method based on theoretical solutions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2021, 8, e1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazzaq, Z.T.; Al-Ansari, N.; Aziz, N.A.; Agbasi, O.E.; Etuk, S.E. Estimation of main aquifer parameters using geoelectric measurements to select the suitable wells locations in Bahr Al-Najaf depression, Iraq. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, G.; Ge, Y.; Hasan, M.; Shang, Y. Estimation of hydrogeological parameters by using pumping, laboratory data, surface resistivity and Thiessen technique in Lowaer Bari Doab (Indus Basin), Pakistan. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.; Maciel, D.F.; Sousa, K.F.; Nascimento, C.T.C.; Koide, S. Vertical electrical sounding (VES) for estimation of hydraulic parameters in the porous aquifer. Water 2021, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotz, G. Techische grundlageneiner wasserspeicherung imm naturlichen untergrund habilitationsschrift. Univ. Stuttg. 1968, 2, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Heigold, P.C.; Gilkeson, R.H.; Cartwright, K.; Reed, P.C. Aquifer transmissivity from surfacial electrical methods. Groundwater 1979, 17, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.S. Modelling of lithology and hydraulic conductivity of shallow sediments from resistivity measurements using Schlumberger vertical electric soundings. Energy Sources 2001, 23, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, S.; Fadili, A.; Mehdi, K.; Riss, J.; Makan, A. Contribution of hydrochemical and geoelectrical approaches to investigate salization process and seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifers of Chaouia, Morocco. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2017, 198, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, S.; Fadili, A.; Mehdi, K.; Riss, J.; Makan, A.; Guessir, H. Salinization process and coastal groundwater quality in Chaouia, Morocco. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2016, 115, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentayeb, A. Hydrogeological Study of the Chaouia Coast and Steady State Modeling Attempt, Morocco. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 1972. Volume 151, p. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lecointre, G.; Gigout, M. Carte géologique provisoire de la région de Casablanca au 1/200 000 et notice explicative. Notes M. Serv. géol. Maroc 1950, 72, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin, T. 2D resistivity surveying for environmental and engineering applications. First Break 1996, 14, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Wilkinson, P.B.; Chambers, J.E. Fast computation of optimized electrode arrays for 2D resistivity surveys. J. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Vargemezis, G.; Voudouris, K.S. Estimation of hydraulic parameters in a complex porous aquifer system using geoelectrical methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Barker, R.D. Rapid least-squares inversion of apparent resistivity pseudosections by a quasi-Newton method1. Geophys. Prospect. 1996, 44, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynolabedin, A.; Ghiassi, R.; Norooz, R.; Najib, S.; Fadili, A. Evaluation of geoelectrical models efficiency for coastal seawater intrusion by applying uncertainty analysis. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Dahlin, T. A comparison of the Gauss-Newton and quasi-Newton methods in resistivity imaging inversion. J. Appl. Geophys. 2002, 49, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadili, A.; Najib, S.; Mehdi, K.; Riss, J.; Malaurent, P.; Makan, A. Geoelectrical and hydrochemical study for the assessment of seawater intrusion evolution in coastal aquifers of Oualidia, Morocco. J. Appl. Geophys. 2017, 146, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwas, S.; Celik, M. Equation estimation of porosity and hydraulic conductivity of Ruhrtal aquifer in Germany using near surface geophysics. J. Appl. Geophys. 2012, 84, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadili, A.; Mehdi, K.; Riss, J.; Najib, S.; Makan, A.; Boutayeb, K. Evaluation of groundwater mineralization processes and seawater extension in the coastal aquifer of Oualidia, Morocco: Hydrochemical and geophysical approach. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 8567–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, R. Borehole and surface-based hydrogeophysics. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archie, G.E. The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics. Trans. Am. Inst. Min. Eng. 1942, 146, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castany, G. Principes et Méthodes de L’hydrogéologie; Ed Dunod: Paris, France, 1982; 236p, ISBN 9782040112219/2040112219. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media; Environmental Science Series; Americain Elsevier Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 13:978-0-486-65675-5. [Google Scholar]

- Domenico, P.A.; Schwartz, F.W. Physical and Chemical Hydrogeology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ezema, O.K.; Ibuot, J.C.; Obiora, D.N. Geophysical investigation of aquifer repositories in Ibagwa Aka, Enugu State, Nigeria, using electrical resistivity method. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urom, O.O.; Opara, A.I.; Usen, O.S.; Akiang, F.B.; Isreal, H.O.; Ibezim, J.O.; Akakuru, O.C. Electro-geohydraulic estimation of shallow aquifers of Owerri and environs, Southeastern Nigeria using multiple empirical resistivity equations. Int. J. Energy Water Resour. 2021, 6, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwas, S.; Singhal, D.C. Estimation of aquifer transmissivity from Dar-Zarrouk parameters in porous media. J. Hydrol. 1981, 50, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younsi, A. Méthodologie de Mise en Évidence des Mécanismes de Salure des Eaux Souterraines Côtières en Zone Semi-Aride Irriguée (Chaouia Côtière, Maroc). Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Chouaib Doukkali, El Jadida, Morocco, 2001. 190p. [Google Scholar]

- Moustadraf, J. Modélisation Numérique d’un Système Aquifère Côtier: Étude de L’impact de la Séchresse et de L’intrusion Marine (la Chaouia Côtière, Maroc). Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. de Poitiers, Poitiers, France, 2006. 212p. [Google Scholar]

- Oularé, S.; Kouamé, A.; Saley, M.B.; Ake, G.E.; Kouassi, M.A.; Adon, G.C.; Kouamé, F.K.; Therrien, R. Estimation de la conductivité hydraulique des zones discrètes de réseaux de fractures à partir des charges hydrauliques: Application au bassin versant du N’zo (ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire). Rev. Sci. L’eau 2016, 29, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fetter, C.W. Applied Hydrogeology, 4th ed.; Prentice-Hall; Pearson Education Limited: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 605. ISBN 0-13-088239-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chretien, J.; Pedro, G.; Meunier, D. Granulométrie, porosité et spectre poral de sols développés sur formations détritiques Cas des terrasses alluviales de la Saône. Cah.-ORSTOM. Pédologie 1987, 23, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Oguama, B.E.; Jbuot, J.C.; Obiora, D.N. Geohydraulic study of aquifer characteristics in prts of Enugu North Local Government Area of Enugu State using electrical resistivity soundings. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, M.C. Handbook of Ground Water Development; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 10:0471856118/13: 9780471856115. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, H.S. Determination of fuid transmissivity and electric transverse resistance for shallow aquifers and deep reservoirs from surface and well-log electric measurements. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 1999, 3, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.J.; Emah, J.B.; Ekong, U.N. Geohydrodynamic properties of hydrogeological units in parts of Niger Delta, Southern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2015, 105, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, P.M.; Reichard, E.G. Saltwater intrusion in coastal regions of North America. Hydrogeol. J. 2010, 18, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebong, E.D.; Akpan, A.E.; Onwuegbuche, A.A. Estimation of geohydraulic parameters from fractured shales and sandstone aquifers of Abi (Nigeria) using electrical resistivity and hydrogeologic measurements. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2014, 96, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krásný, J. Classifcation of transmissivity magnitude and variation. Groundwater 1993, 31, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustadraf, J.; Razack, M.; Sinan, M. Evaluation of the impacts of climate changes on the coastal Chaouia aquifer, Morocco, using numerical modeling. Hydrogeol. J. 2008, 16, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DRPE. Etude Hydrogéologique de la Nappe de la Chaouia Côtière; Maroc Rapport Scientifique: Rabat, Morocco, 1996; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Oli, I.C.; Opara, A.I.; Okeke, O.C.; Akaolisa, O.Z.; Akakuru, O.C.; Osi-Okeke, I.; Udeh, H.M. Evaluation of aquifer hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity of Ezza/Ikwo area, Southeastern Nigeria, using pumping test and surficial resistivity techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, A.I.; Kamal, K.A. Effect of structure and lithological heterogeneity on the correlation coefficient between the electric–hydraulic parameters of the aquifer, Eastern Desert, Egypt. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, S. Etude de L’évolution de la Salinization de L’aquifère de la Chaouia Côtière (Azemmour-Bir Jdid) Maroc: Climatologie, Hydrogéologie et Tomographie Électrique. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Chouaib Doukkali, El Jadida, Morocco, 2014. 287p. [Google Scholar]

- Fakir, Y.; Zerouali, A.; Aboufirassi, M. Exploitation et salinité des aquifères de la Chaouia Côtière, littoral atlantique, Maroc (Potential exploitation and salinity of aquifers, Chaouia coast, Atlantic shoreline, Morocco). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2002, 32, 791801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Profile Length | Number of Data Points | Number of Iterations | RMS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 355 | 1318 | 7 | 2.7 |

| P2 | 445 | 1912 | 6 | 3.2 |

| P3 | 535 | 2496 | 7 | 4.7 |

| P4 | 445 | 2789 | 4 | 12 |

| P5 | 355 | 2924 | 7 | 2.9 |

| Observation Wells | Depth (m) | EC (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|

| W1 | 9.2 | 10.7 |

| W2 | 14.2 | 8.9 |

| W3 | 10.4 | 6 |

| W4 | 27 | 5.2 |

| W5 | 15 | 8.9 |

| W6 | 3.3 | 4 |

| Hydrostratigraphic Unit | Description | Rw (Ohm·m) | K (m/day) | Φeff (%) | T (m2/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface unit | Plio-Quaternary | 374 to >872 | 1.2–11.7 | 20.3–30.4 | 0.4–14.2 |

| sandstones and sands (unsaturated) | |||||

| Middle unit | Cenomanian marls and limestones | 2.7–8.7 | 106.4 to >217.4 | 31.9–47.8 | 14.2–159.3 |

| (saturated with brackish to saline water) | |||||

| Lower unit | Cenomanian gypsiferous limestone and marls | 107.3–374 | 11.7–81.0 | 25.0–36.0 | 1.8–7.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Najib, S.; Fadili, A.; Boualla, O.; Mehdi, K.; Bouzerda, M.; Makan, A.; Zourarah, B.; Ilmen, S. Assessment of Geohydraulic Parameters in Coastal Aquifers Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography: A Case Study from the Chaouia Region, Western Morocco. Earth 2025, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040149

Najib S, Fadili A, Boualla O, Mehdi K, Bouzerda M, Makan A, Zourarah B, Ilmen S. Assessment of Geohydraulic Parameters in Coastal Aquifers Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography: A Case Study from the Chaouia Region, Western Morocco. Earth. 2025; 6(4):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040149

Chicago/Turabian StyleNajib, Saliha, Ahmed Fadili, Othmane Boualla, Khalid Mehdi, Mohammed Bouzerda, Abdelhadi Makan, Bendahhou Zourarah, and Said Ilmen. 2025. "Assessment of Geohydraulic Parameters in Coastal Aquifers Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography: A Case Study from the Chaouia Region, Western Morocco" Earth 6, no. 4: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040149

APA StyleNajib, S., Fadili, A., Boualla, O., Mehdi, K., Bouzerda, M., Makan, A., Zourarah, B., & Ilmen, S. (2025). Assessment of Geohydraulic Parameters in Coastal Aquifers Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography: A Case Study from the Chaouia Region, Western Morocco. Earth, 6(4), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040149